The Power Crisis Behind AI's Explosive Growth

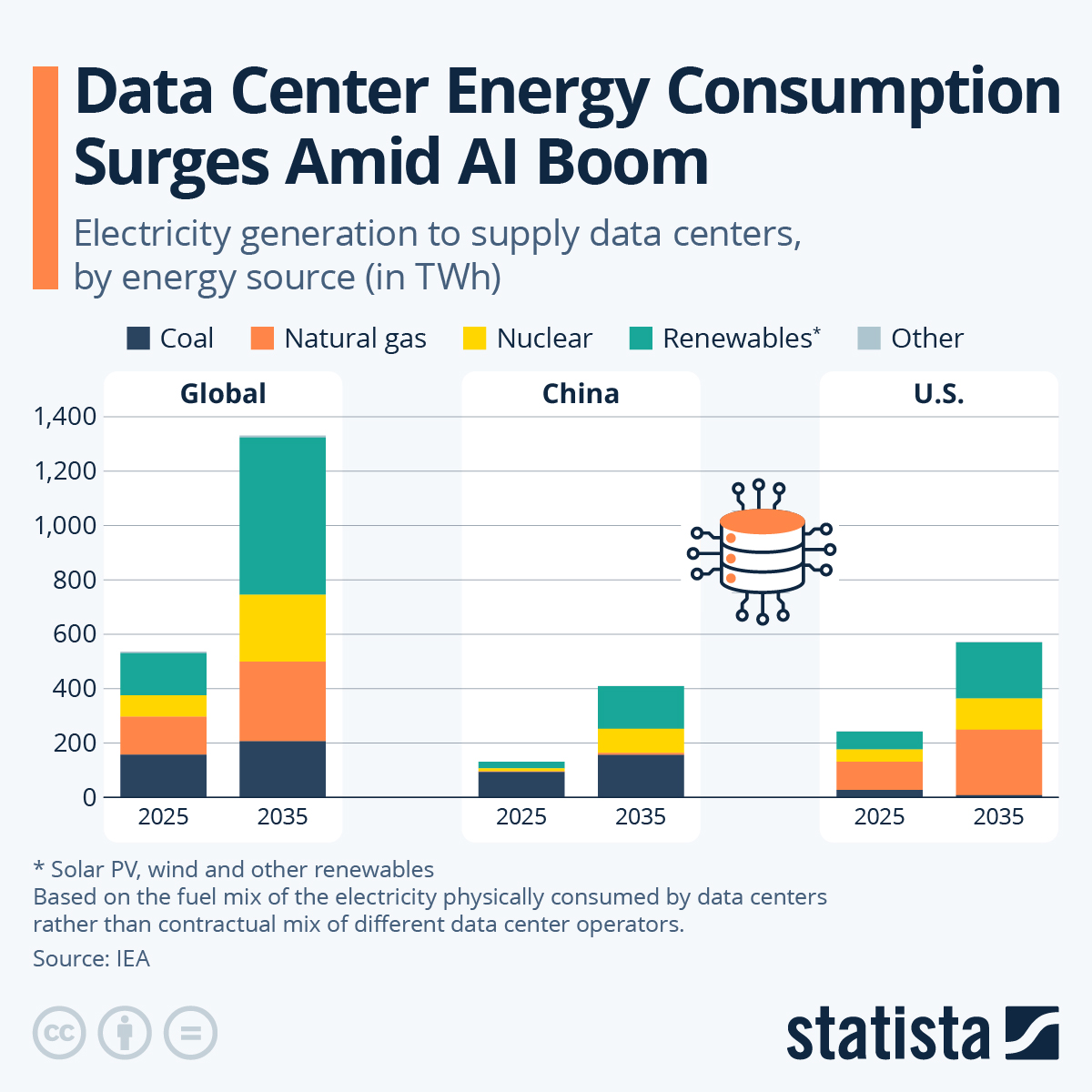

America's electricity grid is facing a reckoning. Data centers pulling power for artificial intelligence systems are consuming electricity at rates that rival entire cities, and the infrastructure simply can't keep pace. This collision between surging AI demand and aging power infrastructure has created a political flashpoint that's united an unlikely coalition: the Trump administration, Democratic governors, and Republican leaders who typically don't see eye to eye on much of anything.

The core tension is straightforward but explosive. Tech companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are building massive data centers to power their AI services, and these facilities consume staggering amounts of electricity. A single large data center can use as much power as 80,000 homes. Yet these companies haven't traditionally been responsible for building the power plants that keep their operations running. Instead, they've tapped into public electricity grids designed decades ago for a very different world. Regular people—homeowners, small businesses, hospitals—are watching their electricity bills climb while corporations get first access to the grid.

This is where the political pressure explodes. Governors across the Mid-Atlantic region, from Democratic areas like Pennsylvania and Maryland to Republican strongholds, are seeing their constituents' energy costs spike. The Trump administration, meanwhile, wants to accelerate energy infrastructure buildout while simultaneously pushing coal and natural gas over renewable energy. But here's the catch: regardless of what energy source powers new plants, someone has to pay to build them, and the Trump administration and governors believe that someone should be the tech companies reaping the profits from AI services.

What's remarkable about this moment is the breadth of the coalition. Democratic governors like Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania and Wes Moore of Maryland signed the same statement as Republican leaders and Trump administration officials like Secretary of Interior Doug Burgum and Secretary of Energy Chris Wright. This isn't partisan grandstanding—it's a genuine alignment around the principle that corporations powering unprecedented data consumption should fund the infrastructure that makes it possible.

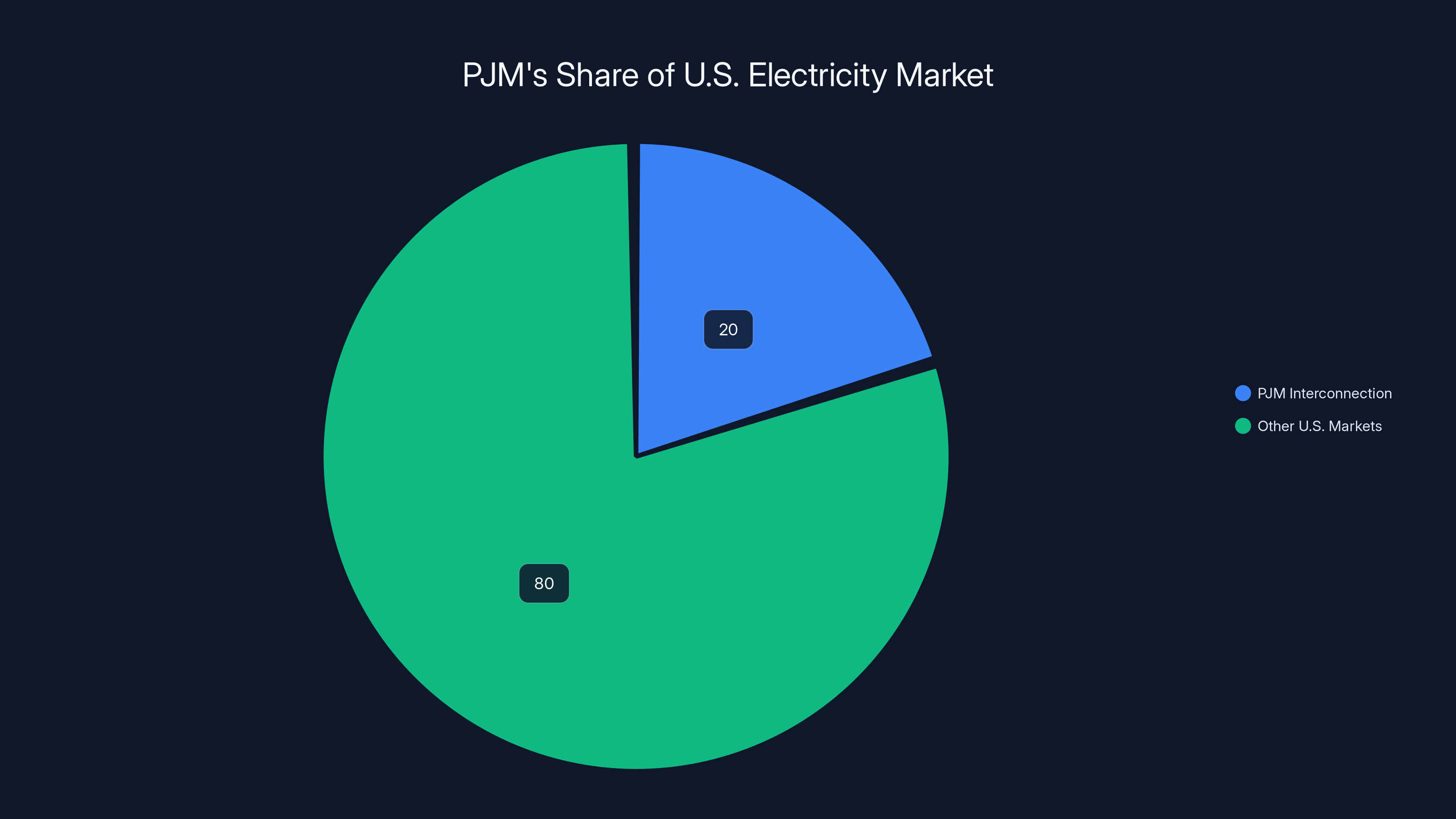

But the mechanics of how to achieve this are far trickier than the political consensus suggests. The proposed solution involves something called the PJM Interconnection, a regional electricity market operator that manages the power grid covering 13 states across the Midwest and Atlantic. PJM is where the real negotiation will happen, and it's where the feasibility of this grand plan starts to get complicated.

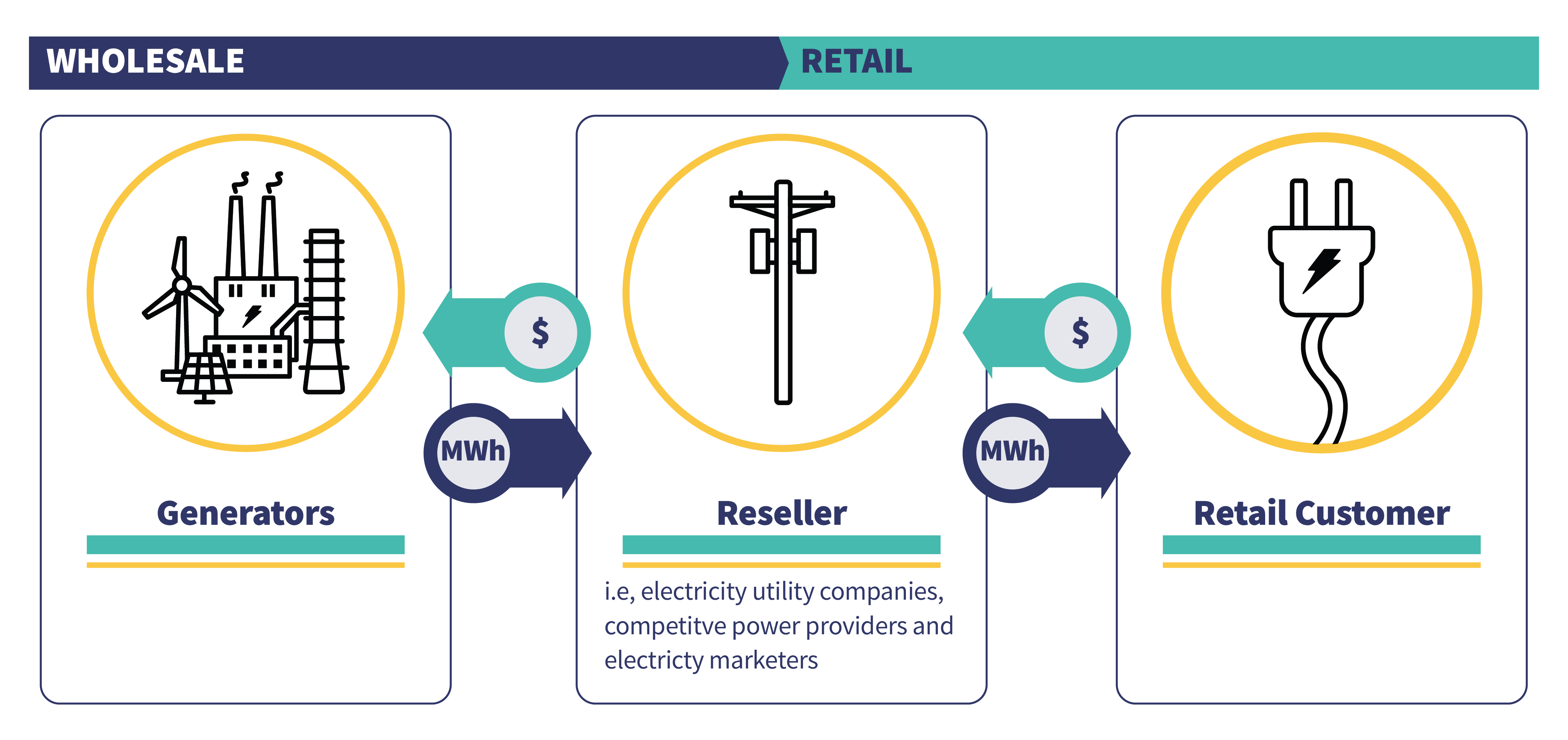

Understanding PJM and the U. S. Electricity Market

The PJM Interconnection isn't a household name, but it's arguably one of the most important infrastructure operators in America. It manages the largest competitive electricity market in the United States, covering 13 states and the District of Columbia. That territory includes nearly 65 million people and represents over 20 percent of the nation's total electricity consumption. If you live anywhere from New Jersey to North Carolina, or across the Midwest toward Illinois, your power likely flows through PJM's network at some point.

PJM operates differently than traditional utility companies. Rather than a single entity controlling generation, transmission, and distribution, PJM acts as an independent operator managing a competitive marketplace where generators bid to provide power. This creates what economists call a "day-ahead market" and a "real-time market," where power prices fluctuate based on supply and demand. It's more like a stock exchange for electricity than a traditional utility.

This market structure matters enormously for understanding the current crisis. When demand spikes—say, because thousands of new servers come online in data centers—prices rise. Generators then have incentives to build new capacity. But building new power plants takes years and costs billions of dollars. Historically, generators could justify these investments based on projections of electricity demand growth. Utilities would invest in new plants assuming modest 2-3 percent annual growth.

AI data centers break this model. The demand growth isn't modest—it's explosive and concentrated geographically. Virginia, particularly around Northern Virginia near Washington D. C., has become America's data center hub. The concentration makes sense historically: proximity to government contracting opportunities, established tech corridors, and existing fiber optic infrastructure. But this concentration means Virginia's local power grid faces demand growth rates that were completely unforeseeable just five years ago.

Here's the math that illustrates the challenge. A typical data center might draw 50 to 100 megawatts of continuous power. A large one could draw 300 megawatts or more. For context, the average coal power plant generates about 500-600 megawatts. So when a single data center customer arrives and wants grid capacity, it's equivalent to a significant power plant's worth of demand appearing almost overnight. Scale that across dozens of new data centers being planned in the Mid-Atlantic region, and you're looking at demand equivalent to 5-10 large power plants that don't exist yet.

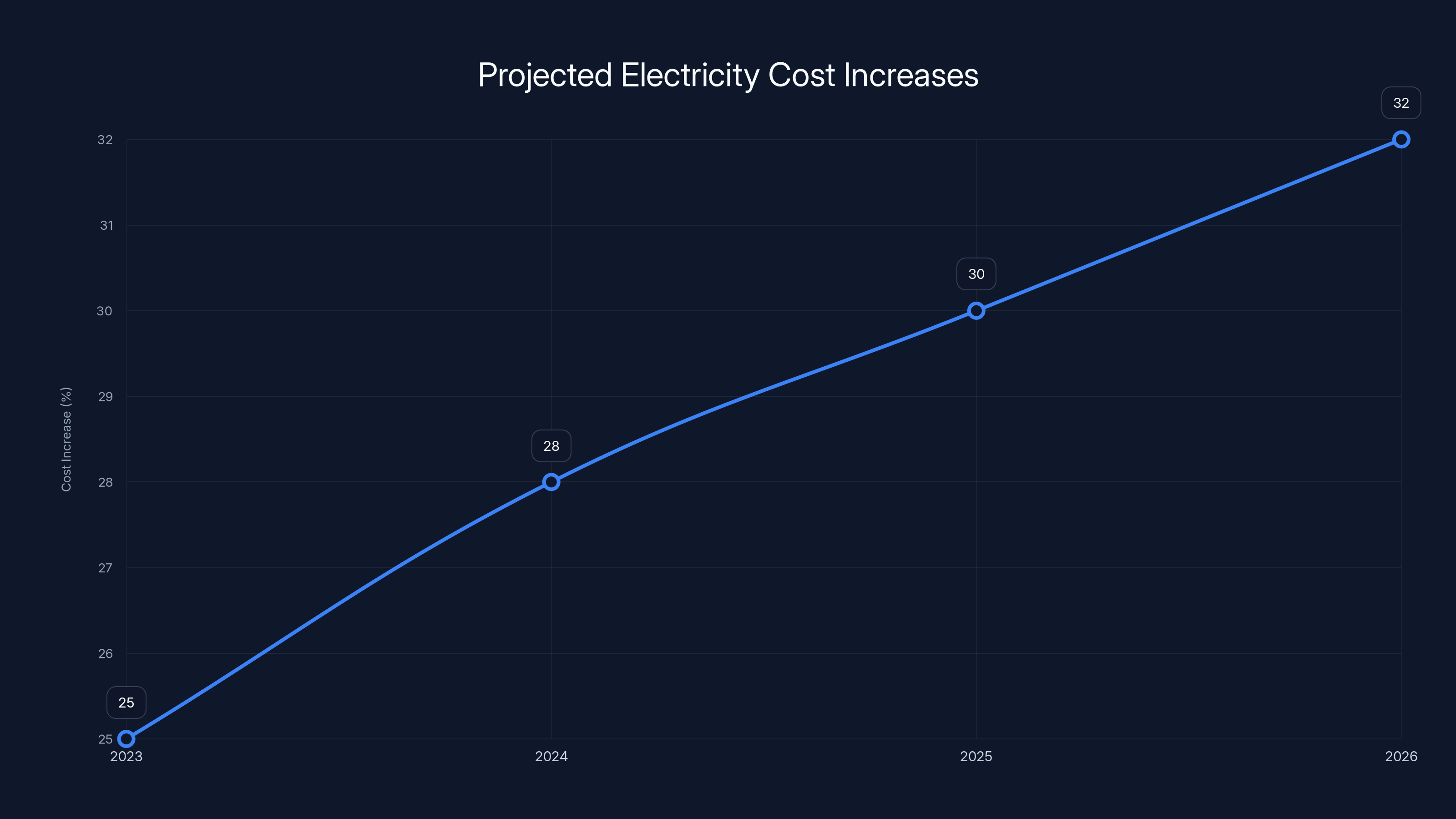

PJM's traditional mechanisms for attracting power plant investment rely on wholesale electricity prices rising to levels that make new generation profitable. But here's where market mechanics create a political problem: those higher prices get passed through to regular residential and commercial customers. People see their electricity bills rising 10, 20, even 30 percent, and they don't understand or care that it's because AI companies need more power. They just see that their energy costs are climbing.

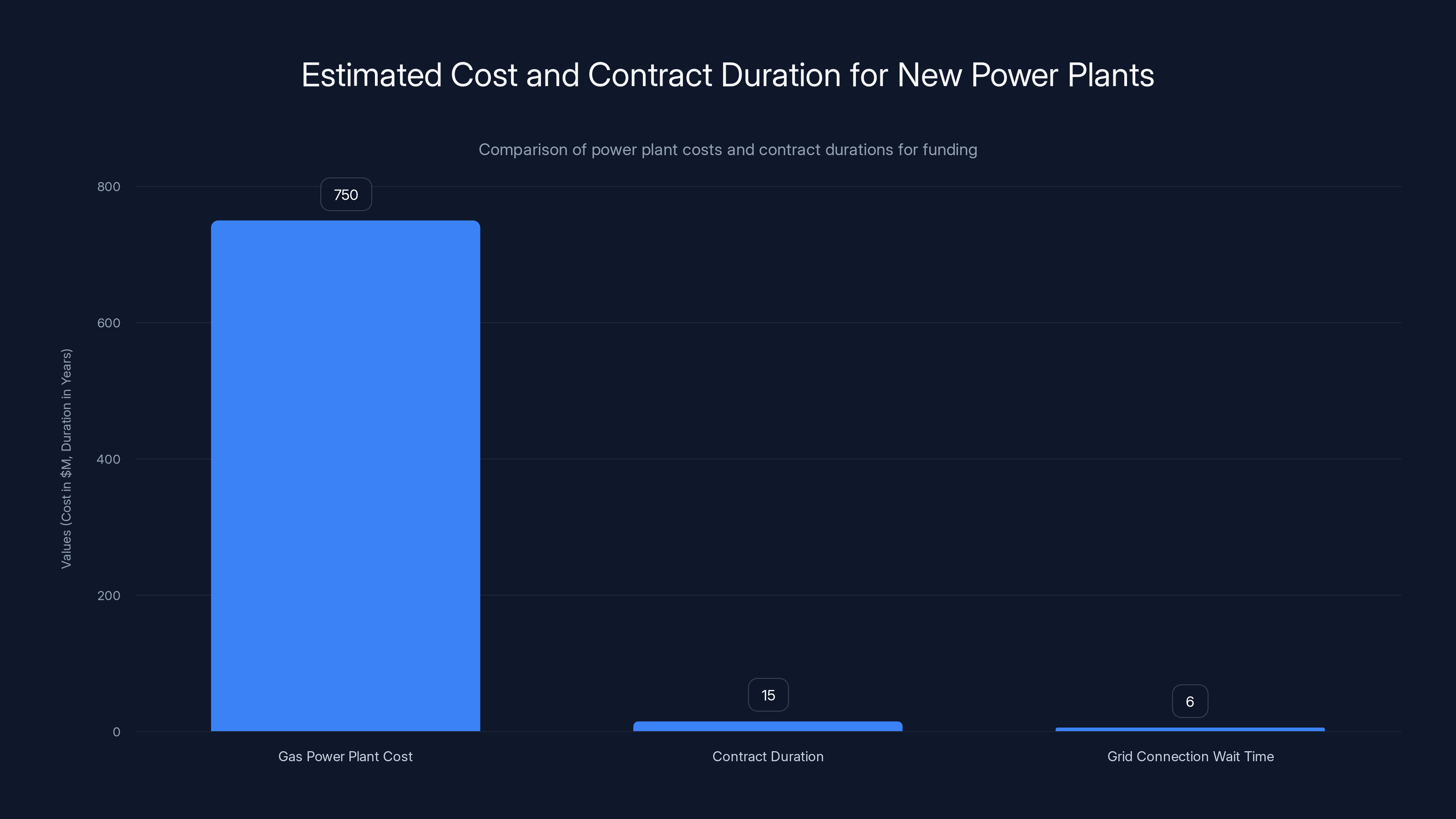

Estimated data shows a typical gas power plant costs $750 million, with a 15-year contract duration and a 6-year average grid connection wait time. (Estimated data)

Why the Emergency Auction Proposal Makes Sense on Paper

The proposed emergency auction represents a genuinely innovative approach to a complex problem. The core idea is to separate the cost of new power plant construction from the regular electricity market, where costs get spread across all consumers. Instead of letting wholesale electricity prices rise gradually—with everyone paying higher rates—the auction would ask data center operators to directly fund new power plants through long-term contracts.

The specific mechanism proposed involves 15-year contracts. This duration is crucial because it addresses the fundamental economics of power plant construction. A new gas power plant costs

From the developers' perspective, this also solves a real problem they face: grid congestion. When a data center wants to connect to the grid, it needs to wait in a queue while transmission system upgrades and new generation get built to serve its demand. This process can take years. Multiple data center developers have reported waiting times of 5-7 years just to secure grid connection. By funding power plants directly, data centers could theoretically accelerate this timeline. Instead of waiting for the market to build capacity, they fund it themselves and jump the queue.

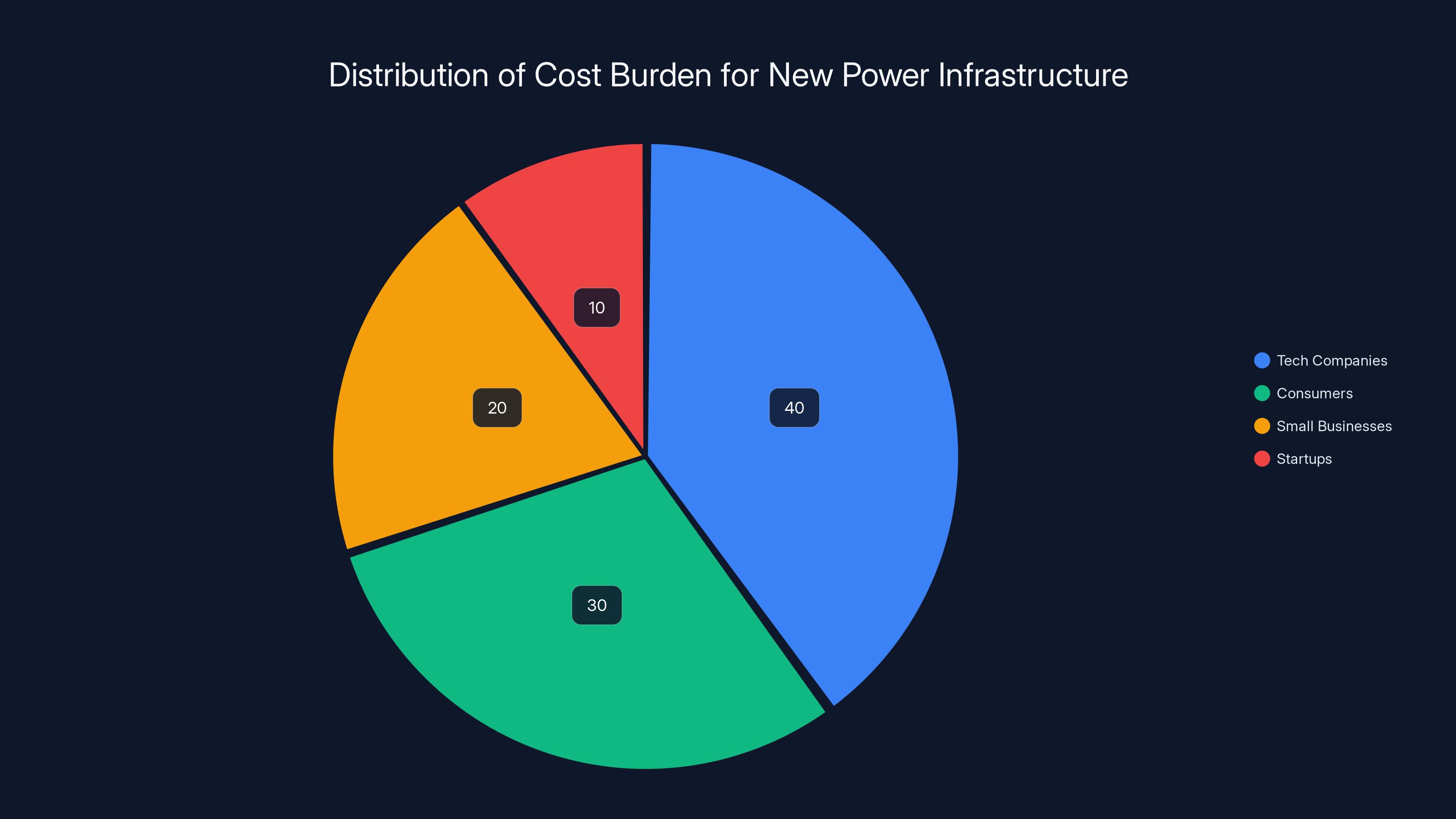

The cost allocation proposed by the Department of Energy is also worth examining. Rather than spreading the entire cost of new generation equally across all customer types, the DOE suggests that data centers should bear the full cost unless they either bring their own power plants online or agree to reduce their consumption during peak demand periods. This creates three distinct pathways: have the utility build and charge you accordingly, build your own power plant, or be part of a demand-management program.

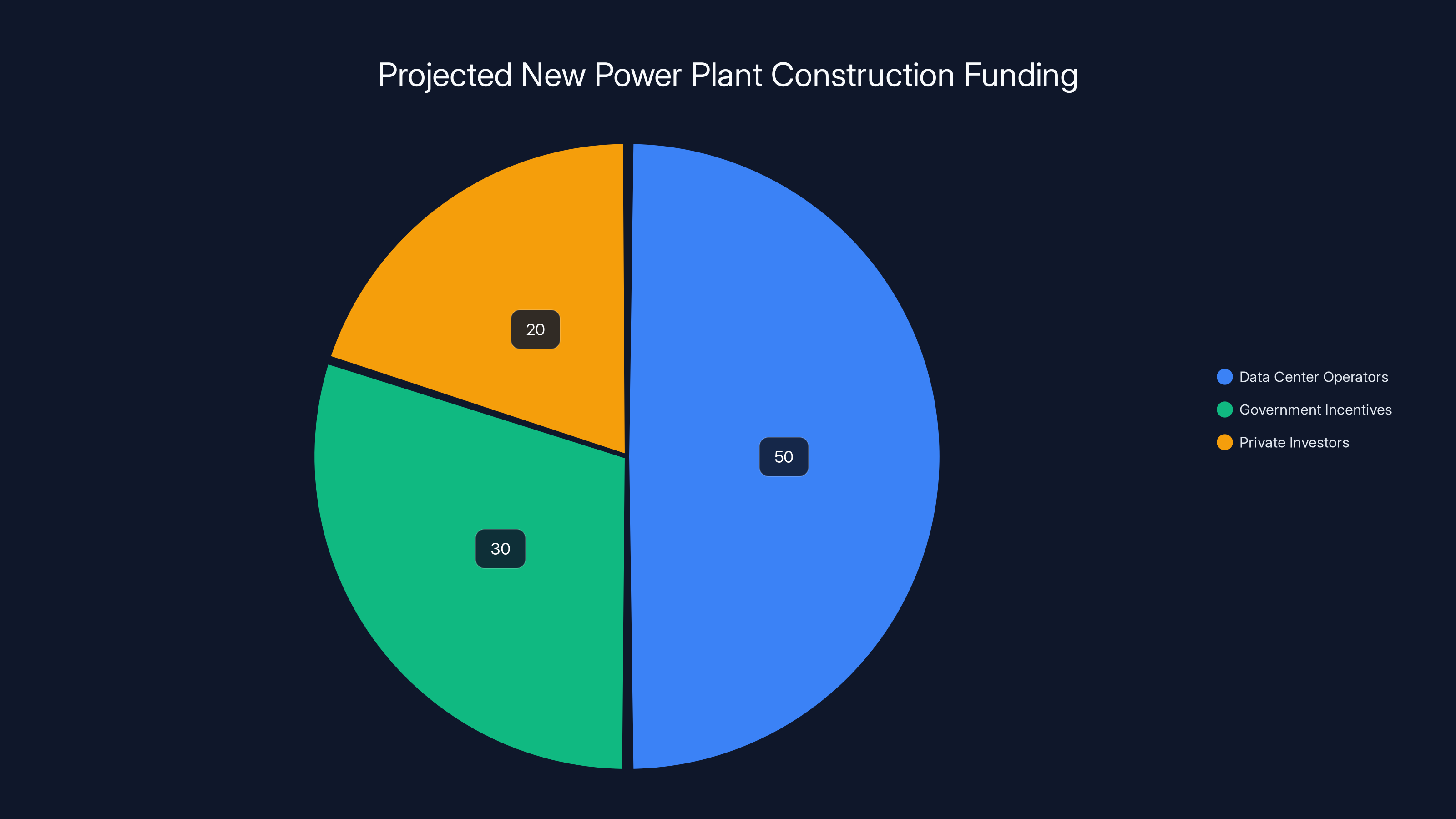

The DOE's analysis suggested this approach could trigger

Why would this work? The mechanism relies on basic economic incentives. Data center developers want to locate in Northern Virginia for good reasons: the tech talent cluster, proximity to government customers, existing fiber networks. They'll pay premium prices for power if it means they can deploy their facilities faster. Once a power plant is announced and linked to a specific buyer through a long-term contract, financing becomes far easier and cheaper. The utility or independent power producer building the plant can point to a 15-year revenue stream and get favorable financing terms.

Estimated data shows that data center operators could contribute 50% of the $15 billion needed for new power plant construction, with government incentives and private investors covering the rest.

The Political Complexity of Making Tech Companies Pay

Here's where the elegant economic theory meets political reality. The Trump administration and governors can urge PJM to hold an emergency auction, but they can't actually mandate it. PJM operates as an independent system operator with its own governance structure. It answers to a board that includes state utility commissioners, consumer advocates, power producers, and other stakeholders. It's not a traditional government agency that can be ordered around.

Moreover, notably, PJM wasn't even invited to the announcement where the Trump administration and governors unveiled this proposal. That's not a small detail. It suggests the officials making the announcement didn't coordinate closely with the organization that would actually have to implement it. PJM subsequently issued statements saying they would review the proposal, but the tone wasn't enthusiastic about being told how to operate their market.

The political tension here reflects deeper questions about fairness and burden-sharing. Tech companies and their advocates argue that data centers bring enormous benefits: they create jobs, generate tax revenue, and provide the infrastructure for AI services that benefit everyone. Should companies be charged a premium for using publicly-provided infrastructure? The counter-argument is equally compelling: consumers paid for and maintain public electricity grids through their rates, and it's unfair that new corporate customers should get to use that infrastructure without bearing the costs of upgrading it.

There's also a competitive dimension. If PJM implements aggressive cost-shifting toward data centers, what happens to data center developers considering locations outside the PJM territory? They might choose facilities in other regions with more lenient cost allocation. This could actually undermine the region's competitive position even as it protects existing consumers from bill increases. Other Independent System Operators might offer more attractive terms, and data center development would simply move there.

Additionally, the politics of energy sources complicate the picture. The Trump administration has explicitly stated its preference for coal and natural gas power plants over wind and solar. The governors, meanwhile, include Democrats who've committed to clean energy targets. If a data center funds a new coal plant to secure power contracts, does that advance or hinder climate goals? Pennsylvania's governor, Josh Shapiro, supports natural gas as a transition fuel, but not all Democrats share that view. Maryland's governor, Wes Moore, has climate commitments that might conflict with funding fossil fuel plants.

There's also the question of whether tech companies will actually accept cost-shifting at the scale being proposed. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have made significant commitments to renewable energy. Google has stated it wants to operate entirely on carbon-free energy. If data center costs rise significantly due to grid infrastructure charges, and if those charges fund fossil fuel plants, tech companies might simply build their own on-site renewable generation or seek locations with more favorable terms. That would actually undermine the goal of building new centralized power infrastructure.

How Data Centers Are Already Building Their Own Power Solutions

Before examining whether the emergency auction will actually work, it's worth noting that some tech companies aren't waiting for PJM or any government intervention. They're solving the power problem themselves, and their strategies reveal what might happen if forced cost-shifting makes grid electricity too expensive.

Microsoft has been particularly aggressive. The company has signed power purchase agreements with nuclear plants, including a recently-announced deal to bring the Three Mile Island reactor back online to power data center operations. Amazon has similarly pursued direct renewable power contracts, securing wind and solar capacity through long-term purchase agreements. Google has been funding geothermal energy development in Nevada specifically to power its data centers. These arrangements bypass the traditional electricity market entirely.

When tech companies fund their own power, they control the entire value chain. They choose the fuel source, the location, and the operational parameters. They can design the power generation specifically for data center requirements, which differ from traditional electricity loads. Data centers need consistent, reliable power 24/7, with very different load profiles than residential customers. A private power source can be optimized for these requirements.

This creates an interesting economic dynamic. If the cost of grid power becomes too high due to infrastructure charges, more companies will follow this path. They'll invest in their own generation and transmission, and they'll increasingly operate independently from the public grid. This could actually slow the transition to modernized, integrated power systems. Instead of building a stronger shared grid, you'd get a two-tiered system: corporate-owned power for data centers and whatever remains of public infrastructure for everyone else.

There's historical precedent for this. Large industrial consumers in energy-intensive industries have long built their own generation or secured privileged access to power supplies. Steel mills, aluminum smelters, and petrochemical facilities often have on-site power plants or long-term contracts with dedicated generation. As these industries have consolidated and energy costs have risen, the gap between corporate power costs and consumer rates has widened. The risk with data centers is that you could see a similar divergence: corporate consumers with their own power supplies becoming increasingly insulated from grid constraints and rate increases, while regular consumers bear the full cost of grid modernization.

That's not necessarily all bad from an infrastructure perspective. It might actually accelerate renewable energy development, since tech companies are often willing to invest in wind and solar. But it does create equity concerns. Why should a homeowner in Pennsylvania pay higher rates while Amazon builds its own power infrastructure and operates independently?

Estimated data shows tech companies bear 40% of the cost, but pass it to consumers (30%), small businesses (20%), and startups (10%).

The Renewable Energy Complication

The Trump administration's stated preference for coal and natural gas, combined with its skepticism toward renewable energy, adds another layer of complexity to the emergency auction proposal. From an infrastructure standpoint, what matters is that new power plants get built quickly to meet rising demand. From an energy policy standpoint, what matters is whether those plants align with stated climate and energy goals.

Here's the math on renewable energy that makes this tension real. Wind and solar have become the cheapest sources of new electricity generation on a levelized cost basis. In many parts of the country, new wind or solar capacity is cheaper than running existing coal plants. From a pure economics standpoint, new renewable generation should win auctions. But the Trump administration has signaled preferences for fossil fuels through policy mechanisms like the extension of fossil fuel subsidies and restrictions on wind development permits.

When you combine this with data center demand, you get an interesting outcome. The emergency auction might produce new power plants, but if policy constraints make renewables less competitive, you'd get more gas and coal than optimal economic signals would suggest. This could lock in fossil fuel generation for 15-30 years, extending the lifespan of carbon-intensive energy even as climate science screams for rapid decarbonization.

Several Democratic governors have committed to ambitious clean energy targets. Pennsylvania aims to achieve 60 percent renewable electricity by 2035. Maryland has even more aggressive climate targets. If the emergency auction funds fossil fuel plants, governors might face backlash from environmental constituencies. Conversely, if they try to steer the auction toward renewables, they'll conflict with Trump administration preferences.

The irony is that data center operators themselves often prefer renewable power. Microsoft's Three Mile Island deal, Google's geothermal investments, and Amazon's wind power purchases aren't driven primarily by environmental ideology. They're driven by economics and risk management. Companies worry about long-term fossil fuel price volatility. They worry about reputational damage from powering their AI with coal. They worry about regulatory changes that could limit carbon emissions. From their perspective, investing in nuclear or renewable generation provides more stable, long-term security than depending on fossil fuel markets.

This preference could become a competitive advantage in the emergency auction. If data centers are willing to pay premium prices for renewable power, that could actually drive renewable investment faster than Trump administration preferences would allow. But it depends on whether auction rules allow this, and whether PJM chooses to implement auction structures that reveal these preferences.

The Precedent Question: Has This Been Tried Before?

Calling something an "emergency auction" makes it sound novel, but grid operators have experimented with capacity auctions and long-term contracting before. Understanding these precedents clarifies what might actually happen if the proposal moves forward.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which oversees independent system operators like PJM, has long encouraged capacity markets. These are auctions where generators bid to provide power capacity for future periods. The idea is to price the value of reliable generation—not just the fuel cost of generating power, but the cost of having generation available even during peak demand periods. Capacity auctions have existed in PJM and other regions for years.

But there's a crucial difference between existing capacity auctions and the proposed emergency auction. Existing auctions are regional and focus on overall system reliability. The proposed emergency auction would be more narrowly targeted: using long-term contracts to attract new generation specifically to serve data center demand. This is more like a targeted procurement than a general market mechanism.

The closest precedent might actually be renewable energy auctions that some states have held. States like New York and California have run auctions specifically designed to attract renewable generation meeting climate targets. These auctions work by allowing qualified renewable developers to bid, with winners receiving long-term power purchase contracts. In some cases, the auctions have been incredibly successful at driving renewable investment at competitive prices.

The difference with the proposed data center auction is the timeline. Renewable auctions are often conducted with multi-year timelines, allowing projects 3-5 years to develop before they must deliver power. An "emergency" auction suggests shorter timelines, which could limit bidders' ability to develop projects. A gas power plant can be built in 18-24 months. A coal plant takes longer. A nuclear plant takes a decade or more. If the timeline is truly emergency-speed, you're really only realistically looking at gas generation.

There's also precedent from behind-the-scenes negotiations between tech companies and utilities. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have all been negotiating directly with utilities and regional grid operators about power needs. These negotiations have sometimes resulted in commitments for specific infrastructure investments. Microsoft's Three Mile Island deal, for instance, involved direct negotiations with the plant's operator and state regulators. Rather than waiting for auction processes, tech companies are increasingly using their market power to negotiate dedicated power supplies.

This suggests that the emergency auction might become unnecessary if companies continue this trajectory. But it also suggests that without coordinated auction processes, power investment decisions would be made one deal at a time, based on individual company negotiations rather than systematic planning. That could lead to inefficient outcomes where more capacity gets built than necessary in some areas while shortages persist in others.

Electricity costs are projected to rise by 20-30% annually due to infrastructure challenges and increased demand from data centers (Estimated data).

The Consumer Cost Question: Who Actually Pays?

Here's the political reality underlying all this policy discussion: regular people are watching their electricity bills climb, and they're furious. That fury is what's driving the bipartisan political pressure for action. But there's a central economic question that determines whether the emergency auction actually solves the problem or simply shifts it around: who ultimately bears the cost of new power infrastructure?

If the cost is genuinely borne by tech companies through higher power purchase prices, then regular consumers benefit. Their bills stop rising as fast because they're not subsidizing data center power infrastructure. From a fairness standpoint, this makes sense: the beneficiaries of data center power (tech companies and their customers) pay the costs.

But here's the catch. Tech companies will pass these costs through to customers. If Amazon pays 30 percent more for electricity at its data centers, it passes that cost along in cloud service pricing. If Google pays more for power, it passes that along in advertising and search revenue. These companies can't absorb billion-dollar cost increases without passing them to customers. So the cost doesn't disappear—it gets reflected in the prices consumers pay for cloud services, AI services, and other tech products.

For many consumers, this isn't a simple tradeoff. Sure, your electricity bill might not rise as fast. But cloud services and AI tools are increasingly essential for business operations. Small companies relying on cloud infrastructure might face significant cost increases. Startups using AI services might find their costs rising dramatically. The cost gets diffused across the economy rather than concentrated on electricity bills.

There's also a question of timing. New power plants take years to build. Even under an emergency timeline, a new gas plant takes 2-3 years from financing to operation. During those years before new capacity comes online, prices will remain elevated. Consumers might see bill increases for years before the auction-funded plants actually generate power and increase supply.

The Department of Energy's analysis assumed that

There's also a distributional question. Different regions of the PJM territory might see very different impacts. Northern Virginia, with its concentration of data centers, will see the most dramatic power needs and likely will attract the most auction-funded generation. Other parts of the territory might see less impact. Yet electricity is traded across the entire region, so prices in low-demand areas get affected by high-demand areas. This could create fairness concerns where consumers in areas with little data center activity pay higher rates to support infrastructure in Virginia.

Data Center Economics and Site Selection

Understanding why data centers locate where they do, and how costs influence these decisions, is crucial for predicting what happens if the emergency auction substantially raises power costs in the PJM region.

Data centers have several location constraints. First, they need abundant electricity. A large facility draws as much power as a small city. Second, they need fiber optic connectivity to move data in and out. Third, they need cooling water for heat dissipation, or advanced cooling systems if water is scarce. Fourth, they increasingly consider tax incentives, labor availability, and proximity to major markets.

Virginia, particularly Northern Virginia, has become the dominant data center location because it excels on most of these dimensions. It sits where multiple major fiber routes converge, connecting to government networks and major internet backbones. It has labor availability from the Washington D. C. metro area's large tech workforce. It has tax incentives that make operations cheaper. And historically, it had abundant electricity at reasonable prices.

But if electricity costs rise significantly in Northern Virginia due to the emergency auction and infrastructure charges, the economic calculus changes. Alternative locations become more attractive. Texas offers abundant land, growing fiber infrastructure, and lower overall energy costs despite higher power purchase prices. Iowa and Illinois offer wind energy advantages and lower costs. New Mexico offers geothermal opportunities. Overseas locations in Ireland, Japan, and other countries offer their own advantages.

We've already seen the beginning of this shift. Google has been expanding data center investments in multiple regions. Microsoft's move to nuclear power partially reflects its search for more cost-stable, long-term power solutions. Amazon Web Services is diversifying geographic locations rather than concentrating all expansion in Northern Virginia. If costs in the PJM region rise too dramatically, you could see accelerated diversification.

This creates a political dilemma. The emergency auction is intended to solve a regional problem—rising electricity costs in the Mid-Atlantic driven by data center demand. But if the auction-driven cost increases are too steep, data centers simply locate elsewhere. The region solves the short-term fiscal problem (new generation gets built) but doesn't solve the underlying issue of meeting regional demand. You'd end up with new power plants built for capacity that companies end up not using because they've relocated.

From a climate perspective, this could even be counterproductive. If Virginia's data centers move to regions with less clean energy capacity, the overall carbon intensity of cloud computing could increase. The infrastructure investment becomes stranded, and emissions outcomes worsen.

The risk isn't theoretical. Similar dynamics have played out with other industrial cost-shifting policies. When particular regions impose higher costs on energy-intensive industries, those industries relocate. The region gets less economic activity, reduced tax revenue, and stranded assets. For it to work, the cost increase needs to be modest enough that the location remains competitive while still meaningful enough to fund the infrastructure.

PJM Interconnection covers over 20% of the U.S. electricity market, serving nearly 65 million people across 13 states and D.C. (Estimated data)

Alternative Solutions: What Else Could Work?

The emergency auction is one approach to the power and data center problem, but it's not the only one. Understanding alternatives clarifies what the emergency auction is really trying to accomplish and what problems it might create.

Direct Government Investment: One alternative is for government to directly fund power infrastructure expansion. Rather than placing the burden on tech companies, federal or state governments could fund new power plants as part of infrastructure policy. This would treat electricity like any other critical infrastructure—airports, highways, water systems—that government historically builds. The advantage is that it spreads costs broadly and doesn't disadvantage particular regions. The disadvantage is it requires substantial public spending, which faces political opposition.

Transmission Investment: Another approach focuses on transmission rather than generation. The constraint isn't just power supply but the ability to move power from where it's generated to where it's needed. Investing heavily in transmission infrastructure—upgrading existing lines and building new ones—could allow power from distant generation sources to serve local demand. This is technically elegant but faces its own permitting and cost challenges.

Demand Management: Rather than always building new supply, you could focus on demand management. Data centers could be offered lower rates during off-peak periods and higher rates during peak periods. This would incentivize shifting computational loads to times when the grid has excess capacity. Advanced techniques like thermal energy storage could absorb excess generation and use it later. Smart grids could coordinate data center operations with overall grid needs.

Regulatory Mandates: States could mandate that utilities build power plants to serve growing demand, essentially treating data center power needs like any other obligated load. The utility cost gets socialized across all customers, but it ensures capacity exists. This is how traditional utility regulation worked before competitive markets.

Tech Company Self-Supply: As noted above, tech companies increasingly fund their own generation. Rather than fighting this trend, policy could encourage it. Tech companies could be allowed to build their own microgrids, operate private power plants, and sell excess capacity back to the grid. This maximizes their incentive to invest in efficient, modern generation.

Market Mechanisms Beyond Auctions: PJM could implement more sophisticated capacity markets that better reflect the long-term nature of data center demand without emergency auctions. Financial instruments like power derivatives could allow companies to lock in prices without requiring physical long-term contracts.

Each alternative has costs and benefits. Direct government investment is politically difficult but ensures broad cost-sharing. Transmission investment helps long-term but doesn't solve immediate problems. Demand management requires sophisticated technology and consumer behavior change. The emergency auction attempts to solve the problem by leveraging tech company capital and market incentives.

The key insight is that there's no cost-free solution. New power infrastructure is expensive. The question is who pays and how the burden is distributed. The emergency auction concentrates the cost on tech companies operating data centers. Alternative approaches spread the cost differently: government investment spreads it across all taxpayers, utility mandates spread it across all electricity customers, self-supply concentrates it on specific companies' shareholders, demand management creates timing complexity. Each approach has equity implications.

The PJM Interconnection's Position and Incentives

The success or failure of the emergency auction ultimately depends on PJM's willingness to implement it. Understanding PJM's institutional incentives and constraints clarifies how likely success is.

PJM operates as a nonprofit organization. It doesn't profit from electricity sales or generation investments. It makes money by charging transmission system users for operating and maintaining the grid, and by charging market participants fees for participating in auctions and other transactions. PJM's financial interest is in efficient market operation and cost minimization, not in particular outcomes about who builds power plants.

But PJM has broader mandates beyond just financial efficiency. It's supposed to ensure grid reliability, maintain just and reasonable rates, and accommodate the needs of all market participants. These goals sometimes conflict. Ensuring grid reliability might require expensive infrastructure. Maintaining reasonable rates requires controlling costs. Accommodating all participants might mean serving everyone without discrimination.

The emergency auction pushes PJM toward a more activist role. Instead of neutrally operating markets and letting outcomes emerge, PJM would be actively designing mechanisms to achieve policy goals (more generation, cost-shifting to data centers, urgency around expansion). This expanded role is controversial within the organization. Some PJM staff and board members worry about regulatory pushback. Others worry about setting precedents where governments can direct PJM to favor particular customers or industries.

From a technical perspective, PJM has the expertise to implement an emergency auction. They've run capacity auctions for years. They understand power market mechanics. But implementing something new requires developing rules, educating market participants, and managing complex negotiations. There's also the question of whether an emergency auction is legal under existing regulatory frameworks. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approves PJM's tariffs and market rules. A major new mechanism might require FERC approval, which could take months or years.

There's also a competitive dynamic. If PJM implements aggressive cost-shifting to data centers, what happens to the competitive position of other independent system operators? ISO New England, MISO, and other regions operate power markets in their territories. If PJM becomes hostile to data center development through high cost-shifting, data center developers simply propose facilities in other regions. This could drive data center development away from the PJM region, which might be bad for the region's economic development but actually solves the power constraint problem (by eliminating the demand).

PJM also has to consider generation company interests. The power producers that actually build and operate power plants are PJM market participants. Some prefer traditional utility regulation where long-term cost-of-service contracts guarantee returns. Others prefer competitive markets where they bid aggressively. An emergency auction creates a hybrid mechanism with elements of both. Existing generators might worry about depressed prices if lots of auction-funded generation comes online. Potential new generators might welcome the opportunity for long-term contracts providing revenue certainty.

The announcement that PJM wasn't invited to the press conference reveals something important about the political dynamics. The Trump administration and governors made a public commitment to an emergency auction, but they didn't coordinate with the organization that would implement it. This suggests political posturing ahead of actual negotiation. The real work of designing the auction, determining rules, and managing implementation will happen in quieter conversations between PJM, state regulators, and government officials. The public pressure is intended to motivate those conversations.

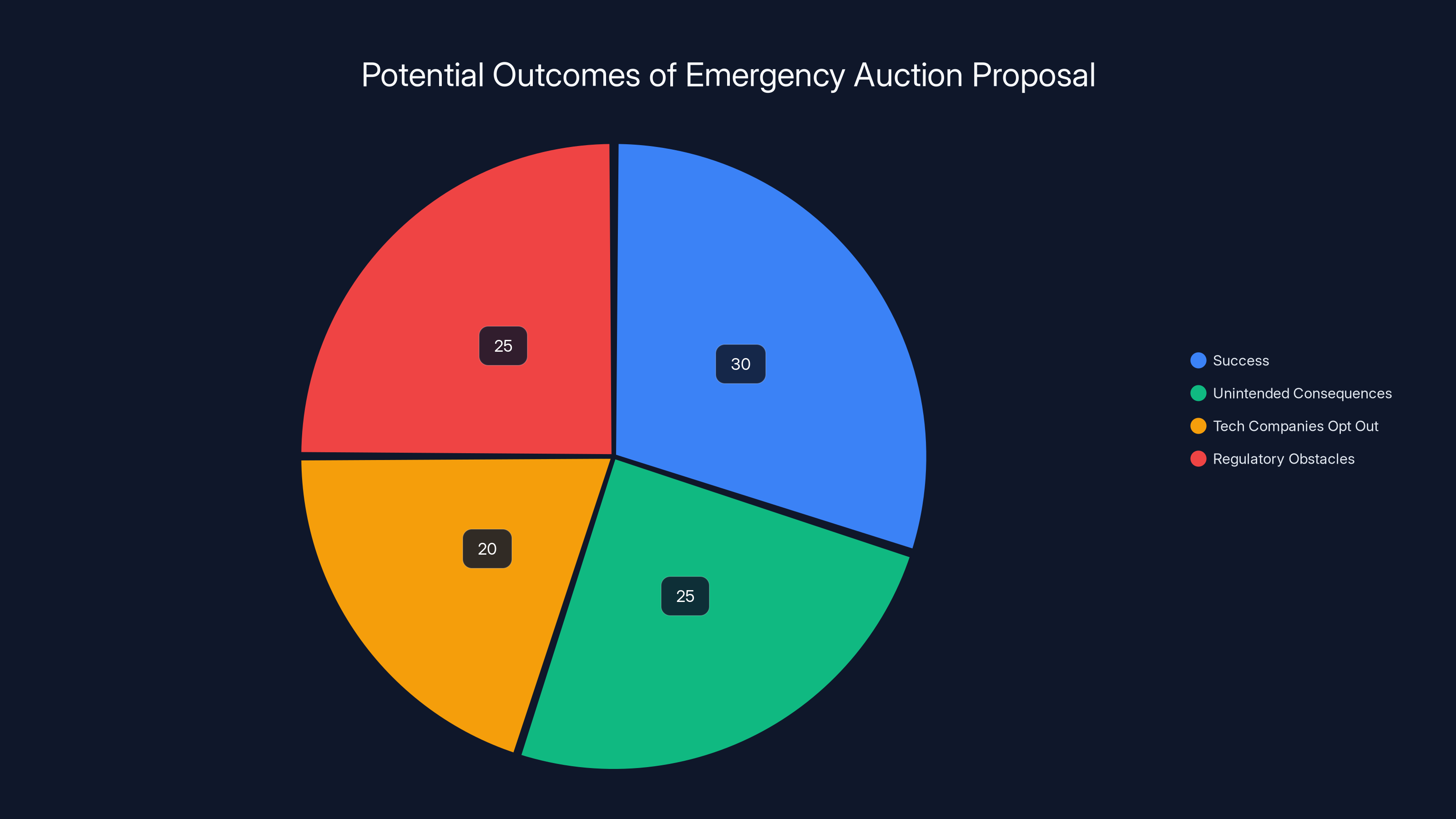

Estimated data suggests a balanced distribution of potential outcomes, with no single scenario overwhelmingly likely. This reflects the complexity and uncertainty surrounding the emergency auction proposal.

The Timeline Question: Can New Power Plants Actually Be Built Quickly?

One critical practical question underlies the entire emergency auction proposal: can power plants actually be built fast enough to matter? If the auction is truly an emergency response, the timeline matters enormously.

Construction timelines vary dramatically by technology:

Natural Gas Power Plants: 18-36 months from financial close to operation. These are the fastest to build and most likely to be built if auction timelines are tight. A 500 MW gas plant might cost $500 million and require 2-3 years of construction after financing is arranged.

Coal Power Plants: 5-7 years. Too slow for an emergency timeline. If the Trump administration wants coal, the auction isn't the mechanism to achieve it quickly. Coal plants require environmental permitting, specialized equipment, and long construction periods.

Nuclear Power Plants: 10-15 years for new plants, though existing plants being restarted (like Three Mile Island) are much faster. Small modular reactors, which some see as the future of nuclear, are still being developed and aren't at commercial scale yet.

Renewable Energy: Variable, but often 18-24 months for wind or solar farms. Renewable auctions have shown that projects can be built relatively quickly if permitting is streamlined. The challenge is siting (getting local approval), permitting (environmental reviews), and connection to the grid (transmission upgrades).

Given these timelines, an "emergency" auction realistically produces natural gas plants. That's what can be built in 2-3 years. If the administration wants to claim success in a first term, gas is the only realistic option. This creates a tension with stated policy preferences for coal and skepticism toward renewables. The emergency auction would likely produce the opposite energy mix from what administration policy statements suggest.

These timelines also highlight a problem with auction design. If you announce an emergency auction and companies bid to build gas plants, those plants won't come online for 2-3 years. During those years, data center demand continues to grow. The power shortage persists until the new plants actually generate power. There's potentially a multi-year period where costs are high and shortages are acute, before the auction-funded solutions come online.

This argues for solutions that work faster: demand management that reduces consumption immediately, grid modernization that moves power more efficiently from generation to loads, and accelerating private company investments in their own generation. These can reduce pressure within months or a year. Auction-funded power plants are important for long-term solutions but aren't the fastest tool available.

One more timing consideration: data center development itself takes years. Companies don't instantly build facilities once grid capacity is available. A large data center takes 18-24 months to develop after grid connection is secured. So the timeline for solving the power problem isn't synchronous with the timeline for building new data centers. The emergency auction might produce plants that come online just as data center construction is completing, or might produce plants years before demand materializes. Coordinating these timelines is genuinely difficult.

State-Level Variations and Regional Conflicts

The bipartisan governor statement calling for the emergency auction masks significant regional variations in interests and constraints. Understanding these differences is crucial for predicting what actually happens.

Virginia: The epicenter of data center expansion, facing the most acute power constraints and the highest pressure for solutions. But Virginia also has complex interests. The state benefits economically from data center development—jobs, tax revenue, economic growth. But residents see higher electricity costs. Governor Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, supports business-friendly policies but also needs to manage constituent concerns about rising costs. Virginia has been trying to address this through state-level initiatives, but ultimately relies on federal policy and PJM mechanisms.

Pennsylvania: Governor Shapiro, a Democrat, faces interesting political dynamics. Pennsylvania has coal interests (historical coal production, some remaining coal plants) alongside growing renewable energy investment. Data center demand is rising, but Pennsylvania isn't as concentrated a data center hub as Northern Virginia. Shapiro's support for the emergency auction reflects urban voters in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia concerned about electricity costs, but he has to balance this with coal and natural gas industry interests that are politically important in western Pennsylvania.

Maryland: Governor Wes Moore faces similar tensions. Maryland has committed to clean energy goals including 100 percent clean electricity by 2035. If the emergency auction funds fossil fuel plants, that conflicts with climate commitments. But Maryland also faces rising electricity costs affecting residents. Moore's joining the call for the auction suggests either he believes it can be structured toward clean energy, or that addressing cost concerns takes priority over clean energy timeline concerns.

New Jersey: Has ambitious clean energy and offshore wind targets. New Jersey's inclusion in the governor statement suggests they're focused on cost concerns overriding clean energy preferences, at least in near term. New Jersey has less data center development than Virginia or Maryland but is part of the PJM footprint.

Republican-led states: States like Ohio and Indiana, which are also part of PJM, have political leaders aligned with Trump administration preferences for coal and natural gas. Their support for the emergency auction reflects alignment with energy preferences, not just cost concerns.

These regional variations matter because they affect what the emergency auction actually produces. If Democratic governors insist on renewable procurement preferences, auction design looks different than if Republican governors prioritize fossil fuels. If all states have to agree on auction design, compromise outcomes emerge. If states pursue separate mechanisms, coordination fails and outcomes are inefficient.

There's also the question of transmission. Virginia's data centers need power, but some of that power might be more efficiently generated elsewhere. A coal plant in West Virginia or a wind farm in Iowa could potentially serve Virginia data centers if transmission is upgraded. But transmission crosses multiple state boundaries and requires coordination among different regulators and utilities. The emergency auction doesn't automatically solve transmission challenges.

The Climate and Environmental Implications

The emergency auction sits at the intersection of several environmental concerns: climate change, air quality, water use, land use, and grid resilience. Understanding these implications helps clarify what outcomes the proposal would actually produce.

From a climate perspective, the key question is what energy sources fund new power plants. A natural gas plant operating for 30-40 years locks in fossil fuel generation for that entire period. A coal plant is even worse from a climate standpoint. Renewable energy avoids carbon emissions entirely but might be economically less attractive in a simple competitive auction.

Here's where the Trump administration's stated preferences become important. The administration has signaled support for fossil fuels and skepticism toward renewable energy expansion. While the administration doesn't directly control PJM auctions, it can influence outcomes through policy (setting energy preferences), funding (providing loan guarantees for some technologies), and rhetoric (making fossil fuels attractive politically). If the emergency auction takes place under administration pressure that favors fossil fuels, the result might be a bunch of new natural gas plants built rapidly.

This creates a climate problem if it locks in fossil fuel for decades. On the other hand, natural gas is considerably cleaner than coal (lower carbon emissions per megawatt, cleaner air quality impacts). And if the alternative is letting electricity constraints drive up costs and slow data center development, the climate calculus might favor natural gas plants as the lesser evil compared to no new generation.

There's also the water use question. Coal plants and nuclear plants are water-intensive, using enormous quantities for cooling. Natural gas plants are less water-intensive. In the Mid-Atlantic region, water availability is generally good, so this isn't a binding constraint like it is in Western states. But it's still relevant for environmental impact assessment.

Air quality impacts of new power generation matter for public health. Fossil fuel plants emit sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulates. Modern facilities have pollution control equipment, but emissions still occur. Coal plants are worst for air quality, natural gas plants better. Wind and solar have no direct air quality impacts. If the emergency auction funds new fossil fuel plants, it produces local air quality degradation in areas where plants are sited. This is particularly concerning in environmental justice contexts where power plants are often sited in or near low-income communities.

Land use is another consideration. A solar farm requires significant land area. A wind farm even more. A natural gas plant is more compact. In densely populated regions like the Mid-Atlantic, land constraints are real. This argues for denser energy sources (nuclear, gas) over more dispersed renewable sources, at least for new generation funded through emergency auctions.

From a grid resilience perspective, distributed renewable generation (lots of solar panels and wind turbines across a wide area) provides some advantages: it's harder to disrupt, reduces transmission congestion by generating power closer to demand. Centralized generation (large power plants) is more efficient but creates vulnerabilities if disrupted. This debate has been ongoing in energy policy for years without clear resolution.

The climate implications ultimately depend on auction design and which technologies win. There's nothing inherent to the emergency auction concept that requires fossil fuels or prohibits renewables. If auction rules are neutral and prices reflect long-term carbon risks (through carbon pricing or clean energy mandates), renewable sources could win. If fossil fuels are privileged or external carbon costs are ignored, fossil fuels win. The outcome depends on how the auction is structured, not just that it happens.

Long-Term Implications for Grid Structure and Reliability

Beyond the immediate question of whether new power plants get built, the emergency auction proposal has implications for how electricity grids are structured and operated long-term.

Traditional electricity grids operated by regulated utilities had a relatively clear structure: utilities owned generation, transmission, and distribution assets. They were obligated to serve all customers at approved rates. This structure provided stability and made it easy to plan infrastructure expansion. The disadvantage was cost inefficiency—utilities had incentives to over-invest in capital-intensive infrastructure (rate-of-return regulation rewards capital investment).

Competitive electricity markets, which PJM represents, separate generation from transmission. Independent power producers compete to provide generation. Transmission is owned and operated by independent system operators. This structure provides efficiency incentives but requires careful balancing of supply and demand. It also creates coordination challenges when new infrastructure is needed.

The emergency auction, if implemented, would represent a hybrid approach: using competitive market mechanisms (auctions) but with government direction about desired outcomes (new generation) and potentially with cost-shifting that distorts market prices. If successful, this could become a template for other regions and other infrastructure needs.

If it fails—if the emergency auction produces insufficient new generation, or produces power that comes online too late, or causes companies to relocate elsewhere—it could discredit competitive market mechanisms and push policy back toward traditional utility regulation. Regulators might conclude that markets can't meet infrastructure needs and move toward mandated utility investment and cost-of-service regulation.

There's also a question about how this affects future industrial development. If the emergency auction successfully shifts costs to data centers, does the same principle apply to other energy-intensive industries? Bitcoin mining is also extremely energy-intensive. Other AI applications might be as well. Should they also bear the cost of infrastructure expansion? If so, how high do costs get before these industries relocate?

From a long-term grid perspective, the key challenge is that electricity demand is becoming concentrated in specific locations due to data centers, while generation is increasingly expected to be distributed (renewables, rooftop solar, individual storage). This fundamental mismatch drives infrastructure investment needs. The emergency auction is one way to address it. But the deeper issue persists regardless. Eventually, grids might need to be completely restructured to move power efficiently across the continent, not just within regional markets.

That restructuring would require massive investment in high-voltage transmission, smart grid technologies, and energy storage. It would take decades and cost hundreds of billions of dollars. The emergency auction is a tiny step toward addressing this, not a complete solution.

Corporate Strategy and Competitive Advantage

The emergency auction proposal also affects corporate strategy for companies operating data centers, beyond just immediate cost implications.

Companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are competing intensely in cloud computing and AI services. Power availability and cost are major competitive factors. A company with cheaper, more reliable power can offer better prices and performance. This creates strong incentives to secure favorable power arrangements.

When the Trump administration and governors propose an emergency auction, they're essentially negotiating against tech companies. The implicit message is: "We control access to the power infrastructure your business depends on. You'll share the cost of expanding it." This is a real negotiating point. Tech companies can't easily relocate their existing Virginia data centers, but they can choose where to build new facilities.

Facing this negotiation, tech companies have several strategic options. First, they can participate in the emergency auction. Fund new power plants. Accept higher power costs as a business expense. Possibly secure favorable long-term pricing in return for funding. Second, they can invest in their own generation. Build solar farms, fund wind projects, or restart nuclear plants (Microsoft's Three Mile Island move). This gives them power independence but requires massive capital investment. Third, they can relocate new development to regions with more favorable power costs. Reduce concentration in Virginia and the Mid-Atlantic, spread facilities across the country or overseas. Fourth, they can lobby against the emergency auction, arguing that it's unfair, uncompetitive, or harmful to innovation. Try to influence policy in their favor.

We're already seeing combinations of all these strategies. Microsoft moved decisively into nuclear power. Amazon has been expanding diversely across regions. Google is investing in renewable energy. All three are lobbying on energy policy. None of them are exclusively dependent on any single strategy.

This competitive dynamic affects what happens with the emergency auction. If only one or two companies participate, others gain competitive advantages by locating elsewhere or funding their own power. This creates an arms race dynamic where companies increasingly decouple from public grid infrastructure and operate independently. From a societal perspective, this might be efficient (companies bear the costs of their infrastructure). From a grid resilience perspective, it's problematic (critical infrastructure becomes privatized and fragmented).

The outcome likely involves a combination. Some companies participate in auctions and pay for new generation. Others build their own power infrastructure. Over time, the grid becomes increasingly two-tiered: corporate microgrids serving major industrial users, and public grids serving everyone else. This matches the trajectory in other industries where large players operate independently while smaller players remain connected to public infrastructure.

Potential Outcomes and Scenarios

Looking forward, several plausible scenarios could emerge from the emergency auction proposal:

Scenario 1: Emergency Auction Succeeds: PJM agrees to implement the mechanism. Developers bid aggressively for long-term contracts. $10-15 billion in new generation gets funded, mostly natural gas plants with some renewable energy. Power comes online over 2-3 years. Data center demand continues growing but is met by new supply. Electricity costs stabilize. Tech companies pay premium prices but secure power for expansion. Regular consumers see bill increases moderate. This is the success case, from the administration and governors' perspective.

Scenario 2: Auction Produces Unintended Consequences: The emergency auction launches but produces mostly fossil fuel generation (contrary to some governors' climate goals). Or the costs to data centers are higher than expected, driving relocation to other regions. Or the auction becomes politically controversial and faces legal challenges. Implementation delays drag on. By the time new plants come online, some data centers have already relocated. The infrastructure gets partially built but ends up stranded or underutilized. This is the moderate failure case.

Scenario 3: Tech Companies Opt Out: Rather than participating in the emergency auction or accepting high grid power costs, major tech companies accelerate private generation investments. They develop sufficient on-site and contracted renewable capacity to meet their own needs. They operate as independent microgrids. The public grid continues experiencing shortages for other customers. The emergency auction fails to address the underlying problem because the largest power consumers have exited the public market. This is the privatization outcome.

Scenario 4: Regulatory Obstacles Block Implementation: PJM resists the emergency auction, arguing it's outside their authority or creates market distortions. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission doesn't approve new tariffs required to implement it. Legal challenges slow progress. The emergency auction never actually launches or only launches in a limited form. Power constraints in the Mid-Atlantic persist, driving continued price increases. Data center development in the region slows. This is the policy failure scenario.

Scenario 5: Broader Policy Shift: The emergency auction becomes a template for addressing infrastructure bottlenecks in other sectors. Governments use similar approaches to fund electric vehicle charging networks, broadband infrastructure, semiconductor manufacturing facilities. This approach becomes the standard for public-private infrastructure partnerships. If successful, it resolves multiple infrastructure challenges simultaneously. If problematic, it creates systematic distortions across multiple industries.

Which scenario actually emerges depends on factors beyond anyone's complete control: tech company financial positions and strategic priorities, PJM's institutional willingness and capacity, FERC's regulatory judgment, political dynamics and public opinion about data centers and electricity costs, and technological developments in power generation and grid management.

The most likely outcome probably combines elements of multiple scenarios. The emergency auction probably does launch in some form, attracting some bidders. But tech companies also continue diversifying energy sourcing. The result is partial success: some new generation gets built through the auction, meeting some of the growing demand, while corporations also supply part of their own power needs. This muddled outcome solves the problem incompletely but reduces the political pressure to implement more dramatic changes.

FAQ

What exactly is the emergency power auction being proposed?

The Trump administration and bipartisan governors are urging the PJM Interconnection (the largest electricity grid operator in the U. S.) to hold an "emergency auction" where data center operators can purchase 15-year power contracts. These long-term contracts would give power plant developers the revenue certainty needed to justify building billions of dollars in new generation capacity quickly. The Department of Energy estimates this approach could trigger $15 billion in new power plant construction.

Who is pushing for the emergency auction and why?

The Trump administration, led by Secretary of Interior Doug Burgum and Secretary of Energy Chris Wright, is pushing for the auction to address surging electricity demand from AI data centers. Democratic governors like Pennsylvania's Josh Shapiro and Maryland's Wes Moore also signed on because their constituents are experiencing rising electricity bills as data center power demand competes with residential and business customers for limited grid capacity. The proposal unites these normally partisan opponents around the principle that data centers, as the largest drivers of new power demand, should fund the infrastructure expansion they require.

How does PJM Interconnection work and why is it important?

PJM operates the largest competitive electricity market in the United States, covering 13 states across the Midwest and Atlantic regions and serving about 65 million people. Rather than a traditional utility owning all generation and distribution, PJM operates as an independent system operator managing a marketplace where power generators bid to sell electricity. PJM's decisions about market rules and capacity mechanisms directly affect whether new power plants get built and how much electricity costs for everyone in the region.

Why do data centers need so much electricity and why is this a new problem?

Data centers powering AI models, cloud computing, and other digital services are extraordinarily energy-intensive. A single large data center can consume as much electricity as a city of 80,000 homes, running 24/7. This is a new problem because AI adoption has accelerated dramatically in the last 2-3 years, creating explosive electricity demand that traditional grid planning never anticipated. Virginia, the nation's data center hub, has seen electricity demand growth rates of 10-15 percent annually, compared to historical trends of 2-3 percent, straining existing infrastructure.

What would happen to electricity costs if the emergency auction succeeds?

If the auction successfully attracts billions in new power plant investment, electricity supply would increase and prices should eventually stabilize or decline, at least preventing further rapid increases. However, data center operators would pay premium prices for long-term contracts (potentially 20-30 percent higher than standard rates), and these higher costs would be passed through to customers using cloud services, AI tools, and other data center-dependent services. Regular residential electricity bills might increase more slowly than they otherwise would, since they wouldn't absorb the full cost of infrastructure expansion.

Can power plants actually be built fast enough to matter?

Natural gas plants can be built in 18-36 months once financing is arranged, making them the only realistic option for an "emergency" timeline. Coal plants take 5-7 years and nuclear takes 10-15 years, so these aren't viable emergency solutions. Renewable energy (wind and solar) can be built in 18-24 months but requires specialized permitting and interconnection work. Given these timelines, emergency auction proceeds would likely fund mostly natural gas plants, even though the Trump administration has stated preferences for coal and skepticism toward renewables.

What would tech companies do if grid power becomes too expensive?

Major tech companies like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon are already building their own power sources through renewable energy purchase agreements, nuclear plant investments, and other mechanisms. If grid power costs become prohibitively expensive due to emergency auction cost-shifting, these companies would accelerate private generation investments and operate increasingly independent microgrids. This would solve their power problem but would weaken the public grid, potentially leaving residential and small business customers with inadequate power infrastructure.

Could the emergency auction backfire and drive data centers out of the region?

Yes, this is a genuine risk. If the auction dramatically raises power costs in the PJM region, new data center development might shift to other regions like Texas, Iowa, or international locations with lower electricity costs. This would reduce the infrastructure pressure in Virginia and the Mid-Atlantic but would also reduce economic development benefits and potentially strand power plants built through the auction. The emergency auction succeeds only if costs don't rise so high that companies relocate entirely.

How does this relate to climate goals and clean energy?

The outcome depends entirely on auction design. If rules favor renewable energy or include carbon pricing mechanisms, the auction could drive wind and solar investment. If auction rules are neutral or if fossil fuels are politically privileged, the auction would fund natural gas or coal plants, locking in fossil fuel generation for 30-40 years. Some Democratic governors supporting the emergency auction have clean energy commitments that could conflict with fossil fuel plant construction, creating tensions about what the auction actually produces.

Is there precedent for using auctions to solve infrastructure problems like this?

Yes, several precedents exist. Some states have run successful renewable energy auctions to meet clean energy goals. Tech companies have negotiated directly with utilities and power operators for dedicated generation (Microsoft's Three Mile Island deal being the most prominent example). However, this specific model—a government-urged emergency auction specifically targeting data center power demand cost-shifting—is relatively novel and hasn't been tested at this scale in the electricity market.

What happens if PJM refuses to implement the emergency auction?

If PJM refuses, the Trump administration and governors lack direct authority to force implementation. PJM operates under Federal Energy Regulatory Commission oversight and must maintain market neutrality. The administration could pressure FERC to compel changes or could push for new legislation, but this would take months or years. Without regulatory support, the emergency auction simply doesn't happen, and power constraints in the region persist, driven by whatever cost curves and investment decisions emerge through existing market mechanisms.

Conclusion: The Stakes and Uncertainties Ahead

The emergency auction proposal represents a genuine attempt by government and industry to solve a real problem: electricity grids designed for a world that no longer exists are suddenly confronting power demands they were never built to serve. The growth of data centers and AI services has created infrastructure challenges that traditional market mechanisms haven't addressed quickly or efficiently enough. When electricity bills start rising 20-30 percent annually, and when some businesses report years-long waiting periods just to connect to the grid, something clearly needs to change.

What's remarkable about this moment is the bipartisan political alignment. Trump administration officials and Democratic governors, who disagree on nearly everything else, united around the principle that data centers should fund the infrastructure expansion they require. This isn't political theater—it reflects genuine constituent pressure. People are angry about rising electricity costs, and they don't care that the cost increases reflect AI data center expansion. They just want energy to be affordable.

But the elegant logic of the emergency auction—align incentives, use market mechanisms, make the beneficiaries of new infrastructure fund it—confronts complex realities about how electricity systems actually work, how corporations actually make decisions, and how political systems actually function. The timeline challenges alone are substantial. Even if the auction launches tomorrow, the new power plants won't come online for 2-3 years. During those years, costs remain elevated, shortages persist, and companies make location decisions that might be irreversible.

The technology question also matters immensely. If the auction funds natural gas plants as the fastest option, it locks in fossil fuel generation for decades, potentially conflicting with climate goals. If it funds renewables, it might cost more or take longer to build. These technology choices affect not just the emergency auction but the entire energy trajectory for the region.

Perhaps most importantly, the emergency auction addresses a symptom rather than the underlying structural problem: electricity grids designed for distributed consumption (millions of homes and businesses each using modest amounts of power) are trying to accommodate concentrated, massive consumption (data centers using as much as a city). This structural mismatch will persist regardless of whether the emergency auction succeeds. It might lead to more private power generation, more corporate energy independence, and a two-tiered system where major industrial consumers operate independent microgrids while smaller consumers rely on public infrastructure.

What happens next will depend on negotiations between PJM, the Trump administration, state governors, tech companies, and FERC. It will depend on technical feasibility of building power plants on emergency timelines. It will depend on whether auction designs favor fossil fuels or renewables. It will depend on whether tech companies participate or opt for independent power solutions. And it will depend on what regular people prioritize: affordable electricity, clean energy, or rapid AI development. These aren't easy choices, and the emergency auction forces them into the open.

One thing seems certain: the current situation is unsustainable. Data center demand will keep growing. Electricity grids must expand to meet it. The question is how that expansion happens, who pays for it, and whether the approach creates sustainable, efficient infrastructure or just shifts problems around. The emergency auction is one answer to that question. Whether it's the right answer will become clear only as it gets implemented, tested, and refined.

The stakes are high, not just for electricity rates but for the future of American infrastructure, energy policy, and the competitive position of tech companies as AI capabilities become increasingly central to global competition. The outcome will likely be messier and more complicated than either the proposal's advocates or critics expect. That's how most major infrastructure challenges resolve themselves in practice.

Key Takeaways

- Trump administration and bipartisan governors are urging an emergency power auction to make data centers fund new infrastructure

- AI data centers consume electricity equivalent to entire cities, creating unprecedented grid demand concentrated in Virginia

- The proposed 15-year contracts aim to provide revenue certainty for $15 billion in new power plant construction

- Natural gas is the only realistic energy source for emergency timelines, creating tension with stated fossil fuel preferences

- Tech companies can opt out by building private power infrastructure, potentially creating a two-tiered grid system

- PJM Interconnection ultimately controls implementation and was not invited to the policy announcement

- Regional differences in climate goals and energy preferences create conflicts between participating governors

- Success depends on balancing cost-shifting that doesn't drive data centers to relocate while funding infrastructure quickly enough

Related Articles

- Type One Energy Raises $87M: Inside the Stellarator Revolution [2025]

- Microsoft's Community-First Data Centers: Who Really Pays for AI Infrastructure [2025]

- Microsoft's $0 Power Cost Pledge: What It Means for AI Infrastructure [2025]

- Meta's Nuclear Bet With Oklo: Why Tech Giants Are Fueling the Energy Revolution [2025]

- Meta's Nuclear Energy Deal with TerraPower: The AI Power Crisis [2025]

- Why RAM Prices Are Skyrocketing: AI Demand Reshapes Memory Markets [2025]

![Trump and Governors Push Tech Giants to Fund Power Plants for AI [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/trump-and-governors-push-tech-giants-to-fund-power-plants-fo/image-1-1768597769329.jpg)