Introduction: The Ocean's Hidden Energy Treasure

Imagine tapping into a fuel source so vast that it could power civilization for thousands of years without depletion. This isn't science fiction. It's what China just demonstrated in the South China Sea, where scientists successfully extracted kilogram-scale quantities of uranium directly from seawater under real marine conditions, as reported by TechRadar.

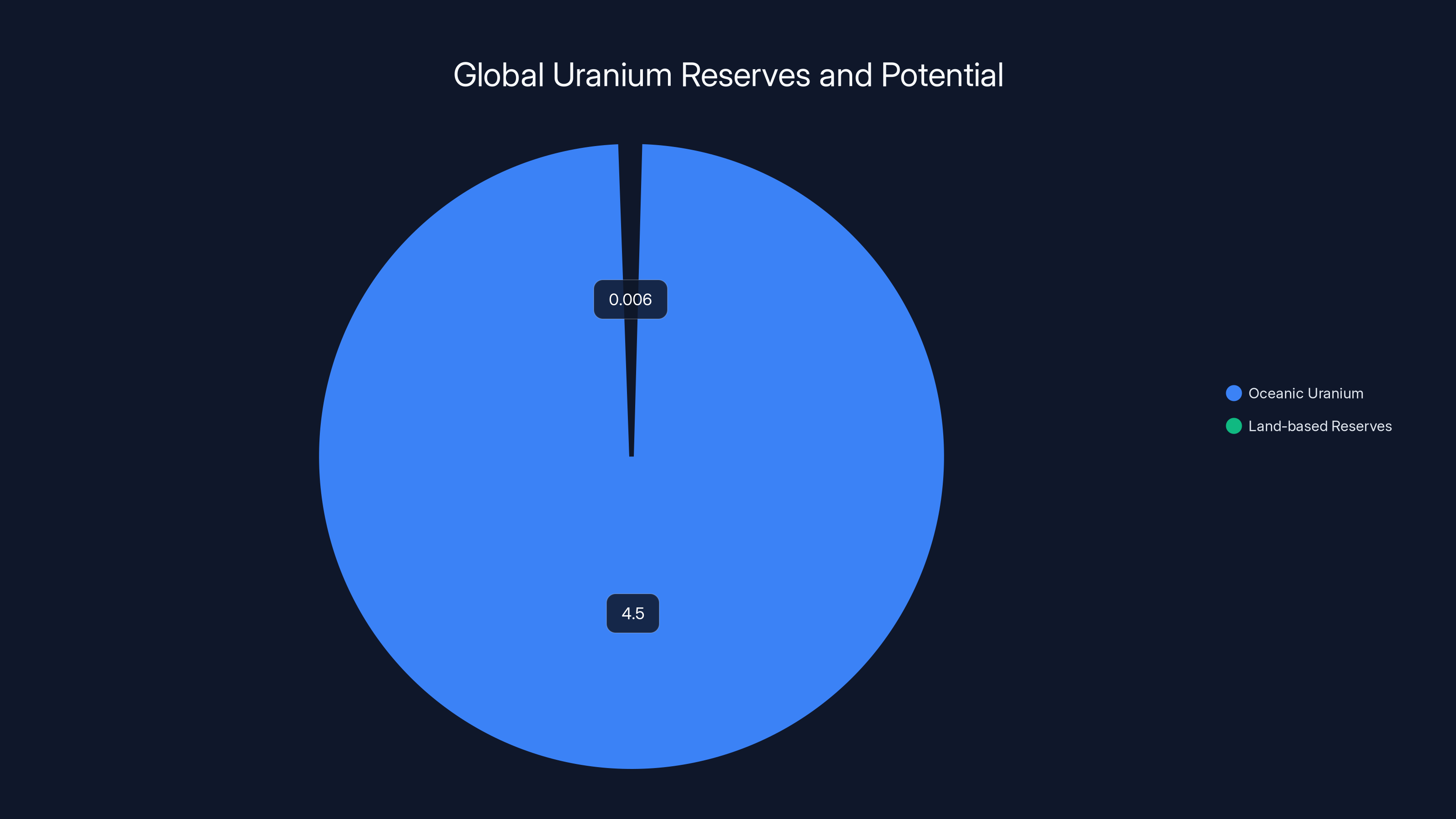

For decades, uranium mining has relied on finite terrestrial deposits scattered across Kazakhstan, Canada, Australia, and a handful of other nations. These deposits are expensive to extract, geopolitically complicated, and increasingly difficult to access as surface reserves deplete. But the ocean tells a different story. Seawater contains roughly 4.5 billion tons of dissolved uranium, continuously replenished by geological processes and river runoff. That's about 1,000 times more uranium than exists in all known land-based reserves combined, according to EurekAlert.

The challenge? Seawater uranium concentration is extraordinarily low, roughly 0.003 parts per million. Extracting it requires overcoming massive technical and economic hurdles: developing materials that selectively absorb uranium while resisting corrosion, deploying them in harsh marine environments, and processing them at a cost per kilogram that actually makes sense. For years, this was theoretical. Now, China's successful demonstration moves it from laboratory curiosity into something that resembles real engineering.

This article explores what China actually accomplished, why it matters, what the obstacles still are, and whether seawater uranium could genuinely reshape the global energy landscape by 2050. The answer is more nuanced than headlines suggest, but the implications are profound.

TL; DR

- Kilogram-Scale Milestone: China extracted 1000g of uranium from seawater under real ocean conditions, moving beyond lab-scale experiments into controlled demonstration territory.

- Immense Resource Base: Oceans contain approximately 4.5 billion tons of dissolved uranium, dwarfing all known terrestrial reserves and offering a theoretically infinite fuel source.

- Enormous Technical Challenge: Current seawater uranium concentration is 0.003ppm, making extraction energy-intensive and economically unproven at commercial scale.

- Strategic Energy Goal: China's 2050 target for "unlimited battery life" ties nuclear fuel availability to long-term civilization energy security.

- Bottom Line: A significant proof-of-concept, but vast gaps remain between extracting kilograms in a test platform and deploying industrial-scale seawater uranium mining globally.

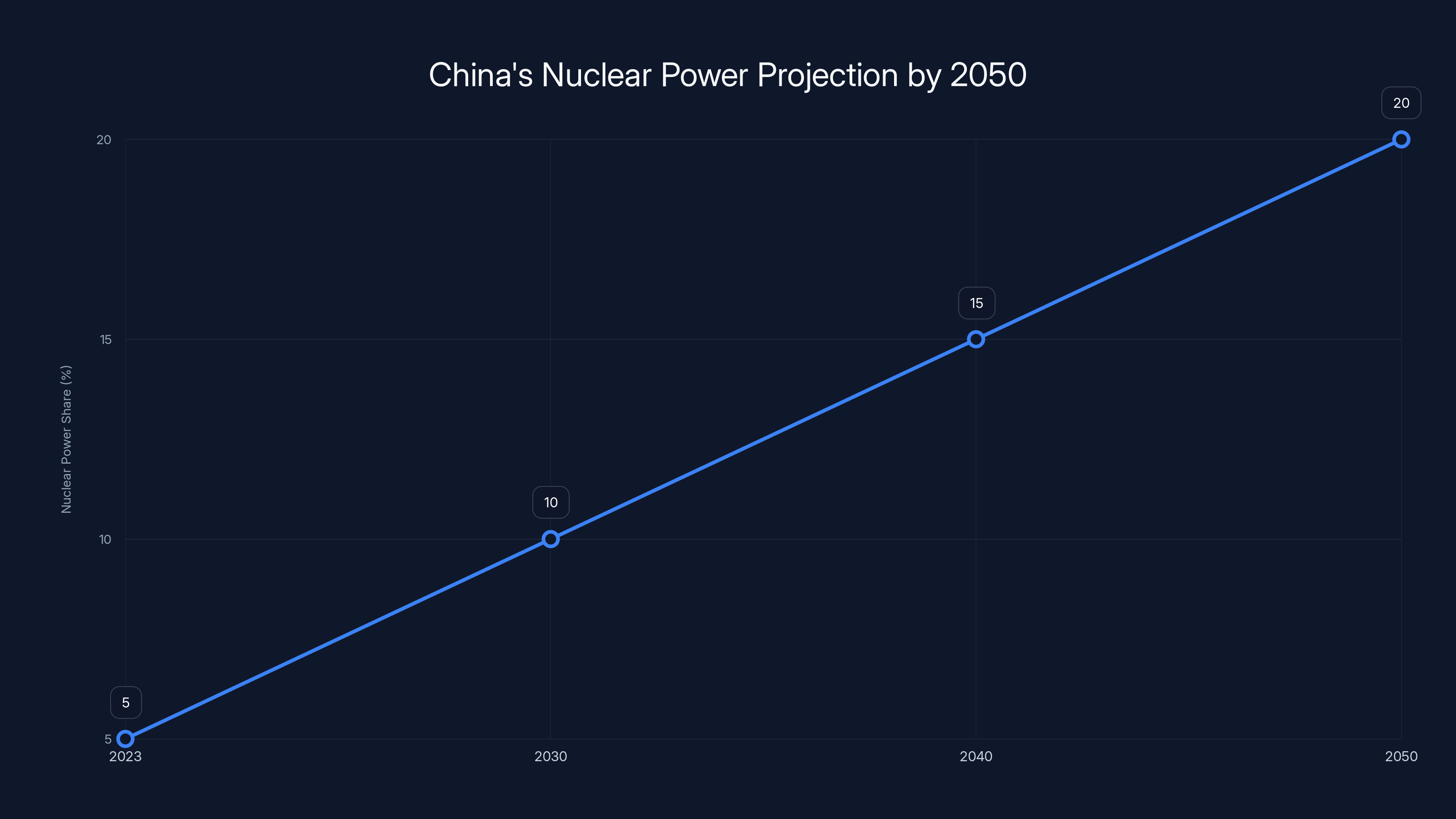

China aims to increase nuclear power's contribution to its electricity supply from 5% in 2023 to over 20% by 2050. Estimated data based on strategic goals.

Understanding Seawater Uranium: The Resource That's Already Here

Before exploring what China accomplished, it's worth understanding why seawater uranium has attracted scientific attention for half a century. The premise is simple: the ocean is massive, uranium is dissolved in it, and that uranium never runs out.

The Sheer Scale of Oceanic Uranium

The numbers are genuinely staggering. Earth's oceans contain roughly 4.5 billion tons of uranium, dispersed throughout approximately 1.3 billion cubic kilometers of saltwater. To put that in perspective, the world currently consumes about 65,000 tons of uranium annually. At that consumption rate, oceanic uranium alone could power every nuclear reactor on Earth for roughly 70,000 years. And that's assuming zero reprocessing, zero breeder reactor efficiency improvements, and zero contribution from terrestrial mining.

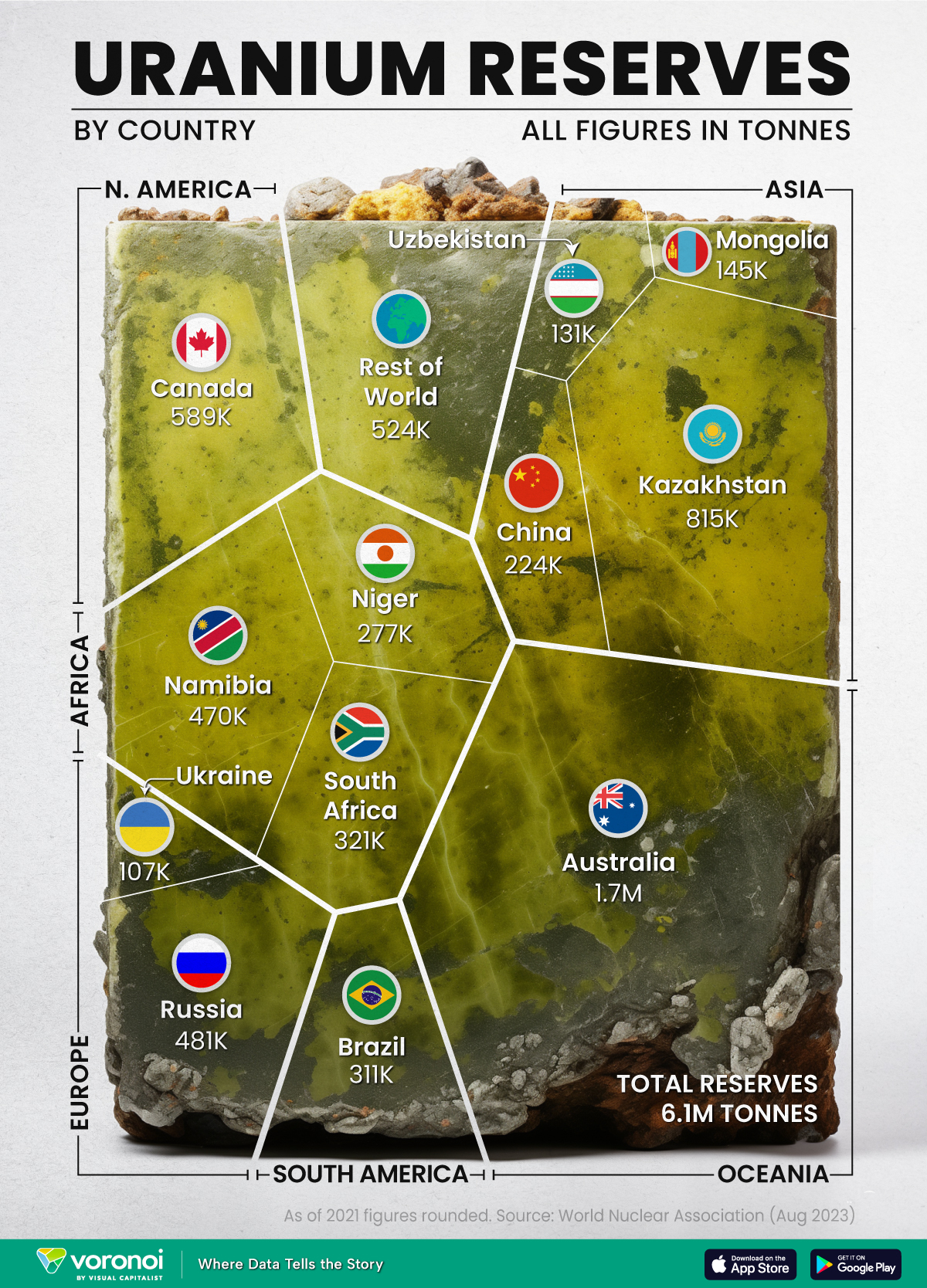

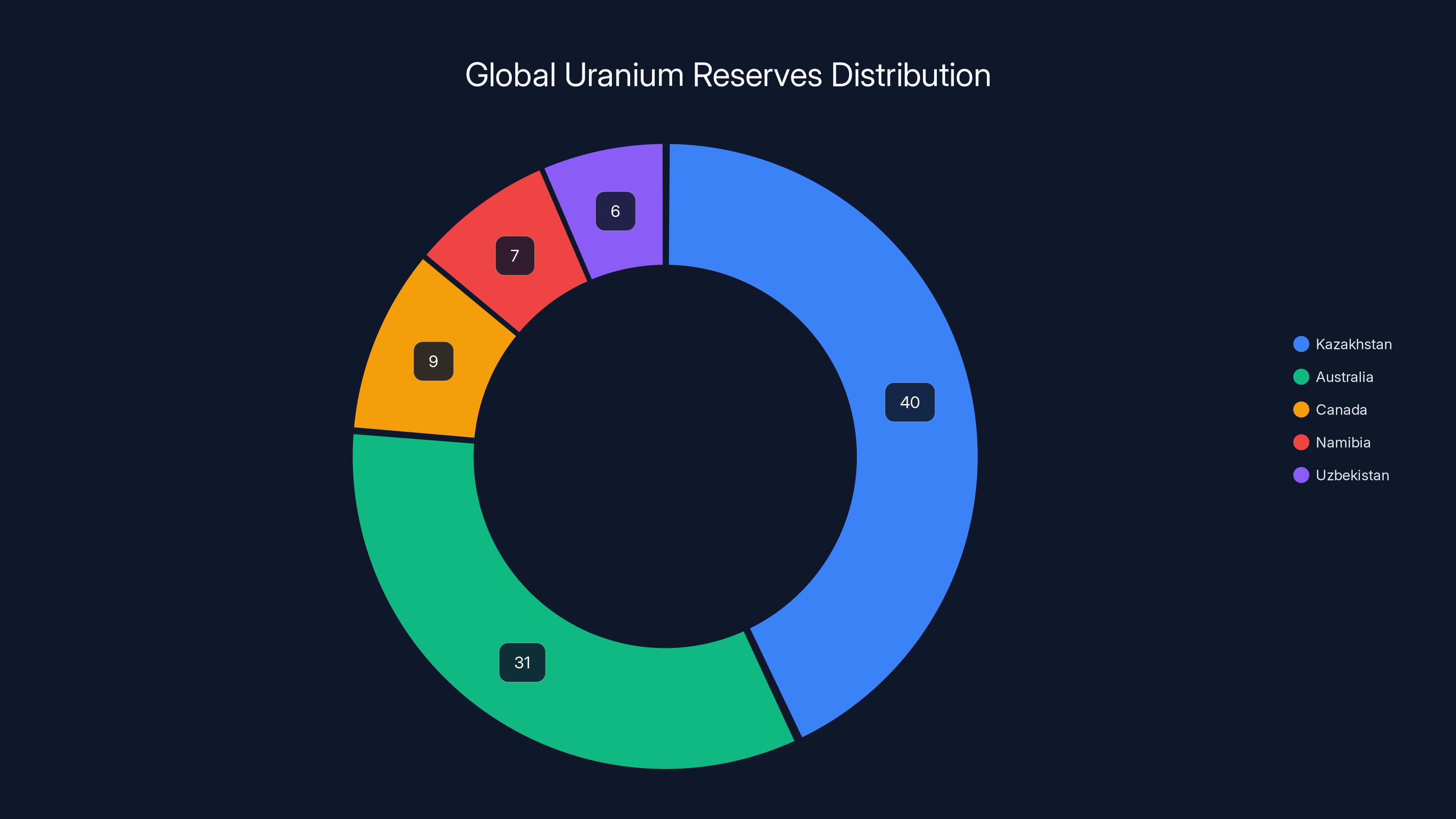

By contrast, land-based uranium reserves are exhaustible. The International Atomic Energy Agency estimates proven reserves at around 6 million tons globally, concentrated in a few geopolitically important regions. Kazakhstan alone controls approximately 40% of global uranium production. Australia holds massive deposits but faces environmental and indigenous land concerns. This geographic concentration creates supply chain fragility.

Seawater uranium offers something radically different: ubiquity. Every ocean touches multiple nations. Extraction technology could theoretically be deployed anywhere with coastal access. The resource renews itself continuously through natural geological processes, making it renewable in the truest sense.

Why Extraction Has Remained Theoretical

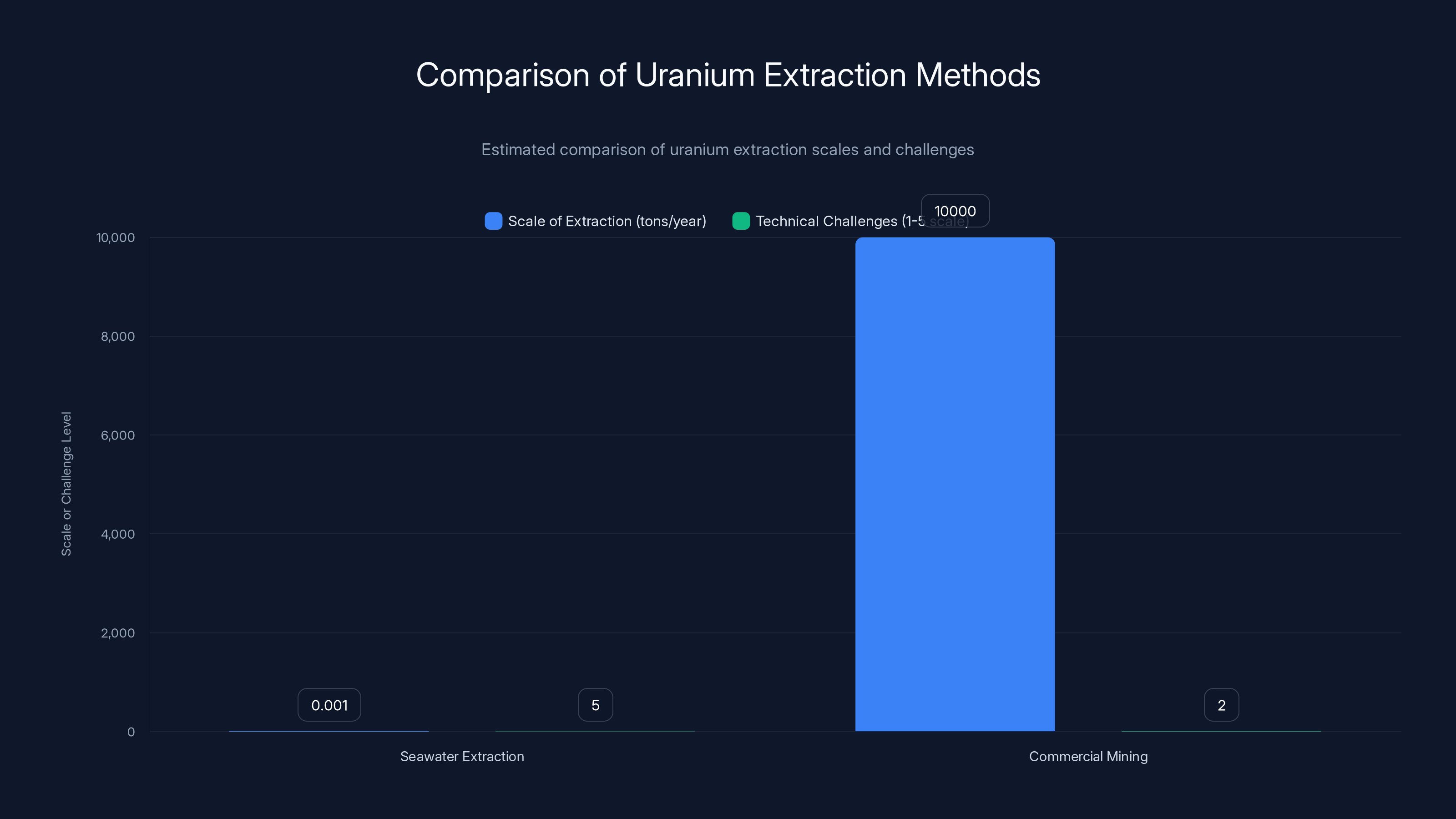

If seawater uranium is so abundant, why hasn't it been commercially harvested for decades? The answer lies in a brutal economic reality: seawater uranium concentration is nearly unmeasurable. At 0.003 parts per million, you'd need to process roughly 33 million tons of seawater to extract just one ton of uranium.

This creates a fundamental problem: the energy cost of processing that much seawater might exceed the energy value of the uranium itself. When nuclear power's advantage over fossil fuels depends partly on favorable energy return on investment (EROI), a uranium source with negative or marginal EROI becomes counterproductive. It's like developing a solar panel that requires more electricity to manufacture than it will ever generate.

There's also the corrosion problem. Ocean water is chemically aggressive. Materials that selectively absorb uranium must survive months or years of saltwater exposure while maintaining their adsorption capacity. Then they must be recovered, processed chemically to extract uranium, and redeployed. Each cycle introduces efficiency losses and maintenance costs.

How Seawater Uranium Concentration Compares

To understand why seawater uranium extraction is so difficult, compare its concentration to other resources we routinely extract from water:

Conventional Uranium Ore (Land Mining): 0.1% to 20% uranium content. Ore is mechanically separated, then chemically processed. This is economically viable because uranium density is high.

Seawater Uranium: 0.000003% (or 0.003ppm). This is roughly 30,000 to 70,000 times more dilute than terrestrial ore.

Seawater Salt (Na Cl): 3.5% by weight. Common industrial extraction processes rely on simple evaporation because salt concentration is so high.

Lithium in Seawater: 0.0017ppm. Similar dilution problem, which is why most lithium comes from terrestrial sources and salt lakes.

The comparison reveals why seawater uranium extraction requires fundamentally different technology than conventional mining. You can't simply pump seawater and separate solids. You need selective adsorption materials that grab uranium atoms while ignoring the 99.99999% of other dissolved minerals.

Seawater uranium extraction is currently at a demonstration scale (1 kg/year) compared to commercial mining (10,000 tons/year). Technical challenges for seawater extraction are significantly higher, requiring breakthroughs in materials and processes. Estimated data.

China's Kilogram-Scale Achievement: What Actually Happened

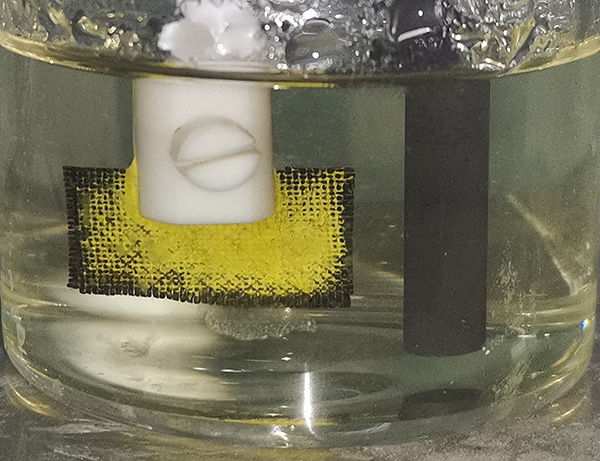

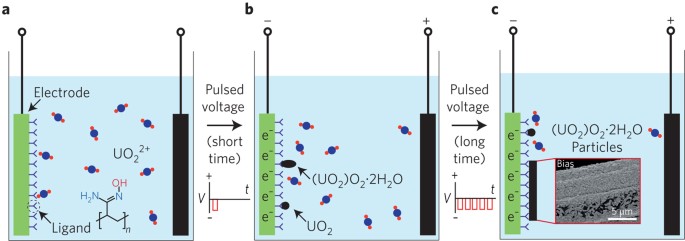

In 2024, Chinese scientists announced a concrete milestone: extraction of 1,000 grams (one kilogram) of uranium from seawater under real marine conditions. The test was conducted using a dedicated offshore platform deployed in the South China Sea, one of the world's busiest shipping lanes and most chemically complex marine environments.

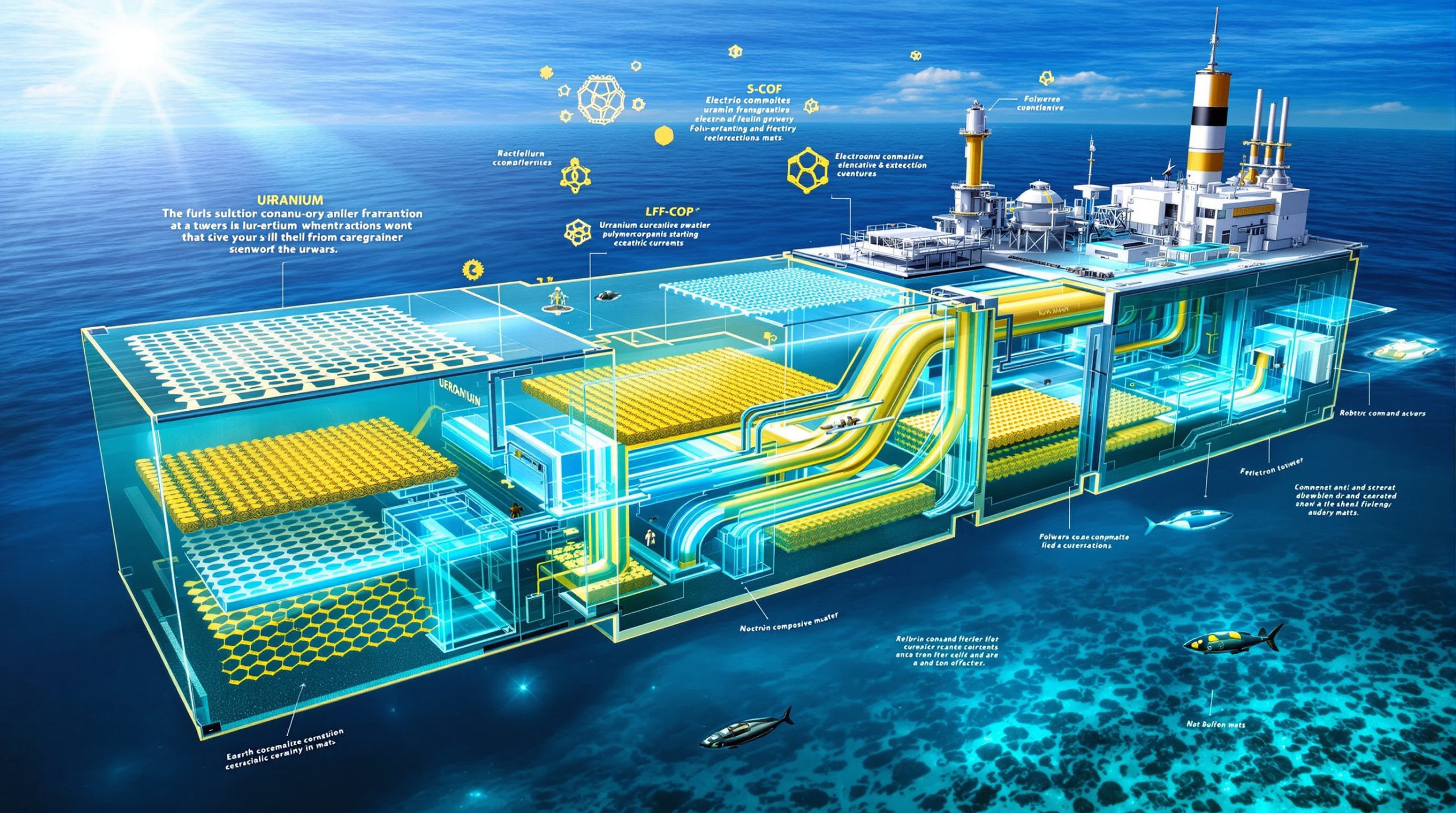

The Offshore Platform Deployment

China's approach was methodical. Rather than laboratory beakers or small-scale tanks, scientists deployed a full-scale marine testing platform designed to validate adsorption materials under realistic ocean conditions. This platform had to withstand saltwater corrosion, biofouling (algae and bacterial growth), strong currents, temperature fluctuations, and the mechanical stress of waves and weather.

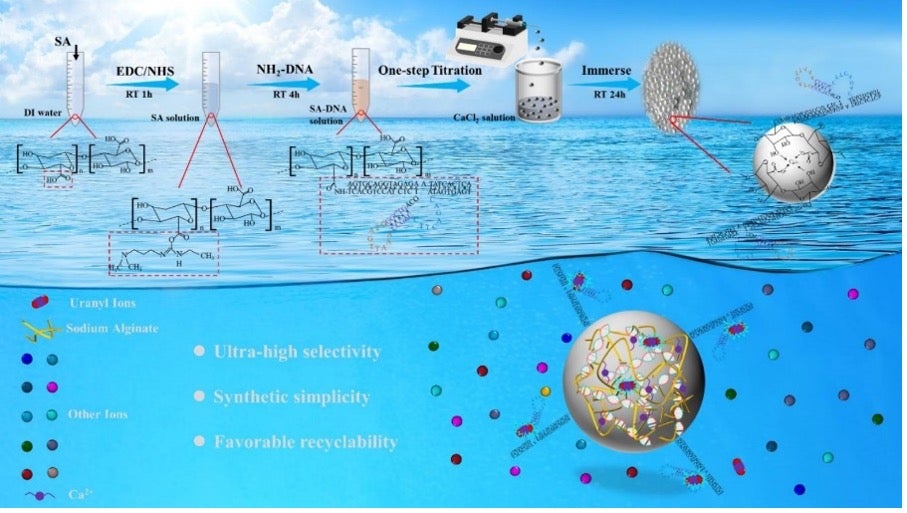

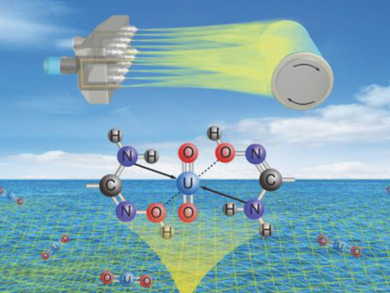

The platform used large sheets of specially engineered adsorption materials (likely polymer-based or titanium-based compounds) suspended in the water. These materials selectively bind uranium atoms while letting other dissolved minerals pass through. After weeks or months of deployment, the materials were recovered, brought to a laboratory, and processed chemically to extract the accumulated uranium.

The fact that this was conducted in the South China Sea rather than a controlled test tank is significant. The South China Sea is one of the world's most challenging marine environments, with high salinity variation (some regions are partially freshwater), intense biological activity, and significant pollution. If materials can survive and maintain functionality there, they'd work in most ocean regions.

Why One Kilogram Is Significant (And Why It Isn't)

Significant aspects of the achievement:

- Proof of Controlled Operation: It demonstrates that uranium extraction at kilogram scale can be consistently achieved under real-world conditions, not just in laboratory settings.

- Material Validation: The adsorption materials functioned as designed despite months of saltwater exposure, biofouling, and corrosive conditions.

- Process Repeatability: Scientists showed they could deploy, recover, process, and redeploy the same materials multiple times, suggesting scalability is at least theoretically possible.

- Government-Scale Commitment: This wasn't a university lab project. State-linked nuclear institutions backed this, suggesting China views seawater uranium as a genuine strategic priority.

However, the limitations are equally important:

- Energy Cost Unknown: China released no public data on how much energy was consumed to extract that kilogram. If the energy input was substantial, commercial viability remains in question.

- Efficiency Metrics Missing: No figures were provided on extraction efficiency (what percentage of available uranium was actually captured), absorption capacity per material, or processing losses.

- Cost Per Kilogram Unknown: The critical metric for commercial deployment—cost per kilogram—wasn't disclosed. Without this, the achievement's economic significance is impossible to assess.

- Proof of Concept, Not Commercial Breakthrough: The most honest interpretation is that this demonstrates controlled operation at a modest scale. Moving from kilograms to millions of kilograms annually involves engineering challenges that dwarf the lab work.

The Adsorption Materials Technology

The core of seawater uranium extraction is adsorption material science. These are engineered polymers or titanium-based compounds designed with specific molecular structures that uranium atoms preferentially bind to while ignoring sodium, chloride, magnesium, and other dominant seawater ions.

The most promising materials researched internationally include titanium oxide compounds, functionalized polymers, and composite materials combining organic and inorganic components. The goal is to maximize selectivity (bind uranium, ignore other ions) while maintaining mechanical durability and reusability across hundreds of deployment cycles.

China's system likely employed one of several approaches:

Titanium-Based Adsorbents: Titanium dioxide or titanium oxide materials functionalized with groups that bond selectively to uranium. These are durable but can be expensive to produce.

Polymeric Adsorbents: Plastic-like materials with chemical groups attached that grab uranium atoms. Cheaper to produce, potentially scalable, but may degrade faster in seawater.

Composite Materials: Combinations of titanium and polymer that aim to balance selectivity, durability, and cost.

The specific material China used hasn't been publicly identified, which is typical for nuclear technology given strategic and proliferation sensitivity.

The Energy Economics: The Math That Matters Most

Here's the hard truth that separates hype from reality: extracting uranium from seawater only makes sense if the energy content of the extracted uranium exceeds the energy required to extract it. Otherwise, you're running an energy-losing operation.

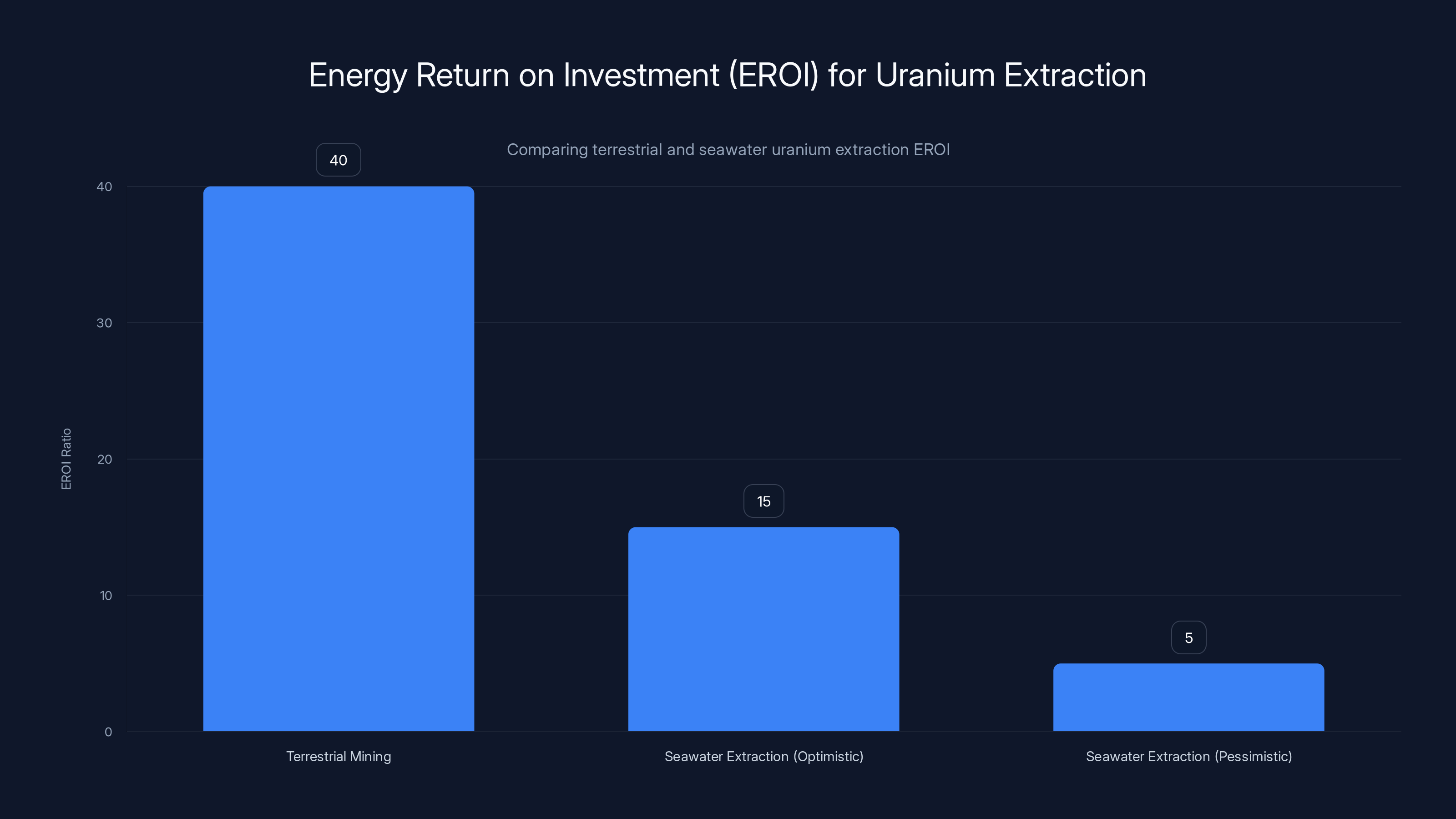

Calculating Energy Return on Investment (EROI)

Energy return on investment is defined as:

For terrestrial uranium mining, EROI typically ranges from 30:1 to 50:1, meaning you get 30 to 50 units of energy output for every unit of energy input. This high ratio is why nuclear power can compete with fossil fuels despite initial processing costs.

For seawater uranium extraction, EROI is the critical unknown. The energy demands include:

- Pumping and Processing Seawater: Moving millions of tons of water through the extraction system requires substantial energy, even if the system is passive (relying on ocean currents).

- Material Deployment and Recovery: Manufacturing, shipping, deploying, and recovering adsorbent materials all consume energy.

- Chemical Processing: Extracting uranium from saturated adsorbent materials requires chemical reagents and often heating, both energy-intensive.

- Concentration and Enrichment: Raw seawater uranium still needs to be concentrated and potentially enriched for reactor use.

International research suggests that seawater uranium extraction could achieve EROI between 5:1 and 15:1 under optimistic assumptions about material efficiency and processing. This is significantly lower than terrestrial mining but potentially acceptable if uranium scarcity becomes severe enough.

However, this is theoretical. China hasn't published EROI calculations for its pilot system. Until those numbers are available, the commercial viability remains speculative.

Cost Projections and Commercial Feasibility

International studies suggest that seawater uranium could become cost-competitive with terrestrial mining if extraction costs can be reduced to approximately

China hasn't disclosed actual costs for its pilot extraction, but industry analysts estimate that at current material costs and processing efficiency, seawater uranium would run

Bridging this gap requires breakthroughs in:

- Adsorbent Material Cost: Developing cheaper, more efficient materials.

- Process Automation: Reducing labor and operational costs through automation.

- Scale Economics: Moving from kilograms to millions of kilograms annually, which typically reduces per-unit costs.

- Energy Efficiency: Minimizing energy expenditure through passive systems (using ocean currents rather than pumps) or renewable energy integration.

Some researchers have proposed coupling seawater uranium extraction with offshore wind or tidal energy, so the electricity powering the extraction process is zero-carbon. This could improve the overall sustainability equation even if costs remain higher than terrestrial mining.

Kazakhstan and Australia dominate global terrestrial uranium reserves, controlling 71% combined. This concentration highlights geopolitical vulnerabilities in uranium supply.

Comparing Seawater Uranium to Terrestrial Reserves

Understanding seawater uranium's potential requires honest comparison to conventional mining. Let's examine the key differentiators:

Geographic Distribution and Geopolitics

Terrestrial Uranium Reserves are highly concentrated. Kazakhstan controls 40% of global production. Australia holds 31% of reserves. Namibia, Canada, and Uzbekistan round out the top five. This concentration creates geopolitical vulnerability: supply disruptions in a single region can ripple globally.

Seawater Uranium exists in every ocean, accessible to any nation with coastline and technology. This geographic distribution is theoretically democratizing—smaller nations wouldn't depend on uranium imports from Kazakhstan or Australia. In practice, only wealthy nations can afford the capital investment for extraction platforms.

Renewal and Depletion

Terrestrial Uranium is depleted as it's mined. Known reserves will eventually run out. At current consumption rates, proven reserves last roughly 90 years. New discoveries can extend this, but discovery rates have declined as easy-to-mine deposits become scarce.

Seawater Uranium continuously renews through geological processes. As uranium is extracted, river runoff and continental weathering replenish the oceanic supply. This is why it's theoretically infinite—it's the only renewable uranium source.

Environmental Cost Comparison

Terrestrial Uranium Mining involves open-pit or underground mining, mill tailings, and environmental remediation. While modern uranium mining is increasingly regulated, historical mines left lasting environmental damage. In Kazakhstan, former Soviet-era uranium mining created radioactive contamination affecting groundwater.

Seawater Uranium Extraction avoids terrestrial land disturbance but introduces new concerns:

- Adsorbent materials deployment could affect marine ecosystems if materials degrade and release chemicals.

- Large-scale extraction platforms might create navigation hazards or fishing disruption.

- Energy requirements could drive demand for fossil fuels or renewables, with accompanying environmental costs.

The environmental calculus isn't obviously better for seawater extraction, though it potentially avoids catastrophic land contamination.

Extraction Speed and Scalability

Terrestrial Uranium Mining can ramp up relatively quickly. A new mine takes 5-10 years from discovery to production but, once operational, can scale up within years.

Seawater Uranium Extraction is slower to scale. Moving from kilogram-scale lab demonstrations to thousands of tons annually requires developing supply chains for adsorption materials, training operators, building processing facilities, and validating reliability. Current estimates suggest 15-25 years from successful pilot to meaningful commercial production.

Extraction Cost Comparison

Here's a table showing the economic gap that still needs closure:

| Aspect | Terrestrial Uranium | Seawater Uranium (Projected) |

|---|---|---|

| Current Cost/kg | ||

| Concentration | 0.1% to 20% | 0.000003% |

| Processing Complexity | High (mining, milling) | Extremely high (selective adsorption) |

| Geographic Concentration | 5 nations control 80% | Every nation with coast |

| Resource Finiteness | Depletable in ~90 years | Renewable/infinite |

| Time to Commercial Scale | 5-10 years | 15-25 years |

| Environmental Footprint | Land disruption, tailings | Ocean deployment, material degradation |

The table reveals the central trade-off: seawater uranium is geographically abundant and theoretically infinite, but economically and operationally far more challenging to extract than terrestrial sources.

China's 2050 Vision: "Unlimited Battery Life" and Nuclear Supremacy

China's seawater uranium project isn't just about solving a technical puzzle. It's embedded in a massive, decades-long strategic vision about energy independence and nuclear power's role in civilization's future.

Understanding China's Nuclear Ambitions

China currently operates 54 nuclear reactors and has roughly 20 more under construction, the largest nuclear expansion program globally. By 2050, China projects nuclear power could supply 20% or more of the nation's electricity, up from the current 5%. This requires an enormous increase in uranium supply.

China imports roughly 90% of its uranium from Kazakhstan, Australia, and Canada—all nations outside its direct control. This dependency mirrors historical oil dependency and creates strategic vulnerability. If international tensions disrupt uranium supply chains, China's nuclear fleet could be crippled.

Seawater uranium extraction solves this problem elegantly: by developing indigenous, oceanic uranium supplies, China becomes energy-independent for nuclear fuel. This isn't just a technological goal; it's existential for China's vision of sustained economic and technological dominance.

The "unlimited battery life" framing is strategic marketing. Batteries don't contain uranium. But the phrase captures the idea of technology powered indefinitely without resource scarcity constraints. In China's framing, seawater uranium is the ultimate energy insurance policy.

The 2050 Timeline: Realistic or Aspirational?

China's stated goal to make seawater uranium commercially viable by 2050 is ambitious but potentially realistic given sufficient investment. Here's a rough timeline:

2024-2030 (Pilot Phase): Expand kilogram-scale demonstrations to hundreds of kilograms annually. Validate material durability, cost reduction pathways, and process efficiency. Publish data on EROI and economics.

2030-2040 (Demonstration Phase): Scale to ton quantities annually through multiple offshore platforms. Prove cost reduction targets (targeting

2040-2050 (Commercial Phase): Deploy industrial-scale platforms capable of extracting thousands of tons annually. Achieve cost parity with terrestrial mining or demonstrate sufficient strategic value to justify premium pricing.

This timeline assumes consistent investment, no major setbacks, and incremental material science improvements. It's achievable but demands sustained commitment through political and economic cycles.

For comparison, China's other energy megaprojects have generally met or exceeded timelines: the Three Gorges Dam (1993-2012), the South-North Water Transfer Project (1999-2014), and the Belt and Road Initiative (2013-ongoing). This suggests institutional capacity to execute long-term infrastructure projects.

Strategic Benefits Beyond Energy

Seawater uranium extraction offers China strategic benefits beyond simply securing fuel:

- Technology Export: If China masters this technology, it can license or sell extraction systems globally, creating leverage with energy-dependent nations.

- Technological Prestige: Leading the world in seawater uranium extraction signals technological sophistication and scientific capability.

- Nuclear Supply Chain Control: By securing indigenous uranium, China can negotiate better terms with other nations and potentially expand nuclear fuel exports.

- Green Energy Leadership: Pairing seawater uranium with renewables positions China as a leader in clean energy transition.

These benefits extend far beyond simple fuel supply and explain why China is willing to invest in a technology whose current economics don't yet justify commercial deployment.

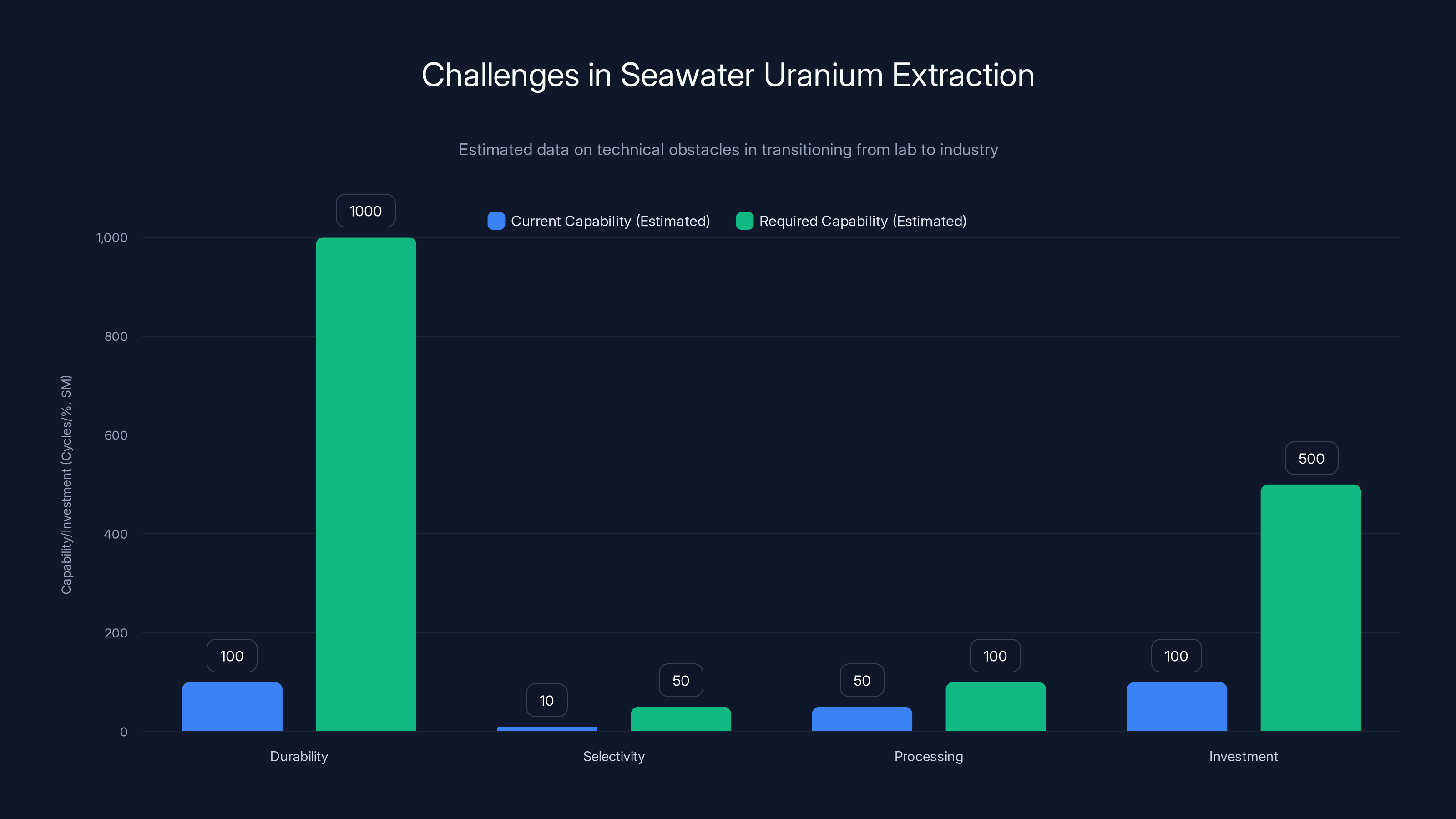

The transition from lab to industry for seawater uranium extraction requires significant improvements in material durability, selectivity, processing efficiency, and investment. Estimated data shows a need for 10x durability, 5x selectivity, and 5x investment increase.

International Efforts and Competitive Landscape

China isn't alone in pursuing seawater uranium extraction. Multiple nations and institutions have invested in this technology, with varying approaches and commitments.

The United States and DOE Initiatives

The U. S. Department of Energy has funded seawater uranium research for decades, particularly through national laboratories at Oak Ridge and Lawrence Livermore. American researchers have achieved similar kilogram-scale extractions and are working on cost reduction.

Unlike China's centralized approach, U. S. efforts are distributed across multiple institutions and have received less consistent, long-term funding. This has slowed progress but allowed exploration of diverse technical approaches.

American research emphasizes adsorbent material science and has produced some of the most selective uranium-binding polymers. However, the U. S. hasn't deployed large-scale offshore platforms, partly due to higher labor costs and partly due to philosophical differences about nuclear power's role in energy strategy.

European Research Programs

France, Japan, and India have all pursued seawater uranium research programs. France, as a nuclear-heavy nation (70% of electricity from nuclear), has strategic interest in long-term fuel security. Japanese researchers have developed some of the most durable titanium-based adsorbents.

However, European and Japanese programs receive less funding than China's equivalent initiatives and tend to focus on basic material science rather than demonstration-scale deployments.

The Competitive Advantage China Appears to Have

China's advantages in seawater uranium extraction include:

- Long-Term Funding Commitment: State-directed capital flowing consistently toward pilot and demonstration phases.

- Labor Cost Advantages: Chinese labor for manufacturing and deployment is significantly cheaper than Western alternatives.

- Regulatory Streamlining: China can deploy offshore platforms with fewer environmental impact assessments than democracies.

- Manufacturing Scale: China dominates global adsorption material production, giving it cost advantages in adsorbent development.

- Proximity to Resources: China's proximity to high-uranium-concentration ocean zones (North Pacific) provides testing advantages.

These advantages don't guarantee China will reach commercial-scale seawater uranium extraction first, but they substantially improve the odds.

The Technical Obstacles Still Standing Between Lab and Industry

Despite China's kilogram-scale achievement, vast technical challenges remain before seawater uranium extraction becomes an industrial reality.

Adsorbent Material Durability and Reusability

Current adsorption materials can be used for dozens to hundreds of cycles before degradation becomes problematic. Commercial operation might require thousands of cycles annually. Materials must survive:

- Saltwater corrosion over months or years of deployment

- Biofouling from algae, barnacles, and bacterial growth

- Physical degradation from waves, currents, and temperature swings

- Chemical stress from repeated uranium extraction and regeneration cycles

Improving durability to 1,000+ cycles without significant performance loss is possible through material innovation but requires research investment of hundreds of millions of dollars and 5-10 years of development.

Selective Uranium Extraction from Complex Seawater Composition

Seawater contains roughly 92 chemical elements dissolved in it, with sodium and chloride at massive concentrations. Creating materials that selectively grab uranium (0.000003% concentration) while ignoring sodium (1%) and chloride (2%) is extraordinarily difficult.

This requires molecular engineering at the atomic scale, testing millions of material combinations, and validating selectivity in real seawater (not pure laboratory conditions). The chemistry is mature enough to work but immature enough that improvements of 10-50% in selectivity are realistic with research investment.

Processing and Concentration

Once uranium-saturated adsorbent material is recovered from the ocean, extracting the uranium requires:

- Elution: Washing the material with chemical solutions to release uranium atoms

- Precipitation: Converting dissolved uranium to solid form

- Purification: Removing co-extracted ions and contaminants

- Concentration: Combining uranium from many adsorbent batches

- Stabilization: Converting uranium to a stable chemical form suitable for storage or further processing

Each step introduces efficiency losses. Current processes achieve maybe 80-90% recovery of uranium from saturated materials. Improving to 95%+ requires process innovation.

Scaling from Kilograms to Tons to Thousands of Tons

This is often the most underestimated challenge. Moving from a single offshore platform extracting kilograms to 100 platforms extracting thousands of tons requires:

- Supply Chain Development: Manufacturing adsorbent materials at a scale 10,000 times larger than today

- Platform Manufacturing: Building dozens of specialized offshore platforms, each costing tens to hundreds of millions

- Operator Training: Creating an international workforce skilled in deployment, recovery, and processing

- Process Standardization: Developing detailed procedures that work across different ocean conditions and geographic regions

- Quality Assurance: Ensuring consistent uranium quality across hundreds of processing facilities

Historically, scaling from lab demonstrations to industrial production takes 15-25 years and costs billions of dollars. Seawater uranium extraction won't escape this reality.

Oceanic uranium vastly exceeds land-based reserves, offering a renewable and ubiquitous resource for nuclear energy. Estimated data highlights the potential for long-term energy sustainability.

Environmental and Social Considerations

Seawater uranium extraction comes with environmental and social responsibilities that extend beyond the technology itself.

Marine Ecosystem Impact

Large-scale deployment of adsorbent materials in the ocean could affect marine life:

Biofouling Effects: Organisms growing on adsorbent materials might concentrate uranium and potentially bioaccumulate radioactive isotopes. While marine uranium concentrations are extremely low, any concentration represents a potential ecological risk requiring careful study.

Disruption of Fishing and Navigation: Hundreds of offshore platforms would occupy productive fishing areas and create navigation hazards for vessels. Fisheries would need to be rerouted, potentially reducing catches.

Adsorbent Material Degradation: If adsorbent materials degrade in the ocean and release synthetic polymers, this could contribute to marine plastic pollution and ecosystem stress.

Uranium Extraction Effects: Removing dissolved uranium from seawater at scale might affect marine chemistry and nutrient cycling, though the effect is likely negligible given uranium's low concentration.

These impacts require environmental impact assessments and mitigation strategies before large-scale deployment. International maritime law, overseen by the International Maritime Organization, would likely need to develop new regulations governing uranium extraction in international waters.

Social and Economic Disruption

Seawater uranium extraction would reshape maritime economics:

- Fishing Conflicts: Fisheries might face access restrictions or reduced productivity near extraction platforms.

- Employment Shifts: New jobs in extraction and processing would be created, but fishing and related industries might decline.

- Inequality: Wealthy nations with capital for platforms would benefit most; developing nations might see fishing livelihoods threatened.

- Territorial Disputes: Questions about who owns uranium in international waters could reignite maritime boundary disputes.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) governs ocean resource extraction but doesn't specifically address uranium. Developing international frameworks for fair, equitable uranium extraction will be necessary.

Regulatory Landscape

No nation currently has comprehensive regulations for seawater uranium extraction. Developing these regulations requires international cooperation and will likely happen only after initial commercial deployments succeed. This creates regulatory uncertainty for investors and developers.

Economic Models and Cost Reduction Pathways

Understanding whether seawater uranium extraction becomes economically viable requires examining realistic cost reduction pathways.

Material Cost Reduction Potential

Adsorption materials currently cost

- Simplified Manufacturing Processes: Current materials use complex synthesis requiring specialized equipment. Developing simpler processes could reduce costs 30-50%.

- Economies of Scale: Manufacturing at thousands of tons annually (versus current hundreds of kilograms) would reduce per-unit costs 20-40%.

- Raw Material Substitution: Using cheaper precursor chemicals or bio-based polymers instead of expensive titanium compounds could save 15-30%.

Combined, these pathways could reduce material costs to

Energy Cost Optimization

Currently, energy costs dominate seawater uranium extraction economics. Energy demands must drop from current levels (roughly 50-100 MWh per kilogram of extracted uranium, estimated) to 5-10 MWh per kilogram.

Pathways to energy optimization include:

- Passive Deployment Systems: Designing adsorbent materials that absorb uranium through ocean current contact without active pumping. This could reduce energy demand 60-70%.

- Renewable Energy Integration: Coupling extraction with offshore wind or tidal energy, so energy costs are marginal and carbon-free.

- Process Automation: Automating recovery, elution, and processing steps to reduce labor-intensive manual work and associated energy.

Implementing these optimization together could reduce effective energy costs 70-80%.

Hybrid Economic Models

Some researchers propose hybrid models that make seawater uranium extraction economically viable without achieving full cost parity with terrestrial mining:

- Byproduct Extraction: Seawater contains valuable minerals (lithium, molybdenum, vanadium). Extracting uranium as a primary product while harvesting valuable byproducts could generate revenue streams that justify higher uranium costs.

- Government Subsidies: Nations viewing seawater uranium as strategic might subsidize extraction costs, similar to how most governments support solar or wind energy.

- Carbon Credit Integration: If extraction uses renewable energy, carbon credits could offset costs by 100 per ton of extracted uranium.

These models suggest that even if pure extraction costs remain above terrestrial mining, seawater uranium could become economically viable through creative business models.

Terrestrial uranium mining has a high EROI of 30:1 to 50:1, making it energy-efficient. In contrast, seawater extraction's EROI ranges from 5:1 to 15:1, indicating lower energy efficiency but potential viability if uranium scarcity increases. Estimated data based on international research.

Comparison With Alternative Nuclear Fuel Sources

Understanding seawater uranium's potential requires context about alternatives being explored simultaneously.

Terrestrial Uranium Improvement and Extended Reserves

Terrestrial uranium reserves could be extended significantly through:

Advanced Mining: Developing mining methods that access lower-grade ore currently considered uneconomical. This could extend terrestrial reserves another 50-100 years.

Uranium Recycling: Extracting uranium from spent nuclear fuel extends reserves by 30-50% by recovering uranium that didn't fission in reactors.

Breeder Reactors: Using fast neutron reactors that convert uranium-238 (abundant) into plutonium fuel, extending uranium resources 60-100 times. France operated a large breeder reactor (Phénix) for decades; Russia still operates them.

Thorium: Using thorium as an alternative fuel in special reactor designs. Thorium is 3-4 times more abundant than uranium on land and ocean. If thorium technology matures, it becomes a competitor to seawater uranium.

These alternatives suggest that seawater uranium extraction isn't the only path to long-term nuclear fuel security. However, multiple pathways being pursued simultaneously increases the likelihood that at least one succeeds.

Fusion Energy as Long-Term Alternative

Fusion energy, if commercialized, would fundamentally alter nuclear fuel dynamics. Fusion reactors would use deuterium (extracted from seawater) and lithium (abundant on land), making uranium-based fuels obsolete.

However, commercial fusion remains 20-30 years away at best, possibly much longer. Seawater uranium extraction is arguably a bridge technology for the period before fusion achieves commercial viability.

Renewable Energy Displacement

Rapidly improving solar and wind technology, paired with energy storage, might eventually reduce nuclear power's role in global energy. If renewables become cheaper and more reliable than nuclear (even with seawater uranium fuel), demand for uranium drops regardless of supply.

This isn't a near-term risk but represents long-term uncertainty about seawater uranium's relevance.

Case Studies: Where Seawater Uranium Research Stands Globally

Examining specific research programs reveals the current state of seawater uranium technology.

Japan's Advanced Materials Program

Japan has invested heavily in adsorbent material science, producing some of the world's most selective uranium-binding compounds. Japanese researchers developed titanium-based materials capable of extracting uranium at nearly 99% efficiency in laboratory conditions.

However, Japan hasn't deployed large-scale offshore platforms, partly due to high labor costs and partly because Japan imports uranium cheaply from Australia. Without strategic urgency, funding has been modest compared to China's scale of investment.

U. S. National Laboratory Efforts

Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have conducted steady-state research into seawater uranium, producing world-class science. American researchers achieved kilogram-scale extraction in controlled conditions and published extensive research on adsorbent materials, selectivity, and cost projections.

However, U. S. efforts lack the long-term institutional commitment behind China's program. American uranium imports from Canada and Kazakhstan are stable, reducing political pressure to develop indigenous supplies.

India's Emerging Interest

India, planning massive nuclear expansion and dependent on uranium imports, has recently increased research into seawater uranium extraction. India's advantage is extensive coastline and lower labor costs. However, India's nuclear industry faces international restrictions on fuel supply, making seawater extraction strategically important.

Indian research remains early-stage but is accelerating as energy demand grows.

Future Scenarios: Optimistic, Realistic, and Pessimistic Paths

What could seawater uranium extraction look like by 2050? Three scenarios illustrate the range of possibilities.

Optimistic Scenario: Commercial Maturity by 2045

Assumptions: Continuous funding, incremental breakthroughs in materials and processes, international collaboration.

Outcomes by 2050:

- 15-20 large-scale offshore extraction facilities operating globally, extracting 10,000-15,000 tons of uranium annually

- Cost reduction to 200 per kilogram, achieving cost parity with terrestrial mining

- Seawater uranium supplies 30-40% of global uranium demand

- China, coupled with Japan and the U. S., dominates extraction technology and platform manufacturing

- Multiple nations build their own platforms, reducing China's monopoly

- No major environmental incidents; marine ecosystem impacts prove manageable

Implications: Nuclear power becomes clearly sustainable for centuries, reducing urgency around fusion energy development. Global energy security improves. China achieves energy independence for nuclear fuel.

Realistic Scenario: Demonstration Phase Extending to 2040s

Assumptions: Funding follows typical patterns (bursts and plateaus), some technical challenges prove harder than expected, cost reductions trail optimistic projections.

Outcomes by 2050:

- 3-5 large-scale platforms operational, extracting 1,000-3,000 tons annually by 2050

- Cost remains at 500 per kilogram, above terrestrial mining but acceptable strategically

- Seawater uranium supplies 10-15% of global uranium demand

- Technology remains concentrated in China, with limited international deployment

- Environmental impacts require ongoing monitoring and mitigation

- Research continues into next-generation materials with potential for further cost reduction

Implications: Seawater uranium becomes a supplementary supply source, not a primary one. Terrestrial mining remains economically dominant. However, seawater extraction provides strategic security for nations with coastline access.

Pessimistic Scenario: Cost Reduction Stalls Before 2040

Assumptions: Material science improvements hit diminishing returns, energy costs don't decline as projected, scaling proves more expensive than anticipated.

Outcomes by 2050:

- Pilot programs continue, but no large-scale commercial deployment

- Cost remains at 1,000+ per kilogram, making seawater uranium uncompetitive against terrestrial mining

- Research shifts toward breeder reactors and thorium as alternatives

- Fusion energy deployment begins small-scale commercial operation, reducing future uranium demand

- Seawater uranium remains a research area but not a commercial energy source

Implications: Chinese strategic goal for "unlimited battery life" doesn't materialize through seawater uranium. Instead, relies on advanced reactors, international uranium diplomacy, and eventual fusion transition. Billions in research investment produce scientific knowledge but no commercial technology.

The realistic scenario is most likely, with elements of both optimistic and pessimistic paths occurring simultaneously.

Policy and Regulatory Implications

Large-scale seawater uranium extraction would require new policies and regulations across multiple domains.

International Maritime Law Needs Updating

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) governs ocean resource extraction, but uranium extraction wasn't contemplated when UNCLOS was drafted in 1982. New protocols would need to address:

- Who owns uranium in international waters (beyond 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zones)?

- How much extraction can occur before environmental impact requires mitigation?

- What compensation should fishing nations receive if extraction disrupts fisheries?

- How should technology transfer be managed to prevent monopolies?

Developing these frameworks through international consensus is slow but necessary before industrial-scale extraction begins.

Nuclear Regulatory Harmonization

Currently, each nation's nuclear regulator (the NRC in the U. S., the ONR in the UK, the CNSC in Canada) has different standards for uranium quality, enrichment measurement, and handling. Seawater uranium extraction would produce uranium in varied forms, requiring harmonized international standards for quality assurance.

Environmental Impact Assessment Standards

New standards for assessing long-term environmental impacts of large-scale ocean resource extraction are needed. This includes monitoring protocols, trigger points for operational modification or cessation, and liability frameworks if damage occurs.

Supply Chain Security Regulations

Nations dependent on seawater uranium extraction would need regulatory frameworks ensuring continuous operation and supply reliability. This might include strategic reserves, redundancy requirements, and international agreements guaranteeing access to extraction technology.

Strategic Implications for Global Energy Security

Seawater uranium extraction, if successful, would reshape global energy geopolitics in profound ways.

Shifting Power Dynamics in Nuclear Fuel

Currently, Kazakhstan controls 40% of uranium production, giving it disproportionate global influence. If seawater extraction becomes viable, power shifts from land-rich nations to ocean-bordering nations. This represents a geopolitical realignment.

China, with extensive coastline and advanced technology, positions itself as a nuclear fuel superpower. This enhances China's strategic autonomy and potentially gives it influence over nations lacking coastal uranium resources.

Energy Independence and Strategic Autonomy

Nations currently dependent on uranium imports could achieve energy independence through indigenous seawater extraction. This reduces foreign policy constraints and enhances strategic flexibility.

Small, island nations with limited terrestrial resources but extensive maritime zones could become energy exporters. This represents a dramatic shift from current energy geopolitics.

Climate Implications

If seawater uranium extends nuclear power's viability, nuclear energy's role in decarbonization increases. Nuclear power produces zero operational carbon emissions, and if uranium supply is unlimited, nuclear could supply 40-60% of global electricity by 2050 rather than the current projected 15-20%.

This accelerates climate change mitigation, though it also increases reliance on nuclear technology, creating different risks (proliferation, waste, accidents).

Implications for Fossil Fuel Decline

Seawater uranium extraction wouldn't directly affect fossil fuel demand, but it signals a long-term shift away from fossil fuels. If investors believe nuclear will dominate future energy, investment in oil, gas, and coal infrastructure declines more rapidly.

This creates stranded assets and accelerates the energy transition's economic disruption, particularly for nations dependent on fossil fuel exports.

Conclusion: Seawater Uranium as Strategic Bet, Not Solved Problem

China's successful extraction of one kilogram of uranium from seawater represents meaningful technological progress, but it's crucial to understand what this achievement actually signifies: proof of controlled operation at a modest scale, not a solved commercial problem.

The 4.5 billion tons of uranium dissolved in Earth's oceans represent an almost incomprehensible energy resource, theoretically sufficient to power civilization for hundreds of millennia. But abundance and accessibility are entirely different things. The ocean's uranium is so diffuse, so chemically embedded within saltwater, that extracting it profitably remains one of the hardest technical problems in energy.

China's 2050 vision of "unlimited battery life"—framed as decades of research toward energy independence through oceanic uranium—is simultaneously audacious and realistic. It's audacious because succeeding requires solving material science, process engineering, and economic challenges of enormous scale. It's realistic because China has demonstrated institutional capacity to execute megaprojects, resources to fund research for 25+ years, and strategic motivation to solve energy independence problems.

But success isn't guaranteed. The energy return on investment might prove marginal. Cost reduction might plateau before reaching commercial viability. Environmental concerns could slow deployment. Fusion energy might mature faster than seawater uranium, making it obsolete. International competition or regulatory resistance could complicate deployment.

The most likely outcome is neither dramatic success nor complete failure, but rather a slow, incremental path where seawater uranium becomes a supplementary supply source alongside terrestrial mining, advanced reactors, and (eventually) fusion. It would represent a meaningful energy security achievement for China and any nation successfully deploying extraction technology, without the transformational impact either enthusiasts or critics imagine.

What's certain is that over the next 25 years, we'll learn a great deal about whether oceanic uranium extraction transitions from laboratory curiosity to industrial reality. China's kilogram of extracted seawater uranium is one step on that long path. Whether it leads somewhere consequential depends on decisions, investments, and breakthroughs that haven't yet occurred.

FAQ

What exactly is seawater uranium and why is it valuable?

Seawater uranium is dissolved uranium naturally present in ocean water at extremely low concentrations (approximately 0.003 parts per million). It's valuable because Earth's oceans contain roughly 4.5 billion tons of uranium, vastly exceeding all known terrestrial reserves combined. Unlike land-based uranium deposits that deplete through mining, seawater uranium continuously renews through geological processes, making it theoretically an infinite energy resource for nuclear power generation.

How does China's kilogram-scale extraction compare to commercial uranium mining?

China's extraction of one kilogram of uranium from seawater demonstrates controlled operation under real ocean conditions, validating that the technology works at modest scale. However, commercial uranium mining extracts thousands of tons annually. One kilogram represents a controlled demonstration, not commercial viability. To be economically relevant, extraction operations would need to scale up by six to seven orders of magnitude while maintaining or improving cost efficiency, which is extraordinarily challenging.

What are the main technical challenges preventing commercial seawater uranium extraction?

The primary obstacles include: (1) developing adsorption materials that selectively capture uranium while ignoring far more abundant saltwater minerals, (2) ensuring these materials survive hundreds or thousands of deployment and recovery cycles without degradation, (3) minimizing the energy cost of extraction, which currently exceeds profitable thresholds, and (4) scaling from kilogram-scale laboratory demonstrations to industrial operations producing thousands of tons annually. Each challenge requires breakthroughs in materials science, process engineering, and manufacturing that remain incomplete.

Can seawater uranium extraction actually achieve cost parity with terrestrial uranium mining?

Theoretetically yes, but practically it remains uncertain. Current terrestrial uranium costs

What's the energy return on investment (EROI) for seawater uranium extraction?

Energy return on investment remains the central unknown. Preliminary estimates suggest seawater uranium extraction could achieve EROI between 5:1 and 15:1 under optimistic assumptions, meaning you get 5-15 units of energy from the extracted uranium for every unit of energy spent extracting it. This is significantly lower than terrestrial uranium mining (30:1 to 50:1) but potentially acceptable if uranium becomes scarce and valuable enough. However, China hasn't publicly released EROI data from its pilot operations, so these remain projections rather than validated measurements.

How does seawater uranium extraction compare to fusion energy or other alternatives?

Seawater uranium extraction is a complementary approach, not a replacement for alternatives. Fusion energy, if commercialized (estimated 20-30 years away), would eventually supersede uranium-based nuclear power using deuterium from seawater. Breeder reactors can extend terrestrial uranium supplies 60-100 times. Thorium reactors offer an alternative nuclear fuel. Rapidly improving renewable energy with storage could reduce nuclear's role entirely. Realistically, multiple pathways will be pursued simultaneously, and whichever achieves commercial viability first will dominate energy markets.

What environmental risks does seawater uranium extraction pose?

Potential environmental concerns include: (1) bioaccumulation of uranium and radioactive isotopes in marine organisms near extraction platforms, (2) ecosystem disruption from deployment of millions of tons of adsorption materials, (3) disruption of commercial fishing in areas where platforms operate, (4) degradation of synthetic polymers releasing microplastics into the ocean, and (5) unknown effects of removing dissolved uranium from seawater at scale. While uranium concentrations in seawater are extremely low (minimizing acute toxicity risk), large-scale extraction's long-term ecosystem effects require careful study and potentially robust environmental impact assessments before industrial deployment.

Who's winning the seawater uranium race: China, the U. S., or other nations?

China currently leads in institutional commitment, demonstrated by state-backed funding and the deployment of a kilogram-scale offshore platform. However, the U. S. and Japan have produced world-class scientific research on adsorption materials and cost projections. India is emerging as a competitor given strategic interests in energy independence. The technology remains distributed across multiple nations and research institutions, but China's demonstrated willingness to fund large-scale pilot projects gives it a near-term advantage. The competitive dynamics will likely shift once technical breakthroughs accelerate development timelines.

What's the realistic timeline for commercial seawater uranium extraction?

Based on technology maturation curves and historical precedent, a realistic timeline suggests demonstration-scale operations (producing hundreds to thousands of tons annually) by 2040-2045, with potential for commercial viability by 2050. However, this assumes consistent funding, incremental technical progress, and no major setbacks. If significant challenges prove harder than anticipated or funding plateaus, commercial deployment could extend to 2060+. Conversely, if breakthroughs in adsorption materials or process engineering occur faster than expected, timelines could compress. The inherent uncertainty reflects the technology's current state: promising but unproven at commercial scale.

Would seawater uranium extraction make nuclear power truly sustainable?

Seawater uranium extraction would extend nuclear power's sustainability from roughly 90 years (with current terrestrial reserves) to effectively infinite, since oceanic uranium continuously renews. However, calling nuclear "sustainable" requires considering other factors: long-lived radioactive waste disposal, mining and processing environmental impacts, proliferation risks, and construction energy costs. Seawater uranium extraction solves the fuel scarcity problem but doesn't address these broader sustainability dimensions. Additionally, improved renewables and eventual fusion energy might make nuclear power less central to future energy systems, regardless of fuel availability.

Why is China's stated goal of "unlimited battery life" by 2050 linked to seawater uranium?

China's framing of "unlimited battery life" is strategic marketing that connects nuclear fuel availability to civilization's unlimited energy future. Currently, China imports 90% of its uranium from Kazakhstan, Australia, and Canada, creating geopolitical dependency. By developing indigenous seawater uranium extraction, China would achieve energy independence for nuclear fuel, ensuring its nuclear fleet could operate indefinitely without supply disruptions. This isn't literally about battery storage but rather about ensuring continuous nuclear reactor operation despite global uranium supply constraints. The metaphor signals China's ambition to make energy a non-limiting factor for civilization's growth.

TL; DR Summary

China's successful extraction of 1 kilogram of uranium from seawater represents genuine technological progress, but the gap between lab demonstrations and industrial-scale deployment remains vast. The ocean's 4.5 billion tons of dissolved uranium could theoretically power civilization indefinitely, but extraction remains expensive, energy-intensive, and operationally complex. Current costs run

Key Takeaways

- China successfully extracted 1kg of uranium from seawater under real ocean conditions, proving the technology works at demonstration scale but requires scaling up millions of times for commercial viability

- Seawater contains 4.5 billion tons of dissolved uranium compared to 6 million tons of terrestrial reserves, but extraction remains economically unproven due to extraordinarily low concentration (0.003ppm)

- Current seawater uranium extraction costs project at 2,000+ per kilogram versus150 for terrestrial mining; cost parity requires 75-90% reductions across materials, energy, and manufacturing

- China's 2050 'unlimited battery life' goal reflects strategic dependence on imported uranium from Kazakhstan and Australia; seawater extraction would achieve energy independence for nuclear fuel

- The United States, Japan, and India pursue seawater uranium research, but China leads with state-backed funding for large-scale offshore demonstration platforms and integrated supply chains

- Technical obstacles include developing adsorbent materials surviving thousands of deployment cycles, minimizing energy requirements, and scaling from kilograms to industrial thousands-of-tons-annually operations

- Realistic scenario suggests seawater uranium becomes a supplementary supply source (10-15% of demand) by 2050 rather than primary fuel source, serving strategic security more than economic displacement of terrestrial mining

Related Articles

- Songdian Micro Four Thirds Camera: M43's Salvation or Disruption? [2025]

- Living in AI Time: The Harsh Reality & Why We're Not Screwed [2025]

- Why Top Talent Is Walking Away From OpenAI and xAI [2025]

- Android 17 Beta: Complete Guide to Features & Release Timeline [2025]

- Best 4K Blu-ray Starter Packs for Ultimate Movie Quality [2025]

- Social Security Data Handover to ICE: A Dangerous Precedent [2025]

![Uranium From Seawater: China's Race Toward Infinite Nuclear Fuel [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uranium-from-seawater-china-s-race-toward-infinite-nuclear-f/image-1-1771018630077.png)