Introduction: The Relic That Wouldn't Die

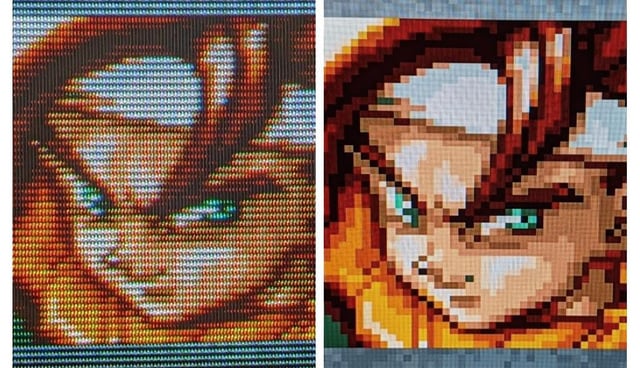

A Guatemalan family did something that shocked Samsung. They walked into a trade-in center with a 39-year-old Philips CRT television. Not a museum piece. Not a collector's item. A working TV that had been in active use for nearly four decades. They'd watched the Berlin Wall fall on that screen. They'd raised kids in front of it. They'd lived their lives with that one television, and it still did its job.

Samsung executives didn't know whether to feel proud of the trade-in program or horrified by the implicit critique. The real story wasn't about one family's nostalgia. It was about a fundamental shift in how products are designed, manufactured, and discarded.

Think about the last TV you bought. How many years do you expect it to last? Five? Seven? If you're optimistic, maybe ten? Now imagine a television that works flawlessly for nearly forty years without a single major repair. That gap isn't a mystery. It's the result of intentional design choices made by an entire industry.

This article isn't about romanticizing old technology. CRT televisions had real limitations. The picture quality was inferior by modern standards. They consumed massive amounts of electricity. They took up half your living room and weighed as much as a small car. But they were built with something modern electronics have largely abandoned: a commitment to durability that extended product lifespans far beyond what consumers today expect.

The shift toward disposable electronics isn't accidental. It's the product of converging economic incentives, manufacturing philosophy changes, planned obsolescence strategies, and the race to lower costs. To understand why that 39-year-old Philips TV still worked while your Samsung from 2018 is probably dying or already dead, you need to understand the economics of electronics manufacturing, the engineering trade-offs that define modern consumer devices, and the business models that replaced the "build it once, sell it forever" philosophy of previous generations.

What happened in television is happening everywhere. Refrigerators that fail at seven years. Laptops with soldered components you can't replace. Smartphones engineered to be unrepairable. It's not inevitable. It's a choice.

TL; DR

- CRT TVs lasted 30-40+ years because they were built with redundant components, simple designs, and generous engineering margins

- Modern TVs fail in 5-7 years due to complex circuits, soldered components, inadequate thermal design, and cost-cutting measures

- Planned obsolescence is real but operates indirectly through design choices, firmware updates, and repairability barriers, not manufacturing defects

- Cost reduction drove the change: manufacturers compete on price, which forces corners to be cut in component quality, thermal management, and modularity

- The economics favor replacement: companies make more money when products fail and customers buy new ones than when they buy once and keep devices indefinitely

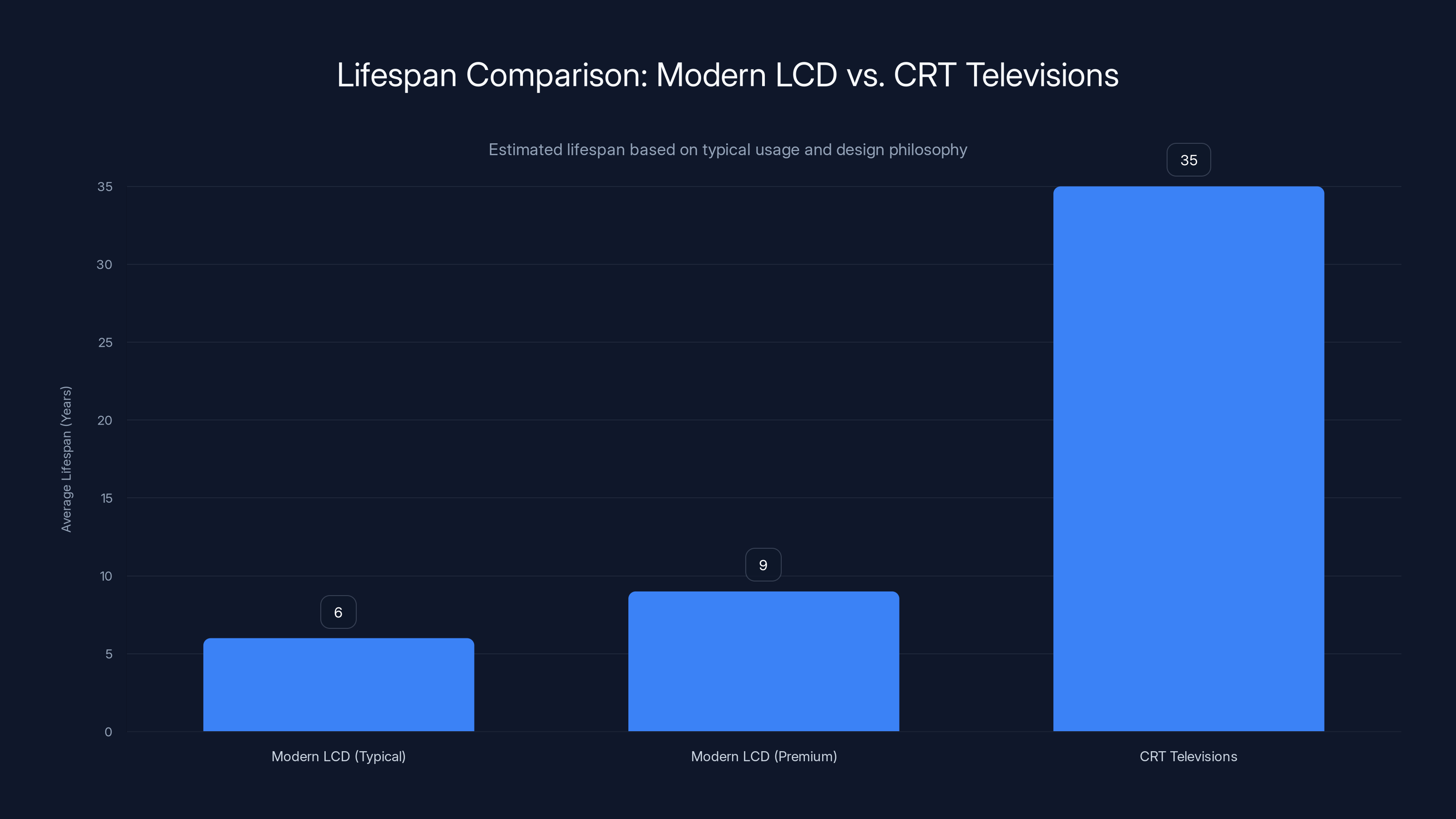

Modern LCD televisions typically last 5-7 years, with premium models reaching up to 10 years, compared to CRT televisions that often lasted 30-40 years. Estimated data based on design trends.

The Engineering Philosophy Divide: Then vs. Now

The Philips CRT that lasted 39 years was built on a completely different engineering premise than the LCD that replaced it. This wasn't about superior craftsmanship in some romantic sense. It was about different design constraints, different cost structures, and different market expectations.

Redundancy by Design in Vintage Electronics

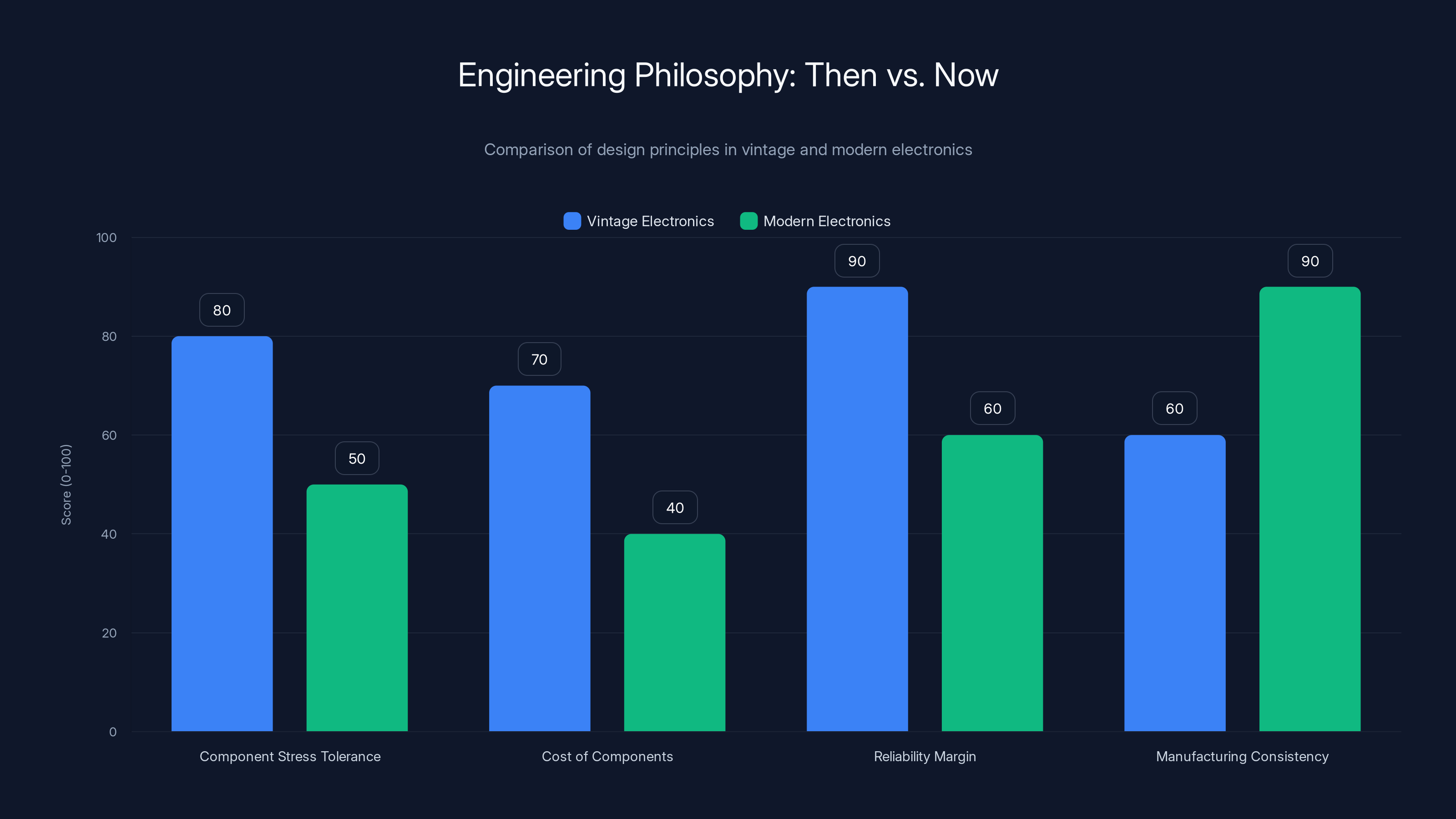

Old CRT televisions operated on a principle called "derating." Engineers would identify the maximum stress a component might experience and then specify components rated for significantly higher stress levels. A capacitor might be rated for 1,000 hours of operation at its maximum voltage, but it would be installed in a circuit where it would never see more than 60% of that voltage under normal operation. This created enormous safety margins.

Why? Partly because component manufacturing in the 1970s and 1980s was less consistent. A 100-microfarad capacitor from one factory might genuinely be different from one made by a different manufacturer. The best way to ensure reliability was to over-specify everything. Use a component rated for twice what you need. That component costs slightly more, but it survives power surges, aging, temperature fluctuations, and manufacturing variation with ease.

In that 39-year-old CRT, if one capacitor degraded slightly after twenty years, ten others were handling the load with room to spare. The power supply could tolerate voltage fluctuations that would kill a modern power supply. The transformer was wound with thick copper and more layers of insulation than theoretically necessary. Everything was oversized.

Modern electronics operate on the opposite principle: exact specification. Engineers use simulation software to determine the precise stress on every component under normal operating conditions. Components are specified as close as possible to that calculated stress. A power supply capacitor in a modern TV is rated for almost exactly what the circuit demands, with minimal margin for error.

This approach works fine in a controlled environment. But real-world conditions are never controlled. A power surge. A dusty environment that restricts airflow and raises operating temperatures by 10 degrees. A manufacturing tolerance that produces a slightly weaker component. Any of these can push that capacitor past its rating, and it fails. Not catastrophically, but permanently.

The Death of Thermal Design

When you open up a vintage CRT television from the 1980s, you notice something immediately: there's space. Components are spread out. Air can move freely around the power supply. The picture tube isn't packed against other hot components. Heat dissipation was treated as a first-class design requirement.

A modern 55-inch LCD television is often less than 3 inches deep. Everything is crammed as tightly as possible. The power supply is a small brick. The main circuit boards are stacked in layers separated by a few millimeters. LED backlights generate heat. The processing chips generate heat. Everything is operating in an environment where air circulation is minimal and temperatures rise significantly.

Electronics don't fail from heat just above their rated temperature. They fail from cumulative stress. A circuit board rated for 105 degrees Celsius that operates at 95 degrees will last decades. The same board operating at 85 degrees but with constant thermal cycling (turning on and off, heating and cooling) might fail in five years. The stress isn't from absolute temperature but from repeated expansion and contraction.

Modern TVs, especially budget models, operate at higher temperatures in more constrained spaces. This accelerates component aging. A capacitor in a vintage TV operating at 60 degrees Celsius might last 40 years. A similar capacitor in a modern TV operating at 80 degrees Celsius, even at identical voltage stress, will last maybe 10 years.

Vintage electronics prioritized high stress tolerance and reliability margins, while modern electronics focus on cost efficiency and manufacturing consistency. Estimated data.

The Repairability Collapse: From Modular to Monolithic

If something broke in that 39-year-old Philips CRT, repair was often straightforward. The deflection circuits were separate modules. The power supply was a distinct assembly. The video processing circuits occupied their own board. If the power supply failed, you could order a replacement module for $50-100, unplug a few connectors, and have a working TV again.

Modern televisions abandoned this modularity. The power supply, video processing, LED backlighting, and panel control are all integrated into a single circuit assembly. There are no plug connectors between major systems. Everything is soldered directly to the main board. If the power supply fails, you need to replace the entire main board, which costs $300-500 if replacement parts are even available.

Manufacturers justify this by claiming cost savings. A modular design requires more connectors, more documentation, more testing between modules. An integrated design is cheaper to manufacture. But it's only cheaper if you're buying a new TV when the old one fails. If you're trying to repair it, integrated design is catastrophically expensive.

The Solder Joint Problem

Vintage electronics used through-hole components: a metal lead was pushed through a hole in the circuit board and soldered on the other side. These connections are mechanically strong and electrically reliable. They survived decades of vibration, temperature cycling, and physical stress.

Modern devices use surface-mount technology: tiny components are placed on the surface of the circuit board and soldered in place. This allows for much denser packing and cheaper manufacturing. A component footprint that took up a quarter-inch of board space in 1985 might take up a sixteenth of an inch today.

But surface-mount solder joints are fragile. Thermal cycling causes the circuit board material to expand and contract at a different rate than the solder connections. This creates microscopic cracks in the solder joints. After thousands of thermal cycles (turning the TV on and off, heating and cooling), these micro-cracks grow. Eventually, a connection fails intermittently, then completely.

This phenomenon is called "thermal fatigue." It's not a manufacturing defect. It's an inevitable consequence of surface-mount technology used in devices that experience regular thermal cycling. A device that's powered on and off daily will experience this failure mode. A device that stays on constantly might last longer. But the engineering is brittle by design.

Manufacturing Cost Pressures: The Race to the Bottom

Why did this transition happen? It wasn't because engineers in 2000 suddenly became worse at their jobs than engineers in 1980. It's because the economics of consumer electronics changed fundamentally.

In the 1980s, televisions were expensive enough ($400-800 in today's money) that manufacturers had strong incentives to make them reliable. Warranty costs mattered. Customer satisfaction mattered. A company that shipped TVs with a 3% failure rate gained a reputation for reliability and outsold competitors.

By the 2000s, television prices had collapsed. A decent-quality 42-inch LCD was

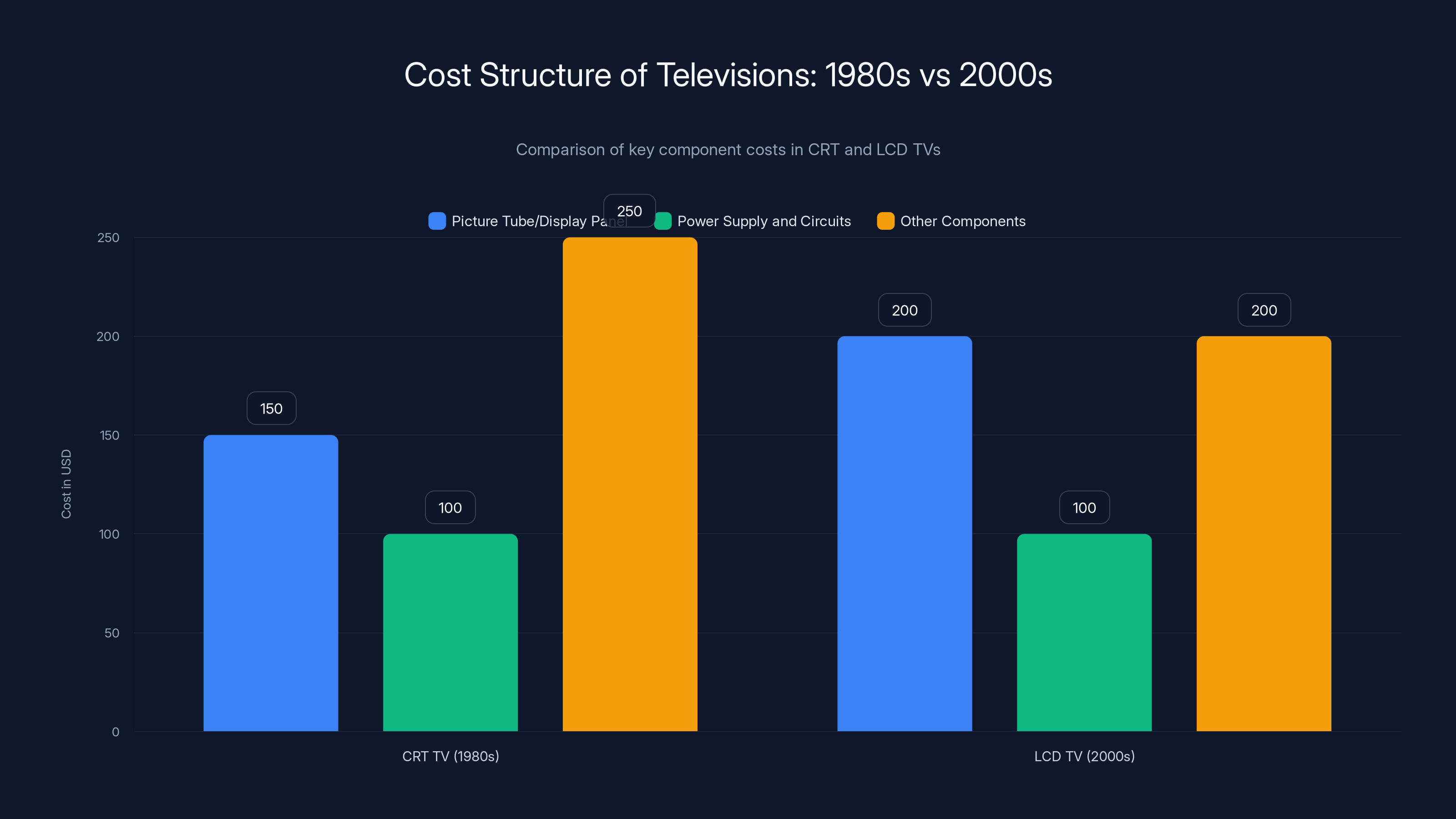

The cost structure of a CRT television was dominated by the picture tube and the power transformer. These were expensive, robust, and built to last. The CRT alone cost maybe

In a modern LCD television, the display panel costs maybe 30-40% of the retail price. But most of that value is in volume and manufacturing scale, not in the panel itself. The power supply, circuits, and backlighting together might represent

The Component Lottery

When you manufacture millions of TVs, you source components from dozens of suppliers. A particular model might use capacitors from three different manufacturers, depending on which factory is shipping that week. In the era of over-specification, this didn't matter. All the capacitors met the spec, and they were all over-specified, so variations didn't cause failures.

Modern just-in-time manufacturing optimizes for cost, not robustness. If capacitor supplier A is offering 100-microfarad, 105V capacitors for 12 cents and supplier B is offering the same spec for 14 cents, you buy from supplier A. Both meet the spec. Both should theoretically perform identically.

But real-world manufacturing tolerance means they don't. Supplier A's capacitors might have slightly higher internal resistance. They might age slightly faster. Over the course of a TV's life, that 2-cent difference in component cost leads directly to a failure at year 5 instead of year 15. The manufacturer saves $40 per unit in component costs. The customer buys a new TV at year 5 instead of year 15.

Who benefits? The component manufacturer (gets paid twice as often), the TV manufacturer (gets paid twice as often). Who loses? The customer pays twice as much per year of usable life.

In the 1980s, CRT TVs had a significant cost attributed to the picture tube, while in the 2000s, LCD TVs saw a shift with the display panel and manufacturing scale dominating costs. Estimated data.

Firmware and Software Obsolescence: The Invisible Killer

Vintage electronics failed through physical component degradation. There was no firmware to stop working. No software updates that broke compatibility. No cloud services that got shut down. You could still watch TV on that 39-year-old Philips the same way you watched TV on day one.

Modern televisions fail in ways their owners never anticipated. Streaming apps stop working because they require features that older processors can't handle. Firmware updates become unavailable, and unpatched security vulnerabilities prevent the TV from connecting to Wi-Fi. Operating systems are deprecated, and the hardware underneath becomes incompatible with new standards.

You buy a Samsung TV in 2018. It has a Tizen operating system. In 2024, Samsung stops supporting that operating system on older models. New app versions require a newer OS. The TV still works, but it's increasingly isolated from the streaming services and features you want to use. By year 7-8, the TV is practically obsolete for its primary purpose: streaming content.

This isn't a hardware failure. The circuits still work. The display still displays. But the software that breathes life into the hardware becomes incompatible with the modern ecosystem. Manufacturers have no incentive to maintain backward compatibility. Instead, they have incentive to push users toward newer hardware.

Update-Induced Failures

Even worse, the updates themselves can cause hardware to fail faster. As applications become more demanding and operating systems become more resource-heavy, older hardware struggles. A software update that requires more RAM, more storage, or more processing power might cause a TV that was perfectly usable to start stuttering, crashing, or behaving erratically.

The TV technically still works, but the user experience degrades so much that the TV becomes unusable. This is effectively a death sentence from the user's perspective. The hardware is fine, but the software makes the hardware worthless.

The Display Panel Lifespan Question: LED vs. CRT

One argument often made in favor of modern TVs is that old CRTs had a limited lifespan: the cathode would eventually fail, and the picture tube would become unusable. This is true. A CRT's usable life was often 20,000 to 40,000 hours of operation, depending on the tube quality.

But here's the catch: LED-backlit LCD panels also have limited lifespans. The LEDs that provide backlighting degrade over time. After 30,000 to 50,000 hours of operation, brightness drops to 50% of the original level. The panel gradually loses color accuracy. The image quality deteriorates even if nothing has technically "failed."

The difference is that a CRT failure was total and obvious: the picture tube stopped working, and you had to get a new TV. An LED backlight failure is gradual. The picture slowly becomes dimmer and less vibrant. The TV is still technically functional, but it's noticeably worse.

From the perspective of user satisfaction, gradual deterioration is actually worse than sudden failure. With sudden failure, you have a clear decision point: buy a new TV or repair it. With gradual deterioration, you're stuck with a progressively worse viewing experience, and there's no clear moment to make the replacement decision.

Modern TVs exploit this ambiguity. You keep the TV longer because it still works, even though its picture quality is deteriorating. Eventually, you get frustrated with the poor picture and replace it. The TV didn't fail. It just became too unpleasant to use.

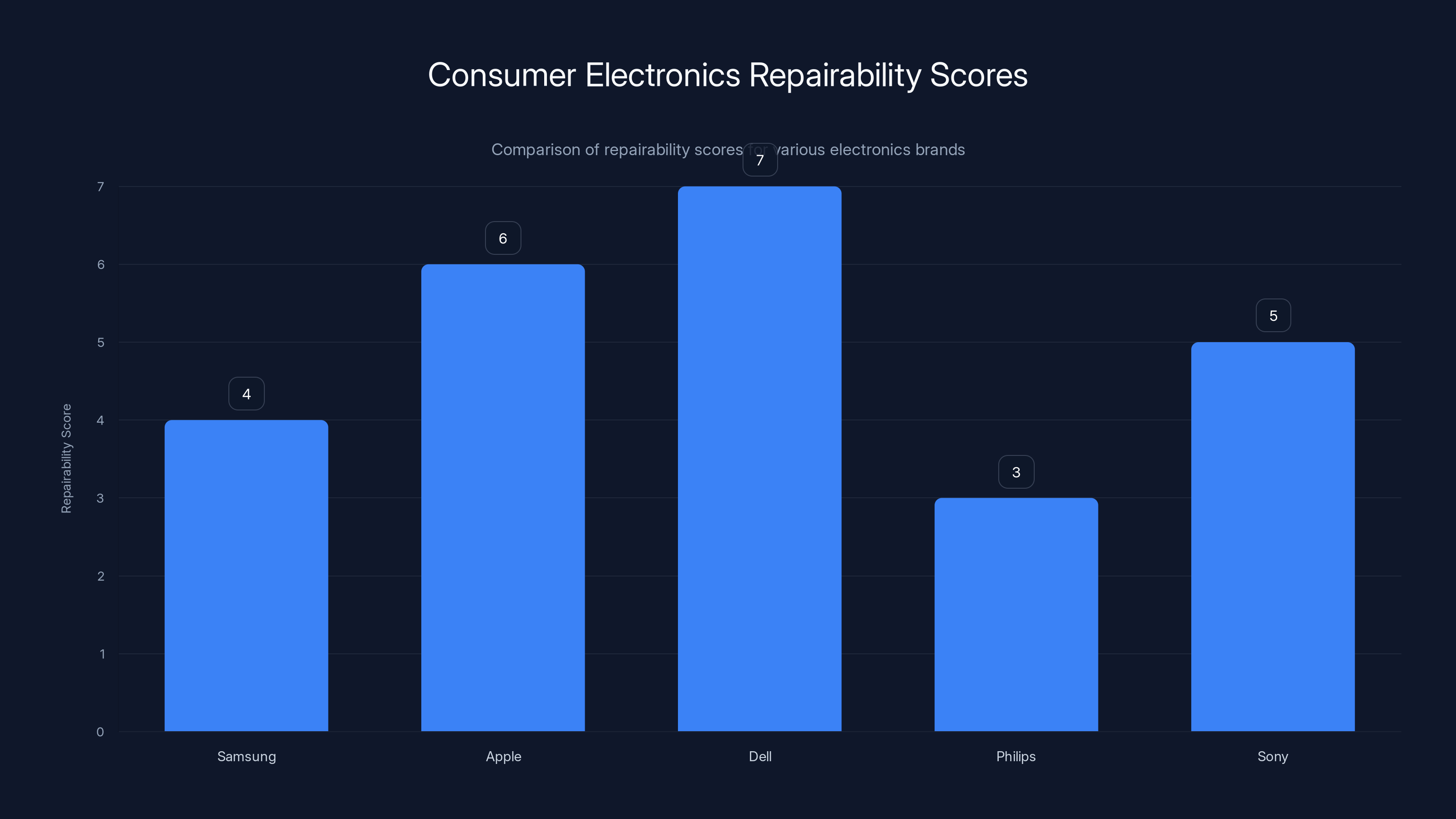

Estimated data shows varying repairability scores among popular electronics brands, with Dell leading in repairability. Estimated data.

The Right-to-Repair Movement: Fighting Back

The gap between that 39-year-old Philips and a modern Samsung TV hasn't gone unnoticed. A right-to-repair movement has emerged, demanding that manufacturers design products to be repairable and provide access to replacement parts.

The movement has scored some victories. The U. S. Federal Trade Commission has become increasingly hostile to repair restrictions. In 2023, the FTC issued new rules requiring manufacturers to provide spare parts and repair documentation. Some states, particularly New York, have passed legislation requiring repairability.

But the movement faces structural resistance. For manufacturers, repairability is a cost. For designers, it means building modular systems, making components replaceable, standardizing parts. For marketing, it means admitting that your product might need repair, which undermines the aspirational messaging that newer is always better.

Repairability Scores and Standards

Organizations like i Fixit have created repairability scores that rate consumer electronics based on how easy they are to repair. These scores have gained significant media attention and influence purchasing decisions. A 10-year-old TV with a repairability score of 3/10 communicates something powerful: this device is designed to be thrown away, not fixed.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: repairability costs money. Adding replaceable modules, standardized connectors, and modular designs increases manufacturing costs by 5-10%. In a market where products are sold on price, that cost increase is a competitive disadvantage.

The only way repairability becomes standard is if consumers demand it and are willing to pay for it, or if regulations mandate it. The right-to-repair movement is building momentum, but it's fighting decades of momentum in the opposite direction.

Supply Chain Consolidation: The Monopoly on Repair

Suppose you need to replace a failed power supply in a 2010s-era Samsung TV. You discover something depressing: Samsung doesn't sell replacement power supplies to consumers. They're only available to authorized repair centers. Even if you can find the schematic and identify the exact component that failed, you can't buy a replacement.

Why? Because Samsung has decided to consolidate repair into a controlled channel. Authorized repair centers charge significantly more than self-service repair would cost, but Samsung benefits from higher margins on repair services. More importantly, authorized repair centers direct customers to replacement units when repair becomes too expensive.

This strategy maximizes revenue per customer: first sale of the TV, second sale of the repair service (at inflated prices), third sale of the replacement TV when repair becomes too expensive. The profit opportunity from replacement exceeds the profit opportunity from repair.

Parts Availability and Manufacturing Discontinuation

Manufacturers discontinue production of replacement parts almost immediately after a model goes out of production. A TV model produced for 2 years has replacement parts available for maybe 1-2 years after the last unit is manufactured. After that, spare parts become unavailable.

This is partly logistics and cost-related: storing millions of SKUs of replacement parts is expensive. But it's also intentional. By limiting parts availability to a narrow window, manufacturers ensure that any significant failure requires a complete replacement, not a component-level repair.

Compare this to the 39-year-old Philips CRT, for which replacement components were sourced from generic manufacturers. A failed power transformer could be replaced with a new one from any industrial electronics supplier. A failed capacitor could be replaced by a technician. The TV wasn't dependent on Philips continuing to manufacture spare parts.

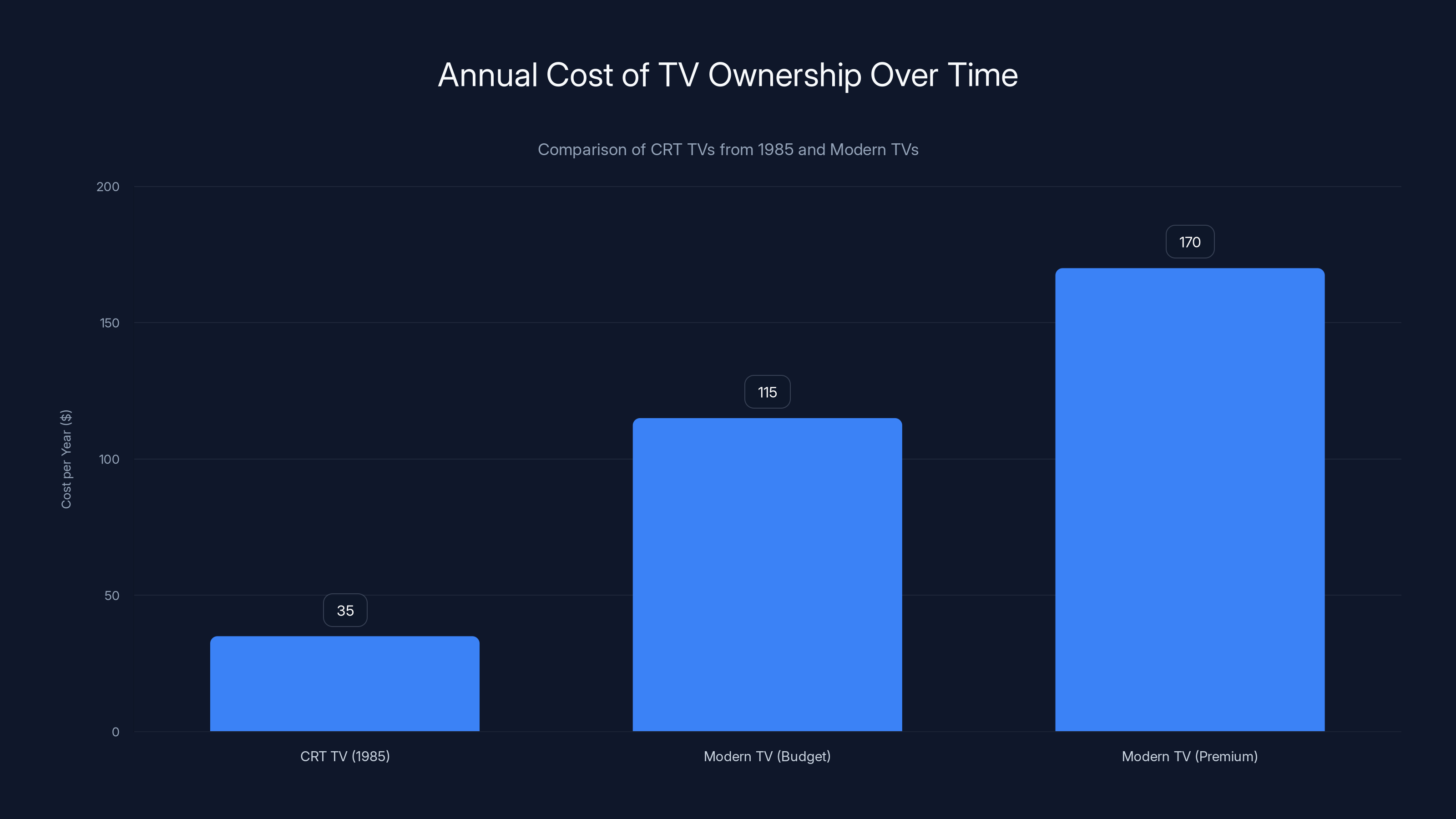

The annual cost of owning a modern TV is significantly higher than a CRT TV from 1985, with modern TVs costing 3-4 times more per year. Estimated data based on inflation-adjusted values.

Environmental Impact: E-Waste and Hidden Costs

The shift from durable to disposable has environmental consequences that rarely appear on the balance sheet of any individual manufacturer.

Extraction of raw materials for electronics is environmentally destructive. Mining copper, gold, silver, rare earth elements, and other materials requires enormous amounts of energy and water. Refining these materials produces toxic waste. A television contains about 0.34 grams of gold, 0.34 grams of silver, and 0.015 grams of platinum, along with copper, aluminum, and rare earth elements.

If that TV lasts 39 years, the environmental cost of material extraction and processing is amortized over 39 years of use. If it lasts 5 years, the same environmental cost is amortized over 5 years of use. The TV from 2018 that's already dead in 2025 required roughly the same environmental input as the TV from 1985 that's still working in 2024. But the environmental cost per year of useful life is roughly 8 times higher.

Manufacturing and transportation also create environmental costs. A TV shipped from the factory to the retailer to the customer and then to the landfill creates carbon emissions at each step. If the TV lasts 5 years instead of 40 years, the per-year carbon cost increases by a factor of 8.

E-waste disposal adds further environmental costs. When a TV ends up in a landfill, lead, mercury, and cadmium from failed components leach into groundwater. Even when e-waste is "recycled," the process requires energy and creates pollution.

From a pure environmental standpoint, the 39-year-old TV that still works is vastly superior to the modern TV designed to fail in 7 years. Not because modern TVs use more electricity (they actually use less), but because the manufacturing and disposal environmental costs are amortized over a much shorter period.

Consumer Economics: The Real Cost of Ownership

Let's do some math. A quality CRT television in 1985 cost

A decent modern TV costs

For equivalent real (inflation-adjusted) spending, you could buy a new TV every 2-3 years, or you could own one TV for 35+ years. The modern approach costs roughly 3-4 times as much per year of useful life.

Why doesn't this matter more in consumer psychology? Partly because we don't think about true cost of ownership. We see a

Partly also because consumer preferences have shifted. A modern TV is demonstrably better in many ways: higher resolution, better color, thinner, lighter, integrated smart features. Even if it lasts a quarter as long, some consumers feel the superior experience during the years it works justifies the higher cost per year.

But that calculation is personal and subjective. The financial reality is clear: durable products have lower total cost of ownership than frequently-replaced products, regardless of the quality experience during the usable life.

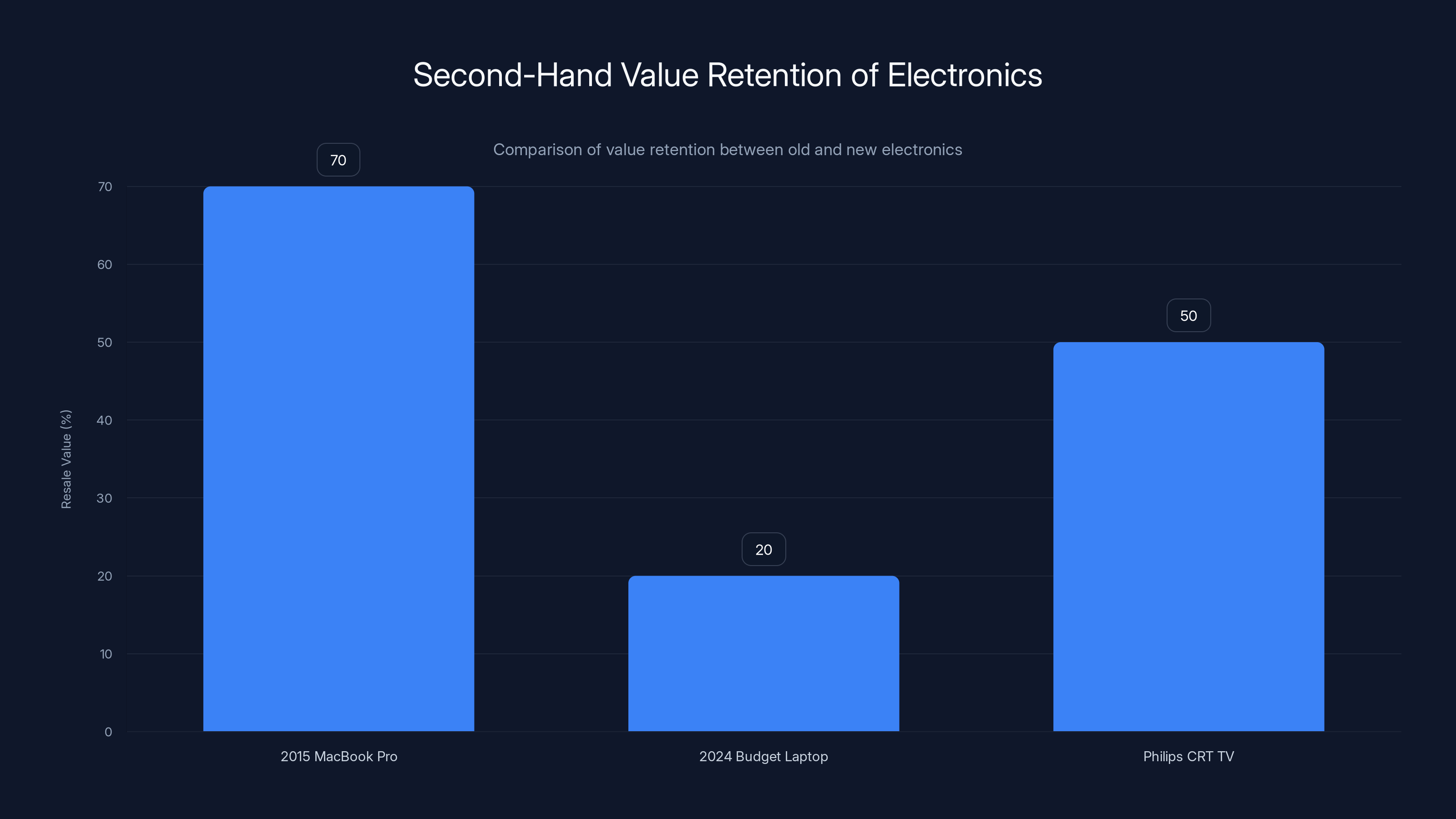

Estimated data shows that older electronics like a 2015 MacBook Pro retain a higher resale value (70%) compared to newer budget laptops (20%), highlighting the economic advantage of durable products.

The Business Case for Durability: Why It Doesn't Make Economic Sense

Here's the economic paradox: if durable products have lower total cost of ownership, why don't manufacturers compete on durability? Why don't we see companies advertising "this TV will last 30 years"?

Because from the manufacturer's perspective, durability is a competitive disadvantage. If you sell a customer a TV that lasts 30 years, that customer doesn't buy a TV for 30 years. If a competitor sells a TV that lasts 5 years, that competitor sells 6 TVs in the same 30-year period. Six sales versus one sale. At any reasonable profit margin, 6 sales is better than 1 sale.

For a manufacturer to choose durability, they'd have to accept lower total revenue. This is viable only if:

- They can charge significantly more per unit for the durability advantage

- They can build a brand strong enough that durability becomes a sufficient selling point

- Regulations force durability on all competitors simultaneously

None of these conditions are typically met. Consumers choose TVs based on specs and price, not durability. Durability isn't an easily marketable feature. And regulations that mandate durability are rare and face intense manufacturer lobbying.

From an individual manufacturer's perspective, designing a TV to last 30 years while competitors design TVs to last 5 years is suicide. You'll be outcompeted on price because your costs are higher, and you'll get outsold on volume because you're making a tenth as many sales.

The market structure creates a prisoner's dilemma. Every manufacturer would benefit if all manufacturers made durable TVs, but each individual manufacturer benefits most from making disposable TVs while others make durable ones. The only escape from this trap is government regulation that levels the playing field.

Manufacturing Innovation: Cheaper Isn't Better

It's worth noting that the shift toward disposable products isn't because manufacturing technology got worse. It got better in many ways. Computer-aided design, surface-mount technology, automated assembly, and supply chain optimization are all genuine innovations that reduce costs and increase precision.

The tragedy is that these innovations were applied exclusively toward reducing cost, not improving durability. A surface-mount component is more cost-effective than a through-hole component, so manufacturers switched. The fact that it's also more fragile under thermal cycling wasn't considered a priority.

An integrated power supply is cheaper than a modular power supply, so manufacturers integrated it. The fact that this makes repair impossible wasn't a consideration.

These weren't engineering failures. They were conscious choices driven by economic pressure. Engineers could design a modern TV to last 20 years using available technology. It would cost $200-300 more to manufacture. That's not technically impossible. It's economically implausible given the market structure.

The Emerging Second-Hand Market: Revaluating Old Electronics

The durability gap has created an interesting economic phenomenon: the second-hand market for electronics is thriving. Old laptops, cameras, and phones are now valuable. Not because of nostalgia, but because they often work better than new cheap products.

A Mac Book Pro from 2015 is more repairable, more durable, and more reliable than a

This creates a fascinating market dynamic: as new products become more disposable, old products become more valuable. The person who bought that Mac Book in 2015 and took care of it now has a more valuable asset than someone who bought a new laptop in 2024 for the same price.

Similarly, that 39-year-old Philips CRT was probably more valuable on the second-hand market as a novelty than it was worth as a TV. But the principles underlying its durability are universally applicable. Build with redundancy. Design with thermal margin. Use modular, repairable architecture. Test extensively before release.

These principles make modern products more expensive and slower to bring to market. But they result in products that retain value instead of becoming electronic waste within half a decade.

Regulatory Trends: The Beginning of Change

Government agencies have started taking the durability question seriously. The European Union has led the way with right-to-repair directives and requirements for spare parts availability. France has adopted "repairability scores" similar to energy ratings, making product durability visible to consumers at the point of purchase.

The U. S. Federal Trade Commission has become increasingly active on the right-to-repair front. In 2023, the FTC issued statements supporting manufacturers' rights to repair their own devices and opposing artificial restrictions on third-party repairs.

These regulations are still nascent and often face industry pushback. But they represent a significant shift in policy. Instead of assuming that manufacturer profit maximization serves the consumer interest (via price competition), regulators are increasingly recognizing that durability and repairability are consumer interests that might require protection.

It's unlikely that regulation will swing all the way to mandating 30-year product lifespans. But standards that require manufacturers to support products for 8-10 years, provide spare parts for that duration, and design products to be repairable are plausible in the next few years.

Future Outlook: The Potential for Change

Will we ever see another TV like that 39-year-old Philips that gets traded in after nearly four decades of use? Not if the current economic incentives remain unchanged. But several factors could shift those incentives.

Environmental Cost Internalization

If governments impose carbon taxes or landfill fees that reflect the true environmental cost of electronic waste, the economics of durability change fundamentally. Suddenly, a manufacturer that designs products for 30-year lifespans has a cost advantage, not a disadvantage. A manufacturer creating more e-waste has real costs to bear.

This isn't theoretical. The EU's landfill taxes have already made durability more economically attractive to European manufacturers. As other jurisdictions adopt similar policies, the global economics will shift.

Consumer Awareness and Market Segmentation

As durability becomes a visible, comparable metric (thanks to regulations like France's repairability scores), consumers can make informed choices. This creates a market segment: people who value durability and are willing to pay for it.

Currently, that segment barely exists because durability isn't visible. But if a TV's repairability score is displayed as prominently as its energy rating, consumer behavior will shift. Companies will compete on durability because consumers will choose them.

Technology Maturation

Current technology is as good as it will be for most consumer use cases. You don't need a faster processor or higher resolution display every year. This maturation makes it possible to sell products based on durability rather than constant innovation.

When a device is built to last 10 years, it needs to be enough, not perfect. Innovation can happen more slowly. This makes the business case for durability much stronger.

What the Guatemalan Family's TV Teaches Us

The 39-year-old Philips CRT that shocked Samsung isn't a symbol of how much better "the old days" were. It's a data point about what's possible when products are designed to last instead of designed to fail.

The family that owned it probably replaced it not because it stopped working, but because newer TVs offered features they wanted. The CRT probably could have worked for another decade. But at some point, technological advancement made the old TV obsolete, even if it still technically functioned.

This is the future we should aim for: products that last long enough to outlive consumer preferences, that can be repaired when something breaks, that lose value when they stop being useful, not when they stop working. It's not inevitable. It's a choice that regulators, manufacturers, and consumers will make together.

The economics point in one direction (disposable products that maximize sales volume). Consumer interests point in another (durable products with lower total cost of ownership). Regulators are beginning to align incentives so that what's good for consumers is also good for manufacturers. It's slow, and it's not certain, but it's happening.

That 39-year-old TV is proof that better was possible. The question is whether we're willing to make it happen again.

FAQ

What is planned obsolescence?

Planned obsolescence refers to the deliberate design of products to have limited useful lifespans, either through component failure, incompatibility with new standards, or repairability barriers. It can be intentional (engineering weak points specifically to cause failure) or indirect (making design choices that prioritize cost and manufacturing efficiency over longevity). Most modern planned obsolescence is indirect rather than intentionally malicious.

Why do modern TVs fail faster than old CRT televisions?

Modern TVs fail faster due to several factors: components are specified as close as possible to their maximum ratings with minimal safety margin, thermal design is inadequate with components packed tightly with poor airflow, surface-mount solder joints are fragile under thermal cycling, and manufacturing prioritizes cost reduction over durability. Additionally, software obsolescence (operating systems no longer supported) makes devices practically unusable before hardware fails.

How long should a modern television last?

A typical modern LCD television is designed to last 5-7 years before experiencing significant component failures. Some premium models may last 8-10 years. This compares to CRT televisions that commonly lasted 30-40 years or more. The difference is primarily due to engineering philosophy and design priorities rather than manufacturing defects. A TV that lasts 7 years isn't necessarily defective; it's designed that way.

Can I repair my modern TV, or is it designed to be unrepairable?

Most modern TVs are designed to be irreparable at the component level. The power supply, video processing circuits, and backlighting are soldered into a single main board. If any component fails, you need to replace the entire board, which often costs $300-500 or more. Replacement parts are typically unavailable to consumers; they're sold only through authorized repair centers. Some manufacturers are starting to change this due to right-to-repair regulation, but most current models remain effectively irreparable.

What is the true cost of ownership for a television over its lifetime?

A CRT television purchased in 1985 for

Why don't manufacturers compete on durability if it results in lower customer costs?

From a manufacturer's perspective, durability is a competitive disadvantage. A company that makes TVs lasting 30 years sells one TV per customer per 30 years. A competitor making TVs lasting 5 years sells six TVs per customer per 30 years. Six sales with profit is better than one sale with profit, even if each sale is more profitable. The market structure creates incentives for disposability, not durability, unless regulations force change.

How can I make my television last longer?

Provide adequate ventilation around the TV (don't block the vents), keep it in a cool environment (heat accelerates component aging), avoid frequent power cycling (thermal stress from heating and cooling degrades solder joints), use a quality power strip with surge protection, and keep the TV clean of dust (dust restricts airflow and increases operating temperature). These practices won't transform a five-year TV into a thirty-year TV, but they can extend useful life by 1-2 years.

What is the right-to-repair movement, and how does it affect consumers?

The right-to-repair movement advocates for consumers' legal right to repair products they own, requiring manufacturers to provide spare parts and repair documentation. Recent gains include FTC statements supporting repair rights and EU regulations mandating spare parts availability and repairability standards. As regulations take effect, consumers will have increasing ability to repair devices rather than replace them, which reduces both costs and environmental waste.

Are vintage electronics worth buying secondhand if they're older?

Some vintage electronics, particularly from manufacturers known for durability (like older Mac Books or professional equipment), retain significant value and utility. A 10-year-old product built to high durability standards is often more repairable and reliable than a new budget product built to minimize cost. However, older electronics may lack features, have reduced battery capacity (if applicable), and lack compatibility with modern software standards. Evaluate based on your specific needs rather than assuming older automatically means better.

What environmental impact does short-lived electronics have?

Short-lived electronics multiply the environmental cost of manufacturing and disposal. Raw material extraction, refining, manufacturing, and transportation create environmental costs regardless of how long the product lasts. A TV lasting 5 years instead of 35 years multiplies these costs by a factor of 7. Additionally, e-waste disposal contributes lead, mercury, and cadmium to landfills and groundwater. From an environmental perspective, durable products vastly outperform frequently-replaced products.

What are repairability scores, and how do they influence my purchasing decision?

Repairability scores (like i Fixit's ratings) rate how easy a device is to repair on a scale, typically 1-10. They consider factors like ease of opening the device, availability of replacement parts, necessity of specialized tools, and component modularity. As these scores become more visible through regulation (France requires repairability scores on consumer electronics), they influence purchasing decisions. A TV with a repairability score of 8/10 will likely last longer in real-world use because repair is feasible, while a 2/10 rating indicates a device designed for replacement rather than repair.

Key Takeaways

- CRT televisions lasted 30-40+ years due to over-specified components, redundant design, and generous thermal margins, while modern TVs fail in 5-7 years from exact-specification components and inadequate thermal design

- Modern electronics use surface-mount technology and integrated circuits that are cheaper to manufacture but fragile under thermal cycling, causing failures that would be impossible in through-hole designs

- Integrated, non-modular design makes modern electronics irreparable at component level, forcing complete replacement when single components fail, whereas vintage electronics had replaceable modules

- The economics of television manufacturing incentivize disposability: a manufacturer selling 6 short-lived TVs generates more profit than selling 1 long-lived TV, even though consumers pay more per year of usable life

- True cost of ownership analysis shows modern TVs cost 2-3 times more per year than vintage alternatives, and environmental impact is multiplied 7-8 fold when products last 5 years instead of 35 years

- Right-to-repair regulation and repairability scoring are beginning to shift incentives toward durability, though manufacturer resistance remains strong due to lost revenue from reduced replacement sales

Related Articles

- Why Palmer Luckey Thinks Retro Tech is the Future [2025]

- Bose Open-Sources SoundTouch Speakers: How to Keep Them Alive [2025]

- Bose Open-Sources SoundTouch Speakers: A Better Way to Kill Products [2025]

- Wearable Health Devices & E-Waste Crisis by 2050 [2025]

- Nvidia RTX 5070 Ti Repair & 8K Benchmark Record [2025]

- Apple Patches Ancient iOS Versions to Keep iMessage Alive [2025]

![Why They Don't Make Them Like They Used To: The Collapse of TV Manufacturing [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-they-don-t-make-them-like-they-used-to-the-collapse-of-t/image-1-1770584750449.jpg)