Introduction: A Quiet Shift in Nuclear Regulation

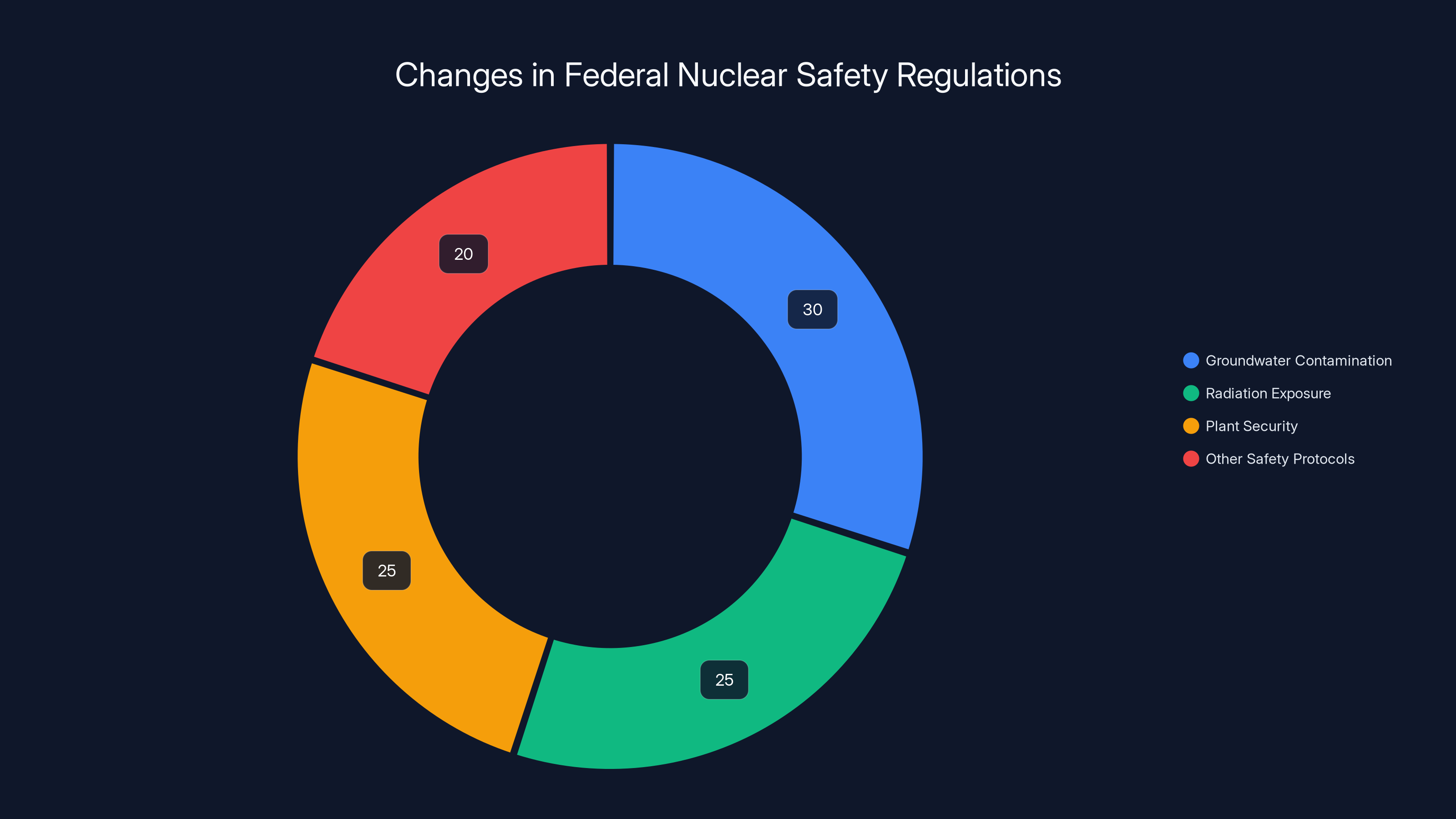

Something significant just happened in the nuclear energy sector, and most people missed it entirely. The Trump administration's Department of Energy has fundamentally restructured how it oversees nuclear safety on federal property, making changes that would've sparked congressional hearings just a decade ago. But this time? It happened quietly, without public comment, without notice to the communities that live near these facilities. According to NPR, about one-third of the federal nuclear safety rulebook has been axed. Requirements that limited groundwater contamination are now suggestions. Workers can be exposed to higher radiation doses. Plant security protocols are basically left to the company running the reactor.

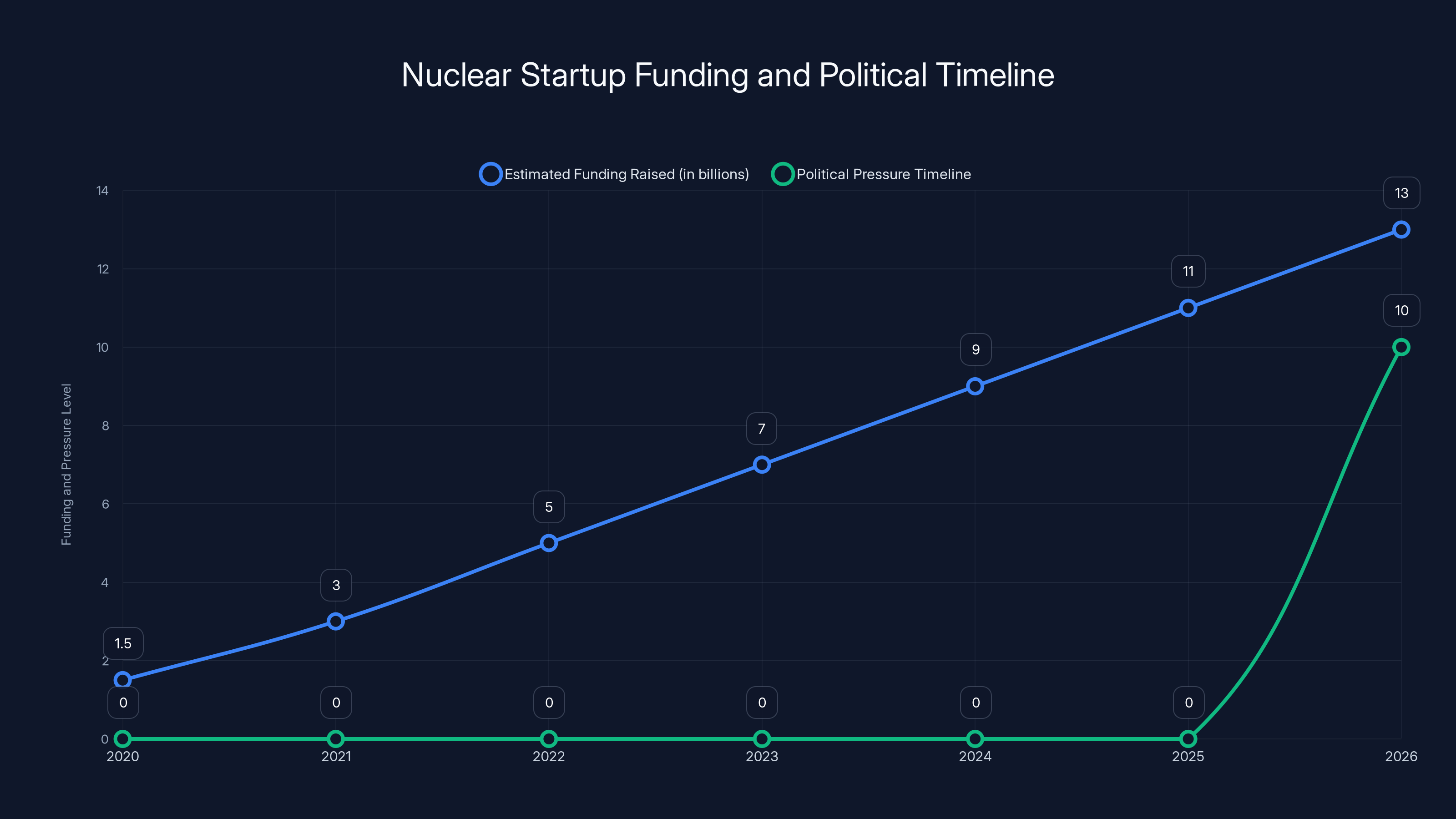

The timing isn't random. Nuclear startups are having a moment. They've raised over $1 billion in recent months, driven partly by data centers desperately hungry for reliable power. But they're also racing against a Trump administration deadline: July 4, 2026. That's the target date for demonstrating new reactor technology. And several of those demonstration reactors are being built on Department of Energy property, where these new relaxed rules apply.

This creates a fascinating tension. On one hand, you have legitimate arguments that outdated nuclear regulations slow down climate-friendly energy development. On the other hand, you have real concerns about safety shortcuts that could expose workers and communities to unnecessary risk. The nuclear industry isn't new to this balancing act, but the speed and opacity of these recent changes mark a departure from how this industry typically operates.

What makes this story complex is that nuclear energy itself isn't the villain here. Modern reactors are remarkably safe. The issue is what happens when you decouple safety oversight from the pressure to move fast and hit political timelines. This article breaks down exactly what changed, why it happened, and what it could mean for nuclear energy's future in America.

TL; DR

- Safety requirements gutted: About one-third of federal nuclear safety rules on DOE property have been removed or heavily revised without public comment

- Environmental protections downgraded: Groundwater contamination limits became voluntary suggestions rather than mandatory requirements

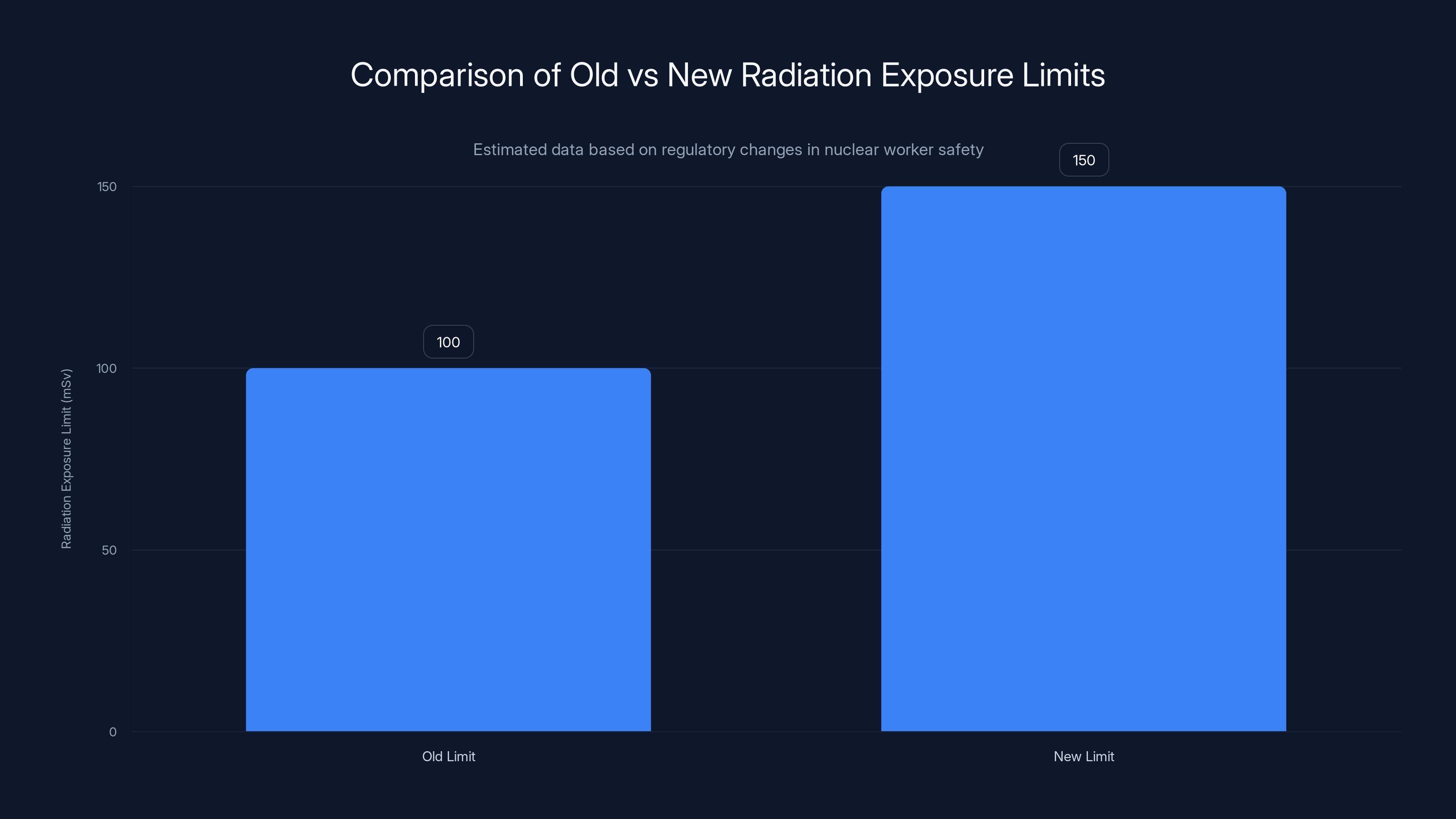

- Worker exposure increased: Radiation exposure limits for workers have been raised above previous levels

- Startup pressure: Multiple nuclear startups are developing demonstration reactors on DOE property with a July 4, 2026 deadline

- Bottom Line: The regulatory changes prioritize speed over precaution, raising questions about whether the rush to develop new nuclear technology is worth the safety risks

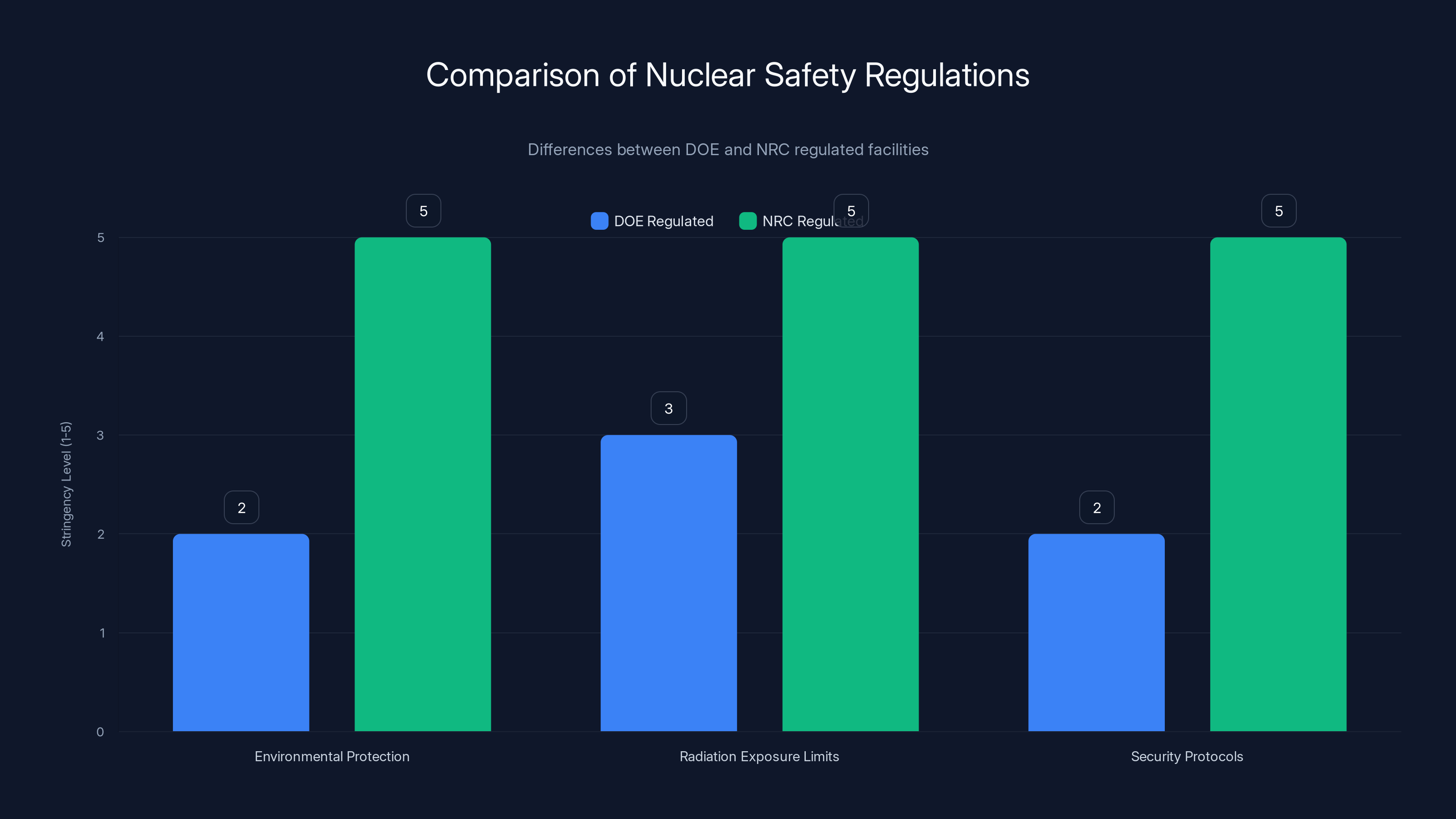

Estimated data shows that about one-third of federal nuclear safety regulations have been altered, with significant changes in groundwater contamination, radiation exposure, and plant security protocols.

The Regulatory Rollback: What Actually Changed

Let's be specific about what the Department of Energy actually did. This wasn't a single controversial rule change that made headlines. Instead, it was a methodical overhaul of multiple safety protocols, implemented without the typical federal process of public notice and comment.

The changes fall into several categories. First, there are the environmental protections. Previous rules required rigorous monitoring and limitations on groundwater contamination from nuclear facilities. Under the new framework, these aren't requirements anymore. They're guidelines. If a reactor operator decides that groundwater monitoring is unnecessarily expensive or time-consuming, they can deprioritize it. The federal government isn't stopping them.

Second, there's radiation exposure. The old rules set specific limits on how much radiation workers could absorb during their careers. These limits were based on decades of research about safe exposure levels and long-term health outcomes. The new rules increase those exposure limits. A worker who would've hit their career limit under the old framework might now be able to work years longer in the same radioactive environment.

Third, security protocols have been largely transferred to private operators. Nuclear facilities are potential targets for terrorism or sabotage. Previous rules established minimum federal standards for security: how facilities were monitored, what training security personnel needed, how threats were detected and responded to. Now much of that is up to the company running the reactor.

The process itself was unusual. Federal agencies typically publish proposed rule changes in the Federal Register, allow public comment periods (usually 30-60 days), and engage with stakeholders. This didn't happen. According to NPR's reporting, which first broke the story, these changes were developed and implemented without public notice. That's not just unusual. It's arguably legally questionable under the Administrative Procedure Act, which generally requires federal agencies to follow specific procedures when making rule changes.

The Pressure to Move Fast: Nuclear Startups and Political Timelines

Why did this happen now? Why relax safety rules specifically for reactors being built on Department of Energy property?

The answer involves a convergence of three forces: startup ambition, data center demand, and political pressure.

Nuclear startups have been on a funding tear. Companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems, TAE Technologies, X-energy, and others have collectively raised billions in recent years. These aren't theoretical research projects anymore. They're building actual reactors that are supposed to generate actual power. But they're also competing against each other and against a ticking clock.

The Trump administration set July 4, 2026 as the target date for demonstrating new reactor technology. That's an ambitious timeline, probably designed as a political victory marker rather than a realistic engineering deadline. But it's the deadline that matters, not its realism. Companies that can hit that target get favorable regulatory treatment, political support, and the ability to claim they're solving America's energy problem.

The data center angle is real too. Companies like Google, Microsoft, Meta, and countless others are building enormous data centers to run AI systems. These data centers consume staggering amounts of electricity. Traditional power grids can't always supply it. Nuclear power—especially small modular reactors that can be deployed at individual sites—looks like the obvious solution. Utilities and tech companies have been asking the federal government to clear regulatory obstacles.

Here's the political calculation: if you're the administration that gets nuclear startups to build the reactors that power American AI, you're also the administration that solved the energy problem. You're the administration that made America energy-dominant. You're the administration that freed business from regulatory burden. That's a powerful political narrative.

But that calculation doesn't include exploded budgets, construction delays, or worse, safety incidents. Those make headlines for different reasons.

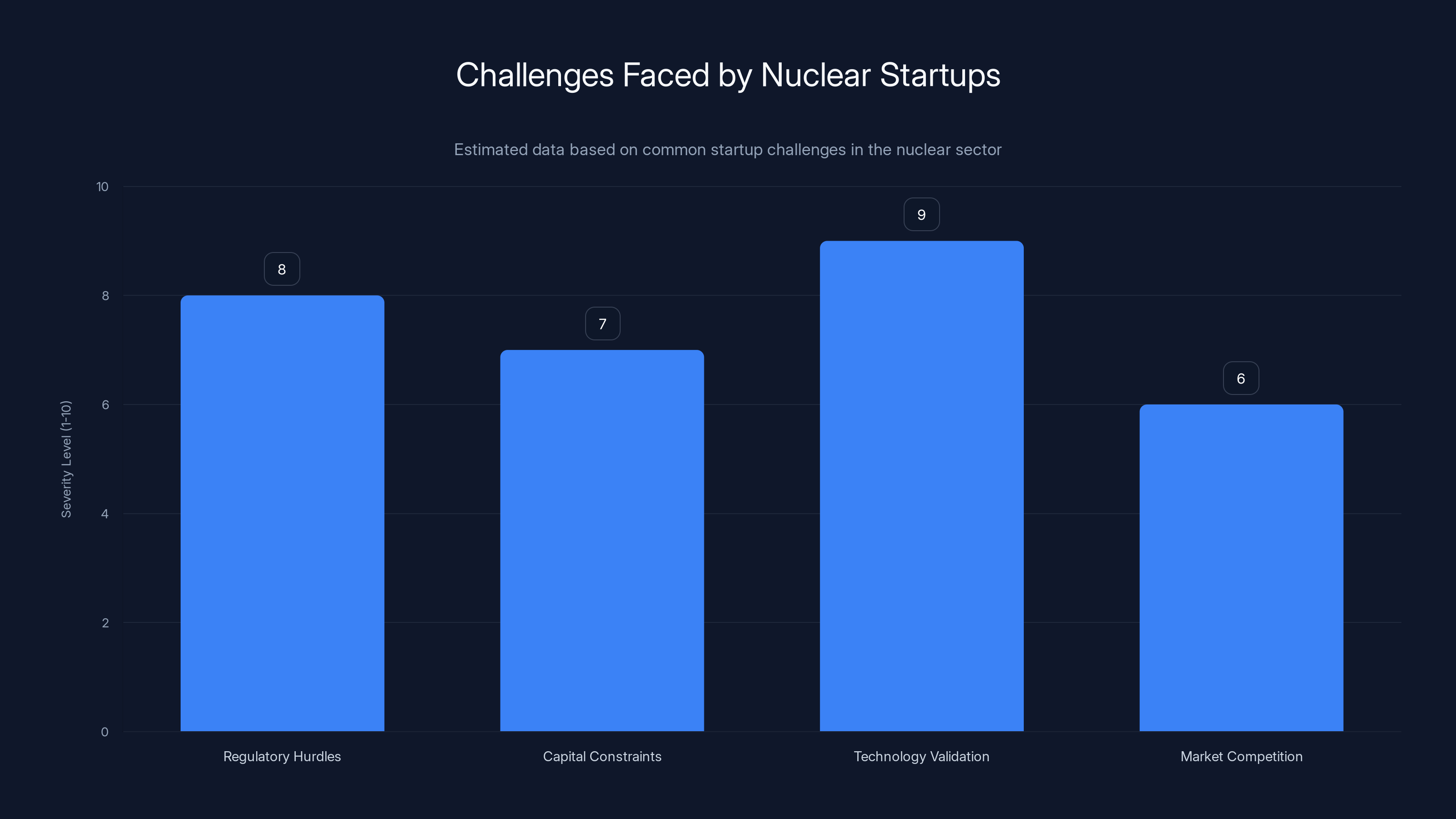

Nuclear startups face significant challenges, with technology validation and regulatory hurdles being the most severe. Estimated data.

Nuclear Startups Racing Against the Clock

Let's talk about the actual companies building these reactors. Several nuclear startups have projects underway on Department of Energy property, specifically targeting that July 2026 deadline.

These aren't fringe operations. These are well-funded companies with impressive technical teams and serious backing. Commonwealth Fusion Systems, for instance, is backed by venture capital and has partnerships with major utilities. They're building a demonstration reactor called SPARC that's supposed to show net energy gain from fusion. Winning a race to demonstrate working fusion technology would be genuinely groundbreaking—not just commercially, but scientifically.

Then there's X-energy, working on high-temperature gas reactors. TAE Technologies is pursuing different fusion approaches. Terra Power (backed by Bill Gates) is designing advanced fission reactors. These companies represent billions in total funding and genuine engineering talent.

But here's the tension: the faster you need to move, the more tempting it becomes to cut corners. When your runway is defined by a political deadline rather than engineering reality, you start asking questions like "Do we really need this safety test?" or "Can we simplify this security protocol?" Those questions have answers that get easier to justify under relaxed regulatory frameworks.

The companies themselves aren't necessarily making cynical decisions. Most of the people working at these startups genuinely believe they're building the future of clean energy. They probably do think some of the old safety rules are outdated. But when your funding, your timeline, and your company's survival are all dependent on hitting a specific deadline, your judgment about what's actually necessary becomes... compromised.

Why Safety Rules Existed in the First Place

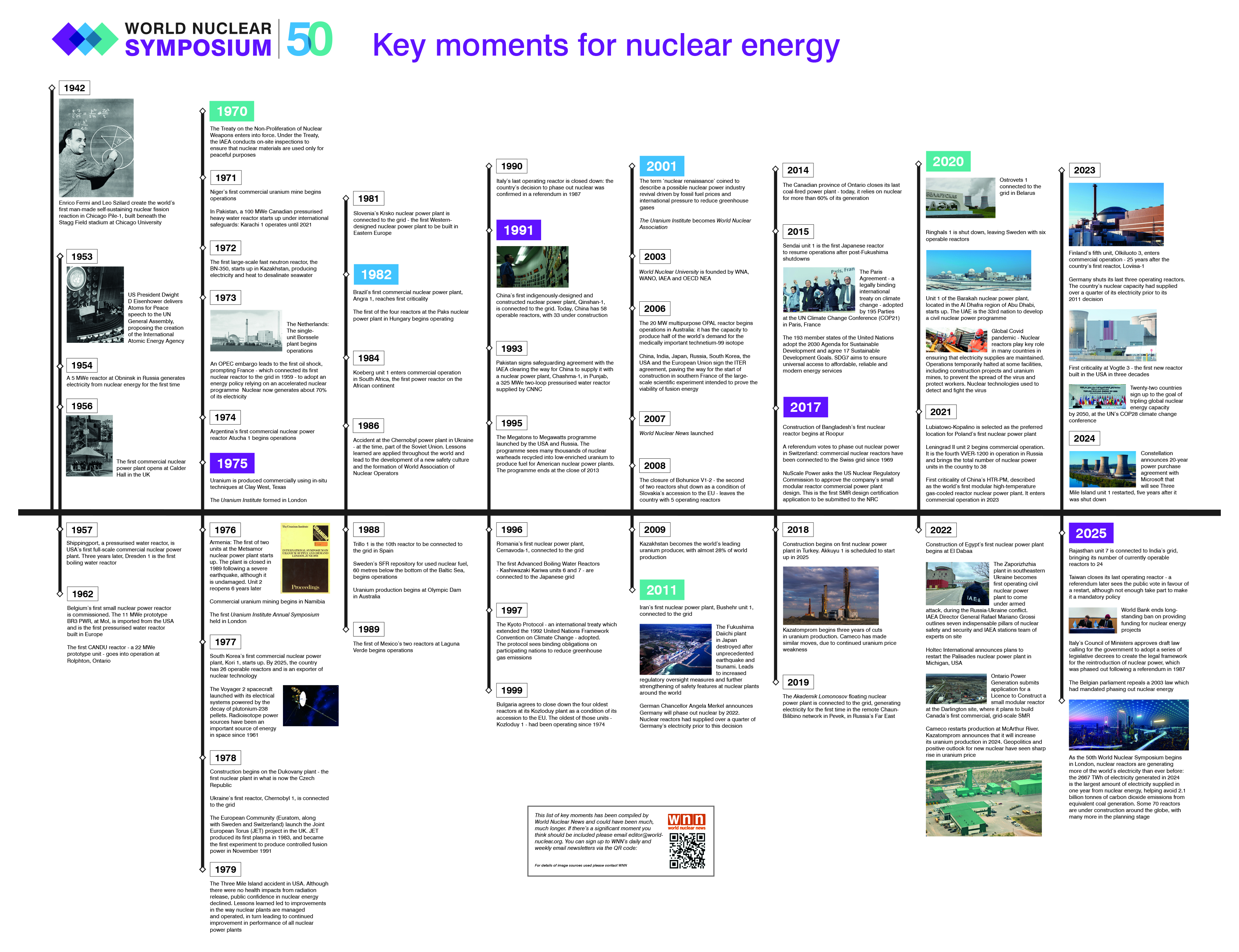

It's worth understanding the history here. Nuclear safety regulations weren't invented because bureaucrats enjoy paperwork. They were written in blood, literally. The nuclear industry's safety record is actually quite good, but the handful of times things have gone seriously wrong, they've gone very wrong.

Three Mile Island in 1979 taught lessons about redundancy and communication failures. Chernobyl in 1986 taught lessons about cost-cutting and poor design decisions. Fukushima in 2011 taught lessons about overconfidence and underestimating environmental threats. Each of these incidents informed how the world approaches nuclear safety regulation.

The specific rules being relaxed often have direct connections to these historical lessons. Groundwater monitoring requirements exist because radioactive contamination can persist for decades and harm water supplies for hundreds of thousands of people. Radiation exposure limits exist because people who worked in early nuclear industries developed cancer at elevated rates. Security protocols exist because nuclear materials are weapons-usable in the wrong hands.

Were all of these rules perfectly calibrated? Probably not. Regulations tend to accumulate over time, and some of them likely are outdated or overly conservative. There's a legitimate argument that some nuclear safety regulations impose costs without proportional safety benefits.

But that argument requires careful analysis, public discussion, and peer review. It requires health physicists and engineers and security experts and community members all having a voice. It doesn't happen through quiet rule changes made without public notice.

The specific concern is this: when you're under time pressure and you're making changes without external scrutiny, it's very easy to cut more deeply than you should. It's very easy to mistake caution for unnecessary burden.

Groundwater Contamination: Why It Matters

Let's focus on one specific category of the relaxed rules: groundwater protection.

Groundwater is how millions of Americans get their drinking water. It's also how farms irrigate crops and how industries get water for cooling and processing. Once groundwater is contaminated with radioactive material, it can remain dangerous for decades or centuries. You can't easily filter out radioactive isotopes. You can't pump the water back into the aquifer. You basically have to avoid that area.

The old rules required nuclear operators to monitor groundwater around their facilities and maintain specific limits on contamination. If a reactor operator noticed radioactive material leaching into groundwater, they had to respond. They had to figure out where it was coming from and stop it.

Under the new rules, this is voluntary. An operator can choose to monitor groundwater. They can choose to care about contamination. But if they decide it's not worth the expense, they don't have to. Federal regulators can't force them to.

In practice, this matters most for newer reactor designs and for companies with tight budgets. An established utility with decades of experience operating nuclear plants is probably going to monitor groundwater anyway. The reputational risk and the legal liability if contamination occurs is just too high.

But a startup trying to hit a deadline and manage cash burn? A startup where the founders and investors might not stick around for the long-term operation of the facility? That startup's incentive structure is completely different.

You want to think the best of people. You want to assume that companies building nuclear reactors would never knowingly contaminate groundwater. But you also have to think about incentive structures. If someone can save $10 million by skipping groundwater monitoring and nobody's going to stop them, what happens?

DOE regulated facilities have looser oversight compared to NRC regulated ones, particularly in environmental protection and security protocols. Estimated data.

Worker Radiation Exposure: The Health Implications

Nuclear plants require people to work in radioactive environments. Most modern reactors are very good at shielding workers from radiation, but some exposure is inevitable. Maintenance work, inspections, emergencies—these situations put workers at potential risk.

Radiation exposure is cumulative. Your body doesn't forget a dose received five years ago. Instead, it adds up over your lifetime. The risk of cancer, cataracts, and other radiation-related illnesses increases with total accumulated exposure.

Workers in nuclear facilities are carefully monitored. They wear dosimeters that track how much radiation they've received. And they have career limits—maximum total doses they can receive before they're not allowed to work in radioactive environments anymore.

The old limits were based on research by the International Commission on Radiological Protection and regulatory agencies in multiple countries. The limits were chosen to keep lifetime cancer risk to acceptable levels while still allowing nuclear plants to operate.

The new limits are higher. A worker could now receive more total radiation exposure in their career than they could under the old rules. The theory is probably that the new limits are still safe. That they're just less conservative.

But here's the thing: regulatory agencies typically maintain conservative limits for good reasons. There's always uncertainty in health research. There are always edge cases. A more conservative limit ensures that even people in unusual circumstances (maybe a worker has genetic predisposition to radiation sensitivity, or maybe they smoke, combining radiation exposure with another cancer risk) stay safe.

When you increase the limit, you're accepting that some of the people who hit that new limit will probably get cancer who wouldn't have under the old limit. That's not a verdict on whether they should get cancer. It's just a statistical reality of how exposure and health interact.

The question regulators are supposed to ask is: is the benefit worth that cost? Is the increased speed of building nuclear reactors worth the increased cancer risk to workers? That's a real policy question with legitimate arguments on both sides. But it's supposed to be a conscious decision made transparently, not a side effect of rushed implementation.

Security Protocols and the Insider Threat

Nuclear facilities are potentially attractive targets for terrorism, sabotage, or theft. Not because of common misconceptions about nuclear plants exploding (modern plants are extremely resistant to explosion), but because of the materials involved.

Nuclear fuel is weapons-usable material in the wrong hands. The same enriched uranium or plutonium that powers a reactor can be weaponized. The risk isn't usually that someone will steal a whole reactor. The risk is that someone inside the facility—an employee with access and motivation—could steal or divert material.

National security experts have worried about "insider threats" for decades. Someone with legitimate access to sensitive areas could theoretically pass information to hostile actors or actually move material.

Previous security protocols were designed to minimize this risk. They included things like background checks, training requirements, ongoing monitoring, and specific procedures for how materials were handled and stored.

Under the new rules, much of this becomes optional or is left to individual operators to decide. A startup building a demonstration reactor gets to decide how serious it wants to be about security.

Again, you'd like to think that every company building a nuclear reactor would take security seriously. But startups operate on limited budgets. Security infrastructure is expensive. It doesn't directly contribute to the reactor generating power. If nobody's forcing you to implement it, it's very easy to defer.

The federal government has specific authority over nuclear materials. It's supposed to ensure those materials don't end up in the wrong hands. Relaxing security protocols transfers some of that responsibility to private companies, many of which have never operated nuclear facilities before.

The Role of the Department of Energy

It's worth understanding what the Department of Energy actually does and why it has authority over these facilities in the first place.

The DOE is responsible for nuclear weapons, nuclear research, and energy policy. It owns a network of national laboratories and facilities. Some of these facilities host nuclear reactors for research and development purposes.

When a startup wants to build a demonstration reactor, they often do it on DOE property because it's available, because the DOE has infrastructure to support it, and because it simplifies some regulatory issues. The startup doesn't own the land, but they operate the reactor under an agreement with the DOE.

Traditionally, the DOE has maintained strict safety and security standards at its facilities. Even though the DOE isn't the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (the NRC, which oversees civilian nuclear reactors), the DOE takes its responsibilities seriously. Nuclear safety is a core mission.

But the DOE is also a policy agency subject to the sitting administration's priorities. When the Trump administration decided that fast-tracking nuclear development was a priority, the DOE aligned with that priority.

The question that regulators and Congress will probably wrestle with is whether the DOE overstepped its authority. The Administrative Procedure Act generally requires federal agencies to follow specific procedures when making rule changes. Secret rule changes made without public notice might violate that law. Whether they actually do is a question for the courts.

But regardless of the legal question, there's a governance question: should major changes to nuclear safety protocols happen without public input? Most people would probably say no. Nuclear safety affects people who live near facilities. Those people should probably have a voice in decisions about safety standards.

Estimated data shows that new radiation exposure limits for nuclear workers are higher than the old limits, potentially increasing health risks.

Data Centers and the Energy Imperative

To understand why these rule changes happened, you have to understand how desperate the data center industry is for reliable power.

Artificial intelligence systems require enormous amounts of computation. That computation requires enormous amounts of electricity. A single large data center can consume as much power as a small city. And these data centers are proliferating as companies race to build AI capabilities.

The problem is that the power grid isn't keeping up. Renewable energy sources like wind and solar are becoming cheaper and more common, but they're intermittent. When the sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing, you need other sources of power. And you need those sources to be reliable enough to keep trillion-dollar AI systems running 24/7.

Nuclear power is the obvious answer. It's carbon-free, it's reliable, it can run continuously at full capacity. The only problem is that traditional nuclear reactors are massive, expensive, and take a decade to build.

Small modular reactors could change that equation. The theory is that you could build smaller reactors faster and cheaper, then deploy them at individual data centers. One reactor per facility, no need to integrate with the broader grid, no need to convince skeptical communities to host a nuclear plant.

Tech companies have figured this out. Google, Microsoft, Meta, and others are actively pursuing nuclear partnerships. This creates political pressure. If America's biggest tech companies are saying they need nuclear power to build AI, then maybe the federal government should remove barriers to nuclear development.

That pressure translates to rule changes. Not through conspiracy, but through the normal operation of how policy gets made: industry wants something, industry has political influence, government changes policy to give industry what it wants.

The problem is that industry's incentives and the public's incentives aren't always aligned. Companies want nuclear plants built fast and cheap. The public wants them built safely. Those aren't necessarily contradictory goals, but they do create tension.

International Perspectives on Nuclear Safety

Other countries have dealt with similar tensions between moving fast and staying safe. Their approaches are instructive.

France, which gets the majority of its electricity from nuclear power, maintains strict safety standards. It also builds reactors, though not as quickly as the U. S. administration wants. The French approach is methodical: design carefully, build carefully, inspect constantly. It works well for long-term operation by mature utilities.

China and South Korea have focused on building newer reactor designs more quickly. They've streamlined permitting and reduced some traditional safety bureaucracy. They've also had better luck with construction timelines. But they operate in political systems with different checks and balances than the United States.

Canada has explored small modular reactors extensively. Canada's approach is to maintain safety standards while trying to reduce unnecessary bureaucracy. They haven't eliminated safety requirements, but they've tried to make approval processes faster for designs that are clearly low-risk.

What most international examples share is transparency. Even countries moving quickly on nuclear development maintain public processes for approving designs and monitoring safety. They don't make rule changes in secret.

That contrast is probably important. It's one thing to streamline approval processes for a new reactor design that's been thoroughly reviewed by experts. It's another thing to eliminate safety requirements without any external review.

The July 4, 2026 Deadline: Realistic or Political?

A lot of this story hinges on the July 4, 2026 deadline for demonstrating new reactor technology. Is it realistic? What happens if startups don't hit it?

Engineering-wise, it's extremely aggressive. Building a working nuclear reactor requires solving thousands of problems. You need to design it, engineer it, manufacture components, integrate them, test systems, debug failures, get permitting approvals, hire and train personnel, establish safety protocols. All of that normally takes a decade or more.

Completing that in the roughly 18 months remaining is theoretically possible if the design is relatively simple and if you're willing to skip or minimize normal engineering validation steps. It's theoretically possible if you have enormous resources and a motivated team. But it's not a normal engineering timeline.

Politically, the deadline makes sense. An administration wants to claim victory and demonstrate progress. July 4th is patriotic and symbolic. If a startup can demonstrate even a small reactor producing power by that date, it's a good headline: America is building the future of nuclear energy.

But what happens if startups don't hit the deadline? The administration loses a political victory. Some funding might dry up. Some regulatory attention might shift. But the reactor will still exist. It might be operational in 2027 or 2028. It will still demonstrate that the technology works.

The problem is that the deadline creates incentives to cut corners. If hitting a July 2026 date is worth billions in investor funding and regulatory favor, then there's enormous pressure to do whatever it takes to hit that date. Cutting safety corners starts looking like a reasonable trade-off.

This is why timelines matter in nuclear safety. A realistic timeline allows for careful work. An unrealistic timeline creates pressure to skip steps. And when the timeline is imposed by politics rather than engineering reality, the pressure becomes even more intense.

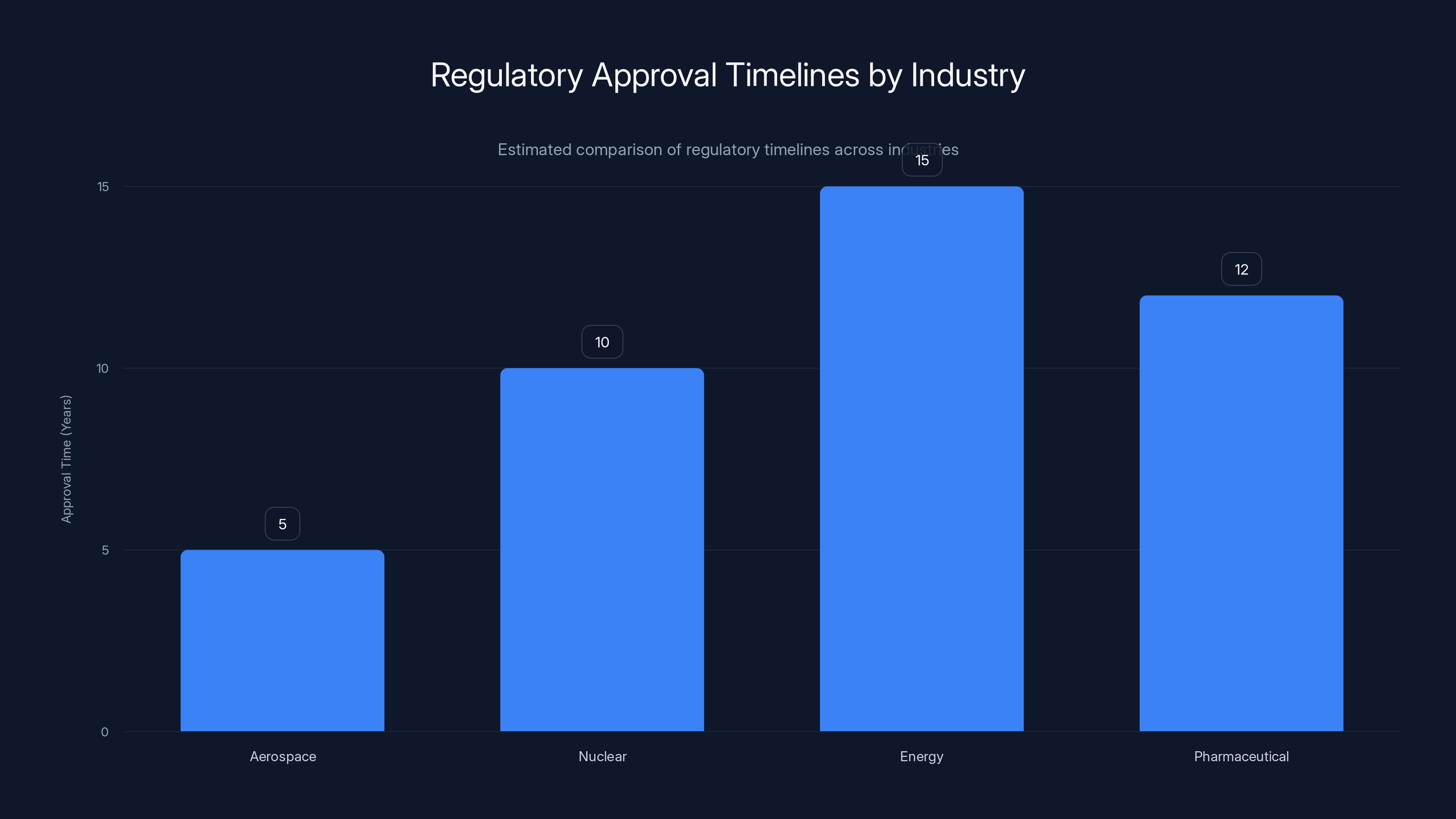

Estimated data shows aerospace industry has the shortest regulatory approval timeline, while energy and pharmaceutical industries take longer due to complex safety requirements.

The Permitting and Oversight Gaps

One consequence of these rule changes is that they create gaps in who's actually overseeing safety at these facilities.

Normally, multiple agencies have oversight: the Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversees certain aspects, the Environmental Protection Agency oversees environmental impacts, OSHA oversees worker safety, state regulators often have additional authority. It's redundant, sometimes inefficient, but the redundancy serves a purpose: mistakes by one agency might get caught by another.

When reactors are built on Department of Energy property under the old framework, the DOE had primary responsibility but still needed to coordinate with other agencies and follow federal rules. The NRC didn't have direct authority over DOE reactors, but the DOE's rules were inspired by NRC thinking and were subject to federal oversight.

Under the new rules, that oversight structure is much looser. The DOE sets the requirements (or rather, doesn't set them). The operator decides how to comply (or whether to comply). Other agencies have limited authority because they're not explicitly included in the DOE's new framework.

In theory, the DOE could still enforce safety requirements and shut down a reactor that's operating dangerously. In practice, when you've made it clear that you want the reactor built fast, and when you've relaxed the rules the operator is supposed to follow, enforcement becomes politically difficult.

This is a genuine governance failure, regardless of whether the actual safety risks materialize. Regulatory agencies are supposed to maintain oversight. When they intentionally loosen oversight to accelerate a desired outcome, they're trading governance for speed.

The Public Health Angle

Nuclear facilities affect public health in multiple ways. There's the immediate health of workers. There's the longer-term health of communities near the facility. There's the environmental health of the region.

Workers' health is straightforward: they're exposed to radiation, they're exposed to workplace hazards, they have health risks. Those health risks increase when radiation exposure limits are raised and when safety protocols are loosened.

Community health is more indirect but still real. Environmental contamination from a nuclear facility (through groundwater, air emissions, or accidents) can harm people for decades. Cancer rates in communities near nuclear facilities have been studied extensively. The results are usually reassuring, but they're most reassuring when facilities are carefully operated and monitored.

The public has a legitimate interest in these health outcomes. And the public usually becomes interested in nuclear safety only after something has gone wrong. That's why transparency and precaution are important even when accidents are rare.

When safety rules are loosened without public input, the public loses an opportunity to think about whether the health risks are acceptable. And if something does go wrong, the public has no record of having chosen to accept that risk. That's a democratic governance failure independent of any actual safety issues that might arise.

Environmental Considerations Beyond Groundwater

Groundwater contamination is one environmental concern, but there are others.

Nuclear facilities produce radioactive waste. Long-lived isotopes need to be stored safely for thousands of years. The rules about how waste is handled, stored, and transported matter. If those rules are loosened, the risk of environmental release increases.

Nuclear facilities also affect water quality beyond just groundwater. Reactors use enormous amounts of water for cooling. That water is heated and released back into rivers or other water bodies, creating thermal pollution. That affects aquatic ecosystems. Rules about how much thermal pollution is acceptable could become suggestions instead of requirements.

And there's the question of what happens if a facility is abandoned. If a startup builds a demonstration reactor and it doesn't work out economically, what happens to the facility? Who's responsible for decommissioning it safely? If rules are loosened, the answer might be: whoever can escape responsibility first.

These environmental considerations aren't separate from the safety questions. They're part of the same issue: when you loosen oversight, you increase risks to both human health and environmental health.

Funding for nuclear startups has been increasing significantly, with a political deadline set for July 4, 2026, creating pressure to demonstrate new reactor technology. Estimated data.

The Startup Perspective and Innovation Incentives

It's worth considering what these rule changes mean from the startups' perspective.

Nuclear startups are trying to build new technology. They're competing with each other and with established utilities. They have limited capital and need to move quickly to prove their designs work and attract investment.

From their perspective, outdated regulations are genuine obstacles. Maybe some of the old rules were designed for large, centralized reactors and don't make sense for small, modular designs. Maybe some requirements are overly conservative and add cost without proportional benefit.

The startup argument is probably: let us build and demonstrate our technology. If it works, we'll get investment and support. If it fails, we'll iterate and try again. We don't need government restrictions; we need freedom to innovate.

There's some merit to that argument. Excessive regulation can slow innovation. At some point, regulators have to allow new technology to be tested.

But there's a difference between allowing innovation and eliminating safety oversight. You can streamline approval processes without removing safety requirements. You can trust companies to innovate while still maintaining baseline protections for workers and the public.

The concern is that by conflating these two things—removing obstacles to innovation AND removing safety requirements—the rule changes create a false choice. It's not innovation versus safety. It's innovation with safety versus innovation without safety.

Comparison to Other Industries' Regulatory Timelines

When the federal government wants to accelerate development of new technology, how quickly can it move while maintaining safety?

The aerospace industry offers an instructive comparison. When new aircraft designs are developed, there's regulatory oversight from the FAA. That oversight is detailed and involves extensive testing. But aircraft companies and the FAA have figured out how to move relatively quickly. New aircraft types can get approved in years rather than decades.

How? By separating what needs to be completely new (the airframe design) from what can be proven (safety systems, materials, manufacturing processes). By establishing clear testing protocols that, once met, result in automatic approval. By creating incentives for both speed and safety.

The nuclear industry has tried similar approaches. Reactor designs can be pre-certified by the NRC, meaning that the design itself has been approved and companies can build it without each reactor needing individual approval.

But none of that involves eliminating safety requirements. It involves streamlining the process while maintaining the requirements.

That's different from what happened with the recent DOE rule changes. Those changes didn't streamline processes. They removed requirements.

What Happens If Something Goes Wrong

This is the uncomfortable question underlying all of this: what's the risk if these relaxed rules actually do contribute to a safety incident?

Nuclear accidents are rare, but when they occur, they're severe. Three Mile Island is the worst U. S. nuclear accident. It involved meltdown of the reactor core and release of radioactive material. The cleanup took years and cost billions. Nobody died in a dramatically catastrophic way, but people were exposed to radiation and the cleanup workers faced risks. The incident basically ended new nuclear development in America for a generation.

Chernobyl was worse. Catastrophic core explosion, massive radiation release, thousands of square kilometers made uninhabitable, thousands of deaths from acute radiation poisoning, thousands more from radiation-induced cancer.

Fukushima involved multiple reactor failures and a huge evacuation. Nobody should want to be responsible for any incident approaching that scale.

The odds that the rule changes directly cause a major incident are probably low. Most nuclear accidents are rare events that require a cascade of failures. Removing some safety oversight doesn't guarantee an accident.

But it increases the probability. And it means that if something does go wrong, the federal government will be partially responsible because it removed the oversight that might have prevented it.

That's a meaningful risk. It's not a certainty, but it's a real possibility, and it's a risk that the public wasn't given a chance to evaluate.

Potential for Congressional or Legal Challenge

Will anything change? Congress could potentially legislate new requirements. Environmental groups could sue, arguing that the rule changes violated the Administrative Procedure Act by being implemented without proper public notice. The NRC could assert that it has authority over these facilities.

All of those things are possible. Congress is divided and probably won't take action. Environmental litigation takes years and might fail. The NRC's authority is limited to civilian reactors, and the DOE facilities might be outside its domain.

So in practical terms, the rule changes might stick. They might become the baseline for however many reactors get built on DOE property over the next few years.

If those reactors operate safely, the debate becomes historical: were the rules needed or not? If something goes wrong, the debate becomes: who was responsible for the failure?

Either way, the lack of public process around these changes is a problem. It means the public never had a chance to evaluate the trade-offs or voice concerns. And that's a governance issue regardless of whether the safety risks materialize.

The Broader Context: Climate Change and Energy Policy

It's important not to lose sight of the original reason for this story: climate change and the need for clean energy.

Climate change is real and urgent. The current global energy system is powered primarily by fossil fuels that release greenhouse gases. Transitioning away from fossil fuels is one of the most important challenges of our time. Nuclear energy could be a significant part of that transition.

Modern nuclear plants are very safe and very clean. They produce enormous amounts of electricity with essentially zero greenhouse gas emissions. Building more nuclear capacity would be genuinely valuable for climate goals.

Small modular reactors might be an important part of this transition. They could provide power in locations where large plants don't make sense. They could power data centers and other distributed facilities. They could replace retiring coal plants using existing infrastructure.

The argument for accelerating nuclear development is strong. The climate stakes are high. Moving quickly on nuclear development is justified.

But moving quickly doesn't have to mean removing safety oversight. You can want nuclear development and still insist on safe nuclear development. Those aren't contradictory goals.

The concern is that by framing them as opposed (fast vs. safe), and by choosing fast, the administration has created a framework where the nuclear industry's development goals take priority over public protection.

That framework persists regardless of whether individual reactors operate safely. And it could create problems down the road.

What's Next for Nuclear Startups

Assuming the rule changes stick and the July 2026 deadline approaches, what should we expect?

Some startups will probably hit the deadline. They'll demonstrate working reactors, probably on a limited scale. They'll generate power and claim victory. That will be genuinely impressive and will probably attract more investment and attention.

Other startups will miss the deadline. They'll complete work in 2027 or 2028. They'll probably still succeed commercially if their technology is sound, but they'll lose the symbolic and political value of the July 4th target.

As these demonstration reactors come online, the industry will shift toward commercial deployment. That's where the real scale comes in. If the technology works, you'll see companies trying to build fleets of reactors rather than single demonstration units.

That's when the rule changes will really matter. Because operating dozens or hundreds of reactors built under loosened safety rules creates different aggregate risks than operating a handful of demonstration reactors.

And that's the critical question that wasn't decided through public process: as nuclear deployment scales up, what safety standards should apply?

FAQ

What are the main nuclear safety rules that were changed?

The Trump administration removed or significantly revised approximately one-third of the federal nuclear safety rulebook for reactors on Department of Energy property. Key changes include making groundwater contamination monitoring and limits voluntary rather than mandatory, increasing allowable radiation exposure limits for workers, and transferring security protocols from federal standards to company discretion. These changes were implemented without public notice or comment, departing from typical federal regulatory procedures.

Why did the Department of Energy make these rule changes?

The changes were made to accelerate nuclear reactor development, particularly to meet a July 4, 2026 deadline set by the Trump administration for demonstrating new reactor technology. Nuclear startups racing to develop demonstration reactors on DOE property face time and budget pressures, and the relaxed rules were intended to remove perceived regulatory obstacles. The changes also reflect broader pressure from tech companies building data centers that need reliable power sources for AI operations.

How do the new rules compare to regulations at other nuclear facilities?

Reactors built on Department of Energy property now operate under significantly looser oversight than reactors regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), which oversees civilian nuclear plants elsewhere in the United States. The NRC maintains more stringent environmental protection requirements, radiation exposure limits, and security protocols. This creates a two-tier system where new startups building demonstration reactors face fewer regulatory requirements than established utilities operating traditional plants.

What are the health risks associated with increased worker radiation exposure limits?

Higher radiation exposure limits mean workers can accumulate more radioactive dose during their careers before hitting the exposure ceiling. This increases long-term health risks including cancer, cataracts, and other radiation-induced illnesses. The specific risk depends on the magnitude of the increase and the actual exposure workers receive, but any increase above previously established protective limits means some workers will face higher lifetime cancer risk than they would have under the original standards.

Why is groundwater monitoring important at nuclear facilities?

Groundwater supplies drinking water for millions of Americans and is used for agriculture and industry. Radioactive contamination can persist for decades or centuries due to the long half-lives of isotopes used in nuclear reactors. Once contaminated, groundwater is extremely difficult and expensive to remediate. Monitoring requirements ensure that operators detect contamination early and can take action before it spreads widely or reaches public water supplies.

Could these rule changes face legal challenges?

Yes, the rule changes could potentially be challenged under the Administrative Procedure Act, which generally requires federal agencies to follow specific procedures including public notice and comment periods when making significant regulatory changes. Environmental groups and public interest organizations have already raised questions about whether the process violated these requirements. However, litigation would take years, and courts might find that the DOE had discretion to change rules under its authority over DOE facilities.

How do these changes affect climate change goals?

Nuclear energy is carbon-free and could play an important role in transitioning away from fossil fuels. Accelerating nuclear reactor development supports climate change goals. However, the rule changes prioritize speed over established safety protections, creating a potential false choice between moving quickly and staying safe. Climate advocates disagree on whether removing safety oversight is necessary to accelerate nuclear development.

What timeline are nuclear startups working under?

Several nuclear startups are attempting to demonstrate working reactors by July 4, 2026, roughly 18 months from the announcement. This is an extremely aggressive timeline by nuclear industry standards, where reactor development typically takes a decade or more. The deadline is politically symbolic rather than based on realistic engineering timelines, creating pressure to cut corners on safety and testing.

How does this compare to nuclear safety in other countries?

Most developed countries, including France, Canada, and South Korea, maintain strict nuclear safety standards even while trying to accelerate reactor development and approval processes. They streamline administrative procedures rather than eliminating safety requirements. International approaches typically maintain public processes for approving reactor designs and monitoring safety, contrasting with the confidential rule changes made by the DOE.

What happens if a reactor built under the new rules has a safety incident?

If a safety incident occurs, the federal government shares responsibility because it removed the oversight that might have prevented the incident. A serious accident could set back nuclear development for years, similar to how Three Mile Island effectively ended nuclear development in America for decades. Even if incidents don't occur, the lack of public process around the rule changes means the public never had a chance to evaluate and accept the risks involved.

Conclusion: Speed, Safety, and Democratic Process

This story isn't ultimately about whether nuclear energy is good or bad. Most experts agree that nuclear power is important for climate change mitigation. The story is about how we make decisions about risky technologies and whether we allow speed to override transparency and public participation.

The Trump administration made a calculation: accelerating nuclear development is important enough to justify loosening safety oversight. They implemented that calculation through administrative action, without public notice or comment. From a purely results-oriented perspective, if the reactors operate safely and nuclear development accelerates, the calculation might have been right.

But from a democratic and governance perspective, the decision-making process itself was problematic. Federal agencies are supposed to follow specific procedures when making rule changes. The public is supposed to have a chance to comment on changes to safety standards that affect workers and communities. Congress is supposed to oversee major policy shifts.

None of that happened. The changes happened quietly, announced only after the fact, with no opportunity for public input.

That's the core of the concern. It's not necessarily that the new rules are wrong. It's that they were made wrongly. And that matters because decisions made without public input are more likely to reflect narrow interests rather than broad public values. And in nuclear safety, public values matter. Nuclear facilities exist near people's homes. Those people deserve a voice in decisions about safety standards.

The coming months will tell whether this approach actually accelerates nuclear development or creates legal and political problems. Startups will rush to build reactors. Some will probably succeed in hitting the July deadline. Some will probably miss it but eventually produce working plants. The technology might prove sound and valuable.

But the question of whether this was the right way to make these decisions will linger. It's a question about not just nuclear safety, but about how government makes decisions about public health and environmental protection.

That's a question that deserves more attention than it's received.

Key Takeaways

- The DOE removed approximately one-third of nuclear safety rules on federal property without public notice or comment, violating standard federal administrative procedures

- New rules eliminate mandatory groundwater monitoring, increase worker radiation exposure limits, and transfer security protocols to private operators

- Nuclear startups are racing to meet a July 4, 2026 deadline for demonstrating new reactor technology, creating pressure to cut safety corners

- Data center demand for AI computing power is a major driver of nuclear development acceleration, but this shouldn't come at the cost of worker and environmental safety

- The rule changes prioritize speed over precaution and bypass public input on decisions that affect workers and communities near nuclear facilities

Related Articles

- Offshore Wind Legal Victories: Why Trump's Setbacks Matter [2025]

- Trump and Governors Push Tech Giants to Fund Power Plants for AI [2025]

- Nuclear Startups and Small Modular Reactors: Can Manufacturing Really Fix the Problem? [2025]

- Meta's Nuclear Bet With Oklo: Why Tech Giants Are Fueling the Energy Revolution [2025]

- Grok's CSAM Problem: How AI Safeguards Failed Children [2025]

- Coal Plant Emergency Orders: Trump's Energy Policy Strategy [2025]

![Trump Administration Relaxes Nuclear Safety Rules: What It Means for Energy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/trump-administration-relaxes-nuclear-safety-rules-what-it-me/image-1-1769641614533.jpg)