Steve Jobs' Personal Apple Artifacts Going to Auction: What You Need to Know

There's something deeply human about the objects we leave behind. They tell stories that no biography could quite capture. When you walk into someone's childhood bedroom, you're not just looking at furniture and forgotten trinkets. You're seeing the fragments of who they were before the world knew their name.

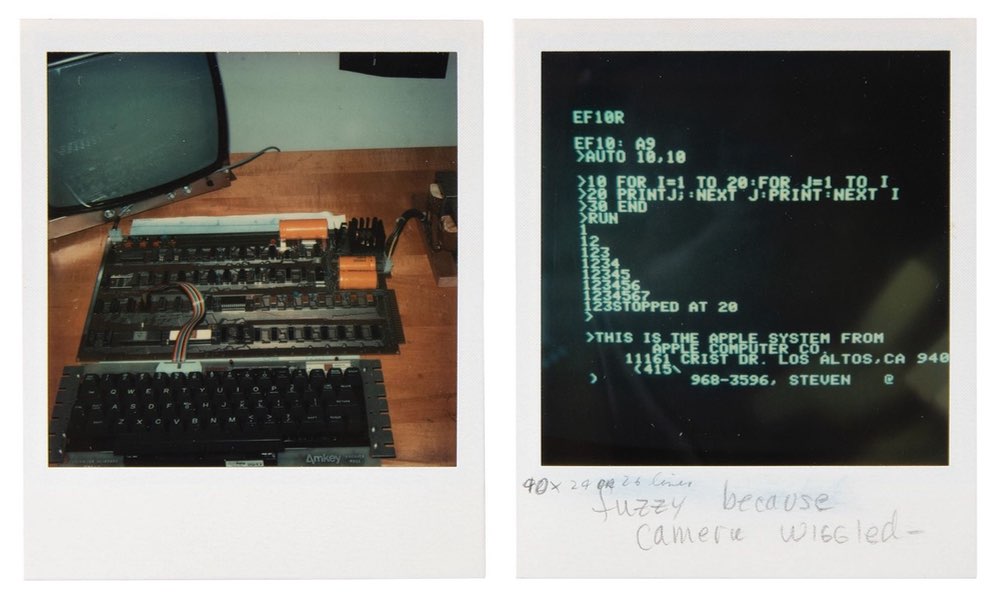

That's exactly what happened when John Chovanec, Steve Jobs' stepbrother, opened the door to the house in Los Altos Hills where the first Apple computers were assembled in the garage. Inside that childhood bedroom were decades of artifacts: notebooks, 8-track tapes, magazines, a handwritten horoscope, even a dozen bow ties Jobs wore in high school. These aren't museum pieces. They're the everyday objects of a person before he became a legend.

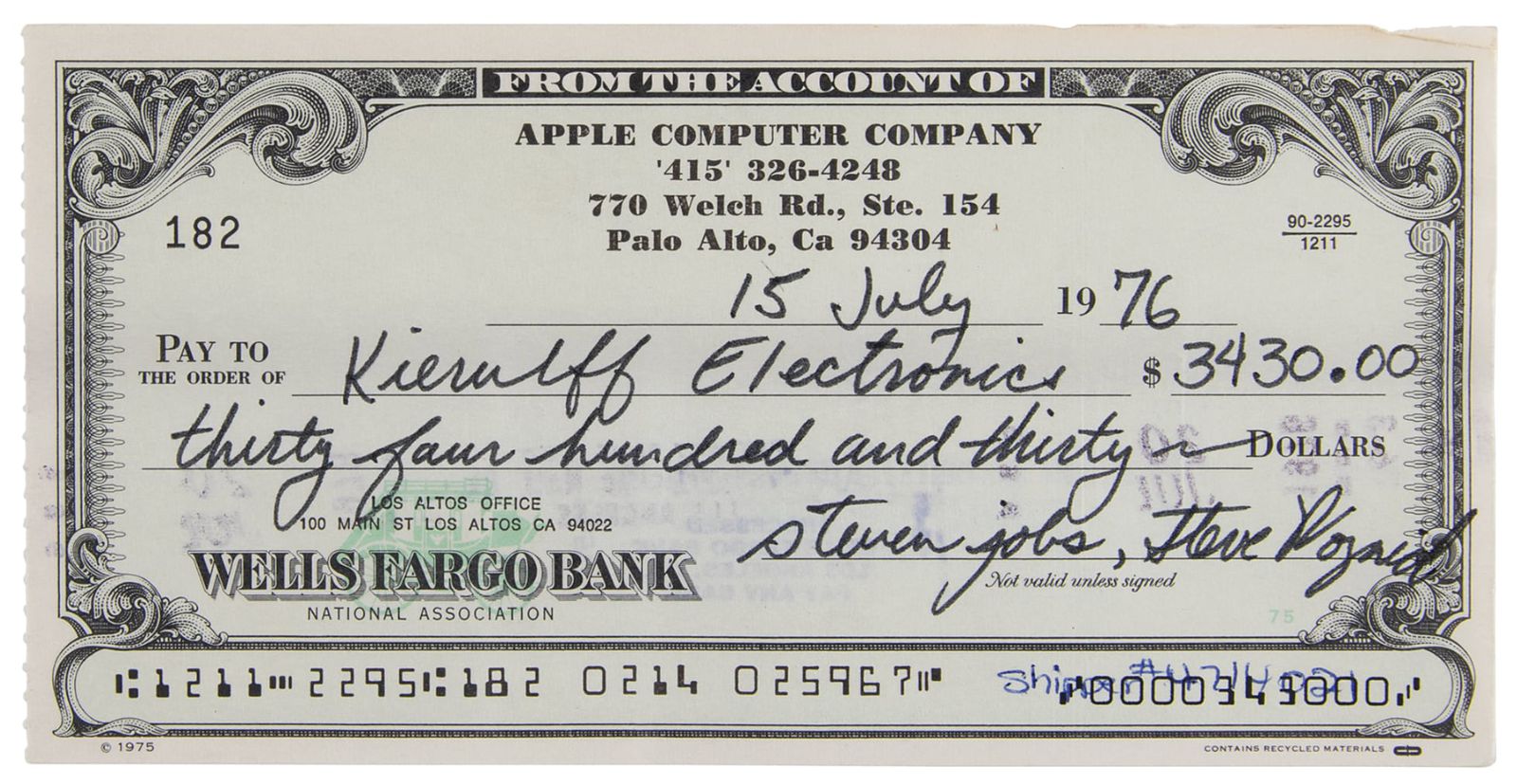

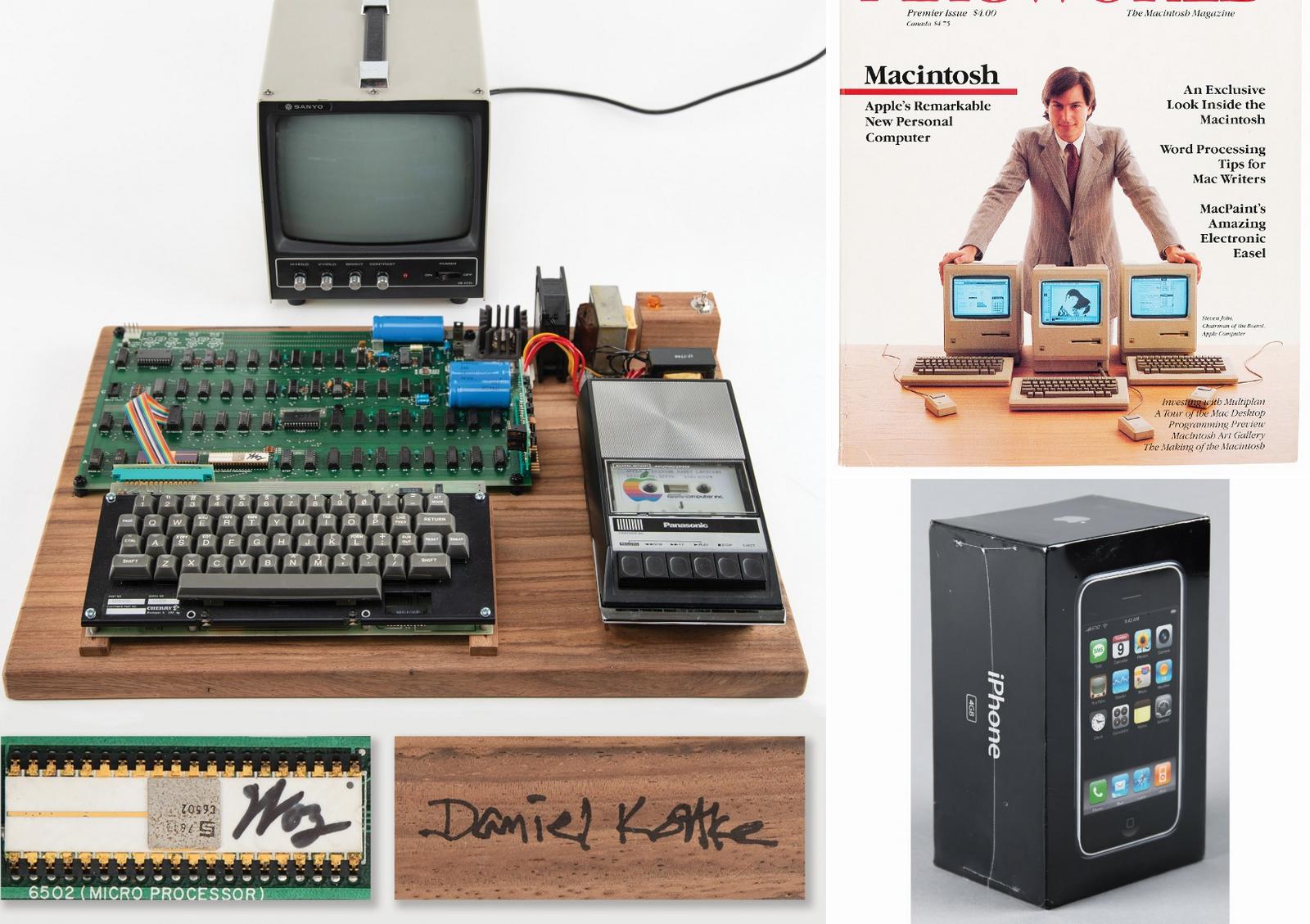

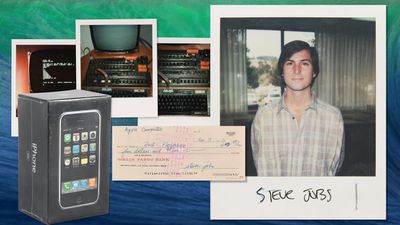

Now, in 2025, a significant portion of these items are going to auction through RR Auction, alongside what might be the most important piece of Apple history ever to hit the market: the first check ever cut by Apple Computer Inc., signed by both Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak on March 16, 1976. That check, written for $500 to circuit-board designer Howard Cantin, predates Apple's official partnership agreement by 18 days and represents the literal moment when the company began conducting business.

This auction tells multiple stories at once. It's a window into Jobs' formative years before Apple, a testament to how Wozniak and Jobs started their company with borrowed money and sold possessions, and a reflection of how the world has transformed Steve Jobs' legacy into something almost sacred. The items command astronomical prices because they represent more than historical artifacts. They're talismans of innovation, ingenuity, and the garage entrepreneurship that became Silicon Valley's founding mythology.

But there's more to explore here than just the headline numbers. The auction reveals surprising truths about Jobs' personality, his relationship with material possessions, and what actually mattered in those early days. It also raises fascinating questions about how we value history, why we're willing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for scraps of paper, and what these artifacts really mean in an age when digital technology has replaced the physical objects that once mattered so much.

TL; DR

- The first Apple check (March 16, 1976) signed by Jobs and Wozniak is expected to sell for approximately $500,000, more than three times the price of the second Apple check sold in 2023

- Steve Jobs' personal items from his childhood bedroom include his desk, notebooks, 8-track tapes, magazines, and a dozen high school bow ties consigned by his stepbrother John Chovanec

- Jobs' signatures are among the most valuable of any public figure because he famously refused to sign items, making even simple business cards worth six figures

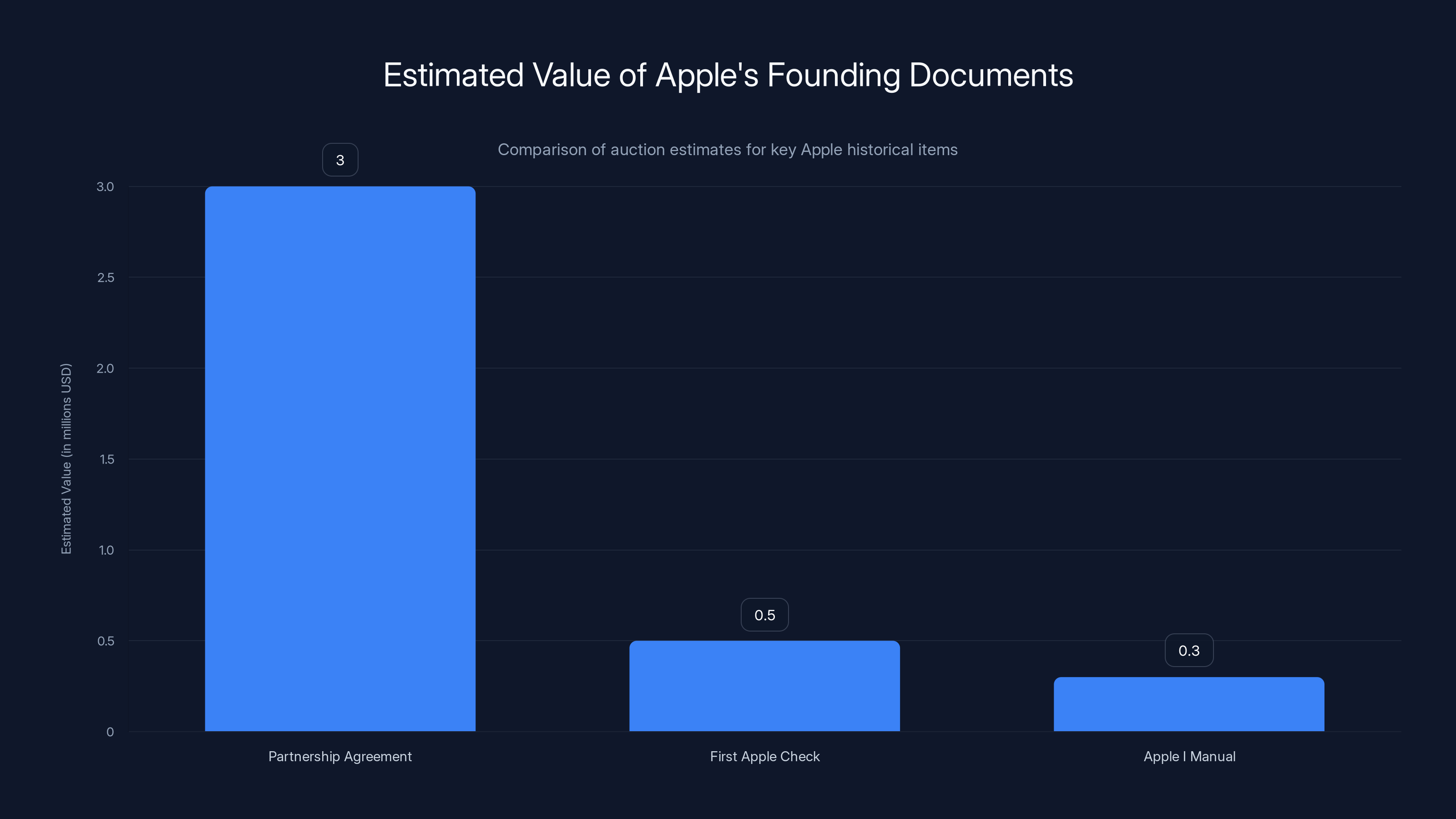

- Apple partnership agreement signed April 1, 1976 (between Jobs, Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne) is expected to sell at Christie's for 4 million

- The collection reveals Jobs' personality: his indifference to material possessions, his eclectic taste in music (Bob Dylan and Joan Baez), and his interest in Eastern philosophy and counterculture

The partnership agreement is expected to fetch significantly more than the first check due to its historical significance, rarity, and the prestige of the auction house. Estimated data.

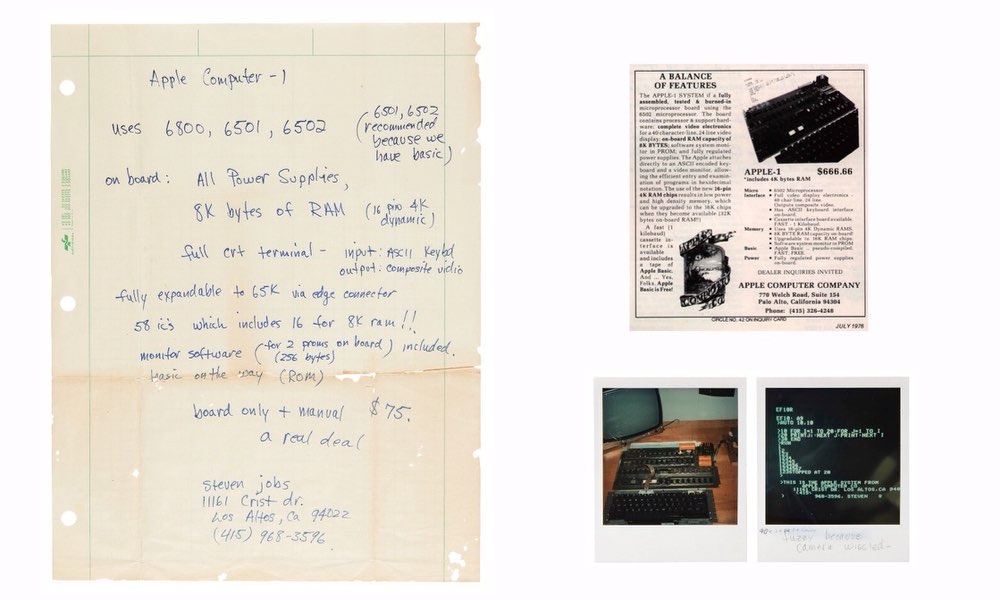

The First Apple Check: Why a 500,000

On March 16, 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak wrote a check for $500 to Howard Cantin, a circuit-board designer. This wasn't a glamorous moment. There was no ceremony. Cantin had designed the circuit board for what would become the Apple I computer, and rather than accept stock options in a company that didn't officially exist yet, he wanted cold cash.

Jobs and Wozniak paid him from a Wells Fargo bank account funded by the sale of Jobs' Volkswagen bus and Wozniak's Hewlett-Packard calculator. They were using their personal assets to fund the company's first expenses. It's a detail that sounds almost quaint now, when Apple's market cap exceeded $3 trillion at various points in the 2020s. Two kids selling their possessions to pay their first contractor.

But that check is incomparably rare. It predates Apple's formal partnership agreement by 18 days. It predates the company's legal existence. It's the earliest documented transaction showing Jobs and Wozniak conducting business as "Apple Computer Inc." Previously, the earliest check to reach the auction block was check #2, written three days later to Ramlor Inc., a circuit-board maker. That check sold for

Why is a half-century-old check worth half a million dollars today? Several factors converge. First, there's extreme rarity. Only two cofounders have ever signed it, and Jobs' signature alone is worth more than most historical figures' signatures because he so rarely signed anything. Second, there's narrative power. This single piece of paper represents the moment when the most valuable company in human history began. It's not just a check. It's an origin story artifact.

But there's a third reason that's more subtle and more interesting. Steve Jobs has become something more than a businessman or inventor. He's become a cultural icon whose personal objects carry a weight that transcends their practical function. Collectors aren't just buying a piece of paper. They're buying a connection to a moment, a person, and a mythology.

Wozniak himself has been surprisingly uninterested in preserving Apple memorabilia. In correspondence with auction experts, he revealed that he had extensive documentation of his development work arranged chronologically in 50 numbered manila folders, but he handed them over to lawyers representing Apple in an early copyright suit and never saw them again. "Bummer," he noted, suggesting he's content with his memories rather than physical artifacts. Wozniak's indifference to collecting makes the first check's appearance at auction all the more significant. It didn't come from him, and he's the one person who could have authenticated its creation with absolute certainty.

The original Apple partnership agreement is estimated to sell for $2-4 million, reflecting its historical significance. Estimated data.

How John Chovanec Ended Up With Steve Jobs' Childhood Bedroom

The story of how these items came into John Chovanec's possession is unusual and deeply personal. In 1990, Chovanec's mother married Paul Jobs, Steve Jobs' father. This wasn't a circumstance that brought Chovanec and his famous stepbrother close. According to Chovanec, they were never particularly intimate, though their interactions remained cordial.

One memorable occasion stands out: Jobs took Chovanec into his childhood bedroom and fired up an early Macintosh to show him a personal chronicle of how it was developed. It was a rare glimpse into Jobs' reflective side, the part of him willing to explain how things worked and why they mattered. But it was also oddly formal. Instead of a casual conversation between family members, Jobs used a computer to tell the story of his computer.

When Paul Jobs died, Steve assured Chovanec's mother, Marilyn, that she could live in the house "until you drop." Despite his attachment to the garage where Apple's history was made, Steve Jobs showed remarkably little sentiment about the bedroom itself. When Chovanec asked what Jobs wanted to do with the contents of the room, Steve reportedly told him to just take it. Chovanec's mother remained in the house until her death in 2019, at which point the desk and other items that had been stored in Chovanec's garage for years became his responsibility.

Interestingly, Chovanec himself worked at Apple for 16 years, starting in 2005 in the supply chain section before moving to the retail group. He deliberately kept his family relationship to Jobs secret, feeling that it was nobody's business. During his tenure at Apple, few colleagues knew he was Jobs' stepbrother. When he attended Jobs' memorial service at Stanford in 2011, he recalls that some executives gave him curious looks, as if wondering what connection he had to the company's late founder.

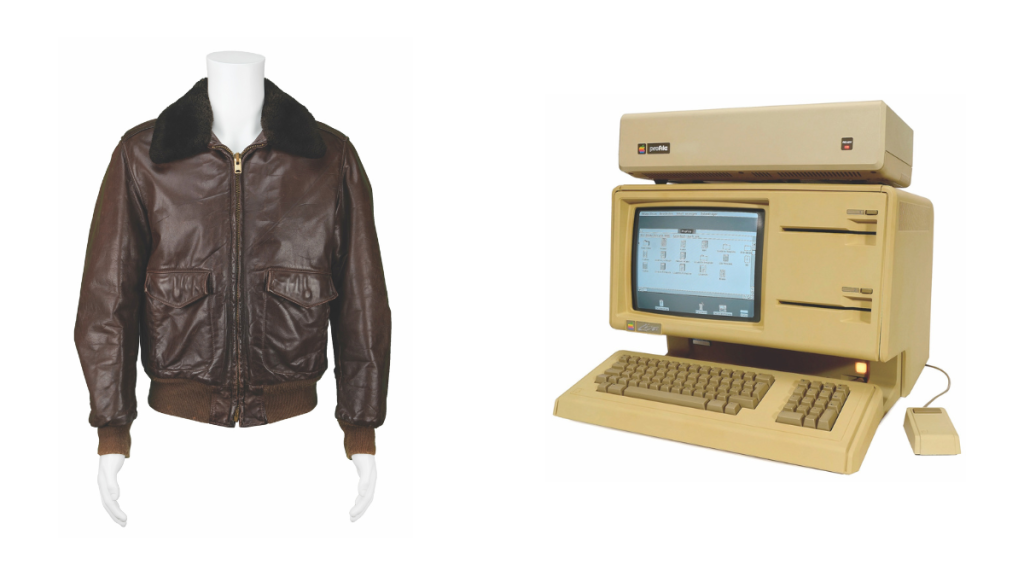

Chovanec wasn't initially squeamish about consigning these personal items. He noted that previous auctions had included items like a bomber jacket Jobs was once photographed wearing. "Steve didn't want any of this stuff," Chovanec explained. "My kids didn't want anything. It's just sitting here gathering dust and I want other people to enjoy it. It's the 50th anniversary of Apple, and there are collectors out there who would really appreciate those types of things." This pragmatic approach contrasts sharply with the reverence such items now command.

Chovanec is not in contact with the Steve Jobs Archive or with Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve's widow. The last time he saw her was at the memorial service in 2011. This separation highlights how the narrative around Jobs has become somewhat removed from his actual family, mediated instead through official archives and market forces that determine what items deserve preservation.

The Steve Jobs Signature Premium: Why His Autograph Is Worth More Than Celebrities'

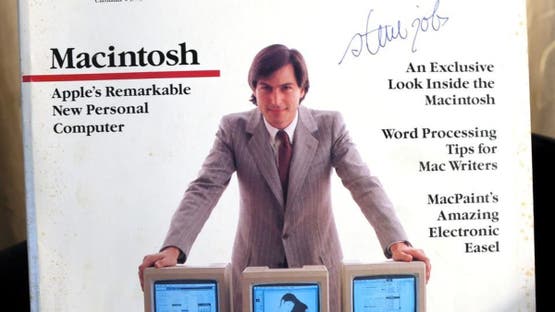

One of the most striking facts about Steve Jobs memorabilia is how much his signature commands compared to other famous figures. A signed business card from Jobs can fetch six figures. The two signatures on the first Apple check represent an exponential multiplier on the check's value. Why is Jobs' signature so valuable when signatures from celebrities, athletes, and other famous people are often readily available and relatively inexpensive?

The answer reveals something fundamental about how we assign cultural value. Steve Jobs famously refused to sign things. He was notoriously unsentimental about autographs and memorabilia. This resistance to signing created artificial scarcity. Whenever something is signed by Jobs, it becomes a rarity by default. There's no flood of signed Jobs items on the market because he simply didn't sign very much during his lifetime.

Compare this to someone like Michael Jordan or Elvis Presley, who signed thousands of items, both officially and unofficially. The sheer volume of signatures diminishes the scarcity premium. Jobs' signature carries an additional burden of cultural weight. He's not just a celebrity. He's positioned as a visionary, an artist, someone whose personal choices and aesthetic judgments fundamentally shaped technology. When you own something signed by Jobs, you're not just owning an autograph. You're owning a piece of his intentional choices.

There's also the question of authenticity and market psychology. Signed Jobs items become investment vehicles. Collectors who own them can point to rising prices over time as validation of their purchase. RR Auction's executive vice president Bobby Livingston noted, "There's an emotional connection between Steve Jobs and collectors. People who start their own internet or engineering companies love Apple products." This emotional connection translates into willingness to pay premium prices.

Lonnie Mimms, who owns Apple check #2 and founded a tech museum in Roswell, Georgia, explained the hierarchy of signatures in Apple history. "You can get anything in the world with a Steve Wozniak signature on it, but Jobs is another story. And the two of them together is the highest form of rarity." This observation captures the market dynamics perfectly. Wozniak's signature, while valuable, is more available than Jobs'. The combination of both signatures creates a scarcity that drives prices upward exponentially.

The first Apple check benefits from triple-layer rarity: it's the first check, it's signed by both founders, and it represents a unique moment in business history that can never be replicated. These factors combine to create something that approaches religious relic status for certain collectors.

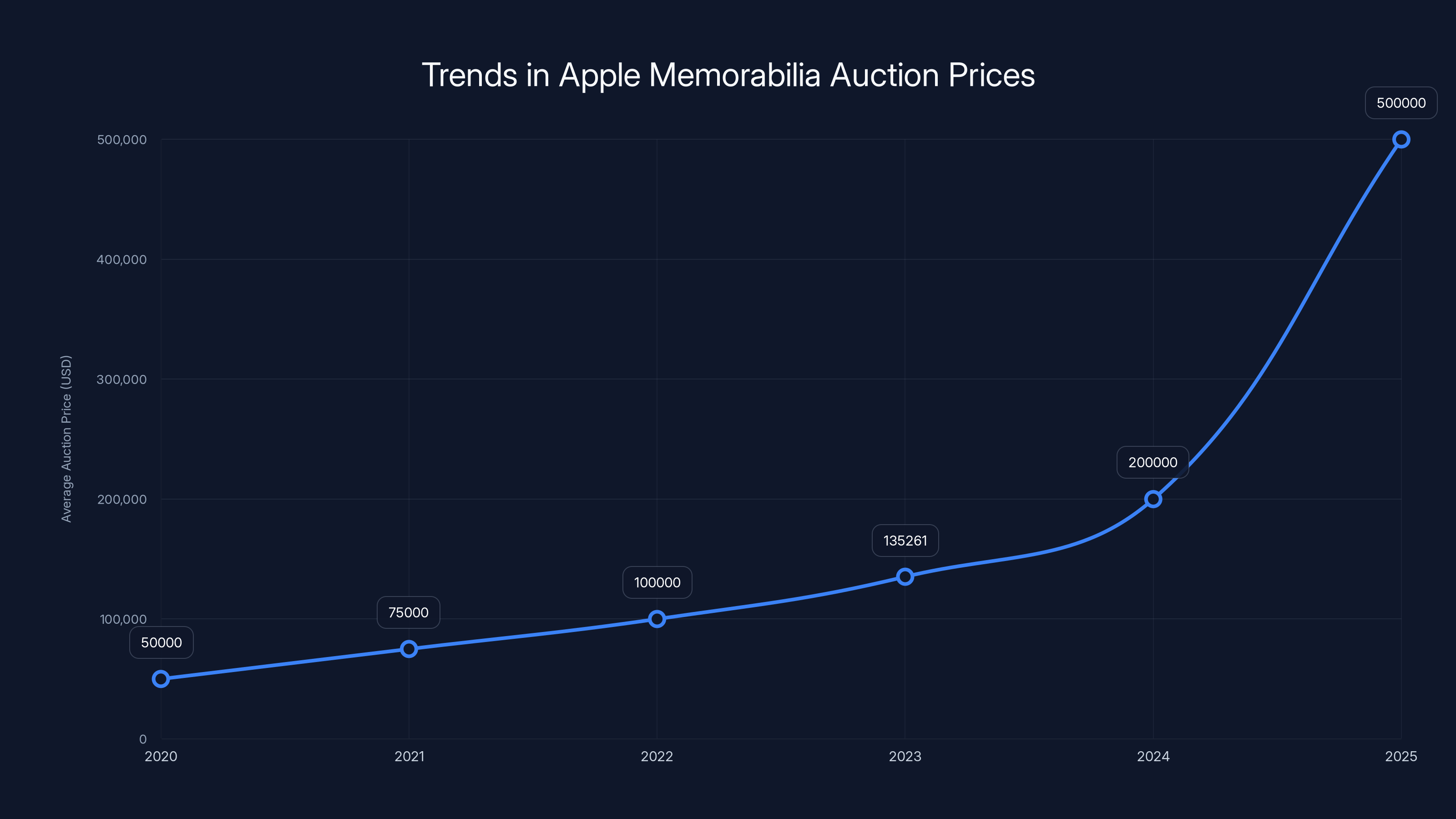

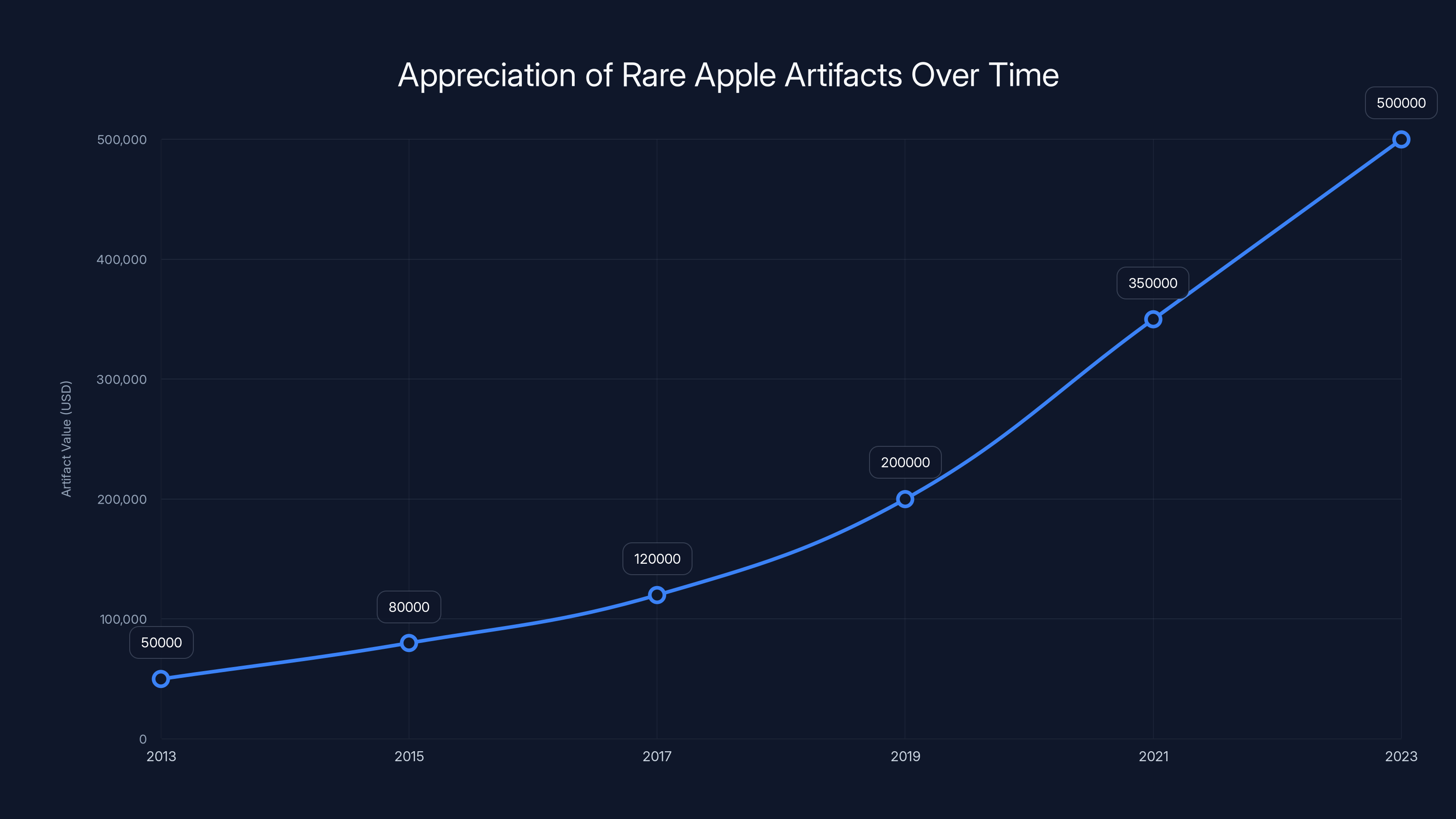

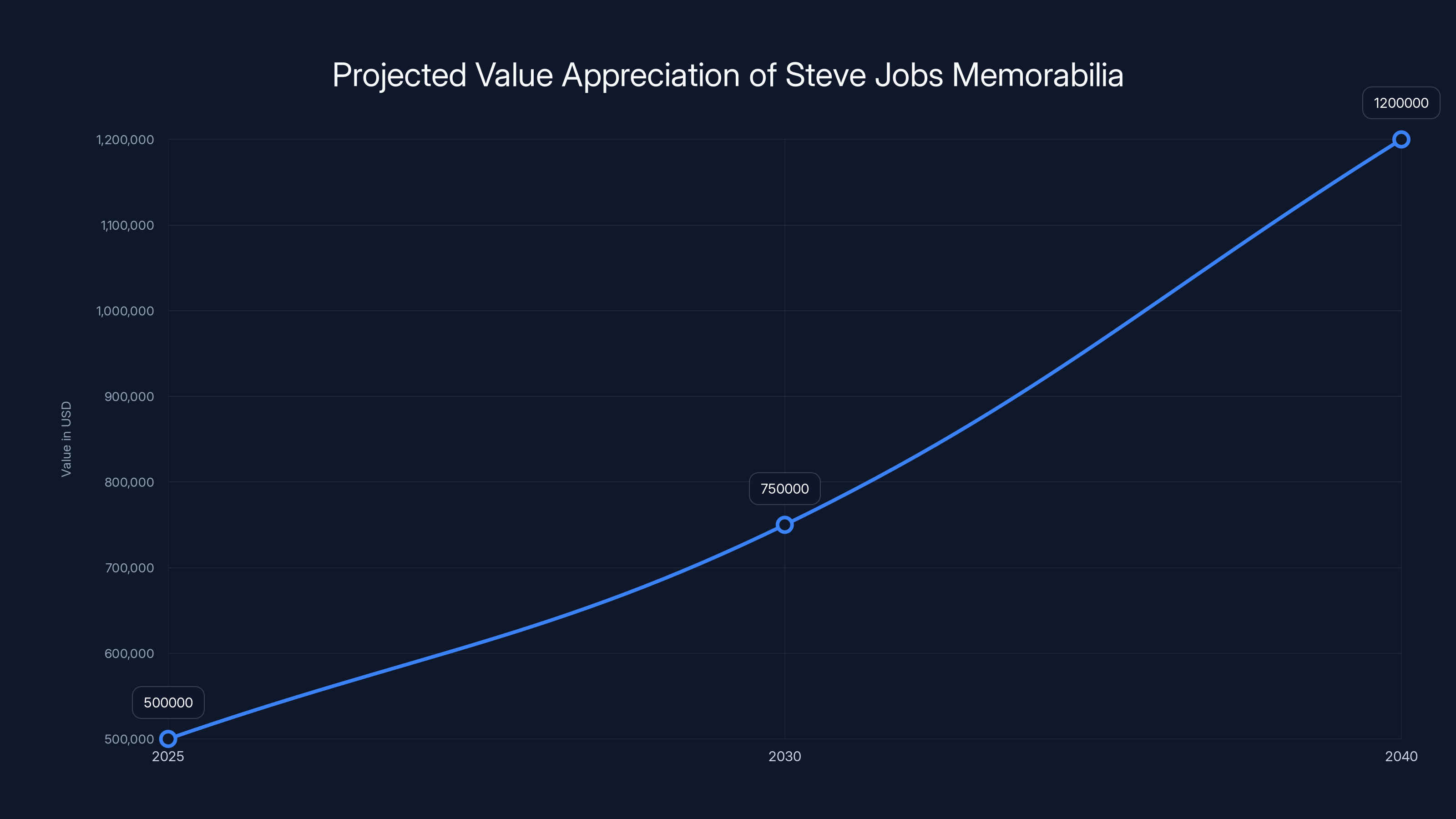

Apple memorabilia prices have surged, with projections showing a significant increase by 2025, driven by collector demand and item scarcity. Estimated data based on auction trends.

Steve Jobs' Personal Items: The Objects That Reveal Character

Beyond the first check, the items consigned by John Chovanec tell a different story about Steve Jobs. They're less about business history and more about personality. The collection includes his desk from the childhood bedroom, filled with Reed College notebooks and work he did for Atari in the mid-1970s. These notebooks offer tangible evidence of his creative process, his handwriting, his concerns during a formative period.

The most striking items are perhaps the least glamorous: twelve bow ties that Jobs wore in high school. These are fragments of teenage fashion choices, the kind of everyday object most people discard without thinking. But they carry unexpected weight. They reveal that even before Apple, before Pixar, before becoming a design perfectionist, Jobs had developed a distinctive personal aesthetic. The bow ties suggest someone thinking about how he presented himself to the world, which is deeply consistent with the public persona he cultivated later.

Then there are the 8-track tapes: Bob Dylan and Joan Baez albums that Jobs listened to incessantly. This music collection is significant because it grounds Jobs in a specific cultural moment and reveals his aesthetic preferences. Dylan and Baez represent counterculture, poetic lyricism, and artistic rebellion. They suggest Jobs saw himself as connected to artists and musicians, not just engineers and businessmen. This musical sensibility likely influenced his later insistence that Apple products should be as beautifully designed as they were functionally powerful.

The collection also includes a handwritten horoscope generated by an Atari computer, which speaks to Jobs' interest in Eastern philosophy, mysticism, and the intersection of technology and spirituality. He kept a copy of "How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive: A Manual of Step-by-Step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot," which seems fitting for someone who would sell his VW bus to fund Apple. The manual represents a DIY ethos, a belief that anyone with sufficient determination could understand and repair complex systems.

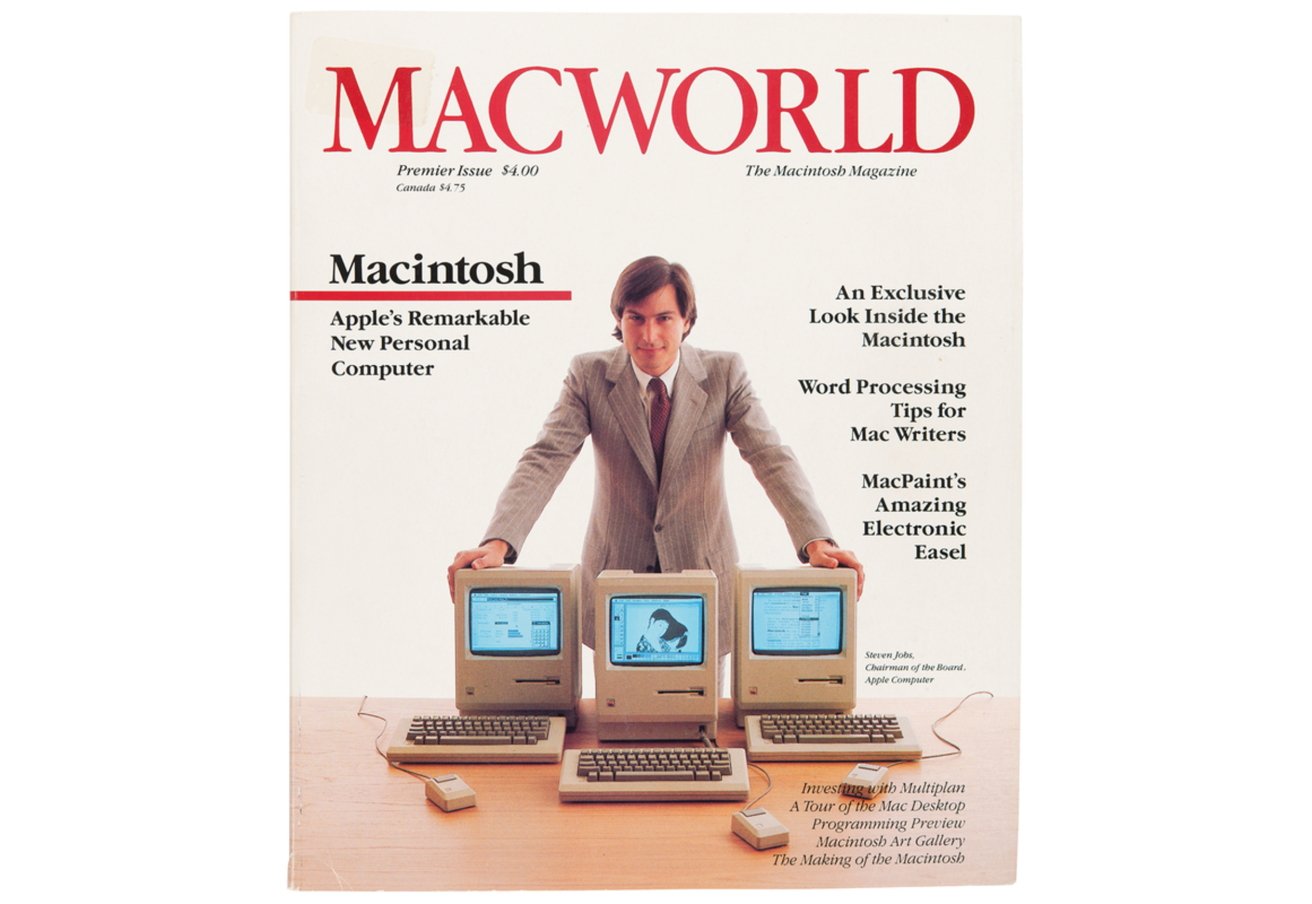

Magazines that Jobs' father kept to commemorate cover stories about his son reveal an interesting family dynamic. Paul Jobs was clearly proud of his son's accomplishments, preserving these moments in paper form. The early Apple poster that hung in the house shows how Apple's growth from garage project to recognizable brand happened incrementally, through marketing efforts that eventually reached Jobs' own home.

A document Jobs signed related to the sale of his father's 1984 Ford Ranger pickup is mundane on its surface but interesting for what it reveals about family relationships. This isn't a business document. It's evidence of Jobs managing personal family matters, dealing with logistics and practical concerns that don't fit the image of a visionary entrepreneur.

Collectively, these items paint a portrait of someone before mythology took over. They show a person interested in music, design, Eastern philosophy, and counterculture. They show someone developing a distinctive personal style and aesthetic. They show a family man dealing with practical matters. The objects are most valuable because they allow us to see Jobs as he was, not as the legend he became.

The Christie's Partnership Agreement: The Legal Document Worth Millions

While RR Auction is handling the Chovanec collection and the first Apple check, another auction house is offering what might be an even more historically significant document: the original partnership agreement between Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne, signed on April 1, 1976. Christie's is offering this document in a sale called "We the People: America at 250," which features "works of art, furniture and documents that changed American history."

The partnership agreement is estimated to sell for between

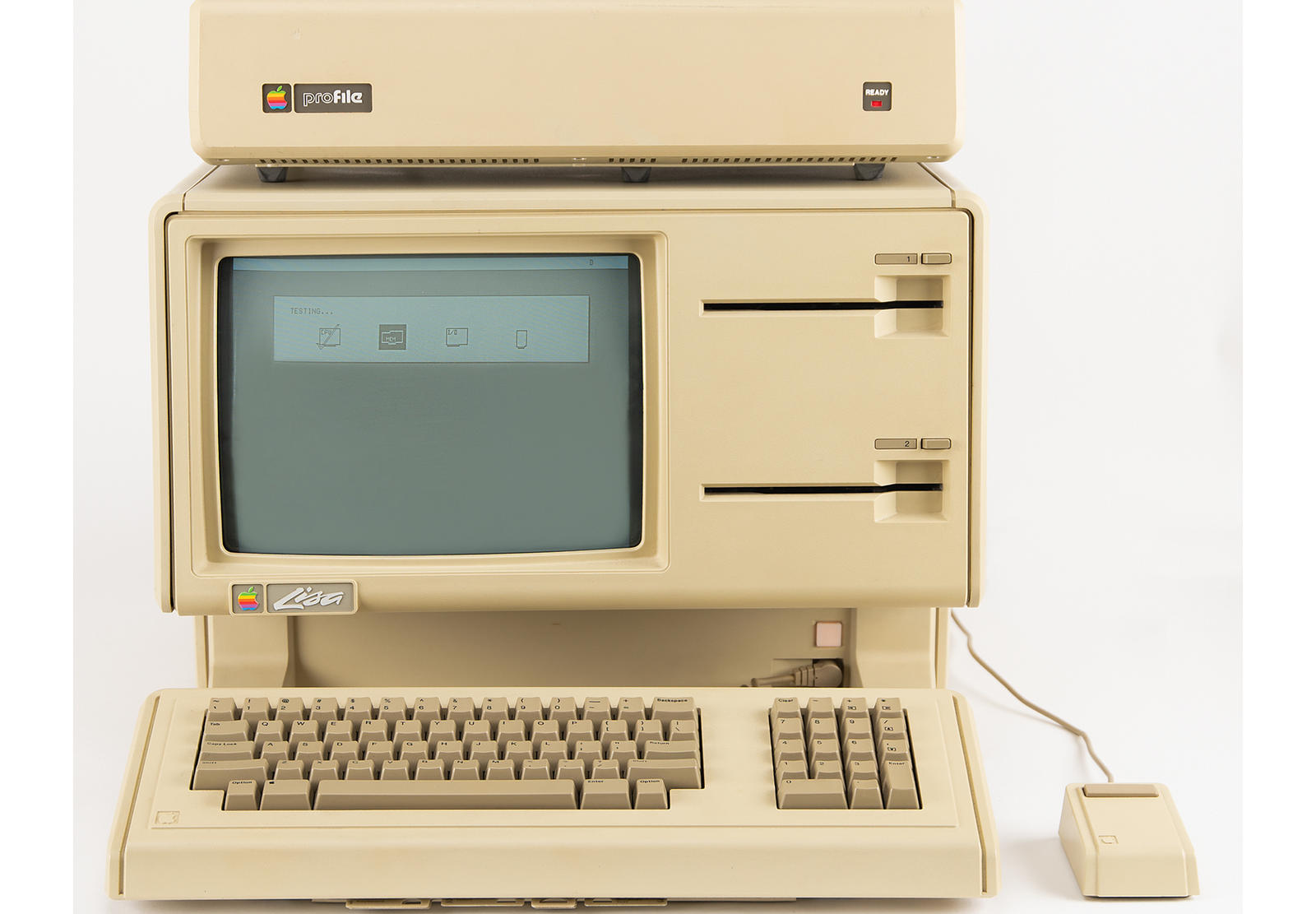

Ronald Wayne is a fascinating figure in Apple history, often overlooked in the narrative that centers on Jobs and Wozniak. Wayne designed the first Apple logo and wrote the Apple I manual. But he got cold feet about the partnership shortly after signing. Fearing potential liability and uncertain about the venture's prospects, Wayne sold his 10 percent stake to Jobs and Wozniak for $800. In retrospect, this decision was catastrophically expensive. Had Wayne held onto that 10 percent, his stake would be worth hundreds of billions of dollars today.

The partnership agreement itself is a modest document, handwritten or typewritten, lacking the formality of modern corporate agreements. But it contains all the essential elements: the names of the partners, the date of formation, the ownership structure, and the agreement terms. The document's simplicity reflects the casual nature of how these companies were founded in the 1970s. There was no venture capital, no business lawyers, no formal startup infrastructure. Just three people writing down what they'd agreed to verbally.

The fact that Christie's is positioning this document as part of American history, alongside artworks and furniture that changed the nation, reflects how Apple's founding has transcended business history to become cultural mythology. The partnership agreement belongs in the same category as the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, at least in how it's being framed and valued.

The April 1, 1976 date is also significant. It's not arbitrary. It marks the 18-day gap between when Jobs and Wozniak began conducting business as Apple (March 16, the date of the first check) and when they formalized that relationship legally. During those 18 days, they were operating without official partnership status, which was actually somewhat risky from a legal perspective. Paying Cantin through a bank account in neither of their individual names was a pragmatic solution to a problem they probably hadn't fully thought through.

The first Apple check, valued at

The Broader Apple Memorabilia Market: Prices and Trends

The Jobs artifacts heading to auction in 2025 aren't happening in isolation. They're part of a broader trend in which Apple memorabilia has become increasingly valuable and sought-after. This market has exploded in recent years, with prices reaching levels that seem almost absurd for objects that cost pennies to produce.

Before the first Apple check hit the market, check #2 sold for

Other Apple artifacts have also commanded high prices. An early Apple I computer in working condition recently sold for tens of thousands of dollars. Handwritten design sketches, prototype parts, and early documentation routinely fetch thousands to hundreds of thousands at auction. The market dynamics are driven by several factors: the scarcity of authentic items, the cultural significance of Apple's founding, the investment appeal of rare memorabilia, and the emotional connection people feel to Apple products.

Collectors often fall into specific categories. Some are tech enthusiasts and engineers who want to own a piece of computing history. Others are investors who view rare Apple items as alternative assets that appreciate over time. A third category consists of extremely wealthy individuals who have such extensive collections that they're essentially curating private Apple museums. A fourth category is museums and institutions that acquire these items for preservation and public education.

The market has also benefited from increased awareness and market access. Online auction platforms and specialized dealers have made it possible for collectors worldwide to participate in bidding, rather than having to attend physical auctions. This global audience has driven prices upward across the board.

One interesting dynamic is that not all Apple memorabilia commands equal prices. Items directly associated with Steve Jobs are worth more than items simply from the Apple era. Items signed by Jobs or Wozniak are worth more than unsigned items. Working prototypes are worth more than broken examples. And items with clear provenance from direct sources are worth more than items with murky ownership histories.

The Chovanec collection benefits from exceptional provenance. These items came directly from Jobs' family, stored in Jobs' childhood home, and are being sold with documentation from a family member with credible knowledge of their authenticity. This provenance is worth a substantial premium, as it eliminates questions about authenticity or proper storage that plague other sales.

Why These Objects Matter More Than Their Practical Function

At a fundamental level, these artifacts are just objects. A check is a piece of paper. A bow tie is cloth and thread. A notebook is bound pages. They have no functional value anymore. Steve Jobs is dead. Apple has trillions in market value. The company doesn't need these artifacts to continue operating or to establish its place in history. Yet people are willing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for them.

This willingness to pay reveals something important about how humans assign meaning. We're not economic creatures making purely rational decisions about utility and value. We're symbolic creatures who use objects to connect with narratives, people, and moments that matter to us. These artifacts function as reliquaries, objects that allow us to touch something sacred by extension.

There's also the psychological phenomenon of parasocial relationships. Many people feel a profound connection to Steve Jobs and Apple, even though they never met him and the relationship is entirely one-directional. Jobs' products shaped millions of people's daily lives. His presentations were watched by millions. His design philosophy influenced an entire generation of engineers and designers. For people who grew up with Apple products, Jobs is a figure who mattered immensely, even though he never knew they existed.

Owning an artifact associated with Jobs allows collectors to transform that parasocial relationship into something tangible. It's a way of saying, "I own a piece of something that he touched, that he valued, that he created." The artifact becomes a bridge between the collector and the person they admire.

There's also the investment angle. Rare Apple artifacts have appreciated substantially over the past decade. Someone who bought check #2 for

But perhaps the deepest reason these objects matter is that they're vanishingly rare evidence of a specific moment in technological and cultural history. The first check is the last remaining physical artifact of Apple's literal first transaction. The partnership agreement is the original legal document that founded the company. Jobs' personal items are fragments of his inner life before he became a public figure. In an age of digital documentation, physical artifacts carry a weight that's almost antique in its power.

The value of rare Apple artifacts has significantly increased over the past decade, indicating strong market interest and appreciation. (Estimated data)

The Role of Provenance in Authentication and Valuation

When an auction house evaluates artifacts, provenance becomes the primary determinant of authenticity and value. Provenance is the documented history of an object's ownership and whereabouts. For the Chovanec collection, the provenance is exceptionally strong. These items came from Steve Jobs' childhood bedroom, remained in the family home until 2019, and are being sold by a direct family member who can testify to their authenticity.

This direct provenance is worth a substantial premium. Compare this to items of uncertain origin or items that have changed hands multiple times. A check with unknown provenance might be authentic but would sell for a fraction of what an authenticated version would command. Collectors and institutions require documentation that establishes a clear chain of custody.

For the partnership agreement being sold at Christie's, provenance is also crucial. The auction house needs to establish how the document has been preserved and who has had custody of it. If it came directly from Ronald Wayne or from someone Wayne designated, the provenance is strong. If it passed through multiple hands over 50 years, questions arise about authenticity and proper preservation.

Authentication itself can involve multiple methods. For documents, experts examine paper quality, ink composition, handwriting analysis, and signatures. They compare the document to known examples to establish consistency. They research historical records to verify that the transaction documented actually occurred. They consult with people who were present at the time or who have detailed knowledge of the event.

For the first check, RR Auction would need to verify that the Wells Fargo bank account existed, that funds were deposited from the sale of Jobs' VW bus and Wozniak's HP calculator, and that the check was actually processed and cleared. They would need to verify Cantin's role in designing the Apple I circuit board and confirm that he received payment for this work. They would need to examine the signatures and compare them to authenticated examples of Jobs' and Wozniak's signatures from the same period.

The story of how the check came into current ownership would also matter. If the current owner has possessed it for decades and can document that possession, the provenance is strengthened. If it's a recent acquisition, questions arise about where it's been and how it's been stored.

Interestingly, the provenance of some Apple items remains unclear even as they command high prices. Steve Wozniak revealed that he handed his extensive documentation over to Apple's lawyers in an early copyright suit and never saw it again. Those materials are presumably in Apple's archives, but they're not publicly accessible. This illustrates how provenance and preservation are intertwined. Items that are preserved in institutional archives are documented but often not available for sale. Items available for sale are often less documented than they might be if they'd been institutionalized.

Steve Jobs' Relationship With Material Possessions and Sentimentality

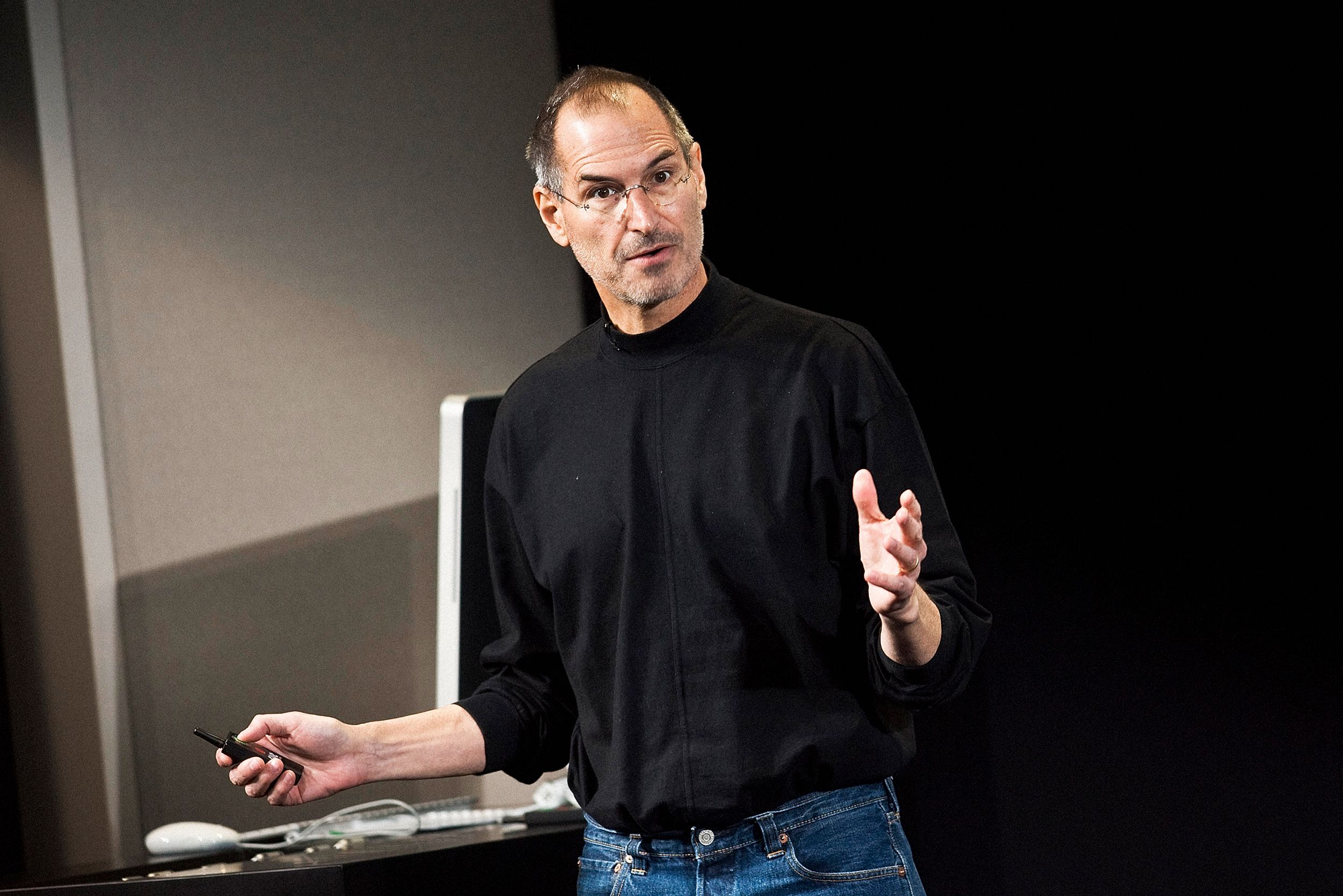

One of the more interesting aspects of this auction is what it reveals about Steve Jobs' relationship with his own material possessions. Throughout his life and career, Jobs cultivated an image of someone who transcended material concerns. He was famous for his ascetic lifestyle, his adoption of Eastern philosophy, his belief that design should be invisible and products should be elegant and minimal.

Yet the fact that he kept his childhood bedroom intact, full of notebooks and memorabilia from his formative years, suggests he wasn't entirely indifferent to the past. The notebooks filled with his Atari work and Reed College notes suggest he valued documentation of his creative process. The magazines his father kept, the early Apple poster on the living room wall, these items show that Jobs lived within a home that acknowledged his achievements.

But when it came time to do something with these items, Jobs showed minimal attachment. When his stepmother was invited to stay in the house after Paul Jobs died, Steve didn't try to preserve his childhood bedroom as a museum. When John Chovanec asked what to do with the contents, Steve told him to just take it. This suggests a profound indifference to physical artifacts. Jobs wasn't interested in converting his childhood bedroom into a shrine to his accomplishments.

This indifference extended to his professional life. Jobs was notoriously reluctant to sign items, giving fans and collectors minimal material evidence of his existence beyond the products he created. He didn't seem to value his own autograph or to believe that signed items were worth preserving. His signature appears on relatively few documents, which is precisely why his signatures are so valuable now.

There's a philosophical consistency here. Jobs believed that great design was about the product itself, not about the designer's ego or personal brand. He wasn't interested in self-promotion or in creating artifacts that glorified himself. He was interested in the work itself. The products were supposed to speak for themselves. His personal items and signatures were secondary.

This stance is almost admirable in a culture of relentless personal branding and social media self-promotion. Jobs refused to monetize his image or to preserve his own history in the way a more ego-driven entrepreneur might have done. He left that task to others, to collectors and institutions and biographers. He focused on making products.

Of course, this indifference also means that the items that do exist are vanishingly rare. If Jobs had been more interested in signing things and preserving artifacts, there would be many more Jobs items in circulation. The very scarcity that makes his signature valuable is a direct result of his philosophical commitment to the product over the person.

Estimated data shows potential appreciation of Steve Jobs memorabilia, reflecting cultural and investment value.

How the Steve Jobs Archive Fits Into This Story

John Chovanec mentioned that he's not currently in touch with the Steve Jobs Archive or with Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve's widow. This raises an interesting question about how Apple's official history is being managed and who controls it.

The Steve Jobs Archive was established with Laurene Powell Jobs' support and has preserved materials related to Jobs' life and work. The Archive aims to create a comprehensive record of Jobs' contributions to technology, design, business, and culture. It's focused on long-term preservation and scholarly access, rather than on commercial sale.

The existence of an official archive raises questions about what items should be publicly accessible versus what should be privately held or sold at auction. The Archive presumably has acquisition budgets and interest in preserving historically significant items. Yet in this case, the most important items (the first check, the partnership agreement, Jobs' personal possessions) are being handled through commercial auction channels rather than being acquired by the Archive.

This creates an interesting dynamic. The official record-keeper (the Archive) is not acquiring the most historically significant artifacts. Instead, they're being dispersed to wealthy private collectors. This is partly a practical matter. The Archive probably doesn't have the financial resources to bid against private collectors for items valued at hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars. But it's also a philosophical question about whether culturally significant items should be publicly or privately held.

Museums and institutions often acquire important artifacts to preserve them and make them accessible to the public. A private collector, by contrast, might keep an item in their home or office, sharing it only with visitors they invite. From a public access perspective, museum acquisition is preferable. But from a market and valuation perspective, auction to private collectors is preferable, as it establishes market prices and demonstrates value.

The fact that Chovanec is not in touch with the Archive or with Laurene Powell Jobs suggests that the family and the official Archive may not be actively engaged in acquiring these personal items. This could be a strategic decision (letting the market establish value before deciding whether to acquire items for the Archive) or it could reflect a lack of coordination between the Archive and family members who possess artifacts.

Laurence Powell Jobs was notably absent from discussions about the auction. She hasn't commented publicly on her husband's items being sold at auction. This silence could reflect a desire to avoid controversy, respect for Chovanec's decision to sell, or simply a lack of interest in the commercial market for Jobs artifacts. Regardless, it's notable that the widow of the man whose items are being sold is not a visible participant in the auction narrative.

The Comparison: First Check vs. Partnership Agreement

Two major Apple founding documents are being sold at approximately the same time, which allows for interesting comparison. The first Apple check through RR Auction is expected to fetch roughly

Why is the partnership agreement worth so much more? Several factors are at play. First, the partnership agreement is the original legal document that established Apple's formal structure. It's more historically significant than a check, which is just one transaction among many. Second, the partnership agreement comes from Christie's, a more prestigious auction house than RR Auction, which may drive higher prices among wealthy collectors. Third, the partnership agreement is being sold as part of a curated collection of documents that changed American history, which adds prestige and draws a different audience of collectors.

But there's also the rarity differential. There's only one original partnership agreement. There were potentially multiple checks issued, and this just happens to be the first. The partnership agreement is unrepeatable. The check, while important, is less unique in principle (though it happens to be the earliest in practice).

There's also the question of narrative power. The partnership agreement tells the complete story of Apple's founding, establishing the ownership structure and terms that would govern the company's growth. The check tells a narrower story about how the founders paid their first contractor. From a historical documentation perspective, the partnership agreement is more comprehensive and more valuable.

Finally, there's the signature dynamic. The first check has two signatures. The partnership agreement presumably has three (Jobs, Wozniak, and Wayne). Wayne's signature is rarer than the other two because he's been less of a public figure and his signature appears on fewer documents. The presence of all three founding signatures makes the partnership agreement more valuable in terms of signature rarity.

From an investment perspective, both documents should appreciate substantially over time. As the 50th, 60th, and 100th anniversaries of Apple's founding arrive, these documents will become increasingly historically significant. They may eventually find their way into a museum or major institution's collection, at which point they would be removed from the market and potentially valued even higher by collectors wanting to own one of the last remaining examples available for private purchase.

The Cultural Significance of Steve Jobs as an Icon

Underlying all of these auctions is a fundamental question about Steve Jobs' place in American culture. Why do we treat him differently from other business leaders or inventors? Why is his signature worth more than, say, Bill Gates' signature? Why do his personal items command prices that seem almost ceremonial in their excess?

The answer involves how Jobs has been positioned in the cultural imagination. He's not primarily understood as a businessman. He's understood as a visionary, an artist, a figure who transcended the ordinary bounds of entrepreneurship to become something more like a prophet or philosopher. His books are read with reverence. His presentations are studied as models of design and communication. His failure (being ousted from Apple) is viewed as a betrayal. His return is viewed as vindication. His death was mourned globally in a way that's rare for business figures.

This cultural status is partly deserved and partly constructed. Jobs did revolutionize personal computing, design, and the integration of technology into daily life. The products Apple created under his guidance were genuinely transformative. But part of Jobs' iconic status is also the result of careful image management, favorable biographies, and the human tendency to create larger-than-life figures who embody our values and aspirations.

Jobs himself was deeply aware of this dynamic. He cultivated his image carefully, controlled his public appearances, and understood the power of mythology and narrative. He wasn't just building computers. He was building a story about what computers could be and what they could mean in people's lives. That story-building was as important to his legacy as the actual technological innovation.

The auction of his personal items is partly a continuation of that story-building process. By treating his bow ties and notebooks and checks as sacred artifacts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, the market is essentially canonizing Jobs. It's saying that even his everyday objects, the things he wore and read and discarded, are worth preserving and venerating.

This raises philosophical questions about what we value and why. Is there something genuinely important about owning a bow tie that Jobs wore in high school? Does the artifact convey any information or utility that we couldn't get by reading a biography or watching a documentary? Or are we simply participating in an elaborate symbolic act, a way of expressing our admiration and connection to a figure we never met?

From a historical perspective, these artifacts do matter. They're primary sources that historians and researchers can examine to understand Jobs' actual life, not just the public version he presented. The notebooks show his actual handwriting and thinking. The music he listened to provides context for his aesthetic values. The documents he kept reveal what he considered important. These artifacts are richer and more revealing than secondary sources can be.

But from a collector's perspective, much of the value is probably symbolic and emotional rather than informational. The collector is paying for the privilege of connection, of owning something that Jobs owned, of participating in the mythology that's been built around him.

The Digital Age vs. Physical Artifacts: What Gets Preserved?

There's an interesting irony in the fact that we're agonizing over the sale of Steve Jobs' physical artifacts at a moment when the objects that mattered most to him were digital. Jobs spent his career trying to eliminate the physical barriers between people and the content they wanted to access. The iPad, the iPhone, the Mac, all of these were designed to be invisible, to get out of the way of the content and the user's intention.

Yet the things we're preserving and valuing are physical objects: notebooks, checks, clothing. The digital work that Jobs did, the actual computers he designed and the software he oversaw, are more obsolete and less accessible than his physical artifacts. You can examine his bow tie. You can study the check he signed. But trying to actually use an early Apple II computer involves working with hardware and software that's ancient and inaccessible.

This creates an interesting question about what future historians and collectors will value. In 100 years, will people be auctioning off the iPhones and MacBooks that Steve Jobs used? Will his digital files be preserved? Or will the physical objects be all that remains, while the digital work of his life fades away?

There's also the question of how objects get preserved and archived in the digital age. Before digital storage, preservation meant keeping physical artifacts: documents, photographs, recordings on tape or vinyl. Now, preservation often means digital storage on servers or cloud systems. But digital storage has its own challenges. Files become corrupted. Storage formats become obsolete. Cloud services shut down or change policies. Hard drives fail. The assumption that digital files are automatically preserved forever is actually quite risky.

This suggests that physical artifacts might actually be more durable than digital files in some respects. A paper notebook from 1975 is still readable. A check from 1976 is still intact. But digital files from that era are already largely inaccessible without specialized hardware and software. In that context, preserving Jobs' physical artifacts becomes a way of preserving the era he lived in, since the digital artifacts are already largely lost.

The auction of Jobs' items might actually be serving a preservation function that the digital age undermines. By placing these objects in markets where they're valued and sold, we're ensuring that they're kept in climate-controlled environments and handled carefully. They're being photographed and documented extensively. They're becoming known to researchers and institutions. The commercial market in these artifacts might actually be better preservation than if they'd simply been locked away in a private collection or forgotten in a garage.

What These Auctions Tell Us About Valuation and Worth

The prices being paid for Steve Jobs' artifacts reveal something important about how we assign value in contemporary culture. These aren't objects with obvious practical utility. A check from 1976 can't be spent. A 50-year-old notebook can't be written in. A bow tie from high school can't be worn comfortably by modern adults. Yet they command prices that far exceed their material cost or utility.

This reveals that value is not primarily about utility but about meaning, narrative, and cultural significance. The check is valuable because it represents a moment. The notebook is valuable because it offers insight into a person. The bow tie is valuable because it's an artifact of someone important. Economic value here is primarily cultural and symbolic value.

This dynamic applies to many markets beyond memorabilia. Fine art is valued not for its utility but for aesthetic and cultural meaning. Rare books are valuable not because you need the specific copy but because of scarcity and historical importance. Vintage wine is valuable not just for flavor but for age, provenance, and story. In all these cases, the price reflects something beyond the object's material properties.

What's interesting about the Jobs auction is that it's making this dynamic explicit. We're not hiding the fact that we're paying $500,000 for a piece of paper. We're openly acknowledging that cultural significance and narrative power justify extreme prices. This is actually more honest than pretending that value is entirely functional and rational.

There's also an investment angle worth considering. For wealthy collectors and institutions, acquiring these artifacts is partly about cultural participation but also partly about financial investment. Rare Apple memorabilia has consistently appreciated in value. Someone buying the first check for $500,000 in 2025 could reasonably expect it to be worth more in 2030 or 2040. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where prices rise because people expect prices to rise, and prices do rise because demand increases.

This speculative element is worth watching. If Apple's cultural significance begins to decline, if the company falls from its current position of dominance, if Jobs' iconic status fades, then the value of these artifacts could decline. But that seems unlikely in the near term. For the foreseeable future, Apple artifacts should continue to appreciate, making them attractive investments for wealthy collectors.

The Future of Steve Jobs' Legacy and Historical Artifacts

As we move further away from Jobs' death in 2011 and deeper into the 21st century, the market for his artifacts will likely continue to evolve. The 50th anniversary of Apple's founding (2026) will likely drive another wave of collecting interest. The 75th anniversary (2051) will create another cycle. As time passes and more artifacts surface, the market will mature and prices may stabilize or potentially fluctuate.

What's certain is that the items being sold in 2025 represent some of the most significant Apple artifacts that will ever be available for private purchase. The first check, the partnership agreement, and Jobs' personal items are among the earliest and most direct evidence of Apple's founding. Future sales will include later items, or items with less direct historical significance. The items hitting the market now are the cream of the crop, the items most collectors would ideally want to own.

This auction represents a moment in which major pieces of recent history are being dispersed to private ownership rather than being institutionalized. Once they're sold, they'll likely be held by collectors who are less inclined to lend them out or make them public. Museums and institutions that would make them accessible to researchers and the public are losing the opportunity to acquire them at what might be the last moment when they're available.

On the other hand, the auction is creating a documented record. When these items sell, they'll be extensively photographed, described, and catalogued. The results will be published. Researchers will be able to access that information. The commercial auction process, while driven by profit motive, actually serves an archival function.

For future historians, the dispersal of Jobs' artifacts will actually provide research opportunities. They'll be able to compare how the items were stored, handled, and preserved over time. They'll be able to see what collectors valued and how preferences changed. They'll be able to trace the provenance and verify authenticity through auction records. The market in these artifacts becomes a kind of public record of how we valued and understood Jobs and Apple's history.

The most likely scenario is that some of these items will eventually find their way into museums and institutions after changing hands among private collectors multiple times. The journey from Jobs' childhood bedroom to private collectors to eventual institutional homes is a narrative arc that makes historical sense. Items that start in intimate family contexts become public through commercial channels, then eventually become part of official historical records and public institutions.

Whatever happens with individual items, the auctions of 2025 will mark a watershed moment. This is the first time the most significant collection of Jobs' personal artifacts is being made available for sale. It's the moment when his childhood bedroom's contents are being photographed, catalogued, and distributed. Future collectors will be competing for items from this collection or for later artifacts that don't have the same direct historical significance.

FAQ

What is the first Apple check and why is it so valuable?

The first Apple check is a

How did John Chovanec come to possess Steve Jobs' personal items?

John Chovanec became Steve Jobs' stepbrother in 1990 when his mother married Paul Jobs, Steve's father. When Paul died, Steve promised Chovanec's mother she could live in the Los Altos Hills house (where the first Apple computers were assembled in the garage) "until you drop." Steve showed little interest in his childhood bedroom's contents, telling Chovanec to simply take the desk and other items. Chovanec worked at Apple for 16 years starting in 2005 but kept his family relationship to Jobs confidential. When Marilyn, Chovanec's mother, died in 2019, the accumulated items that had been stored in Chovanec's garage for years became his to manage. He decided to consign them to RR Auction in 2025 rather than let them gather dust, reasoning that collectors would appreciate and value them during the 50th anniversary of Apple.

Why is Steve Jobs' signature worth more than other famous figures' signatures?

Steve Jobs' signature is exceptionally valuable because he famously refused to sign items, creating artificial scarcity. Unlike celebrities, athletes, or other public figures who signed thousands of items over their lifetimes, Jobs deliberately limited his autographs. A signed Jobs business card can fetch six figures, while signed items from other famous people sell for far less. This scarcity premium reflects market psychology and collector behavior. Jobs' refusal to sign items means that when authenticated signatures do exist, they become investment-grade items. Additionally, Jobs' cultural status as a visionary and icon makes his signature inherently more desirable than that of equally successful but less mythologized business figures.

What is the significance of the April 1, 1976 partnership agreement being sold at Christie's?

The partnership agreement signed on April 1, 1976, by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne established the legal foundation of Apple Computer Company. Christie's estimates it will sell for

What do Steve Jobs' personal items reveal about his personality and interests?

The collection of items from Jobs' childhood bedroom reveals someone deeply influenced by counterculture and Eastern philosophy. His 8-track tape collection included extensive Bob Dylan and Joan Baez albums, suggesting interest in poetic lyricism and artistic rebellion. His handwritten horoscope, generated by an Atari computer, indicates fascination with both technology and spirituality. He kept a copy of "How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive: A Manual of Step-by-Step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot," reflecting a DIY ethos and belief that determined people could understand complex systems. His twelve high school bow ties suggest he developed a distinctive personal aesthetic early. His Reed College notebooks and Atari work documentation show he valued creative documentation. Collectively, these items portray someone interested in design, music, philosophy, and technological innovation long before Apple's founding.

Should historically significant artifacts be sold to private collectors or acquired by museums and institutions?

This question involves trade-offs between preservation, public access, and market dynamics. Museums and institutions provide public access and professional preservation, but they often lack the financial resources to compete with wealthy private collectors at auction. Commercial markets drive prices upward and create robust documentation and authentication processes, but private collectors may restrict public access. The ideal scenario might involve private collection followed by eventual institutional acquisition as prices stabilize and items appreciate. Ironically, the commercial auction process serves an archival function through extensive photography and cataloguing, even though the items then become privately held. For Apple artifacts specifically, the dispersal to private collectors at least ensures these items are preserved and documented, even if public access is limited.

Why do collectors value physical artifacts from the digital age?

Physical artifacts from the Steve Jobs era are paradoxically more durable than the digital work of that period. A 1976 check or 1975 notebook remains readable and accessible without specialized technology. Digital files from the same era are largely inaccessible without specific hardware and software that's increasingly obsolete. This creates an interesting preservation dynamic where physical artifacts become more valuable as primary historical sources precisely because digital materials are harder to preserve long-term. Collectors value these items because they provide direct evidence of how Jobs actually thought and worked, offering richer insight than secondary sources. Additionally, physical possession of artifacts creates a psychological connection to historical figures that abstract information or digital files cannot replicate.

What does the rapid appreciation of Apple memorabilia suggest about markets and valuation?

The rapid price appreciation of Apple artifacts (with earlier checks and documents selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars in recent years) reveals that cultural significance and narrative power drive market value more than utility or material properties. These items have no functional use, yet markets assign them enormous value. This suggests that speculative demand and emotional connection to cultural icons can justify extreme prices independent of practical considerations. The self-reinforcing cycle where prices rise because people expect them to rise indicates these markets have speculative elements similar to fine art or rare collectibles. However, this also creates risk for investors, as declining cultural significance or declining interest in Apple could cause prices to fall. The market in Jobs artifacts reflects broader economic patterns where scarcity, narrative, and cultural meaning drive valuation more than function or material cost.

Conclusion: The Meaning of Objects in the Age of Intangibles

The auction of Steve Jobs' personal artifacts in 2025 marks a singular moment in technological history. It's the point at which the private, material world of a transformative figure is being systematized, valued, and dispersed into public markets. The first check, the partnership agreement, the notebooks, the bow ties, the 8-track tapes—each item tells a story about who Steve Jobs actually was before mythology took over.

What makes this auction particularly significant is that it's happening during a transition point in how we preserve and value history. We're still living in an era when physical artifacts matter enormously, yet we're moving toward a future where everything is digital and dematerialized. Jobs himself spent his career trying to make technology invisible, to eliminate the physical barriers between people and content. Yet the things we're preserving and valuing are stubbornly, determinedly physical.

There's a poignancy in this contradiction. The man who envisioned a future of pure digital interaction is being remembered through his bow ties and notebooks. The visionary who wanted to transcend materialism is having his material possessions auctioned to the highest bidder. The person who rarely signed things is being valued precisely for his refusal to sign things. History has a way of creating these ironies.

From a practical standpoint, these auctions will likely result in the dispersal of Apple's founding artifacts to wealthy private collectors. Some items may eventually find their way into museums and institutions. The market will establish record prices. Investors will view these items as alternative assets with historical appreciation potential. The commercial auction process will create extensive documentation and authentication that serves historical and archival purposes.

But beyond the practical outcomes lies a deeper cultural moment. We're explicitly acknowledging that cultural significance and narrative power can justify prices that far exceed material utility. We're creating a market in history itself, pricing the moments and people and objects that matter to us. We're saying that owning a piece of Steve Jobs' world is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars not for functional reasons but for connection, for meaning, for participation in a mythology that's become central to how we understand technology and innovation.

That mythology is probably earned. Jobs and Wozniak did launch a revolution in personal computing. Apple products did change how people interact with technology. Jobs did influence an entire generation of entrepreneurs and designers. The objects being auctioned are evidence of that transformation. But the mythology also transcends the evidence. It becomes something almost religious, a narrative about vision and innovation that carries weight beyond the facts of the case.

As you consider what these auctions mean, remember that you're witnessing both historical significance and cultural mythology in action. The check is important because it's the first Apple transaction. But it's also valuable because we've decided to value it, because we've constructed a narrative around Steve Jobs and Apple's founding that makes even a mundane piece of paper into a sacred object. That decision—to invest cultural meaning and monetary value in these artifacts—says as much about us as it does about Jobs.

The 50th anniversary of Apple is more than just a number on a calendar. It's a moment for reflection on where technological innovation has taken us, what we've gained and lost, and what we hope to build in the future. These auctions are part of that reflection. They're our way of saying that this history matters, that these people mattered, that the choices they made in their garage in Los Altos Hills had consequences that ripple across our entire world.

Whether you're a collector, an investor, a historian, or simply someone interested in technology and culture, these auctions offer a rare opportunity to own a piece of that history. But they also offer something less tangible: a moment to think about what we value, why we value it, and what stories we're telling about innovation, technology, and the people who shape our world.

Key Takeaways

- The first Apple check signed by Jobs and Wozniak on March 16, 1976 is expected to sell for approximately $500,000, making it worth 3.7 times more than the second Apple check sold in 2023

- Steve Jobs' signature is among the most valuable autographs of any public figure because he famously refused to sign items, creating artificial scarcity that drives prices to six figures for simple business cards

- John Chovanec, Jobs' stepbrother who worked at Apple for 16 years, possesses items from Jobs' childhood bedroom including notebooks, 8-track tapes, bow ties, and the desk where Jobs worked before founding Apple

- The April 1, 1976 partnership agreement between Jobs, Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne is expected to sell for $2-4 million at Christie's, making it potentially more valuable than the first check due to its historical significance as the founding legal document

- These auctions reveal fundamental truths about cultural value, scarcity, and how we assign meaning to objects—demonstrating that narrative power and emotional connection drive market valuations beyond practical utility

![Steve Jobs' Personal Apple Artifacts at Auction: The Complete Guide [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/steve-jobs-personal-apple-artifacts-at-auction-the-complete-/image-1-1767711138306.jpg)