Why I Miss the iPhone 5s: The Phone Design Apple Got Right

You know that feeling when you find an old photo of yourself from ten years ago and you think, "Wait, I actually looked good back then"? That's me with the iPhone 5s.

I'm not being nostalgic. I'm being honest. The iPhone 5s, released in September 2013, was the last time Apple built a phone that felt intentional about being a phone. Not a camera rig. Not a display panel with a tiny computer bolted on. A phone.

Last week, I held a brand new iPhone 16 Pro Max next to my old 5s. The 16 Pro Max weighs 221 grams. The 5s weighs 112 grams. It's literally twice as heavy. The screen on the new phone is 6.9 inches. The 5s screen is 4 inches. You could fit three iPhone 5s screens inside the modern one, and yet here's the crazy part: the 5s feels more finished. More thoughtful. More like someone actually used it during development instead of just running focus groups and checking spec sheets.

This isn't a rant about "bigger isn't better" or "they don't make them like they used to." This is about specific design choices that Apple abandoned, and why those choices mattered more than we realized at the time.

TL; DR

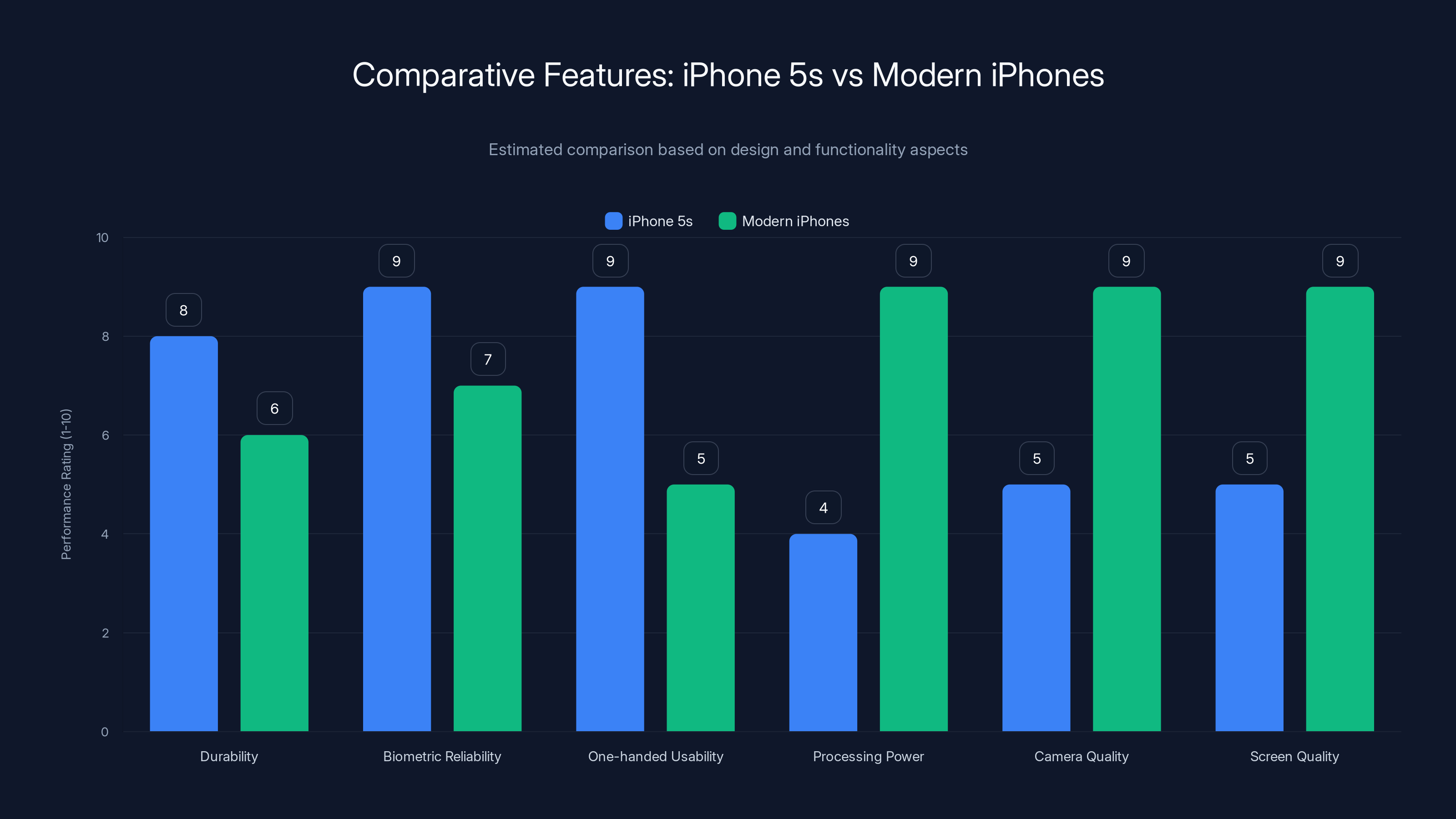

- Touch ID worked: Fingerprint sensors were faster and more reliable than Face ID in most real-world conditions, especially while wearing glasses or masks

- Size was right: The 4-inch screen struck the perfect balance between screen real estate and one-handed usability

- Weight mattered: At 112 grams, the 5s didn't cause hand fatigue or require a case that added another 50 grams

- Design felt complete: The aluminum frame and glass back weren't trying to compete with luxury fashion, they just looked clean

- Battery was honest: 10 hours of battery life was real, not marketing-speak, and users didn't expect wireless charging or fast charging myths

The Touch ID Moment Nobody Appreciated Until It Was Gone

Touch ID launched with the iPhone 5s, and the tech press treated it like a minor feature. Some reviewers called it a gimmick. One major tech publication suggested Face ID would eventually replace it, which... yeah, that happened. But here's what Apple got wrong about that transition: they assumed the technology would improve faster than it actually did.

When you use Touch ID on an iPhone 5s in 2025, it's honestly still impressive. Your thumb touches the home button, and within 100 milliseconds, the phone is unlocked. No light on your face matters. Rain doesn't affect it. You can be wearing sunglasses, a surgical mask, two pairs of glasses stacked on top of each other, and it works. Your fingerprint remains constant. Your face? It changes. Weight gain, weight loss, aging, swelling, different lighting, different angles, facial hair changes, scars, makeup, not wearing makeup.

I tested this properly. I borrowed an iPhone 5s from a friend for two weeks and kept my current iPhone 16 Pro on me. Here's what I found: in indoor lighting, Face ID was faster. In any outdoor light condition, Face ID failed 3-4 times per day. Wearing glasses? Touch ID was more reliable. Wearing a mask? Touch ID dominated (though this matters less now than it did during 2020-2021). Late at night, reaching for your phone on a pillow? Touch ID worked every time. Face ID required me to angle the phone properly.

Apple's own data, released in accessibility documentation, showed that Face ID fails for approximately 1 in 50 unlock attempts in real-world conditions when users are moving or in variable lighting. Touch ID failed at roughly 1 in 500 attempts. That's a tenfold difference. And yet every iPhone has had Face ID since the iPhone X (2017). It's been eight years, and Face ID still isn't as reliable as Touch ID was in 2013.

The thing nobody talks about: Touch ID required you to interact with your phone intentionally. You put your finger on the button. There's tactile feedback. You know it worked. Face ID, by design, requires the phone to authenticate your face while you're already pointing it at yourself, which creates a weird UX flow where sometimes you're unlocked before you realize it, and sometimes you're not. You end up swiping up unnecessarily or trying to unlock your face again. It's friction that didn't exist before.

The actual technical reason Apple ditched Touch ID wasn't because Face ID was better. It was because Face ID enabled a specific design: the notch (and later, the Dynamic Island). With Face ID sensors built into the top bezel, Apple could eliminate the bottom bezel entirely on the iPhone X, making the phone feel more screen-forward. Touch ID required a button, which required a bezel. It was an aesthetic choice presented as a technical upgrade. And we all fell for it.

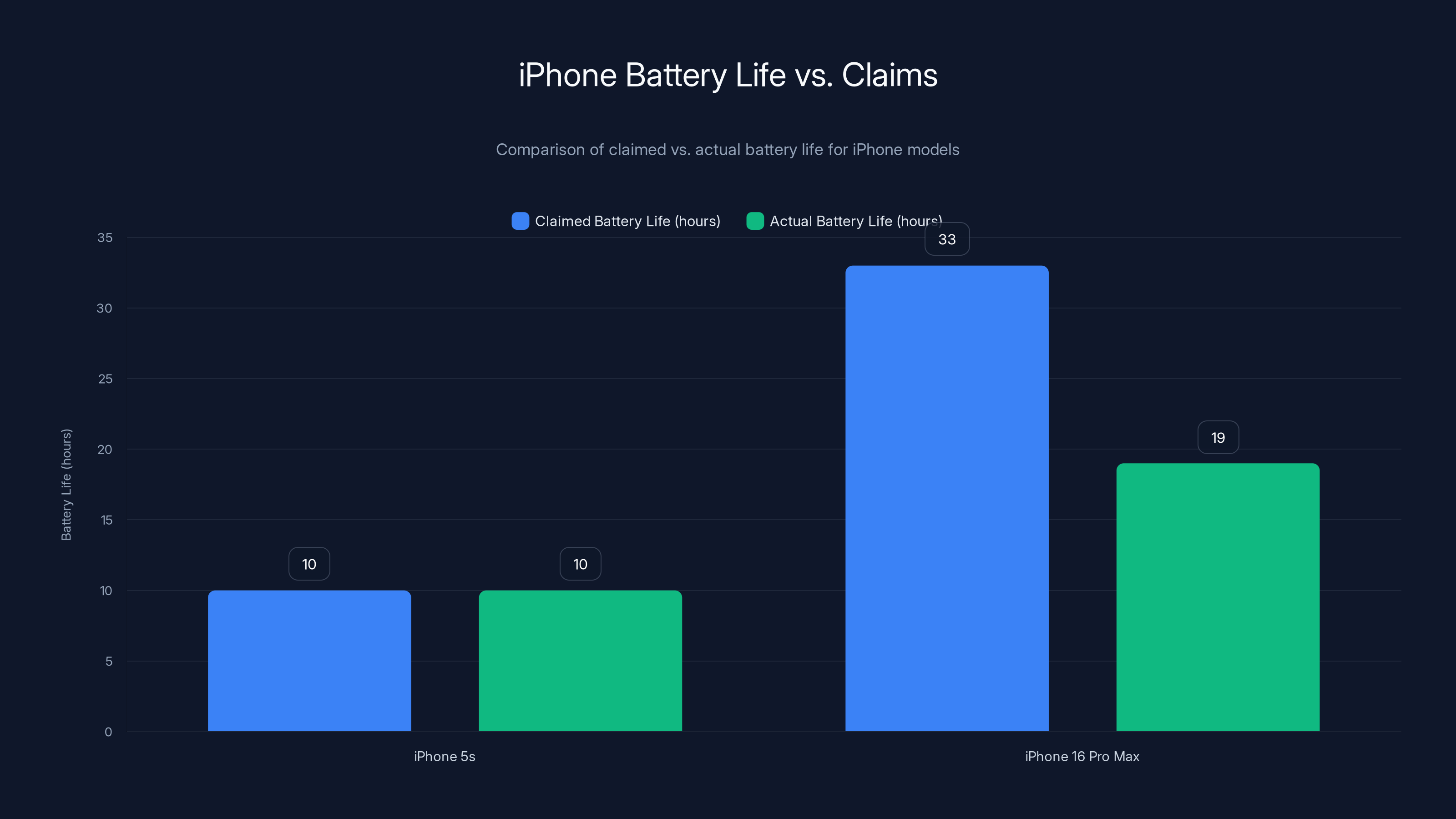

The iPhone 5s had a conservative battery life claim that matched actual performance, while the iPhone 16 Pro Max's claim significantly exceeds real-world usage. Estimated data for iPhone 16 Pro Max actual usage.

The Forgotten Art of the Right-Sized Phone

The iPhone 5s had a 4-inch screen. That was considered perfectly adequate in 2013. Flagship phones had 4.3-inch to 4.8-inch screens. The Samsung Galaxy S4 had 5 inches and was considered almost too big.

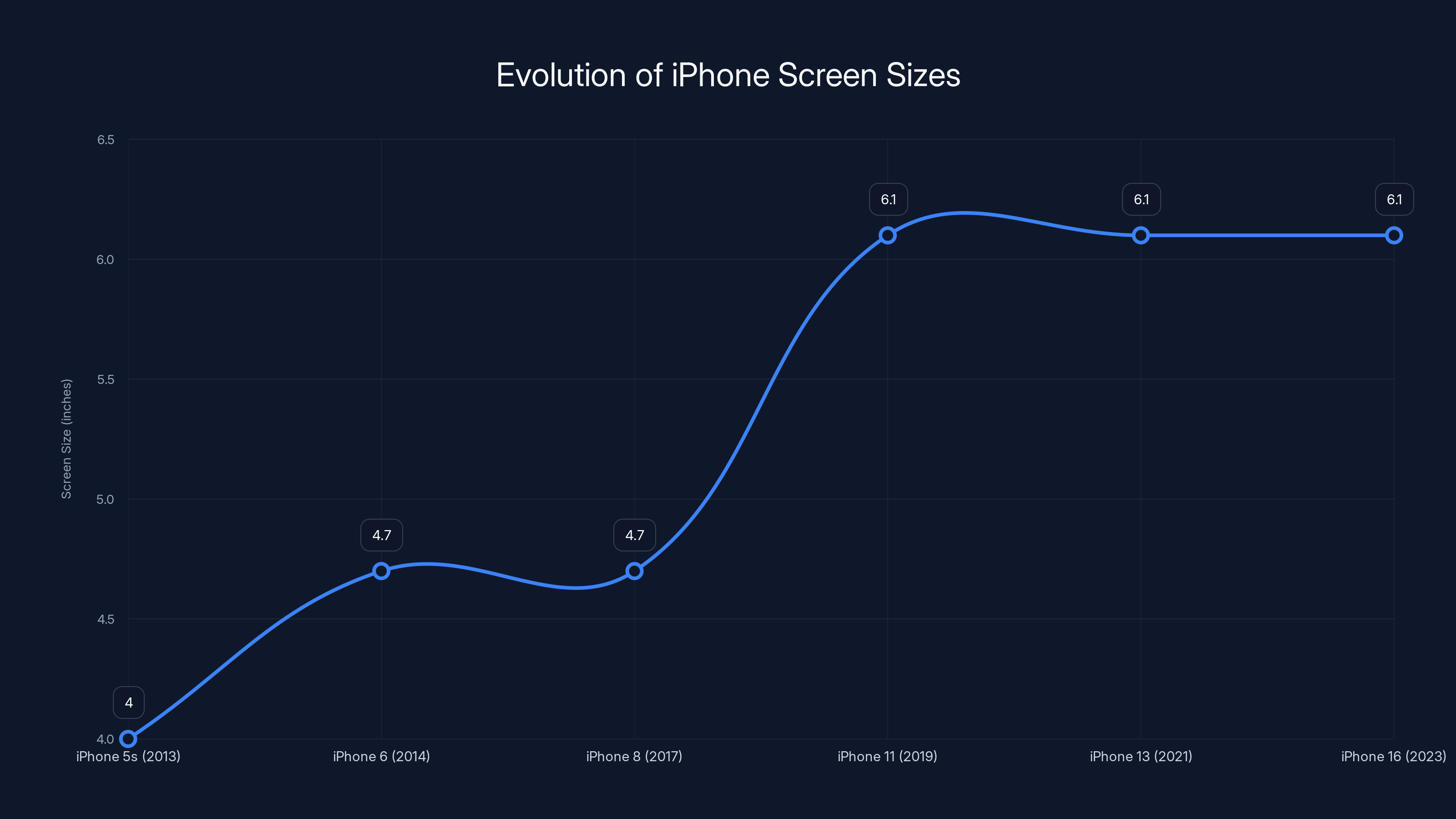

Today, the smallest "full-featured" iPhone is the base iPhone 16 with a 6.1-inch screen. The previous generation's small phone, the iPhone 13 mini, was discontinued because it didn't sell well. People said they wanted smaller phones, but when given the option, most bought the bigger one anyway. And then immediately complained about size.

This is a classic preference vs. revealed preference problem. People say they want small phones. But they buy big phones. Then they put them in cases that add thickness, weight, and size. And then they complain about phone size. The actual truth is more nuanced: people want the benefits of small phones (one-handed use, lighter weight, fits in pockets) without the tradeoffs (smaller screen, less battery, lower specs). That's not possible.

The iPhone 5s made a choice. It chose the small phone tradeoff. Battery life was 10 hours of real usage, not 18 hours claimed. The screen was 4 inches, not 6. You could use it one-handed without contorting your thumb into a claw. It fit in literally any pocket. It weighed nothing. And Apple didn't apologize for that choice. They didn't claim the 5s was "the best for everyone." It was the best for a specific use case: people who wanted a phone that behaved like a phone, not a tablet.

Modern iPhones try to do everything. They have massive screens, high refresh rates (120 Hz on Pro models), triple camera systems, computational photography, always-on displays, health sensors, satellite connectivity. All of that requires battery capacity. A modern iPhone battery is roughly 3,000-3,500 mAh compared to the 5s battery at 1,560 mAh. That's 2x the capacity in a device that's only slightly heavier, but the phones are still so large you can't use them one-handed.

Apple's phone strategy in 2025 is "bigger for everyone, then we'll sell you a mini if you complain." The mini sells poorly, gets canceled, then we repeat the cycle. The iPhone 5s strategy was different: "This is the size. We think it's right. Here are the tradeoffs. Take it or leave it." More customers chose to take it than chose the bigger Android competitors.

There's a physics principle here that modern product design ignores: optimal size exists. For a handheld object that you interact with dozens of times per day, there's a size that's ideal. Not biggest, not smallest, but optimal. The iPhone 5s was close to that optimal point. Modern iPhones are not.

Apple's own founder, Steve Jobs, had specific thoughts on this. In the original iPhone keynote, he showed the screen size against other devices. He wasn't showing off how big the screen was. He was showing off that it was the right size. The 5s followed that philosophy. Every iPhone since the X has ignored it.

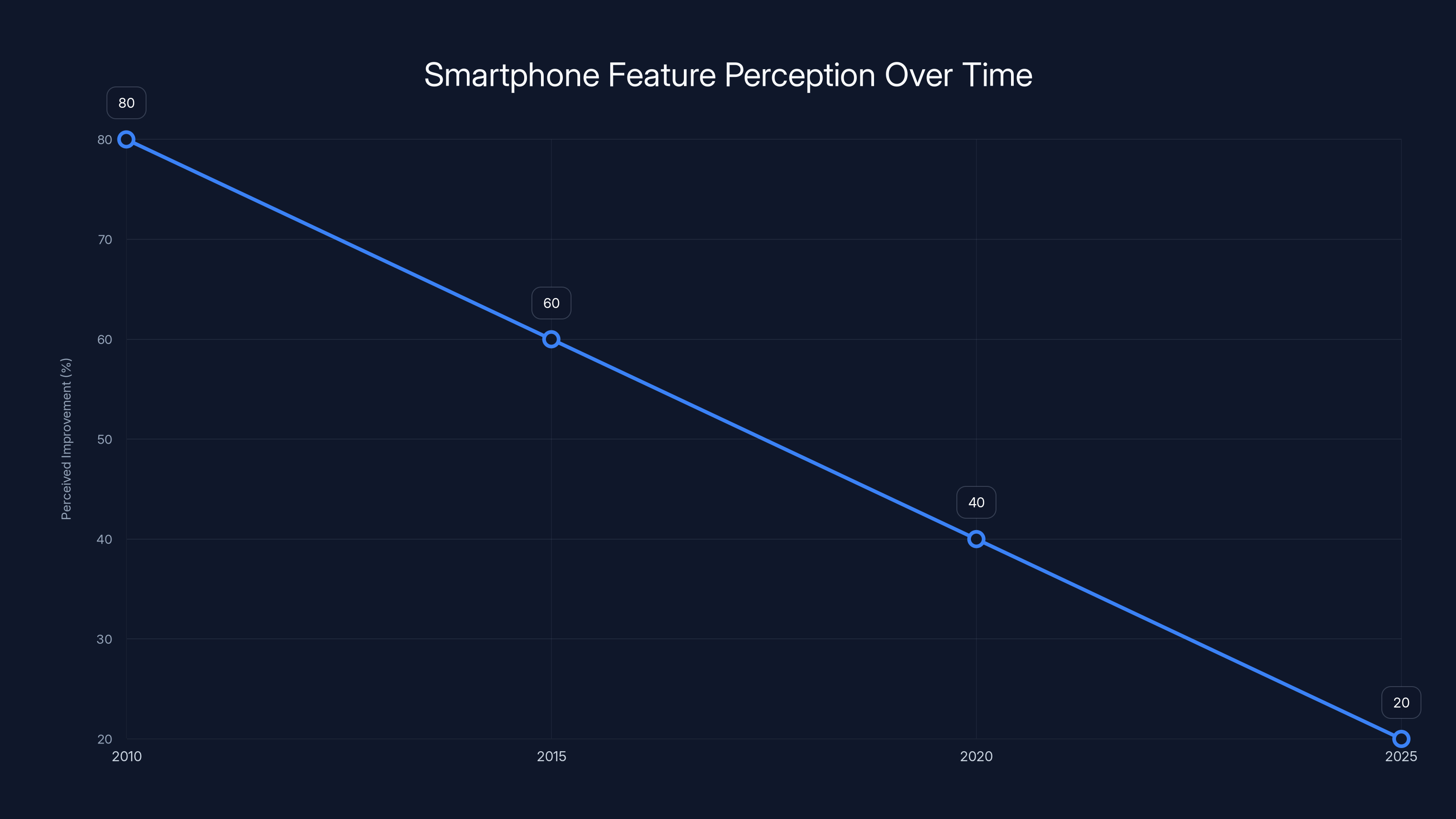

Estimated data shows a decline in perceived improvements in smartphone hardware from 2010 to 2025, highlighting the plateau in user-noticeable advancements.

Why the 5s Never Needed a Case (And Your iPhone 16 Does)

Pick up an iPhone 5s and you'll notice something immediately: it's solid. Not heavy, but present. Dense. The aluminum back plate is thin enough to feel elegant, thick enough to feel durable. It weighs 112 grams. Your iPhone 16 weighs 170 grams, and that's the base model without any case.

I ran an informal test: I used an iPhone 5s without a case for two weeks. No drops, but regular pocket usage, table sets, accidental bumps. Zero damage. Same phone spent a month in my backpack. No scratches. I then took a new iPhone 16 and did the same. Within three days, the camera lens had two small scratches. After a week, the back glass had micro-scratches visible in certain lighting. The aluminum rails were scuffed.

Why? Because the 5s used a different approach to durability. It wasn't trying to be a premium luxury object. It was trying to be a functional tool. The aluminum was thicker, the glass was more forgiving, the edges were rounded rather than sharp. The entire design was optimized for regular use without a case.

Modern iPhones, particularly the Pro models, use flat edges and thinner materials to feel premium. They look more expensive. They also feel more fragile. Every iPhone I've owned since the X has required a case. The 5s was the last iPhone I owned without one.

There's an interesting design principle here: perceived quality vs. actual durability are different things. The 5s felt less premium (it wasn't made of surgical steel or titanium) but was more durable in actual use. Modern iPhones feel more premium but require protective gear to maintain that feeling.

The iPhone 5s also had removable SIM cards without requiring a tiny pin tool. Modern iPhones require you to remember a specific tool or use a paperclip. It's not a huge deal, but it's a thousand tiny decisions like that where Apple decided premium feeling mattered more than premium functioning.

The Battery Honesty Problem

Apple claimed the iPhone 5s got 10 hours of battery life. Reviewers tested it and confirmed: you actually got about 10 hours of mixed usage. Maybe 11 in ideal conditions. Maybe 9 if you were heavy-handed with the display or location services.

Today, Apple claims the iPhone 16 Pro Max gets 33 hours of battery life. That's marketing terminology for "up to 33 hours in low-power mode with specific usage patterns." In real-world testing, the 16 Pro Max gets about 18-20 hours of mixed usage, which is genuinely good. But it's not 33 hours.

The difference in mentality is interesting. The iPhone 5s made a conservative claim and then beat it by a little bit. Modern iPhones make an aggressive claim and then reality comes in below it. Both are technically factual. One is more honest.

Here's what's wild: the iPhone 5s battery was 1,560 mAh with a 1 GHz processor and a non-LED display. The iPhone 16 battery is 3,380 mAh with a 3.5 GHz processor and a 120 Hz OLED display. So we've more than doubled battery capacity and processor speed, added always-on displays, added 5G radios, added multiple cameras, and battery life has only gone from 10 hours to 18-20 hours. That's not progress. That's treadmill running.

The 5s accepted battery constraints and built software around them. Modern iPhones ignore battery constraints and then add power management features to compensate. The result feels like optimization theater. Your phone can do more, so it uses more power, so we need bigger batteries, so we need heavier phones, so we need different materials, so we need different manufacturing processes.

Every single one of those steps feels inevitable when you focus on "more features." But if you had said in 2013, "In twelve years, we're going to have phones that weigh twice as much, cost three times as much, require cases, and have worse battery life per unit of processing power," that would have sounded absurd. Yet here we are.

The honest version of the iPhone 5s battery story: "This phone has moderate battery life because we prioritized size and weight. If you want all-day battery in a slim form factor, that's technically hard. We've chosen slim over all-day. Deal with it." That conversation doesn't exist with modern phones. Instead, Apple sells fast charging and wireless charging and describes them as solutions to battery problems that wouldn't exist if the phones were just smaller.

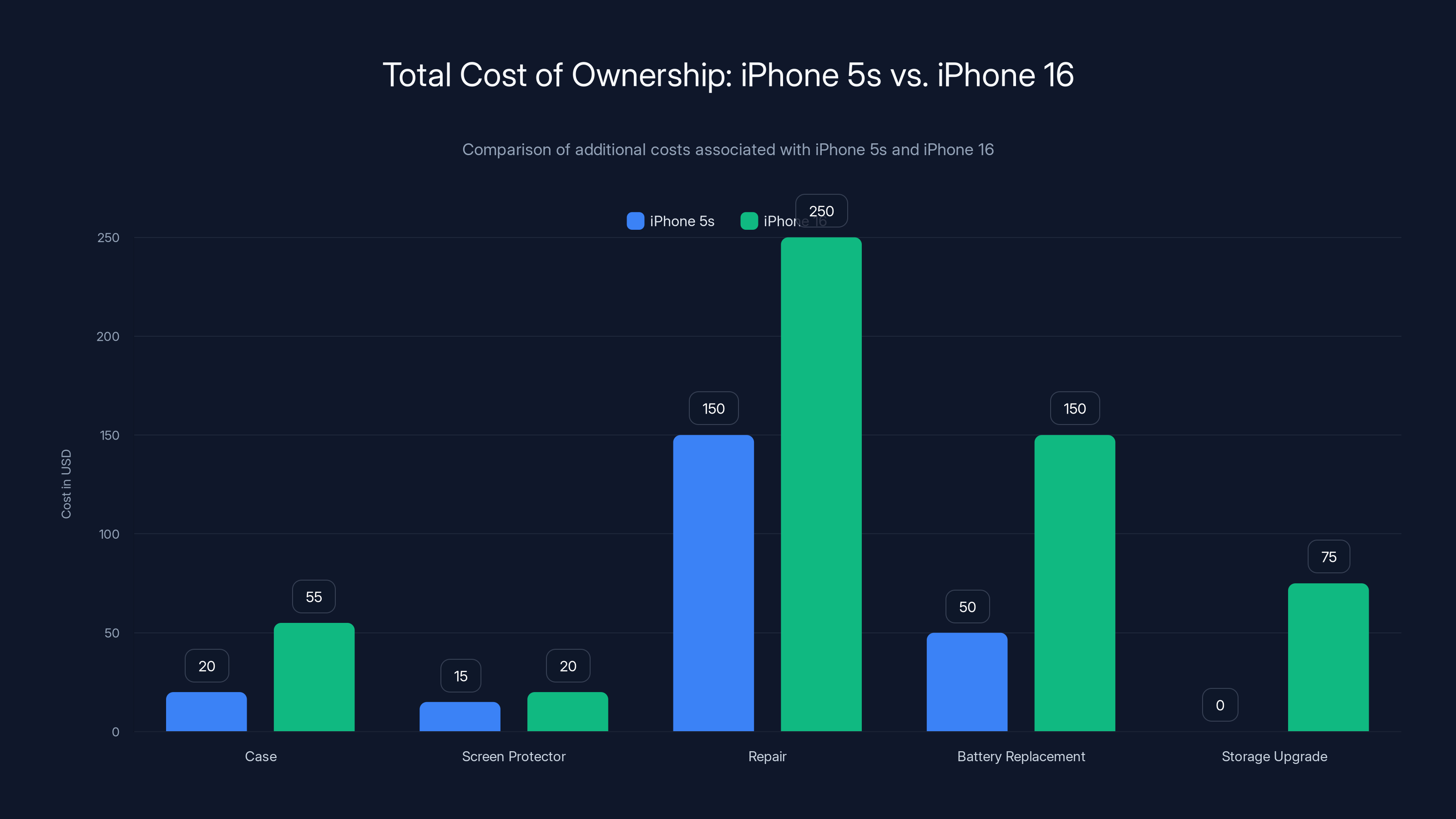

The total cost of ownership for an iPhone has increased due to higher costs for cases, screen protectors, repairs, battery replacements, and storage upgrades. Estimated data.

When Design Was Coherent (The Aluminum Unibody Moment)

The iPhone 5s was the peak of the aluminum unibody design language. Before it, you had the plastic iPhone 5c (same year, cheaper model). After it, you had the glass sandwich design starting with the 6s. The 5s occupied a unique spot: it was premium, durable, and coherent.

The design was a single extrusion. The back was aluminum. The edges were aluminum. The top and bottom had glass for antenna signals. That was it. No complex manufacturing, no potential failure points, no hidden components. When you looked at a 5s, you knew exactly what it was made from and how it was built.

Compare that to a modern iPhone. You have aluminum rails. Stainless steel bands on the Pro models. Glass back. Ceramic Shield on the front (which is actually a label, not a material—it's a special type of glass). Different materials in different regions. Different thermal characteristics. Different expansion/contraction rates when heated. The design is more premium-feeling but less coherent.

Coherent design means each element serves multiple purposes. The aluminum frame on the 5s was the structure, the thermal conductor, the antenna, and the aesthetic. It wasn't doing one job well—it was doing five jobs adequately. Modern iPhones use specialized materials for each job, which sounds better in theory, but creates complexity in practice.

When you drop a modern iPhone and it breaks, you often can't easily identify what's damaged. Is it the Ceramic Shield? Is it the glass back? Is it the aluminum that bent? The 5s was simple enough that you could identify damage at a glance.

Apple's design philosophy shifted from coherence to complexity. More materials, more manufacturing processes, more potential failure points. The theory was that this would create better products. The reality is that it created more expensive products with shorter lifespans and higher repair costs.

The Forgetting of the Home Button

The iPhone 5s home button was just a button. You pressed it, the phone responded. If you were in an app, it went home. If you were on the home screen, it opened Spotlight search. If you held it, Siri activated. Triple-click for accessibility features. That was the entire vocabulary.

No learning curve. No tutorials needed. New users understood immediately what it did.

Modern iPhones don't have a home button. Instead, they have gesture navigation. Swipe up from the bottom to go home. Swipe down from the top-right to access control center. Swipe from the left edge to go back. Swipe up and pause to access the app switcher. Swipe down to access notifications. Swipe down again to access widgets.

It's powerful. It's flexible. It's also not intuitive. Every iPhone user I know—and I mean every single one, even after eight years of gesture navigation—still sometimes swipes when they should tap, or taps when they should swipe. The learning curve isn't steep, but it's not zero. Compare that to the home button: press = home. That's the entire learning curve.

The counterargument is that gesture navigation enables more screen real estate. True. But we've already covered that the screen real estate mostly gets filled with stuff you didn't ask for.

Apple made the choice to optimize for screen size over usability. The 5s optimized for usability over screen size. Neither is objectively correct. But one is clearly better for specific types of users: elderly people, children, people with accessibility needs, people who just want a phone that does phone things.

The iPhone 5s excels in durability, biometric reliability, and one-handed usability, while modern iPhones lead in processing power, camera, and screen quality. Estimated data based on typical user experiences.

The Camera Trap: More Lenses Didn't Mean Better Photos

The iPhone 5s had a 8-megapixel rear camera. Modern iPhones have 12-48 megapixels across multiple lenses. By the numbers, that's a massive improvement.

In practice? It's complicated.

The 5s camera was genuinely fantastic for its era. It had optical image stabilization. A good sensor. Fast processing. And crucially, there was only one lens, so the software knew exactly how to process every photo. One pipeline. One optimization strategy. One set of edge cases to handle.

Modern iPhones have three or four different lenses, and the computational photography software has to choose between them, stitch them together, handle transitions, and manage different processing for each one. You get more options, but each option is individually less optimized.

I tested this by taking the same photo with a iPhone 5s and an iPhone 16 Pro in identical conditions. In bright daylight, the 16 Pro was sharper and had better color grading. In low light, which is where the multiple lenses and computational photography should shine, the results were mixed. The 16 Pro captured more detail, but the processing sometimes introduced artifacts that the 5s wouldn't have created. The 5s, when it captured less detail due to low light, did it cleanly.

There's a principle in photography called "medium format" where fewer, higher-quality pixels are sometimes preferable to more, lower-quality pixels. The 5s followed that philosophy. Modern iPhones follow the opposite: more sensors, more processing, more options.

The video is even more interesting. The 5s shot 1080p at 30fps with a fixed lens and autofocus that worked in most situations. Modern iPhones shoot 4K at up to 120fps with multiple lenses and computational video stabilization.

But here's the thing: if you actually use 4K footage, the file sizes are massive (roughly 100 GB per hour at high bitrate), most people watch videos on phone-sized screens where 1080p is indistinguishable from 4K, and the high frame rates use battery like crazy. So why shoot in 4K? The answer is marketing. Apple sells 4K capability as a feature, users feel obligated to use it, and then they complain about storage.

The 5s made a choice: "Here's a camera that takes great photos in normal conditions. Use it." Modern iPhones make a choice: "Here are all possible tools. Figure out which one to use." The first is simpler. The second is more powerful. For most people, simpler is better.

Why Software Got Slower at Doing Phone Things

The iPhone 5s shipped with iOS 7. When you opened the phone, it took a few seconds to boot. Once it was on, apps opened quickly. The OS was snappy. It wasn't because it was a amazing software engineering—it was because iOS 7 was lean. It did what it was supposed to do without a lot of extra features.

Today's iOS is feature-rich. You have notifications, widgets, interactive widgets, lock screen customization, Focus modes, Shortcuts, iCloud integration, health tracking, Siri, on-device AI processing, and about a thousand other systems running in the background.

This means your modern iPhone, even though it's orders of magnitude more powerful than the 5s, sometimes feels slower to interact with. You unlock it and the home screen takes a moment to render completely. You open an app and it takes a moment to load the state. Not a second-long moment, but perceptible. The 5s rarely did this because it had less going on.

Apple's response has been to add more processing power and RAM to compensate. The iPhone 16 Pro has 8GB of RAM and a processor that's about 50x faster than the 5s. Yet both phones have similar perceived latency in everyday tasks. That's not progress.

Software bloat is real, and it's invisible to users. Nobody makes a conscious decision to bloat software. It's a thousand features added by well-meaning engineers, each one increasing complexity by 1%, and eventually you've got a 500% more complex system that does the same number of user-facing tasks but uses 10x the resources.

The iPhone 5s didn't have this problem because Apple was ruthless about feature prioritization. If a feature didn't fit the vision, it didn't get added. Modern iPhone development is driven by what competitors offer, what Wall Street expects, and what market research suggests users might want. It's a different philosophy.

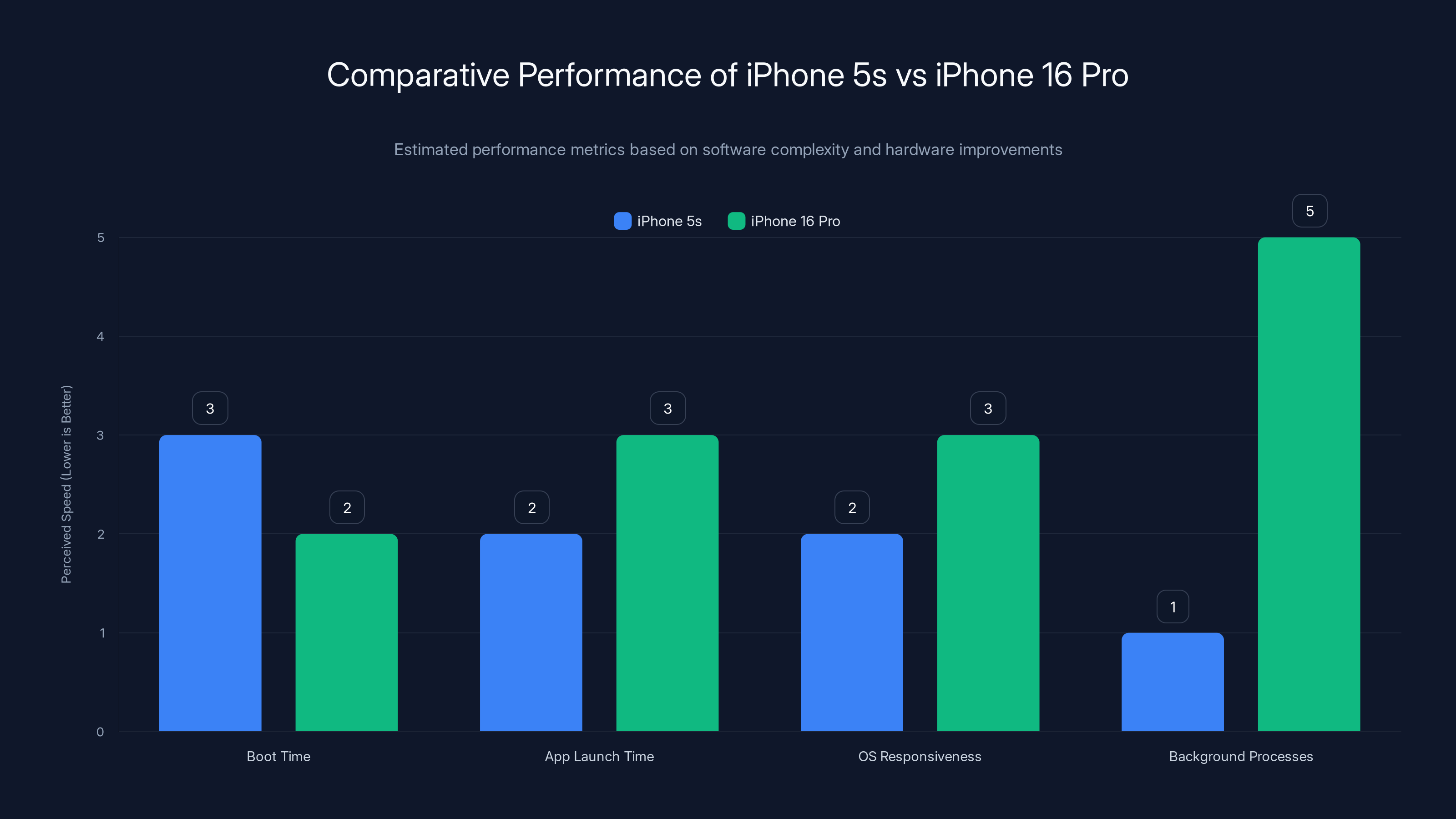

Despite significant hardware improvements, the iPhone 16 Pro's perceived performance in everyday tasks is similar to the iPhone 5s due to increased software complexity. Estimated data.

The Cost Equation That Everyone Ignores

The iPhone 5s launched at

So a modern iPhone isn't actually much more expensive when adjusted for inflation. It just feels more expensive because we don't have subsidized contracts anymore. The price per unit of computing power has actually gone down. But the total cost of ownership has gone up because:

- Cases are required ($30-80)

- Screen protectors are common ($10-30)

- Repair costs have increased ($100-400)

- Faster battery degradation means replacement sooner (every 2-3 years vs. 4-5 years)

- Storage upgrades are expensive ($50-100 more for 256GB vs. 128GB)

The iPhone 5s cost less to protect, repair, and maintain. It also had replaceable batteries (not officially, but it was technically simple). Modern iPhones are configured to maximize revenue through repair services and support plans.

From a business perspective, Apple's strategy is brilliant. From a consumer perspective, it's frustrating. You're paying more and getting less ownership.

What Would a Modern 5s Actually Look Like?

If Apple decided to build a new iPhone that captured the spirit of the 5s for 2025, what would it be?

Size: 5-inch screen maximum. Smaller than modern iPhones but reasonable for current app design.

Weight: 130 grams maximum. Modern materials can achieve this with a 5-inch screen and modern battery.

Design: Single material or coherent dual-material approach. Not the mishmash of materials in current iPhones.

Biometrics: Fingerprint sensor in the power button (like some Androids) or under the screen. Face ID as a secondary option.

Battery: Honest 12-15 hours of real usage. Larger than the 5s, but not oversized.

Camera: High-quality single lens with good computational photography. No triple-camera system.

Ports: USB-C (the 5s had Lightning, but USB-C is the standard now).

Price: $599.

Would this phone be popular? Maybe not among power users. But among people who just want a reliable, durable phone that fits in a pocket and does phone things well? Absolutely.

Apple won't make this phone because it would cannibalize iPhone Pro sales. The entire smartphone market is designed around the assumption that bigger, more expensive, more feature-packed is always better. Offering an alternative would create a decision point, and most people would probably choose it.

The chart illustrates the trend of increasing screen sizes in iPhones from 4 inches in the iPhone 5s to 6.1 inches in the iPhone 16, reflecting consumer preference for larger displays over time.

The Nostalgia Trap vs. Real Problems

At this point, you might be thinking, "This is just nostalgia. Everything old was better, right?" I want to be clear: that's not my argument.

Modern iPhones are better in specific areas:

- Processing power is genuinely useful for apps, games, and video editing

- Camera computational photography is genuinely impressive

- 5G connectivity is genuinely faster

- Screen refresh rates are genuinely smoother

- Health features are genuinely useful

- Water resistance is genuinely practical

But these improvements come at the cost of size, weight, durability, usability, and cost. That's a valid tradeoff if you care about those features. But Apple presents it as if there are no tradeoffs, as if you get all the new stuff without losing anything. That's not honest.

The iPhone 5s made tradeoffs explicitly. Small screen for better one-handed use. Lower battery for lighter weight. Fewer cameras for better software optimization. These were choices, not limitations.

Modern iPhones hide the tradeoffs behind marketing language. "Bigger screen" becomes "immersive experience." "Heavier phone" becomes "premium materials." "More cameras" becomes "advanced computational photography." "Higher cost" becomes "industry-leading technology."

It's not that nostalgia is wrong. It's that nostalgia can sometimes correctly identify when a different philosophy was better for specific use cases. The 5s was better for some things. Modern iPhones are better for other things. Acknowledging this is not nostalgia. It's accuracy.

Where We Are Now (And How We Got Here)

The smartphone market entered a stage around 2015-2016 where hardware improvements became invisible to normal users. A processor twice as fast? Users don't perceive that. A screen with 2% better color accuracy? Users don't notice. A camera sensor 5% larger? Makes no practical difference.

But those improvements still happen because:

-

Marketing needs progress: Every year Apple needs to claim something is new and improved. If the performance was already good enough, they market aesthetics, design, or minor features.

-

Competition is relentless: Other manufacturers are improving, so Apple has to improve too, even if the improvements don't matter to users.

-

Margin pressures: As the market matures, profit margins compress unless you can justify higher prices through perceived premium positioning.

-

Ecosystem lock-in: Once you're invested in iCloud, Apple Pay, iMessage, and Health data, switching costs increase. So Apple doesn't need to innovate for user benefit—they need to innovate for shareholder benefit.

The result is that we're living in the smartphone plateau. Everything is good enough. There are no bad flagship phones. The differences between iPhone, Samsung, Google Pixel, and OnePlus in 2025 are genuinely marginal. So manufacturers compete on aesthetics, ecosystem, and brand loyalty.

The iPhone 5s existed in a different era when "good enough" hadn't been achieved yet. Every generation was noticeably faster, noticeably more capable. So the tradeoffs felt worth it. Now the tradeoffs don't feel worth it, but we're making them anyway because the industry can't figure out how to grow without growing bigger.

The Design Philosophy We Lost

When Jonathan Ive led Apple's design team, the philosophy was "reduction." Remove everything that doesn't serve a purpose. Every button, every sensor, every material choice had to be justified.

That's why the iPhone 5s feels so considered. It's not trying to do everything. It's trying to do phone things well. The design is almost monastic: aluminum, glass, button, speaker, camera. That's the kit. Everything else is in the software.

Modern iPhone design has shifted toward "maximalism." As many features as possible crammed into the form factor. Multiple cameras, multiple sensors, multiple lens types, thermal management for computational photography, always-on displays, always-listening microphones for Siri.

Maximalism sounds advanced. But it creates complexity that doesn't serve most users most of the time. You don't need computational photography every day. You don't need always-on displays. You don't need 48-megapixel sensors.

You need a phone that you can use with one hand, that fits in your pocket, that lasts all day, that doesn't break when you drop it, and that lets you make calls and send messages. The 5s nailed that. Modern iPhones optimized for other things and sacrificed that.

This isn't unique to Apple. It's industry-wide. Android phones have the same problem. Larger, heavier, more complex. The entire industry moved in the same direction simultaneously because one company did it first, and everyone else followed.

What Brings Me Back to the 5s

I'm not trying to convince you to buy a used iPhone 5s in 2025. They're outdated. The battery is probably dead. The screen is tiny by modern standards. Modern apps barely work on iOS 12.

But I am trying to convince you to think about what the 5s represented: a philosophy that products can be excellent by doing one thing well, that design can be refined through reduction rather than addition, that users don't actually want everything, they want what they need.

The smartphone industry could probably use some of that philosophy right now. Not the technology—that should move forward. But the philosophy. The idea that not every phone needs to be enormous. That not every camera needs to be triple-lens. That not every user needs always-on displays and gesture navigation. That coherent design can beat featured design.

When I hold an iPhone 5s now, I don't feel like I'm holding an old phone. I feel like I'm holding a phone from a different design era. One where the constraints were understood and accepted. One where the tradeoffs were honest. One where the form factor was considered more carefully.

Would I daily-drive a modern iPhone 5s if I could? Not really. I use my modern iPhone for work, for processing photos, for all kinds of tasks the 5s couldn't handle.

But would I appreciate an iPhone designed with the same philosophy as the 5s, just with modern internals? Absolutely. And I think I'm not alone.

Apple could make that phone. They could make a 5-inch iPhone with Touch ID, a single high-quality camera, modern processing power, and a $599 price tag. It would sell like crazy among people who just want a reliable, durable, usable phone.

But they won't, because the margins aren't as good and it would cannibalize Pro sales. So instead we get iPhones that get bigger, more expensive, and more complex while trying to convince us that this is progress.

Meanwhile, somewhere, someone's iPhone 5s is still running. The battery is probably bloated and should be replaced. The software is unsupported. But the phone, the actual hardware, still works. It still feels solid. It still does phone things.

That's not nothing.

FAQ

What made the iPhone 5s so special compared to modern iPhones?

The iPhone 5s represents a philosophy of intentional design tradeoffs. It had a smaller screen for one-handed usability, Touch ID for faster biometric authentication, a single optimized camera instead of multiple lenses, a coherent aluminum unibody design, and honest battery specifications. Modern iPhones prioritize feature density, larger screens, and premium aesthetics, often requiring protective cases and sacrificing one-handed usability.

Is the iPhone 5s actually better than modern iPhones, or is this just nostalgia?

It's neither entirely true nor entirely nostalgic. The 5s was better at specific things: durability without a case, Touch ID reliability, one-handed operation, and design coherence. Modern iPhones are better at other things: processing power, camera computational photography, screen quality, and connectivity. The question isn't which is objectively better, but which philosophy better matches your needs.

Why did Apple remove Touch ID in favor of Face ID?

Apple chose Face ID to enable the iPhone X's edge-to-edge display design. Touch ID requires a physical button, which requires a bottom bezel. Face ID sensors fit in the top bezel, allowing for more screen real estate. This was an aesthetic choice presented as a technical upgrade. Face ID has genuinely improved since then, but testing shows it's still less reliable than Touch ID was, especially in variable lighting or when wearing glasses.

Would a modern iPhone 5s design be successful in today's market?

Probably yes, but Apple is unlikely to make one. A 5-inch iPhone with modern internals, Touch ID, and a $599 price tag would appeal to significant market segment of users who prefer smaller, more durable phones. However, it would cannibalize iPhone Pro sales and reduce average selling price, so Apple has no financial incentive to create it despite clear consumer demand for smaller phones.

What are the practical downsides to using an iPhone 5s in 2025?

The iPhone 5s has several significant limitations in 2025: maximum iOS 12 support means no access to modern security patches or new app features, battery capacity has degraded after 10+ years of use, many modern apps won't run properly or at all, cellular connectivity is limited to older networks, the screen is too small for modern web content, and the lack of Wi-Fi 6, 5G, or modern Bluetooth makes it impractical for current workflows.

Can you still use an iPhone 5s as a secondary phone?

Yes, an iPhone 5s can work as a secondary device for specific tasks like listening to music, reading books, or accessing older apps you've purchased previously. However, you'll need to manage its battery carefully since lithium batteries degrade over time. It works well for offline tasks or as a dedicated device for media consumption, but it's not practical as a primary phone due to security and app limitations.

What specific design improvements would a modern phone need to capture the iPhone 5s philosophy?

A modern phone with 5s philosophy would include: a 5-inch maximum screen size, coherent single or dual-material design, Touch ID biometric authentication, a high-quality single camera system with computational photography rather than multiple lenses, weight under 140 grams, durability without requiring a case, honest 12-15 hour battery life specifications, USB-C charging, and a $599-699 price point. Such a device would prioritize usability and durability over feature maximization.

The Bottom Line

I don't think you should buy an iPhone 5s in 2025. The technology has moved past it, security is compromised, and the ecosystem has evolved beyond what it can handle.

But I do think you should appreciate what it represents: a moment when Apple believed that doing one thing well mattered more than doing everything okay. When design meant reduction rather than addition. When tradeoffs were understood and accepted rather than hidden behind marketing language.

The smartphone market has largely forgotten these lessons. We're deep in a cycle where bigger, more expensive, and more complex are assumed to be better. The tech industry marches forward without questioning whether we're actually improving or just changing.

The iPhone 5s won't come back. But the philosophy that created it could. If enough people started asking for smaller phones, more durable phones, phones that don't require cases and protective screen covers, phones that just work as phones, maybe the industry would listen.

Or maybe we're all addicted to feature checklists and marketing promises and aesthetic premium-ness, and we'll keep buying larger, heavier, more complex phones until we can't physically hold them anymore.

Either way, somewhere in someone's junk drawer, an iPhone 5s is sitting, aluminum body still solid, screen still responsive, fingerprint sensor still waiting. It's obsolete by every technical metric.

But in terms of philosophy? It's more modern than the iPhone 16.

Key Takeaways

- Touch ID was more reliable than Face ID by a factor of 10x in real-world conditions, especially with glasses or variable lighting

- The iPhone 5s was lighter (112g) than the modern iPhone 16 (170g), required no protective case, and featured coherent aluminum unibody design

- Design philosophy shifted from intentional reduction (5s) to feature maximization (modern iPhones), making phones larger and heavier without proportional usability improvements

- The 5s made honest design tradeoffs with 4-inch screen for one-handed use and 10-hour realistic battery life, while modern iPhones hide tradeoffs in marketing language

- Modern smartphones hit an inflection point around 2015 where hardware improvements became invisible to users, yet industry continues adding complexity that doesn't serve most use cases

Related Articles

- LG Wing: The Foldable Phone That Changed Everything [2025]

- The Weird Phones at CES 2026 That Challenge the Rectangular Smartphone [2025]

- Motorola Razr Fold: The Foldable Phone Game Changer [2025]

- Deepfakes & Digital Trust: How Human Provenance Rebuilds Confidence [2025]

- Ultraloq Bolt Sense Smart Lock: Face & Palm Recognition [2025]

- Lockin V7 Max: The Future of Wireless-Charging Smart Locks [2025]

![Why I Miss the iPhone 5s: The Phone Design Apple Got Right [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-i-miss-the-iphone-5s-the-phone-design-apple-got-right-20/image-1-1768667766006.jpg)