UK Social Media Ban for Under-16s: What You Need to Know [2025]

Imagine a world where your teenager can't access TikTok, Instagram, or Snapchat—not because you blocked it, but because the government did. That's not science fiction anymore. It's the future the UK is seriously considering.

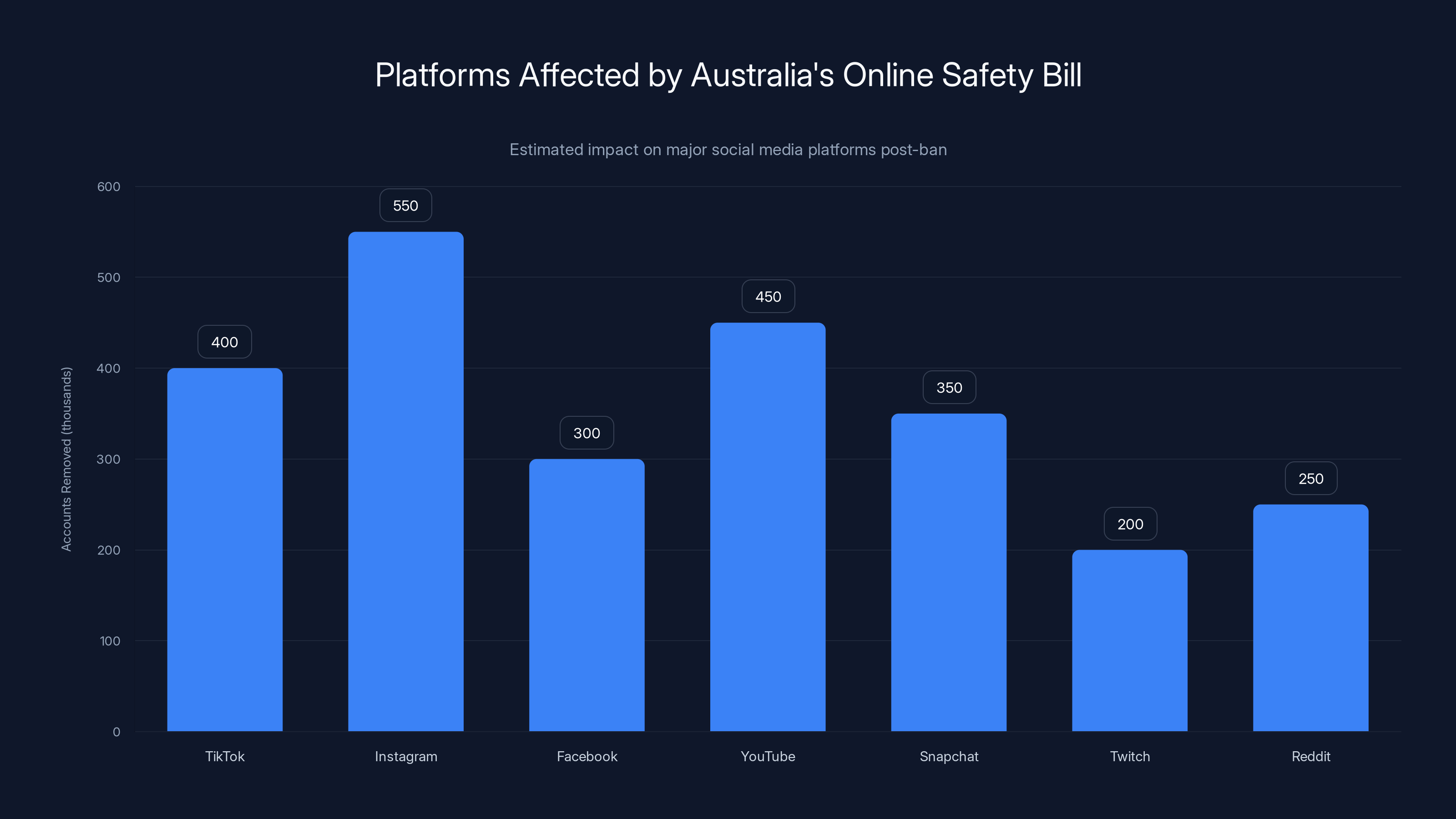

Last year, Australia became the first country to implement a sweeping social media ban for anyone under 16. Within weeks, Meta shut down nearly 550,000 accounts to comply. Now the UK is watching closely, asking the public whether it should follow suit. And based on what I'm seeing in policy circles, this isn't just talk. It's the beginning of something big.

Here's what's actually happening, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- Australia went first: The world's first social media age ban took effect December 10, 2024, covering TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, X, YouTube, Snapchat, Twitch, and Reddit.

- UK is exploring options: The government is consulting on a similar ban while studying Australia's implementation challenges.

- Enforcement is the real problem: Tech companies can't reliably verify age, meaning any ban relies on ID systems that don't currently exist.

- Mental health wins, practical questions remain: Supporters cite depression and anxiety data; critics worry about isolating vulnerable teens and unintended consequences.

- This will happen elsewhere too: If the UK passes it, expect Canada, EU countries, and others to follow within 18 months.

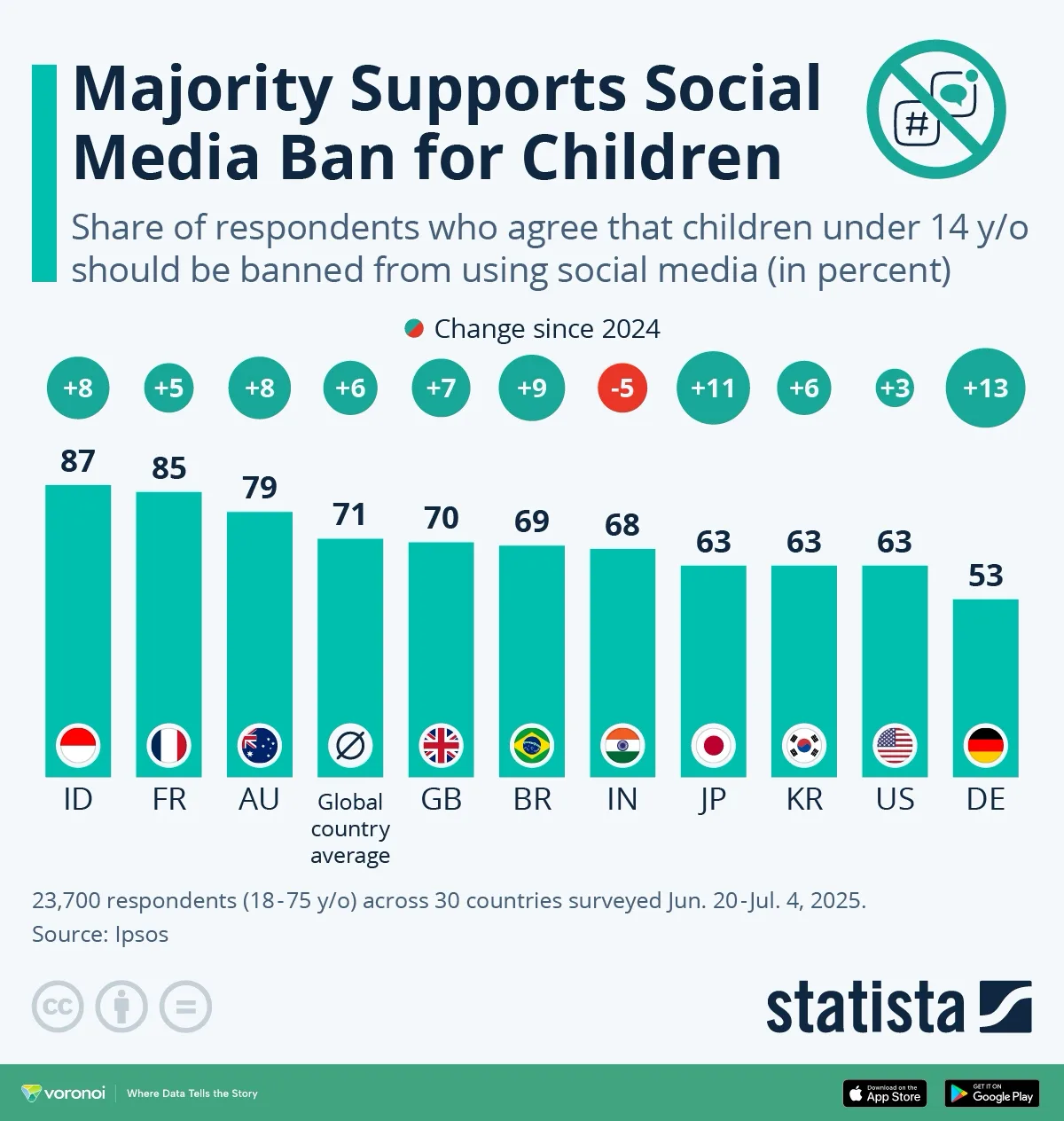

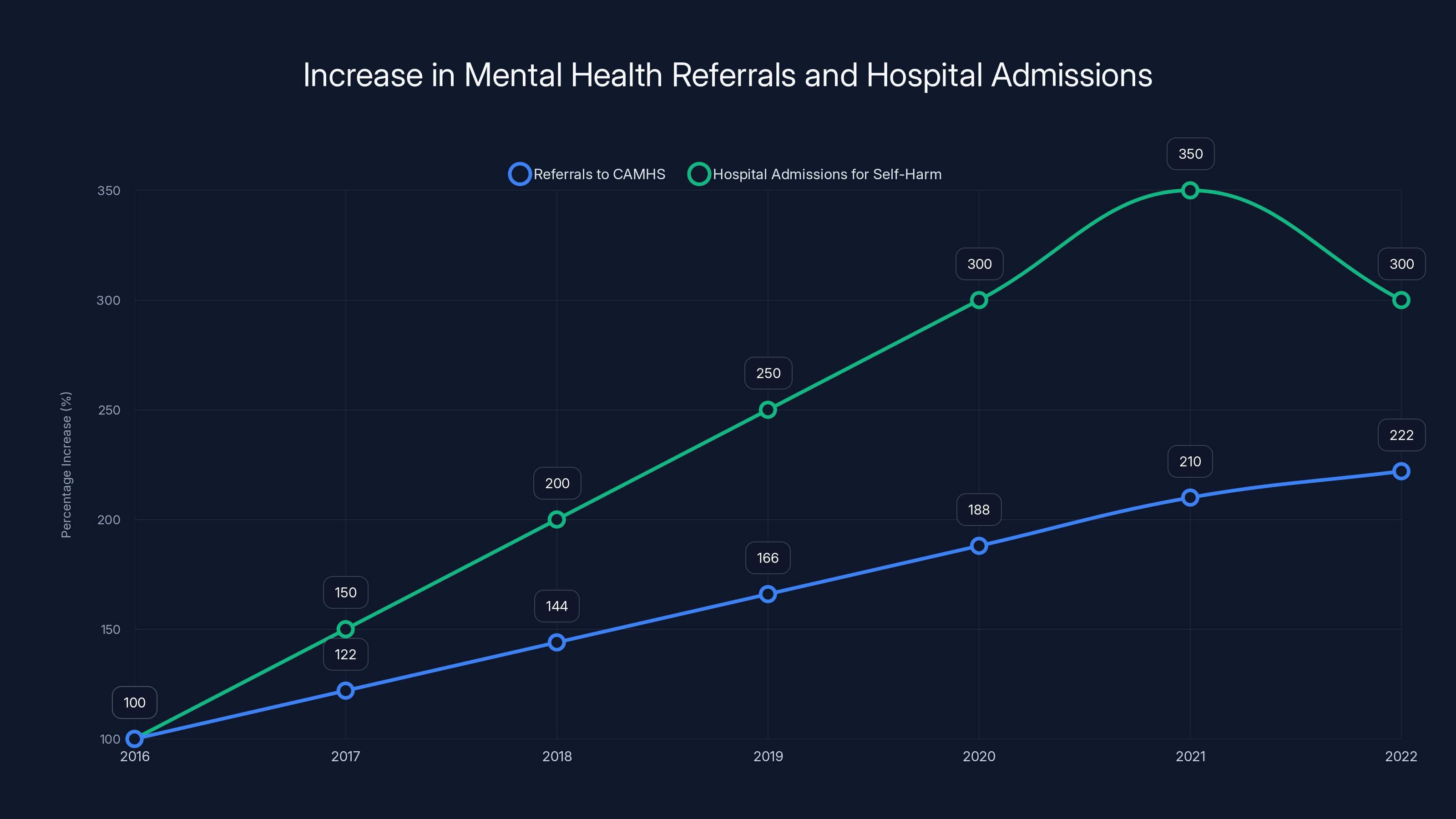

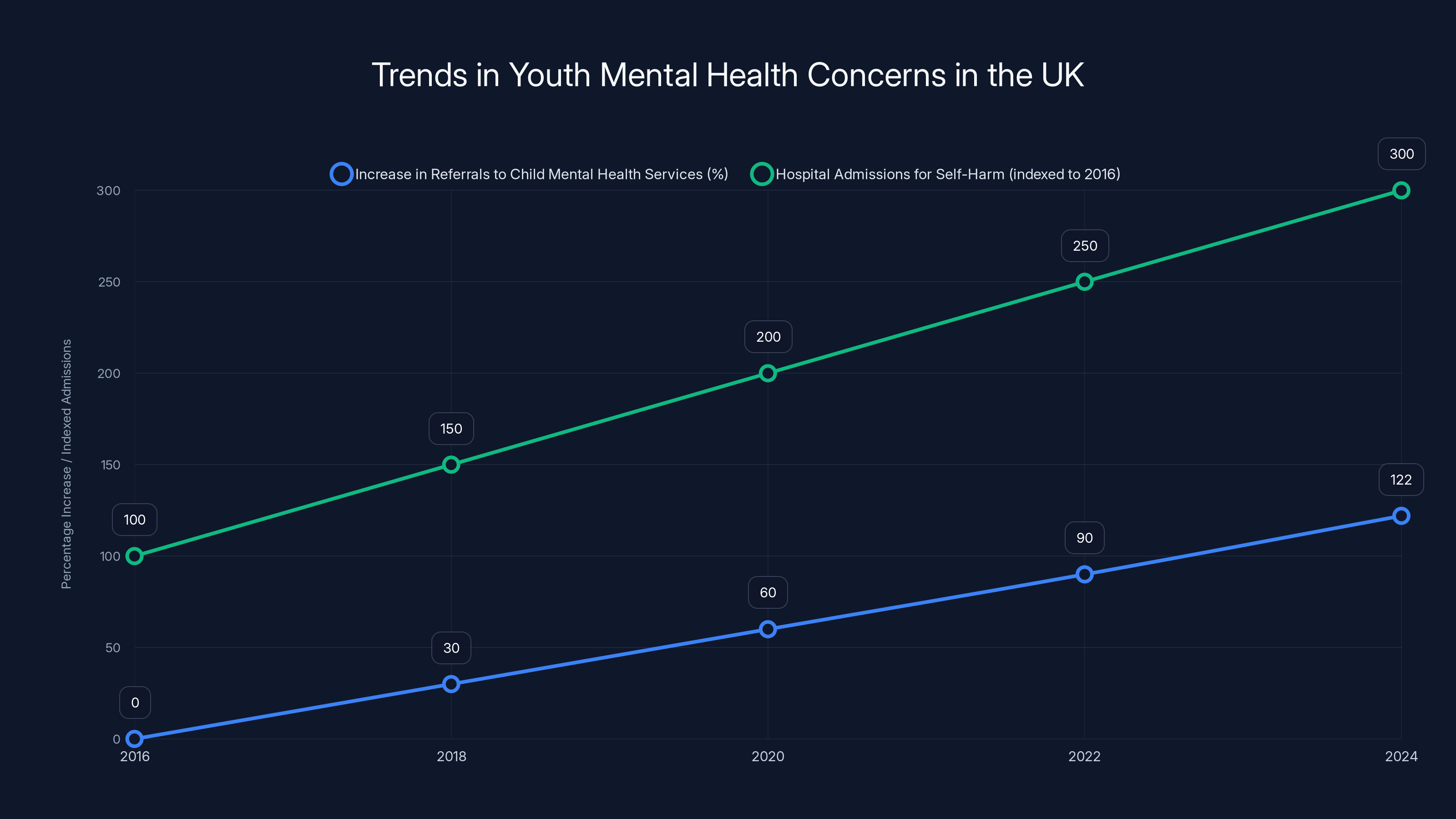

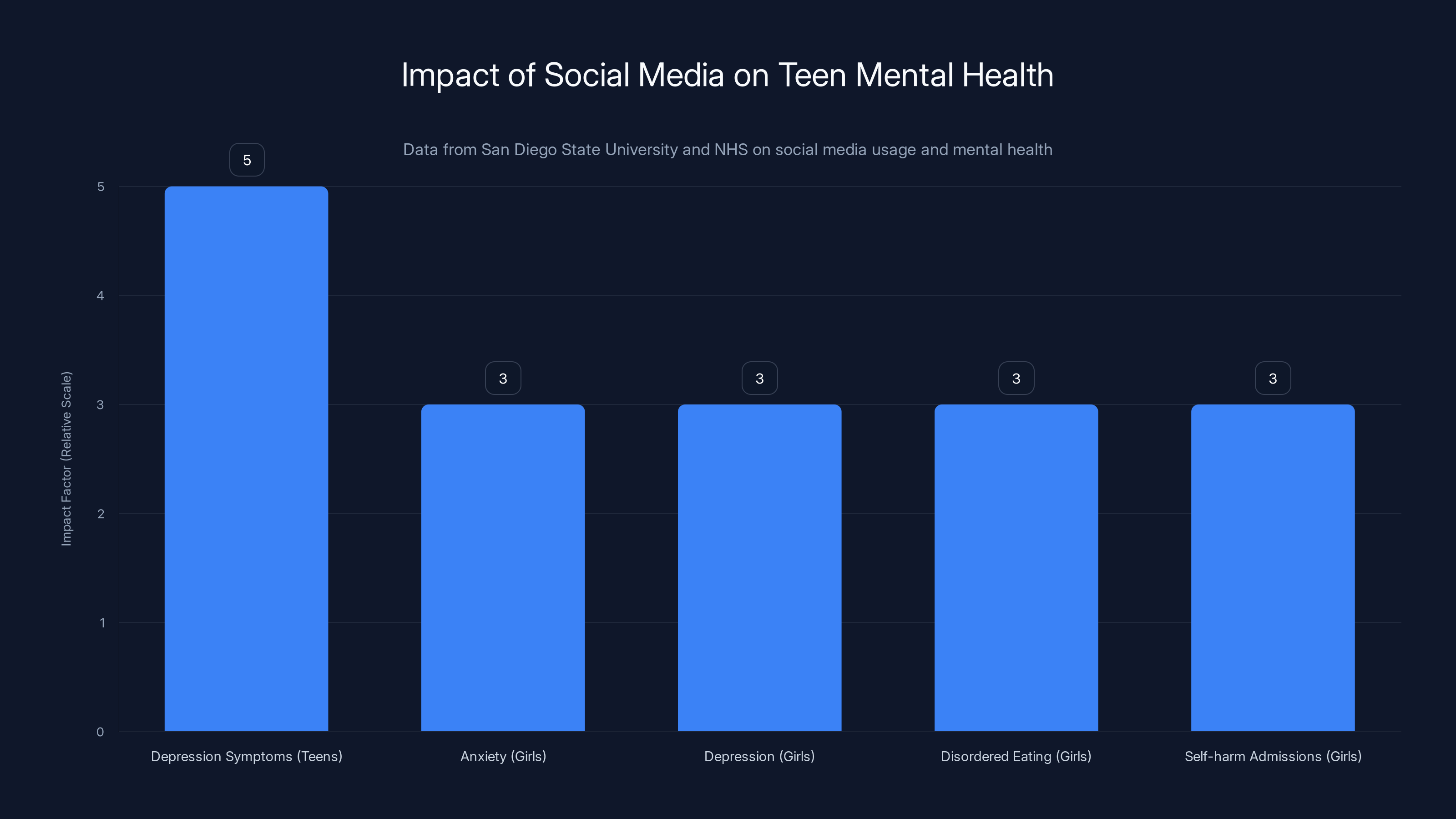

The NHS reports a 122% increase in referrals to child and adolescent mental health services and a tripling of hospital admissions for self-harm among girls aged 10-14 since 2016. Estimated data based on reported trends.

What Exactly Is the UK Proposing?

Let's be clear: the UK government isn't announcing a ban tomorrow. They're asking questions. In early 2025, the UK began a formal consultation period, inviting feedback from parents, teenagers, educators, mental health experts, and tech companies. The consultation asks three specific things.

First, should there be a minimum age requirement for social media? Second, if yes, how should it be enforced? Third, how should the government limit tech companies' ability to collect children's data and deploy addictive features like infinite scroll?

This consultation is scheduled to conclude before the House of Lords votes on an amendment to the Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill. That amendment would mandate a social media ban for under-16s, with implementation within one year if passed.

The UK passed the Online Safety Act in 2023, which already requires age verification for pornographic websites. So the legal infrastructure exists. What doesn't exist is a clear method for age-gating social media without creating mass privacy violations or driving kids to unregulated alternatives.

How Australia's Ban Actually Works

Australia's Online Safety (Basic Online Privacy Expectations) Bill became law in November 2024 and took effect December 10, 2024. It's not a soft suggestion. It's a hard age 16 minimum.

The platforms affected are massive: TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, X, YouTube, Snapchat, Twitch, and Reddit. Any platform the government considers a "social media service" can be added. The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) has enforcement power.

Inside the first week of December, Meta reported removing 550,000 accounts primarily from Instagram. Those accounts appeared to belong to users under 16 based on their data. But here's the thing nobody talks about: Meta doesn't actually know the age of most users. They delete based on heuristics. Behavioral patterns. User-reported birthdays (which anyone can fake). Device location data.

So when people say "Meta removed accounts," what they actually mean is "Meta's algorithms guessed which accounts probably belonged to kids." Some were right. Some probably weren't.

The platform's approach was reactive, not proactive. They didn't implement new authentication systems. They didn't partner with government ID verification. They looked at existing user data and made educated guesses about who was likely a minor, then removed those accounts.

For Australian teens, the experience was immediate disruption. Teens who'd built audiences, sold products, or ran communities suddenly lost access. Some switched to VPNs (which violate the law). Some created new accounts with fake birthdays. Some just stopped using the platforms.

The Australian government hasn't reported enforcement actions against individual users yet. The focus is on platform compliance. But the law technically allows fines up to 49.5 million Australian dollars (about $33 million USD) per violation.

Since 2016, there has been a 122% increase in referrals to child mental health services, with hospital admissions for self-harm among young girls tripling. Estimated data based on reported trends.

Why the UK Wants to Do This

It's not random policy. It's not a kneejerk reaction. The momentum behind this comes from genuine concerns about youth mental health.

The data is concerning. A 2024 King's College London study found that teens using social media for more than three hours daily have higher rates of depression and anxiety. That's not causal proof (correlation isn't causation), but it's consistent with dozens of other studies showing similar patterns.

In the UK specifically, the NHS has seen a 122% increase in referrals to child mental health services since 2016—the year Instagram Stories launched and TikTok became globally available. Hospital admissions for self-harm among girls aged 10-14 tripled in the same period.

British lawmakers point to these statistics when justifying the consultation. They're not wrong about the trends. Whether social media causes them or whether depressed kids seek out social media remains unclear. But the policy momentum doesn't wait for perfect causality.

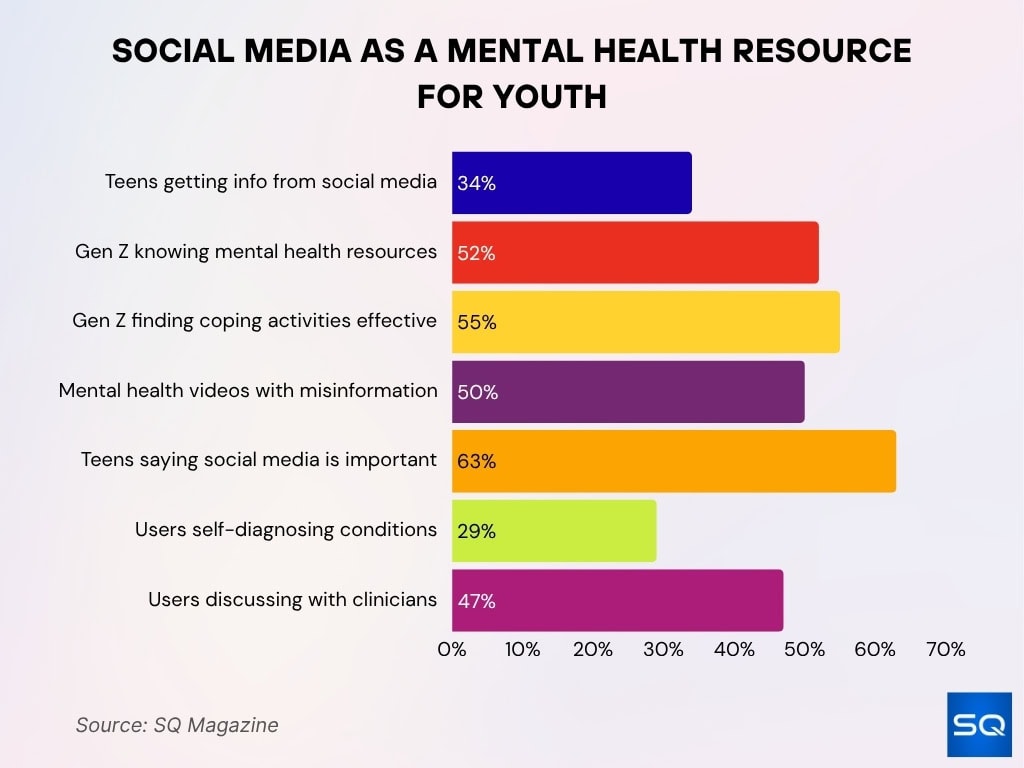

There's also a social media literacy problem. TikTok's algorithm learns from user behavior and recommends increasingly extreme content. A teen watching funny dance videos can find themselves in a rabbit hole of eating disorder content, body dysmorphia trends, or even self-harm instructions within 20 minutes. That's not theoretical. That's how the algorithm works.

Influencer culture creates unhealthy comparison dynamics. Instagram's "influencer" economy pressures teens to maintain perfect image curation, leading to documented increases in body image anxiety.

Then there's the data collection angle. Social media platforms track everything. Location, browsing history, what you pause on, how long you look at content, which ads you hover over. They build detailed profiles of teenagers and sell that data (directly or indirectly) to advertisers. An 8-year-old's data profile is valuable. Meta's entire business model depends on surveillance.

These aren't exaggerations. These are how the platforms operate.

So the UK's rationale is: remove the platforms, remove the mental health risks, remove the data collection, remove the algorithmic rabbit holes. It's a radical solution to a real problem.

The catch is that it might not work the way proponents hope.

The Mental Health Arguments: The Data Behind the Ban

Let's dig into the actual mental health evidence, because this is the emotional core of the ban debate.

Research from San Diego State University found that teens who use social media more than five hours daily are five times more likely to exhibit depression symptoms. That's striking. But here's the methodological caveat: that same research found that correlation existed but causality remained uncertain.

The American Psychological Association released a guidance document in 2023 noting that heavy social media use among girls correlates with increased anxiety, depression, and disordered eating. For boys, the correlations are weaker. The data suggests social media affects girls more negatively than boys, possibly due to algorithmic prioritization of appearance-focused content (Instagram's algorithm learns that appearance content drives engagement from female users, so it recommends more of it).

The UK's mental health evidence specifically comes from NHS data. Over the past decade, NHS referrals to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) increased 122% for girls aged 10-14. Hospital admissions for self-harm among girls the same age tripled. Online bullying is reported by 45% of UK teens who use social media.

That's not made up. Those numbers are real.

But here's where causality gets murky. The pandemic happened. Cost of living increased. Brexit uncertainty created stress. Educational pressure intensified. These are all confounding variables. A teen might be depressed because their family is struggling financially, their school is underfunded, and they're social media-addicted. Which one caused the depression? Probably all of them, differently, for different teens.

The mental health argument for the ban is: remove one variable, see if outcomes improve. That's reasonable. But it assumes social media is the primary variable. If it's not, removing it won't fix the problem.

The Counterargument: Why a Ban Might Backfire

The case against a UK ban is equally compelling, and it focuses on three things: enforcement impossibility, unintended harm, and alternative solutions.

Enforcement is practically impossible. Here's the hard truth: there's no reliable way to verify age online without creating privacy nightmares or implementing government ID systems that are expensive and vulnerable to abuse.

Tech companies could require government ID verification. But that means the government or a third party has a database linking every teenager's social media account to their legal identity. That's a surveillance apparatus that could be misused for tracking protesters, persecuting minorities, or worse. No Western democracy has successfully implemented this without significant privacy concerns.

Alternatively, platforms could use age verification through third-party services. But those services have massive data breach records. Age verification companies holding the birthdates and identity documents of millions of teenagers sounds great until someone hacks it.

So what will actually happen? Teenagers will use VPNs to bypass geographic restrictions. They'll create accounts with fake birthdates (which is trivial). They'll use workarounds. Australia's been enforcing their ban for two months, and anecdotal reports already show teenagers bypassing it easily.

Isolation of vulnerable teens. Here's a harder argument to make, but it's legitimate: some teens use social media as a mental health lifeline.

A teenager with a rare disease connects with others like them through TikTok support communities. A queer teen in a conservative area finds their community online because it doesn't exist locally. A teen with severe social anxiety practices social skills through Discord communities before attempting real-world interaction.

A blanket ban doesn't distinguish between addictive-but-harmless scrolling and genuinely therapeutic community connection.

Australia's ban has already created stories of teens feeling isolated, losing their support communities, or struggling without the connection that helped them manage depression. That's not theoretical. That's already happening.

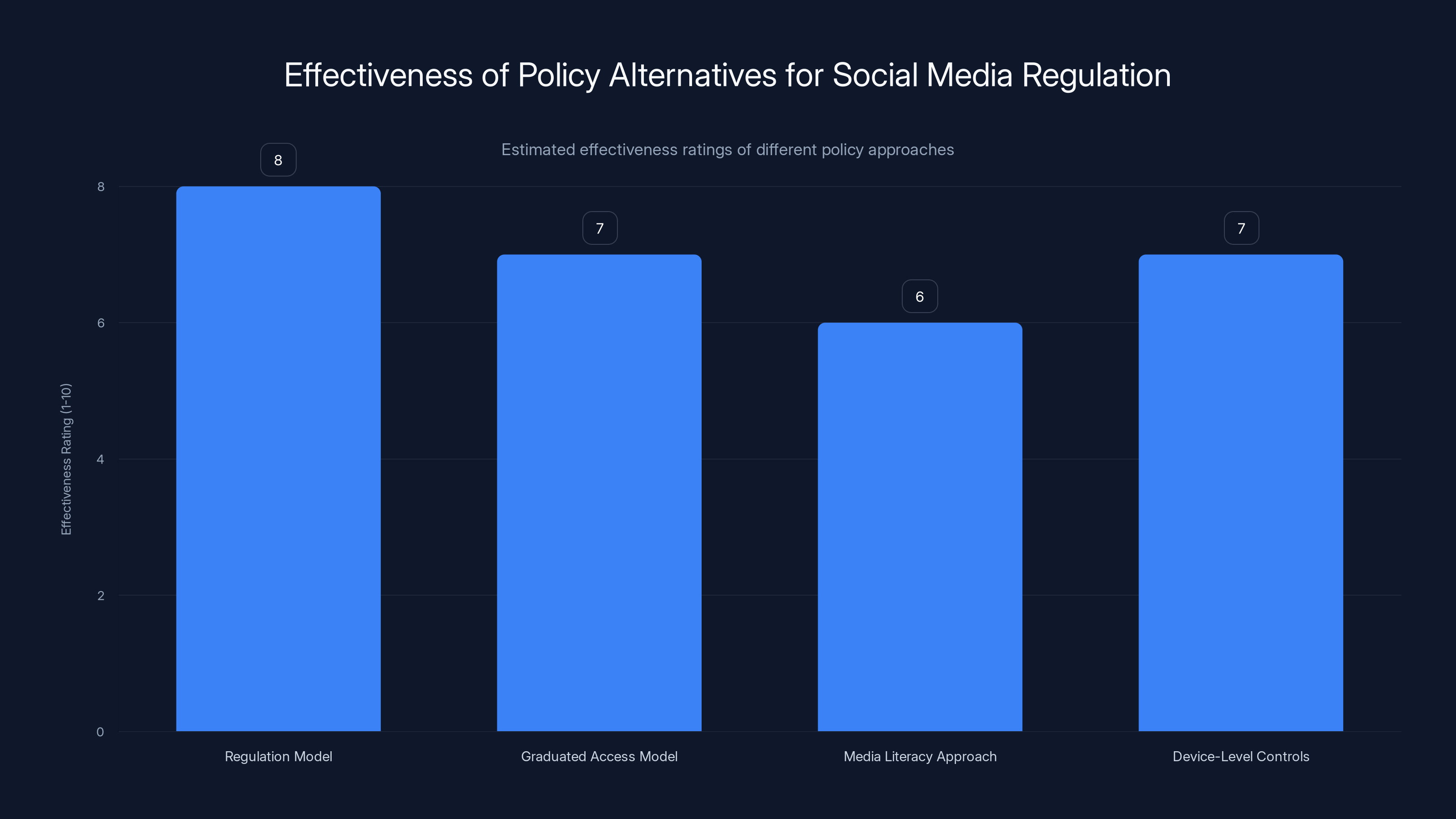

Better alternatives exist. Regulation doesn't require a ban. The EU's Digital Services Act requires platforms to limit algorithmic recommendations for minors, provide better parental controls, reduce data collection on minors, and implement transparent moderation. No ban. Just rules.

The UK could implement something similar: mandatory parental controls (not optional), limits on algorithmic recommendations for under-18s, prohibition on targeted advertising to minors, and transparency requirements for content moderation decisions.

These approaches address the core harms without the sledgehammer effect of a complete ban.

Research indicates that heavy social media use is linked to increased mental health issues among teens, particularly girls. Estimated data reflects relative impact based on studies.

The Enforcement Nightmare: How to Actually Stop Teens

This is where the policy breaks down in practice.

Australia's ban takes effect, and within days, teenagers figure out workarounds. Some download TikTok from app stores in other countries. Some use VPNs. Some use private browsers that mask location data. Some borrow older siblings' accounts. Some create new accounts with older friends' information.

The Australian government hasn't announced enforcement against individual users partly because it's impractical and partly because it's politically unpopular. Prosecuting 15-year-olds for having Instagram accounts doesn't look good.

So enforcement falls on platforms. Platforms are told: "Stop minors from accessing your service." But platforms don't actually know who's a minor because most users provide fake birthdays.

Device-based verification could theoretically work. An Australian Apple ID registered as a child could be prevented from accessing social apps. But this requires device manufacturers, Apple and Google, to enforce government age restrictions. Apple's already hostile to government mandates. They'd likely resist heavily.

IP-based geoblocking is trivial to bypass with a VPN. Facial recognition age detection is inaccurate, raises privacy concerns, and can be bypassed with makeup, filters, or borrowing someone else's face data.

The honest answer is: there's no perfect enforcement mechanism. Any ban creates a cat-and-mouse game where teenagers try to access platforms and platforms try to stop them, and both sides are playing with incomplete information.

UK policymakers know this. They're watching Australia's implementation closely specifically because Australia's running the experiment first. If Australian enforcement proves easier than expected, the UK moves forward. If it's a chaos, the UK might reconsider.

Data Privacy and Collection: The Other Half of the Ban

The UK consultation also asks about limiting data collection on children. This is actually where a ban could have significant benefits independent of the mental health argument.

Social media platforms collect and retain data on minors in ways that would trigger GDPR violations if applied to EU residents. But because most of the collection happens in the US (where social platforms are based), GDPR doesn't fully apply.

A 13-year-old's Instagram data includes:

- Location history from every geotagged post

- Behavioral data (how long they look at each post, when they're most active)

- Interest profiles (inferred from likes, comments, search history)

- Purchase history and intent (which products they look at, which they buy)

- Biometric data (if they've used face filters or video stories)

- Social graph (everyone they follow, everyone who follows them)

- Emotional state predictions (Instagram's algorithms make inferences about mood based on content engagement patterns)

That's not privacy. That's surveillance. And it's sold or used to target advertisements.

If a UK ban includes restrictions on data collection from minors, that could actually be more valuable than the access restriction itself. A rule saying "no targeted advertising to under-16s" or "no behavioral data retention for minors" would be genuinely protective.

But platforms would fight that harder than they'd fight an age verification ban. Data is their entire business model.

International Precedent: What Other Countries Are Watching

The UK and Australia aren't alone in this conversation. Dozens of countries are developing their own positions.

Canada has a task force studying the question. They're likely 12-18 months behind the UK in implementation but moving in the same direction.

The EU is taking a different approach. Rather than bans, they're implementing the Digital Services Act, which requires platforms to limit algorithmic recommendations for minors, provide transparency, and implement robust content moderation. It's regulation without prohibition.

France is somewhere in the middle. They're exploring an age verification system that doesn't require government ID but uses third-party verification services.

The US is gridlocked. There's political will for restrictions on TikTok (for national security reasons, not mental health reasons). There's less willingness for broad social media bans. The US approach is likely to be state-by-state legislation rather than federal bans.

Asia-Pacific countries (Singapore, Japan, South Korea) are watching Australia closely but moving slowly. Their social media ecosystems are different (more WeChat, less Instagram), so direct comparisons don't apply.

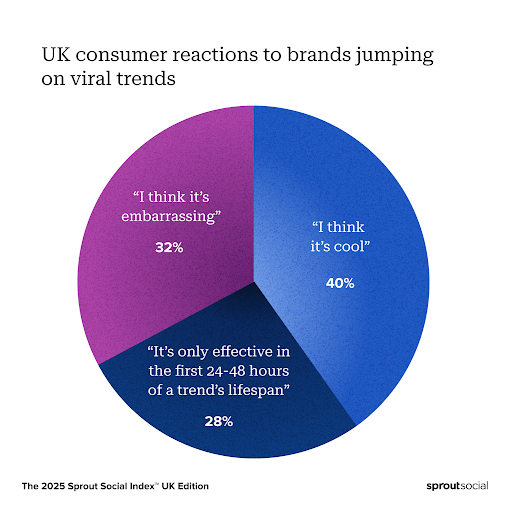

The pattern is clear: Western democracies are moving toward restricting teen social media access or data collection. Some via bans, some via regulation. But the trend is unified.

If the UK passes a ban, it becomes a precedent for other countries. "If the UK did it, we can do it" becomes the argument. You could see a cascade of bans in 2025-2027.

Estimated data suggests Instagram saw the highest number of account removals, with 550,000 accounts affected, as platforms reacted to Australia's age restriction law. (Estimated data)

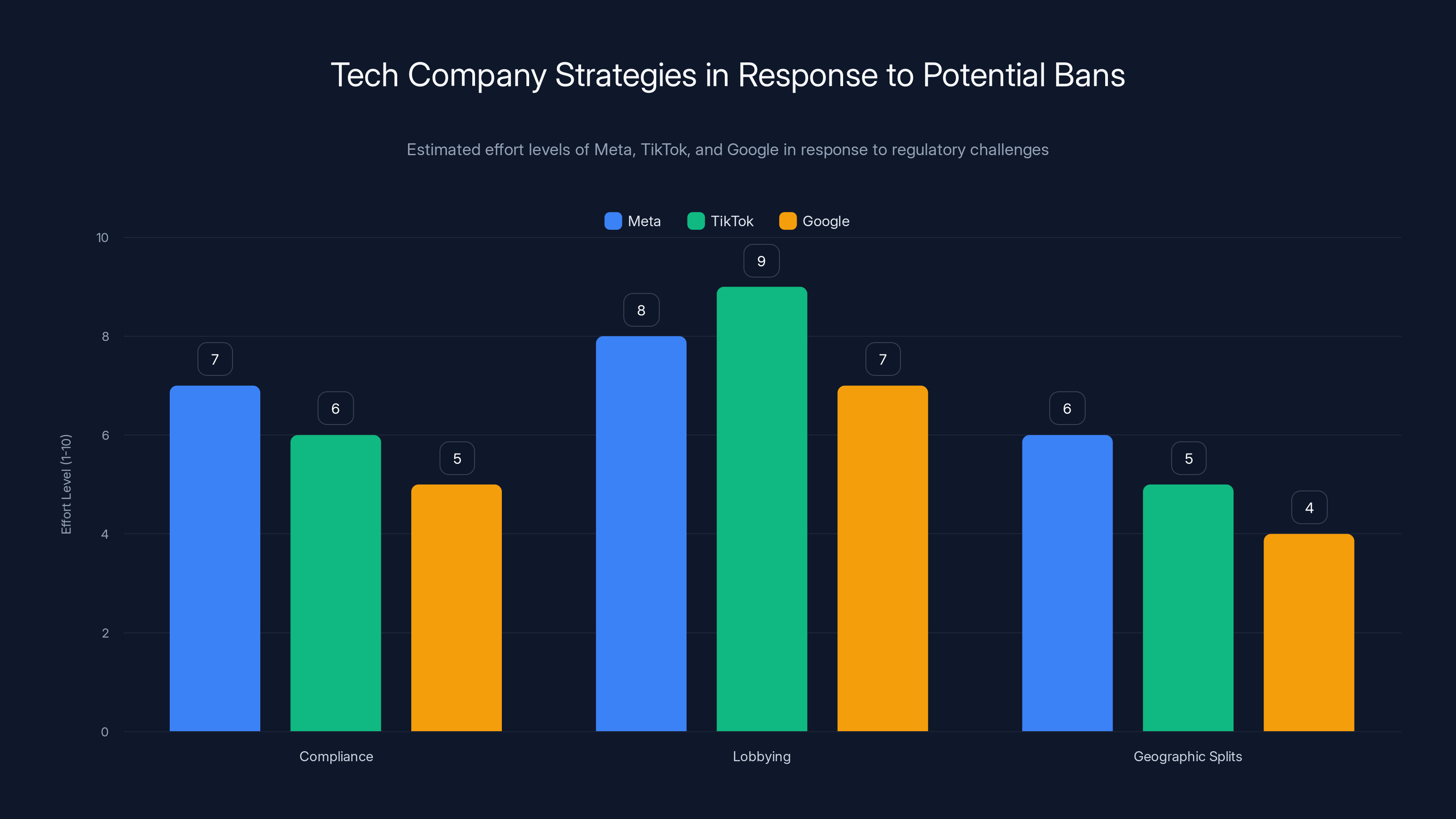

Tech Company Response: Meta, TikTok, and Google React

Tech companies are handling this in three ways.

Compliance with compliance theater. Meta's response in Australia was to remove accounts they guessed belonged to minors. That's technically compliance. It's not actually solving the problem (teenagers can rejoin with new accounts), but it lets Meta say they're complying.

For the UK, you'd expect similar responses. Major platforms will implement age verification requests, show that they're "trying," and privately hope the ban doesn't pass because it would destroy their teen user base (which is increasingly valuable as adult users spend less time on social media).

Lobbying. Tech companies are spending significant money lobbying against bans while publicly acknowledging mental health concerns. That's strategy. Acknowledge the problem. Propose "our own solutions" (which they've already proven don't work). Lobby against government mandates. Hope the political will fades.

Geographic splits. Some companies might simply restrict access to UK users under 16 in the UK while maintaining access elsewhere. That's possible and arguably easier than the alternative. Instagram could show an error message to UK IP addresses without a verified age claim.

But there's a deeper issue for tech companies. If Australia's ban succeeds, if the UK passes a ban, and if other countries follow, then the entire teen user demographic (a huge revenue source) disappears in major markets. That's existential.

So tech companies are fighting hard, just quietly. They're funding studies about the benefits of social media. They're developing "youth-safe" features (that they'll tout as solving the problem). They're building relationships with UK politicians. It's not a direct fight; it's a longer-term strategy.

Parental Control Reality: What Parents Can Actually Do Now

Waiting for government policy is passive. Here's what parents can actually control today.

Install parental control apps. Apps like Apple's Screen Time, Google Family Link, or third-party tools like Bark or Life360 give you actual control over device usage. Most social media platforms also have built-in parental controls (Instagram's Family Center, TikTok's Family Pairing) that work if you set them up.

Understand the algorithm. Most parents don't understand how social media algorithms work. TikTok's algorithm learns from what you watch and recommends more of it. If your teen watches one eating disorder video, the algorithm will serve 20 more because engagement is the goal. Knowing this means you can have smarter conversations with your teen about it.

Have uncomfortable conversations. Ask what they're actually using social media for. Are they building real friendships? Consuming aspirational content that makes them feel bad? Being bullied? Getting exposed to extremism? The answer matters, because the interventions are different.

Model good behavior. If you're doom-scrolling Instagram for two hours while telling your teen not to use TikTok, that's not persuasive. Your behavior is the most powerful parenting tool you have.

Consider alternatives. Some families set boundaries (no social media until 14, limited use after that, no phones in bedrooms). Others require a chore chart for screen time. Some families do phone-free dinners. These aren't revolutionary, but they work if you're consistent.

The hard truth is that parental involvement works better than government bans. But parental involvement requires effort, which is why bans are politically attractive. They require nothing from parents. The government does the work.

The Timeline: When Might This Actually Happen?

If the UK passes this ban, what's the realistic timeline?

2025 Q1-Q2: UK consultation period concludes. Feedback is compiled and analyzed. Government issues a white paper summarizing responses.

2025 Q3-Q4: House of Lords votes on the amendment to the Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill. If it passes, the government has one year to implement.

2026: Implementation period. Platforms adjust their systems. Age verification infrastructure gets built. Enforcement mechanisms are developed.

2026-2027: Enforcement begins. Platforms remove accounts. Teenagers work around it. The government measures effectiveness.

This isn't speculative. Australia's ban took about 18 months from announcement to implementation. The UK would likely follow a similar timeline.

For other countries: Canada 12-18 months behind UK. EU potentially faster (their regulatory apparatus is different). US likely 24+ months behind due to political complexity.

So if you're a parent or educator, 2026-2027 is when major changes would start affecting teens. That's soon. Not immediate, but soon enough that it should be on your radar.

The regulation model is estimated to be the most effective approach, with a rating of 8 out of 10, due to its comprehensive rules and potential for reducing harms without banning access. Estimated data.

Unintended Consequences: What Could Go Wrong

Bans always create unintended consequences. Here are the realistic ones.

Underground platforms. If mainstream social media becomes inaccessible to UK teens, they migrate to less moderated, less safe alternatives. Think 4chan, Reddit (which is banned but easier to access via VPN than TikTok), or private Discord communities with no oversight.

Fewer people monitoring for child exploitation, harassment, or extremist radicalization. That's worse, not better.

VPN adoption. Teenagers learning to use VPNs to bypass age restrictions is a skill they'll keep using for other purposes. It normalizes circumventing legal restrictions. That's not a trivial consequence.

Mental health paradox. If vulnerable teens lose their support communities, you might see increased mental health problems, not decreased. That's not speculative; it's already happening in Australia.

Socioeconomic divide. Wealthy teens with family connections might maintain access. Poor teens lose it. That creates a class divide in who has access to certain communities and opportunities.

Extremism concerns. In some cases, social media serves as a pressure valve. Teens who feel isolated can find community online. Remove that, and some might turn to more extreme coping mechanisms or find community in more dangerous places.

These aren't arguments against the ban. They're acknowledgments that bans don't solve problems in vacuum. They create new problems, which then require their own solutions.

The Innovation Question: Could Tech Do Better?

Here's the honest take: social media platforms could be dramatically better for teens, but they're not because the current model is maximally profitable.

A social media platform designed for teen wellbeing would:

- Limit daily usage time with hard cutoffs (not just recommendations)

- Disable autoplay and infinite scroll for minors

- Prevent algorithmic recommendations for identity-sensitive content (eating disorders, self-harm, radical political content)

- Require algorithmic transparency (teens can see why content is recommended)

- Eliminate targeted advertising to minors

- Delete data on minors after 30 days (no long-term behavioral profiles)

- Implement "asynchronous" communication (messaging works, but real-time notifications don't)

- Disable public posting for under-16s (they can message friends, but can't broadcast)

Technically possible. Most of this technology exists. None of it would be expensive to implement.

But it would reduce engagement. Reduced engagement means reduced ad revenue. That's why platforms don't do it.

So the question isn't: "Can technology solve this?" It's: "Will platforms choose to solve it when solving it means making less money?"

The answer historically is no. Regulation is necessary because profit incentives don't align with teen wellbeing.

That doesn't justify a ban necessarily. It justifies serious regulation. And that's what the UK should be working toward.

Global Implications: Domino Effect Risk

If the UK bans social media for under-16s, the implications extend far beyond the UK.

Tech platform economics change. Teen users in major Western markets disappear. That reduces ad-serving opportunities. Revenue from those regions drops. Platform valuations potentially decline.

Other countries follow. "If the UK did it, it's legitimate" becomes the political talking point. Canada, EU countries, Australia doubles down. Within five years, major Western markets ban teen social media access. The platforms then face a decision: accept the ban or exit those markets.

Global social media landscape fractures. If Western countries ban, other countries don't. You get a two-tier internet. Western teens don't have TikTok; Chinese teens do. Western data privacy is higher; other regions are less protected.

Digital divide expands. Teens in wealthy countries lose access to tools that teens in other countries use. That's not necessarily bad, but it does create asymmetry in digital skills and opportunities.

Geopolitical implications. Bans on Chinese social media platforms (TikTok) combined with bans on teen access generally could be seen as Western protectionism against Chinese tech. That feeds into broader trade and geopolitical tensions.

These are second and third-order effects. But they're why governments care about social media policy at the national level. It's not just about teen wellbeing. It's about economic competition, national identity, and geopolitical positioning.

Estimated effort levels show that TikTok is heavily investing in lobbying, while Meta focuses on compliance. All companies are considering geographic splits as a strategic option. Estimated data.

What Should Actually Happen: Policy Alternatives

If a total ban is too blunt, what's the right approach?

Regulation model. Implement rules that require:

- Age verification through third-party services (not government ID)

- Mandatory parental controls that are opt-out, not opt-in

- Algorithmic transparency (platforms must explain why content is recommended)

- Limits on data retention for minors (delete after 30 days)

- No targeted advertising to under-18s

- Hard content restrictions (no access to eating disorder content, self-harm content, or extremist content)

- Public reporting on youth engagement metrics and mental health impacts

This approach maintains access while reducing harms. It requires investment from platforms (which they'll resist) but doesn't require government infrastructure investment or create enforcement nightmares.

Graduated access model. Different platforms for different ages:

- Under 13: No social media, or messaging-only apps

- 13-16: Limited social media with mandatory parental controls and no algorithmic feeds

- 16+: Current social media with restrictions on data collection and advertising

This requires platform modification but maintains access for older teens who have valid uses.

Media literacy approach. Require social media education in schools. Teach teens how algorithms work, why platforms target them, how to spot misinformation. This doesn't solve the addiction problem, but it reduces the damage.

Device-level controls. Rather than banning platforms, require device manufacturers to provide robust parental controls that actually work. Apple and Google have significant leverage here.

Each approach has trade-offs. Bans are politically simple but practically hard and socially risky. Regulation is more complex but potentially more effective. Education takes time but addresses root causes.

The UK should consider all of these before settling on a total ban.

Industry Standards and Emerging Frameworks

There's actually significant movement on youth online safety standards outside of government mandates.

The Internet Watch Foundation has guidelines for age-appropriate content. The Online Safety Institute has developed frameworks for platform accountability. The World Health Organization has published guidance on social media and child development.

But these are voluntary guidelines. Companies follow them when it doesn't hurt revenue. They ignore them when profits are at stake.

What might actually work: international standards with teeth. Something like: "Platforms certified under the Youth Online Safety Standard receive reduced liability in these jurisdictions, but must meet specific criteria regarding teen mental health, data protection, and algorithmic limits."

That creates incentives for compliance without requiring bans.

The EU's Digital Services Act is moving in this direction. The UK could do something similar: regulation that creates incentives for compliance rather than prohibition that creates enforcement nightmares.

Expert Perspectives: What Researchers Actually Say

If you dig into the academic literature, you find remarkable consensus on some points and sharp disagreement on others.

Consensus:

- Social media use correlates with higher anxiety and depression in teens, especially girls

- Algorithmic feeds designed for engagement are psychologically problematic

- Data collection on teens raises serious privacy concerns

- Platform moderation of teen content is inadequate

Disagreement:

- Whether social media causes mental health problems or whether depressed teens seek out social media

- Whether limiting access is better than improving platform design

- Whether bans are enforceable or just create workarounds

- Whether the benefits of online community outweigh the harms

Most researchers in adolescent psychology fall somewhere in the middle. They're concerned about harms. They don't think bans are the right solution. They want regulation and design changes.

That's a more nuanced position than either "ban all social media" or "social media is fine, stop worrying."

Policymakers should probably listen to that nuance rather than picking a corner of the debate.

Practical Steps for 2025: What You Should Do Now

Whether you're a parent, educator, teen, or tech worker, here are concrete steps.

If you're a parent:

- Have conversations with your teen about their social media use

- Set up parental controls now (before they become mandatory)

- Understand the platforms your teen uses

- Model good digital behavior

- Stay informed about policy changes

If you're an educator:

- Teach media literacy before students reach high school

- Include social media in curriculum (not just bans, but understanding)

- Create school policies that address teen social media use

- Support vulnerable students who rely on online communities

If you're a teen:

- Understand how algorithms work

- Notice when apps are designed to keep you using them longer

- Build real-world friendships alongside online ones

- Curate your feed intentionally rather than letting algorithms do it

- Know that you can log off

If you're a tech worker:

- Build products with teen wellbeing in mind, not just engagement

- Push back against features designed to be addictive

- Support transparency about how your company uses youth data

- Consider whether your work is harming kids

Everyone:

- Participate in the UK consultation if you have opinions

- Stay informed about policy developments

- Recognize that this is a complex issue with no perfect solution

- Avoid binary thinking (ban all social media / never regulate it)

FAQ

What exactly is Australia's social media ban?

Australia's ban, which took effect December 10, 2024, prohibits anyone under 16 from accessing social media platforms including TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, X, YouTube, Snapchat, Twitch, and Reddit. Platforms are required to verify age or face fines up to 49.5 million Australian dollars. The ban doesn't cover messaging apps or educational platforms, only services classified as "social media." Within the first week, Meta removed approximately 550,000 primarily Instagram accounts presumed to belong to users under 16.

How does the UK consultation process work?

The UK government has opened a formal consultation period where the public—parents, teenagers, educators, mental health experts, and tech companies—can submit feedback on whether a social media ban for under-16s should be implemented. After the consultation period closes, the government compiles responses and issues a white paper. The House of Lords then votes on an amendment to the Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill. If the amendment passes, the government has one year to implement the ban. This follows the UK's pattern from the Online Safety Act 2023.

What mental health evidence supports a ban?

Research consistently shows correlations between heavy social media use and depression, anxiety, and disordered eating, particularly among teenage girls. The NHS reports a 122% increase in referrals to child and adolescent mental health services for girls aged 10-14 since 2016, and hospital admissions for self-harm in this demographic tripled in the same period. However, causality remains uncertain—social media could cause these problems, vulnerable teens could use social media more, or both could be influenced by other factors like pandemic stress or cost-of-living pressure. Most research experts agree the correlation is clear; whether banning social media will improve outcomes is unproven.

Why is enforcement so difficult?

Age verification online requires either government ID systems (privacy nightmare), third-party verification services (data breach risk), or relying on platform heuristics (which are inaccurate). Teenagers can bypass most technical controls with VPNs, fake birthdays, or borrowed accounts. Within two months of Australia's ban, teens were already circumventing it. Platforms can't distinguish between a 15-year-old and a 16-year-old with certainty without invasive verification. This creates a scenario where enforcement appears stricter than it actually is.

Could a ban isolate vulnerable teens?

Yes. Some teenagers use social media as a mental health lifeline—connecting with peers who have rare diseases, finding LGBTQ+ community in conservative areas, or practicing social skills in a low-stakes environment. A blanket ban doesn't distinguish between addictive scrolling and genuinely therapeutic community. Australia's ban has already prompted reports of teens losing support communities. This is why many experts suggest regulation (limiting harmful features) rather than outright bans.

What's the difference between a ban and regulation?

A ban prohibits access entirely. Regulation sets rules for how platforms operate—limiting algorithmic recommendations, restricting data collection, preventing targeted advertising, requiring parental controls. The EU's Digital Services Act is regulation without bans. It requires platforms to be safer for minors without making the platforms inaccessible. Regulation is more complex to implement but potentially more effective because it addresses specific harms rather than assuming access is inherently harmful.

How likely is it that other countries will follow the UK's lead?

Very likely. Australia set the precedent. If the UK passes a ban and doesn't face catastrophic enforcement problems, you'll see Canada, EU countries, and others follow within 18 months. This creates a cascade effect where bans become normalized. The US is slower to act due to political complexity, but state-level bans are possible. Within five years, major Western markets could have teen social media restrictions.

What would happen to Meta, TikTok, and Google if bans became widespread?

Revenue from those regions would decline significantly. Teen users represent a substantial portion of daily active users and drive ad engagement. Bans in major markets (UK, EU, possibly US) would reduce their addressable audience. Companies would either accept the revenue loss, exit those markets entirely, or modify their products significantly for minors. This creates existential pressure on platforms to either comply with restrictions or challenge them through lobbying and legal action.

Can parents do anything now without waiting for government policy?

Absolutely. Parental control apps like Apple's Screen Time and Google Family Link provide real oversight. Most platforms have built-in parental controls (Instagram's Family Center, TikTok's Family Pairing). Parents can have conversations with teens about algorithm awareness, set boundaries on usage, and model good digital behavior. These approaches are often more effective than government mandates because they're customized to individual families rather than one-size-fits-all.

What would better social media for teens actually look like?

A teen-focused platform would disable infinite scroll, implement hard daily usage limits, prevent algorithmic recommendations for identity-sensitive content (eating disorders, self-harm), eliminate targeted advertising, delete user data after 30 days, require algorithmic transparency, and limit public posting for younger teens. Technically, this is all possible. Economically, it's not profitable because engagement-driven advertising wouldn't work. This is why regulation (requiring these features) rather than bans might be more effective long-term.

What happens to teens who use VPNs to bypass a ban?

This is unclear legally. Australia's ban technically applies to users, not just platforms, but the government hasn't announced enforcement against individual teenagers. VPN use is technically a violation, but prosecuting 14-year-olds for TikTok access would be politically toxic. Most likely, enforcement focuses on platforms, not users. This creates a gray zone where the ban exists but isn't strictly enforced against individuals, leading to a shadow enforcement where determined teens can access platforms but can't do so openly.

Conclusion: What This Means for the Future

The UK's consultation on a social media ban for under-16s isn't just about protecting children from TikTok. It's a pivotal moment for how democracies regulate technology, how we balance innovation with safety, and what role governments should play in protecting young people.

Australia went first. They've shown that bans are possible to implement (though imperfectly). The UK is watching closely, asking whether the model works. And dozens of other countries are waiting to see the outcome before making their own decisions.

Here's my honest take: a total ban is a blunt instrument for a nuanced problem. Social media absolutely harms some teens significantly. It helps other teens by providing community, connection, and support. A one-size-fits-all prohibition doesn't account for that complexity.

What the UK should do is regulate, not ban. Require platforms to verify age through non-invasive methods. Mandate robust parental controls that are opt-out, not opt-in. Eliminate targeted advertising to minors. Limit data collection. Restrict algorithmic recommendations for harmful content. Require algorithmic transparency. These approaches address specific harms without creating enforcement nightmares or isolating vulnerable teens.

But I also recognize I'm an optimist about technology regulation. I think we can design rules that work. Policymakers might reasonably conclude that bans are simpler, even if imperfect, than complex regulation.

What's certain is this: the status quo can't continue. Platforms designed to maximize engagement at the expense of teen mental health, collecting vast data on minors without meaningful consent, algorithmically promoting harmful content—that's not acceptable. Whether the fix is bans, regulation, or some combination matters less than the recognition that change is coming.

If you're a parent, the time to start setting boundaries is now. If you're an educator, build media literacy into your curriculum today. If you're a teen, start thinking critically about how platforms use your attention and data. If you work in tech, consider whether you're building tools that help or harm young people.

The consultation is open. Your voice matters. Policymakers do read public feedback, and where you stand on this issue shapes the internet your kids will inherit.

Because that's what this really is: deciding what kind of digital world we want for the next generation. That's bigger than any single policy decision. That matters.

Key Takeaways

- Australia's social media ban for under-16s took effect December 10, 2024, covering TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, X, YouTube, Snapchat, Twitch, and Reddit, with Meta removing 550,000 accounts in compliance.

- The UK is conducting a formal public consultation on whether to implement a similar ban, with implementation within one year if the House of Lords passes the amendment to the Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill.

- Mental health evidence shows strong correlations: NHS referrals for child mental health increased 122% and self-harm hospital admissions tripled for girls aged 10-14 since 2016, though causality remains uncertain.

- Enforcement is practically impossible through current technology—VPNs, fake birthdays, and borrowed accounts bypass any age verification system, as Australia is already discovering.

- Regulation might be more effective than bans: limiting algorithmic recommendations, restricting data collection, eliminating targeted advertising, and requiring parental controls address specific harms without enforcement nightmares.

- Vulnerable teens using social media for legitimate community support (rare diseases, LGBTQ+ connection, anxiety management) could be harmed by blanket bans that don't distinguish between addiction and therapeutic use.

- If the UK passes a ban, expect Canada, EU countries, and others to follow within 18 months, potentially fragmenting the global internet by jurisdiction and creating a cascade effect on platform economics.

- Parents have immediate tools available now: Apple Screen Time, Google Family Link, and platform-specific controls like Instagram's Family Center and TikTok's Family Pairing can be implemented before any government mandate.

Related Articles

- Apple and Google Face Pressure to Ban Grok and X Over Deepfakes [2025]

- Why Grok's Image Generation Problem Demands Immediate Action [2025]

- xAI's Grok Deepfake Crisis: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Italian Regulators Investigate Activision Blizzard's Monetization Practices [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Crisis: The Ashley St. Clair Lawsuit and AI Accountability [2025]

- Grok's Unsafe Image Generation Problem Persists Despite Restrictions [2025]

![UK Social Media Ban for Under-16s: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uk-social-media-ban-for-under-16s-what-you-need-to-know-2025/image-1-1768916365834.jpg)