430 Tbps Fiber Optic Speed Record: What It Means for 7G [2025]

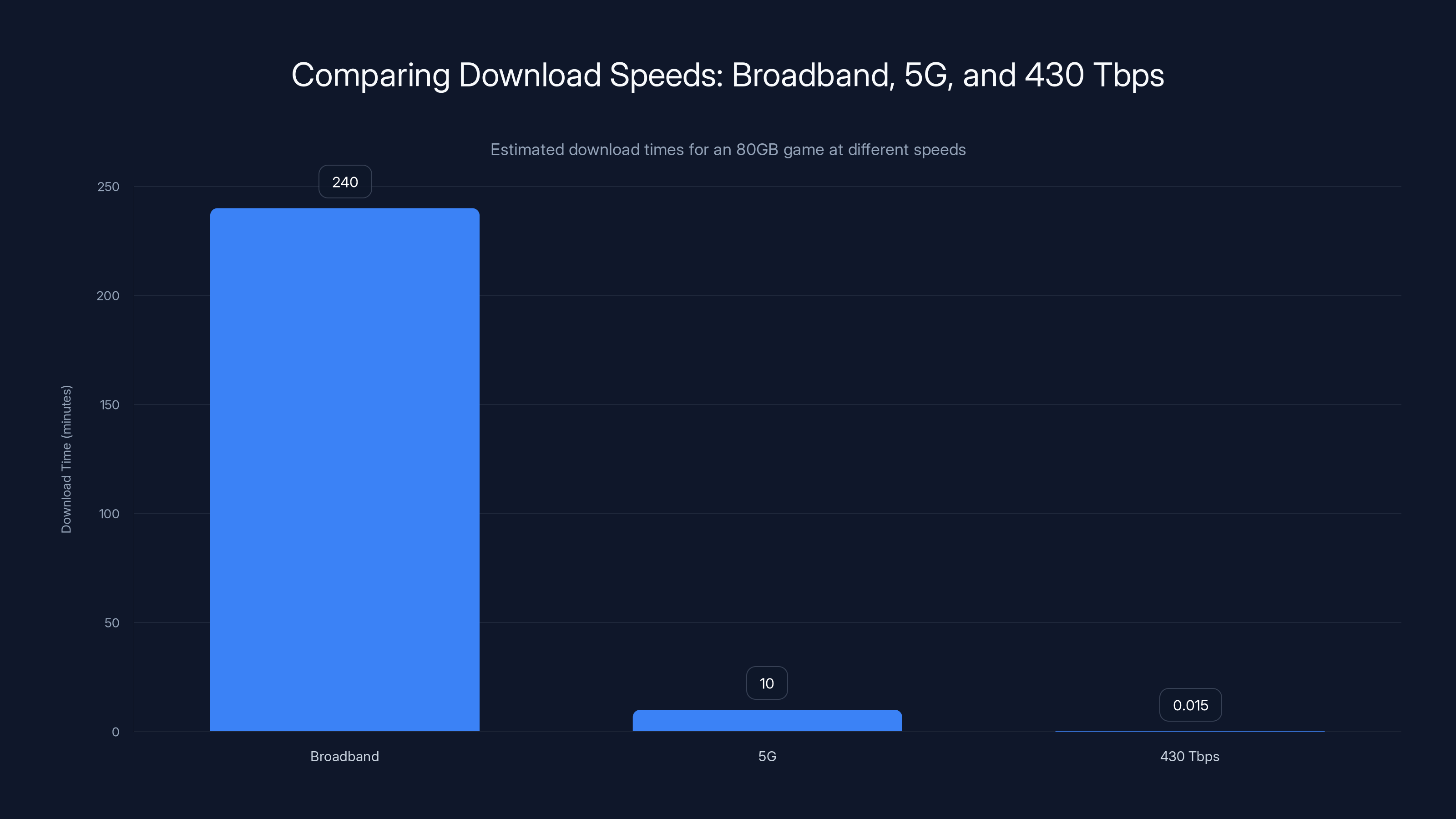

Picture this: you're downloading an 80-gigabyte game. At normal broadband speeds, you're waiting hours. At 5G speeds, it's maybe 10 minutes. But at 430 terabits per second? You'd have it done before your coffee gets cold.

That's not science fiction anymore. It's what researchers from Japan's National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) and the UK's Aston University just pulled off in a laboratory setting. They transmitted data at 430 Tbps using standard telecom fiber optic cables. Not experimental cables. Not new infrastructure. The same stuff already buried in the ground worldwide, as reported by TechRadar.

Here's what makes this legitimately interesting: the breakthrough wasn't about inventing something new. It was about discovering that what we already have is way more powerful than we realized. Think of it like finding out your old car's engine can handle twice the fuel grade you've been using.

The research team published their findings at the 51st European Conference on Optical Communication in Denmark, demonstrating that conventional optical fiber networks have massive untapped capacity sitting there, waiting to be exploited. This matters because upgrading global internet infrastructure takes decades and billions of dollars. If we can squeeze more performance from what exists, we don't have to wait.

But here's the nuance nobody really talks about: breaking speed records in a laboratory is one thing. Actually deploying this at scale, across continents, through complicated network architecture, while keeping costs reasonable and the system stable? That's a completely different challenge. Still, this research points to something real about the future of connectivity, whether we're talking about 7G wireless or the next generation of fiber networks.

Let's dig into what actually happened, why it matters, and what it means for how you'll access the internet in a few years.

TL; DR

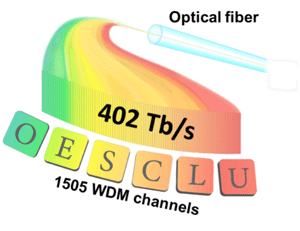

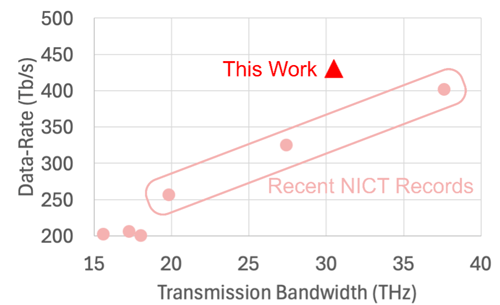

- Record-breaking transmission: NICT achieved 430 Tbps over standard single-mode fiber, surpassing their previous 402 Tbps record.

- Existing infrastructure advantage: The breakthrough uses widely deployed cables already in place globally, no new physical infrastructure required.

- 20% efficiency gain: The team transmitted data using nearly 20% less bandwidth than previous approaches through improved spectral efficiency.

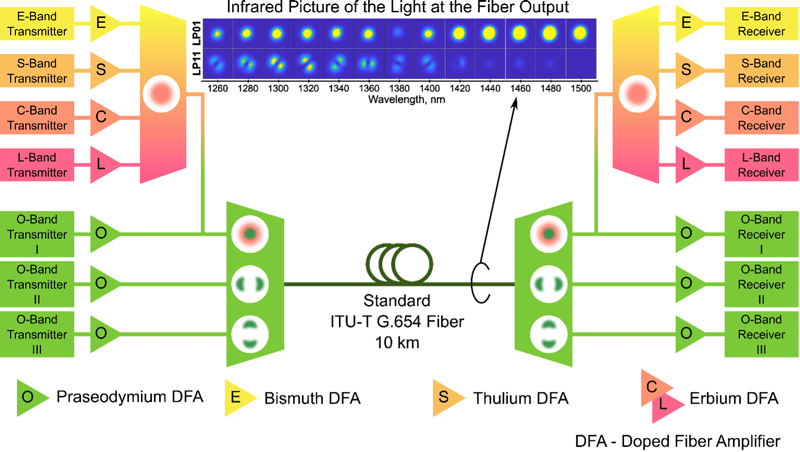

- Multiple mode transmission: Data travels simultaneously in parallel modes within the O-band and ESCL frequency ranges.

- 7G research implications: Laboratory breakthroughs like this establish feasibility for future wireless standards that will depend on fiber backbone capacity.

- Bottom line: Your ISP's cables are probably capable of delivering speeds 1000x faster than current service plans.

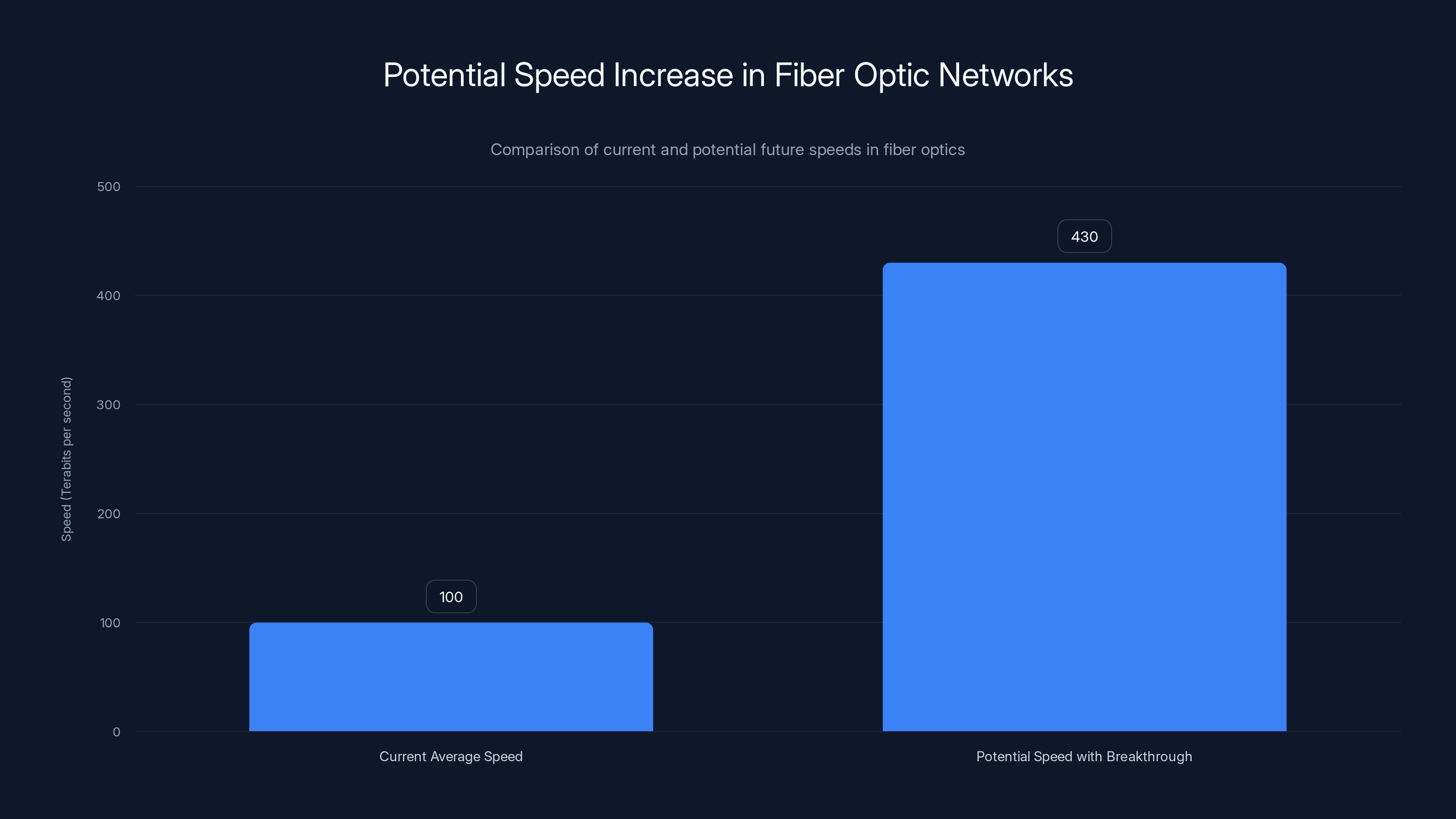

The current record of 430 Tbps is a 7% improvement over the previous record of 402 Tbps, achieved using standard single-mode fiber with 20% less bandwidth.

The Breakthrough: Understanding 430 Terabits Per Second

First, let's get the number in perspective. A terabit is one trillion bits. 430 terabits per second means the researchers moved 430 trillion individual data units in a single second. To put that in actual terms: if you had gigabit-per-second internet (which is already considered incredibly fast), you'd need 430,000 gigabit connections running simultaneously to match this transmission rate.

The previous record from the same team stood at 402 Tbps. So this isn't a revolutionary leap (it's about a 7% improvement). But the way they achieved it matters more than the raw number.

Instead of using specialized, custom-built fiber cables, the NICT team used standard single-mode fiber. This is the same fiber deployed across continents by telecommunications companies. It's the cable carrying your internet data right now. There are billions of kilometers of this stuff already installed globally, sitting in trenches and under oceans.

The old approach to setting speed records typically required either incredibly expensive specialized fiber or dramatically increased bandwidth consumption. This breakthrough did the opposite. It achieved higher speeds while using approximately 20% less overall transmission bandwidth. That's efficiency improvement, not just raw speed.

How Multiple Modes Changed the Game

Here's where the technical weeds get interesting. Standard single-mode fiber is designed to carry data in one specific way: a single electromagnetic mode traveling down the fiber. Think of it like a highway with one lane. It's efficient, proven, and reliable.

But the fiber itself can actually support more than one mode simultaneously. The catch is that when multiple modes travel together, they tend to interfere with each other like overlapping ripples in a pond. Engineers avoid this in standard deployments because the interference creates noise and errors.

The NICT team figured out how to send three different modes simultaneously while keeping them separated enough to avoid problematic interference. They used wavelengths below the traditional cutoff point that standard fiber was originally designed to ignore.

Think of it as discovering hidden lanes on that highway. The road was always capable of supporting them, but nobody knew how to make them work without causing crashes.

They transmitted data simultaneously in the O-band and the ESCL (Extended Short Cutoff) bands. The fundamental mode operated in one band while the higher-order modes operated in another. This parallel transmission boosted capacity without requiring wider bandwidth overall.

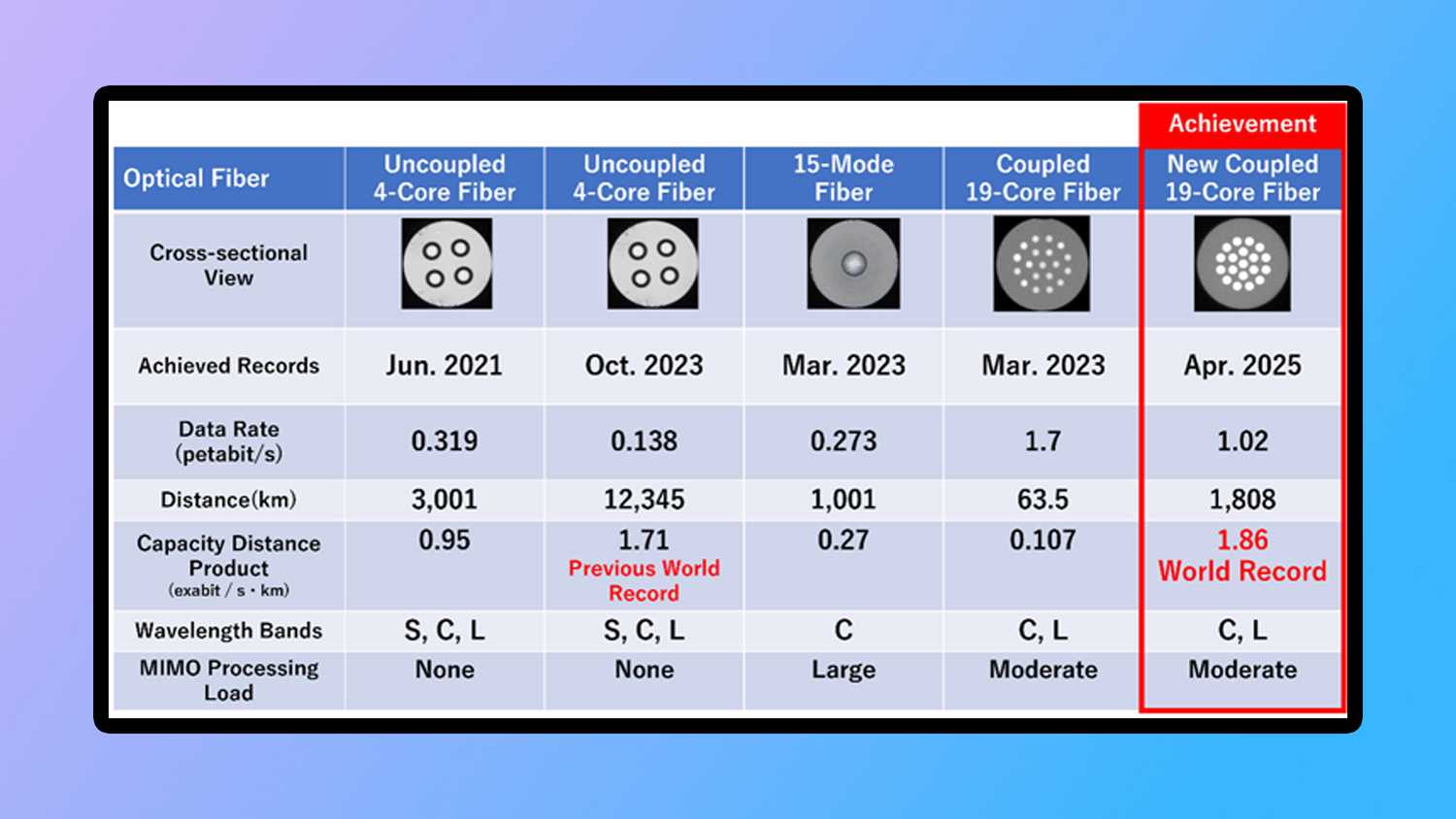

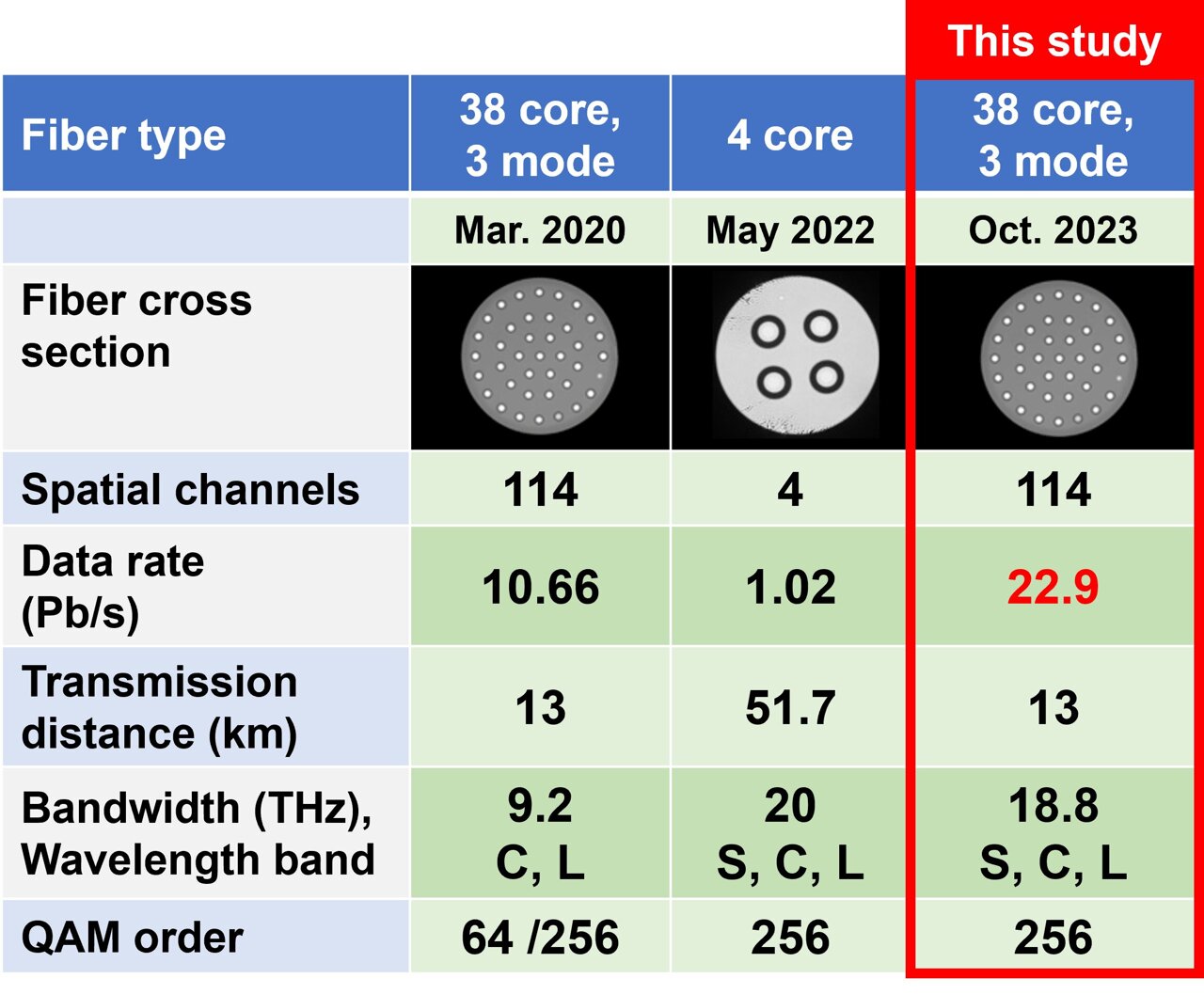

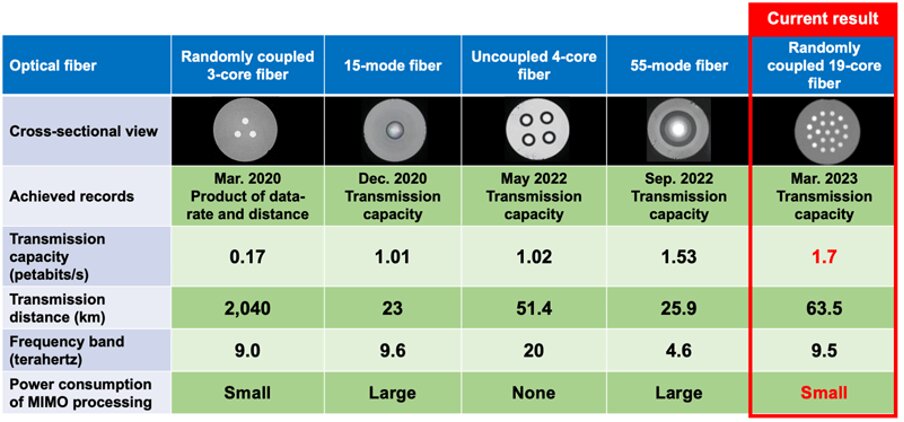

The 430 Tbps record uses standard single-mode fiber, emphasizing practicality, while the 1.02 Pbps record showcases maximum capacity using specialized techniques.

Spectral Efficiency: Getting More From the Same Spectrum

Spectral efficiency is one of those engineering concepts that sounds dry but actually determines whether future internet speeds are possible or not. It's the ratio between data transmitted and the bandwidth required to transmit it. Higher efficiency means more data in the same space.

The NICT team improved spectral efficiency by exploiting wavelengths that normally get filtered out. Standard fiber has a cutoff wavelength below which it was designed not to transmit. This cutoff existed because early fiber engineers weren't confident they could use those wavelengths reliably.

Techniques have improved. The research showed that by using cutoff-shifted fiber (fiber with a modified cutoff point), you can actually transmit below the original cutoff using higher-order modes. You get additional data capacity from wavelengths that were previously sitting there unused.

This is genuinely clever because it doesn't require new cables. It just requires smarter equipment at both ends of the transmission. You can keep the same fiber your ISP installed in 2010 and add new optical transmission gear that knows how to use those previously dormant wavelengths.

The Laboratory vs. Real-World Gap

Let's be honest about what happened here: this was a controlled laboratory experiment. The researchers weren't transmitting across a continent or dealing with the chaos of real network conditions.

In actual deployment, fiber gets damaged. Temperature fluctuates. Signal degrades over distance. Equipment needs to be installed and maintained by humans, many of whom didn't design it. Network management becomes exponentially more complex as you add features and modes.

Think about it this way: you can probably make your car go 200 mph in a test facility with perfect conditions. Getting it to reliably do that on an actual highway full of potholes, varying weather, and traffic is an entirely different problem.

The researchers acknowledged this. The press materials mention that all results were achieved under controlled conditions, and that translating laboratory achievements into resilient, economical, production networks depends on many factors beyond raw speed.

But here's why that limitation doesn't invalidate the finding: it establishes feasibility. It proves the technology works at all. From feasibility, companies can then spend the millions of dollars and years of engineering to make it practical for real networks.

The Infrastructure Already Exists

The most remarkable aspect of this breakthrough is something that gets buried in the technical details: the fiber infrastructure is already there. You don't need to lay new cables. You don't need to tunnel under oceans or mountains again. The hardware exists.

This is genuinely unusual in the world of telecommunications infrastructure. Usually, when you want major speed improvements, you need to physically replace cables. Submarine cables take years and billions to plan and install. Burying fiber under city streets requires excavation, coordination with municipalities, rerouting traffic. It's a massive undertaking.

But if the bottleneck isn't the fiber itself but rather how we're using it, then the path to deployment becomes dramatically simpler. You upgrade the optical transmission and reception equipment at network hubs. You push new firmware to the systems that manage the fiber. Much of the heavy lifting is software and electronics, not physical infrastructure.

Global fiber networks comprise more than several billion kilometers of cable. That's enough to wrap around Earth roughly 50 million times. If even a fraction of this becomes usable for these higher transmission rates, the aggregate capacity expansion is staggering.

The breakthrough demonstrates a potential increase in fiber optic speeds from an average of 100 Tbps to 430 Tbps, highlighting significant untapped capacity. Estimated data.

Comparing Different Approaches to Ultra-Fast Transmission

The NICT breakthrough isn't the only approach to extreme-speed connectivity being explored. Several different strategies are being researched simultaneously, each with different trade-offs.

Free-space optical communication represents one alternative. Researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology demonstrated 5.7 terabits per second wirelessly over 4.6 kilometers using focused infrared beams. This approach doesn't require fiber at all. You basically have extremely focused laser beams transmitting data through the air.

The advantage of free-space is that it avoids the cost and complexity of laying physical cables. The disadvantage is that weather impacts it. Heavy rain, fog, or clouds can disrupt transmission. You need perfect line-of-sight between transmitter and receiver. For long distances or across continents, this becomes impractical.

Another comparison point is the capacity-distance record. NICT and partners demonstrated 1.02 petabits per second (that's 1,020 terabits) over 1,808 kilometers using a 19-core fiber with standard diameter. This trades off distance for even higher speed. Petabit speeds over continental distances would be genuinely transformative for backbone infrastructure.

The 430 Tbps record emphasizes efficiency and deployment simplicity. The petabit approach optimizes for absolute maximum throughput but requires specialized 19-core fiber rather than standard single-mode fiber. Free-space optical eliminates infrastructure but adds environmental vulnerability.

Each approach serves different use cases. The NICT single-mode fiber result is probably most relevant to actual ISP deployment because it works with existing infrastructure. The petabit demonstration matters for core backbone networks between cities. Free-space has future applications in data center interconnects and places where cables are impractical.

The Role in Next-Generation Wireless Networks (7G and Beyond)

You'll notice the original research mentions implications for 7G wireless networks. This requires some explanation because the connection isn't direct or obvious.

Fiber optic networks form the backbone of wireless systems. Your 5G phone doesn't transmit data all the way to the internet through the air. It connects to a cell tower (base station), which connects via fiber to the network core. The fiber carries the aggregated data from thousands of users and links cell towers together.

If a 5G base station can theoretically receive 20 Gbps from a phone, but the fiber backhaul connecting that base station to the network only supports 10 Gbps, you've got a bottleneck. Improving fiber capacity means you can actually deliver on wireless speeds without the network core becoming the limiting factor.

7G (whenever it arrives, probably the 2030s) will likely require dramatically higher backhaul capacity than 5G. If wireless data rates scale up 100x or more, the fiber backbone needs to scale proportionally. Breakthroughs like 430 Tbps transmission establish that the backbone can handle it.

So the connection is real but indirect. The fiber research doesn't directly create 7G capability. It establishes that one necessary condition for 7G feasibility (sufficient backbone capacity) can be met without massive new infrastructure investment.

Technical Breakdown: How the Transmission Actually Works

For those wanting to understand the actual mechanics, here's how the researchers achieved 430 Tbps.

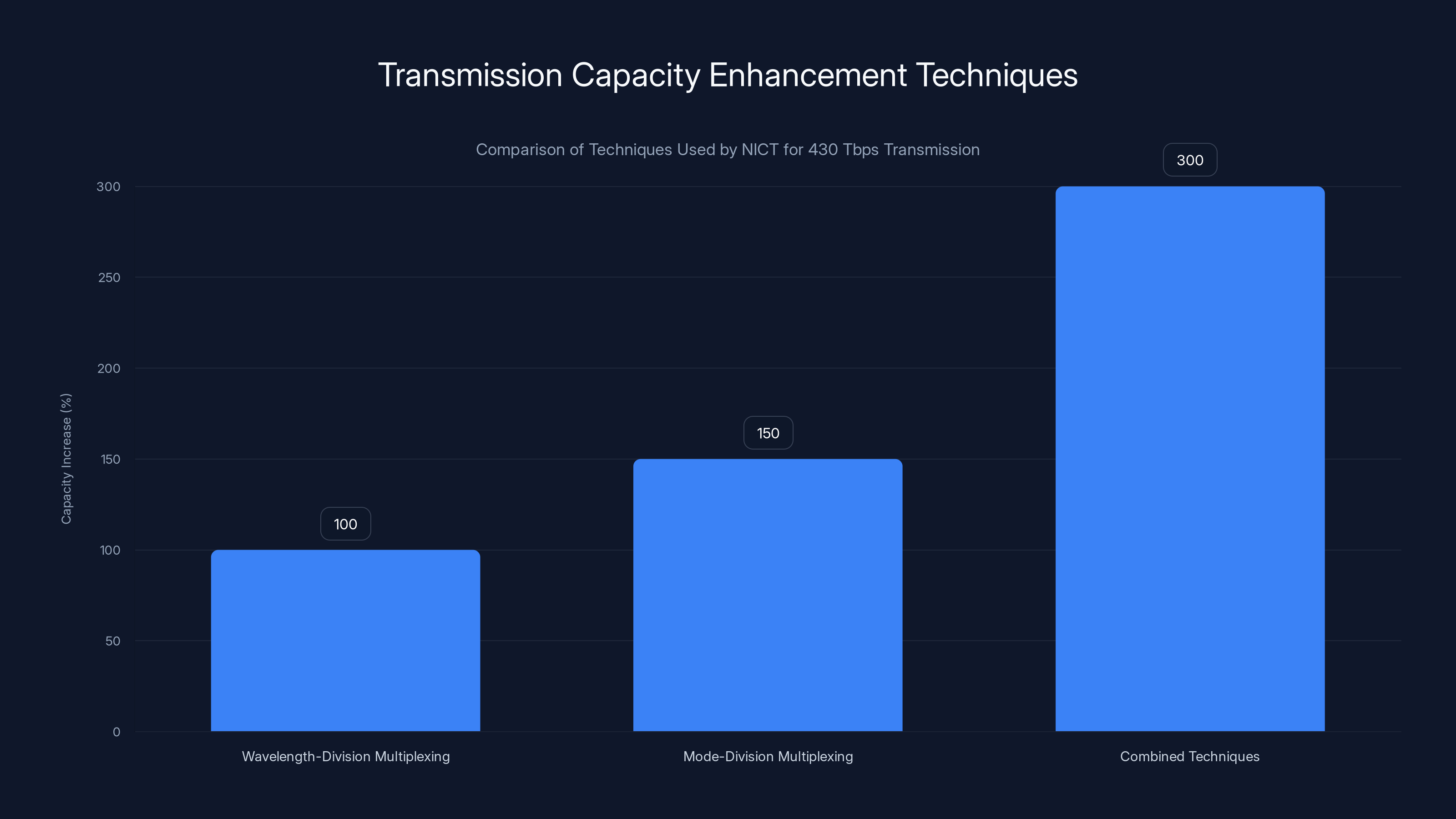

They used multiplexing, which means combining multiple signals into one transmission medium. Imagine how fiber optic networks already work: they use wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM), where different colors of light carry different data streams simultaneously. Red light carries one signal, green carries another, blue carries a third, and so on. The fiber carries all of them without interference because they're different wavelengths.

The NICT team added mode-division multiplexing on top of WDM. Instead of just using different wavelengths, they used different propagation modes simultaneously. Multiple different "patterns" of light traveled down the same fiber at the same time. Combined with wavelength multiplexing, this multiplied the transmission capacity.

They specifically used three modes in parallel. Getting three modes to propagate without interfering is the hard part. It requires careful control of launch conditions (how the light enters the fiber) and sophisticated signal processing at the receiver end (to separate the modes back out).

The specific frequency bands used (O-band and ESCL) matter because they have different characteristics. O-band (approximately 1,260-1,310 nanometers) is heavily used in existing networks. ESCL (1,460-1,625 nanometers) extends beyond the traditional single-mode cutoff.

By using wavelengths below the traditional cutoff with higher-order modes, they accessed transmission capacity that standard equipment simply doesn't use. It's like discovering that your current audio equipment can actually output at higher frequencies if you give it the right input signals.

The bandwidth reduction (20% less than comparable approaches) came from improved efficiency in how the data was encoded and how the modes were separated. Rather than requiring massive bandwidth to maintain separation, they used signal processing tricks to do more with less spectrum.

The combination of wavelength-division and mode-division multiplexing significantly increases transmission capacity, achieving a 300% increase compared to using wavelength-division alone. Estimated data.

Implications for Internet Service Providers

If you're an ISP executive, this research probably gave you some joy and some headaches. Joy because it potentially delays the need for massive infrastructure replacement. Headaches because it proves your existing network is vastly underutilized.

Currently, ISPs segment their fiber networks into tiers. Home broadband tier might be 500 Mbps. Business tier is 1 Gbps. Premium tier is 5 Gbps. These aren't hard technical limits on the fiber itself. They're commercial decisions. The ISP simply doesn't send higher-speed signals down those fibers.

From the ISP perspective, this makes business sense. Why offer unlimited speeds if people will pay more for higher tiers? But it also means consumers get a raw deal. Your fiber connection is physically capable of gigabits per second, but you're getting megabits because that's the service plan you're paying for.

Research like this from NICT creates pressure to increase speeds because it proves feasibility. It's harder to justify 500 Mbps limitations when the same cable technically supports terabits. Eventually (probably years from now), competition and pressure will force ISPs to actually offer speeds closer to what the fiber can provide.

The deployment cost for ISPs would mainly be equipment upgrades at network hubs. The expensive fiber installation is already done. So while 430 Tbps won't appear in home connections anytime soon, it establishes that when it eventually does, the fiber is ready.

Quantum Noise and Physical Limits

Eventually, there are hard physical limits to how much data you can push through fiber. The fundamental limitation comes from quantum mechanics and thermodynamics. This is called the Shannon limit, named after information theory pioneer Claude Shannon.

The Shannon limit describes the maximum data rate possible for a given signal power and noise level. As you try to push more and more data down a fiber, you have to work harder to distinguish signal from noise. Eventually, you reach a point where quantum effects become the limiting factor.

Current transmission speeds use only a small fraction of the Shannon limit for optical fiber. The NICT team's 430 Tbps result doesn't approach the theoretical limit. This means there's still more optimization possible.

How much more? Estimates vary, but some theoretical work suggests fiber could eventually handle multiple petabits per second (1000+ Tbps) if you optimized everything perfectly. We're not anywhere close to hitting the ceiling.

The reason we're not already there is practical engineering. Higher speeds require more precise equipment. Error correction becomes more complex. Power consumption increases. Cost escalates. There's always a trade-off between theoretical maximum and practical economics.

Challenges in Real-World Deployment

Moving from laboratory demonstration to actual deployment requires solving several classes of problems.

Signal degradation over distance: The 430 Tbps transmission was probably over relatively short distances (the research didn't specify exactly, but lab demonstrations typically use fiber lengths of meters to a few kilometers). Over hundreds of kilometers, the signal gets progressively more distorted. You need more sophisticated error correction and signal regeneration.

Temperature sensitivity: Optical fiber properties change with temperature. The light refraction properties vary, which affects the modes. In real deployment, fiber runs through tunnels, across deserts, under oceans. Temperature variations are constant. Equipment needs to compensate dynamically.

Non-linear effects: At very high power levels, fiber itself starts behaving nonlinearly. Signals interact with each other in complex ways. Managing these interactions requires advanced signal processing and compensation techniques.

Mode coupling: In practice, higher-order modes don't stay perfectly separated. They couple together as the fiber bends, vibrates, or experiences environmental stress. The receiver needs to continuously estimate and correct for mode coupling.

Equipment cost and complexity: Transmitting and receiving at 430 Tbps requires optical components operating at the cutting edge of physics and engineering. This equipment is expensive. Getting it to work reliably in the field is harder than in a lab where conditions are perfectly controlled.

Testing and standards: For any technology to get deployed widely, it needs to work with existing systems and be standardized. Right now, 430 Tbps transmission exists in a single experimental setup. Making it work with thousands of different installations, different fiber types, different equipment manufacturers requires extensive standardization work.

Estimated data: A 7% improvement in fiber capacity from 402 Tbps to 430 Tbps can significantly reduce the need for new cables, aligning with future demand for 10x capacity.

The Economics of Speed: When Will This Actually Reach Consumers?

Here's the real question everyone wants answered: when will my internet actually be this fast?

The answer is probably: not as soon as the headline suggests.

Internet infrastructure deployments move slowly. A breakthrough in 2024 typically reaches experimental deployment in major cities by 2027-2030, gets standardized by 2030-2035, and then gradually rolls out to the rest of the world over the next decade.

But more importantly: will ISPs actually offer these speeds to consumers? That's a business question, not an engineering question.

When gigabit internet became technically feasible, many areas got it. But not all. Some ISPs still don't offer it because they've determined there's insufficient demand to justify the investment. They'd rather keep customers locked into 100 Mbps plans and sell upgrades.

Terabit-speed internet makes even less sense for most home users right now. Downloading an 4K movie takes minutes at gigabit speeds. You probably don't need faster. For data centers and backbone networks? Absolutely. For regular internet users? It's overkill.

So the timeline is probably: terabit-speed fiber gets deployed in core backbone networks first (probably by 2030), then data center interconnects, then fiber backhaul for wireless towers, and only much later (if ever) gets offered to home users as a mainstream service.

When it does, there's another factor: latency and application support. Your browser can't actually use terabit speeds. HTTP, TCP/IP, and most internet protocols have overhead. Getting 430 Tbps to an end user is different from getting it between network hubs.

The Broader Context: Fiber Optics' Long Road

Fiber optics entered practical use in telecommunications in the 1970s. Before that, data traveled through copper wires, which had severe bandwidth limitations. Switching to fiber was revolutionary.

Yet 50 years later, researchers are still finding new ways to push data through the same fundamental medium. The fiber hasn't changed dramatically. The physics has stayed the same. But our understanding of how to exploit that physics has advanced continuously.

This pattern shows up throughout technology. You don't need revolutionary new materials or physics. You need continuous, incremental innovation in how you use what you have. It's less dramatic than discovering something new, but often more practically useful.

The NICT breakthrough sits in this tradition. It's not a revolutionary invention. It's clever engineering applied to a mature technology. It shows that mature doesn't mean maxed out. The systems we've already built still have enormous untapped capacity if you're smart enough to find it.

Other Speed Records and Competing Technologies

The 430 Tbps record isn't the only speed record being pursued. Different research teams are exploring different directions.

The petabit-per-second record (1.02 Pbps over 1,808 km) mentioned earlier represents a different optimization. That used 19-core fiber, which is more exotic than standard single-mode but still manufactured for deployment. The tradeoff is between using familiar cables (single-mode) and going much faster with less conventional fiber (multi-core).

Free-space optical communication continues improving. Focused infrared beams don't need cables at all, which is valuable for applications like satellite-to-ground links or data center interconnects across short distances where burying fiber is impractical.

Wireless networks are improving too. 5G is reaching theoretical speeds in the multi-gigabit range under ideal conditions. 6G research is exploring sub-terahertz and terahertz frequencies that could eventually enable wireless transmission in the terabits-per-second range (though at shorter distances and with more environmental sensitivity than fiber).

These aren't really competing. They're complementary. Future networks will probably use all of them: terabit fiber for core backhaul, multi-gigabit wireless for last-mile, free-space optics where cables are impractical.

Estimated data shows dramatic reduction in download time from hours on broadband to mere seconds at 430 Tbps.

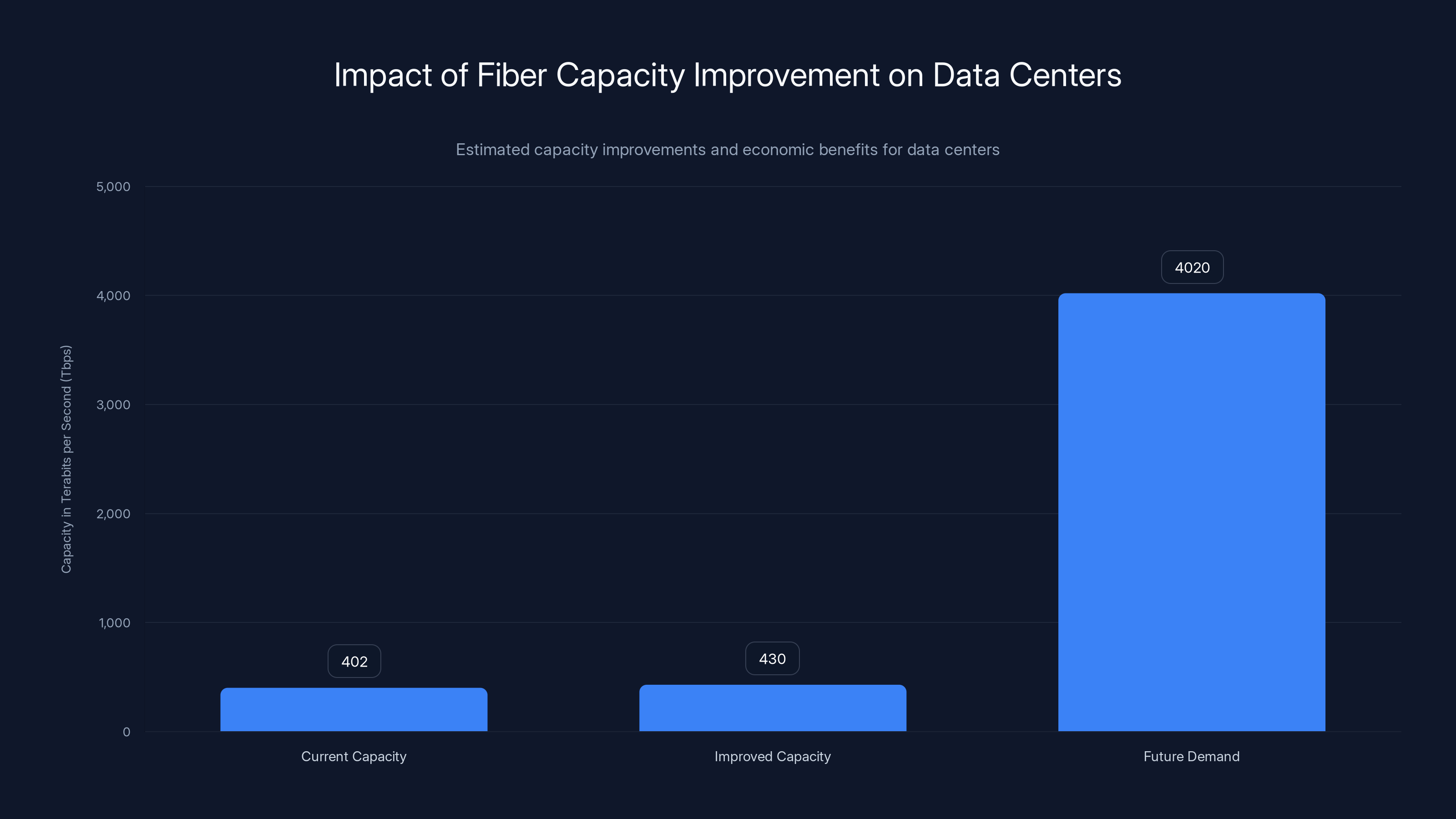

What This Means for Data Centers

Data center operators are the actual audience for this technology. While consumers wait years for speed improvements, data centers need multiple petabits per second of interconnect capacity right now.

Hyper-scale data centers (Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta) operate massive internal networks. Thousands of servers need to communicate with each other at line speed. Current fiber gets upgraded every few years, and those upgrades are expensive.

If you can get higher capacity from existing fiber instead of ripping out and replacing cables every two years, that's a massive economic win. Even a 7% improvement (from the 402 Tbps to 430 Tbps) translates to needing fewer cables and less frequent replacement cycles.

Data center economics drive a lot of telecommunications innovation. When a data center operator says they need 10x more capacity but can't accommodate 10x more cables, that creates pressure for research teams to figure out how to get 10x throughput from existing fiber.

The NICT breakthrough directly addresses this need. It shows that without more cables, you can still get significantly more capacity through smarter use of what's already there.

The Research Method and Peer Review

Understanding how this research happened adds credibility context. The NICT team presented findings at the 51st European Conference on Optical Communication in Denmark. That's a peer-reviewed, respected conference in the optical communications field.

The fact that they surpassed their own previous record (402 Tbps) is notable. It suggests they've been iterating on this approach, understanding it better with each attempt. This is more credible than a random breakthrough. It shows a progression.

Peer review doesn't mean the work is perfect or immediately deployable. It means other experts in the field vetted the methodology and findings. They likely asked hard questions about measurement accuracy, whether the approach actually scales, what assumptions were made.

Publishing at a major conference with peer review is also different from a company press release. Universities and research institutes have institutional reputation to maintain. They're not claiming something works for market advantage; they're reporting what actually happened in their lab.

That said, the researchers were appropriately cautious. They noted that the results were achieved under controlled conditions and that real-world deployment faces additional challenges. This intellectual honesty (admitting limitations) is actually a sign of credible research.

Future Research Directions

From here, the research probably branches into several directions.

One track is scaling the distance. If 430 Tbps works over a few kilometers in a lab, can it work over 100 kilometers? 1,000 kilometers? Getting high-speed transmission over continental distances is the real problem.

Another track is cost reduction. The optical components needed for 430 Tbps transmission are probably expensive right now. Manufacturing scale and innovation can bring costs down, but that requires significant effort and investment.

A third track is integration. Right now, this is a point-to-point transmission demonstration. Real networks need this integrated with multiplexing, switching, routing, error correction, and management systems. Making all of that work together at scale is different from demonstrating the transmission itself.

Robustness and reliability matter too. Lab demonstrations often work under near-perfect conditions. Making systems that work reliably in noisy, variable, real-world conditions requires additional research and engineering.

Standardization is crucial. For widespread adoption, this technology would need to get incorporated into standards bodies' specifications. That's a slow, consensus-based process.

Comparison with Previous Speed Records

Putting the 430 Tbps achievement in historical context:

- 2006: First 10 Tbps transmission over long distance

- 2013: 400 Tbps achieved in laboratory

- 2018: 1.02 Pbps (1,020 Tbps) with specialized fiber over long distance

- 2020: 402 Tbps with standard fiber (NICT's earlier record)

- 2024: 430 Tbps with standard fiber (current record)

What jumps out: the jump from 2013 to 2018 was massive (400 to 1,020 Tbps). The recent incremental improvements (402 to 430) are smaller but using more practical fiber. The petabit achievement came at the cost of specialized fiber. The new record prioritizes practicality.

This suggests research focus is shifting from absolute maximum speeds to deployable speeds. That's actually a maturation of the field. Early-stage research pushes theoretical limits. Mature research optimizes for real-world constraints.

Security Implications

Here's something almost nobody talks about: terabit-speed networks introduce new security challenges.

When data moves that fast, traditional security inspection becomes impractical. Firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and other security tools typically examine packets to identify threats. At terabit speeds, you can't examine every packet in real-time with current technology.

You need to either redesign security systems for terabit speeds or accept that some traffic won't get examined as closely. Both options create risks.

Another issue: with dramatically more data capacity, potential attackers have more "space" to hide attacks in noise. If your network has a few gigabits of traffic, security teams notice when something unusual appears. If it has petabits of traffic daily, hiding an attack becomes easier.

These challenges aren't showstoppers. They're solvable with research and new approaches. But they're real concerns that operators will need to address as speeds increase.

Energy Consumption: The Hidden Challenge

Transmitting at 430 Tbps requires significant optical power. Fiber doesn't transmit data for free. You need laser light at specific wavelengths, amplifiers to boost that light periodically, and optical receivers sensitive enough to detect weak signals.

All of that consumes electricity. As transmission speeds increase, power consumption per unit data usually decreases (better efficiency), but absolute power consumption can still be significant.

Data centers are already struggling with power consumption and cooling. Network equipment that's vastly more power-hungry would create problems for them, even if it increased throughput.

The researchers probably optimized for this (the 20% bandwidth reduction helps with power), but it's an aspect worth tracking as this technology moves toward deployment.

FAQ

What exactly is 430 Tbps transmission?

430 Tbps (terabits per second) represents 430 trillion bits of data transmitted per second over a fiber optic cable. Researchers from NICT and Aston University achieved this using standard single-mode fiber, the same type already installed in global telecommunications networks. The achievement demonstrates that conventional fiber infrastructure has untapped capacity that can be accessed through advanced transmission techniques and signal processing.

How does multi-mode transmission work in fiber optics?

Multi-mode transmission sends multiple distinct propagation patterns (modes) of light down a single fiber simultaneously. In the NICT breakthrough, three different modes traveled parallel to each other at different wavelengths in the O-band and ESCL frequency ranges. Signal processing equipment at the receiver end separates these modes back into distinct data streams. Traditionally, single-mode fiber was designed to prevent this, but researchers developed techniques to control and exploit multiple modes without problematic interference.

Why is this breakthrough important if it's just a laboratory demonstration?

Laboratory demonstrations establish technical feasibility and inspire research toward real-world deployment. This particular achievement is significant because it uses standard fiber already deployed globally, meaning eventual implementation wouldn't require massive new infrastructure investment. The 20% bandwidth efficiency improvement shows that existing networks are underutilized, and the research path toward practical deployment becomes more economically viable than approaches requiring specialized cables or completely new infrastructure.

What's the difference between this 430 Tbps record and the 1.02 Pbps (petabit) record mentioned in the research?

The 430 Tbps record prioritizes practicality by using standard single-mode fiber and existing infrastructure. The 1.02 Pbps record, achieved over 1,808 kilometers, used 19-core specialized fiber instead. The petabit demonstration achieved higher absolute speed over longer distances but requires non-standard cables. These represent different optimization priorities: the 430 Tbps approach focuses on deployability, while the petabit approach pushes theoretical maximum transmission rates.

How will this technology reach actual internet users?

Deployment typically follows a progression: first to core backbone networks connecting major data centers and network hubs (probably by 2030s), then to fiber backhaul for wireless cell towers, then eventually to enterprise connections, and finally to consumer broadband services. Each stage requires standardization, equipment manufacturing at scale, network integration, and economic justification. Consumer-facing terabit speeds would probably arrive 10-15 years after initial backbone deployment, assuming ISPs decide the market demands it.

What are the practical limitations preventing immediate deployment?

Several challenges require solving before widespread deployment: signal degradation over continental distances, temperature sensitivity of optical components, mode coupling and nonlinear effects in long-distance transmission, equipment cost and complexity, integration with existing network management systems, and standardization requirements. The NICT team explicitly noted their results were achieved under controlled laboratory conditions, implying that real-world variables introduce additional challenges not addressed in the initial demonstration.

How does this relate to 7G wireless networks?

Fiber optic networks form the backbone supporting all wireless systems. Cell towers connect to network cores through fiber "backhaul." Future 7G wireless will require significantly higher backbone capacity to transport data from many users simultaneously. This 430 Tbps research demonstrates that the fiber backbone can provide the necessary capacity without requiring entire infrastructure replacement. The connection is indirect but essential: terabit fiber capacity enables terabit wireless capacity to actually function.

What is spectral efficiency and why does the 20% improvement matter?

Spectral efficiency measures how much data you can transmit per unit of bandwidth. Higher efficiency means more information in the same electromagnetic spectrum. The NICT team achieved 430 Tbps while using approximately 20% less overall bandwidth than comparable approaches. This matters because spectrum is a limited resource. Getting more data from less spectrum means you can serve more users or increase speeds without needing more spectrum allocation from regulators.

Are there alternative approaches to extreme-speed networking competing with this fiber technology?

Yes, multiple approaches are being researched simultaneously. Free-space optical communication using focused infrared beams achieved 5.7 Tbps but without requiring cables (limiting deployment to short distances and clear weather). Wireless networks like 5G and future 6G approaches are pushing toward multi-gigabit speeds but face different challenges than fiber. These approaches aren't directly competing; they're complementary and will likely coexist in future networks, each optimized for different use cases.

When will data centers actually deploy 430 Tbps transmission?

Data center operators are the most likely early adopters since they need massive interconnect capacity and can justify equipment costs through operational savings. Experimental deployments could appear within a few years, but widespread adoption would take longer as the technology gets integrated with routing, switching, and management systems. For backbone links between data centers, expect gradual deployment starting in the late 2020s or early 2030s.

What physical limits exist for fiber optic transmission speeds?

The Shannon limit from information theory defines the absolute maximum data rate for a given signal power and noise level. Quantum mechanical effects eventually become limiting factors. Current fiber transmission uses only a small fraction of the theoretical Shannon limit, suggesting significant room for future improvement. Estimates suggest fiber could eventually handle multiple petabits per second under optimal conditions, but practical deployment is years away from approaching these limits.

Key Takeaways

The NICT and Aston University breakthrough demonstrates that existing fiber optic infrastructure has dramatic untapped capacity. At 430 terabits per second, using standard cables already deployed globally, the research proves that speed increases don't require massive new cable installation. The approach achieved this through clever use of multiple transmission modes operating simultaneously in parallel wavelength bands, improving spectral efficiency by approximately 20%. While the breakthrough remains confined to laboratory conditions, it establishes feasibility for eventual real-world deployment in data center interconnects and network backhaul applications. The technology has indirect but important implications for future wireless standards like 7G, ensuring that network backbones can handle the capacity demands of next-generation wireless speeds. Deployment on production networks will take years and requires solving challenges around distance degradation, temperature sensitivity, mode coupling, standardization, and equipment cost reduction. The research reflects a broader pattern in telecommunications: mature technologies continue yielding performance improvements through better understanding and clever engineering rather than revolutionary new discoveries.

Related Articles

- Verizon Outage 2025: Complete Timeline, Impact Analysis & What to Do [2025]

- Verizon's Visible Outage Credits: What You Need to Know [2026]

- Iran's Internet Shutdown: Longest Ever as Protests Escalate [2025]

- Verizon's $20 Credit After Major Outage: Is It Enough? [2025]

- Verizon Outage 2024: What Happened and Why 911 Failed [2025]

- Iran Internet Blackout: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

![430 Tbps Fiber Optic Speed Record: What It Means for 7G [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/430-tbps-fiber-optic-speed-record-what-it-means-for-7g-2025/image-1-1768777562390.jpg)