Introduction: The Brownie Recipe Problem That Changed AI Architecture

You ask an AI chatbot for a brownie recipe. It gives you one. Simple, right?

Now imagine that same AI running an entire grocery delivery system. A customer wants brownies. The system needs to understand what makes brownies, what ingredients they need, what's actually available in that customer's local store, what substitutes exist if something's out of stock, whether the items will spoil during delivery, and how fast it needs to arrive. All in under a second.

This is the "brownie recipe problem," and it's not actually about baking at all.

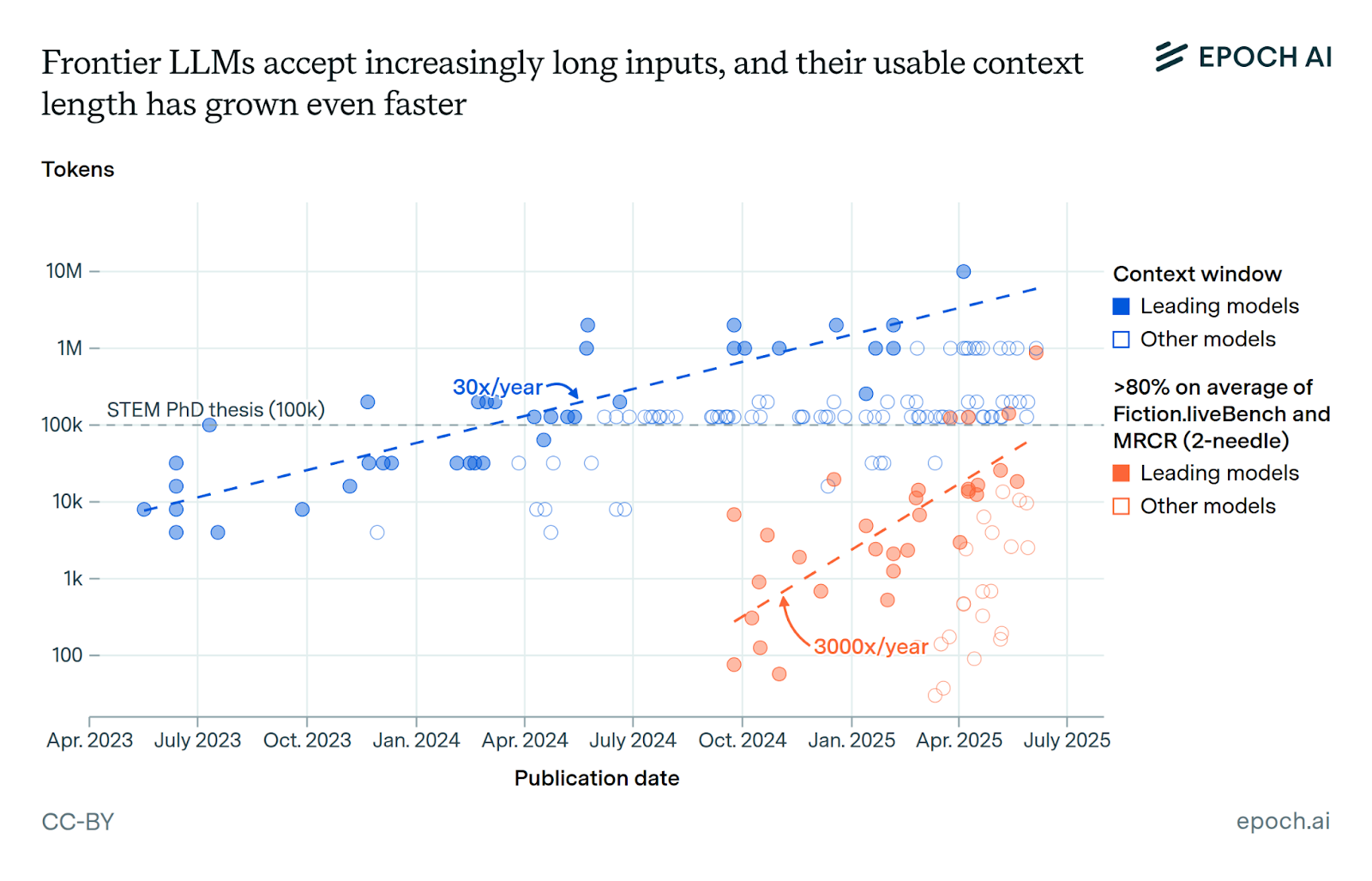

The problem reveals something fundamental about how modern large language models work versus how they need to work in production systems. When you scale an LLM from answering questions to orchestrating real-time commerce, reasoning, and logistics, the architecture breaks down. The model either becomes too slow (reasoning takes 15 seconds) or loses critical context (the customer can't get their order in time).

This challenge isn't unique to grocery delivery. It shows up in customer service systems, financial trading platforms, supply chain management, healthcare applications, and anywhere a machine needs to understand intent while navigating real-world constraints.

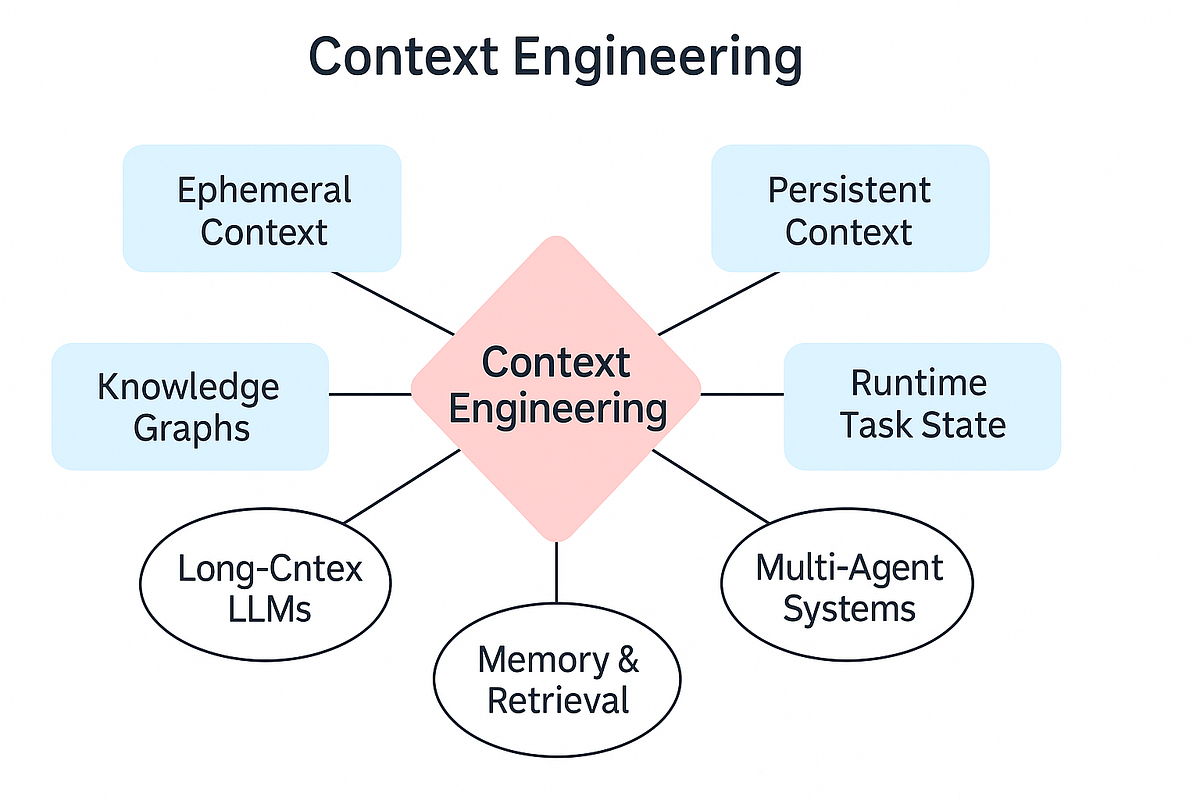

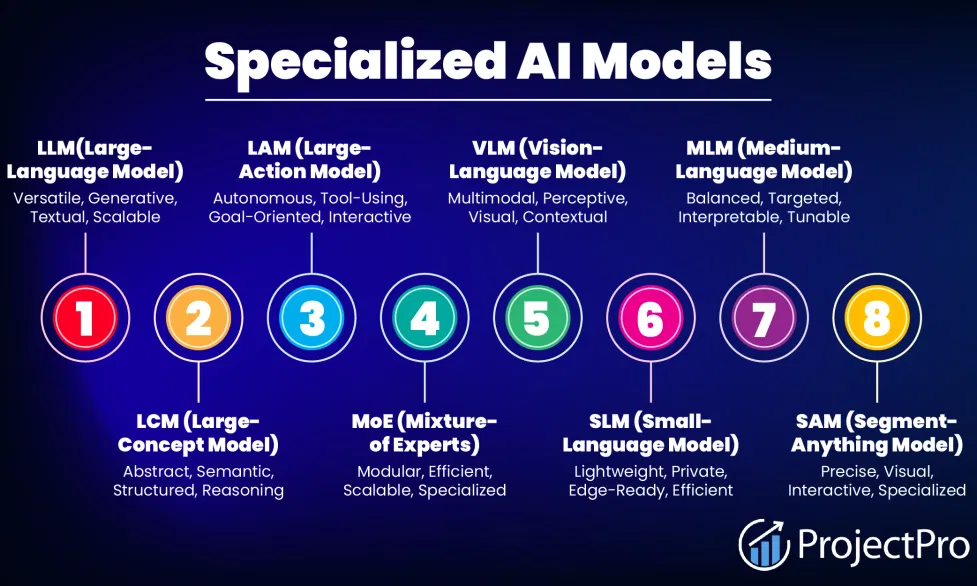

The companies solving this problem aren't just tuning prompts or fine-tuning models. They're rethinking how context flows through systems entirely. They're splitting reasoning across specialized models, implementing protocol standards to connect to external tools, and building agent networks that mirror how human teams organize work.

What started as a grocery delivery problem has become the central architectural question of production AI: How do you give language models enough context to be genuinely useful without making the system too slow to actually use?

This article breaks down the brownie recipe problem in detail, explores why naive approaches fail, and shows you the architectural patterns that successful companies are using to solve it right now.

TL; DR

- The Core Problem: LLMs need fine-grained context about inventory, user preferences, logistics, and real-world constraints to provide useful real-time recommendations, but loading all this context directly into the model causes latency and resource explosion.

- Why It Matters: Response times matter more than reasoning depth in production systems. If an interaction takes 15 seconds, users leave. If it takes 500 milliseconds, they stay.

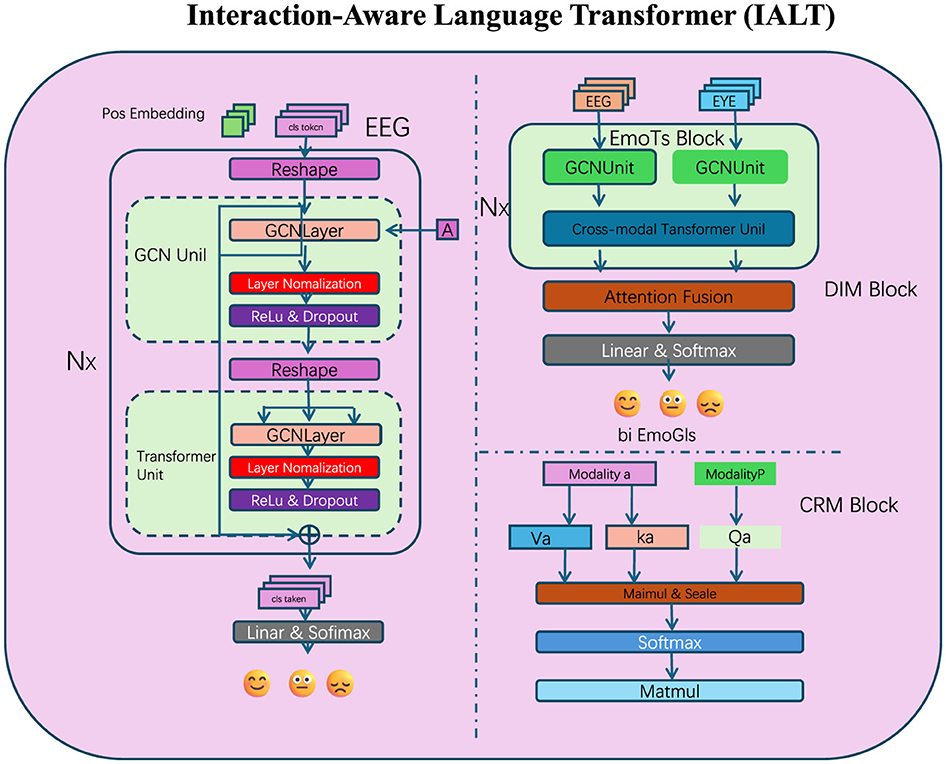

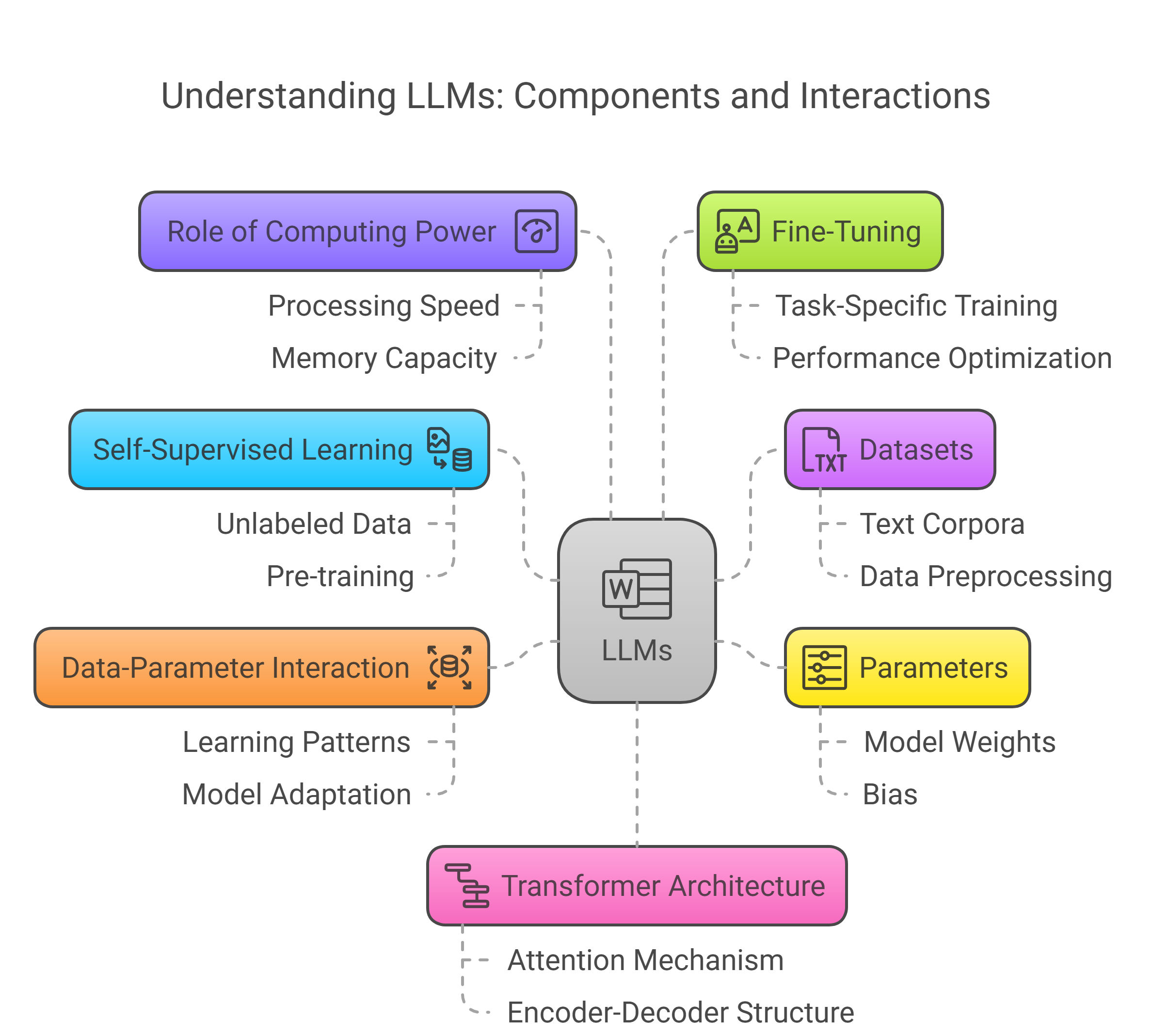

- The Architecture Solution: Split processing across multiple specialized models and agents: foundational models for intent understanding, specialized small language models for specific domains (catalog, semantics, logistics), and microagents that handle distinct tasks.

- Context Management: Use semantic understanding, product relationship modeling, and hierarchical data organization to provide models with exactly the context they need without overwhelming them with irrelevant information.

- Integration Standards: Leverage protocol standards like Open AI's Model Context Protocol (MCP) and Google's Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) to connect agents to external systems reliably.

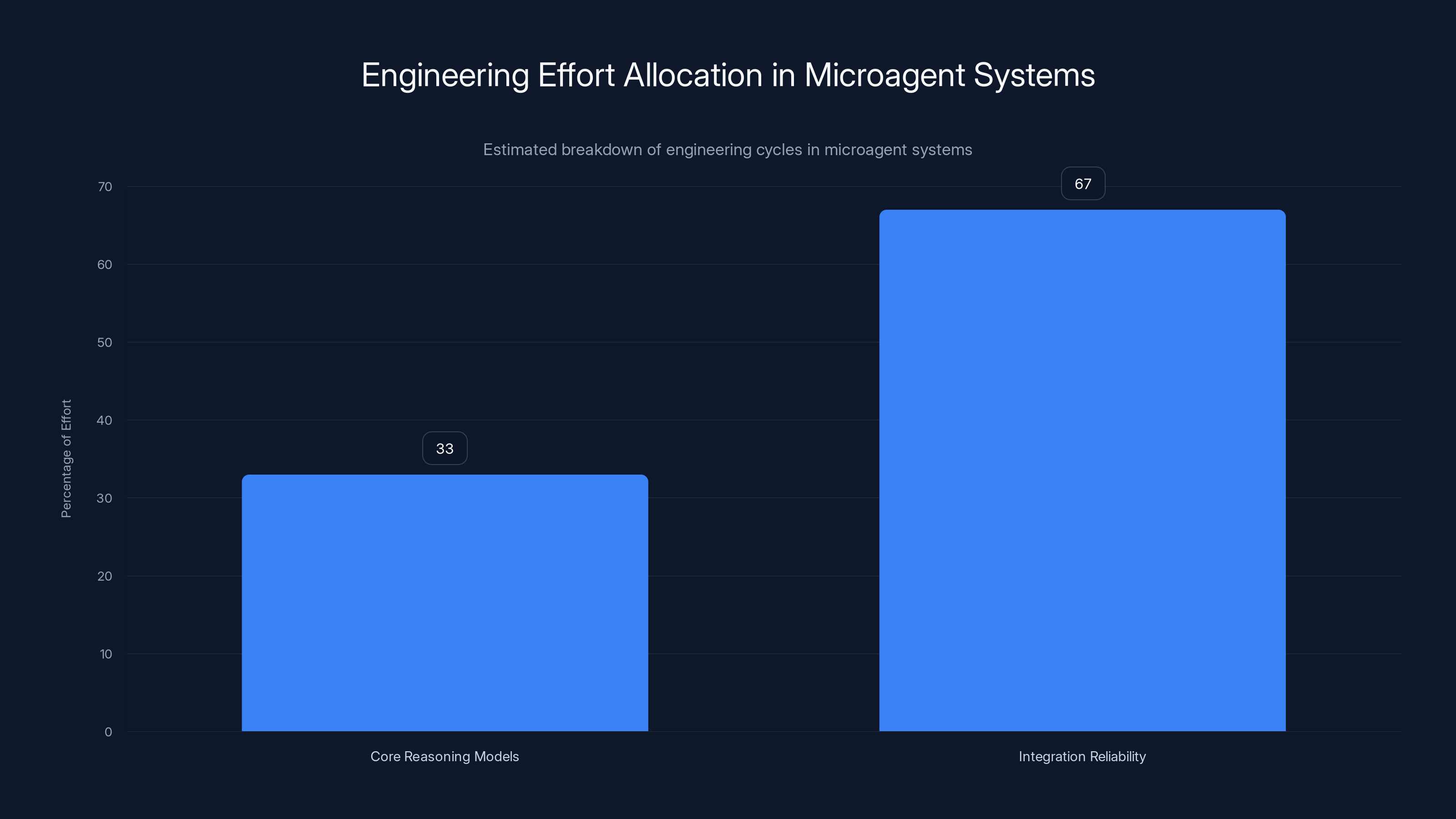

- Real-World Cost: Companies spend roughly two-thirds of their engineering effort managing failure modes, error handling, and latency challenges in agent systems, not building the core models themselves.

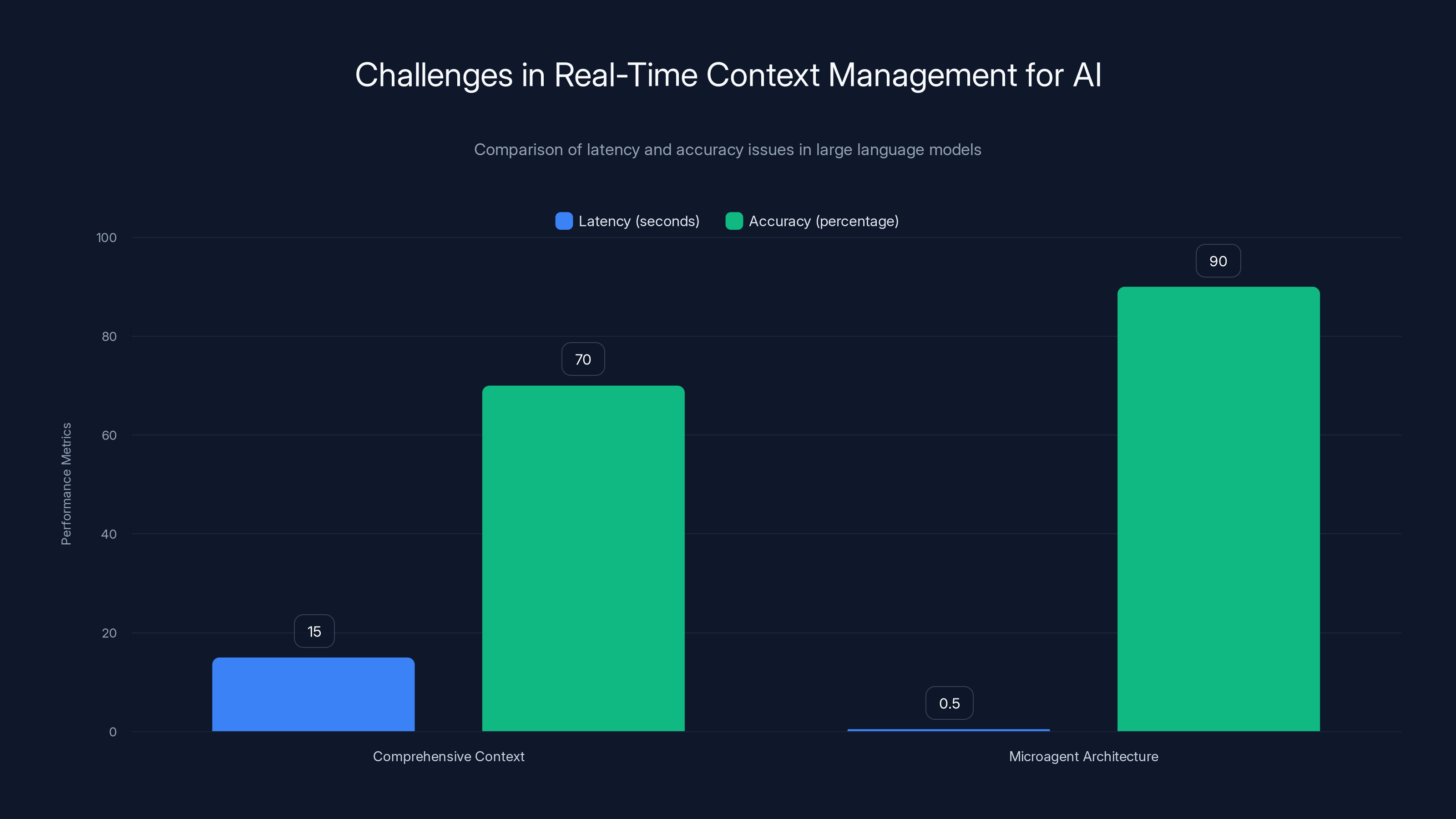

Microagent architecture significantly reduces latency from 15 seconds to 0.5 seconds and improves accuracy from 70% to 90% by focusing on specific tasks. Estimated data.

Why Real-Time Context Matters More Than Raw Reasoning Capability

There's a common misconception about how language models work in production systems. The assumption goes like this: bigger model equals better results. Train it on more data, give it more parameters, and it'll solve harder problems.

But in real-time commerce systems, that logic breaks down completely.

Consider the math. A state-of-the-art reasoning model might take 15 seconds to solve a complex logical problem. That's genuinely impressive if you're running a batch job at night or analyzing quarterly reports. But if every user interaction in your system takes 15 seconds, you've already lost 90% of your users before they even see results.

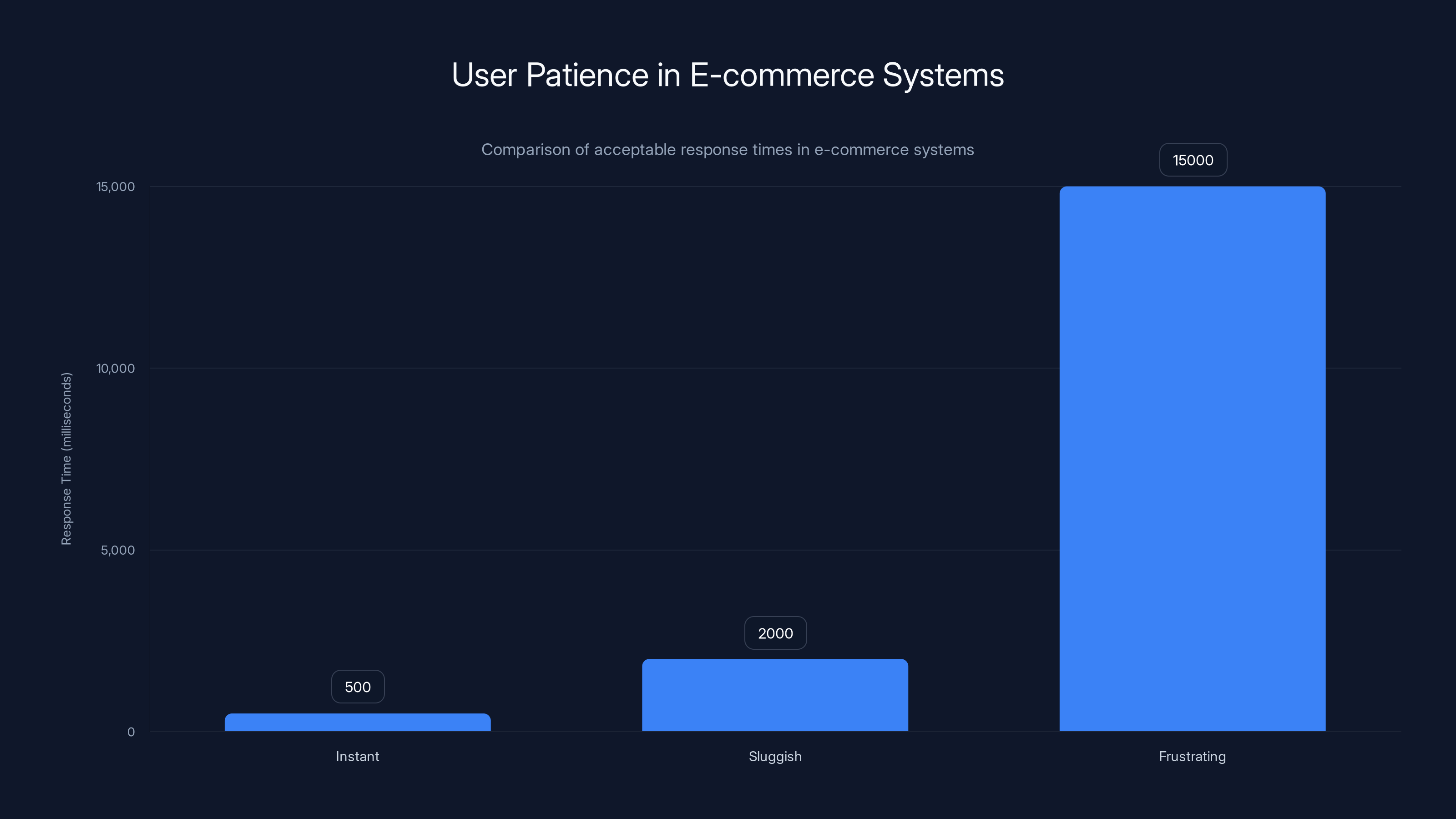

This is the latency ceiling. Most e-commerce systems operate with a mental model where a response needs to arrive in under 500 milliseconds to feel "instant" to a human. Anything between 500ms and 2 seconds starts to feel sluggish. Beyond that, users get frustrated and leave.

So if your system is constrained to 500ms total, and the model itself needs 15 seconds to reason through a problem, you're already 30 times over budget before you've done anything else.

The actual challenge, then, isn't primarily about raw reasoning ability. It's about what context the model needs to make decisions at speed. And that context needs to be precise, current, and relevant.

When a customer searches for brownie ingredients, the model doesn't need to reason about the entire history of baking. It doesn't need to understand every possible ingredient combination. It needs to understand three specific things, and it needs to understand them deeply:

- What ingredients actually go together to make brownies (semantic knowledge)

- What's available in this customer's store right now (real-time inventory)

- Whether those items will arrive fresh given delivery speed (logistics)

Loading all that context into a single large model doesn't work because you'd need to load inventory data for every product in every store, merged with customer preference history, merged with logistics constraints. The model would become massive, slow, and brittle.

So the question becomes: How do you give each part of your system the context it needs without forcing one model to hold everything?

The Architecture: Why Monolithic Agents Fail at Scale

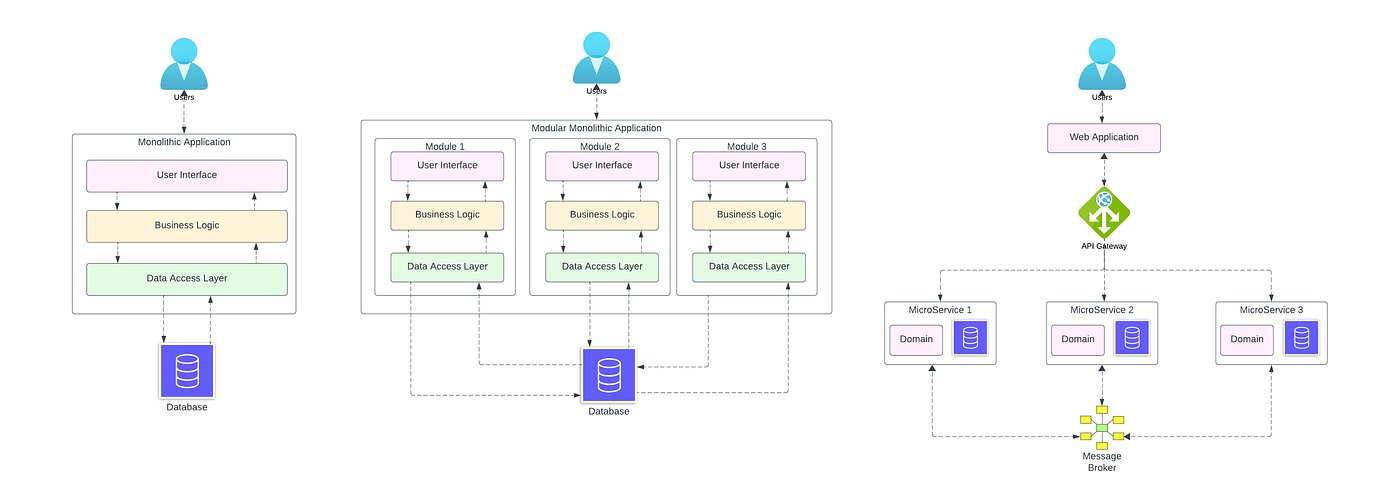

When companies first started experimenting with AI agents, many took a "monolithic" approach. Build one big agent that can handle everything. Give it access to all the tools, all the databases, all the APIs. Let it orchestrate the entire workflow.

It seems logical. Unified decision-making. One place to change things. A single agent "understands" the full context.

In practice, it's a disaster.

Monolithic agents become brittle almost immediately. One failing API call upstream breaks the entire chain. One unexpected response format causes the whole thing to crash. Debugging becomes impossible because you don't know which part of the agent is responsible for which failure. And adding new capabilities requires changing the core agent, which risks breaking everything else.

More importantly, a single agent trying to do multiple different tasks is inefficient. Routing payment to a payment processor requires different logic than checking inventory. Checking inventory requires different logic than calculating delivery times. A monolithic agent has to handle all of it, which means it's doing extra work at every step that's irrelevant to the actual task.

Instead of monolithic agents, the companies solving this problem are moving toward what they call microagent architecture. Think of it like the Unix philosophy applied to AI.

In Unix, you have small, focused programs that do one thing well. grep searches text. sed transforms text. awk processes data. These programs chain together through pipes. Each program is simple, focused, and doesn't need to understand the overall system. The power comes from composition.

Microagent architecture works the same way. Instead of one agent handling payments, inventory, logistics, and customer communication, you have separate microagents for each of those domains. Each agent is specialized. Each understands the specific APIs and data structures it needs to work with. Each has clear success and failure modes.

When a payment processor fails, only the payment microagent needs to handle that failure mode. When inventory needs to be checked, the inventory microagent handles it with all its specialized knowledge about how to parse stock data and find alternatives. When logistics calculations happen, the logistics microagent runs that specific protocol.

This architecture has real benefits. First, it's resilient. A failure in one microagent doesn't cascade through the entire system. Second, it's debuggable. When something goes wrong, you know which agent to look at. Third, it's scalable. You can add new capabilities by adding new microagents without touching existing ones.

But there's a catch. Microagent systems need coordination. They need standards for how they communicate with each other. They need protocols for how they connect to external systems. They need orchestration to manage the workflow.

In e-commerce systems, responses need to be under 500ms to feel instant. Delays beyond 2 seconds can frustrate users, while 15-second responses are unacceptable. Estimated data based on typical user experience thresholds.

The Three Domains: Intent, Catalog, and Logistics

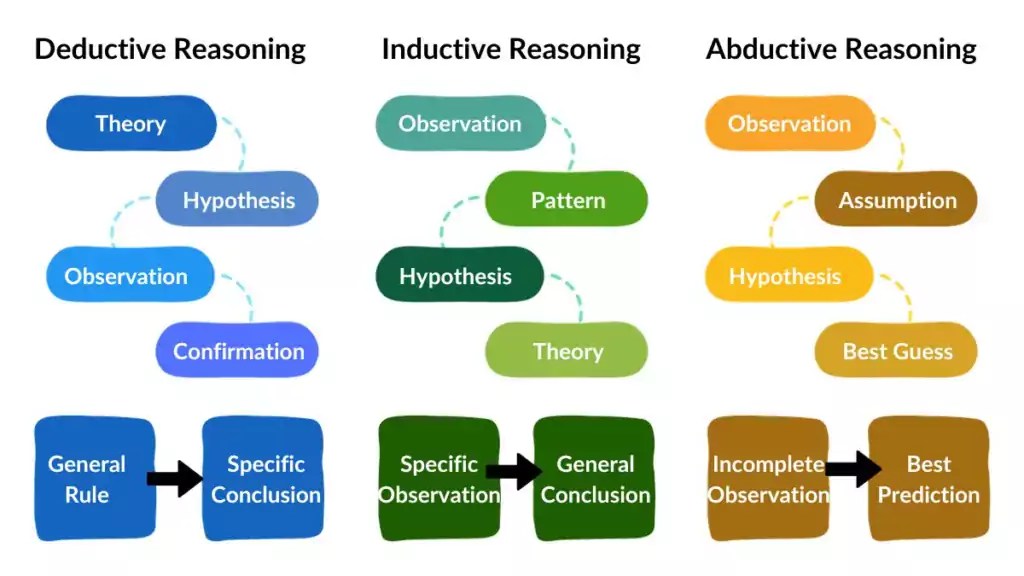

In a real-time grocery delivery system, the brownie recipe problem splits into three distinct domains, each with different context requirements.

Domain One: Intent Understanding

The customer says they want to "make brownies for a birthday party tomorrow." The system needs to understand that this is not just a request for a brownie recipe. It's a request wrapped in time constraints (tomorrow), social context (birthday party), and implicit requirements (probably needs to feed multiple people).

Intent understanding is where large foundational models shine. These models have seen enough language to understand nuance, context, and implicit meaning. They can parse the customer's request and translate it into structured intent.

But the foundational model doesn't need to know about specific products, inventory, or logistics. Its job is to understand "what does the customer actually want?" and categorize it appropriately.

For brownies, that might mean:

- Ingredient category: "baking supplies for brownies"

- Quantity intent: "feeds 10-15 people"

- Time constraint: "delivery needed by tomorrow morning"

- Quality tier: "probably doesn't need to be organic/premium" (though the system should check customer history to confirm)

Once the foundational model has extracted this structured intent, it hands off to more specialized systems.

Domain Two: Catalog Understanding

Now the system needs to understand what brownie ingredients are, how they relate to each other, and what substitutes exist.

This is where specialized small language models (SLMs) designed for catalog context excel. These models are trained specifically on product relationships, substitution patterns, and inventory data.

A catalog SLM understands that:

- Unsweetened cocoa powder and Dutch-process cocoa powder are different things, but either works for brownies

- If the customer's preferred butter brand is out of stock, they should see coconut oil or shortening as alternatives

- An 8-ounce bag of chocolate chips has a different use case than a 12-ounce bag (melting vs. baking)

- Specialty ingredients like "Belgian dark chocolate" are premium alternatives to basic chocolate

The catalog SLM also understands relationships across products. It knows that if someone is buying brownie ingredients, they're probably going to want mixing bowls, baking pans, or serving plates. It can suggest complementary products without being annoying about it.

But more importantly, it understands what's available in this specific store. It can access the local inventory database and find brownie ingredients that are actually in stock. When something isn't available, it knows how to find semantically similar products that would work.

The catalog SLM doesn't need to reason about delivery logistics or understand the customer's entire purchase history. Its domain is products and availability. That focused scope makes it fast and accurate.

Domain Three: Logistics and Freshness

Once the system knows what products the customer wants, there's one more critical constraint: will those products actually arrive fresh?

Brownie ingredients aren't all created equal from a freshness perspective. Flour sits in a box and lasts. Eggs need to stay cool and have a ticking clock. Butter can handle room temperature for hours but not days. Milk will definitely spoil.

A logistics-focused microagent needs to understand all of this. It takes the product list from the catalog system and runs a freshness calculation.

The logic might look something like:

- If the order is arriving in 2 hours, eggs are fine

- If the order is arriving in 6 hours, milk shouldn't be included (or should be substituted with shelf-stable alternatives like milk powder)

- If it's going to be hot outside during delivery, chocolate will melt and needs special handling

- If the customer's location is in a remote area, delivery time is automatically longer, which affects which products can be included

This domain-specific reasoning is actually quite complex, but it doesn't require a massive language model. It requires specific knowledge about freshness timelines, delivery networks, and environmental factors.

A microagent focused on this domain can be smaller, faster, and more reliable than a generalist model trying to do everything.

Context Granularity: The Real Innovation

The key insight behind solving the brownie recipe problem isn't about using bigger models or fancier reasoning. It's about context granularity.

Granularity means precision. Fine-grained context means the right amount of specific information, no more and no less.

When the intent-understanding model is running, it doesn't need to know about inventory. It just needs to understand what the customer wants. The context it receives is the customer's text input and their purchase history (to understand preferences).

When the catalog model is running, it needs to know which products are available and what the customer's dietary restrictions are, but it doesn't need to know the delivery address. The context is fine-grained to exactly what's needed.

When the logistics model is running, it needs the product list, the delivery address, and the current weather, but it doesn't need the customer's full purchase history. Again, fine-grained context.

This approach has multiple benefits. First, it's fast. Each model is working with a smaller context window, so processing is quicker. Second, it's accurate. Less irrelevant noise means fewer spurious correlations and mistakes. Third, it's manageable. You're not forcing one model to hold everything in its head.

The architectural pattern looks like this:

Stage One: Foundational model receives raw customer input → Outputs: structured intent + high-level categorization

Stage Two: Catalog SLM receives structured intent + product categories → Outputs: product recommendations + availability + alternatives

Stage Three: Logistics microagent receives product list + delivery constraints → Outputs: feasibility assessment + delivery timeline

Stage Four: Fulfillment orchestration receives all outputs → Coordinates with order management, payment processing, and delivery systems

At each stage, the context that flows forward is compressed and refined. The downstream systems don't get bogged down with information they don't need.

The Data Infrastructure Problem: Where Most Effort Goes

Here's something that surprises people: building microagent systems isn't primarily hard because the AI is hard. It's hard because the data infrastructure is hard.

Let's say you've got your microagent architecture designed. You've got your intent model, your catalog SLM, your logistics agent. Everything on paper looks clean and efficient.

Now connect them to the real world.

Your inventory system is a 20-year-old database from a legacy point-of-sale provider. It updates in batches every 30 minutes. Your logistics system is an API from a third-party delivery network. It has occasional latency spikes and sometimes returns stale data. Your customer preference database is maintained by a different team in a different format. Your weather API sometimes fails during peak hours.

Suddenly, you're not building an AI system. You're building a data coordination system that happens to use AI.

This is where the real work happens. Companies often find that they spend roughly two-thirds of their engineering effort managing failure modes and coordinating between systems, not building the core reasoning models.

Why? Because systems fail in unexpected ways. The point-of-sale system goes down for 20 minutes. Your agent needs to handle that gracefully. The delivery API changes its response format. Your agent needs to parse it anyway. The weather API doesn't have data for a particular region. Your agent needs to fall back to historical patterns.

Each of these scenarios requires explicit handling. Each requires error recovery logic. Each requires fallback paths.

Companies solving this problem well are implementing several key practices:

API abstraction layers: Instead of having microagents directly hit external APIs, they use an abstraction layer that handles retries, caching, and response format normalization. If an API changes format, you only need to update the abstraction layer, not every microagent.

Data caching and staleness handling: Critical data like inventory gets cached and revalidated on a schedule. When a microagent queries inventory, it gets a cached result with a timestamp indicating when the data was last confirmed. The agent can decide if that staleness level is acceptable.

Fallback hierarchies: When primary data sources fail, there's a defined fallback sequence. If the real-time inventory API fails, fall back to the 30-minute-old batch data. If that's also not available, use historical patterns to estimate what's likely available.

Explicit failure modes: Rather than letting systems fail mysteriously, microagents are designed to understand specific failure modes and handle them explicitly. A timeout is different from a bad response format, which is different from a logically inconsistent result. Each gets handled differently.

Building these systems requires infrastructure thinking, not just AI thinking. You need observability (what's actually happening in the system?), resilience (how do we keep going when things fail?), and coordination (how do we ensure different components work together?).

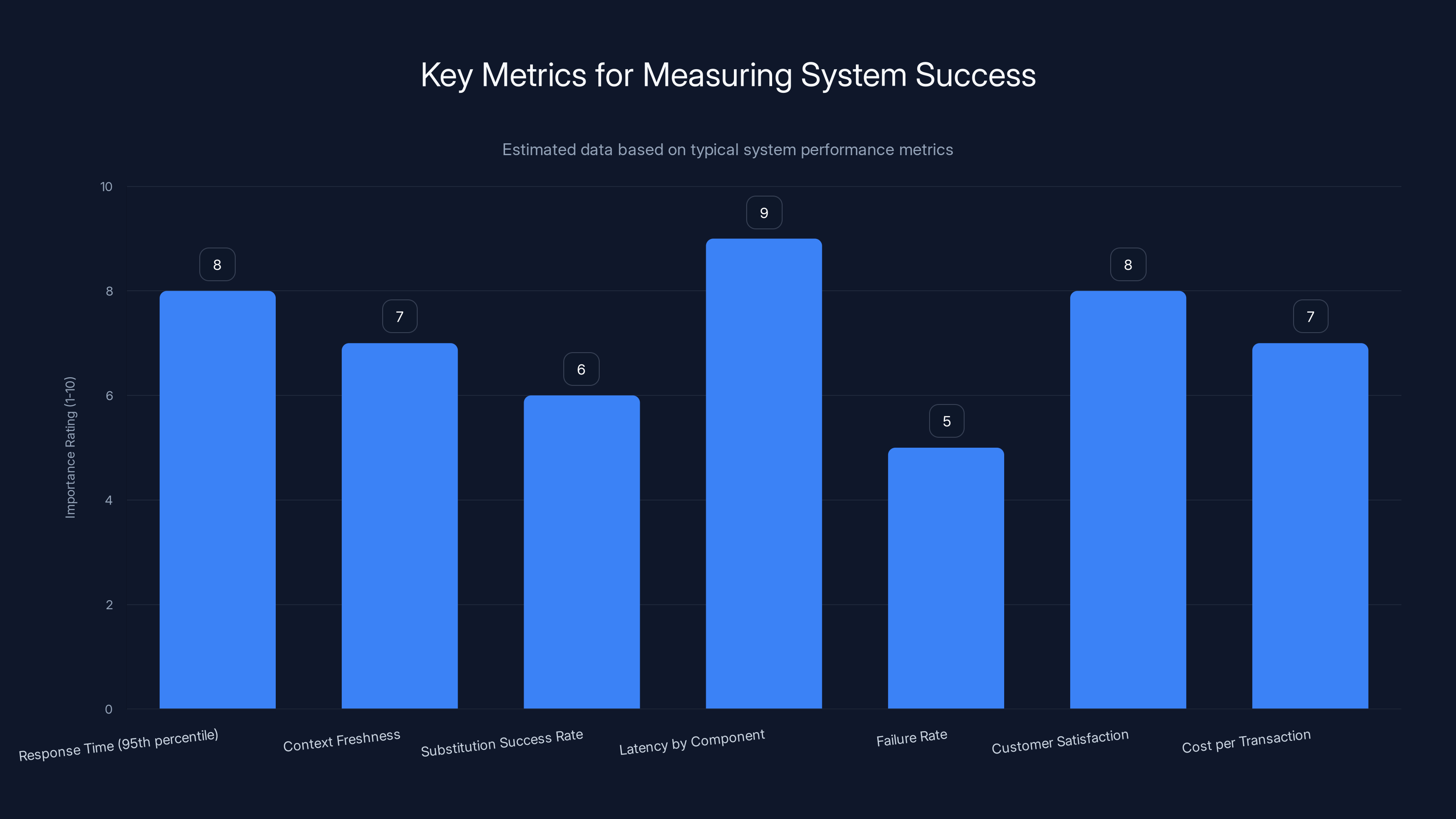

Estimated data shows that 'Latency by Component' and 'Response Time' are among the most critical metrics for system success, highlighting the importance of performance and user experience.

Protocol Standards: The Connective Tissue

For microagent systems to work at scale, they need standardized ways to connect to external tools and data sources. Otherwise, every new integration becomes a custom engineering project.

Two major protocol standards are emerging as industry solutions.

Open AI's Model Context Protocol (MCP)

MCP is designed to standardize how AI models connect to tools and data sources. Instead of each model implementation having custom code to access a specific database or API, MCP provides a uniform interface.

The protocol works by defining resources (what data sources are available), tools (what operations can be performed), and prompts (how the model is instructed to use those resources).

From the microagent perspective, MCP means you can:

- Declare what external systems you need to access

- Define what operations you need to perform on those systems

- Let the MCP layer handle the actual connection logic

- Switch between different implementations of the same system without changing agent code

For example, a catalog agent might declare that it needs to "fetch product inventory for a given category and store." Rather than hardcoding a specific database schema, it defines this operation through MCP. The actual implementation could be a direct database query, an API call to an inventory service, or a query to a data warehouse. The agent doesn't care. It just asks for inventory through MCP, and MCP handles the rest.

This creates flexibility. As your infrastructure evolves, you can swap out implementations without touching the agents.

Google's Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP)

UCP is specifically designed for commerce scenarios. It's a more specialized standard for how AI agents interact with merchant systems, inventory databases, order systems, and fulfillment infrastructure.

UCP defines standard schemas for products, orders, inventory, and fulfillment. If your microagents speak UCP, they can integrate with any merchant system that also implements UCP, without custom work for each integration.

The value here is significant. Imagine you're building a system that needs to work with multiple different grocery store chains. Each chain has its own inventory system, its own ordering API, its own fulfillment process. Without a standard, you'd need custom integration code for each one. With UCP, if both stores implement the protocol, the integration is straightforward.

The Integration Reality: Standards Aren't Magic

Both MCP and UCP are genuinely useful standards. But they're not magic. Implementation still involves real challenges.

The first challenge is that not all systems implement these standards the same way. Two different point-of-sale systems might both claim to support UCP, but their implementations differ subtly. One returns inventory as a single atomic value. Another breaks it down by location within a store. One updates in real-time. Another batches updates.

Your microagents need to handle these variations. You can't just implement UCP once and be done. You need to implement UCP-with-quirks-for-system-A and UCP-with-different-quirks-for-system-B.

The second challenge is failure modes. Standards define the happy path. They don't usually define what happens when things go wrong. What happens when the inventory service returns a timeout? What happens when it returns inconsistent data (saying 5 units are available but the product is marked as out of stock)? Each of these failure modes requires explicit handling in your microagents.

Companies report that this is where most of their effort goes. They can implement the happy path fairly quickly. But handling the failure modes, edge cases, and system quirks takes the vast majority of engineering time.

The payoff is worth it, though. Once you've handled the edge cases, your system becomes genuinely robust. It can handle real-world complexity. It doesn't break when systems behave slightly unexpectedly.

Semantic Understanding: The Often-Overlooked Layer

One of the most important but least discussed aspects of solving the brownie recipe problem is semantic understanding.

Semantic understanding means the system grasps not just words, but meaning. It understands what makes something a "healthy snack" and what appeals to an 8-year-old. It understands the difference between "organic" as a marketing term and "organic" as a certification standard. It understands that "dairy-free" might be a preference, a requirement for lactose intolerance, or an ethical stance, and each might have different implications for product substitution.

This layer sits between intent understanding and catalog matching. Once you know the customer wants "healthy snacks for kids," you need to understand what that actually means before you can match it to specific products.

For microagent systems, semantic understanding often lives in a specialized model trained on domain-specific knowledge. In the grocery context, it might be trained on nutritional databases, customer reviews mentioning health benefits, ingredient analysis, and expert categorizations.

The semantic model's job is to transform high-level intent into specific criteria. "Healthy snacks for kids" becomes something like:

- Snacks with less than 5g of added sugar per serving

- No artificial colors or flavors

- Appropriate calorie range for a child's serving size

- Commonly considered appealing to the target age group

Once you've got those specific criteria, matching to actual products becomes much more tractable. You're not trying to reason about what "healthy" means. You've already got a precise definition.

The semantic understanding layer is where a lot of the system's accuracy actually lives. Get this wrong, and you're serving unhealthy junk food to customers who explicitly asked for healthy options. Get it right, and customers feel understood. You've picked products that genuinely match their intent.

An estimated two-thirds of engineering cycles in microagent systems are dedicated to integration reliability rather than building core reasoning models.

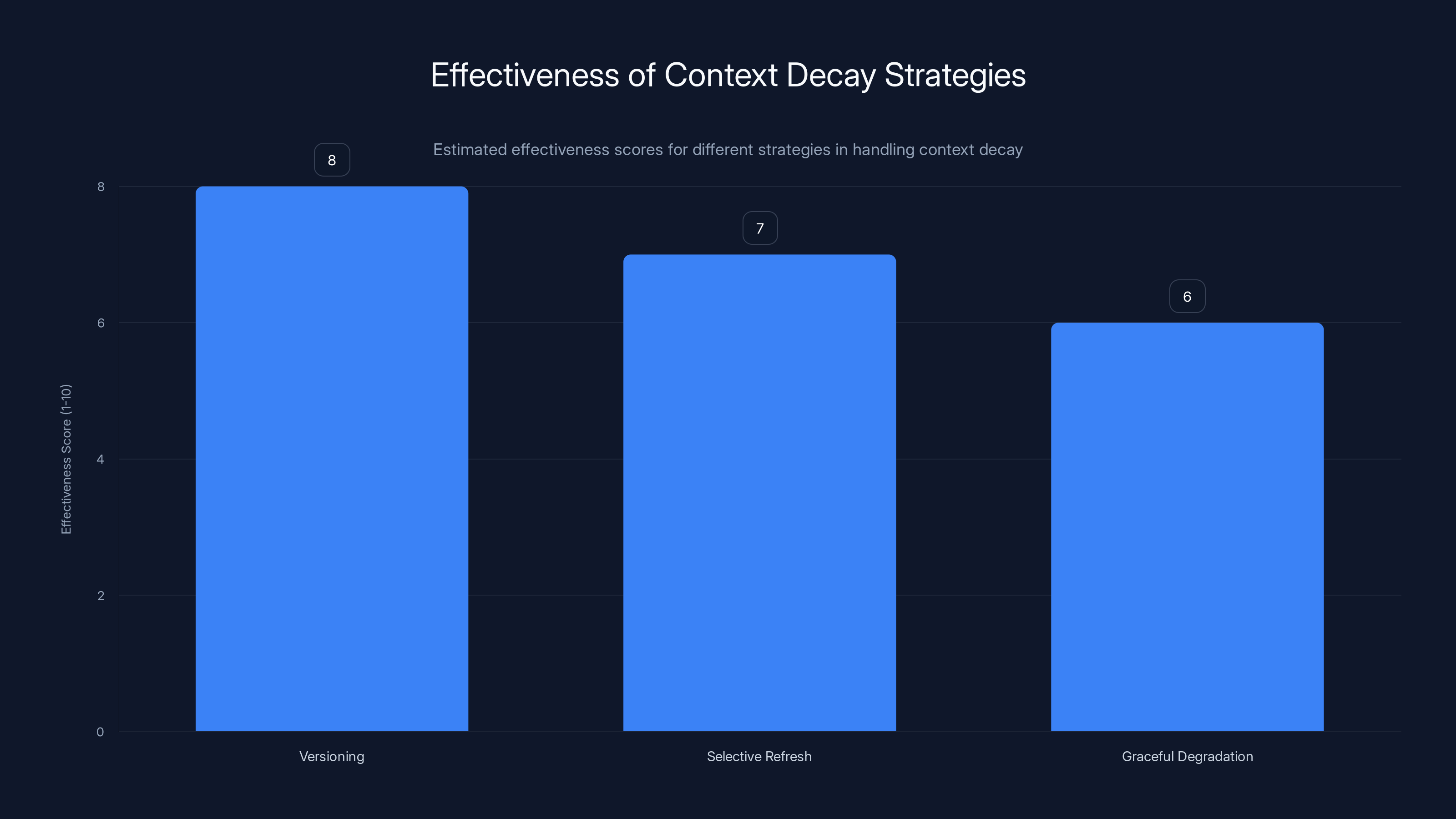

Context Decay: Why Timing Matters

One more critical insight that often gets overlooked: context has a shelf life.

Inventory data gets stale. The product you showed to a customer 30 seconds ago might be out of stock now. Customer preferences change. Their budget constraints might be different today than they were last week. Weather changes. Temperature predictions shift throughout the day.

Microagent systems need explicit strategies for handling context decay.

One approach is versioning. Every piece of context carries a timestamp. When a microagent uses context, it can check the timestamp and decide if the context is fresh enough for this decision. If inventory data is 5 minutes old but delivery takes 2 hours, that's fine. If it's 30 minutes old but delivery takes 15 minutes, that might be too stale.

Another approach is selective refresh. Rather than refreshing all context at once (which would be slow), you refresh only the critical pieces. Before confirming an order, you do a fresh inventory check on the products the customer actually selected. You don't refresh inventory on unrelated products.

A third approach is graceful degradation. When context is too stale to rely on, the system either:

- Refreshes the context (slower, but more reliable)

- Uses older data but marks it as low-confidence (faster, but less reliable)

- Avoids decisions that depend on that context (safest, but more limiting)

Which approach you choose depends on the cost of being wrong. For inventory in a grocery system, being wrong is pretty bad. You promise something you can't deliver, and you lose customer trust. So you're likely to refresh context before confirming an order.

For product recommendations ("you might also like"), being wrong is lower cost. So you might use slightly stale data to keep response times fast.

Real-Time Constraints: The 500-Millisecond Budget

All of this architectural complexity exists because of one hard constraint: response time.

In a real-time grocery delivery system, the entire process from customer request to response needs to complete in under 500 milliseconds for most interactions. Why? Because that's the threshold where users perceive the system as responsive. Beyond that, they get frustrated.

Let's break down where that 500ms budget goes:

- Network latency: ~50ms for request to reach the server

- Intent parsing: ~50ms for the foundational model to process the customer's request

- Catalog lookup: ~100ms for the catalog SLM to find matching products and check availability

- Logistics calculation: ~50ms for the logistics agent to verify items can be delivered

- Response formatting: ~30ms to format the response

- Network latency: ~50ms for response to reach the client

- Buffer for spikes: ~170ms reserved for unexpected delays

That's 500ms. If any of these steps takes longer, you're over budget.

This is why all the architectural patterns we've discussed are necessary. You can't use a single large model for everything because it would take 300ms just for the model inference. You can't load massive amounts of context because parsing that context would exceed your time budget. You need specialized, focused models that can do their job quickly. You need data organized so it can be retrieved efficiently. You need parallelism wherever possible.

Companies optimize for this constraint obsessively. They measure every operation. They profile where time is spent. They optimize the slow parts. And they build in monitoring to catch when performance degrades.

If response time creeps up to 600ms, 700ms, 1000ms, users start leaving. The business impact is direct and measurable. So this isn't a theoretical constraint. It's a hard business requirement.

Customer Preference Integration: The Implicit Context

So far we've talked about explicit context: what products are available, what the customer asked for, what the delivery constraints are.

But there's another dimension: implicit context from customer history and preferences.

A customer who's bought organic produce every week for the past year probably wants organic ingredients for brownies, even if they didn't explicitly say so. A customer who's never bought gluten-free products might not need a gluten-free brownie option. A customer with a pattern of ordering high-end ingredients probably wants premium chocolate, not basic cocoa powder.

Building this into microagent systems requires careful design. You can't just load a customer's entire purchase history into every agent. That's too much context, and it makes decisions less transparent.

Instead, successful systems precompute customer preference profiles. The preference profile for a customer might look something like:

- Primary preference: organic products (strong signal)

- Secondary preferences: premium quality, local sourcing

- Dietary restrictions: none

- Price sensitivity: medium (willing to pay for quality, but not for extreme premiums)

- Delivery speed preference: 2-hour window preferred

This profile is much more compact than the full purchase history. It captures the signal without the noise. It can be quickly evaluated by any microagent that needs to understand customer preferences.

Of course, preference profiles can be wrong. They're based on historical behavior and assumptions. So successful systems also include mechanisms to correct preferences:

- If a customer frequently overrides recommendations ("no, I don't want organic"), the preference profile gets updated

- If a customer makes unusual purchases, the system notes that and temporarily deprioritizes the baseline preference

- Customers can explicitly state preferences, which take precedence over inferred preferences

This approach balances personalization (recommendations feel tailored) with simplicity (each microagent doesn't need to reason about a customer's entire history).

The 500-millisecond budget is crucial for maintaining user satisfaction in real-time systems, with significant time reserved for unexpected delays.

Failure Mode Analysis: Why 2/3 of Effort Goes Here

We mentioned earlier that companies often spend about two-thirds of their engineering effort managing failure modes. Let's look at why.

When you're designing your system in isolation, everything works perfectly. The inventory API returns data instantly. The logistics service responds correctly. All integrations behave as documented.

In production, that's not reality.

Failure Mode 1: Stale Data Inconsistency

Inventory system A says a product is in stock. Inventory system B (which is supposed to be synced) says it's out of stock. Which one is correct? This happens more often than you'd think when you have multiple systems that are supposed to be synchronized. Your microagents need explicit logic to detect and handle this.

Failure Mode 2: Latency Spikes

Normally, the catalog service responds in 50ms. Today it's taking 500ms because there's an unexpected load spike. Do you wait for it? Do you use cached data? Do you abandon this request and retry? Each decision has implications for the customer experience.

Failure Mode 3: Partial Failures

The catalog service returns results for 8 out of 10 requested products. What do you do with the 2 it didn't return? Show incomplete results to the customer? Retry the failed ones? Substitute with alternatives? Each approach has pros and cons.

Failure Mode 4: Semantic Mismatches

The logistics API says delivery is impossible because it doesn't recognize the delivery address format that the ordering system provided. The systems are using different address schemes. Do you reject the order? Do you attempt to transform the address? Do you ask the customer to clarify?

Failure Mode 5: Distributed Consistency

A customer successfully places an order. The order is saved to the order database. But then the payment processing fails. Now you have an order with no payment. Do you automatically cancel it? Do you send a follow-up asking for payment? Do you hold it in a pending state?

Each of these failure modes requires explicit handling. And they're just a small sample. In a real system with dozens of integrations, hundreds of failure modes are possible.

Successful companies handle this by:

-

Mapping failure modes explicitly: When you design each microagent, you enumerate what could go wrong and how to handle it.

-

Testing failure modes: You don't just test the happy path. You test what happens when each service fails in various ways.

-

Instrumenting heavily: You add logging and monitoring everywhere so you can see when failures are happening and debug them.

-

Building circuit breakers: When a service is failing repeatedly, you stop trying to use it and fall back to alternatives.

-

Maintaining fallback data: You keep cache of recent successful responses so you can fall back to those when services fail.

This is where the engineering effort actually goes. Not on building clever AI, but on making systems reliable when the real world is messy.

Measuring Success: Metrics That Matter

Once you've built a system to solve the brownie recipe problem, how do you know if it's working?

You need the right metrics. The obvious ones (accuracy of recommendations, freshness of data, availability of services) matter, but they're not the whole story.

Response Time Percentiles: Not average response time, but percentiles. What's the response time for the 95th percentile of requests? The 99th percentile? These tell you how your system behaves under stress and for your worst-case users.

Context Freshness: For data-dependent decisions, how old is the context being used? What's the distribution of context staleness across all decisions? You want to know if you're typically using fresh data or old data.

Substitution Success Rate: When a customer's requested product is unavailable, how often does the substitute work out? Did they actually use the substitute? Did they like it? This measures whether your semantic understanding is good.

Latency by Component: How much time does each microagent take? Intent understanding, catalog lookup, logistics calculation. You can't optimize what you don't measure. These metrics tell you where the bottlenecks are.

Failure Rate and Recovery: How often do failures occur? How quickly does the system recover? If you have 100 orders a minute and 0.5% fail due to system issues, that's 30 failed orders per hour. That matters.

Customer Satisfaction Correlation: Do customers who receive recommendations based on fresh data and semantic understanding rate their experience higher than those who receive generic recommendations? This connects the technical metrics to business outcomes.

Cost per Transaction: How much compute and infrastructure does each transaction consume? If you're spending too much on computation, the business model breaks even if the recommendations are perfect.

Companies track these metrics obsessively. They set targets (response time under 500ms, 99th percentile; freshness within 5 minutes; substitution success above 80%). They set up alerts when metrics degrade. They do post-mortems on incidents that violate these targets.

Because ultimately, this isn't about AI. It's about building systems that work reliably in the real world, deliver value to users, and do so efficiently.

The Evolution: Where This Is Heading

The brownie recipe problem is still being solved largely through handcrafted architectures. Engineers design the microagent structure, define the integrations, build the failure mode handling.

But there's a clear trajectory toward more automation.

Self-Optimizing Architectures: Rather than engineers deciding how to split context and which models to use for which tasks, systems will increasingly optimize these decisions based on performance metrics. A system might notice that intent parsing is becoming a bottleneck and automatically split that model into two specialized models. It might notice that the catalog model is making mistakes on certain product categories and spin up a specialized model for those.

Automatic Failure Mode Detection: Systems will detect failure modes through observability and automatically generate handling logic. If they notice that a particular service fails in a certain way every few hours, they'll generate a circuit breaker for it automatically.

Context Optimization: Rather than engineers deciding what context each microagent needs, systems will measure what context actually matters for decisions and optimize context flow based on that. If they notice that including customer purchase history doesn't actually improve recommendations for a certain product category, they'll stop including it for that category, saving latency.

Distributed Learning: Multiple organizations solving similar problems (different grocery chains, different e-commerce platforms) will share learnings about what microagent structures work well, what failure modes are common, what context patterns are effective. This will accelerate how quickly new systems converge on good solutions.

Estimated data shows versioning as the most effective strategy for handling context decay, followed by selective refresh and graceful degradation.

Practical Implications for Your Systems

If you're building any real-time system that needs to understand context and make decisions quickly, the brownie recipe problem is relevant to you.

For E-Commerce: If you're building recommendation systems, personalization engines, or customer service systems, the latency and context constraints are real. You can't load the entire product catalog and customer history into your decision-making model. You need microagents, semantic understanding, and fine-grained context.

For Financial Services: If you're building trading systems, fraud detection systems, or lending decision engines, you have similar constraints. Real-time decisions require fast processing, which requires focused models and carefully managed context.

For Healthcare: If you're building clinical decision support systems or patient triage systems, you need to understand context (patient history, current symptoms, available treatments) without overwhelming the model with irrelevant information. The same architectural patterns apply.

For Io T and Edge Systems: If you're processing sensor data and making local decisions on edge devices, you have even tighter constraints. You need extremely efficient context management because compute is limited.

The core insights are consistent across all these domains:

-

Context matters more than raw model capability: A smaller model with the right context will outperform a larger model with irrelevant context.

-

Latency constraints force architectural choices: If you need sub-second responses, you can't use approaches that take 15 seconds, no matter how clever.

-

Fine-grained context is more valuable than comprehensive context: Giving each component exactly what it needs beats giving everything to everything.

-

Microagents are more maintainable than monoliths: Specialized, focused agents are easier to debug, scale, and improve than all-in-one agents.

-

Integration reliability is where the engineering effort goes: Building good AI is one part of the problem. Making integrations reliable in the face of real-world chaos is the bulk of the work.

Building Your First Microagent System

If you're thinking about implementing a microagent architecture for the first time, here's a practical approach.

Step 1: Identify Your Domains

Look at your problem and identify the distinct domains that need to be solved. Like in the grocery example (intent, catalog, logistics), what are the natural boundaries in your problem?

Don't overthink this. Three to five domains is typical. If you identify more than that, you're probably over-engineering.

Step 2: Define Interfaces

For each domain, define what context it needs as input and what it produces as output. Write down the data structure for these.

This is critical. These interfaces are how your domains talk to each other. If the interfaces are well-defined, everything else is easier.

Step 3: Prototype Each Domain

Start with a simple implementation for each domain. Don't worry about optimization yet. Just get something that works.

You might hand-code domain 1 (simple logic). You might use a simple model for domain 2. You might use heuristics for domain 3.

The goal is to understand each domain well enough to know what good looks like.

Step 4: Measure Performance

Once you have a working prototype, measure performance. What's the latency for each domain? What's the accuracy of each domain's decisions? Where are the bottlenecks?

This measurement becomes your baseline. You'll compare future improvements against this baseline.

Step 5: Optimize Iteratively

Pick the slowest domain. Make it faster. Measure the impact. If it helped, move on to the next slowest domain.

If it didn't help (maybe the bottleneck was elsewhere), try something different.

This iterative approach prevents you from optimizing the wrong things.

Step 6: Build Failure Mode Handling

Once the system is working reasonably well, start adding failure mode handling. What happens when domain 1 times out? What happens when domain 2 returns bad data?

Add explicit handling for each failure mode. Add monitoring to detect when failures happen.

This is where you stop building a proof-of-concept and start building a production system.

Step 7: Test Under Stress

Run your system under load. See if response times stay under your target. See if failures cascade or are contained.

This reveals architectural weaknesses that don't show up in normal load.

Address the most critical weaknesses. Don't try to fix everything. Prioritize based on impact to users.

The Competitive Advantage

Why does solving the brownie recipe problem matter? Because the companies that get this right build better systems.

Better systems mean better user experience (faster responses, more accurate recommendations). They mean better business metrics (higher conversion rates, lower customer acquisition costs). They mean better operational efficiency (lower compute costs, fewer incidents).

The competitive advantage isn't in any single piece. It's in the integration. Companies that understand how to architect for real-time context, how to manage latency constraints, how to build reliable integrations, how to measure what matters—these companies outcompete those that don't.

And the brownie recipe problem is just the start. As AI systems become more sophisticated, these architectural challenges only get more important. The companies solving them now are building the foundations that will support much more complex AI applications in the future.

Conclusion: Context Is Everything

When you ask an AI for a brownie recipe, it's simple. When that AI needs to orchestrate a real-time delivery system while understanding context, managing latency, and handling failure, it becomes genuinely complex.

The brownie recipe problem isn't actually about brownies. It's about the gap between what language models can do (understand language, reason about complex topics) and what production systems need them to do (make fast decisions based on current context while handling real-world complications).

The solution isn't a bigger model or a fancier algorithm. It's better architecture. Splitting the problem into specialized domains. Giving each domain exactly the context it needs. Building reliable integrations that work when things go wrong. Measuring what matters and optimizing based on data.

This is the work that actually moves the needle. Not in research papers, but in products people use every day.

The companies that master this—that understand how to balance latency, context, accuracy, and reliability—are the ones building the AI systems that actually work in the real world.

And that's where the real innovation is happening right now.

FAQ

What is the brownie recipe problem in AI systems?

The brownie recipe problem refers to the challenge of providing large language models with sufficient fine-grained context to make real-time decisions while maintaining acceptable system latency. It's named for the seemingly simple task of an AI recommending brownie ingredients, which actually requires understanding what's available in a customer's local store, their preferences, dietary needs, and whether products will remain fresh during delivery. The problem illustrates why naive approaches of loading all context into a single model fail in production systems.

Why do large language models struggle with real-time context management?

Large language models struggle with context management because loading comprehensive context (full product catalogs, customer histories, inventory across all stores, logistics constraints) into a single model creates exponential increases in latency and computational requirements. A model that takes 15 seconds to reason through a complex problem is 30 times slower than the 500-millisecond budget that real-time systems typically require. Additionally, irrelevant context actually decreases model accuracy by introducing noise and spurious correlations. The solution requires architectural changes, not just model improvements.

What is a microagent architecture and how does it solve context problems?

A microagent architecture breaks a complex problem into specialized, focused agents, each handling a specific domain (intent understanding, catalog matching, logistics, etc.). Rather than one monolithic agent trying to do everything, each microagent receives precisely the context it needs for its specific task. This approach improves latency (smaller context windows), improves accuracy (less noise), and improves maintainability (failures are isolated). The Unix philosophy of small, focused tools that compose together provides the design pattern.

What role do specialized small language models (SLMs) play in solving the brownie recipe problem?

Small language models trained on domain-specific data (catalog relationships, product substitutions, semantic categories) handle specific aspects of the decision-making process more efficiently than large foundational models. They understand product relationships, availability patterns, and semantic meaning within their domain while requiring less computational resources. In a grocery delivery system, a catalog SLM understands which products work together, what substitutes exist, and product relationships, while being much faster than a general-purpose model trying to reason about everything.

How do companies manage the two-thirds of effort spent on failure mode handling?

Companies manage failure modes through systematic approaches including API abstraction layers that normalize responses and handle retries, explicit circuit breakers that stop using services that are failing repeatedly, comprehensive monitoring and instrumentation to detect failures early, careful fallback hierarchies that define what happens when services fail, and thorough testing of not just happy paths but various failure scenarios. The key insight is that failure modes are inevitable in complex systems, so they must be anticipated, tested, and handled explicitly rather than hoped they won't occur.

What are the key differences between Open AI's Model Context Protocol (MCP) and Google's Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP)?

MCP is a general-purpose standard for how AI models connect to tools and data sources, defining resources, tools, and prompts in a uniform way. UCP is specifically designed for commerce scenarios, defining standard schemas for products, orders, inventory, and fulfillment. MCP provides flexibility across domains; UCP provides deeper specialization for commerce problems. Both address the same fundamental challenge: standardizing integrations so organizations don't need to build custom code for each system connection.

Why is context granularity more important than context comprehensiveness?

Context granularity (providing exactly what's needed) outperforms context comprehensiveness (providing everything possible) because smaller context windows are processed faster, fewer irrelevant details mean higher accuracy, and focused context allows specialization. A model deciding product recommendations doesn't need the customer's entire purchase history; it needs a concise preference profile. A model calculating delivery times doesn't need product descriptions; it needs freshness timelines and weather data. Fine-grained context respects these boundaries, improving both speed and accuracy while keeping systems maintainable.

How should organizations approach building their first microagent system?

Start by identifying 3-5 natural domains in your problem, define clean interfaces between domains specifying inputs and outputs, prototype each domain with simple implementations to understand what good looks like, measure performance to establish baselines, optimize the slowest components iteratively, build explicit failure mode handling with monitoring, and stress-test the system under realistic load. This approach prevents premature optimization and ensures you're building toward production-ready reliability from the start.

What metrics should be tracked for microagent system performance?

Key metrics include response time percentiles (95th, 99th percentile, not just average), context freshness distribution, substitution success rates, latency breakdown by component, failure rates and recovery times, and customer satisfaction correlated with technical metrics. Companies also track compute cost per transaction to ensure the business model is sustainable. These metrics connect technical implementation to business outcomes and reveal where optimization efforts should be focused.

How do preference profiles improve personalization while managing context constraints?

Rather than loading a customer's entire purchase history into every decision, systems precompute condensed preference profiles capturing the signal: primary preferences (organic, premium quality), secondary preferences, dietary restrictions, price sensitivity, and delivery preferences. These profiles are much more compact than full history, can be quickly evaluated by microagents, and can be continuously updated based on new behavior and explicit customer input. This approach balances personalization (tailored recommendations) with technical efficiency (manageable context size).

Quick Tips for Implementation

Did You Know

Key Takeaways

- The brownie recipe problem reveals why naive approaches of loading all context into a single LLM fail in production—latency exceeds acceptable thresholds and irrelevant context degrades accuracy

- Response time constraints (500ms budgets) force architectural decisions that favor specialized models over monolithic ones, making microagent patterns essential for real-time systems

- Fine-grained context—giving each component exactly what it needs—outperforms comprehensive context loading in both speed and accuracy, particularly for domain-specific reasoning

- Integration reliability consumes roughly two-thirds of engineering effort in production systems; companies must implement explicit failure mode handling, circuit breakers, and fallback hierarchies

- Standard protocols like MCP and UCP simplify agent-to-system connections, but implementation consistency and failure mode handling remain the critical challenges

Related Articles

- AI Agents & Access Control: Why Traditional Security Fails [2025]

- Xcode Agentic Coding: OpenAI and Anthropic Integration Guide [2025]

- Inside Moltbook: The AI-Only Social Network Where Reality Blurs [2025]

- Apple Xcode Agentic Coding: OpenAI & Anthropic Integration [2025]

- Luffu: The AI Family Health Platform Fitbit Founders Built [2025]

- Humans Infiltrating AI Bot Networks: The Moltbook Saga [2025]

![The LLM Context Problem: Why Real-Time AI Needs Fine-Grained Data [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-llm-context-problem-why-real-time-ai-needs-fine-grained-/image-1-1770233918707.png)