The Unexpected Energy Crisis at the Heart of AI

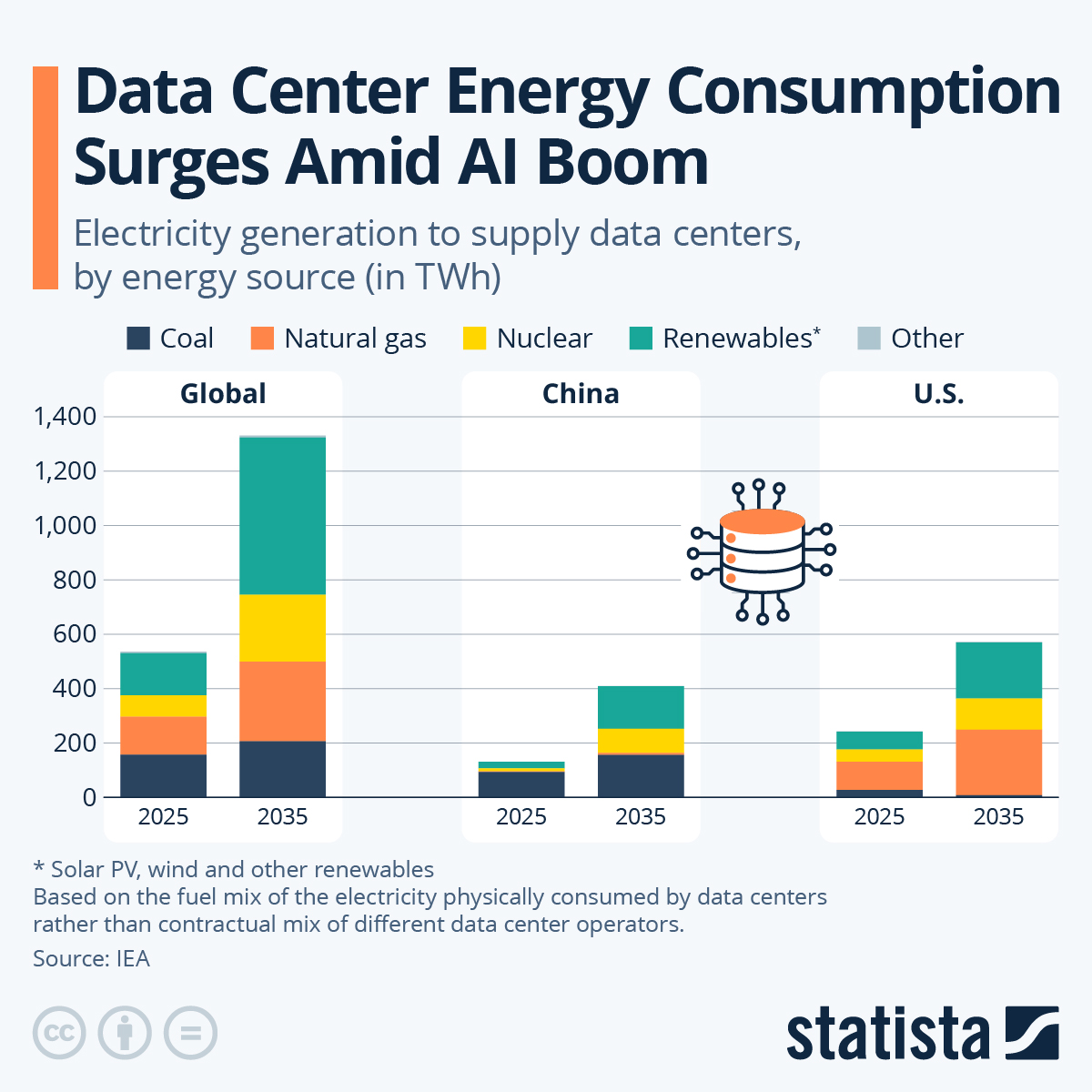

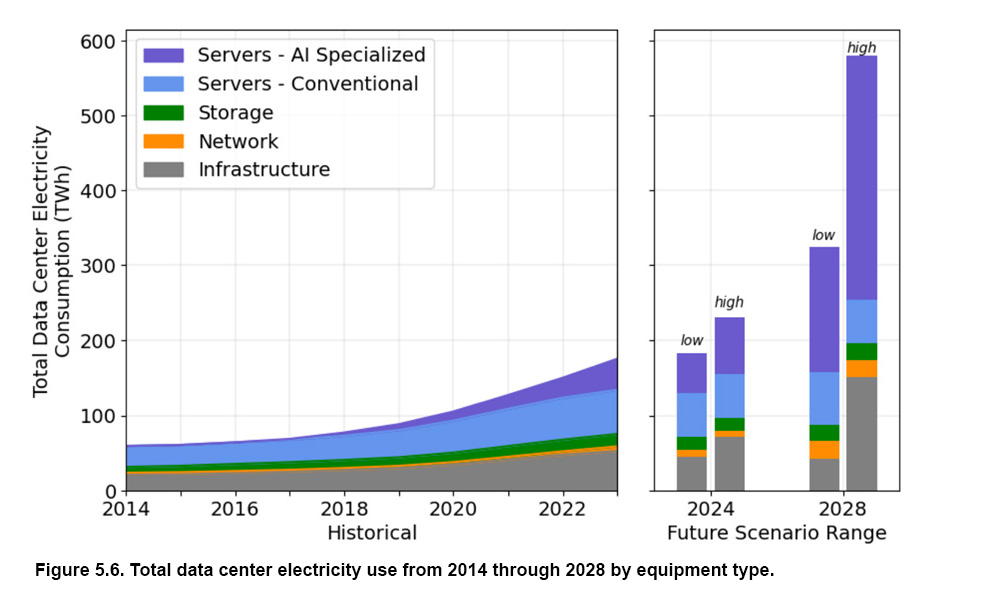

Something weird is happening in the energy sector, and it's directly tied to the AI boom sweeping through tech. For the first time in two decades, natural gas is experiencing a renaissance that nobody really saw coming. Not because we suddenly decided it was clean (it's not), but because data centers running generative AI consume absolutely staggering amounts of electricity.

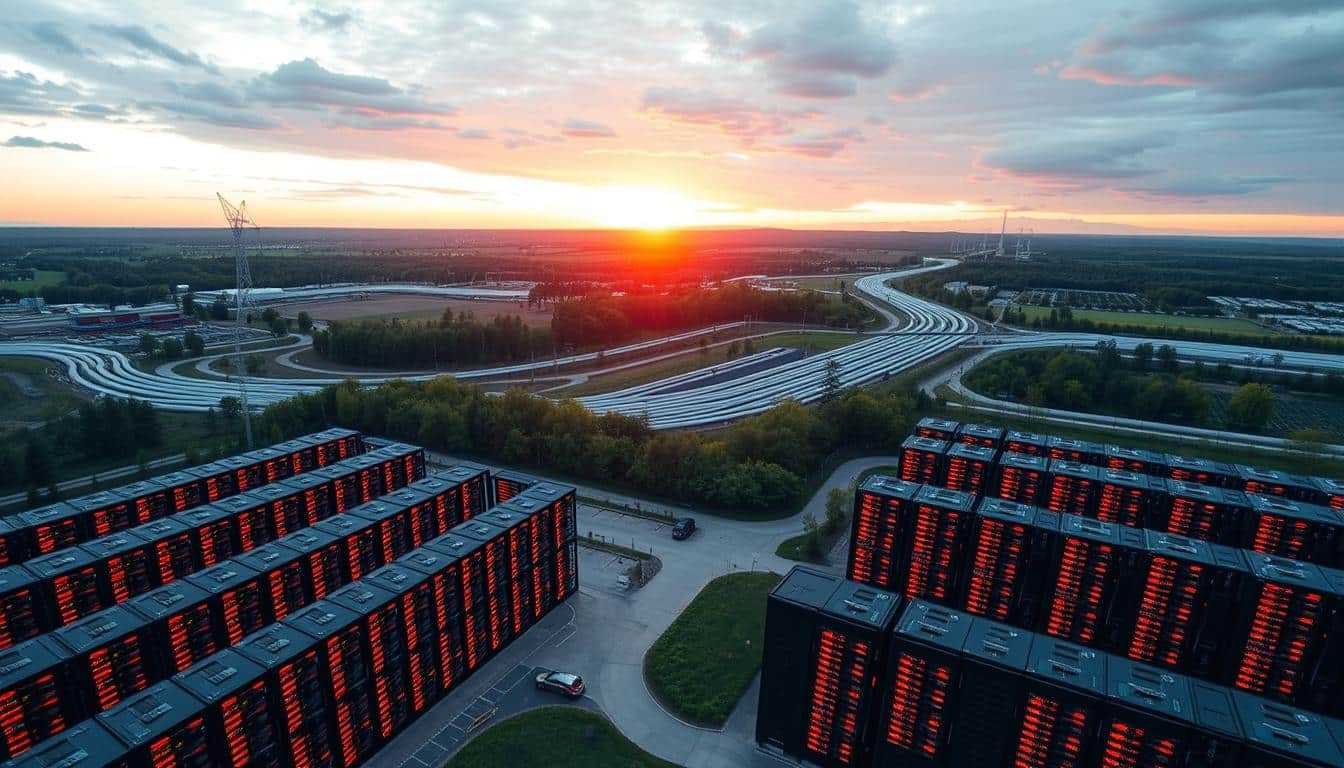

Let me paint you a picture. A single modern AI data center can consume as much power as a mid-sized city. We're talking megawatts of sustained demand, 24/7, with no off switch. This isn't like traditional data centers that handle web traffic and emails. These facilities train and run large language models, process billions of inference requests daily, and do it all while keeping hardware cool enough not to melt. The power requirements are genuinely unprecedented.

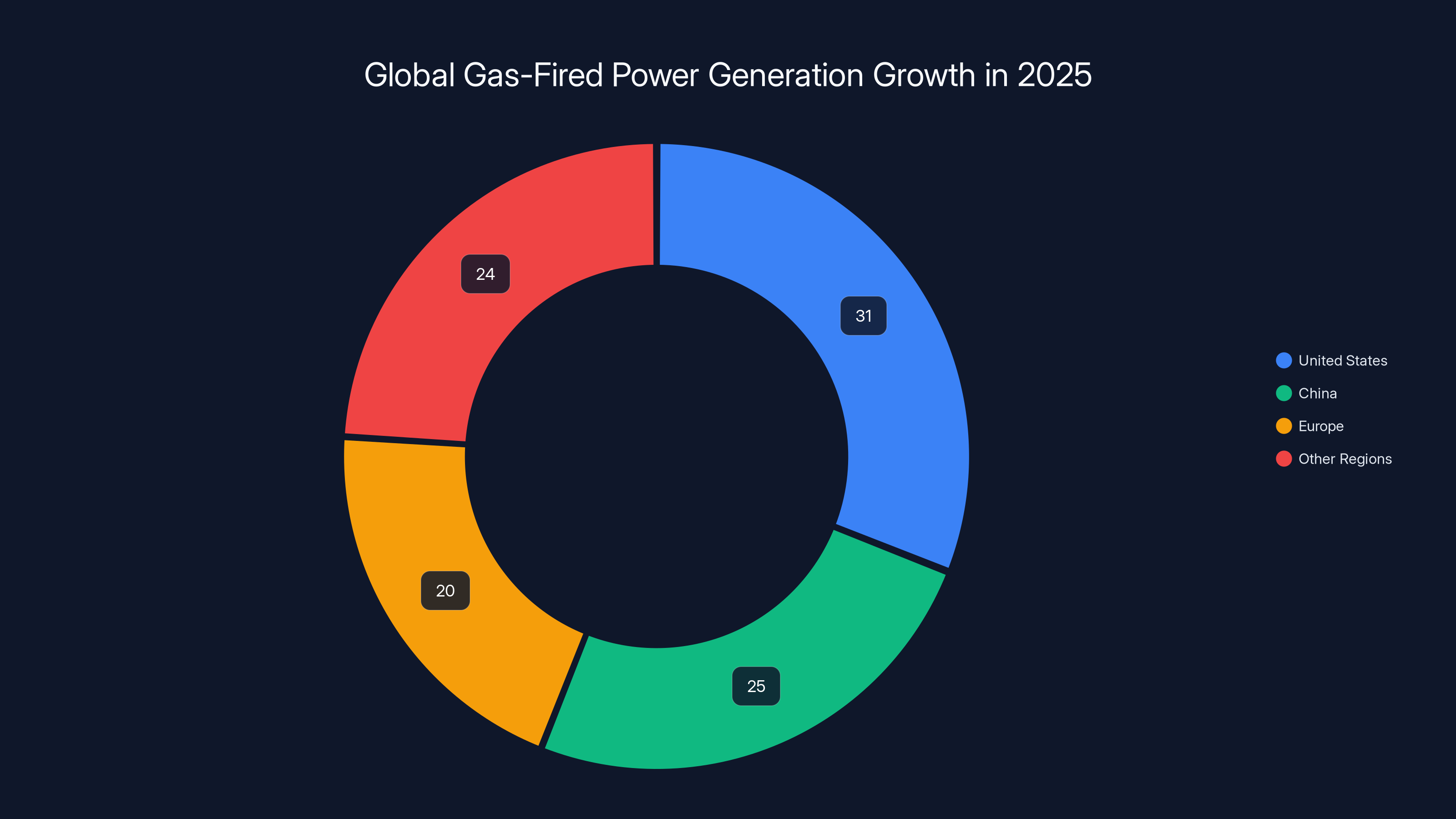

Here's what's changed: Gas-fired power generation in development globally jumped 31% in 2025 alone. That's the fastest growth rate in over two decades. And it's not evenly distributed. More than a quarter of that added capacity is headed to the United States, which just surpassed China for the first time as the country with the biggest increase in planned gas projects. Even more striking, more than a third of the US gas expansion is explicitly designed to power data centers.

Why gas and not renewables? That's the uncomfortable question at the center of this story. Solar and wind are cheaper per kilowatt-hour and getting cheaper. But they're intermittent. They don't run 24/7 the way data centers demand. Gas plants offer dispatchable power, meaning you can turn them up or down based on demand. They can be built relatively quickly compared to nuclear or hydroelectric infrastructure. And right now, in the race to capture the AI market, speed matters more than anything else.

But here's the thing that keeps energy policy experts up at night: we're potentially locking ourselves into decades of fossil fuel dependence just as the world made a historic commitment to move away from it. The Paris Agreement, signed by nearly every country in 2015, set out a plan to limit global warming by transitioning to clean energy. But we're moving in the opposite direction. With Trump's administration actively pushing fossil fuel infrastructure and pulling back climate regulations, the US is becoming the poster child for this reversal.

I got curious about whether this is actually necessary or if it's more about speed and convenience. The answer? It's complicated. There genuinely isn't enough renewable energy capacity built out right now to power data centers at this scale. But there's also a chicken-and-egg problem. Companies aren't investing in renewable buildout because it's slower. So we default to gas because it's available now. And every gas plant built becomes a sunk cost that utilities have to recoup over 20-30 years, which creates pressure to keep it running and burning fuel.

TL; DR

- 31% global surge: Gas-fired power in development jumped 31% in 2025, the fastest growth in over two decades

- US leads expansion: America surpassed China as the country with the biggest increase in new gas projects

- AI drives third: More than a third of new US gas capacity is explicitly planned for AI data centers

- Climate reversal: This trend directly contradicts Paris Agreement goals and recent renewable energy progress

- Infrastructure locked in: New gas plants create 20-30 year commitments that could become stranded assets if AI demand doesn't materialize

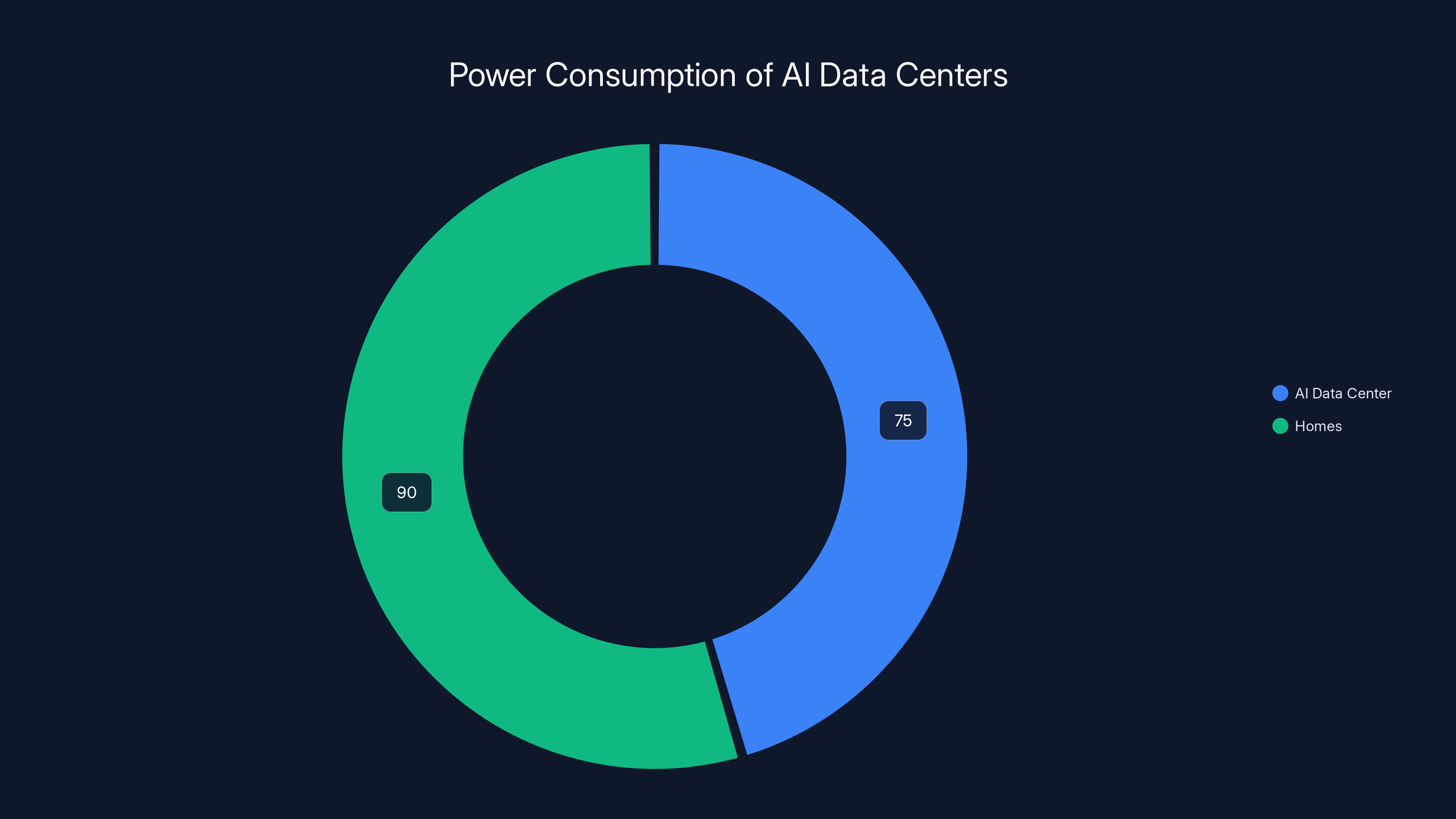

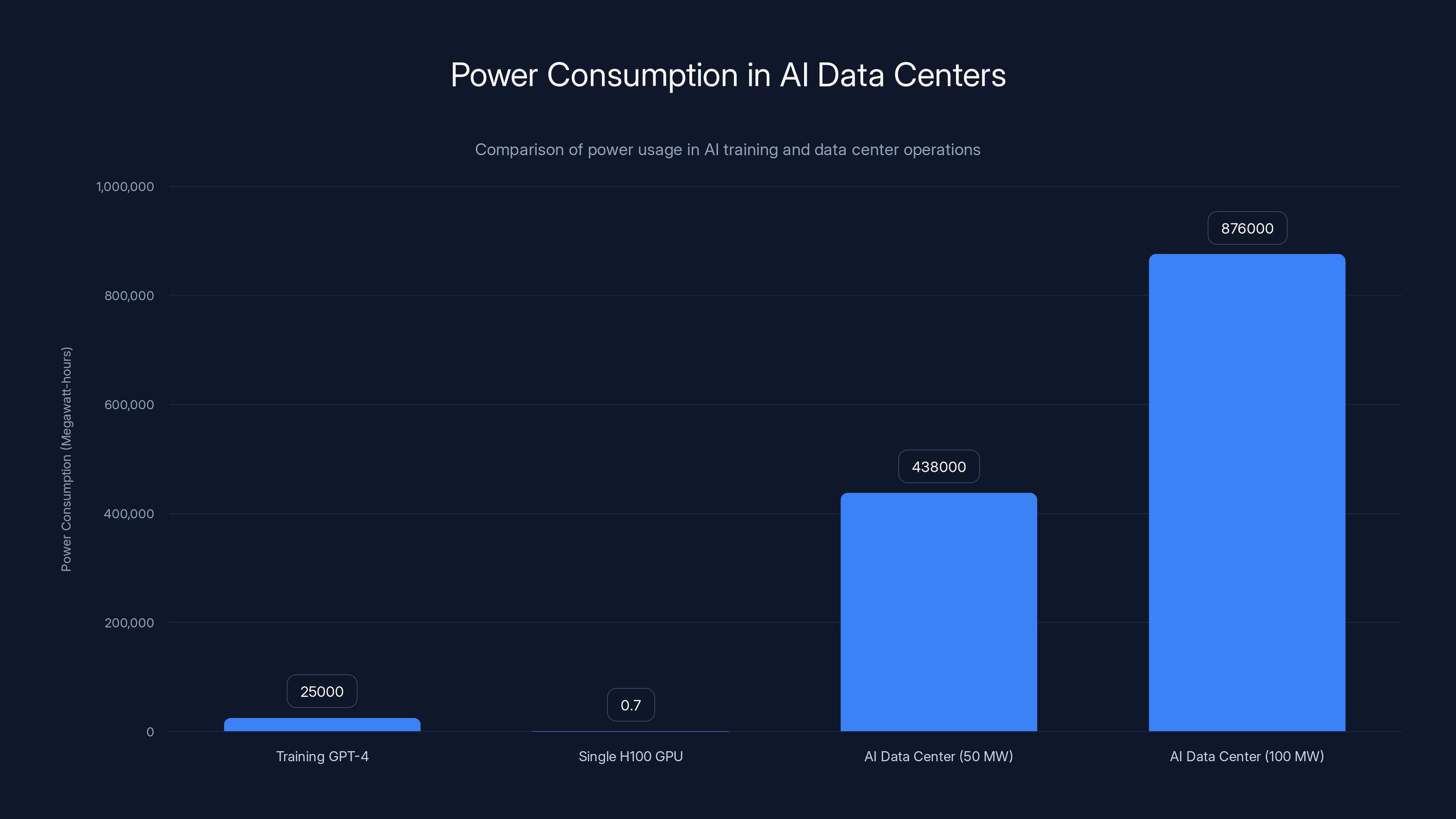

A single AI data center can consume 50-100 megawatts, equivalent to powering 80,000-100,000 homes. Estimated data based on typical values.

Why AI Data Centers Consume So Much Power

Let's start with what makes AI different from regular computing. When you run Chat GPT in your browser, the heavy lifting happens on a server somewhere. But that server isn't just retrieving pre-written answers from a database. It's running matrix multiplications across neural networks with millions or billions of parameters. Every token it generates requires calculations that would have been considered supercomputer-grade not that long ago.

Here's a concrete example: Training a single large language model like GPT-4 requires roughly 25,000 megawatt-hours of energy. That's enough to power a home for several years. A single training run. And companies aren't training models once and stopping. They're constantly refining, tuning, and retraining. OpenAI, Google, Meta, and other major players are running training operations around the clock.

But training is only part of the story. Inference—actually running the model to answer user questions—is where the scale becomes mind-bending. When a million people ask Chat GPT questions simultaneously (which happens), every single one of those requests spawns a computation that needs processing power. Multiply that across multiple models, multiple companies, and continuous operation, and you start to understand why data center operators are essentially buying power plants.

Nvidia's H100 GPUs, the chips that power most AI inference, consume about 700 watts each. A single AI data center might have tens of thousands of these chips. That's tens of megawatts just for compute, plus cooling systems, networking equipment, storage, and redundancy infrastructure. Some estimates suggest the power consumption of a hyperscale AI data center is 50-100 megawatts sustained. That's not a datacenter anymore. That's an industrial facility.

The math is brutal. A 100-megawatt data center running continuously consumes 876,000 megawatt-hours per year. For comparison, that's roughly equivalent to the annual power consumption of 80,000 to 100,000 American homes. A single facility. The fact that we're planning to build dozens of these in the coming years explains why utilities are scrambling to find power sources.

What's interesting is that cooling is often overlooked. Data centers require water for cooling, and that water has to be cold. In some regions, this creates a secondary constraint beyond just raw power capacity. Some proposed data centers have been delayed or rejected because there wasn't adequate water access. But gas plants themselves require cooling water, so you end up needing both the power plant AND the data center competing for the same limited cooling resources.

There's also the question of whether current consumption estimates are accurate. We're seeing wild projections about future AI power demand, but a lot of these are guesses based on architecture assumptions that could change. If companies figure out more efficient inference methods, or if quantum computing becomes practical for certain AI workloads, the power requirements could drop significantly. But right now, we're planning infrastructure based on the assumption that demand keeps growing exponentially. And once that infrastructure exists, there's enormous pressure to keep it running and justifying its existence.

In 2025, global gas-fired power generation capacity is projected to grow by 31%, with the United States leading the increase, surpassing China for the first time. Estimated data.

The Gas Plant Building Frenzy Explained

The speed of gas infrastructure deployment is staggering. A natural gas power plant can be built and operational in 3-4 years if there are no permitting delays. Compare that to solar farms (1-2 years) or nuclear plants (10-15 years). In the race to capture AI market share, faster wins.

But there's a policy dimension here that's reshaping the entire energy landscape. Trump's "AI Action Plan" explicitly prioritizes fast-tracking fossil fuel infrastructure for data centers. This means permit approvals are being expedited, environmental reviews are being shortened, and regulatory obstacles that would normally slow projects are being removed. The message from Washington is clear: get these plants built now, worry about environmental consequences later.

Utilities are responding predictably. They're announcing gas projects that would have been controversial five years ago. A major utility operator told industry analysts that they're expecting to add 150+ gigawatts of gas capacity over the next five years, almost exclusively driven by data center demand. That's roughly equivalent to 150 large coal plants worth of additional capacity, but running on natural gas instead.

The economics are straightforward. Companies like OpenAI, Google, and Meta have incredible capital. They can sign long-term power purchase agreements with utilities. These contracts guarantee revenue for 15-20 years, making it incredibly attractive for utilities to build new plants. From the utility's perspective, this is guaranteed business. The capital markets love it because it's predictable cash flow.

What's happening at specific sites tells the story. The Stargate data center being built in Abilene, Texas by OpenAI is getting its own dedicated gas turbine plant under construction. This isn't a data center plugging into the grid. This is bringing the power plant to the data center, and the power plant's entire purpose is serving one facility. This model is becoming standard.

In Virginia, which has become a major data center hub, the situation is becoming constrained. Dominion Energy announced they're looking at adding 15+ gigawatts of new capacity by 2035, almost entirely for data centers. But here's the problem: Virginia doesn't have unlimited gas pipeline capacity. So they're now looking at building new pipelines, which creates additional environmental concerns and adds to project timelines.

The speed of this transition is remarkable. Five years ago, the narrative was "coal is dying, renewables are the future." Now the narrative is "we need dispatchable baseload power for AI, so we're building gas." Entire business models that were built around renewable energy growth have been disrupted by this shift. Solar installers are being redirected to industrial projects. Microgrids that were planned to be renewable-heavy are suddenly being paired with gas plants.

The Environmental Reckoning Nobody Wanted

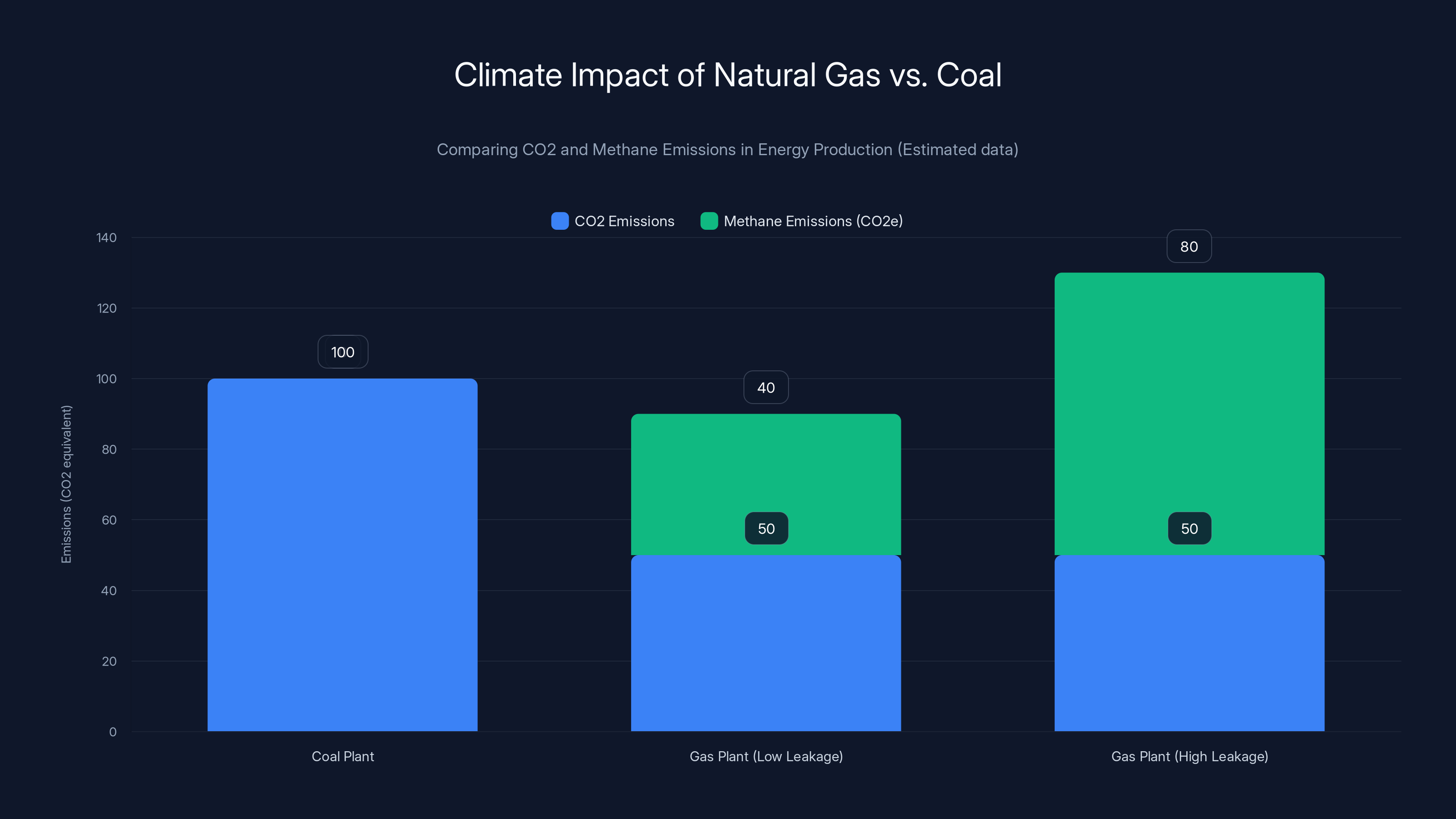

Here's where it gets dark. Burning natural gas produces CO2, same as coal and oil. Yes, less CO2 per unit of energy than coal, but it's still carbon pollution. Natural gas is about 50% less carbon-intensive than coal for power generation, but that's not the full picture.

Methane emissions are the real problem. Natural gas is mostly methane, and when you extract, process, and transport it, some percentage escapes into the atmosphere. That's called "fugitive emissions," and it's much worse than the CO2 you produce by burning the gas. Methane is roughly 80-90 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 over a 20-year timeframe, though it breaks down in the atmosphere faster.

Take a typical natural gas supply chain. You have leakage at extraction sites (hydraulic fracturing operations). You have leakage in pipelines—sometimes 1-3% of the gas escapes during transport. You have leakage at processing facilities and at the power plants themselves. Some researchers estimate that total methane leakage from the US natural gas system is equivalent to 30-40% of the carbon reduction we achieved through switching from coal to gas in the first place. We're not getting the climate benefits we think we are.

When you add it all up, the climate impact of a new gas plant built for AI data centers could be nearly as bad as building a coal plant, depending on how much methane leaks through the supply chain. And we're building dozens of them.

The math on this is worth understanding:

If upstream leakage is 5-7%, which is realistic for modern US operations, you're looking at a significant climate cost that doesn't show up in simple carbon calculations.

What's particularly frustrating is that this wasn't inevitable. In 2022-2023, solar and wind capacity was being added faster than it ever had been. Renewable energy was outpacing fossil fuels in new capacity additions for the first time. Battery storage technology was improving rapidly. We were on a trajectory toward actual decarbonization.

Then AI happened. The sudden, massive power demand created a window of crisis. And instead of being managed as a constraint that forces innovation (pushing companies to build renewable farms and storage), it was treated as a permission slip to expand fossil fuels. Utilities got to justify gas plants. Tech companies got to scale faster. Governments got to boast about AI investments.

But here's what keeps policy experts worried: these plants will still be running in 2050. They'll be producing CO2 and methane for decades. The Paris Agreement's target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 requires essentially all fossil fuel infrastructure to be retired by then. Every new gas plant is a plant that will have to be closed before it reaches the end of its technical life. That's an inefficient use of capital and a costly climate policy failure.

The stranded asset risk is real. If AI demand doesn't grow as expected—and there's genuine uncertainty about whether AI will become as economically transformative as hype suggests—these plants become liabilities. A gas plant that was supposed to run for 30 years and retire in 2055 might need to be decommissioned in 2040 if demand doesn't materialize. That's a multi-billion-dollar write-off for utilities.

AI data centers consume massive amounts of power, with a single training run of GPT-4 using 25,000 MWh and large data centers consuming up to 876,000 MWh annually.

Methane Leakage: The Hidden Carbon Cost

When natural gas companies talk about "clean burning natural gas," they're technically correct but deeply misleading. The burning process is relatively clean. But everything before the burning is leaky.

Hydraulic fracturing operations in the US release significant methane. A study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that methane emissions from oil and gas operations were 25% higher than industry estimates. They measured actual atmospheric methane over oil and gas regions and found concentrations that couldn't be explained by reported emissions, meaning companies were underreporting leakage or researchers' models were wrong. (Spoiler: companies were underreporting.)

Pipeline transport adds another layer of loss. Natural gas infrastructure is decades old in many regions. The American Gas Association estimates that 1-2% of gas is lost in transmission and distribution in the US, which doesn't sound like much until you realize that's millions of tons of methane annually.

Processing facilities where raw natural gas is refined into pipeline-quality gas release methane during condensation and handling. These releases are often vented rather than captured because the economic incentive to capture them is minimal.

Then there's the power plant itself. Gas combustion turbines operate at various efficiencies depending on design, age, and operating conditions. Modern plants might be 40-45% efficient, meaning 55-60% of the fuel's energy is wasted as heat. That's not methane leakage, but it's inefficiency that matters for the overall energy economics.

When you model all of this together, the effective carbon intensity of natural gas power is much higher than the simple "burn the gas, get CO2" calculation suggests. A plant that appears to emit 400 metric tons of CO2 per megawatt-hour might actually be responsible for 600+ metric tons when you include upstream methane.

This is why serious climate scientists don't view natural gas as a transition fuel to renewables. It's more like a different path that delays transition. You build a gas plant, it's cheaper to run than coal, you defer renewable investments, and suddenly you have stranded capacity preventing any further transitions.

Some utilities are starting to model this. A few have incorporated upstream methane calculations into their carbon accounting. But most haven't. And government policies still often treat natural gas as "cleaner" without this accounting.

The Political Machine Behind the Expansion

There's a policy feedback loop happening right now. Tech companies lobby for fast-tracked permitting for data centers. Fossil fuel companies lobby for relaxed environmental regulations and faster approval processes for gas plants. Utilities lobby for long-term cost recovery guarantees. And sympathetic administrations push through deregulation and permit streamlining.

The Trump administration's "AI Action Plan" explicitly states that removing environmental regulations is necessary for US competitiveness in AI. The reasoning goes: if the EU requires more rigorous environmental review for gas plants, projects will just move to the US where they can be built faster and cheaper. That's a classic regulatory arbitrage argument, and it's compelling to politicians focused on economic growth.

But it's a race to the bottom. The US wins the data center infrastructure race by having fewer environmental constraints, but the climate cost is global. CO2 and methane in the atmosphere don't care which country they came from.

What's particularly notable is how quickly this policy consensus formed. Two years ago, Biden's administration was pushing clean energy investments through the Inflation Reduction Act. Today, data centers are exempt from some of the permitting requirements that other industrial facilities face. The narrative has shifted from "we must transition away from fossil fuels" to "we must build fossil fuel infrastructure to support AI faster than China does."

International dynamics matter too. China is building AI capacity rapidly, and the geopolitical concern in Washington is that if the US can't build data centers and supporting infrastructure faster than China, American tech companies will lose the AI race. That sense of urgency is overriding climate commitments.

Congressional mandates are starting to reflect this. Some bills moving through Congress would explicitly streamline environmental review for data center infrastructure. The Department of Energy has been directed to prioritize data center power needs in its infrastructure planning. This isn't abstract policy—it's manifesting as actual permitting decisions that put gas plants online faster.

One interesting tension: federal renewable energy tax credits are still law. So you have one part of government providing subsidies for solar and wind, while another part is fast-tracking gas plants. The market dynamics end up favoring gas because of timeline advantages, not cost advantages.

State-level politics are even more fragmented. Texas, which has massive data center growth, has been happy to approve new gas capacity because it expands the economy and tax base. Virginia, another hub, is more divided between climate concerns and economic opportunity. California, facing data center expansion pressure, has been more resistant but still approving facilities at a steady pace.

The Renewable Energy Paradox

Here's the frustrating part: solar and wind could actually power data centers. The technology exists. Solar costs have fallen 90% in the last decade. Wind is now competitive with gas on a pure $/MWh basis in most of the country. Battery storage is improving exponentially.

But there's a mismatch between renewable generation patterns and data center demand. Solar generates peak power mid-day. Wind is often stronger at night. Data centers need power 24/7. That requires either:

- Massive amounts of battery storage to shift renewable energy temporally

- Geographically distributed data centers located where renewable resources are abundant

- Overbuilding renewable capacity and accepting curtailment (wasting some renewable energy)

- Hybrid systems combining renewables, storage, and some dispatchable generation

All of these are viable. But they're slower and require more upfront capital investment than just building gas plants.

There's also a biomass consideration. Some companies are exploring biomass power for data centers, which is technically renewable but comes with its own environmental concerns. If biomass harvesting becomes unsustainable, you're just swapping one carbon problem for another.

The real issue is project timelines. A 500-megawatt solar farm plus 500-megawatt battery storage facility could take 3-4 years to permitting plus build. A 500-megawatt gas plant takes 3-4 years total. Same timeline. But gas plants have established supply chains, standardized designs, and known costs. Renewable farms with storage are more novel, more complex, and carry more technical risk.

Capital costs are similar or slightly favoring renewables when you include battery storage. But operational uncertainty still favors gas plants in the eyes of conservative utility planners.

What's changing, though, is corporate pressure. Some major tech companies have committed to powering their operations with 100% renewable energy. Google, Microsoft, and Meta all have public renewable energy targets. But meeting those targets through procurement in competitive renewable energy markets is different from powering new data centers with renewable energy. They're finding that the easiest path is buying renewable energy credits (which are cheap) rather than physically building or contracting actual renewable facilities.

There's also a scale problem. Renewable energy development is fragmented. Solar and wind projects are typically in the 50-500 MW range. Data centers are moving toward 100-500 MW facilities. Matching the scale requires either combining multiple renewable projects or building dedicated solar farms at unprecedented scale.

Some companies are trying this. Apple built a solar farm in California specifically for its data center. Google has contracted for gigawatts of wind and solar capacity. But they're still buying gas power to supplement.

The path forward would require policy changes: guaranteed long-term renewable energy procurement contracts for data centers, tax incentives for renewable-plus-storage projects, requirements that data centers be powered by a minimum percentage of renewable energy. But those changes aren't happening in the current political environment.

Regional Impacts and Water Stress

Not all regions are equally affected by this boom. Texas is seeing the most dramatic buildout. The state has cheap land, pro-business regulation, abundant natural gas infrastructure, and strong renewable resources. It's the perfect location for data centers. But it's also creating infrastructure strain.

Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the entity managing Texas's power grid, is stressed. Peak demand has been growing 5-7% annually, driven by data centers. The grid was designed with redundancy for weather events, but new demand is consuming that redundancy. In summer 2024, Texas came close to rolling blackouts due to data center demand combined with heat waves.

The response has been to approve more generation, primarily gas plants. But this creates a feedback loop: more generation capacity attracts more data centers, which drives more demand. It's a self-reinforcing cycle.

Water is becoming another constraint. Natural gas plants require enormous amounts of water for cooling. A 500-megawatt gas plant might consume 2-5 billion gallons of water annually. In water-stressed regions like the Southwest, this is a serious problem.

Texas has water concerns, but they're less severe than Arizona or New Mexico. Some proposed data centers in Arizona have been delayed or rejected because of water availability issues. The state already allocates Colorado River water to agriculture and municipal use, and there's limited capacity for industrial cooling.

Virginia is in a different situation. It has adequate water for now, but data center density is increasing rapidly around Northern Virginia. Some projections suggest that by 2035, data center power demand could represent 30% of total state electricity demand. That's reshaping long-term infrastructure planning.

International regions are experiencing different pressures. Ireland has become a major data center hub for European companies, but it's facing pushback over water usage and power grid constraints. The country is considering restricting new data center approvals.

The Netherlands is dealing with similar issues. Data centers consume about 8% of Dutch electricity, and new facilities are being delayed due to grid capacity constraints. This is pushing some companies to look at locations with more available power infrastructure.

In some ways, power availability is becoming the limiting factor for data center expansion. Companies want to build facilities, but they can't get power commitments. This is actually creating some pressure for renewable energy investment. If you can't get a guarantee of gas plant capacity, renewable plus battery storage starts looking more viable.

Local environmental groups are mobilizing in some regions. There's increasing opposition to new gas plants in Virginia, Maryland, and California. Environmental organizations argue that these plants are exactly what should be retired, not built. This is creating political friction that's slowing approvals in some areas.

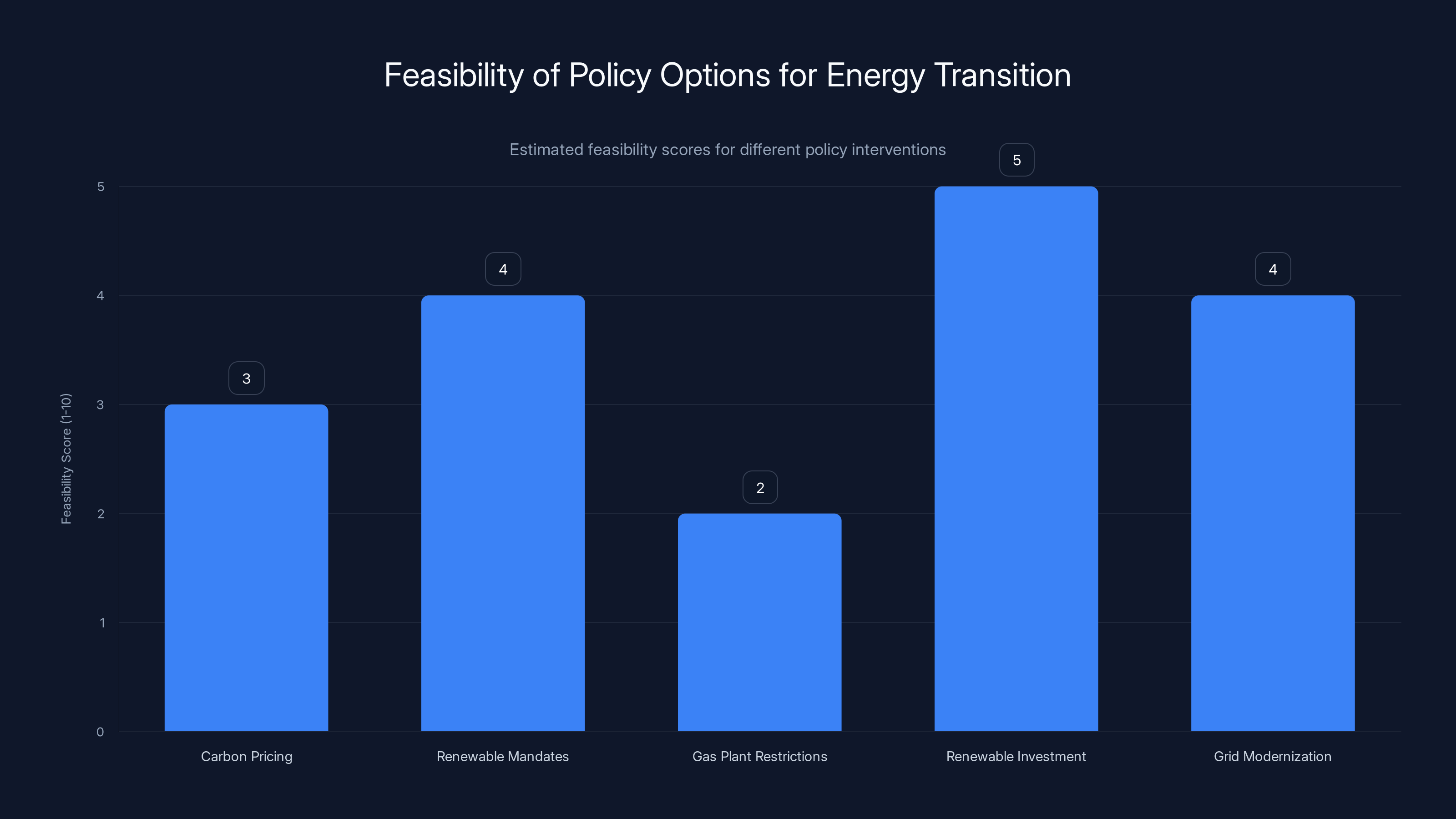

Estimated feasibility scores suggest that massive renewable investment is slightly more feasible than other options, though all face significant challenges. Estimated data.

The Uncertainty Around AI Demand Itself

Here's the uncomfortable reality that nobody wants to discuss: we don't actually know if AI will need this much power long-term.

The projections for AI power demand are based on assumptions. Companies assume that AI will be as prevalent as the internet. That every task that can be AI-assisted will be. That inference demand will grow 5-10% annually for the next decade.

But what if that doesn't happen? What if AI becomes a niche tool for specific applications rather than pervasive infrastructure? What if the hype cycle cools down and investment slows?

There are historical precedents. The dot-com boom led to massive overbuilding of internet infrastructure. Companies built data centers that were only 10-20% utilized before the bubble burst. Some of those facilities were converted to other uses. Many were just abandoned.

Could the same happen with AI data centers? It's possible. If AI doesn't deliver the transformative economic benefits that are promised, demand could stall. Companies could cancel planned expansions. And suddenly you're left with gas plants built to serve demand that never materialized.

This is exactly what keeps utility investors up at night. They're making billion-dollar bets on technology trends that are inherently uncertain. Governments are loosening environmental constraints based on demand forecasts that could be wrong.

What's rational for individual companies might be irrational collectively. OpenAI building a dedicated gas plant makes sense from a business perspective—it guarantees power supply for critical infrastructure. Meta expanding data center capacity makes sense if they believe AI will become core to their business. But collectively, if multiple companies do the same thing and AI demand plateaus, you end up with massive overcapacity.

There are some signs of slowing. Investment in AI startups has cooled after the initial gold rush. Some companies are pulling back on expansive AI capability goals. But data center construction is still accelerating. It takes 2-3 years for these decisions to manifest in actual shutdowns or slowdowns.

The policy implication is significant. We're potentially committing ourselves to fossil fuel infrastructure based on speculative demand. From a climate perspective, that's exactly backward. You should be conservative about fossil fuel buildout because of the long-term carbon implications.

Yet the political and economic pressure is to be aggressive. The FOMO (fear of missing out) is real. If the US doesn't build data center capacity, companies will build elsewhere. The jobs and tax revenue stay in other countries. The strategic advantage in AI goes to competitors.

It's a classic collective action problem. Individually rational decisions adding up to collectively irrational outcomes.

What Transition Technologies Are Missing

There are emerging technologies that could potentially solve parts of this puzzle, but they're not ready for scale yet.

Advanced nuclear designs—small modular reactors (SMRs)—could theoretically provide baseload power without carbon emissions. But they're not yet operational at commercial scale. The first deployed SMRs are probably 5-10 years away. Some companies are exploring SMR partnerships with data center operators, but the lead times are long and the technology unproven at scale.

Geothermal energy could be another option, particularly in regions with good geothermal resources. It provides reliable, baseload power without the carbon footprint of gas. But geothermal development is slow, and most good sites are far from data center hubs.

Hydrogen could theoretically replace natural gas in power plants, but green hydrogen production is currently energy-intensive and expensive. Using renewable power to create hydrogen to then burn for power is less efficient than just using the renewable power directly.

Grid modernization and smart management could help. If data centers could shift their power consumption based on when renewable energy is abundant, the equation changes. A data center that runs AI training jobs when wind is generating power and shifts to lower-intensity work when wind drops would reduce peak power requirements. But this requires AI systems capable of optimizing their own power usage, which isn't standard yet.

Waste heat recovery from data centers is another option that's underutilized. Data centers generate enormous amounts of low-grade heat. Some facilities are experimenting with using that heat to warm buildings or greenhouses in nearby areas. But this only works if you have industrial or agricultural users nearby, which isn't always the case.

The transition path that would actually solve this problem would involve:

- Massive expansion of renewable energy capacity (2-3x current levels)

- Aggressive battery storage deployment (enough to shift renewable energy across multiple hours)

- Flexibility in data center operations to shift workloads based on renewable availability

- Regional grid interconnections to move renewable power from generation-rich areas to consumption-heavy areas

- Strict limits on new fossil fuel capacity

But none of that is happening at scale. Instead, we're building gas plants because they're convenient.

Natural gas plants, even with lower CO2 emissions, can have a climate impact similar to coal plants due to methane leakage. Estimated data shows high leakage scenarios significantly offset CO2 benefits.

The Global Dimension: Where Else This is Happening

The AI data center boom and associated gas expansion isn't unique to the US. It's a global phenomenon, though the US and China are leading the buildout.

China is aggressively building data center capacity, particularly in inland regions with cheap land and abundant coal infrastructure. The irony is that China faces severe air quality issues from coal combustion, so there's some incentive to shift toward gas. But the buildout is happening regardless of environmental concerns.

The EU is in a different position. It committed more aggressively to climate targets than the US, and there's political pressure to maintain those commitments. But data center companies still want to build in Europe because of market access and talent. The result is a patchwork of regulations: some countries are approving gas plants, others are requiring renewable energy procurement, and some are restricting data center growth.

Japan is facing power constraints similar to the US. It's dealing with aging nuclear capacity that's gradually coming back online after the Fukushima shutdown. In the interim, gas is being used for baseload power. New data center development is pushing for more gas plants.

India is investing heavily in AI capacity, particularly for processing and inference at cheaper costs. Power infrastructure there is still developing, so data centers are often paired with renewable energy projects. But reliability concerns are pushing utilities toward gas as well.

The global pattern is consistent: where power is cheap and abundant (Texas, parts of China, parts of India), data centers cluster and drive new generation. Where power is constrained (EU, parts of Asia), data center growth is throttled by available power.

International climate negotiations are starting to reflect this tension. Countries that committed aggressively to decarbonization are finding it difficult to enforce those commitments when data center companies are looking for homes. There's a growing conversation about whether climate goals are realistic given the AI boom, or whether data center power demand needs to be actively limited through policy.

The Economic Calculus: Why Gas Wins Against Renewables

When you do the math, natural gas wins on most timelines for power generation for data centers. Not on lifetime cost, but on upfront cost and completion time.

A 500-megawatt gas plant costs approximately

A 500-megawatt solar farm costs approximately

Adding 500-megawatts of battery storage (enough for 4 hours of backup) costs approximately

Over a 30-year lifespan, the renewable project is cheaper because fuel costs are zero and operations costs are lower. But over a 10-year horizon, which matters for venture capital and startup mentality, gas is cheaper.

Data center operators are thinking in 5-10 year horizons for expansion. They want power available now, not in 5-10 years. That timeline preference drives them toward gas.

Utilities think in 30-year horizons because they're regulated utilities with long-term cost recovery models. But even for them, the capital cost of renewable-plus-storage is higher, and the operational complexity is greater. Gas plants are proven technology with known costs and predictable operations.

Long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) matter too. A company like Meta can sign a 15-year PPA with a utility guaranteeing payment for a certain amount of power. This revenue guarantee makes it attractive to build the plant, regardless of whether it's gas or renewable. But PPAs are standardized for gas plants. There's less institutional knowledge about renewable-plus-storage PPAs, creating an additional friction factor.

From a finance perspective, gas plants are easier to fund. Banks understand the technology, understand the risks, and can structure financing accordingly. Renewable-plus-storage projects are newer, more complex, and harder to finance. This funding gap contributes to the preference for gas.

Government incentives could tilt the equation. Tax credits for renewable energy buildout or penalties on fossil fuel plants could change the economics. But current policy is moving in the opposite direction—loosening fossil fuel regulations and maintaining renewable subsidies but not ramping them up enough to compete on timeline.

Stranded Assets: The Long-Term Risk

A stranded asset is infrastructure that becomes uneconomic before it reaches the end of its technical life. You build it expecting 30 years of productive use, but market conditions change and it becomes worthless after 10 years.

There's a real possibility that large amounts of the gas infrastructure being built for data centers ends up stranded. If AI demand doesn't materialize as expected, or if better alternatives emerge, these plants lose their revenue sources.

Utilities are insulated from some of this risk because they're regulated and can pass costs to ratepayers. But investors aren't. If a utility builds a gas plant expecting 30 years of revenue and the revenue dries up after 10 years, investors lose. This risk is slowly starting to be priced in, but not fully.

The climate transition also creates stranded asset risk. As we move toward decarbonization, gas plants face either retirement before their technical end-of-life or mandatory carbon pricing that makes them uneconomic. A plant built in 2026 expecting a 30-year lifespan could face mandatory retirement by 2040-2045 to meet climate goals.

This creates a weird incentive structure. Companies want to build now because environmental regulations are loose. But that means building assets with high stranded risk. It's a race to build before the rules tighten.

Historians in 2050 might look back at 2024-2026 as the period when we knowingly built infrastructure that we planned to retire prematurely. It would be a policy failure of epic proportions.

What makes it worse is that the stranded asset costs don't fall on the companies building the data centers. They fall on utilities, which pass them to ratepayers. Or they fall on climate advocates who get to say "I told you so" while the damage compounds.

From a pure economic perspective, this suggests overinvestment in gas infrastructure. The private benefits (data center operator gets cheap, reliable power) are captured, but the external costs (climate change, stranded assets, utility ratepayer burden) are socialized.

Policy Options and Why They're Unlikely

There are several policy interventions that could reshape this dynamic:

Carbon pricing: A tax or cap-and-trade system that makes the carbon cost of fossil fuels explicit. This would make gas plants more expensive and renewables more competitive. But carbon pricing is politically challenging and opposed by fossil fuel companies.

Renewable energy mandates for data centers: Require that new data centers be powered by a minimum percentage of renewable energy. This would force the private cost of renewable energy to be addressed. But it creates competitive disadvantages for US companies if other countries don't adopt similar rules.

Gas plant restrictions: Prohibit or restrict new gas plant approvals for new demand. This would require companies and utilities to figure out alternative power sources. But it would slow data center buildout and create geopolitical disadvantages if China can build data centers faster.

Massive renewable energy investment: Government builds and funds renewable energy projects specifically for data center power. This bypasses market inefficiencies. But it requires significant government spending and challenges the assumption that private markets allocate resources efficiently.

Grid modernization and storage: Federal investment in grid infrastructure and battery storage to handle intermittent renewable power. This removes the intermittency advantage of gas. But it's expensive and faces political opposition.

None of these are happening at scale. The current political momentum is opposite: deregulate fossil fuels, streamline permitting, reduce environmental oversight.

The reasons are understandable if not defensible. Political leaders see AI as critical to national competitiveness. They see China building data center capacity and fear being left behind. They see jobs and economic growth associated with data center development. And they face industry lobbying from both tech companies and fossil fuel companies, all aligned on the message that "we need to build fast."

Public opinion doesn't seem to be pushing back hard either. Data center impacts are diffused and slow. You don't immediately see climate damage from a new gas plant. Air quality degradation is gradual. And if the data centers create jobs locally, there's a constituency that supports the development.

The International Competitiveness Angle

One argument that keeps coming up is that the US "has to" build data centers and supporting infrastructure fast, or China will win the AI race.

This framing is strategically useful for defending fossil fuel buildout, but it oversimplifies the actual competition. China is building AI capacity aggressively, but it's facing similar power constraints. It's building coal and gas plants as well.

The US actually has advantages that should theoretically allow it to build renewable-powered data centers faster than China: better access to capital, more advanced renewable technology, stronger venture capital ecosystem, more developed grid infrastructure.

But the US isn't leveraging those advantages. Instead, it's competing on the basis of "we can get permits and build fossil fuel infrastructure faster." That's a race to the bottom in environmental standards, not a demonstration of economic capability.

There's also a question about what "winning the AI race" actually means. If it means capturing the most data center capacity, okay, maybe that's important. But if the broader economic value comes from AI algorithm development, software, and applications, then data center location and power source matter less. Google operates data centers globally and can balance them based on power availability.

The geopolitical framing is also worth questioning. Yes, if the US can't build data centers, investment will flow elsewhere. But that's true for any industry. It's not uniquely urgent for AI.

What might actually matter more is developing AI technology and capabilities that work efficiently. A company that figures out how to run advanced AI models on 10% less power has a bigger competitive advantage than one that has slightly cheaper power in Texas.

But that's a longer-term, harder-to-win competition. The faster-to-win strategy is "build the infrastructure first, figure out efficiency later." That's politically appealing in the short term.

What Companies Are Actually Doing

Not all companies are treating this the same way. There's actually variance in approaches, which is interesting.

Google has the most aggressive renewable energy procurement program. The company has contracted for gigawatts of wind and solar capacity and is building its own renewable generation in some cases. But it's still supplementing with grid power, which in many regions includes fossil fuels.

Meta is building data center capacity globally and signing PPAs for renewable energy where available, but also accepting gas power where necessary. The company seems to be optimizing for cost and speed rather than carbon footprint.

OpenAI is taking a novel approach with Stargate, investing in dedicated infrastructure including on-site gas generation. The company is essentially building its own power plant because it doesn't trust the grid to be reliable enough for its needs. This is a more vertically integrated model that's expensive but gives complete control.

Some companies are exploring power purchase agreements with a mix of renewable and gas components, trying to balance cost, reliability, and carbon footprint.

Smaller companies and startups are often forced to take whatever power is available. They're less able to negotiate dedicated renewable PPAs and more dependent on what the utility grid offers.

Microsoft has made some interesting moves, partnering with nuclear providers and exploring small modular reactors for data center power. The company seems to be taking a longer-term view and trying to invest in technologies that could provide reliable, zero-carbon power. But these investments won't pay off for 5-10 years.

What's notable is that none of the big tech companies are loudly opposing the gas plant buildout. They're happy to use available power sources. If gas plants are approved, they'll use them. If renewables are available, they'll use those. They're agnostic about the power source as long as it's reliable and reasonably priced.

This lack of opposition is strategically important. If major tech companies came out strongly against fossil fuel expansion and committed to zero-carbon data center operations with price premiums if necessary, it would be politically difficult to argue for gas. But they're not, because it would increase costs and slow expansion.

Future Scenarios: The Next Five Years

What's likely to happen from 2026-2030?

Scenario 1: The Current Trajectory Continues: Gas plants keep getting approved and built. Data center expansion accelerates. By 2030, the US has added 150-200 gigawatts of gas capacity, almost entirely driven by data center demand. This creates stranded asset risk if AI demand doesn't materialize, but also locks in carbon-intensive infrastructure for decades.

Scenario 2: The Constraints Kick In: Regional power grids become congested. Water stress becomes severe in key regions. Environmental opposition slows approvals. Data center expansion hits capacity constraints. Companies are forced to look at alternatives: renewable energy, power efficiency, or building in different locations. This would be painful for tech companies but better for climate goals.

Scenario 3: Technology Breakthroughs: Massive improvements in AI energy efficiency make current projections obsolete. Or advanced nuclear becomes deployable at scale faster than expected. Or grid storage technology improves dramatically and enables high-renewable systems. This would allow data center expansion without the fossil fuel buildout.

Scenario 4: Policy Reversal: A political change leads to stricter environmental regulations, carbon pricing, or renewable energy mandates. This would slow fossil fuel buildout and accelerate renewable investments. But it's unlikely in the current political environment.

Most Likely: We're seeing a hybrid. In some regions, gas plants continue getting approved (Texas, southeast). In others, opposition is slowing projects (California, some northeastern states). Data center growth continues but becomes more geographically dispersed as companies look for regions with available power. Some companies make serious renewable energy investments as a differentiator, but most continue taking whatever power is cheapest and fastest to develop.

The carbon trajectory is likely to be worse than current climate models assume because of this infrastructure buildout. Planning documents that assume emissions decline are probably wrong if this gas buildout happens as expected.

What Should Actually Happen

If we're serious about climate goals and also want to support data center growth (which seems to be the political consensus), here's what rational policy would look like:

- Treat data center power demand as a constraint, not a free pass for fossil fuel expansion

- Mandate that new data centers be powered by renewable energy, with options for carbon offsets if necessary but with higher costs as an incentive

- Invest heavily in grid modernization and battery storage to handle renewable integration

- Fast-track permitting for renewable energy projects, matching the speed of fossil fuel permitting

- Implement carbon pricing to make the climate cost of fossil fuels explicit

- Support R&D in energy efficiency for AI and next-generation power sources

- Plan for managed retirement of fossil fuel plants rather than just building new capacity

This would make data center expansion more expensive in the short term but would align economic incentives with climate goals.

But this isn't what's happening. Instead, we're taking the path of least resistance: building fossil fuel plants because the technology is known, the financing is established, and there's no political cost to overriding environmental concerns in the name of AI competitiveness.

It's a classic case of rational short-term decisions adding up to irrational long-term outcomes.

FAQ

Why do AI data centers need so much power?

AI data centers require enormous power because they run sophisticated neural networks with billions of parameters continuously. Training a large language model consumes millions of kilowatt-hours. Inference, where the model answers user queries, scales to millions of requests simultaneously, each requiring computational processing. A single hyperscale AI data center with tens of thousands of GPU chips can consume 50-100 megawatts continuously, equivalent to powering 80,000-100,000 homes.

Why is natural gas preferred over renewables for powering data centers?

Natural gas offers dispatchable power, meaning utilities can increase or decrease output based on demand. Solar and wind are intermittent and variable. While renewable energy is increasingly cost-competitive, it requires battery storage and complex grid management to provide 24/7 power. Gas plants can be built in 3-4 years, matching data center development timelines. Renewable projects with storage take longer and face more permitting complexity, making gas the faster option for companies prioritizing speed.

What are the climate impacts of this gas expansion?

Direct combustion of natural gas produces CO2. Additionally, methane leakage during extraction, processing, and transport creates significant greenhouse gas emissions because methane is 80-90 times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period. The total climate impact of natural gas infrastructure is often 30-50% worse than simple combustion calculations suggest. Building 150+ gigawatts of new gas capacity for data centers could increase global emissions by 0.3-0.5% annually through 2030, negating several years of climate progress.

Could renewable energy actually power data centers at scale?

Yes, but it requires additional infrastructure. Solar and wind could theoretically power data centers if paired with sufficient battery storage and grid connectivity. However, this requires overcoming technical challenges around grid management, significantly higher upfront capital investment, and longer permitting timelines. Some companies like Google are successfully using renewable power, but most combine renewables with grid power that often includes fossil fuels. A renewable-powered data center future is possible but requires policy support and investment that currently isn't being provided.

What are stranded assets in the context of data center power plants?

Stranded assets are infrastructure built with an expected 30-year lifespan that becomes economically unviable before its technical end-of-life. If AI demand doesn't grow as projected, or if regulations require plant retirement early to meet climate goals, gas plants built for data centers could become liabilities. A plant built in 2026 might be forced to retire by 2045 to meet net-zero targets, leaving decades of capital costs unrecovered. This creates risk for utilities and their investors.

What is methane leakage and why does it matter for natural gas?

Methane leakage refers to natural gas that escapes into the atmosphere during extraction, processing, transportation, and plant operations rather than being combusted. Studies show methane leakage is 1-3% in the US natural gas supply chain, sometimes higher. Because methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than CO2, this leakage significantly increases the climate impact of natural gas power compared to simple carbon calculations. Some energy analyses suggest methane leakage nearly offsets the climate benefits of using gas instead of coal.

How does this relate to the Paris Agreement climate goals?

The Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming by transitioning away from fossil fuels and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Building 150+ gigawatts of new fossil fuel infrastructure for data centers contradicts these commitments. These plants will still be operating in 2045-2050, creating pressure to either extend emissions timelines or force premature retirement. The buildout of gas infrastructure for data centers is essentially incompatible with Paris Agreement goals unless offset by equivalent emissions reductions elsewhere.

Are there alternatives to gas for data center power?

Several emerging alternatives exist but aren't yet ready for large-scale deployment. Small modular reactors (SMRs) could provide reliable, zero-carbon baseload power but won't be commercially available at scale for 5-10 years. Geothermal energy is location-dependent but promising in suitable regions. Advanced grid storage and smart energy management could enable high-renewable systems. Green hydrogen could theoretically replace natural gas, but production is currently too expensive and energy-intensive. The most viable near-term option is renewable energy paired with battery storage, requiring policy and investment changes to compete with gas on timeline.

What is the geopolitical significance of data center location and power sources?

The US and China are competing for dominance in AI capabilities. The US currently leads in data center capacity and AI development. Political leaders worry that if US data centers can't be built fast enough, companies will build in other countries, shifting AI development elsewhere. This creates pressure to approve infrastructure quickly, including fossil fuel plants. However, AI competitiveness depends more on technology, talent, and algorithms than on data center location. Overbuilding fossil fuel infrastructure in the name of geopolitical competition may not be necessary and locks in environmental costs that affect all countries.

What would it take to transition data center power to renewable energy at scale?

A large-scale renewable transition would require multiple policy changes: government investment in grid modernization and battery storage ($200-300 billion over 5 years), renewable energy procurement mandates for data centers, carbon pricing to make fossil fuel costs explicit, and fast-track permitting for renewable projects matching fossil fuel timelines. Some economists argue the US could meet all data center power demand from renewables by 2030 with a Manhattan Project-scale commitment. Currently, individual companies are making renewable investments, but it's not happening at the scale needed to eliminate fossil fuel buildout.

Final Thoughts: The Crossroads We're At

We're at a genuine crossroads. The AI boom is real, data center power demand is increasing dramatically, and something has to provide that power. The choice being made right now is fossil fuels, not because they're the only option, but because they're the fastest, most convenient, and have the most established institutional support.

This choice has consequences that will persist for decades. Gas plants built in 2026 will still be running in 2045. That timeline matters for climate goals. Every dollar spent on fossil fuel infrastructure is a dollar not spent on renewable alternatives. Every year of delay in transitioning to clean power makes the 2050 net-zero target harder to achieve.

But the political pressure is enormous. Companies want to build fast. Governments want the investment and jobs. Utilities want the guaranteed revenue. And there's genuine geopolitical concern about China's AI development creating urgency.

What's missing from this equation is a long-term view. We're optimizing for the next 3-5 years at the expense of the next 30 years. We're treating data center power demand as an exogenous constraint when it's actually something we can influence through efficiency improvements and technology choices.

The rational path forward would involve some combination of aggressive renewable energy investment, grid modernization, and data center efficiency improvements. It would be more expensive than building gas plants. It would take longer to implement. But it would actually move us toward climate goals rather than away from them.

Instead, we're doing the easy thing. And in 2050, when we look back at this period, it will probably be seen as a critical juncture where we made the wrong choice.

Key Takeaways

- Gas power plant development surged 31% globally in 2025, with the US surpassing China for the first time in new capacity additions

- More than one-third of new US gas capacity is explicitly planned for AI data center power, representing a fundamental shift in energy infrastructure investment

- AI data centers consume enormous amounts of power (50-100 MW continuously per facility), making them comparable to mid-sized cities in energy demands

- Methane leakage in natural gas supply chains increases actual climate impact by 30-50% above combustion emissions alone, making climate cost calculations incomplete

- Current policy trajectory favors speed and geopolitical competitiveness over climate goals, potentially locking in fossil fuel infrastructure that conflicts with 2050 net-zero targets

Related Articles

- Data Centers & The Natural Gas Boom: AI's Hidden Energy Crisis [2025]

- EPA Closes Generator Loopholes: AI Data Center Expansion Hits Federal Wall [2025]

- Redwood Materials $425M Series E: Google's Bet on AI Energy Storage [2025]

- Google's Project Genie AI World Generator: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Tesla's Energy Storage Business Is Booming [2025]

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

![AI Data Centers Drive Historic Gas Power Surge [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-data-centers-drive-historic-gas-power-surge-2025/image-1-1769726380354.jpg)