Substack's TV App Launch: Why Creators Are Pushing Back [2025]

Substack dropped a bombshell in early 2025: a TV app for Apple TV and Google TV. The move seemed logical from a business perspective. Video consumption on televisions is skyrocketing. YouTube viewers alone watched 700 million hours of podcasts on their TVs in October 2025 alone. Streaming platforms are racing to own the living room experience.

But the reaction from Substack's creator community was swift and brutal.

Within hours of the announcement, the company's blog post was flooded with comments from writers expressing frustration, disappointment, and something deeper: betrayal. "Why are you doing this Substack? Why are you veering away from the written word?" one creator wrote. Another plea: "Please don't do this. This is not YouTube. Elevate the written word."

This backlash reveals something important about what happens when a platform pivots away from the promise that built it in the first place. Substack launched on a specific value proposition: a place for writers, by writers. A refuge from algorithm-driven social media and the chaos of content mills. Now, with video recommendations and discovery feeds, critics worry it's becoming just another streaming service chasing the same audiences as everyone else.

Here's what's really going on beneath the surface of this controversy, and what it means for creators, platforms, and the future of independent media.

The TV App: What Substack Actually Built

Let's start with what Substack actually announced. The TV app isn't a complete overhaul. It's an additional layer on top of what the platform already offers.

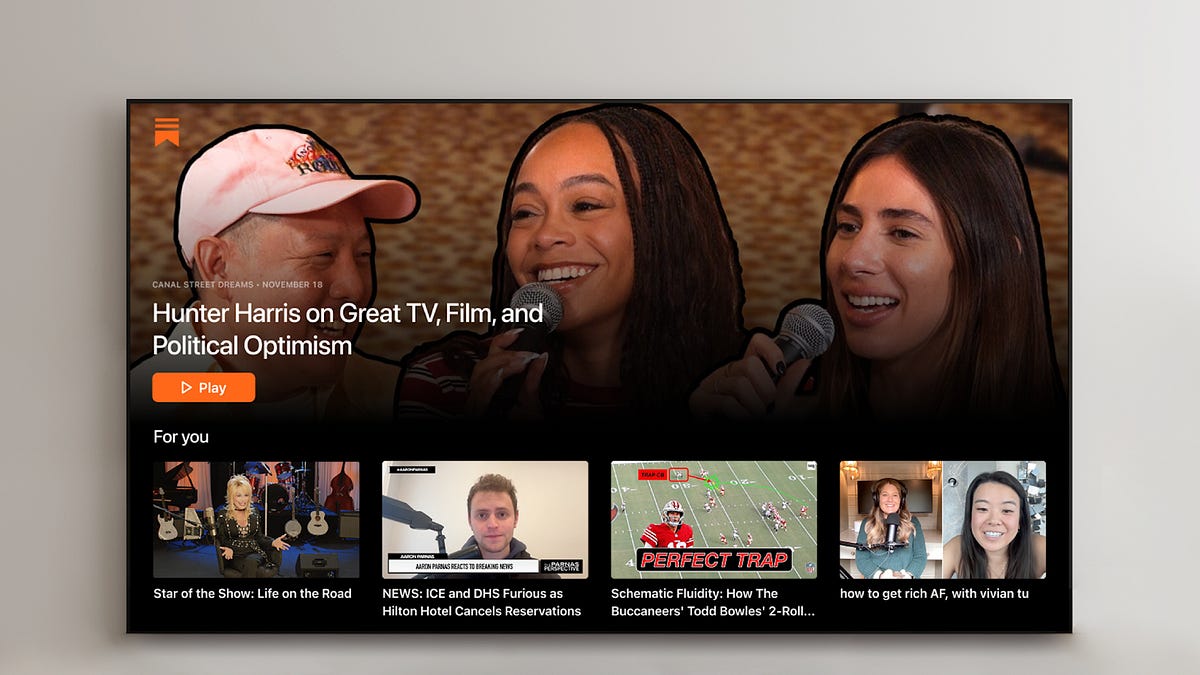

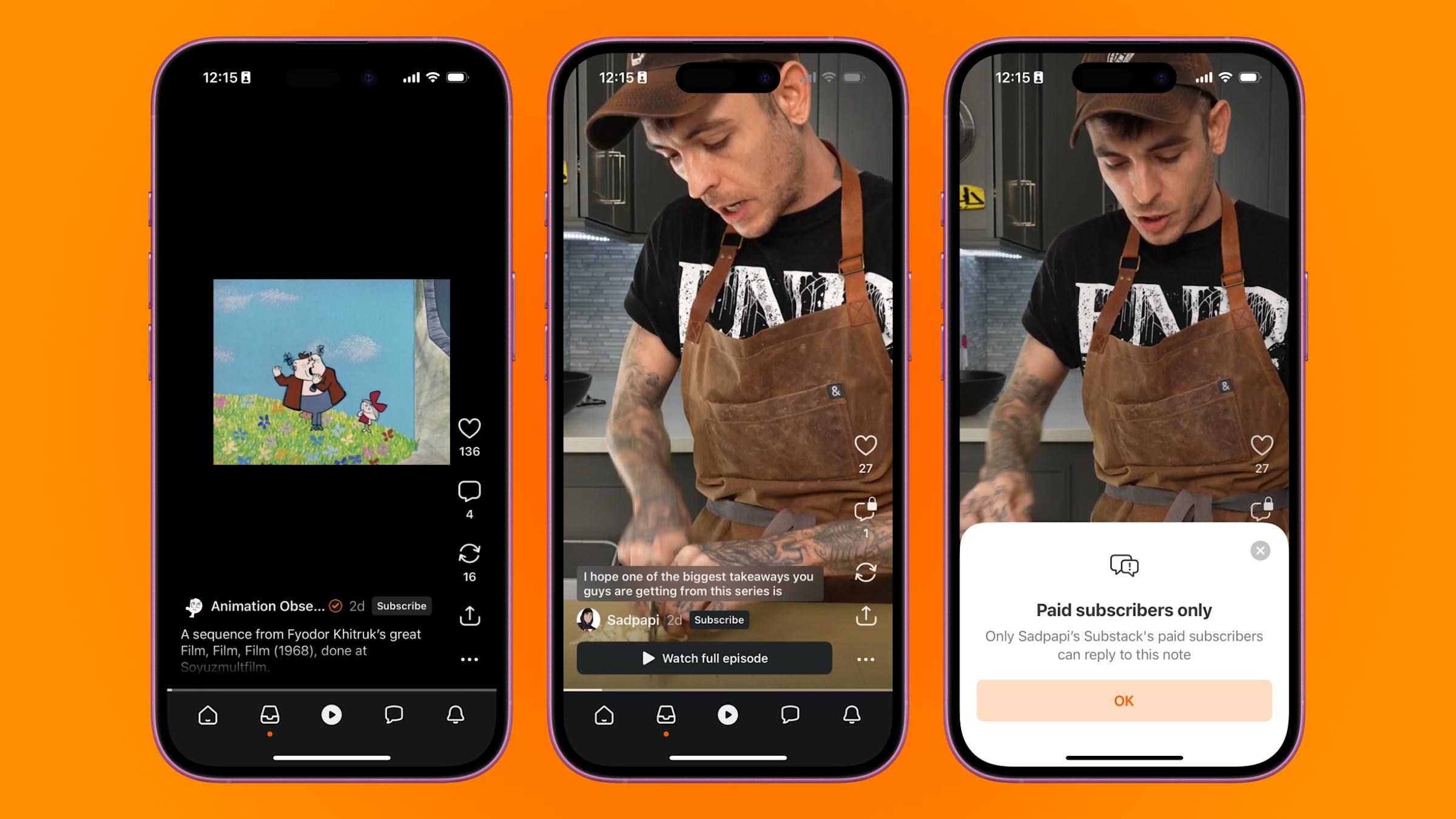

Creators who produce videos or livestreams now have a native way to distribute that content directly to televisions. Subscribers can access their followed creators' video content through a dedicated app. The interface includes a "For You" feed powered by recommendations, similar to what you'd find on YouTube or TikTok. Free and paid subscribers both get access. Substack says audio content is coming next, along with more sophisticated discovery features.

From a product perspective, this makes sense. Video podcasts are massive. Spotify redesigned its TV app around the same time, adding video podcasts and music videos to compete. Apple TV is becoming less about traditional television and more about a hub for streaming content of all types. If Substack wants creators to reach audiences wherever they consume content, the TV is an obvious target.

But here's the tension: Substack's brand isn't built on video. It's built on something much more specific: the written word, delivered directly to inboxes.

The platform grew because it offered an alternative to algorithm-driven feeds and ad-supported content. You follow a writer. Their newsletter lands in your inbox. No mysterious ranking factors. No algorithmic suppression. No recommendation engine deciding whether you see it. Just direct communication between creator and audience.

A TV app with a "For You" feed introduces all the things Substack positioned itself against.

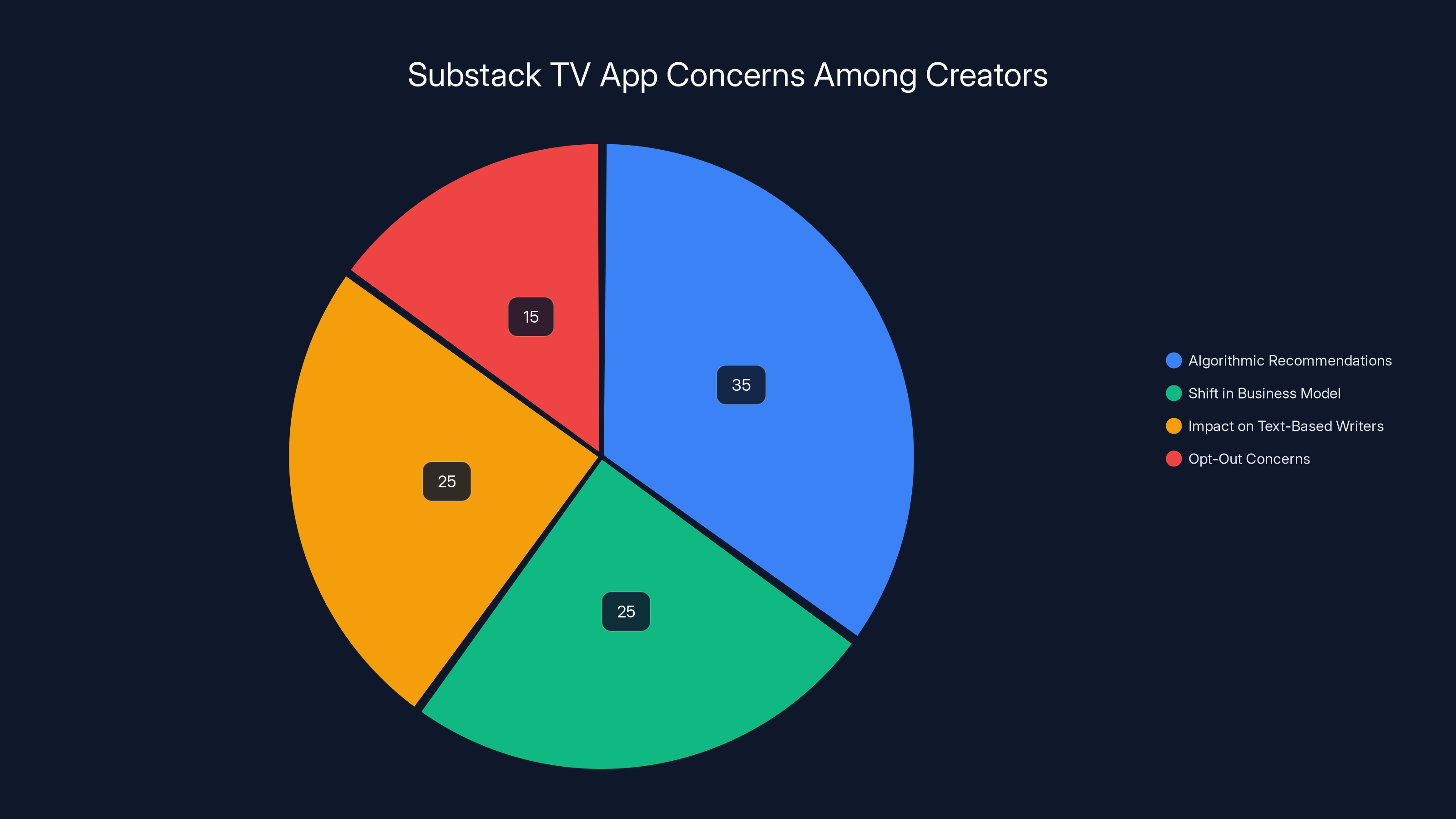

Estimated data suggests that algorithmic recommendations are the primary concern for creators, followed by shifts in the business model and impact on text-based writers.

Why the Creator Backlash Actually Matters

The immediate reaction might seem like typical internet contrarianism. Of course people complain about every product change. But the specific complaints from Substack creators point to something real: a fundamental misalignment between what the platform promised and what it's becoming.

Substack's founding pitch was razor-focused. If you were a writer, Substack offered you a way to build a direct relationship with readers. You controlled the relationship. You set the price. You kept 90% of subscription revenue. No middleman. No algorithm deciding your fate. This resonated with writers who felt squeezed by Medium's pivots, by Patreon's changes, by Twitter's chaos.

The backlash isn't really about video existing on Substack. It's about the introduction of a recommendation engine that treats writers' work as raw material for a discovery feed.

Here's the practical concern from writers' perspective: A reader can now discover a writer they don't follow through Substack's "For You" algorithm. That's good for discoverability. But it means Substack is now ranking and promoting some creators over others. It means the platform is making editorial decisions about what's worth surfacing. For a platform that positioned itself as the antithesis of this exact dynamic, it's a meaningful shift.

One creator articulated this fear well in comments: "This changes the entire value proposition. I came to Substack because they promised not to be YouTube. Now they're becoming YouTube, just with slightly better economics."

Is that fear overblown? Maybe. Substack is still fundamentally different from YouTube. Creators still own their subscriber relationships. The TV app is still optional. But the fear isn't irrational. It's based on watching what happened to other "creator-friendly" platforms that made similar pivots.

The Economics of the TV Bet

From Substack's business perspective, the TV app is a necessary move. Here's why.

Substack's revenue model depends on subscription revenue, which means it needs to keep growing the total number of active subscriptions on the platform. This is getting harder. The easy growth of 2020-2022 is over. Most writers who wanted to move to Substack already have. Discovery of new creators is becoming the limiting factor. Without better ways to surface new writers, subscriber growth flattens.

A TV app addresses this directly. Television viewing is a massive category. YouTube users watched 700 million hours of podcasts on TVs in just one month. That's an enormous audience Substack currently can't reach because it has no TV presence. Adding a TV app with discovery features is a way to tap that market.

But there's a catch. To compete on television, Substack has to think like a television service. That means recommendations. That means algorithm-driven discovery. That means some creators get promoted and others don't. This is the opposite of the platform's original appeal.

The economic reality is brutal: Substack probably can't grow subscription revenue significantly without changing how it works. But every change moves it further from what made it appealing to writers in the first place.

This is the classic "growth trap" that has destroyed dozens of platforms. Early growth comes from being different and filling a specific need. Sustained growth requires becoming more like the competitors. By the time you realize the shift, you've alienated your original audience.

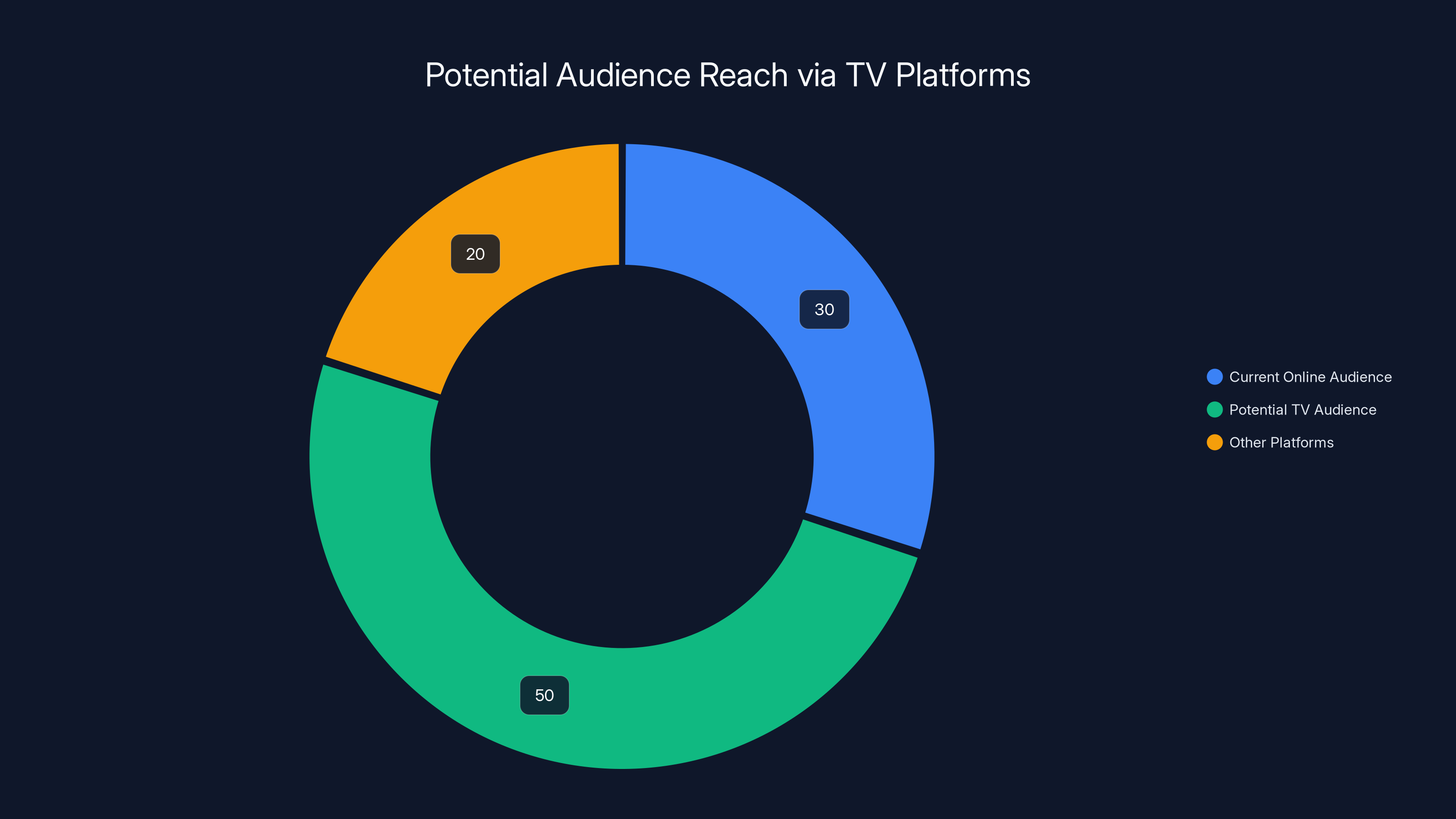

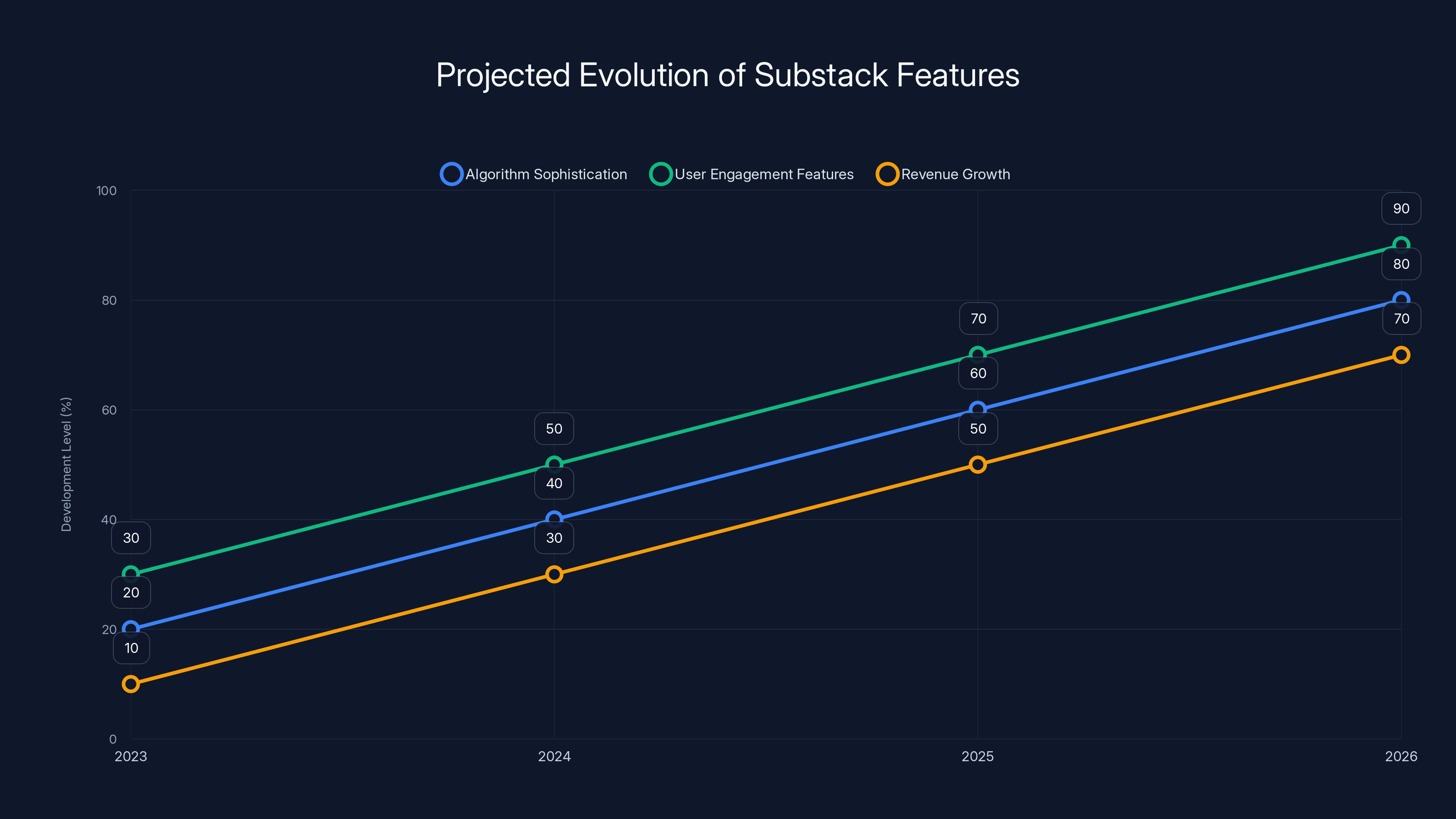

Estimated data suggests that a TV app could significantly expand Substack's audience reach, tapping into a large potential TV audience.

What's Really Driving Platform Pivots

Substack isn't unique in making a pivot its core users hate. This is a pattern that repeats constantly across platforms.

Twitter shifted toward algorithmic feeds. Medium went from writer-friendly platform to entertainment destination. YouTube started with simple video hosting and became a recommendation engine. Patreon added things that benefited the platform at the expense of creator relationships. In each case, the pivot made business sense. In each case, creators felt betrayed.

Why does this keep happening? Because sustainable growth and core user happiness are often in tension.

Here's the math: If you're a platform with 1 million active creators and you want to grow to 10 million, you need to reach people who aren't currently your audience. Your current audience is already using the platform. Additional growth has to come from somewhere else. That somewhere else is always less aligned with your original value proposition.

Facebook started as a college social network. Its growth required becoming a platform for everyone, which made it worse for its original users. Slack started as a team communication tool. Its growth required becoming a platform for building tools on top of it, which complicated the core product. Every platform that scales experiences this tension.

Substack is at the same inflection point. It can try to keep growing by making the written word more discoverable. Or it can stay true to its original value proposition and accept slower growth. There's no path that keeps everyone happy.

Substack chose growth. The TV app is step one.

The Video Creator Question

There's another angle here worth examining: the rise of video creators on Substack.

Substack didn't set out to be a video platform. But over the past few years, creators increasingly used Substack to host video content. Some podcast creators started uploading video feeds. Some writers added video supplementary content. The platform's infrastructure wasn't designed for this, but creators found a way to make it work.

Substack noticed this trend and built the TV app partly in response to it. If creators are already making video content, Substack figured, we should build distribution channels for that content.

This creates a subgroup of Substack creators who probably love the TV app: those who produce video or podcast content. For them, reaching TV audiences is genuinely valuable. The opportunity was there. Substack gave them access to it. That's a win.

But that's also the problem. The interests of video creators and text-based writers diverge sharply. Video creators benefit from recommendation algorithms and discovery features. Text-based writers see these as threats. By trying to serve both groups, Substack is making both groups unhappy.

This is another pattern that repeats: platforms that try to be everything for everyone end up being nothing special for anyone. Twitter tried to serve journalists, activists, celebrities, and casual users. It became increasingly hostile to all of them. Medium tried to serve individual writers and publications. It confused both groups. Substack is trying to serve text writers and video creators. Neither group is satisfied.

How Recommendation Algorithms Change Creator Incentives

Let's dig into something more technical: how recommendation algorithms change how creators think about their work.

Before the TV app, if you were a text-based writer on Substack, your incentive structure was simple: write good stuff, and readers will subscribe. Better writing leads to more readers. That's it. No optimization for algorithmic visibility. No need to think about thumbnail design. No pressure to make content "viral."

With a recommendation algorithm in the mix, incentives shift. Now there's a question mark: what does Substack's algorithm reward? Is it engagement? Watch time? Click-through rates? Different metrics lead to different content.

The fear from writers is real. Once algorithms exist, they can't be ignored. Even if a writer doesn't explicitly optimize for algorithmic visibility, the fact that the algorithm exists changes their behavior. They might start thinking about whether their headlines are "clickable" enough. They might reconsider video formats because they drive more engagement. They might adjust posting times to match algorithmic preferences.

This is death by a thousand cuts. No single change is catastrophic. But each small adjustment pulls the platform further from what made it special.

There's also a question about fairness. Substack's original appeal was that it didn't play favorites. Every creator's content reached their subscribers equally. Now Substack is ranking creators, effectively saying some are worth more algorithmic promotion than others. That's a fundamental change to how the platform works.

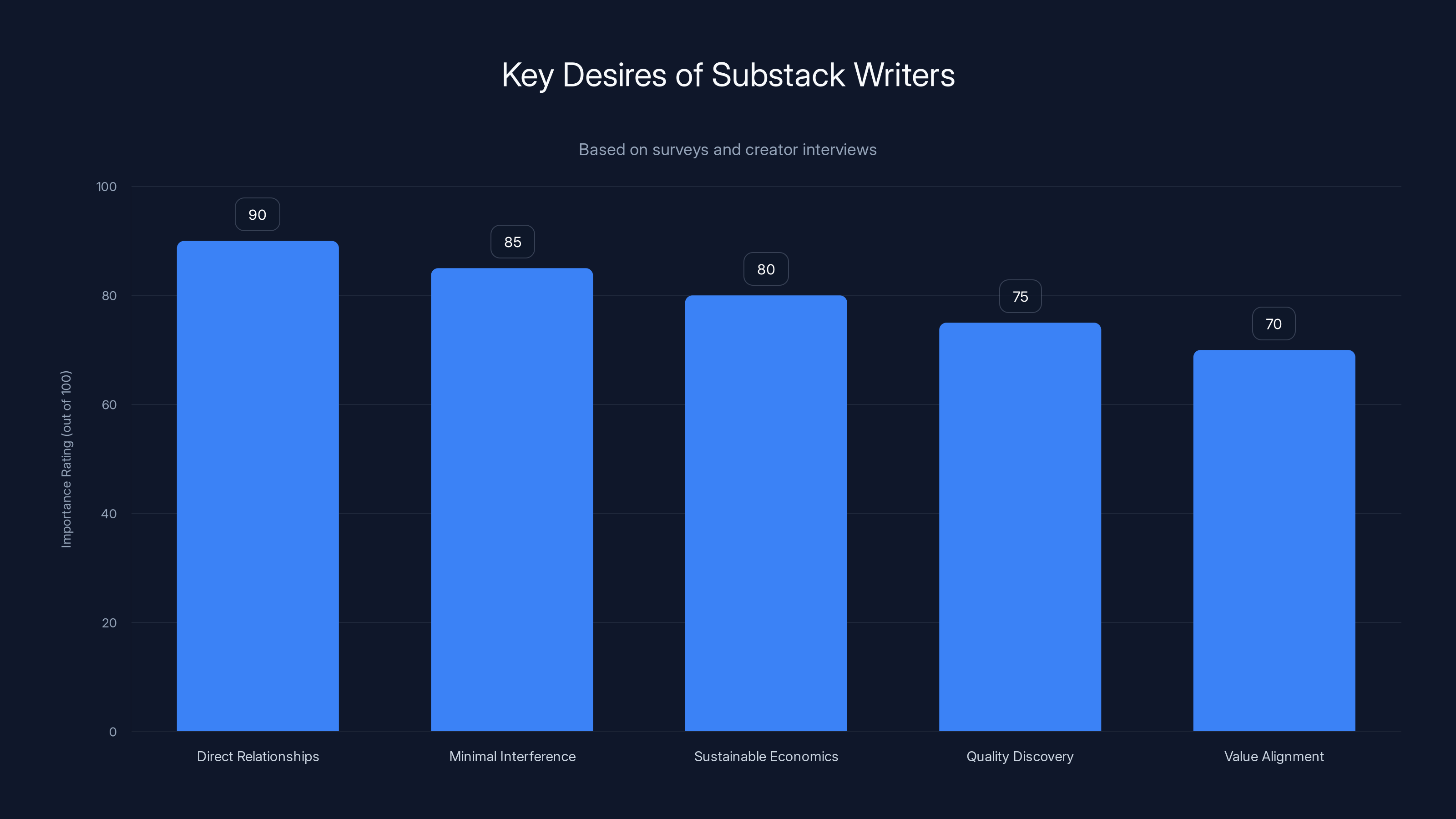

Estimated data shows that direct subscriber relationships and minimal platform interference are top priorities for Substack writers.

The Comparison to YouTube

Creators comparing Substack to YouTube isn't accidental. They're tracking a specific concern: platform trajectory.

YouTube started as a video hosting service. You uploaded a video, people could watch it, and that was that. Over time, YouTube added recommendations. Then algorithmic recommendations. Then algorithmic ranking. Then suggested videos. Then autoplay. Then the algorithm became the core feature of YouTube, not an afterthought.

The shift happened gradually. Each change made sense individually. Each change was theoretically optional. But together, they transformed YouTube from a distribution platform into a recommendation engine that just happens to host videos.

Writers worry Substack is following the same trajectory. Start with optional recommendations on TV. Then add recommendations on web. Then optimize recommendations based on engagement metrics. Then suddenly Substack isn't a place where writers have direct subscriber relationships. It's a place where Substack decides what readers see.

Is this paranoia? Maybe partially. But it's also pattern recognition based on what's actually happened to similar platforms. Writers have watched this movie before.

What Happens to Direct Relationships?

One thing that hasn't been addressed clearly in Substack's announcement: what happens to the foundational relationship between writer and subscriber?

On Substack today, if you're a paid subscriber to a newsletter, you get access to all their content. The writer controls what their subscribers see. This is the core of the value proposition: the writer-subscriber relationship is direct and unmediated.

With the TV app, this changes slightly. A reader might discover a creator through the "For You" feed without being a paid subscriber. They might watch a free preview of video content. They might subscribe based on algorithmic recommendations, not because they sought out the writer intentionally.

This is objectively more accessible. New readers are easier to acquire. But it also changes the nature of the subscriber base. Instead of a group of people who actively chose to follow a writer, subscribers become a group of people who were algorithmically presented with a creator and happened to like it.

For some writers, this is genuinely better. It means faster growth and larger audiences. For others, it's fundamentally at odds with why they chose Substack in the first place.

One creator in the comments put it this way: "I like that my subscribers chose me intentionally. That relationship is more honest. If I'm competing with Substack's algorithm for attention, that's a different game entirely."

The Timing Question

Another thing worth considering: why now?

Substack has been growing for years. A TV app didn't suddenly become possible in January 2025. So why launch it now?

Part of the answer is technical. Building a quality TV app takes time. Substack's engineering team probably started working on this a year or more ago. Launch timing is always somewhat arbitrary.

But part of the answer is business. Substack has stated it's working toward profitability. Video content is a growth lever that directly competes with much larger platforms like YouTube and TikTok. If Substack is going to diversify its creator base and revenue streams, video is table stakes.

There's also pressure from investor expectations. Substack has taken significant venture funding. That funding comes with implicit expectations about growth trajectories and path to profitability. Sitting still and hoping text-based newsletter growth accelerates isn't a venture-backed business narrative. Pivoting into new categories and capturing new audiences is.

So the TV app isn't just about serving creators better. It's about Substack executing its business strategy and managing investor expectations.

Estimated data shows Substack's features and revenue are expected to grow significantly by 2026, aligning with trends seen in other platforms.

How Other Platforms Handled Similar Pivots

Looking at comparable platforms offers some useful lessons.

Patreon faced a similar moment when it realized creators were using the platform for non-monetary purposes: community building, audience engagement, content distribution. Patreon could have stayed focused solely on monetization. Instead, it expanded to serve broader creator needs. This annoyed some of the original core user base who liked the platform's singular focus. But it enabled growth.

Medium faced this decision and made different choices. Medium started as a writer-centric platform. As it struggled to find sustainable economics, it pivoted toward being a content discovery platform, then a paywall service, then a publication network. Each pivot moved it further from its original mission. Writers felt increasingly alienated. Medium struggled.

LinkedIn faced criticism for becoming algorithm-driven and optimizing for engagement instead of genuine connection. But it grew significantly by doing so. The original community hated the changes. The new community likes the platform.

So there are models where platform pivots work from a business perspective. But they almost always create a gap between original users and new users. The original users feel like the platform isn't for them anymore. The new users never knew the original version and like what the platform has become.

Substack is probably headed toward a similar bifurcation: original newsletter writers who feel the platform betrayed them, and new video creators and casual viewers who are perfectly happy with Substack as an entertainment discovery platform.

The Real Cost of Growth

Here's what doesn't get discussed enough about platform pivots: the real cost of pursuing growth through feature expansion.

Every feature you add to a platform makes it more complex. More complexity means higher engineering costs. It also means the platform becomes less coherent. Instead of having a clear identity, it becomes a collection of features. This makes it harder for users to understand what the platform is for.

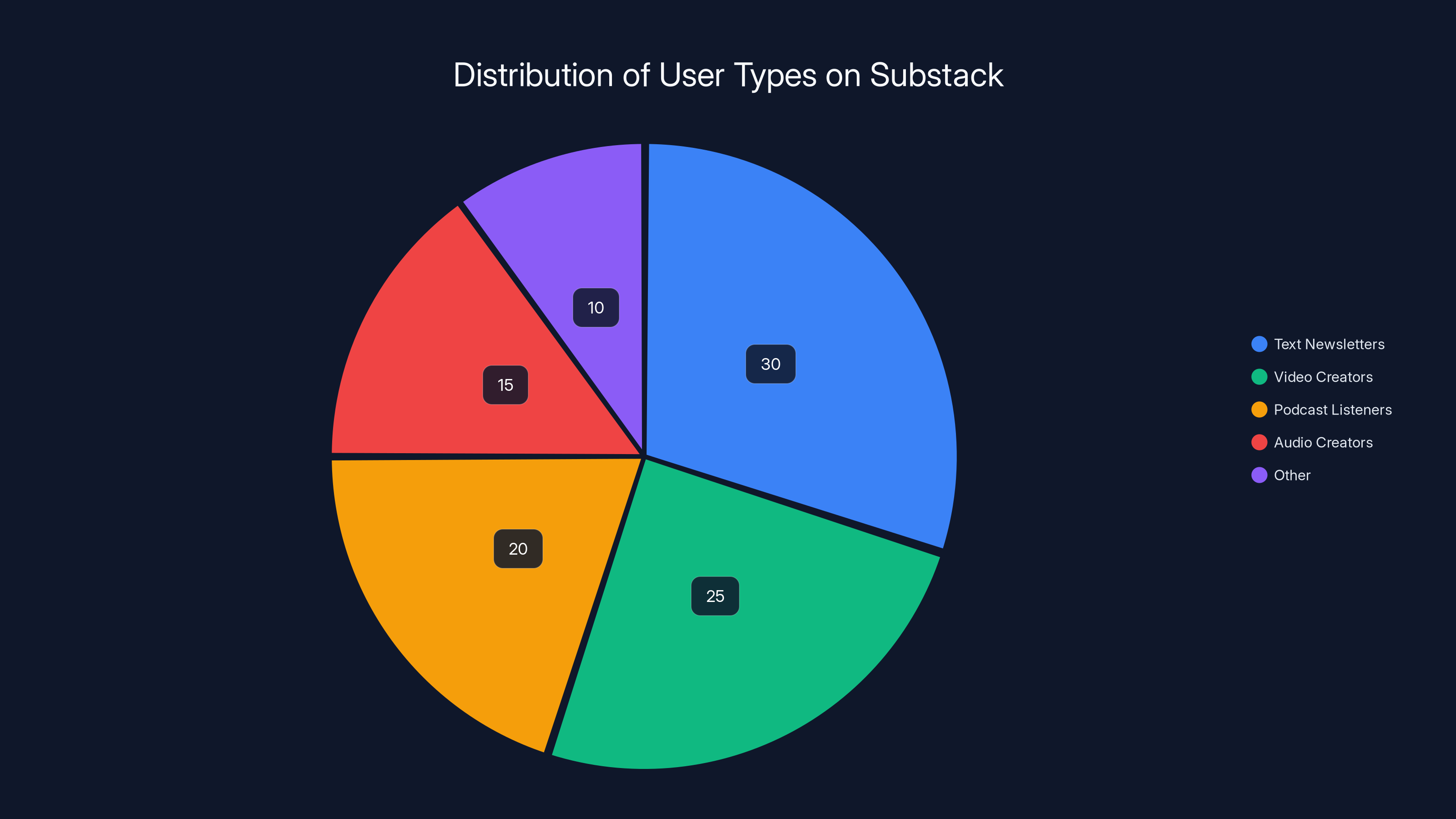

Substack is now a platform for text newsletters, video creators, podcast listeners, and possibly audio creators (coming soon). That's five different user types with potentially conflicting needs. The more you add, the harder it is to serve any individual group really well.

There's also a real cost to existing creators' attention. If Substack is now promoting videos in discovery feeds, text-based writers feel less central to the platform. This isn't paranoia. It's real. Substack has finite real estate and attention. Every placement given to a video creator is placement not given to a text writer.

In economics, this is called the "zero-sum game" problem. If the platform's resources are limited (and they are), serving new constituencies means taking away from existing ones.

What Writers Actually Want

Let's zoom out and consider what Substack's core user base actually wants.

Substack surveys and creator interviews consistently point to a few core desires:

-

Direct subscriber relationships: Creators want to own their audience, not compete with algorithms for attention.

-

Minimal platform interference: Writers want the platform to get out of the way and let them do their thing.

-

Sustainable economics: Creators want to be able to make a living from their writing.

-

Discovery that doesn't compromise quality: Writers want new readers, but not at the expense of turning their work into content to be consumed alongside cat videos.

-

Alignment with their values: Writers chose Substack partly because of what it stood for. They want the platform to stay true to that.

The TV app addresses one of these desires (discovery) and potentially undermines the others. For a platform trying to keep its original community happy while growing, that's a tough trade-off.

What writers probably would have preferred: better discovery features that don't involve algorithmic recommendations. Better discovery that still respects the original value proposition. Things like improved search, better categorization, featured collections of quality writers, editorial picks from trusted curators.

Substack could have done discovery without turning the platform into a recommendation engine. The fact that they chose the recommendation-engine approach suggests growth and scale are more important than maintaining the original value proposition.

As Substack expands its features, the platform serves a diverse range of user types, potentially diluting focus on any single group. Estimated data.

The Future of Niche Platforms

This situation raises a broader question: can niche platforms stay niche while growing?

The answer seems to be mostly no. There's a reason for this. Niche platforms appeal to users precisely because they're not trying to be everything. But growth requires expansion. The more you expand, the less "niche" you become.

At some point, every successful niche platform faces a choice: stay small and true to your values, or grow and dilute your values. There's no option to grow and maintain the niche indefinitely. That's not how platforms work.

Substack chose growth. This is rational from a business perspective. It's also predictable that the original community would be unhappy about it.

The interesting question is what happens next. Do writers migrate to a new platform that focuses purely on text? Do they stay on Substack but feel increasingly alienated? Do they eventually adjust to the new Substack and accept the algorithmic feed as the new normal?

History suggests the answer is: all three happen simultaneously, and the original community eventually becomes a small percentage of the platform's user base.

How This Affects Reader Experience

Let's also consider how this affects readers, not just writers.

For casual readers, the TV app is probably fine. It provides access to video content on a screen they actually use. The "For You" recommendations will surface content they might enjoy. This is broadly positive.

For readers who came to Substack specifically because it didn't have algorithmic recommendations, the change is negative. They came to Substack to escape algorithmic feeds. Now Substack is building one.

There's also a quality question. Algorithmic recommendations optimize for engagement metrics, which often means sensational, controversial, or highly produced content. Editorial curation optimizes for quality and value. The incentives are different.

Readers who loved Substack because they found thoughtful, nuanced long-form writing might find the algorithmically recommended feed surfaces different content: more entertaining, more immediately engaging, but less substantive.

This isn't universal. Some readers will prefer the new Substack. But for readers who chose Substack precisely because it offered an alternative to algorithmic feeds, the change is meaningful.

Comparing to Substack's Original Vision

It's worth looking back at what Substack actually said when it launched.

Substack's original pitch was about empowering writers. The platform promised to take the friction out of publishing and monetization. But it also positioned itself as an alternative to algorithm-driven social media and recommendation engines.

Early Substack marketing material highlighted the direct relationship between writer and reader. The absence of algorithms was presented as a feature, not a limitation.

The TV app represents a departure from this positioning. It's not necessarily a betrayal, but it is a meaningful shift. Substack is saying: we still believe in writer empowerment, but we also believe in algorithmic recommendations and content discovery.

Maybe that's fine. Maybe the original vision was too narrow. Maybe Substack has learned that writers want both direct relationships and algorithmic discoverability.

But the fact that this shift wasn't framed as a philosophical change to the platform's mission suggests Substack might not have fully thought through the implications. Or, more cynically, it decided that managing the backlash was worth the growth benefits.

What Happens to Independent Publishers

There's also a question about what this means for the broader landscape of independent publishing.

Substack was supposed to prove that the internet could support sustainable independent media. Writers could build audiences and make money directly from subscribers without relying on advertising, publishers, or algorithms.

As Substack pivots toward algorithmic recommendations, it's implicitly saying that sustainable independent media requires some amount of algorithmic help. Pure subscriber relationships aren't enough. You need the platform to do some heavy lifting to surface content.

This might be true. It might also suggest that the original vision of sustainable independent publishing without platform dependency was overly optimistic.

If Substack can't grow significantly without algorithmic recommendations, what does that mean for writers who wanted to escape algorithms? It suggests there's no escape. The algorithm is inescapable. Even on "writer-friendly" platforms, algorithms eventually become the dominant factor.

That's a depressing conclusion. But it might be the accurate one.

The Role of Community Feedback

Substack's public response to the backlash will matter enormously for how this plays out.

If Substack listens to creators and makes adjustments, it might retain more of the original community's goodwill. For example, if Substack made the recommendation algorithm opt-in for creators, or promised that text-based writers would never be ranked against video creators, that would address some concerns.

If Substack doubles down and says essentially "trust us, this will work for everyone," it risks permanently alienating a segment of its original community.

Feedback mechanisms matter. If creators feel heard, they're more likely to give the platform the benefit of the doubt. If they feel dismissed, they're more likely to start looking at alternatives.

This is where Substack's handling of the response becomes as important as the actual feature. How the company communicates about the shift will determine how the community reacts over time.

Lessons for Other Platforms

The Substack situation offers lessons for other creator platforms.

First: be clear about what you're optimizing for. If you claim to value writer empowerment and direct relationships, every feature should reinforce that. If you're going to introduce algorithmic recommendations, acknowledge that you're making a philosophical shift.

Second: involve your community in major pivots. Substack probably would have faced less backlash if creators had been consulted or at least given warning about the direction.

Third: offer choices. Not all creators want algorithmic discoverability. Not all readers want recommendations. Building these features as opt-in rather than opt-out gives users agency.

Fourth: acknowledge trade-offs. There's no way to introduce algorithmic recommendations without changing the platform's character. Be honest about that.

Fifth: maintain coherence. Try to make sure new features align with the platform's core identity. Or be prepared to accept that you're becoming a different platform.

Where Substack Goes From Here

So what happens next?

In the short term, the TV app will launch and find an audience. Video creators will appreciate the distribution channel. Some readers will enjoy discovering new creators. The backlash will fade from immediate headlines.

In the medium term, Substack will probably add more features to improve algorithmic recommendation: better categorization, user preference signals, engagement metrics. The system will become more sophisticated.

Over time, the platform will gradually become less like the alternative to YouTube and more like YouTube-lite. It'll keep the direct subscriber relationships and 90% revenue share, but it'll have recommendation algorithms and discovery feeds and all the other features that come with them.

Original users will either adapt or leave. New users will come in who prefer the new Substack. The platform will grow and become more profitable. It will also become more like every other platform.

This isn't a prediction based on random speculation. It's pattern recognition based on what's happened to every successful platform that started with a niche focus and tried to scale.

The question is whether Substack can execute this transition better than other platforms. Whether it can maintain some of the qualities that made it special while adding the features necessary for growth. Or whether it'll just become another recommendation engine serving up content to maximize engagement.

Based on the TV app announcement and the lack of clear thinking about community concerns, I'd say the latter is more likely. But we'll find out.

FAQ

What exactly is Substack's new TV app?

Substack launched native apps for Apple TV and Google TV that let viewers watch video content and livestreams from creators they follow, as well as a "For You" recommendation feed that surfaces content from other creators. The app is available to both free and paid subscribers, with audio content planned for the future.

Why are creators upset about the TV app?

Creators, particularly text-based writers, are concerned that the TV app's recommendation algorithm contradicts Substack's original promise of being a writer-focused platform free from algorithmic ranking. They worry it signals a shift toward becoming like YouTube rather than maintaining its emphasis on direct creator-subscriber relationships without algorithmic interference.

How does the TV app change Substack's business model?

The TV app doesn't fundamentally change Substack's revenue model of keeping 90% of subscription fees. However, it does shift the platform's strategy toward growth through content discovery and algorithmic recommendations rather than relying primarily on direct subscriber relationships and word-of-mouth discovery.

Will the TV app lead to fewer readers for text-based writers?

Potentially, yes. The introduction of algorithmic recommendations means Substack's attention and promotion will be distributed across more content types and creators. Text-based writers might see less prominent placement if video content drives higher engagement metrics that feed the algorithm.

Can creators opt out of algorithmic recommendations?

Substack hasn't clearly stated whether participation in algorithmic discoverability will be optional or mandatory. This remains one of the key concerns, as creators want control over how their work is presented on the platform.

Is Substack becoming YouTube?

Not entirely, but the trajectory raises concerns. The platform will likely maintain features that differ from YouTube, like direct subscriber relationships and creator revenue splits. However, the addition of algorithmic recommendations suggests a philosophical shift toward being a content discovery platform rather than a pure alternative to algorithmic social media.

What alternatives do writers have if they're unhappy with Substack?

Writers concerned about Substack's direction might consider platforms like Patreon, which focuses more explicitly on creator support, or niche platforms that haven't yet pivoted toward algorithmic recommendations. Some writers are also exploring completely independent approaches with self-hosted newsletters.

How does this compare to what happened to other platforms?

Substack's pivot mirrors historical patterns: platforms like Medium, Patreon, and YouTube all started with specific value propositions and gradually expanded toward algorithmic recommendations and content discovery as they pursued growth. This shift consistently creates a gap between original users who feel alienated and new users who prefer the expanded feature set.

Will Substack address community concerns?

That depends on how leadership prioritizes feedback. If Substack makes adjustments like opt-in algorithmic discoverability or clearer commitments to text-based content, it could retain more community goodwill. If it treats the backlash as inevitable and proceeds unchanged, it risks permanently alienating early adopters.

What does this mean for independent media's future?

The Substack TV app suggests that sustainable independent media might require some degree of algorithmic help for discoverability, contradicting the original vision of pure direct-relationship subscriptions. This raises questions about whether writers can truly escape algorithmic influence even on platforms designed to minimize it.

Key Takeaways

- Substack launched a TV app with algorithmic recommendations, contradicting its original promise as a writer-focused platform without algorithm-driven feeds.

- Creator backlash reveals fundamental tension between growth (requiring algorithmic discovery) and the platform's core value proposition (direct creator-subscriber relationships).

- With YouTube podcasts reaching 700 million TV viewing hours monthly, Substack's pivot addresses a real market opportunity but alienates original users.

- Introduction of recommendation algorithms changes creator incentives and shifts platform identity from content distribution to content discovery platform.

- This pattern repeats across successful platforms: Medium, Patreon, and YouTube all pivoted toward algorithmic recommendations as they scaled, ultimately alienating original communities.

Related Articles

- Substack's TV App Launch: Why Creators Are Torn [2025]

- The 4 Forces Shaping Social Media in 2026 [2025]

- AI Slop Crisis: Why 800+ Creatives Are Demanding Change [2025]

- X Starter Packs vs Bluesky: How Social Media is Copying Features [2025]

- Meta's Global Threads Ads Expansion: What Advertisers Need to Know [2025]

- Meta Expands Ads to All Threads Users Globally [2025]

![Substack's TV App Launch: Why Creators Are Pushing Back [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/substack-s-tv-app-launch-why-creators-are-pushing-back-2025/image-1-1769114274856.png)