Winter Dehumidifiers: A Complete Guide to Pros, Cons, and Real-World Usage

Winter hits, the heating kicks on, and suddenly your home feels like the Sahara. You reach for a humidifier, but then you wonder: should I actually be using a dehumidifier instead? Or worse, maybe you're thinking about running both at the same time?

Here's the thing: most people get this backwards. Winter dehumidifier use isn't about whether the device works. It's about whether you actually need to run it, where you need it, and whether the energy cost justifies the benefit.

I've been testing home climate control equipment for years, and the winter dehumidifier question comes up constantly. People buy these devices thinking they'll solve every moisture problem, then they end up confused about when to use them. The marketing doesn't help. Most dehumidifier manufacturers make it sound like you need one running 24/7, in every room, regardless of season.

That's not how real homes work.

This guide breaks down the actual science of winter humidity, shows you when dehumidifiers actually help (and when they're a waste of electricity), explains the real trade-offs, and gives you a framework for deciding if one makes sense in your specific situation. We'll look at the energy costs, the health implications, the maintenance headaches, and the situations where dehumidifiers genuinely shine during winter months.

Let's start with the uncomfortable truth: most homes don't need a dehumidifier in winter at all. But some do. And if yours is one of them, it'll change your comfort and air quality dramatically.

TL; DR

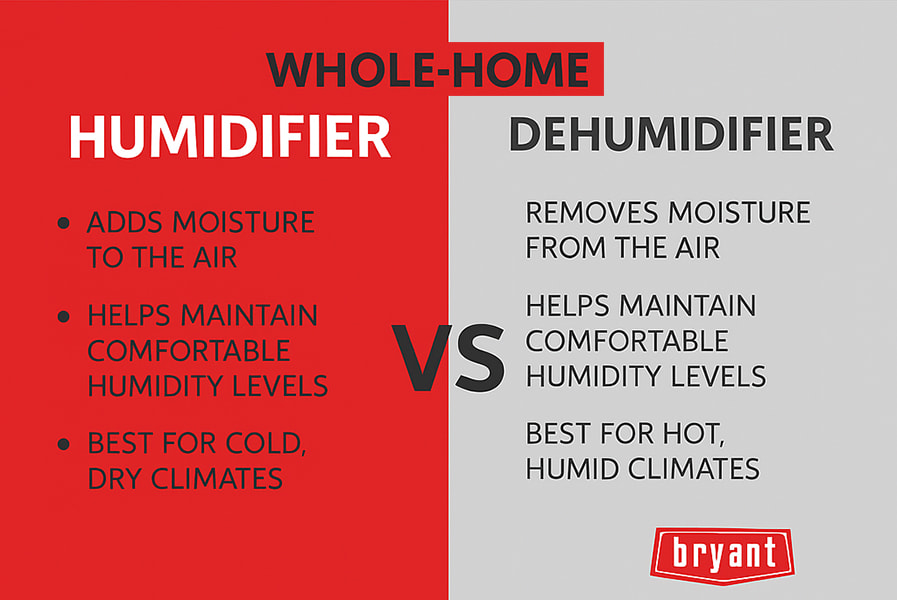

- Winter humidity is rarely the problem: Most homes actually need humidifiers in winter, not dehumidifiers, because heating systems dry out air

- Basements are the exception: Below-grade spaces trap moisture and often genuinely benefit from dehumidification year-round

- Energy costs matter: Running a dehumidifier in winter can add $20-40/month to your electricity bill depending on capacity and runtime

- Location determines necessity: Humid climates near coastlines, or homes with moisture intrusion issues, are the main candidates for winter use

- Health trade-off exists: While removing excess moisture prevents mold, over-dehumidifying causes respiratory irritation and worsens winter dryness

- Basement dehumidifier systems make the strongest case: If you have a finished basement that stays moist despite winterization efforts, automated dehumidification saves repair costs and improves habitability

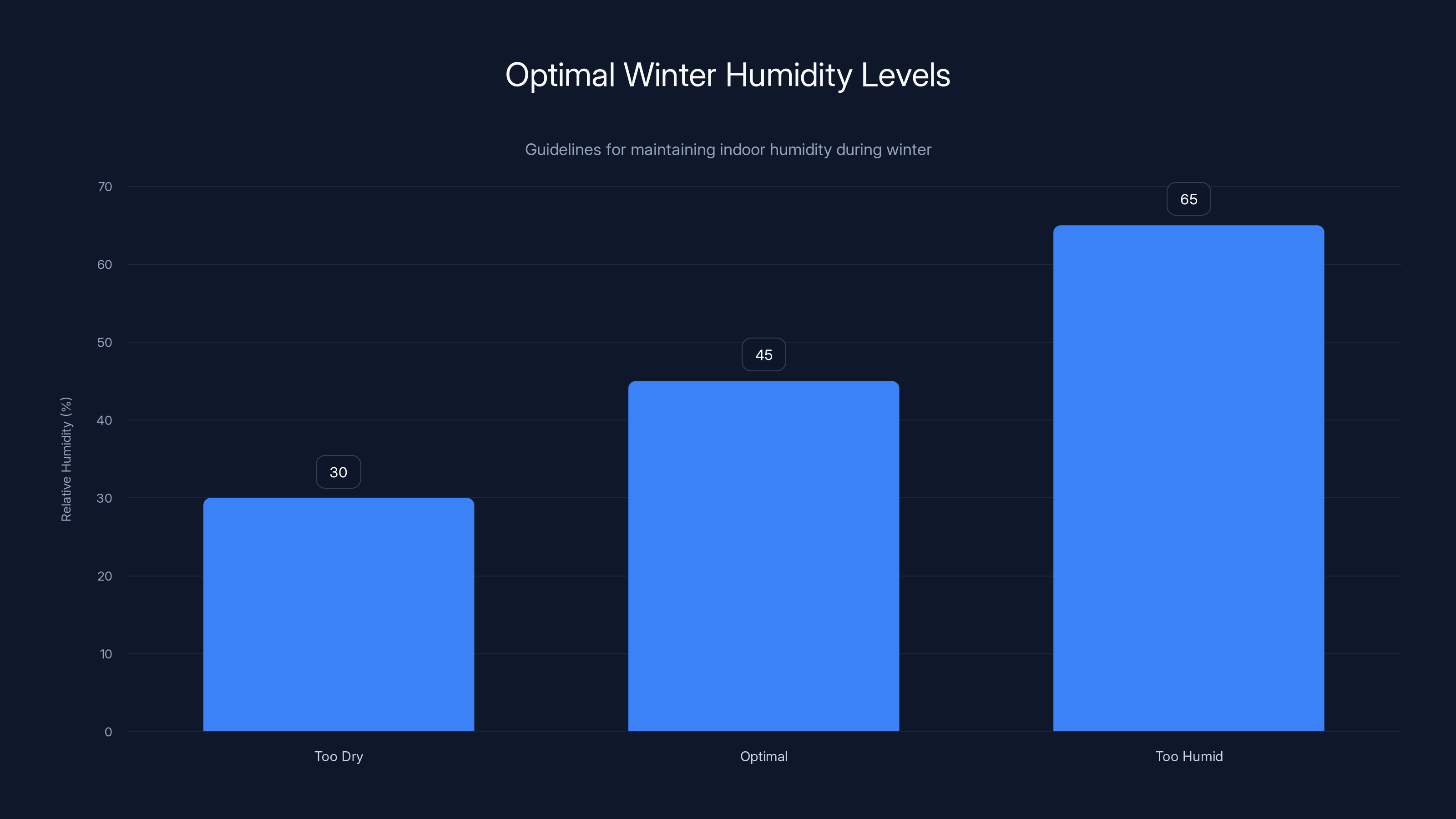

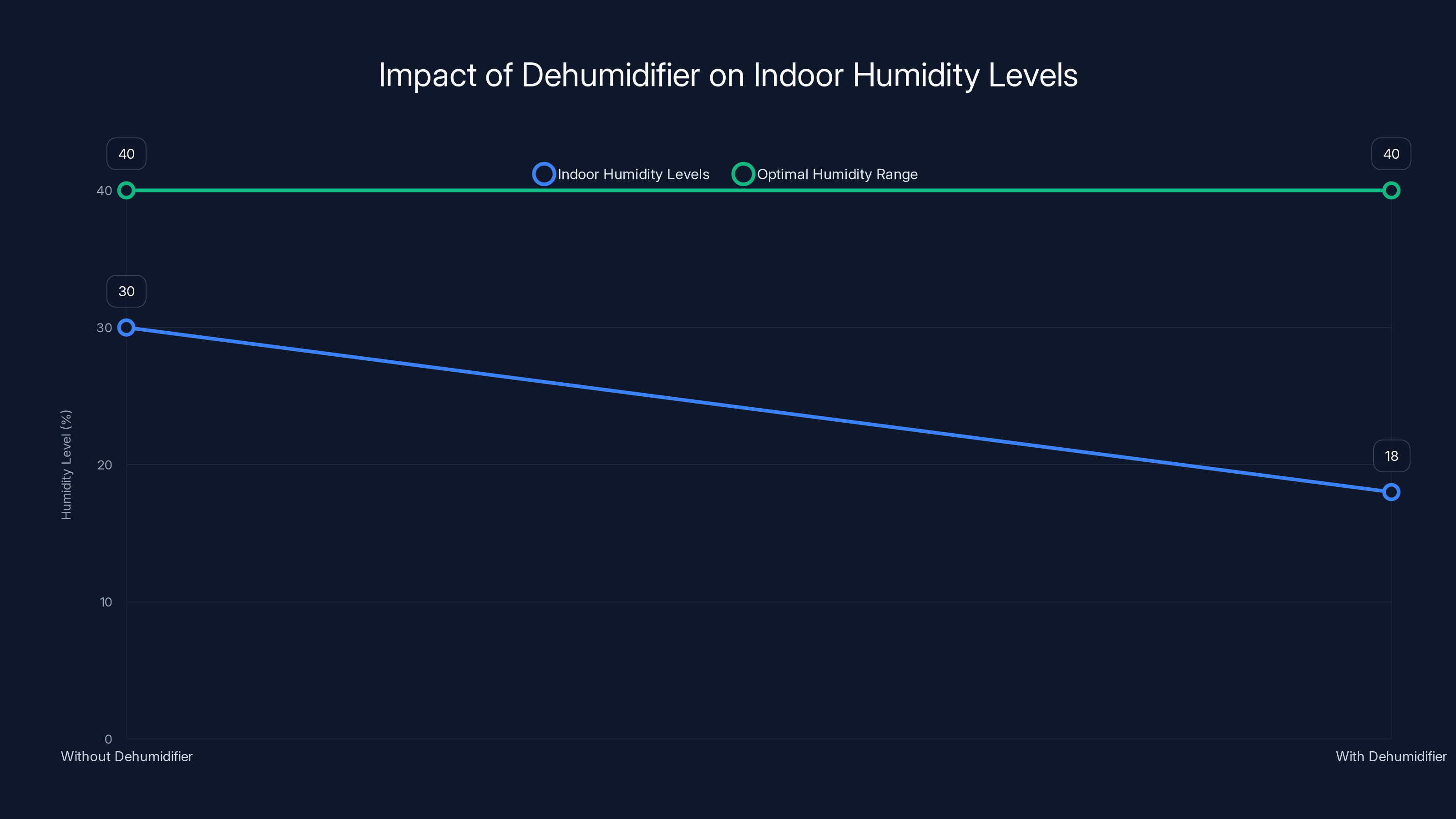

Maintaining indoor humidity between 40-60% is ideal in winter. Below 40% can cause dryness, while above 60% increases mold risk.

Understanding Winter Humidity: The Physics Behind It

Before you buy a dehumidifier or turn one on, you need to understand what's actually happening with moisture in your home during winter. This isn't complicated, but it's the foundation for every decision that follows.

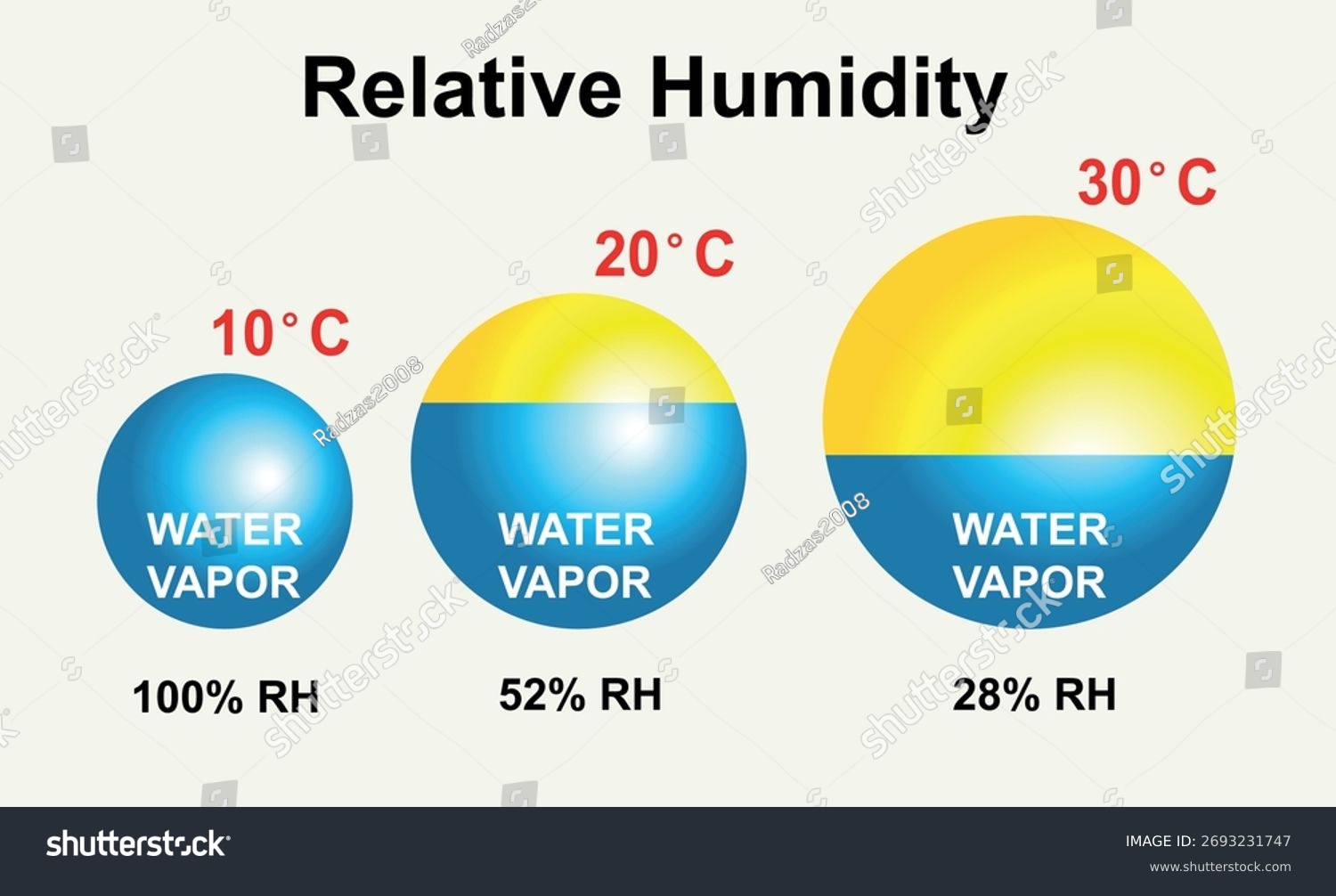

Winter air is cold. Cold air holds significantly less moisture than warm air. This is straightforward physics. The same cubic meter of air at 32°F can hold roughly 50% less water vapor than that same air at 70°F. This is called the saturation point, and it's crucial.

Now here's where people get confused: when you heat cold outdoor air to indoor room temperature, something important happens. That air warms up, but the actual amount of water vapor in it stays the same. The result? Your indoor air becomes drastically drier. A room that's comfortable at 50% relative humidity becomes dangerously dry at the same absolute moisture content.

This is why winter causes dry skin, chapped lips, static electricity shocks, and respiratory irritation. The heating system pulls moisture right out of the environment.

So the question becomes: where does winter humidity actually come from if heating is constantly drying things out?

Moisture sources in winter homes:

Showers and baths are the biggest contributors. A single 20-minute shower produces roughly 1-2 liters of water vapor. Your kitchen generates moisture too, especially if you cook multiple meals daily. Laundry, dishwashers, and even the respiration of people living in the home all add moisture. A family of four breathing and living normally can generate 10-15 pounds of water vapor daily.

But here's the critical part: most modern homes vent bathrooms and kitchens directly outdoors through exhaust fans. Those systems are designed to remove moisture before it settles into walls and create problems. If your ventilation is working properly, you're removing that moisture automatically.

Problems arise when ventilation fails or when moisture can't escape. That's where dehumidifiers enter the equation.

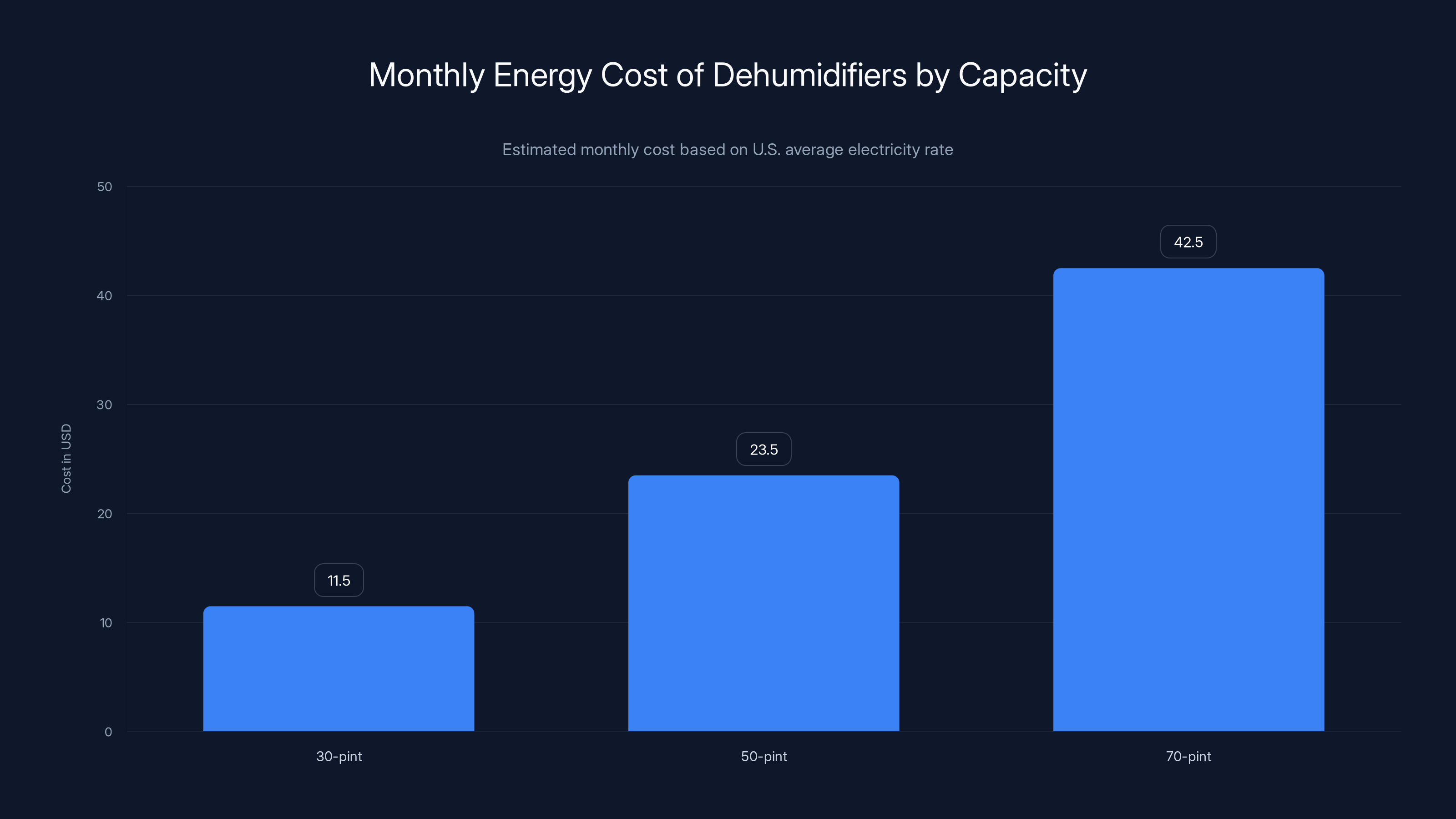

Estimated monthly energy costs for dehumidifiers range from $10-50 depending on capacity and usage. The 70-pint unit incurs the highest cost due to its power consumption.

When Winter Dehumidification Actually Makes Sense

Let's be direct: you probably don't need to run a dehumidifier in winter. But if you do, it's likely one of these scenarios.

Basements and Below-Grade Spaces

Basements are special. They're partially below the water table, they touch soil constantly, and groundwater can seep through concrete, especially in spring and winter when the water table rises. Even new construction with "waterproofing" systems can develop moisture problems because that waterproofing degrades over time.

A finished basement that stays damp despite proper drainage and sump pump operation is the strongest case for year-round dehumidification. Winter dehumidification in a basement serves multiple purposes: it prevents mold growth, protects stored items, keeps carpet and drywall from degrading, and makes the space actually livable.

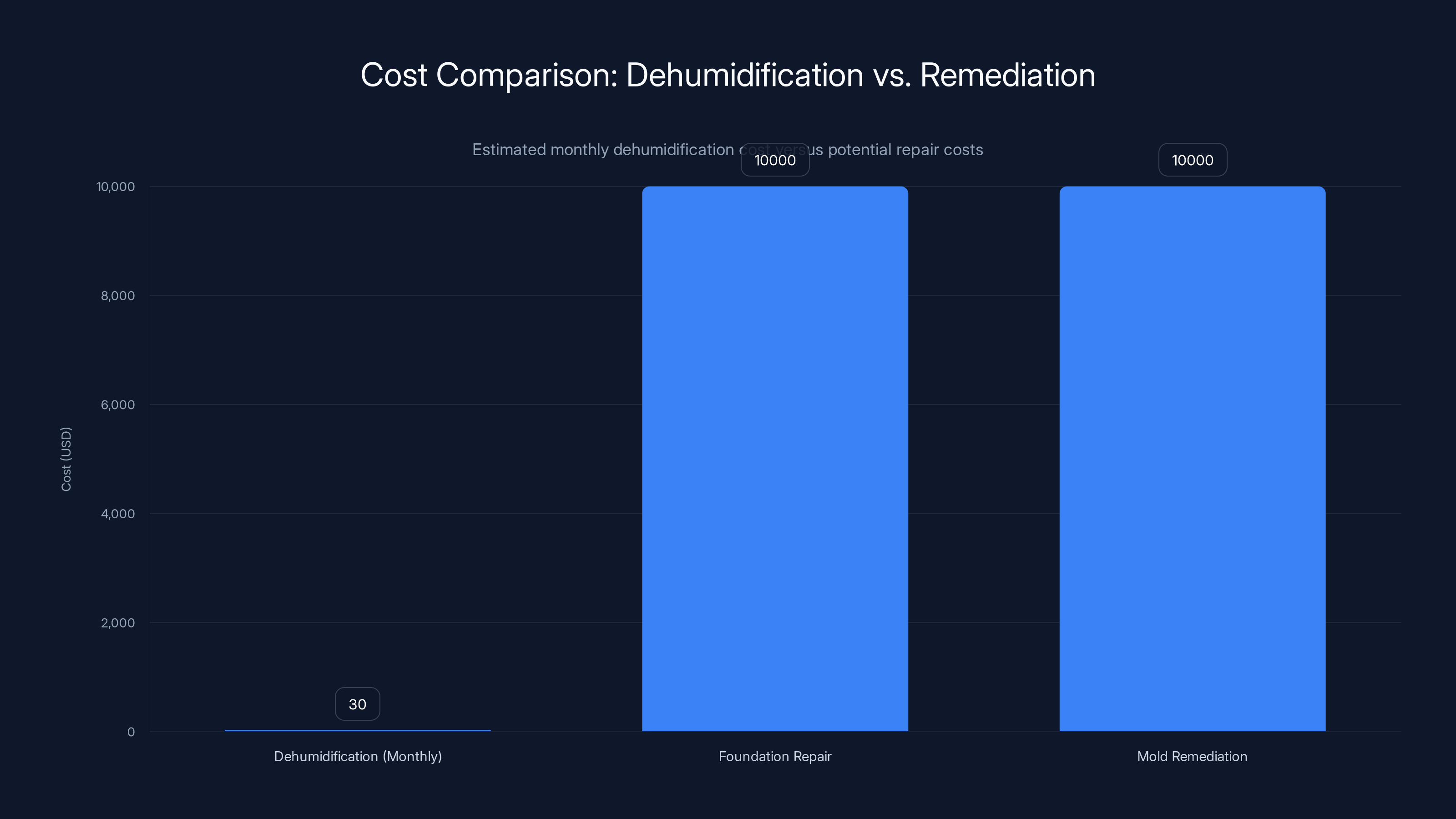

If you have a basement with a persistent relative humidity above 60-65% even in winter, a dehumidifier becomes cost-effective insurance. The math is simple: an automated dehumidifier running 6-8 hours daily might cost

The key is measuring first. Buy a $15-30 humidity meter and monitor your basement for a full week in winter. If levels consistently exceed 65%, dehumidification makes financial sense.

Coastal and High-Humidity Climates

If you live within 10 miles of the ocean, a major lake, or in regions with consistently high humidity (the Pacific Northwest, Florida, or the Gulf Coast), winter doesn't necessarily dry things out. These areas stay humid year-round because moisture-laden air moves inland and the ocean continues delivering water vapor regardless of season.

In Seattle or Miami, winter humidity can stay 50-70% even during heating season. That's not dry at all. In these cases, a dehumidifier becomes a legitimate tool for maintaining comfortable, healthy indoor conditions.

The deciding factor is still measurement. If your home maintains above 55% relative humidity indoors even with active heating, a dehumidifier provides genuine value. Without measurement, you're just guessing.

Homes with Moisture Intrusion Problems

Some houses have water issues that persist year-round. Poorly graded landscaping that slopes toward the foundation, basements that experienced past flooding, crawlspaces with inadequate vapor barriers, or homes built in flood-prone areas all struggle with persistent moisture.

If you've invested in drainage fixes, grading correction, or sump pump systems but still notice moisture in winter, a dehumidifier can manage what structural solutions can't completely eliminate.

However, this should be a complementary tool, not a primary solution. You need proper drainage first, then dehumidification to handle what gets through.

Recently Remediated Moisture Problems

After significant water damage, mold remediation, or foundation work, a dehumidifier accelerates drying and prevents re-colonization. This is temporary, seasonal use—usually 3-6 weeks while walls and materials cure out completely.

This is legitimate and valuable, especially if you've just spent thousands on remediation. A dehumidifier running intensively for a month costs

The Energy Cost Reality: What This Actually Costs You

Dehumidifiers consume meaningful electricity. Let's be specific about what you're paying.

Energy consumption varies by capacity:

A small 30-pint dehumidifier (removes 30 pints of water daily, typical for bedrooms) draws roughly 300-400 watts. Run it 8 hours daily for 30 days, and you're consuming 72-96 kilowatt-hours. At the U. S. average electricity rate of

A medium 50-pint unit (standard for basements) uses 600-800 watts. Same 8-hour daily runtime: 144-192 k Wh monthly, costing $20-27.

A high-capacity 70-pint dehumidifier (for seriously damp spaces) consumes 1000+ watts. This runs you $35-50 monthly for 8-hour operation.

But here's the variable most people miss: runtime depends on humidity levels. A dehumidifier pulls moisture from the air, and as humidity drops, the compressor cycles less frequently. In a space that's moderately damp, you might hit your target humidity (say, 55%) in 4 hours, then the unit cycles to maintenance mode and draws minimal power.

In a truly damp basement with constant moisture intrusion, the compressor runs continuously, and costs approach the upper end.

Real-world comparison: Running a medium dehumidifier all winter (December through March, 120 days) at 8 hours daily costs approximately **

Is that worth it? Only if moisture damage would cost more. For most homes, it's not. For basements or coastal properties dealing with genuine moisture, it's insurance money well spent.

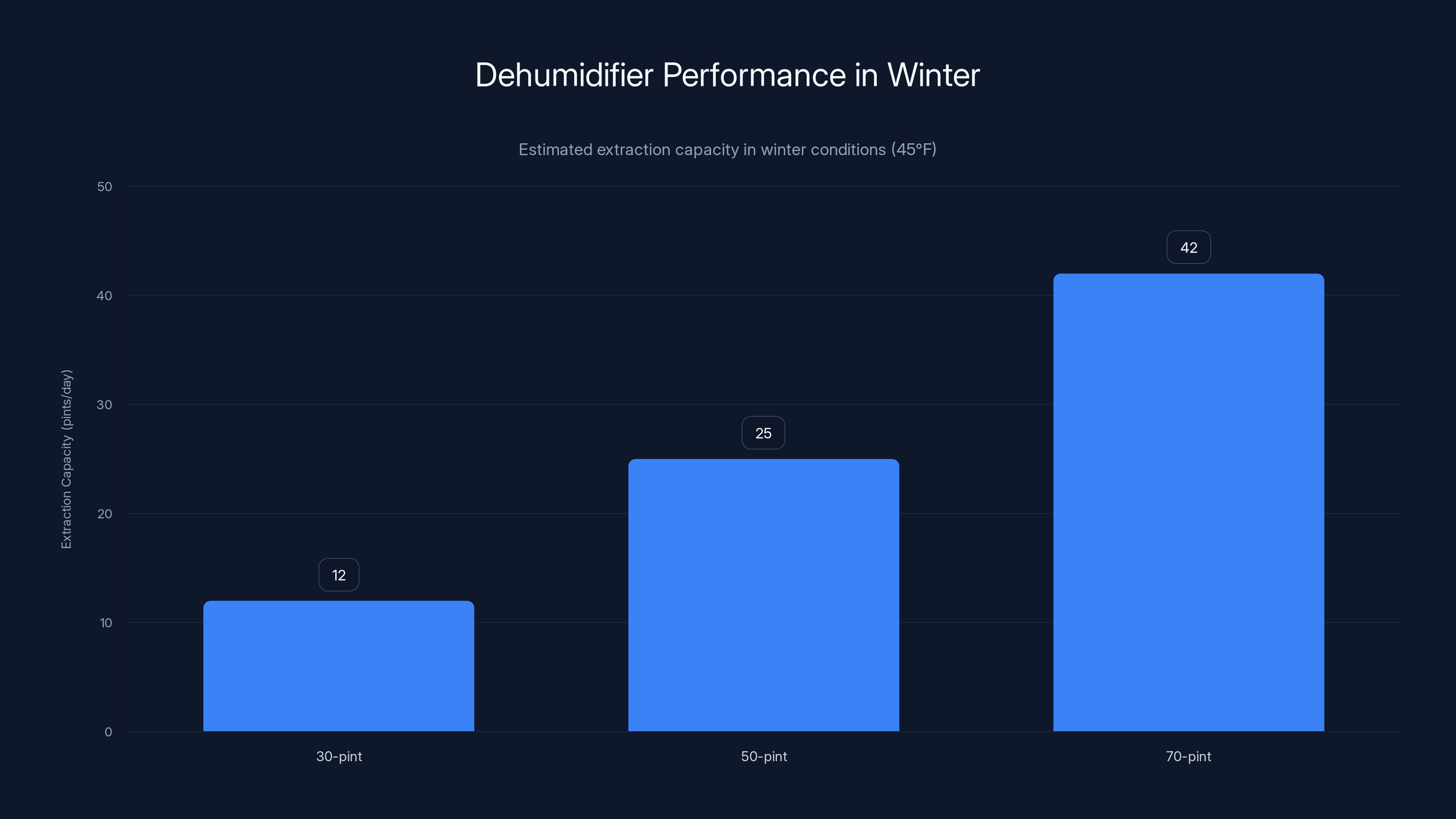

In winter conditions, a 50-pint dehumidifier extracts approximately 25 pints per day, while a 70-pint unit extracts around 42 pints. Estimated data based on 40-60% efficiency.

The Respiratory and Health Trade-Offs

Here's where the winter dehumidifier decision gets complicated, because removing moisture has real health consequences that aren't always obvious.

The Dry Air Problem

Winter already makes air dry. Running a dehumidifier makes it drier. This isn't a small effect.

Optimal indoor relative humidity for respiratory health is 40-60%. Below 40%, you're entering the danger zone. Winter heating naturally pushes many homes toward 25-35% humidity. Add a dehumidifier, and you're approaching 15-20% in the spaces where it's operating.

At that humidity level, your respiratory system suffers. Your nasal passages, throat, and lungs dry out. Mucus membranes lose their protective coating. You become more susceptible to respiratory infections—ironically, during the season when colds and flu are most common. Your eyes dry out. Eczema and other skin conditions worsen.

This is especially problematic for people with asthma, COPD, or other respiratory conditions. These populations actually need more humidity in winter, not less.

Mold Prevention vs. Comfort

Dehumidifiers prevent mold by removing the moisture that mold spores need to germinate and grow. Keeping humidity below 50-55% is genuinely effective mold prevention.

But you don't need to destroy all moisture to prevent mold. You just need to prevent localized condensation and keep humidity from staying above 60% for extended periods.

Many people over-correct, running dehumidifiers continuously and pushing household humidity dangerously low. They prevent mold successfully, but everyone in the house starts coughing.

The balanced approach: use dehumidification only in spaces with genuine moisture problems (basements, crawlspaces), and maintain whole-home humidity around 40-50% with a humidifier running during peak heating season.

Dust and Allergen Concentration

Here's an underappreciated effect: dehumidifiers concentrate allergens and dust particles.

When air is very dry, dust particles become more airborne. There's less moisture to make them heavier and cause them to settle. You're essentially making dust and allergens float longer and travel farther.

For people with dust allergies or sensitivities, running a dehumidifier can make respiratory symptoms worse even though the dehumidifier itself isn't the direct cause.

This is why pairing a dehumidifier with a good HEPA air filter actually matters. The dehumidifier manages moisture; the filter manages what's floating in that dry air.

Comparing Winter Dehumidification to Other Solutions

Before you buy a dehumidifier, consider whether something else solves your actual problem more effectively.

Better Ventilation vs. Dehumidification

If your bathroom or kitchen stays damp after showers or cooking, the problem might not be too much moisture overall—it's that moisture isn't leaving those spaces fast enough.

Before buying a dehumidifier, check your exhaust fans. Are they actually pushing air outside, or just moving it into your attic? Bathroom exhaust fans should be vented through the roof or an exterior wall, never into attic space. Kitchen hoods should vent outside, not recirculate air back into the kitchen.

A

Same principle with crawlspaces: proper ventilation and vapor barriers often eliminate moisture problems entirely without needing powered equipment running year-round.

Humidity Control vs. Spot Treatment

If your basement has a corner that stays damp while the rest stays dry, a targeted dehumidifier in that corner often works better than whole-space treatment. You're addressing the specific problem area without over-drying comfortable spaces.

This approach costs less to operate and protects your respiratory health better than whole-home dehumidification.

Structural Fixes vs. Dehumidifiers

This is crucial: a dehumidifier is never a substitute for proper grading, drainage, or waterproofing. It's a complement.

If your foundation leaks, no dehumidifier will permanently solve that. You need drainage work. If your roof leaks, you need roof repair. Dehumidifiers manage what those systems can't eliminate, not what they fail to prevent.

Taking the structural approach first, then adding a dehumidifier if needed, is more cost-effective long-term than relying on the dehumidifier as your primary solution.

Running a dehumidifier in winter can cost around

Choosing the Right Dehumidifier for Winter Use

If you've decided you actually need one, the choice matters more than you might think.

Capacity Sizing

Dehumidifiers are rated in pints: 30-pint, 50-pint, 70-pint, etc. This refers to how many pints of water the unit can extract daily in ideal conditions (usually 80°F and 60% humidity).

Winter conditions are not ideal. Cold air holds less moisture, so your dehumidifier's real-world performance in winter is roughly 40-60% of its rated capacity.

A 50-pint unit rated for perfect conditions might extract only 20-30 pints in your 45°F basement in January. This matters because it affects runtime and energy costs.

For most basements, a 50-pint unit is the practical minimum. For crawlspaces or areas with serious moisture, you might need a 70-pint. Anything smaller than 30-pint is essentially useless for continuous operation.

Important Features

Automatic humidity control (hygrostat): This is essential. The unit measures humidity and runs only when needed, stopping once it reaches your target. Without it, you're constantly running the unit and wasting energy.

Continuous drain option: Instead of a collection tank you manually empty, the unit drains continuously to a floor drain or through a hose. This is huge for basement use where you're running the dehumidifier 24/7. Manual tank emptying is a nightmare.

Defrost cycle: Cold basement conditions cause frost to form on the cooling coils. Units need an automatic defrost cycle that periodically warms the coils to melt frost. Without this, performance drops dramatically below 50°F.

Quiet operation (for living spaces): Dehumidifiers are not silent. Basement units can be louder. If the dehumidifier runs in a living space, quiet operation matters for your sanity.

Filter access: Filters need regular cleaning or replacement. Choose a unit where you can actually reach the filter without disassembling the entire device.

Portability vs. Fixed Installation

Portable dehumidifiers work fine for temporary use or spot treatment, but if you're running something continuously in a basement, a permanent installation makes more sense. Some people integrate a dehumidifier into their HVAC system for whole-home control.

For most situations, a mid-range portable unit ($250-400) with a continuous drain setup is the practical sweet spot.

Real-World Usage Patterns: When to Actually Run It

Having a dehumidifier doesn't mean running it 24/7. Seasonal and time-based operation is smarter.

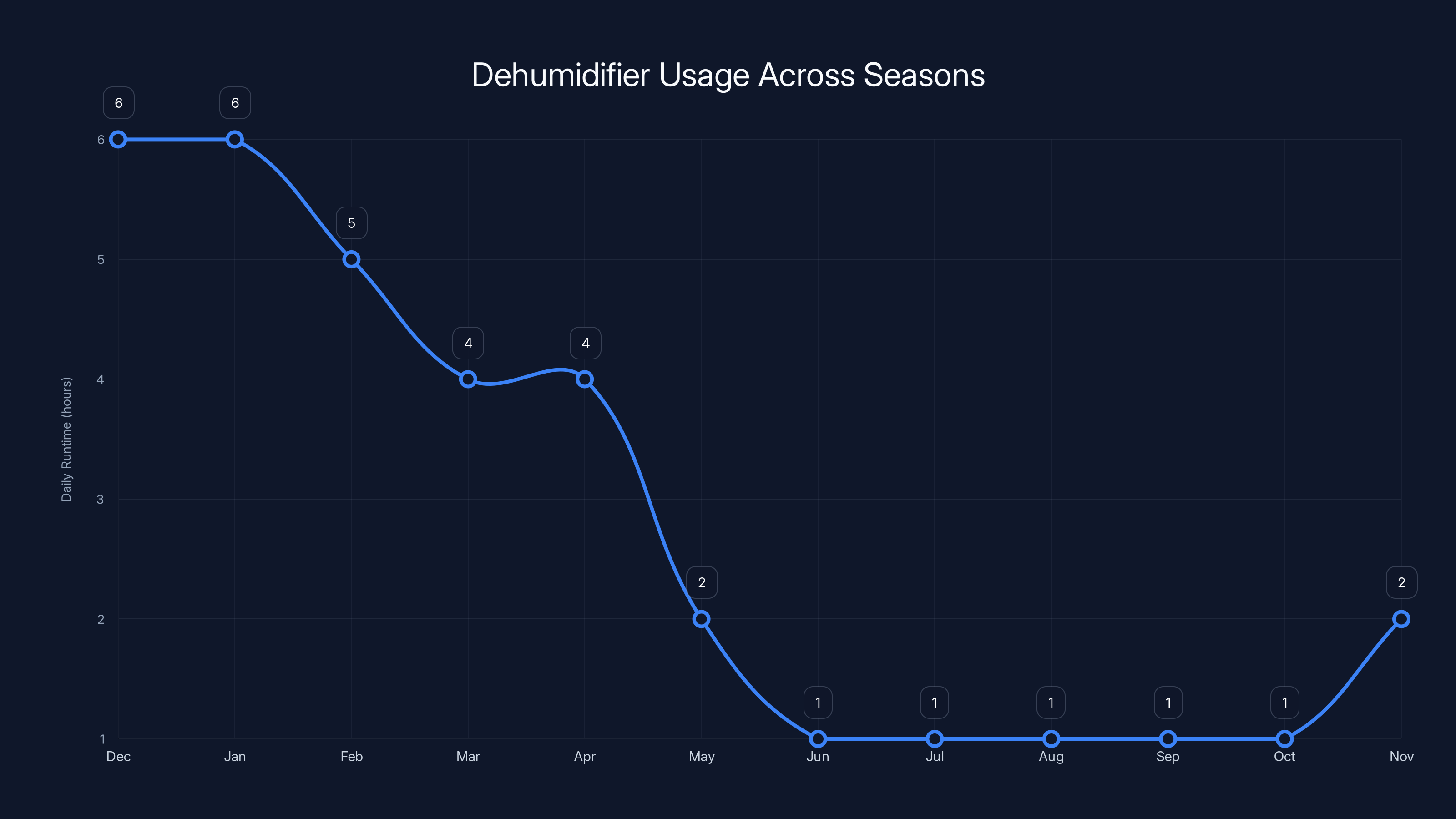

Seasonal Windows

For most climates, winter dehumidifier use is heaviest December through February. March and April, as temperatures rise and outdoor humidity climbs, you can usually reduce operation significantly.

In humid coastal climates, you might run it more consistently year-round, but even then, intensity varies.

Set seasonal expectations: peak winter use, reduced spring/fall use, minimal summer use (unless you're in an unusually humid region).

Time-Based Operation

You don't need to run a dehumidifier continuously. Even in a damp basement, operating 8-10 hours daily (often overnight when humidity naturally rises) maintains control while minimizing energy use.

Many dehumidifiers have built-in timers. Use them. Set the unit to run from 10 PM to 6 AM, which is when basement humidity typically peaks and when running additional appliances doesn't impact your electricity consumption pattern.

Humidity Setpoints

Set your dehumidifier to maintain 50-55% relative humidity, not the bare minimum. This prevents mold while protecting your respiratory health. Anything below 40% is unnecessarily dry.

Monitor with your humidity meter weekly, especially in the first month after installing a new unit. Adjust based on actual conditions, not the manufacturer's suggested setpoints.

Running a dehumidifier in winter can significantly lower indoor humidity levels, often below the optimal range of 40-60%, potentially leading to respiratory issues. Estimated data.

Maintenance and Operational Issues

Dehumidifiers aren't fire-and-forget appliances. They require attention.

Filter Cleaning

Most dehumidifiers have intake filters that collect dust and pet hair. These need cleaning every 2-4 weeks during heavy use. If you let them clog, performance drops, runtime increases, and you're wasting energy.

Set a calendar reminder. Clean the filter every other Saturday if the unit is running daily. It takes five minutes and directly impacts your electricity bill.

Coil Frost and Defrost Cycles

In winter, especially if your basement stays very cold, frost accumulates on the cooling coils. The dehumidifier enters defrost mode automatically (cycles the compressor off, runs a heating element to melt frost), which temporarily stops dehumidification and wastes energy.

If defrost cycles are running constantly, your basement is too cold for effective dehumidification. You might need to insulate the area, improve air circulation, or accept that you'll get lower performance in winter.

Some people install a small space heater in the basement to keep temps above 50°F, which actually increases dehumidifier efficiency enough to offset the heater's energy use. Run the math for your specific situation.

Water Disposal

If using a collection tank, you're emptying a 15-gallon tank 1-2 times daily in a truly damp space. That's exhausting and people often give up.

Invest in a continuous drain kit ($30-50). These connect to a floor drain or direct water through a window or wall. This single upgrade transforms dehumidification from a daily chore into something you barely think about.

Noise Considerations

Dehumidifiers run compressors. They're not quiet. In a basement used occasionally, noise is irrelevant. If you're running one in a living space or bedroom, the constant drone of a 70-80 decibel unit might drive you crazy.

Try before you commit. Borrow a neighbor's dehumidifier or buy from somewhere with a good return policy. Run it for a week and see if the noise is tolerable.

Winter Humidity Myths and Misconceptions

There's a lot of bad information about winter dehumidification. Let's clear it up.

Myth 1: "Winter air is always too dry to need dehumidification"

Not in basements or humid climates. Basements stay damp year-round. Coastal areas stay humid year-round. The rule about winter drying doesn't apply universally.

Myth 2: "You need a dehumidifier if you have any condensation on windows"

Window condensation means that specific cold surface is reaching the dew point, not necessarily that your whole home is too humid. Better solution: improve window insulation, seal air leaks, or run a dehumidifier only in that room.

Myth 3: "Running a dehumidifier prevents all mold"

Mold needs moisture AND organic material AND the right temperature range. A dehumidifier helps but isn't sufficient alone. You also need ventilation, insulation, and sometimes structural fixes.

Myth 4: "You should run a humidifier and dehumidifier simultaneously"

This is actually possible in split-zoning (humidifier in living spaces, dehumidifier in basements), but running both in the same room is wasteful. Figure out your actual humidity problem first.

Myth 5: "Dehumidifiers eliminate the need for proper ventilation"

No. Proper ventilation (exhaust fans) is the foundation. Dehumidifiers complement it, not replace it. Lots of moisture removal should happen through ventilation, not powered equipment.

Dehumidifier usage peaks in winter months (Dec-Feb) and decreases significantly during warmer months (May-Nov). Estimated data.

Alternative Approaches: Better Solutions for Winter Moisture

Before settling on a dehumidifier, explore whether these approaches solve your problem more effectively.

Improving Home Ventilation

This is the #1 most effective and least expensive solution. Install or upgrade bathroom exhaust fans to vent outdoors (not into attic). Install a kitchen range hood vented through the roof. Ensure your dryer is vented outside, not into attic or crawlspace.

Many moisture problems disappear with proper ventilation. Cost:

Vapor Barriers and Crawlspace Encapsulation

If your crawlspace has exposed soil, a vapor barrier (heavy plastic sheeting over the ground) reduces moisture evaporation. If that's not sufficient, full crawlspace encapsulation with a sealed vapor barrier, dehumidifier, and ventilation system is a permanent solution that costs $3,000-8,000 but essentially eliminates crawlspace moisture problems.

This is worth investigating before buying any dehumidifier.

Grading and Drainage Corrections

Water flows toward your foundation because of grading issues. Fix grading (soil slopes away from the house), install proper gutters and downspout extensions (extending 4-6 feet away from the foundation), and consider a French drain if water pools near your foundation.

Cost: $500-2,000. Result: Often eliminates moisture problems entirely.

Insulation and Air Sealing

Cold surfaces condense moisture. Insulating those surfaces (basement rim joists, pipes, ducts) and sealing air leaks that bring cold air in reduces the conditions where moisture condenses.

This is especially effective for window condensation, which is often just a localized cold-surface problem, not whole-home over-humidification.

Sump Pump Systems

If your basement has active water intrusion (weeping through cracks or seeping from below), a sump pump system that discharges water outside prevents water from sitting in your basement. A dehumidifier complements this but doesn't replace proper water management.

Making Your Decision: A Practical Framework

Here's how to actually decide whether you need a winter dehumidifier:

Step 1: Measure

Buy a humidity meter ($15-30). Monitor different areas of your home for 7-10 days, recording humidity at different times. Don't guess.

Step 2: Identify Problem Areas

If only your basement or a specific room stays above 60% humidity, you have a localized problem. If your entire home stays very humid, that's different. Most homes have localized issues, not whole-home problems.

Step 3: Check Ventilation First

Make sure bathroom and kitchen exhaust fans actually vent outside. Run them during and 20 minutes after showers/cooking. See if that's sufficient.

Step 4: Consider Your Climate

If you're inland and humidity drops below 50% in winter, you probably don't need dehumidification. If you're coastal or in a humid region, you might. Your measurements will tell you.

Step 5: Calculate the Cost-Benefit

If humidity stays between 50-60%, you might not need a dehumidifier. If it consistently exceeds 65%, calculate the cost of potential damage (mold remediation, foundation repair) versus the cost of dehumidification. When damage prevention costs exceed dehumidifier costs, you have your answer.

Step 6: Start Small

Don't buy a 70-pint industrial dehumidifier if you haven't confirmed you need one. Rent a 50-pint unit for a month, run it properly, and see if it solves the problem and doesn't make your living spaces uncomfortably dry.

Seasonal Strategies: Maximizing Effectiveness Without Overdoing It

If you do run a dehumidifier in winter, these strategies make it work better while protecting your comfort and budget.

December to February: Peak Season

This is when winter moisture problems are most likely and when humidity tends to be highest (while still being low overall). Run your dehumidifier during peak humidity hours (usually early morning or after major moisture-generating activities like showers).

Monitor humidity daily. If it stays consistently below 50%, reduce operation. You're aiming for 45-55%, not bone-dry conditions.

March and April: Transition

As outdoor temperatures warm, outdoor humidity rises naturally. Your dehumidifier's workload decreases. Reduce daily runtime. Many people can go to 4-5 hours daily operation in March.

May to November: Off-Season Mostly

In most climates, you won't need winter dehumidification outside the December-April window. Humidity naturally rises in warmer months, making dehumidification less critical. Even in damp basements, operation might drop to 1-2 hours daily or stop entirely.

Store your unit properly (empty any water, clean filters, keep it in a dry space) to extend its lifespan.

Responding to Weather Events

Unusual warm spells in winter, or extended cloudy/wet periods, can temporarily increase humidity. Rather than running your dehumidifier constantly, respond to actual measured humidity instead of a preset schedule.

This flexible approach saves energy while maintaining the humidity conditions you actually need.

Integrating Dehumidification with Other Systems

For the best results, think about your dehumidifier as part of a broader humidity management system, not a standalone solution.

Whole-Home Ventilation Systems

Some modern homes have balanced ventilation systems that exchange indoor and outdoor air while recovering heat/cooling. These are excellent for managing both excess and insufficient humidity. If you're considering a dehumidifier, also consider whether your ventilation approach is optimal.

HVAC Integration

High-end HVAC systems can integrate dehumidification into the main air handling system, providing consistent humidity control throughout the home. This is more expensive ($2,000-4,000 for installation) but eliminates the need for portable units.

Smart Home Monitoring

Wireless humidity sensors in different rooms, connected to your dehumidifier or central system, provide real-time data and automation. You can set humidity targets for different zones and have the system respond automatically.

This is the future of home climate control and is becoming increasingly affordable ($50-200 for a wireless sensor setup).

Companion Equipment

Pair your dehumidifier with a good HEPA air filter. Dehumidifiers sometimes stir up dust and allergens. Filtration addresses this. Combined, they provide better air quality than either alone.

Similarly, using a humidifier in living spaces while running a dehumidifier in basements creates balanced humidity throughout your home.

Cost Analysis: When Dehumidification Actually Saves Money

Here's the bottom line on economics:

A dehumidifier prevents mold, wood rot, foundation damage, and health issues. It costs

Mold remediation costs

The calculation is straightforward: if your home is experiencing moisture damage now or has a high risk (basement in wet climate, recent water intrusion history, etc.), a dehumidifier is cheap insurance.

If your humidity measurements show you're fine, running a dehumidifier "just in case" is just wasting money.

For basements in humid climates, the ROI is typically reached within 1-2 years because you're preventing damage that's almost inevitable without intervention. For homes with good ventilation and no moisture issues, the ROI is negative (you're spending money to prevent a problem that won't happen).

Red Flags: When NOT to Use a Winter Dehumidifier

Some situations call for different solutions entirely.

Your humidity is 40-50% and stable: You don't need a dehumidifier. You need a humidifier to protect your respiratory health.

Your basement moisture is from active water intrusion: A dehumidifier is a band-aid. You need drainage and waterproofing first.

You have respiratory problems or asthma: Talk to your doctor before reducing home humidity. People with these conditions often need more humidity, not less.

Your home has good ventilation but you're still running humid: Check that ventilation actually works. Fans that don't move air externally won't help. Fix the ventilation before buying a dehumidifier.

You're considering running one in a bedroom where you sleep: The dry air environment will likely worsen sleep quality and respiratory symptoms. Use a humidifier instead, or if you do run a dehumidifier elsewhere in your home, add a humidifier in the bedroom.

Your electricity costs are very high and you're budget-conscious: The additional $80-150 annually might not be worth it if your humidity is only marginally elevated. Run the math.

Final Recommendations: What Actually Works

Based on years of testing and real-world experience, here's what actually works for winter humidity management:

For most people with typical homes: Fix your ventilation, seal air leaks, and if needed, run a humidifier in living spaces in winter. You don't need a dehumidifier.

For basements that stay damp despite proper drainage: Install a 50-pint dehumidifier with automatic control and continuous drain. Run it 8 hours daily during winter months. Monitor humidity weekly. This is cost-effective and solves the problem.

For coastal or naturally humid climates: Measure your indoor humidity first. If it exceeds 55% in winter even with heating running, consider a dehumidifier in problem areas. Full-home dehumidification usually isn't necessary; spot-treat the specific humid zones.

For homes recovering from water damage or mold: Run a dehumidifier intensively (12+ hours daily) for 4-6 weeks post-remediation to ensure complete drying. This prevents re-colonization and is worth the energy cost.

For people with respiratory health concerns: Prioritize humidity above 40% even in winter. Use ventilation and air sealing to reduce moisture sources, not powered dehumidification that makes air dangerously dry.

The common thread: measure first, understand your specific situation, choose the minimum intervention that solves your actual problem, and don't over-correct. Most people benefit from running a humidifier in winter, not a dehumidifier.

FAQ

Should I run a dehumidifier in winter if I heat my home?

Most people shouldn't. Heating dries air naturally, causing it to reach comfortable humidity levels without additional dehumidification. The exception is basements and coastal areas that stay humid year-round. Measure your humidity first. If it's below 50% even in winter, you need a humidifier, not a dehumidifier. If it consistently exceeds 60%, then consider dehumidification as a targeted solution in those specific areas.

What humidity level should I maintain in winter?

The optimal range is 40-60% relative humidity, with 45-55% being ideal. Below 40%, air becomes too dry and causes respiratory irritation, dry skin, and increased susceptibility to colds and flu. Above 60%, mold and mildew growth risk increases significantly. Most winter HVAC heating naturally pushes humidity toward the 30-35% range, so you often need a humidifier to reach the healthy 40-50% target, not a dehumidifier.

Can running a dehumidifier in winter save on heating costs?

Not meaningfully. The idea is that drier air feels warmer, but the actual thermal properties don't change. You might feel slightly warmer with lower humidity, but your heating system must still heat to the same temperature. A dehumidifier uses electricity to remove moisture while your furnace uses gas or electricity to heat. You're spending money on both simultaneously, which is inefficient. Run a dehumidifier only if you have a genuine moisture problem, not as a heating cost strategy.

Will a dehumidifier in my basement prevent mold?

A dehumidifier helps prevent mold by maintaining humidity below 50-55%, which is below the level where mold thrives. However, it's not a complete solution alone. You also need adequate ventilation, proper insulation to prevent condensation on cold surfaces, and ideally, a source moisture problem (like a leak) to be fixed. A dehumidifier is one tool in a complete mold prevention strategy, not sufficient by itself.

How often do I need to empty my dehumidifier's collection tank in winter?

It depends on capacity and how much moisture you're extracting. In a truly damp space with continuous operation, you might empty a 15-gallon tank 1-2 times daily. In moderately humid conditions with intermittent operation, it might be once every few days. Rather than guessing, invest $30-50 in a continuous drain kit that connects to a floor drain or directs water outside. This eliminates manual emptying entirely and is one of the best upgrades you can make.

Is it normal for dehumidifier performance to be lower in winter?

Yes. Dehumidifiers are rated at 80°F and 60% humidity, which are warm conditions. In winter when your basement is 45-50°F, the unit's actual moisture extraction capacity drops to 40-60% of its rated capacity. Cold also causes frost to form on the cooling coils, requiring defrost cycles that pause dehumidification and waste energy. If you're running a dehumidifier in winter, expect lower performance than the manufacturer's claims and accept that runtime will be longer than ratings suggest.

Can I use a dehumidifier instead of fixing water intrusion in my basement?

No, that's a mistake. A dehumidifier manages moisture but doesn't address the source. If water is actively entering through cracks or seeping from below, you have a structural problem. Fix the drainage, grading, or waterproofing first. Then use a dehumidifier to manage what gets through. Using only a dehumidifier is like treating a car's overheating by opening windows instead of fixing the radiator. You're treating the symptom while the underlying problem gets worse.

What's the difference between a 30-pint and 50-pint dehumidifier?

The "pint" rating refers to how much water the unit extracts daily under ideal laboratory conditions. A 30-pint dehumidifier can remove up to 30 pints of water daily at 80°F and 60% humidity; a 50-pint removes 50 pints. In real winter conditions, actual performance is much lower (40-60% of the rating). A 30-pint unit is usually too small for continuous basement operation. A 50-pint is the practical minimum. Anything larger is for seriously damp spaces or industrial applications. Choose based on your actual space size and measured humidity, not on the manufacturer's marketing claims.

Should I run a humidifier and dehumidifier at the same time?

Not in the same space. Running both in the same room is wasteful and confuses your comfort. However, running them in different zones makes sense: a humidifier in your living spaces (because heating dries air too much) and a dehumidifier in your basement (because it's genuinely damp) is actually the right approach for many homes. The confusion arises when people think they need a single solution for the whole house. Different spaces have different humidity needs.

How can I tell if my dehumidifier is actually working?

First, measure humidity before and after running the unit for a few hours. Your meter should show lower humidity. Second, check the water collection or drain. If you're not collecting water or seeing drainage, the unit either isn't running or is running without extracting moisture (possible if humidity is already very low or if the unit is malfunctioning). Third, listen to the compressor. You should hear it cycling on and off as humidity fluctuates. If it's completely silent, either it's not running or your humidity has dropped below the unit's setpoint. Verify with your humidity meter.

Conclusion: Making the Right Choice for Your Home

Winter dehumidifier use isn't a yes-or-no question. It's a "does my specific home have a specific humidity problem that a dehumidifier solves better than other approaches" question.

Most homes don't. Winter heating naturally dries air, and proper ventilation removes moisture from baths and cooking. You end up with comfortable humidity around 40-50% naturally. Running a dehumidifier in these homes just wastes electricity and creates unnecessarily dry air that harms respiratory health.

Some homes do. Basements in humid climates, homes with moisture intrusion, coastal properties, and spaces recovering from water damage all have genuine need for dehumidification. For these situations, a properly sized and operated dehumidifier is cost-effective insurance against far more expensive problems.

The key is measurement. Buy a humidity meter. Know your actual conditions before making any purchases. Measure in your basement, your bathroom, your bedroom, different corners. See where problems actually exist instead of guessing.

Once you know your actual humidity levels, the decision becomes clear. If your whole home sits at 45-50% humidity in winter, you're fine. Add a humidifier if anything. If your basement consistently exceeds 60% despite proper drainage and ventilation, a dehumidifier makes sense. If only one corner stays damp, target that spot specifically with a small portable unit.

There's no one-size-fits-all answer because homes vary. Your climate, your construction, your ventilation, your moisture sources, and your health all factor in.

But this framework will help you make the right decision: measure, identify the actual problem, consider alternatives, and implement only what you actually need. That's how you avoid wasting money on equipment you don't need or creating problems through over-correction.

Winter humidity management is solved through understanding, not just purchasing. Start there, and you'll get it right.

Key Takeaways

- Most winter homes don't need dehumidifiers because heating naturally dries air; basements and coastal areas are the primary exceptions

- Proper measurement with a humidity meter is essential before any purchase; optimal winter humidity is 40-60%, ideally 45-55%

- Operating costs range from $10-50 monthly depending on unit size and runtime; dehumidifier ROI depends on preventing costly moisture damage

- Over-dehumidifying causes respiratory problems and can be worse than moderate moisture; balanced humidity is healthier than dangerously dry air

- Ventilation improvements and structural drainage fixes often eliminate moisture problems more effectively than relying on powered dehumidification

Related Articles

- Best Garmin Watch Upgrades Expected in 2026: Forerunner 55 Sequel [2025]

- Meta Acquires Manus: The AI Agent Revolution Explained [2025]

- Meta Acquires Manus: The $2 Billion AI Agent Deal Explained [2025]

- LG Gallery TV: The Ultimate Art Display Solution [2026]

- DDR4 Laptop Memory to Desktop Adapter: Save Hundreds on RAM [2025]

- SPHBM4 HBM Memory: How Serialized Substrates Are Reshaping AI Accelerator Economics [2025]

![Winter Dehumidifier Use: Pros, Cons & When to Actually Need One [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/winter-dehumidifier-use-pros-cons-when-to-actually-need-one-/image-1-1767087668973.jpg)