VPN Companies Step Into the Ring with UK Government Over Child Safety

It's not every day you see VPN companies publicly volunteering for government scrutiny. But that's exactly what's happening in the UK right now. Major providers like Nord VPN, Surfshark, Express VPN, and Windscribe are signaling openness to meaningful dialogue with UK regulators about online safety for children.

This isn't some grand love fest between privacy advocates and government officials. It's more like a cautious handshake between two sides that historically haven't seen eye to eye. The VPN industry has long operated in the shadows of regulatory uncertainty, especially when it comes to child protection laws. But pressure from lawmakers focused on keeping kids safe online is forcing a conversation that nobody can ignore anymore.

The UK government's online safety push has intensified significantly over the past two years. With the Online Safety Bill now part of the legislative landscape, regulators are looking more closely at every tool and platform that affects what children can access online. VPN companies suddenly find themselves in the crosshairs, accused by some of enabling harmful behavior while others view them as essential privacy tools.

Here's the thing though: these companies aren't pushing back defensively. Instead, they're stepping forward with an almost surprising level of willingness to engage. This shift suggests something important is changing in how the industry views its relationship with government. Rather than fight every regulation tooth and nail, these players are recognizing that some form of collaboration might actually be better for business long-term.

The stakes are huge. Get this on your radar right now because this conversation in the UK is likely to influence policy decisions across Europe, and eventually, North America too. When major tech players start negotiating with governments about child safety, it sets precedent. It creates frameworks. It establishes what's possible and what's not.

So what's really going on here? Why are VPN companies suddenly eager to talk? And what could meaningful dialogue actually look like?

TL; DR

- VPN Industry Response: Major providers like Nord VPN, Surfshark, Express VPN, and Windscribe are publicly confirming willingness to engage with UK government on child safety

- Regulatory Pressure: The UK's Online Safety Bill has forced VPN companies to address child protection concerns more directly than ever before

- Strategic Shift: Rather than pure resistance, industry is adopting a collaborative approach to shape policy instead of simply reacting to it

- Global Implications: UK government's online safety framework is likely to influence regulatory approaches across Europe and beyond

- Bottom Line: Expect VPN companies to implement more transparency measures and child safety features as part of regulatory compromise

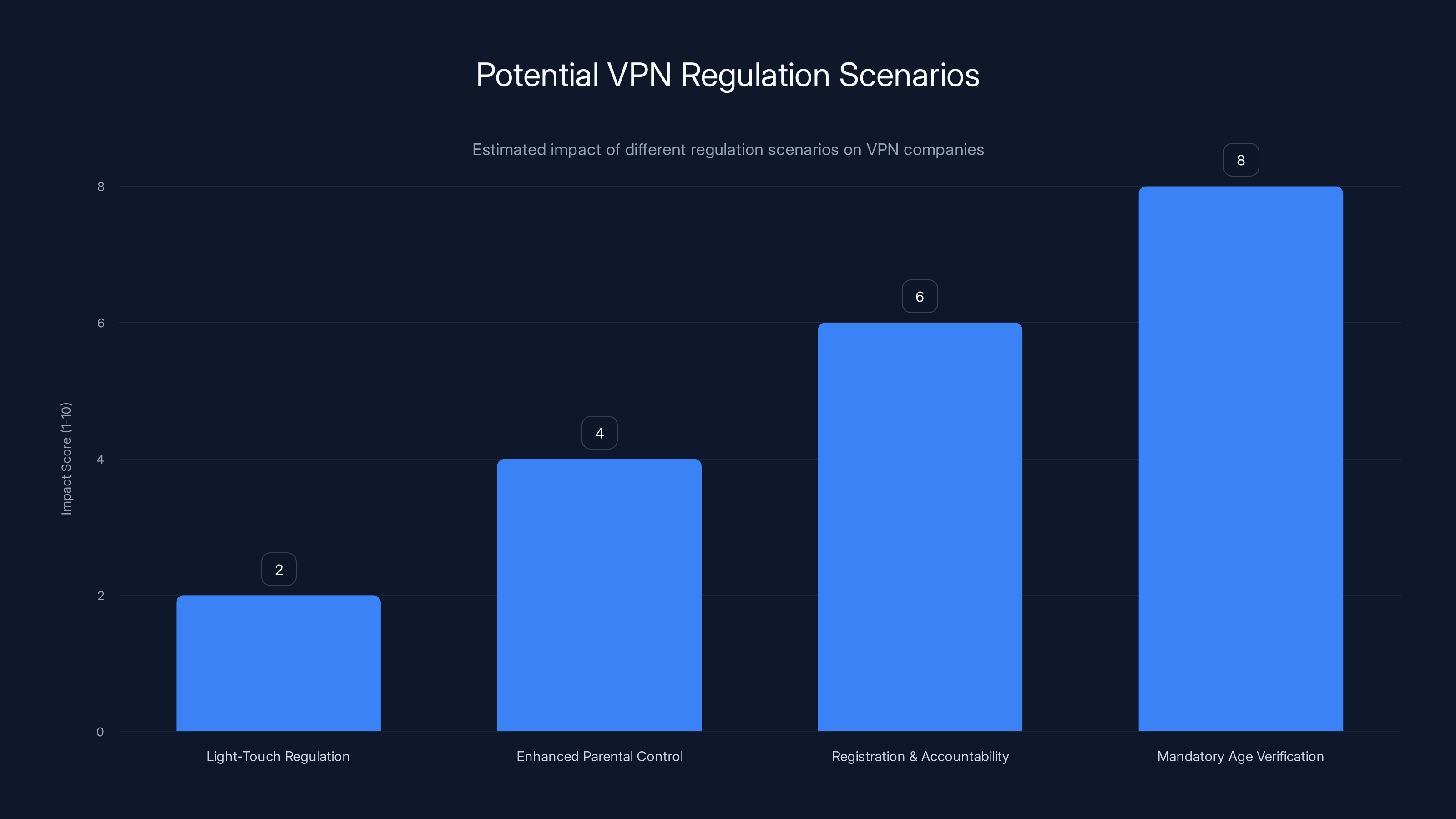

Estimated data: Light-touch regulation has minimal impact, while mandatory age verification poses significant challenges for VPN companies.

The Online Safety Context: Why Kids and VPNs Are Now Linked

Before diving into the VPN industry's response, you need to understand what forced this conversation in the first place. The UK government didn't wake up one morning obsessed with VPNs. Instead, child safety concerns created a perfect storm that swept VPN providers directly into the legislative spotlight.

The Online Safety Bill represents one of the most comprehensive attempts any government has made to regulate what children see online. The core premise is straightforward: internet companies have responsibility for harmful content on their platforms. But here's where it gets complicated with VPNs. These tools mask user location and activity, which makes them simultaneously a privacy champion and a potential facilitator of harmful behavior.

Parents, educators, and child protection advocates have raised legitimate concerns about VPN use among minors. When a 14-year-old can hide their browsing from parents using a VPN, suddenly there's less visibility into whether they're accessing age-inappropriate content. This created political pressure on lawmakers to address the issue.

The UK government didn't necessarily want to ban VPNs. That would be politically difficult and practically impossible. Instead, they started asking: what responsibilities do VPN companies have? Should they implement age verification? Should they cooperate with law enforcement when children are at risk? Should they limit access for users below a certain age?

These aren't rhetorical questions. They're the foundation of what the government is now asking during the consultation process. And VPN companies suddenly realized they needed to participate in answering them, rather than sitting on the sidelines hoping the conversation went away.

The regulatory environment shifted dramatically once child safety became the anchor of the policy discussion. When the issue is "privacy for adults," VPN companies have strong arguments about freedom and personal data protection. But when the issue becomes "protecting children from harmful content," the moral and political weight shifts. Suddenly, VPN companies face a choice: engage constructively or appear complicit in harm.

Why VPN Companies Are Speaking Up Now

Let's be direct about this. VPN companies didn't suddenly develop a passion for regulatory compliance out of pure altruism. They're speaking up because the alternative is worse. Getting dragged through endless government inquiries, facing potential bans, or ending up on the wrong side of public opinion isn't a winning strategy.

But there's more nuance here. The industry recognizes something critical: regulation is coming whether they cooperate or not. The only variable is whether they help shape it. By stepping forward now and engaging in what they're calling "meaningful dialogue," these companies are trying to influence what that regulation actually looks like.

Consider the practical reality. If VPN companies simply ignored the government, lawmakers would probably write restrictions anyway. Those restrictions might be clumsy, overly broad, or technically impossible to implement properly. By participating now, VPN companies can educate regulators about what's actually feasible from a technical standpoint and what the real-world implications of different policy options would be.

There's also a business case here, though VPN companies won't say it directly. Right now, VPN adoption is growing. More people use VPNs for legitimate reasons: protecting data on public Wi-Fi, privacy from advertisers, accessing content while traveling. If regulation is perceived as hostile to VPNs generally, adoption might slow. But if regulation appears reasonable and fair, it might actually increase consumer confidence in VPNs.

Nord VPN, Surfshark, Express VPN, and Windscribe confirming their willingness to engage is a calculated move. It positions them as reasonable players willing to work within the system. That's good PR. It also gives them a seat at the table when specific rules get written. And frankly, that's worth more than any amount of Twitter activism.

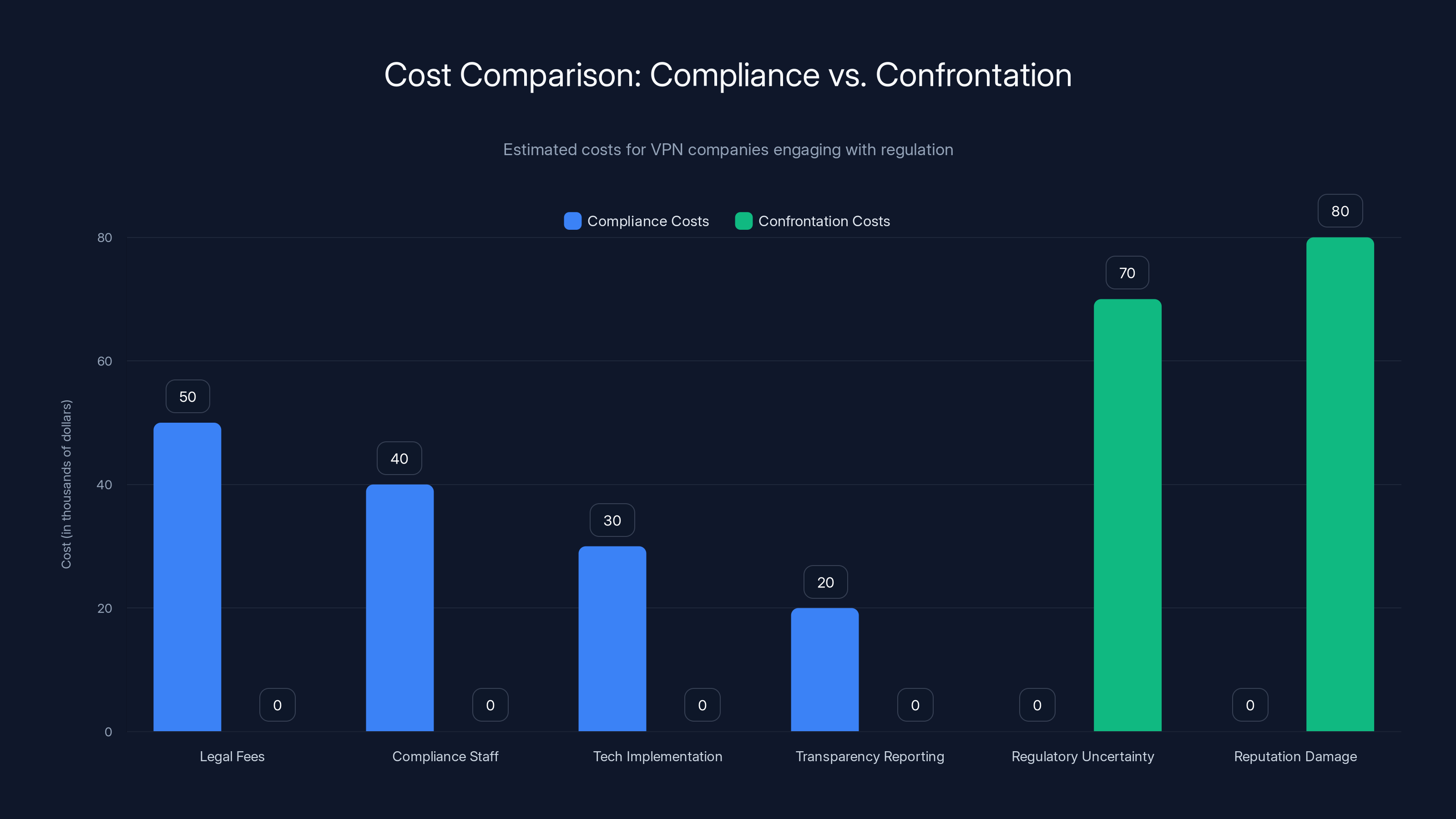

Estimated data shows that compliance costs (legal fees, staff, tech) are lower and more predictable than confrontation costs (uncertainty, reputation damage).

Nord VPN: Positioning as the Responsible Player

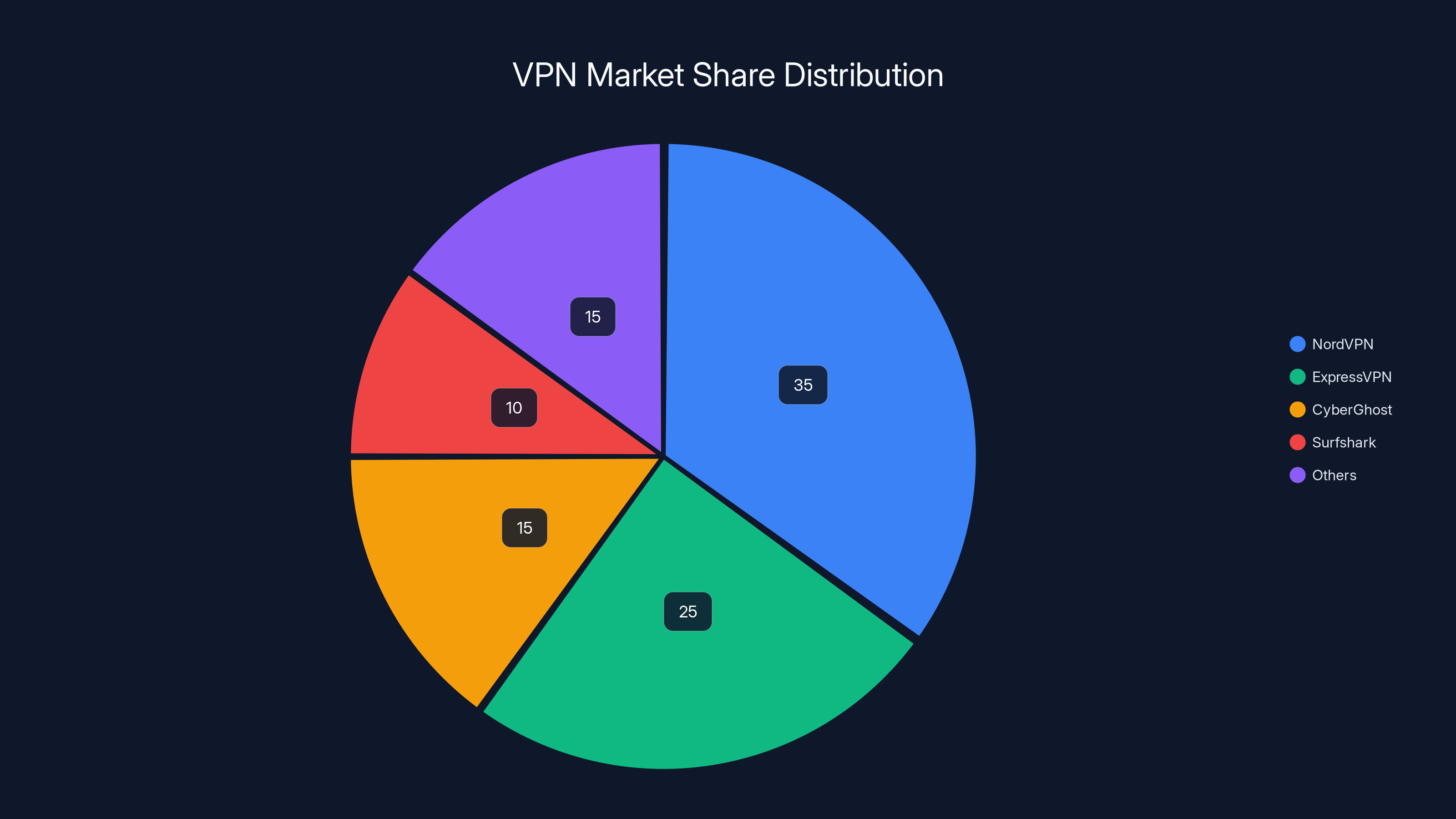

Nord VPN, the largest VPN provider by market share, has been particularly vocal about its willingness to engage. The company's public position is that they want to work with governments to develop balanced approaches to online safety that don't undermine privacy.

What's interesting about Nord VPN's approach is the emphasis on education. Their representatives have consistently pointed out that VPNs themselves are neutral tools. A VPN doesn't cause harm; how it's used determines whether it's beneficial or harmful. By providing this context, Nord VPN is trying to reframe the conversation from "VPNs are dangerous" to "we need proportionate regulation that accounts for legitimate uses."

Nord VPN has also emphasized their existing safety measures. They've implemented features like threat protection (which blocks malware), and they claim to have robust policies against payment fraud and illegal activities. By highlighting these existing controls, they're showing regulators that they're already doing something about safety, which makes a case for proportionate rather than draconian regulation.

The company's willingness to engage appears genuine at the operational level too. They've stated they're willing to discuss age verification mechanisms, though they haven't committed to implementing blanket age restrictions. They've also indicated openness to working with child safety organizations and researchers to better understand the real risks.

Nord VPN's strategy makes sense from a market perspective. They're already the biggest player, so cooperating with government actually benefits them by potentially raising barriers to entry for smaller competitors. If government regulation makes it harder for fly-by-night VPN companies to operate, the established players benefit.

But there's a risk in Nord VPN's approach too. If they appear too eager to cooperate with government, they might alienate the privacy-conscious users who chose them specifically because they viewed VPNs as tools to protect against government surveillance. Striking the right balance between being reasonable and staying true to privacy advocacy is a tightrope.

Surfshark's Collaborative Stance

Surfshark, the second-largest player by some estimates, has similarly confirmed willingness to engage. Their position mirrors Nord VPN's in many ways but with some distinct emphasis areas. Surfshark has been particularly vocal about education and transparency.

What differentiates Surfshark's approach is their focus on the distinction between child safety and adult privacy. They've repeatedly stated that robust protections for children don't require dismantling privacy for adults. This is important because it reframes the debate. Instead of asking "should we regulate VPNs?" the question becomes "how do we protect children without destroying privacy?"

Surfshark has also been explicit about where they draw lines. They've said they would not implement forced age verification systems because, they argue, these systems themselves create privacy problems. Instead, they've suggested alternative approaches like educational campaigns, parental controls integration, and cooperation with internet safety organizations.

The company's willingness to engage appears to include actual operational willingness too. Surfshark has stated they're open to providing data to authorities when there's proper legal process. Most VPN companies make this claim, but Surfshark has been relatively transparent about how they'd handle such requests, which builds credibility.

One interesting aspect of Surfshark's approach is their focus on alternatives to VPNs for child safety. They've suggested that if the real goal is protecting children online, regulation should focus on stronger parental controls built into devices and platforms, better education for parents and kids about online risks, and holding content platforms responsible for harmful material. VPNs, in their view, are just one tool and shouldn't be the focus of child safety policy.

This reframing is clever because it positions Surfshark as thoughtful about child safety while deflecting away from VPN-specific regulation. It's also actually sound policy thinking. Most child safety experts would agree that the real problem isn't VPNs; it's a combination of insufficient parental awareness, weak platform accountability, and inadequate education.

Express VPN's Measured Engagement

Express VPN takes a slightly more cautious approach compared to Nord VPN and Surfshark, though they've still confirmed willingness to engage. The company is owned by Kape Technologies, a firm with a more complex corporate structure, which might influence their regulatory stance.

Express VPN's messaging emphasizes the importance of any dialogue being evidence-based. They've called for the government to consult with security researchers, child safety experts, and technologists—not just politicians and advocacy groups. This is a subtle but important positioning. It suggests that if the government does engage with VPN companies, they should also consult with people who can verify claims about how VPNs actually work and what the real risks actually are.

The company has also been explicit about the limits of what VPNs can reasonably do. They've pointed out that age verification on VPNs would be problematic because users could easily find alternative VPNs from outside the UK's jurisdiction. This makes a technical argument for why certain regulations might be ineffective, which is the kind of practical input that helps governments write smarter rules.

Express VPN's approach suggests they're trying to be the "smart" player in the conversation. Rather than just saying "we cooperate," they're saying "we cooperate while bringing technical expertise that will make your policy better." This positions them as a valuable participant in dialogue.

One notable aspect of Express VPN's stance is their emphasis on threat actors. They've noted that bad actors—people trying to exploit children or commit crimes—won't use mainstream VPNs like Express VPN. They'll find other tools, maybe even build their own. By pointing this out, Express VPN is making a case that regulating legitimate VPN providers won't actually stop bad behavior; it might just inconvenience people using VPNs for legitimate purposes.

Express VPN's measured engagement might also reflect regulatory concerns. The company has faced scrutiny in various countries for its privacy claims and operational practices. Being too vocal about regulations could draw additional attention. Being reasonably cooperative but technically careful is probably their safest approach.

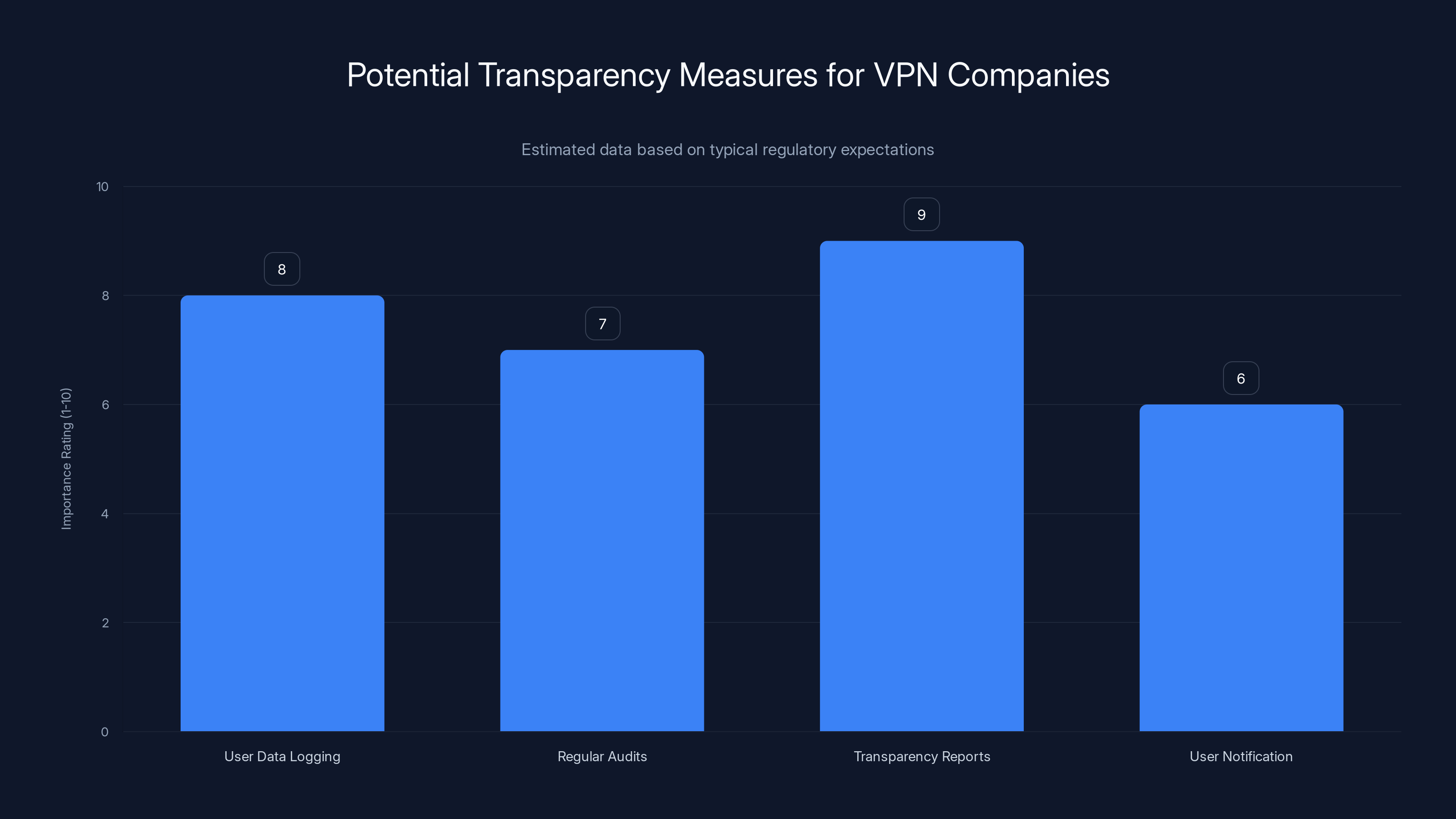

Estimated data suggests that transparency reports and user data logging are seen as the most important measures for VPN companies to implement under potential regulations.

Windscribe's Transparent Communication

Windscribe, the smallest of the major players willing to engage, brings a different perspective. The company is Canadian and focuses heavily on transparency and user education. Their willingness to engage with the UK government might surprise some, given that they're based outside UK jurisdiction.

Windscribe's approach emphasizes full transparency about what VPNs can and cannot do. They've been public about their logging practices, their security implementation, and their data retention policies. This transparency-first approach positions them well for government engagement because they're not hiding anything.

The company has also been vocal about the importance of protecting open internet access. They've made arguments that VPNs serve important functions beyond privacy—they protect journalists, activists, and people in countries with censorship. This adds moral weight to arguments about not over-regulating VPNs.

Windscribe's engagement with the UK government also signals something about the industry's broader thinking. Even smaller players feel compelled to participate in these conversations. This suggests the regulatory pressure is significant enough that every player recognizes the need to participate.

One interesting aspect of Windscribe's position is their focus on technical education. They've written extensively about how VPN encryption works, what data is encrypted and what isn't, and the real technical limitations of VPNs. By educating the public and regulators about actual VPN mechanics, Windscribe is building the foundation for more informed policy.

Windscribe's Canadian ownership actually gives them interesting credibility. They operate in a jurisdiction with strong privacy laws and specific government relationships. They're not operating in the shadows; they're a legitimate company with legal oversight. This actually helps their argument that legitimate VPN companies can be responsible actors.

What "Meaningful Dialogue" Actually Means in Practice

All these companies keep using the phrase "meaningful dialogue." But what does that actually mean? It's important to understand what each side probably wants from this conversation and where the actual negotiation might happen.

For the government, meaningful dialogue probably means getting answers to specific questions. Can you implement age verification? What would you need to do it? How would you handle requests from law enforcement? What existing safety measures do you have? Are you willing to work with child safety organizations? What would it take for you to implement certain restrictions?

The government also wants to understand technical feasibility. If they propose a regulation, they want to know whether it's actually implementable or whether it's technically impossible. Getting this technical input during dialogue prevents them from writing rules that can't be enforced.

For VPN companies, meaningful dialogue means having a voice in policy development rather than having policy imposed on them. It means educating regulators about real-world technical limitations. It means building relationships with government officials so future regulations account for legitimate use cases. And frankly, it means delaying or preventing regulations they view as harmful.

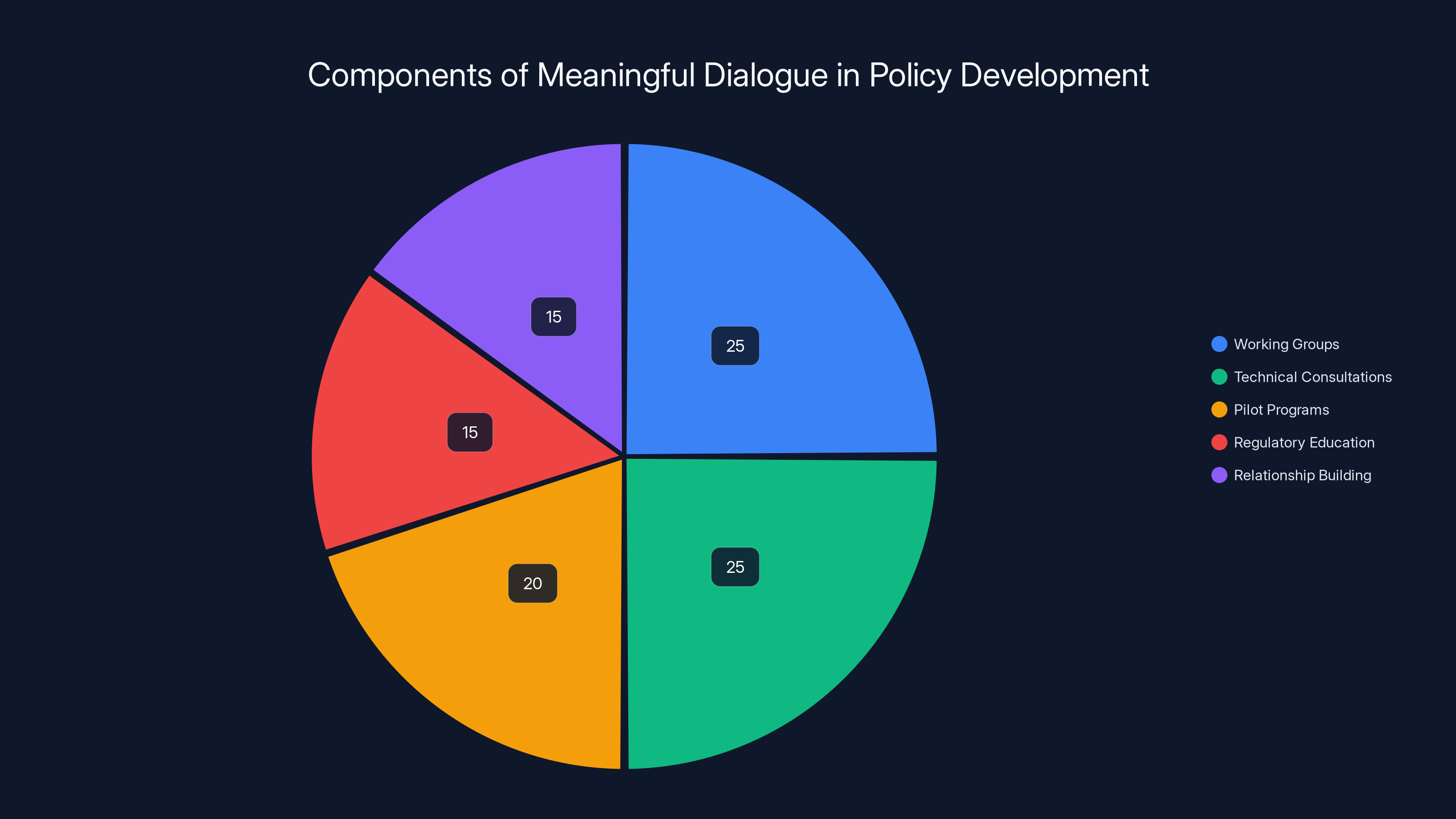

Practically speaking, meaningful dialogue probably involves some combination of the following:

-

Working groups: Government might establish formal working groups with VPN industry representatives, child safety experts, researchers, and advocacy organizations. These groups would develop recommendations for balanced policy.

-

Technical consultations: VPN companies would provide input on what's technically feasible, what would be costly, and what workarounds might exist for any proposed regulation.

-

Pilot programs: For certain safety measures, there might be agreement to test approaches on a limited basis before broader implementation.

-

Information sharing: VPN companies might agree to share specific data about emerging threats, misuse patterns, or how their tools are being exploited, without compromising user privacy.

-

Industry standards: Rather than government mandates, there might be agreement to establish industry best practices that all major VPN providers would follow.

-

Age-gating and parental controls: Possible agreement on how VPN companies could incorporate better parental controls or age-appropriate features without implementing problematic identity verification.

The reality is that dialogue will likely yield some compromises. VPN companies probably won't get everything they want. The government will probably push for more accountability measures than the industry prefers. But the goal is avoiding extreme outcomes on either side.

Extreme outcomes might include: (1) Complete VPN bans, which would be technically difficult and politically unpopular; (2) Mandatory user surveillance, which would defeat the purpose of VPNs; (3) Forced cooperation with law enforcement that violates privacy principles; or (4) Age restrictions that prevent legitimate adult use.

Realistic compromise outcomes might include: (1) VPN companies maintaining registries or providing some form of light accountability; (2) Enhanced parental control features built into VPN applications; (3) Cooperation with law enforcement in serious criminal investigations involving minors; (4) Transparency about logging practices; (5) Industry adherence to certain safety standards around malware detection and fraud prevention.

The Child Safety Challenge: Real Risks vs. Political Theater

Here's where this gets genuinely complex. There are real child safety risks that VPNs can facilitate. Kids can use VPNs to hide inappropriate activity from parents. Predators can use VPNs to hide their locations. But there's also political theater happening, where the issue becomes exaggerated beyond the actual risk.

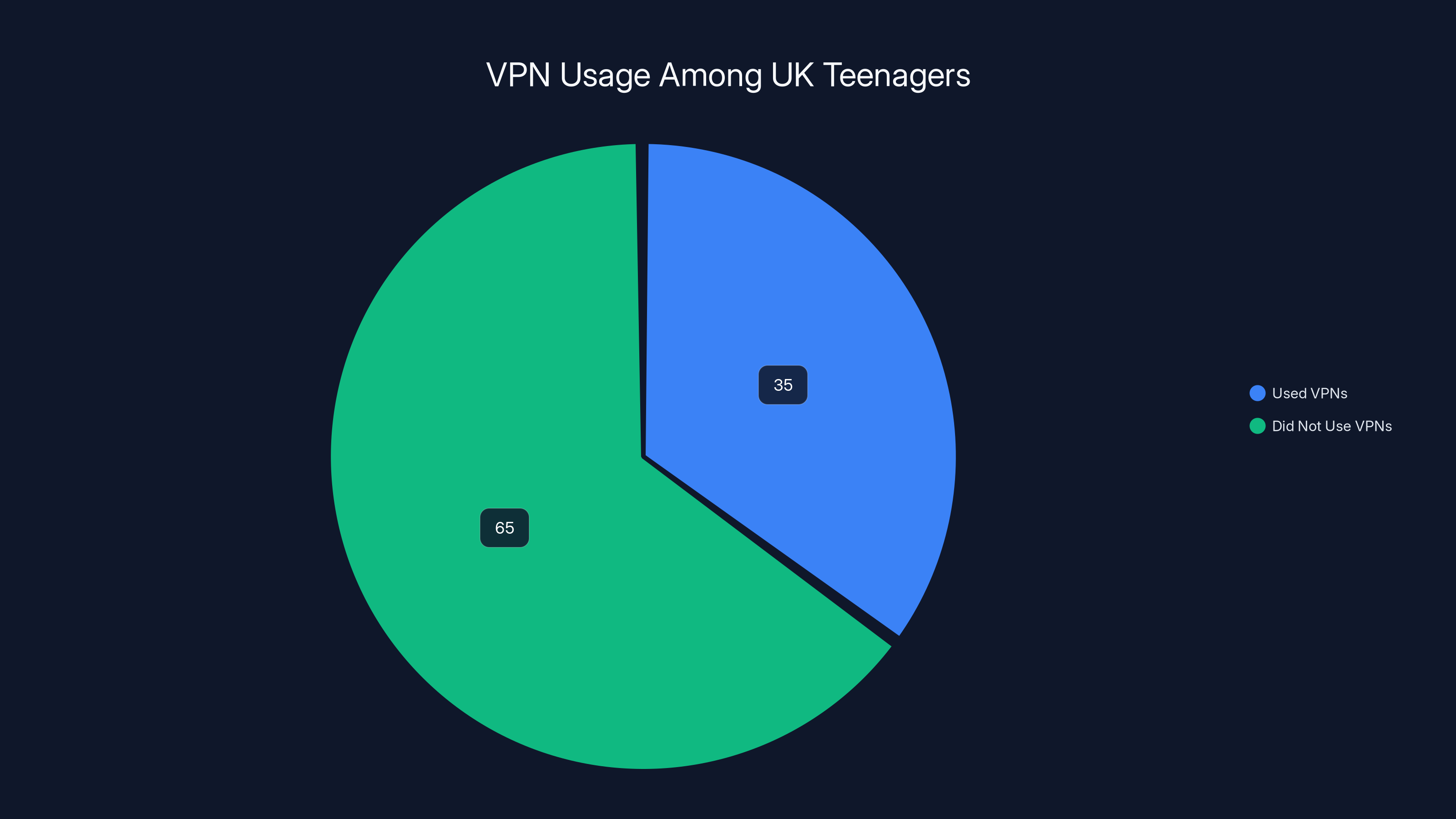

The actual evidence on VPN misuse by children is limited. We know some percentage of UK teenagers use VPNs, but we don't have clear data on what they're doing with them or how frequently harmful outcomes result. Are kids using VPNs to watch age-inappropriate videos? Probably some do. Are they using VPNs to interact with predators? Possibly, but predators would likely find other tools if VPNs weren't available.

The challenge for VPN companies in dialogue is that they need to acknowledge real risks without conceding to regulation that treats the risk as larger than evidence suggests. This requires careful communication about statistics, about what's actually knowable, and about what other factors matter more.

Some child safety organizations actually agree with VPN companies on this point. They've noted that restricting VPNs probably won't meaningfully improve child safety and might create a false sense of security among parents. Better education, stronger platform accountability, and improved parental tools would be more effective.

But political pressure is real. Parents want to feel like government is doing something about child safety. Politicians need to show action. This creates pressure to regulate something, and VPNs became a visible target because they're easier to understand and regulate than the complex issues of platform algorithm optimization or content moderation failures.

The dialogue between VPN companies and the government is, at some level, about finding a middle path. Can regulators take action on child safety that addresses legitimate concerns without imposing technically impossible or privacy-destroying requirements? Can VPN companies acknowledge real risks and commit to reasonable measures without abandoning their core business model?

Approximately 35% of UK teenagers have used a VPN or proxy service to bypass restrictions, highlighting a significant concern for online safety.

The Broader Regulatory Picture: What Happens in the UK Matters Globally

One reason VPN companies are taking the UK government engagement seriously is that policy set here often becomes template for other jurisdictions. The UK pioneered the idea of comprehensive online safety regulation with the Online Safety Bill. Other countries are watching. The EU is developing its own framework. Australia, Canada, and other jurisdictions are considering regulation.

How the UK handles VPN regulation will influence all of this. If UK regulators find a sensible middle ground that doesn't require VPN bans or mandatory surveillance, that becomes the template. If they overreach and create impossible requirements, other countries might do the same or might learn from it and avoid that approach.

VPN companies engaging with the UK government now is partly about shaping a template that works. They'd much rather influence the original policy than fight against multiple jurisdictions with conflicting requirements later.

There's also a business reality. Major VPN companies operate globally. Compliance requirements vary wildly by country. Some countries (like China) effectively ban VPNs. Some countries (like the US) have specific regulations VPNs must follow. The UK is now in the middle—not hostile to VPNs but requiring some accountability.

Navigating this landscape is expensive. If the UK creates a reasonable framework that becomes the template, it's actually beneficial to major players who can afford compliance. It's harder on smaller players and new entrants, which limits competition in the VPN space.

This has an interesting dynamic: larger VPN companies might actually want some regulation, as long as it's not onerous, because regulation raises barriers to entry and protects their market position. Smaller competitors have less ability to comply with complex requirements.

What's Actually on the Table: Potential Regulation Scenarios

Based on public statements and regulatory patterns in similar jurisdictions, several scenarios for VPN regulation seem plausible. Understanding these helps clarify what "meaningful dialogue" might actually produce.

Scenario 1: Light-Touch Regulation VPN companies maintain existing practices with minor enhancements to transparency reporting. Maybe they commit to publishing information about data requests they receive, cooperation with law enforcement, and abuse reports. This is the outcome VPN companies would prefer. It's also what would likely result if the industry effectively educates regulators about technical realities.

Scenario 2: Enhanced Parental Control Requirements VPN companies are required to implement optional parental control features in their applications. This might include activity logging options (that parents can enable), content filtering, or time-restriction features. Companies that already offer family plans with these features would be minimally affected. This is a reasonable compromise that addresses child safety without compromising privacy.

Scenario 3: Registration and Accountability Framework VPN companies operating in the UK (or offering services to UK users) must register with authorities, maintain certain information about operators, and have systems for responding to abuse reports. This is more invasive than light-touch regulation but doesn't fundamentally change how VPNs work. It's similar to requirements in other regulated industries.

Scenario 4: Mandatory Age Verification VPN companies are required to verify user age before providing access, or at least require confirmation that users are adults. This is the kind of requirement many VPN companies have indicated would be problematic. It creates privacy issues (how do you verify age without collecting identifying information?) and technical issues (it's easy to bypass or work around).

Scenario 5: Restricted Access for Minors VPN companies are required to implement restrictions preventing access by users identified as minors. This would require age verification plus active restrictions. It would be technically difficult, legally questionable, and possibly counterproductive. This is probably the least likely outcome given that VPN companies and even some regulators have indicated skepticism.

The dialogue happening now is probably about which scenario emerges. Light-touch regulation is what VPN companies want. Restricted access is what some child safety advocates might want. The actual outcome is probably somewhere in the middle—probably Scenario 2 (enhanced parental controls) or Scenario 3 (registration and accountability), with maybe some elements of Scenario 1 (transparency reporting).

The success of dialogue depends partly on whether VPN companies can convince regulators that Scenarios 4 and 5 are unworkable, and partly on whether they can propose alternatives (like Scenario 2) that actually address child safety concerns.

Transparency Reports: A Model for Compromise

One interesting aspect of the VPN industry's engagement is the increasing willingness to publish transparency reports. Several major providers now publish reports showing how many government data requests they receive and what percentage they comply with. This model might become central to regulatory compromise.

Transparency reports serve several functions. For users, they demonstrate that the company is being held accountable. For governments, they show that the company has systems for responding to legal requests. For regulators, they provide data about how the company operates and whether it's respecting the law.

VPN companies benefit because transparency reports simultaneously show they're law-abiding while highlighting their limited ability to comply with requests. If a report shows they received 1,000 government requests but could only comply with 50 because they don't maintain the data requested, that proves they're not spying on users.

Expanded transparency reporting could become the centerpiece of compromise regulation. Instead of requiring VPN companies to implement restrictions or collect data they don't currently collect, regulators could require them to publish regular reports about their systems, their compliance with legal requests, and their approach to abuse. This gives regulators visibility while maintaining user privacy.

This model also works internationally. Companies can publish one report that complies with requirements in multiple jurisdictions rather than maintaining separate systems for each country. This reduces compliance costs and complexity.

NordVPN holds the largest market share at an estimated 35%, positioning itself as a leader in the VPN industry. Estimated data.

The Role of Child Safety Organizations in the Dialogue

While most coverage focuses on VPN companies and government, child safety organizations are also part of this conversation. Groups like the Internet Watch Foundation, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and various UK-based child protection agencies have perspectives that matter.

Interestingly, these organizations don't all align against VPNs. Some recognize that VPN regulation won't meaningfully improve child safety and prefer to focus on platform accountability and education. Others are concerned about VPN misuse and want stronger restrictions.

The dialogue benefits from having diverse perspectives. Child safety experts can provide evidence about real risks. They can help distinguish between theoretical problems and actual documented harms. They can also help design regulations that actually address the problems they care about rather than just addressing visible tools.

Some child safety organizations have also noted that VPN companies have been responsive partners. Unlike social media platforms that resist any restrictions, VPN companies have been willing to discuss safety measures. This creates incentive for constructive engagement.

Data Privacy Concerns: The Other Side of the Equation

One complication in this dialogue is that while VPN companies want to protect privacy, regulators increasingly want access to data for law enforcement and child protection. This tension is inherent and probably can't be completely resolved.

VPN companies fundamentally can't provide what they don't have. If a company doesn't log which user visited which website (which is good for privacy), they literally can't provide that information to authorities even if they wanted to. This technical reality is important context for regulation.

But some VPN companies do maintain certain information: payment information tied to accounts, IP addresses used to access their service, time of service use. This information could potentially be provided to authorities in serious cases. The dialogue is probably partly about defining what information must be retained, for how long, and under what legal process it can be accessed.

The risk for VPN companies is that regulators require them to maintain more data than they currently do, which compromises user privacy. The risk for regulators is that VPN companies maintain their position of minimal data retention, which limits law enforcement options in serious crimes.

Finding a compromise probably involves defining specific scenarios where data would be retained and shared (like investigations involving child exploitation) while maintaining minimal logging in other contexts. This is technically possible and probably represents the kind of outcome dialogue might achieve.

International Precedents: What Other Countries Have Done

The UK isn't inventing this conversation from scratch. Other countries have already wrestled with VPN regulation. Looking at precedents helps clarify what might happen.

The United States has no comprehensive VPN regulation, though some states have begun requiring transparency from VPN providers. The regulatory approach has been relatively light-touch, with law enforcement able to work with VPN companies on a case-by-case basis.

Europe is more regulated. The EU's GDPR impacts how VPN companies handle data. Some EU countries (like Russia) have effectively restricted VPN use. Others (like Germany and France) have focused more on transparency and accountability than outright restriction.

Australia has implemented mandatory data retention laws that affect VPN companies. Companies operating there must retain certain data and make it available to authorities. This is generally seen as having pushed a more privacy-hostile model onto the VPN industry.

The UK's dialogue approach is different from both the US (which relies on informal cooperation) and Australia (which mandated data retention). It's closer to the EU's model of working toward balanced regulation that protects both privacy and law enforcement interests.

Understanding these precedents helps both VPN companies and regulators avoid mistakes. The Australian model is generally seen as having gone too far. The US model is seen as insufficient by those concerned about law enforcement access. The EU model is seen as reasonable by many stakeholders.

The UK seems positioned to learn from these precedents and avoid extremes. That might explain why VPN companies are willing to engage. They probably believe the UK regulatory approach will be more balanced than Australia's but more effective than the US approach.

Estimated data shows that working groups and technical consultations are key components, each making up 25% of meaningful dialogue efforts, followed by pilot programs, regulatory education, and relationship building.

The Business Case: Why Compliance Costs Less Than Confrontation

Underlying all this engagement is a basic business calculation. For major VPN companies, complying with reasonable regulation costs less than fighting regulation, dealing with legal uncertainty, or enduring negative regulatory attention.

Compliance costs include legal fees, compliance staff, technology implementation, and transparency reporting. These are real costs, but they're knowable and manageable for large companies. Regulatory uncertainty, potential restrictions that limit business, and damage to reputation are harder to quantify but potentially much costlier.

From a business perspective, engaging constructively with government is rational. It shows good faith, builds relationships, and gives companies influence over outcomes. This is standard practice in regulated industries like finance, pharmaceuticals, and telecommunications.

The VPN industry is gradually normalizing this relationship with government. Early VPN providers operated almost like underground movements, skeptical of all government interaction. Modern VPN companies operate more like legitimate businesses that work with regulators.

This normalization probably benefits both sides. VPN companies get more predictable regulatory environments. Governments get better information for policy-making and companies that take safety seriously rather than companies operating purely in the shadows.

The willingness of major VPN companies to engage also says something about industry consolidation. The largest players can afford compliance. Smaller startups can't. This probably means the VPN market becomes more concentrated over time, with a few major players dominating.

Challenges and Potential Breakdowns in Dialogue

While the initial willingness to engage is encouraging, this dialogue faces real challenges. Understanding them helps predict what might actually happen.

Challenge 1: Fundamental Disagreement on Privacy Governments want more data access. VPN companies want to provide less. This is inherently contradictory. Compromise is possible but finding the sweet spot is difficult.

Challenge 2: Political Pressure If child safety concerns escalate or incidents occur, political pressure for stricter regulation might override dialogue outcomes. Companies need to feel confident that agreements will be honored.

Challenge 3: Technology Evolution New technologies and new ways of using existing tools emerge constantly. Regulation based on current understanding might become obsolete quickly.

Challenge 4: International Conflict If the UK moves toward regulation and other countries move toward restriction or prohibition, VPN companies might be caught in conflicting requirements.

Challenge 5: Implementation Verification Even if companies agree to certain measures, how does government verify they're actually implementing them? This requires some level of inspection or oversight.

Based on regulatory patterns in similar sectors, some of these challenges are solvable through dialogue. Others will probably produce ongoing tension. The outcome will likely involve compromise where both sides don't get everything they want but both can live with the result.

Looking Forward: What to Expect

Based on the current dynamics, here's what seems likely to happen:

In the short term (next 6-12 months), expect continued dialogue and working group meetings. VPN companies will provide technical input. Government will clarify what it's concerned about. Child safety organizations will contribute research. This period will probably produce some form of framework or recommendations.

In the medium term (1-2 years), expect formal regulation in some form. It probably won't be as restrictive as some child advocates want, nor as permissive as VPN companies prefer. It will likely include transparency requirements, accountability mechanisms, and possibly enhanced parental control requirements.

In the long term (2+ years), expect regulatory frameworks to stabilize and become normal practice. VPN companies will have adapted. Users will continue using VPNs. Government will have data about VPN use and can adjust regulation based on what they learn.

Globally, expect the UK's approach to influence policy in other jurisdictions. The EU might adopt similar frameworks. Other English-speaking countries might follow. This creates a more harmonized regulatory environment for VPN companies operating internationally.

The VPN companies' willingness to engage suggests they believe this outcome is acceptable. If they thought regulations would be unreasonably restrictive, they'd likely fight harder rather than cooperate. The fact that they're engaging constructively suggests they believe compromise is possible.

For Users: What This Means for You

If you use a VPN, what should you understand about this regulatory conversation?

First, VPNs aren't going away. Even if the UK implements restrictions, they'll be relatively modest restrictions, not bans. Major VPN services will continue operating.

Second, your VPN provider's willingness to engage with regulators is actually good news. Companies that work with government tend to be more stable, better funded, and more trustworthy than companies operating in complete secrecy.

Third, the dialogue is probably improving regulations rather than making them worse. If VPN companies weren't at the table, government might write rules that are technically impossible or privacy-destroying. Having companies provide technical input probably results in better rules.

Fourth, expect minor changes in how VPN services operate. These will likely focus on transparency (publishing more information about how they operate) rather than functionality (restricting what users can do).

Fifth, if you're using a VPN for legitimate reasons (privacy, security, accessing services while traveling), nothing in this regulatory discussion should concern you. The dialogue is about accountability for misuse, not restriction of legitimate use.

FAQ

What exactly is the UK's Online Safety Bill and how does it affect VPNs?

The Online Safety Bill is comprehensive legislation that gives Ofcom authority to regulate online services and hold companies accountable for harmful content. It affects platforms, search engines, and ancillary tools like VPNs. The Bill doesn't explicitly regulate VPNs, but the government's online safety agenda brings VPNs into the conversation because they can mask user identity, which complicates child protection efforts. VPN companies are engaging because the regulatory framework being created could eventually include specific requirements for them.

Why are major VPN companies willing to engage with government instead of fighting regulation?

Major VPN companies recognize that regulation is likely regardless of their position, so engaging constructively gives them influence over what that regulation looks like. Fighting government is expensive and ultimately unsuccessful. By participating in dialogue, companies can educate regulators about technical realities, propose reasonable alternatives to problematic restrictions, and build relationships that lead to balanced policy. From a business perspective, compliance with reasonable regulation costs less than legal battles and regulatory uncertainty.

What are the main child safety concerns that governments have about VPNs?

Governments are concerned that VPNs can be used by minors to hide online activity from parents, potentially facilitating access to harmful content, interaction with predators, or other risky behavior. However, there's limited evidence about how frequently VPN misuse actually leads to harm compared to other online risks. Child safety organizations have noted that restricting VPNs probably won't meaningfully improve child safety and that education, communication, and device-level controls are more effective approaches.

What transparency measures might VPN companies be asked to implement?

Based on regulatory patterns, likely transparency measures include publishing reports about government data requests and responses, providing information about the company's logging practices and data retention policies, describing procedures for handling abuse reports, and possibly submitting to audits of security practices. Several major VPN companies already publish transparency reports, which might become an industry standard. These measures give regulators visibility into operations while maintaining user privacy.

Could the UK government actually ban VPNs like some other countries have attempted?

VPN bans are technically difficult to implement and politically unpopular because VPNs have legitimate uses including privacy protection, security on public Wi-Fi, and accessing services while traveling. The UK government has shown no indication of pursuing an outright ban. The dialogue happening now suggests the government is looking for balanced regulation that addresses legitimate concerns without eliminating VPN services. Russia's attempt to ban VPNs demonstrated that technical blocking is difficult and users find workarounds.

How might UK regulation of VPNs affect services available to users?

Regulation will likely cause relatively minor changes focused on transparency and accountability rather than functionality restrictions. VPN companies might need to implement enhanced parental control features, publish more information about their operations, or maintain certain data for law enforcement cooperation in serious cases. For typical users, these changes would be invisible. VPNs would continue offering privacy protection, and legitimate uses would continue to work.

What's the difference between a VPN company saying they'll cooperate with law enforcement and actual user privacy concerns?

VPN companies can cooperate with law enforcement in limited ways without compromising user privacy. If a company doesn't maintain detailed logs of user activity (which is good for privacy), they literally can't provide activity logs to authorities. But they can provide payment information, account creation information, and basic metadata if presented with proper legal process. The dialogue is probably about defining what information must be retained and under what circumstances it can be shared, rather than requiring companies to spy on users.

How does UK VPN regulation compare to approaches in other countries?

The UK's approach of dialogue and balanced regulation is more moderate than Australia's mandatory data retention laws (which are considered harsh) and more structured than the US approach (which relies on informal cooperation). The UK is closer to the EU model of working toward balanced regulation protecting both privacy and law enforcement interests. This suggests regulations will be reasonable compared to global extremes—not as restrictive as some countries, but more structured than others.

Will this regulatory conversation affect which VPN providers are available to UK users?

Likely yes, but probably through market consolidation rather than government restriction. Regulation raises compliance costs, which large established companies can manage but new entrants and small providers struggle with. This probably means the UK market becomes dominated by a few major established providers rather than having dozens of options. This could improve quality and trustworthiness but might reduce choice.

What should parents do if they're concerned about their children using VPNs to bypass restrictions?

Parental control at the device or router level is more effective than trying to restrict specific tools like VPNs. Modern parental control tools can block VPN traffic if parents want, but more effective approaches focus on communication and education. Understanding why children want privacy (which is normal development), having open conversations about online safety, and using device-level tools to monitor activity are more effective strategies than trying to ban specific technologies.

How might transparency reports from VPN companies actually protect users?

Transparency reports demonstrate that companies are being held accountable and that they're not secretly spying on users. If a report shows a company received 1,000 government data requests but could only comply with 50 because they don't maintain the requested data, that proves they're not logging user activity extensively. For regulators, reports provide data about whether companies are respecting law and whether abuse is occurring. For users, reports provide evidence that the company takes privacy seriously and is subject to oversight.

Conclusion: A Maturing Industry Meets Regulatory Reality

The willingness of major VPN companies to engage in meaningful dialogue with the UK government represents something important. It's not just about child safety policy or VPN regulation. It's about the VPN industry maturing from a fringe technology operated by privacy advocates into a mainstream service offered by serious companies that understand they operate within legal frameworks.

This shift is probably inevitable. As VPN adoption grows and legitimate uses become mainstream, these tools will eventually be regulated like other communications services. The only variable is whether that regulation is balanced and reasonable or whether it's extreme and counterproductive.

The companies willing to engage—Nord VPN, Surfshark, Express VPN, and Windscribe—are betting that dialogue leads to reasonable outcomes. They're probably right. Government officials engaging with these companies are learning about technical realities that will inform better policy. Everyone benefits if the result is regulation that actually improves child safety without destroying privacy or making it impossible to run a legitimate VPN service.

There are still potential breakdowns and challenges ahead. Political pressure, technology evolution, and fundamental disagreements about privacy could complicate things. But the fact that dialogue is happening at all suggests both sides recognize that some form of working relationship is possible.

For VPN users, this regulatory conversation is probably good news. Companies willing to work with government tend to be more stable and trustworthy than companies operating in complete shadows. Regulation that emerges from thoughtful dialogue is probably more balanced than regulation written without industry input. And the fact that major services are still operating and engaging suggests they believe they can operate profitably under whatever regulatory framework emerges.

The real test comes next. Will the actual dialogue produce frameworks that both sides can live with? Will government implement regulation that addresses real child safety concerns without creating impossible technical requirements? Will VPN companies follow through on their willingness to cooperate with reasonable rules? The conversation happening now will determine the answers to these questions, and those answers will reverberate globally as other jurisdictions watch how the UK handles this novel regulatory challenge.

Key Takeaways

- Major VPN companies proactively engaging with UK government represents industry maturation and strategic shift from resistance to collaboration

- Regulatory dialogue focuses on balancing child safety concerns with privacy protection and legitimate VPN uses rather than outright restrictions

- Transparency reporting and enhanced parental control features are likely compromise outcomes rather than extreme measures like mandatory age verification

- UK regulatory approach will likely influence policy in other jurisdictions including EU, Australia, and other English-speaking countries

- For users, VPN services will continue operating with minor changes focused on accountability and transparency rather than functionality restrictions

Related Articles

- France's VPN Ban for Minors: Digital Control or Privacy Destruction [2025]

- Indonesia Lifts Grok Ban: AI Regulation, Deepfakes, and Global Oversight [2025]

- Pornhub UK Ban: Why Millions Lost Access in 2025 [Guide]

- State Crackdown on Grok and xAI: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Pornhub's UK Shutdown: Age Verification Laws, Tech Giants, and Digital Censorship [2025]

- Payment Processors' Grok Problem: Why CSAM Enforcement Collapsed [2025]

![VPN Companies Engage UK Government on Children's Online Safety [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/vpn-companies-engage-uk-government-on-children-s-online-safe/image-1-1770122316656.jpg)