Why Tank Controls Still Matter: The Tomb Raider Design Dilemma

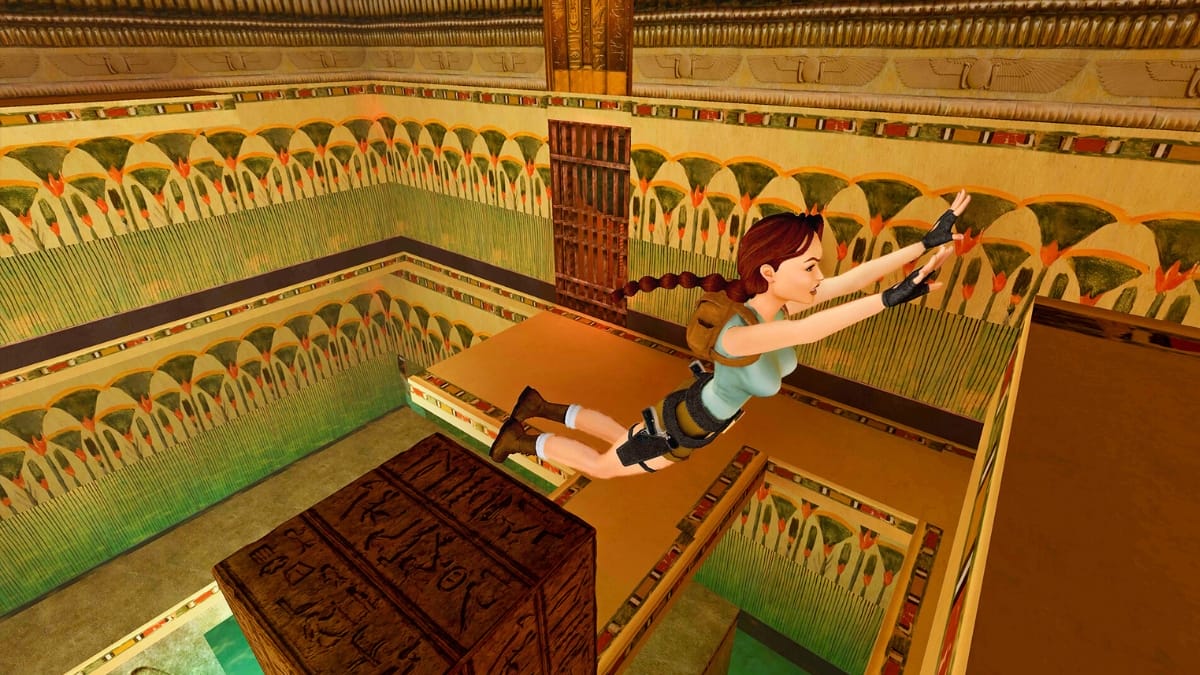

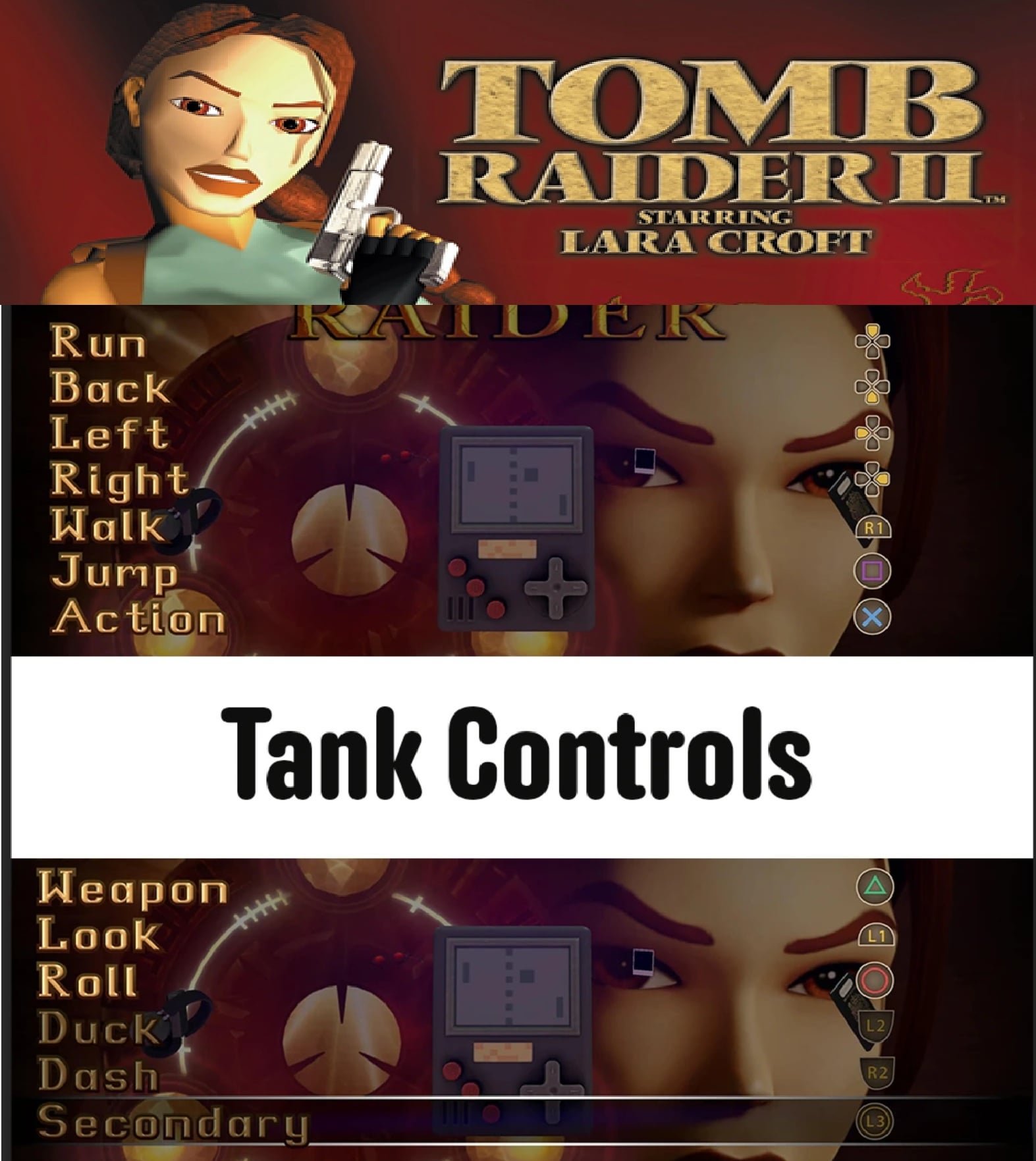

Back in 1996, Lara Croft didn't move the way you'd expect a character to move in a video game. Point your controller left, and she didn't strafe—she rotated her body in place, a mechanical turn that felt alien to players raised on games like Super Mario Bros. or The Legend of Zelda. Yet millions of people learned to love it.

This is the story of tank controls, one of gaming's most divisive design decisions, and why trying to "fix" a classic like the original Tomb Raider by bolting on modern controls actually breaks what made it work in the first place.

I'm not talking about shallow nostalgia here. I'm talking about something deeper: the relationship between input method and level design, between control philosophy and game architecture. When you understand why Tomb Raider was built the way it was, you start seeing ghosts of that design philosophy everywhere in modern games—even in the ones that try hardest to leave it behind.

The Control Scheme Nobody Asked For (But Everyone Adopted)

Let's rewind to 1996. The gaming industry was in chaos. Super Mario 64 dropped on Nintendo 64, showing the world how 3D platforming could work. Quake released the same year, proving you could play first-person shooters with keyboard and mouse. And then there was Tomb Raider, arriving on PlayStation and PC with something completely different from either approach.

Tomb Raider's tank controls weren't invented by Core Design. The term itself comes from arcade tank games where rotating the turret independent of movement made tactical sense. But applying it to a humanoid character navigating a 3D world? That was novel.

Here's how it actually worked. You pressed up on your D-pad or analog stick, and Lara moved forward—always forward, no matter which direction she was facing. Press down, she moved backward. Press left or right, and she turned in place, rotating her entire body without moving. To strafe, you had to first turn to face that direction, then move forward. It was deliberate. It was methodical. And by modern standards, it was sluggish as hell.

But in 1996, there was a strange elegance to it. The game world was relatively small, chambers were tightly designed, and the constraints forced designers to think creatively about how players would navigate space. Combat encounters were designed around the fact that you'd need to position yourself precisely before attacking. Platforming sections assumed you'd be counting steps and planning your approach like you were lining up a pool shot.

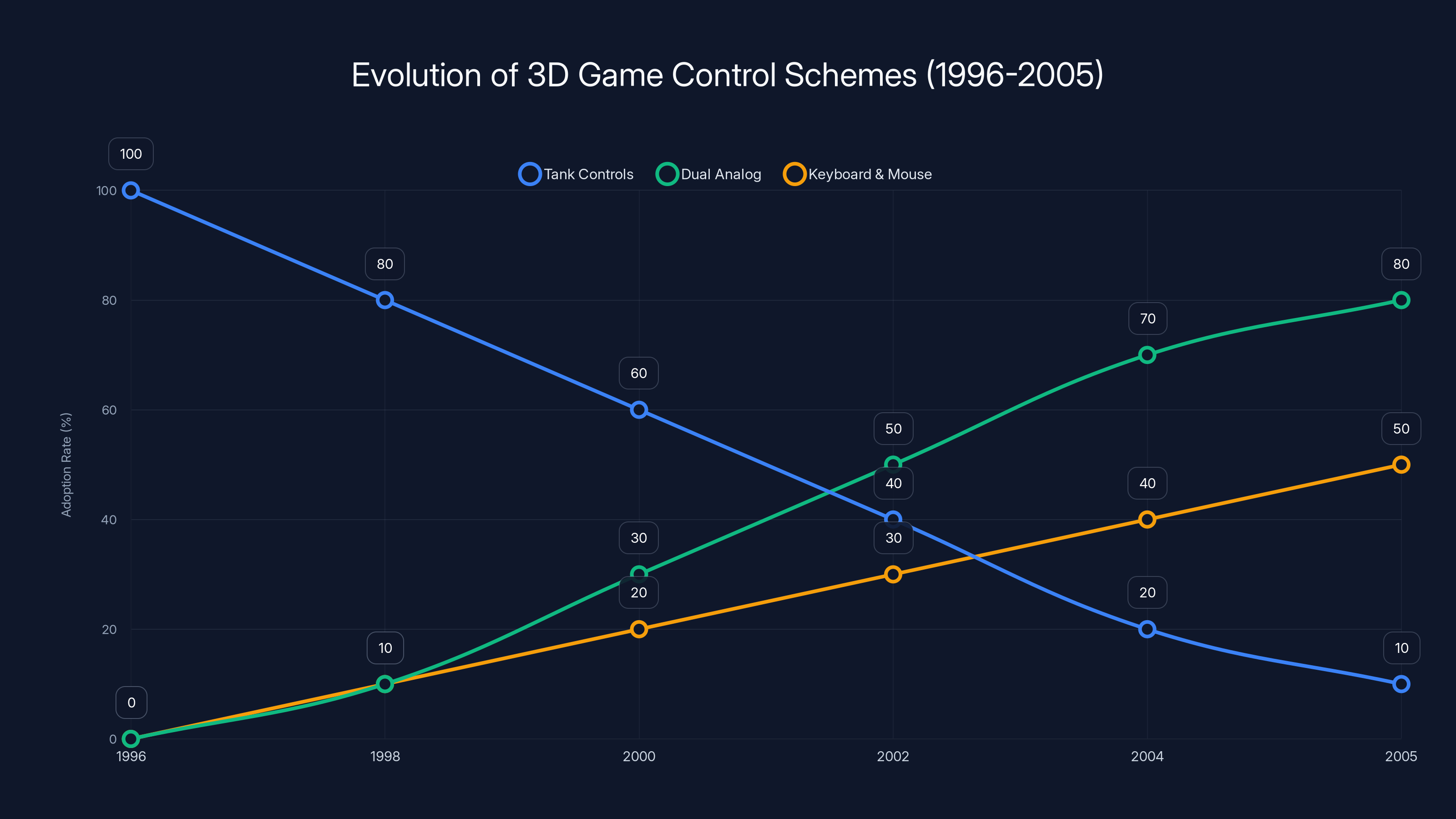

Within three to five years, though, the industry started experimenting with alternatives. By the early 2000s, games like Devil May Cry, Resident Evil 4, and the rebooted Tomb Raider series were using what we now call "modern" third-person controls: you could move in any direction independently from where the camera was pointing. Push the stick forward and your character moved toward the camera. Push it down and they moved away. Push it right and they strafed right. It was the control scheme everyone had intuitively expected all along.

Tank controls became niche. Resident Evil games clung to them for a while because the rigid controls actually created tension in horror scenarios—you couldn't just spin around and run. Some indie games and emulated classics kept them alive. But for mainstream AAA games, they were done. Finished. Relegated to history.

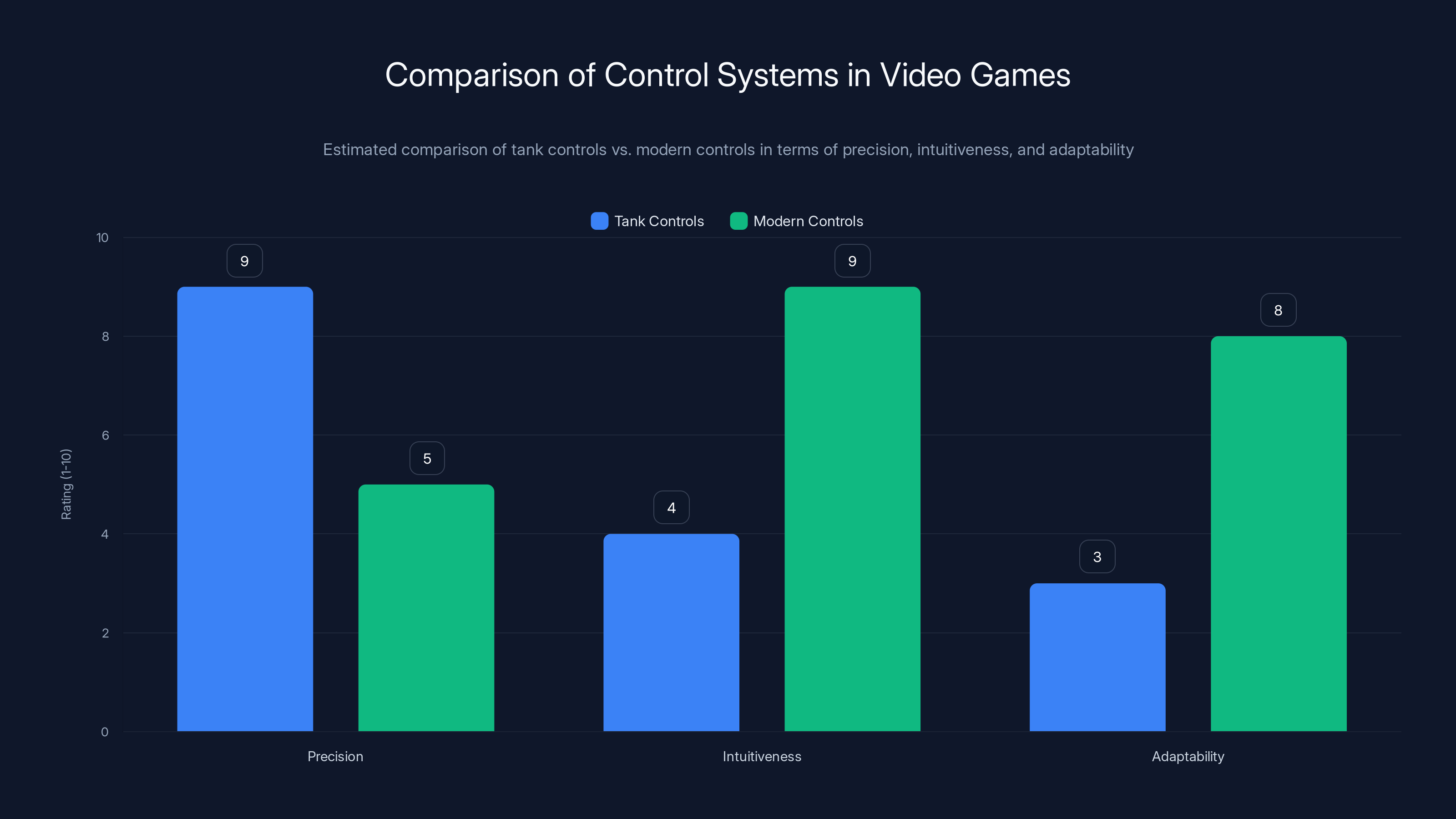

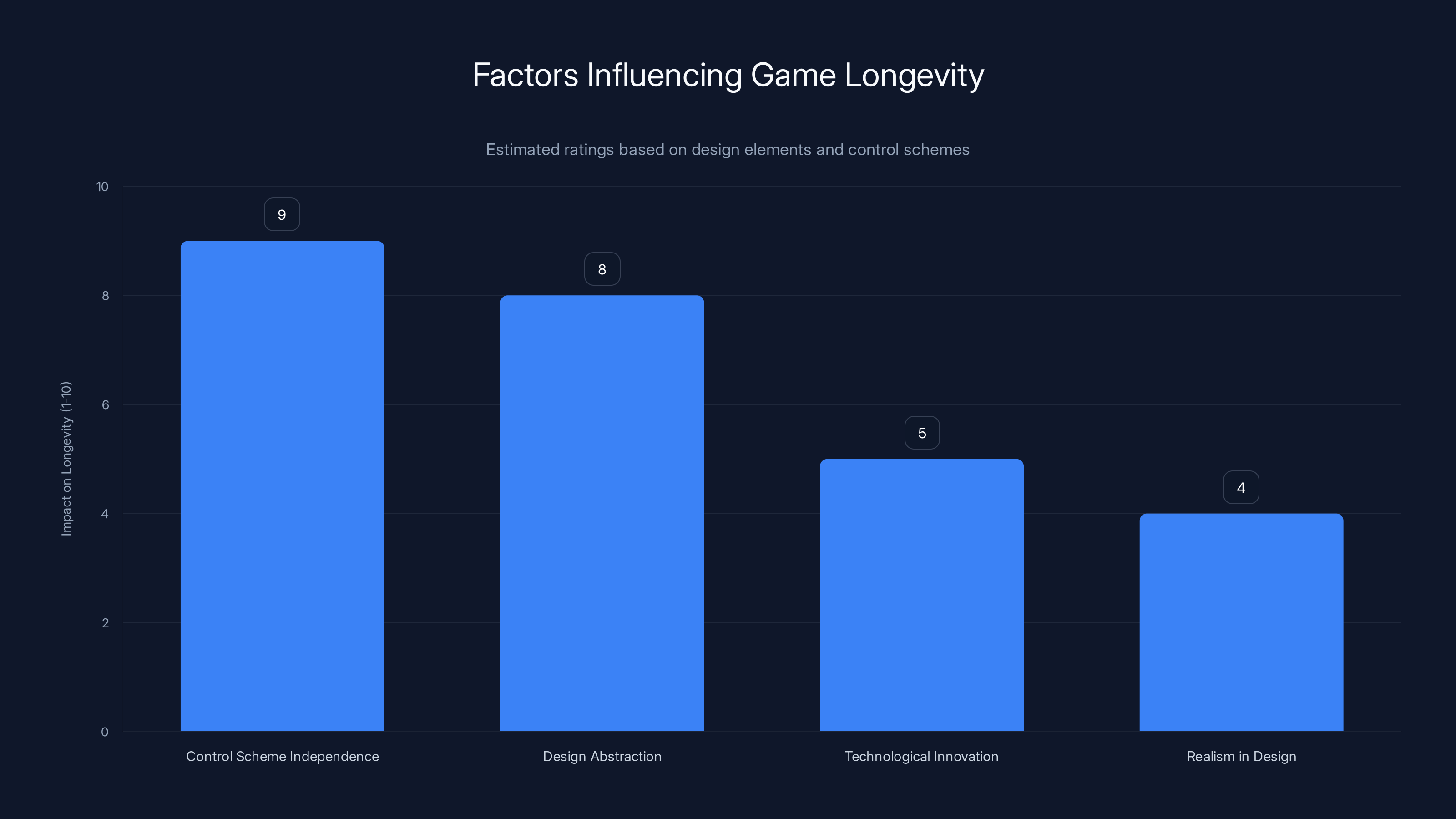

Tank controls offer high precision but lack intuitiveness and adaptability compared to modern controls, which excel in user-friendliness and flexibility. (Estimated data)

The Grid System That Changed Everything

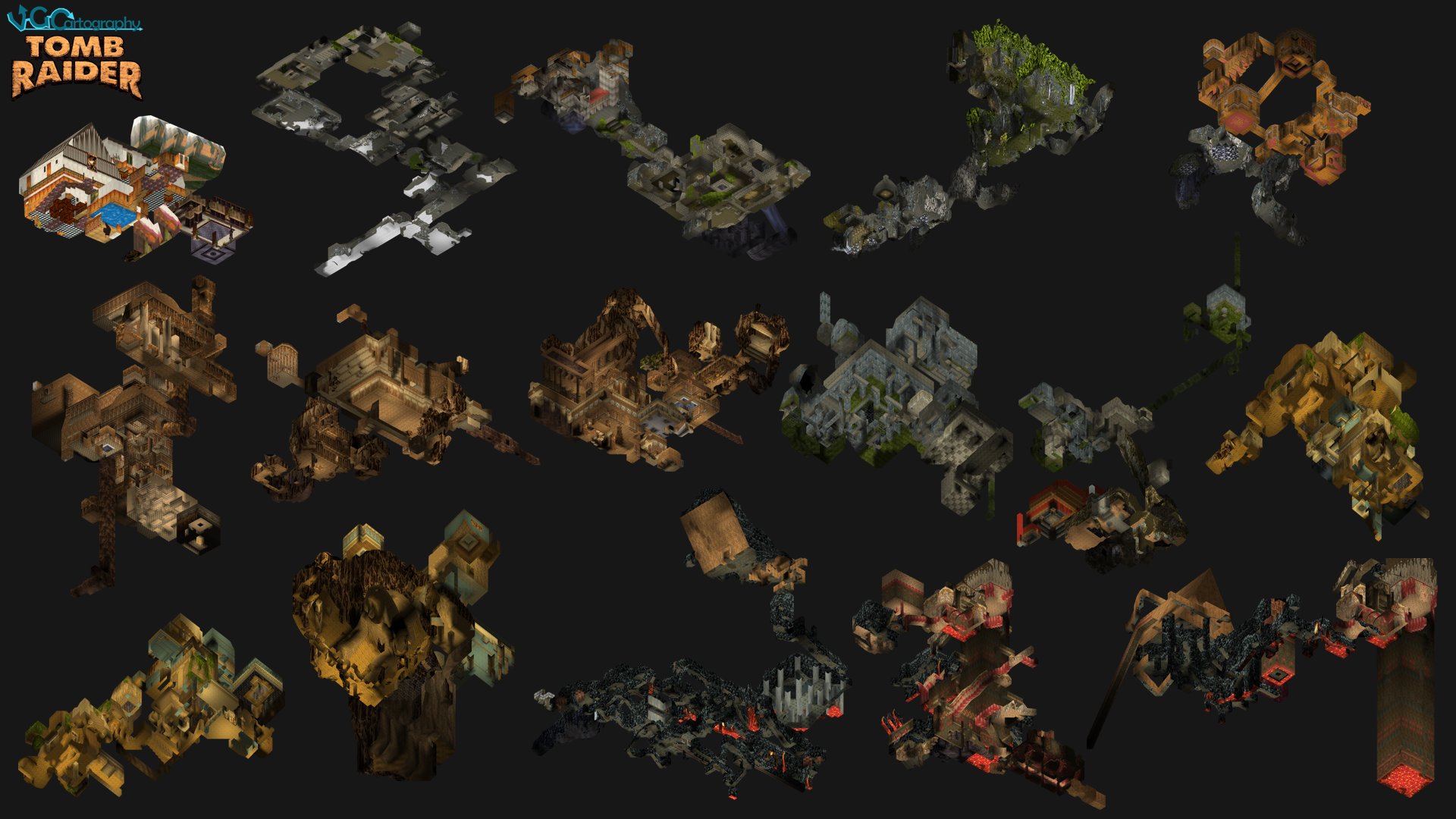

Now here's where things get interesting, because understanding why Tomb Raider broke with modern controls requires understanding something most modern gamers never think about: the grid.

Tomb Raider wasn't designed on a continuous 3D plane. Every platform, every jump, every movement possibility was built on an invisible grid. Think of it like chess—Lara occupied squares, and she could move predictably from one square to the next. A jump forward always traveled the same distance. A sidestep covered the same ground. Side-jump backward? Identical distance every time.

This wasn't a limitation. It was the entire point. Game designer Jordan Mechner's Prince of Persia from 1989 worked the same way. Mechanics-wise, platforming was about counting steps, positioning yourself at exactly the right spot, and then executing the jump or move. You could theoretically beat the game on your first playthrough if you memorized all the positions, because the game gave you complete control over your placement on that grid.

Tomb Raider borrowed this wholesale. The entire game—every single room, every puzzle, every combat encounter—was built assuming players would position themselves on a grid and move in discrete, predictable increments. The tank controls weren't a bug; they were the interface through which players interacted with that grid system.

When you pressed left or right with tank controls, you weren't strafing—you were rotating your position on the grid. When you pressed forward, you were advancing by a specific number of grid squares. The system was so elegant that players could optimize their movement, could develop muscle memory for precise positioning, could master the game through understanding and predicting exactly how far any action would take you.

This is why the original Tomb Raider had such exquisitely designed level design. Designers understood every pixel of movement they could rely on. They knew exactly how to place platforms so that a three-step approach followed by a side-jump would be just barely makeable, or barely not makeable. They could tune difficulty with precision because the control system was so rigid and predictable.

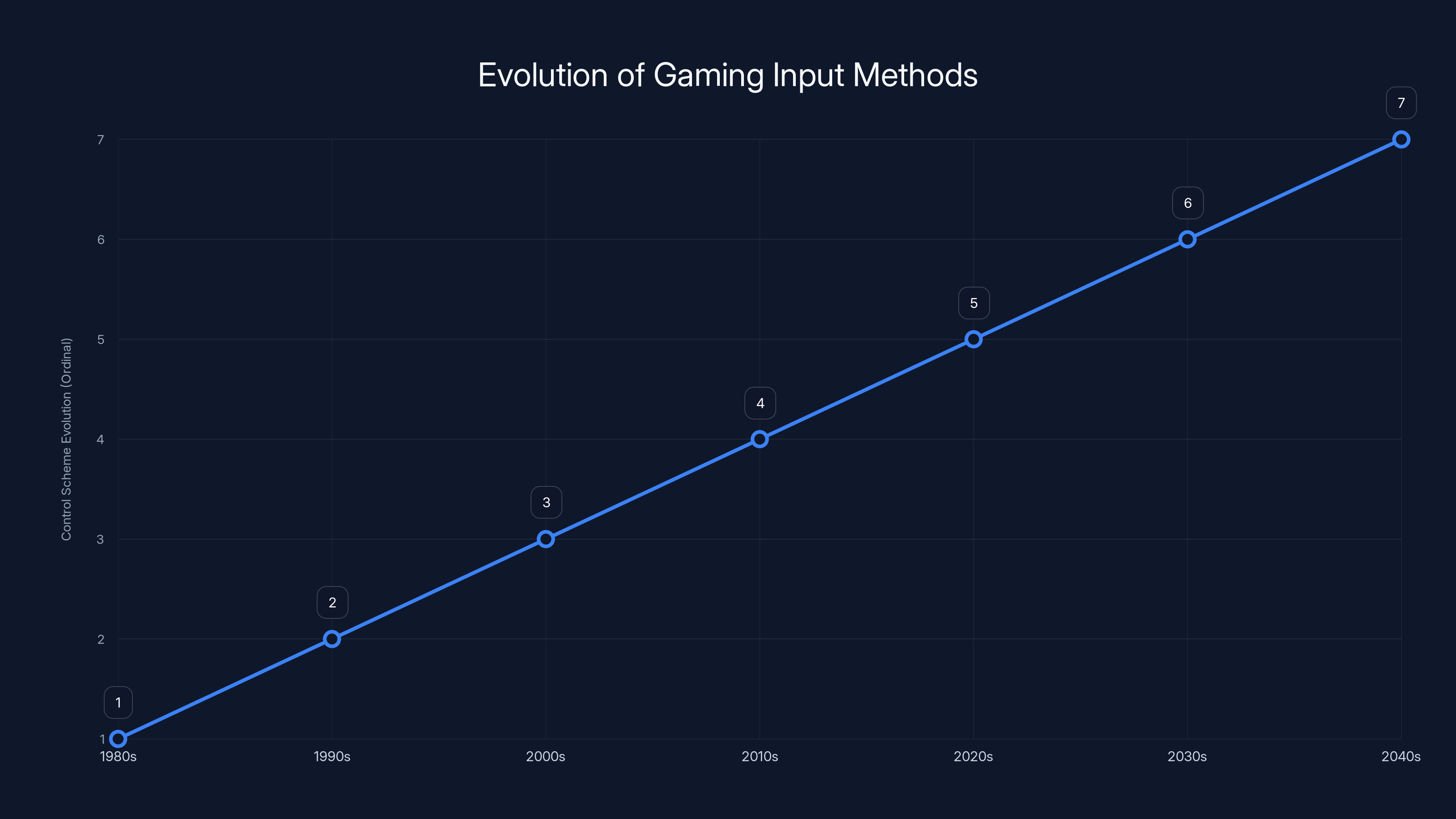

Estimated data showing the evolution of gaming input methods from digital D-pads to potential future schemes. Each decade sees a shift in dominant control methods.

When Modern Controls Meet Grid Design

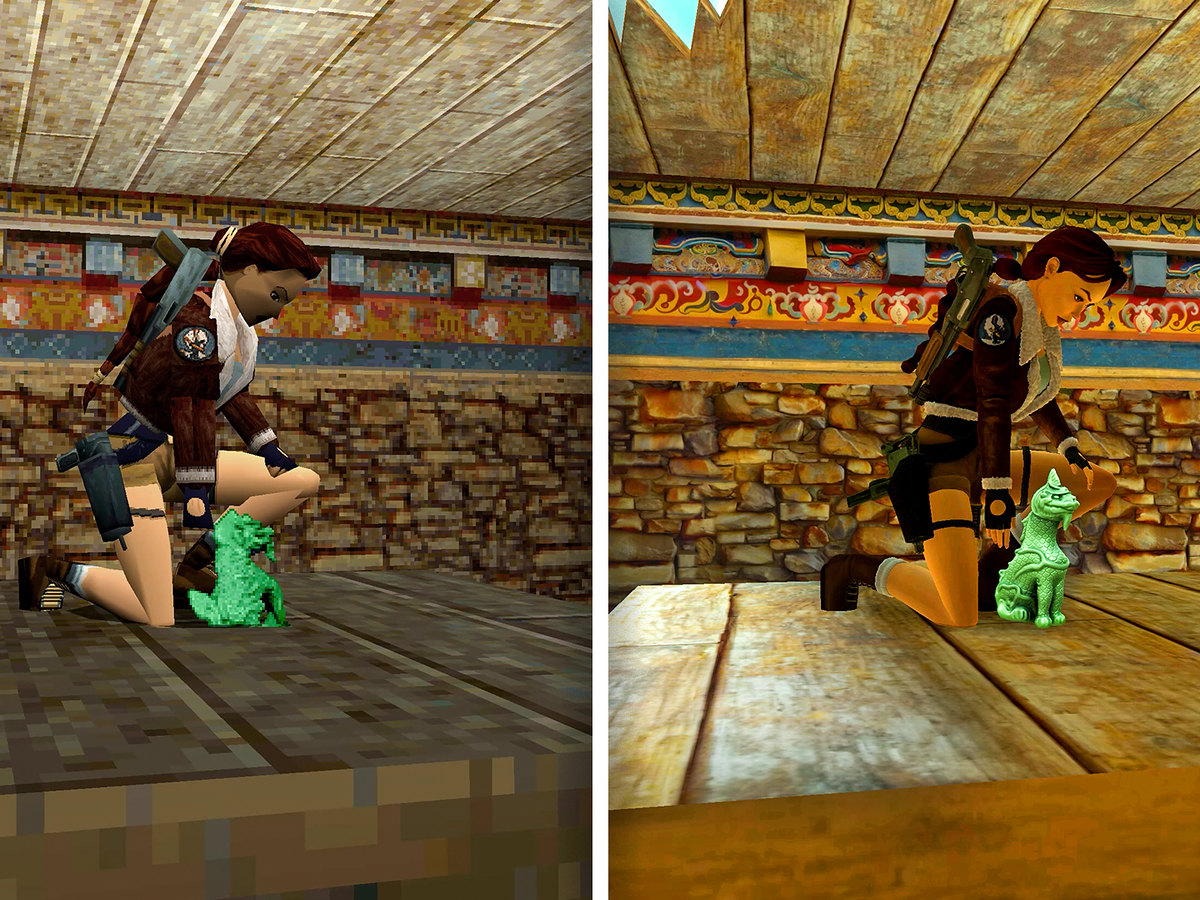

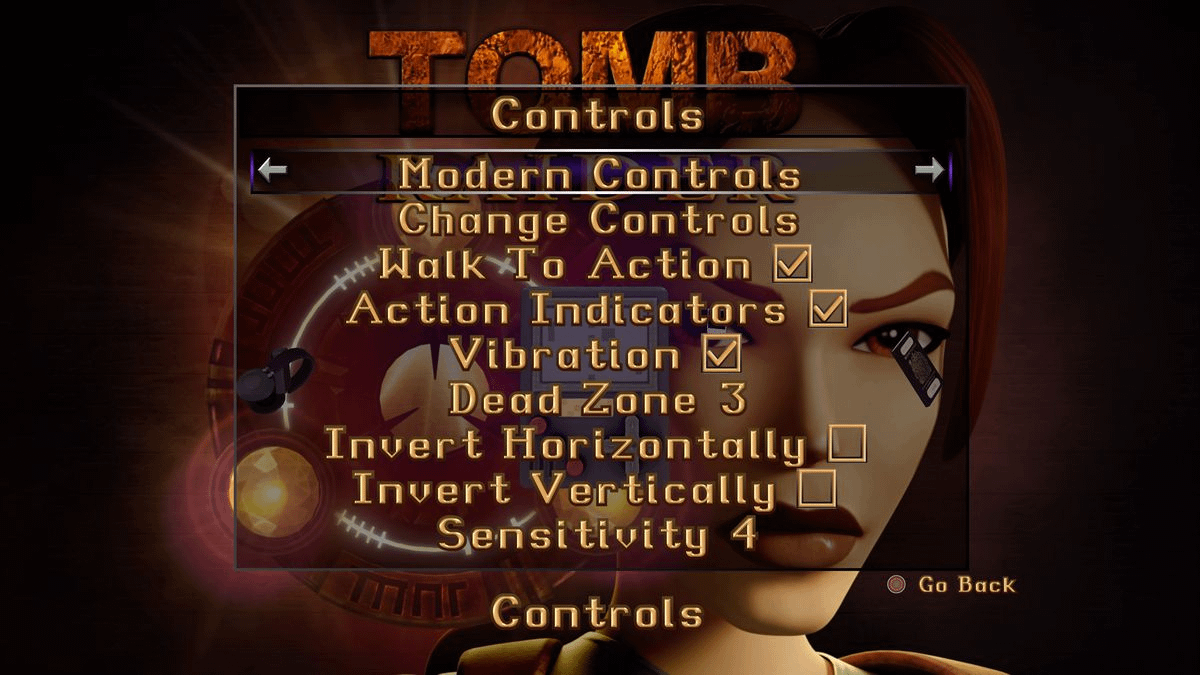

Fast forward to 2024. The Tomb Raider I-III Remastered collection arrives, and developers at Aspyr Media include an optional modern control scheme. No more turning in place. No more counting steps. Just point the right stick where you want to go, and Lara moves there. It feels great during combat sequences—suddenly you can circle an enemy and react to their attacks with actual reflexes instead of planning your movements like you're in a turn-based game.

But it breaks platforming almost entirely.

Here's why. With modern controls, your input is continuous rather than grid-based. Push your stick slightly forward and Lara moves slowly. Push it all the way and she sprints. Angle it northeast and she moves at a 45-degree angle across the grid rather than along it. The system becomes analog instead of digital, and suddenly all those carefully positioned platforms don't line up anymore.

A jump that was designed to land perfectly when you took exactly three steps forward doesn't work when you're using modern controls, because you might take 2.7 steps, or 3.3 steps, or move at any fractional position in between. Platforms that relied on precise grid positioning become nightmares—you're constantly over-jumping or under-jumping, never quite landing where you expect.

Reviewers and players experienced this immediately when the remaster launched. Reddit threads and reviews were filled with complaints about platforming feeling broken when using modern controls. And the thing is, the developers at Aspyr weren't incompetent. They made the best attempt possible at retrofitting modern controls onto a grid-based game. The problem is that it's an impossible task. You can't jam a continuous analog input system into a discrete grid-based design and have it work smoothly.

The modern control scheme still feels better during combat, because combat doesn't rely on precise grid positioning the same way platforming does. You just need to be "approximately" near an enemy and able to rotate around them. But the moment you hit a platforming section, the mask comes off. Modern controls make Tomb Raider worse at the very thing that made it special.

This creates an impossible situation for players. You can play with tank controls and suffer through the sluggish positioning in combat, or you can use modern controls and suffer through imprecise platforming. There's no winning. The game's fundamental architecture has become a liability rather than an asset.

Why Your Brain Can't Adapt Anymore

Here's something that might surprise you: the people who played Tomb Raider in 1996 didn't think tank controls were terrible. Some found them weird, sure, but the majority adapted within a few hours of playtime. Your muscle memory is plastic. It rewires itself.

But that was then. This is now. And your brain has spent the last 20-30 years being trained by literally thousands of games that use modern controls. That's not a small amount of time. That's not a shallow groove in your neural pathways. That's an entire highway system.

When you pick up a modern game, you expect certain things: pushing forward moves you toward the camera, pushing right makes you strafe right, your character's facing direction is independent from your movement direction. You've developed such deep muscle memory around these expectations that violating them feels actively wrong. Not just unfamiliar—wrong.

The researchers who study game design call this "affordance." An interface affords certain actions. A steering wheel affords turning. A keyboard with arrow keys affords directional movement. Tank controls afford positioning-based gameplay. Modern controls afford immediate directional response.

When you break the affordance match—when you use tank controls in a game designed for modern controls, or vice versa—your brain has to do extra work. You're constantly fighting against 20 years of habit. It's like trying to write your name with your non-dominant hand. Theoretically possible. Practically exhausting.

Games with control scheme independence and abstract design tend to age better, while those reliant on realism and specific technological innovations may struggle. Estimated data.

The Platformer's Dilemma: Grid vs. Continuous Movement

This tension between grid-based design and continuous analog input isn't unique to Tomb Raider. It's a fundamental fork in how game designers approach 3D platforming, and the choice cascades through every decision they make.

Look at Super Mario 64. That game was designed for analog controls from the ground up. Yes, Mario stands on platforms, but the camera can rotate, Mario can approach platforms from any angle, and the game doesn't care which direction you came from. The level design accommodates continuous 3D movement. You can pick up the controller and slide your thumb in any direction, and the game responds smoothly.

Now look at something like Bloodborne, a 3D action game that (before 2015 patches) used a control scheme that felt somewhat tank-like by modern standards. Your character turned slowly. Your movement felt weighty. The level design compensated by creating deliberate, tactical spaces where precision felt less important than positioning and patience.

And then there's The Witness, which took grid-based design to its logical extreme for modern times. Everything in that game is built on clean geometric grids. Every puzzle is solved by understanding spatial relationships on those grids. The continuous camera and movement don't break the design because the design doesn't rely on precise movement—it relies on how you see and think about space.

Each of these approaches makes sense within its own context. But Tomb Raider occupied an awkward middle ground. It was designed for tank controls and grids, but modern players expect analog responsiveness. Trying to retrofit one onto the other creates cognitive dissonance. Your hands expect one thing, but the level design demands another.

What Modern Game Designers Got Right (And Wrong)

The industry's move away from tank controls wasn't arbitrary. Modern controls are objectively more responsive, more intuitive for new players, and faster for executing complex actions. A player can switch from Elden Ring to Stellar Blade to Final Fantasy XVI and immediately feel comfortable because the controls are similar enough that their muscle memory transfers.

That's a real win. It lowered barriers to entry. It made character control more expressive. It allowed for action games with reaction times measured in milliseconds rather than half-second deliberation windows.

But in solving the responsiveness problem, designers lost something: precision. Intentional limitation. The kind of design where constraints force creativity.

Grid-based design forces you to think geometrically. You can't just "kind of" jump to that platform—you either jump there or you don't. Designers have to make meaningful choices about spacing. Players have to actually plan and execute rather than just react.

There's something to be said for that kind of design. It's why emulated classic games still have dedicated players. It's why games like Into the Breach, which used grid-based tactics in a modern context, felt so fresh and different. It's why speedrunners spend thousands of hours finding frame-perfect moments in games designed before frame-perfect inputs were even a concept.

The question that Tomb Raider's modernization raises is whether we've optimized ourselves into a corner. We solved the "tank controls are clunky" problem by switching to a different system entirely. But we lost the design possibilities that came with that constraint.

The chart illustrates the decline of tank controls and the rise of dual analog and keyboard & mouse schemes in 3D games from 1996 to 2005. Estimated data.

The Remaster's Honest Attempt and Inevitable Failure

To be completely clear: the people at Aspyr Media who worked on the Tomb Raider I-III Remastered weren't lazy or incompetent. They understood the problem. They tried a solution. And they accepted the compromise gracefully.

By including both control options, they acknowledged something important: some players wanted the authentic 1996 experience, and others wanted to experience the game through a modern lens. Rather than forcing one or the other, they let players choose.

That's honesty. That's customer respect. But it's also an admission of defeat, because there's no control scheme that makes Tomb Raider perfect for modern players. Tank controls feel dated. Modern controls break the platforming. You have to lose something either way.

Reviewers who tested both control schemes came away frustrated, but they also came away with a realization: Tomb Raider was never broken. It was perfectly designed for what it was trying to do. The "problem" is that what it was trying to do is no longer what modern players expect from a game.

That's not a failure of the remaster. It's just the reality of trying to bridge two different eras of game design philosophy. You can't go backward and forward simultaneously.

Why Some Games Aged Better Than Others

Not every game from 1996 struggles the way Tomb Raider does. Take Quake, which also released that same year and used keyboard controls for movement, mouse controls for looking around. That input paradigm is so firmly established in modern first-person games that playing Quake today feels immediately familiar. The controls might be more precise than required, but they're not fighting against your muscle memory.

Or consider Final Fantasy VII, which used an isometric perspective and menu-based combat. That design hasn't aged the way real-time 3D controls have because it was never trying to be "realistic" movement in the first place. It was always abstracted. Modern players understand menu systems and turn-based games because those systems are still used in many modern titles.

But Tomb Raider sat right at the intersection of technological innovation and design philosophy. It was trying to be a "realistic" (by 1996 standards) 3D game with fluent character control, and the control method they chose was, in hindsight, a dead end.

This tells us something important about game design longevity. Games age well when their design is fundamentally independent from the specific control scheme of their era. Games age poorly when they're built entirely around a control scheme that was designed for a specific problem at a specific moment in time.

Estimated data shows a decrease in adaptation time to control schemes from the 1990s to the 2020s, reflecting increased standardization and familiarity with modern controls.

The Legacy That Tank Controls Left Behind

Even though tank controls are gone from mainstream gaming, their ghost lingers in how modern games are designed and how we talk about design constraints.

When developers talk about "weight" in character movement—that feeling that your character has mass and momentum—they're often implementing ideas that came from tank control design. In tank controls, you couldn't instantaneously change direction. You had to commit to a path. Modern games implement weight through acceleration curves and animation blending, but the philosophical idea is the same: movement matters.

When designers talk about"tactical positioning" in action games, they're often reaching back to design principles established in the tank control era. Games like Dark Souls aren't tank-controlled in the literal sense, but they have elements of that deliberate, thought-before-action philosophy baked into their DNA.

And speedrunners still optimize for tank control games like Final Fantasy VII and Resident Evil 2 because the grid-based movement systems allow for frame-perfect optimization that modern analog controls make more difficult (though not impossible).

Tank controls aren't dead. They're just been absorbed into the broader language of game design, filtered through the lens of what worked and what didn't.

Why You Probably Won't Revisit Original Tomb Raider

Here's the harsh truth: Tomb Raider in 2025 is a game that assumes you either have nostalgia for it or you're willing to engage in a kind of archaeological experience. You probably won't stumble across it organically and think "oh, this is great." You'll either seek it out intentionally or you won't play it at all.

That's not a condemnation of the game. The level design is still excellent. The atmosphere is still memorable. The core idea of a female protagonist spelunking through ancient tombs in the mid-1990s was genuinely novel and compelling.

But the moment-to-moment experience of playing it fights you at every turn. Combat feels sluggish. Platforming feels imprecise. And even though intellectually you understand why the game was designed this way, your fingers and your hindbrain don't care. They just know something feels wrong.

That's the real legacy of tank controls: they demonstrate that control schemes matter more than most players realize. They're not just surface-level input methods. They're fundamental to how a game feels, how its levels are designed, and whether it'll feel "natural" or "dated" when you go back to it.

The remaster is still worth checking out for the historical importance and level design brilliance. But don't expect to fall in love with it the way players did in 1996. Your brain has evolved past that, and there's no control scheme that can bridge that gap.

The Lesson for Modern Design

What should game designers take away from the Tomb Raider story? Probably this: the tools you use to build your game matter as much as the game itself. If you lock your level design into a specific control paradigm, future remasters and ports might struggle. If you design more generally—platforms that accommodate multiple approaches—you get more flexibility.

But there's also value in specialization. Tomb Raider was amazing precisely because it was so tightly designed around tank controls. That constraint bred creativity. A more flexible design might have been less interesting.

So maybe the real lesson is this: design with intention. If you're building around a specific control scheme, commit to it. Make it work beautifully. Don't half-ass it and hope future technology fixes your problems. But also understand that your design choices lock you into a particular era. That's not necessarily bad. It's just real.

The original Tomb Raider is a perfect artifact of 1996. It couldn't exist in quite the same way in 2025, and that's okay. Not every game needs to age forward. Some games are beautiful precisely because they're of their time.

Thinking Beyond Tank Controls

The deeper conversation here isn't really about tank controls. It's about how input methods shape games, and how games shape our expectations of input methods. It's a feedback loop that doesn't have a natural endpoint.

Every few years, gaming consolidates around a new standard. In the 1980s, it was digital D-pads and a jump button. In the 1990s, it was analog sticks and camera controls. In the 2000s, it was dual analog thumbsticks with standardized button layouts. In the 2010s, we optimized the hell out of those standards.

Now we're seeing another shift. Motion controls didn't catch on broadly, but haptic feedback and adaptive triggers are becoming more important. Gesture controls in mobile games have created their own design language. VR has forced everyone to rethink how players interact with 3D space.

Whatever control scheme becomes dominant in the next 10-20 years will seem obvious and intuitive to anyone growing up with it. And in 2045, someone will write an article about how some current-era game doesn't work with whatever comes next, and the cycle will continue.

Tomb Raider just happened to be the game that revealed this pattern. It was too early for modern controls to feel right, but too late for tank controls to feel timeless. It occupied an awkward middle ground, and that middle ground is where most games live as they age.

The ones that survive are either the ones with design so elegant it transcends control scheme, or the ones whose control scheme was so distinctive that it becomes historically interesting rather than frustratingly dated. Tomb Raider manages both, which is why people still play it, even knowing what they're getting into.

FAQ

What are tank controls in video games?

Tank controls are a character movement system where pressing forward or backward makes your character move in that direction relative to where they're facing, while pressing left or right rotates your character in place without moving. This was common in early 3D games like the original Tomb Raider and early Resident Evil titles, but fell out of favor as modern analog controls became standardized.

Why did Tomb Raider use tank controls instead of modern controls?

Tomb Raider was designed using a strict grid system inherited from 2D platformers and games like Prince of Persia. Tank controls provided precise, predictable movement that aligned with this grid-based architecture. Designers could position platforms and puzzles knowing exactly how far Lara would move with each input, enabling exquisitely balanced challenges.

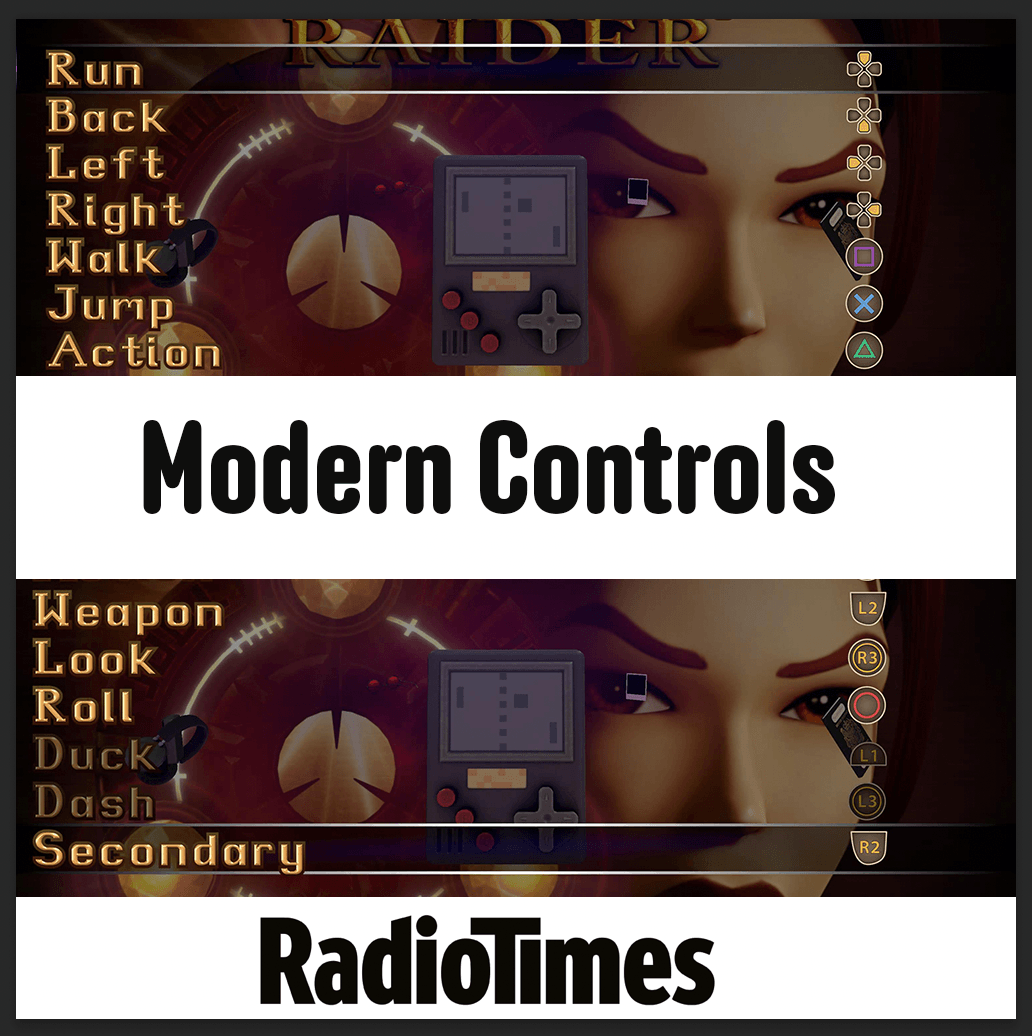

What's the difference between tank controls and modern controls?

Tank controls require you to rotate toward your target, then move forward. Modern controls let you push the stick in any direction and your character moves that way immediately, independent of which way they're facing. Modern controls are more responsive and intuitive but break the precise grid-based design that games like Tomb Raider relied on.

Why doesn't modern control work in the original Tomb Raider?

Modern controls are analog (continuous), while Tomb Raider's level design assumes digital (discrete, grid-based) movement. With tank controls, a jump that travels exactly three grid squares always lands in the same spot. With modern controls, you might move 2.7 or 3.2 grid squares, causing jumps designed for precision to feel imprecise and frustrating.

Can remasters fix tank control games by adding modern controls?

Partially, but not completely. Modern controls improve combat situations that don't rely on grid precision, but they break platforming sections that were designed around exact movement distances. No single control scheme can make both work equally well in a game built for tank controls.

Do any modern games still use tank controls?

Very few mainstream games use pure tank controls, but the design philosophy persists in games emphasizing "weight" and deliberate positioning. Some indie games use grid-based controls intentionally, and survival horror games occasionally experiment with movement limitations as a tension-building tool.

Why is it harder to adapt to tank controls now than in 1996?

Your brain's muscle memory has been shaped by 20-30 years of games using modern controls. That's not a casual habit—it's a deeply grooved neural pathway. Modern controls are now the default expectation, and violating that expectation requires conscious effort and retraining.

Will future game remasters face similar control scheme problems?

Likely yes. Whatever control system becomes standard in the next decade will eventually feel dated. Games designed specifically around today's control schemes may struggle to feel natural when tomorrow's input methods become dominant. This is an ongoing cycle of video game design.

What can modern games learn from Tomb Raider's design approach?

Game designers can learn that constraints breed creativity, but those constraints have shelf lives. Specialized control schemes create tightly designed experiences, but they also lock games into specific eras. Balancing innovation with longevity requires thinking beyond just the current control standard.

Is the Tomb Raider I-III Remastered worth playing despite the control issues?

Yes, if you're interested in game design history and level architecture. The game's environmental design and puzzle structure remain excellent. However, you'll need patience with the controls no matter which option you choose. Tank controls feel sluggish in combat; modern controls feel imprecise in platforming. It's an archaeological experience rather than a timeless classic.

Key Takeaways

- Tank controls weren't a limitation but an interface designed for grid-based level architecture that defined 1996's Tomb Raider

- Modern analog controls break grid-based platforming design, making combat better but platforming worse in classic games

- 20-30 years of modern control training has rewired player muscle memory so deeply that reverting to tank controls requires conscious effort

- Games age best when their core design transcends their control scheme, or when control schemes are historically distinct enough to fascinate rather than frustrate

- The tank control case demonstrates that game remasters face an impossible choice: authenticity or modern accessibility, but rarely both

Related Articles

- Ubisoft Cancels 6 Games Including Prince of Persia Remake [2025]

- Ubisoft Cancels Prince of Persia Remake: Inside the Major Gaming Restructure [2025]

- Arc Raiders Out-of-Bounds Exploits: Why Players Still Can't Trust Stella Montis [2025]

- MIO: Memories in Orbit Review - Best Metroidvania [2025]

- Krafton's Quest for the Next PUBG: Inside 26 Games in Development [2025]

- Relooted Heist Game Gets February 10 Release Date [2025]

![Why Tank Controls Still Matter: The Tomb Raider Design Dilemma [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-tank-controls-still-matter-the-tomb-raider-design-dilemm/image-1-1769031351809.jpg)