Meta's Battle to Control Evidence in High-Stakes Child Safety Trial

When a company faces allegations of endangering children, the natural instinct is damage control. But Meta is taking that instinct to an extreme. As the social media giant prepares for a landmark trial in New Mexico, it's deploying a sophisticated legal strategy designed to keep certain evidence away from jurors entirely. The company has filed motions in limine—pretrial requests to exclude specific information from court proceedings—that go beyond typical defense tactics. Meta wants judges to bar evidence about social media's impact on youth mental health, references to the Molly Russell case, and even details about the company's financial resources.

This isn't the standard legal maneuvering everyone expects from a major corporation facing litigation. This is Meta pulling out every available tool to shape what jurors can actually see and hear. The strategy reveals something important about how big tech companies approach accountability. They don't just defend themselves against specific charges. They work to prevent the entire conversation from happening in the courtroom.

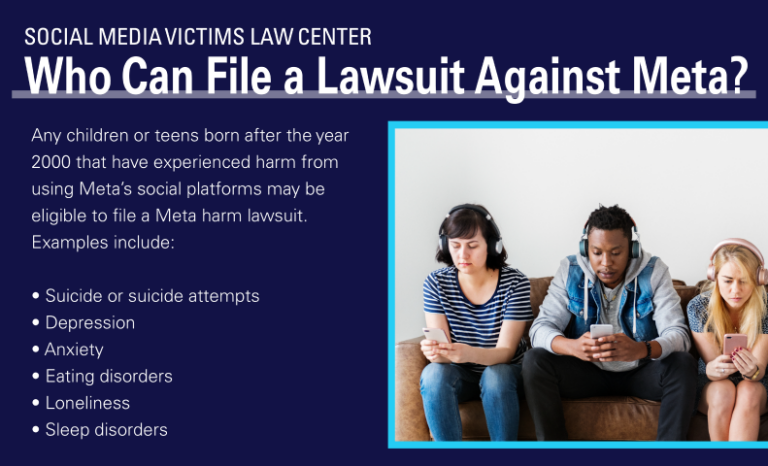

Understanding what Meta is trying to hide, why they're doing it, and what it means for the broader question of tech company accountability requires diving deep into the legal mechanics at play. The trial itself involves serious allegations: that Meta knowingly allowed its platforms to become vectors for child sexual exploitation, human trafficking, and grooming. The state of New Mexico claims Meta's algorithms actively served pornographic content to minors and that the company failed to implement basic safety measures despite knowing the risks. These aren't abstract allegations. They're grounded in evidence that New Mexico investigators gathered by simply creating fake accounts and documenting what happened next.

What Meta is trying to prevent jurors from hearing might matter more than the core allegations themselves. Because the case isn't just about whether Meta failed to protect children. It's about whether Meta had the capability, resources, and foreknowledge to do better and chose not to.

TL; DR

- The Core Case: New Mexico is suing Meta for allegedly failing to protect minors from sexual exploitation, human trafficking, and grooming on Facebook and Instagram

- Meta's Defense Strategy: The company filed motions in limine to exclude research on social media's mental health impacts, references to Molly Russell's death, and financial data

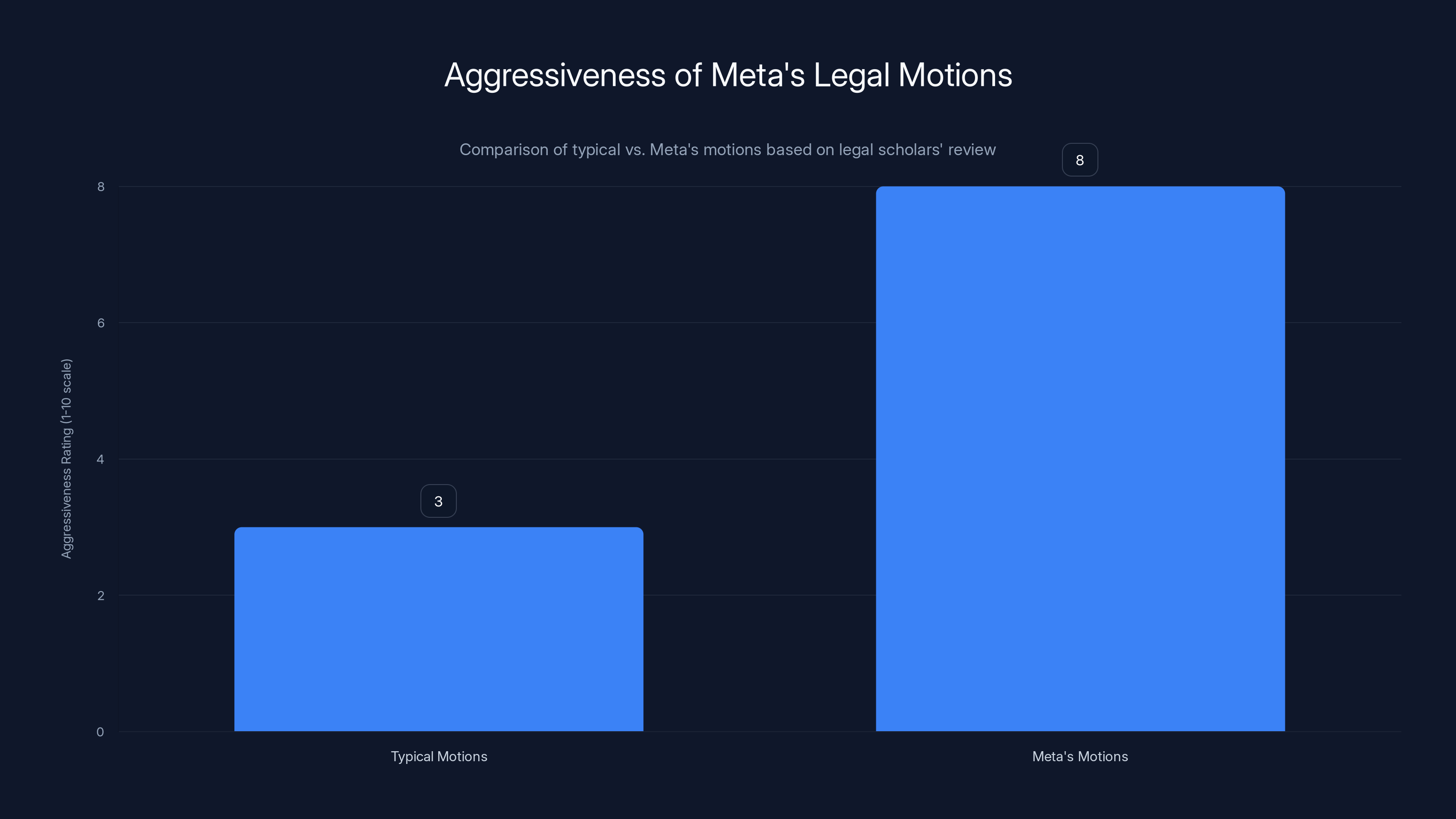

- Legal Precedent Concerns: Legal scholars say some of Meta's requests are unusually aggressive and threaten to limit jury access to contextual evidence

- The Broader Implications: Meta's approach reflects how tech companies attempt to control narratives during high-stakes litigation

- What's at Stake: The trial could set precedent for how platforms are held accountable for harms they facilitate

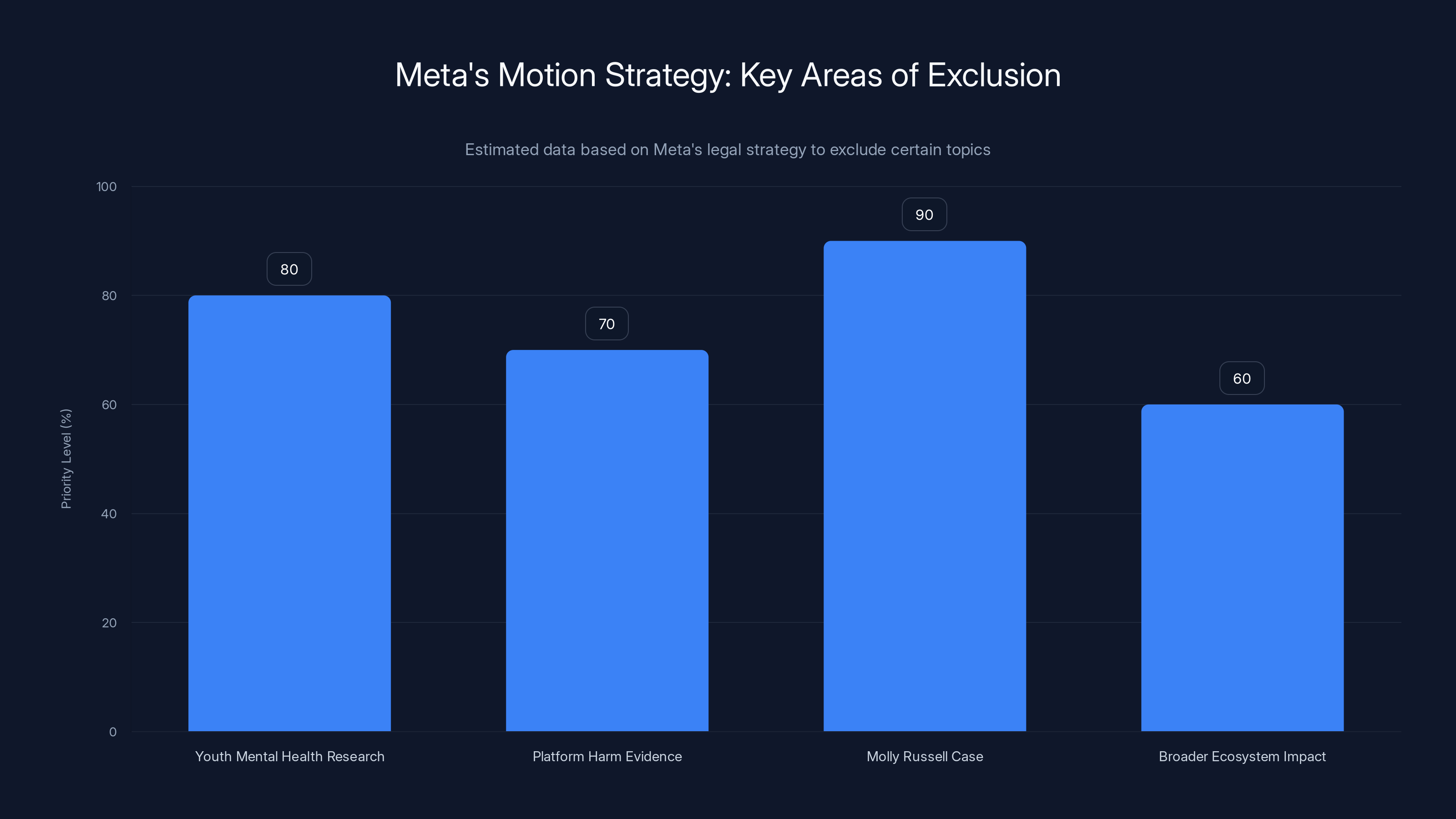

Meta's legal strategy prioritizes excluding topics like the Molly Russell case and youth mental health research, with an estimated high exclusion priority of 90% and 80% respectively.

The New Mexico Lawsuit: What Meta Actually Faces

The case brought by New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez represents one of the most serious legal challenges Meta has faced regarding child safety. Unlike some child safety complaints that rely on broad claims and statistical projections, this case is built on concrete methodology. New Mexico's investigators didn't survey users or rely on external studies. They created test accounts and documented exactly what Meta's systems showed them.

The setup was straightforward but devastating. Investigators created fake Facebook and Instagram accounts posing as underage girls. Within days, these accounts received explicit messages and were shown algorithmically amplified pornographic content. In another test, investigators created an account as a mother offering to traffic her young daughter. Meta's systems failed to flag suggestive comments on her posts or shut down accounts that violated platform policies around child safety.

This methodology matters because it eliminates the ambiguity that often clouds tech regulation discussions. Meta can't claim confusion about what its algorithms do or argue that the problems were isolated user-generated content. The investigation shows what happens when Meta's systems operate exactly as designed. The algorithms recommend content. The recommendation system amplifies explicit material. The safety systems don't intervene.

New Mexico's complaint alleges violations of the state's Unfair Practices Act. The state claims Meta proactively served pornographic content to minors and failed to implement child safety measures it either possessed or could have implemented. What's notable is that this framing doesn't require proving Meta intended to cause harm. It requires showing that Meta's practices were unfair and caused measurable injury. That's a lower bar than criminal negligence but still substantial.

The case also touches on something Meta has tried to minimize in past litigation: knowledge. New Mexico's complaint details that Meta has conducted internal research understanding these risks for over a decade. The company has tools, frameworks, and expertise around child safety. The lawsuit essentially argues that knowledge without appropriate action constitutes unfair practice.

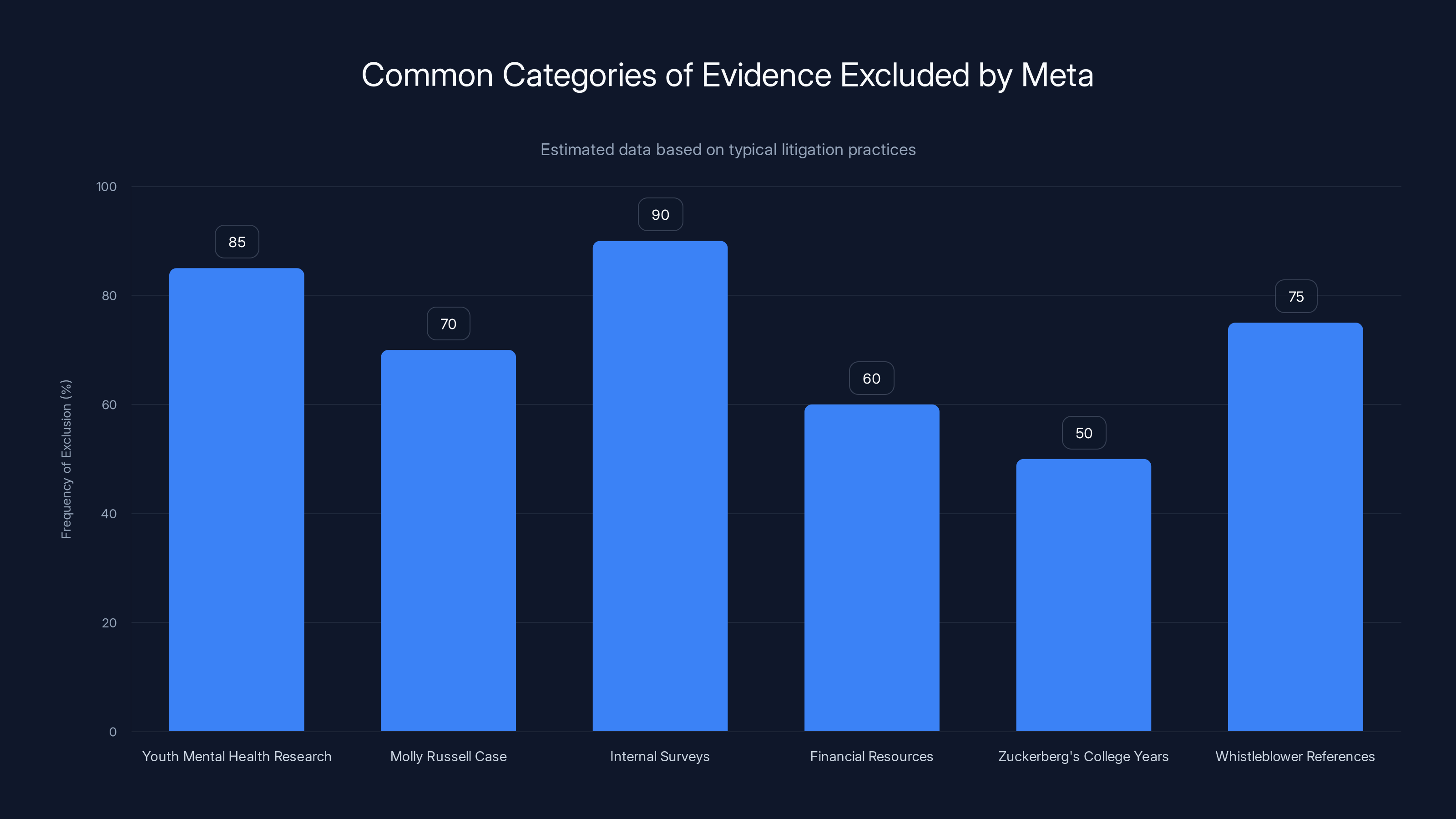

Meta frequently files motions to exclude broad categories of evidence, with internal surveys and youth mental health research being among the most targeted. Estimated data.

Meta's Motion Strategy: What the Company Wants Hidden

Meta's motions in limine reveal a company deeply concerned about how context might shape jury perception. The motions aren't random. They follow a logical pattern: exclude anything that explains why the platforms are dangerous, exclude anything that demonstrates Meta's capacity to prevent harm, and exclude anything that could make jurors emotionally invested in the severity of the problem.

Start with mental health research. Meta petitioned the court to exclude references to research about social media's impact on youth mental health. This includes reports from former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, whose public advisory documented connections between social media use and depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in teenagers. Meta argues these studies treat social media companies as a monolith and constitute irrelevant hearsay.

The logic behind this motion reveals a key defensive strategy. Meta wants the jury focused narrowly on whether Meta violated specific provisions of New Mexico law. The company wants to prevent the conversation from expanding into the broader ecosystem question: do these platforms harm young people? Because once that conversation starts, the specific harms alleged in the complaint become clearer. A child groomed on Instagram isn't an isolated failure. It's part of a broader pattern where the platform's mechanics enable harm.

Next, Meta moved to exclude the Molly Russell case entirely. Russell was a British teenager who died by suicide in 2017 after viewing content on social media depicting self-harm and suicide. Her parents later learned that Instagram's algorithms were actively recommending her this content. The case became a touchstone in discussions about platform accountability and youth mental health. Meta clearly doesn't want jurors hearing about it. The company argues it's prejudicial and shouldn't influence their thinking about Meta's specific conduct.

But here's what makes this motion significant: Meta isn't arguing that the Russell case is factually inaccurate or that it's a false analogy. Meta is arguing that the emotional impact of the case is so strong that jurors can't be trusted to compartmentalize it. That's a telling admission. Meta is essentially saying: if jurors know what happened to Molly Russell, they'll be so upset that they won't judge us fairly. That's possible. It's also possible that jurors need to understand the gravity of what algorithmic systems can do to make an informed decision.

Meta also moved to exclude third-party surveys and Meta's own internal surveys purporting to show high amounts of inappropriate content on the platform. These surveys matter because they provide quantitative evidence of scale. It's one thing to say sexual exploitation happens on Instagram. It's another to say surveys indicate X percentage of the platform contains such content. The first is vague and contestable. The second creates a framework for understanding just how widespread the problem is.

Meta argues surveys constitute hearsay and are therefore inadmissible. But surveys are routinely admitted in civil cases to establish facts about market conditions, consumer perception, or prevalence. Meta's argument essentially amounts to: we don't want jurors seeing data that shows how pervasive inappropriate content is on our platforms.

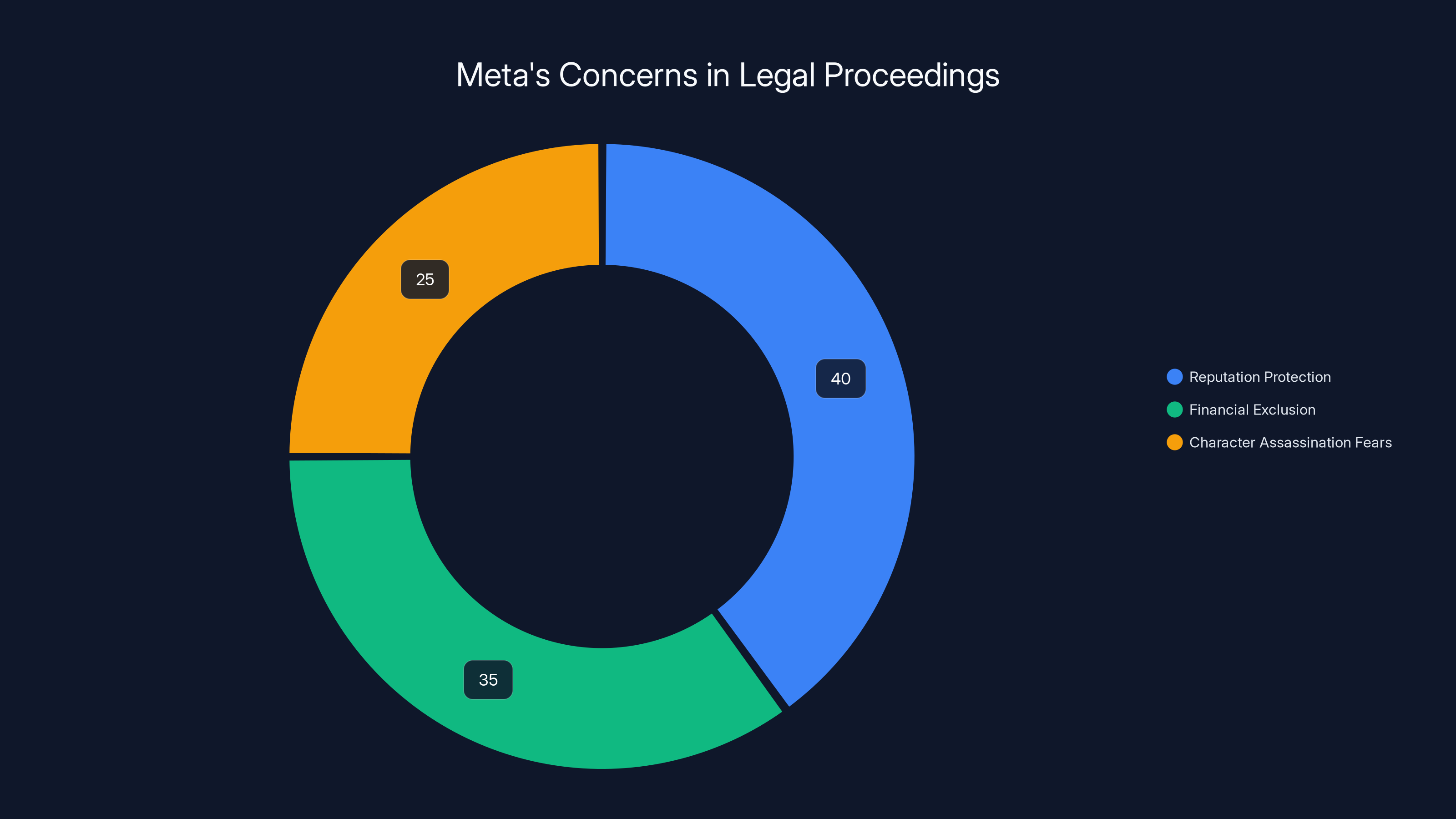

The Reputation Protection: Zuckerberg, Finances, and Character Assassination Fears

Perhaps the most revealing motions involve Meta's attempts to protect the company's reputation and Mark Zuckerberg's personal character. Meta has asked the court to exclude any references to Zuckerberg's college years, including his creation of an attractiveness-rating website in 2003. The company argues that surfacing "unflattering comments or incidents" from when Zuckerberg was a student would be unfairly prejudicial and constitute an impermissible use of propensity evidence.

This motion is fascinating because it reveals deep anxiety about character-based arguments. Courts generally don't allow evidence about someone's past misconduct to suggest they're inclined to engage in similar misconduct now. That's the propensity rule, and it exists for good reason. You can't convict someone of stealing today based on evidence they stole twenty years ago.

But Meta's concern hints at something the company fears: jurors might see a pattern. A young Mark Zuckerberg creating a site to rate women's attractiveness speaks to attitudes about consent, objectification, and respect for others. A middle-aged Mark Zuckerberg presiding over a platform that sexually exploits minors might feel connected in ways that seem relevant to jurors, even if legally distinct. Meta wants to prevent that possible connection from forming.

Meta has also requested that the court exclude evidence regarding the company's financial condition, including market capitalization, revenues, profits, and wealth. This is significant because wealth evidence typically comes into play during damages calculations. If a jury finds Meta liable, they need to assess penalties proportional to what the company can actually pay. A million-dollar fine means something very different to a startup than to a corporation worth a trillion dollars.

By excluding this information, Meta wants to prevent jurors from calibrating damages appropriately. The company essentially wants juries to award penalties they'd assign to any company regardless of the defendant's resources. This protects Meta from damages that would actually cause financial harm proportional to the violation.

Meta also moved to preclude references to former employees or contractors who might testify as "whistleblowers." The company argues that whistleblower is a legal term of art and that describing witnesses this way would inflame and confuse jurors. Again, this reveals anxiety about narrative. A witness who worked at Meta and observed concerning practices is just a witness. A whistleblower—someone who spoke up specifically because they observed misconduct—carries moral weight. They're a narrator of truth. Meta wants to strip that context from the testimony.

Estimated data suggests Meta's legal motions focus primarily on reputation protection (40%), followed by financial exclusion (35%) and addressing character assassination fears (25%).

Legal Scholars Weigh In: Are These Motions Reasonable?

Two legal scholars who reviewed Meta's motions found some of them unusually aggressive. This matters because in limine motions, while standard, are typically narrower than what Meta requested. The typical motion to exclude evidence focuses on technical legal problems: the evidence is irrelevant, it's repetitive, it's more prejudicial than probative. Meta's motions go further. They attempt to construct an evidentiary bubble where certain topics simply cannot be discussed.

Consider the mental health research motion. Vivek Murthy's public advisory on social media and youth mental health isn't Meta-specific. It examines the relationship between social media use generally and mental health outcomes. Meta claims it's irrelevant hearsay. But in a case where New Mexico alleges Meta facilitated serious harms to minors, context about what social media actually does to minors seems directly relevant. The question isn't whether social media in the abstract impacts youth mental health. The question is whether the specific harms Meta allowed can be understood against a backdrop of what platforms generally do.

Legal scholars also noted that Meta's attempts to exclude its own internal surveys about inappropriate content seem particularly aggressive. When a defendant wants to hide its own data suggesting a problem exists, that naturally raises questions about what the company feared jurors would learn. Moreover, internal surveys are sometimes more probative than external studies. If Meta conducted a survey and found that X percent of content on its platform is inappropriate, that's Meta's own company research. It's not hearsay in the traditional sense. It's direct evidence of what Meta itself believed about conditions on its platform.

The Molly Russell motion also drew scrutiny. Excluding relevant evidence about similar harms on similar platforms is legally possible but unusual in civil cases. Civil courts generally permit broader evidentiary scope than criminal courts. The theory is that in civil cases, juries should understand the full context of a defendant's conduct. Molly Russell's death isn't meant to prove Meta specifically intended to harm her. It's meant to establish that platforms structurally similar to Meta's have facilitated serious harm through similar mechanisms.

One scholar noted that Meta's motions collectively reveal a strategy to prevent the jury from understanding Meta's knowledge, capability, and the broader context of platform harms. Individually, each motion might survive legal scrutiny. Collectively, they attempt to construct a courtroom narrative where serious questions simply don't get asked.

The Role of AI Chatbots and Additional Concerns

Meta has also moved to exclude references to the company's AI chatbots. This seems oddly specific until you understand Meta's current product strategy. The company is investing heavily in AI, including conversational AI systems designed to engage users. If one of those chatbots engaged in inappropriate conversations with minors or recommended harmful content, that would suggest Meta's expansion into AI is replicating and potentially amplifying existing child safety problems.

By excluding chatbot references, Meta prevents discussion of whether the company's newer systems inherited or extended older safety problems. It's another layer of preventing jurors from understanding Meta's full business practices and how child safety integrates across the company's product portfolio.

Meta has also requested that law enforcement officials not appear in uniform during testimony. This is a subtle motion, but it matters for jury perception. A police officer or investigator in uniform carries authority and institutional credibility. An officer in street clothes is just a person testifying. By requesting plain clothes, Meta seeks to diminish the apparent authority of law enforcement witnesses who might describe what they found during their investigation.

Legal scholars found Meta's motions to be unusually aggressive compared to typical in limine motions, which are generally narrower in scope. Estimated data based on narrative.

What This Strategy Reveals About Tech Company Accountability

Meta's comprehensive approach to limiting evidence reveals something important about how large tech companies approach litigation. The goal isn't just to win the specific case. It's to prevent certain conversations from happening at all. By filing motions to exclude mental health research, financial data, and contextual cases, Meta is trying to narrow the trial into a purely technical discussion: Did we violate this specific statute? Rather than a broader accountability discussion: Should we be allowed to operate this way given what we know?

This strategy is sophisticated because it respects the legal system's rules while pushing those rules to their limits. Meta isn't arguing that mental health research is false. It's arguing it's irrelevant. Meta isn't claiming it doesn't have substantial financial resources. It's arguing that jurors shouldn't know about them. These are legally permissible arguments. They're also arguments designed to prevent accountability.

The strategy also reveals asymmetry in litigation resources. Meta has the financial capacity to hire top legal talent to file comprehensive, technically sophisticated motions. New Mexico's attorney general, while competent, has fewer resources to file counter-motions and push back on every request. This asymmetry means that plaintiffs suing corporations face not just the corporation's defense but its ability to reshape the very evidence juries can consider.

Precedent and Future Implications

How the New Mexico court rules on these motions will matter for future technology litigation. If Meta successfully excludes mental health research, similar companies in future suits could make identical arguments. If financial information gets excluded, tech companies could argue that damages shouldn't reflect their resources. These rulings will shape what future trials look like.

Beyond the specific trial, Meta's approach signals how tech companies intend to defend themselves against accountability. They will use every legal tool available to construct narrow evidentiary frameworks. They will argue that emotional impact disqualifies relevant evidence. They will claim that while they conduct internal research, such research shouldn't be visible to juries. They will attempt to separate their capabilities from their conduct, arguing that having resources doesn't mean they were obligated to use them.

For anyone interested in technology accountability, this trial is worth watching. Not because the outcome is predetermined—it isn't. But because the litigation itself is revealing how tech companies approach the question of responsibility. Meta's strategy suggests the company believes that preventing jurors from understanding context is more important than defending their specific conduct. That tells you something about their confidence in the conduct itself.

The Broader Ecosystem: Other Tech Companies and Similar Litigation

Meta isn't alone in facing serious child safety litigation. Multiple companies have faced related complaints. What makes this case notable is its specificity. New Mexico's investigators didn't rely on surveys or testimony. They created accounts and documented what happened. That methodology is reproducible and doesn't depend on ambiguous metrics or contested research.

Other platforms now understand that this approach works. More states are likely to pursue similar investigations. More trials will focus on what algorithms actually do when given minimal constraints. Meta's legal strategy in New Mexico will become a template for other companies. If Meta successfully excludes certain evidence, expect other defendants to file identical motions. If Meta fails, expect revised strategies.

The trial also occurs against a backdrop of increasing regulatory attention to children's online safety. The Federal Trade Commission has taken action against Meta multiple times. Congress has debated legislation specifically targeting how platforms treat minors. State attorneys general across the country have escalated investigations. In this context, the New Mexico trial is less about one state's specific statute and more about whether tech companies can be held accountable for knowingly facilitating serious harms.

The Discovery Process and What We Know

Meta's motions became public through New Mexico's public records system. This transparency itself is notable. In some jurisdictions, pretrial motions remain sealed. Here, we can actually see Meta's legal arguments. This transparency helps explain why Meta might be concerned. When your arguments are public, they can be scrutinized, criticized, and used to shape public perception.

The visible discovery process also reveals something about Meta's internal knowledge. The fact that the company even needs to file motions to exclude internal surveys suggests the surveys exist and show concerning findings. Companies don't typically file motions to exclude data they're proud of. They don't move to hide research unless that research might undermine their position.

What's notable is that the most aggressive motions target Meta's own data. The company moves to exclude its own surveys about inappropriate content. It moves to exclude information about its financial resources and employee compensation. It moves to exclude references to Zuckerberg's college-era choices. These aren't requests to exclude the plaintiff's experts or outside research. They're requests to hide Meta's own information from jurors.

Courts are more likely to admit evidence unless it fails the relevance test or is overly prejudicial. Estimated data.

How Courts Typically Handle In Limine Motions

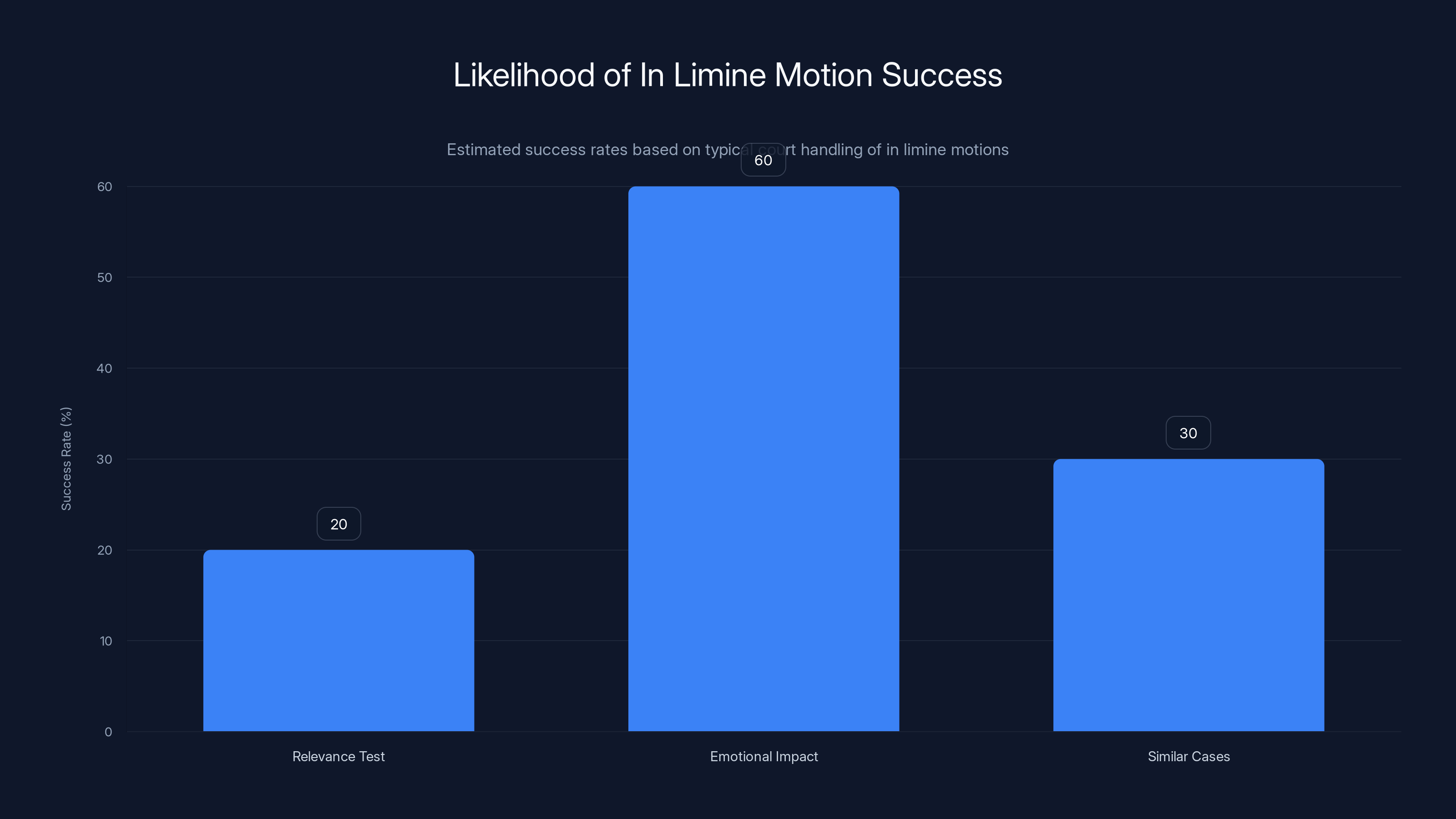

Understanding how courts approach these motions provides context for what might happen next. Judges handling in limine motions generally operate under the principle that evidence should be admitted unless there's a specific legal reason to exclude it. Relevance is broadly interpreted in civil cases. Judges often reason that if evidence makes a fact of consequence more or less probable, it's relevant, even if it's tangential to the core claim.

Meta's motions to exclude mental health research would likely survive this relevance test. If the question is whether Meta's platforms cause harm to minors, research about how social media generally affects youth mental health is relevant context. Courts would likely admit it. The motion to exclude surveys about inappropriate content would similarly likely fail. Prevalence of harmful content on the platform is directly relevant to whether New Mexico's claims have merit.

The motions most likely to succeed are those targeting emotional impact. Courts do sometimes exclude evidence that, while relevant, would create excessive emotional response. For instance, photos of severe injuries in a negligence case might be excluded if less graphic evidence makes the same point. But even here, the bar is high. The evidence must be primarily prejudicial with limited probative value.

The Molly Russell motion seems likely to fail. Similar cases involving similar platforms and similar harms are typically admissible in civil litigation. They're not being offered to prove Meta caused similar harm to Molly Russell—they're offered to show that platforms like Meta's can facilitate serious harm through similar mechanisms.

Meta's Response Strategy and Company Messaging

Meta has publicly responded to the allegations by emphasizing investments in teen safety. A Meta spokesperson stated that the company has listened to parents, experts, and law enforcement for over a decade, conducting research to understand relevant issues and implement protections. The company points to Teen Accounts with built-in protections and parental tools.

This messaging strategy attempts to separate Meta's intent from its conduct. The company wants to be seen as taking safety seriously. The existence of Teen Accounts proves it. Whether those protections are adequate or whether they address the specific harms New Mexico alleges is a different question. But public messaging focuses on intent and effort rather than outcomes.

This disconnect between messaging and legal strategy is notable. Publicly, Meta emphasizes child safety efforts. Legally, Meta moves to prevent jurors from knowing how widespread inappropriate content is on the platform. Publicly, Meta talks about listening to experts. Legally, Meta attempts to exclude expert research on social media's harms. The mismatch suggests that Meta's legal and communications teams operate in parallel worlds.

The California Consolidated Trial Context

Meta faces additional relevant litigation in California. Meta lawyers have separately sought to keep information about Zuckerberg's college years—including the famous attractiveness-rating site Facemash—out of a consolidated trial set to begin later in 2025. This parallel litigation matters because legal teams often develop and share strategies across cases. If Meta succeeds in New Mexico in excluding certain evidence, the company will argue similar exclusions should apply in California.

The California trial involves similar allegations and similar evidence. Multiple cases involving Meta's conduct regarding minors are consolidating. These consolidated proceedings give Meta incentive to establish broad evidentiary rules that would apply across multiple trials. A ruling that excludes mental health research in New Mexico becomes precedent Meta can cite in California.

Financial Implications and Damages Calculations

Meta's attempt to exclude financial information has direct implications for damages. If a court rules that a company violated unfair practices laws and harmed consumers or vulnerable populations, how much should the penalty be? Financial resources matter. A company with annual revenues in the tens of billions bears penalties differently than a company with millions in revenue.

Punitive damages, if awarded, are specifically designed to be painful enough to deter future misconduct. A punitive damages award that represents a small fraction of annual revenue might not deter anything. Meta's motion to exclude financial data essentially argues that penalties should be based on the severity of harm alone, without calibration to company resources.

If Meta succeeds, it gets something unique: a penalty structure where its massive size and resources provide insulation from proportional damages. The court would struggle to impose damages painful enough to deter future conduct without knowing whether a given amount is a trivial cost or a significant expense for Meta.

What the Broader Public Should Understand

Meta's legal strategy in New Mexico is instructive because it reveals both how the legal system works and how companies attempt to subvert accountability within that system. The company isn't breaking rules. It's operating within legal frameworks while pushing boundaries. The company's argument that certain evidence is irrelevant or prejudicial is legally coherent, even if questionable as a matter of justice.

The trial matters because it will test whether platforms can be held accountable when they knowingly facilitate harm. It matters because the evidence New Mexico has gathered through direct investigation is concrete and reproducible. It matters because the outcome will likely shape how other states approach similar litigation. And it matters because the legal strategy Meta is pursuing will become a template for other tech companies facing accountability.

For people concerned about child safety online, the trial is important. But the legal maneuvering surrounding the trial is equally important. How much context juries can access affects their ability to make informed decisions. How much companies can hide affects accountability. How much financial resources can be kept from juries affects whether penalties actually deter.

The Question of Fairness in Tech Litigation

There's a fundamental question underlying Meta's motion strategy: What constitutes a fair trial when the defendant is a corporation with vast resources and the plaintiff is a state attorney general? Meta's argument is that certain evidence, while perhaps relevant, is so prejudicial that it prevents fair judgment. But you could ask the inverse question: If jurors don't know Meta's resources, its knowledge, its capacity, and the broader context of harms, can they render a fair judgment about whether the company's conduct was unfair?

Fairness arguably requires understanding the full context. A company that knowingly facilitated harm but lacked resources to prevent it might face different judgment than a company that possessed capacity and knowledge but chose inaction. By hiding this context, Meta prevents jurors from making genuinely fair assessments. They're asked to judge conduct in a vacuum rather than in context.

Meta would argue that legal frameworks exist precisely to prevent such broad-ranging contextual judgments. Defendants deserve narrow, specific trials on specific charges. But that argument works differently when the defendant is an enormous corporation and the plaintiff is a state seeking accountability on behalf of minors. The asymmetry of resources and information creates questions about whether narrow trials actually serve fairness.

Looking Forward: Implications for Tech Accountability

How this trial proceeds and concludes will influence tech regulation and accountability for years. If Meta succeeds in excluding evidence, companies will follow suit in their own litigation. If the court admits broad evidence and Meta faces significant consequences, we'll see a different litigation landscape. Companies will invest in better safety practices to reduce their exposure, or they'll invest in more sophisticated legal strategies to reduce their liability.

The case also occurs at a moment when public concern about children's online safety is high. Multiple investigations have documented that platforms' algorithms recommend self-harm content to minors, that grooming occurs at scale, that sexual exploitation happens with relative impunity on major platforms. Meta's legal strategy essentially amounts to asking courts not to let juries know about any of this.

Whether courts agree that such evidence should be hidden or whether they conclude that juries need context to make informed decisions will matter enormously. The rulings on Meta's motions will shape what future tech accountability looks like. They'll determine whether companies can have conversations about accountability in the public sphere while having dramatically narrower conversations in courtrooms. They'll establish precedent about what information shareholders, regulators, and juries can access when evaluating tech company conduct.

FAQ

What are motions in limine and why do companies file them?

Motions in limine are pretrial requests asking a judge to exclude specific evidence or arguments from trial. Companies file them to prevent juries from considering information that might be prejudicial or legally improper. They're standard in litigation, but the scope and aggressiveness of motions varies. Meta's motions are considered unusually comprehensive in attempting to exclude broad categories of evidence rather than specific items.

What evidence is Meta specifically trying to exclude from the trial?

Meta has filed motions to exclude research on social media's impact on youth mental health, references to the Molly Russell case, Meta's own internal surveys about inappropriate content prevalence, the company's financial resources and employee compensation, references to Zuckerberg's college years, and references to former employees as "whistleblowers." The company also requested that law enforcement witnesses not appear in uniform.

Why does Meta want to hide its own internal survey data about inappropriate content?

If Meta's own surveys indicate high levels of inappropriate content on its platforms, that data directly contradicts claims that the company was unaware of the problem. By excluding these surveys, Meta prevents jurors from seeing the company's own assessment of content conditions. This protects Meta from the inference that the company knew about problems and failed to address them proportionally.

How would excluding mental health research affect the trial?

Excluding mental health research would prevent jurors from understanding the broader context of how social media affects youth. New Mexico could prove Meta facilitated specific harms, but jurors wouldn't understand those harms against the backdrop of what research shows social media generally does to developing brains. This narrower focus benefits the defense because specific harms seem more isolated without contextual research.

Is Meta's strategy likely to succeed with the court?

Legal scholars suggest that while some motions might survive (particularly those focusing on emotional prejudice), the more aggressive requests—especially excluding Meta's own surveys and relevant expert research—face higher bars. Civil courts generally admit evidence that makes facts of consequence more or less probable. Meta's broad exclusion requests exceed typical evidentiary gatekeeping, but judges retain discretion and might grant some motions.

What does the Molly Russell case have to do with Meta's conduct?

Molly Russell died by suicide in 2017 after viewing content on social media depicting self-harm and suicide. Her parents later learned Instagram's algorithms recommended such content to her. The case exemplifies how platforms structurally similar to Meta's have facilitated serious harm through algorithmic recommendation. New Mexico might reference it to show that similar harms on similar platforms are foreseeable and historically documented.

Why would excluding financial information from jurors matter for damages?

If Meta is found liable, jurors would typically help determine damages. Knowing that Meta has massive annual revenues allows jurors to set penalties proportional to the company's capacity to bear them. Without this information, jurors might set damages they believe are appropriate without understanding whether the penalty represents a significant expense or a rounding error for Meta. Excluding finances essentially prevents appropriately calibrated damages.

How do these motions affect Meta's public messaging?

Meta's public statements emphasize child safety investments and listening to experts. But the company's legal motions attempt to exclude expert research and hide financial capacity. This disconnect between public messaging (we care about safety) and legal strategy (prevent jurors from seeing evidence about harms) suggests different audiences receiving contradictory information about Meta's actual position.

Could these legal strategies be replicated in other tech company litigation?

Almost certainly. If Meta succeeds with certain motions, other tech companies facing similar allegations will file identical motions citing Meta as precedent. If Meta loses, companies will refine the arguments and try again. Either way, the legal templates developed in this trial will influence how tech companies defend themselves in future accountability litigation across multiple jurisdictions.

What does this trial reveal about accountability for tech platforms?

The trial reveals that tech companies will aggressively use legal procedures to limit evidence and context when facing accountability claims. While operating within legal frameworks, these strategies attempt to make it harder for jurors to understand company knowledge, capability, and the scope of harms. This raises questions about whether legal systems can effectively hold platforms accountable or whether extensive resources enable companies to prevent meaningful accountability conversations.

Conclusion: The Battle Over Evidence and Accountability

Meta's comprehensive approach to excluding evidence in the New Mexico trial isn't unusual in form—in limine motions are standard—but it is unusual in scope and aggressiveness. The company is attempting to construct a courtroom where the conversation stays narrowly technical: Did Meta violate this statute? Rather than expanding to broader accountability questions: Should Meta be allowed to operate this way given what we know?

This legal strategy is sophisticated and resourced. It reflects Meta's calculation that preventing context is more important than defending specific conduct. The company apparently believes that if jurors understand how prevalent inappropriate content is on Meta's platforms, how much Meta knows about social media's harms, how financially capable Meta is of implementing stronger protections, and how similar harms have happened before, the jury will find against the company. So the company is trying to prevent jurors from learning these things.

What happens next depends on how the court rules. If judges grant Meta's motions broadly, we'll see tech company litigation become increasingly narrow and technical. If judges reject the more aggressive requests, we'll see trials that actually let juries understand the full context of what happened. The precedent established here will shape how other companies defend themselves and how other states pursue accountability.

For people concerned about technology's impact on children, this trial matters. But the legal maneuvering matters equally. How much evidence companies can hide affects whether accountability is meaningful. How much context juries can access affects whether decisions are informed. How much financial information stays hidden affects whether penalties actually deter future misconduct. These aren't abstract legal questions. They determine whether technology companies face real consequences for facilitating real harms.

The trial will also test whether the legal system can actually hold large technology platforms accountable or whether vast resources enable companies to prevent meaningful accountability conversations entirely. Meta's strategy suggests the company believes the latter is possible. The coming months will reveal whether courts agree.

Key Takeaways

- Meta filed extensive motions to exclude mental health research, financial data, and the Molly Russell case from its New Mexico child safety trial

- Legal scholars view some of Meta's evidence exclusion requests as unusually aggressive, designed to prevent jurors from understanding platform harms and company capability

- New Mexico investigators gathered concrete evidence by creating fake underage accounts that received explicit messages and algorithmically amplified pornographic content

- Meta's legal strategy reveals how tech companies use litigation procedures to prevent accountability conversations by limiting evidentiary context available to juries

- The trial's outcomes on evidence admissibility will establish precedent affecting how other states pursue tech platform accountability and how companies defend themselves in future litigation

Related Articles

- UK Social Media Ban for Under-16s: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Snapchat's New Parental Controls: Screen Time Monitoring for Teens [2025]

- Luminar's Collapse: Inside Austin Russell's Bankruptcy Battle [2025]

- Meta's Illegal Gambling Ad Problem: What the UK Watchdog Found [2025]

- Smartwatch Fall Detection Lawsuits: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Trump Mobile FTC Investigation: The Broken Promises Scandal [2026]

![Meta's Aggressive Legal Defense in Child Safety Trial [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-aggressive-legal-defense-in-child-safety-trial-2025/image-1-1769092580832.jpg)