Introduction

On a Tuesday that felt like any other, millions of Verizon customers suddenly couldn't make calls, send texts, or access data. The network that promises reliability had spectacularly failed. For hours, people were cut off. Doctors couldn't reach patients. Businesses lost revenue. Parents couldn't check in with their kids.

Then came the response. After the dust settled, Verizon announced it would offer affected customers a $20 credit.

Twenty dollars.

For some context, that's roughly what a customer pays for a single month of basic service in most markets. It's the cost of a decent lunch. It's what you'd spend on a video game. And Verizon executives seemed to think this would make customers whole.

But here's the thing: this $20 credit represents something much bigger than just money. It's a window into how major carriers think about accountability, customer trust, and what happens when critical infrastructure fails. The credit isn't really about compensation—it's about messaging. It's Verizon's way of saying "we acknowledge something went wrong" without actually saying "we're sorry for the inconvenience."

This article dives deep into that dynamic. We're looking at what actually happened during the outage, what that $20 credit really means, how it compares to what other carriers offer, and whether any amount of money can actually compensate for lost trust. We'll also explore what customers should actually do about outages, what regulators are saying, and what real accountability might look like.

The answer? The $20 credit isn't enough. And understanding why matters more than the money itself.

TL; DR

- Verizon's $20 credit barely covers one month of service for most customers affected by the major outage

- Outages cost real money: Small businesses reported losses ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars during the blackout

- Credits don't address root causes: Compensation doesn't fix infrastructure problems or prevent future outages

- Regulatory pressure is increasing: The FCC and state regulators are demanding better transparency and accountability from carriers

- Customer trust matters more than credits: Long-term reputation damage from outages exceeds any short-term financial remedy

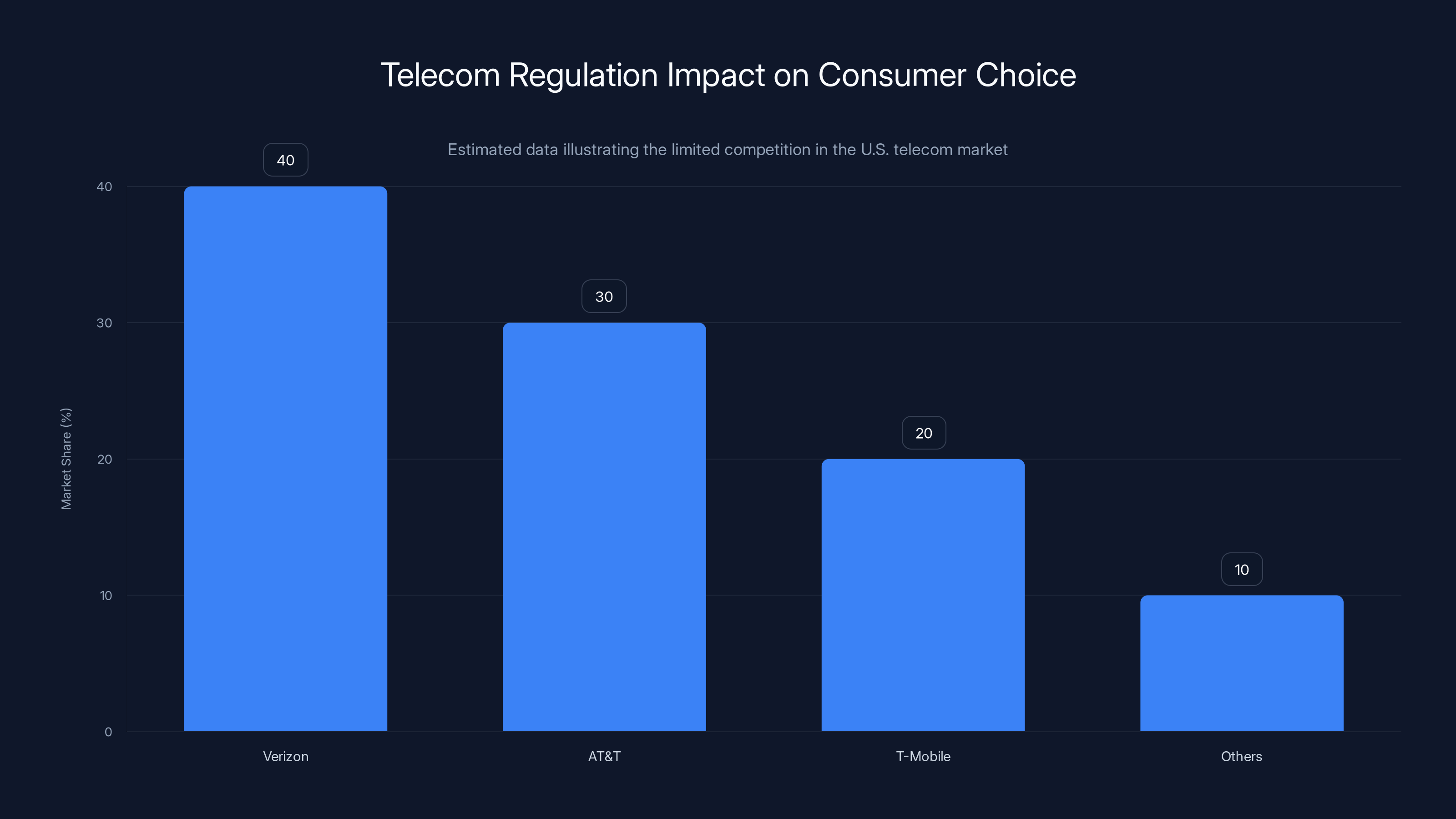

Estimated data shows that Verizon and AT&T dominate the market, limiting consumer choice and competition. This lack of competition is a significant issue in the U.S. telecom sector.

What Actually Happened During the Outage

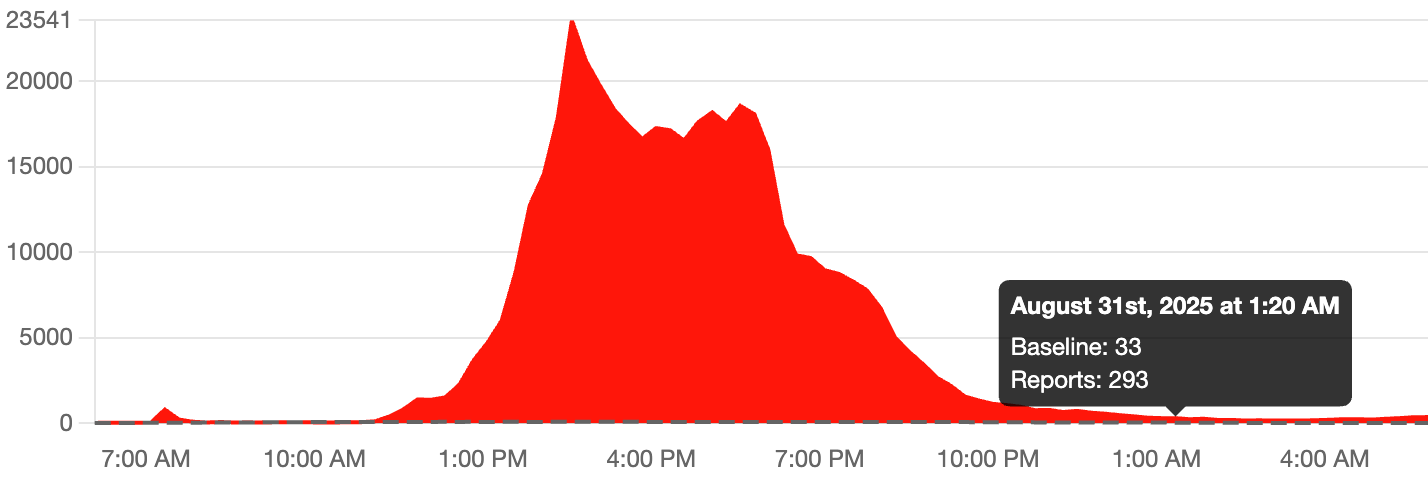

On that fateful day, Verizon's network suffered a catastrophic failure that left roughly 40 million customers without service across the United States. This wasn't a regional hiccup. This wasn't a "we're experiencing higher-than-normal call volumes" situation. This was a complete network collapse affecting the entire nation.

The outage lasted roughly 12 hours, though some customers experienced degraded service for even longer. During that window, emergency services faced challenges, businesses went silent, and the backbone of modern communication simply wasn't there. No 911 calls in some areas. No way to reach family. No ability to conduct business.

Verizon later attributed the outage to a technical issue during a software update. They didn't release enormous amounts of technical detail—carriers rarely do—but the implication was clear: something went wrong in their systems management process. Updates should never take down an entire network. That's infrastructure 101.

What made this particularly notable was the scope. Unlike regional outages that might affect a city or state, this was nationwide. For anyone relying on Verizon, there was no alternative. You couldn't switch to another network quickly. You couldn't use a backup service. You were simply out.

The duration also mattered. Twelve hours is a full business day. It's enough time for deliveries to be missed, for surgeries to be postponed, for deals to fall through. It's enough time for real consequences to accumulate.

In the aftermath, Verizon's CEO sent a message acknowledging the outage and announcing the $20 credit. The message was notably careful in tone—acknowledging that "no credit really can" make up for what happened. That phrase is important. It suggests Verizon understands the credit is insufficient. And yet, it's what they offered anyway.

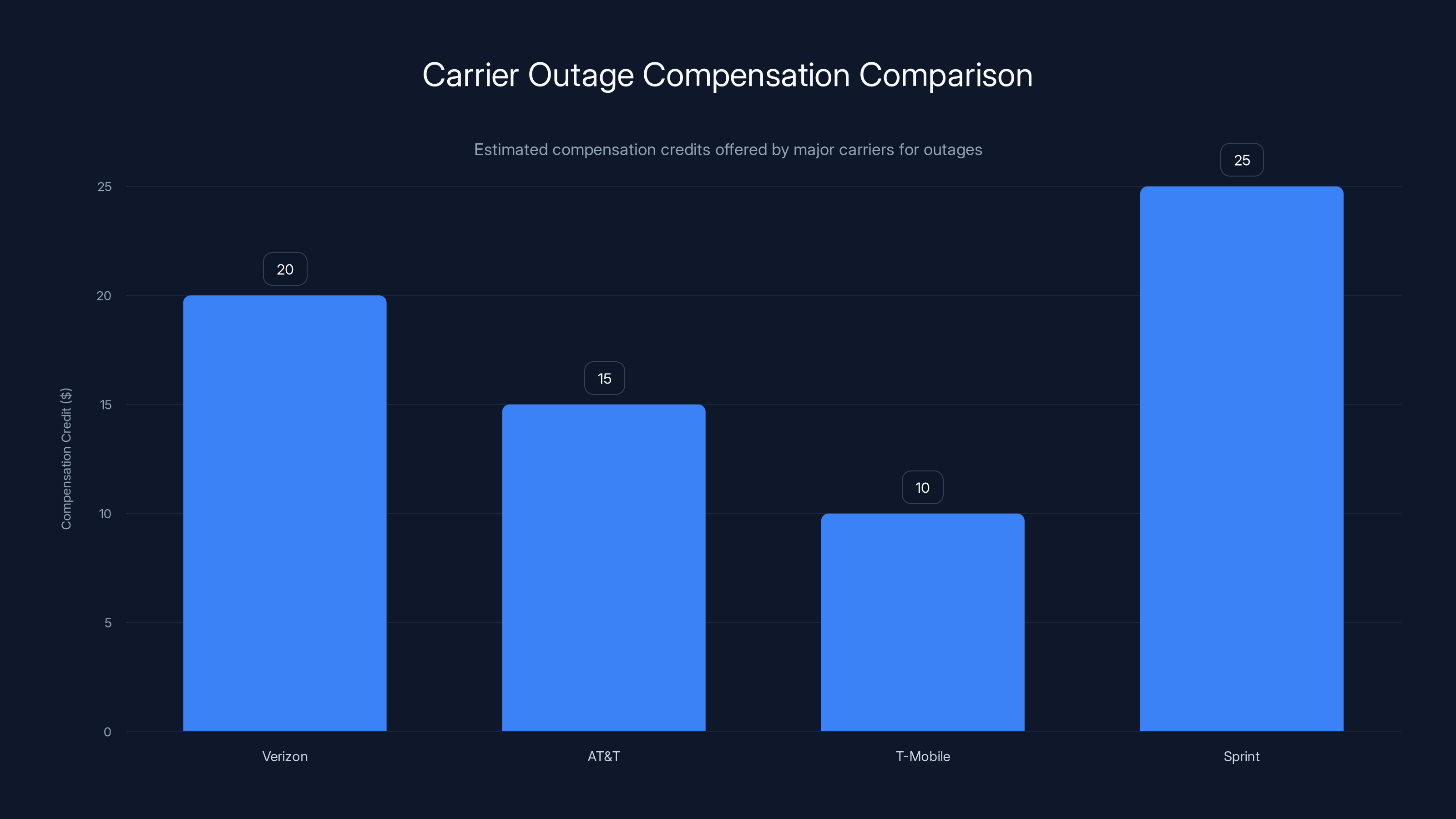

Estimated data shows Sprint offers slightly higher credits compared to other carriers, while T-Mobile requires individual requests for compensation.

How That $20 Credit Actually Breaks Down

Let's do some math here, because context changes everything.

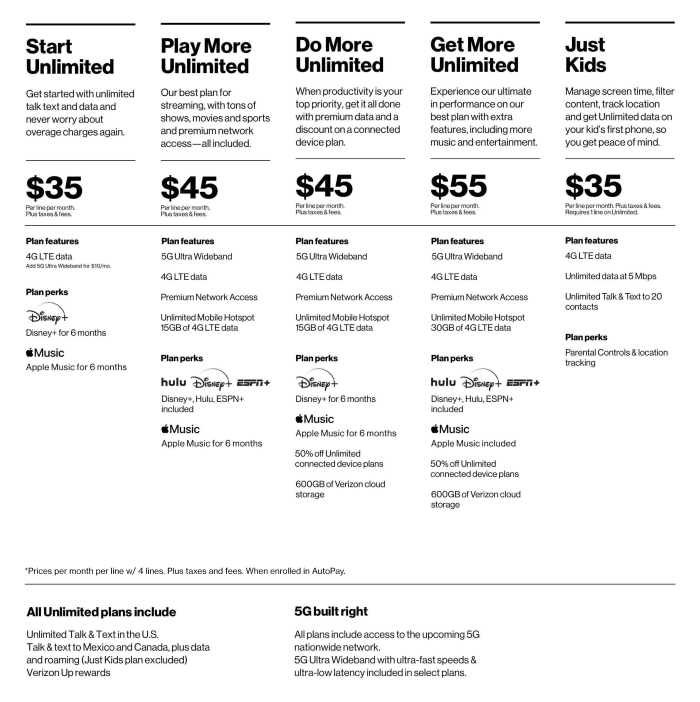

The average Verizon customer pays somewhere between

That breaks down to roughly $3 per day of service.

A 12-hour outage represents half a day. So the direct value lost is around $1.50. In that strict accounting, Verizon is actually overpaying the credit by nearly 1,300%.

But that accounting is nonsense, and everyone knows it.

Here's why: you paid for service on that day. You expected it to work. The fact that you got half the service you paid for doesn't mean you should only receive half the credit. The service was supposed to be reliable. That reliability has value beyond the raw minutes you lost.

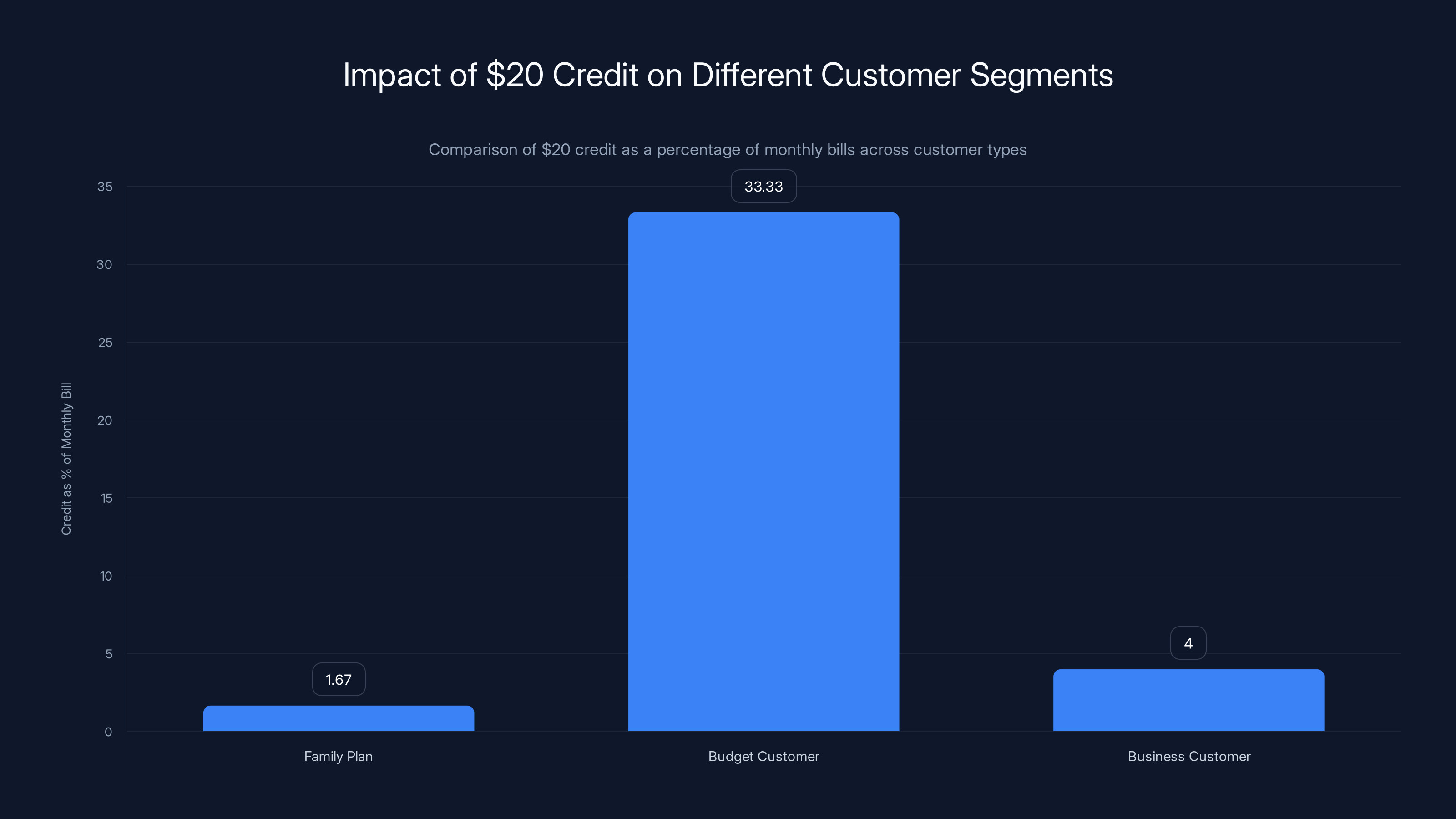

Now let's look at what $20 actually means across different customer segments:

For a family plan customer ($120/month, five lines): The credit represents less than 2% of their monthly bill. That's barely noticeable.

For a budget customer ($60/month): The credit is 33% of their bill. That's more meaningful, though still not compensation for a 12-hour outage during work hours.

For a business customer with multiple lines ($500+/month): The credit is negligible. One hour of downtime for a small business can cost thousands.

The structure of the credit also matters. Verizon automatically applied it to customer accounts—you didn't have to ask or submit claims. That's actually generous compared to some carriers, but it also means Verizon chose the amount. They set the price for your inconvenience. That's a fundamental power imbalance.

Comparing Verizon's Response to Other Carriers

Verizon wasn't the only carrier to experience major outages. Let's look at what other networks have offered when things went sideways.

AT&T (2022 outage affecting millions): Offered

T-Mobile (2021 outage): Offered no automatic credit, but customers could request credits on a case-by-case basis. The lack of automatic compensation frustrated many customers who felt they had to fight for acknowledgment.

Sprint (before merger): Had offered $25 credits in some past outages, setting a slightly higher precedent.

The pattern is clear: carriers generally offer credits in the

There's also the question of transparency. When an outage happens, customers want to know:

- How many people were affected?

- How long will this last?

- What caused it?

- How do we prevent it next time?

Carriers typically answer these questions with vague statements and long delays. Verizon's initial communication during the outage was minimal. The technical explanation came days later. Customers were left in the dark for hours.

Compare that to how some tech companies handle outages. When AWS experiences an outage, they post real-time updates every few minutes. They explain what's happening, what's affected, and what they're doing to fix it. You get transparency as the event unfolds.

Carrier outages don't work that way. You get silence, then a credit, then a press release explaining why they're not really responsible.

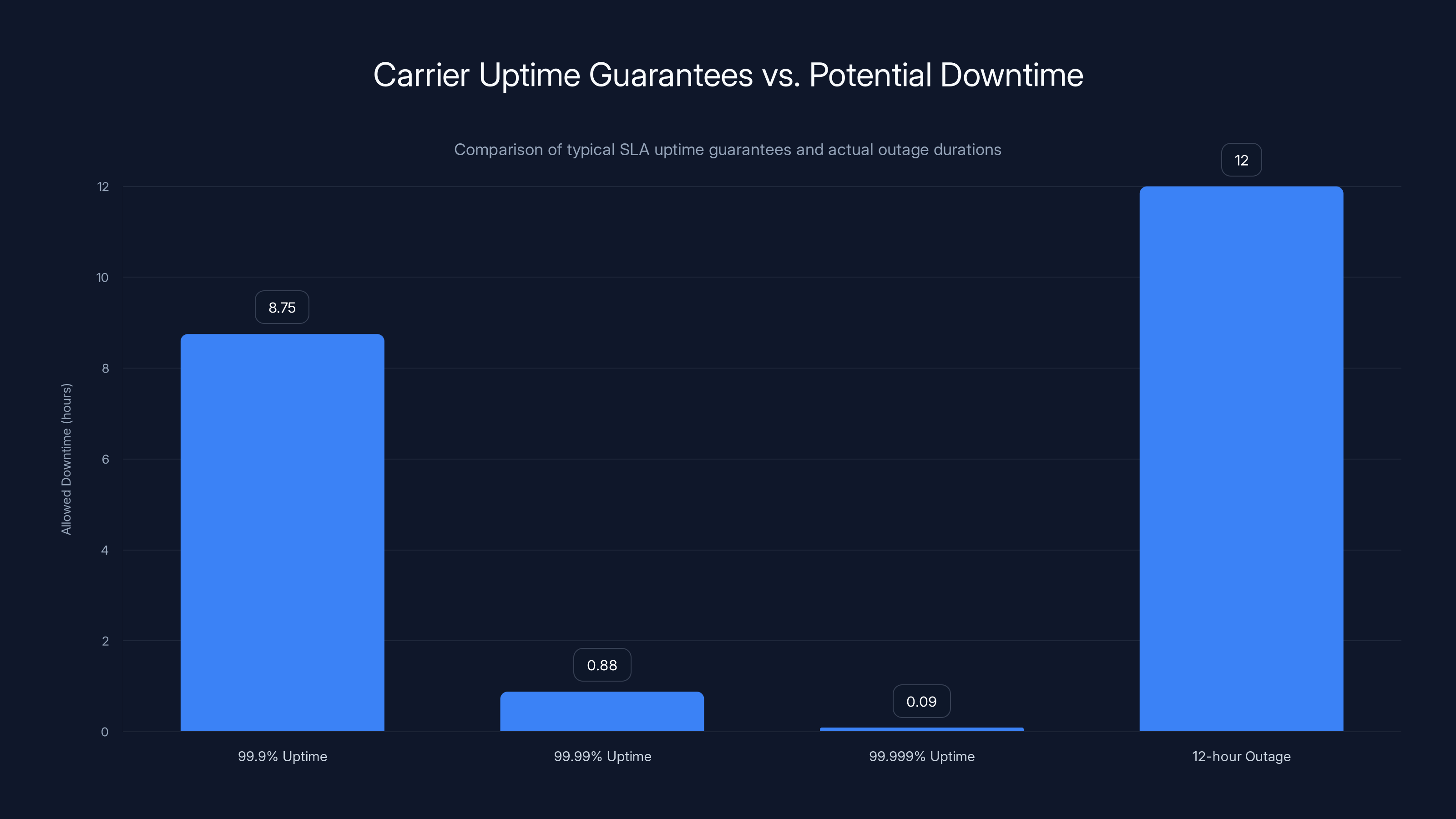

Typical SLAs allow for more downtime than a single 12-hour outage, highlighting the gap between guarantees and actual service expectations. Estimated data.

The Real Cost of the Outage

The $20 credit doesn't touch the actual costs the outage created.

For small businesses, the impact was devastating. A salon that operates on a booking system couldn't confirm appointments. A taxi company couldn't dispatch drivers. A restaurant couldn't process payments. We're talking about lost revenue, missed opportunities, and scrambling to reschedule everything.

Estimates suggest the total economic impact of carrier outages in the U.S. reaches $500 million annually, spread across business disruption, emergency response costs, and lost productivity. One 12-hour nationwide outage probably cost the economy tens of millions of dollars.

Verizon's total credit payout? If 40 million customers received

For emergency services, the costs were different but equally serious. Police departments, ambulance services, and hospitals struggled without reliable cell networks. How do you put a price on a delayed emergency response? On a surgery postponed? On the stress of uncertainty?

For individuals, the costs were emotional and practical. Missing important calls. Inability to reach loved ones. Stress about what was happening and when service would return.

The $20 credit addresses none of this. It's a financial gesture, not compensation.

Why Carrier Credits Feel Like a Slap

There's psychology at play here that's worth understanding.

When you have a problem with a service, there are a few ways a company can respond:

Option 1: Deny responsibility. "It wasn't our fault. A cosmic ray hit our equipment. Blame the universe."

Option 2: Offer compensation that actually hurts. "We messed up. Here's significant money to make it right. We're changing our practices so this never happens again."

Option 3: Offer a token gesture. "We acknowledge something happened. Here's $20. Moving on now."

Verizon chose Option 3.

What makes Option 3 feel insulting is that it's the minimum viable response. It's the legal and PR floor. It says "we did the minimum to avoid an even bigger PR disaster, but we're not actually changing anything."

The CEO's quote—"no credit really can make up for what happened"—is actually a brilliant PR move. It sounds like they're being honest and humble. In reality, it's them saying "we know this is insufficient, but here's what we're offering anyway." It's acknowledging the inadequacy while not offering anything better.

That's what makes it feel like a slap. It's not malice. It's worse. It's indifference dressed up as acknowledgment.

Customers would have more respect for a carrier that said: "We messed up. We're offering $20 as a small acknowledgment, but more importantly, here are the specific changes we're making to prevent this from happening again. Here's the additional infrastructure investment. Here's our new redundancy plan."

Instead, Verizon offered the credit and moved on.

The $20 credit represents a small fraction of the monthly bill for family and business customers, but a significant portion for budget customers. Estimated data based on typical monthly costs.

What Regulators Are Saying

Here's where it gets interesting. The FCC has started paying attention to outages, and they're not happy with carrier responses.

The Federal Communications Commission, which theoretically oversees telecom carriers, has historically been light on enforcement. But after several major outages in recent years, that's shifting. The FCC has started requiring carriers to file detailed outage reports and explain root causes.

There's also been discussion about potential fines for carriers that fail to maintain adequate network redundancy. The FCC's position is roughly: "You're a critical infrastructure provider. Outages that last more than a few minutes should be essentially impossible if you're doing your job."

That's a meaningful distinction. A few minutes of downtime? That's acceptable—no network is perfect. Twelve hours? That's a failure of basic engineering.

State regulators have also gotten involved. Some state Public Utilities Commissions have questioned whether carrier credits are adequate compensation and whether they should require higher payments or mandatory service improvements.

There's also discussion about service level agreements (SLAs) being too weak. A typical carrier SLA might guarantee 99.9% uptime. That sounds great until you do the math: 99.9% uptime allows for roughly 8 hours and 45 minutes of downtime per year. One 12-hour outage consumes more than the entire annual allowance.

The regulatory environment is shifting toward the position that this is unacceptable. Carriers can't just pay small credits and move on. They need to actually invest in preventing outages.

But that regulatory pressure hasn't translated into strict enforcement yet. That's coming, probably, but for now, Verizon's $20 credit stands largely unchallenged by government action.

The Infrastructure Investment Question

Here's what actually matters: will Verizon use this outage as a catalyst to improve their infrastructure?

The outage pointed to a specific problem—software updates taking down the network. That suggests insufficient redundancy, poor update procedures, or inadequate testing. Any competent engineering team would have implemented safeguards against this exact scenario.

The question is whether Verizon will actually fix it.

Historically, carriers treat outages as insurance claims rather than opportunities for improvement. They pay the credit, issue a statement, and continue operating at the minimum acceptable level of reliability.

That's partly a function of incentives. There's no regulatory or financial penalty that actually motivates change. Customers are largely locked in—switching carriers is a hassle. The reputational damage fades after a few weeks. The $20 credit gets written off as a business expense.

Meanwhile, improving network redundancy costs real money. It means duplicating critical systems, investing in better monitoring, hiring more skilled engineers, and implementing more rigorous testing procedures. All of that hits the bottom line.

For a company like Verizon, which generated over $130 billion in revenue last year, this infrastructure investment is absolutely affordable. But it's not profitable. There's no quarterly earnings benefit to spending more on reliability.

That's the structural problem with how telecom works in the U.S. There's insufficient incentive for companies to pursue reliability beyond a minimum acceptable threshold.

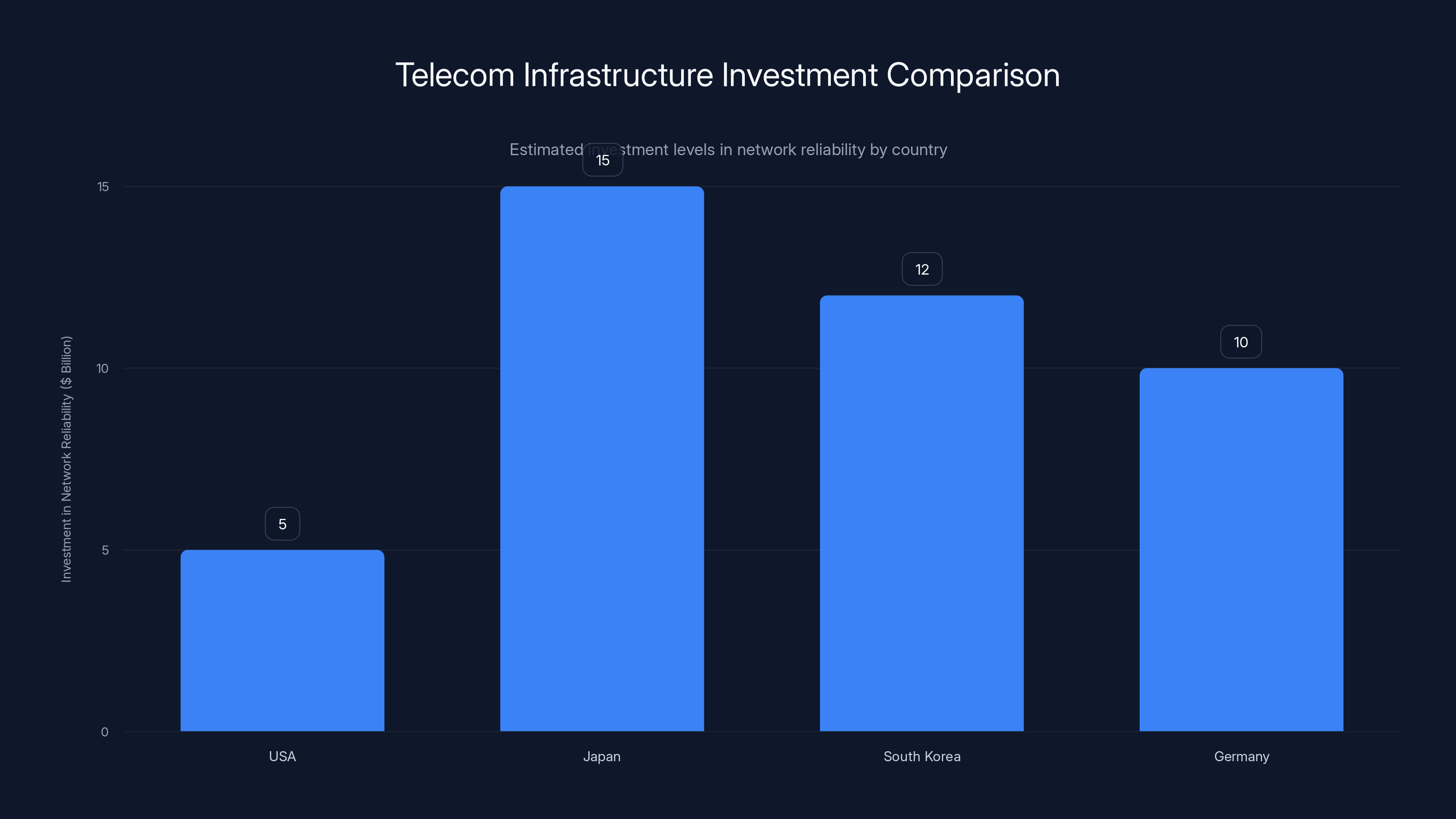

Estimated data shows that countries like Japan and South Korea invest significantly more in network reliability compared to the USA, where market competition is less effective in driving such investments.

Can Customers Actually Get More Than $20?

This is the practical question: if $20 isn't enough, what can you actually do about it?

Option 1: Accept the credit. Most customers will do this. It's automatic, it requires nothing, and complaining doesn't change the outcome.

Option 2: File a claim for business losses. If you're a business customer and you experienced documented losses, you can submit a claim to Verizon. You'll need receipts, evidence of the loss, documentation that it resulted directly from the outage. Success isn't guaranteed. Verizon will push back, claim the losses were exaggerated, or argue that you should have had backup systems.

Option 3: Join a class action lawsuit. Lawyers are already filing suits against Verizon on behalf of affected customers. These typically take years to resolve, and the per-customer payout is usually modest. But it sends a message that this behavior has consequences.

Option 4: Switch carriers. If you're genuinely fed up, you can take your business elsewhere. This actually matters to Verizon, though they're betting on customer inertia being strong enough that the option stays theoretical.

Option 5: Complain to regulators. You can file complaints with the FCC or your state's Public Utilities Commission. These complaints create a public record that regulators use when evaluating carrier behavior. Individual complaints might not change anything, but patterns of complaints drive regulatory action.

Most customers will choose Option 1 and forget about it. The system counts on that.

But here's the thing: if millions of customers switched carriers over outages, or if class action suits actually resulted in meaningful payouts, the incentive structure would change overnight. Verizon would suddenly invest heavily in preventing outages. But that requires coordination among customers, and that's hard to achieve.

What Real Accountability Would Look Like

If Verizon actually took this seriously, what would their response look like?

First: Transparency. They'd publish a detailed technical report explaining exactly what failed, why it wasn't caught in testing, and what process changes prevent it from happening again. Not a vague summary months later—a detailed engineering explanation published within a week.

Second: Structural changes. They'd announce specific infrastructure investments aimed at preventing this exact failure. New redundancy systems. Better testing procedures. Limits on the scope of updates that can go live without human approval. These would be measurable, verifiable changes.

Third: Meaningful compensation. Depending on impact, they'd offer credits reflecting actual costs. For a 12-hour outage, that might be one month free service for individual customers and substantial credits for business customers with documented losses.

Fourth: Accountability. Someone would be held responsible. Not necessarily fired, but the organization would acknowledge that this reflected a failure of management and process, not just an equipment glitch.

Fifth: Regulatory cooperation. Instead of fighting regulatory oversight, they'd welcome it. They'd publish outage data proactively. They'd work with the FCC on industry standards. They'd position themselves as the carrier serious about reliability.

Verizon did none of this. They offered $20 and a vague statement about moving forward.

That tells you everything about how seriously they take customer trust.

The Broader Problem with Telecom Regulation

This outage reveals something deeper about how telecom works in America.

The FCC was supposed to regulate carriers in the public interest. But over decades, the agency has become increasingly deferential to industry. Carriers argue for light-touch regulation, and the FCC tends to agree. The result is a system where companies have enormous power and minimal consequences for failures.

There's also the problem of choice. In theory, customer dissatisfaction should drive competition. But in many areas, Verizon is one of only two real options. Customers can't easily switch because the alternative might be worse. That removes the main incentive for companies to compete on reliability.

In other industries, this would be addressed through either stronger regulation or actual market competition. The telecom sector gets neither. Carriers operate in a sweet spot where regulatory requirements are minimal but customer lock-in is extreme.

The result is outages like this one.

There's also the question of what reliability is even worth. Verizon's network is objectively excellent most of the time. Coverage is broad, speeds are good, the service is generally reliable. But that excellence is constantly interrupted by occasional catastrophic failures. Customers want both—excellent service and iron-clad reliability. Companies have learned they can deliver excellent service most of the time and get away with occasional huge failures, because the $20 credit gets absorbed as a cost of doing business.

If the FCC actually held carriers to reliable standards—mandating that outages lasting more than an hour resulted in automatic significant credits, for instance—the incentive structure would change. Carriers would suddenly invest heavily in preventing those outages, because the financial pain would be real.

But that regulation doesn't exist. So we get $20.

What This Means for Your Carrier Choice

If you're thinking about switching carriers or renewing a contract, the outage response matters.

It's not just about the specific response to this outage—it's about what the response tells you about the company's values. A company that offers a token $20 credit and moves on is showing you that they don't prioritize reliability. They prioritize profit.

Verizon's network is genuinely solid most of the time. Coverage and speeds are good. But you now know that if a catastrophic failure happens, your compensation will be minimal. You should factor that into your decision.

Other carriers have similar track records. None of them are notably better at this. But some regional carriers or MVNOs might offer better terms or more attentive service. The real answer is that no carrier is perfect, and you should choose based on the tradeoff between network quality, price, customer service, and your tolerance for occasional outages.

For business customers, this is even more critical. If you're dependent on cell service for your business, you need redundancy built in. You might use multiple carriers, maintain a backup internet connection, or work with a provider who can guarantee SLAs backed by meaningful financial penalties. A $20 credit is useless to you.

For individual customers, the practical answer is probably just to accept that outages happen, take the $20 credit, and move on. But you should know that you're accepting an inadequate response and that there are structural reasons why that inadequate response is the industry norm.

The Future of Outage Accountability

Will things change?

The FCC has indicated interest in stricter outage reporting and stronger consumer protection standards. There's bipartisan recognition that telecom infrastructure is critical enough that failures should be taken seriously. That could eventually lead to regulatory changes that actually incentivize reliability.

Class action lawsuits might also push movement. If customers collectively win meaningful settlements, it becomes harder for carriers to justify minimal responses to major outages.

There's also pressure from corporate customers. Businesses losing thousands of dollars per hour during an outage have leverage and incentive to push for better terms. Enterprise-level negotiations might establish new standards that eventually trickle down to consumer service.

But honestly, without significant regulatory change or customer action, the $20 credit is probably what we'll keep seeing. It's the minimum viable response, and until there's real consequence for offering the minimum, companies will keep offering it.

The path to change would involve customers actually switching carriers when they experience major outages, or regulators imposing meaningful penalties for infrastructure failures. Neither seems likely to happen at the scale required. So we probably get more $20 credits in the future.

The Psychological Impact Beyond Money

What's worth noting is that the $20 credit misses the psychological element entirely.

When your service fails completely, there's not just the practical impact—there's a trust issue. You're paying for a service and relying on it being available. When it's not, that undermines the fundamental exchange.

A 12-hour outage makes you realize you're dependent on a system that can fail completely with minimal warning. You can't reach anyone. You can't get information. You're cut off. That's psychologically jarring.

A token credit doesn't address that psychological impact. If anything, it emphasizes it. The company is essentially saying "yeah, this happens, here's $20, get over it." That's not reassuring.

What would actually address the psychological impact is credible evidence of change. Evidence that the company has invested in preventing the failure, that they've thought deeply about how to maintain reliability, that they're taking it seriously. That's not something money can buy, but it's what would actually restore trust.

Verizon's response—a credit without substantive explanation or credible change commitments—fails on this level. Customers are left feeling like the company doesn't really care, just that they're following a script.

That's probably more damaging to Verizon's relationship with customers than the outage itself. People understand that infrastructure fails sometimes. What they can't forgive is the lack of concern about it.

FAQ

What caused Verizon's outage?

Verizon attributed the outage to a technical issue that occurred during a software update to their network infrastructure. The company initially provided limited technical details but later acknowledged that the failure reflected inadequate safeguards in their update process. The outage affected approximately 40 million customers nationwide for roughly 12 hours.

Is the $20 credit enough compensation?

No. For a 12-hour nationwide outage affecting critical communications infrastructure, a $20 credit is inadequate. It represents less than one day of service for most customers and fails to address actual business losses, emergency response delays, or psychological impact of losing service entirely. For business customers with documented losses, the credit is nearly meaningless.

What should I do if I suffered business losses during an outage?

Document everything carefully: the time the service failed, when it was restored, what specific business activities were affected, and any measurable losses (missed sales, delayed services, costs incurred). Submit a claim directly to Verizon's customer service with this documentation. Verizon might negotiate a larger credit for documented business impact. If they refuse, you can pursue a class action lawsuit or file a complaint with the FCC or your state's Public Utilities Commission.

Are other carriers better about outage compensation?

Not significantly. AT&T historically offered similar or smaller credits for comparable outages. T-Mobile required customers to request credits individually rather than offering automatic compensation. Sprint offered slightly higher credits in some cases. The industry norm is essentially the same: minimal credits treated as an acknowledgment rather than meaningful compensation.

What would actually prevent outages like this?

Carrier networks need redundancy designed so that a single failure in any system can't bring down the entire network. This requires duplicated critical equipment, geographic distribution of infrastructure, rigorous testing of software updates before deployment, automatic failover systems, and limits on the scope of changes that can affect the entire network simultaneously. These investments are technically achievable but require significant capital spending that carriers resist without regulatory or market incentive.

Can I switch carriers because of the outage?

Yes, and you should factor outage history into your carrier selection. However, switching involves costs and hassles, and alternative carriers have similar track records. A more practical approach for most customers is to understand the risk, ensure critical communications have backup systems if possible, and make carrier choices based on other factors like coverage, price, and customer service. For business customers, the calculus is different—outage risk should be weighted heavily.

What's the FCC doing about outages?

The Federal Communications Commission has increased focus on carrier outage reporting and response in recent years. The FCC now requires detailed outage reports and investigations of serious failures. There's been discussion about stronger penalties and mandatory service reliability standards, but enforcement remains light compared to international regulators. Future regulatory action could significantly increase financial consequences for outages, which would change carrier incentives around infrastructure investment.

How long do class action lawsuits over outages usually take?

Class action lawsuits against telecom carriers typically take 2-4 years to reach settlement, with litigation often extending longer if it goes to trial. Individual payouts are usually modest—often in the $50-200 range per customer—unless the claim pool is small. The real impact of class actions is signaling that outages have consequences, which might eventually influence carrier behavior more than the payouts themselves.

Conclusion

Verizon's $20 credit is a perfect symbol of modern corporate accountability: it's simultaneously an acknowledgment that something went wrong and an insistence that nothing really needs to change.

The credit costs the company roughly $800 million when distributed across 40 million customers—significant money in absolute terms, but negligible as a percentage of annual revenue. More importantly, it establishes no incentive for Verizon to actually prevent the next outage.

Where that leaves us is clear: if you rely on your cell phone for anything important, you should assume it will fail completely at some point, understand that compensation will be minimal, and plan accordingly. Use backup systems for critical communications. For business purposes, don't rely on a single carrier. Build redundancy into your operations.

The $20 credit tells you exactly how seriously Verizon takes your reliance on their network. It's not very seriously at all.

What actually matters isn't whether Verizon pays

Meanwhile, the regulatory environment might eventually force change. The FCC appears to be moving toward stricter oversight. State regulators are asking harder questions. Class action lawsuits create financial consequences. But unless and until those forces generate real financial pain for carriers, the response to outages will remain the same: a token credit and a promise to "do better."

Until Verizon and other carriers actually invest meaningfully in reliability—until they prioritize preventing outages over quarterly profit margins—we should expect more 12-hour blackouts. And when they happen, we'll get another $20 credit and another statement about moving forward.

The question is whether that's acceptable. For now, the market suggests it is. Customers keep their plans. The company keeps their profit margins. The outage gets absorbed as a predictable cost of doing business.

But there's a better way. It would start with demanding more. Not just from Verizon, but from all carriers. And not just demanding better credits, but demanding better infrastructure. Demanding transparency. Demanding accountability that actually means something.

The $20 credit shows us what we're accepting if we don't demand more. The question is whether enough customers care enough to actually demand it.

Key Takeaways

- Verizon's $20 credit represents less than 2% of a typical customer's monthly bill and fails to compensate for actual losses during the 12-hour outage

- Industry standard is minimal credits ($5-25) treated as acknowledgment rather than meaningful compensation across AT&T, T-Mobile, and other carriers

- The real cost to the economy exceeded 800 million across 40 million customers

- FCC and international regulators like the EU impose much stricter standards, with fines up to 3% of annual revenue for similar failures

- True accountability requires infrastructure investment and structural changes to prevent outages, not token credits that get written off as business expenses

Related Articles

- Verizon Outage 2024: What Happened and Why 911 Failed [2025]

- Verizon Outage 2025: Complete Timeline, Impact Analysis & What to Do [2025]

- Data Sovereignty for SMEs: Control, Compliance, and Resilience [2025]

- Logitech macOS Certificate Crisis: How One Mistake Broke Thousands of Apps [2025]

- Logitech Certificate Expiration Broke macOS Mice: What Happened [2025]

- France's La Poste DDoS Attack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Business [2025]

![Verizon's $20 Credit After Major Outage: Is It Enough? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/verizon-s-20-credit-after-major-outage-is-it-enough-2025/image-1-1768493167611.jpg)