Introduction: The Memory Market Is Broken (And It's Making Billions)

There's a strange disconnect happening in tech right now. Memory manufacturers are celebrating record profits—we're talking billions of dollars—while anyone trying to buy RAM for a PC is watching prices triple overnight. A 32GB DDR5 kit that cost

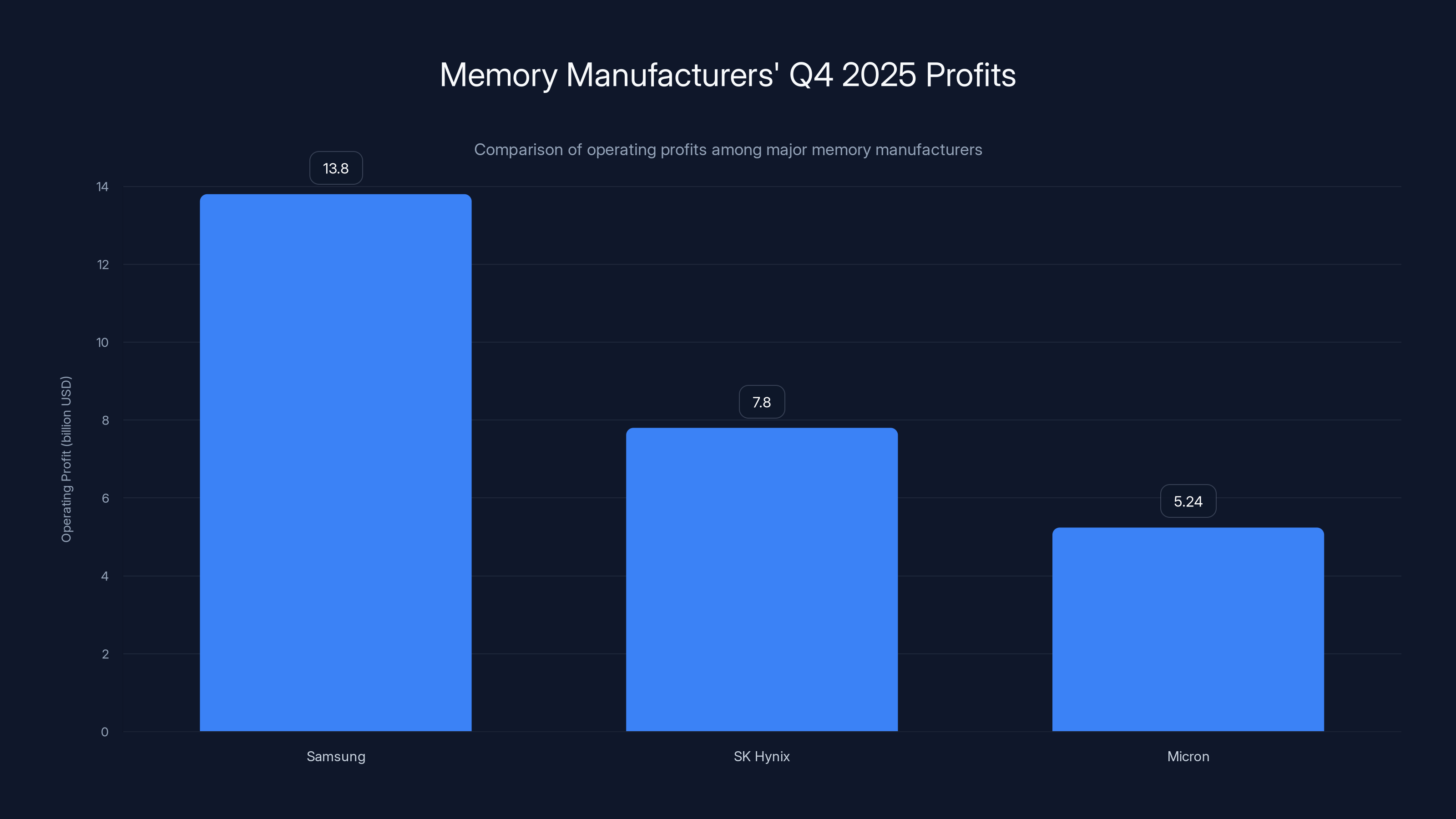

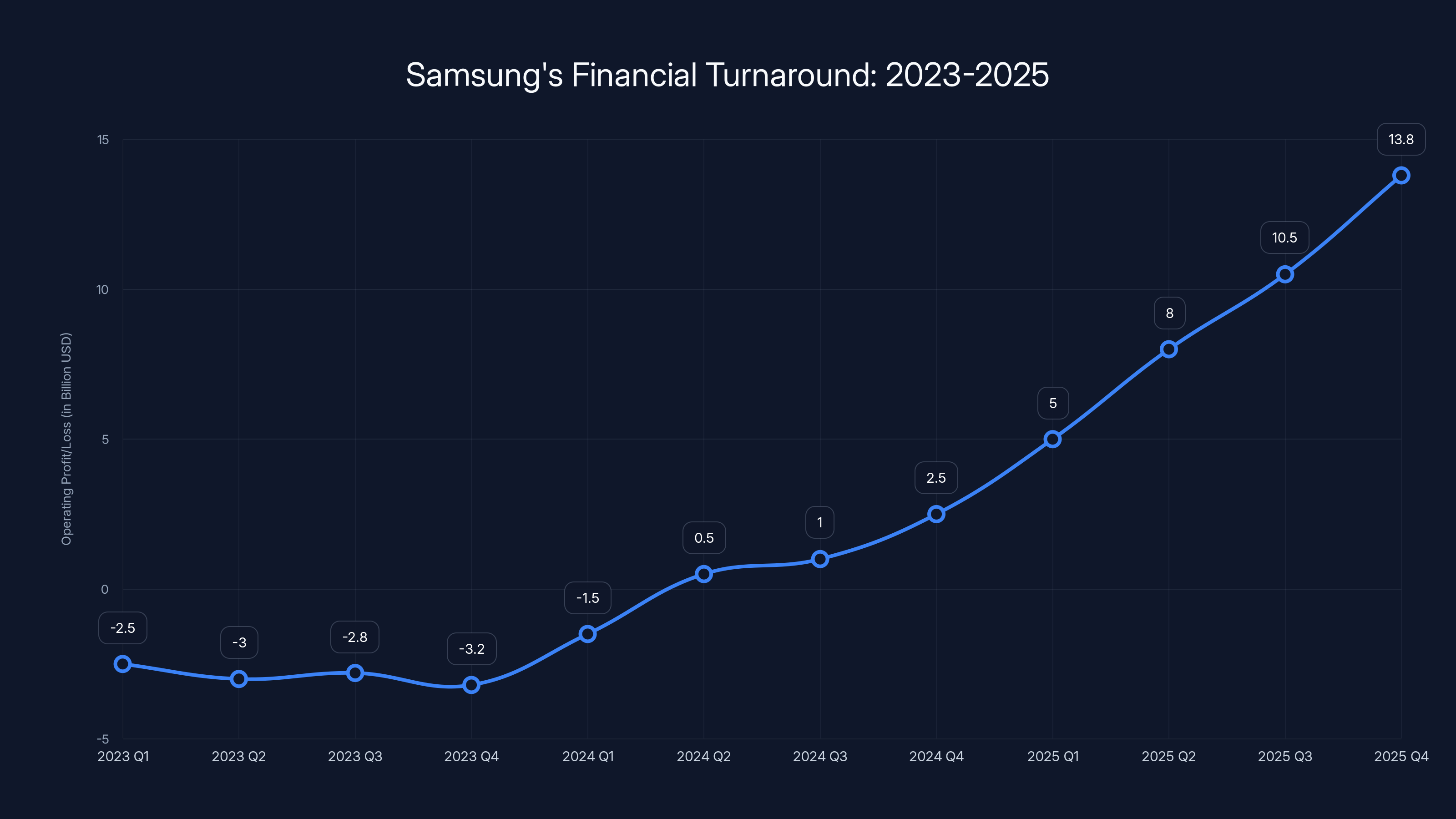

Samsung just announced operating profits of roughly

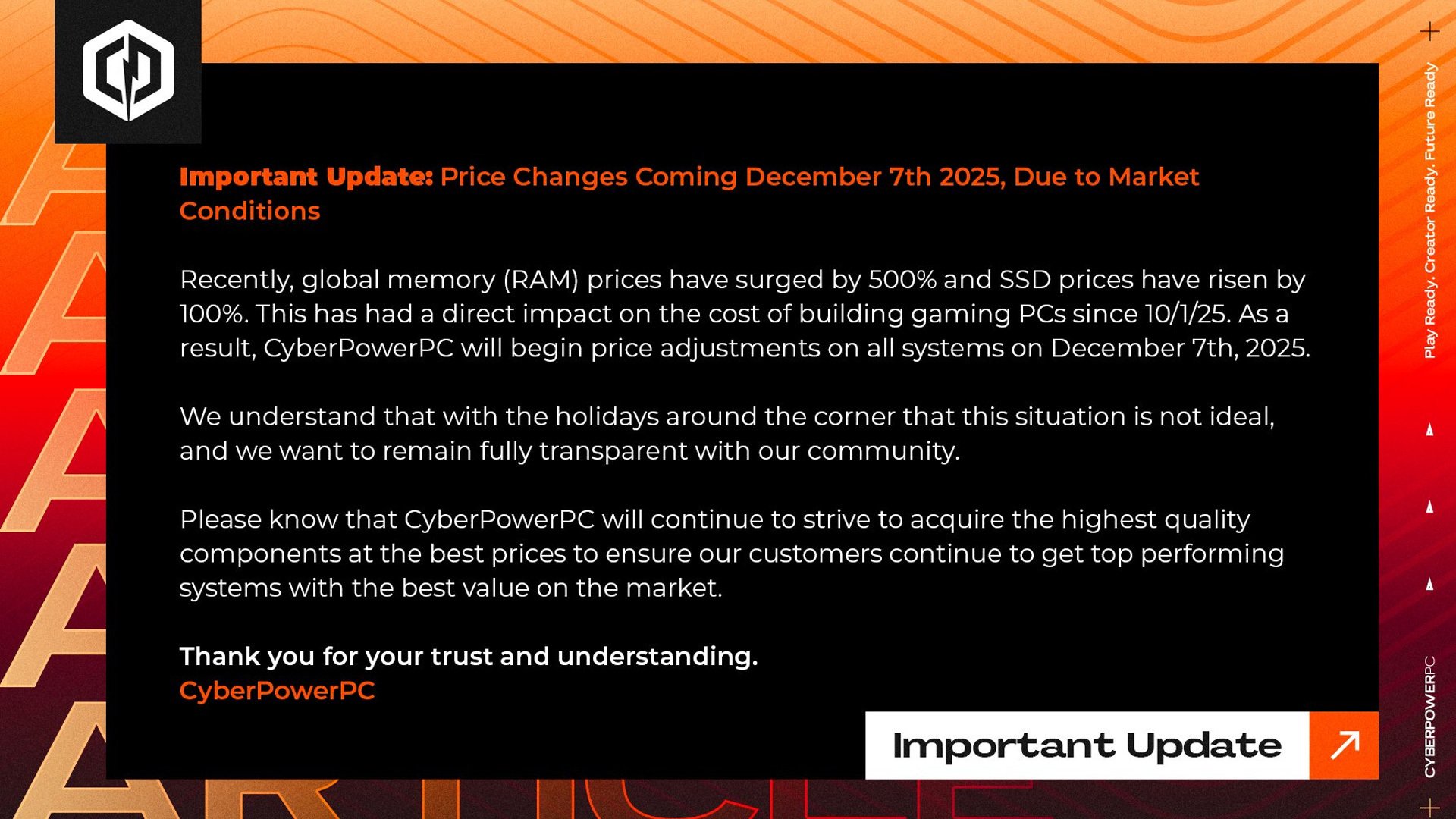

But here's the thing nobody talks about: PC builders and everyday consumers are getting absolutely crushed. This isn't a temporary shortage. The AI industry's appetite for memory is so enormous that analysts are predicting price increases of 33 percent throughout 2026. We could be looking at elevated prices for years, not months.

What we're witnessing is a fundamental collision between two different worlds. On one side, you have the traditional computing market—laptops, desktops, gaming rigs, consumer devices. On the other side, you have the AI infrastructure boom, where companies are building data centers that consume more RAM than entire countries. The AI side is winning, and it's rewriting the entire economics of the memory industry.

This isn't just about price hikes at Newegg. It's about how the infrastructure race for artificial intelligence is reshaping global supply chains, economic margins, and what's actually possible to build right now. Understanding what's happening requires looking at the specific technical constraints that make HBM chips so voracious, the scale of AI companies' infrastructure spending, and the math that's forcing manufacturers to choose between serving the consumer market or the AI market.

Let's break down exactly why memory makers are printing money while everyone else is suffering.

The AI Data Center Boom: An Insatiable Appetite for Memory

When OpenAI, Google, Meta, and Microsoft decided that training massive AI models was worth hundreds of billions of dollars, they didn't just buy a few extra servers. They're building infrastructure at scales that didn't exist a few years ago.

Consider this: OpenAI's internal codename "Stargate" is a data center project so large that analysts estimate it could consume as much as 40 percent of the world's entire DRAM output by itself. Let that sink in. One company's infrastructure project could use two out of every five RAM chips manufactured globally. That's not demand. That's domination.

These aren't small deployments either. A single AI data center might contain hundreds of thousands of GPUs, each one needing serious amounts of high-bandwidth memory to function. Nvidia's latest H100 and H200 GPUs are designed to work with HBM chips that provide much faster data access than traditional DRAM. When you're training models on trillions of parameters, that bandwidth matters. It saves weeks of computation time.

The scale is genuinely hard to wrap your head around. In 2023, AI infrastructure spending was maybe a niche market. Today, it's the dominant force reshaping entire manufacturing ecosystems. Every major cloud provider—Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Meta—is racing to build more capacity. And each one needs exponentially more memory than traditional data centers did.

Here's what makes it worse: these aren't one-time purchases. These data centers are being built right now, and they'll be replaced or upgraded within a few years as models get better and demand grows. The AI boom isn't a one-year phenomenon. It's a multi-year infrastructure wave that's going to keep pulling memory away from consumer markets.

Memory manufacturers know this. They're not complaining about the situation. They're expanding production capacity, shifting factories to focus on HBM and enterprise DRAM instead of consumer products, and locking in long-term contracts with major cloud providers. From a business perspective, it makes perfect sense. Sell to one customer for a billion dollars or sell to thousands of customers for the same total revenue? The choice is obvious.

Samsung leads with $13.8 billion in operating profit for Q4 2025, followed by SK Hynix and Micron, highlighting the profitability of the memory market despite consumer price hikes.

HBM vs. DRAM: The Space Problem That's Killing RAM Availability

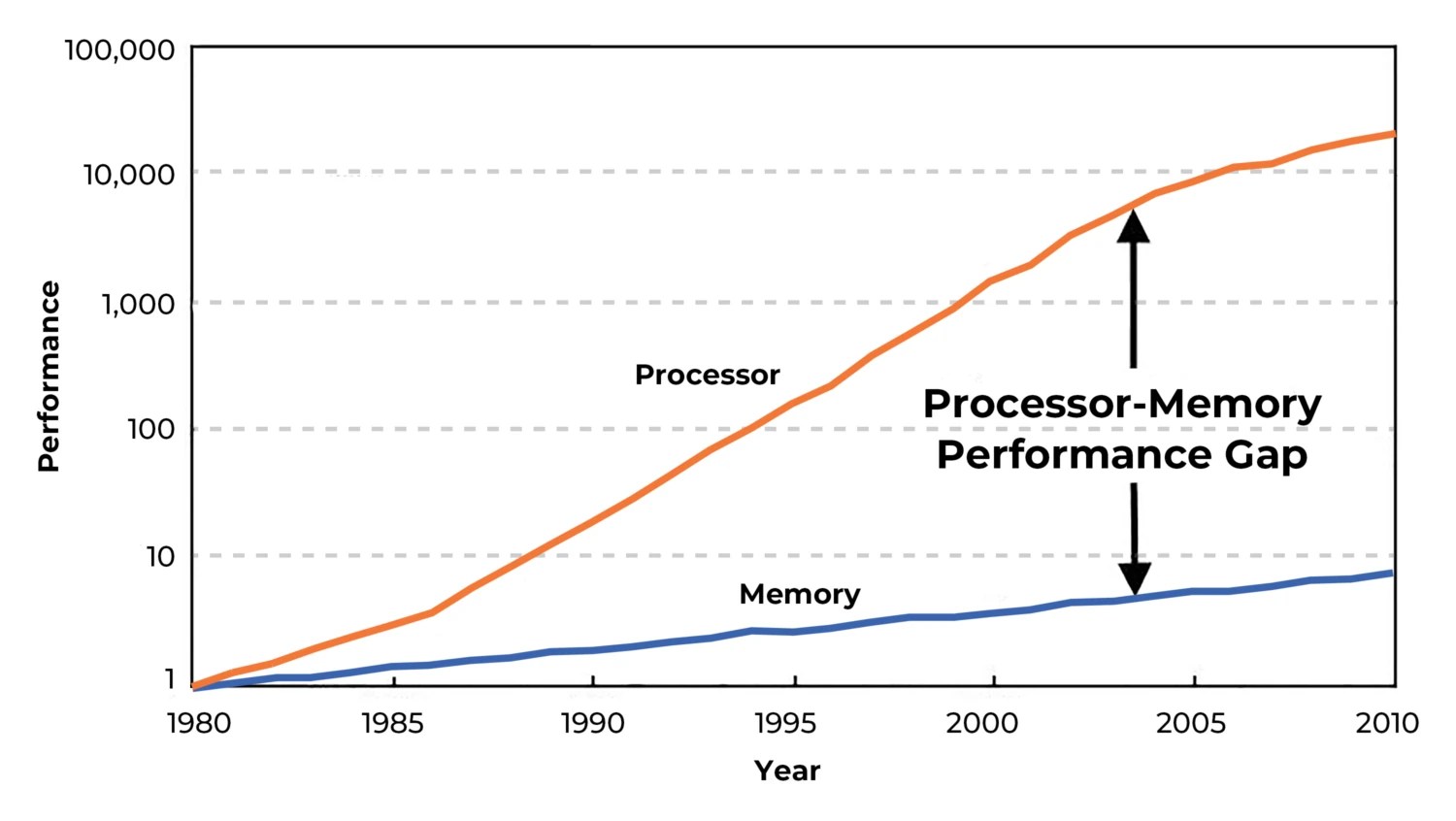

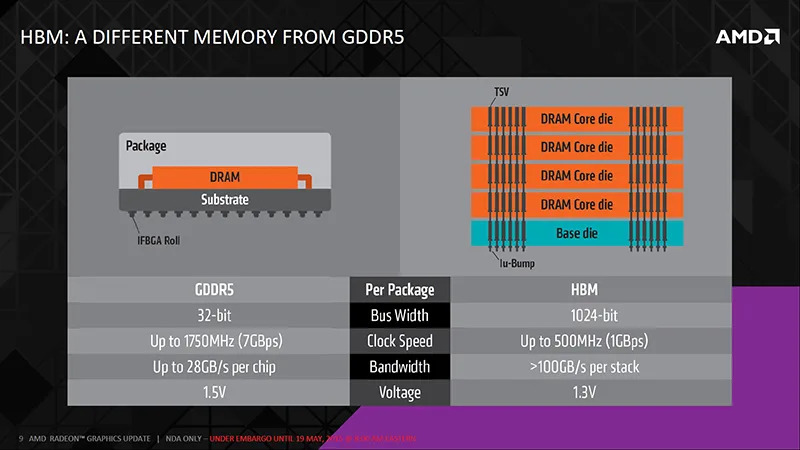

Here's where the technical details create an economic catastrophe for consumers. HBM (high-bandwidth memory) and traditional DRAM aren't equivalent products. They're not interchangeable. And crucially, they take up very different amounts of space on a manufacturing wafer.

When a memory manufacturer is deciding what to produce in their fabrication plants, they're working with a fixed amount of production capacity. Think of a wafer fab as a resource-constrained factory. You can make either HBM or DRAM with the equipment, but you can't do both simultaneously with the same silicon real estate.

Here's the problem: HBM uses about three times as much silicon wafer space as the equivalent amount of standard DDR5 DRAM. This isn't arbitrary. HBM needs that extra space because it's architecturally different. The bandwidth requirements demand specific layouts and construction techniques that simply take up more room.

So when a manufacturer says "we're shifting 50 percent of our production to HBM," what they're actually saying is "we're reducing our DRAM output by much more than 50 percent." If you shift half your wafer capacity to HBM, you might only reduce total DRAM production by 30 percent because of how much more efficiently you can pack standard DRAM into the remaining wafer space. But that's still a massive reduction in DRAM availability.

Compound this problem with the fact that consumer DRAM is the lowest-margin product these manufacturers make. When you're dealing with thin margins on commodity DRAM and huge margins on enterprise HBM for AI systems, there's no financial incentive to keep producing consumer RAM. The numbers don't work.

Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron are all making this same calculation independently, and they're reaching the same conclusion: shift to HBM, enterprise DRAM for data centers, and let the consumer market fend for itself. Micron was so honest about this that they literally announced they're exiting the consumer RAM market entirely. They're keeping their enterprise business but abandoning retail products that can't command the same prices as AI-grade memory.

DDR5-6000 RAM prices surged from

Competing With Open AI: Why Consumers Lost the Memory Market

Let's be honest about what's actually happening here. Consumers aren't just competing for RAM. They're competing with companies that have infinite budgets, venture capital backing, and the willingness to pay whatever it takes to build faster.

When you go to buy DDR5 RAM for your gaming PC, you're bidding against OpenAI, which just secured

These companies don't care about $10 price swings. They care about getting the hardware they need on schedule. If a memory manufacturer can't deliver 10,000 units of HBM3 in the next quarter, that's millions of dollars in delayed AI training that could cost them market position.

Consumers, by contrast, are highly price-sensitive. A $100 difference on a RAM purchase is genuinely significant. This creates a strange market dynamic where the highest bidders (tech giants) get the product, and everyone else either waits, pays inflated prices, or doesn't upgrade at all.

Memory manufacturers love this situation. They get to sell virtually everything they make at premium prices to tier-one customers with signed contracts. There's no inventory risk. There's no negotiation. Supply goes to whoever contracted for it, and if there are scraps left over for the consumer market, they sell those at whatever price clears the market.

And here's the kicker: memory manufacturers have zero incentive to fix this. If they built extra consumer DRAM capacity, they'd dilute their margins on consumer products while cannibalizing HBM production that commands 3-5x the per-unit profit. From a pure financial perspective, the consumer market is a distraction from their actual business now.

The Price Explosion: How 340

A 32GB DDR5-6000 kit dropped from

Several factors contributed to this explosion. First, shortage psychology kicked in. When people heard that RAM was hard to get, they panicked-bought. This created artificial demand spikes that drove prices even higher. Scalpers got involved, buying up inventory specifically to resell at inflated prices. This happens in every shortage, and it amplifies the problem.

But the underlying issue is supply constraint combined with demand from enterprise buyers who aren't price-sensitive. Manufacturers can produce X amount of memory per month. AI companies are contractually guaranteed most of that X. What's left trickles into retail channels. With scarce supply, prices spike to whatever consumers will actually pay.

Bank of America analysts predict DRAM average selling prices will increase another 33 percent throughout 2026. Let that sink in. Prices aren't leveling off. They're expected to keep rising for another full year.

This creates a cascade effect. When RAM is expensive, PC builders hesitate. OEMs hesitate. This reduces total volume demand from the consumer side, which further justifies manufacturers not bothering with consumer production. The market is bifurcating into a premium tier (AI infrastructure) and a struggling tier (everyone else).

HBM has a significantly higher average selling price (

Supply Chain Math: Why Production Can't Catch Up

You might think the obvious solution is for memory manufacturers to just build more fabrication plants. Fire up the capital equipment, hire the engineers, and pump out more RAM. Problem solved, right?

This is where semiconductor economics destroy that intuition.

Building a new memory fab doesn't happen in months. It takes 3-5 years from planning to production. You're talking about multi-billion-dollar capital expenditures, environmental certifications, hiring and training thousands of specialized technicians, and installing equipment that costs tens of millions of dollars per individual machine.

By the time a new fab comes online in 2028 or 2029, the AI infrastructure buildout might be well past its peak. Or it might still be accelerating. Nobody actually knows. The forecasting problem is genuinely hard.

Plus, why would a memory manufacturer invest in new consumer DRAM capacity when the margins are terrible and the market is cyclical? They'd rather invest in building enterprise DRAM fabs or expanding HBM production. The returns are better, and the customer base is more stable.

This is classic capital allocation. Smart companies don't build capacity for soft markets. They build for high-margin, growing markets. Right now, that's enterprise AI memory, not consumer DDR5.

Existing fabs are operating at maximum capacity. There's no idle production sitting around waiting to be activated. The equipment is running 24/7. The bottleneck is physical manufacturing capacity, not demand or desire to produce more.

What manufacturers are doing instead is incrementally improving yields (getting more usable chips per wafer) and shifting process nodes. A newer process node can pack more memory into the same die space. But these improvements are incremental, not exponential. They might add 10-15 percent more output per fab, not double capacity.

The math is bleak: demand is growing faster than manufacturing capacity can possibly expand. For consumers, this means elevated prices for years until either the AI boom moderates or new fabs come online around 2028-2029.

Enterprise DRAM: The New Gold Rush

Enterprise DRAM is a completely different market from consumer DDR5. It's the memory used in traditional data center servers, and it's not experiencing the same shortage as consumer products. Here's why.

Traditional AI data centers need servers with lots of DRAM for certain workloads—inference, smaller model training, supporting infrastructure. This DRAM is in demand, certainly, but it's not as extreme as the HBM competition. Enterprise DRAM also has better margins than consumer DRAM because customers are less price-sensitive. A data center operator upgrading servers cares more about performance and compatibility than saving $50 per machine.

Memory manufacturers are happy to serve this market. The margins are better, the customers are more reliable, and the volumes are still substantial. But it's also competing with HBM for wafer capacity. When a fab has to choose between producing enterprise DRAM or HBM, the manufacturer needs to evaluate which has better margins and better long-term growth.

Currently, HBM is winning that competition decisively. The average selling price for HBM is roughly

This is exactly what SK Hynix CEO referenced when discussing their record profits. They're expanding investments in HBM and AI infrastructure memory specifically because that's where the profit growth is. Consumer DRAM is a rounding error in their financial calculations.

Samsung's operating profit saw a dramatic turnaround from significant losses in 2023 to a record profit of $13.8 billion in Q4 2025, driven by increased demand for memory products due to the AI boom. Estimated data.

Samsung's Comeback Story: From Crisis to Record Profits

Samsung's financial trajectory tells the entire story of what's happened in the memory market. In 2023, Samsung was a disaster. The company posted significant losses in its memory division because of oversupply. They had too much inventory, not enough demand, and prices were cratering.

Memory is a capital-intensive business with cyclical demand. When supply exceeds demand, manufacturers can't just stop producing. They have fabs running 24/7, massive fixed costs, and inventory that needs to go somewhere. Prices plummet. In 2023, this cycle hit Samsung hard.

But then the AI boom hit, and suddenly Samsung's massive production capacity became an asset instead of a liability. The company that overproduced in 2023 was positioned perfectly to serve the surging demand for HBM and enterprise DRAM in 2025.

Samsung's reported operating profit of roughly $13.8 billion in Q4 2025 is a stunning reversal from their 2023 losses. That's not primarily because they make better products. It's because they have production capacity and customers willing to pay premium prices.

This also reveals something important: Samsung's diversification actually helps during supply constraints. Because Samsung makes phones, displays, televisions, and consumer electronics alongside memory chips, they can allocate their best engineers and most efficient fabs to whichever product line is most profitable. They chose memory for 2025-2026, and it's working out phenomenally well.

Micron, by contrast, made a strategic choice to exit consumer products entirely. The company decided it would rather focus on high-margin enterprise and AI memory than compete in the consumer space. This is actually a smart decision given the market dynamics, but it also means consumer buyers have one fewer option when shopping for DDR5.

When Will Prices Come Down? The Analyst Predictions

Here's the uncomfortable truth: probably not for a while.

Micron's CEO Sanjay Mehrotra explicitly stated that both increased demand and constrained supply are expected "to persist beyond calendar 2026." That's corporate-speak for "you're going to be paying high prices for at least two more years."

Bank of America analysts cited by SK Hynix predict DRAM average selling prices will increase 33 percent in 2026 and then presumably stabilize at those elevated levels. Price reductions aren't expected in 2026. More increases are expected.

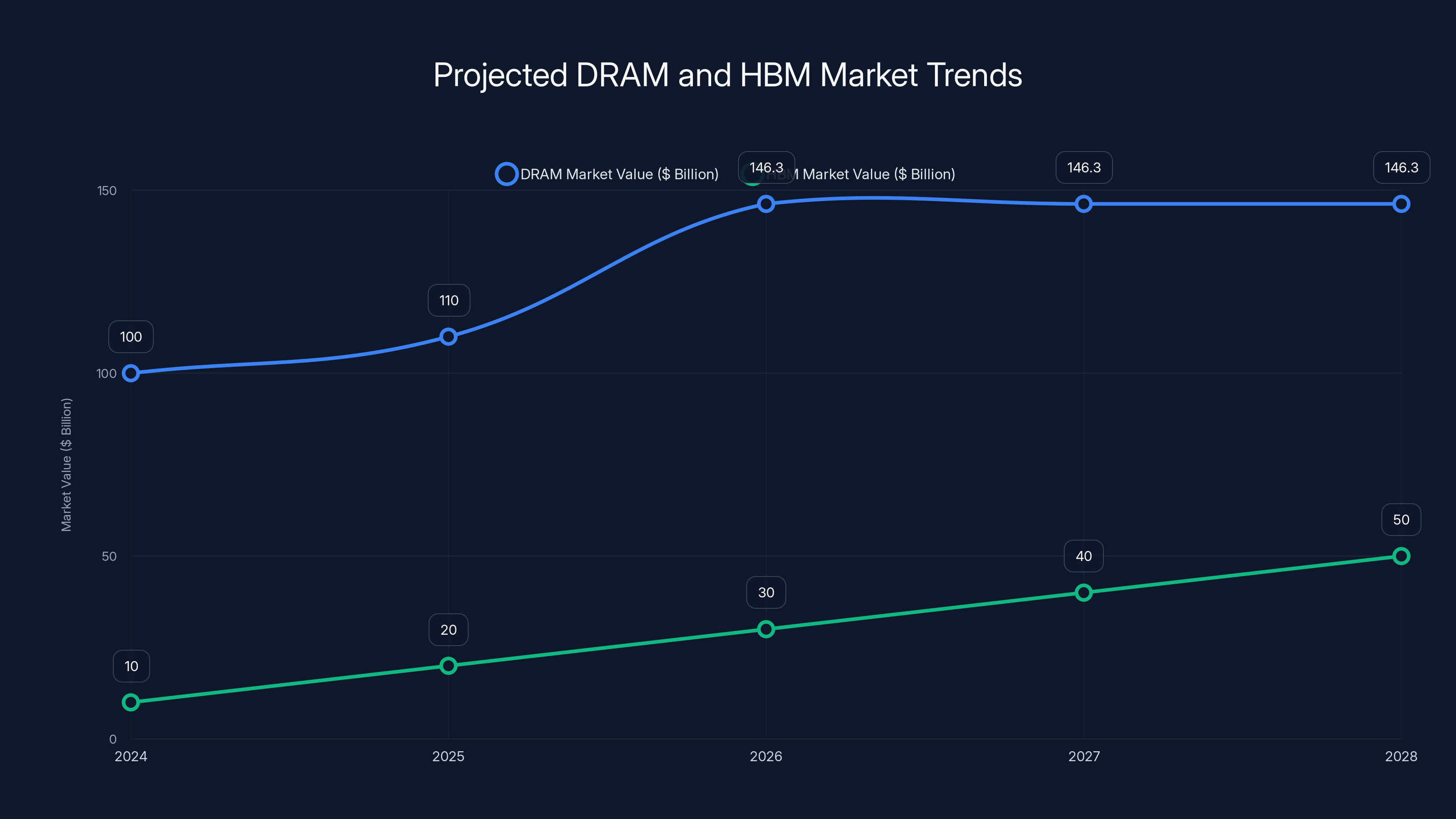

The market for HBM alone in 2028 could exceed the size of the entire RAM market in 2024. Let that inform your timeline expectations. We're looking at structural changes in the market, not temporary disruptions.

Of course, all these forecasts include a massive caveat: they assume the AI boom continues. If there's a bubble burst, if capital investment in AI infrastructure moderates, if demand flattens, everything changes.

But nobody's betting on that. Every tech company is doubling down on AI. Every VC firm is funding AI startups. Every major cloud provider is racing to build more capacity. The consensus is that this boom has years of runway left.

DRAM market value is projected to stabilize at elevated levels post-2026, while HBM is expected to grow significantly, potentially reaching $50 billion by 2028. (Estimated data)

The Scalper Problem: Why RAM Listings Disappear Instantly

If you've tried buying RAM recently, you've probably noticed that stock disappears within minutes. This isn't just legitimate customers buying quickly. There's an entire ecosystem of scalpers using bots to purchase inventory and resell it at markup prices.

Scalpers aren't the primary cause of high prices—that's all supply and demand—but they're a secondary problem that makes the situation worse. They create artificial scarcity by hoarding inventory, they waste production that could go to actual users, and they make prices even more unpredictable.

Retailers are caught in the middle. They could raise prices higher to discourage scalpers and make legitimate sales stick around longer, but that drives away regular customers. They could implement purchase limits to prevent bulk buying, but that frustrates scalpers less than you'd think—they just use multiple accounts or have friends buy for them.

The only real solution to scalping is abundant supply. When there's enough product that anyone can buy whenever they want, scalpers can't create artificial scarcity. But we're years away from that scenario in consumer RAM.

Meanwhile, scalpers are just another friction point that makes building or upgrading a PC more annoying and expensive. It's a symptom of a constrained market, not a cause. But it's worth understanding when you're scrolling through sold-out listings.

Memory for Data Centers: AI vs. Traditional Computing

Not all data center memory is equal. There are fundamentally different use cases that require different types of memory, and the allocation of that memory between AI and traditional computing is a hidden factor in consumer RAM availability.

HBM (High-Bandwidth Memory) is used exclusively in AI accelerators like Nvidia's H100 and H200 GPUs. It's expensive, specialized, and has no consumer applications whatsoever. When manufacturers produce HBM, it's not coming from inventory that could've been used for consumer DDR5.

Enterprise DRAM (typically DDR4 or DDR5) is used in traditional data center servers. This is more general-purpose than HBM but still specialized for data center applications. Most of this production isn't competing directly with consumer DDR5 because the specifications, quantities, and purchasing patterns are different.

Consumer DRAM (DDR5, DDR4) is what PC builders buy. This is where consumer demand collides with whatever trickles down from enterprise production.

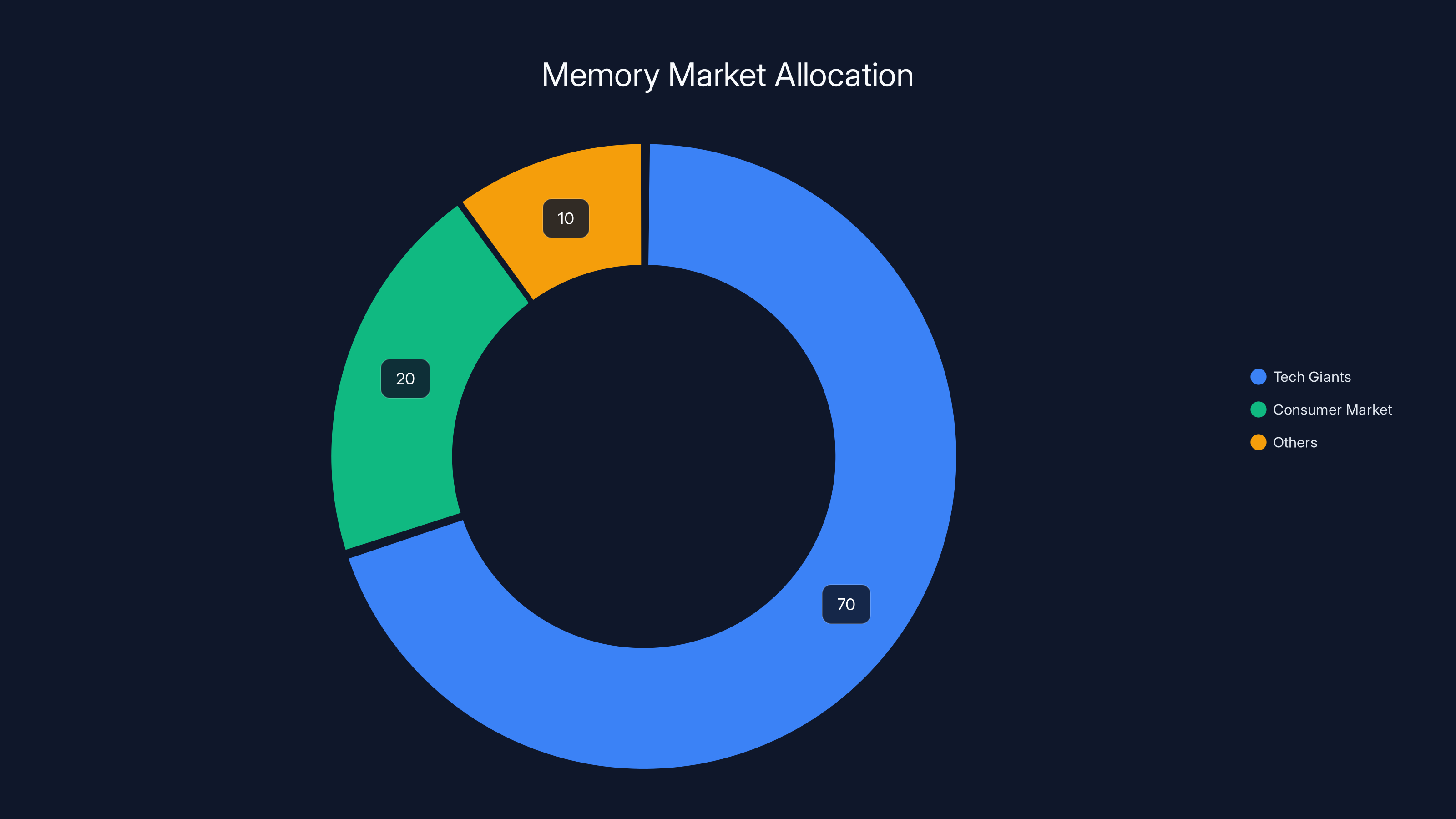

The supply chain looks roughly like this: manufacturers produce HBM, then produce enterprise DRAM with leftover capacity, and then produce consumer DRAM if there's any capacity left. This hierarchy reflects profit margins and customer power.

AI companies are contractually guaranteed their memory. Cloud providers have long-term agreements. By the time retail RAM becomes available, it's whatever manufacturers couldn't sell to premium customers at premium prices.

This explains why consumer prices spike so dramatically while enterprise customers experience relatively stable pricing. Enterprise buyers have negotiated contracts. Consumers are paying spot market prices for whatever trickles through.

Tech giants dominate the memory market, securing approximately 70% of supply, leaving consumers with limited access and higher prices. (Estimated data)

The Profit Explosion: How Margins Exploded

Let's talk about why memory manufacturers are so happy right now. It's not just revenue. It's margin expansion.

SK Hynix reported that their operating margin increased from 40 percent to 47 percent year-over-year. That's a massive margin expansion. They're not selling more units at the same prices. They're selling units at much higher prices while production costs remain relatively flat.

Here's the mechanics: memory manufacturing has high fixed costs (the fabs) and relatively low variable costs (the materials that go into each chip). When you can sell more chips per fab at higher prices, your profit per fab increases dramatically.

In 2023, Samsung lost money on memory because prices were too low to cover their fixed costs. Today, prices are so high that even incremental production from the same fabs generates enormous profit.

This is the semiconductor industry in a nutshell. Profitability is about price and capacity utilization. When demand exceeds supply, prices rise. When your fabs are running at 100 percent capacity producing high-margin products, profit margins soar.

Memory manufacturers are exploiting this perfectly. They're raising prices because they can. Enterprise customers will pay it because they need the chips. Consumers will grumble and either pay or skip upgrades. Either way, manufacturers win.

This is also unsustainable long-term. The higher prices go, the more incentive companies have to build competing fabs, invest in alternatives, or reduce memory requirements in new products. But for the next 2-3 years, these profit margins are likely to remain elevated.

The Bubble Risk: What Happens If AI Demand Moderates

Every market analysis about memory prices includes the same huge caveat: this assumes AI infrastructure demand continues growing at current rates.

What if it doesn't?

Samsung in 2023 is the perfect cautionary tale. They overestimated demand, kept producing, and suddenly found themselves with massive inventories and cratering prices. Memory manufacturers are aware of this history. They know that boom-bust cycles are part of their business model.

But right now, they're making a conscious bet that the AI boom is different. That it's not a speculative bubble like cryptocurrency or the dot-com era. That it's fundamental infrastructure that will support trillion-dollar businesses for decades.

Maybe they're right. Maybe AI really is revolutionary and transforms every aspect of computing. In that case, 2025-2026 will look back as the beginning of a multi-decade run of elevated memory demand.

Or maybe AI hits diminishing returns. Maybe the cost of training massive models becomes prohibitive. Maybe smaller, more efficient models become better than giant models. Maybe one or two companies dominate AI infrastructure and reduce redundant spending. Any of these scenarios would deflate demand and trigger the next cycle.

If demand moderates, memory manufacturers will find themselves with excess capacity. Prices will plummet. They'll return to the situation Samsung faced in 2023. Massive fixed costs, not enough demand to cover them, inventory piling up, and profit margins compressing.

This is why memory CEO guidance always includes language about "expected demand" and "continued growth expectations." They're not certain. They're betting. The bet is currently paying off phenomenally, but bets can go wrong.

For consumers, this paradoxically means you might want to wait. If the AI boom moderates, you could buy RAM in 2027 at 2021 prices. But if the boom continues, you'll be paying 2025 prices or higher.

There's no safe choice. You either pay inflated prices now or gamble that prices will come down later. Most analysts are betting the safe play is paying now, given the multi-year timeline for prices to normalize.

Micron's Exit From Consumer Markets: A Sign of the Times

Micron's decision to exit consumer RAM and storage markets is genuinely significant. This isn't a temporary pullback. This is a permanent strategic decision to abandon an entire customer segment.

Micron's reasoning is straightforward: consumer products have low margins, consumer customers are price-sensitive, and the company can make much more money serving data centers and enterprise customers. Why compete in a market where customers wait for sales when you can serve customers who'll pay whatever price you ask?

This also means PC builders have one fewer option. The "big three" memory manufacturers were once Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. Now Micron is effectively out of the consumer business, leaving just Samsung and SK Hynix competing for consumer retail sales.

Less competition means less pressure to lower prices. It also means less total production capacity allocated to consumer RAM. Micron's exit is reducing supply without reducing demand, which is a straightforward recipe for higher prices.

Other manufacturers are likely watching Micron's move carefully. If the strategy works for Micron—if they make higher profits per unit even while selling fewer units—others might follow. You could see a scenario where consumer RAM becomes almost an afterthought product that manufacturers tolerate but don't actively promote.

This is also somewhat self-reinforcing. As consumer products become less important to manufacturers, they invest less in consumer product development, factories get older and less efficient, and quality might decline. This makes consumer products even less attractive, pushing more allocation toward enterprise and HBM.

Global Economics: How Memory Shapes PC Costs Worldwide

Memory isn't just a component. It's a fundamental constraint on entire product categories. When memory prices spike, it cascades through the entire PC industry.

OEMs are hesitant to build PCs when memory costs are uncertain. Should they build a

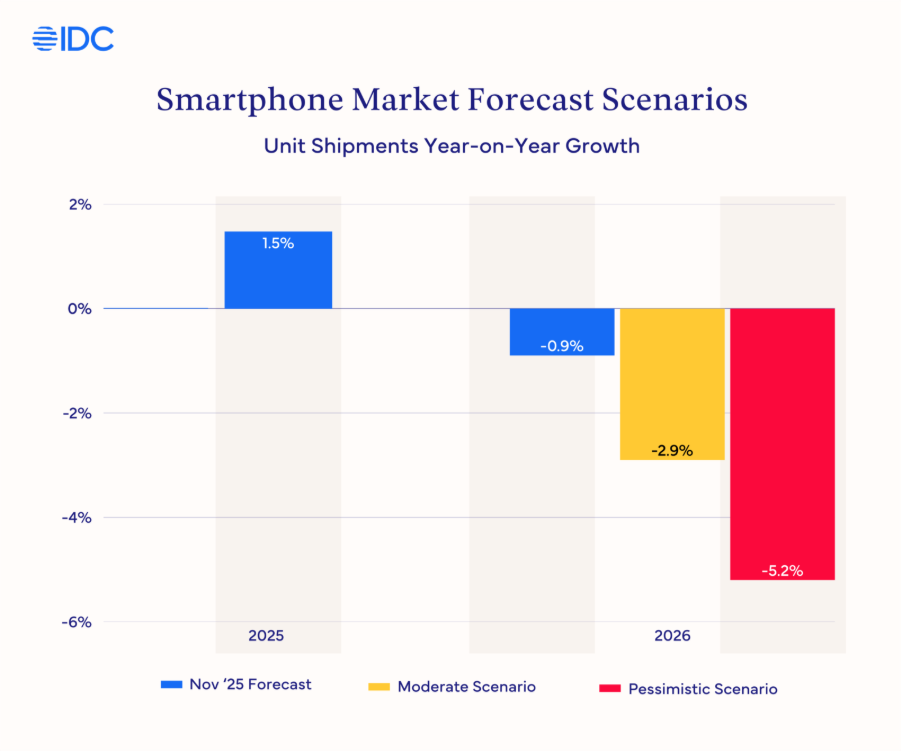

Smartphone manufacturers face the same problem. A flagship phone might use $30-50 of memory. If memory costs spike 30 percent, that's a meaningful hit to device margins. Some manufacturers absorb the cost, which reduces profit. Others pass it to consumers, which reduces demand. Either way, the entire market feels the impact.

Graphics card manufacturers can't build cards if memory is too expensive. Game consoles can't launch if memory supply isn't secured. Every modern computing device is memory-constrained right now.

This has global implications. Companies in regions with less purchasing power get priced out of upgrades. A $340 RAM kit is incomprehensible for someone in India or Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Western consumers complain about prices being high but can still afford them. The gap between markets is widening.

Memory manufacturers are aware of this. They don't care. The profit per dollar of revenue is higher selling to customers in wealthy markets than selling volume to price-sensitive markets. So supply follows profit, not need.

Industry Responses: How Companies Are Adapting

Companies affected by high memory prices are adapting in creative ways. Some are actually interesting from a product perspective.

Some OEMs are investing in software optimization to reduce memory requirements. If your application can run on 16GB instead of 32GB, the memory supply crunch is less painful. This is good for consumers long-term because software efficiency compounds over time.

Others are designing around the shortage by using faster, smaller memory pools (like more aggressive caching or using storage as extended memory). This is slower than using more RAM, but it works when memory is scarce.

Some manufacturers are negotiating long-term contracts with memory suppliers, locking in prices even if market prices spike higher. This provides certainty but might lock them into unfavorable pricing if the market crashes.

A few companies are exploring alternative memory technologies like persistent memory or storage-class memory that might have different cost structures. But these aren't mature enough to replace traditional DRAM yet.

The most aggressive response is from AI companies themselves. Some are investing in their own memory fab partnerships or backing memory startups. If commercial memory manufacturers can't deliver, they'll try to secure supply through partnerships.

But none of these responses solve the fundamental problem: there's more demand for memory than manufacturing capacity can support. Until new fabs come online or demand moderates, prices will stay elevated.

The Timeline: When Does This End?

Based on current forecasts, here's the realistic timeline:

2026: Expect continued high prices, possibly increasing further. Demand for AI infrastructure is expected to continue strong. New fab capacity coming online is minimal.

2027: This is the inflection point year. New fab capacity might be coming online in late 2027 or early 2028. Prices might start stabilizing if AI infrastructure buildout moderates slightly.

2028-2029: If multiple new fabs come online and AI infrastructure buildout peaks, prices could start declining. But "declining" might still mean prices stay 20-30 percent above 2021 levels.

2030+: The market likely rebalances. Either AI demand continues and supports higher memory prices permanently, or it moderates and prices crash back toward historical levels.

This is a multi-year phenomenon, not a temporary shortage. If you need a PC upgrade, you're essentially choosing between paying today's inflated prices or waiting 2-3 years for prices to normalize.

The smart play for consumers is probably upgrading now if you actually need the capacity, because waiting for prices to drop is a multi-year gamble. The smart play for memory manufacturers is maximizing profits while they can, knowing this period won't last forever.

Future Demand: Is This Permanent or Temporary?

Here's the billion-dollar question: will memory demand stay elevated forever, or will this boom eventually normalize?

The bull case is that AI infrastructure is genuinely transformative and will support higher memory demand indefinitely. Every company will need AI capabilities. Every service will be AI-powered. The infrastructure needs to support all of that. Memory will be a permanent resource constraint and will command premium prices.

The bear case is that AI will face efficiency improvements, smaller models will become better, and redundant infrastructure buildout will eventually stop. Once the major tech companies have built their primary infrastructure, capital spending will moderate. Memory demand will normalize. Prices will crash.

Both arguments have merit. The reality is probably somewhere in between: memory demand will stay elevated relative to pre-2025 levels, but prices will come down from current peaks once new fab capacity comes online.

What's certain is that this is the most significant supply-demand imbalance in the memory market since the cryptocurrency mining boom of 2017-2018. And unlike cryptocurrency, AI infrastructure has actual business use cases and enormous capital backing. The boom is more likely to persist for years rather than months.

For memory manufacturers, that's fantastic. For everyone else, it's a frustrating but real constraint on how fast you can upgrade your systems.

FAQ

Why are RAM prices so high right now?

RAM prices are elevated because AI infrastructure companies (like OpenAI, Google, Meta) are purchasing massive quantities for data centers, and memory manufacturers are shifting production capacity toward high-margin HBM chips for AI GPUs instead of consumer DRAM. This creates a supply shortage for consumer products while manufacturers achieve record profit margins.

Will RAM prices come down soon?

No, not in the near term. Industry analysts predict prices will remain elevated or continue increasing through 2026. Prices likely won't normalize until 2028-2029 when new manufacturing capacity comes online, and even then, prices might stay 20-30 percent higher than pre-2025 levels due to sustained AI infrastructure demand.

How much memory do AI data centers actually need?

AI infrastructure is consuming enormous amounts of memory. Estimates suggest OpenAI's "Stargate" data center project alone could consume up to 40 percent of global DRAM production. When you consider all the AI infrastructure being built by Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, and others, the total demand becomes larger than the entire consumer PC market combined.

Why is HBM production competing with consumer DRAM?

HBM (high-bandwidth memory) uses approximately three times as much silicon wafer space as equivalent amounts of standard DDR5 DRAM. When manufacturers shift production capacity to HBM, they're not just reducing DRAM output proportionally—they're disproportionately reducing consumer DRAM availability because the wafer space can no longer be used for other products.

Why did Micron exit the consumer RAM market?

Micron determined that consumer DRAM products have low profit margins compared to enterprise and AI memory products. By exiting retail consumer products and focusing entirely on high-margin data center and HBM sales, Micron can make higher total profits while selling fewer units. This also represents one fewer competitor in the consumer market, which reduces downward pressure on prices.

What happens to RAM prices if the AI bubble bursts?

If AI infrastructure investment moderates significantly or demand drops, memory manufacturers would find themselves with excess production capacity. This would likely trigger a price crash similar to what Samsung experienced in 2023, potentially pushing prices far below current levels. However, this scenario is not the consensus forecast—most analysts expect AI infrastructure demand to sustain elevated memory consumption for years.

Are memory manufacturers deliberately restricting consumer supply?

Not deliberately restricting—they're simply prioritizing higher-margin products. When a manufacturer can sell to OpenAI at premium prices with guaranteed contracts or to consumers at lower margins with uncertain demand, the choice is economically obvious. The result looks like artificial scarcity from a consumer perspective, but it's actually just profit maximization.

When will new memory manufacturing capacity come online?

New semiconductor fabs take 3-5 years to build from planning to production. Fabs starting construction now would likely come online around 2028-2029. This timeline explains why prices are expected to remain elevated through 2027—there's no capacity coming online in the next 18 months to alleviate shortages.

Should I buy RAM now or wait for prices to drop?

If you need upgraded memory capacity and the delay costs you productivity, buying now makes sense despite high prices. If you can wait 2-3 years, you could potentially save money. However, the prevailing analyst consensus is that prices will remain elevated for multiple years, so the "discount" you might get by waiting is uncertain and might not materialize.

How do memory prices affect PC and laptop prices?

When memory costs spike, OEMs face margin pressure. They either absorb the cost (reducing their profit), pass it to consumers (reducing demand), or delay production (creating supply gaps). For consumers, expect PC prices to rise if memory costs remain elevated, with budget systems affected more severely than premium systems because base memory costs represent a larger percentage of total price.

Key Takeaways

- Memory manufacturers are achieving record profits of $13.8B+ quarterly due to elevated RAM prices driven by AI infrastructure demand

- HBM production for AI GPUs requires 3x the wafer space of standard DDR5, creating disproportionate reductions in consumer DRAM availability

- OpenAI's Stargate project alone could consume 40% of global DRAM production, forcing consumers to compete with infinite-budget tech giants

- Prices are expected to remain elevated or increase through 2026, with normalization not expected until 2028-2029 when new fabs come online

- Micron's exit from consumer markets reduces competition and further constrains supply available to retail customers

Related Articles

- Nvidia's Upfront Payment Policy for H200 Chips in China [2025]

- Intel Core Ultra Series 3: The 18A Process Game Changer [2025]

- Intel Core Ultra Series 3: The Panther Lake Comeback Explained [2026]

- Nvidia's Vera Rubin Chips Enter Full Production [2025]

- PC Prices Set to Soar in 2026: RAM Shortage & AI Demand Explained [2025]

- SPHBM4 HBM Memory: How Serialized Substrates Are Reshaping AI Accelerator Economics [2025]

![Why RAM Prices Are Skyrocketing: AI Demand Reshapes Memory Markets [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-ram-prices-are-skyrocketing-ai-demand-reshapes-memory-ma/image-1-1767906522355.jpg)