X's Algorithm Transparency Problem: What Researchers Actually Think [2025]

When Elon Musk announced that X had published its recommendation algorithm code, it sounded like a watershed moment. "We know the algorithm is dumb and needs massive improvements, but at least you can see us struggle to make it better in real-time and with transparency," he wrote. The framing was simple: X was the only major social network being honest about how it worked.

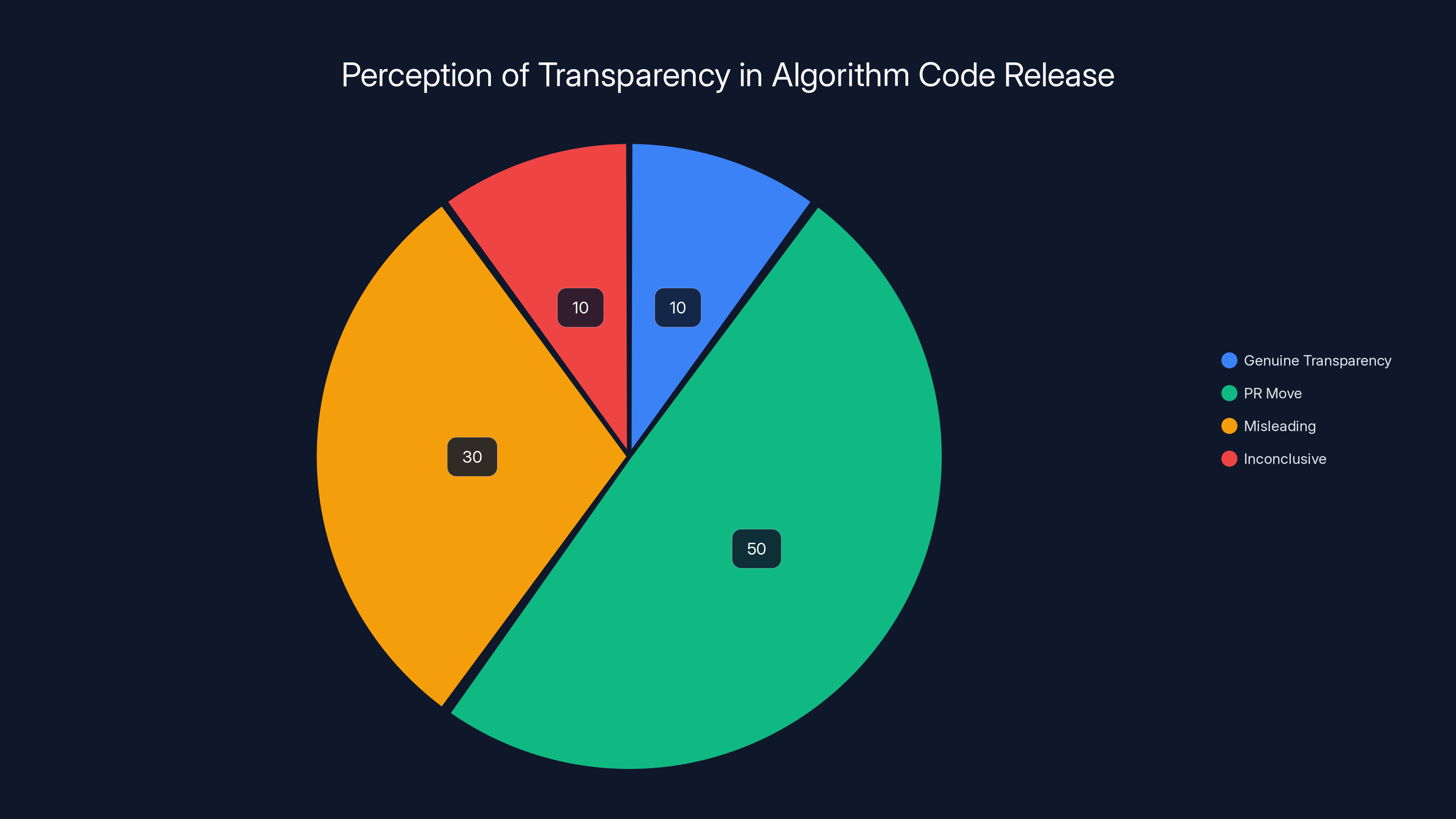

But researchers studying the actual code say something different. What X released isn't transparency. It's the appearance of transparency.

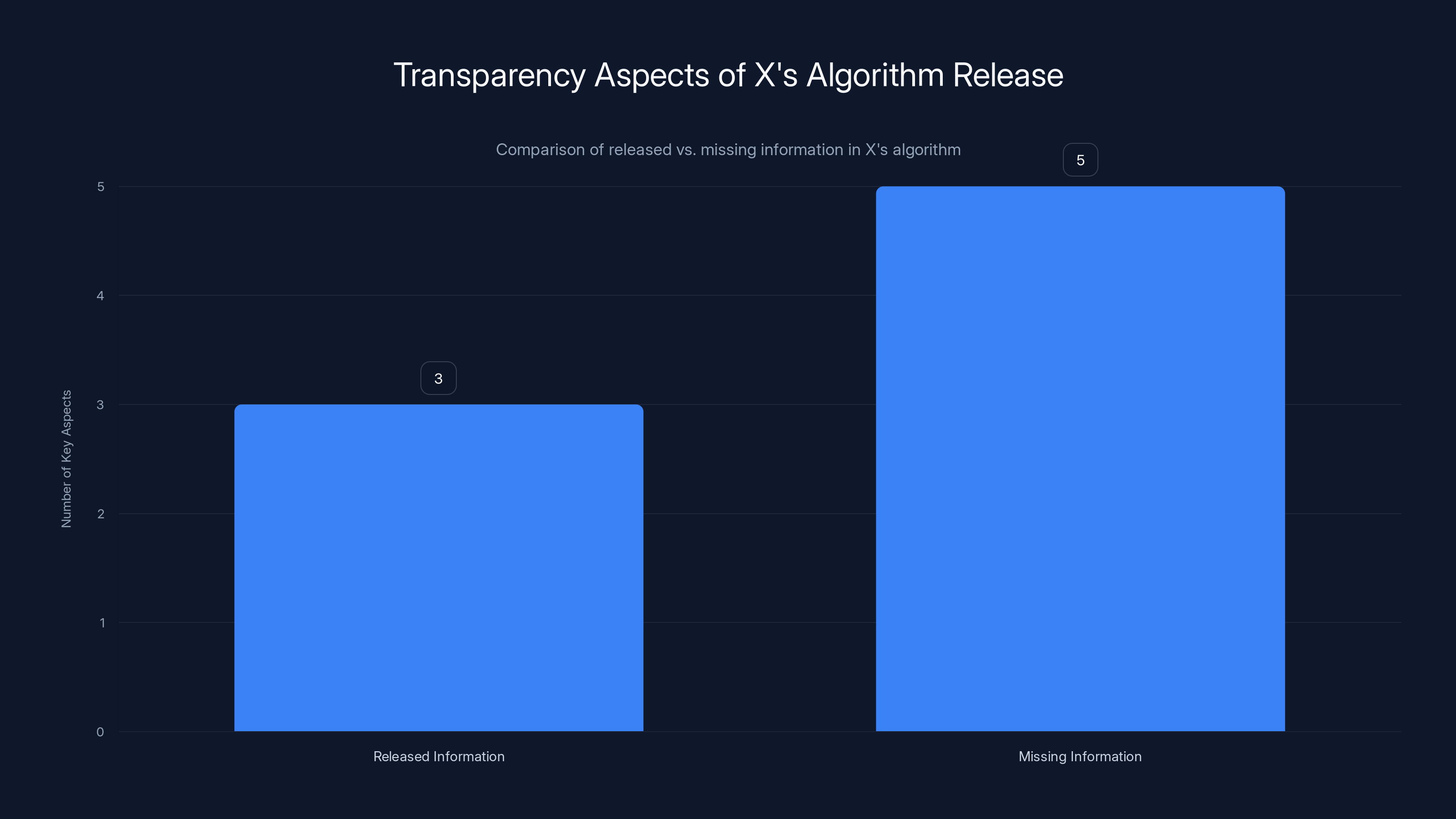

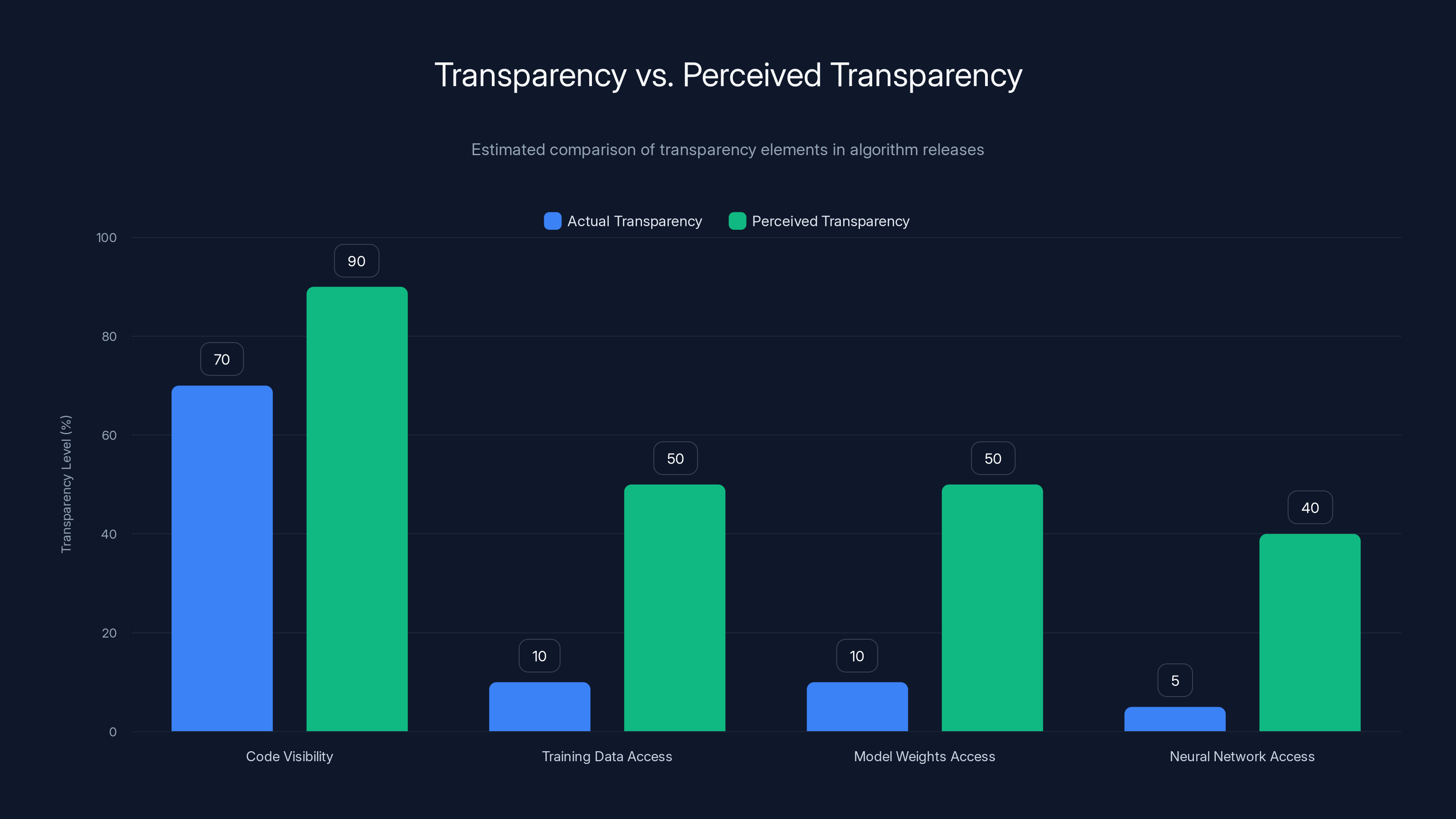

Here's the problem: the code X published is heavily redacted. It's missing the training data. It's missing critical information about how the algorithm weights different interactions. It's missing the actual machine learning models that do most of the real decision-making. What remains is like publishing a car manual that explains where the steering wheel is but leaves out the engine, the transmission, and the fuel system.

"What troubles me about these releases is that they give you a pretense that they're being transparent," says John Thickstun, an assistant professor of computer science at Cornell University. "The fact is that that's not really possible at all."

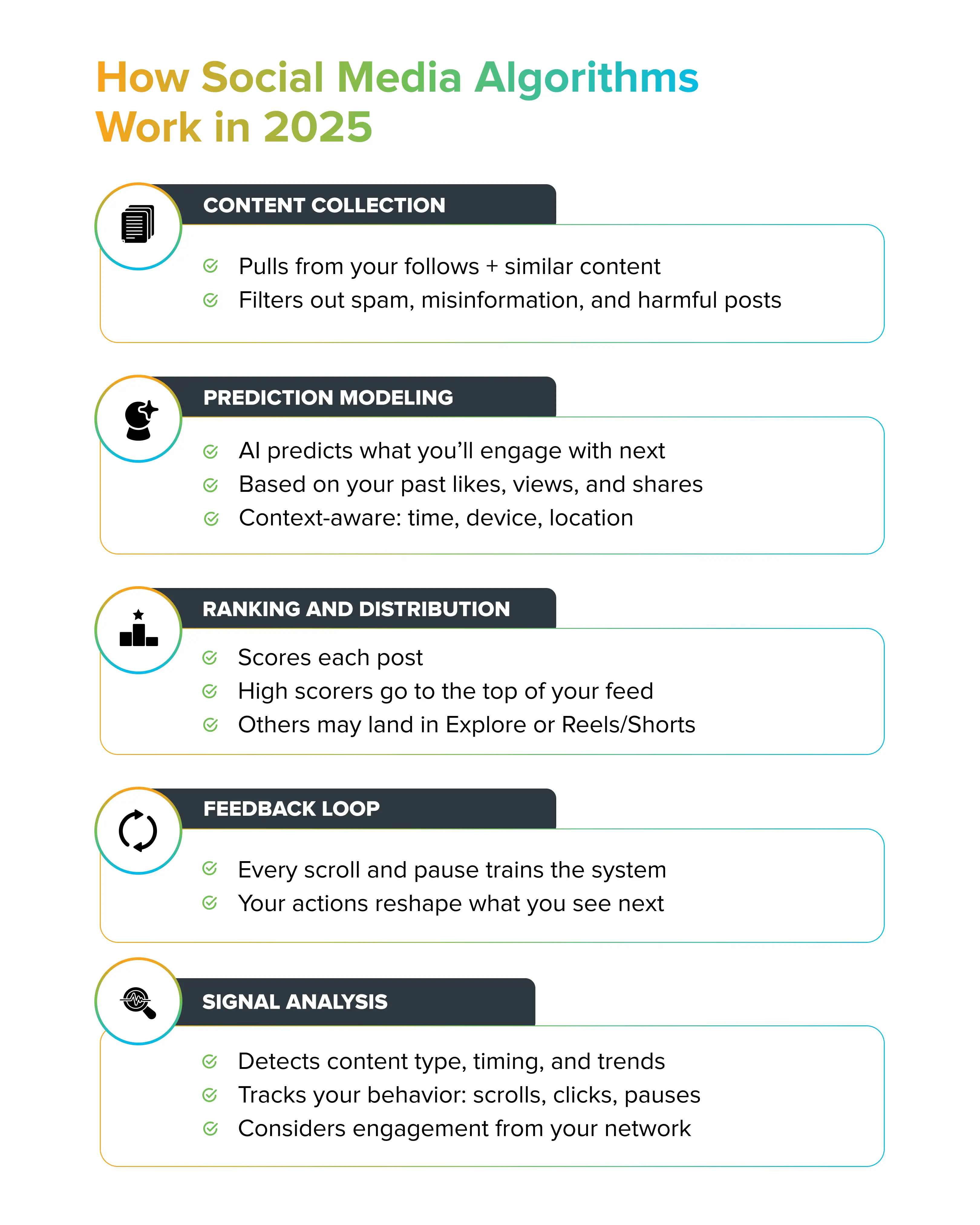

This matters more than it sounds. As AI systems become more powerful and more integrated into everyday life, understanding how these algorithms work—and what biases they might embed—becomes crucial. X's partial release creates an illusion of openness while actually preventing the kind of meaningful research that could improve the platform and inform how we regulate AI systems more broadly.

Let's dig into what X actually released, why it falls short, and what real algorithmic transparency would look like.

The Illusion of Openness: What X Actually Published

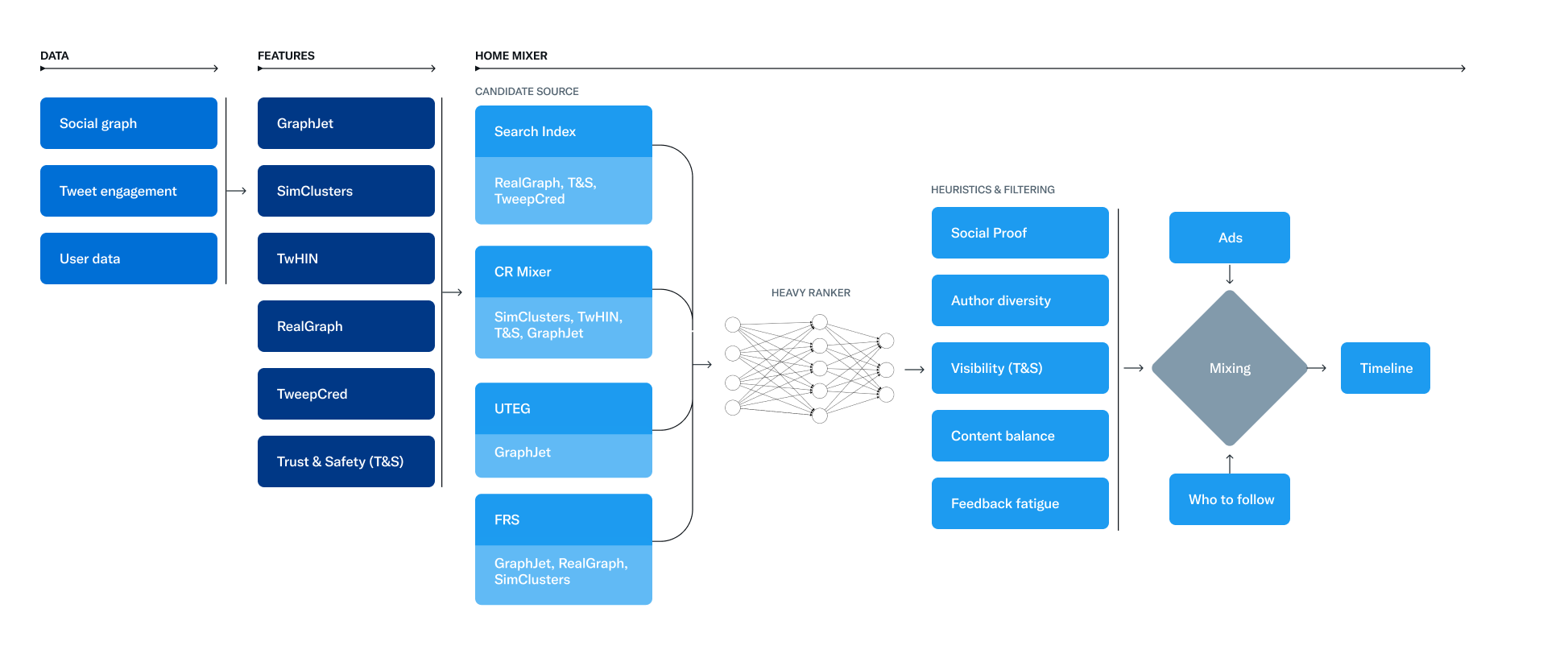

In early 2024, X made headlines by releasing the code for its recommendation algorithm. The move generated headlines and Musk got to claim the mantle of transparency while competitors like Meta and Google stayed silent. Content creators on X immediately started dissecting the code, posting threads about supposed strategies to boost engagement. One viral post claimed X "will reward people who conversate." Another insisted video posting was the key to virality. A third warned that "topic switching hurts your reach."

These posts had hundreds of thousands of views. People were treating the released code like a cheat sheet for the algorithm.

But here's what Thickstun and other researchers point out: you can't actually draw those conclusions from what was released. The code snippet doesn't contain enough information to understand how the algorithm actually makes decisions at scale.

Think about it this way. Imagine someone handed you the source code to Google Search and said, "Here's how search works." But they removed all the ranking signals, all the training data, all the machine learning models, and all the proprietary weighting mechanisms. What they handed you would look like code, would technically be "real," but wouldn't help you understand how Google actually ranks pages.

That's roughly what X did.

The code X published does include some useful information. It filters out posts more than a day old. It shows some of the structural decisions about how content flows through the system. But according to Ruggero Lazzaroni, a Ph.D. researcher at the University of Graz who studies recommendation algorithms, "much of it is not actionable for content creators, and none of it is sufficient for researchers to actually audit or understand the system."

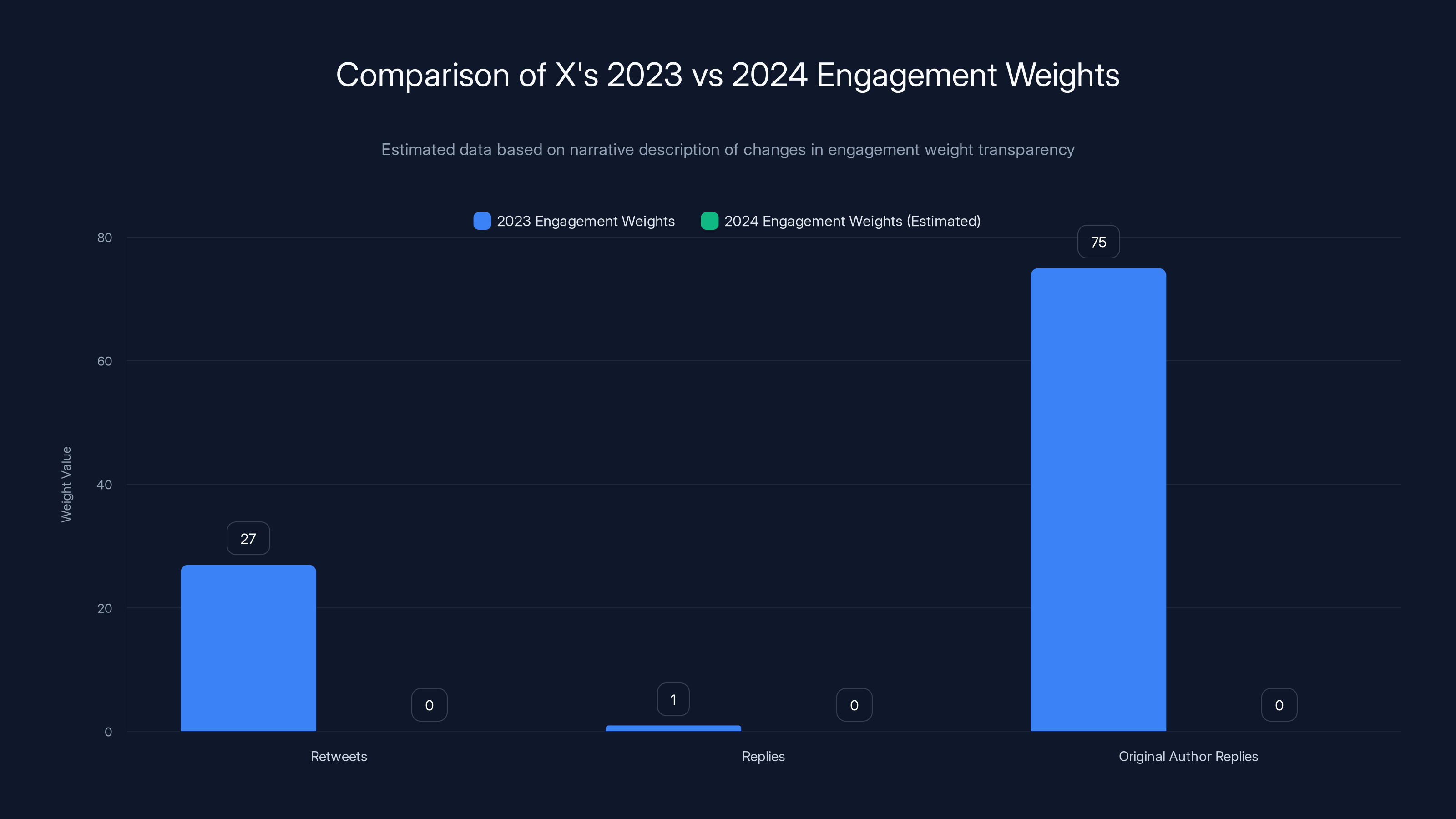

Moreover, X explicitly redacted information that was public in the previous 2023 version. Back then, X shared how it weighted different engagement metrics. A reply was worth 27 retweets. A reply from the original author was worth 75 retweets. Those numbers were gone in the 2024 release, claimed to be excluded "for security reasons."

Security is a valid concern. But it's also convenient. It means anyone trying to understand or audit the algorithm hits a wall pretty quickly.

X's algorithm release included some code but lacked critical components like training data and model details. Estimated data based on content.

The Shift to Grok: Algorithms Becoming Less Understandable

Here's where things get even more complicated. X's recommendation algorithm has changed significantly since 2023, and not in ways that make it more transparent.

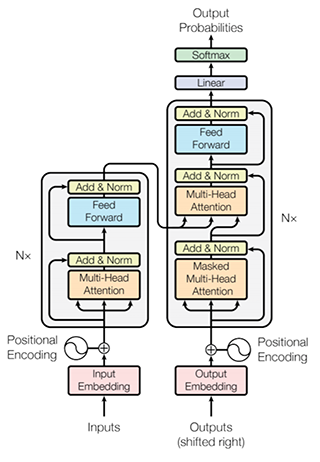

The old system was relatively straightforward. X counted likes, retweets, replies, and other interactions. It applied mathematical weights to those interactions. Then it ranked posts based on the combined score. It was deterministic. You could trace the logic. It wasn't always right, but you could understand why it made certain decisions.

The new system relies on something completely different: a large language model similar to Grok, X's own AI chatbot. Instead of calculating scores based on actual engagement, the model predicts how likely you are to engage with a post. The algorithm then ranks posts based on those predictions.

This is a fundamental shift. And it makes the algorithm vastly more opaque.

"So much more of the decision-making is happening within black box neural networks that they're training on their data," Thickstun explains. "More and more of the decision-making power of these algorithms is shifting not just out of public view, but actually really out of view or understanding of even the internal engineers that are working on these systems."

Let that sink in for a moment. The engineers building the system don't fully understand how the system makes decisions. That's not a flaw specific to X. It's a property of deep neural networks. They learn patterns from training data, but those patterns exist in a space humans can't directly inspect. We can test inputs and observe outputs. But we can't peer inside and see why the network made a specific choice.

When you combine that with the missing training data and the redacted weighting mechanisms, the algorithm becomes something that no external researcher could possibly replicate or meaningfully audit. You have the code that calls the model. You don't have the model itself. It's like having a movie script but no film.

In 2023, X provided specific engagement weights, which were removed in 2024 for security reasons. Estimated data highlights the lack of transparency in 2024.

What's Actually Missing: The Data Problem

Mohsen Foroughifar, an assistant professor of business technologies at Carnegie Mellon University, points to one critical gap: nobody knows what data trained the Grok-based recommendation model.

This matters enormously. If the training data is biased—if it overrepresents certain demographics, viewpoints, or content types—the model will learn those biases. No amount of careful coding or ethical intentions can fix a fundamentally biased dataset.

"If the data that is used for training this model is inherently biased, then the model might actually end up still being biased, regardless of what kind of things that you consider within the model," Foroughifar says.

We've seen this play out repeatedly in AI systems. Facial recognition trained primarily on light-skinned faces performs worse on darker-skinned faces. Language models trained on internet text absorb gender stereotypes. Recommendation algorithms trained on user behavior learn to amplify sensationalism and divisiveness because that's what engages users.

Understanding the training data is often the first step to understanding these failures. But X hasn't published it. Content creators don't know. Researchers can't study it. Even internal teams probably don't have complete transparency into what made their way into training datasets.

Without that information, Lazzaroni says, "we have the code to run the algorithm, but we don't have the model that you need to run the algorithm. You can't reproduce it. You can't test it. You can't audit it."

This creates a practical research problem. Lazzaroni is working on EU-funded projects exploring alternative recommendation algorithms for social media. Part of that work involves simulating real social media platforms to test different approaches. But he can't accurately simulate X's algorithm with the information that's been released. He can't replicate it. He can't test variations. He can't conduct the kind of research that might identify problems or suggest improvements.

And that's the real loss here. Not just for X users, but for the broader AI and social media research community.

The Creator Problem: False Confidence and Viral Theories

When X released the algorithm code, content creators immediately pounced. They started posting supposed "secrets" for gaming the system, with threads accumulating hundreds of thousands of views. These weren't careful academic analyses. They were confident assertions based on a superficial reading of incomplete information.

"They can't possibly draw those conclusions from what was released," Thickstun warns.

But here's the thing about viral theories: they don't need to be right to influence behavior. A creator reads a thread claiming that X rewards "conversating." They adjust their content strategy. They post more casual, conversational threads. Whether the algorithm actually rewards that or not becomes secondary to the fact that thousands of creators are now changing how they create based on theories they can't verify.

This is a subtle but important problem. By releasing code that looks auditable but actually isn't, X creates an environment where people make confident claims about how the algorithm works, even when they have no basis for those claims. The appearance of transparency actually enables misinformation about the algorithm.

A truly transparent algorithm release would either give people enough information to make accurate claims, or it wouldn't be released at all. The middle ground—releasing just enough to seem transparent while withholding enough to prevent real understanding—might be worse than saying nothing.

Estimated data shows a significant gap between perceived and actual transparency in algorithm releases, highlighting the illusion of openness.

Comparing X's 2023 and 2024 Releases: A Step Backward

What makes this particularly frustrating for researchers is that X actually provided more useful information in 2023 than in 2024.

Two years ago, X published the weighting system. Those specific numbers—27 retweets equals one reply, 75 retweets equals a reply from the original author—were valuable benchmarks. They showed concretely how the algorithm valued different types of engagement. Researchers could study those choices. Critics could question them. The community could propose alternatives.

None of that information appears in the 2024 release.

Why? X claims security reasons. It's possible that's genuine. If competitors or bad actors understood exactly how X weights engagement, they could potentially craft content specifically designed to manipulate the algorithm. But it's also convenient for X. Without those weights, the algorithm becomes even less auditable.

Moreover, the shift to the Grok-based system fundamentally changed what "weights" even means. In the old system, you could optimize for specific engagement metrics. In the new system, you're optimizing for what an AI model predicts you'll like. Those are profoundly different things.

Consider the implications. Under the old system, a post that got a lot of replies would rank higher because X valued replies highly. The algorithm was transparent about this logic. Under the new system, a post ranks based on whether the Grok model thinks you'd like it. But the model's reasoning is inaccessible. You can't know if it's basing its predictions on engagement history, content quality, network effects, or something else entirely.

The Broader Research Impact: What Scientists Actually Need

Why does this matter beyond X? Why should someone who barely uses X care about the company's algorithm transparency?

Because understanding social media algorithms has implications that extend far beyond social media.

Lazzaroni's research explores how recommendation systems could work differently. What if algorithms actively promoted diverse viewpoints instead of optimizing for engagement? What if they were designed to surface important information instead of sensational information? What if they could be audited by external researchers to verify they weren't amplifying misinformation?

These aren't abstract questions. They're core to how information flows through society. How people encounter news, opinions, and evidence. How polarization develops. How misinformation spreads.

If researchers could study X's actual algorithm—not a redacted version, but the real system—they could publish findings that might inform policy, regulation, or pressure other platforms to change. They could identify specific biases. They could propose concrete improvements. They could build public understanding.

Without access to that information, they're stuck theorizing. They can't test hypotheses against X's actual behavior. They can't publish evidence-based findings about how X's algorithm affects users or society.

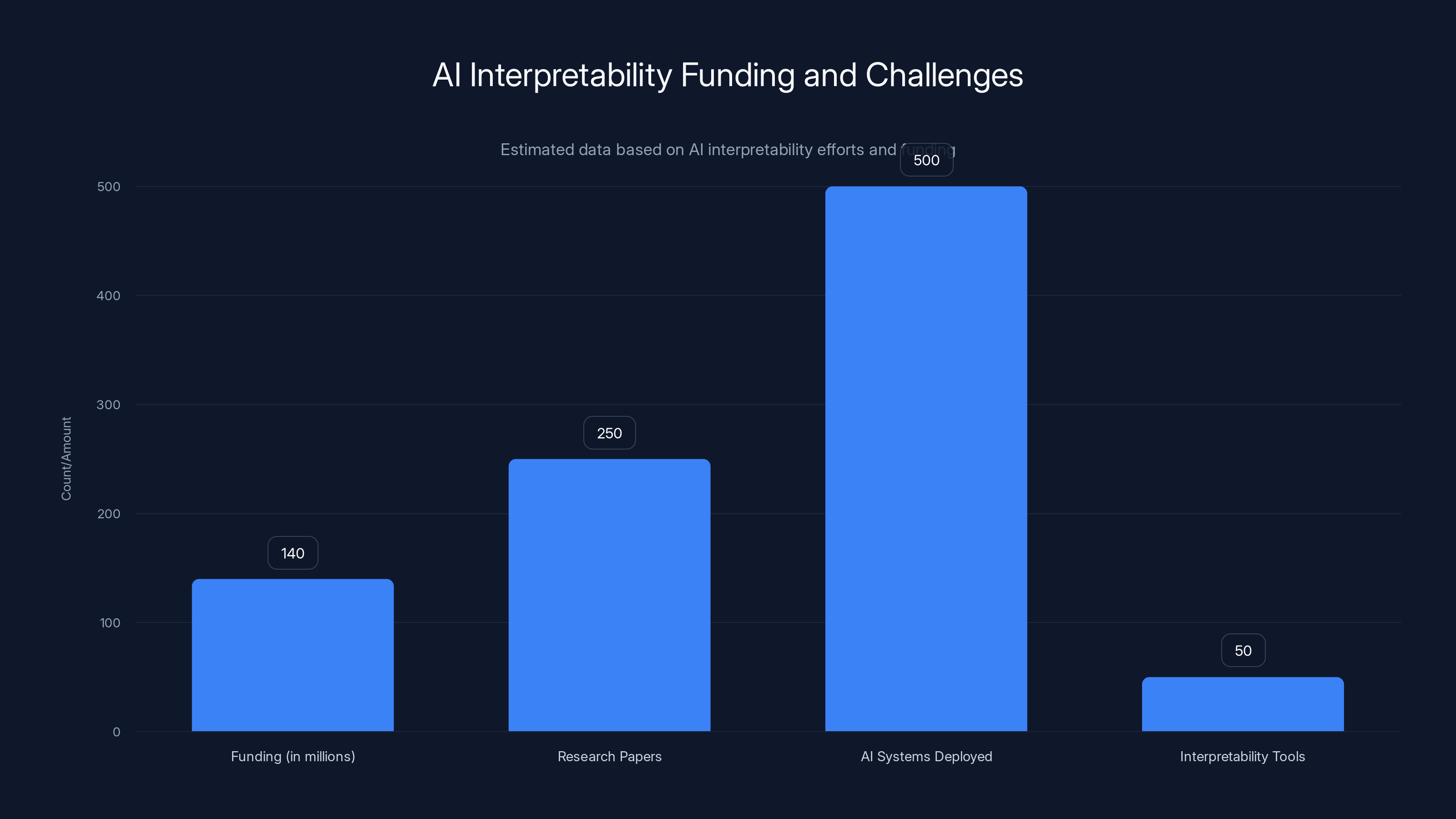

"Being able to conduct research on the X recommendation algorithm would be extremely valuable," Lazzaroni notes. "We could learn things that would apply not just to social media, but to how we think about AI systems more broadly."

That's the real cost of this pseudo-transparency. It's not just that X users don't understand the algorithm. It's that researchers who could improve algorithms, inform policy, and help society make better choices about AI—those researchers are locked out.

Estimated data shows significant funding ($140M) and research efforts (250 papers) in AI interpretability, yet only a fraction of deployed systems have interpretability tools.

Real Algorithmic Transparency: What It Would Actually Look Like

So what would genuine transparency look like? What would X have to release for researchers to actually audit the system?

First, the complete training dataset, or at least a representative sample that shows what data the algorithm was trained on. This is the foundation. Everything else flows from understanding what patterns the model learned.

Second, the actual machine learning models. Not the code that calls the models. The models themselves. This is technically possible—researchers have figured out ways to make neural networks more interpretable without fully compromising security.

Third, the weighting mechanisms or decision rules that apply to the model's outputs. Even if you can't fully understand what the model predicts, you can understand how those predictions get used to rank content.

Fourth, real-world test data. Here's what we predict users will engage with, and here's what they actually engaged with. This lets researchers measure whether the algorithm works as intended.

Fifth, a commitment to external audit. Not just publishing code, but actually allowing independent researchers to study the system under controlled conditions. To test hypotheses. To publish findings.

Final element: transparency about changes. When the algorithm changes, publish what changed and why. This lets the research community track evolution and understand trade-offs.

None of this would require X to surrender competitive advantage. Companies protect their proprietary training data all the time. But they could release enough that external researchers could meaningfully study the system.

The fact that X hasn't suggests they don't want that level of scrutiny. Or they've calculated that the PR value of claiming transparency exceeds the risk of being questioned by researchers.

The Neural Network Problem: Why Even Engineers Don't Fully Understand Modern Algorithms

To understand why this matters, it helps to understand what's actually happened to recommendation algorithms over the past few years.

Ten years ago, algorithms were mostly built from rules and formulas. Facebook showed you posts from people you engaged with most. YouTube promoted videos with high watch time. These systems had flaws, but they were fundamentally comprehensible. You could understand the logic.

Somewhere along the way, things shifted. Companies started using machine learning. Instead of hand-coded rules, algorithms learned to optimize for engagement by finding patterns in user behavior. This worked better in some ways—algorithms got smarter at predicting what would actually interest you.

But it introduced a new problem. The learned patterns exist in mathematical space. When an engineer asks the algorithm "why did you recommend this post to this user?" the algorithm can't explain. It found a pattern that correlates with engagement. The pattern is real. The recommendation works. But the reasoning is inaccessible.

This is sometimes called the "interpretability problem" or the "black box problem." It's not unique to recommendation algorithms—it affects medical AI, autonomous vehicles, loan approval systems, and countless other applications.

Grok, the model X uses for recommendations, is a large language model. These are especially opaque because they're trained on such enormous datasets with so many parameters that even the people who built them can't fully explain what they've learned.

Thickstun puts it starkly: "More and more of the decision-making power of these algorithms is shifting not just out of public view, but actually really out of view or understanding of even the internal engineers that are working on these systems."

This has profound implications. If even the engineers don't fully understand how the algorithm makes decisions, how can you audit it? How can you verify it's not biased? How can you make it better?

The standard approach in this situation is to increase external oversight. Since the system is opaque to everyone, including its creators, you need independent researchers testing it, looking for failure modes, publishing findings.

X's approach seems to be the opposite: reduce external oversight by releasing code that looks auditable but isn't.

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of the audience perceived X's code release as a PR move rather than genuine transparency.

How This Compares to Other Platforms and Regulatory Expectations

X claims to be unique in releasing its algorithm at all. And that's technically true—Meta, Google, TikTok, and others haven't published equivalent code. But the comparison needs context.

Some of that silence might be strategic. Some might be because those algorithms are even more proprietary or tightly integrated with other systems. But it might also be because those companies decided that the PR value of claiming transparency wasn't worth the complexity of releasing code that doesn't actually enable meaningful oversight.

There's also regulatory context. In Europe, the Digital Services Act is starting to require platforms to provide more information about their algorithms. In the US, regulators and lawmakers have been asking for more transparency. By releasing code, X can claim it's already being transparent—heading off potential requirements to provide actually useful information.

Forecast this forward a few years. As AI systems become more central to everything from hiring to healthcare, regulation will likely tighten. Companies will face more pressure to explain how their algorithms work and to enable external audit.

X might be setting a template: release something that looks like transparency, claim it proves you're committed to openness, then argue that you've already satisfied concerns about the black box problem.

It's clever. It's also not actually transparency.

What the Shift to AI Means for Understanding Algorithms

One more thing to consider: this problem is going to get worse before it gets better.

As more of these systems rely on large language models and other AI approaches, algorithms become harder to understand, not easier. The neural networks are trained on so much data, with so many parameters, that interpretability becomes a genuine scientific challenge, not just a policy problem.

Researchers are working on this. There's a whole field called "AI interpretability" focused on making neural networks more transparent. But they're fighting against the fundamental properties of how these systems work.

Meanwhile, companies are deploying these systems at scale. X is using Grok for recommendations. Other platforms are using similar approaches. Each of these systems is shaping what information billions of people see.

Thickstun notes that the challenges we're seeing with social media algorithms are likely to reappear with chatbots and other generative AI systems. "A lot of these challenges that we're seeing on social media platforms and the recommendation systems appear in a very similar way with these generative systems as well. So you can kind of extrapolate forward the kinds of challenges that we've seen with social media platforms to the kind of challenges that we'll see with interaction with Gen AI platforms."

In other words, if we don't figure out how to make recommendation algorithms auditable and understandable, we're setting ourselves up for the same problems with more powerful systems.

X's pseudo-transparency isn't moving us toward solutions. It's moving us away from them.

Estimated data shows demographic bias as the most prevalent in AI training datasets, highlighting the need for diverse data sources.

The Case for Demanding Better

Here's what's frustrating about this situation: it doesn't have to be this way.

X could release meaningful information about its algorithm without seriously compromising competitive advantage or security. Companies release information about machine learning systems all the time. There are ways to sanitize data, redact specific training examples, and share model information while still protecting proprietary approaches.

What's required is commitment. Real commitment, not PR commitment.

The commitment to say: "Our algorithm is important to society. People deserve to understand it. We're going to do the work of enabling that understanding." Not by releasing code that creates an illusion of transparency, but by actually making the system auditable.

That would mean releasing training data (or a representative sample). It would mean allowing independent researchers to access the system under controlled conditions. It would mean publishing information about design decisions and trade-offs. It would mean responding to external research findings with transparency and willingness to discuss concerns.

Some companies are moving in this direction. OpenAI publishes research about their models. Google has research divisions studying algorithmic bias. GitHub created a platform where researchers can study code changes.

X could join that category. Instead, it chose the appearance of transparency.

For now, researchers are stuck working with incomplete information. Content creators are making decisions based on misunderstandings. Users are subject to an algorithm they can't meaningfully understand or audit. And X gets to claim it's the most transparent social media company while actually being significantly less transparent than the appearance suggests.

It's a clever move. It's just not real transparency.

FAQ

What is the X recommendation algorithm?

The X recommendation algorithm is the system that decides which posts appear in your feed, in what order, and how prominent they are. Initially based on explicit engagement metrics and mathematical weighting, it now relies on a Grok-based large language model that predicts how likely you are to engage with different posts. This fundamental shift has made the algorithm significantly less transparent and harder to understand even for engineers working on it.

How does the algorithm work based on what X published?

According to the code X released, the algorithm filters posts (removing those more than a day old), considers various engagement signals, and uses a machine learning model to predict your engagement patterns. However, the released code lacks crucial details including the training data, the actual model weights, how different engagement types are valued, and the full decision-making process that happens inside the neural network. This makes it impossible for external researchers to actually replicate or fully audit the system.

Why did X claim the release was a transparency win?

Elon Musk framed the release as a victory because X is technically the only major social media company to publicly share any algorithm code. However, researchers argue this creates a false sense of transparency—the appearance of openness while withholding information essential for genuine understanding. This allows X to claim transparency credentials while maintaining the opacity necessary to prevent meaningful external oversight.

What information is missing from X's algorithm release?

The release is missing several critical components: the training data used to build the Grok model, the actual neural network models themselves, detailed weighting information that was included in the 2023 release, information about model performance and accuracy, and access for independent researchers to test and audit the system. Without these elements, researchers cannot replicate the algorithm or conduct meaningful audits.

How is the new algorithm different from the 2023 version?

The 2023 algorithm used explicit mathematical formulas and weights to score posts based on engagement metrics. X provided specific numbers showing, for example, that a reply was worth 27 retweets. The 2024 algorithm shifted to using Grok, a large language model, to predict engagement rather than calculating it from explicit metrics. This change made the system more opaque because neural network decision-making is inherently harder to interpret than mathematical formulas.

Why would training data be important to release?

Training data is fundamental to understanding what patterns a machine learning model learned. If the data is biased—skewed toward certain demographics, viewpoints, or content types—the model will learn and perpetuate those biases. Researchers like Mohsen Foroughifar at Carnegie Mellon point out that without knowing what data trained the algorithm, it's impossible to audit for bias or understand whether fairness concerns have been addressed. This is one reason regulatory frameworks increasingly require transparency about training data.

Can creators optimize for the algorithm based on the released code?

No. The viral threads offering "strategies" to game the X algorithm are based on misunderstandings of the incomplete code. As John Thickstun notes, people "can't possibly draw those conclusions from what was released." The released code lacks enough information for creators to make accurate strategic decisions about content optimization, yet the appearance of transparency encourages people to act on unverified theories anyway.

How does the black box problem affect algorithm transparency?

Neural networks like Grok learn patterns from training data, but those patterns exist in a mathematical space that resists human interpretation. Even the engineers who built the system can't fully explain why it makes specific decisions. This makes the black box problem fundamental—it's not a flaw that engineering can fix, but a property of how deep learning works. External research becomes even more important when internal teams can't fully understand their own systems.

What would real algorithmic transparency look like?

Genuine transparency would include releasing the training data (or a representative sample), providing actual machine learning models for study, sharing detailed information about design decisions and weighting mechanisms, allowing independent researchers to audit the system under controlled conditions, publishing information about algorithm performance and failure modes, and committing to transparency when changes are made. It's technically possible without surrendering significant competitive advantage.

How does this relate to regulation and the future of AI?

As regulators in Europe (through the Digital Services Act) and potentially in the US push for more algorithmic transparency, companies like X are establishing templates for pseudo-transparency—releasing just enough to satisfy regulatory or PR concerns while withholding information necessary for genuine understanding. This approach becomes more problematic as these algorithms grow more powerful and influential. The challenge of interpreting neural networks will likely apply to next-generation AI systems, making it crucial to establish norms around meaningful transparency now.

Conclusion: The Price of False Transparency

Elon Musk released X's algorithm code and called it a victory for transparency. It was good marketing. It generated headlines. It positioned X as more forthcoming than competitors who've said nothing at all.

But it wasn't transparency. Not the kind that actually helps people understand how the platform works. Not the kind that lets researchers study potential biases or propose improvements. Not the kind that enables regulation based on evidence rather than assumptions.

What X did was release enough information to look transparent while withholding enough to prevent meaningful understanding. The training data is gone. The model weights are hidden. The actual neural networks that make decisions are inaccessible. Weighting information from the previous release was redacted. The code you can see isn't sufficient to replicate or audit the system.

And because the code looks like it should be informative, it creates an environment where people confidently make claims about the algorithm that they can't actually verify. Content creators adjust their strategies based on theories. Researchers can't test hypotheses. Everyone operates with less information than they think they have.

This matters because recommendation algorithms shape what billions of people see. They influence what becomes culturally significant. They affect how misinformation spreads. They embed biases—intentional or not—into information flows that affect society.

As these systems become more powerful, as they shift increasingly toward opaque neural networks, the need for genuine transparency and external oversight grows more urgent, not less.

X's move to release redacted code might satisfy short-term PR concerns. It might even head off some regulatory pressure by allowing the company to claim it's already being transparent. But it moves us away from solving the actual problem: making powerful algorithmic systems genuinely auditable and accountable.

The researchers studying this problem—Thickstun at Cornell, Lazzaroni at the University of Graz, Foroughifar at Carnegie Mellon, and others—they understand what real transparency would look like. They've tried to explain it. They've attempted to work with what was released and found it insufficient.

The choice for X (and eventually for other platforms) is clear: commit to genuine transparency, or admit that the released code was primarily a marketing exercise.

Right now, the evidence suggests the latter. And that's the real problem with X's algorithm release. It's not that X is being deceptive. It's that the company chose the appearance of transparency over the substance of it, and that choice has consequences that extend far beyond one platform.

Making truly transparent algorithms isn't impossible. It just requires prioritizing public understanding over the convenience of opacity. X had the opportunity to set that example. Instead, it chose to show how smart a company can be about claiming transparency without actually providing it.

For now, researchers will keep trying to understand these systems with incomplete information. Content creators will keep acting on unverified theories. Users will keep operating without real insight into why they're seeing what they see. And companies will keep getting credit for transparency they haven't actually provided.

That's not a victory for openness. It's a masterclass in its illusion.

Key Takeaways

- X's published algorithm code appears transparent but lacks training data, model weights, and critical details needed for genuine external audit

- The algorithm shifted from mathematical formulas (2023) to Grok-based neural networks (2024), making it fundamentally more opaque and harder for anyone to understand

- Without access to training data, researchers cannot identify or audit for algorithmic bias, a core concern for fairness and accountability

- Content creators are making confident optimization decisions based on the released code, though researchers warn the code doesn't contain enough information to support such claims

- The challenges in understanding recommendation algorithms will likely reappear in next-generation AI systems, making genuine transparency increasingly important

Related Articles

- How Government AI Tools Are Screening Grants for DEI and Gender Ideology [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Keeps Generating Nonconsensual Intimate Images [2025]

- Egypt Blocks Roblox: The Global Crackdown on Gaming Platforms [2025]

- How Right-Wing Influencers Are Weaponizing Daycare Allegations [2025]

- VPN Companies Engage UK Government on Children's Online Safety [2025]

- AI Safety by Design: What Experts Predict for 2026 [2025]

![X's 'Open Source' Algorithm Isn't Transparent (Here's Why) [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/x-s-open-source-algorithm-isn-t-transparent-here-s-why-2025/image-1-1770230192966.jpg)