Why Dyson's Brand Extensions Are Failing: A Case Study in Market Expansion Gone Wrong

Dyson built an empire on one thing: making vacuum cleaners that actually work. For over two decades, the company operated in a zone of expertise so dominant that the brand name became synonymous with premium suction. Then something shifted.

Starting in the early 2010s, Dyson began a calculated expansion into adjacent categories. Hair styling tools, air purifiers, hand dryers, lighting, and even personal care devices. On paper, it made sense. The company had deep engineering talent, premium pricing power, and a loyal customer base willing to spend big on innovation. The execution, though? That's where the story gets messy.

What's fascinating isn't that Dyson tried to branch out. Most successful companies do. What's remarkable is how consistently these ventures have struggled to gain meaningful traction compared to the company's core vacuum business. And the reasons reveal something deeper about brand strength, market positioning, and the difference between reputation and actual competitive advantage.

This isn't about Dyson's products being bad. Some of them are genuinely impressive from a technical standpoint. This is about a company discovering that dominance in one category doesn't automatically grant you passage into others. It's a lesson that resonates far beyond Dyson, but Dyson's specific missteps offer one of the clearest recent case studies in how not to execute brand extension.

Let's break down what went wrong, why it matters, and what companies can learn from watching Dyson try to become more than just the vacuum people.

The Vacuum Empire: Where Dyson Built Its Fortress

Before we analyze the failures, we need to understand the foundation that made Dyson powerful in the first place. The company's vacuum business wasn't just successful. It was transformative.

When Sir James Dyson launched his first cordless vacuum in 1983, the market was dominated by upright models that had remained largely unchanged for decades. Dyson introduced a fundamentally different approach: bagless, transparent bin, cyclonic technology that actually worked. No loss of suction as the bin filled. No wrestling with bags. Just visible, reliable performance.

More importantly, Dyson built a narrative around engineering. Every product announcement included detailed explanations of what made it different. The company invested heavily in R&D. They made repairs easy. They backed their products with warranties that competitors couldn't match. By the time Dyson vacuums hit peak market share in developed countries, the brand had transcended being just a vacuum maker. It had become shorthand for "premium household appliance done right."

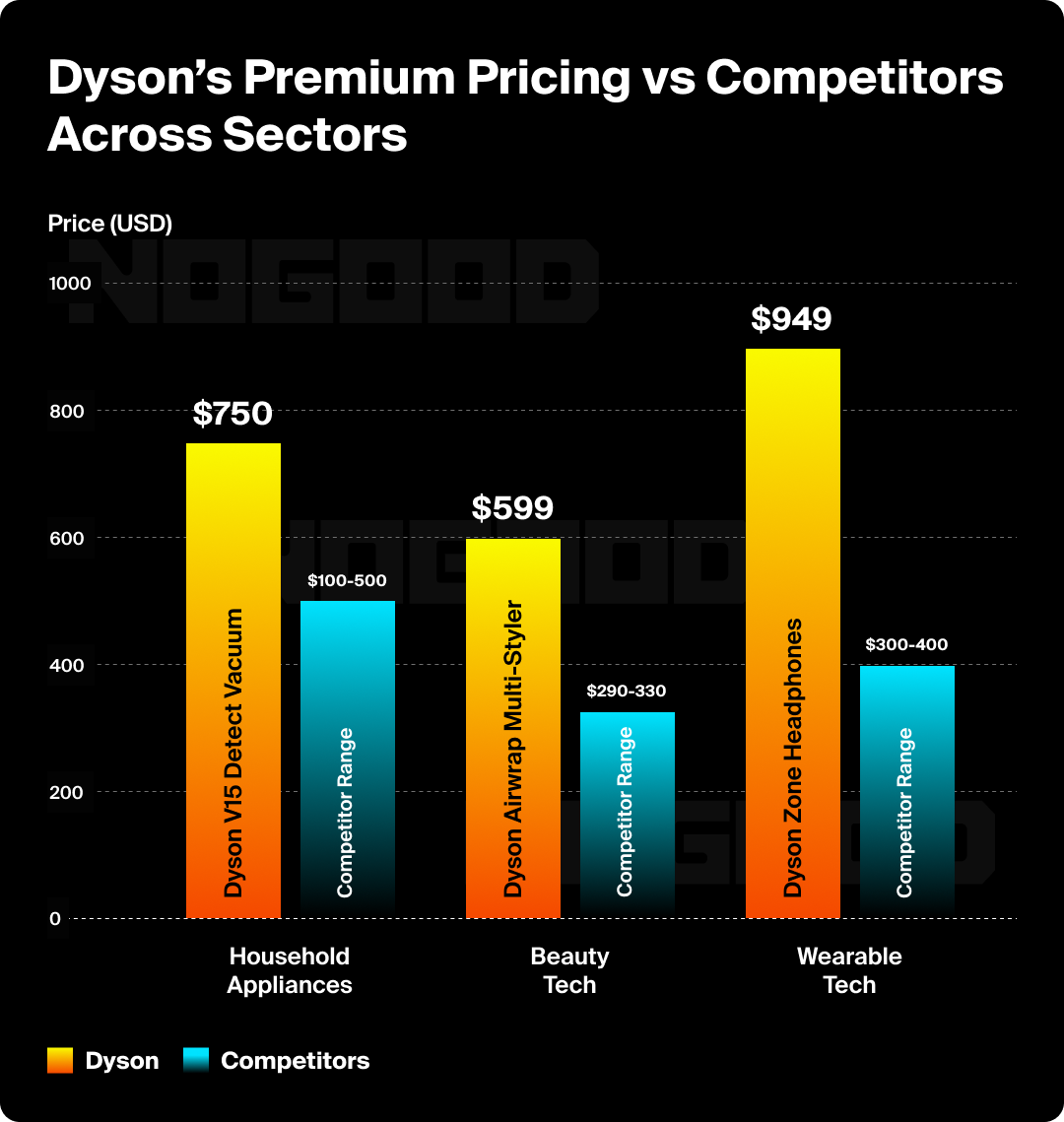

The margins were extraordinary. Dyson vacuums could command 60-100% price premiums over comparable models from established brands like Shark or Bissell. Customers paid it willingly. When you're selling a

That belief is what made Dyson's founders think they could replicate this success elsewhere.

The Hair Care Bet: Where It Started to Unravel

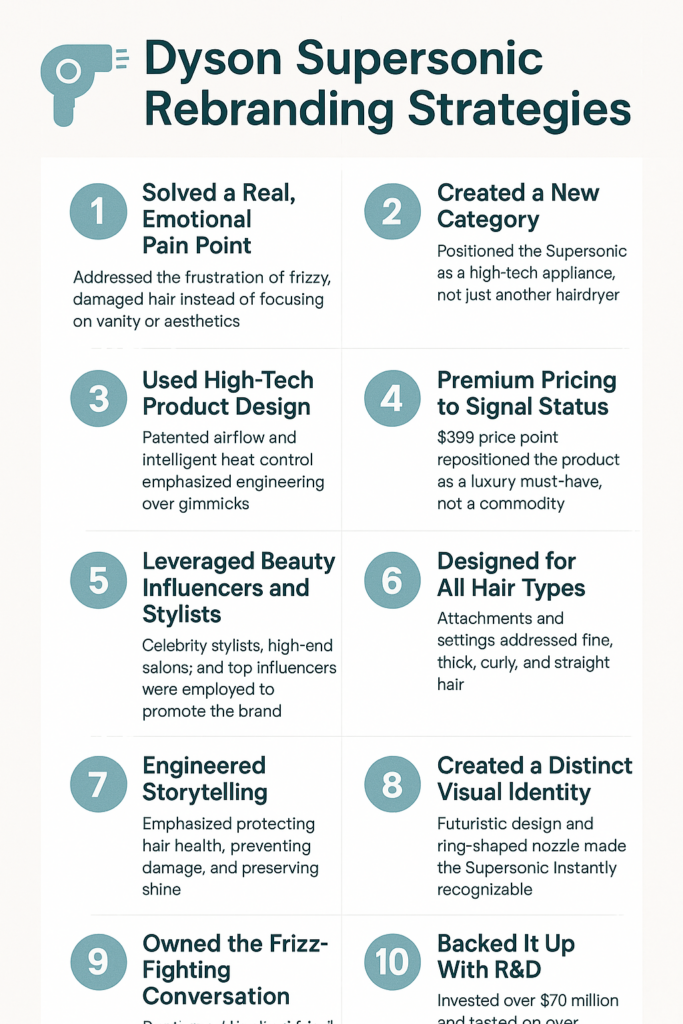

In 2016, Dyson launched the Supersonic hair dryer. Price:

Here's what Dyson got right: the product was genuinely well-engineered. They used ultrasonic technology to dry hair faster. They incorporated noise-reduction engineering. The motor was more powerful than competitors. From a pure innovation standpoint, this was textbook Dyson.

Here's what Dyson got wrong: they didn't understand that hair care buyers operate under completely different decision frameworks than vacuum buyers.

When you buy a vacuum, you're solving a problem you have every week. The purchase decision is made with rational calculation. Price per square foot of cleaning. Suction power. Runtime. Dyson's premium pricing worked because the vacuum category had legitimate performance differences you could measure and feel.

When you buy a hair dryer, you're buying based on styling results, brand prestige, and sometimes influencer recommendation. A GHD or a Dyson hair tool isn't better because it's engineered differently. It's better because that's what stylists recommend, and that becomes a self-reinforcing loop. A professional stylist won't recommend a Dyson hair dryer (even at $399) if they've already built their entire clientele on GHD or Parlux. And consumers won't buy it for prestige if the stylists they respect aren't using it.

Dyson brought vacuum-quality engineering to a category that doesn't value engineering. They brought a $399 price point to a category where professionals dictated recommendations. They brought corporate R&D to a category that runs on influencer networks and salon relationships.

The Supersonic did eventually find an audience, particularly in Asia where the Dyson brand name carried different weight. But in Western markets, it became a case study in what happens when you assume your brand strength transfers across categories.

Air Purifiers: The Me-Too Miscalculation

Around the same time as the hair care push, Dyson entered the air purifier market. This one is harder to critique on product grounds. Dyson's air purifiers are technically competent. They clean air effectively. They have good HEPA filtration.

But when Dyson entered the air purifier market, they were entering a space that already had established players with deep category expertise. Companies like Blueair had spent years building reputation in air quality. Winix and Coway had entire regional distribution networks optimized for appliance retail. Molekule had positioned themselves as the premium, tech-forward option. Levoit had built incredible efficiency.

Dyson brought a premium price point (vacuums typically cost

When you buy an air purifier, you care about: clean air. Quiet operation. Filter replacement costs. Brand reputation in that specific category. Dyson had none of these advantages. Yes, they had engineering talent. But so did every other player. Yes, they could market aggressively. So could Levoit, with their viral Tik Tok presence among Gen Z consumers.

What Dyson lacked was category credibility. They were the vacuum people trying to sell air purifiers, not air quality experts offering a new approach to purification. The consumer psychology is subtly but crucially different.

Air purifier sales for Dyson have remained flat compared to their vacuum trajectory. They claim market share gains in premium segments, but the overall picture is one of underperformance relative to investment.

Hand Dryers and the B2B Trap

Perhaps Dyson's strangest category expansion came with high-speed hand dryers for commercial spaces. This is worth examining because it reveals a different problem: sometimes a brand is just too specific to scale.

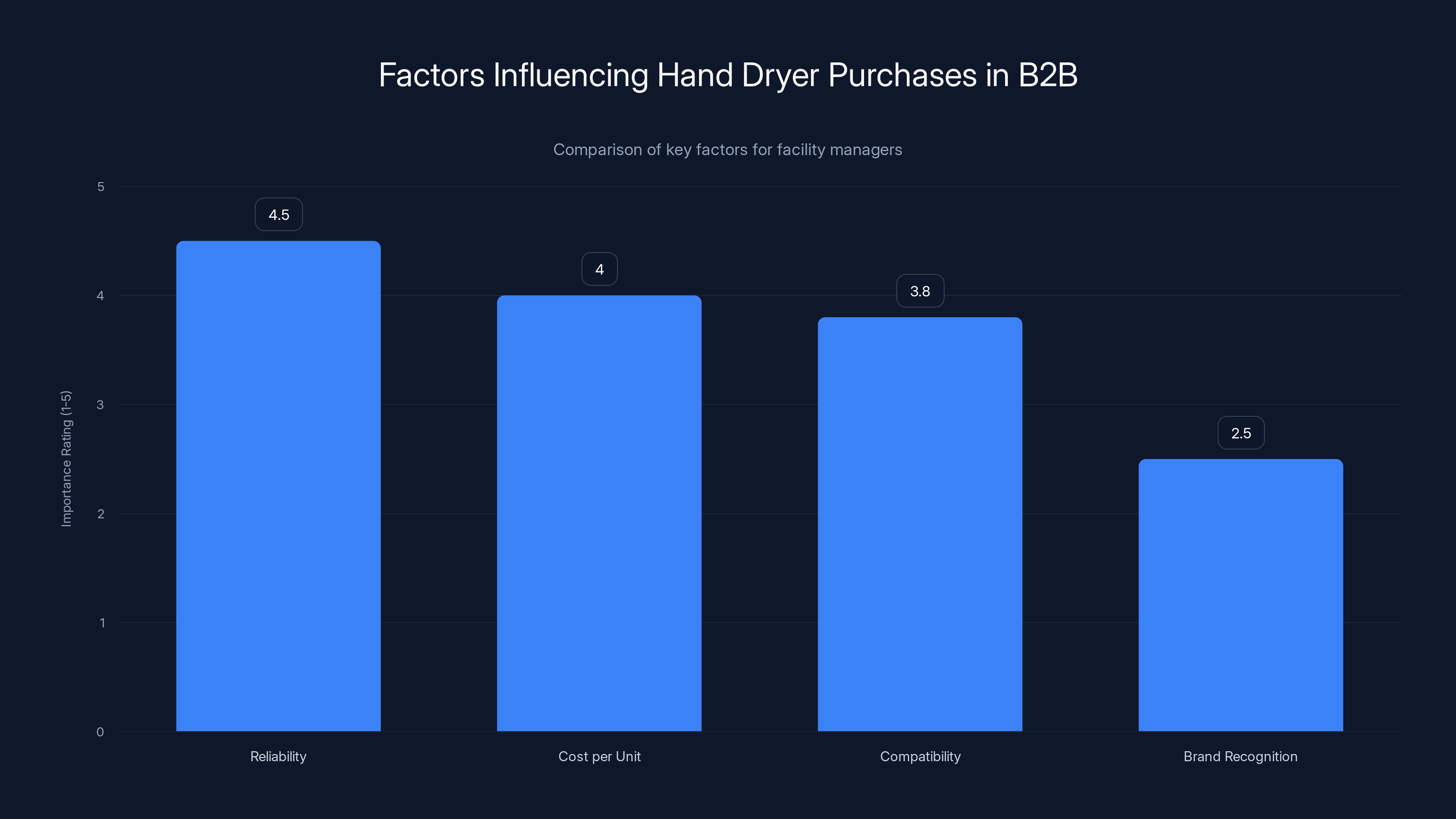

Dyson's commercial hand dryers are genuinely innovative. They dry hands in 10-15 seconds using digital motor technology. They cost more than standard options. Facility managers who've evaluated them report they perform well.

But here's the thing: nobody builds their cleaning supply strategy around hand dryer brands. Facility managers care about reliability, cost per unit, and compatibility with existing infrastructure. Dyson hand dryers are premium options in a category where "premium" is often invisible to the people using the product.

A consumer might spend more for a Dyson vacuum because they vacuum their own home and see the difference. A facility manager might approve a Dyson hand dryer, but the people using it don't know it's a Dyson. The decision is made on spec sheets and bid comparisons, not brand emotion.

This taught Dyson something valuable: B2B expansion is a different game entirely from B2C. You can't always just port your premium brand positioning into institutional sales.

Lighting: The Miscalculation of Design as Feature

In recent years, Dyson has made moves into lighting. Premium light fixtures, track lighting, and accent lighting at price points that significantly exceed basic alternatives.

This expansion reveals a tempting but dangerous assumption: that engineering excellence in one domain translates to design excellence in another. Dyson's lighting is well-built. The engineering is sound. But lighting design is about aesthetics, spatial harmony, and trend sensitivity in ways that vacuum design isn't.

A Dyson vacuum looks like a Dyson vacuum, and consumers are fine with that. They expect it to look functional because it is. A Dyson light fixture is competing against established design brands where the entire category is about how something looks in your space. Can you compete on engineering merit? Sometimes. But usually, you're competing on whether people think your light fixture makes their home look good.

Dyson's lighting offerings have remained niche, never achieving the mass-market penetration of their vacuum lines.

The Core Problem: Brand Strength Isn't Universal

What connects all these failures isn't that Dyson made bad products or bad decisions. It's that the company fundamentally misunderstood what their brand strength actually was.

Dyson's reputation isn't built on "premium engineering." Lots of companies claim that. Dyson's reputation is built on "solves a specific problem through innovation that's easy to see and feel."

With vacuums, you can immediately perceive the innovation. Cordless design. Transparent bins showing suction power. Lightweight construction. Ease of maintenance. These are tangible. You feel the difference the first time you use it.

With hair dryers, air purifiers, and lighting, the innovation is either imperceptible to the average user or irrelevant to their purchase decision. A

This reveals a hard truth about brand extension: your brand strength isn't infinitely transferable. It's specific to the problem you solve and the category you dominate.

Reliability and cost per unit are the most critical factors for facility managers when choosing hand dryers, while brand recognition is less important. Estimated data.

Why Dyson Thought They Could Succeed Everywhere

Dyson's confidence in extending their brand makes sense when you look at the underlying reasoning. The company had:

- Excess engineering talent with nowhere else to direct it

- Massive cash reserves enabling investment in new categories

- Demonstrated ability to command premium pricing in at least one category

- Strong global distribution networks that could stock new product lines

- Track record of technological innovation that won awards and media attention

From a strategic standpoint, the thinking goes: if we can do this in vacuums, why can't we do it in other categories?

The flaw is that this confuses inputs with outputs. Dyson could apply engineering talent, capital, and manufacturing expertise to new categories. But those inputs don't guarantee success when the market dynamics are fundamentally different.

It's like assuming that because you're excellent at making ice cream, you'll be excellent at making pizza. You might understand food production, supply chains, and taste. But ice cream success doesn't transfer to pizza because the categories have completely different competitive dynamics.

Dyson confused their operational excellence with market positioning strength. Operational excellence is necessary but not sufficient for success in new categories.

What Dyson Actually Should Have Done

If we map out what effective brand extension looks like, Dyson's missed opportunity becomes clearer.

Successful brand extensions typically follow a pattern:

-

Category adjacency matters. Extensions work best when you're moving into related categories where similar customer problems exist. Apple expanded from computers to phones because both solve information access problems. Dyson expanding from vacuums to hair dryers is a leap. Both are premium appliances, but they solve fundamentally different customer problems.

-

Brand strength must be problem-specific, not just premium. Tesla's expansion from cars to energy storage works because both solve the same underlying problem (sustainable, efficient energy use). Dyson's vacuum strength solves "how do I clean efficiently." That doesn't naturally translate to "how do I dry my hair" or "how do I purify air."

-

Category expertise matters more than brand reputation. Entering a new category requires understanding its unique dynamics. Dyson could have partnered with category experts rather than assuming they could dominate through engineering alone. Instead, they tried to lead categories where they had no credibility.

A smarter Dyson strategy might have been:

- Stay focused on cleaning and air flow problems. Expand within the broader home cleaning category (carpet cleaning systems, more specialized vacuums for specific use cases, commercial cleaning) rather than leaping into completely different categories.

- Use strategic partnerships to enter adjacent categories rather than building everything from scratch. Partner with Normann Copenhagen on lighting design rather than trying to design lights yourself. Partner with established hair care brands rather than building from zero.

- Leverage brand strength selectively. Identify which extensions truly benefit from the Dyson name (commercial cleaning equipment, perhaps) versus which don't (fashion accessories, for example).

Instead, Dyson tried to become a diversified home appliance company selling premium versions of everything, and the market rejected the premise.

The Lesson for Other Premium Brands

Dyson's experience offers crucial lessons for any brand considering expansion:

Your brand strength is more specific than you think. What made you powerful in your core category won't automatically make you powerful elsewhere. Dyson owned vacuums because they solved a clear problem better than anyone else. That didn't make them the best at solving hair care problems, and the market correctly identified the difference.

Premium pricing requires category credibility. Dyson could command 60-100% premiums on vacuums because they were clearly the best option. They couldn't command similar premiums on hair dryers because GHD and other established brands had that category's credibility. Pricing power is category-specific, not brand-specific.

Customers evaluate extensions differently. When someone buys a Dyson vacuum, they're buying into proven category leadership. When they see a Dyson hair dryer, they're questioning whether Dyson knows hair as well as GHD. It's a different evaluation entirely. You're fighting skepticism instead of riding certainty.

Engineering isn't the same as category fit. Dyson's extensions often failed not because the products were poorly engineered but because engineering excellence doesn't matter equally across categories. A vacuum buyer cares deeply about motor efficiency. A lighting designer cares about aesthetics and spatial harmony. You're solving for the wrong variable.

Why Some Extensions Worked Better Than Others

It's worth noting that Dyson's extension strategy wasn't entirely unsuccessful. Some product lines gained meaningful traction.

The Dyson V15 and subsequent cordless vacuum models achieved remarkable success, but these weren't really extensions—they were iterations on the core business. The company got better at what they already did, rather than doing something new.

The Dyson air purifier line, while underperforming relative to investment, did establish some presence in premium segments, particularly in Asia where the Dyson brand carries different cultural weight and premium positioning is more valued across categories.

The hair care tools saw moderate success, particularly in professional and styling communities, suggesting that if Dyson had invested more in building category credibility through salon partnerships and professional networks rather than just launching a premium product, the outcome might have been different.

What these partial successes reveal is that execution and market education matter. But they also reveal that even well-executed extensions struggle without category fit.

The Bigger Picture: When Focus Beats Diversification

In the current era of business strategy, there's constant pressure to diversify, to grow, to expand into adjacent markets. The argument goes: if you've succeeded once, why not try elsewhere? Why leave growth on the table?

Dyson's experience suggests a contrarian answer: sometimes growth comes from deepening category dominance, not expanding it.

Consider that Dyson's vacuum business, despite now competing in a category where cordless vacuum technology is becoming table stakes rather than revolutionary, still generates the vast majority of the company's revenue and profit. It's the business that works because it's the business where Dyson has legitimate category advantages.

Meanwhile, the hair care, air purifier, lighting, and hand dryer lines are steady but unremarkable contributors. They're not failures in the sense that they lose money (they presumably don't), but they're also not successes in the sense that they meaningfully drive the company's future growth.

A different strategy might have been: what if Dyson had invested the capital, talent, and energy they poured into hair dryers and air purifiers back into dominating vacuums even harder? What if they'd spent billions building distribution in emerging markets specifically for cordless vacuums, rather than spreading those resources across categories?

Would that have been less exciting? Probably. Would it have generated as many press releases and announcements of "new categories"? Definitely not. Would it have been more profitable and more defensible long-term? Almost certainly.

The Psychology of Brand Extension: Why Companies Keep Trying

There's something psychologically appealing about brand extension. For a founder or CEO, it signals growth and ambition. It suggests the company is becoming something bigger. It creates opportunities for new announcements, new products, new markets.

There's also a genuine business logic to it. If you've built a successful company, you likely have:

- Excess capacity in manufacturing and distribution

- Strong balance sheet that can fund new ventures

- Talented team that could tackle new challenges

- Brand awareness that gives you a head start in new categories

These inputs make the decision to diversify seem logical. But as Dyson demonstrates, inputs don't determine outputs in brand extension. The market does.

Dyson had all the inputs needed to succeed in hair care, air purification, and lighting. But it lacked the one thing that couldn't be substituted: category fit and the specific brand strength required to win in each of those categories.

This is why most brand extensions fail. Companies extrapolate from success in one domain and assume they can replicate it elsewhere. The market, though, is more precise. It evaluates brands specifically within their category context. Cross that context, and the brand strength doesn't transfer.

Looking Forward: Can Dyson Recalibrate?

The question now is whether Dyson recognizes this pattern and adjusts course. There are signs the company is actually doing this.

Recent Dyson announcements have focused more heavily on vacuum innovation—new motor technology, improved battery efficiency, quieter operation. There's been less emphasis on pushing into entirely new categories and more focus on defending and improving the core business.

This is sensible strategy. Own vacuums completely. Become undeniable in that category. Use the profits and prestige from vacuum dominance to fund selective extensions only where there's genuine category adjacency and competitive advantage.

Such a strategy won't generate as many "Dyson enters new category" headlines. But it's more likely to generate profitable, sustainable growth.

For Dyson, the lesson appears to be: you can't be great at everything. Focus on what you're great at, dominate that space, and be exceptionally selective about expansion. That's not sexy strategy, but it's sound strategy.

And perhaps that's the broader lesson for anyone building a brand: be excellent at one thing, get strong, and only move into adjacent territory when you have genuine competitive advantages, not just capital and ambition.

FAQ

Why did Dyson's brand extension strategy fail?

Dyson's extensions failed primarily because the company confused operational excellence with market positioning strength. While Dyson had engineering talent and capital to execute new products, they lacked specific category credibility and brand strength in hair care, air purification, and lighting. Brand reputation doesn't automatically transfer across categories—a Dyson vacuum buyer trusts Dyson on suction power, not hair styling results or air quality expertise. The company essentially tried to enter categories where they had no competitive advantage beyond their name, and the market correctly identified this weakness.

What's the difference between brand strength and brand reputation?

Brand reputation is how well-known your brand is. Brand strength is how well-known you are for solving a specific problem. Dyson has strong reputation generally, but their actual competitive strength comes from their dominance in vacuums and cordless cleaning technology. In hair care, even with brand awareness, Dyson lacked the category credibility that GHD and professional stylists had built over decades. You can have excellent brand reputation but weak competitive strength outside your core category.

Can successful companies successfully diversify, or should they stay focused?

Diversification can work, but it requires genuine adjacency. Apple successfully expanded from computers to phones because both solve information access problems. Dyson tried to expand from vacuums to hair dryers—a much larger leap—and struggled because the categories serve different customer needs and operate under completely different competitive dynamics. The rule isn't "never diversify," but rather "only diversify when you have genuine category advantages, not just capital and brand awareness." Dyson should have either stuck to cleaning-related products or partnered with established players in new categories rather than trying to dominate everything alone.

Why do premium brands struggle more with category extensions?

Premium brands build their strength through perceived leadership in a specific domain. When they extend, customers evaluate them in the new category by whether they're still leaders, not whether they're premium. A Dyson vacuum at

What should Dyson have done differently?

Dyson had three better options: First, stay focused on cleaning and air flow problems—extend within related categories rather than leaping into completely different ones. Second, use strategic partnerships with established brands in new categories rather than building from scratch. Third, be far more selective about which extensions genuinely benefit from the Dyson brand name (perhaps commercial cleaning equipment would have worked better than consumer air purifiers). Instead, Dyson tried to become a diversified premium appliance company, and the market rejected the premise. Focus and selectivity would have been more profitable than ambition.

How can companies test whether a brand extension will work before full launch?

The best indicator is category adjacency and genuine competitive advantage. Ask: Do customers in this category face the same core problem we solve? Do we have specific expertise or capability advantages in this category, or just capital and brand awareness? Would established players in this category see us as a serious competitor based on capability, or as a outsider trying to enter on brand name alone? Dyson could have asked these questions about hair care and realized the answers weren't favorable. Early market testing can help, but fundamentally, the strategic fit matters more than any single data point. If the category fit is wrong, even successful pilots won't translate to long-term growth.

Is Dyson's brand still valuable in their core vacuum business?

Absolutely. Dyson remains the premium vacuum leader in most developed markets. Their core business generates strong margins and market share. The issue isn't that the Dyson brand is weak—it's that it's specifically strong in vacuums, not everywhere. The company should leverage this strength by deepening vacuum dominance rather than spreading brand equity across categories where it's less relevant. In fact, protecting and reinforcing their vacuum leadership might be more valuable long-term than chasing growth in adjacent categories.

What does Dyson's experience teach other tech companies about brand extensions?

The core lesson is that technological excellence and R&D capability don't automatically translate into success in new categories. Apple works in multiple categories partly because they focus on the problem (how people interact with information and entertainment) rather than the product type. Dyson tried to translate motor engineering expertise into unrelated categories, forgetting that the core strength was about solving vacuum problems, not about motors in general. Other tech companies should ask: Is our brand strength about the underlying technology, or about solving a specific customer problem? If it's the former, extensions might work. If it's the latter, they probably won't unless the new category addresses the same fundamental problem.

Could Dyson have succeeded in hair care with a different strategy?

Possibly, but it would have required acknowledging upfront that they lacked category credibility and investing heavily in building it. Instead of launching a $399 hair dryer on brand name alone, Dyson could have partnered with established stylists, built professional credibility first, then launched to consumers. They could have acquired an established hair care brand to gain instant category expertise rather than building from scratch. Or they could have positioned the Dyson hair dryer not as a competitor to GHD but as a complementary styling tool that solved a different problem. Instead, they treated it like a vacuum launch—premium price, technology focus, brand heritage—and the market correctly identified that this strategy didn't fit the category.

Key Takeaways

Dyson's brand extension failures reveal a critical business truth: operational excellence and brand awareness don't transfer automatically across categories. The company dominated vacuums through genuine innovation in cleaning technology, but that strength didn't grant them advantages in hair care, air purification, or lighting.

Brand strength is category-specific. Dyson's reputation came from solving a clear problem (efficient cleaning) better than anyone else. When they moved into categories where they had no competitive advantage beyond their name, the market rejected the premise. You can't simply be "the premium brand that does everything well."

Successful diversification requires genuine adjacency and competitive advantage, not just capital and brand awareness. Most brand extensions fail because companies confuse inputs (money, talent, brand awareness) with outputs (market success). Dyson had the inputs but lacked the category-specific advantages needed to win.

Focus often beats diversification. Dyson's core vacuum business remains their most successful, most profitable line. The billions invested in adjacent categories generated far lower returns. A strategy of deepening vacuum dominance might have been less exciting but more profitable.

The smartest brands recognize the limits of their strength. The lesson isn't that companies shouldn't diversify. It's that they should diversify only when they have genuine competitive advantages in the new category, not just hope that their brand reputation will carry them. Strategic partnerships, acquisitions, and selective expansion beat the "let's make premium versions of everything" approach.

![Why Dyson's Brand Extensions Are Failing: A Case Study [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-dyson-s-brand-extensions-are-failing-a-case-study-2025/image-1-1770154879779.jpg)