Introduction: The Unexpected Energy Explosion Behind AI

Something wild happened while everyone was focused on AI capabilities and chatbot conversations. The power grid is quietly undergoing one of the most dramatic reshuffles in modern history, and natural gas is having a renaissance nobody anticipated.

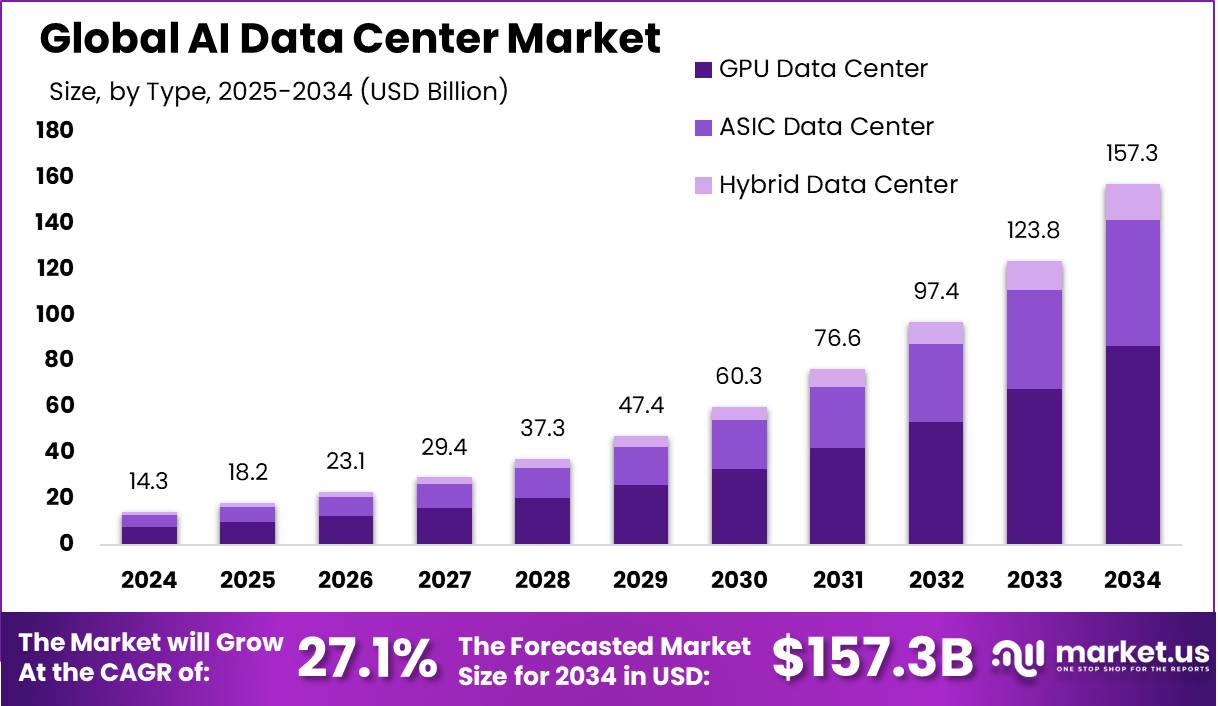

Here's the thing: data centers powering artificial intelligence systems consume staggering amounts of electricity. We're talking about infrastructure that requires constant, reliable power at scales most people can't visualize. And that demand exploded. Hard.

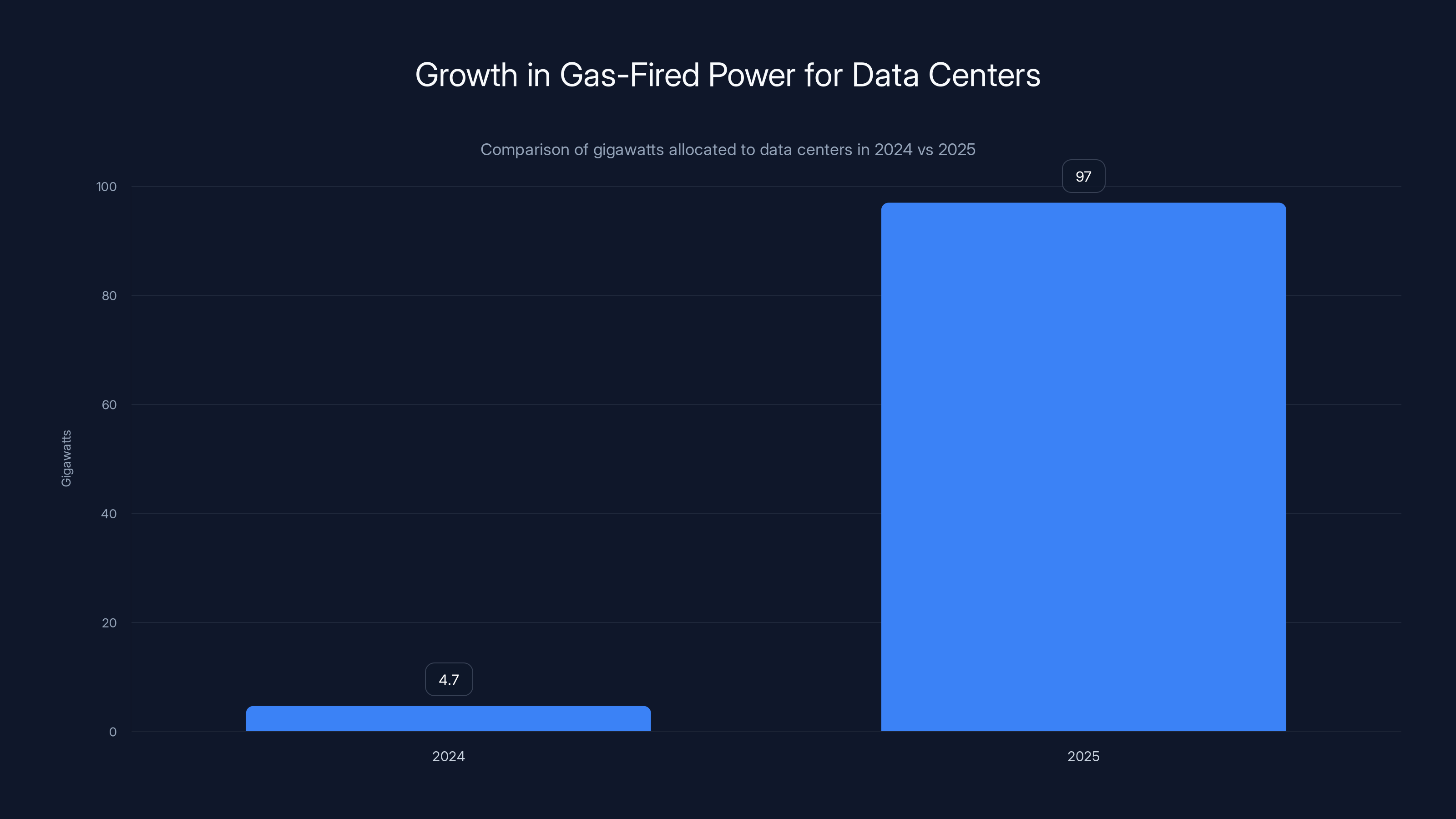

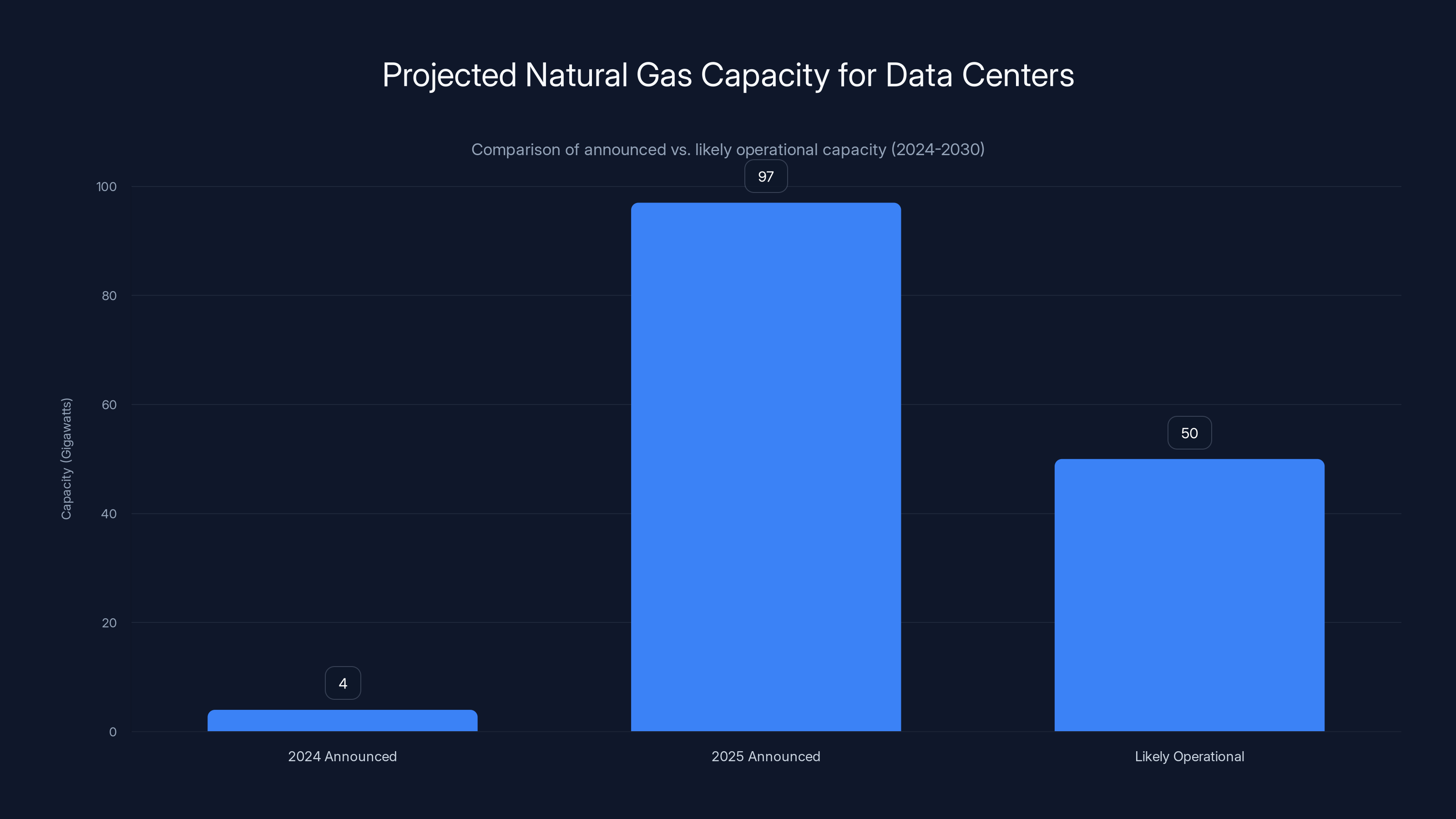

In early 2024, there were roughly 4 gigawatts of natural gas-fired power explicitly earmarked for data center projects in development across the United States. By 2025, that number jumped to 97 gigawatts. That's not a 10 percent increase or even a doubling. That's roughly 25 times more gas infrastructure being planned in a single year.

To put this in perspective, 1 gigawatt can power somewhere between 750,000 to 1 million US homes depending on regional energy consumption patterns. So we're talking about the difference between powering a small state and planning infrastructure that could power a dozen of them. Except this power isn't going to homes. It's going to servers running machine learning models.

This matters because natural gas isn't some magical clean energy solution. When you burn it for electricity, you're releasing carbon dioxide. When you extract it from the ground, methane leaks escape into the atmosphere where they're roughly 80 times more potent than CO2 at trapping heat over a 20-year period. And right now, in 2025, regulations designed to catch those leaks are being rolled back.

What makes this story genuinely unsettling isn't just the environmental angle. It's that we're watching the energy industry make massive, decades-long infrastructure commitments based on AI demand projections that could be wildly wrong. It's also that data center operators are so desperate for power that they're propping up coal plants and building their own gas turbines on-site because connecting to existing power grids takes years.

This article digs into the data, the math, the political context, and what it actually means for your electricity bill, climate policy, and the future of AI development.

TL; DR

- Gas projects explicitly linked to data centers jumped from 4 GW (2024) to 97 GW (2025) - nearly a 25x increase in one year

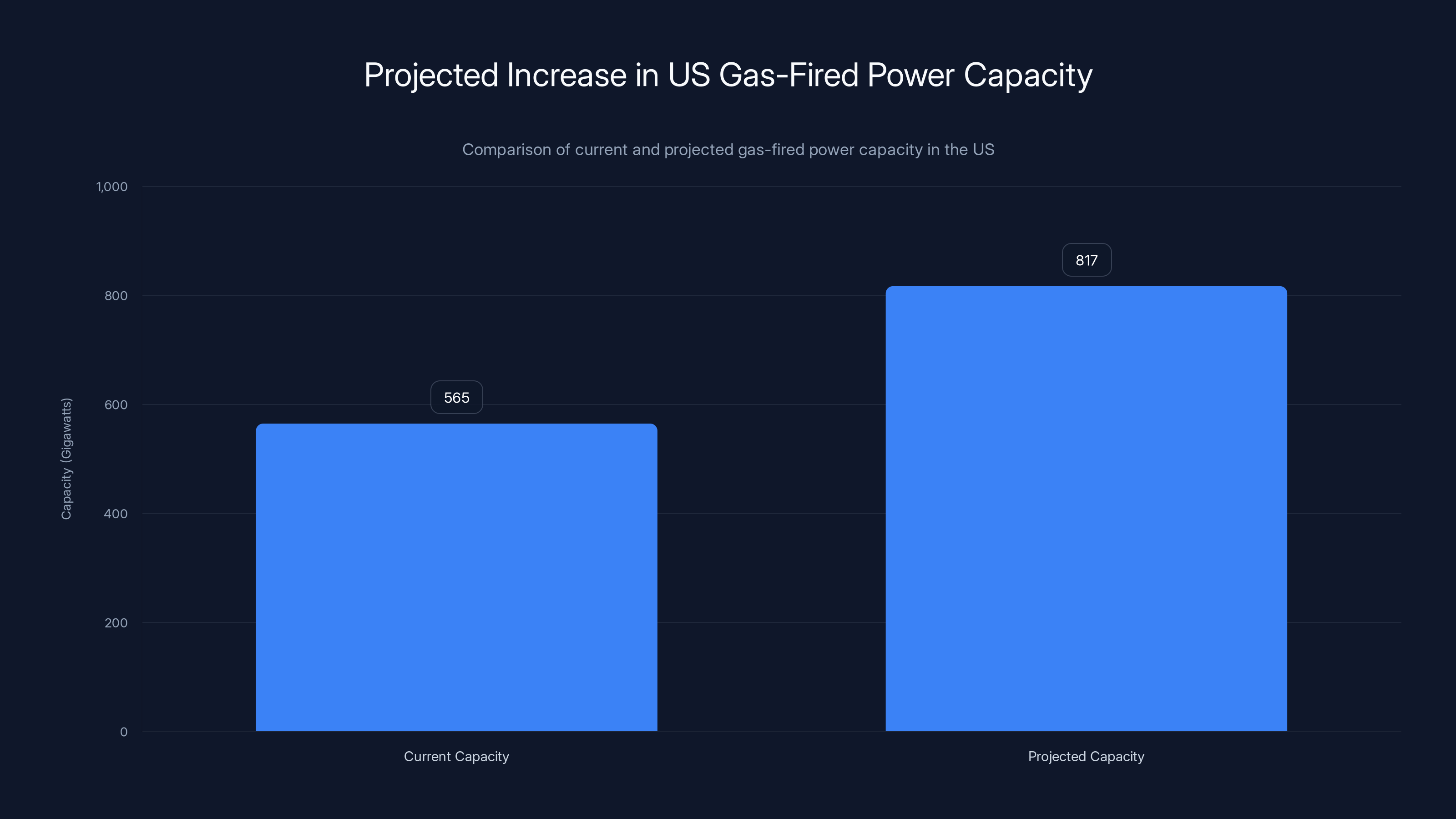

- Building all planned projects would increase the US gas fleet by almost 50%, adding 252 GW to existing 565 GW capacity

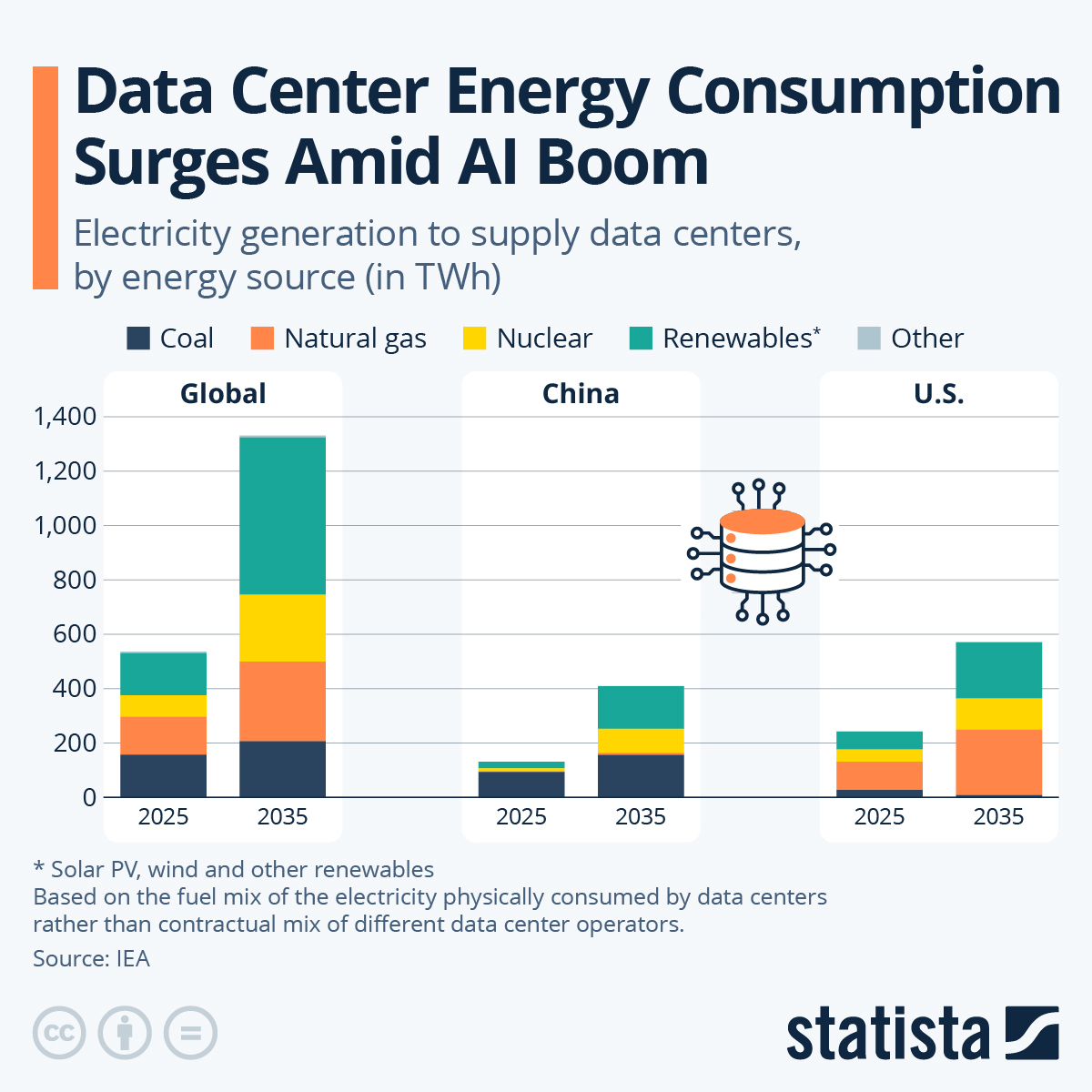

- Data centers have nearly tripled demand for gas-fired power in the US over just two years

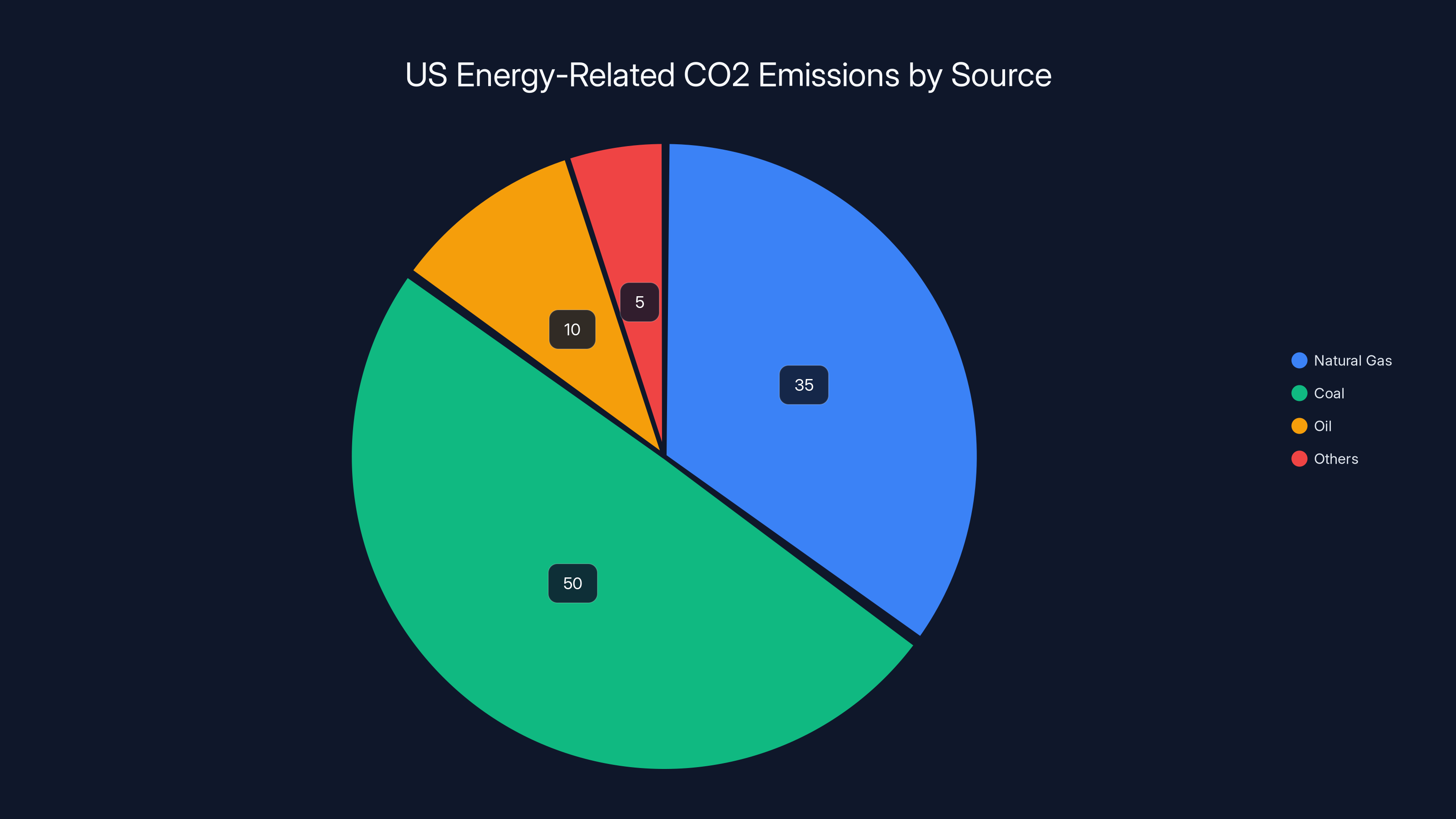

- Natural gas still releases significant CO2 (about 35% of US energy-related emissions in 2022) plus methane leaks during extraction

- Most projects lack actual turbine manufacturers, suggesting many won't be built, but even 30-40% completion would massively reshape US energy

The US gas-fired power capacity is projected to increase by 45%, from 565 GW to 817 GW, if all planned data center projects are completed. Estimated data.

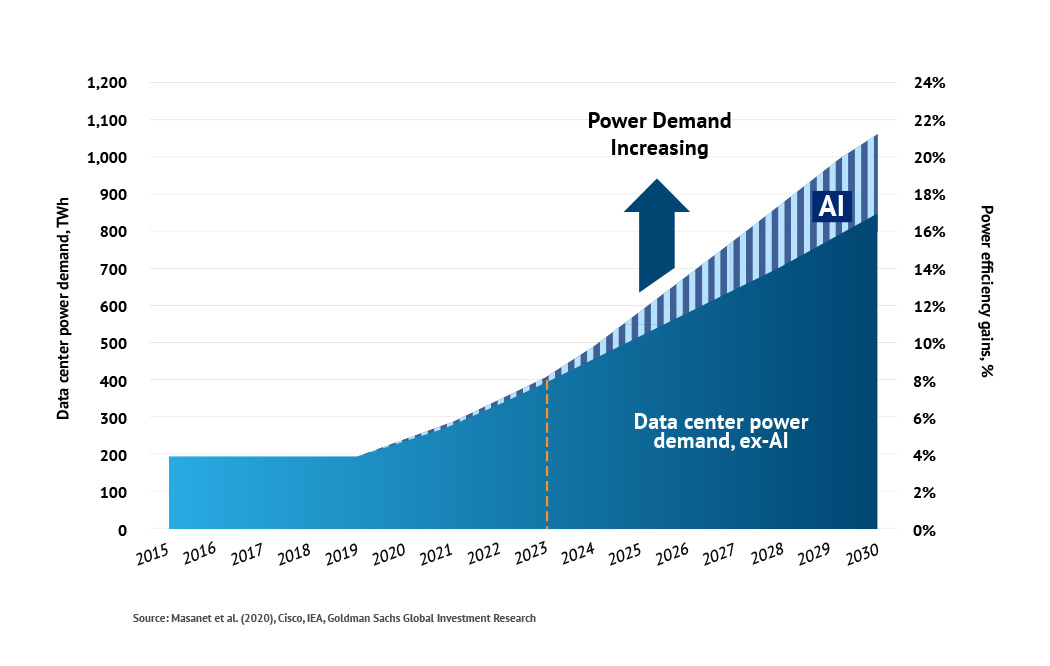

How We Got Here: The AI Power Consumption Problem

Let's start with the basic physics. Training large language models requires passing massive amounts of data through neural networks with billions or trillions of parameters. That's computation. Lots of it. Sustained, continuous computation that requires reliable, always-on power.

When you run Chat GPT or Claude or any large AI model, you're not just getting a quick response. Behind the scenes, that response is powered by server farms running 24/7, with cooling systems fighting to keep processors from melting, and redundancy systems ensuring nothing goes down. A single data center can consume 10 to 100 megawatts continuously, depending on its size and the workloads it runs.

Now multiply that by hundreds of data centers, all built or being planned within the last 3-4 years. Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Meta, and a dozen other companies are building massive facilities. Some are purpose-built for AI. Others are being converted from older uses. The growth rate is almost incomprehensible if you stop to think about it.

The problem is that data centers need reliable power. Solar and wind are great, but they're intermittent. A solar array doesn't help you at 2 AM. Wind turbines don't spin every day. Battery storage exists, but it's expensive at the scale data centers need. So operators look for sources that can provide consistent, on-demand power 24/7/365.

Natural gas checks that box. Fire it up when you need it, keep it running constantly, no intermittency problems. It's also significantly cleaner than coal. Efficiency has improved. And there's existing infrastructure and expertise for running gas plants.

That logic made sense five years ago when data center expansion was measured and predictable. It doesn't quite work the same way when demand explodes from essentially zero to 97 gigawatts in 12 months.

The Numbers: Understanding the 25x Growth

Let's break down exactly what the data shows, because the scale is almost hard to grasp.

In 2024, Global Energy Monitor tracked approximately 85 gigawatts of gas-fired power in development across the United States. Of that, about 4.7 gigawatts were explicitly earmarked for data centers in state filings, public announcements, and regulatory documents.

That seemed like a lot at the time. A few billion dollars in gas infrastructure specifically for AI.

Then 2025 hit. Suddenly the pipeline expanded to nearly 250 gigawatts total. And here's the shocking part: roughly 97 gigawatts of that new demand is explicitly linked to data center projects.

That's not 25 times the amount from 2024 because the existing amount doubled and quadrupled. It's 25 times larger because the entire landscape fundamentally shifted. Companies that were cautiously evaluating data center expansion suddenly committed to massive builds. Venture capital started flowing. Tech firms announced billion-dollar infrastructure plans.

To understand what 97 gigawatts means, consider this formula:

For a typical US home consuming about 10,500 kilowatt-hours annually (roughly 0.9 k W average draw), 97 gigawatts of continuous power could supply approximately 108 million homes. That's one-third of the entire US population worth of power going to data centers for AI systems.

But here's where it gets more complicated. Not all of those 97 gigawatts are actually under construction. Many are in early planning stages. Some are duplicative (multiple companies filed plans for the same sites with different utilities, inflating the total). And many won't actually be built.

Global Energy Monitor research suggests that two-thirds of the gas turbine projects they tracked globally don't yet have manufacturers assigned to build the turbines. There's a global shortage of turbine manufacturing capacity. Supply chain constraints could push out timelines by years or make some projects uneconomical.

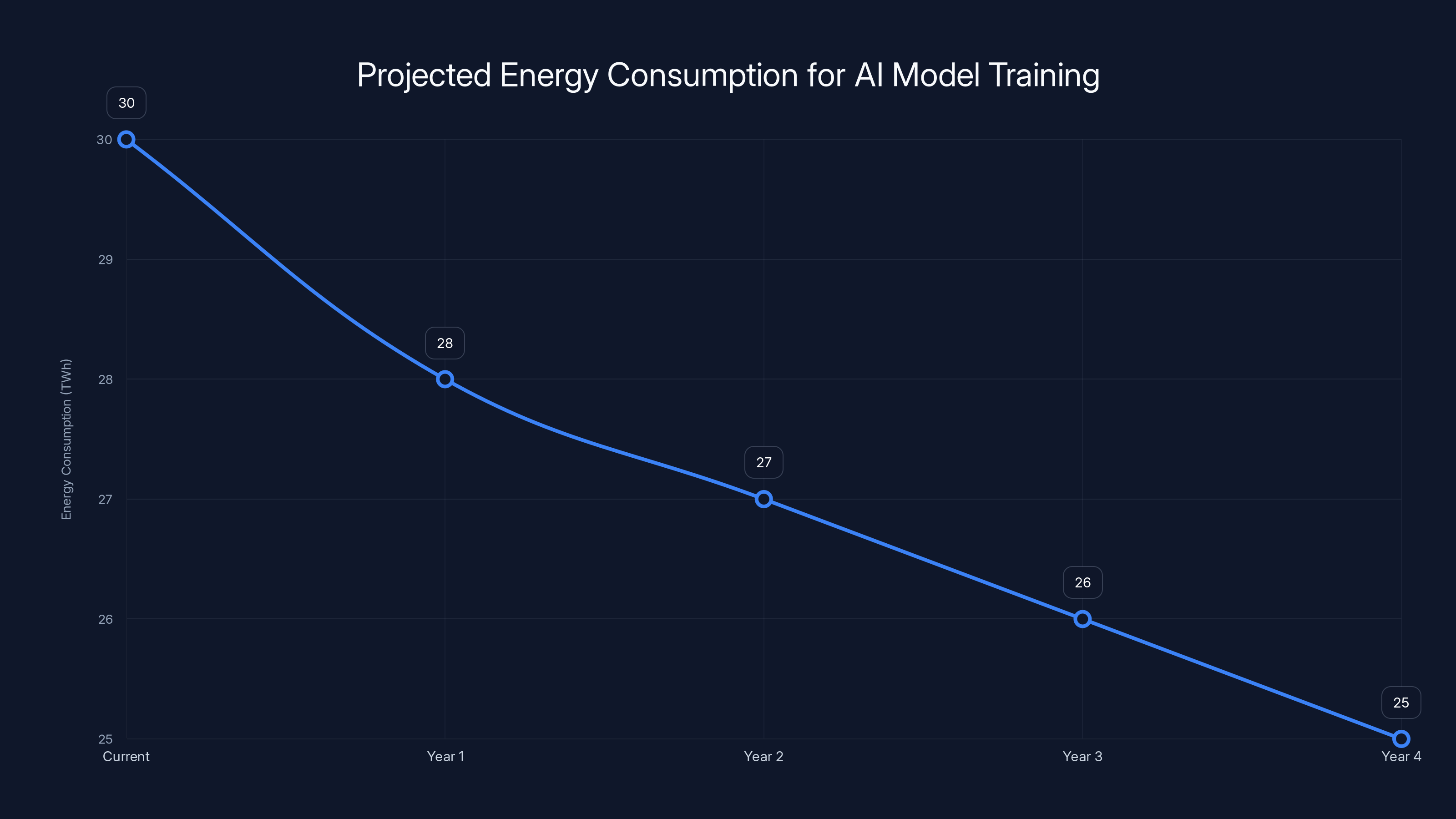

Projected energy consumption for AI model training shows a gradual decrease due to improved hardware efficiency, despite increasing model sizes. Estimated data.

The Current Grid and What 50% Growth Actually Means

The United States currently operates approximately 565 gigawatts of gas-fired power capacity. That's the infrastructure that can spin up at any moment to meet demand.

If every single data center project in the pipeline gets built, it would add 252 gigawatts of new gas capacity. That's a 45 percent increase to the entire gas fleet. In other words, nearly half again as much capacity as currently exists, built in the next 5-10 years.

For context, the entire US electrical grid has roughly 1,200 gigawatts of total capacity across all sources (coal, nuclear, hydro, wind, solar, and gas). A 45 percent increase to just the gas portion would fundamentally reshape how electricity is generated and distributed.

What makes this even more stark is the timeline. Normally, major infrastructure changes happen over 20-30 year periods. We plan, build environmental impact assessments, permit, construct, and bring online gradually. This is happening in compressed timeframes with massive financial pressure.

Some of this expansion makes economic sense. Gas plants are relatively fast to build compared to nuclear facilities. They have lower upfront capital requirements. But building this much infrastructure requires:

- Environmental permits and air quality assessments

- Natural gas pipeline expansion or new pipeline construction

- Interconnection to the electrical grid (which itself has bottlenecks)

- Water for cooling systems

- Labor to build and operate

- Financing arrangements

Each of those steps introduces delays and costs. When you have 200+ projects all competing for the same resources simultaneously, you create bottlenecks.

Carbon Emissions: The True Cost of Gas Power

Natural gas gets promoted as the "cleaner" fossil fuel option. It's not entirely wrong. When you burn natural gas, you produce roughly 50 percent less CO2 than coal and generate almost zero particulate matter or sulfur dioxide. From an air quality perspective, gas is genuinely better.

But let's not pretend it's clean.

About 35 percent of all US energy-related carbon dioxide emissions come from burning natural gas for electricity, heat, and other industrial processes. That's tens of hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 annually. If you add 252 gigawatts of new gas capacity and run it at typical capacity factors (usually 30-50 percent for gas plants), you're looking at an enormous increase in emissions.

Here's the math:

A typical gas plant emits roughly 500 metric tons of CO2 per gigawatt-hour of electricity generated. If 97 gigawatts of new data center gas plants run at even a conservative 40 percent capacity factor, you're looking at roughly:

That's equivalent to the annual emissions of approximately 36 million cars. From just the data center gas plants that have been explicitly announced.

But CO2 is only part of the story. The bigger concern for climate scientists is methane.

Methane: The Overlooked Climate Wildcard

Natural gas is predominantly methane (CH4). When you extract it from the ground, transport it through pipelines, process it, and eventually burn it in power plants, some of it escapes into the atmosphere. Not a huge percentage at any given point in the process, but the cumulative leakage across the entire supply chain adds up significantly.

Here's why this matters: methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than CO2. Over a 100-year period, methane is roughly 25-28 times more effective at trapping heat. Over a 20-year period, it's approximately 80-85 times more potent.

Climate scientists care a lot about the 20-year number because we're in a crucial window where limiting warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius is still technically possible if we act aggressively. Preventing methane leaks now has an outsized impact on whether we hit those targets.

The US oil and gas industry is responsible for roughly a third of all global methane emissions. We're the largest natural gas producer in the world. Methane leakage happens at multiple points: during extraction, at processing facilities, in pipeline networks, and at distribution points.

Historically, regulations required operators to monitor and control these leaks. But in 2025, those regulations are being rolled back. The Obama-era methane emissions rules faced renewed challenges under regulatory review. Standards that required leak detection and repair got postponed. Some monitoring requirements got eliminated.

So we have a situation where:

- Demand for natural gas is exploding due to data centers

- More gas extraction means more potential methane leaks

- Regulatory frameworks designed to minimize those leaks are being weakened

This is genuinely concerning from a climate perspective.

The demand for gas-fired power for data centers surged from 4.7 gigawatts in 2024 to 97 gigawatts in 2025, marking a significant shift in infrastructure investment.

Data Center Power Options: Why Gas Wins by Default

You might reasonably ask: why aren't all these data centers just powered by renewable energy? If solar and wind are getting cheaper, why build gas plants?

The answer isn't about cost or capability. It's about reliability and timing.

A solar array in Arizona can be incredibly cheap per megawatt. But it only generates power during daylight. A wind farm in Texas is efficient, but it generates based on weather patterns, not demand. For a data center running AI workloads 24/7, you need power every single hour.

The most robust solution would be a mix of renewables plus substantial battery storage. But battery technology, while improving, is still expensive at gigawatt-scale for multi-hour durations. A 1-gigawatt data center running on renewables plus batteries would need enough storage to cover nighttime hours and calm-wind periods. That battery cost could add billions to a project.

Nuclear would be perfect for this use case. It provides reliable, always-on, low-carbon power. But nuclear plants take 10-15 years to build and cost $10-20 billion each. Tech companies planning data centers want infrastructure online in 3-5 years.

Hydroelectric is great but geographically limited. There's only so much water flowing through rivers suitable for power generation.

So gas becomes the default. It's fast to build (18-24 months), has lower capital cost than nuclear, existing infrastructure exists in many regions, and operators understand how to run it.

Some data center companies are trying to solve this differently. Google and others are building on-site solar arrays and battery systems for their data centers. Microsoft explored underwater data centers (which benefit from sea cooling). Amazon is investing in wind farms to pair with its facilities.

But these approaches are the exception, not the rule. Most operators take the path of least resistance: get a gas turbine, connect it to the plant, start generating power.

What's interesting is that some data center developers are actually building on-site gas turbines rather than connecting to the broader grid. Why? Because connecting to the existing electrical grid in many regions now takes years of interconnection studies and waiting for grid upgrades. There are physical bottlenecks. Too much demand, not enough transmission capacity.

So instead of waiting, companies build their own dedicated power sources. This is actually in some ways more efficient (less transmission loss), but it also means more distributed gas infrastructure across the country rather than centralized generation.

The Coal Plant Subplot: Natural Gas's Unexpected Beneficiary

Here's an ironic twist: the natural gas boom is actually extending the life of coal plants.

Coal-fired power plants are dying in the United States. They're dirty, expensive to operate, and face increasingly strict regulations. Most utilities have announced plans to retire their coal fleets over the next decade. This makes economic and environmental sense.

But here's the thing: when grid demand suddenly spikes because of data centers, utilities need more power generation capacity fast. Building new coal plants doesn't make sense (they're becoming uneconomical). Nuclear takes too long. Renewables need storage solutions.

Natural gas fills the gap. But so does extending the life of existing coal plants just a bit longer. Some utilities have recently pushed back coal retirement dates, kept plants online that were scheduled to close, and even brought offline plants back into service.

From a climate perspective, this is genuinely bad. Coal is roughly twice as carbon-intensive as natural gas. A coal plant that was supposed to retire in 2026 but now operates until 2030 will emit hundreds of millions of tons of additional CO2.

So the data center energy crunch is indirectly extending coal's life. Natural gas captures most of the new demand, but coal gets a stay of execution.

This dynamic reveals something important about energy transitions: when you have rapid demand spikes, the entire energy system can lurch in unexpected directions. The cleanest, cheapest, most efficient options don't always win. The options that can come online fastest do.

What Actually Gets Built: The Reality Check

Here's the critical question that doesn't get asked enough: how much of this 97-gigawatt pipeline will actually be built?

The honest answer is probably somewhere between 25 and 60 percent. Maybe less.

Why? Several factors:

Manufacturing Bottlenecks: Global Energy Monitor found that two-thirds of all gas turbine projects globally don't yet have manufacturers assigned. There's a worldwide shortage of gas turbine manufacturing capacity. Companies like GE, Siemens, and others can only produce so many units per year. At current capacity, it would take 15-20 years to manufacture all the turbines needed for the US pipeline alone.

Financing Uncertainties: Large infrastructure projects need financing. That typically comes from banks, bonds, or corporate capital. Interest rates, regulatory uncertainty, and shifts in AI demand forecasts could easily cause investors to pull back. If an AI company announces slower-than-expected demand growth or faces competitive pressures, those data center projects get cancelled or downsized.

Permitting and Environmental Reviews: Each new power plant needs environmental permits. Air quality assessments. Water impact studies. Local opposition. These processes take time and can kill projects. Some projects that look economical today might not survive 3-4 years of permitting delays.

Grid Interconnection Bottlenecks: Even if you build a gas plant, connecting it to the electrical grid takes time. The transmission and distribution system has physical limitations. Too many projects competing for limited interconnection capacity means some get delayed or cancelled.

Demand Uncertainty: Here's the big one. Nobody actually knows what the real demand for AI compute will be in 5-10 years. Current projections are based on growth rates from the past 2-3 years. But AI demand could plateau, could shift to more efficient models that need less power, or could hit resource constraints that no one anticipated.

Many data center operators are hedging their bets. Multiple companies might file plans for gas plants to power the same facility, knowing that only one will actually be built. This inflates the pipeline numbers.

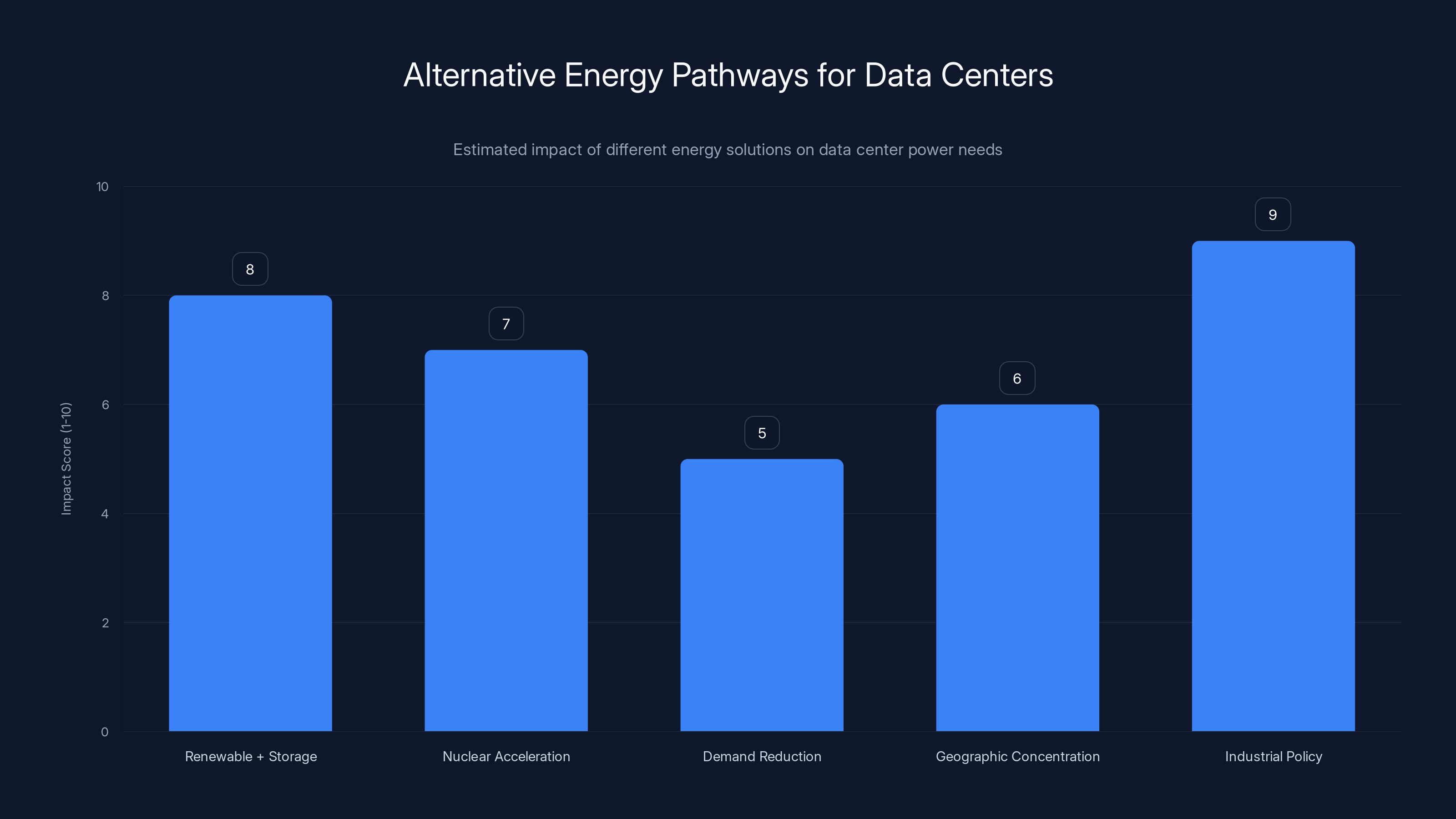

Estimated data suggests that industrial policy and renewable buildout are the most impactful pathways for addressing data center power needs, while demand reduction and geographic concentration offer moderate benefits.

Regional Impacts: Where the Gas Is Heading

The gas boom isn't distributed evenly. Certain regions are becoming data center hotspots, which means natural gas infrastructure is concentrated in specific areas.

Virginia, North Carolina, and Texas are seeing disproportionate growth. Virginia already hosts a massive data center cluster in Northern Virginia (near Washington DC) that powers much of the East Coast internet infrastructure. Now that region is planning major new gas capacity specifically for AI facilities.

Texas is attractive because of existing gas infrastructure, relatively business-friendly regulations, and available land. Companies are building data centers in Dallas, Austin, and the surrounding region.

California has been adding data center capacity too, though some projections face opposition from environmental groups and grid operators concerned about peak summer demand.

Each region brings different considerations:

Virginia: Existing gas infrastructure is robust. Environmental concerns about methane leaks from additional extraction. Grid capacity is a limiting factor in some areas.

Texas: Abundant gas supplies. Existing expertise and workforce. Heat management challenges (cooling data centers in Texas summers requires massive water and power)

California: Existing data center clusters create agglomeration benefits. Environmental concerns are stronger. Water availability is a real constraint.

Other regions: Less obvious hotspots are also seeing growth. Georgia, Illinois, Ohio, and even some Midwest states have data center announcements.

The regional concentration matters because it shapes local environmental impacts, water stress, and grid stability. A single region that suddenly gets 10-15 new gigawatts of gas plants will face coordination challenges, environmental impacts, and potential supply bottlenecks.

The Broader Energy System Impact

Zoom out and consider what this means for the entire US electrical system.

The grid is actually several interconnected systems managed by regional operators. The Eastern Grid, Western Grid, and Texas Grid operate with varying degrees of coordination. Adding massive new capacity to any of these systems requires careful planning, new transmission lines, and upgrades to existing infrastructure.

Data center demand growth is happening so fast that grid operators are struggling to keep up. Interconnection queues are backed up for years. Transmission system upgrades that would normally take 5-8 years are being rushed, which introduces risks and costs.

The grid also needs to balance supply and demand constantly. With more gas plants coming online, the grid becomes slightly more stable (gas can ramp up and down faster than coal or nuclear). But it also becomes more fossil fuel dependent. If we're serious about decarbonization, adding 250 gigawatts of gas capacity is moving in the wrong direction.

Part of the challenge is that grid planning happened on old assumptions. Models built 10-15 years ago didn't account for massive AI-driven data center clustering. They didn't anticipate this level of demand concentration.

So grid operators are playing catch-up, making reactive decisions rather than proactive ones. This leads to suboptimal solutions like on-site gas turbines rather than coordinated renewables-plus-storage systems.

The Efficiency Question: Will AI Models Get More Efficient?

Here's a counterargument to all this doom-and-gloom energy talk: what if AI models get dramatically more efficient?

There's legitimate reason to think this might happen. Machine learning is a relatively young field. Early neural networks were wildly inefficient. Improvements in algorithms, hardware, and training methods have reduced training costs significantly.

Some of the leading AI researchers are working on efficiency improvements. Mixture of Experts (Mo E) architectures use fewer parameters per inference. Quantization reduces precision requirements. Distillation transfers knowledge from large models to smaller ones. Pruning removes unnecessary connections.

If AI models become 50 percent more efficient, that cuts the energy requirements in half. The 97-gigawatt pipeline becomes a 50-gigawatt need. Still massive, but more manageable.

Some projections show that efficiency improvements could offset 25-40 percent of the expected growth in data center power consumption.

But here's the catch: those efficiency gains might just enable more AI model training and deployment. It's classic rebound effect. As things get cheaper and more efficient, usage expands to fill the capacity. So maybe we get more efficient AI, but also more of it, resulting in similar or higher total energy consumption.

The history of computing suggests this is likely. Moore's Law made semiconductors cheaper and more powerful. The result wasn't fewer computers using the same energy. It was vastly more computing happening overall.

Announced natural gas capacity for data centers is projected to increase from 4 GW in 2024 to 97 GW in 2025. However, due to various constraints, only 40-60% of this capacity is expected to become operational, estimated at 50 GW. Estimated data.

Policy Context: Regulation and the Trump Administration

Timing matters a lot here. The explosion in data center gas projects is happening at the exact moment when environmental regulations are being rolled back.

In 2025, the Trump administration is pursuing policies that reduce oversight of fossil fuel infrastructure. This includes extending deadlines for methane emissions rules and rolling back proposed regulations on power plant emissions.

These regulatory changes don't cause the data center boom, but they create conditions where companies feel more comfortable making long-term investments in gas infrastructure. If you're a utility or independent power producer considering a $2 billion natural gas plant, the regulatory environment matters enormously. Will the rules change in 5 years? Will new carbon taxes emerge? Will methane regulations get stricter?

Weaker regulatory expectations = more comfortable investment decisions.

Conversely, states and municipalities are pursuing stricter standards in some cases. California has been trying to phase out natural gas. Some Northeast states are pushing clean energy standards. There's real tension between federal deregulation and state-level climate policies.

This creates a patchwork environment where gas infrastructure is simultaneously expanding aggressively (in less-regulated states) and facing opposition (in more climate-focused states).

From a pure climate perspective, this is terrible timing. We should be accelerating renewable energy deployment and decarbonization. Instead, we're locking in decades of natural gas infrastructure that will emit billions of tons of CO2.

But from a corporate perspective, if you're a tech company needing power for data centers now, the regulatory environment is actually quite favorable. Fewer obstacles, faster permitting, and policymakers who are supportive of industrial energy use.

The Cost of Inaction: What If We Do Nothing

Let's play out a scenario where most of these gas plants get built.

- 250 new gigawatts of gas capacity comes online over 5-8 years

- Operating at typical capacity factors (40 percent), that's roughly 170 million metric tons of additional CO2 annually

- Plus methane leakage from extraction and operations

- Forty-year lifespan for most plants means 6+ billion tons of cumulative CO2 from infrastructure built in 2025-2030

To put that in perspective, the entire US needs to reach net-zero emissions by around 2050 to stay on track for climate goals. Every new fossil fuel plant built commits us to decades of emissions when we should be reducing them.

This isn't just about climate math though. It's about resource allocation. Every dollar spent on new gas infrastructure is a dollar not spent on renewable energy, battery storage, grid modernization, or demand reduction.

It's also about lock-in. Once a gas plant is built and financed, utilities and operators have strong incentives to run it for decades. Stranded assets are politically difficult. You end up with infrastructure that becomes economically obsolete but keeps running because the alternative is admitting your investment was bad.

The companies building these plants right now aren't stupid. They see a real short-term need for power and a real opportunity to build it. But the long-term implications—both for climate and potentially for stranded assets if energy storage gets cheaper than running old gas plants—aren't being fully accounted for.

The Efficiency Math: Power Consumption Per AI Operation

Let's get specific about the efficiency question.

Training a large language model like GPT-4 required somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 graphics processing units (GPUs) running for weeks. That's roughly 10-50 terawatt-hours of electricity. For a single model training run.

Now, that number might decrease with better algorithms and hardware. It might increase as models get larger. But it demonstrates the sheer scale.

A rough equation for AI compute requirements:

If you double the size of a model (parameters), energy roughly doubles. If you train on twice as much data, energy doubles. If hardware efficiency improves by 50 percent, energy drops by 50 percent.

The key variable we can't predict is what researchers will prioritize: bigger models, better performance, or lower cost? All three aren't compatible. Pick any two.

If the industry prioritizes cost and efficiency, we might see models that are smaller but more capable. If it prioritizes capability, we'll see larger models that use more energy.

Current trends suggest the industry is pursuing both bigger models and better efficiency simultaneously, which means net energy demand still grows, just not as fast as naively scaling would suggest.

Natural gas accounts for 35% of US energy-related CO2 emissions, highlighting its significant role despite being cleaner than coal. Estimated data.

Alternative Pathways: What Should Happen Instead

If we're trying to solve the data center power problem without massive new gas infrastructure, what are the actual alternatives?

Massive Renewable + Storage Buildout: The obvious answer is solar, wind, and batteries. The challenge is capital cost and timeline. A gigawatt of solar plus enough batteries for 12-hour storage costs roughly $2-3 billion. That's expensive, but doable. The limiting factor is manufacturing capacity for batteries and solar panels, plus grid infrastructure to distribute the power.

Nuclear Acceleration: Small modular reactors (SMRs) are being developed by companies like Nu Scale and others. They're not quite ready for deployment but could potentially start operating in data centers by 2027-2030. They're expensive but provide reliable, always-on, clean power. If the industry made a serious commitment to SMRs, you could start deploying them as data centers come online.

Demand Reduction: This is politically unpopular, but running less AI would require less power. Maybe models get smaller. Maybe companies are more selective about deploying AI. Maybe efficiency improvements reduce compute needed per query. This alone won't solve it, but even a 20 percent reduction in demand would change the energy picture.

Geographic Concentration: Building data centers in locations with abundant clean power (near hydroelectric facilities, in areas with strong wind resources, in regions with geothermal potential) would reduce the need for new fossil fuel infrastructure. This requires coordinating corporate location decisions with energy resources, not optimal but possible.

Industrial Policy: The government could subsidize nuclear, renewables, or storage at data centers, making clean power cheaper than gas. This is what other countries are doing. Virtually no cost-effective data center is choosing gas because it's cheaper than renewables. They're choosing it because it's faster and more reliable. Remove those constraints through policy, and the calculus changes.

None of these are silver bullets, but a combination could probably handle most of the demand without 250 gigawatts of new gas capacity.

The fact that it's not happening reflects real constraints (cost, timeline, supply chains, regulatory complexity) but also political priorities. Right now, building fast with existing technology wins over building optimal.

The Data Center Companies' Perspective

It's worth understanding why tech companies are making the decisions they are. They're not evil actors trying to destroy the climate. They're operating under real constraints and real business logic.

An AI company like Open AI or Anthropic needs compute to train models and serve users. That compute is expensive. They need power, and they need it to be reliable. Downtime costs millions in lost revenue and user trust.

A cloud provider like Amazon Web Services (AWS) is selling compute services to customers. They need to guarantee uptime and performance. That means reliable, always-on power.

From a corporate decision-making perspective:

- Building on-site gas turbines is fast and reliable (18-24 months)

- Buying renewable energy from existing providers is cheap but might not have enough capacity

- Building custom renewable + storage systems is expensive and time-consuming

- Waiting for grid upgrades takes years of interconnection studies

The rational choice from a business perspective is gas. It's also the worst choice from a climate perspective.

This is a coordination problem. Individual rational choices aggregate into an irrational outcome at the systems level. You see this all the time in economics: what's individually optimal isn't collectively optimal.

Solving it requires collective action: policy that makes alternatives cheaper, regulations that make gas more expensive or slow, or coordinated corporate commitment to cleaner options.

None of those are happening at sufficient scale right now.

The Methane Leakage Rate: Unknown and Crucial

Here's something genuinely important that doesn't get discussed enough: we don't actually know the real methane leakage rate from US oil and gas operations.

The EPA estimates it's around 2-3 percent of total production. Some independent studies suggest it might be 4-7 percent or even higher. There's huge uncertainty.

If it's 2 percent, the climate impact of methane from additional gas extraction is bad but manageable. If it's 7 percent, it's genuinely catastrophic.

Difference between EPA estimates and independent studies likely comes from several factors: EPA studies might rely on self-reported industry data, independent studies might better detect small leaks, facilities might have gotten better at preventing leaks in studied locations, or some facility types might leak much more than others.

This matters because the climate impact of natural gas relative to coal depends heavily on actual leakage rates. If leakage is low, gas is clearly better than coal. If it's high, gas might actually be worse.

The Biden administration funded more monitoring to get better data. Trump administration policies have rolled back some of that monitoring. So we're actually going backward in understanding our own emissions.

This is frustrating from a policy perspective. You can't optimize solutions when you don't understand the problem.

Stranded Assets and Long-Term Risk

Here's something that should worry investors and utilities: what happens to a 40-year gas plant if battery costs drop by 70 percent in the next 15 years?

Battery prices have been falling exponentially. A decade ago, batteries cost

At those prices, a data center powered entirely by renewables plus batteries becomes cheaper than running an old gas plant. The gas plant becomes a stranded asset. An investment that made sense in 2025 but looks economically idiotic by 2040.

History is full of these examples: coal plants becoming stranded as natural gas got cheaper, video rental stores becoming obsolete as streaming arrived, et cetera.

Naturally, utilities will fight hard to keep running gas plants even if they're uneconomical, because shareholders expect returns on their investments. You get regulatory battles, special rates that let operators recover costs, and political pressure to keep plants running.

But eventually, the math wins. Uneconomical infrastructure gets shut down. The question is whether that happens gracefully (by design, with workers retrained and communities supported) or messily (abruptly, with plant closures and economic dislocation).

Building massive new gas capacity right now is betting that gas remains competitively priced with renewables for the next 40 years. That's a bet I wouldn't take.

Timeline Pressures: Why Everything Is Accelerated

One unusual aspect of the data center boom is how compressed the timeline is.

Normally, a major power plant project takes 5-8 years from approval to operation. This includes design, permitting, financing, construction, and commissioning. Environmental reviews alone can take 2-3 years.

Data center operators are demanding projects in 2-3 years. Some are even trying for 18-24 months.

This creates pressure to cut corners: streamlined permitting, fast-track environmental reviews, compressed construction schedules. It also drives up costs (accelerated schedules always cost more) and increases risks (you're more likely to have construction problems when rushing).

It also means you get less time to optimize. A gas plant designed in 6 months is probably less efficient than one designed in 18 months. A construction process that's rushed is more likely to have problems that require expensive fixes later.

From the companies' perspective, speed matters more than optimization because being online 6 months late in a competitive AI market might mean losing that entire market opportunity.

This timeline pressure also explains why renewables plus storage don't win more often. These systems take time to plan and optimize. Gas plants are a proven, off-the-shelf solution that can be deployed fast.

International Context: How Other Countries Are Responding

The US approach of building massive gas infrastructure isn't universal.

Several European countries with similar tech industries and similar power constraints are pursuing different strategies:

Denmark: Has been building data centers alongside massive offshore wind farms. They've explicitly chosen a "no new gas plants" policy and are subsidizing renewable energy for data center clusters.

France: Leverages abundant nuclear power to attract data centers. Companies like Google and Meta are building facilities there, knowing they get clean baseload power.

Germany: Struggling with this exact problem. They have lots of data center demand but less nuclear than France and less offshore wind than Denmark. They're seeing similar pressure to build gas infrastructure, though with stronger political opposition than the US.

Sweden: Has abundant hydroelectric and nuclear power, making it an attractive location for data centers without major new fossil fuel infrastructure.

The contrast is instructive. Countries with strong policy commitment to renewables and/or nuclear are able to handle data center growth cleanly. Countries without that commitment end up with gas infrastructure.

The US has the technological capacity to do what these countries are doing. We have vast wind resources, abundant solar potential, and the ability to build nuclear reactors. We're choosing gas because it's administratively easier and politically convenient.

That's a policy choice, not an inevitable outcome.

Forecasting the Reality: What Will Probably Happen

Let me make a prediction about what actually happens with the 97-gigawatt pipeline:

Most likely scenario: About 40-60 percent of announced projects actually get built. That means roughly 40-60 additional gigawatts of gas capacity coming online over the next 5-8 years. It's still a massive expansion, but not the full doom scenario.

Why this much? Manufacturing constraints will limit turbine supply. Permitting delays will push out timelines. Some projects will be cancelled when financing gets difficult. But strong demand and supportive regulatory environment will keep many projects moving forward.

The 2027 reckoning: By 2027-2028, we'll have concrete data on whether AI demand is really as massive as current projections or if it's stabilizing. If it's stabilizing, many projects will be cancelled. If it's continuing to grow, projects will accelerate.

Efficiency improvements: AI models will probably get somewhat more efficient, reducing energy per unit of capability by maybe 30-40 percent from 2025 levels. This helps but doesn't reverse course.

Political changes: Unless climate becomes a much higher political priority, regulations will remain relatively weak. Carbon pricing is unlikely in the US. Maybe some states implement stricter standards, creating regional variation.

Battery revolution: Battery costs will continue falling. By 2030-2032, renewables plus storage will become genuinely cheaper than running gas plants. At that point, the case for new gas plants disappears, but by then, much of the infrastructure is already built.

Stranded asset problem: Some of the gas infrastructure built in 2025-2028 will become economically obsolete by 2035-2040. Political battles will ensue about who bears the cost.

Net result: The US gets additional gas capacity but probably not the full 250 gigawatts of announced projects. Emissions increase but not catastrophically. The opportunity to solve this problem cleanly through policy is mostly missed. By 2035, we're wishing we'd made different choices, but infrastructure is locked in for another 15-20 years.

The Role of Energy Automation in This Challenge

Here's an interesting angle: what if data centers could be smarter about how they use power?

Imagine if data centers could shift computational loads based on power availability. Run more compute during hours when renewable energy is abundant. Run less during peak demand hours. Shift model training to times when wind is strongest. Adjust data transfers to times when solar is maximized.

This kind of sophisticated power optimization could reduce peak demand and better utilize available renewable energy. It's technically possible but requires automation infrastructure.

Platforms that can orchestrate workloads across time periods and locations, manage power consumption intelligently, and coordinate with grid operators could substantially improve the efficiency of the energy system.

Some cloud providers are already experimenting with this. But it's not standard practice. Most data centers just consume power whenever they need it, without much thought to broader grid optimization.

If the industry invested in automation for energy-aware computing, it could probably reduce actual peak demand by 20-30 percent while still delivering the same computational capability. That could change the entire infrastructure picture.

Tools like Runable, which automate workflow orchestration, point toward a broader future where computation itself becomes more intelligent about resource consumption. Imagine if data center operations were managed by AI systems that optimized for both performance and energy efficiency. It's certainly possible; it's just not currently a priority.

Use Case: Automate data center operational workflows to track and optimize power consumption patterns, shifting computational loads to periods of peak renewable energy generation.

Try Runable For Free

Conclusion: The Reckoning We're Avoiding

The data center gas boom represents a classic energy transition problem: massive short-term demand for power meets insufficient long-term climate policy.

Companies have every rational incentive to build gas infrastructure fast. It's proven, reliable, and available. Regulators have given them the green light. Utilities see a profitable business opportunity. Investors are comfortable with the risk profile.

But collectively, we're making a choice to lock in fossil fuel infrastructure for the next 40 years, at exactly the moment we should be decarbonizing the energy system.

This isn't inevitable. Other countries show you can handle data center growth with renewables, nuclear, or both. The US has the resources and technological capability to do the same. We're choosing not to, primarily because it's politically easier.

The hard truth is that 250 gigawatts of new gas capacity won't all get built, but not because we solved the problem. It won't get built because supply constraints, financing difficulties, and eventual regulatory shifts will prevent it. Some fraction of the announced capacity will become reality, and we'll be dealing with the climate and economic consequences for decades.

The opportunity to get this right—to build data center capacity powered by renewables and next-generation nuclear—is closing. Within 2-3 years, most of the major gas infrastructure will be under construction. After that point, reversing course becomes politically and economically much harder.

What happens in the next 18-24 months will determine the energy landscape for the next 40 years. Right now, we're not making that choice consciously or well. We're letting infrastructure decisions made by individual companies aggregate into a systems-level lock-in of fossil fuels.

That's not a prediction I'm happy about, but it's the path we're on.

FAQ

What exactly is driving the spike in natural gas demand for data centers?

Artificial intelligence models require enormous amounts of continuous computing power. Training large language models and serving millions of user queries simultaneously demands reliable, always-on electricity. Data centers provide that compute, and they've exploded in growth over the past 2-3 years as AI companies compete to deploy larger, more capable models. Each new facility needs power, and natural gas became the default choice because it can be built quickly and reliably.

How much more natural gas infrastructure are we actually building?

About 97 gigawatts of new gas capacity was explicitly linked to data centers in 2025 planning documents, compared to just 4 gigawatts in 2024. That's nearly a 25x increase in announced projects. However, many of these won't actually be built. Manufacturing constraints, permitting delays, and financing difficulties will likely reduce the actual build-out to 40-60 percent of announced capacity, meaning roughly 40-60 additional gigawatts will likely become operational over the next 5-8 years.

Why don't data centers just use renewable energy?

Renewables like solar and wind are intermittent—they only generate power during specific conditions. Data centers need reliable power 24/7. The best solution would be renewables plus large-scale battery storage, but battery systems at gigawatt scales are still expensive and require significant manufacturing capacity that doesn't currently exist. Natural gas can be built quickly, provides reliable power on demand, and uses existing supply infrastructure. From a pure business decision perspective, it's the path of least resistance even if it's suboptimal from a climate perspective.

What's the difference between CO2 and methane emissions from natural gas?

Burning natural gas for electricity releases carbon dioxide (CO2), which is the primary driver of long-term climate change. But methane (the main component of natural gas) is also a potent greenhouse gas. When you extract, transport, and process natural gas, some methane leaks into the atmosphere. Methane is about 80 times more potent than CO2 at trapping heat over a 20-year period. Climate scientists consider reducing methane leaks crucial for short-term climate goals, but current US regulations on methane emissions are being weakened rather than strengthened.

Could efficiency improvements in AI models reduce the need for all this power?

Yes, it's possible. Machine learning algorithms are becoming more efficient, and researchers are developing techniques to reduce training energy requirements. However, history suggests that efficiency gains typically lead to expanded usage—you build more AI systems and train larger models because it becomes cheaper. So efficiency improvements might slow the energy growth rate, but probably won't reverse it. Better efficiency might reduce required capacity from 97 gigawatts to 60-70 gigawatts, but that's still a massive expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure.

What are other countries doing about this problem?

European countries with similar data center growth are pursuing different strategies. Denmark built data centers alongside offshore wind farms. France leverages abundant nuclear power to attract tech companies. Sweden uses hydroelectric and nuclear resources. The pattern is clear: countries with strong renewable and nuclear infrastructure can handle data center growth without massive new fossil fuel plants. The US has the technical capacity to do this too but lacks the policy commitment.

Will all these gas plants actually get built?

Probably not. Two-thirds of the planned gas turbine projects globally don't yet have manufacturers assigned to build the equipment. There's a worldwide shortage of turbine manufacturing capacity. Additionally, permitting takes years, financing can fall through, and if AI demand growth slows, projects will be cancelled. My estimate is that 40-60 percent of announced projects will actually become operational, still representing a massive expansion but not quite the full 250-gigawatt increase that sounds scary in headlines.

How does this affect electricity prices?

More gas capacity could eventually increase electricity supply and potentially lower prices, though other factors matter too (fuel costs, transmission constraints, demand fluctuations). However, the real cost isn't reflected in your electricity bill—it's reflected in climate impact. Emissions are externalities that aren't priced into the market. From a climate-adjusted perspective, natural gas is far more expensive than cleaner alternatives, but that cost isn't borne by the companies building the plants.

Is there any good news in this situation?

Yes, actually. Battery costs are falling exponentially and should drop by 70 percent or more over the next decade. At those prices, renewables plus storage will be cheaper than running old gas plants. The gas infrastructure being built now could become economically obsolete faster than expected. Additionally, some companies are experimenting with on-site solar, nuclear, and other solutions, proving alternatives are possible. The 18-24 month window to change course is closing, but it hasn't closed entirely. Policy changes prioritizing clean energy for data centers could still shift the trajectory.

What would it take to power data centers without massive new gas infrastructure?

Three things: (1) Accelerated deployment of renewables, especially solar and wind in data center regions; (2) Large-scale battery storage to handle intermittency; (3) Some combination of nuclear power (either traditional plants or next-generation small modular reactors) providing baseload clean energy. None of these are impossible. The problem is that executing all three requires policy commitment, coordinated investment, and regulatory support. Currently, we're choosing the easy path (gas) rather than the optimal one.

Related Articles

System will auto-generate related articles based on shared tags and topics.

Key Takeaways

- Gas projects for data centers exploded 25x from 4 GW (2024) to 97 GW (2025), though many won't be built due to manufacturing and permitting constraints

- Adding all planned capacity would increase US gas fleet by 45%, raising 169+ million metric tons of additional CO2 annually plus methane leakage concerns

- Natural gas is faster to build (18-24 months) than renewables or nuclear, making it the default choice despite climate costs and long-term stranded asset risks

- Methane leakage from natural gas extraction is 80x more potent than CO2 over 20 years, and current regulatory roll-backs weaken emissions controls

- Battery costs are falling exponentially and could drop 70% by 2035, potentially making new gas plants economically obsolete within 15-20 years

Related Articles

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

- Redwood Materials $425M Series E: Google's Bet on AI Energy Storage [2025]

- Tesla's $2B xAI Investment: What It Means for AI and Robotics [2025]

- Moltbot AI Assistant: The Future of Desktop Automation (And Why You Should Be Careful) [2025]

- Chrome's Gemini Side Panel: AI Agents, Multitasking & Nano [2025]

- Amazon's 16,000 Job Cuts: What It Means for Tech [2025]

![Data Centers & The Natural Gas Boom: AI's Hidden Energy Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/data-centers-the-natural-gas-boom-ai-s-hidden-energy-crisis-/image-1-1769647050163.jpg)