Introduction: When the Internet Comes Back, But Half of It Disappears

Imagine waking up one morning and your internet is gone. Completely. Then a few days later, it comes back—but only partially. You can access email, browse websites, read news. But WhatsApp? Blocked. Facebook? Inaccessible. TikTok? Don't even try. That's what happened in Uganda in January 2025.

This isn't a technical glitch. This is deliberate government censorship, and it's revealing something uncomfortable about how the internet actually works in parts of the world. While Uganda initially shut down the entire internet to restrict communications during political turmoil, authorities later opted for a more surgical approach: keeping general internet access while strangling social media and messaging platforms.

The result has been dramatic. VPN usage in Uganda hit an all-time high as millions of citizens scrambled for ways to access the blocked services. WhatsApp, Facebook, and other messaging apps—which have become essential infrastructure for business, family communication, and civic participation—simply vanished from the network.

What makes this situation particularly significant is how it exposes the mechanics of digital authoritarianism in real time. This isn't about keeping citizens offline. It's about controlling which parts of the internet they can access. It's about silencing communication channels while maintaining plausible deniability about blanket censorship.

This article walks you through what happened in Uganda, how selective internet blocking works, why it matters globally, and what it means for digital freedom worldwide. We'll examine the technical methods governments use to block specific services, the geopolitical implications, and what citizens and organizations can do when their connectivity becomes a political tool.

TL; DR

- The Blockade: Uganda restored general internet access but kept social media and messaging apps blocked, including WhatsApp, Facebook, TikTok, and Telegram

- The Response: VPN usage in Uganda surged to record levels as citizens sought workarounds to access blocked services

- The Method: Governments use Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) and DNS blocking to surgically block specific platforms while leaving general internet functional

- The Pattern: This selective blocking approach is becoming the new standard for digital authoritarianism, replacing blunt full-internet shutdowns

- The Impact: Millions lose access to essential communication tools while authorities claim to support "free internet"

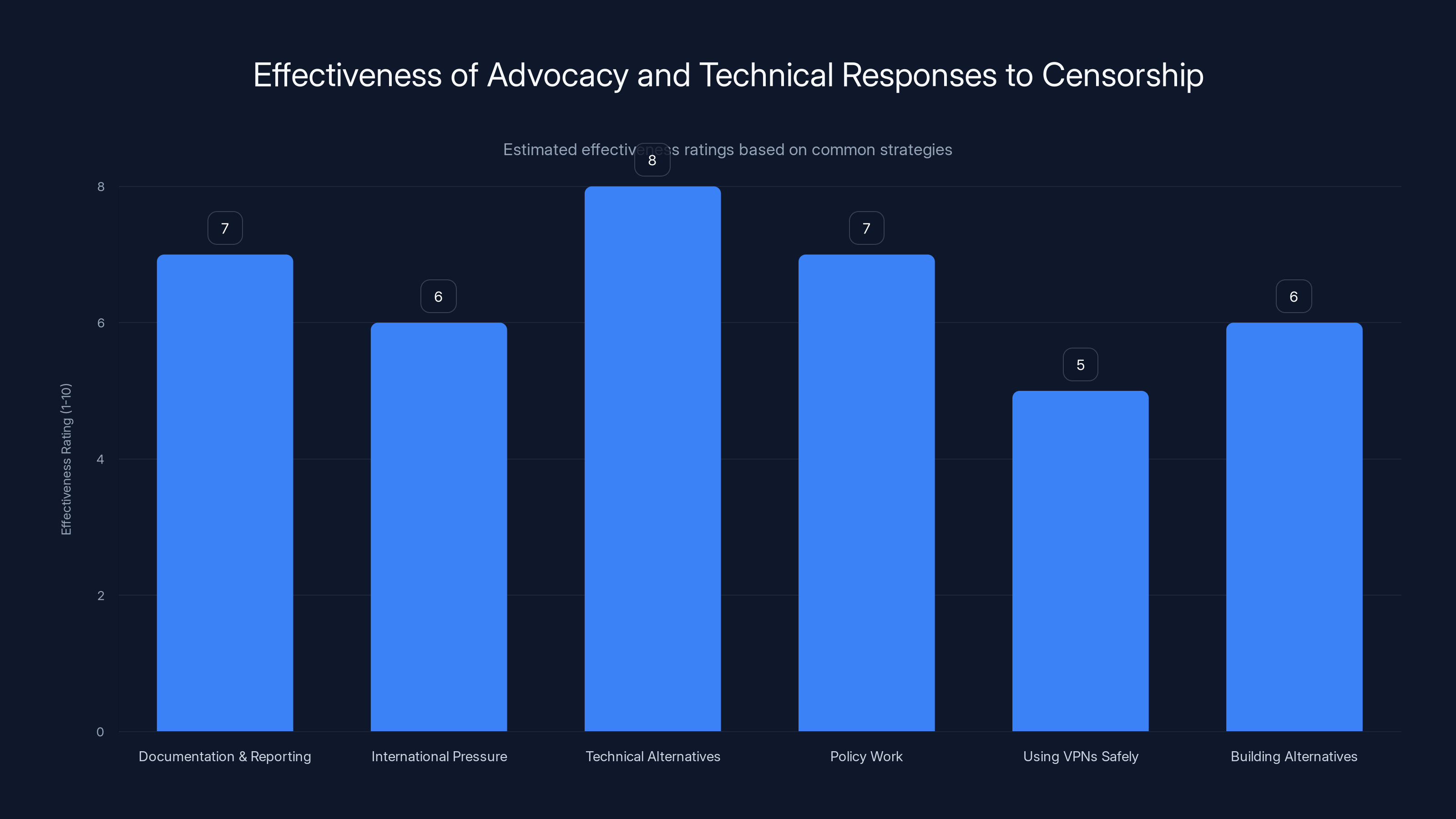

Technical alternatives and documentation/reporting are estimated to be the most effective strategies for combating censorship, with ratings of 8 and 7 respectively. Estimated data.

What Actually Happened in Uganda: The Timeline of Digital Disruption

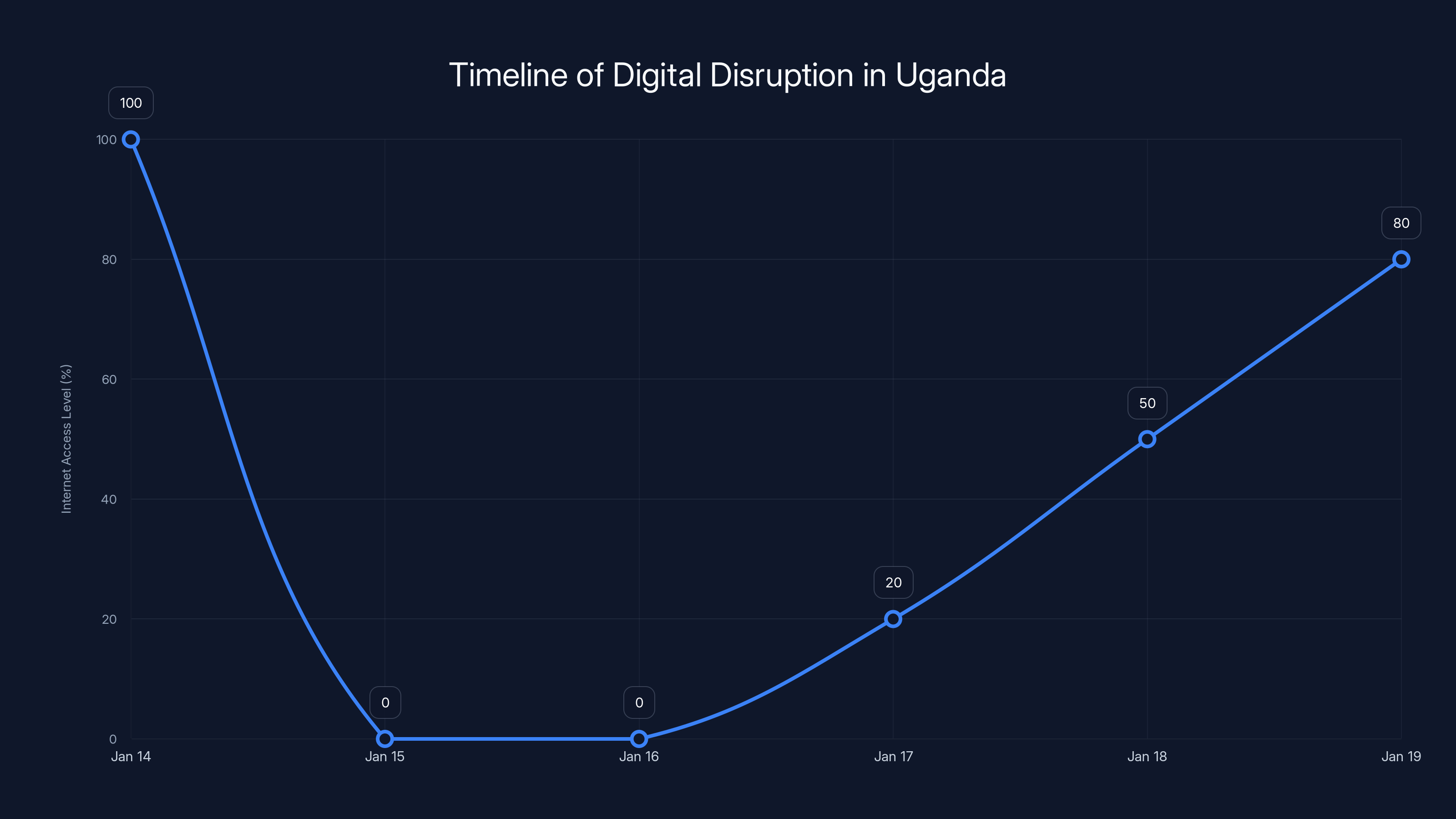

To understand the Uganda situation, you need to know what triggered it. Uganda held presidential elections on January 14, 2025, and tensions ran high. Government authorities grew concerned about how social media could be used to organize opposition movements or spread what they considered misinformation.

The response was swift and brutal. Internet providers received orders to shut down connectivity entirely. For several days, Ugandans couldn't access anything online. No emails, no browsing, no streaming, no social media. Nothing. The kill switch was activated.

But a full-internet shutdown creates real economic damage and international attention. Businesses can't operate. Banks can't process transactions. Tourism dries up. After the initial shutdown proved its intended effect (limiting political organization), authorities shifted tactics.

They restored general internet access. This was technically smart. It allowed the government to argue that the internet was working again, that they were restoring connectivity, that normalcy was returning. But they didn't restore all connectivity. Specific services remained inaccessible.

The blocked list included the heavy hitters: WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Telegram. These are the platforms where people organize, share information, and communicate without government surveillance. By keeping them blocked while restoring everything else, Uganda's authorities achieved several goals simultaneously: reduced opposition organizing capacity, maintained plausible deniability about censorship, and avoided the full economic pain of a complete internet blackout.

It's a template. And it's being copied.

Understanding Deep Packet Inspection: How Governments Block Specific Services

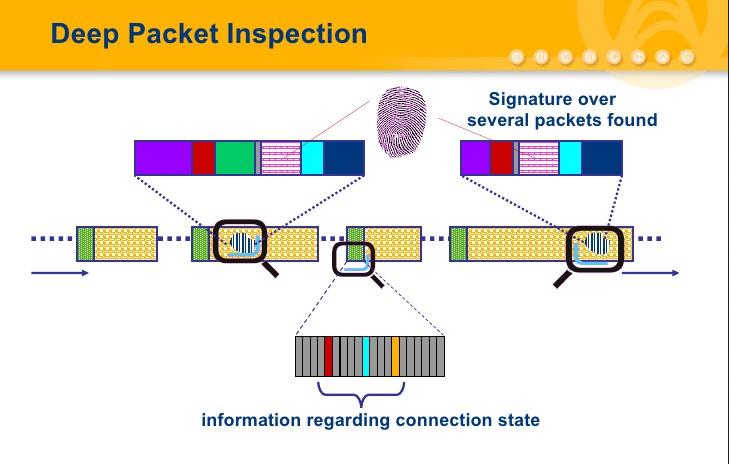

You might wonder how a government blocks just WhatsApp while leaving the rest of the internet running. The technical answer involves something called Deep Packet Inspection, or DPI. This is where things get technical but important to understand.

Every time data travels across the internet, it's broken into small units called packets. Each packet contains data plus metadata about where it's coming from, where it's going, and what kind of data it is. Traditional firewalls look at this metadata. DPI goes deeper.

Deep Packet Inspection examines the actual content of the packets, not just the metadata. It's like a border agent who doesn't just check your passport but opens your luggage and examines every item. DPI technology can identify what service you're using based on the patterns in the data being transmitted, even if the traffic is encrypted.

Here's how it works in practice: WhatsApp traffic has specific characteristics. The way data is structured, the timing of packets, the size and frequency of communications—these create a fingerprint. Even encrypted traffic has a fingerprint. A DPI system learns to recognize this fingerprint and can block traffic matching that pattern.

So when you try to use WhatsApp in Uganda right now, your device sends packets that the DPI system recognizes as WhatsApp traffic. Those packets get dropped. You see the spinning loading icon that never resolves. The connection times out.

But an email traveling to Gmail? Different fingerprint. Different patterns. Different timing. The DPI system lets it through.

This is why VPN usage in Uganda surged immediately after selective blocking began. A VPN encrypts and reroutes all your traffic through an external server. From the government's perspective, instead of seeing WhatsApp traffic coming from your device, they see encrypted traffic going to a VPN server in another country. They can't tell what you're actually accessing. The fingerprint is gone.

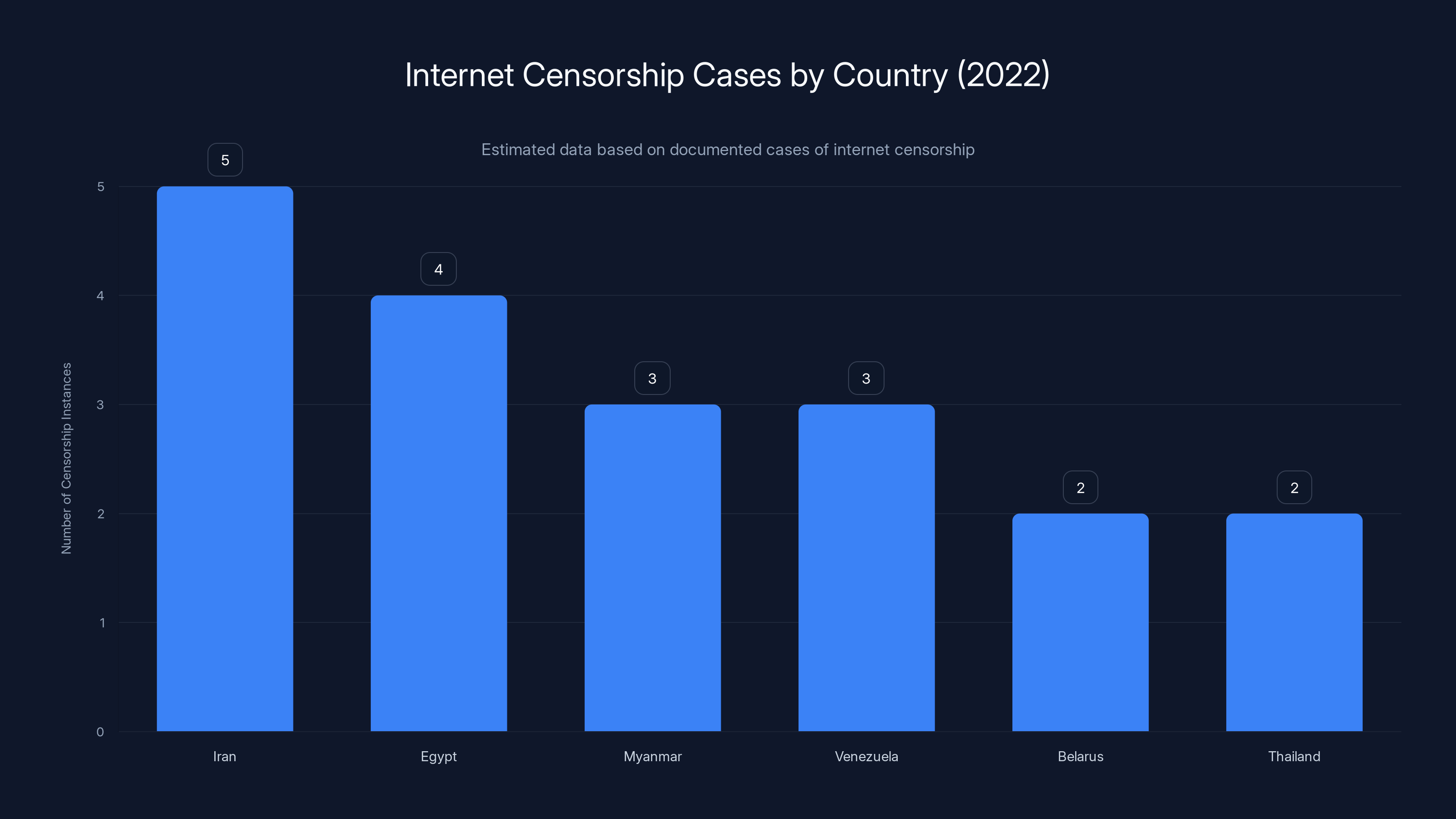

Estimated data shows that Iran had the highest number of censorship instances in 2022, followed by Egypt and Myanmar. This reflects a global trend of increasing selective internet blocking.

DNS Blocking: The Other Method Governments Use

DPI isn't the only tool in a government's censorship toolkit. DNS blocking is actually simpler and cheaper to implement, though it's also easier to bypass.

The Domain Name System (DNS) is essentially the internet's phonebook. When you type "facebook.com" into your browser, your computer asks a DNS server, "What's the IP address for facebook.com?" The DNS server responds with something like "31.13.64.9", and your browser connects to that address.

DNS blocking intercepts these requests. When you try to look up facebook.com, the DNS server either doesn't respond or responds with a fake IP address that points nowhere. Your browser can't find Facebook because it can't find the IP address.

But here's the thing about DNS blocking: it's trivial to bypass. You can use a different DNS server. Google DNS, Cloudflare DNS, or countless others can resolve facebook.com just fine. That's why DNS blocking is usually paired with DPI-based blocking. DPI catches people using alternative DNS servers and blocks their traffic anyway.

In Uganda's case, authorities likely deployed both. DNS blocking for casual users who might not know about workarounds, and DPI blocking for more technical users who try to get around DNS blocking.

Why Social Media Gets Blocked But Email Doesn't: The Political Calculus

There's a logic to which services get blocked and which don't. It's not random. It's about controlling information flow while maintaining enough functionality to avoid economic collapse.

WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Telegram share something critical: they're platforms where people can communicate and organize without direct government visibility. A WhatsApp group chat about organizing a protest? The government can't read it. A Facebook post criticizing the election? Visible to thousands. TikTok videos documenting police activity? Spreading instantly.

Email, by contrast, feels safer to authorities because it's less real-time and less social. A protest organized via email is less likely to spread as quickly as one organized on WhatsApp or Facebook. Email also feels more "business-like" and "legitimate," making it harder politically to block without drawing criticism about harming commerce.

Messaging and social media are the nervous system of modern organizing. They're how information propagates. They're how people coordinate. They're how movements gain momentum. That's exactly why authoritarian governments target them specifically.

Websites? Those can stay on but can be monitored. Search engines like Google stay functional. Email persists. Banks work. The economy hums along. But the pathways that enable rapid, coordinated collective action get severed.

It's sophisticated. It's not crude. It's the opposite of a sledgehammer—it's a scalpel.

VPN Usage Hits All-Time High: The Real Story Behind the Surge

Within hours of the social media blockade taking effect, VPN providers in Uganda reported unprecedented demand. People were desperate to access their messaging apps, their social accounts, their digital lives.

But what does "all-time high" actually mean in this context? VPN companies track how many users are connecting from specific countries. When Ugandans suddenly couldn't access WhatsApp through normal means, they turned to VPNs. Some downloaded them for the first time. Others who already used VPNs switched to more robust ones that could handle sustained government blocking.

The surge tells us something important: regular people, not just tech-savvy activists, are willing to use circumvention tools when access to essential services is restricted. This wasn't a niche activity. This was millions of ordinary people taking action because the services they rely on were taken away.

But here's where it gets complicated. VPN usage is visible. When millions of people suddenly start routing traffic through external servers, governments can see the traffic spike. They can identify which providers people are using. And then they can take the next step: block the VPNs themselves.

Some VPN providers were indeed blocked in Uganda. The cat-and-mouse game escalated quickly. Users switched to smaller, lesser-known VPN services. Those got blocked too. Then people started using proxy services, tor networks, and other circumvention tools. Each layer of blocking creates demand for the next circumvention method.

What started as a social media blockade became a technological arms race between citizens seeking connectivity and authorities seeking control.

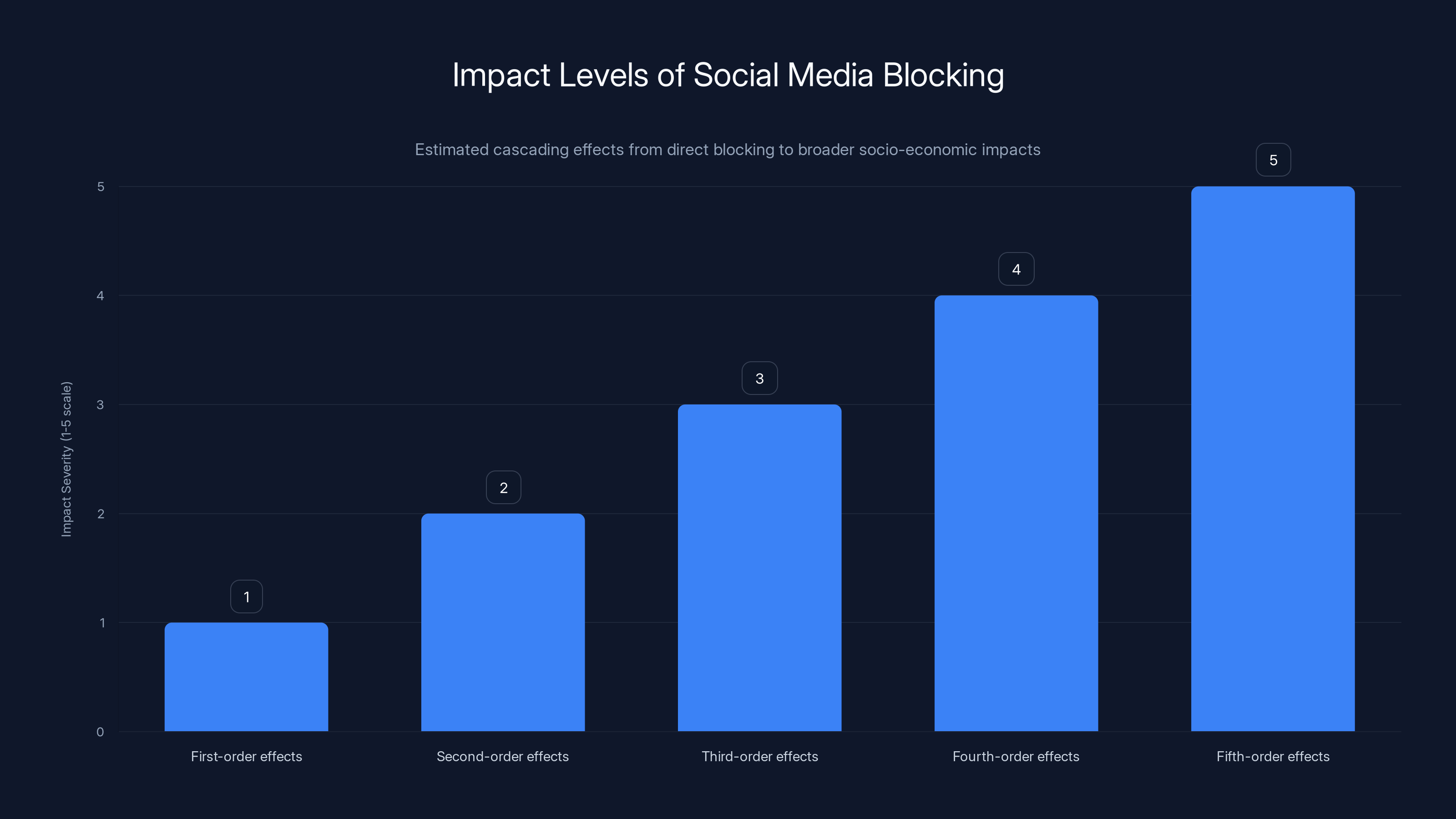

The severity of impacts increases with each order, starting from direct platform inaccessibility to broader socio-economic and political instability. Estimated data based on typical cascading effects.

The Economics of Internet Censorship: Who Really Pays the Price

When you block WhatsApp, you're not just limiting conversation. You're disrupting business.

Consider an SME (small or medium enterprise) in Uganda that uses WhatsApp Business to manage customer communications, orders, and payments. When WhatsApp gets blocked, that business essentially goes offline for customer interactions. Entrepreneurs lose sales. Customers can't place orders. Service providers can't respond to inquiries.

Uganda's economy is heavily dependent on informal commerce and services. Small businesses, traders, and freelancers rely on WhatsApp and other messaging apps as their primary communication infrastructure. There's no official ordering system, no centralized platform. It's person-to-person, WhatsApp-to-WhatsApp business.

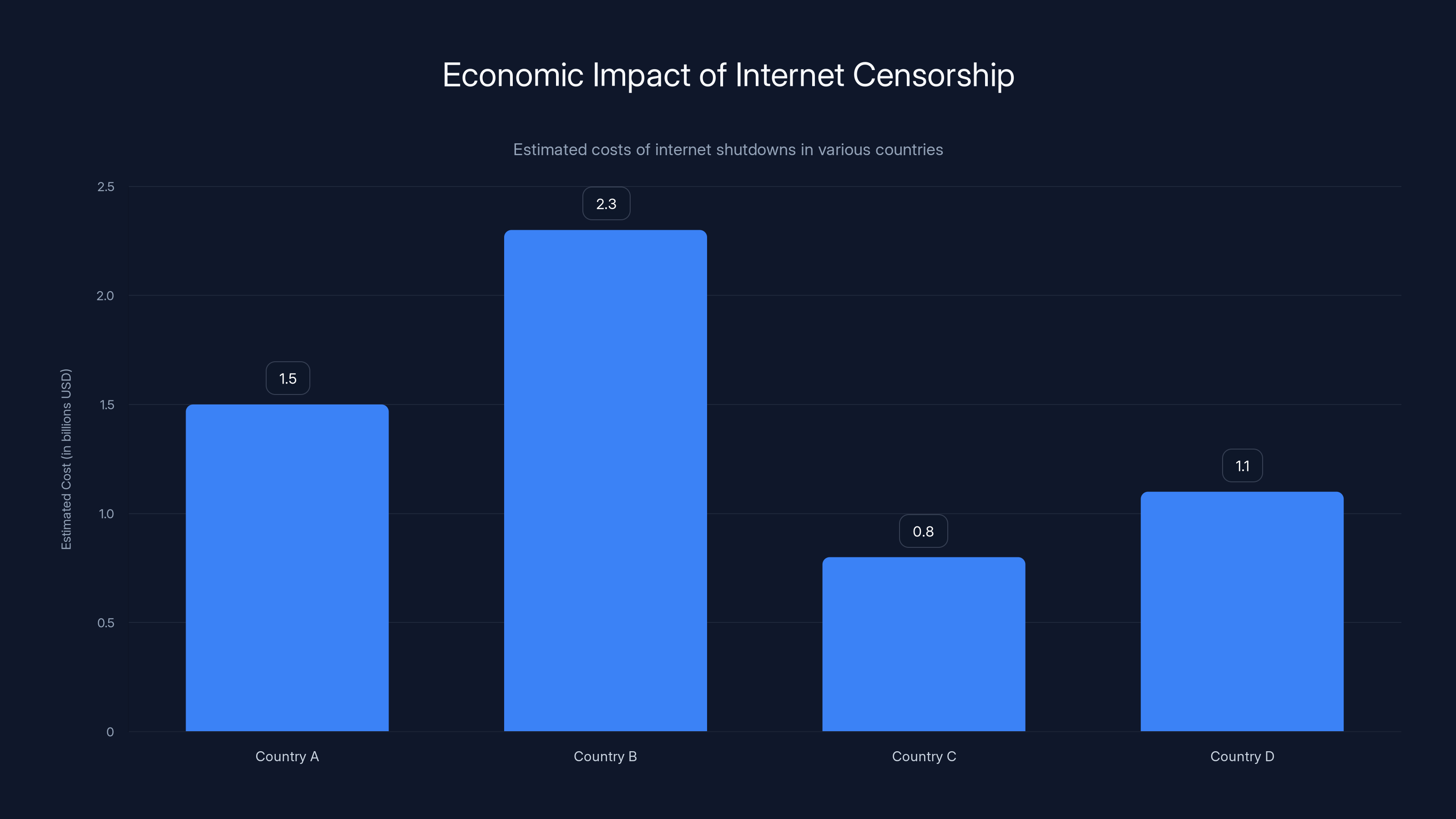

The International Monetary Fund and World Bank have documented the economic cost of internet shutdowns. We're talking billions of dollars in lost economic output. Uganda's telecommunications sector, which contributes meaningfully to national GDP, suffers. International investment becomes riskier when internet reliability is uncertain. Tourism falters when visitors can't reliably access mapping, translation, and communication services.

Odd paradox: governments that shut down the internet in the name of national security often end up harming their own economies more than any opposition movement could.

But there's a deliberate calculation here. A government willing to damage its own economy slightly is willing to accept that damage if it preserves political control. The math is different when you view a shutdown not as an economic policy but as a security measure. To authorities, the cost is acceptable.

For ordinary citizens and businesses? The cost is everything.

Comparing Uganda to Other Censorship Cases: A Global Pattern Emerges

Uganda isn't unique. This pattern of selective blocking is becoming disturbingly common.

In 2022, Iran blocked Instagram and WhatsApp during anti-government protests. The strategy was identical: keep general internet access but sever the communication channels where protesters organize. Egypt has done this repeatedly, most notably during the 2011 uprising and subsequent crackdowns. Myanmar blocked Facebook for extended periods. Venezuela, Belarus, Thailand, and dozens of other countries have deployed similar tactics.

What's changed recently is the sophistication and speed of implementation. Governments used to shut down the entire internet because it was the blunt tool they had. Now, with more advanced DPI technology and better training, they can execute precision blocking within hours or minutes.

The concerning trend is convergence. Governments are learning from each other. When selective blocking works in one country, it spreads to others. Technical advisors from authoritarian governments share best practices. Companies that develop DPI and blocking technology advertise their services globally. It's a marketplace for digital control.

Some of these technologies come from Western companies. Reuters has documented how Western firms sell surveillance and censorship technology to authoritarian regimes. There's an uncomfortable layer of complicity here—democracies creating tools that dictatorships use to suppress their own people.

The Human Cost: What "Social Media Blocked" Actually Means

When we talk about social media being blocked, we're using language that feels abstract. Let's get concrete about what that means for real people.

A teenager in Kampala can't video call their family member in the diaspora through WhatsApp. They can use other services, sure, but they had family members on WhatsApp. They have to find them on other platforms, if they're there. They might not be.

A woman running a catering business from her home can't take orders through her WhatsApp Business account where her customers contact her. She might not know how many orders she missed. She might lose customers to competitors who found workarounds first.

A journalist trying to receive tips and leads from sources can't use the encrypted messaging apps that provide the security and anonymity those sources need. They're suddenly much more visible, much more vulnerable to pressure.

Activists trying to coordinate any kind of response to government overreach lose their primary tool for rapid communication. The asymmetry is massive—the government maintains its communication infrastructure while citizens lose theirs.

Parents can't use WhatsApp to check in with their kids. Healthcare workers can't use messaging apps to consult with colleagues. Small loan networks that operate through group chats lose their primary infrastructure.

When you strip away the technical discussion and the political analysis, what remains is disruption to millions of people's daily lives. Not disruption like "the wifi is slow." Disruption like "I can't contact the people I depend on."

This is the human reality of what sounds like a technical policy.

Estimated data shows that internet shutdowns can cost economies billions, affecting commerce and productivity. (Estimated data)

How to Detect if You're Being Blocked: Technical Signs and Signals

If you're experiencing internet censorship, how do you know what's actually happening? Are you being blocked? Is it a technical glitch? Is your ISP having problems?

There are technical ways to diagnose blocking. When you try to access a blocked service, look for specific patterns:

DNS Blocking: You try to visit facebook.com, but your browser returns an error like "Can't find server" or "No such site." But when you try to ping the Facebook IP address directly, the connection works. This indicates DNS blocking specifically—the domain lookup is being intercepted, but direct IP connections work.

DPI Blocking: You try to use WhatsApp, but the app hangs indefinitely. Connections time out. No error message, just nothing. When you switch to a VPN, it works instantly. This indicates DPI-based blocking—the traffic is being identified and dropped at the network level.

Firewall Blocking: Certain websites load slowly or incompletely. Images load but text doesn't. It's inconsistent. This might indicate keyword-based filtering where connections are throttled based on content.

You can test these by trying different tools. Use a different DNS server. Try a VPN. Try accessing the service from a different network (mobile data instead of wifi, or vice versa). Each test narrows down what's actually being blocked.

Organizations like the Global Network Initiative and Amnesty International have developed citizen-friendly testing tools that can document what's being blocked and how, creating evidence for advocacy and legal challenges.

The Role of Internet Service Providers: Who Actually Does the Blocking

Governments don't block the internet directly. They order ISPs to do it.

ISPs are the companies that provide internet connectivity to homes, businesses, and mobile phones. In Uganda, the major ISPs include MTN Uganda, Airtel Uganda, and others. When the government orders blocking, the ISP has to implement it.

This puts ISPs in an ethically uncomfortable position. They're regulated by government. They need government approval to operate. Refusing a government directive means losing their license, facing fines, potentially facing criminal charges. For most ISPs in authoritarian countries, compliance is not optional.

ISPs implement blocking through their network infrastructure. They deploy the DPI technology in their network, they implement DNS filtering at their DNS servers, they configure routers and gateways to drop traffic matching blocked patterns. It's done at the network level, before the traffic even reaches you.

Some ISPs are more resistant than others. Some push back, document the pressure they're under, work with international organizations to publicize what's happening. But most comply quietly. Transparency about government censorship requests varies dramatically by country. Some countries have laws requiring ISPs to publish transparency reports about blocking requests. Others don't.

The result is a system where the government maintains plausible deniability ("We're not blocking, the ISPs are just having technical issues") while the ISPs do the actual work and carry the liability.

VPN Services and Circumvention Tools: Do They Actually Work

When social media gets blocked, the obvious response for tech-savvy users is to use a VPN. But do they actually work? And are they reliable?

The answer is: sometimes, but it's getting harder.

A VPN works by routing all your traffic through an external server in another country. Your ISP can't see what you're accessing—it only sees encrypted traffic going to the VPN server. The VPN server receives the encrypted data, decrypts it, makes the actual request (like accessing WhatsApp), and sends the response back to you encrypted.

This defeats DPI-based blocking in most cases because the ISP can't inspect the contents to identify WhatsApp traffic. But some governments have implemented VPN blocking. They identify known VPN providers and block traffic to their servers.

When major VPN providers get blocked, users switch to smaller, less-known providers. Or they use proxy services. Or Tor (the anonymity network). Or peer-to-peer proxy networks where regular users run proxy software on their computers in uncensored countries.

It becomes an escalating arms race. Each tool the government blocks prompts adoption of the next tool.

But here's the limitation: not everyone can use these tools. They require technical knowledge to set up. They often cost money (good VPNs aren't free). They can be slow (encryption and re-routing adds latency). And they're not foolproof—determined government actors can eventually identify and block any circumvention method.

The real issue is that circumvention tools are available to activists and tech-savvy users, but they're not available to ordinary people. The business owner who just wants to check WhatsApp, the student who just wants to access social media, the parent who just wants to video call family—they're unlikely to successfully navigate circumvention tools.

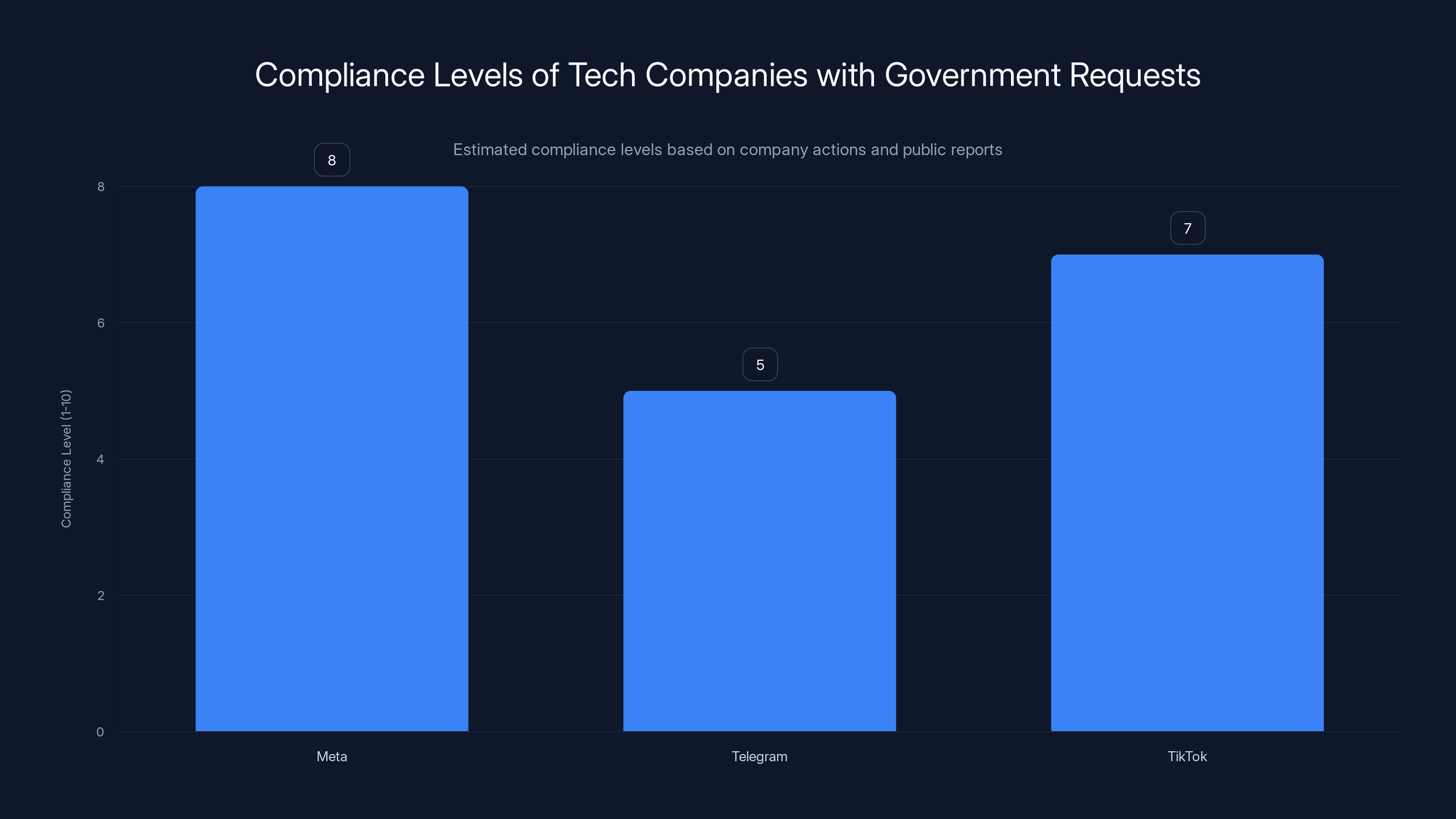

Estimated compliance levels show Meta as the most compliant with government requests, followed by TikTok and Telegram. Estimated data.

Government Justifications: What Authorities Claim They're Protecting Against

Governments don't frame blocking as censorship. They frame it as security, protection, and prevention of misinformation.

Uganda's government claims that blocking social media during elections prevents "election interference," "misinformation," and "incitement to violence." These aren't crazy concerns—election interference and incitement are real issues. The question is whether blocking social media for the general population is a proportionate response.

Other governments have used similar language. China claims its Great Firewall protects against "foreign propaganda." Iran says blocking protects against "color revolutions" and "regime change conspiracy." Thailand has blocked content it claims violates lèse-majesté laws (insulting the monarchy).

There's a grain of truth buried in each justification. Elections can be interfered with. Misinformation can spread. Incitement can happen on social media. But these real problems are being used to justify measures that suppress legitimate speech, block political organizing, and control information.

The pattern is: take a real problem, dramatically overstate how prevalent it is, use that exaggeration to justify extreme measures, and then quietly extend those measures beyond the original stated scope. What starts as a temporary election security measure becomes permanent infrastructure for controlling speech.

International organizations have documented this repeatedly. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch regularly publish reports documenting how governments abuse censorship powers for political purposes rather than actual security.

The Cascading Effects: Secondary Impacts Beyond Direct Blocking

When social media and messaging get blocked, the consequences extend far beyond people not being able to access their platforms.

First-order effect: People can't use the platforms they want to use.

Second-order effects: Digital payment systems that rely on messaging apps break. Remittances from family abroad can't be arranged through WhatsApp. Medical consultations conducted via video calls become impossible. Small businesses that use Facebook and Instagram as their entire online presence disappear from the internet.

Third-order effects: Startups and digital businesses relocate to countries with reliable internet. Investment in the tech sector decreases—why build a digital business in a country where the internet can be shut down? International companies become hesitant to establish operations there. The broader economy weakens.

Fourth-order effects: Young, educated, tech-savvy people—exactly the people who could drive economic growth and innovation—start looking for opportunities elsewhere. Brain drain accelerates. The country's future competitiveness diminishes.

Fifth-order effects: When citizens see their government blocking the internet, trust in institutions decreases. The government's already limited legitimacy takes another hit. Political stability becomes shakier. Foreign investors see a risky environment and pull back.

It's a downward spiral that starts with a single policy decision but cascades through the entire social and economic system.

What Citizens Can Do: Practical Advocacy and Technical Responses

If you're in a country experiencing censorship (or want to support people in those countries), what actually works?

Documentation and Reporting: Organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Amnesty International, and local NGOs collect evidence of censorship. Reporting what you experience—screenshots of errors, timestamps of when services became inaccessible, which specific services are blocked—creates a documented record. This record is used for advocacy, legal challenges, and international pressure.

International Pressure: Government censorship is more likely to continue if it's not publicized. International media attention, statements from other governments, and pressure from international organizations can create diplomatic consequences. Not always effective, but better than silence.

Technical Alternatives: Supporting and promoting services with better resilience to censorship helps. Decentralized social networks that don't rely on central servers are harder to block. Encrypted messaging services designed specifically for censorship resistance (like Signal and Briar) provide alternatives to mainstream platforms.

Policy Work: Supporting digital rights organizations that work on policy change is one lever. These organizations advocate for laws protecting digital freedom, challenging censorship in courts, and building political momentum for change.

Using VPNs Safely: If you do use VPNs to circumvent censorship, do it carefully. Use reputable providers with strong privacy policies and no-logging commitments. Be aware of the risks—governments have prosecuted people for using VPNs. In some countries, merely using a VPN without explicit permission is illegal.

Building Alternatives: Some communities are building mesh networks and alternative internet infrastructure that doesn't rely on centralized ISPs. These are more resilient to government censorship (though they have their own challenges).

The chart illustrates the estimated changes in internet access in Uganda during the 2025 elections, highlighting a complete shutdown followed by partial restoration with selective service blocks. Estimated data.

The Bigger Picture: Global Trends in Digital Control

Uganda's experience isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a larger global trend.

According to the Freedom House Freedom on the Net reports, internet freedom has been declining globally for the past decade. More countries are implementing censorship. More governments are building surveillance infrastructure. More tech companies are complying with censorship requests.

What's particularly concerning is the acceleration. Five years ago, blocking specific applications through DPI was unusual and technically challenging. Now it's routine. The technology is commodified. Training is available. The political will to implement it is widespread.

We're entering a phase where the internet—which was supposed to democratize information and empower people—is becoming a tool for centralized control in many parts of the world. Some countries maintain relatively open internet. Others are moving toward what researchers call "splinternet"—fragmented national internet systems that different countries control independently.

China's Great Firewall was once seen as an extreme anomaly. Now dozens of countries are building similar systems, albeit less comprehensive. The anomaly is becoming the norm.

The implications are profound. If large portions of the world's population lose access to global internet infrastructure and instead use fragmented national versions, the internet we thought we had—global, interconnected, borderless—ceases to exist.

The Technology Companies' Role: Complicated Complicity

Where do companies like Meta (Facebook/Instagram/WhatsApp), Telegram, and TikTok fit into this?

They're in an impossible position. They want to operate globally. That requires complying with local regulations. But in authoritarian countries, those regulations increasingly include censorship demands.

Meta complies with government removal requests, which is how governments can force removal of specific content. But when a government demands blocking of the entire service, Meta can't really comply—they don't control ISPs. What they can do is cooperate with governments by monitoring activity, providing data on users, and sometimes providing local versions that include censorship.

TikTok has been more complicated, with various governments trying to force bans or restrictions ostensibly for security reasons (though often more for political control reasons).

The fundamental issue is that these companies have become so critical to communication and information that governments consider them essential infrastructure, subject to government control. The companies object, but their objections carry limited weight against governments that can ban them entirely.

Some tech advocates argue for decentralized alternatives where no single company controls the infrastructure. Others argue for stronger legal protections for digital freedom. The debate is ongoing, but the trend seems to be toward more government control, not less.

What Comes Next: Predictions for Digital Freedom in 2025 and Beyond

Based on current trajectories, what should we expect?

More selective blocking: The Uganda model will likely spread. Rather than crude full shutdowns, governments will get better at surgical blocking of specific platforms. This is becoming technically easier and politically more sustainable.

VPN blocking becomes standard: As more countries adopt selective blocking, they'll also adopt VPN blocking. We'll see an arms race in circumvention technology—VPN blocking drives adoption of more sophisticated tools, which drives government investment in more sophisticated blocking technology.

Splinternet acceleration: China's model of a segregated national internet will become more common. Rather than one global internet, we'll see regional internet systems controlled by governments, with restricted cross-border data flow.

Regulation as censorship: Governments will increasingly use regulations—rules about misinformation, election interference, extremism—as legal justification for censorship. The censorship will be framed as enforcement of law rather than political control.

Tech company fragmentation: As different countries impose different demands, tech companies may fragment into different services for different regions. A "WhatsApp" in one country might be fundamentally different from WhatsApp in another.

Increased activism: As censorship becomes more obvious and more pervasive, resistance will increase. We'll see more people learning about and using circumvention tools, more digital rights activism, more political pressure against governments that engage in censorship.

The optimistic scenario is that global pressure and economic incentives lead countries to back away from censorship. The pessimistic scenario is that governments win the arms race and successfully fragment and control the internet in their jurisdictions.

The most likely scenario? Both happen simultaneously in different places. Some countries move toward more freedom, others toward more control. The internet becomes increasingly geopolitically fragmented.

Why This Matters for Businesses and Individuals Globally

You might be reading this from a country with relatively open internet. Why should you care what's happening in Uganda?

Because patterns that emerge in one country often spread globally. Governments learn from each other. Technical capabilities that are deployed first in authoritarian countries eventually become available to democracies. What seems like an extreme measure in one country becomes a normal policy response in the next.

Also, because digital supply chains are global. If your company has customers, employees, or suppliers in countries with censorship, that affects your business. Payment processing becomes complicated. Communication becomes unreliable. Operations become riskier.

And because digital freedom is a prerequisite for economic development. Countries that censor heavily tend to have less innovation, less investment, less economic opportunity. If you care about global economic development, you should care about digital freedom.

Finally, because it affects the future of the internet itself. The architecture and governance decisions being made now—in Uganda and dozens of other countries—are shaping what the internet becomes for everyone.

FAQ

Why would a government block social media but not other internet services?

Governments block social media specifically because these platforms enable rapid communication, coordination, and information spread that governments can't monitor or control. Email, browsing, and commercial services feel less threatening to authorities because they're less conducive to rapid organization. The goal is to prevent political organizing and collective action while maintaining enough internet functionality to avoid economic collapse and international backlash.

Can VPNs really get you around internet censorship?

VPNs can defeat Deep Packet Inspection-based blocking by encrypting and rerouting your traffic through external servers, but they're not foolproof. Sophisticated governments can identify and block VPN traffic, and using VPNs may be illegal in some countries. VPNs work best for tech-savvy users but are challenging for non-technical populations, and good VPN services often cost money. For determined government actors, defeating VPNs is possible but requires advanced technical capabilities.

Is Uganda's approach unique, or is this happening elsewhere?

Uganda's selective social media blocking is becoming disturbingly common globally. Iran, Egypt, Myanmar, Venezuela, Belarus, and many other countries have used similar tactics, particularly during politically sensitive periods like elections or protests. What's changing is that the technology for selective blocking is becoming cheaper and more accessible, meaning this approach is spreading to more countries.

What's the economic impact of internet censorship?

The economic impact is substantial. The International Monetary Fund estimates that major internet shutdowns cost economies millions or billions of dollars through disrupted commerce, lost productivity, reduced foreign investment, and brain drain as educated workers leave countries with unreliable internet. For developing economies that rely heavily on digital commerce and services, censorship can be devastating.

Can international pressure actually stop governments from censoring?

International pressure has limited direct effectiveness, but it's not worthless. Media attention and diplomatic statements can raise political costs for governments engaged in censorship. International organizations documenting censorship create records useful for legal challenges. Countries worried about international reputation or trade consequences may moderate their censorship. However, governments willing to accept international criticism can usually persist in censorship if they believe it's politically necessary.

What technical methods do governments use to block specific services?

Governments primarily use two methods: DNS blocking, which intercepts domain name lookups so you can't find the service's server, and Deep Packet Inspection (DPI), which examines the contents of network traffic to identify specific applications and block them. DNS blocking is simpler but easier to bypass. DPI is more sophisticated and harder to circumvent but more expensive to implement and maintain. Most governments use both methods together.

Are decentralized social networks a real solution to censorship?

Decentralized networks where no single company controls the infrastructure are theoretically harder to censor because there's no central point of control. Services like Mastodon (decentralized Twitter alternative) and Matrix (decentralized messaging) exist, but they face adoption challenges because they lack the network effects of centralized platforms. Users are also less familiar with them. They may be part of a solution but likely won't completely replace centralized platforms in the foreseeable future.

What can ordinary people do about internet censorship if they're affected by it?

Organizations like Amnesty International and the Electronic Frontier Foundation accept reports of censorship, which help document and publicize the problem. Supporting digital rights organizations working on policy change is valuable. Using circumvention tools requires caution but is possible for tech-savvy users. Advocating through political channels for digital freedom protections is long-term work. International pressure from diaspora communities can also be effective, though it's often slow.

Conclusion: The Future of Digital Freedom

Uganda's partial internet restoration with social media restrictions isn't a technical story or even primarily a political story. It's a story about the future of communication, control, and freedom in a world where the internet has become as essential as electricity.

What happened is clear: a government facing political pressure used technology to surgically silence the communication platforms where opposition could organize and spread quickly. They maintained plausible deniability by keeping the general internet open. They created a solution to the technical problem of mass internet shutdown while preserving the political benefit of controlling critical communication channels.

It worked because the technology exists, because ISPs can implement it, because citizens had imperfect workarounds, and because most of the world's attention was elsewhere.

The concerning part is that this approach will almost certainly spread. It's technically elegant. It's politically useful. It's economically less destructive than total shutdowns. Other governments will adopt similar measures. The technology will improve. VPN providers will get better at circumvention, governments will get better at blocking circumvention, and the arms race will accelerate.

What's being decided right now in Uganda and similar situations is whether the internet remains a global commons where information flows freely across borders, or whether it becomes a collection of national networks each controlled by their respective governments. Whether young people in authoritarian countries can access the same internet as young people in democracies, or whether digital apartheid becomes normal.

This isn't just about social media. It's about whether technology empowers people or governments, whether information flows or stagnates, whether the future looks like the open internet vision of the early 2000s or the fractured, controlled internet of authoritarian regimes scaling up their capabilities.

The outcome isn't determined. Organizations worldwide are working to preserve digital freedom. Activists are building tools and developing strategies. International pressure exists. Democratic countries are (at least theoretically) defending open internet principles.

But the momentum is concerning. Governments are winning the arms race. Technology is scaling up. Citizens are adapting and finding workarounds, but they're always one step behind.

What happens next depends on choices made by governments, tech companies, civil society organizations, and individual users. Whether we maintain a global internet or fragment into regional systems. Whether censorship becomes more sophisticated or more visible. Whether digital freedom becomes a universal right or a regional privilege available only in democracies.

Uganda is a case study in a much larger story still being written.

Ready to Secure Your Digital Freedom?

If you're concerned about internet privacy and digital freedom, taking action matters. Whether you're in a censored country looking for circumvention tools, a business working across multiple countries dealing with internet fragmentation, or simply someone who believes in open internet principles, there are steps you can take.

Support organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Amnesty International that fight for digital rights. Learn about and consider using privacy-respecting tools. Stay informed about censorship issues in different countries. And remember: the internet's future is being shaped right now by decisions made in Uganda, China, Iran, and dozens of other countries. Paying attention to those decisions matters.

Key Takeaways

- Uganda blocked social media and messaging apps while restoring general internet, revealing sophisticated approach to digital censorship that avoids economic damage of total shutdowns

- Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology enables governments to surgically block specific applications while leaving general internet functional, making censorship less detectable

- VPN usage surged to record levels as citizens sought circumvention, but governments are increasingly blocking VPNs themselves, creating escalating technological arms race

- Selective blocking approach is spreading globally, with at least 70 countries using DPI-based blocking, shifting away from crude full-internet shutdowns toward precision control

- Internet censorship creates cascading economic damage through disrupted business operations, reduced investment, brain drain, and innovation decline that extends far beyond direct user impact

Related Articles

- Discord Blocked in Egypt: Why VPN Usage Spiked 103% [2025]

- VPN Uganda Internet Shutdown: What Happened & Workarounds [2025]

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

- Wikipedia's Existential Crisis: AI, Politics, and Dwindling Volunteers [2025]

- Cloudflare's $17M Italy Fine: Why DNS Blocking & Piracy Shield Matter [2025]

- Pakistan VPN Blocking: What You Need to Know [2025]

![Uganda Internet Restored But Social Media Blocked: What's Really Happening [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uganda-internet-restored-but-social-media-blocked-what-s-rea/image-1-1768842531642.jpg)