The 2026 Winter Olympics and Their Devastating Environmental Impact on Alpine Snow

Picture this: one of the world's most prestigious winter sporting events is about to unfold across the Italian Alps, yet the snow that makes it all possible is literally disappearing. That's the uncomfortable reality facing the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics, and a damning new report reveals just how bad things are about to get.

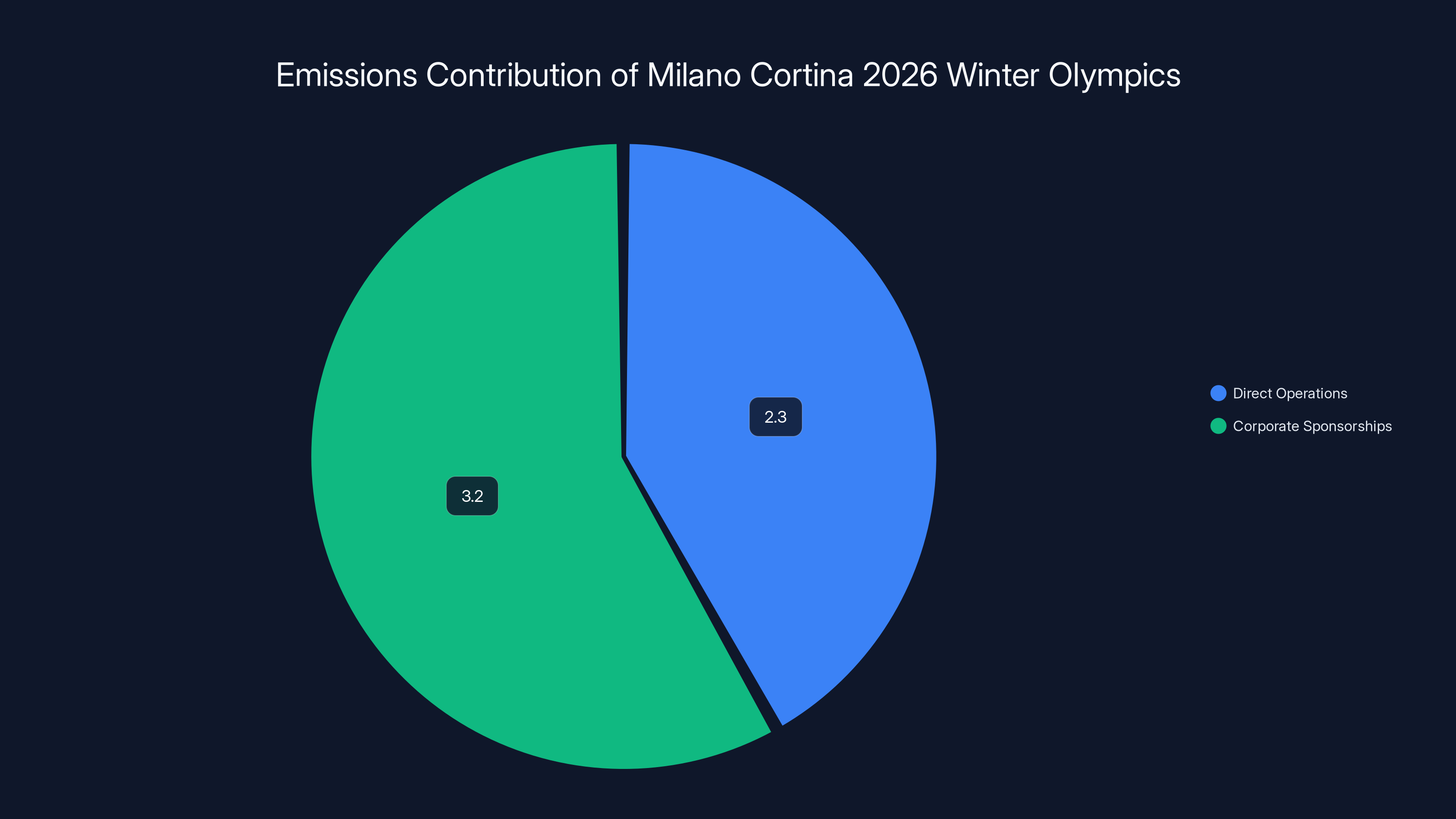

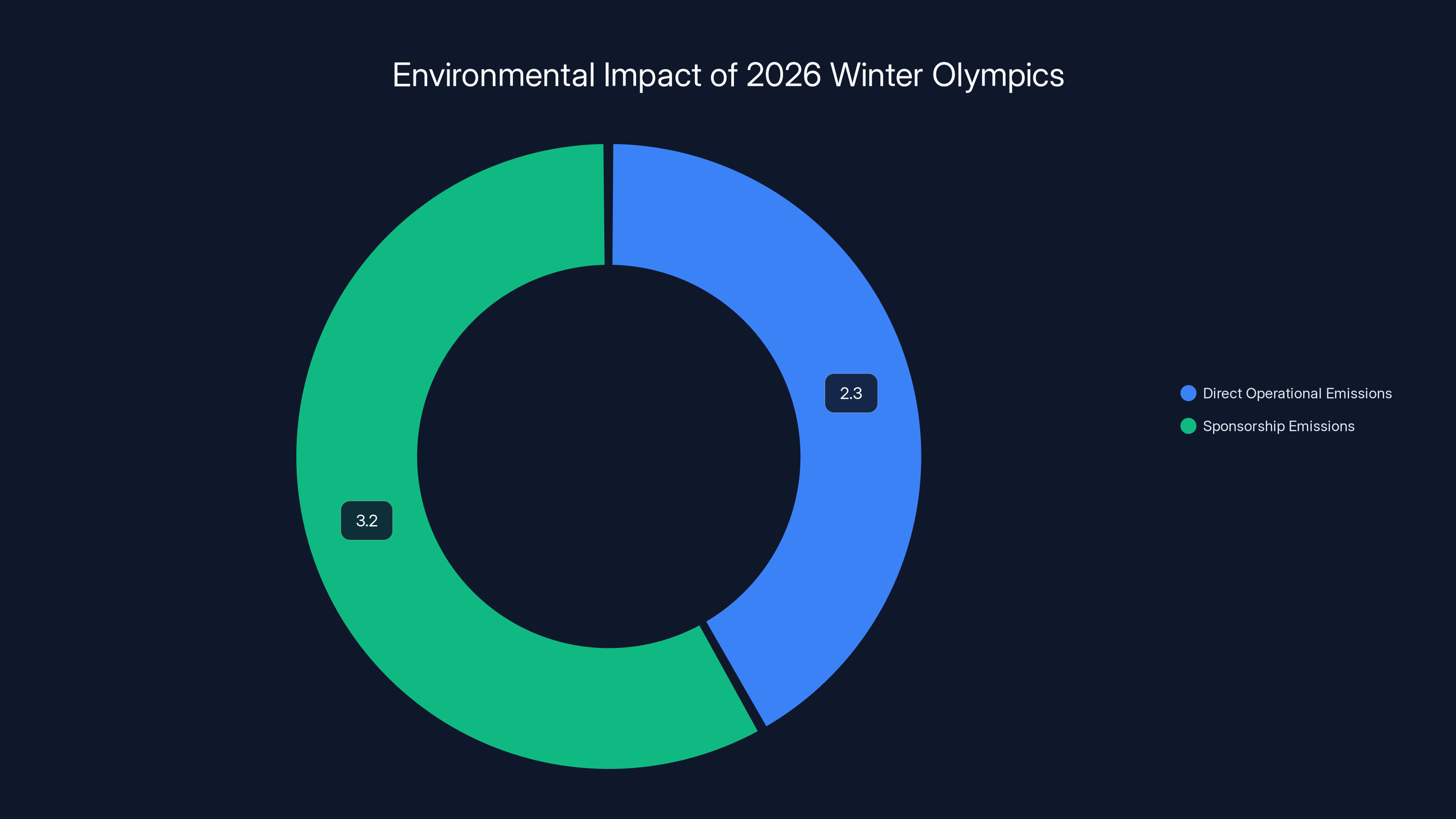

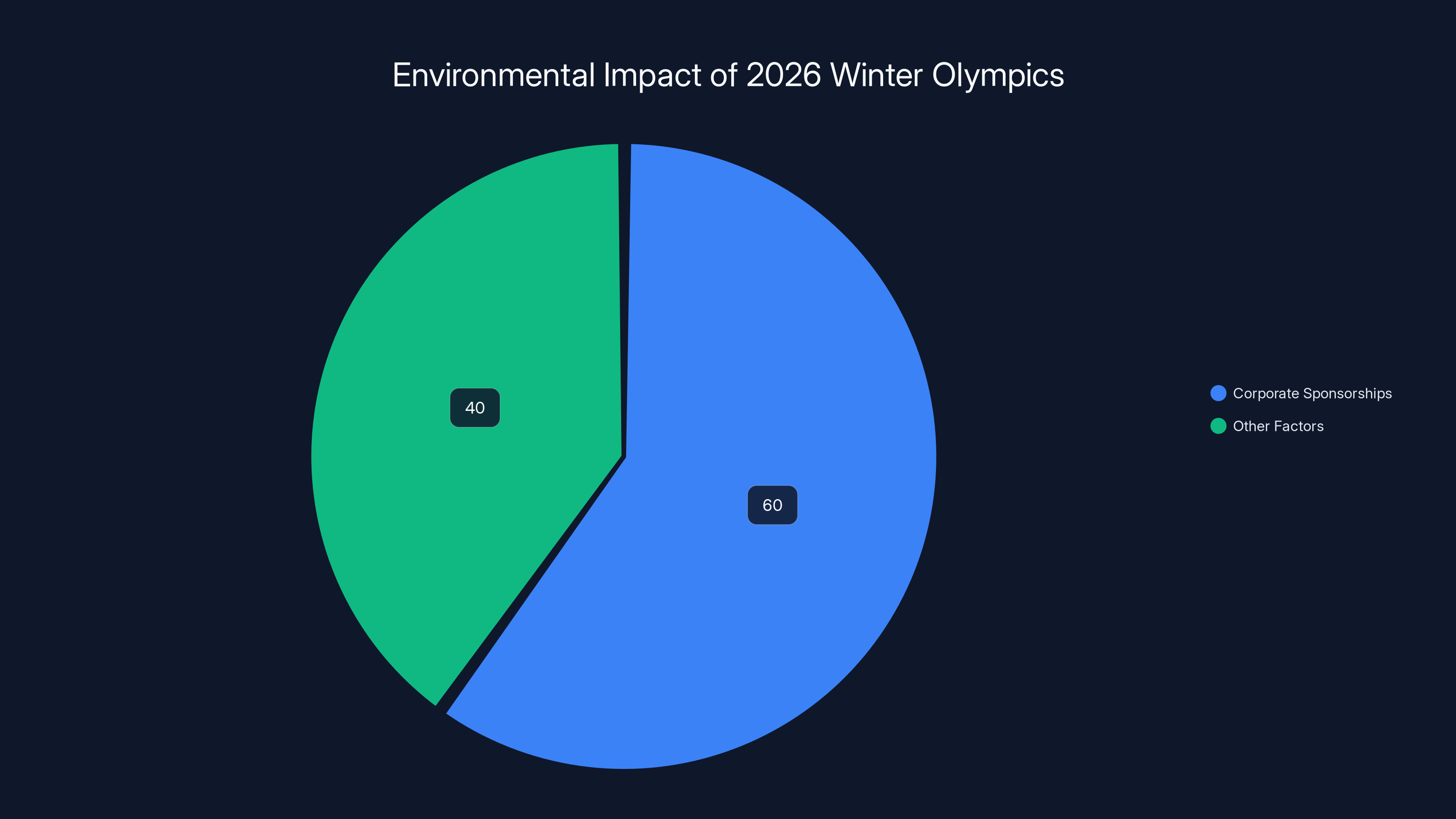

The numbers are staggering. The 2026 Games are projected to cause the loss of 5.5 square kilometers of snowpack—that's roughly equivalent to 1,400 football fields melting away. But it gets worse. The same games are estimated to contribute to the loss of 34 million metric tons of glacial ice. And here's where it gets truly infuriating: if we remove the carbon emissions from just three major sponsors, those numbers drop dramatically to 2.3 square kilometers of snowpack and 14 million metric tons of ice. That means the corporate sponsorship deals are responsible for roughly 60 percent of the environmental damage.

This contradiction sits at the heart of a complex crisis facing modern Olympic Games. The International Olympic Committee loves to tout sustainability commitments. Organizers in Milan and Cortina promised a "greener" Games. Yet the event is fueling the destruction of the very winter landscape that winter sports depend on. It's not just ironic—it's a perfect example of how well-intentioned initiatives can be undermined by the realities of global corporate carbon footprints.

A comprehensive January report from the New Weather Institute, developed in collaboration with Scientists for Global Responsibility and Champions for Earth, exposed these contradictions. The researchers didn't just count direct emissions from venue construction or athlete travel. They went deeper, examining how corporate sponsorships amplify the Games' true environmental cost. The findings should make anyone who loves winter sports uncomfortable, because they reveal a fundamental misalignment between hosting the Olympics and protecting the planet's remaining snow.

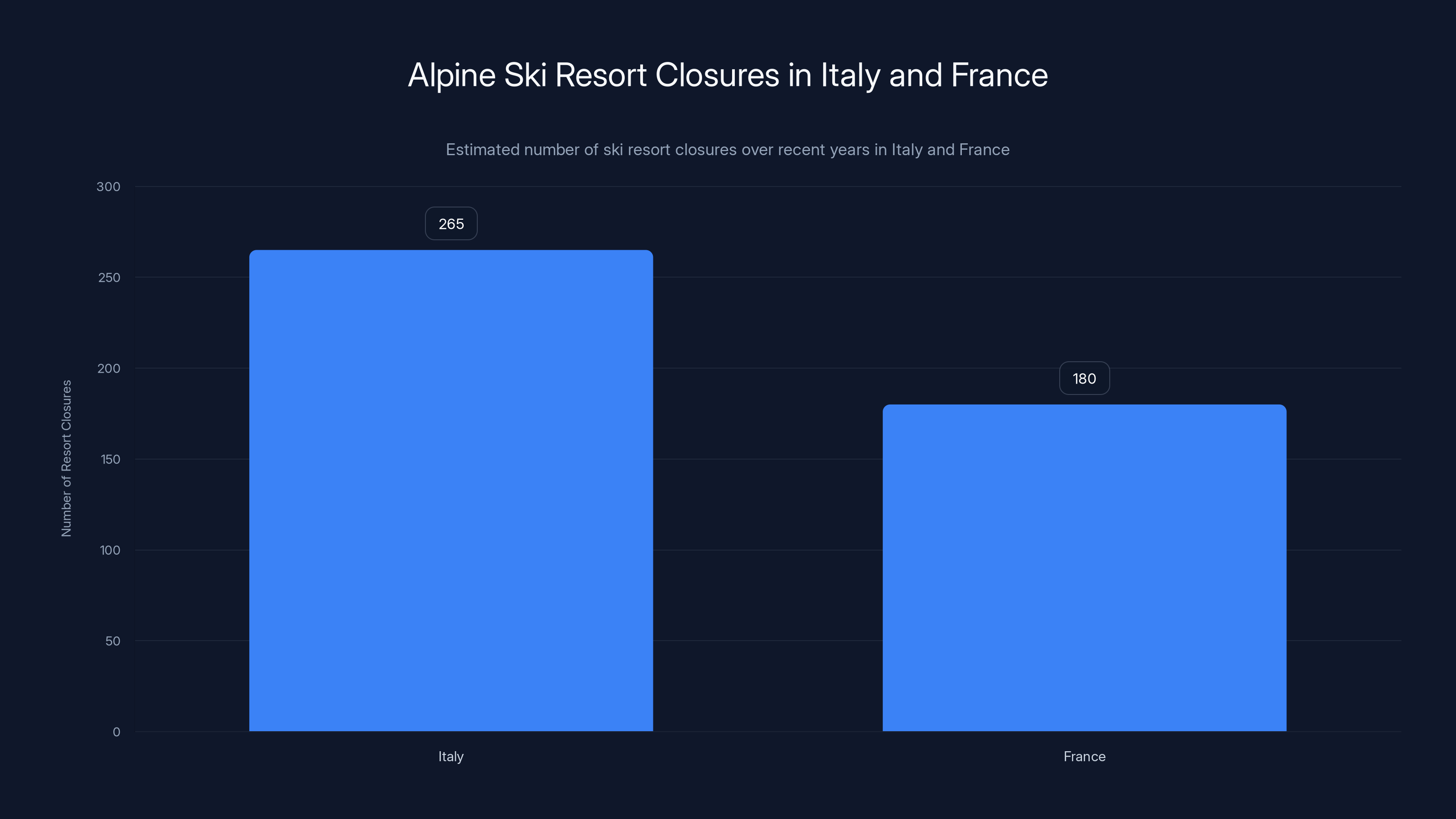

Winter sports are dying. That's not hyperbole—it's an observable fact with hard data behind it. In just the past five years, Italy lost 265 ski resorts. France, which will host the 2030 Winter Olympics, has watched more than 180 Alpine resorts close permanently. Switzerland has seen fifty-plus ski lifts and cable cars shut down. These aren't scattered closures in minor regions. These are complete losses of winter tourism infrastructure in some of Europe's most important ski areas.

The domino effect is becoming impossible to ignore. As resorts close, fewer people participate in winter sports. With fewer participants, funding for athlete development dries up. Young skiers and snowboarders lose the chance to train and compete at the local level. The talent pipeline shrinks. In two decades, winter Olympics might struggle to attract enough competitive athletes because there won't be enough snow anywhere to develop them.

So what exactly is happening to the snow, and why does one Olympics matter when climate change is a global problem? Understanding the specific mechanisms behind snowpack loss at the 2026 Games requires looking at both the direct and indirect emissions that the New Weather Institute calculated.

The Direct Carbon Footprint: What the Games Themselves Produce

Let's start with the obvious: hosting any major sporting event requires infrastructure. You need venues. You need roads and transportation networks. You need temporary buildings, broadcasting facilities, security apparatus, and housing for the thousands of athletes and workers who'll descend on the region. All of this construction, and all the operations during those two weeks in February, produces carbon emissions.

The New Weather Institute estimates that the Games' direct operational footprint—everything directly controlled by the Milano Cortina organizing committee—totals approximately 930,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. That's roughly equivalent to the annual carbon footprint of 200,000 cars driving continuously for a year.

But here's what makes this manageable: the organizers actually did a pretty good job minimizing direct emissions compared to previous Winter Olympics. How? By reusing existing infrastructure. They only built two new permanent venues, a dramatic reduction from Pyeong Chang 2018, which required six new permanent venues, or Sochi 2014, which built fourteen. This decision alone saved enormous amounts of construction-related emissions.

The transport situation improved too. Rather than constructing entirely new transportation networks, the organizing committee leveraged existing highway systems and rail infrastructure already in place across northern Italy and Switzerland. Athletes fly in, but they then use trains and regional buses to reach venues. It's efficient compared to previous Games that required building entirely new transportation ecosystems.

Snowmaking is another major direct emission source, though here the numbers get complicated. Modern snowmaking requires enormous amounts of energy—both to compress air and to chill water. At altitude, in cold weather, this is actually quite efficient. But the irony stings: you're burning fossil fuels to create the artificial snow that replaces the natural snow that climate change is destroying.

The Milano Cortina organizing committee actually uses some of the cleanest power grids in the world. Northern Italy and Switzerland run primarily on hydroelectric and nuclear power. That helps. But when snowmaking equipment runs at peak capacity in the weeks before the Games, it still draws significant power. The energy cost is lower than it would be in somewhere like Texas, but it's still consequential.

There's also the emissions from athlete travel. Every competitor, coach, and journalist flying to the games adds up. The spectators—the thousands of people traveling by car and plane—add even more. And the broadcasting infrastructure, with its satellite dishes, studios, and round-the-clock power requirements, contributes throughout the two-week event. Add it all together, and 930,000 metric tons for the direct footprint seems almost reasonable.

The problem is that 930,000 metric tons actually understates the real damage, because it doesn't account for what the New Weather Institute calls "promotional emissions."

Corporate sponsorships are responsible for a larger portion of emissions (3.2 sq km) compared to the direct operations of the Games (2.3 sq km), highlighting the significant impact of increased sales of carbon-intensive products.

The Sponsorship Problem: How Corporate Deals Multiply Emissions

Here's where the investigation gets really interesting, and where the numbers become damning. The Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics has major corporate sponsors. Top-tier partners include Eni, an Italian multinational oil and gas company; Stellantis, one of the world's largest automakers; and ITA Airways, Italy's national airline.

Now, sponsoring the Olympics doesn't directly make these companies produce extra emissions. But the New Weather Institute looked at what sponsoring actually means in terms of marketing value and increased sales. When Eni's logo appears on every broadcast of the opening ceremony, when Stellantis has a major exhibition at the sponsor zone, when ITA Airways runs Olympic-branded flights and promotions—these things drive sales.

And here's the thing: the products and services these companies sell are carbon-intensive. Eni sells oil and gas. Every liter of gasoline someone buys because they see Eni's Olympic branding represents additional carbon emissions. Stellantis sells cars, many of them internal combustion engines. Every vehicle sold by someone influenced by Stellantis' Olympic presence means carbon emissions for decades. ITA Airways sells flights, each one producing significant greenhouse gas emissions.

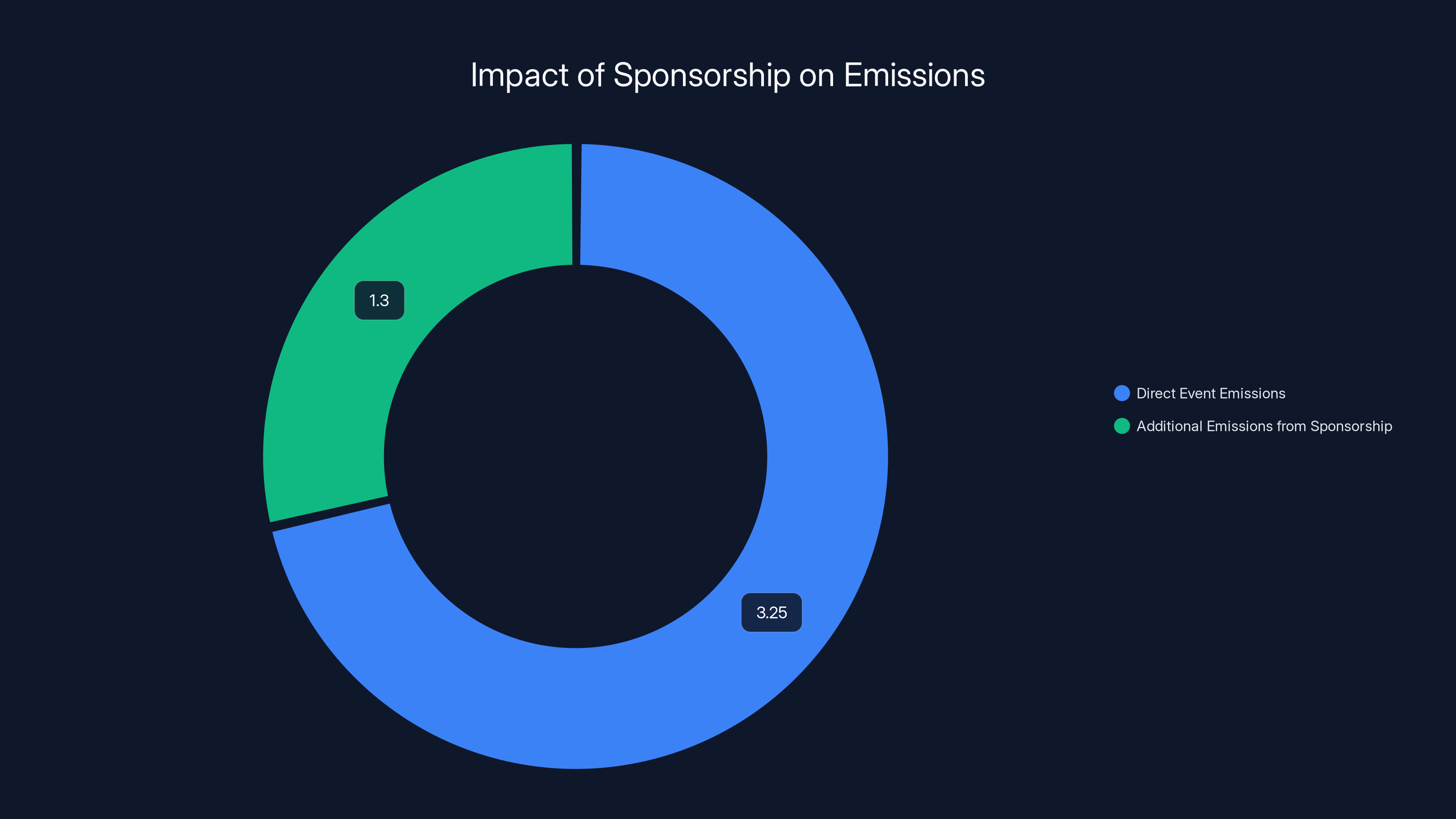

The New Weather Institute estimated that the promotional effect of these three sponsorships could drive 1.3 million metric tons of additional carbon dioxide equivalent emissions through increased sales. That's 40 percent more than the Games' direct footprint. Let that number sink in: the sponsorships could produce more than 40 percent additional emissions on top of hosting the event itself.

Why is this estimate so much larger than the direct footprint? Because these companies operate at massive scale. Eni produces enough oil and gas annually to power entire nations. When the Olympics boost brand visibility and public perception, even a one or two percent increase in sales translates into millions of tons of carbon. The report claims Eni alone is responsible for more than half of the 1.3 million metric ton sponsorship-related emissions.

Now, Eni's response to the report was predictable. An Eni representative told journalists that the report provided a "biased estimate" and noted that more than 90 percent of the fuels Eni supplies to power the Games come from renewable sources. But here's the thing: that defense only addresses the direct energy supply to Olympic venues, not the massive emissions from selling oil and gas to the general public. ITA Airways similarly pointed to its newer, more fuel-efficient fleet and future plans for sustainable aviation fuels. Stellantis didn't respond. Milano Cortina organizing committee declined to comment.

The defensiveness is telling. These companies know that their Olympic sponsorship deals are fundamentally at odds with climate commitments. And they know the New Weather Institute's methodology makes sense: if you're going to claim credit for "sustainable" games, you have to account for all the carbon your sponsors pump into the atmosphere.

The 2026 Winter Olympics could result in a total of 5.5 sq km of snowpack loss and 34 million metric tons of ice melting, with sponsorships contributing significantly to the environmental impact. Estimated data.

The Snowpack Math: How Much Snow Will Actually Melt?

Now we get to the core question: what does 1.3 million metric tons of additional carbon emissions actually mean for snow?

There's a mathematical relationship between atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration and glacier/snowpack loss. It's not perfectly linear—feedback loops complicate the picture—but scientists can estimate with reasonable confidence how much additional CO2 leads to how much additional melting.

The New Weather Institute used climate modeling to calculate that the 1.3 million metric tons of sponsorship-related emissions would cause an additional 3.2 square kilometers of snowpack loss and 20 million metric tons of glacial ice loss beyond what the Games' direct emissions would cause.

Adding the direct Olympic impacts (2.3 square kilometers of snowpack and 14 million metric tons of ice) to the sponsorship-related impacts (3.2 square kilometers and 20 million metric tons), you get the total: 5.5 square kilometers of snowpack and 34 million metric tons of glacial ice.

To put this in perspective, 5.5 square kilometers of snowpack is roughly equivalent to 1,400 football fields worth of snow. That snow would normally sustain skiing for an entire season across several resorts. The 34 million metric tons of ice is the weight of roughly 13,600 Empire State Buildings. This is real, physical matter—actual ice that exists now but won't exist in a few years—that's being subtracted from the Alpine landscape because of Olympic sponsorship deals.

But here's where it gets even more complicated. These aren't just numbers on a spreadsheet. This melting snow and ice has cascading effects. Alpine snowpack feeds water systems that supply millions of people with drinking water. Glaciers act as natural regulators of streamflow, releasing water during dry seasons. When you lose ice, you change river systems, water availability, and ultimately the viability of human communities downstream.

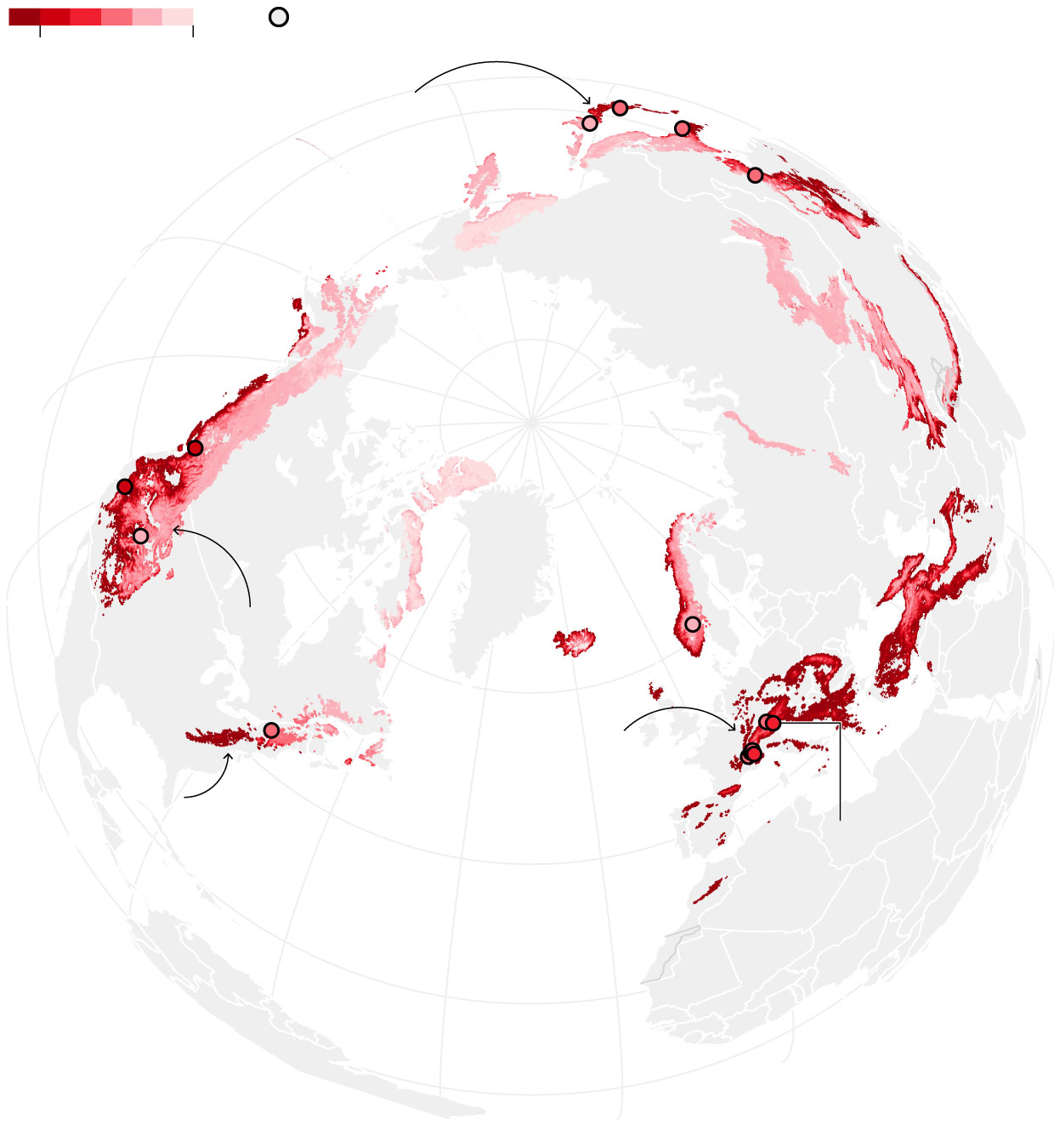

The Alps are already experiencing dramatic glacier loss. The Austrian Alps, the Swiss Alps, and the Italian Alps have all seen summer glacial retreat accelerate in recent years. Scientists predict that most Alpine glaciers below 3,500 meters will disappear entirely by 2100 if emissions continue on their current trajectory. The 2026 Olympics don't cause that long-term trend, but they accelerate it. They take a regional environmental crisis and make it measurably worse in the exact years and locations where winter sports infrastructure exists.

Historical Context: How Winter Olympics Have Changed

The 2026 Winter Olympics aren't unique in contributing to environmental damage. But the scale and nature of the problem has evolved dramatically over recent Winter Games.

Look at Pyeong Chang 2018 in South Korea. That Games required significantly more new permanent construction—six major venues—than Milano Cortina will need. The environmental impacts were substantial, but they were primarily direct impacts: construction, transportation, snowmaking. There wasn't as much analysis of corporate sponsorship emissions because the climate data and modeling capability didn't exist yet.

Then came Beijing 2022, which is actually hard to compare because COVID-19 zeroed out international spectator travel. That actually made Beijing's direct emissions lower than it would have been, even though constructing winter sports facilities in a relatively warm region of China required extensive snowmaking and energy investment.

Now Milano Cortina comes along at a moment when climate science is more mature, when we can actually measure and model the indirect effects of Olympic sponsorship, and when global awareness of climate crisis is dramatically higher. The report from the New Weather Institute wouldn't have been possible even five years ago. The data, the modeling capability, and the willingness to scrutinize corporate involvement simply didn't exist.

But this also raises a question: if Milano Cortina is actually one of the more sustainable recent Winter Olympics in terms of direct emissions (22 percent lower than Pyeong Chang when you remove the sponsorship effect), why is this moment so critical?

Italy has experienced 265 ski resort closures, while France has seen 180 closures, highlighting the severe impact of climate change on the Alpine winter sports economy. Estimated data.

The Viability Crisis: Why Winter Olympics Are Becoming Impossible

The answer lies in a fundamental shift in winter sports viability. Winter Olympics are becoming impossible to host sustainably anywhere on Earth.

Consider this: the International Olympic Committee commissioned a study in 2024 examining climate change impacts on host city viability. The researchers looked at the 93 locations globally with adequate infrastructure and hosting capacity for Winter Olympics. Out of those 93, only 52 will remain "climate-reliable" by the 2050s if global emissions continue at current rates. By the 2080s, that drops to 46. We're literally running out of places with reliable winter weather to host these games.

Milano Cortina sits at the northern edge of viability. The Alps still have snow, but it's becoming increasingly scarce and unpredictable. Snowmaking saves the Games, but snowmaking produces emissions. And those emissions further reduce snowpack, creating a vicious cycle.

This is the paradox the New Weather Institute identified: the Games celebrate winter sports while simultaneously contributing to the climate change that makes winter sports obsolete. It's not just unsustainable—it's actively corrosive to the thing being celebrated.

The resort closures across Europe reflect this reality. When natural snowfall declines, resorts lose revenue. When they're forced to invest in industrial snowmaking systems, operating costs skyrocket. And when resort economics deteriorate, they close. Italy lost 265 resorts in five years not because of any single event, but because the economics of winter sports in a warming climate are becoming untenable.

The Sponsorship Accountability Question

Here's what's particularly striking about the New Weather Institute's findings: they demonstrate that you could cut the environmental damage roughly in half simply by choosing different corporate sponsors.

Eni, Stellantis, and ITA Airways are all major, respectable international companies. They're not cartoon villains. But they're also carbon-intensive businesses. Replacing them with sponsors from renewable energy, electric vehicle manufacturing, or sustainable technology sectors would dramatically reduce the promotional emissions associated with the Games.

The math is remarkable. The report calculates that if Milano Cortina eliminated Eni, Stellantis, and ITA as sponsors and replaced them with low-carbon alternatives, the sponsorship-related emissions would drop from 1.3 million metric tons to essentially zero. The total Games footprint would shrink from 2.23 million metric tons (930,000 direct plus 1.3 million sponsorship-related) to around 930,000 metric tons.

Economically, this replacement would save roughly 1.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent without actually reducing sponsorship funding. Companies in renewable energy, sustainable technology, and green finance would be willing to sponsor Olympic Games as a brand alignment opportunity. In fact, they might be even more willing than fossil fuel and automotive companies, since such sponsorships would reinforce their market positioning.

But the IOC and Milano Cortina organizing committee haven't seriously considered this. Why? Because Eni, Stellantis, and ITA are major corporations with enormous budgets for sponsorship deals. They can pay premium rates. A renewable energy company might provide equal funding, but they'd need to be convinced of the value. And corporate sponsorship negotiations happen behind closed doors, with the details undisclosed.

This lack of transparency is part of the problem. The public doesn't know what these sponsors paid, what commitments they made, or whether alternatives were seriously considered. The New Weather Institute's report is essentially forcing a conversation that the IOC would probably prefer to avoid.

Replacing carbon-intensive sponsors with low-carbon alternatives could reduce sponsorship-related emissions from 1.3 million metric tons to zero, significantly lowering the overall environmental impact of the Games. Estimated data.

Artificial Snow: Technology and Its Limits

Let's talk about the technological solution that allows Winter Olympics to happen at all in an era of declining natural snowfall: artificial snowmaking.

Snowmaking technology has improved dramatically over the past two decades. Modern systems can produce snow at higher temperatures than older equipment, which is crucial in a warming climate. But the process is fundamentally energy-intensive and works best in cold, low-humidity conditions.

At Milano Cortina, snowmaking will occur at high altitude, primarily above 1,500 meters elevation, where temperatures remain cold enough to support snow production. The equipment involves powerful compressors that force air and water together at high pressure and low temperature, creating ice crystals that accumulate as artificial snow.

The energy requirement is substantial but defensible in terms of efficiency. Northern Italy's power grid derives roughly 40 percent of its electricity from hydroelectric sources and another 35 percent from nuclear power. Neither is perfectly clean—nuclear produces long-term waste, hydro disrupts river ecosystems—but both are dramatically cleaner than coal or natural gas. The carbon intensity of electric power in northern Italy is roughly one-quarter that of the global average grid.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: even with clean electricity, artificial snowmaking represents an acceptance that natural winter is no longer reliable. It's a band-aid solution. Once you start relying on artificial snow, you're locked into an escalating arms race with climate change. As temperatures rise, you need more snow production. As you produce more snow, you use more energy. As global energy use increases, atmospheric carbon rises, and temperatures increase further.

The 2026 Games will probably require snowmaking throughout their entire two-week duration. That wasn't always true for Winter Olympics. In the 1980s and 1990s, most Winter Olympic venues relied primarily on natural snowfall, with artificial snow as a backup. By 2022, Beijing used artificial snow exclusively because natural snowfall in that region was essentially non-existent. Milano Cortina will be somewhere in between: substantial natural snowfall supplemented by extensive artificial production.

This dependency on technology is actually one of the report's key findings. Winter Olympics can only continue through increasingly heavy reliance on artificial snowmaking. And that reliance creates a hidden carbon cost that's often invisible in official emissions accounting.

The IOC's Sustainability Commitments: Promises Versus Reality

In 2021, the International Olympic Committee made bold sustainability commitments. They promised to cut the Games' direct and indirect emissions by 30 percent by 2024 and 50 percent by 2030. These were actual, measurable targets, not vague aspirational language.

The IOC has claimed to have hit the first target. They point to Milano Cortina's efficient use of existing infrastructure as evidence of their commitment. And in terms of direct emissions, they're right—the 2026 Games will produce roughly 22 percent fewer direct emissions than Pyeong Chang 2018.

But the New Weather Institute's report highlights a massive gap in the IOC's sustainability framework: they're not counting the emissions from sponsors. The IOC's methodology accounts for direct emissions—venue construction, operations, athlete travel, spectator transport. But it doesn't count the carbon implications of having an oil company, an automotive manufacturer, and an airline as official partners.

This is a critical oversight, intentional or not. Because once you account for sponsorship emissions, the picture changes dramatically. Instead of achieving a 22 percent reduction from Pyeong Chang, Milano Cortina would actually be roughly 50 percent worse in terms of total carbon footprint if you include the promotional effects of major sponsors.

The IOC can credibly argue that they've optimized the direct operational footprint. But they're essentially ignoring Scope 3 emissions—the indirect emissions caused by sponsors' core business activities. It's like measuring a car company's sustainability by only counting the carbon from their manufacturing facilities while ignoring the emissions from all the cars they sell.

Stuart Parkinson, director of Scientists for Global Responsibility and lead author of the report, makes the case bluntly: "Winter sports can be part of the solution by cleaning up their act and abandoning dirty sponsors." But the IOC has shown no indication of implementing this approach for Milano Cortina or future Winter Olympics.

Corporate sponsorships are estimated to contribute to 60% of the environmental damage, highlighting the significant impact of sponsor-related emissions on snowpack and ice loss.

Regional Impacts: Italy and the Alpine Winter Sports Economy

The environmental impacts of the 2026 Olympics matter most at the regional level, where actual people, actual resorts, and actual communities depend on winter sports.

Italy is at the center of this crisis. The Italian Alps have experienced catastrophic glacier loss over the past 30 years. Marmolada, one of the Dolomites' most famous glaciers, shrank so dramatically that climbing routes became inaccessible. In summer 2022, a massive collapse of glacial ice killed 11 climbers, making visceral what climate scientists had been documenting for years: the glaciers are destabilizing.

The ski resort industry that depends on reliable winter snow is struggling. Italy's 265 resort closures over five years represent the loss of thousands of seasonal jobs and the abandonment of mountain communities. Ski resorts aren't just economic entities—they're the economic anchors for small Alpine villages. When a resort closes, the hotels, restaurants, equipment shops, and transportation services that depend on it all suffer.

Milano Cortina 2026 will temporarily boost the regional economy. Construction spending is already flowing. Hotels are being renovated. Tourism marketing is ramping up. The Games will bring international attention and investment to the region. But the report's findings suggest that this short-term boost comes with long-term environmental costs that will make the region's climate situation worse, not better.

France is facing an even more severe version of this problem. More than 180 Alpine resorts have closed in France, and France will host the 2030 Winter Olympics in the Alps. The conversation in France is already shifting: should the 2030 Games even happen, or should the IOC acknowledge that hosting Winter Olympics in the Alps is becoming environmentally indefensible?

Swiss ski resorts are consolidating, with smaller operators merging into larger corporations to survive. Switzerland has lost 50-plus ski lifts and cable cars in recent years. The industry is adapting by closing marginal operations and concentrating on higher-altitude resorts where snow remains more reliable. But this consolidation means lost jobs and reduced access for recreational skiers who can't afford to travel to the few remaining premium resorts.

The 2026 Olympics won't cause this regional crisis—climate change is doing that. But the Games will contribute measurably to the snowpack loss and glacial retreat that's already devastating the Alpine winter sports ecosystem.

Future Winter Olympics Viability: Where Can the Games Even Go?

The 2024 IOC study examining climate viability of Winter Olympic host cities paints a grim picture of the future.

The 93 cities with adequate winter sports infrastructure and hosting capacity includes places like Salt Lake City, Sapporo, Innsbruck, Cortina, St. Moritz, and various locations in the Canadian Rockies. Only 52 of these 93 locations will be reliably viable by 2050 if global emissions continue at current rates. And that's assuming global temperatures only rise by the median amount projected by climate models. If warming ends up on the hotter side of projections, viability drops even faster.

This viability crisis creates a cascading problem. As fewer locations are viable, the IOC has to choose from a smaller pool. This reduces competition for hosting rights, which strengthens the negotiating position of the few locations that remain viable. Host cities can demand more infrastructure investment, more exemptions from local regulations, and more favorable economic terms.

Furthermore, the locations that will remain viable tend to be wealthy countries: Switzerland, parts of the United States, Japan, possibly parts of Canada. Developing nations with strong winter sports traditions, like parts of Eastern Europe or Central Asia, may lose viability. This concentration of Winter Olympics in wealthy nations could actually entrench global inequalities by limiting opportunities for diverse countries to host and gain the associated benefits and exposure.

Salt Lake City, which hosted in 2002, is being discussed as a potential repeat host for 2034 or beyond. The U. S. location offers geographic stability—it's at high elevation with reliable winter precipitation. But hosting an Olympics every 30 years in the same city starts to look less like global diversity and more like geographic fatalism.

The other option some people suggest is moving Winter Olympics to permanent facilities in a location where the climate will remain viable longest. But this creates its own problems. It eliminates the opportunity for cities and nations to gain prestige and economic benefit from hosting. It reduces the festival atmosphere of temporary venues and transforming cities. It starts to make the Olympics feel like a predictable, routine event rather than something special.

In reality, the IOC is probably heading toward a future where Winter Olympics become increasingly concentrated in a handful of reliably cold locations, potentially in places where natural snow is augmented almost entirely by artificial production. It's not a future anyone actually wants, but it might be the only viability that climate change leaves us.

Estimated data shows that sponsorships could add 1.3 million metric tons CO2e, increasing the total emissions by over 40% beyond the event's direct footprint.

The Corporate Responsibility Argument

Why does the corporate sponsorship issue matter so much? Because it highlights a choice.

Companies like Eni, Stellantis, and ITA Airways aren't forced to sponsor the Olympics. They do it as a strategic business decision. They calculate that the brand value of Olympic association exceeds the cost of the sponsorship deal. They're betting that Olympic audiences will view them more favorably and be more likely to purchase their products and services.

If the public, the IOC, and host cities took the environmental cost of sponsorship seriously, they could change this calculation. A major fossil fuel company might think twice about sponsoring Winter Olympics if the sponsorship becomes associated with glacial destruction and snowpack loss. An automotive company might consider whether Olympic partnership is worth the PR risk if critics can point to studies quantifying how their sponsorship contributes to climate change.

But this requires transparency and public pressure. It requires the IOC to acknowledge the sponsorship emissions issue. It requires host cities to take environmental commitments seriously enough to actually implement them. And it requires public awareness that corporate sponsorships have real environmental consequences.

The New Weather Institute's report is trying to create that awareness. By quantifying the emissions from specific sponsors, they're moving the discussion from abstract climate impacts to concrete, measurable corporate responsibility. You can't argue with a number like "1.3 million metric tons of additional emissions from these three sponsors."

Will it change anything? That's unclear. The IOC hasn't responded substantively. The companies have offered defensive statements. Milano Cortina organizing committee declined to comment. But the report is now part of the public record. Future Olympic host cities will be asked about sponsorship emissions. Future corporate sponsors will face questions about their participation.

Eventually—maybe not for 2026, probably not for 2030, but eventually—the environmental math will become too obvious to ignore. A Winter Olympics that contributes to the disappearance of the environment that makes winter sports possible is logically indefensible. It's not even that far away.

The Broader Climate Reality: Why Winter Sports Matter

Winter sports might seem like a luxury concern in a climate crisis that threatens food systems, water supplies, and human habitation across vast regions. But there's something important about winter sports in the climate conversation.

Winter sports are a canary in the coal mine. They're a highly visible, widely understood, deeply cherished activity that's literally disappearing due to climate change. When people see glaciers melting, when beloved ski resorts close, when the snow they played in as children no longer falls reliably—that's when climate change stops being an abstract future problem and becomes a personal, present reality.

The decline of winter sports is also economically significant. The winter sports industry generates hundreds of billions annually globally. It employs hundreds of thousands directly and supports countless more indirectly. Communities across the Alps, the Rockies, the Andes, and mountainous regions worldwide depend on winter tourism and recreation.

More importantly, winter sports have cultural significance beyond economic impact. Winter Olympics represent human achievement, athletic excellence, and the celebration of winter itself. Hosting them in a way that's destroying winter is not just environmentally damaging—it's culturally self-defeating.

That's why the sponsorship emissions issue cuts so deeply. It's not just about carbon accounting. It's about the fundamental contradiction of celebrating winter while simultaneously fueling the climate change that eliminates winter.

What Alternative Sponsorship Looks Like

The report suggests that Milano Cortina could replace Eni, Stellantis, and ITA with low-carbon alternatives without losing sponsorship funding. What would that actually look like?

Renewable energy companies like Ørsted, Next Era Energy, or Italian company Enel could sponsor winter sports events with credibility and alignment of values. A renewable energy company's brand identity actually improves from Olympic association because the values align. Same with EV manufacturers like Tesla or NIO. Or sustainable aviation fuel producers and companies developing electric aircraft.

There are also technology companies that would eagerly sponsor winter sports if the opportunity existed. Snowmaking technology companies, for instance, could sponsor as a way to build brand awareness and credibility. Climate analytics and carbon accounting software companies could sponsor as a values statement.

The key difference is that these sponsors would be selling products and services that don't fundamentally contradict climate sustainability. A renewable energy company sponsoring winter Olympics and then selling more renewable energy is consistent with climate values. An oil company sponsoring winter Olympics while selling more oil is contradictory.

The financial argument works too. Yes, Eni, Stellantis, and ITA have enormous budgets and can outbid competitors. But renewable energy, EV, and green tech companies are increasingly well-capitalized. Over time, fossil fuel companies are likely to have less money to spend on sponsorships as capital markets increasingly divest from carbon-intensive industries. The economics could shift toward low-carbon sponsors naturally, as much as through intentional policy choice.

But none of this will happen without pressure. The IOC won't voluntarily eliminate fossil fuel sponsors. Host cities won't insist on it without political pressure. Companies won't volunteer to step back from prestigious sponsorship opportunities. Change requires visibility and accountability, which is exactly what the New Weather Institute's report provides.

The Path Forward: What Would Real Sustainability Look Like?

If Milano Cortina actually wanted to host a genuinely sustainable Winter Olympics, what would that require?

First, eliminate fossil fuel and high-emission corporate sponsors. This is non-negotiable if you're making any climate claims at all.

Second, offset remaining emissions. Not with dubious carbon credit schemes that often don't deliver real reduction, but through genuine, verifiable climate action funding. That means investing in renewable energy projects, supporting climate adaptation in vulnerable regions, or funding just transition programs for workers in fossil fuel industries.

Third, design venues and infrastructure for permanent community use after the Games. The two-venue-only approach for Milano Cortina is good, but could be better. Design facilities so that they serve local communities year-round, not just as Olympic venues.

Fourth, set strict limitations on spectator travel and encourage virtual attendance and local participation. International travel is necessary for athletes and essential personnel, but spectators could watch locally while experiencing the Games through community events.

Fifth, mandate that host countries commit to specific emissions reduction targets in the decade following the Games. Use Olympic hosting as a catalyst for deeper climate commitments, not just the Games themselves.

Sixth, invest in climate resilience for the host region. If Milano Cortina is hosting Winter Olympics, the region deserves climate adaptation funding proportional to the climate damage the Games are contributing to. Fund glacier research. Support resort transitions. Help communities adapt to climate change.

Seventh, make all data on emissions, sponsorships, and environmental impacts publicly available. The current practice of opaque sponsorship deals and unclear emissions accounting breeds exactly the kind of distrust that the New Weather Institute's research is now generating.

Would these steps make Milano Cortina a truly sustainable Olympic Games? Probably not. The mere act of hosting an international event of this scale generates environmental impact that's difficult to fully offset. But implementing even some of these measures would demonstrate actual commitment rather than greenwashing.

The Reckoning Coming for Winter Olympics

The Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics represent a turning point, though few people recognize it yet.

This will be one of the last Winter Olympics that can realistically be hosted in the Alps. The 2030 Games in France, assuming they happen, will be one of the few remaining opportunities in this iconic region. By 2050, Alpine skiing as we know it might not be viable at all. The glaciers will be gone. The reliable snowfall will be a memory.

What happens then? Do Winter Olympics move permanently to high-latitude locations like northern Scandinavia or Russia? Do they shift to perpetually snowy regions like the Antarctic (which would be absurd for a thousand reasons)? Do they simply stop happening?

Or do we take the next five to ten years to actually address the underlying problem: climate change itself? That's the only real solution. The 2026 Olympics aren't important because of what they'll contribute to climate change—they're important because they're happening right now, at this moment, when we still have time to make a difference.

If a major international sporting event can't be held in a way that's aligned with climate reality, what does that tell us? It tells us that climate change is so advanced that even the most prestigious, well-resourced, well-intentioned international events can't avoid contributing to the problem. That's not an indictment of the Olympics. It's an indictment of how far we've fallen behind on climate action.

The New Weather Institute's report isn't trying to cancel the 2026 Winter Olympics. They're trying to wake everyone up to the contradiction between celebrating winter sports while destroying the conditions that make them possible. For Milano Cortina, that moment is now. In a few years, when people look back at the 2026 Games, they'll either remember them as a wakeup call or as a monument to our inability to act even when the stakes are crystal clear.

FAQ

How much snowpack will the 2026 Winter Olympics actually cause to melt?

The New Weather Institute report estimates that the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics will contribute to the loss of 5.5 square kilometers of snowpack, which is roughly equivalent to 1,400 football fields of snow. This includes both direct emissions from the Games themselves (2.3 square kilometers) and emissions from corporate sponsorships (3.2 square kilometers). Additionally, the event is projected to contribute to the loss of 34 million metric tons of glacial ice—a staggering amount of permanent ice that would normally sustain Alpine communities and ecosystems.

Why do corporate sponsorships contribute more emissions than the Games themselves?

Corporate sponsorships contribute more emissions because they drive increased sales of carbon-intensive products and services. When Eni sponsors the Olympics, it gains brand visibility that leads to higher oil and gas sales. When Stellantis sponsors, it drives automobile sales. When ITA Airways sponsors, it increases flight bookings. The New Weather Institute estimates that these three sponsors' increased business due to Olympic visibility could generate 1.3 million metric tons of additional carbon dioxide emissions—roughly 40 percent more than the Games' direct operational footprint of 930,000 metric tons.

What would happen if Milano Cortina replaced its major sponsors with low-carbon alternatives?

If Milano Cortina replaced Eni, Stellantis, and ITA Airways with renewable energy companies, EV manufacturers, or green technology companies, the sponsorship-related emissions would essentially drop to zero. The total Games footprint would shrink from 2.23 million metric tons (combining direct and sponsorship emissions) to approximately 930,000 metric tons. The report estimates this replacement would save 1.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions without reducing sponsorship funding, demonstrating that environmental responsibility and financial viability aren't mutually exclusive.

How have ski resorts been affected by climate change in recent years?

The impact has been catastrophic across the Alpine region. Italy has lost 265 ski resorts in just the past five years, France has lost more than 180 Alpine resorts, and Switzerland has seen fifty-plus ski lifts and cable cars close. These closures represent not just the loss of tourism infrastructure but the collapse of the economic foundation for many mountain communities. Many of these resorts have been operating for decades and represent generational family businesses. As reliable natural snowfall declines and operating costs rise due to expanded snowmaking requirements, smaller and marginal operations are becoming economically unviable.

Which countries will still be able to host Winter Olympics by 2050?

According to a 2024 International Olympic Committee-commissioned study, only 52 of the 93 locations globally with adequate winter sports infrastructure will remain "climate-reliable" by 2050 if emissions continue at current rates. This number drops further to 46 by the 2080s. The viable locations will likely be concentrated in wealthy nations like Switzerland, Canada, the United States, and Japan—largely in high-elevation regions and places with historically reliable winter precipitation. This concentration raises concerns about equity and the ability of developing nations to ever host Winter Olympics.

Is artificial snowmaking a viable long-term solution for Winter Olympics?

Artificial snowmaking allows Winter Olympics to happen despite declining natural snow, but it's not a genuine long-term solution. Snowmaking is energy-intensive and requires temperatures cold enough for production—increasingly rare as global temperatures rise. At Milano Cortina, the clean Northern European power grid (roughly 40 percent hydroelectric and 35 percent nuclear) makes snowmaking relatively efficient, but it still generates emissions. More importantly, reliance on artificial snow represents an acceptance that natural winter is no longer reliable and locks Olympic organizers into an escalating technological arms race with climate change. As temperatures rise, more snowmaking is required, which consumes more energy and generates more emissions.

What commitments has the IOC made to reduce Olympic emissions?

In 2021, the International Olympic Committee committed to cutting the Games' direct and indirect emissions by 30 percent by 2024 and 50 percent by 2030. The IOC claims to have achieved the first target, pointing to Milano Cortina's efficient reuse of existing infrastructure—only two new permanent venues required, compared to six for Pyeong Chang and fourteen for Sochi 2014. However, critics argue that the IOC's methodology fails to account for Scope 3 emissions—the indirect emissions from corporate sponsors' core business activities. When sponsorship emissions are included, Milano Cortina's total carbon footprint would actually be roughly 50 percent larger than Pyeong Chang rather than 22 percent smaller.

How do winter sports connect to broader climate change awareness?

Winter sports serve as a visible, personally meaningful indicator of climate change. When people experience declining snow in their childhood skiing areas, when beloved resorts close, when glaciers shrink visibly—climate change stops being abstract and becomes a direct personal loss. This makes winter sports important in the climate conversation not because they're economically dominant (though they are significant), but because they're culturally and emotionally resonant. The decline of winter sports makes climate change tangible for hundreds of millions of people worldwide, which is why the contradiction of hosting Winter Olympics while contributing to climate change is so significant.

Conclusion

The 2026 Milano Cortina Winter Olympics will be remembered for far more than athletic achievements. They'll be remembered as a moment when the world's most prestigious winter sporting event became an uncomfortable symbol of our climate crisis.

A report released in January 2025 by the New Weather Institute quantified something that should have been obvious: you can't celebrate winter sports while simultaneously fueling the climate change that destroys winter. The numbers are devastating. Direct operational emissions will cause 2.3 square kilometers of snowpack loss and 14 million metric tons of glacial ice melting. But the really troubling discovery is that just three corporate sponsors—Eni, Stellantis, and ITA Airways—could be responsible for even more damage through the emissions generated by increased sales of their carbon-intensive products.

The 1.3 million metric tons of additional emissions from sponsorship deals will cause 3.2 square kilometers of additional snowpack loss and 20 million metric tons of glacial ice melting. Combined with direct Olympic impacts, the total comes to 5.5 square kilometers of snowpack and 34 million metric tons of ice—a staggering amount of permanent environmental damage concentrated in the exact region where winter sports infrastructure exists.

What makes this particularly frustrating is that it's not inevitable. The New Weather Institute's research demonstrates that replacing high-emission corporate sponsors with low-carbon alternatives would reduce total sponsorship emissions to essentially zero without decreasing sponsorship funding. It's not a question of sacrifice or economic trade-offs. It's simply a question of choice—and the IOC, Milano Cortina, and the corporate sponsors have chosen not to make that change.

This isn't a problem unique to 2026. The same contradiction will plague the 2030 Winter Olympics in France, and even more so for future Games. Climate change is already closing ski resorts across the Alpine region. Italy has lost 265 resorts in five years. France has lost more than 180. The ski industry is consolidating and contracting. Within one or two decades, the Alps may not have enough reliable winter conditions to host Olympic Games at all.

We're rapidly approaching a world where Winter Olympics can only happen in a handful of locations. Those locations will probably become permanent or semi-permanent, losing the festival atmosphere and international participation that makes the Olympics special. Or the Games will simply stop happening, which might actually be the most honest outcome.

But in this moment—right now, in 2025, as Milano Cortina prepares for 2026—there's still a choice. The Games could proceed as planned, contributing to climate damage while pretending to be sustainable. Or they could actually align their corporate partnerships with their environmental rhetoric. It's not too late for that change, though the window is closing.

The athletes competing in Milano Cortina are training right now, many of them on ski slopes and in mountains that have less snow than they did a decade ago. They're competing in a sport that's becoming increasingly marginal and precarious due to climate change. The least the Olympic movement could do is make sure the event celebrating their sport doesn't actively accelerate the destruction of the conditions that make their sport possible.

The New Weather Institute's report has made the choice clear. The question now is whether the IOC, host cities, and corporate sponsors have the courage to act on what the data is screaming at them.

Key Takeaways

- The 2026 Milano Cortina Winter Olympics will directly cause loss of 2.3 sq km of snowpack and 14 million metric tons of glacial ice due to operational emissions

- Corporate sponsorships from Eni, Stellantis, and ITA Airways could cause 1.3 million metric tons of additional emissions—40% more than the Games' direct footprint—through increased sales of carbon-intensive products

- Only 52 of 93 global locations with winter sports infrastructure will remain climate-reliable by 2050, forcing Winter Olympics into geographic and economic concentration

- Italy, France, and Switzerland have closed 495+ ski resorts in five years as climate change makes winter sports economically unviable

- Replacing major sponsors with low-carbon alternatives would reduce sponsorship emissions to zero without reducing funding, revealing that sustainability is a choice, not an economic necessity

Related Articles

- 12 Athletes Making History at 2026 Winter Olympics [2025]

- AI Data Centers Drive Historic Gas Power Surge [2025]

- Data Centers & The Natural Gas Boom: AI's Hidden Energy Crisis [2025]

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

- How to Watch the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony [2025]

- How Olympic Torchbearers Are Chosen for 2026 Winter Olympics [2025]

![2026 Winter Olympics Environmental Impact: Snowpack Loss and Climate Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/2026-winter-olympics-environmental-impact-snowpack-loss-and-/image-1-1770318607685.jpg)