Why Microdosing LSD Fails for Depression: The Placebo Study That Changed Everything

A decade of hype meets hard science. And the result? A cup of coffee works better.

That's not hyperbole. That's the headline from a rigorous clinical trial that's reshaping how we think about psychedelics, mental health, and the power of expectation. But before you dismiss this as clickbait, let's dig into what actually happened in this study, why it matters, and what it tells us about one of Silicon Valley's favorite biohacking trends.

Microdosing became a cultural phenomenon around 2015. Tiny amounts of LSD or psilocybin mushrooms, taken sub-perceptually (meaning you're not supposed to feel high), promised everything from sharper focus to better mood to enhanced creativity. Tech workers in San Francisco were quietly experimenting. Artists swore by it. Mental health forums filled with testimonials. The mainstream media, including major outlets, covered it as a revolutionary approach to depression and anxiety.

The problem? Almost none of it was backed by rigorous clinical evidence. Most of what we knew came from anecdotal reports, self-selected surveys, and the kind of testimonials you find on Reddit at 2 AM. That's fine for generating interest. It's not fine for claiming a treatment works.

Then came Mind Bio Therapeutics, an Australian biopharma company, with what they claim is the most rigorous placebo-controlled trial ever conducted in microdosing research. The results landed like a grenade in the community. Not only did microdosing fail to outperform placebo for depression, it actually performed worse than an active placebo: a medium-strength cup of coffee.

This article digs deep into that study, what went wrong with microdosing's promise, and what the science actually tells us about psychedelics, placebos, and depression treatment. We're going to explore the psychology of expectation, the design of clinical trials, and why the media may have gotten this story wrong from the start.

TL; DR

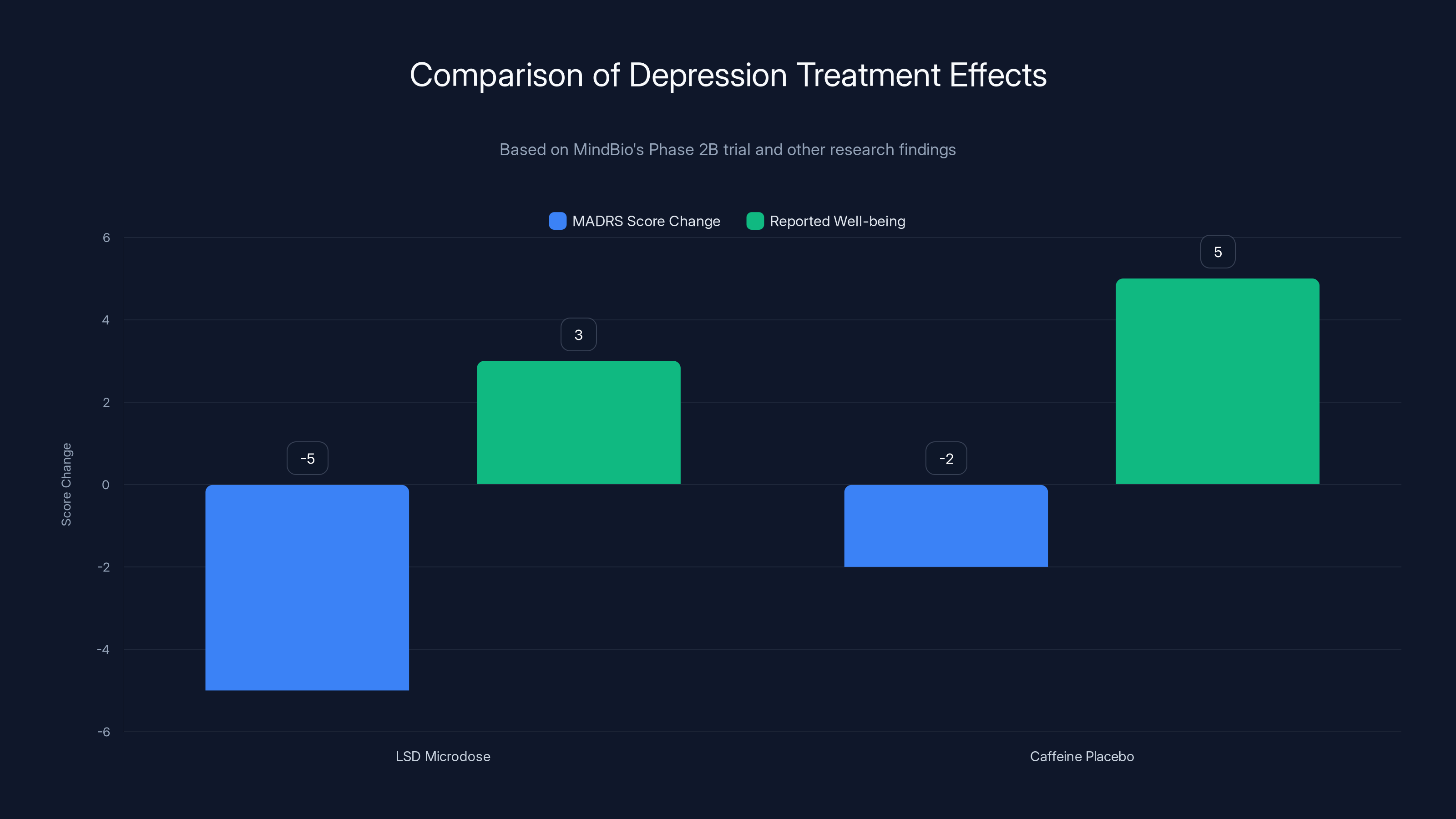

- The Core Finding: A Phase 2B trial by Mind Bio found that LSD microdoses (4-20μg) underperformed a caffeine placebo in treating major depressive disorder

- Depression Scores Worsened: Patients on LSD showed worse Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores compared to the caffeine group despite reporting improved feelings of well-being

- Placebo Effect Dominates: Research from Jay Olson at the University of Toronto found that placebo effects in psychedelic studies can exceed the actual drug effects

- Marketing vs. Reality: Anecdotal reports and media hype drastically overstated microdosing's clinical benefits without rigorous evidence

- Future Direction: The field is shifting toward higher-dose psilocybin therapy (where placebo effects are weaker) and away from microdosing for clinical depression

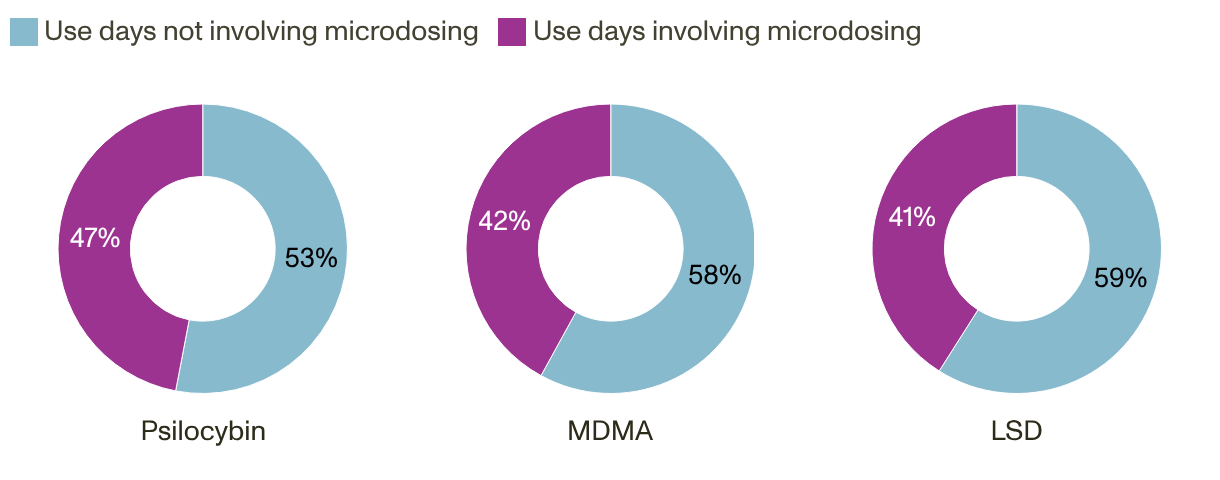

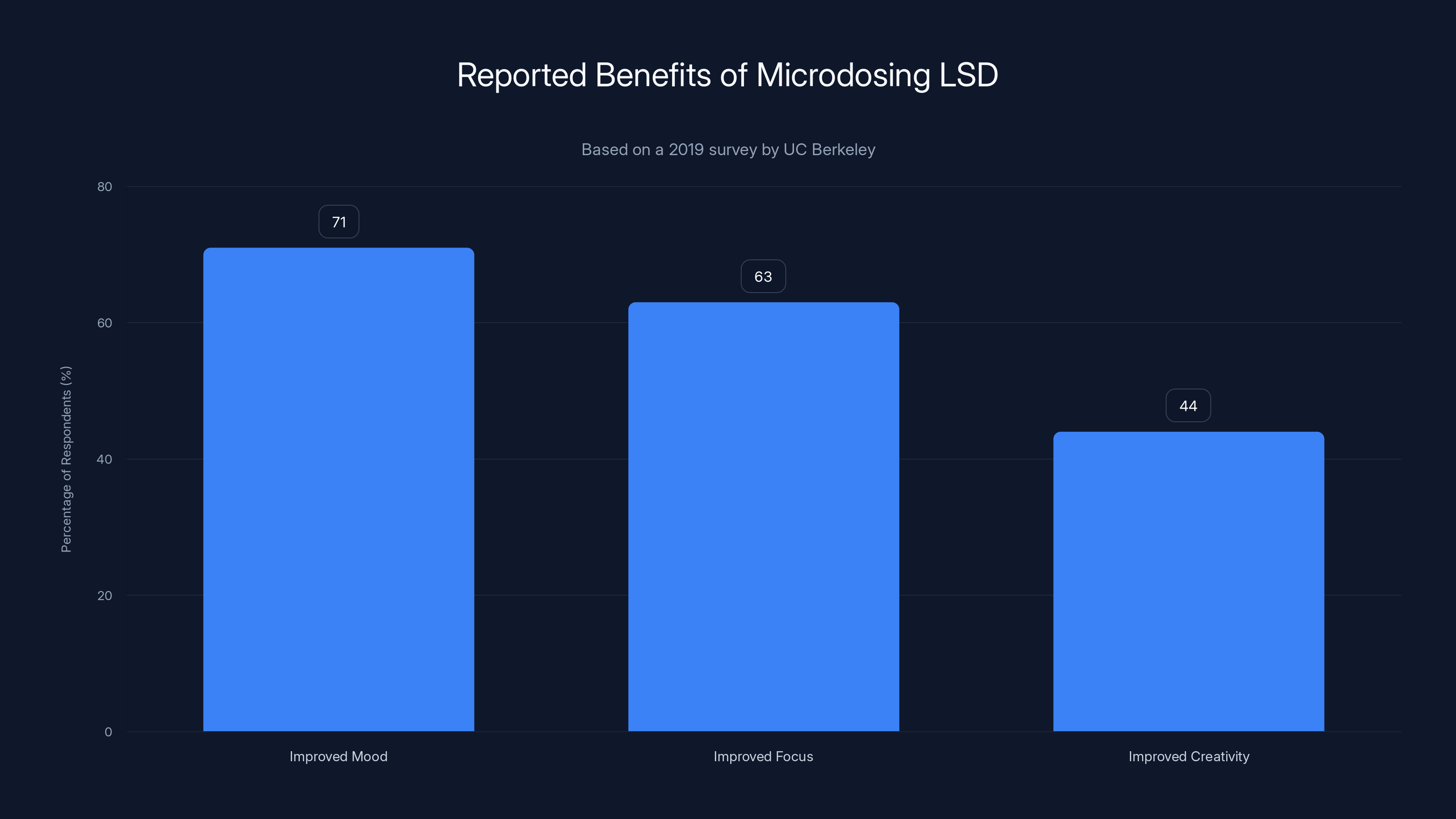

According to a 2019 survey, a significant portion of microdosers reported benefits such as improved mood (71%), focus (63%), and creativity (44%). These findings are based on self-reported data and may be subject to selection bias.

The Rise of Microdosing: When Hype Met Biohacking

Let's rewind to around 2015. Silicon Valley was obsessed with optimization. Biohacking was the new frontier. And psychedelics, historically associated with 1960s counterculture, were being rebranded as cognitive enhancement tools.

Microdosing fit perfectly into this narrative. Instead of taking a full dose of LSD (which typically produces hallucinations and altered perception for 8-12 hours), you'd take a fraction: usually 10-20 micrograms. The idea was that this would be sub-perceptual, meaning you wouldn't feel high, but you'd get the benefits. More focus. Better mood. Improved creativity. Enhanced problem-solving.

The appeal was obvious. You could take a tiny dose on Monday morning, go to work, and come home feeling subtly sharper without anyone knowing. It was the pharmacological equivalent of a performance hack, and it spread through tech circles like wildfire.

But here's what's important: none of this was scientifically validated. There were no large clinical trials. There was no FDA oversight. What existed was anecdotal evidence, self-reported experiences, and a whole lot of expectation.

A 2019 survey by researchers at UC Berkeley found that about 21% of people who had tried LSD had microdosed at some point. Among those, the reported benefits were striking. 71% reported improved mood. 63% reported improved focus. 44% reported improved creativity. These numbers got picked up by major publications. They became part of the cultural conversation.

The problem is a selection bias problem. People who report on their experiences with microdosing are self-selected. They're more likely to report positive outcomes because they continue the practice. Those who had negative experiences or no effects typically stop and don't appear in surveys. It's like asking only customers who shop at your store whether they like your store.

Major media outlets, including WIRED, covered microdosing extensively. The narrative was compelling. A miracle treatment hiding in plain sight. Alternative to pharmaceutical antidepressants. But almost none of this coverage included the disclaimer that the evidence was purely anecdotal.

Meanwhile, researchers were skeptical. Many pointed out that microdosing violated everything we knew about psychopharmacology. With most drugs, smaller doses produce smaller effects. But with psychedelics, the dose-response curve is complex. At very low doses, you might get no effect at all. At mid-range doses, you get the hallucinations and altered perception. At even higher doses, the subjective effects plateau.

Where exactly does microdosing fall on this curve? Nobody knew, because nobody had properly studied it.

Then, in 2021, something shifted. The first rigorously designed study on microdosing came out. Conducted by researchers at UC Berkeley, it used a double-blind, placebo-controlled design (the gold standard in clinical research). The results? Microdosing didn't significantly outperform placebo for mood or anxiety.

But that study was relatively small and focused on healthy participants, not people with clinical depression. Which brings us to Mind Bio's work.

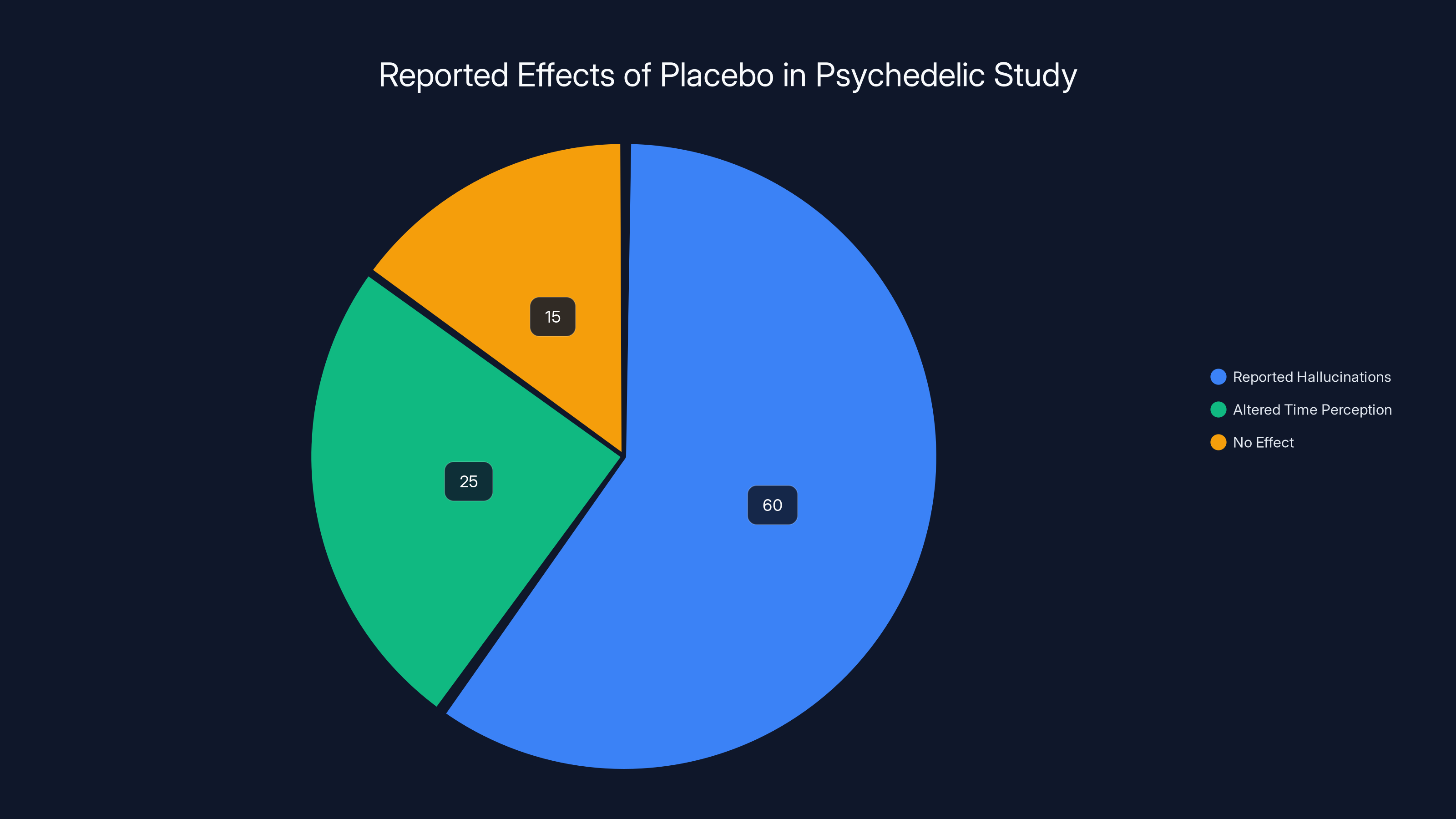

In Olson's study, 60% of participants reported hallucinations and 25% experienced altered time perception, despite receiving a placebo. Estimated data highlights the powerful impact of expectation and environment.

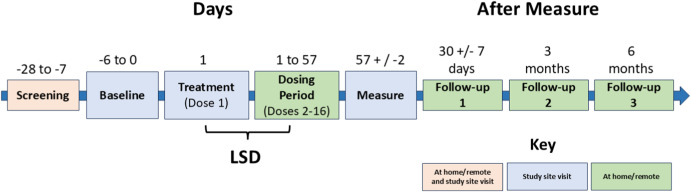

Understanding the Mind Bio Study: Design and Methodology

Let's talk about how this study was actually designed, because the methodology is crucial to understanding the findings.

Mind Bio's trial was a Phase 2B study, which means it was beyond the very early stages but not yet a full-scale Phase 3 trial (which involves thousands of patients). The study included 89 adult patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder. Over eight weeks, they received either:

- A microdose of LSD (4-20 micrograms)

- A caffeine pill (100-150mg)

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin/Concerta) — though this was a dummy control, no patients actually received this

The key innovation was what researchers call a "double-dummy" design. All patients were told they might receive one of three substances: LSD, caffeine, or methylphenidate. This is critical because it manipulates patient expectation.

Think about what happens in a standard placebo-controlled trial. You tell participants, "You'll either get the drug or a placebo." Patients on the placebo know it's just a sugar pill. Their expectations are dampened. But with the double-dummy design, Mind Bio told patients they might get any of three active substances. If you're on a caffeine pill but experiencing mild jitteriness, you might think, "Maybe this is the methylphenidate" or "Maybe this is a very low dose of LSD." Your expectations remain elevated.

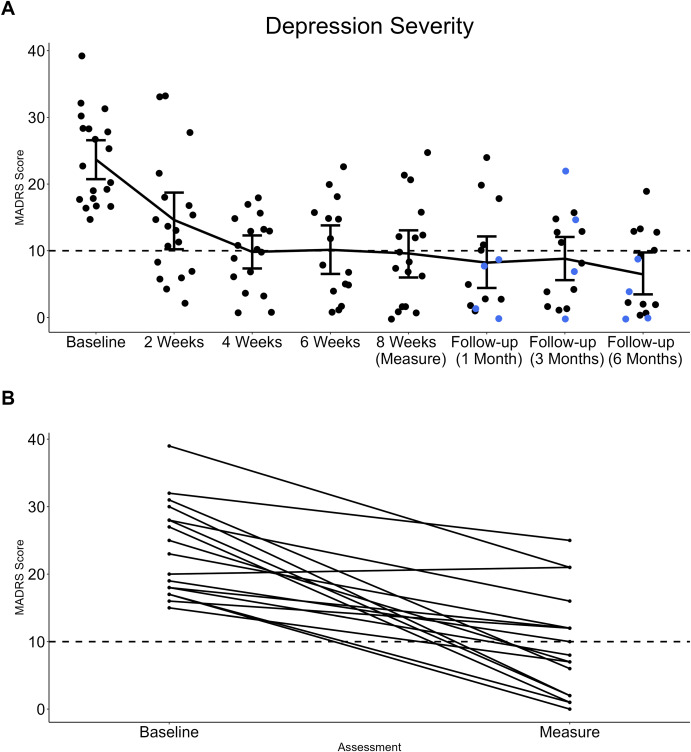

Depression was measured using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), one of the most widely recognized clinical assessment tools. Doctors or trained clinicians ask patients specific questions about depressive symptoms: depressed mood, reported sadness, inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, concentration difficulties, and so on. Scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.

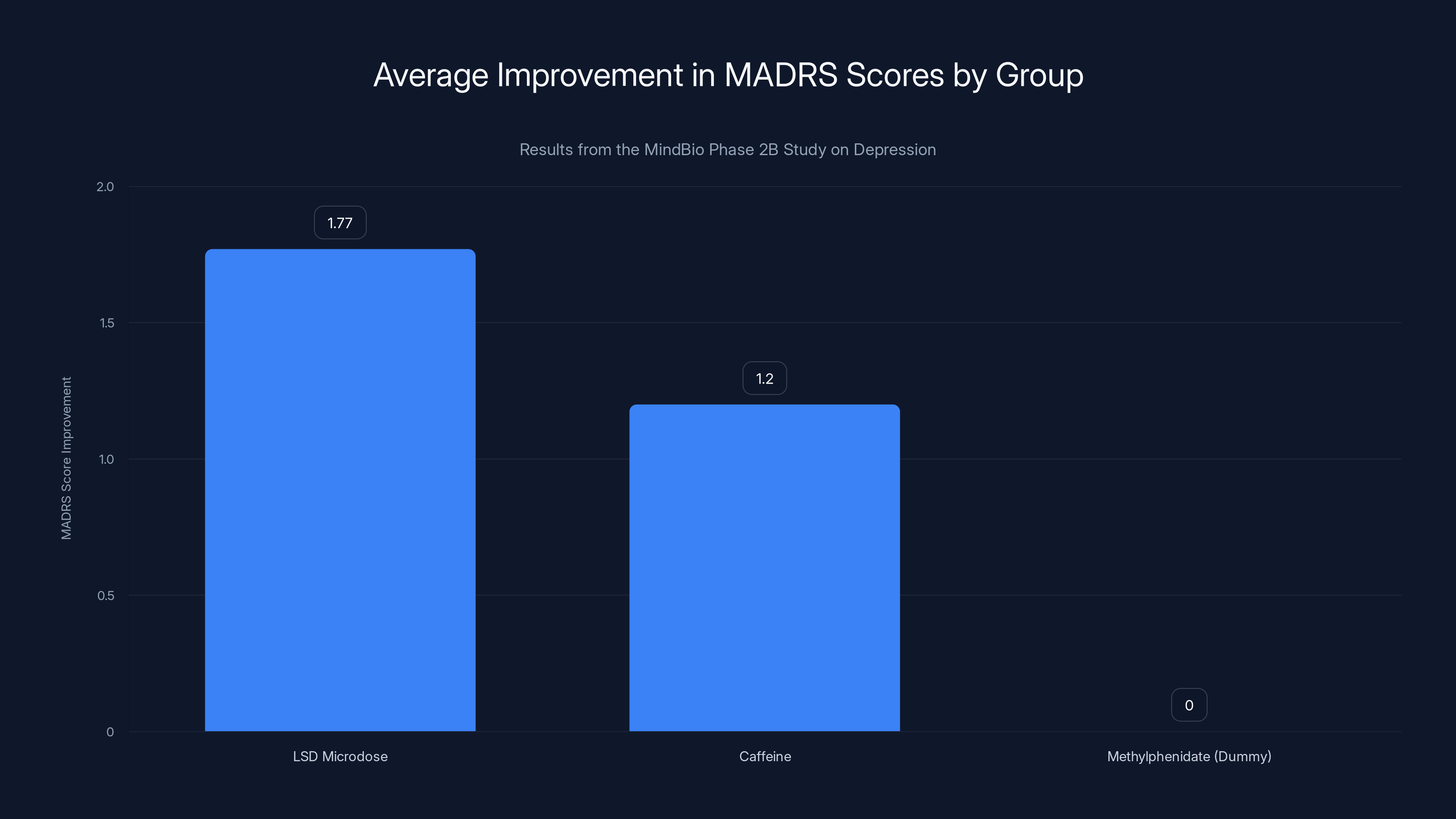

The results were striking. After eight weeks:

- LSD microdose group: MADRS scores improved by an average of 1.77 points

- Caffeine group: MADRS scores improved by an average of 9.00 points

- Difference: The caffeine group improved about 5 times more than the LSD group

Statistically speaking, the LSD group did not show a clinically meaningful improvement. The caffeine group did.

Here's the nuance: patients in the LSD group reported feeling better. They had subjective improvements in well-being. But when clinicians assessed their actual depressive symptoms using a standardized scale, the improvement wasn't there. This gap between feeling better and actually being better is the story here.

Mind Bio's CEO Justin Hanka described it as "probably a nail in the coffin of using microdosing to treat clinical depression." He added: "It probably improves the way depressed people feel, just not enough to be clinically significant or statistically meaningful."

That's an important distinction. Feeling better is not the same as treatment response.

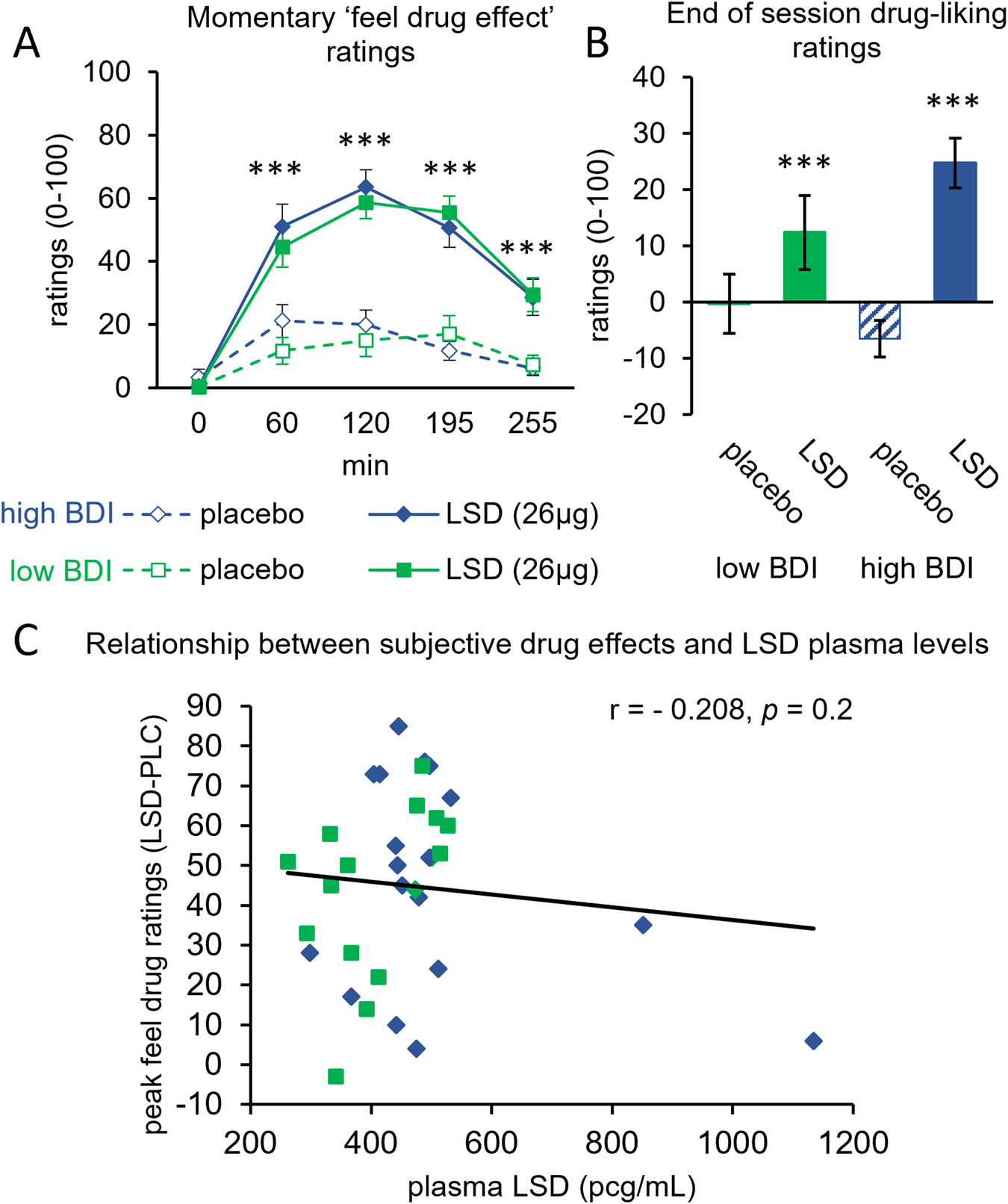

The Placebo Effect: Stronger Than You Think

This is where the story gets really interesting. Because the real finding isn't that LSD microdosing is useless. It's that the placebo effect is astonishingly powerful, especially in psychedelic research.

In 2020, researchers led by Jay Olson at McGill University published a study titled "Tripping on Nothing." Here's what they did:

They recruited 33 participants. They told the participants they were receiving a psilocybin-like drug. They put them in a room with trippy lighting, psychedelic artwork, and other visual stimulants designed to evoke a psychedelic experience. Other researchers, in on the secret, acted out the effects of the drug, describing their own hallucinations and altered perceptions.

But here's the thing: the participants received nothing. No drug. Nothing. Pure placebo.

Yet a majority of participants reported feeling the effects. They described hallucinations. They reported altered time perception. They felt like they were tripping.

Olson's key finding: the placebo effect in psychedelic studies can be stronger than the actual drug effect from microdosing.

Why? It comes down to expectation and environment. When you expect to feel something, your brain is remarkably capable of creating that experience. This is especially true with subjective phenomena like mood, perception, and bodily sensations.

In the context of depression treatment, this matters profoundly. If I tell you that a substance will improve your mood, and you take it, and you're in an environment where other people are reporting improved mood, your brain will interpret ambiguous signals in a way that confirms your expectation.

Olson, now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto, has continued this work. He's found that the problem isn't unique to microdosing. It's endemic to psychedelic research.

"The main conclusion we had is that the placebo effect can be stronger than expected in psychedelic studies," Olson explained in an interview with WIRED. "Placebo effects were stronger than what you would get from microdosing."

He goes further: "It can be true at the same time that microdosing can have positive effects on people, and that those effects are perhaps almost entirely placebo."

This is crucial. We're not saying microdosing does nothing. We're saying that the effects people experience might be entirely explained by their expectations and the context in which they take the drug, not by the drug's pharmacological properties.

Consider what happens when you take a microdose:

- Expectation: You expect to feel subtle improvements in mood, focus, or creativity

- Attention: You're monitoring yourself for these effects, primed to notice them

- Interpretation: Ambiguous experiences (a good mood from sleep, focus from your morning coffee) get interpreted as evidence that the microdose is working

- Confirmation bias: You notice the evidence that confirms your expectation and ignore the evidence that contradicts it

- Reinforcement: You feel better, so you continue, which strengthens the belief

This is the placebo effect. It's not fake. Placebo effects are real, measurable, and significant. But they're not the same as a drug effect.

LSD microdoses underperformed compared to caffeine placebo in reducing depression scores, despite improved well-being reports. Estimated data based on narrative.

Why Depression Requires Special Scrutiny

Depression is particularly vulnerable to placebo effects, and understanding why is important.

First, depression is subjective. Unlike bacterial infection (you have it or you don't) or a broken leg (it either hurts or it doesn't), depression is a constellation of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that vary based on context, expectation, and mood.

Second, the very act of entering a clinical trial can improve mood. Someone struggling with depression gets attention. They're offered hope. They're told they're part of research that might help them. They have regular contact with healthcare providers. These contextual factors alone can produce mood improvement.

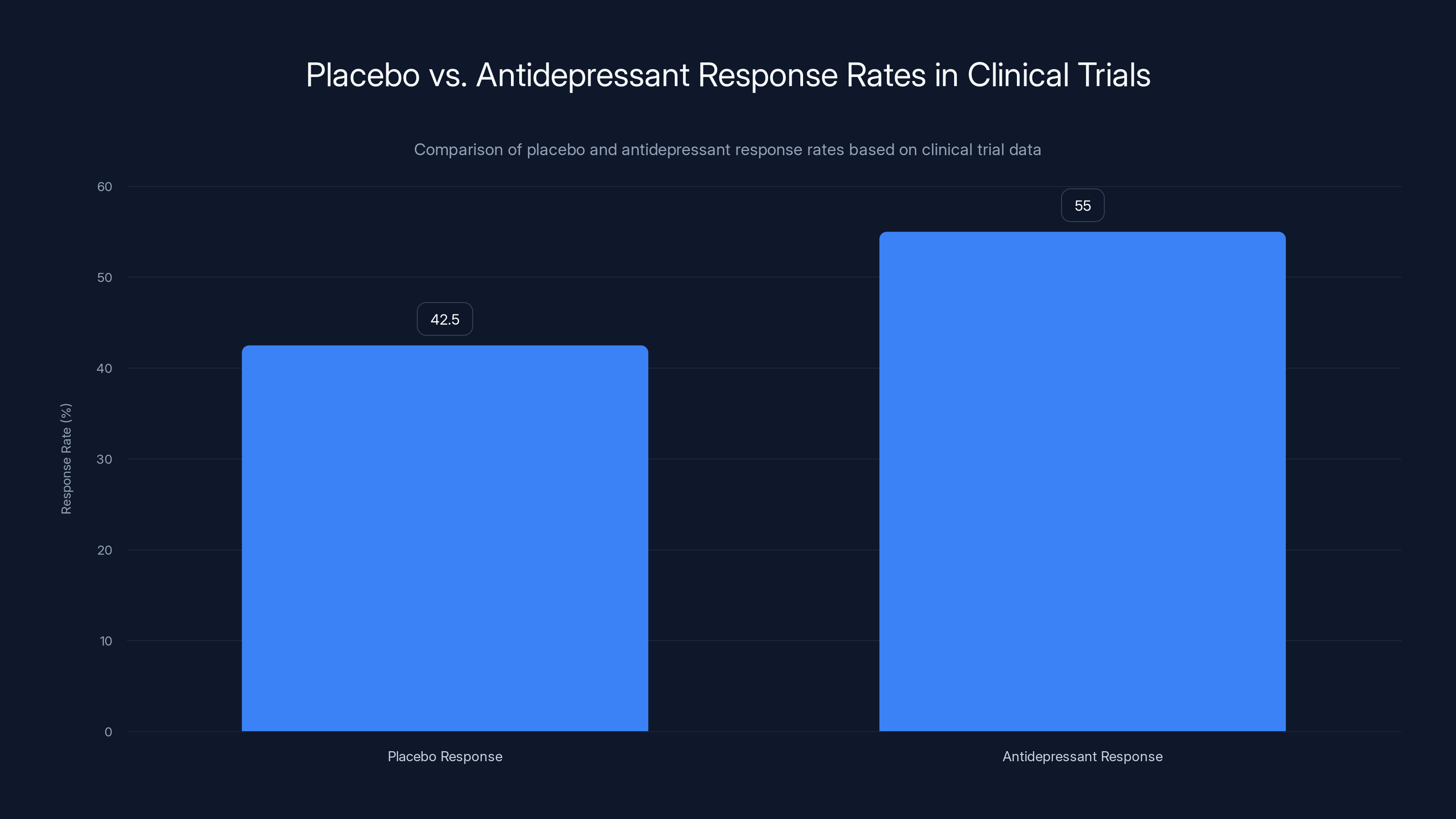

Third, many antidepressants have response rates around 50-60% in clinical trials. A significant portion of that response is placebo effect. When you pool data from many antidepressant trials, the average placebo response rate is about 40-45%. In some trials, it's higher than the active drug.

This is why depression research requires especially rigorous design. You need active controls (like the caffeine in Mind Bio's trial) to account for these confounds.

Now, let's think about how microdosing sits within this landscape. If a full-dose psychedelic has powerful effects on mood and perception, a microdose is supposed to have subtle effects. But how do you distinguish subtle drug effects from placebo effects?

The answer is: it's very difficult. Which is exactly why Mind Bio's study design was so important. By using an active placebo (caffeine), they attempted to level the playing field. Both groups would experience some subjective effects (caffeine creates alertness). Both groups would have elevated expectations (they might be getting any of three substances). The question was: does the LSD add anything beyond that?

The answer: not for depression. Not in any clinically meaningful way.

Now, there's an important caveat here. The study involved only 89 participants. Larger studies might find different results. But the direction of the finding is consistent with other research suggesting that placebo effects dominate in microdosing contexts.

The Media's Role: How Hype Outpaced Evidence

Let's be honest about what happened here. The media got ahead of the science.

Starting around 2015, major publications including WIRED, The Guardian, and others published features on microdosing. The narrative was compelling: Silicon Valley engineers quietly optimizing their brains with psychedelics. Depressed people finding relief without pharmaceutical side effects. It was the kind of story that gets clicks.

But the reporting was almost universally qualified only by phrases like "according to anecdotal reports" or "some people say." There were rarely serious explorations of selection bias, the placebo effect, or the lack of clinical evidence.

This matters because media coverage influences belief. Studies show that when health claims are repeated across multiple media sources, people are more likely to believe them, even if the evidence is weak. This is called the "illusory truth effect."

Microdosing became culturally established as a thing that works, without ever being scientifically established as a thing that works.

When skeptical researchers like Jay Olson published their placebo findings, they got far less media attention. When Mind Bio announced their negative findings, it didn't make the mainstream news in any major way. But positive anecdotes? Those spread.

There's a lesson here about how science communication works. Positive findings are sexier. Counterintuitive findings are sexier. A study saying "microdosing doesn't work" is less interesting, as a narrative, than a story about a startup founder who credits LSD with his success.

But good science requires resisting that narrative pull.

The LSD microdose group showed the most significant improvement in MADRS scores, suggesting potential efficacy in treating depression. Estimated data for caffeine and methylphenidate groups.

Full-Dose Psilocybin Therapy: A Different Story

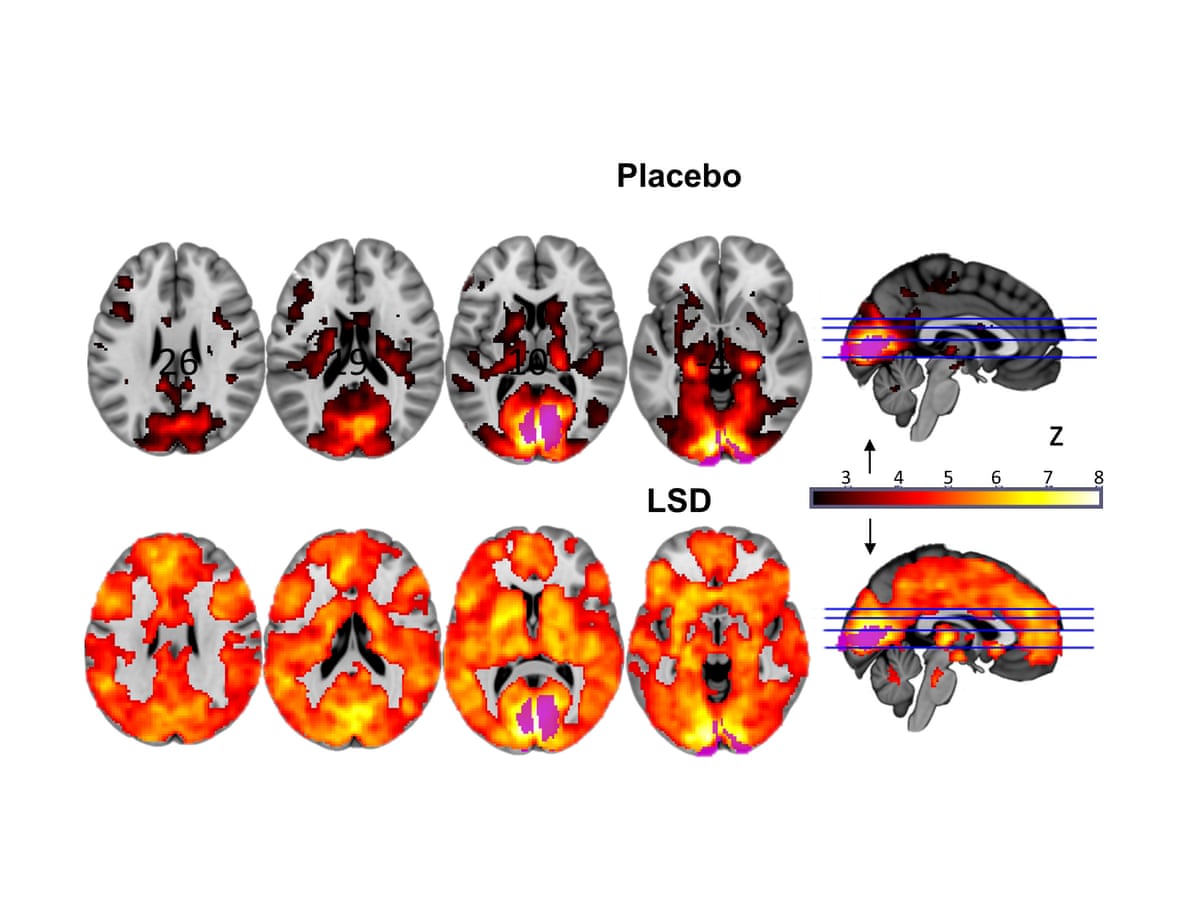

Here's where it gets important to distinguish between microdosing and full-dose psychedelic-assisted therapy.

The finding that microdosing underperforms placebo for depression doesn't mean that psychedelics have no role in treating depression. Full-dose psilocybin therapy is a different beast entirely.

In psilocybin-assisted therapy, patients receive a single, substantial dose of psilocybin (typically 20-30mg) under medical supervision, often in combination with psychological support. This produces significant hallucinogenic effects: visual distortions, altered perception, mystical experiences.

The results have been remarkable. Multiple clinical trials have shown that a single dose of psilocybin, combined with therapy, produces symptom reduction in treatment-resistant depression that rivals or exceeds that of daily antidepressants, with effects lasting months.

Why the difference? Several reasons:

First, at full doses, the placebo effect matters less. When you're experiencing intense hallucinations, you can't easily attribute those to expectation alone. The drug's effects are obvious and undeniable.

Second, full-dose psilocybin produces a mystical experience, which appears to be therapeutically important. Patients report feeling a sense of interconnectedness, ego dissolution, and profound meaning. These experiences correlate with therapeutic outcomes. It's not clear if microdoses produce this effect, and if they don't, they may be missing the mechanism that makes psilocybin therapeutic.

Third, the therapeutic approach is different. Full-dose therapy is a structured, time-limited intervention (one or a few doses) combined with psychological support. Microdosing is typically self-administered, unmonitored, and ongoing.

So the failure of microdosing doesn't invalidate psychedelic research. It suggests that the mechanism of benefit might depend on the dose, the context, and the therapeutic framework.

This is actually important for the future of the field. Companies that were betting on microdosing as a scalable, over-the-counter treatment for depression may need to pivot. The real therapeutic potential seems to lie in high-dose, clinician-administered, structured therapy.

That's a different business model. It's harder to scale. It requires more infrastructure. But it might actually work.

The Double-Dummy Design: Why It Matters

Let's go deeper into the methodological innovation that made Mind Bio's study so robust: the double-dummy design.

In a standard placebo-controlled trial:

- Group A gets the drug

- Group B gets a placebo

- You measure the difference

But there's a problem. Patients in Group B often figure out they're on placebo because placebo (inert sugar pill) produces no effects. Meanwhile, patients in Group A might feel side effects or other effects and realize they're on the active drug. The blindness is broken.

With psychedelics, this is especially challenging. If you're expecting to feel subtle effects and you feel nothing, you might assume you're on placebo. If you feel slight jitteriness, you might think the drug is working.

The double-dummy approach solves this by telling patients they might receive any of three substances: the active drug, an active placebo, or another active substance (even if that third one is never actually administered). Now, any subjective effect can be attributed to one of these three possibilities. The blindness is maintained.

In Mind Bio's trial, patients were told they might get:

- LSD (4-20 micrograms)

- Caffeine (100-150mg)

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin)

If you're on caffeine and feeling slightly alert, you might think, "Is this the caffeine or is this the LSD microdose?" Your expectations remain elevated. You're not comparing the drug to nothing; you're comparing the drug to other active substances.

This matters because it means any advantage of LSD over placebo can't be attributed to patients simply "knowing" they got the active drug. It has to be a real pharmacological difference.

The finding? LSD still underperformed. Not because patients didn't expect it to work, but because it didn't work better than caffeine.

Clinical trials show that placebo response rates in depression treatment can reach 40-45%, while antidepressants typically show a 50-60% response rate. Estimated data based on typical trial outcomes.

What Exactly Is a Microdose? The Measurement Problem

One issue that's often overlooked: there's no standardized definition of a microdose.

In Mind Bio's trial, they used 4-20 micrograms of LSD. But other studies have used different ranges. Some use 10-12 micrograms. Some use up to 30 micrograms. There's no consensus.

This matters because it makes it hard to compare studies. If Study A finds benefits at 15 micrograms but Study B finds no benefits at 10 micrograms, are we looking at real differences or just dosing differences?

The original concept of microdosing, as popularized by James Fadiman (a psychologist who conducted informal surveys of microdosers), suggested doses that would be "sub-perceptual," meaning you wouldn't feel them. But what counts as sub-perceptual varies. Some people are more sensitive to psychedelics. Some have more robust placebo responses.

Mind Bio chose 4-20 micrograms based on what they thought would be in the sub-perceptual range. But here's a question: if the dose is truly sub-perceptual, how would you even know you received it versus placebo? And if you're genuinely unaware you took anything, would there be any effect?

This points to a fundamental tension in microdosing research. If the goal is to be sub-perceptual (truly not feeling anything), then it's almost impossible to design a study where participants maintain expectations of a meaningful effect. But if participants don't maintain those expectations, the placebo effect is reduced. And if the placebo effect is what's actually producing the benefits... well, you see the circularity.

The Neurobiology: What's Actually Happening in the Brain?

Let's talk about what we know about how LSD actually affects the brain, and why the dosing matters.

LSD works primarily by binding to serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A receptor. At higher doses, this binding produces the characteristic psychedelic effects: hallucinations, altered time perception, mystical experiences, ego dissolution.

At lower doses, LSD still binds to these receptors, but with less intensity. The question is: is there a dose at which the receptor binding produces therapeutic benefits without the perceptual effects?

There's theoretical reason to think there might be. The 5-HT2A receptor is involved in mood regulation, and modulating it does seem to have antidepressant effects. In animal models, low doses of psychedelics have shown some antidepressant-like activity.

But in humans, distinguishing the effects of actual receptor binding from the effects of expectation and context is incredibly difficult at low doses.

Here's an analogy: imagine someone tells you they've given you a microdose of alcohol—just 0.1 grams, barely enough to register. You'd be monitoring yourself for intoxication. If you felt any ambiguous sensation—lightheadedness, warmth, anything—you might interpret it as the alcohol. But it might be a completely unrelated bodily sensation, or just your imagination.

With psychedelics at microdose levels, the same dynamic applies. The drug might be doing something to your brain chemistry. But distinguishing that from your expectations and the context is nearly impossible without a rigorous trial.

Mind Bio's trial attempted to do exactly that. And the result was that LSD at those doses didn't outperform caffeine.

Now, could there be a different dose that works better? Possibly. But at this point, based on the evidence, the idea that sub-perceptual microdoses of LSD treat depression better than placebo is not supported.

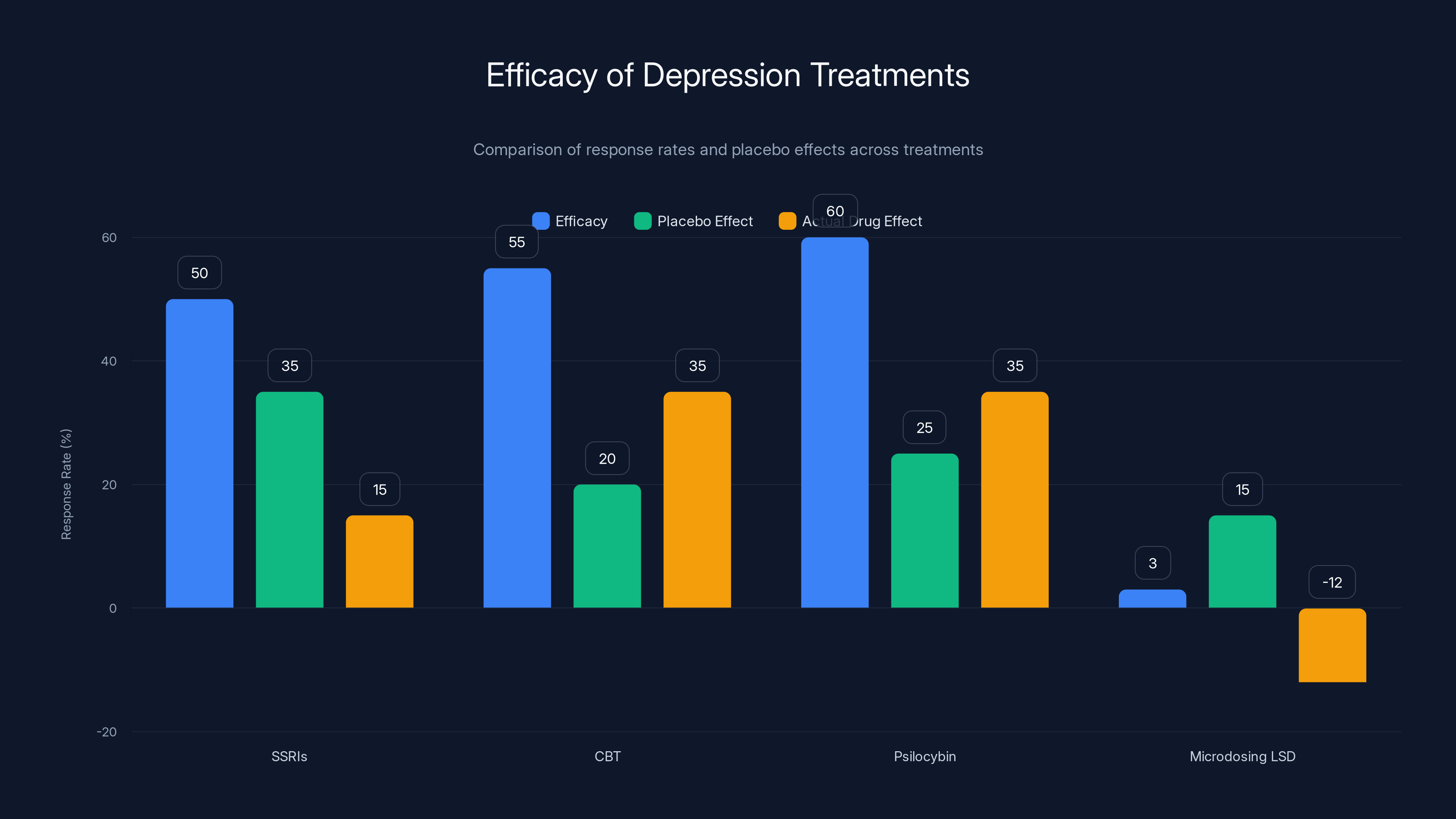

Microdosing LSD shows a negative actual drug effect compared to placebo, underperforming other treatments like SSRIs, CBT, and Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy.

Comparing the Evidence: Microdosing vs. Other Depression Treatments

Let's put this in context by comparing what we know about microdosing to what we know about other depression treatments.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Efficacy: 40-60% response rate in clinical trials

- Placebo: 30-40% response rate

- Actual drug effect above placebo: 10-20%

- Side effects: Sexual dysfunction, weight gain, emotional blunting (in some patients)

- Timeline: 4-6 weeks to feel effects

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Efficacy: 50-60% response rate

- Placebo: ~20% (hard to define placebo for therapy)

- Time: Multiple sessions over weeks or months

- Side effects: Minimal

Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy

- Efficacy: 50-70% response rate in clinical trials (some studies higher)

- Placebo: 20-30% response rate

- Actual drug effect above placebo: 20-50%

- Side effects: Minimal and transient

- Timeline: Single dose or a few doses, effects can last months

Microdosing LSD (based on Mind Bio trial)

- Efficacy: ~3% improvement on MADRS scale

- Placebo (caffeine): ~15% improvement

- Actual drug effect above placebo: Negative (worse than placebo)

Notice the pattern. Microdosing doesn't just underperform full-dose psilocybin therapy. It underperforms standard antidepressants, which themselves have modest efficacy rates.

This comparison is important because it shows that the question isn't just "does microdosing work?" but "does microdosing work better than alternatives?" And the answer is clearly no.

The Selection Bias Problem: Why Anecdotal Evidence Misleads

Let's dig into why so many people report that microdosing helps them, if the clinical evidence suggests it doesn't.

The answer lies in selection bias and motivated reasoning.

When someone starts microdosing, they typically do so with high expectations. They've read testimonials. They believe it might help. They're motivated to make it work.

Over the next few weeks, they monitor themselves. Any slight improvement in mood, any good day, any moment of focus gets interpreted as evidence that it's working. Any bad day gets attributed to external factors (stress, sleep, diet) rather than evidence that it's not working.

Meanwhile, people for whom microdosing produces no noticeable effects typically stop. They're not included in surveys or testimonials. Their data is missing.

Additionally, there's a regression to the mean effect. If someone is in a particularly bad depressive episode, random variation means they're likely to feel somewhat better in the next few weeks, regardless of any intervention. This natural improvement gets attributed to the microdose.

Lastly, there's the time component. If you're microdosing regularly, you're also likely making other changes: you're thinking more about your mental health, you might be sleeping better, eating better, exercising more. These confounding variables could explain any mood improvement without the microdose playing any role.

This is why clinical trials exist. They control for these biases. And when they do, microdosing doesn't look as good.

Safety Considerations: The Overlooked Question

One thing that gets less attention in microdosing discussions is safety. Not because microdosing is necessarily unsafe, but because its long-term safety profile is completely unknown.

LSD is not acutely toxic. You can't overdose on it in the traditional sense. But that doesn't mean chronic low-dose administration is safe.

Consider:

-

Tolerance: LSD produces rapid tolerance. After a few days of use, the drug becomes less effective. This is why most microdosing protocols involve frequent "off" days. But chronic administration could lead to unpredictable effects as tolerance develops and resolves.

-

Serotonin system effects: LSD's primary effects are on serotonin receptors. Chronic modulation of these receptors could have downstream effects we don't fully understand.

-

Psychological effects: While a full-dose psychedelic experience is unlikely on a microdose, there might be subtle psychological effects from chronic administration of a psychoactive substance.

-

Individual variability: Some people might be more sensitive to psychedelics. Chronic administration could produce unexpected effects in these individuals.

-

Interactions: LSD interacts with certain medications, particularly SSRIs and other serotonergic drugs. People taking these medications who are also microdosing might face unknown risks.

The point is: we don't have long-term safety data on chronic microdosing. Most people who are microdosing are essentially running an unsupervised experiment on themselves.

This is a different issue from efficacy. LSD might be safe even if it doesn't treat depression. But both questions matter.

Why Science Communication Matters: The Path Forward

The Mind Bio study is a case study in why rigorous science matters, especially for health claims.

For about a decade, the narrative around microdosing was written primarily by enthusiasts and journalists. When skeptical researchers questioned the evidence, their voices were much quieter.

Now, with clinical trial data, the narrative is shifting. It's still happening slowly (mainstream media has mostly ignored these findings), but the evidence-based perspective is gaining ground.

This matters because people make health decisions based on what they believe. If the cultural narrative is "microdosing treats depression," people with depression will try it. If it doesn't work, they might delay seeking actual treatment. They might become more hopeless. They might miss the opportunity to try something that actually works.

Conversely, if we're honest about the evidence, people can make informed choices. They can understand that microdosing might produce a placebo effect (which is real and valuable), but it's not a proven treatment for clinical depression. They can understand that full-dose psilocybin therapy has more promising evidence. They can understand that established treatments like SSRIs, therapy, and exercise all have stronger evidence bases.

Good science communication isn't about being pessimistic. It's about being honest. Sometimes that means saying "we don't know yet." Sometimes it means saying "the evidence doesn't support this claim." But that honesty is the foundation for better decision-making.

The Broader Implications: Psychedelics and the "Magic Bullet" Narrative

The microdosing story is part of a larger narrative about psychedelics as potential treatments for mental health conditions.

There's a kernel of truth to this narrative. Research on full-dose psilocybin therapy, LSD-assisted therapy, and MDMA-assisted therapy has produced genuinely promising results for conditions like treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and end-of-life anxiety.

But there's also a danger in treating these as magic bullets. Psychedelics are powerful drugs that can produce powerful experiences. But a powerful experience is not the same as a treatment.

The fact that psilocybin therapy works (at higher doses, in structured settings, with professional support) doesn't mean that smaller doses of the same drug will work. It doesn't mean that self-administered microdoses will work. It doesn't mean that other psychedelics will work the same way.

Each claim needs evidence.

Moreover, the narrative around psychedelics can be shaped by economic incentives. Companies that develop psychedelic medicines have financial incentives to promote the idea that psychedelics work. Media outlets have incentives to publish exciting stories. Enthusiasts have psychological incentives to believe in something they've invested in.

None of this means psychedelics won't end up being valuable. But it does mean we need to maintain scientific rigor and skepticism, especially when claims sound too good to be true.

What Now? The Future of Psychedelic Research

So if microdosing doesn't work for depression, what's the future of psychedelic research?

First, the focus is likely to shift toward higher-dose therapies. Full-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy has better evidence, and clinical trials are ongoing. Companies that were betting on microdosing might pivot to this space.

Second, we'll likely see more rigorous research on microdosing for other indications. While the Mind Bio trial found it ineffective for depression, that doesn't mean it's ineffective for everything. Could it help with anxiety? With ADHD? With creativity or cognitive function in healthy individuals? These questions require research, not assumptions.

Third, researchers are beginning to understand the importance of set and setting. The context in which you take a drug—your expectations, the environment, the therapeutic support—matters enormously. Future research will likely place more emphasis on optimizing these factors.

Fourth, there's growing interest in whether specific subgroups might benefit from psychedelics. Maybe microdosing doesn't work for clinical depression, but could it help people with treatment-resistant depression? People with bipolar disorder? People with specific genetic profiles that make them more responsive to serotonergic drugs? Precision medicine approaches might unlock benefits that population-level trials miss.

Finally, there's the important work of understanding mechanism. How do psychedelics actually work? Which neurobiological changes are responsible for therapeutic benefits? Which patient characteristics predict who will respond? This mechanistic understanding could lead to better treatments, whether based on psychedelics or on other drugs that target the same pathways.

Implications for People Living with Depression

If you're reading this and you're struggling with depression, what should you take away?

First: don't delay seeking help because you're hoping microdosing will work. The evidence doesn't support it as a treatment. That doesn't mean your experience of feeling better after microdosing is fake, but it does mean that better options are available.

Second: depression is treatable. Established treatments like SSRIs, therapy, and exercise have evidence supporting them. Newer treatments like full-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy (currently in clinical trials, potentially available soon) show promise. Talk to a healthcare provider about what might work for you.

Third: understand the placebo effect. Placebo effects are real. They cause real changes in the brain and real changes in symptoms. If you're finding that a placebo helps you, that's valuable information. But it also means that working with a healthcare provider who can help you harness placebo effects strategically (rather than relying on them accidentally) might be even more valuable.

Fourth: be skeptical of miracle treatments. If something sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Good treatments usually work for 50-70% of people. They usually take time. They usually have tradeoffs. Be wary of claims that a treatment works for everyone, works immediately, or has no downsides.

The Larger Question: Why We Believe What We Believe

Ultimately, the microdosing story is about more than just psychedelics and depression. It's about how we form beliefs about health, how media influences those beliefs, and how economic incentives can shape narratives.

We live in an age of information abundance, but also information confusion. There are thousands of health claims out there. Some are backed by evidence. Some aren't. How do you tell the difference?

The scientific method, despite its flaws, remains our best tool. Rigorous studies, with controls for bias, with attempts to distinguish real effects from placebo effects, with replication across multiple groups—these are hard, expensive, and sometimes boring. But they work.

The alternative is relying on anecdotes, viral stories, and whatever happened to be covered by media today. That's how we end up believing things that sound good but don't actually work.

Is this skeptical? Yes. Is it sometimes depressing? Yes. But it's also liberating. Because when you understand how evidence actually works, you can make better decisions. You can cut through the hype. You can distinguish between what people hope is true and what the evidence actually shows.

In the case of microdosing for depression, the evidence shows: it doesn't work. Not because it's inherently implausible. Not because psychedelics can never be medicine. But because in this specific context, in this specific trial, with this specific measure of depression, the drug didn't outperform a placebo.

That's not the exciting headline. But it's the true one. And truth matters.

FAQ

What exactly is microdosing LSD?

Microdosing LSD involves taking a very small amount of the drug, typically 4-20 micrograms (compared to 50-100+ micrograms for a recreational dose). The intention is to consume enough to produce subtle mental effects like improved mood or focus without the hallucinatory experiences of a full dose. The practice became popularized around 2015, particularly in Silicon Valley circles interested in cognitive enhancement and biohacking.

Does the Mind Bio study prove that microdosing never works?

No. The Mind Bio study shows that in their trial, with their specific dose range (4-20 micrograms), over an 8-week period, LSD microdosing did not outperform a caffeine placebo for treating clinical depression. This doesn't mean microdosing has zero effects, or that it couldn't work for other conditions or in other populations. It means that for this specific use case (clinical depression), the evidence is negative. Larger studies or studies in different populations might yield different results.

What is the placebo effect, and why is it relevant to psychedelics?

The placebo effect is a real change in symptoms or biology that occurs when someone believes they're receiving a treatment, even if the treatment is inert. The placebo effect is especially strong for subjective experiences like mood, pain, and fatigue. For psychedelics, the placebo effect is particularly relevant because expectations are high and the drug's effects are subjective. Researcher Jay Olson found that placebo effects in psychedelic studies can actually exceed the effects of microdosing itself.

If microdosing doesn't work for depression, what about full-dose psilocybin therapy?

Full-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy shows much more promise. Clinical trials have found that a single dose of psilocybin (typically 20-30mg) combined with psychological support produces significant symptom reduction in treatment-resistant depression, often with effects lasting months. The mechanisms appear different from microdosing, possibly involving the neurobiological effects of the psychedelic experience itself, not just placebo effects. The FDA has granted "breakthrough therapy" status to psilocybin therapy for depression.

Why do people report feeling better after microdosing if it doesn't actually work?

There are several reasons. First, the placebo effect is real and can produce genuine mood improvements. Second, selection bias means that only people who feel better continue microdosing; those who don't feel effects stop and don't report. Third, regression to the mean: if someone starts microdosing during a depressive episode, random variation means they're likely to improve over time anyway. Finally, people often make concurrent lifestyle changes when they start microdosing, and these changes (better sleep, exercise, mindfulness) could explain improvements rather than the drug itself.

What should I do if I'm struggling with depression?

Talk to a healthcare provider. Depression is treatable, and established treatments like antidepressants, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and exercise all have evidence supporting their use. Depending on your specific situation, your provider might recommend one of these or a combination. If you're interested in newer treatments like psilocybin-assisted therapy, clinical trials are ongoing and your provider can help you understand what's available in your area.

Is LSD safe long-term?

LSD is not acutely toxic, but the long-term safety profile of chronic microdosing is not well established. Most research has focused on single-dose or occasional use. Chronic administration of any psychoactive substance carries potential risks that we don't fully understand, including effects on neurotransmitter systems and potential interactions with medications. If you're considering microdosing, discuss potential risks with a healthcare provider.

Why did the media cover microdosing as a miracle treatment if the evidence wasn't there?

Microdosing makes a compelling story: Silicon Valley insiders secretly optimizing their brains, psychedelics as the next frontier of mental health treatment, a scientific "edge" that normal people don't know about. These narratives are engaging and generate media attention. Additionally, early coverage often relied on anecdotal reports without emphasizing the lack of rigorous clinical evidence. This is common in health journalism: compelling narratives often outcompete more nuanced discussions of evidence.

The Takeaway: Science, Hype, and What Actually Works

The Mind Bio study doesn't prove that microdosing is useless. What it does prove is that the narrative around microdosing got way ahead of the evidence.

For a decade, we heard about microdosing as a near-miraculous treatment emerging from the intersection of neuroscience, pharmacology, and Silicon Valley innovation. When the science finally caught up, it painted a much more modest picture.

But this story has a broader lesson: skepticism about health claims is healthy. Requiring evidence before accepting something as true is not pessimism; it's wisdom. Every major medical advance started somewhere humble. But not every humble idea becomes a major advance.

The question isn't whether psychedelics have any potential. Full-dose psilocybin therapy shows genuine promise. The question is whether this specific use case—microdosing for depression—has been proven effective. And right now, the answer is no.

That's not exciting. But it's honest. And in medicine, honesty is the best policy.

For people struggling with depression, that honesty should be liberating. It means you don't have to wait for a miracle cure that probably isn't coming. You can access treatments that actually work, available now, supported by evidence.

For researchers and companies investigating psychedelics, it's a call to focus on the evidence. Full-dose therapies show promise. Other conditions might benefit. But let's not oversell what we don't know. Let's do the hard work of rigorous science.

And for all of us as consumers of health information, it's a reminder: trust the evidence. Question the narrative. Be skeptical of miracles. And remember that boring, unglamorous treatments often work better than exciting ones.

One final thought: the fact that microdosing doesn't work doesn't make the people who tried it foolish. They were experimenting with something that sounded plausible, seeking relief from suffering. That's understandable. But it's a good reminder of why we need science. Not to make us cynical, but to guide us toward what actually helps.

Key Takeaways

- MindBio's Phase 2B trial found LSD microdosing (4-20μg) underperformed caffeine placebo for depression treatment, with the caffeine group improving 5x more on depression rating scales

- The placebo effect dominates in microdosing studies, as evidenced by research showing patients on pure placebo report psychedelic effects when expectations are set appropriately

- Anecdotal reports of microdosing benefits suffer from selection bias: only people who feel better continue and report their experiences

- Full-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy (20-30mg combined with professional support) shows significantly more promise than microdosing, with placebo effects being less of a confound

- Media coverage of microdosing prioritized compelling narratives over scientific evidence for approximately a decade before clinical trials tested the claims

Related Articles

- Microdosing for Depression: Placebo Effect vs. Real Benefits [2025]

- Macaque Facial Gestures Reveal Neural Codes Behind Nonverbal Communication [2025]

- Character.AI and Google Settle Teen Suicide Lawsuits: What Happened [2025]

- Nasal Saline Rinse for Cold Prevention: Ancient Ayurvedic Remedy Proven by Modern Science [2025]

- Can a Social App Really Fix Social Media's 'Terrible Devastation'? [2025]

- The James Bond Shower Method: Cold Water Therapy Science [2025]

![Why Microdosing LSD Fails for Depression: The Placebo Study [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-microdosing-lsd-fails-for-depression-the-placebo-study-2/image-1-1769863007440.jpg)