How Venture Capital Discovered Biodiversity as a Trillion-Dollar Problem

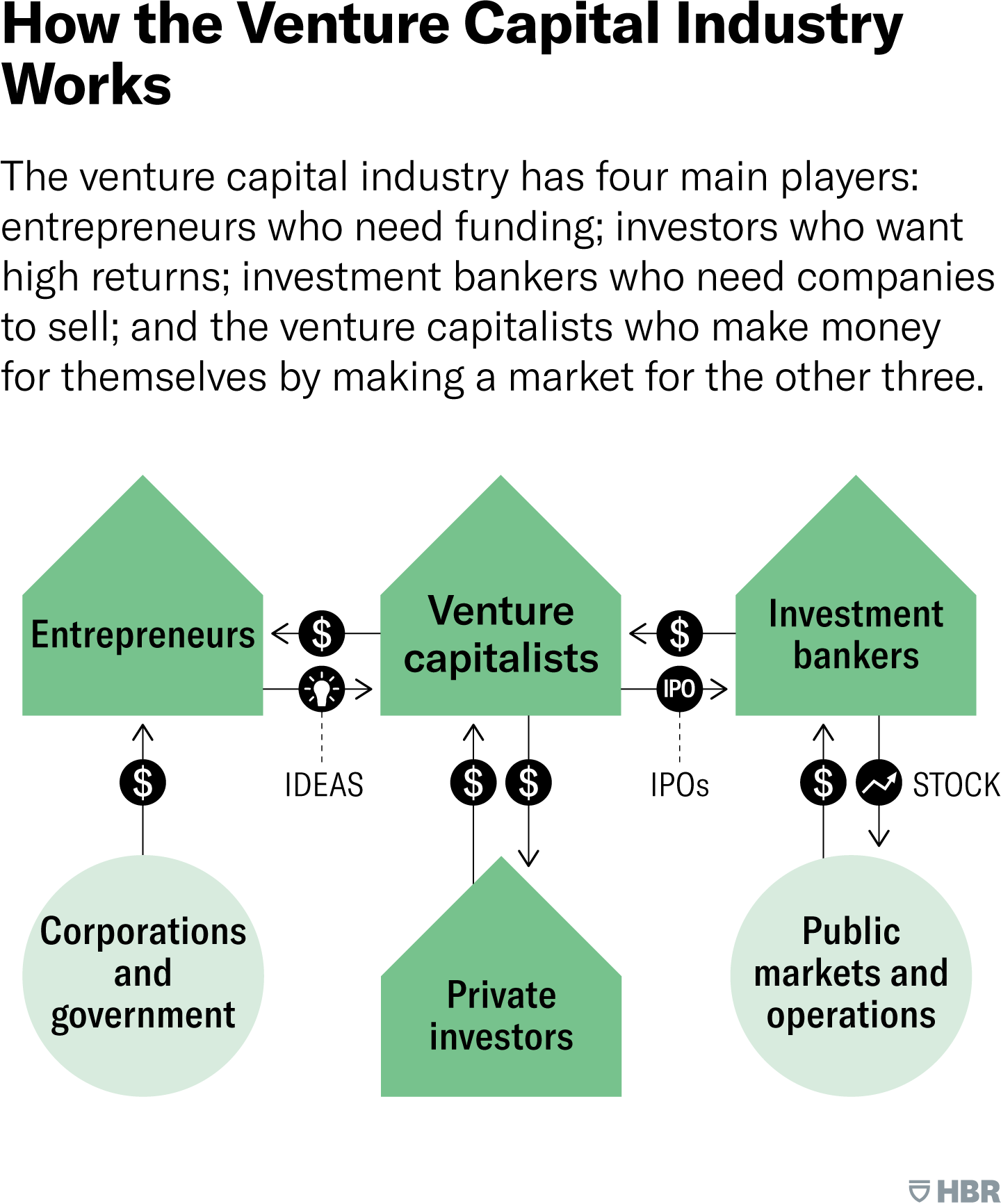

When most people think about venture capital, they picture founders pitching the next SaaS platform or AI model to partners in sand-colored Silicon Valley offices. Biodiversity doesn't usually make the cut. It's not glamorous. It doesn't promise 10x returns in five years. And frankly, it's hard to explain why your fund focuses on protecting birds instead of disrupting fintech.

But that's exactly what makes Superorganism different.

In January 2026, the firm announced it had closed its first fund with $25.9 million in commitments. Not from typical venture sources you'd expect, either. The funding came from Cisco Foundation, AMB Holdings, Builders Vision, and notably, Jeff Jordan, a partner at Andreessen Horowitz.

That's significant because it signals something shifting in how venture capital thinks about returns, impact, and the future of the planet. Biodiversity isn't a side charity project anymore. For some investors, it's becoming a core thesis.

Superorganism launched in 2023 with an audacious claim: it's the first venture capital firm focused exclusively on biodiversity. Not climate tech. Not environmental impact. But specifically on reversing extinction, protecting ecosystems, and building the tools to do it at scale.

Here's the thing. Biodiversity loss is happening faster than most people realize. We're losing species at rates not seen since dinosaurs disappeared. Habitats are shrinking. Insect populations have collapsed by 75% in some regions over the last 50 years. And unlike climate change, which commands billions in venture funding and thousands of startups, biodiversity gets treated like an afterthought.

Superorganism's bet is simple but radical: if you can build venture-scale businesses around protecting nature, you can both save species and make money. Not as a tradeoff. As the same outcome.

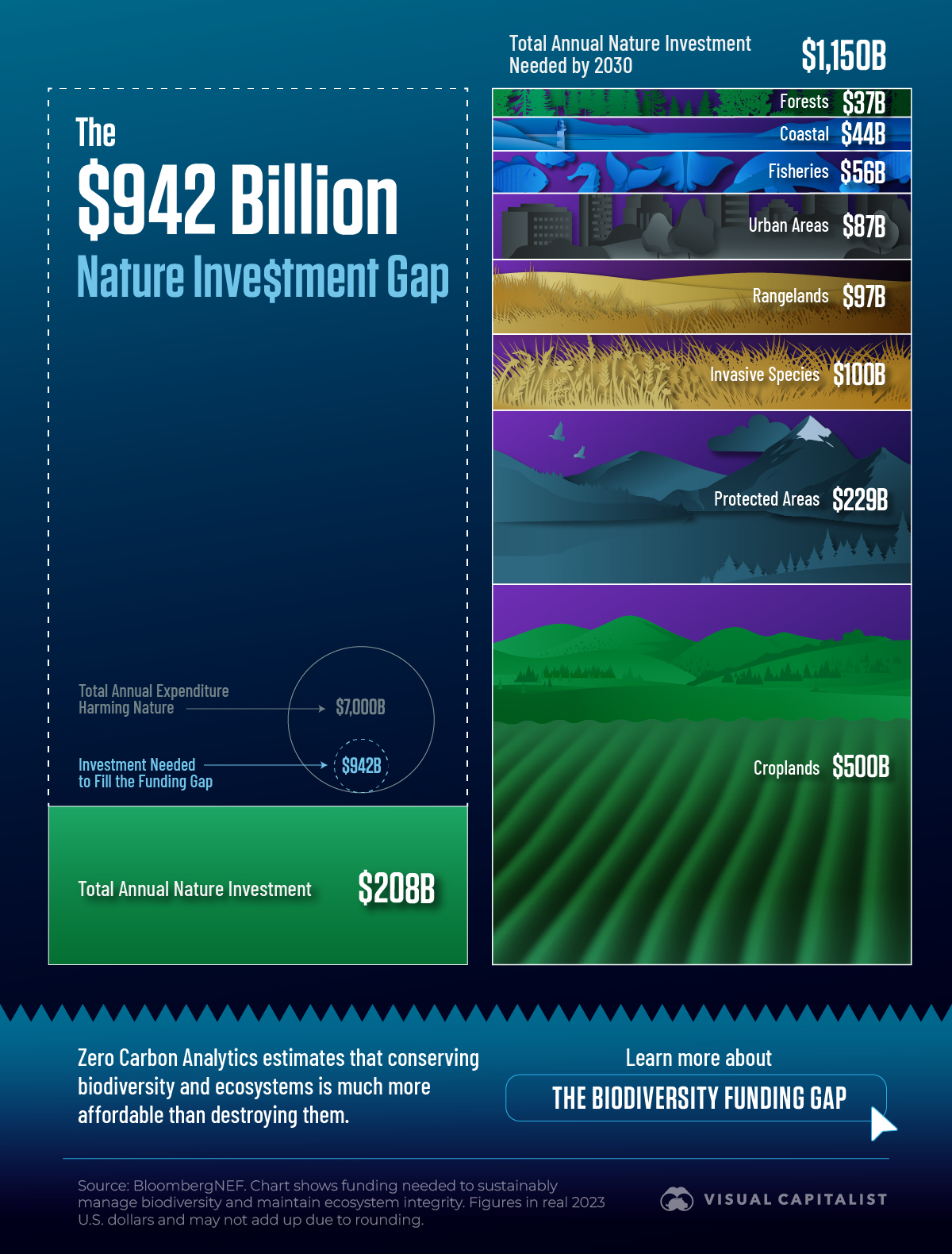

The Gap That Superorganism Identified

Kevin Webb and Tom Quigley, the managing directors at Superorganism, met in a way that felt almost accidental. Webb had been making angel investments in biodiversity startups independently, testing whether this could even work as a venture thesis. He was impressed by Quigley's background and reached out. The two started talking in 2022, and what began as a conversation turned into a mission.

Their timing was interesting. Climate tech had already exploded by then. Every venture fund was claiming climate credentials. You had massive funds like Breakthrough Energy raising billions. Specialized climate funds were everywhere. But biodiversity? That space was almost completely ignored by venture capital.

Why? A few reasons:

Biodiversity lacks the simplicity of carbon. Climate change has a clear metric: CO2 emissions. You can measure it. You can certify it. You can trade it. Biodiversity is messier. Protecting a forest helps bird populations, insect populations, water quality, carbon sequestration, and human health all at once. That's powerful, but it's also complicated to model financially.

The conservation space has historically been grant-driven, not venture-driven. Most biodiversity work happens through nonprofits, government agencies, and academic institutions. They're not looking for venture returns. They're looking for stable funding. That creates a market gap where venture capital doesn't naturally flow.

Biodiversity startups operate at different scales and geographies. A climate tech company might aim to reduce emissions across entire sectors globally. A biodiversity startup might focus on protecting a specific ecosystem in one region. That's just as important, but it doesn't fit the typical venture scale-up narrative.

Superorganism's insight was that these problems don't make biodiversity uninvestable. They make it underfunded. And where there's underfunding, there's opportunity.

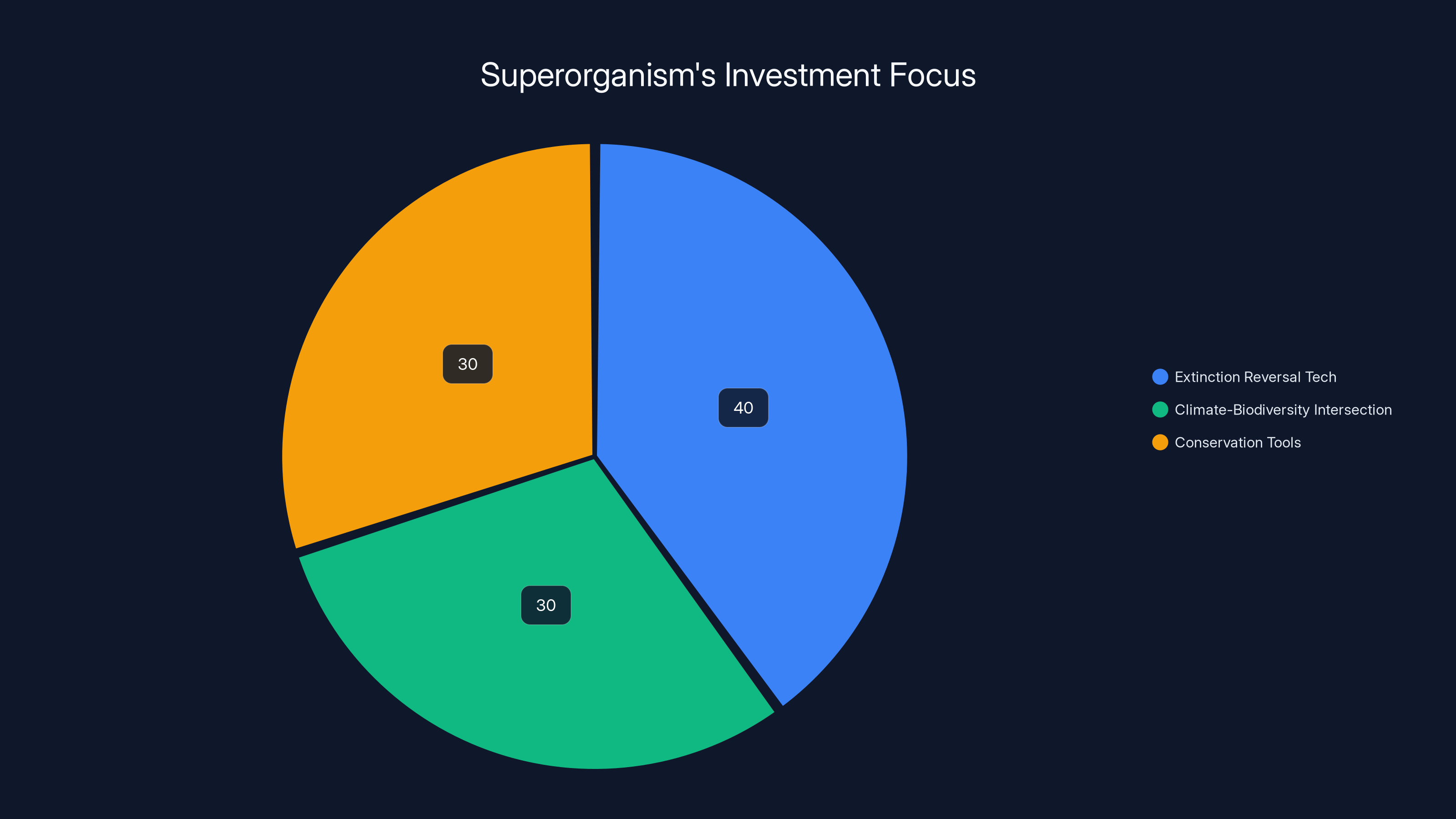

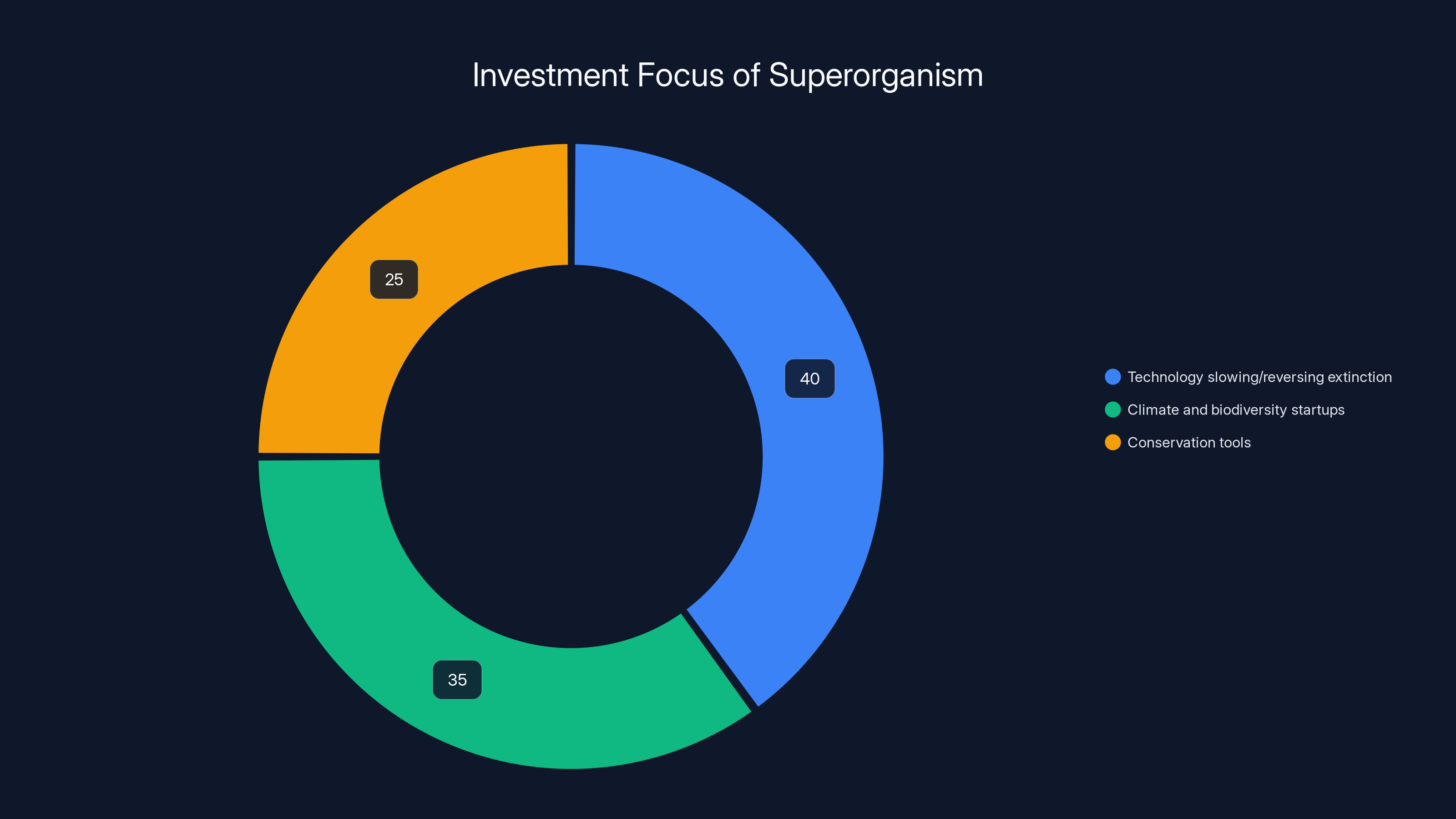

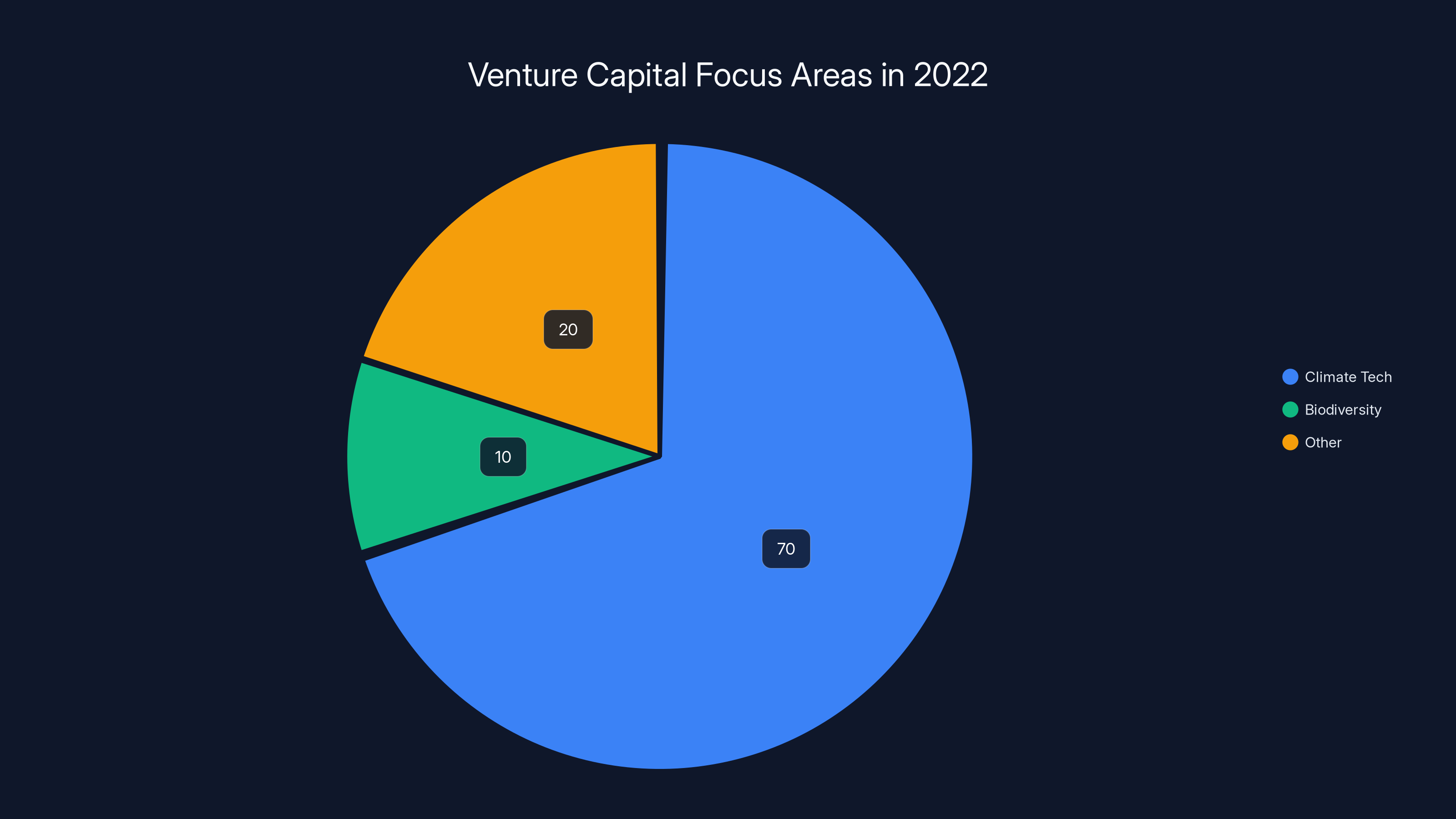

Superorganism invests in diverse areas with 40% in extinction reversal tech, and 30% each in climate-biodiversity intersection and conservation tools. Estimated data.

What Superorganism Actually Invests In

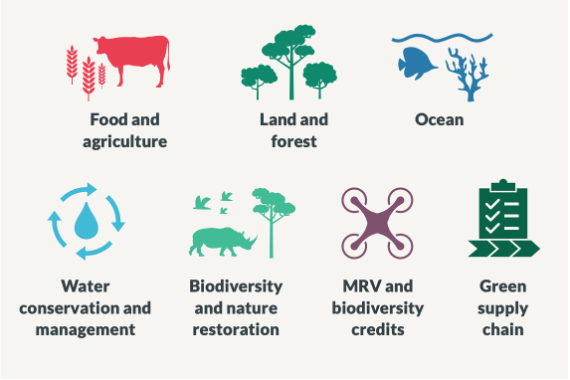

Superorganism doesn't just throw money at anything with "nature" in the pitch deck. The firm has a specific thesis broken into three categories:

Technology that slows or reverses extinction. This is the core. Companies building tools that directly prevent species loss. Computer vision systems that track animal populations. Software that optimizes habitat restoration. Genetic technologies that might save endangered species. If it moves the extinction needle, it qualifies.

Startups at the intersection of climate and biodiversity. These are companies that solve both problems simultaneously. Regenerative agriculture that sequesters carbon while restoring soil ecosystems. Renewable energy systems designed not to harm wildlife. Forest restoration that both captures carbon and rebuilds habitats. The best climate solutions actually benefit nature, and vice versa.

Tools that enable conservationists to do their work better. This is the infrastructure layer. Data management systems for tracking species populations. Drone technology for monitoring protected areas. Software platforms that help conservation organizations coordinate across regions. These aren't flashy, but they're critical. If you can make a conservation biologist 10 times more effective, that's a venture-scale business.

The firm makes checks ranging from

What's unusual is that Superorganism donates 10% of profits back to conservation efforts. That's unusual for venture capital, which typically returns all profits to limited partners. But here, the firm is essentially saying: "We're making money from biodiversity, so biodiversity gets a cut."

Spoor: A Case Study in Biodiversity as Venture Capital

One portfolio company illustrates exactly why this thesis works. Spoor uses computer vision to track bird movement and migration patterns.

Now, you might think: how is bird tracking a venture-scale business? Here's the thing. Wind turbines kill hundreds of thousands of birds annually. That's not just an environmental problem. It's a regulatory problem. Developers face strict environmental impact requirements. Projects get delayed. Sometimes they shut down entirely due to bird protection regulations.

Spoor's software helps wind farms identify where birds migrate, cluster, and move. Knowing this, developers can adjust turbine placement and operational patterns to minimize bird deaths. It's better for the birds. It's better for the wind farm. And it solves a real business problem that developers will pay to solve.

That's the Superorganism playbook: find the intersection where biodiversity and business incentives align. Don't ask companies to sacrifice profits for nature. Instead, show them that protecting nature is the profitable move.

Spoor didn't invent conservation. It invented a way to make conservation profitable for the organizations that currently harm wildlife. That's venture-scale thinking applied to biodiversity.

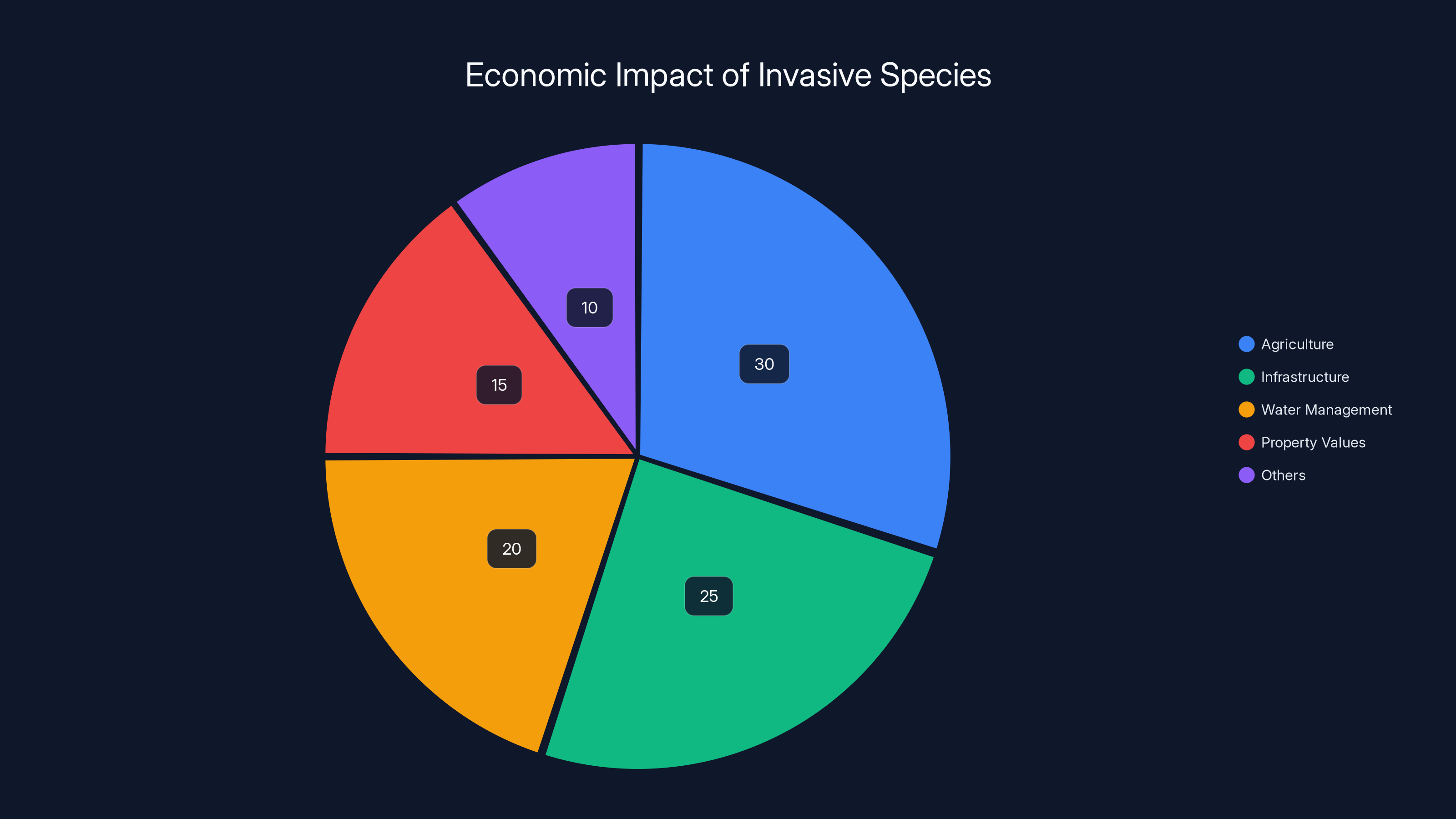

Invasive species cost the global economy an estimated $1.4 trillion annually, impacting agriculture, infrastructure, water management, and property values. Estimated data.

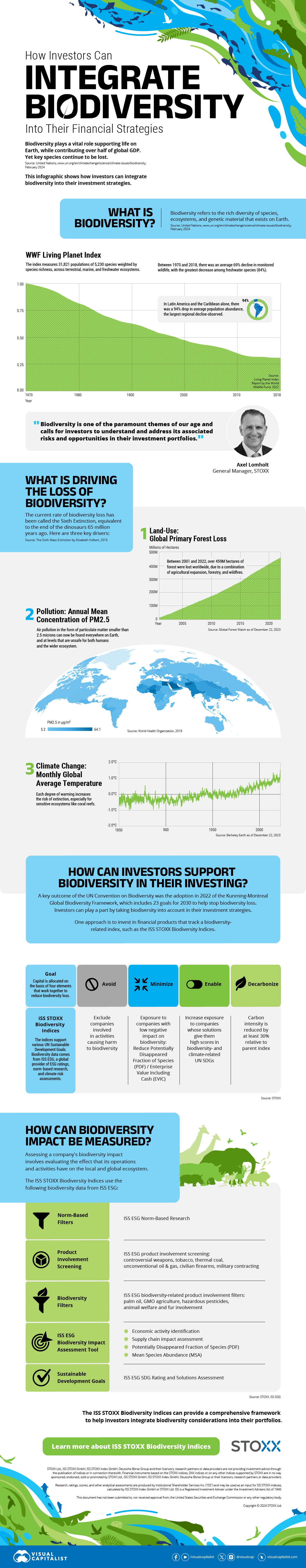

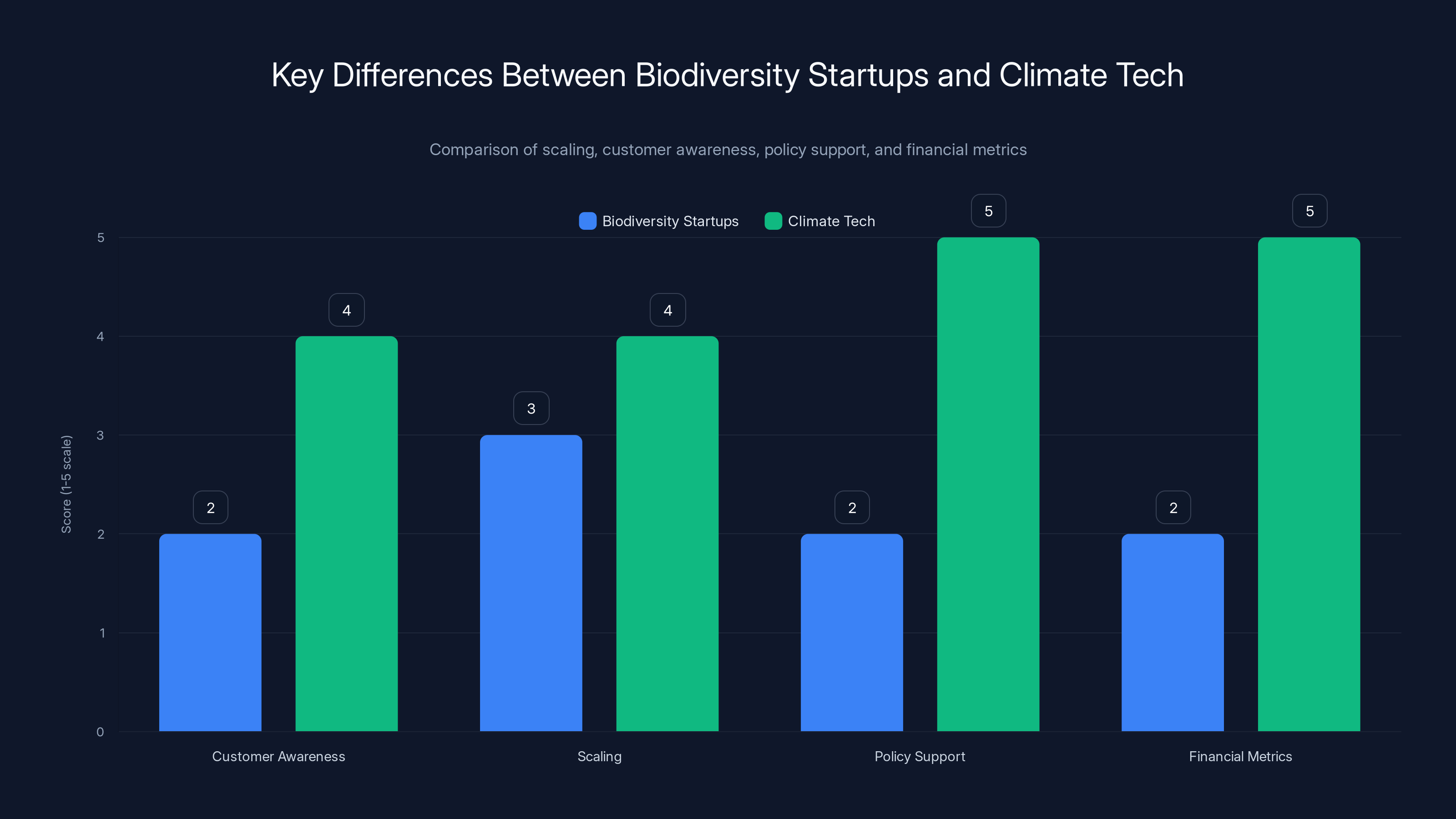

How Biodiversity Startups Differ From Climate Tech

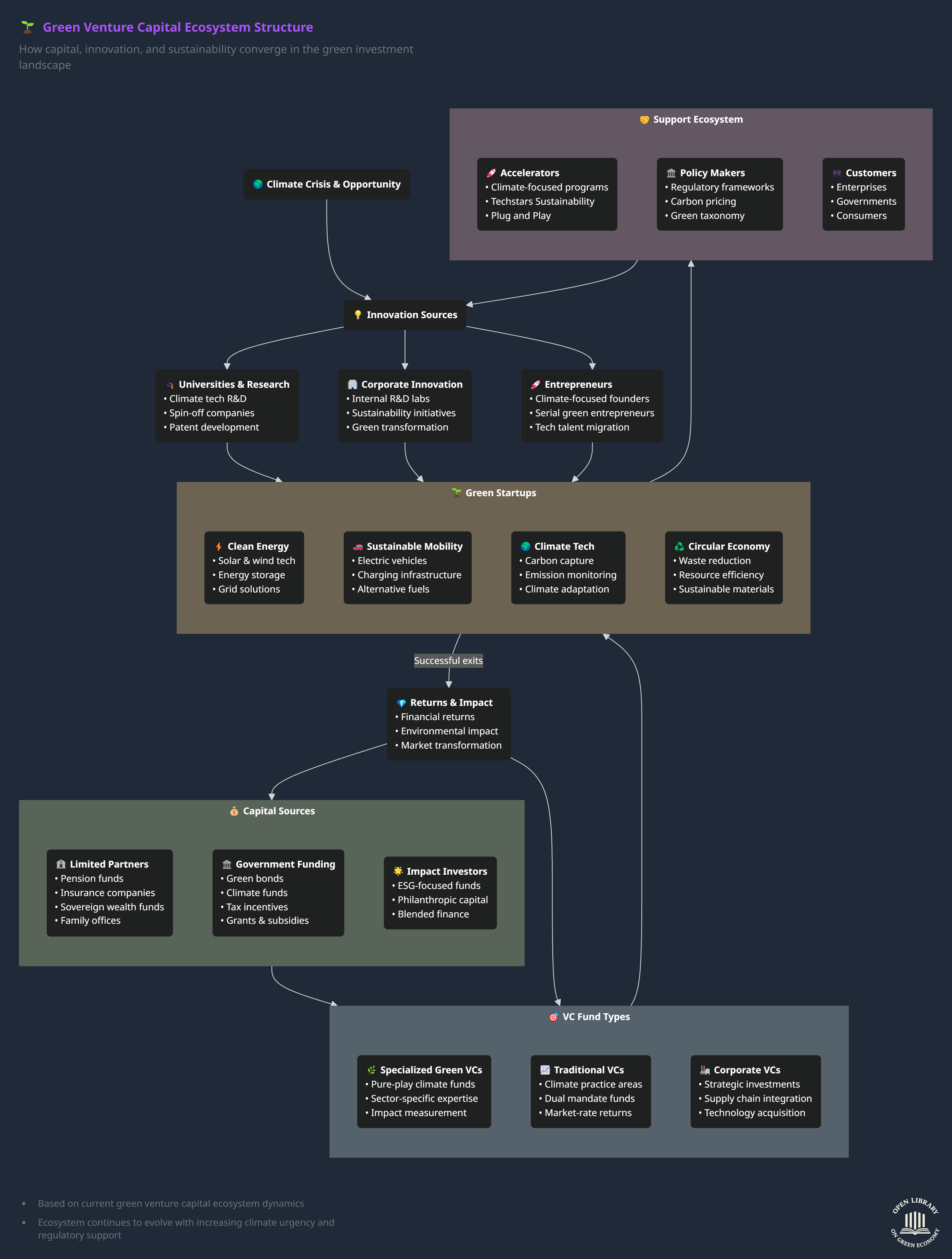

If you've followed climate tech, you might assume biodiversity startups work the same way. They don't. The differences matter for understanding why Superorganism needed to exist as a separate fund.

Climate tech has obvious customers: energy companies, utilities, industrial manufacturers. They're already spending billions on energy and emissions reduction. A climate tech startup can demonstrate savings or efficiency gains in their spreadsheet and get a contract.

Biodiversity startups often have to educate customers that they even exist. A wind farm developer might not know that bird tracking software is an option. A city planner might not realize that native plant restoration can replace costly stormwater infrastructure. You're not just selling a solution. You're selling the idea that the solution is possible.

Climate tech scales linearly. Cut emissions at one factory, and you've proven you can cut emissions at similar factories. Deploy solar panels in Texas, and you understand solar panels in Arizona.

Biodiversity scales regionally and ecologically. A restoration technique that works in a temperate forest might fail in a tropical rainforest. A species protection program effective in North America needs redesign for African habitats. Geography and ecology are features, not bugs, but they complicate scaling.

Climate tech has policy tailwinds everywhere. Every government on the planet is making climate pledges. Subsidies exist. Tax incentives exist. Regulations are increasingly favorable. That creates a growing market.

Biodiversity policy is fragmented and inconsistent. Some regions are aggressive about wetland protection. Others treat wetlands as development land. The lack of uniform policy makes it harder to scale biodiversity solutions globally.

Climate tech has clear financial metrics. Tons of CO2 avoided. Megawatts of clean energy. Dollars saved on energy bills. Financial return is tangible.

Biodiversity outcomes are harder to financialize. How do you value the return on investment from protecting 10,000 acres of habitat? What's the dollar value of saving a bird species from extinction? These are real questions that venture capital is just beginning to grapple with.

Superorganism's thesis is that these differences don't disqualify biodiversity from venture capital. They just require a different approach.

The Funding Landscape for Biodiversity Tech

Before Superorganism, biodiversity funding came from three sources:

Philanthropic grants. Major foundations like the World Wildlife Fund and The Nature Conservancy fund conservation work. But grants come with strings attached. They often fund long-term research with no expected financial return. That's important work, but it doesn't align with venture capital's need for returns.

Government and multilateral development agencies. USAID, the United Nations, and similar organizations fund conservation. But the process is slow, bureaucratic, and not designed for the iterative experimentation that startups need.

Impact investors and ESG-focused funds. Some venture funds have dedicated impact arms. But impact is usually secondary to financial returns. Biodiversity becomes a nice-to-have, not the core thesis.

Superorganism is trying to change that structure. By making biodiversity the central investment thesis, not a side benefit, the firm is signaling to the market: "This is investable. This matters. This is where returns and impact converge."

The $25.9 million raise proves the concept has appeal. It's a modest sum compared to megafunds raising billions, but it's significant because it shows that serious money—including money from traditional venture powerhouses like a16z—believes in biodiversity as a venture thesis.

The Portfolio Strategy: Building Diverse, Resilient Returns

Superorganism has already invested in 20 companies with plans to expand to about 35 companies for this fund. That's a deliberate decision.

Tom Quigley explained the reasoning: "We are purposely building a diverse portfolio. It allows us to show what the best biodiversity companies look like across all industries, across all tech types."

That's actually sophisticated portfolio management. Here's why it matters:

Biodiversity startups face sector-specific headwinds. One company might depend on government environmental regulations. If a new political administration rolls back those regulations, the company struggles. Another company might serve the renewable energy sector. If solar subsidies decline, that company suffers.

By building a diverse portfolio across multiple sectors, geographies, and biodiversity domains, Superorganism is hedging against any single policy or market headwind. If government environmental funding declines, maybe their private-sector biodiversity solutions perform better. If one region's regulations shift, biodiversity startups in other regions continue growing.

Quigley called it a "showcase portfolio." The idea is that by demonstrating success across multiple domains, Superorganism proves that biodiversity investment works broadly, not just in one niche. That makes it easier to raise a second fund. It also attracts other investors who might be skeptical of biodiversity as a thesis but can't argue with a portfolio showing success across different approaches.

One example: Inversa, a Superorganism portfolio company that turns invasive species into leather goods. This is a different play than Spoor's computer vision tracking. Inversa solves the invasive species problem—pythons in the Everglades, for example—by creating an economic incentive to remove them. The leather goods market provides demand. Remove pythons, sell leather, make money, restore the ecosystem.

That's so politically palatable that Ron DeSantis, the Republican governor of Florida, publicly praised Inversa for the Everglades python problem. Biodiversity in this framing transcends partisan climate debates. It's not about carbon or global warming. It's about invasive species and ecosystem restoration. That's something Republicans and Democrats can agree on.

That's Superorganism's real insight: biodiversity transcends the cultural divides around climate policy. You can protect nature without fighting about climate change. That makes it fundable for investors across the political spectrum.

Superorganism primarily invests in technology that slows or reverses extinction (40%), followed by startups at the intersection of climate and biodiversity (35%), and tools for conservationists (25%). Estimated data based on firm thesis.

The Political Context: Why Now?

The political climate around conservation has shifted dramatically since Superorganism started in 2022. In the United States at least, environmental protections became more contentious.

You might assume that would hurt Superorganism's fundraising. If the government is rolling back environmental regulations, how do you build venture businesses around environmental protection?

But it didn't slow the firm down. In fact, the changing political landscape may have actually clarified the thesis. Here's the logic:

If biodiversity startups depended on government support, they'd be fragile. One election, one administration change, and funding disappears. But if you build biodiversity companies that solve private-sector problems—wind farms need bird tracking, farms need soil restoration, developers need invasive species management—then political shifts don't kill the business.

Superorganism's portfolio reflects that thinking. Most companies aren't waiting for government grants. They're selling to businesses that benefit from biodiversity solutions regardless of political climate.

That's actually more venture-like. Traditional venture assumes you build businesses that work despite changing external conditions. Superorganism is applying that same principle to biodiversity.

Quigley noted that some potential investors needed help understanding how Superorganism differs from a climate fund. That's a sales challenge, but it's solvable. Once you look at the portfolio and see companies working across industries and geographies with different customer bases, it becomes clear: this is not just climate tech with a nature label. This is a different market.

Why Biodiversity Has Been Invisible to Venture Capital

Before Superorganism, biodiversity was essentially invisible to venture capital. That's not because biodiversity doesn't matter. It's because of structural reasons that are now changing.

Biodiversity losses are slow and invisible. Climate change affects energy costs, weather, infrastructure. You can see it in your utility bill. Biodiversity loss happens in ecosystems we don't directly interact with. A species going extinct in Southeast Asia doesn't directly impact a tech investor in Silicon Valley. Climate impacts do, eventually.

Conservation has never been venture-scale. The conservation sector operates at the scale of protected areas, habitat restoration projects, species recovery programs. These are measured in thousands of acres or hundreds of species. Venture capital wants to reach billions of people or businesses globally. The scale mismatch made biodiversity seem non-venture.

Biodiversity outcomes are hard to quantify financially. Climate tech companies can promise to avoid X tons of CO2, worth Y dollars at the carbon price. Biodiversity companies can't always make those promises. How much is it worth financially to save a bird species? To restore a wetland? These are genuine challenges for venture model fitting.

The conservation sector has alternative funding. Wealthy individuals fund conservation. Governments fund conservation. Large nonprofits command billions. Venture capital wasn't necessary because funding existed elsewhere. Climate tech was different. Carbon reductions were a new market, so venture capital had to invent them.

But now those barriers are eroding.

First, biodiversity is becoming visible. Climate impacts have drawn attention to ecosystems. People understand that nature collapse matters. News about species extinction has become mainstream.

Second, biodiversity is starting to have venture-scale applications. Computer vision for wildlife tracking. Drones for ecosystem monitoring. Data platforms for conservation coordination. These are inherently scalable technologies applied to biodiversity problems.

Third, some biodiversity outcomes are becoming financially quantifiable. Regenerative agriculture creates soil sequestration that has a price. Wetland restoration creates water quality benefits worth money. Invasive species removal creates products with market value.

Superorganism is betting that these trends continue. The firm is essentially timing a shift where biodiversity moves from "something governments and nonprofits handle" to "something venture-scale companies can build around."

The Inversa Example: Turning Invasive Species Into Revenue

Inversa's business model deserves deeper analysis because it illustrates how biodiversity becomes venture-scale.

Invasive species cost the global economy an estimated $1.4 trillion annually. That's not an environmental statistic. That's an economic problem that affects agriculture, infrastructure, water management, and property values.

Python invasion in the Florida Everglades is a classic case. The snakes have no natural predators. They've established a breeding population that's ballooning. They're eating native wildlife. They're disrupting the ecosystem. And they're extremely hard to remove because they're spread across millions of acres of swampy, difficult terrain.

Traditional solutions are state-sponsored hunting programs. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission pays people to hunt pythons. It's slow, expensive, and only scratches the surface of the problem. You're essentially paying people to hunt a species indefinitely.

Inversa's solution flips the model. Instead of paying hunters, create a market for python materials. Process python leather. Sell it as a product. Now you've created an economic incentive for python removal. Hunters profit directly from removing the invasive species. The market scales with leather demand. The more valuable the leather, the more pythons get removed.

That's venture-scale thinking. You're not asking the government for bigger budgets. You're creating a business that solves the invasive species problem while generating revenue.

The political brilliance is that this transcends environmental politics. DeSantis, a conservative governor, doesn't care about climate change. But he does care about Everglades pythons. They're a tangible, local problem. Inversa's solution is bipartisan in a way that carbon reduction isn't.

That's why Superorganism invested in Inversa. It shows that biodiversity startups can:

- Solve real, expensive problems

- Generate revenue that covers costs

- Appeal across political divides

- Scale without government dependency

- Create markets where none existed before

That's the venture capital playbook. Superorganism is just applying it to nature.

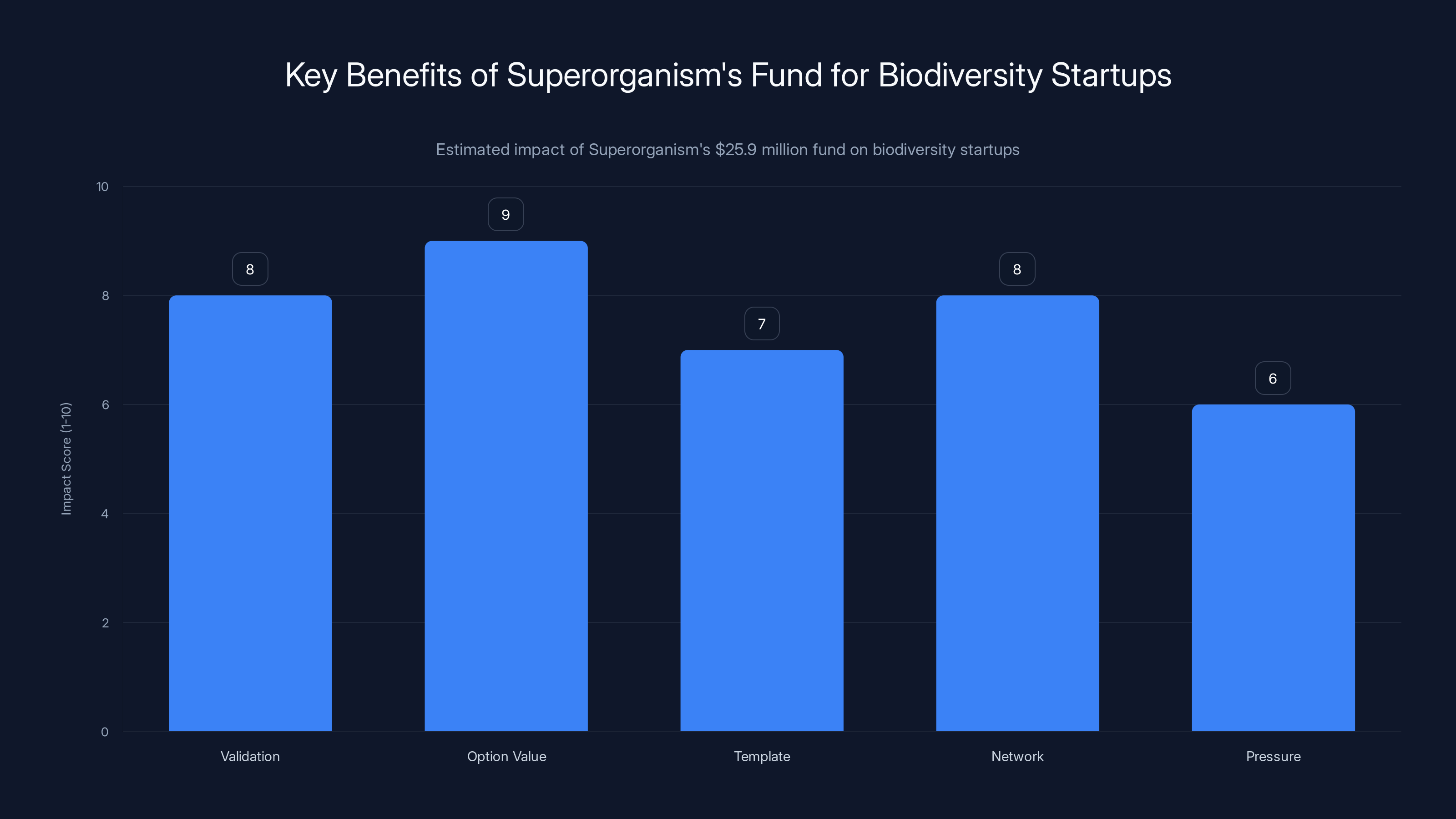

Superorganism's fund provides significant validation and option value for biodiversity startups, with strong network benefits but also increased pressure. Estimated data.

The Spoor Model: Computer Vision as Conservation Infrastructure

Spoor takes a different approach than Inversa, and that's the point. Superorganism is backing multiple pathways to biodiversity solutions.

Spoor's technology is simpler conceptually but elegant in execution. Use computer vision and acoustic sensors to track bird behavior around wind turbines. Identify migration patterns, species presence, and collision risk. Then adjust wind turbine operations to minimize bird deaths.

Why does this work financially? Because wind farms are economically incentivized to reduce bird deaths. They face regulatory penalties. They face public relations problems. They face legal liability. Reducing bird mortality saves them money.

The customer for Spoor isn't a conservation nonprofit or government agency. It's a private wind farm operator trying to reduce liability and operational risk.

That's fundamentally different from traditional conservation. You're not asking a company to sacrifice profits to help the environment. You're selling them a tool that reduces their costs and risk. The environmental benefit is the outcome, not the pitch.

Spoor represents the infrastructure layer of biodiversity tech. It's not directly protecting birds. It's creating the data systems that let companies make decisions that protect birds. That's scalable because every industrial operation that affects wildlife could eventually use similar tracking and optimization tools.

Imagine this applied broadly:

- Shipping companies using acoustic tracking to avoid whale migration zones

- Agricultural drones using computer vision to protect ground-nesting birds

- Power companies using thermal imaging to identify bat populations near transmission lines

- Mining operations using soil sensors to protect underground ecosystems

In each case, the company isn't doing it for conservation. It's doing it to reduce operational risk, meet regulations, or save money. But the biodiversity outcome is the same.

That's why Spoor is venture-scale and why Superorganism invests in it. The market is much larger than pure conservation. It's every company that operates in nature and wants to operate more efficiently.

Building a Repeatable Investment Thesis in Biodiversity

For Superorganism to succeed long-term, the firm needs to repeat the Inversa and Spoor successes at scale. That requires building a repeatable thesis.

Quigley described the approach: "We recognize that we're the first and we need to be there to sort of bring others along where they might be interested in taking their first bet on biodiversity, helping them find and support the right ones that can move the needle."

That's an interesting articulation. Superorganism isn't just making investments. It's trying to establish biodiversity as a legitimate venture category. The firm is the market maker.

To do that, Superorganism needs to:

Demonstrate repeatable outcomes. The portfolio companies need to hit milestones, achieve traction, and ideally generate returns. If Spoor grows and reaches profitability, that's a signal to other investors that biodiversity companies can execute like any other venture company.

Build evidence that biodiversity investors are as smart as climate investors. Climate tech investors have earned credibility. Biodiversity investors are proving themselves now. The quality of decision-making matters. Picking winners matters. Superorganism needs a track record that shows good judgment.

Create deal flow advantage. As more people know Superorganism focuses on biodiversity, entrepreneurs building in this space will naturally come to the firm. That creates information advantage and investment advantage.

Educate the market. Many smart venture capitalists simply haven't considered biodiversity. Superorganism is essentially creating the narrative that makes biodiversity investable. Every press release, every portfolio announcement, every founder highlight is part of establishing this as a real category.

Prove that biodiversity isn't charity. This might be the most important. Venture capital wants returns. If Superorganism can demonstrate that biodiversity businesses generate venture-scale returns, that changes the entire dynamic. You're not investing to feel good. You're investing because it's a good investment that happens to save species.

The

What's Inside Superorganism's Portfolio

Beyond Spoor and Inversa, Superorganism's 20-company portfolio spans:

Ecosystem restoration at scale. Companies using technology to identify, restore, and monitor habitats. This includes wetland restoration, coral reef protection, forest recovery, and grassland rehabilitation. The technology layer—drones, sensors, data platforms—makes this venture-scale.

Genetic and biotech approaches to conservation. Some portfolio companies are exploring how genetic technology might help endangered species. This is controversial territory, but frontier biodiversity tech often is.

Data platforms for conservation organizations. Software that helps conservation nonprofits coordinate, track, and measure impact. These are B2B SaaS companies that serve the nonprofit sector at scale.

Supply chain solutions tied to biodiversity. Companies helping corporations track and improve the biodiversity impact of their supply chains. As ESG becomes standard, companies want to measure and improve their environmental impact. Supply chain biodiversity tracking is emerging.

Climate-biodiversity integration. Companies working at the intersection, like regenerative agriculture that both sequesters carbon and restores soil ecosystems.

The diversity is intentional. It signals that biodiversity is a broad category with many pathways to solutions, not a narrow niche.

Climate tech generally scores higher in customer awareness, scaling potential, policy support, and financial metrics compared to biodiversity startups. Estimated data based on qualitative analysis.

The Financial Model: How Do Biodiversity Startups Actually Make Money?

This is the crux of the venture question. If you're building a biodiversity startup, you need a business model that works like any other venture company. How does that actually happen?

Inversa: Leather goods and harvesting services. The company harvests invasive species and sells the materials. Revenue comes from the product sales. That's a traditional business model.

Spoor: Software licensing and services. Wind farms pay for tracking and optimization software. That's B2B SaaS, a proven venture model.

Other ecosystem restoration companies: Contracts for habitat restoration from governments, corporations, and nonprofits. That's service-based revenue.

Data and monitoring platforms: Software subscriptions. Conservation organizations pay to use the platform. That's SaaS again.

Genetic and biotech plays: Licensing technology, selling genetic materials, government contracts. That mirrors biotech venture models.

The pattern is clear: biodiversity startups make money the same way other startups do. They're not dependent on altruism or charity. They're selling products and services that solve real problems.

The difference is that the problems they solve happen to improve biodiversity. That's the insight. It's not that conservation is special. It's that conservation is increasingly a business problem, not just an environmental problem.

A corporation's supply chain affects ecosystems. That's a business problem worth solving. A wind farm kills birds. That's a regulatory and liability problem worth solving. An invasive species destroys infrastructure. That's an economic problem worth solving.

Investors get returns. Customers solve problems. Biodiversity improves. Everyone wins.

That's why Superorganism works as a venture firm, not just a nonprofit.

The Competition: Emerging Biodiversity-Focused Investors

Superorganism was first, but it won't be alone forever. The success of the $25.9 million raise signals market interest, and other investors are watching.

Some traditional venture firms are starting biodiversity practices. Impact-focused funds are adding biodiversity theses. Even mainstream firms are recognizing that nature-tech is underexplored.

That's actually good for Superorganism. It means the category is real and growing. It increases deal flow. It validates the thesis. The firm benefits from rising tide as biodiversity investment becomes mainstream.

But it also means Superorganism has to execute. Being first is an advantage, but only if you build a reputation for finding winners, supporting founders effectively, and generating returns.

The next three years are critical for Superorganism. If the portfolio companies grow, raise follow-on funding, and eventually exit profitably or through acquisition, the firm becomes a model. If they stall or fail, the biodiversity thesis becomes harder to fund.

That's true of any venture fund, but it's especially true for category creators. Superorganism is building something new. The burden is on them to prove it works.

Lessons From Climate Tech: What Biodiversity Can Learn

Biodiversity tech is roughly where climate tech was five to ten years ago. Climate tech has had a head start, and there are lessons Superorganism can learn:

Scale requires multiple approaches. Climate tech succeeded because investors backed many different solutions: solar, wind, batteries, carbon capture, efficiency, etc. The winners weren't obvious upfront. Biodiversity is similar. There's no single solution to species extinction. Superorganism's diverse portfolio is the right move.

Policy creates market but isn't necessary. Climate tech benefited from subsidies and mandates. But the strongest climate companies eventually worked even without subsidies because they became cost-competitive. Biodiversity startups shouldn't depend on government support. They should solve business problems so clearly that customers want them regardless of policy.

Integration with incumbent industries is hard but powerful. The most successful climate companies integrated into existing industries—solar into energy, EVs into transportation, heat pumps into HVAC. Biodiversity companies need similar integration. Spoor's integration into wind farms is a model. Regenerative agriculture's integration into food production is another.

Storytelling matters. Climate tech benefited from clear environmental narratives. Climate change is bad. Carbon is bad. Reduction is good. Biodiversity narratives are fuzzier. "Extinction is bad" is obviously true, but it's less emotionally compelling to investors than clear climate metrics. Superorganism needs to develop narratives that make biodiversity as compelling as climate change.

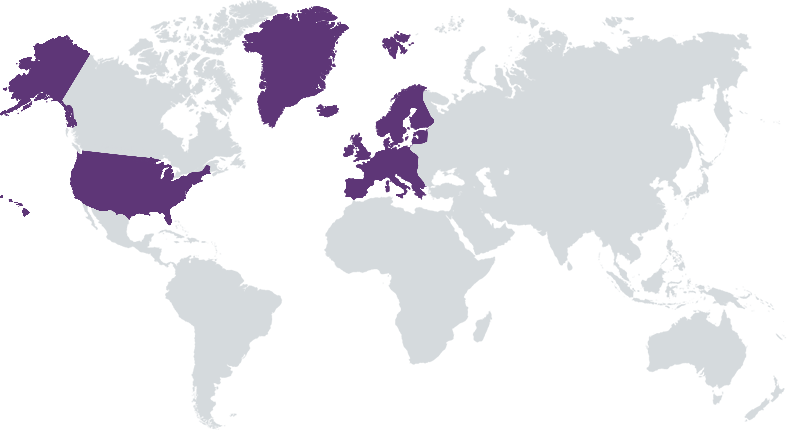

International opportunity is huge. Biodiversity loss is global, and solutions will be too. Climate tech is increasingly international. Biodiversity tech should be also. Superorganism's current portfolio seems U.S.-focused, but future success requires global reach.

In 2022, an estimated 70% of venture capital was focused on climate tech, while only 10% was directed towards biodiversity, highlighting a significant funding gap. (Estimated data)

The Path to Scale: From 35 Companies to Venture Category

Superorganism's plan for this fund is to invest in about 35 companies total. That's a reasonable portfolio size for a

But here's the real milestone: a second fund. If Superorganism can raise a Series II fund of $75-100 million or more, the category becomes real. That signals that the first fund performed well enough to justify a larger second fund.

Raising a second fund requires:

Portfolio traction. Companies need to grow, hit milestones, and show progress. Some need to raise follow-on rounds from other investors. That's validation.

Fund returns. At least some portfolio companies need to be on paths to meaningful exits or clear profitability. That's how venture funds return capital.

Market expansion. The biodiversity market needs to grow. More entrepreneurs building in the space. More customers willing to buy biodiversity solutions. More awareness that this is a real category.

LP satisfaction. Limited partners need to believe in the thesis and trust the team. They need to feel like Superorganism is executing and making smart bets.

All of this takes time. Superorganism probably has 3-5 years before a second fund becomes feasible. That's enough time for the portfolio to mature, some exits to happen, and the market to develop further.

If all goes well, the outcome is that biodiversity becomes a permanent venture category like climate tech or fintech. Multiple funds exist. Deal flow is robust. Companies scale. The ecosystem matures.

If it doesn't work, biodiversity tech remains underfunded relative to its importance, and Superorganism's venture into this space becomes a footnote in venture history.

The Larger Context: Why Biodiversity Matters to Everyone

Beyond venture capital, biodiversity matters because it's foundational to human survival. This isn't hyperbole.

Biodiversity underpins ecosystem services. Pollinators create one-third of global food production. Forests regulate water cycles. Wetlands filter water. Soil microbiota enable agriculture. Collapse these systems and human civilization has serious problems.

Biodiversity provides genetic resources. Most medicines come from natural compounds or organisms. Future medicines probably will too. Losing species means losing pharmaceutical potential.

Biodiversity enables adaptation. As climate changes, ecosystems with high biodiversity are more resilient. They adapt. Monocultures don't. We need biodiverse ecosystems to survive climate change.

Biodiversity represents irreplaceable value. Once a species goes extinct, it's gone forever. Some ecosystem services can't be replaced by technology. You can't synthetic pollination. You can't replace complex soil ecosystems artificially at scale.

From a purely selfish human perspective, protecting biodiversity is protecting the systems that keep us alive.

Venture capital is a tool for solving problems at scale. If biodiversity loss is a problem, venture capital is a legitimate tool for scaling solutions. That's what Superorganism is betting on.

Whether that bet works is an open question. But the existence of Superorganism signals something important: the smartest people in venture capital are starting to recognize biodiversity as a real problem and a real opportunity.

The Realistic Constraints and Challenges Ahead

Let's be honest about what Superorganism is up against:

Biodiversity is inherently local. You can deploy solar panels anywhere and they work the same way. You can't deploy species restoration the same way globally. That limits scalability in the traditional venture sense.

Government policy is uncertain. Climate policy is increasingly bipartisan. Biodiversity policy is more uncertain. A new administration could shift focus. That creates risk for investors and founders.

Most biodiversity value is hard to capture financially. The real value of protecting a rainforest accrues to humanity broadly, not to the companies protecting it. That's an "externality" problem in venture terms. Companies can't capture all the value they create, which limits returns.

The timeline is long. Ecosystem restoration takes decades. Species recovery takes generations. Venture capital wants returns in 5-10 years. That's a mismatch.

Market size is uncertain. Climate tech has a clear market: global energy systems worth trillions. Biodiversity tech's market is less obvious. How many companies can operate in this space? What's the total addressable market? That's still being figured out.

Execution risk is high. Biodiversity is complex science. Getting it wrong has real consequences. That's different from a software startup where mistakes are correctable.

Superorganism isn't claiming these challenges don't exist. The firm is betting that despite these constraints, venture capital can still work in biodiversity. That some companies will figure out how to scale solutions, generate returns, and improve biodiversity outcomes simultaneously.

That's a harder bet than typical venture. But if it pays off, the impact is enormous.

What This Means for Entrepreneurs

If you're building a biodiversity startup, what does Superorganism's $25.9 million fund mean for you?

Validation: The biggest venture funds and investors take biodiversity seriously. That's validation that your problem is real and your market exists.

Option value: You now have a venture fund that specifically understands biodiversity. That's advantageous because you don't have to educate them on why your business matters.

Template: Superorganism's portfolio companies provide templates for what works. Inversa shows how to create revenue from invasive species. Spoor shows how to sell B2B SaaS to private companies operating in nature.

Network: Superorganism brings together biodiversity entrepreneurs. That creates peer learning, partnership opportunities, and visibility across the portfolio.

Pressure: Being in Superorganism's portfolio comes with higher expectations. The firm is betting on you to prove the biodiversity category works. That's motivating but also demanding.

If you're building in biodiversity and seeking funding, Superorganism is an obvious first meeting. But you should also approach traditional climate funds and impact investors. The more capital flowing to biodiversity, the better.

And if your biodiversity startup is VC-scale (can generate venture returns, scale to meaningful size, create defensible business), you should consider Superorganism first. They speak the language, they understand the space, and they have skin in the game for your success.

The Long-Term Vision: Biodiversity as a Venture Category

If Superorganism succeeds, the long-term outcome is that biodiversity becomes a permanent venture capital category.

That doesn't mean every venture fund focuses on biodiversity. Climate tech didn't displace traditional venture. It became a subset. Similarly, biodiversity tech would become its own category, with specialized funds, dedicated LPs, and an ecosystem of companies.

Here's what that future looks like:

Multiple biodiversity-focused funds exist. Superorganism is joined by competitors. Maybe tier-one firms like a16z or Sequoia develop biodiversity practices. Maybe new funds specialize specifically in biodiversity. Competition drives better capital allocation and better outcomes.

Universities and governments fund biodiversity ventures. Just as government agencies invest in climate tech, they invest in biodiversity tech. That provides additional capital and institutional support.

Biodiversity startups reach scale. Some companies in Superorganism's portfolio or competitors become the "unicorns" of biodiversity. They raise large later-stage rounds. They expand globally. They achieve real impact at scale.

Corporate investment increases. Major corporations increasingly see biodiversity tech as strategic. They make corporate venture investments. They acquire companies. They partner on solutions.

Technology maturity increases. Computer vision for wildlife monitoring improves. Data platforms for conservation scale. Genetic technologies for species recovery advance. The tools become mainstream.

Biodiversity becomes normalized as a business category. Just as climate tech is no longer exotic, biodiversity tech becomes normal. Investors evaluate it on the same metrics as other venture: market size, TAM, growth potential, founding team.

That's the vision. Whether it comes true depends on execution. Superorganism has the first step right: a fund, a thesis, a portfolio. Now comes the harder part: proving that the thesis works.

Conclusion: The Beginning of Biodiversity as Venture Capital

Superorganism's $25.9 million fund is significant not because it's the largest fund ever raised for biodiversity tech. It's not. It's significant because it represents a shift in how venture capital thinks about nature and conservation.

For decades, venture capital focused on digitizing human systems, improving human convenience, and scaling human-centric technology. Biodiversity was invisible to the venture ecosystem. It was someone else's problem. Government. Nonprofits. Foundations.

Superorganism's bet is that biodiversity is actually a venture problem. That there are billion-dollar opportunities in preventing extinction, protecting ecosystems, and building the tools to do it at scale.

More importantly, the firm is betting that solving biodiversity problems can be profitable. Not as charity. Not as a side benefit of a profitable company. But as the core business model.

That's radical. And it's only possible if you structure the problem correctly. You need entrepreneurs who see a business problem in biodiversity loss. You need investors who recognize that profit and planet protection can align. You need customers willing to pay for solutions.

Superorganism is providing two of those. The third—customers willing to pay—already exists. Wind farms need to reduce bird deaths. Invasive species harm agriculture. Ecosystem damage costs money. The demand is there. The question is whether the supply of solutions scales.

The next five years will tell. If Superorganism's portfolio companies grow, raise follow-on rounds, and generate returns, the category is real. If they stall, biodiversity remains underfunded and venture-overlooked.

But either way, something important has shifted. The largest venture investors are no longer ignoring biodiversity. They're building theses around it. They're deploying capital. They're attracting founders and entrepreneurs.

That's the beginning of something. Whether it becomes a permanent venture category depends on execution. But for the first time in venture capital history, biodiversity has a seat at the table.

TL; DR

- Superorganism closed a $25.9M fund dedicated exclusively to biodiversity startups, representing the first major venture capital bet on nature-tech as a venture category

- The firm invests in three categories: technology reversing extinction, climate-biodiversity intersections, and tools enabling conservation work at scale with checks of 500K

- Portfolio companies like Spoor and Inversa demonstrate venture-scale business models: Spoor sells bird-tracking software to wind farms; Inversa monetizes invasive species removal through leather goods

- Biodiversity has been venture-invisible due to lack of clear financial metrics, policy fragmentation, and traditional nonprofit funding models, creating a massive gap Superorganism is trying to fill

- The fund's success depends on proving biodiversity solutions generate venture returns rather than relying on charity or government support, making profit and planet protection align

FAQ

What is Superorganism and why does it matter?

Superorganism is the first venture capital fund dedicated exclusively to biodiversity startups. The firm raised $25.9 million in 2026 with backing from Cisco Foundation and a16z partner Jeff Jordan. It matters because it signals that venture capital is beginning to recognize biodiversity loss as a solvable, fundable problem with venture-scale business opportunities, not just a nonprofit or government concern.

How is Superorganism different from a climate tech fund?

While climate tech focuses on reducing carbon emissions with clear financial metrics, Superorganism targets species extinction and ecosystem protection, which have messier financial models and regional variations. Superorganism intentionally builds a diverse portfolio across industries and geographies to prove biodiversity solutions work broadly and aren't dependent on any single policy or market sector.

What types of companies does Superorganism back?

The firm invests in three categories: technology that slows or reverses extinction (like computer vision for wildlife tracking), startups at the climate-biodiversity intersection (like regenerative agriculture), and tools enabling conservationists to work more effectively (like data platforms). Check sizes range from

Why should I care about biodiversity if I'm an investor or entrepreneur?

Biodiversity loss costs the global economy an estimated $1.4 trillion annually through damage to agriculture, infrastructure, and water management. For investors, this represents an emerging venture category with low competition and high impact potential. For entrepreneurs, Superorganism's fund suggests investors are now actively seeking biodiversity solutions, creating capital availability where none existed before.

How do biodiversity startups make money if they're focused on conservation?

Unlike traditional conservation which relies on grants, biodiversity startups solve private-sector problems. Spoor sells bird-tracking software to wind farms trying to reduce regulatory liability. Inversa harvests invasive species and sells leather goods. The pattern is solving real business problems whose solution also improves biodiversity, creating alignment between profit and planet protection.

What's the realistic timeline for biodiversity tech to become a major venture category?

Biodiversity tech likely follows climate tech's trajectory, which took 10-15 years to mature from early venture investment to mainstream category. Superorganism needs to demonstrate portfolio success within 3-5 years to raise a larger second fund, which would signal true market maturation. Full category establishment probably takes another 5-10 years beyond that as more funds enter and companies scale.

Looking Ahead in Biodiversity Technology

The significance of Superorganism's fund extends beyond a single investment. It represents a structural shift in how capital flows to nature-related problems. As climate policy becomes more politically contentious, biodiversity offers a path to conservation that transcends partisan debates. Species protection, invasive species removal, and ecosystem restoration appeal across the political spectrum, making biodiversity tech potentially more resilient than climate tech to political headwinds.

For founders building in this space, the window is open. Most biodiversity problems remain unsolved because no one was backing venture teams to solve them at scale. That's changing. The combination of increasing environmental awareness, maturing technology (computer vision, sensors, data platforms), and capital availability means the next five years will likely see explosive growth in biodiversity startups.

The real question isn't whether Superorganism's thesis is valid. It is. Biodiversity matters, it has economic consequences, and venture-scale solutions are technically feasible. The question is whether the firm can execute well enough to raise a second fund and establish biodiversity as a permanent venture category. If Superorganism succeeds, others will follow. The biodiversity startup ecosystem will mature. Capital will flow where it's been absent for decades.

That's not just good for nature. It's good for returns. And in venture capital, when profit and impact align, change happens fast.

Key Takeaways

- Superorganism raised $25.9 million as the first venture capital fund exclusively focused on biodiversity startups, signaling major investor recognition of nature-tech as a venture category

- Portfolio companies like Spoor (bird tracking for wind farms) and Inversa (invasive species monetization) demonstrate how biodiversity solutions can align profit incentives with conservation outcomes

- Biodiversity tech differs fundamentally from climate tech due to harder financial metrics, regional variation, and lack of uniform policy support, requiring specialized venture fund expertise

- The fund's success depends on proving biodiversity startups can generate venture-scale returns within 5-7 years to justify raising a larger second fund and establishing the category permanently

- Entrepreneurs building biodiversity solutions now have access to capital previously unavailable, but success requires solving clear business problems where environmental benefit is the secondary outcome

![Superorganism's $25M Biodiversity Fund: How VC is Reshaping Conservation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/superorganism-s-25m-biodiversity-fund-how-vc-is-reshaping-co/image-1-1768309796149.jpg)