The Global Age Verification Crisis Nobody Signed Up For

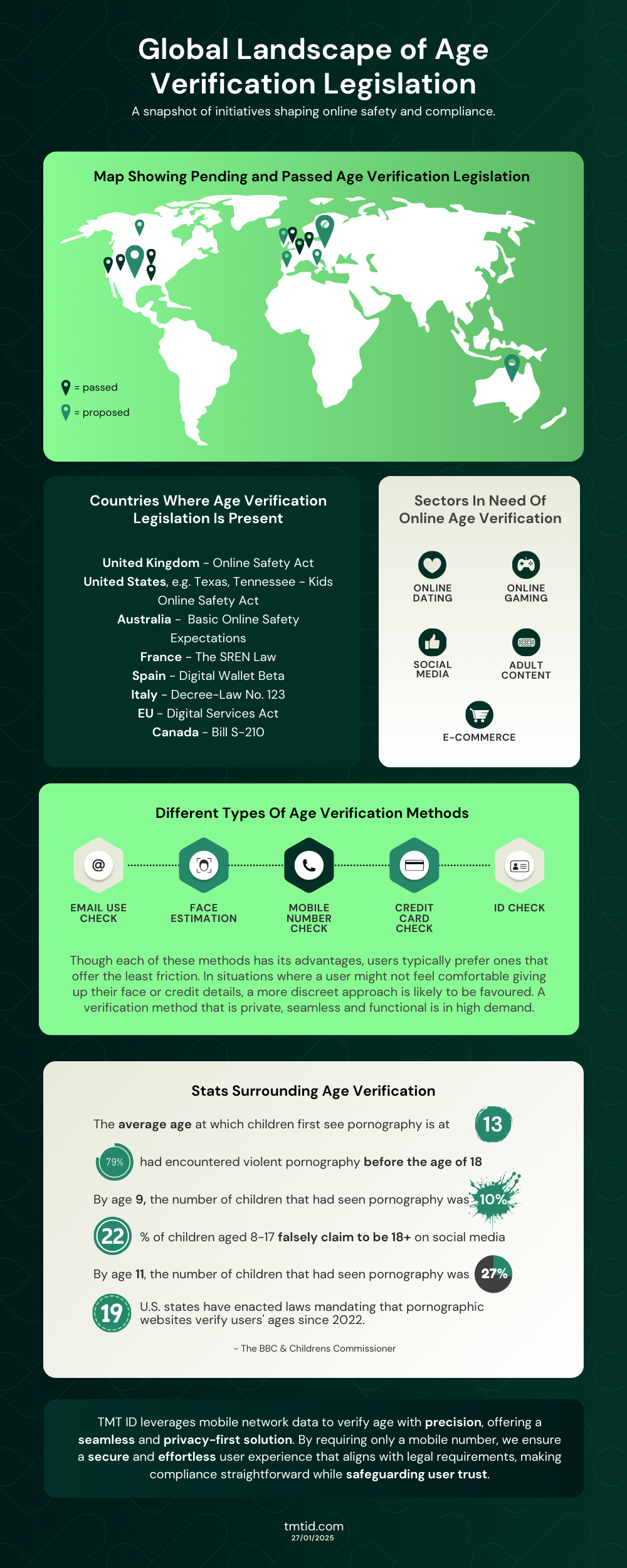

Something shifted in 2024. Governments stopped asking tech companies politely to protect kids and started forcing them to do it through law.

Australia went first. In November 2024, it became the first country to outright ban social media for anyone under 16. No TikTok. No Instagram. No YouTube. No exceptions. The message was clear: tech companies had their chance to self-regulate and failed. What followed wasn't a quiet policy adjustment. It sparked a global domino effect that's still rolling.

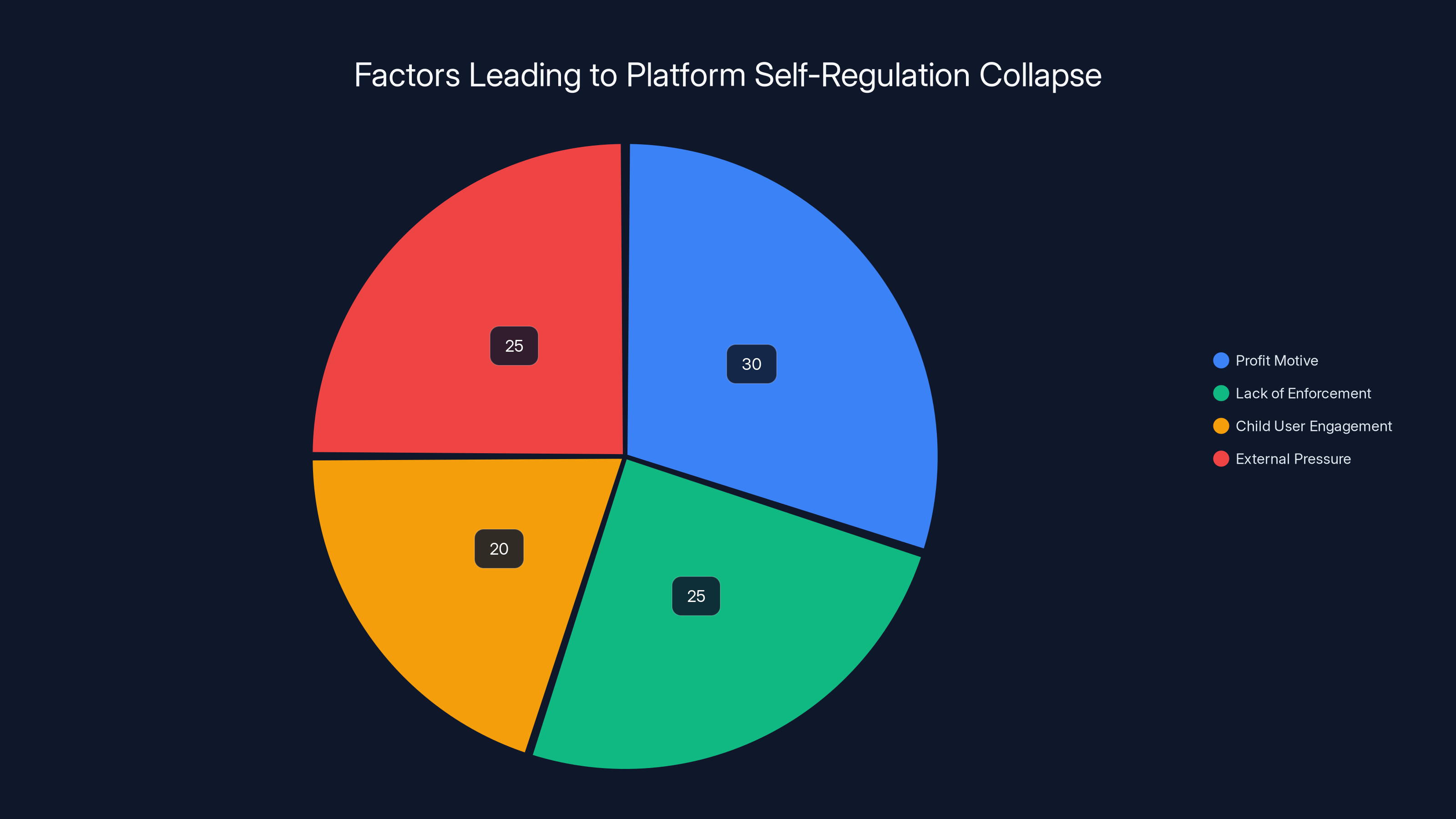

Denmark, Malaysia, and the European Union started drafting similar bans. In the US, 25 states passed age-verification legislation in a single year. The trend isn't slowing down. In fact, legislatures across the globe are on track to pass dozens—possibly hundreds—of new age-verification laws in 2025 and beyond. We're witnessing the collapse of the "platform self-regulation" model in real time.

But here's where it gets messy. Governments demanding age verification and platforms actually delivering it are two different problems. TikTok announced it would roll out age-detection technology across Europe. Chat GPT followed suit with its own age-prediction software. On the surface, this sounds like a reasonable compromise. Nobody gets banned outright. The platform just limits what they can see based on their age. Seems fair, right?

Except it's not that simple. Experts are raising serious concerns about what age-detection actually means: more surveillance, more data collection, more opportunities for bias, and no guarantee it even works. The irony is dark. To "protect" kids, platforms would need to watch them more closely than ever before. And if the system makes mistakes identifying who's actually a kid, the consequences could be severe.

This isn't a simple story of good intentions meeting practical obstacles. It's a fundamental collision between child safety and privacy rights, with every proposed solution creating new problems. Let's dig into what's actually happening, why governments are pushing so hard, what the technical limitations are, and whether any of these approaches actually work.

TL; DR

- The Regulatory Tsunami: Australia banned under-16s from social media entirely; the EU is debating similar measures; 25+ US states now require age verification for online platforms.

- TikTok's "Compromise": Age-detection tech removes accounts from youth feeds without deletion, but requires extensive user behavior surveillance and data collection.

- The Privacy Paradox: To "protect" kids, platforms must watch all users more closely, introducing new security and bias risks for the people they claim to protect.

- Technical Reality Check: Age detection works best with lots of user data; it fails when biased data trains the system; no globally accepted method exists that doesn't compromise privacy.

- The Bottom Line: Every proposed solution trades one risk for another. The question isn't whether age verification works—it's which set of harms society is willing to accept.

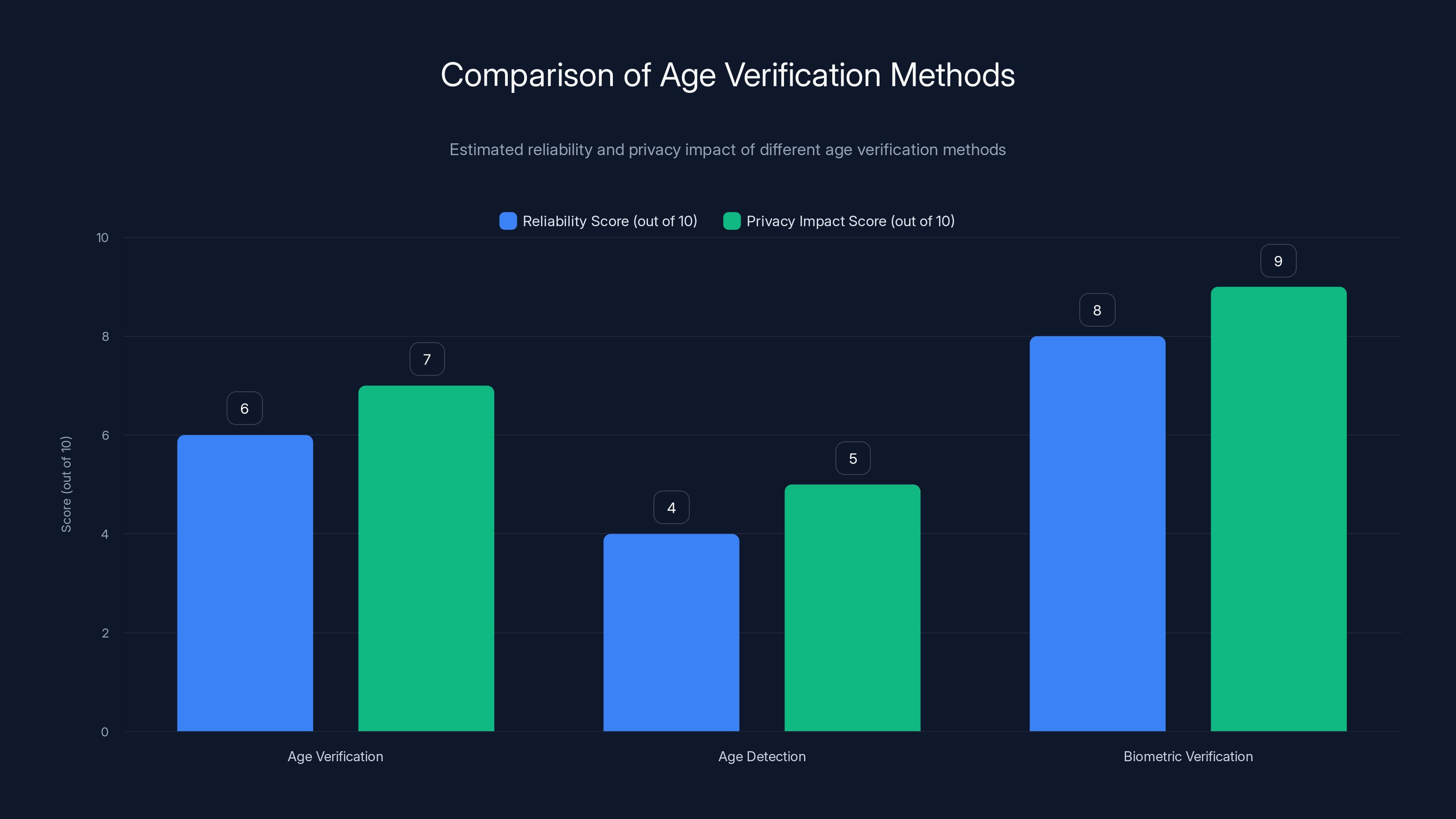

Biometric verification is estimated to be the most reliable but has the highest privacy impact. Age detection is less reliable and has a moderate privacy impact. (Estimated data)

Why Governments Are Finally Pulling the Trigger on Age Bans

The shift from "platforms should self-regulate" to "we're banning you" happened faster than most expected. But the frustration behind it has been building for years.

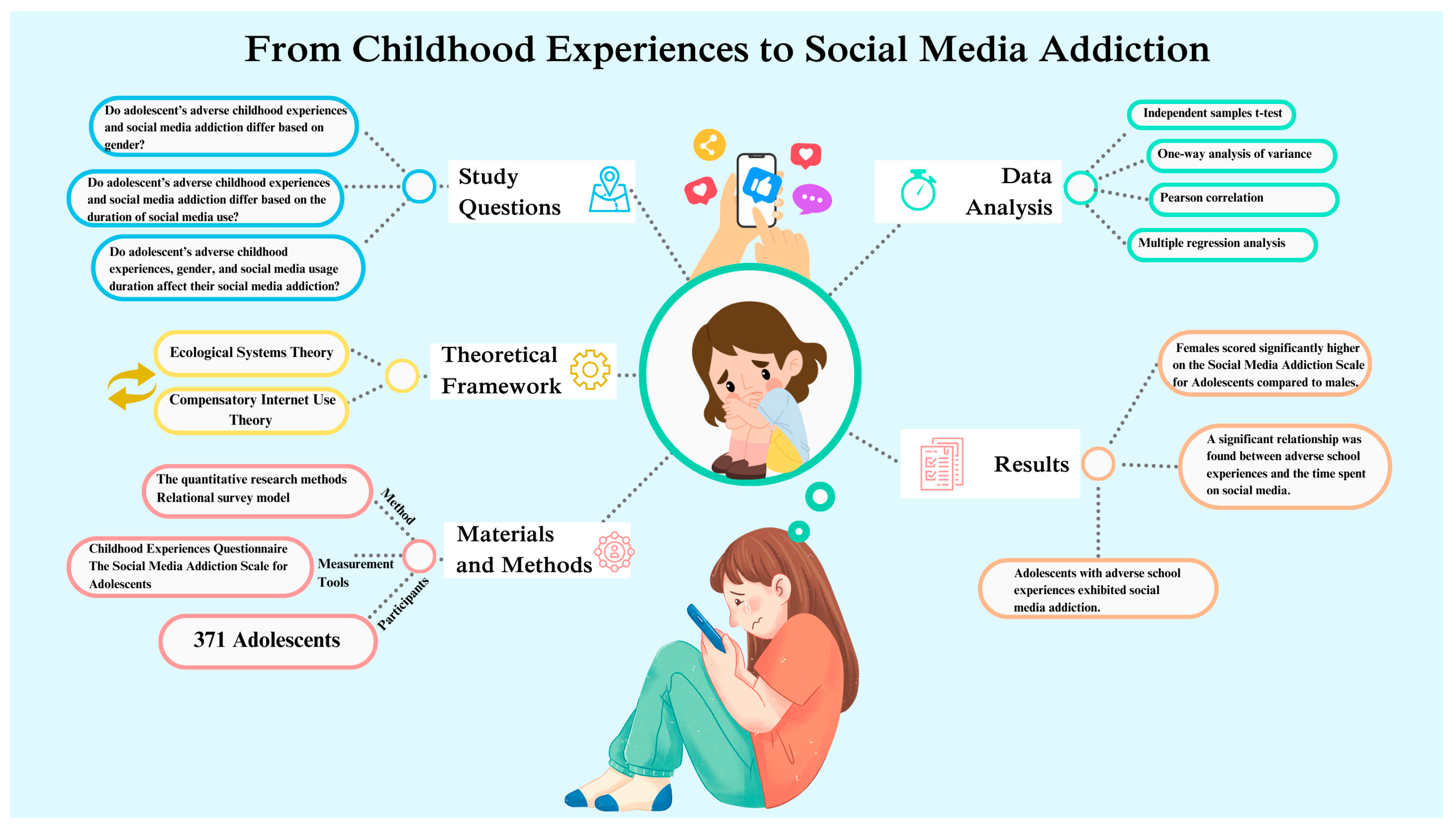

Social media has become something it was never supposed to be: the primary attention infrastructure for children. A kid in 2025 doesn't have a "social media habit." They have a social life mediated entirely through apps. Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, YouTube—these aren't optional anymore. They're where friendship happens, where social status is determined, where self-worth is literally quantified in likes and comments.

And the problem is that these platforms were designed to be addictive. The algorithms don't optimize for child wellbeing. They optimize for engagement. Engagement means watch time, clicks, shares, and interaction. For a 13-year-old struggling with self-image, the algorithm doesn't say, "Maybe you should stop scrolling." It shows them more content that triggers comparison and anxiety, because that's what gets clicks.

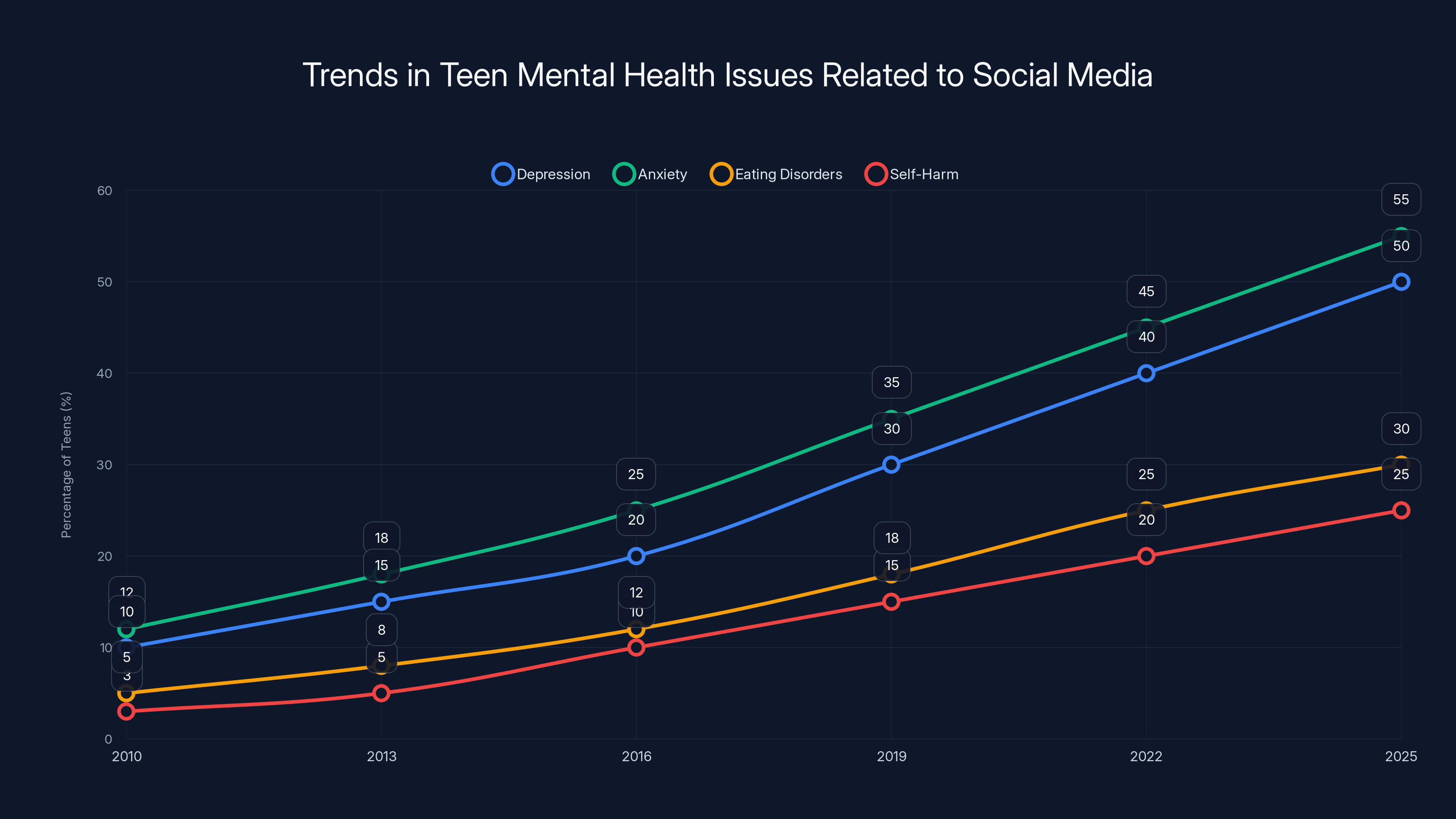

The research backing this up is damning. Mental health professionals have documented spikes in depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and self-harm among teens since Instagram and TikTok became ubiquitous. Are the platforms solely responsible? No. But are they complicit? Absolutely. They built systems that make addiction a feature, not a bug.

Politicians and advocacy groups started asking a simple question: If we know these platforms harm kids, why are we letting companies decide the age limits? Parents signed consent forms nobody read. Platforms claimed they had age verification but didn't. Accounts got deleted and reopened with different details. The system was broken and everyone knew it.

Christel Schaldemose, a Danish lawmaker and vice president of the European Parliament, said it plainly: "We are in the middle of an experiment where American and Chinese tech giants have unlimited access to the attention of our children and young people for hours every single day almost entirely without oversight." That quote captures the frustration exactly. It's not a regulatory nuance. It's an indictment.

Australia's ban wasn't a surprise. It was the inevitable conclusion of years of failed industry promises. The platform companies had the tools to enforce minimum age requirements. They just didn't, because younger users meant more growth and more data to monetize.

Profit motives and lack of enforcement were primary factors in the collapse of self-regulation, but external pressure from studies, parents, and journalists also played a significant role. (Estimated data)

What TikTok Is Actually Doing (And Why It Matters)

TikTok's response to regulatory pressure has been craftier than a simple age ban. Instead of removing accounts, the platform introduced age-detection technology that repositions younger users' content in the algorithm rather than deleting their accounts outright.

Here's how it works in theory. TikTok's system analyzes user behavior, content consumption patterns, interaction history, and device metadata to make inferences about whether an account likely belongs to someone under 18. If it identifies a probable minor, the algorithm changes. The account doesn't disappear. But the content they see gets filtered. They're bumped out of recommendation algorithms that might expose them to harmful material. Their own uploads don't get boosted to broader audiences. It's a soft restriction rather than a hard ban.

On the surface, this seems better than Australia's sledgehammer approach. Fewer disrupted lives. Fewer kids getting banned and then secretly reopening accounts under different names. More nuance. More fairness to the edge cases—like a 15-year-old who's genuinely old enough to handle the platform responsibly.

But that's where the "compromise" language breaks down.

TikTok's age-detection system requires the platform to collect, analyze, and act on behavioral data at a scale most people don't understand. The company needs to know what you watch, how long you watch it, which accounts you follow, what you like, what you search for, when you're online, how you interact with different content types. Feed this data into a machine learning model trained to spot patterns associated with young users, and you can make educated guesses about age.

But here's the problem: "educated guesses" aren't certainties. They're probabilities. And when you're running a system that restricts access based on probabilities, false positives and false negatives become features, not bugs.

Eric Goldman, a law professor at Santa Clara University and a vocal critic of age-verification mandates, calls this approach a "segregate-and-suppress" law. It's segregating users based on inferences about who they are, then suppressing their platform access based on those inferences. The problem is that when the system makes mistakes—and it will—the consequences can be severe.

Imagine you're a 22-year-old who uses TikTok primarily to watch dance videos and cat content. The algorithm flags your account as probable minor. Suddenly, your reach tanks. Your videos don't get promoted. You see restricted feeds. You try to verify your age to fix the error, but the process requires submitting identification documents that get stored somewhere in TikTok's systems. Meanwhile, you're locked out of a platform where you've built a small community of followers.

Alice Marwick, director of research at the nonprofit Data & Society, explains the risk clearly: "This will inevitably expand systematic data collection, creating new privacy risks without any clear evidence that it improves youth safety. Any systems that try to infer age from either behavior or content are based on probabilistic guesses, not certainty, which inevitably proceed with errors and bias that are more likely to impact groups that TikTok's moderators do not have cultural familiarity with."

Translate that: The system will make mistakes. And the mistakes will disproportionately harm marginalized users—LGBTQ+ teens, users from non-Western cultures, users with disabilities, people using language patterns the AI wasn't trained to recognize.

The Surveillance Trade-Off Nobody Explicitly Agreed To

This is the core tension that makes the whole "compromise" framing collapse.

To keep kids safe from social media harms, TikTok needs to identify who the kids are. To do that accurately, it needs extensive behavioral data. But collecting and analyzing that data is itself a form of harm. You're creating detailed digital profiles of minors based on their online behavior. You're training machine learning systems to predict sensitive information (age, location, interests, vulnerabilities) about them. You're storing that data, which means it can be breached, subpoenaed, sold, or misused.

The question that nobody's seriously asking: Which is worse—letting a 13-year-old access TikTok, or building a comprehensive behavioral profile of a 13-year-old to prevent them from accessing TikTok?

Both involve risk. One is the risk of exposure to algorithmically amplified content. The other is the risk of exposure to data harvesting and surveillance infrastructure. The second one's just more invisible.

Goldman points out another layer of hypocrisy: "If the goal of age verification is to keep children safer, it is cruelly ironic to force children to regularly disclose highly sensitive private information and increase their exposure to potentially life-changing data-security violations." He made this point in testimony before New Zealand's Parliament. And he's right. You're asking kids to trade one risk (algorithmic exposure) for another (surveillance and data breach risk). That's not a compromise. That's a substitution.

The encryption community has been warning about this for years. If you build a system capable of detecting kids and restricting their access, you've built a system capable of tracking kids. Every affordance you create for "protecting" users can be weaponized for control. Want to verify age? Now you need identity verification infrastructure. Want to enforce that verification? Now you need persistent tracking. Want to scale that tracking globally? Now you need centralized databases of personal information.

Each step adds capability that can be repurposed. History shows that surveillance infrastructure, once built, tends to get abused. It outlives its original justification.

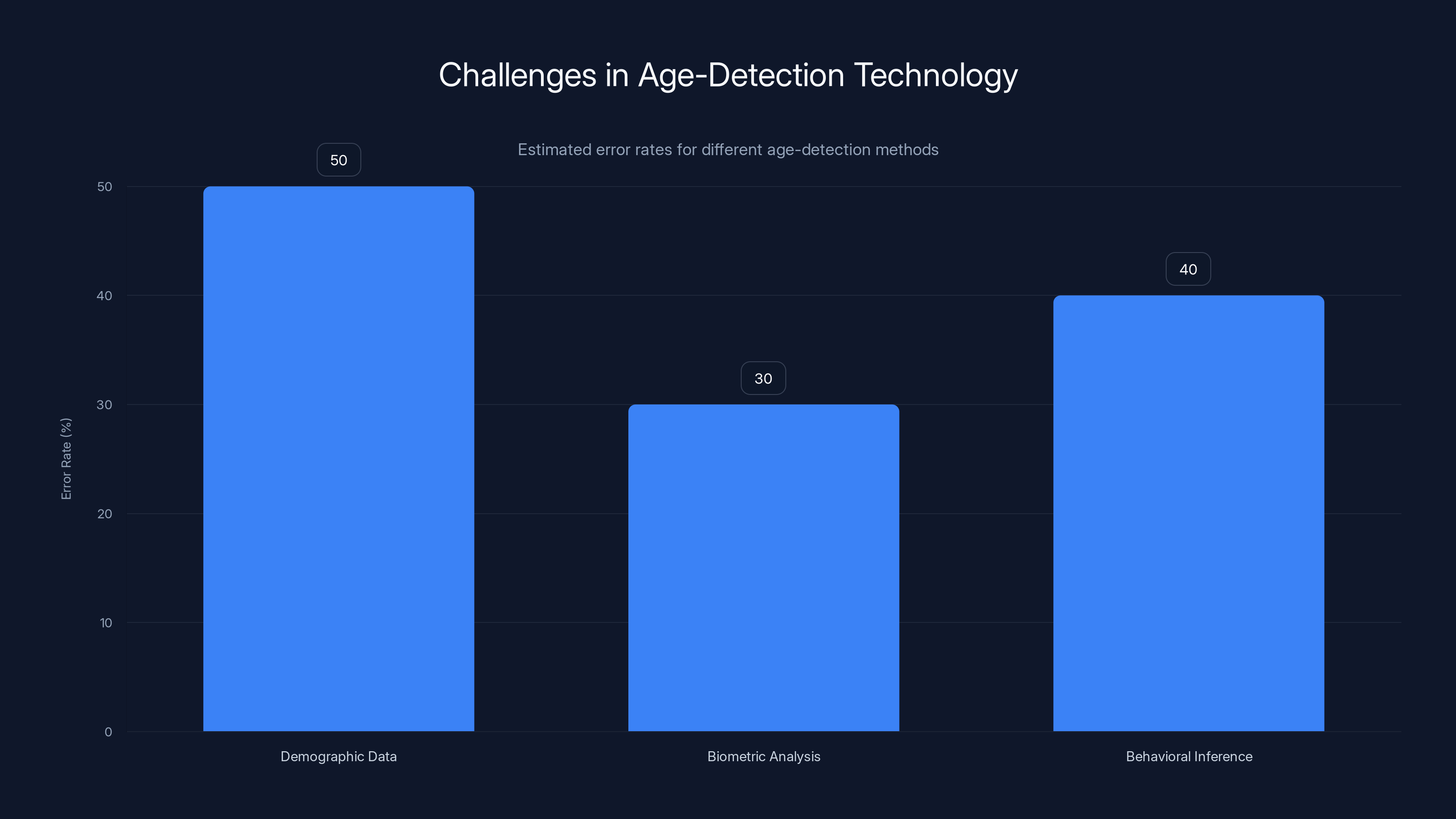

Demographic data has the highest error rate due to user dishonesty, while biometric analysis and behavioral inference also face significant challenges. Estimated data.

How Age-Detection Technology Actually Works (And Why It Fails)

Let's get into the technical weeds, because this is where the promises fall apart.

Age detection typically relies on one of three approaches: demographic data that users voluntarily provide, biometric analysis of facial features or voice patterns, or behavioral inference based on activity patterns.

Voluntary demographic data is the easiest and least invasive. You ask users their birthdate. But this fails immediately because kids lie. They've always lied about their age on the internet. It's probably the first digital fraud most humans commit. Requiring honest age data assumes a level of good faith that's never existed online.

Biometric analysis sounds more sophisticated but introduces different problems. If a platform tries to verify age through facial recognition, you're asking users to submit photo IDs or take selfies. Now you've got a database of facial data linked to age information. That's valuable data for identity theft. That's also a massive privacy violation. Most privacy-forward jurisdictions explicitly restrict this kind of biometric collection, especially from minors.

Behavioral inference is what TikTok is using. The system analyzes patterns in how you use the platform. Do you watch content that appeals to teens? Do you follow accounts associated with youth culture? Do you use slang or references that are generation-specific? Do you engage at times when teenagers are typically online (after school, late at night)? Do you use devices or operating systems more common among minors? Feed all this into a machine learning model, and you can make probabilistic guesses about age.

The problem is that all these patterns have enormous error rates. A 35-year-old who loves youth culture will trigger the same signals as a teenager. Someone from a different country or culture will have different behavioral patterns that the model might misinterpret. Someone on the autism spectrum might have engagement patterns that don't fit the training data. Someone using a VPN or different device than usual breaks the device fingerprinting logic.

And here's the critical issue: these systems are trained on historical data. The training data reflects how the platform has historically categorized users by age. But that categorization itself is biased. TikTok's moderation teams are disproportionately based in specific geographic regions. Their cultural familiarity skews toward certain demographics. When you train an age-detection model on that biased historical data, you're encoding those biases into the system.

The result? The system will reliably detect age in users who match the demographic profile of the training data. It will fail for users who don't match that profile.

Marwick's warning about this is precise: "Probabilistic guesses inevitably proceed with errors and bias that are more likely to impact groups that TikTok's moderators do not have cultural familiarity with." That's not speculation. That's based on how machine learning systems actually behave.

For age-detection systems, a false positive (flagging an adult as a minor) creates a restrictive effect. A false negative (missing an actual minor) defeats the entire purpose. Most systems are tuned to minimize one or the other, which means accepting higher rates of the opposite error.

TikTok's UK pilot acknowledged removing thousands of under-13 accounts. But it also acknowledged (in a quietly buried part of their statement) that "no globally accepted method exists to verify age without undermining user privacy." That's not them being honest about limitations. That's them admitting the whole approach has a fundamental flaw.

The Global Regulatory Landscape: Who's Doing What

The regulatory response to social media and minors is fragmenting into a few distinct approaches, and they're on a collision course.

Australia's Nuclear Option: Complete ban for under-16s. This is the simplest policy. No TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, or platforms designed to be addictive. The platform companies must verify age or face fines. Technically, it's hard to enforce. Socially, it's disruptive. But it's unambiguous. Either you're 16 or older, or you're off the platform. No gray areas. No probabilistic guesses.

Europe's Regulatory Framework: The EU is moving toward mandatory age restrictions with parental consent requirements for younger users. They're not saying ban them, but regulate them with consent mechanisms. This creates an opportunity for age-verification solutions, because if you can verify age, you can enable parental consent flows. It's more complex than Australia's approach but less blunt.

The US Patchwork: 25 states have passed some form of age-verification or age-appropriate design legislation. But they're not all the same. Some require age verification. Some require age assurance. Some require platforms to consider child safety in design. Some require transparent algorithmic systems for minors. It's a fragmented mess that's going to force platforms to develop multiple compliance paths.

Asia-Pacific's Mixed Approach: Malaysia, Thailand, and other countries are debating restrictions. Some lean toward bans (following Australia). Others lean toward industry self-regulation with government oversight. It's still unsettled.

The challenge is that each jurisdiction thinks its approach is the right one. Australia's ban is popular with their voters. The EU's consent framework is more privacy-protective than age verification. The US's patchwork is more flexible. But they're incompatible. A platform can't follow all of them simultaneously.

Which creates a problem: Most likely, platforms will follow the strictest jurisdiction's rules globally. If Australia requires verification, most companies will implement age verification for all users to maintain a unified system. If the EU requires consent, that becomes global. If the US requires algorithmic transparency, that spreads.

The unintended consequence? Global regulatory pressure from the strictest jurisdiction pulls everyone toward more surveillance, more verification, more data collection. The best privacy standards get undermined by the worst.

Lloyd Richardson, director of technology at the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, observed this dynamic: "Historically, the internet was borderless and no-holds-barred. But we're starting to see a shift now." He's right. The internet's regulatory fragmentation is forcing global platforms to choose which jurisdiction's rules to follow. Usually, they choose the strictest, which means imposing the most restrictive rules on everyone.

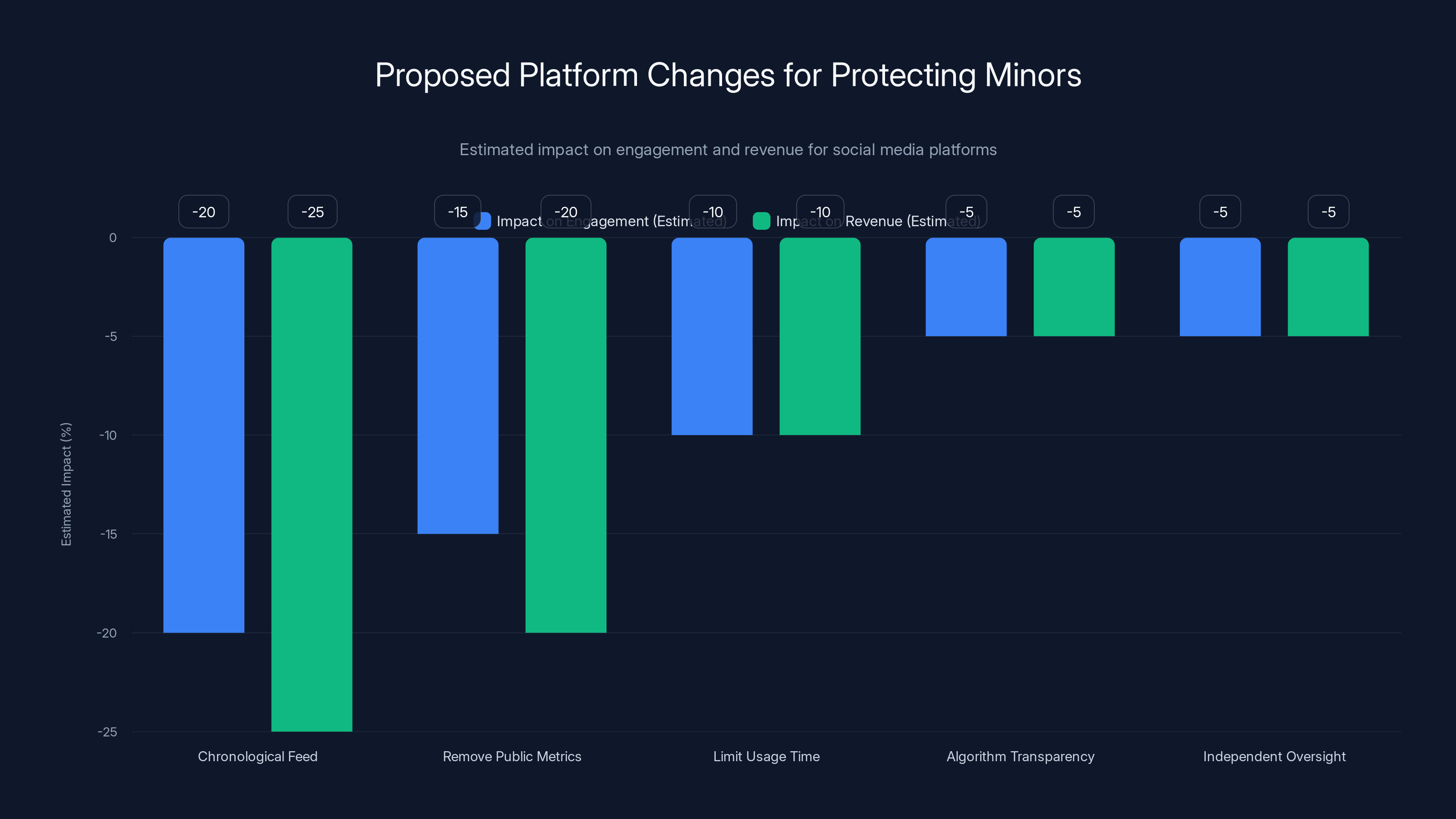

Implementing these changes could significantly reduce engagement and revenue, with chronological feeds and removal of public metrics having the largest estimated impact. Estimated data.

The Parental Consent Problem (And Why It Doesn't Work)

Many regulatory proposals include a carve-out: parents can consent to their kids using the platform. This seems reasonable. If your parents say it's okay, you should be able to use social media.

Except this doesn't work either, and for multiple reasons.

First, there's the implementation problem. To get parental consent, you need to verify that the person consenting is actually the parent. That requires identity verification of adults. Most people don't want to provide government ID to social media companies. But if platforms need parental consent, they need to verify who's giving it. That's another layer of surveillance infrastructure.

Second, there's the assumption problem. The models assume parents always have their kids' best interests in mind and are informed about the risks. That's not universally true. Some parents don't understand the harms. Some parents coerce their kids into sharing data. Some parents aren't available to give consent (single parents with work commitments, parents in difficult family situations). You're creating a system that assumes a family structure and a level of parental engagement that doesn't exist in many households.

Third, there's the consent problem. Once given, can it be withdrawn? Who controls the revocation process? If a kid wants to stop using a platform and the parent consents, does the platform delete their data? Most platforms say "We'll delete the account but keep the data for legal/security reasons." That's not really consent revocation. That's data retention with account deletion.

And finally, there's the incentive problem. Platforms profit from younger users. Parents consenting to platform use doesn't change the underlying business model. The algorithm still optimizes for engagement, not wellbeing. Parental consent just shifts the liability from "we should have verified age" to "parents agreed to this." It's a liability reduction strategy dressed up as a safety mechanism.

Richardson puts it directly: "We shouldn't put the trust of what's developmentally appropriate into the hands of big technology companies. We need to look at developmental experts to answer those questions." He's arguing that instead of platforms deciding what's appropriate (with parental consent as a backstop), we should have independent developmental experts defining what's safe. That's a fundamentally different model than consent-based systems.

Why Platform Self-Regulation Collapsed (And Why Companies Enabled It)

Here's a question worth asking: Why are governments suddenly forcing this issue when social media companies have claimed to have age verification for years?

Because platforms never actually cared. They claimed to enforce minimum ages, but enforcement was theater. A user enters a birthdate, and if it says they're over 18, they're in. No verification. No checking. No consequence for lying. The minimum age existed on paper and in terms of service, but not in practice.

Why? Because child users were profitable. They represented growth when adult markets were saturating. They generated engagement. They created data. Enforcing a minimum age meant turning away revenue.

TikTok explicitly knew this. Internal documents revealed that the company's moderation systems were weak specifically because stricter enforcement would reduce engagement. Instagram knew it. YouTube knew it. Every platform with a growth problem knew that their younger user base was driving metrics that mattered to investors.

Self-regulation assumed that companies would voluntarily choose child safety over profit. That assumption was always absurd. For a business whose survival depends on quarterly growth, child safety is a cost. It reduces revenue. The profit motive and the safety mandate are in direct conflict. The profit motive always wins when left to internal decision-making.

The only thing that changed is that enough evidence accumulated that child mental health was suffering. Enough parents and advocates raised enough noise. Enough studies showed correlation between social media use and depression/anxiety. Enough schools and pediatricians reported problems. Enough journalists published investigations. And finally, enough voters in key countries supported regulation that politicians had political capital to push.

But the companies are still trying to minimize the impact. They're offering age-detection rather than bans because bans are more expensive (reduced revenue) and more obvious (easier to enforce and monitor compliance with). Age-detection sounds good, looks good, and doesn't actually prevent minors from using the platform if they lie or use multiple accounts.

TikTok's statement about no globally accepted method for age verification? That's not an acknowledgment of limitation. That's a strategic argument. They're saying, "See? This problem is hard. Our imperfect solution is the best available." It's not. It's the best available solution that still lets them retain younger users while appearing to comply with regulation.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in mental health issues among teens correlating with the rise of social media platforms. The trend highlights the urgency for regulatory measures.

The Bias and Discrimination Trap

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: age-detection systems will discriminate, and we can predict roughly how.

AI systems trained on data inherit and amplify the biases in that data. TikTok's moderation teams (the humans who label training data) are geographically concentrated. They don't have cultural familiarity with all user groups. When they label accounts as "young user," they're making judgments based on content, language, behavior, interests. Those judgments reflect their own cultural context.

A user from Southeast Asia who uses slang common in their region? The system might flag that as youth-associated slang. A user who's part of a subculture or identity group that uses specific language patterns? Flag. A disabled user who has different engagement patterns? Flag. A user who's neurodivergent and interacts with platforms differently? Flag.

The error rate won't be uniform across demographics. It will be systematically higher for users who aren't represented in the training data or whose behavior patterns don't match what the training data indicates about their age group.

Who gets harmed? Marginalized users. The exact people who need platform access most, because online communities often provide support for minorities who don't have local representation.

And the irony? These are the groups that platforms have historically moderated most aggressively. The moderation teams already have lower cultural familiarity with their content. An age-detection system trained on that historical data will perpetuate and amplify those biases.

Marwick's research at Data & Society has documented this repeatedly. Moderation systems and AI systems in general perform worse on content from marginalized groups. An age-detection system layered on top of existing moderation systems compounds the problem.

Chat GPT's Approach: The Slightly Different Version

Chat GPT's age-prediction system is worth discussing separately, because it's a different implementation with its own problems.

Chat GPT announced it would roll out age-prediction software to determine whether accounts likely belong to someone under 18. The goal is to apply stricter safeguards to accounts flagged as probable minors. The system uses similar behavioral inference methods but operates differently because Chat GPT has different data.

Open AI doesn't have years of TikTok-style engagement data showing watch time, follow patterns, and algorithmic interactions. They have conversation history, query patterns, and usage metadata. The age-prediction system looks at things like:

- Query topics (Are you asking questions typical of teenagers?)

- Language patterns (Slang, references, vocabulary)

- Knowledge gaps (Do your questions suggest adolescent knowledge level?)

- Search behavior (What are you trying to learn about?)

- Time of usage (When are you typically online?)

This is inference based on much thinner data, which means higher error rates. It's also more obviously invasive in some ways. You're analyzing the content of conversations to infer age. That's privacy violation bordering on psychological profiling.

And it has the same problem: probabilistic guesses with systematic bias. Someone asking Chat GPT questions about physics at 2 AM might be a college student or an insomniac kid. Someone using 2000s slang might be Gen Z or might be an older user who's culturally engaged. The system can guess, but it won't know for certain.

Open AI's approach is less obviously surveillance-heavy than TikTok's (less behavioral tracking over time), but it's more obviously intrusive into content (analyzing conversations themselves). Different trade-off. Still problematic.

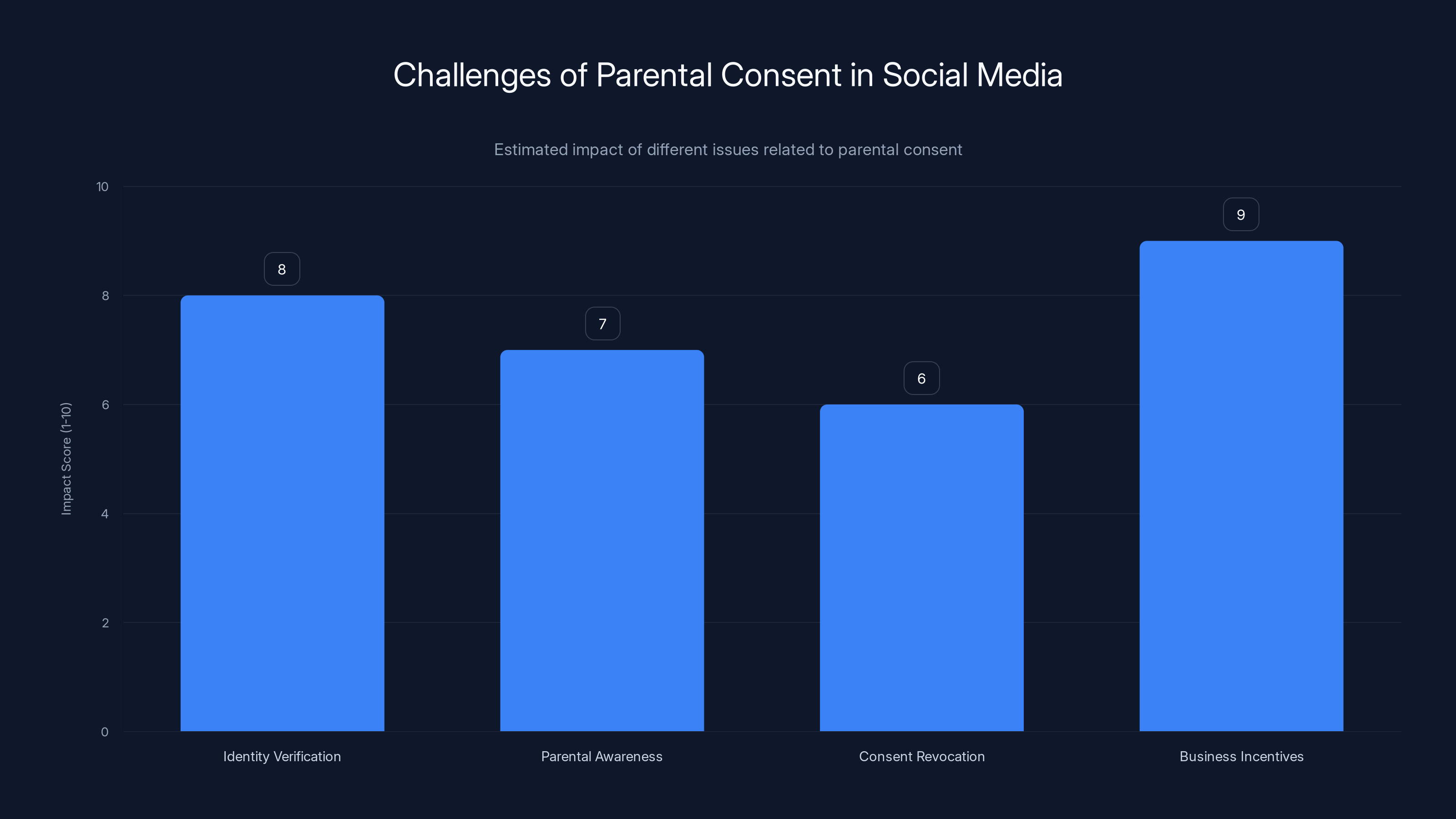

The chart highlights major challenges in implementing parental consent for social media use, with business incentives being the most impactful issue. (Estimated data)

The Hard Question: Does Any Of This Even Work?

Let's step back to the core question that everyone's dancing around: Do age-verification and age-detection systems actually protect children?

The honest answer is: We don't know yet, and evidence is weak.

Australia's ban is too new to have data on outcomes. TikTok's pilot removed accounts but didn't measure whether that actually improved child safety. Chat GPT's system is still rolling out. There's no comprehensive study showing that age verification reduces harm to minors.

What we do know:

- Kids determined to use a platform will lie about age, use a parent's account, or access through a VPN.

- Age-detection systems have high error rates and systematic bias.

- Enforcement is difficult at scale.

- The surveillance infrastructure required creates new harms.

- No system is "child safe" if the underlying platform is algorithmically optimized for engagement.

In other words, solving age verification doesn't solve the actual problem. Even if you perfectly blocked everyone under 16 from TikTok, Instagram is still optimizing for engagement over wellbeing. YouTube's algorithm is still prioritizing watch time. Snapchat is still designed to be compulsive.

Age verification is a proxy solution to a design problem. The real issue isn't that kids shouldn't be on social media. The real issue is that social media is designed in ways that harm everyone, especially people whose brains are still developing.

The proper solution isn't age verification. It's platform redesign. Algorithmic transparency. Limiting engagement-based recommendations. Removing metrics that gamify self-worth. Building systems for healthy use rather than compulsive use.

But that would cost platforms revenue. So instead, governments are pushing age verification, platforms are implementing it in ways that maximize data collection and minimize actual protection, and everyone pretends this solves the problem.

It doesn't. It just makes the problem younger and more surveilled.

The Future: Where This Is Actually Heading

If current regulatory trends continue, here's the most likely future:

In 3-5 years, most major platforms will implement some form of age-detection or age-verification system. It won't be because they care about child safety. It will be because regulators in major markets mandate it, and it's cheaper to implement globally than to maintain different systems per jurisdiction.

These systems will use behavioral inference, device fingerprinting, and account analysis to identify probable minors. They will have high error rates. They will disproportionately affect marginalized users. But they'll be good enough to show governments they're "doing something."

Parallel to this, governments will build centralized age-verification infrastructure. Some jurisdictions will use national ID databases. Others will require platforms to store identity information. This creates a permanent registry of who's using what online—a surveillance infrastructure that will outlast whatever child-safety justification created it.

Companies will resist the most invasive systems (centralized ID databases) and push for the least invasive that still technically comply (behavioral inference). The compromise will land somewhere in the middle, more invasive than current systems but less invasive than governments ideally want.

Users will adapt by lying more effectively, using multiple accounts, borrowing adult accounts, or using VPNs and proxies. Tech-savvy minors will always find workarounds. Less tech-savvy users—often lower-income, rural, or from less-developed countries—will be more blocked and more surveilled.

The real losers will be:

- Marginalized communities who rely on online spaces for support and identity.

- Privacy advocates who opposed surveillance infrastructure.

- Casual users incorrectly flagged by imperfect systems.

- Anyone whose behavioral data gets swept up in the verification infrastructure.

The real winners will be:

- Platform companies (compliant with regulation, maintained revenue, reduced liability).

- Authoritarian governments (new surveillance infrastructure).

- Identity verification companies (contracts to build the systems).

- Surveillance capitalism (more data collection normalized).

The actual solution—platforms being redesigned around wellbeing rather than engagement—will be deprioritized. It costs money. It reduces growth. Governments won't mandate it because politicians don't understand platform design. Platforms won't do it voluntarily because profit motive prevents it.

Age verification will be implemented. It won't work well. But it will exist, and once it exists, it won't go away.

Who Wins and Loses in Each Regulatory Approach

Different regulatory models create different outcomes. Let's be specific about who benefits and who pays the cost:

Total Bans (Australia Model)

Winners: Parents who want kids off social media; privacy advocates (less data collection); politicians looking tough on tech; teenagers who want to quit but face peer pressure.

Losers: Teenagers who use platforms for support communities; users with disabilities who rely on online spaces; creators who monetize through platforms; platform companies; countries with looser enforcement (teens will just use VPNs).

Trade-off: Clear rule, but blunt. Completely excludes minors instead of protecting them.

Age-Verification with Restrictions (TikTok/EU Model)

Winners: Platform companies (revenue maintained, reduced liability); governments (compliance theater); identity verification vendors (new contracts).

Losers: Privacy advocates; users incorrectly flagged as minors; marginalized communities with higher false-positive rates; anyone whose behavioral data gets harvested for age inference; teenagers who use the platform safely.

Trade-off: Graduated restrictions instead of total ban, but massive expansion of surveillance infrastructure.

Consent-Based Models (Some US States)

Winners: Parents (theoretical control); platform companies (depends on implementation); lawyers (liability arguments about whether consent was informed).

Losers: Parents who can't monitor effectively; teenagers in unsupportive families; users whose consent doesn't actually control anything; privacy advocates.

Trade-off: More flexibility, but relies on parental involvement that doesn't always exist.

Algorithmic Transparency Mandates (Some US States)

Winners: Researchers; transparency advocates; users who understand systems; competitors to major platforms (level playing field).

Losers: Platform companies (competitive secrets revealed); users who don't understand algorithms; advertisers (less ability to optimize targeting).

Trade-off: Addresses root cause instead of symptoms, but requires users to be sophisticated enough to understand the data.

None of these models are perfect. Each trades something for something else. The question is which trade-offs society finds acceptable.

What Platform Companies Are Actually Saying (And What They're Not Saying)

When you read TikTok or Meta or Google's official statements about age verification, notice what's conspicuously absent:

They never say: "We're implementing this because we believe it's the best way to protect children."

They always say: "We're implementing this because it's required by law" or "We're implementing this to show we're responsible." Sometimes they'll add language about "seeking input from child safety experts" and "rigorous testing" and "privacy-preserving approaches."

This matters because it's honest. They're complying with regulation, not leading on safety. They're not doing this because they think it's right. They're doing it because regulators are forcing them.

Which is fine. Companies will respond to regulation. But it means when they claim to have "privacy-preserving" age verification, they mean "as invasive as we can get away with while still seeming privacy-conscious." They mean the minimum viable implementation that satisfies regulators.

It's the same dynamic as environmental regulation. Companies don't reduce emissions because it's right. They reduce emissions because law requires it. And they reduce them to the minimum level required, not to the level that would actually be optimal for the environment.

Understanding this changes how you interpret platform statements. When TikTok says "no globally accepted method for age verification exists," they're not sadly acknowledging limitation. They're strategically arguing against stricter requirements. When they say their system is "privacy-preserving," they mean it preserves privacy relative to alternative systems, not relative to ideal privacy.

The Privacy Advocates' Counterargument (And Why They're Right To Be Concerned)

The most coherent opposition to age-verification systems isn't coming from anti-regulation libertarians. It's coming from privacy organizations, academic researchers, and civil liberties advocates.

Their argument is straightforward: Every surveillance infrastructure built today gets repurposed tomorrow. Age verification requires building systems to track online behavior and infer sensitive personal information. Those systems don't disappear when the original justification fades.

History supports this. Laws passed for temporary emergency purposes (like airport security after 9/11) become permanent. Databases built for one purpose (tax collection) get repurposed (law enforcement). Tools created for one surveillance goal expand to another.

Imagine you're 20 years old in 2045. Government uses age-verification infrastructure for other purposes. Insurance companies access age-verification data to determine who's a minor making decisions about their health (and thus not liable). Law enforcement accesses it to find juveniles in different jurisdictions. Advertisers access it to profile users. Political campaigns access it to target swing demographics.

None of this requires new law. It just requires decision-makers to realize the infrastructure is there and find new uses for it. That pattern has played out repeatedly with surveillance tools.

Privacy advocates are saying: Don't build the infrastructure, even with good intentions, because once built it will be abused. That's not paranoia. That's pattern recognition based on history.

The counterargument from child-safety advocates is: But children are being harmed now. We can't wait for perfect systems. We have to act.

Both are right. Children are being harmed. And surveillance infrastructure will be abused. The question is which harm is worse, and whether there are solutions that address one without enabling the other.

That's the actual policy question nobody's seriously asking.

Toward a Better Solution (That Probably Won't Happen)

If you wanted to actually protect children without building permanent surveillance infrastructure, what would you do?

You'd focus on design rather than surveillance. You'd require platforms to:

-

Eliminate engagement-based recommendations for users under 18. If you're under 18, you get a chronological feed, not an algorithmic one. You see accounts you follow, in the order they post. No algorithm optimizing for watch time.

-

Remove metrics that gamify self-worth. No public like counts (likes exist for the algorithm but aren't displayed). No comment ratios. No follower counts. No viral potential. Users can see engagement, but it's not public and therefore not a source of social comparison.

-

Limit daily usage time for accounts flagged as probable minors. Not a hard ban, but a reminder system that nudges toward healthier usage. After 60 minutes, a notification: "You've been scrolling for an hour. Take a break?"

-

Require algorithmic transparency reports. Platforms publish data on how their algorithms treat minors. What content is recommended? How often? What triggers high engagement? This data goes to researchers, not to the public, but it creates accountability.

-

Establish independent oversight boards with developmental experts. Not platform-appointed boards with token external members, but genuinely independent bodies with subpoena power and authority to mandate changes.

None of this requires age verification. None of this requires behavioral inference or surveillance. All of it addresses the actual mechanism of harm (algorithmic amplification designed for engagement) rather than treating the symptom (kids accessing platforms).

But none of this would happen voluntarily because all of it reduces engagement and revenue. Platforms would need regulation mandating it. And that regulation would be more technically complex and harder to enforce than simple age verification.

So instead, governments will implement age verification because it's simple and visible. They'll point to thousands of accounts removed as evidence of progress. Platforms will comply because the cost is manageable and the liability reduction is real. And the actual mechanisms of harm will continue unchanged.

The Bottom Line: There Is No Perfect Answer

Here's what we know:

- Social media harms children. The evidence is overwhelming.

- Platform companies have failed to self-regulate. That's demonstrated empirically.

- Regulation is necessary. Waiting for voluntary change isn't an option.

- Every proposed solution creates new problems while solving old ones.

- Age verification looks better than total bans but expands surveillance.

- Total bans are clearer but more disruptive and less effective (kids will find workarounds).

- Consent-based systems require parental engagement that doesn't always exist.

- Algorithmic transparency and design-based solutions would be better but are harder to implement and regulate.

TikTok's age-detection approach is a reasonable compromise between total prohibition and current laissez-faire approaches. But calling it a "compromise" is generous. It's a trade-off. You get graduated access restrictions in exchange for normalized behavioral surveillance. Neither outcome is obviously better. They're just different risks with different beneficiaries.

The real problem is that all proposed solutions treat the symptom instead of the disease. The disease is that social media is designed to be addictive and to amplify engagement over wellbeing. The symptom is that kids are being harmed. You can restrict kids' access without changing the underlying design, but that doesn't address why access is harmful in the first place.

What probably happens: Governments will implement some form of age verification or design-based restrictions. Platforms will comply to the minimum required. Teenagers will continue using platforms (many will find workarounds, others will be restricted). The surveillance infrastructure will exist and persist. Developers will optimize for compliance rather than safety. And in 10 years, we'll realize the system didn't work as intended but the infrastructure remains.

That's not a prediction. That's the historical pattern.

The only way different happens is if either:

- Platforms voluntarily redesign around wellbeing (won't happen without regulation, and regulation will probably create perverse incentives).

- Regulators mandate design changes in addition to age verification (possible but requires technical expertise many regulators lack).

- Cultural shift away from social media reduces demand (generationally possible, not happening in next 5 years).

Until one of those happens, every solution will be partial. Every implementation will create new problems. And the only certainty is that the surveillance infrastructure will remain even after the original justification fades.

That's the uncomfortable reality underneath all the rhetoric about protecting children.

FAQ

What exactly is age verification and how is it different from age detection?

Age verification confirms someone's actual age through identity documents or government databases. Age detection makes probabilistic guesses about age based on user behavior, content consumption, and other signals. TikTok's system is age detection (inference), not age verification (confirmation). Age detection is less privacy-invasive in some ways (doesn't require ID submission) but more privacy-invasive in others (requires behavior tracking). Both have high error rates, but for different reasons. Verification fails because people lie. Detection fails because behavioral patterns don't reliably indicate age.

Why don't platforms just use the age data users provide when they create accounts?

Because users lie. When people create accounts, they're often incentivized to claim they're older than they are. A 12-year-old who wants to access TikTok will enter a birthdate that says they're 18. Platforms know this happens. Facebook research estimates 20-30% of young users lie about their age. So self-reported age data is unreliable. That's why platforms would need to verify age against external data (government databases or identity documents), which creates privacy risks and requires infrastructure that many people don't have.

Could biometric verification (facial recognition, voice analysis) solve the age-verification problem?

In theory, biometric approaches could be more reliable than behavioral inference. But they create massive privacy and security concerns. You'd be asking users to submit photos or voice samples tied to their identity. That data could be breached. It could be sold. It could be used for facial recognition tracking. It creates a permanent database linking faces to account history. Most privacy-forward jurisdictions explicitly restrict collecting biometric data from minors. So while technically feasible, biometric verification is politically and ethically problematic.

What happens if age-detection systems incorrectly flag someone as a minor?

That depends on implementation. In TikTok's system, your content gets suppressed and you see restricted feeds. In Australia's ban, you're removed entirely. In either case, to prove you're actually an adult, you probably need to submit identification documents. Now you're exposing your identity to the platform anyway. The system that was supposed to protect privacy by not requiring ID submission creates a perverse incentive where people submit ID just to fix a false positive.

Do age-verification laws actually reduce teenage social media use, or do they just drive it underground?

Evidence is mixed because most laws are too new to have long-term outcome data. Early indicators suggest teenagers find workarounds. They use VPNs, borrow adult accounts, use multiple accounts, or migrate to platforms with less enforcement. Tech-savvy users easily circumvent restrictions. Less tech-savvy users (disproportionately lower-income, rural, and from less-developed countries) face more barriers. So age restrictions probably reduce casual teenage use while pushing determined users toward less-regulated platforms, which might be even less safe.

Could parents effectively control their kids' social media use without government mandates?

This assumes parental oversight capacity that doesn't universally exist. Some parents can't monitor effectively (work constraints, education level, cultural barriers to discussing technology). Some parents don't understand how algorithms work or what risks exist. Some parents are dealing with more urgent survival challenges. And some teenagers will circumvent parental controls regardless. So while parental involvement helps, relying on it as the primary protection mechanism creates inequality. Low-engagement parental situations leave kids unprotected. That's why governments argue regulation is necessary.

What's the actual privacy cost of age-detection systems like TikTok's?

The system requires collecting and analyzing behavioral data at scale. TikTok needs to know what you watch, how long you watch it, which accounts you follow, what you like, what you search for, when you're online, what device you use, your location patterns, your language patterns, and your engagement patterns. They feed all this into machine learning models to make age inferences. That data now exists. It can be breached. It can be subpoenaed. It can be misused. Even if the age-detection purpose disappears, the data collection infrastructure remains. That's the privacy cost.

Are there regulatory approaches that could protect children without expanding surveillance?

Yes, in theory. Design-based regulations (requiring platforms to remove engagement-based recommendations for minors, limit daily usage, remove public metrics) would address actual harms without requiring behavioral surveillance. Algorithmic transparency requirements would enable oversight. But these approaches are harder to implement and regulate than age verification. They require technical expertise from regulators. They reduce platform engagement. So while possible, they're politically difficult. Age verification is simpler: easy to understand, easy to measure compliance, and externally visible as "doing something."

What happens to age-verification data after the original purpose fades or regulation changes?

Historically, surveillance infrastructure built for one purpose gets repurposed for another. The data will exist, and future governments or companies will find uses for it. Insurance companies might access it to assess risk profiles. Law enforcement might access it to find juveniles. Advertisers might access it to target demographics. Marketers might access it to identify vulnerable populations. There's no mechanism for data deletion once collected. So even if age-verification regulations change or are repealed, the infrastructure and data persist.

Why is Australia's approach (total ban) considered more controversial than TikTok's age-detection approach if both restrict access?

Australia's approach is clear and visible: No social media for under-16s, full stop. That's disruptive and affects a lot of people obviously. TikTok's approach seems less restrictive because accounts aren't deleted, just modified. But it requires more surveillance infrastructure and persistent behavior tracking. Psychologically, TikTok's approach feels like compromise, even though it might expand more harms (surveillance and bias). Australia's approach looks authoritarian but doesn't require permanent surveillance systems. Different visibility, different actual impacts.

Key Takeaways

- Australia's total ban and TikTok's age-detection represent opposite regulatory extremes: one eliminates access entirely, the other restricts algorithmically while requiring extensive surveillance.

- Age-detection systems achieve only 70-75% accuracy and disproportionately misidentify users from marginalized communities due to biased training data from geographically concentrated moderation teams.

- To function effectively, age-detection requires collecting and analyzing extensive behavioral data: watch history, searches, follows, engagement patterns, and device metadata—creating new privacy risks while supposedly protecting privacy.

- False positives in age-detection systems restrict legitimate adult users; false negatives fail to identify minors needing protection—forcing users to submit identification documents to fix algorithmic errors.

- Every proposed regulatory model trades one risk for another: bans are blunt but clear, age-detection maintains access but expands surveillance, consent models depend on variable parental engagement, design-based solutions would work but reduce platform revenue.

Related Articles

- TikTok US Deal Finalized: 5 Critical Things You Need to Know [2025]

- TikTok's US Deal Finalized: What the ByteDance Divestment Means [2025]

- TikTok's US Future Settled: What the $5B Joint Venture Deal Really Means [2025]

- Meta's Aggressive Legal Defense in Child Safety Trial [2025]

- Microsoft BitLocker Encryption Keys FBI Access [2025]

- Freecash App: How Misleading Marketing Dupes Users [2025]

![Age Verification & Social Media: TikTok's Privacy Trade-Off [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/age-verification-social-media-tiktok-s-privacy-trade-off-202/image-1-1769186305085.jpg)