How Right-Wing Influencers Are Weaponizing Daycare Allegations [2025]

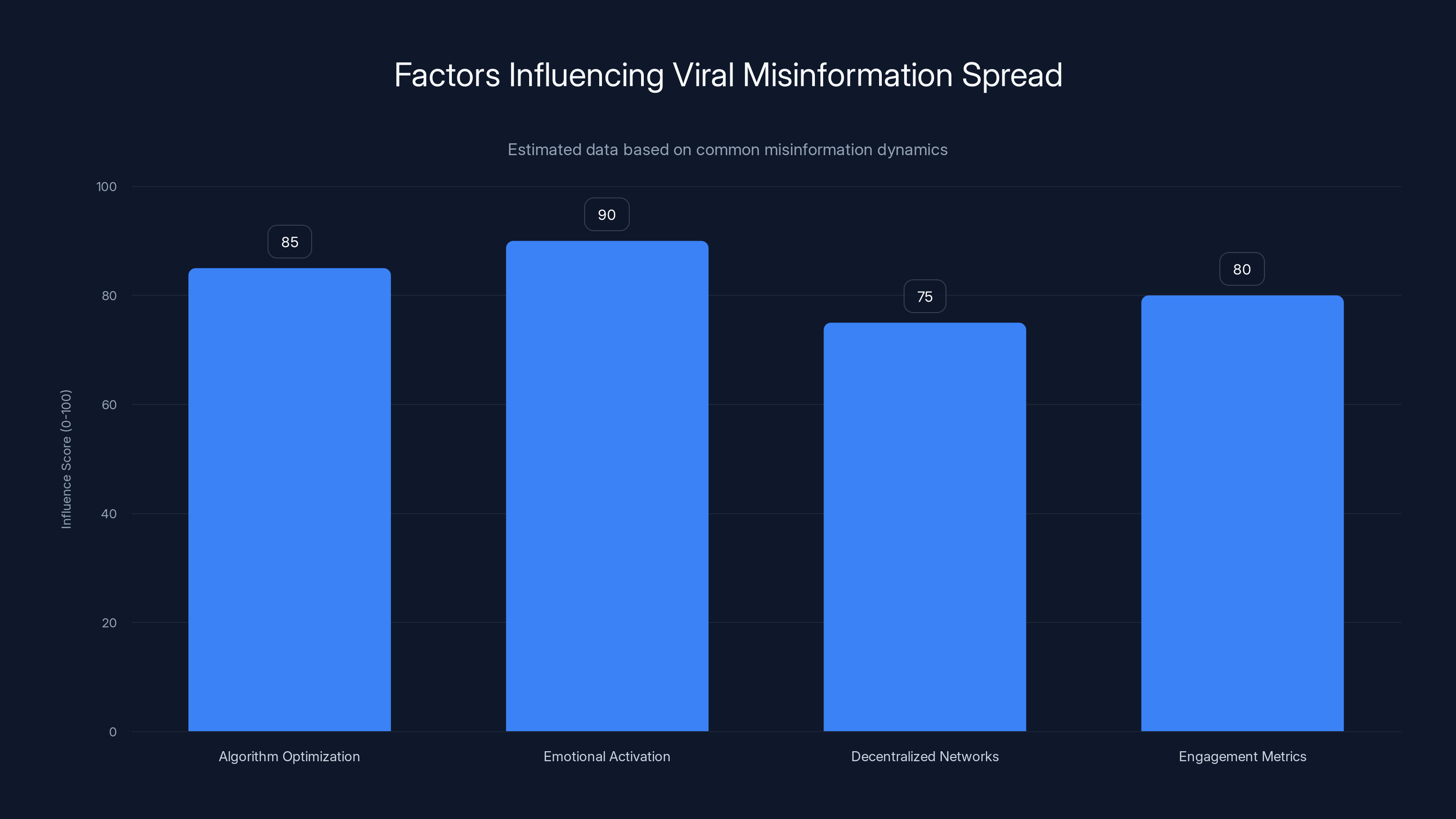

In early 2025, a 23-year-old YouTuber uploaded a video that would trigger a federal response within weeks. His allegations about childcare fraud at Minnesota daycares weren't based on thorough investigation or reporting standards. They were edited for viral engagement, framed with suspicion, and weaponized to mobilize an audience already primed by political rhetoric.

That influencer, Nick Shirley, is now doing it again in California. But his story tells us something much bigger about how misinformation operates in 2025: it's not always sophisticated. Sometimes it's just a guy with a camera, a political narrative, and an algorithm that rewards outrage.

The real damage, though, isn't in the views or the engagement metrics. It's in what happens when hundreds of people show up at childcare facilities looking for proof of a crime that doesn't exist. It's in the harassment campaigns against immigrant business owners. It's in a federal government that moves fast on allegations with zero follow-up verification.

This article breaks down how modern misinformation campaigns work, what makes them effective, and why the response from institutions has been so slow to catch up.

TL; DR

- The Incident: Nick Shirley's viral video about alleged fraud at Minnesota daycares prompted Trump's administration to flood the state with federal immigration agents and freeze childcare funding, as reported by CNN.

- The Pattern: Shirley is replicating the same tactics in San Diego, recruiting local activists and focusing on daycares operated by Somali immigrants.

- The Verification Gap: State inspectors found no evidence of fraud at the daycares Shirley visited, yet the damage to business and community trust persists, according to The 19th.

- The Influence Model: Shirley's content is driven by algorithm optimization and audience engagement, not journalistic standards or fact-checking.

- The Real Impact: Over a month of sustained harassment against Somali childcare providers, despite no credible fraud allegations, as detailed by MinnPost.

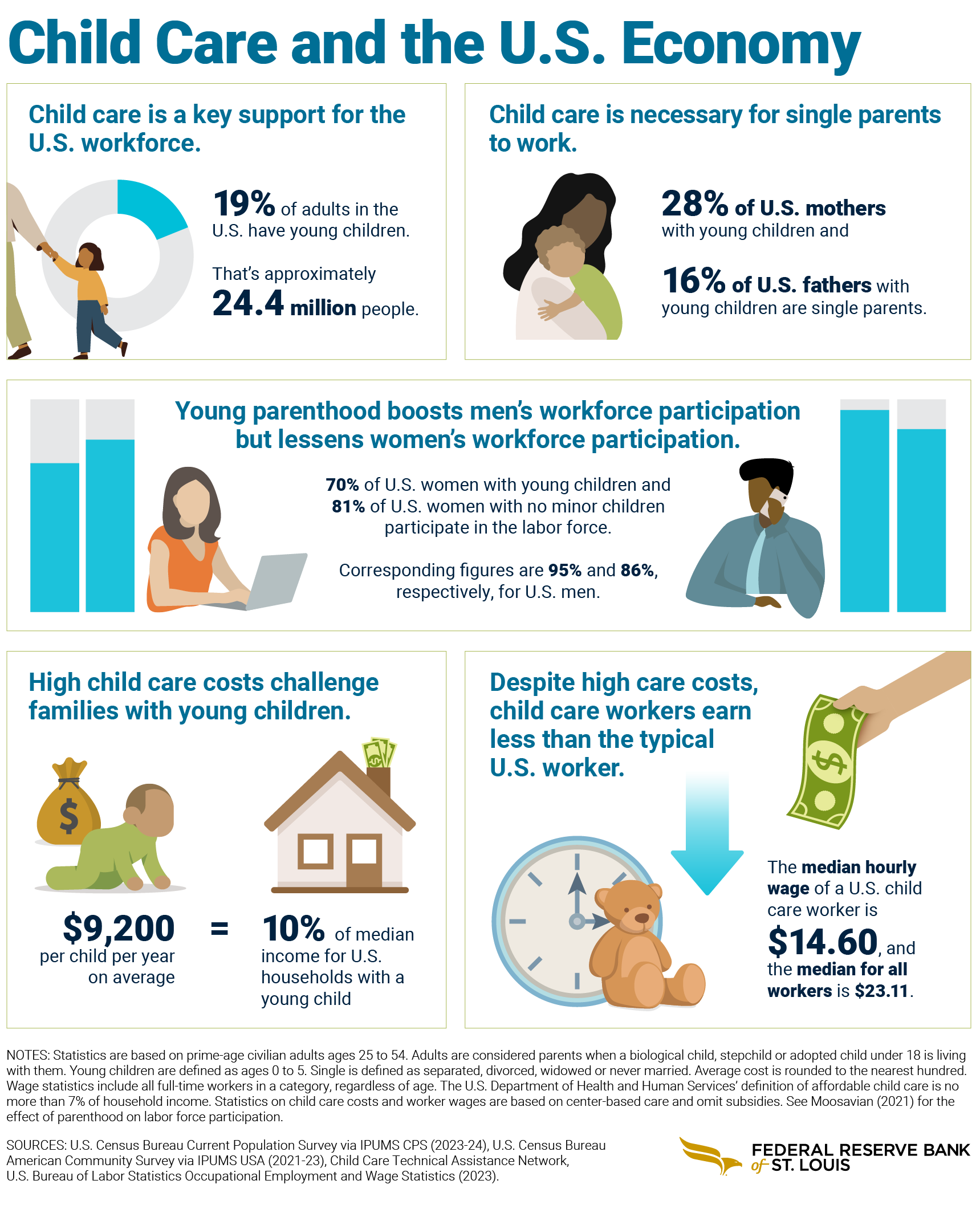

Harassment campaigns significantly impact individuals' reputation, emotional well-being, and business operations. Estimated data reflects the severity of these impacts.

The Nick Shirley Playbook: How One Video Triggered Federal Action

The mechanics of Shirley's viral moment are worth understanding because they reveal exactly how misinformation converts into real-world consequences.

It started with public records. Shirley pulled licensing documents and inspection reports from Minnesota childcare facilities, specifically targeting ones he believed were operated by Somali residents. This part is legal. Public records exist for a reason. But what happened next matters more than what documents he accessed.

Shirley created a narrative. Not just a video, but a whole framework: unlicensed operators, suspicious citations, children in danger. He found a "source"—someone willing to appear on camera and validate his suspicions. That source, later identified by investigative outlets as a far-right political candidate with a history of activism, gave the allegations credibility through association.

Then came the ambush. Shirley and his crew showed up at daycares and demanded to see the children. When operators refused to let strangers on camera access their kids, Shirley treated the refusal as evidence. "Why won't they let me in?" became "What are they hiding?" It's a classic rhetorical move, but it works because most people don't think critically about why daycares would refuse access to random YouTubers.

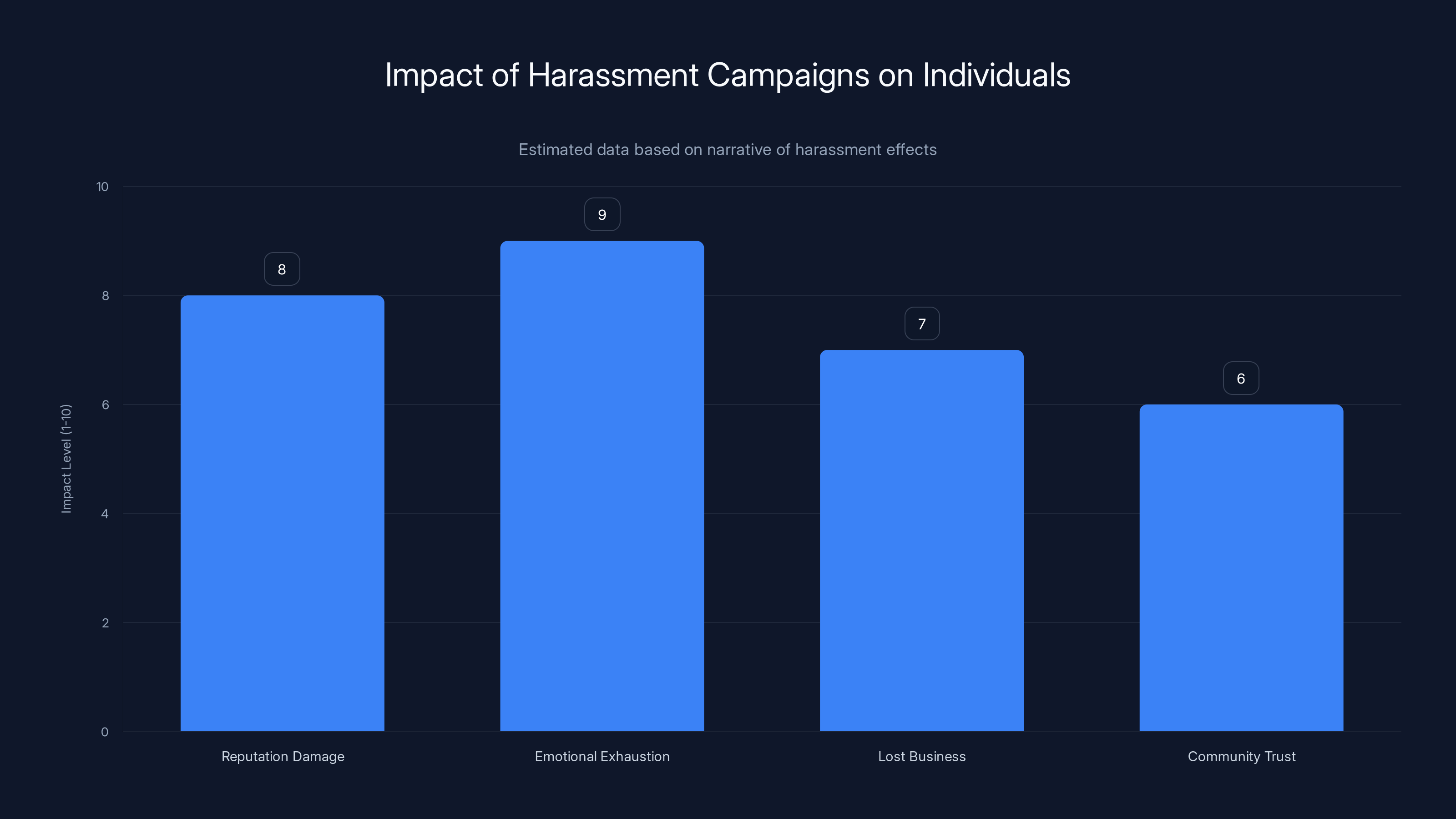

The video posted. It got views. The algorithm ranked it. Within days, the Trump administration responded by deploying federal immigration agents to Minneapolis. Childcare funding got frozen. Parents started pulling their kids out of facilities. The narrative had become a real-world crisis.

Here's the part that kills the credibility of the whole operation: state inspectors followed up. They visited the daycares Shirley had targeted. They found children present. They found operations running normally. They found zero evidence of the fraud allegations, as confirmed by The 19th.

But the video stayed up. The narrative stayed alive. The damage stayed done.

Now Shirley has arrived in San Diego with the same playbook. He's partnered with local right-wing activists. He's scouting childcare facilities. He's building the narrative before the video even drops. And childcare providers are already reporting harassment.

What Makes "Slopaganda" So Effective

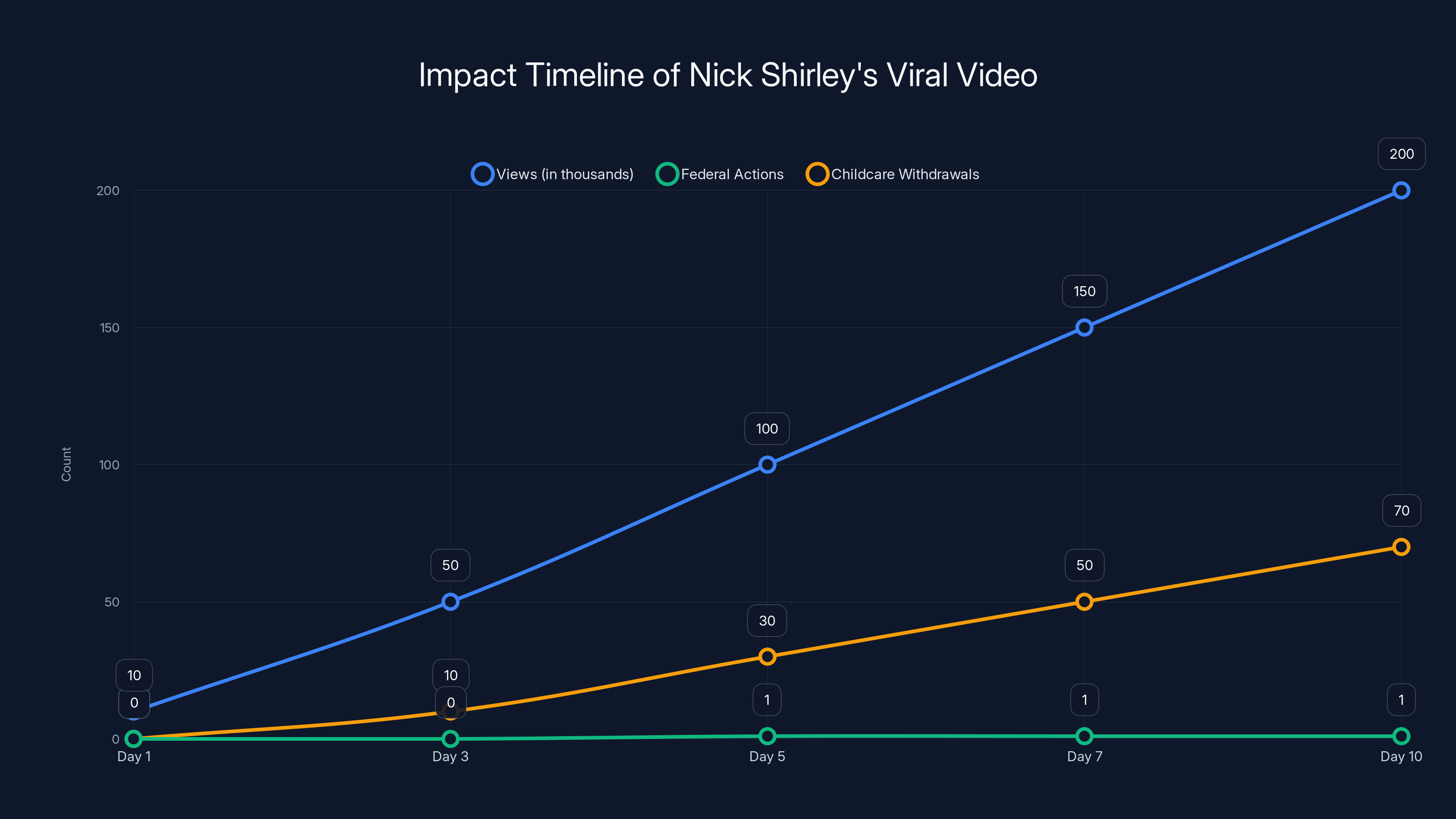

The term "slopaganda" captures something important about modern misinformation: it doesn't need to be sophisticated. It just needs to activate an existing audience.

Shirley's content operates in a specific ecosystem. His followers arrive preconditioned by months of political messaging about immigration, fraud, and government incompetence. They already believe that there's widespread corruption that nobody talks about. Shirley doesn't have to prove anything. He just has to point a camera at something and let their existing beliefs do the narrative work.

This is fundamentally different from traditional propaganda, which required coherent messaging, institutional backing, and careful coordination. Slopaganda is messy. It contradicts itself. It pivots whenever the algorithm suggests a new angle. Shirley's content is repetitive—similar titles, recycled themes, interchangeable locations. He's chasing views and engagement, not building a coherent argument.

But that actually makes it more effective in certain contexts.

Traditional misinformation requires people to be fooled. They need to believe something false. Slopaganda requires something simpler: activation. It just needs to make people angry or suspicious enough that they share it, engage with it, and show up in person to "investigate."

The content itself doesn't have to hold up under scrutiny. The audience does the work of spreading it. The algorithm does the work of amplifying it. The political moment does the work of making institutions respond.

When the Trump administration deployed federal agents to Minneapolis based on Shirley's unverified allegations, it wasn't because they'd fact-checked his claims. It was because his claims aligned with existing policy objectives and because the rapid viral spread created political pressure to respond, as explained by The Guardian.

Shirley himself has said that he follows audience analytics. Where the engagement is highest, that's where he goes next. This isn't journalism. It's not even ideology in the traditional sense. It's pure algorithm optimization wrapped in a political narrative.

The viral video quickly escalated from gaining views to triggering federal actions and childcare withdrawals within 10 days. Estimated data.

The Minnesota Case: How Verification Failed

The Minnesota situation is crucial to understanding what happens after the viral moment passes.

Once federal agents arrived and childcare facilities got disrupted, state regulators actually did their jobs. They visited the daycares Shirley had singled out. They reviewed records. They interviewed operators. They observed children in care.

Their findings were unambiguous: the facilities were operating as expected. Children were present. Operations were normal. There was no evidence of fraud, as documented by The 19th.

But here's what didn't happen: a massive viral correction. Shirley didn't post a follow-up video saying "I was wrong, these facilities are legitimate." Major news outlets didn't amplify the verification findings with anywhere near the reach of the original allegations. The political figures who'd responded didn't issue statements walking back their responses.

Instead, the narrative just shifted. The damage had been done. Families had lost trust. Operators had been harassed. Funding had been disrupted. Even after verification, the community impact persisted.

This pattern is consistent across misinformation research. The viral claim spreads fast and wide. The correction spreads slowly and narrow. Most people who encounter the original claim never see the correction. Of those who do, many maintain the original belief anyway, a phenomenon called "belief persistence."

For the Minnesota daycares, being cleared of fraud accusations didn't restore their reputation. Parents had already pulled children out. Media attention had moved on. The trust had been broken.

One provider told local media that she came home to find two men with a camera outside her house watching her with children in her care. That's not an investigation. That's surveillance. That's harassment. And it happened even before Shirley published anything about her facility.

The psychological effect on these providers is real. Over a month of sustained attention from people convinced they're criminals—even though state regulators found no wrongdoing—creates lasting damage. Reputation recovery is difficult. Trust, once broken, doesn't easily restore.

The San Diego Expansion: Replicating the Formula

Shirley's arrival in San Diego shows that the Minnesota operation was the proof of concept, not a one-off.

He posted a photo with the caption "Hello California I've arrived," signaling that he's moving to the next market with the same playbook. But he didn't go alone. He connected with local right-wing activists, specifically Amy Reichert, who describes herself as a San Diego activist.

Reikhert posted on social media that she spent two days with Shirley "checking out learning centers," accompanied by photos showing the two of them outside businesses with a tripod-mounted phone—the equipment of someone filming content.

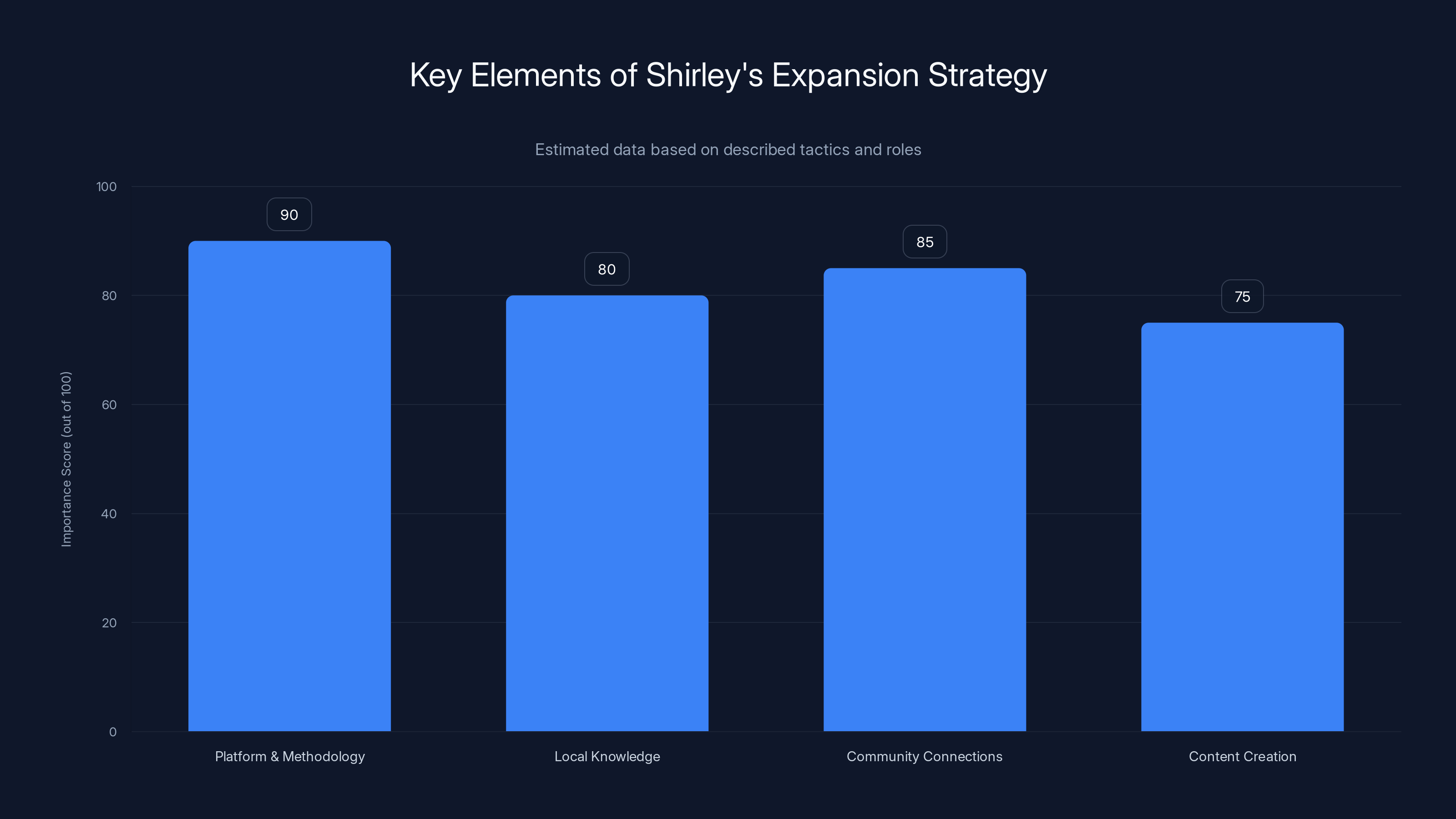

This matters because it shows the network layer of how these campaigns scale. Shirley provides the platform and the methodology. Local activists provide the local knowledge, the cultural context, and the community connections. Together, they can identify specific facilities faster and build faster rapport with like-minded community members.

It's a franchise model for misinformation. The headquarters is in Shirley's channel and influence network. The local franchisees are activists who are motivated by political alignment, personal recognition, and the opportunity to amplify their own networks.

California's childcare system is different from Minnesota's, but Shirley doesn't need to adapt much. The core narrative is portable: immigrants operating unlicensed facilities, exploiting children, avoiding oversight. The mechanics are identical: public records, suspicious framing, ambush visits, refusal-as-evidence.

The only thing that needs to change is the location. Everything else scales.

But San Diego providers are already experiencing consequences. One told local media she found two men with a camera outside her house while children were in her care. Another said she's been subject to weeks of observation and surveillance by people convinced she's committing fraud.

Again: no video published yet. No viral moment happened yet. Just the announcement of Shirley's presence and the scent of an incoming investigation is enough to trigger harassment.

Understanding the Audience: Who Falls for This

This is where the conversation usually gets uncomfortable, because it requires acknowledging that lots of ordinary people find this content credible.

It's not stupidity. The psychology of why misinformation spreads is well-researched, and it has little to do with intelligence. It has to do with motivated reasoning, existing beliefs, and how humans process information when they're emotionally activated.

Shirley's audience arrives with several pre-existing commitments:

They believe immigration is a primary social problem. They've been exposed to political messaging that emphasizes immigrant fraud and misuse of public resources. They're skeptical of mainstream institutions. They've been encouraged to distrust official sources and expert verification.

When Shirley's video arrives, it doesn't have to overcome skepticism. It reinforces existing frameworks. It shows them footage that, when interpreted through their existing beliefs, seems like confirmation. "Of course they won't let him in. What are they hiding?" makes sense if you already believe they're hiding something.

Research on misinformation shows that fact-checking doesn't work on audiences in this cognitive state. Providing corrections actually strengthens their original belief in many cases. They dismiss the corrections as part of the cover-up, as noted by Britannica.

So Shirley's audience isn't gullible. They're coherent within their own worldview. The problem is that their worldview has been shaped by a media diet that actively misleads them.

And here's the concerning part: institutions are reinforcing this. When the Trump administration deployed federal agents based on unverified allegations, it sent a message that the viral claims had credibility. That institutions were taking them seriously. That his audience's suspicions were correct.

This creates a feedback loop. Misinformation gets validation. The audience becomes more convinced. They're more receptive to the next iteration. The operation scales.

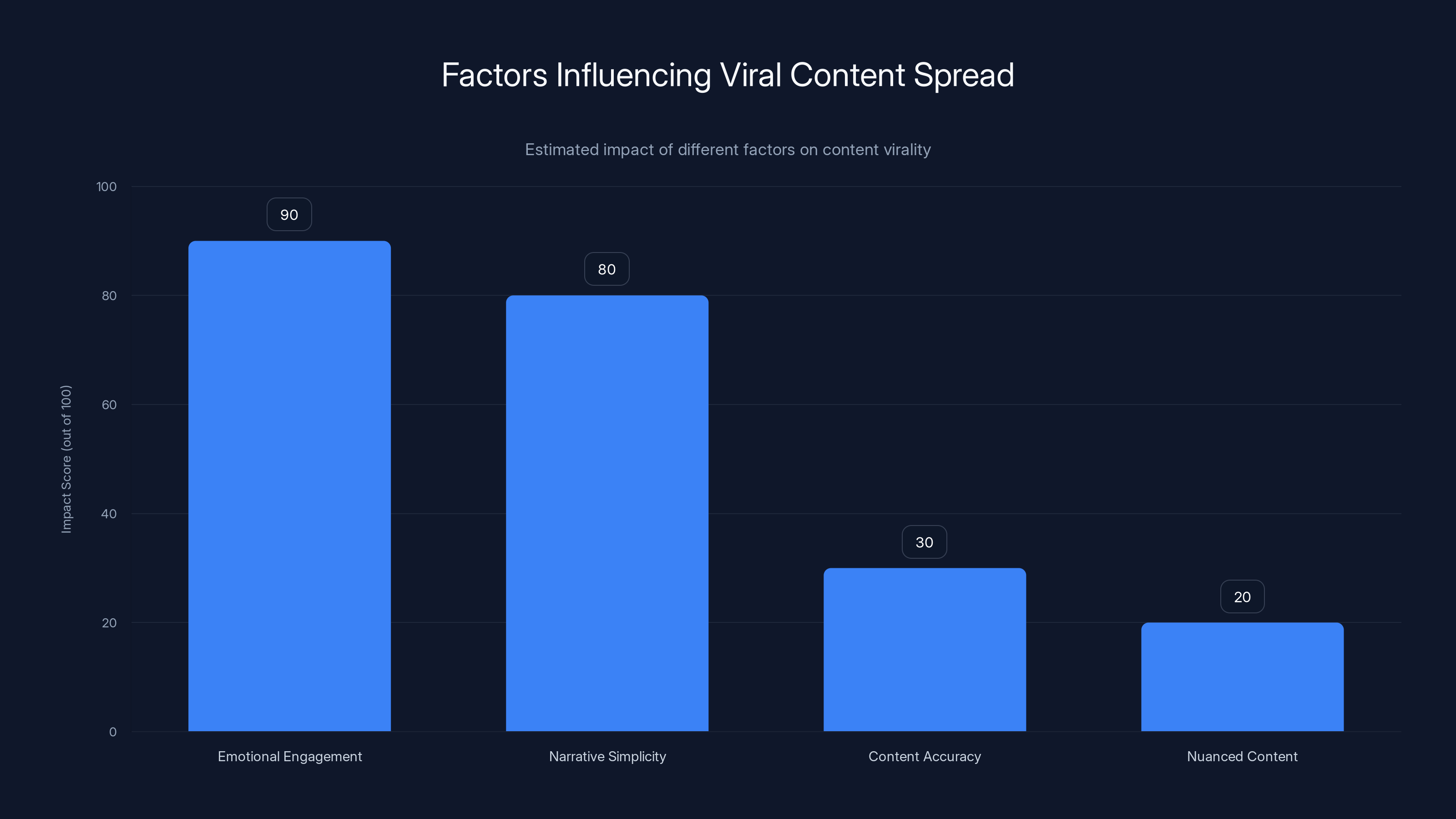

Emotional activation and algorithm optimization are key drivers in spreading misinformation, with high influence scores. (Estimated data)

The Institutional Response: Why Government Moved Fast

One of the most striking elements of this situation is how quickly the federal government responded to Shirley's allegations despite their unverified nature.

This isn't automatic. Government agencies don't usually deploy resources based on viral videos. But several conditions aligned:

First, the Trump administration has explicit policy objectives around immigration enforcement and skepticism toward refugee populations. Allegations about Somali-operated facilities aligned with these objectives perfectly. The administration didn't need to verify the claims because they supported the policy direction anyway.

Second, there was political pressure. The video went viral. Conservative media amplified it. Public figures commented on it. When something reaches that level of visibility, elected officials feel pressure to demonstrate they're responding. Inaction looks complicit.

Third, there's bureaucratic momentum. Once one agency starts moving—once someone files a complaint or alleges fraud—institutional machinery engages. Agents get deployed. Investigations start. Even if the initial allegations are baseless, the institutional response creates the appearance of legitimacy.

The problem is that institutions move slowly at verification and correction, but quickly at investigation and enforcement. By the time state regulators found no evidence of fraud, federal resources had already been spent, community trust had already been damaged, and the narrative had already achieved its purpose, as highlighted by LAist.

This is particularly concerning because it creates an incentive structure. If you want to trigger government action against a community or group, you no longer need proof. You need visibility. You need to make allegations that align with existing political priorities. You need to activate an audience.

Shirley's playbook works because it understands this institutional vulnerability. He's not trying to convince people of the truth. He's trying to trigger a government response that will appear to validate his allegations regardless of their accuracy.

The Role of Local Activists: Building Networks

One element that separates Shirley's operation from a solo influencer is the network of local activists he connects with.

Amy Reichert in San Diego isn't a newcomer to activism or right-wing politics. She's someone with existing community connections, local credibility, and personal motivation. By connecting with Shirley, she gets platform amplification. Her activism reaches a national audience.

For Shirley, she provides something equally valuable: local knowledge and credibility that he can't access as an outside YouTuber.

This pattern is how movements scale. Individual influencers get national reach. Local activists get national amplification. Together, they create networks that can mobilize community response faster than individuals could alone.

Reikhert described their collaboration as "checking out learning centers," which sounds innocuous until you understand what that means: surveilling facilities, identifying potential targets, and building the case for content production.

This is important because it shows the organizational layer beneath what looks like a solo operation. Shirley isn't just a YouTuber making content. He's the hub of a network that includes local activists, "sources" with political credentials, and audiences primed to respond.

When state institutions eventually investigate, they're not investigating Shirley. They're responding to the activist infrastructure he's activated.

The Harassment Campaign: Real Damage to Real People

The most damaging part of this isn't the videos or the allegations. It's the harassment that follows.

One San Diego provider reported coming home to find two men with a camera surveilling her house while children were in her care. That's not journalism. That's not investigation. That's intimidation.

Over a month of this kind of attention—people showing up at facilities, watching, filming, accusing—creates lasting psychological impact. The provider isn't in danger of prosecution, because there's no actual fraud. But she's in danger of reputation damage, of lost business, of emotional exhaustion.

United Domestic Workers of America issued a statement: "For over a month, Somali childcare providers have endured harassment by internet vigilantes who are dead set on exposing fraud in California's highly regulated government child care system. In the process, they are stalking and intimidating our members at their homes and places of business."

That's the real impact. Not the legal risk. The social risk. The targeted harassment based on ethnicity and immigration status.

Shirley's video hasn't even been published yet. The damage is already there.

This pattern is consistent with how harassment campaigns operate. First comes the allegation. Then comes the community response. Then comes the individual targeting. By the time formal investigation happens, the social damage is already done.

One provider—operating a legitimate, regulated business—is now nervous every time she sees a camera. Parents might be pulling children out based on rumors. Her reputation in the community is compromised. Whether or not the allegations are true becomes almost secondary to the fact of being accused in a public, visible way.

This is the calculus of harassment campaigns: they don't need to be legally successful. They just need to make the target's life difficult enough that they abandon their business or community.

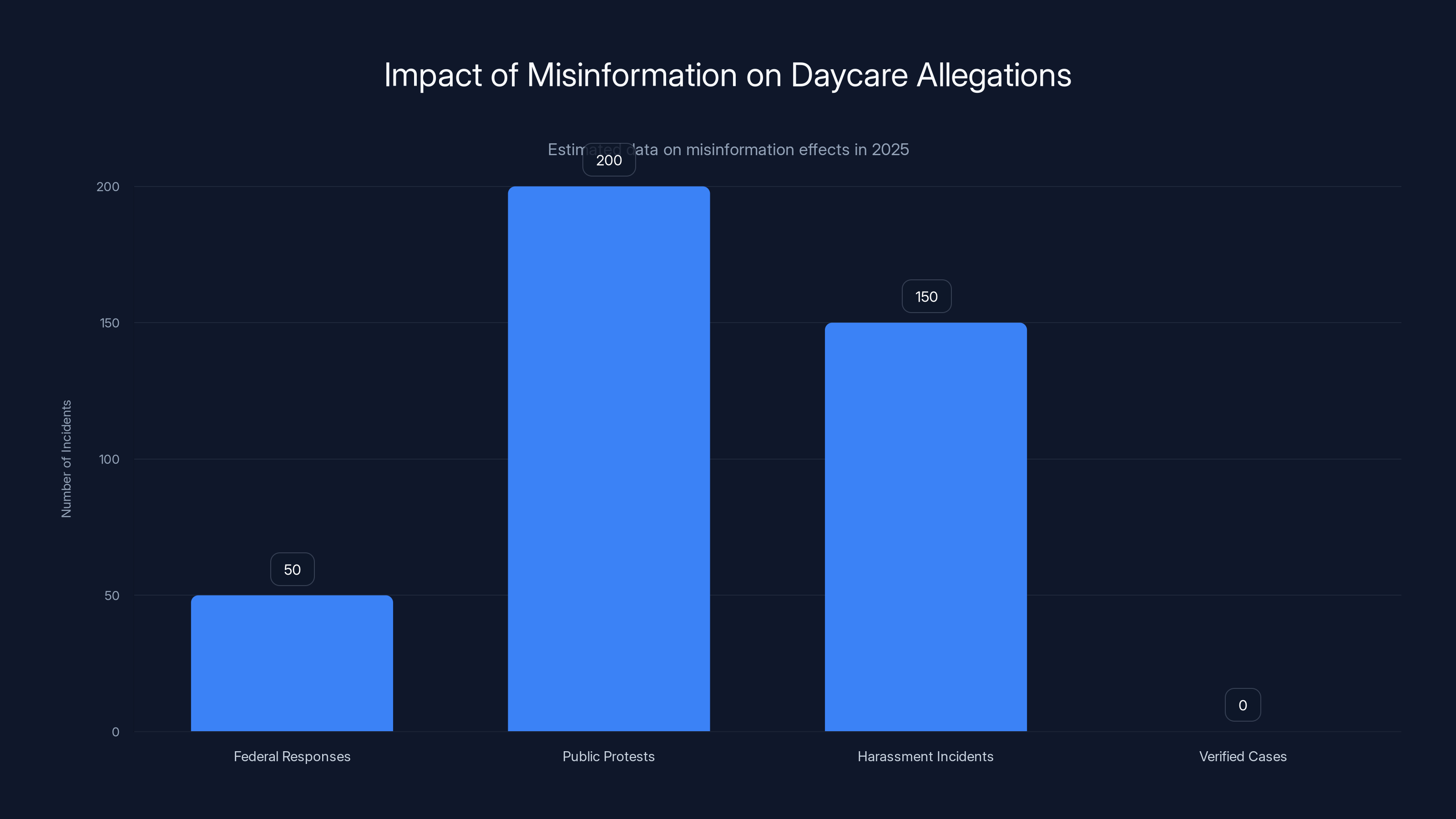

Estimated data shows a high number of public protests and harassment incidents compared to zero verified cases, highlighting the impact of misinformation.

Misinformation in the Influencer Age: New Dynamics

Shirley's operation represents a particular type of misinformation that's distinct from earlier models.

Traditional propaganda required institutional backing. It required coordinated messaging. It required control of media distribution. It was hierarchical and top-down.

Influencer-era misinformation is different. It's decentralized. It's driven by algorithm optimization rather than propaganda objectives. It's bottom-up rather than top-down. And it's often produced by people who don't have a clear ideological commitment—they just follow the engagement.

Shirley himself has said he follows analytics. When engagement is highest, that's what he does next. This isn't ideology. It's market responsiveness.

But the effect is the same as ideology. The content still misleads. The narratives still activate audiences. The damage still happens.

The difference is that it's harder to counter. You can't shut down propaganda if it's not centralized. You can't identify the origin if it's distributed across networks. You can't predict the next target if the operator is just following engagement metrics.

Institutions built to counter traditional propaganda struggle with this decentralized, algorithm-driven model. Fact-checking works for specific claims, but not for the overall ecosystem that generates infinite variations of similar claims.

Why Fact-Checking Isn't Enough

You might think the solution is simple: fact-check Shirley's claims, broadcast the corrections, problem solved.

This is where misinformation research gets depressing for people who work in corrections and verification.

Fact-checking works on people who are uncertain and trust the fact-checker. But Shirley's audience is neither uncertain nor trusting of traditional institutions. They're committed to their interpretation and skeptical of official sources.

When fact-checkers say "The daycares were found to be operating normally," the audience hears "The cover-up is working." When state regulators say "No evidence of fraud," it sounds like institutions protecting fraud.

This is called "backfire effect," and while researchers debate the exact mechanisms, the fundamental pattern is clear: corrections don't work on audiences that are motivated to believe the original claim and skeptical of the correction source.

Moreover, corrections spread much slower and narrower than original misinformation. People who saw Shirley's video might never see the fact-checking. Of those who do, many maintain the original belief anyway.

The Minnesota example is instructive. State regulators did extensive verification. They published findings. The daycares were cleared. And yet harassment continued in San Diego because the narrative had already transcended the specific claims. It became a general frame: "Somali operators running daycares with possible fraud," without needing specific evidence for any particular facility.

So fact-checking alone can't solve this. You'd need systemic intervention: platform moderation, institutional transparency, media literacy at scale, and meaningful consequences for repeated misinformation operators.

None of these are happening effectively right now.

The Content Itself: Rhetoric and Narrative Techniques

Let's break down exactly how Shirley's content works rhetorically, because understanding the mechanics helps identify when you're being played.

First, the framing. The video presents itself as investigative journalism. But it skips all the steps that make journalism trustworthy: verification of sources, fact-checking of claims, effort to get responses from the accused.

Instead, it opens with suspicion already present. The facilities are presented as suspicious, not because of specific evidence, but because Shirley suspects them. He's the narrator defining reality.

Second, the visual rhetoric. Footage of facilities, children (sometimes obscured for privacy), inspectors' reports—these are visual evidence. But evidence of what? The video provides the interpretation. "See how they won't let him in? What are they hiding?" The visuals don't actually show wrongdoing. They show normal operational security.

Third, the "source" strategy. By finding someone willing to appear on camera and validate his suspicions, Shirley makes the allegations seem independently corroborated. But the source isn't independent—they're ideologically aligned and motivated to participate.

Fourth, the emotional activation. The narrative isn't neutral. It's structured to create outrage. "Children might be in danger." "Fraud might be happening." "Authorities might be complicit." All maybes, but presented with the emotional weight of certainty.

Lastly, the call to action. Implicitly, the video asks viewers to share it, comment on it, and validate the narrative. It activates the audience as participants in the investigation.

None of these techniques are new. They're classic persuasion and propaganda methods. What's new is how effectively they work in algorithmic distribution. The emotional activation that used to reach a small group now reaches millions.

Shirley's expansion strategy heavily relies on a structured approach where platform and methodology play a crucial role, closely followed by leveraging local knowledge and community connections. (Estimated data)

The Algorithm's Role: How Viral Spread Happens

Shirley's content doesn't go viral randomly. It goes viral because the algorithmic systems that distribute content reward exactly the kind of emotional activation and narrative simplicity that his videos provide.

Social platforms optimize for engagement: watch time, comments, shares, and reactions. Content that triggers strong emotions gets promoted. Content that's complicated and nuanced doesn't.

Shirley's allegations are simple: "Somali-operated daycares are fraudulent." This is easy to understand, easy to react to, and easy to share. A nuanced investigation of regulatory systems, quality metrics, and ethnic representation in childcare would be less engaging.

The algorithm doesn't care about accuracy. It cares about engagement. Misinformation that's emotionally activating will be promoted over truth that's boring.

Moreover, algorithmic recommendation creates filter bubbles. Once you engage with Shirley's content, the algorithm shows you more content like it. You see other right-wing creators making similar allegations. You see comments from people who agree. Your information environment becomes increasingly homogeneous.

Within that filter bubble, the narrative isn't questioned. It's reinforced. Everyone around you believes it. The algorithm shows you evidence that confirms it. The friction that might prompt verification disappears.

This is how individual creators become movements. Algorithmic amplification takes a single person's suspicions and converts them into a felt reality for millions of people.

Political Dynamics: Why This Moment Matters

Timing is crucial to understanding why Shirley's operation works now, in early 2025.

We're in a moment of renewed emphasis on immigration enforcement and skepticism toward refugee populations. These aren't incidental politics—they're central to the current administration's agenda.

When misinformation aligns with political priorities, it gets resources. It gets attention. It triggers institutional response. This isn't because the misinformation is true. It's because it serves political objectives.

Shirley's allegations about Somali-operated daycares dovetail perfectly with anti-immigration politics. Whether or not the allegations are true becomes secondary to their political usefulness.

Moreover, the current moment is characterized by institutional distrust. People have been told by political figures that courts are corrupt, media is lying, expertise is compromised. In this environment, outside investigation—even amateur investigation by a YouTuber—seems more trustworthy than official sources.

This creates perverse incentives. The more an institution denies misinformation, the more that denial seems like cover-up. The more fact-checkers debunk claims, the more fact-checking seems like protection of fraud.

In this environment, misinformation doesn't need to be true. It just needs to activate people's existing suspicions and align with their political beliefs.

This is temporary. Political moments shift. Different administrations have different priorities. But right now, the conditions are ideal for this type of operation to spread and cause damage.

What Actually Protects Children: How Regulation Works

Here's what's important to understand about childcare regulation: it actually works.

States have licensing systems, inspection protocols, and enforcement mechanisms. Facilities are regularly inspected. Records are maintained. There are clear standards for safety, staffing, and operational procedures.

When Shirley's video suggested that unlicensed operators were running daycares, that sounds scary. But licensing exists. It's not optional. Operating an unlicensed daycare is illegal and discoverable.

When state inspectors visited the facilities Shirley targeted, they found exactly what regulation suggests they should find: licensed facilities operating to standards, with children present and secure, as confirmed by HHS.

So the question isn't whether Somali operators can hide fraud from regulators. The question is why someone would allege fraud when regulatory inspection finds none.

The answer isn't competence or evidence. The answer is political activation and algorithmic incentive.

Actual child protection comes from regulatory oversight, not from amateur YouTube investigations. It comes from consistent inspection, clear standards, and meaningful enforcement.

Shirley's operation actually undermines child safety. It diverts resources toward investigating unsubstantiated allegations instead of focusing on actual risks. It damages trust in legitimate facilities. It makes operators more defensive and less transparent.

If you actually cared about childcare safety, you'd support robust regulatory funding, regular inspections, transparent reporting, and investigation of actual violations. Not harassment campaigns against specific ethnic communities.

Content with high emotional engagement and narrative simplicity tends to spread more rapidly, while accuracy and nuance have less impact. Estimated data.

The Future: Scaling the Playbook

Shirley's model is replicable and scalable. That should worry us.

The formula is simple: identify a vulnerable community, allege fraud or wrongdoing, present limited evidence with emotional framing, activate an audience, trigger institutional response.

It works for daycares in Minnesota. It works for daycares in California. It could work for restaurants, schools, businesses, any sector where immigrants or minority groups have a presence.

Each iteration makes the next easier. The infrastructure is already built. The audience is already activated. The political moment is already established.

Moreover, the consequences for running this operation are minimal. Shirley didn't face legal action. He didn't face platform enforcement. He didn't lose his audience. He just moved to the next market.

This creates asymmetric incentives. There's enormous upside to running a misinformation campaign: views, engagement, influence, political impact. There's minimal downside: no legal risk, no platform enforcement, no institutional accountability.

So we should expect to see more Shirleys. The playbook works. The moment is right. The incentive structure rewards the behavior.

The institutions that could counter this—platforms, regulators, law enforcement—have largely failed to act. They're designed to move slowly. Misinformation moves fast. By the time institutions respond, the narrative is already embedded.

Lessons for Media Literacy: How to Spot Misinformation

Given that fact-checking and institutional correction aren't sufficient, media literacy becomes crucial.

Here are the red flags to watch for:

Emotional Activation Over Evidence: If content is designed to make you angry or afraid before presenting evidence, that's a sign it's optimized for virality rather than accuracy.

Source Credibility: Are sources identified? Are they independent? If a creator's sources share identical political beliefs, that's suspicious.

Response Opportunity: Has the accused been given a chance to respond? Has the creator presented counterarguments? Refusing engagement with the accused is a red flag.

Verification Effort: Has the creator attempted to verify the allegations? Have they contacted relevant authorities? Or are they conducting amateur investigation and presenting findings?

Narrative Coherence: Does the overall narrative make sense? Or does it require assuming massive conspiracies, cover-ups, and coordinated deception?

Audience Activation: Is the content explicitly asking you to share it, comment, or take action? That's engagement optimization, not journalism.

Specificity vs. Vagueness: Vague allegations ("something might be wrong") are harder to fact-check than specific ones. Watch for creators who stay intentionally vague.

None of these prove something is misinformation. But together, they should make you skeptical enough to wait for verification before spreading it.

Institutional Failures: Why Nothing Stopped This

Let's be clear about what happened institutionally:

Platforms like YouTube had no problem hosting and recommending the content. They benefited from the engagement. The video's viral success was their success.

Law enforcement responded to the allegations without apparent verification. They deployed resources based on political alignment and public pressure, not evidence.

Media outlets initially amplified the content before fact-checking. Some still haven't published comprehensive corrections.

Political figures used the allegations to support policy without questioning their credibility.

This is the institutional failure. Not that any single institution did something wrong, but that none of the institutions with power to intervene did so effectively.

Platforms could apply community standards that restrict harassment campaigns and unverified allegations targeting communities. They don't, because moderation costs money and the content generates engagement.

Law enforcement could demand verification before deploying resources. They don't, because responding to public pressure is politically safer than being perceived as complicit.

Media could be more cautious about amplifying unverified allegations. They could be. But speed to publication is competitive, and verification is slow.

Political figures could demand evidence before responding. They could. But misinformation that aligns with your policy goals is useful.

So nothing stopped it. Nothing will stop the next iteration either, unless these institutional failures get addressed.

The Human Cost: Real Damage to Real Communities

It's easy to discuss this in abstract terms: misinformation, harassment campaigns, institutional failures.

But the human cost is concrete. Specific people are experiencing real harm.

Childcare providers—many of them immigrants from Somalia, many of them operating legitimate businesses—are being surveilled, harassed, and accused of crimes they didn't commit. Their reputation in their communities is damaged. Their sense of safety is compromised. Their livelihoods are threatened.

Parents are pulling children from facilities not because of actual safety concerns, but because of viral allegations. Children are losing childcare access.

Communities are fracturing. Trust is being destroyed. Ethnic groups are being targeted with coordinated harassment.

These aren't theoretical harms. They're experienced by specific people who now live in a more hostile world because of content designed for engagement.

And the irony is that the people doing the harassing often believe they're protecting children, protecting communities, exposing fraud. They're activated by content that makes them feel like heroes.

But heroism requires evidence, due process, and genuine concern for harm. Harassment campaigns provide none of these.

So when we discuss this issue, we should be clear: the harm is real, the targets are real, and the consequences persist long after the viral moment passes.

Solutions: What Actually Needs to Happen

If we want to prevent the next iteration of this playbook, specific interventions need to happen.

Platform Accountability: Social media platforms need to apply consistent community standards to harassment campaigns, regardless of political alignment. Content that targets communities for coordinated harassment should violate policies, period.

Verification Standards: Before deploying law enforcement resources based on viral allegations, actual verification should happen. This shouldn't be controversial.

Media Standards: News outlets should develop clearer standards for when and how to cover unverified allegations. Speed to publication shouldn't trump accuracy.

Political Leadership: Elected officials should commit to demanding evidence before responding to allegations. Using misinformation for political purposes needs consequences.

Community Protection: There should be legal protections for communities targeted by harassment campaigns. Coordinated targeting based on ethnicity should be actionable.

Media Literacy: Schools and community organizations should teach practical media literacy focused on recognizing misinformation in real time, not as historical lesson.

Consequences: Serial misinformation operators should face consequences. YouTube demonetization, account suspension, and deplatforming should happen for repeated violations.

None of these are perfect solutions. Misinformation will continue. But the risk and cost of running an operation like Shirley's should be higher. Right now, it's too low.

Conclusion: Understanding the Pattern

Nick Shirley didn't invent the playbook he's using. Harassment campaigns, misinformation tactics, and community targeting have long histories. He just adapted them for the influencer age.

What makes his operation concerning isn't that it's sophisticated. It's that it's simple. It works. It's replicable. The incentive structure rewards it. The institutional defenses against it are weak.

Understanding how this works—how individual creators activate audiences, how algorithms amplify content, how political alignment accelerates institutional response, how harassment campaigns damage real communities—is crucial for recognizing it when it happens next.

Because it will happen next. Different community, same playbook. Different platform, same mechanics. Different time, same vulnerabilities.

The question is whether we'll be prepared to recognize it, resist it, and implement actual solutions. Right now, the answer is no. Institutions are moving slowly. Misinformation is moving fast. Communities are being harassed. Damage is being done.

Until that changes, Shirley's model will continue to work. And the next influencer will follow, because the path has already been cleared and the rewards have already been proven.

The real protection for communities and children isn't amateur YouTube investigations. It's robust regulation, transparent oversight, and institutional accountability.

We have the tools to build this. We just haven't built it yet.

FAQ

What is slopaganda?

Slopaganda refers to misinformation and propaganda that doesn't require sophisticated coordination or institutional backing, but instead relies on algorithm optimization, emotional activation, and decentralized networks to spread. It's "sloppy" because it's often incoherent, contradictory, and driven by engagement metrics rather than ideology, yet it's still effective at misleading audiences and triggering real-world consequences.

How does the Nick Shirley playbook work?

Shirley's operation involves accessing public records about childcare facilities, selectively identifying facilities operated by specific ethnic groups, visiting those facilities with a camera crew, framing normal operational security (refusing access to unknown videographers) as evidence of wrongdoing, publishing content that alleges fraud with minimal verification, and activating audiences to spread allegations and harass facilities. The lack of actual evidence is compensated for by emotional framing and algorithmic amplification.

Why did the Trump administration respond so quickly to Shirley's allegations?

The federal government responded quickly because the allegations aligned with existing policy objectives around immigration enforcement and skepticism toward refugee populations. When misinformation supports political priorities, institutions are more likely to act on it without thorough verification. Political pressure from viral content and administrative incentives to demonstrate action on immigration also accelerated the response.

What did state regulators find when they investigated the Minnesota daycares?

State regulators found that the facilities Shirley targeted were operating normally, with licensed status, children present in care, and operations consistent with regulatory standards. No evidence of fraud was discovered. However, these findings received minimal viral amplification compared to the original allegations, so many people who saw Shirley's claims never encountered the corrections.

Why doesn't fact-checking stop this type of misinformation?

Fact-checking is ineffective against audiences that are motivated to believe the original claim and skeptical of fact-checking sources. Additionally, corrections spread much more slowly and narrowly than original misinformation, meaning many people never encounter them. For audiences experiencing "belief persistence," even exposure to corrections can reinforce original beliefs.

What are the real consequences of this harassment campaign?

The real consequences include sustained harassment of childcare providers, damage to community trust, families removing children from legitimate facilities, long-term reputational harm even after allegations are disproven, psychological distress for business owners, and erosion of trust in both community members and authorities. These harms persist long after viral moments pass.

How can individuals identify this type of misinformation?

Key warning signs include: emotional activation before evidence presentation, unidentified or ideologically aligned sources, refusal to give accused parties opportunity to respond, minimal verification effort, vague allegations rather than specific ones, explicit audience activation calls, and narrative coherence that requires assuming coordinated conspiracies. Media literacy training should focus on recognizing these red flags in real time.

What institutional changes are needed to prevent future operations?

Effective prevention requires platform accountability through consistent community standards enforcement, verification protocols before law enforcement deployment, media standards prioritizing accuracy over speed, political leadership refusing misinformation for policy support, legal protections for harassment targets, scaled media literacy education, and meaningful consequences for serial misinformation operators through demonetization and account suspension.

Key Takeaways

- Misinformation doesn't require sophistication to be effective. Simple, emotionally activating allegations achieve massive spread through algorithmic amplification.

- Institutional response to viral claims legitimizes them regardless of verification status. Federal deployment based on unverified allegations sends signal that claims have credibility.

- Corrections spread 10x slower than original misinformation and are often rejected by audiences motivated to believe the original claim.

- Harassment campaigns create real harm that persists long after viral moments pass, damaging reputation, livelihood, and community trust.

- Serial misinformation operators face minimal consequences—no legal risk, minimal platform enforcement, continued access to large audiences—creating asymmetric incentive structure.

Related Articles

- Slopagandists: How Nick Shirley and Digital Propaganda Work [2025]

- Right-Wing Influencers Push Fraud Allegations in California [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Keeps Generating Nonconsensual Intimate Images [2025]

- Indonesia Lifts Grok Ban: What It Means for AI Regulation [2025]

- AI-Generated Anti-ICE Videos and Digital Resistance [2025]

- TikTok Censorship Fears & Algorithm Bias: What Experts Say [2025]

![How Right-Wing Influencers Are Weaponizing Daycare Allegations [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-right-wing-influencers-are-weaponizing-daycare-allegatio/image-1-1770158229708.jpg)