The End of an Era: Nuclear Treaties Are Dead

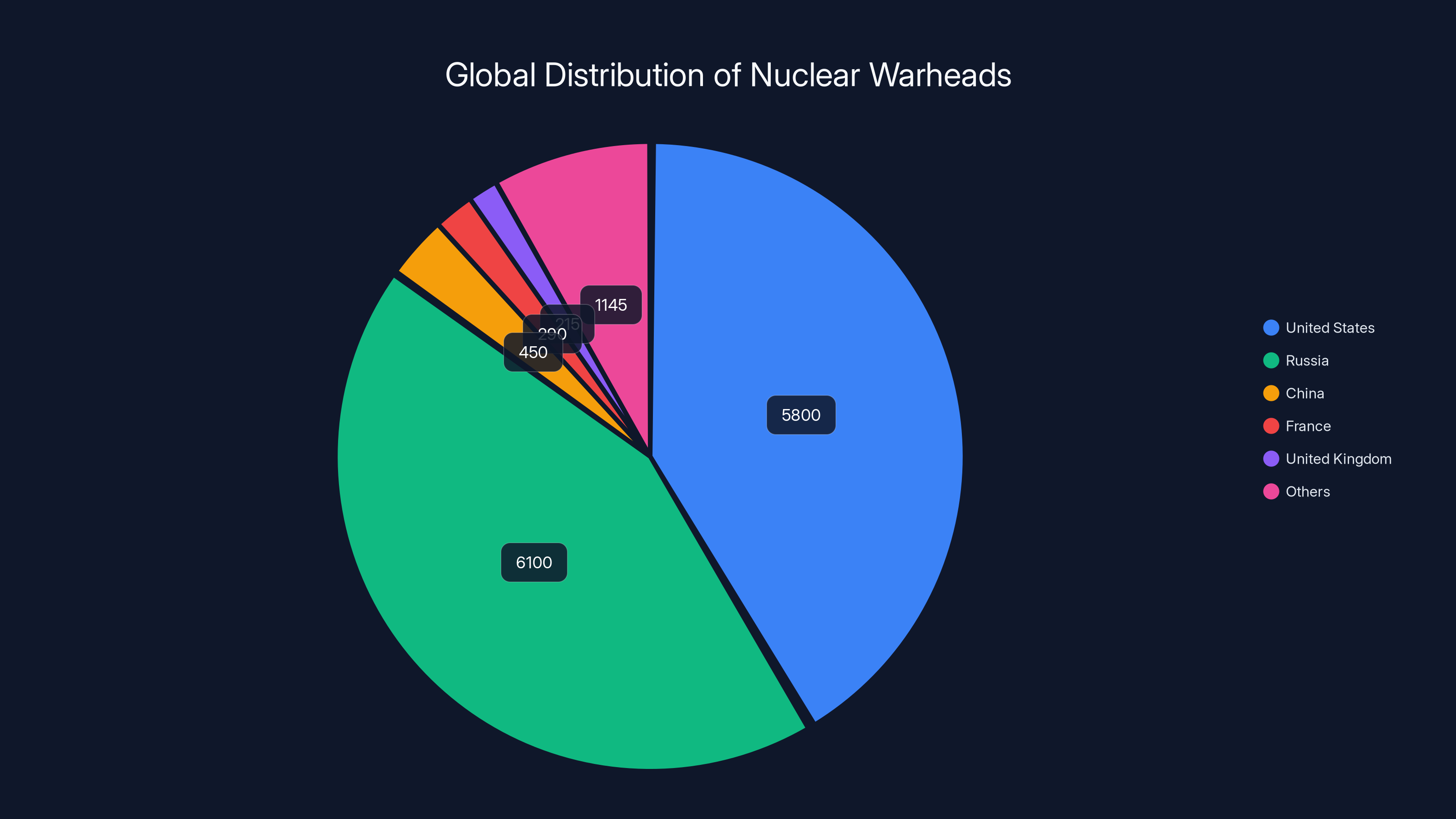

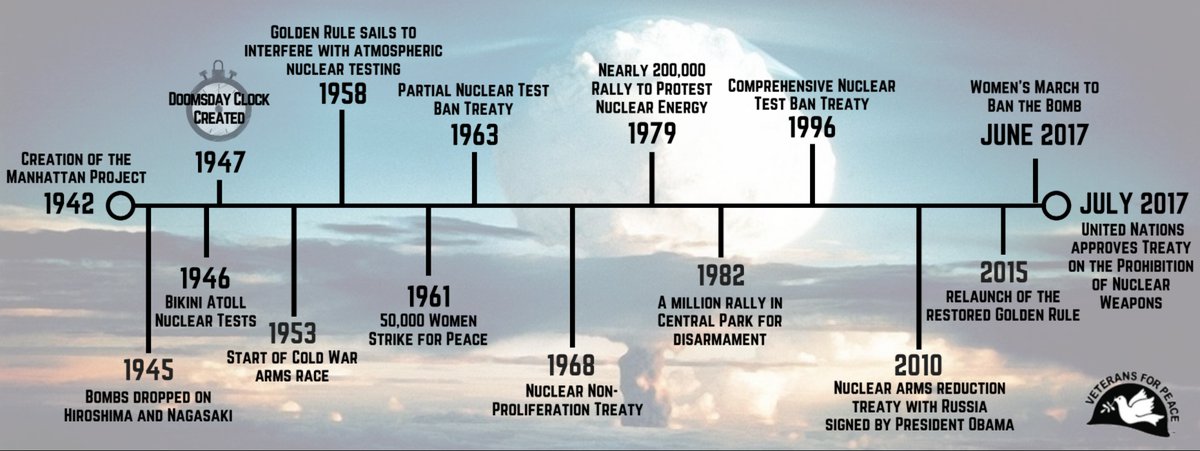

For fifty years, the world's most powerful nations did something genuinely remarkable. They stopped building nuclear weapons at the same pace they'd started. In 1985, humanity had stockpiled over 60,000 nuclear warheads. By 2024, that number had shrunk to roughly 12,000. That's a 50,000-weapon reduction. Not a typo. Fifty thousand fewer opportunities for civilization-ending mistakes, according to Statista's data.

How'd they pull it off? Treaties. Complex, intricate, painfully negotiated agreements between the United States and Russia that forced both sides to count, verify, and ultimately destroy nuclear arsenals. On-site inspections. Scientific reviewers. Diplomats. Humans, doing human work.

Then, in February 2025, New START—the last major nuclear arms control treaty between Washington and Moscow—expired. It's gone. No replacement in sight.

Now both countries are doing what they were always incentivized to do: build new weapons. Russia's testing advanced systems. The US is spending billions on modernization. China's constructing new intercontinental ballistic missile silos across the Gobi Desert. South Korea's openly discussing the bomb. Trust between nations? At historic lows.

Into this vacuum steps a bold, weird proposal: what if satellites and artificial intelligence could do the job that inspectors once did on the ground?

Researchers at think tanks like the Federation of American Scientists are pitching exactly that. No more boots on foreign soil. Instead, overhead reconnaissance paired with AI systems trained to spot weapons, track movements, and flag suspicious activity. Humans review the findings. Everyone stays home.

It sounds promising in theory. In practice? It's complicated, risky, and probably won't work without something the world's nuclear powers seem to have lost: mutual cooperation.

Let's break down what's being proposed, why it might work, why it absolutely could fail, and what happens if it does.

The Death of New START and the Nuclear Arms Race Restart

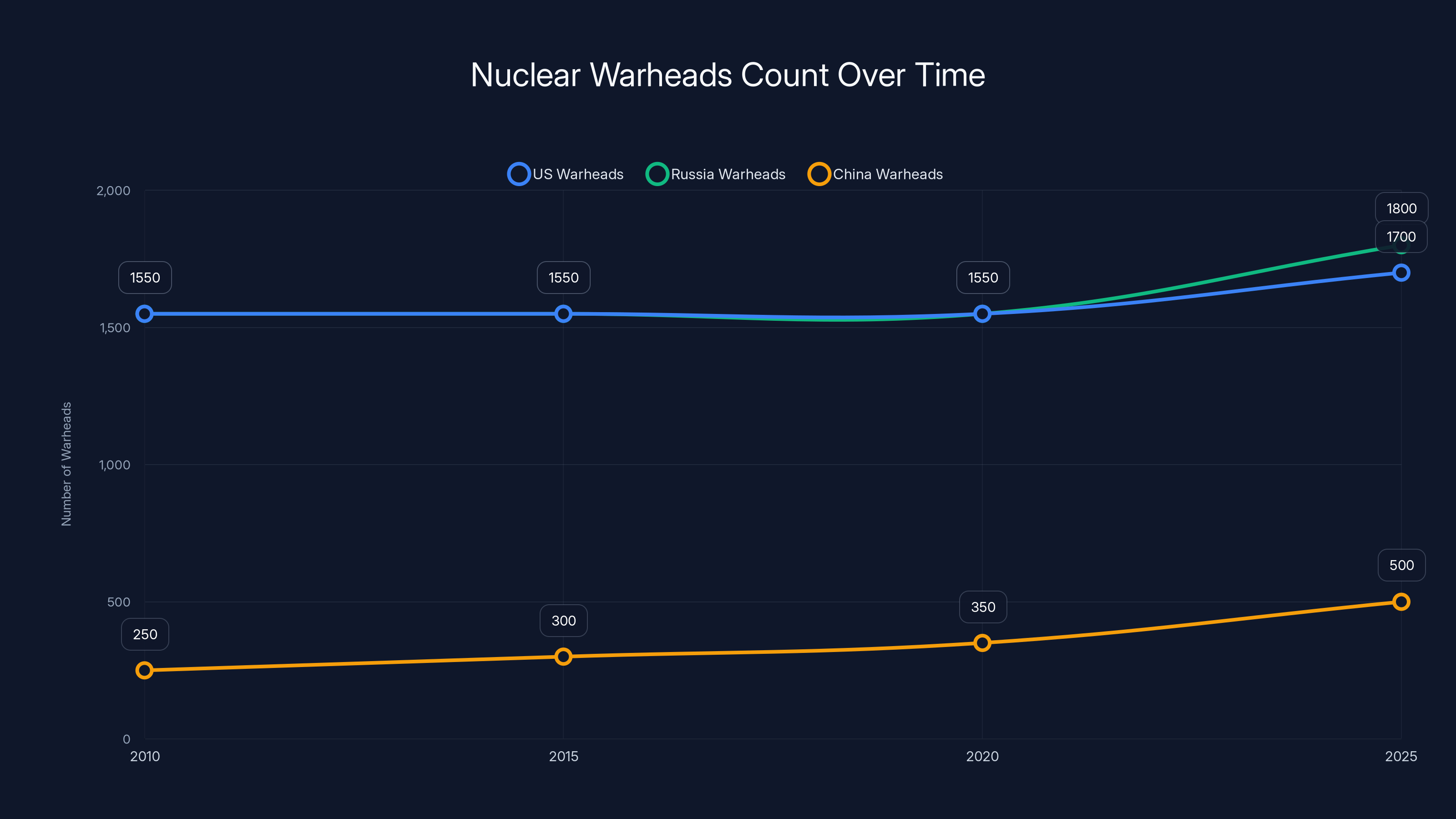

New START was signed in 2010 during the Obama administration. It was supposed to be modest compared to earlier treaties, but it accomplished something significant: it capped deployed nuclear warheads at 1,550 per side for the US and Russia. Arms Control Association highlights the importance of these caps.

That number doesn't sound low. But it was progress. It meant both countries had to verify compliance, conduct on-site inspections, and maintain communication channels even when political relations deteriorated.

For fourteen years, New START held. Both sides complained about it constantly—American hawks said Russia cheated, Russian officials claimed America was spying, which it was, openly and through legal channels—but the treaty survived. It survived the 2016 US election. It survived Trump's threats to withdraw. It survived the Ukraine invasion.

Then it didn't. The agreement expired on February 5, 2025.

Why did it fail? Russia and the US stopped communicating meaningfully. Russia demanded the US remove troops from Eastern Europe. The US demanded Russia withdraw from Ukraine. Neither side trusted the other enough to extend a treaty that requires constant verification. Rather than negotiate, both countries just let it die, as detailed by The Elders.

Within weeks, the weapons announcements started. Russia unveiled new missile tests. China announced plans for 378 new ICBM silos. The Pentagon's budget proposals started allocating massive resources to nuclear modernization programs that had been on pause.

We're not in a new Cold War. We're in a Cold War without the treaties that made it less lethal. The nuclear powers have 12,000 deployed and reserve warheads between them. Nobody's actively threatening to use them—nuclear war is still irrational for all involved—but without verification mechanisms, without inspectors, without agreements on limits, the logic that kept arsenals stable has evaporated.

The US and Russia hold the majority of the world's nuclear arsenal, with over 11,900 warheads combined, vastly outnumbering other nuclear nations.

Here's the Core Problem: Trust Has Collapsed

On-site nuclear inspections sound invasive, because they are. American scientists showing up in Russian military facilities. Russian officials touring American weapons production plants. Both sides handing over detailed information about where weapons are, how many exist, and how they're maintained.

It's an extraordinary amount of transparency, which is exactly why it worked. If you know the other side can walk into your facility whenever they want and count your weapons, you can't cheat. You won't try. The incentive structure forces honesty.

But inspections require something that's become politically toxic: admitting that your adversary has legitimate national security concerns. American lawmakers don't want to explain to voters why Russian inspectors are in Wyoming. Russian officials don't want to explain why Americans are touring their missile plants. Both sides now frame arms control agreements as betrayals of national interest.

And yeah, there's hypocrisy here. Both nations have been modernizing their arsenals anyway, working around the spirit of treaties while following the letter. But the treaties created mechanisms for calling out violations, for escalating concerns, for maintaining dialogue.

Without those mechanisms, you're left with pure national interests and intelligence agencies trying to figure out what the other side is actually doing. That's a much more fragile system.

Korda and his colleagues at the Federation of American Scientists started asking: what if you kept verification but removed the on-site inspectors? What if you used technology instead?

The Proposal: Satellites, AI, and "Cooperative Technical Means"

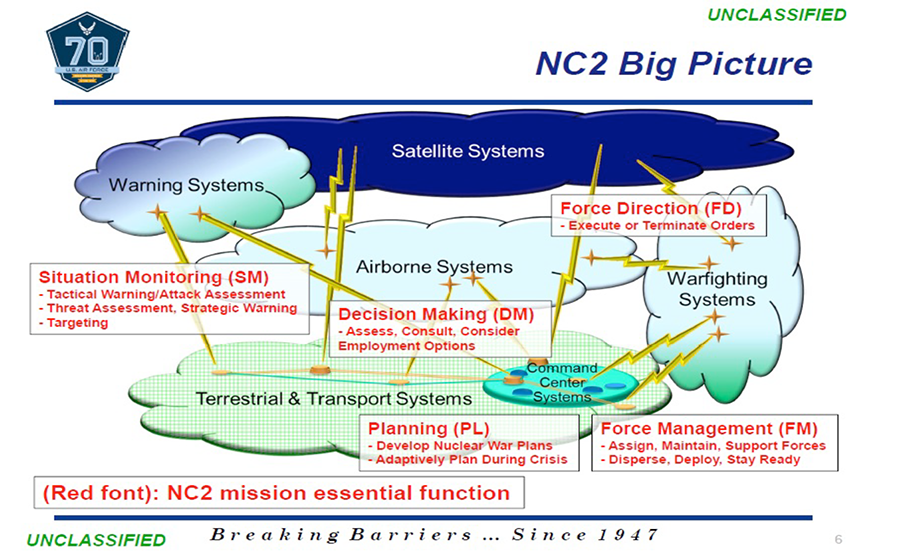

The basic idea is straightforward. Replace human inspectors with satellites and AI systems. Instead of Americans visiting Russian facilities, American satellites fly over Russian territory during pre-agreed windows. Instead of Russians analyzing photos manually, AI systems process the imagery in real-time.

It's called "cooperative technical means" in the arms control world. Both countries agree to participate. Both countries benefit from verification. Neither country has to host foreign inspectors.

Korda and his co-author Igor Morić published a detailed proposal called "Inspections Without Inspectors." The core argument: existing satellite infrastructure, combined with AI pattern recognition, could monitor intercontinental ballistic missile silos, mobile rocket launchers, submarine activity, and plutonium pit production facilities.

Here's how it might work in practice:

A new treaty would stipulate that Russia agrees to open specific missile silo hatches on specific dates when American satellites are passing overhead. No inspectors needed. The satellite takes photos. AI systems analyze the imagery to verify that the silo contains what the treaty says it should contain. If something looks wrong, humans review the data and escalate concerns.

Similarly, the US would agree to the same verification for its own facilities. Mutual transparency without mutual presence.

It's elegant. It uses technology that already exists. It doesn't require either side to admit that foreign inspectors on their soil is acceptable. And it theoretically maintains verification capabilities.

But elegance and feasibility are different things.

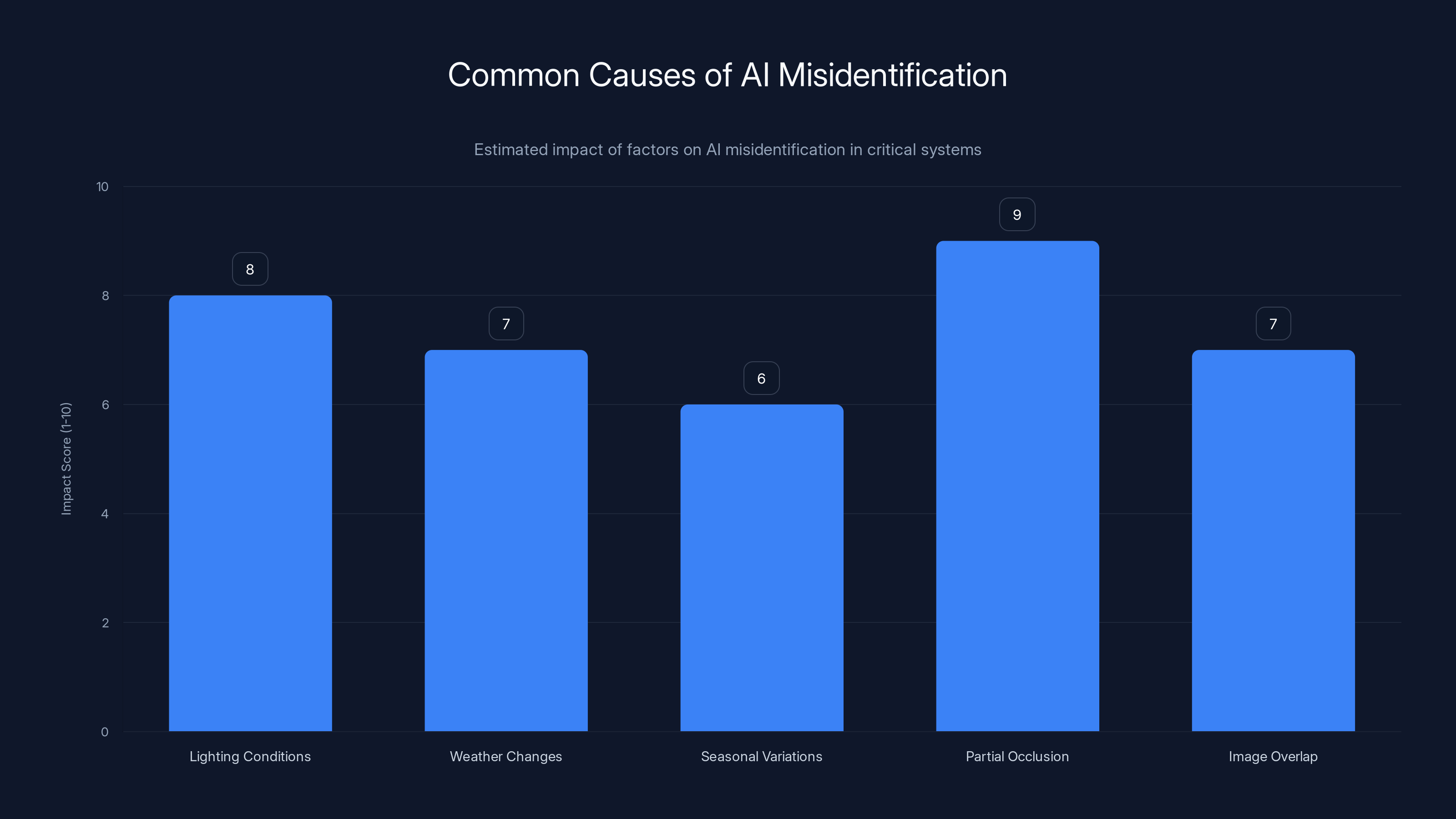

Partial occlusion and lighting conditions are major contributors to AI misidentification, highlighting the need for robust verification protocols. (Estimated data)

The AI Problem: Pattern Recognition Needs Data

Artificial intelligence is genuinely good at one thing: pattern recognition. If you feed an AI system thousands of labeled examples, it can learn to spot patterns in new data it hasn't seen before. Image recognition AI trained on millions of photos can identify cats. Medical AI trained on millions of X-rays can spot tumors. In theory, AI trained on nuclear weapons data could identify warheads.

In theory.

The problem is data. Nuclear weapons are not common objects. Nobody's publishing high-resolution satellite imagery of their ICBM silos on the internet. You can't just scrape Google Images and train a model. You need "bespoke datasets," as Korda says—custom-built libraries of examples specific to each country's weapons systems.

And even then, there's enormous variation. Russian ICBM silos look different from American ones. Chinese silos differ from both. Within countries, there are differences too. A silo built in the 1970s doesn't look identical to one built in the 2010s.

Sara Al-Sayed from the Union of Concerned Scientists has been building these datasets for a forthcoming study. She points out that the scope is massive. You're not just identifying "is there a missile?" You're tracking launchers, bombers, submarines, production facilities, test sites, storage facilities, maintenance operations, dismantlement operations. Then you're tracking every object at those sites.

"You really need to think at that granular level of all the objects," Al-Sayed told WIRED.

And even then, what task is the AI actually performing? Is it detecting the presence or absence of an object? Classifying what it's seeing? Tracking changes over time? Each task requires different training, different data, different verification standards.

You can't just point a camera at a weapons facility and ask AI "is this compliant with the treaty?" The AI doesn't understand treaties. It understands patterns. You have to define, precisely, what patterns indicate compliance versus violation.

The Infrastructure Already Exists: Satellites Are Everywhere

One advantage of the proposal: you don't need to build new satellites. Commercial satellite imaging is already a multi-billion-dollar industry.

Google Earth, Planet Labs, Maxar, and dozens of other companies are constantly imaging the planet. Some imagery is classified, some is public. The resolution varies—commercial satellites can achieve roughly 10-30 centimeters per pixel depending on the company and imaging type.

For nuclear verification purposes, that resolution is adequate. Missiles are large. Silos are massive. Mobile launchers are visible. You don't need to read text on a facility; you need to identify which facility is active, whether equipment is present, and whether activity patterns match the treaty baseline.

The US military already uses satellite imagery extensively for intelligence. The National Reconnaissance Office operates classified spy satellites with resolution that commercial systems can't match. If the US wanted to monitor Russian nuclear facilities with existing technology, it could.

Russia and China have satellite capabilities too, though not at American levels. But even lower-resolution satellite imagery, combined with AI analysis and human review, could provide more visibility than zero oversight.

The infrastructure exists. The tech exists. The problem isn't capability. It's cooperation and trust.

The Cooperation Problem: Why Countries Won't Agree

Here's the critical flaw in the proposal: it requires voluntary participation from nations that actively want to hide weapons development.

The proposal assumes that Russia and the US, and potentially China and other nuclear powers, would agree to:

- Allow satellites to fly over their territory on pre-agreed schedules

- Open facilities on demand for imagery collection

- Accept AI-based verification of their weapons systems

- Submit to human review if violations are suspected

- Maintain this cooperation even when political relations deteriorate

That's a lot to ask from countries that are currently backing opposing sides in proxy wars.

Korda acknowledges this. "The idea was, what if there was a sort of middle ground between having no arms control and just spying, and having arms control with intrusive on-site inspections which may no longer be politically viable?" he said.

But the proposal assumes that countries prefer transparency over secrecy. In reality, military establishments prefer secrecy. Always. The on-site inspection regime only worked because the alternative—no verification at all—was worse. Countries chose limited transparency over strategic uncertainty.

Without political will to negotiate a replacement treaty, the technology doesn't matter. Russia and the US could theoretically both agree to satellite verification tomorrow. They won't, because:

Russia sees nuclear arms control as a geopolitical lever. By letting New START die, Russia signals that it's pursuing an aggressive military posture and expects the West to respond. Agreeing to AI-monitored verification would undermine that posture.

The US faces domestic political pressure from lawmakers who view any arms control agreement as weakness. Even if the Biden or a future administration wanted to negotiate new treaties, Congress would block it.

China won't participate in any verification regime, because China isn't a major signatory to existing treaties and views opacity as a strategic advantage, as discussed by the Quincy Institute.

So you're left with a technically sound proposal that has no political pathway to implementation.

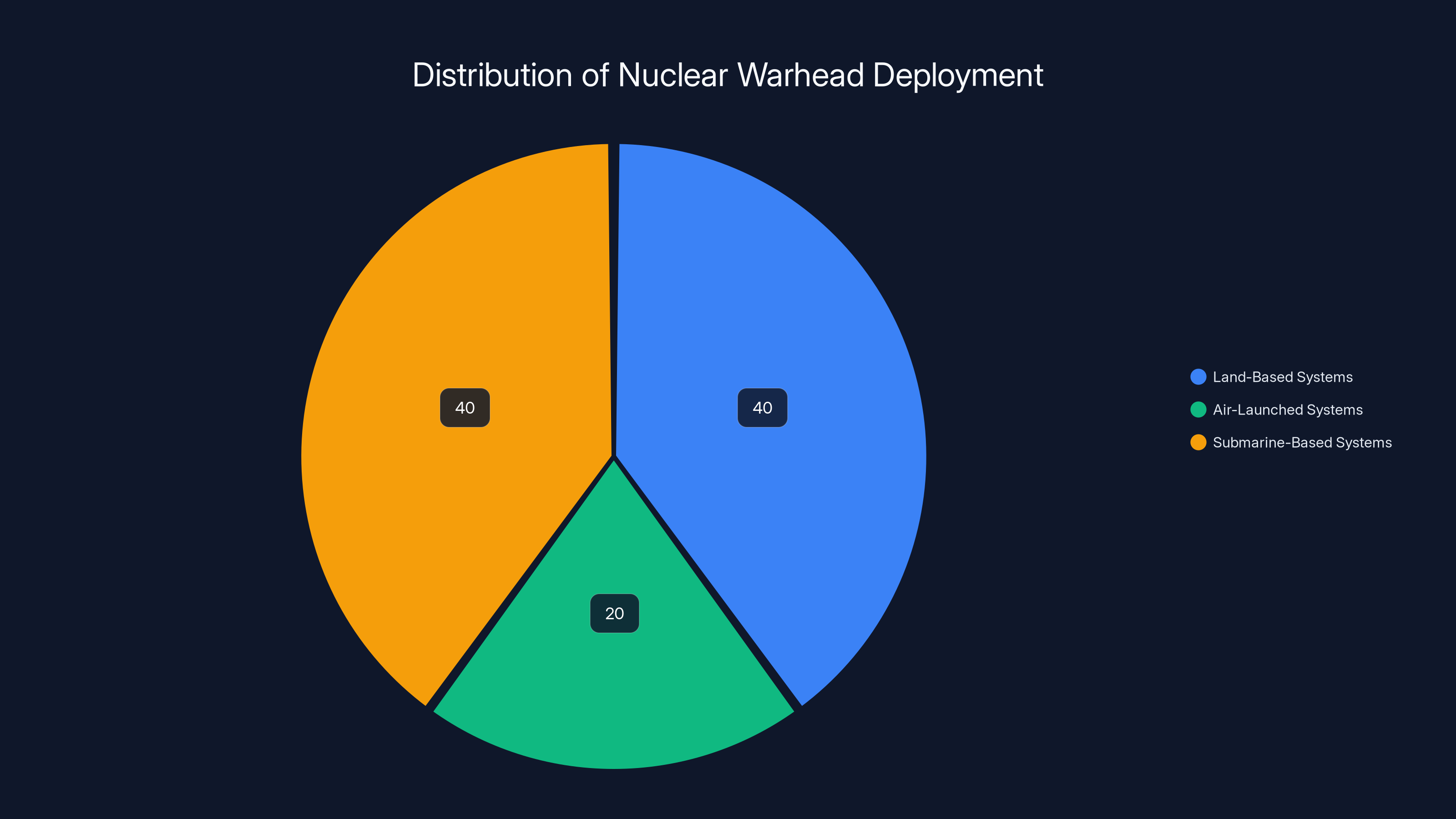

Submarine-based systems account for an estimated 40% of nuclear warhead deployment, highlighting their critical role in strategic deterrence. Estimated data.

When AI Gets It Wrong: The Misidentification Danger

Let's assume, somehow, that countries agreed to AI-based verification. New problem: what happens when the AI is wrong?

Computer vision AI, despite impressive accuracy on benchmarks, fails in the real world regularly. Different lighting conditions, weather, seasonal changes, partial occlusion—all of these cause misidentification. An AI trained to identify missiles might confidently identify a road-building machine as a mobile launcher. It happens.

In medical imaging, AI errors can be reviewed by a doctor. In nuclear arms control, AI errors could trigger diplomatic crises.

Imagine an AI system, analyzing satellite imagery of a Russian facility, concludes that a missile deployment has increased beyond treaty limits. It flags the anomaly. Humans review it. But the humans are the ones that disagree—maybe the AI misidentified trucks as launchers, or counted the same vehicles twice due to image overlap.

Now you have a verification system flagging a non-existent violation. Russia denies the violation. The US insists the data shows otherwise. Do you escalate? Do you demand an inspection? Do you assume the AI made an error and move on?

Without established protocols for resolving AI-generated disputes, the system breaks down. And these protocols are hard to establish, because countries would need to agree on what counts as a false positive, how to verify disputed findings, and what happens if verification can't be achieved.

That's basically the entire on-site inspection regime again, just with extra steps.

The Human Review Problem: Who Decides?

The proposal includes human reviewers because everyone acknowledges that AI alone can't make weapons verification decisions. Humans review the AI's findings before anything is escalated.

Sounds good. But who are these reviewers? Are they independent scientists or government officials? Do they have security clearances? Can they actually view the underlying satellite data or just the AI's interpretation?

And here's the really complicated part: if the US and Russia both need to agree on verification results, then you need reviewers from both countries. That means Russian officials are reviewing American weapons data and vice versa. If they disagree, who breaks the tie?

On-site inspections worked partly because inspectors came from neutral countries or were bound by international protocols. Human reviewers in an AI verification system would be nationals of the countries being verified. Conflict of interest is built in.

You could theoretically establish an independent international body to review disputed findings. But that body would need to have authority over national governments, which no country has agreed to. And it would need technical expertise to understand satellite imagery, AI systems, and nuclear weapons—a combination of skills that's rare.

Basically, you'd be building a new international institution with more power than currently exists. That's not a technical problem; it's a political one.

China's Arsenal: The Verification Crisis

Here's where the proposal really breaks down: China.

China has the third-largest nuclear arsenal in the world—roughly 400-500 warheads, compared to America's 5,800 and Russia's 6,100. But China hasn't been part of major arms control treaties. They're not signatories to New START or its predecessors. They've successfully kept their arsenal opaque.

That opacity is intentional. China's strategy relies partly on uncertainty. The US can't be sure how many weapons China has, what their capabilities are, or how quickly China can expand. That uncertainty is a feature for China, not a bug.

If you tried to implement AI-based verification with American, Russian, and Chinese cooperation, China would need to agree to the system. China won't. They've made clear that they see nuclear secrecy as a strategic necessity.

So the proposal works only for two countries: the US and Russia. And it only works if they both agree that transparency is preferable to the current situation.

Given that Russia just let a major treaty die and is building new weapons systems, Russia doesn't seem to believe transparency is preferable. So we're back to zero cooperation.

Estimated data shows a stable count of nuclear warheads for the US and Russia under New START until 2025, when numbers begin to rise post-treaty expiration. China's arsenal shows a gradual increase.

What About Submarine-Based Missiles? The Invisible Arsenal

Most focus on AI verification centers on land-based systems. ICBM silos are stationary and visible from space. Mobile launchers can be tracked. Production facilities leave thermal signatures.

But submarines are different. Submarines are specifically designed to be undetectable. A Ohio-class submarine can carry 24 nuclear missiles. The US operates 18 of them. Russia operates roughly a dozen. Neither country is going to agree to satellite monitoring of submarines, because underwater platforms are the whole point of a "second strike" deterrent. If you can monitor submarines, you can theoretically sink them in a surprise attack.

Submarines are the reason mutually assured destruction worked as a stability mechanism. Even if Russia wiped out American land-based missiles and air-launched missiles, American submarines would still be at sea, undetected, capable of ending Russian civilization in retaliation.

Whole fleets of submarines are invisible by design. No satellite can monitor them. No AI system can track them. Submarine-based deterrents fall outside any verification system based on optical surveillance.

That's actually fine—submarines are stable. You don't need to monitor something you can't. But it means any AI-based verification system is incomplete. It covers maybe 60% of deployed warheads, leaving massive gaps.

Those gaps create strategic uncertainty. And strategic uncertainty, with no treaty framework to manage it, increases the risk of miscalculation.

The Alternative: Back to Espionage and Guesswork

If AI-based verification doesn't work, what's the fallback?

It's basically what we're doing now: intelligence agencies spying on each other, making estimates based on incomplete data, and hoping they're right.

American intelligence agencies are incredibly sophisticated. The National Reconnaissance Office runs spy satellites that can resolve objects the size of a golf ball. The NSA intercepts communications. The CIA has human sources. Combining all these, American intelligence has decent visibility into Russian weapons systems.

Russian intelligence has much less visibility into American systems, which is partly why Russia was willing to let New START expire—they believe the asymmetry favors them in a world without treaties.

Without verification mechanisms, both sides rely on estimates. The government says "we assess that Russia has X number of deployed warheads." How do they assess that? Through decades of intelligence work, satellite monitoring, and nuclear weapons expertise. It's fairly accurate, but it's not perfect.

More importantly, the other side doesn't believe those estimates. Russia thinks America is lying. America thinks Russia is cheating. Without independent verification, you get an environment of suspicion.

That suspicion can lead to threat inflation. "We don't know what Russia's doing, so we'll assume the worst and build accordingly." That's rational from a military planning perspective and catastrophic from a stability perspective. Both sides end up building faster than they otherwise would, driving renewed arms race.

We've seen this movie before. It's not great. It ended the Cold War through mutual exhaustion, not rational decision-making.

What Would Actually Have to Change for This to Work

For AI-based verification to replace on-site inspections, you'd need:

Political will from nuclear powers. This is the prerequisite. The US, Russia, China, and potentially other nuclear powers would need to decide that transparency is preferable to opacity. Given current geopolitics, that's not happening.

Comprehensive data on each country's weapons systems. You'd need detailed imagery of how each nation deploys, maintains, and stores weapons. This data would need to be collected, labeled, and shared across borders. Building this dataset would essentially require countries to already be cooperating.

Agreement on verification standards. What counts as a violation? If an AI system flags a potential issue, what evidence is required to prove it's real? What evidence proves it's a false positive? These need to be negotiated in advance and agreed to by all parties.

Independent dispute resolution. When the AI flags something contested, who decides if it's a real violation? You need an impartial body with authority to investigate and make determinations. That body doesn't exist.

Acceptance of technological uncertainty. The system won't be perfect. Errors will happen. Countries would need to accept those errors and not escalate every false positive into a diplomatic crisis. That requires extraordinary trust.

Inclusion of all nuclear powers. The system doesn't work if one major nuclear power opts out. China's absence undermines the entire framework.

None of these things are possible right now. Most of them weren't possible even during the Cold War, when there was structured dialogue and recognized rules of engagement.

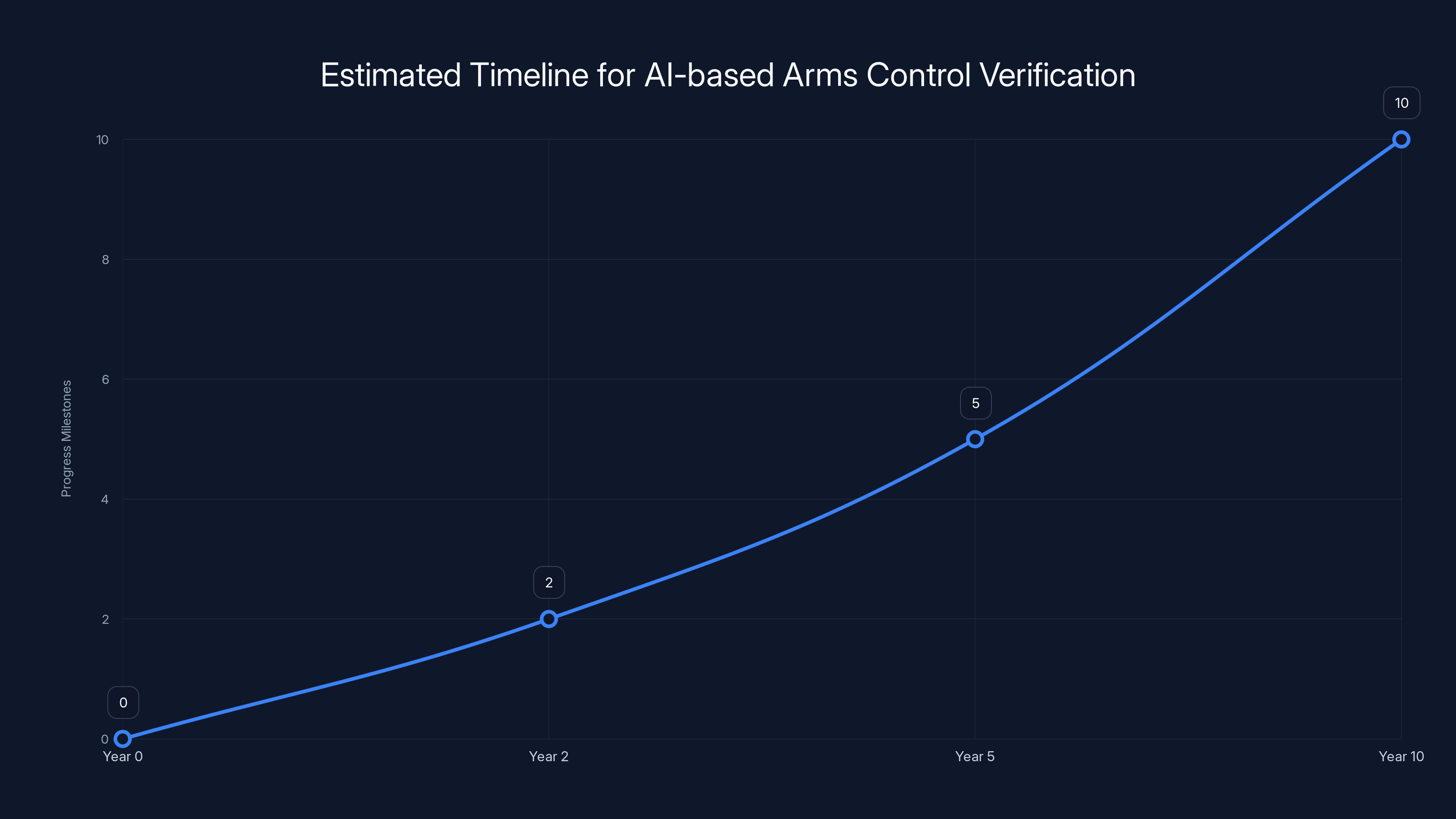

Estimated timeline for implementing AI-based verification in arms control is 5-10 years, assuming political commitment and international cooperation.

Why Humans Still Matter: The Intelligence Wild Card

One thing AI can't replicate is the deep domain expertise of nuclear weapons specialists. When an analyst looks at satellite imagery of a Russian facility, they're not just processing pixels. They're drawing on decades of knowledge about how Russia has deployed weapons historically, how weapons systems evolve, how facilities change seasonally.

An AI system trained on labeled examples can do pattern matching, but it doesn't have that contextual knowledge. It doesn't know that a particular facility was modernized in 2019, so changes from 2019 to 2024 might be expected. It doesn't know the seasonal rhythms of weapons operations or how different branches of the military operate differently.

Human analysts integrate all this contextual information. They ask questions that don't have obvious answers: "Why is that facility active now when it's typically inactive in winter?" "Why is this launcher deployed differently than it was three years ago?" "Could this be a deception operation?"

AI can flag anomalies. Humans decide whether anomalies matter. That partnership is valuable.

But it only works if the humans are independent reviewers, not officials of the countries being monitored. And if you have independent reviewers from neutral countries, you're building the institutional structure that never existed during arms control.

The Economic Angle: Who Profits from This?

There's a business interest in promoting AI-based verification.

Satellite companies benefit from more contracts to provide monitoring imagery. AI companies benefit from opportunities to develop and deploy weapons verification systems. Defense contractors benefit from the resulting military modernization spending.

This isn't a conspiracy—it's natural. But it means that the people most vocally advocating for AI-based verification have financial incentives to see it adopted. That doesn't make the proposal wrong, but it's worth noting when evaluating claims about how practical the system is.

Historically, arms control treaties have been driven by political leadership, not technology providers. The Limited Test Ban Treaty, the Nonproliferation Treaty, New START—these were negotiated because political leaders decided they were necessary, then the technology was assembled to verify them.

The current proposal inverts that sequence. It's technology-first, looking for a political problem to solve. That rarely works in international relations.

What Comes Next: The Worst-Case Scenario

Let's be direct. Without a new arms control framework, the next decade probably looks like accelerating weapons development.

Russia will continue modernizing its arsenal. The US will do the same, partly in response and partly because the military-industrial complex always argues for more spending. China will expand its arsenal, partly to maintain rough parity with the US and Russia.

France and the UK have smaller arsenals but will maintain them. India and Pakistan have roughly 160 and 170 warheads respectively and are developing new delivery systems. Israel's arsenal remains opaque but substantial. Iran is pursuing nuclear weapons and continues to argue that Western nuclear powers should disarm first.

Without verification mechanisms, without shared understanding of arsenals, without negotiated limits, this becomes a tragedy-of-the-commons situation. Each country, maximizing its own security, undermines collective security.

The risk isn't that any country is crazy enough to use nuclear weapons in a major war. Nuclear war is irrational for everyone involved. The risk is accidental nuclear war, escalation spirals, miscalculation.

Without the communication channels that arms control treaties provided, without the transparency that reduced misunderstanding, the probability of catastrophic miscalculation increases.

That's not fear-mongering. That's the assessment of weapons analysts and former military officials. When you remove stabilizing mechanisms, you increase instability. That's not controversial.

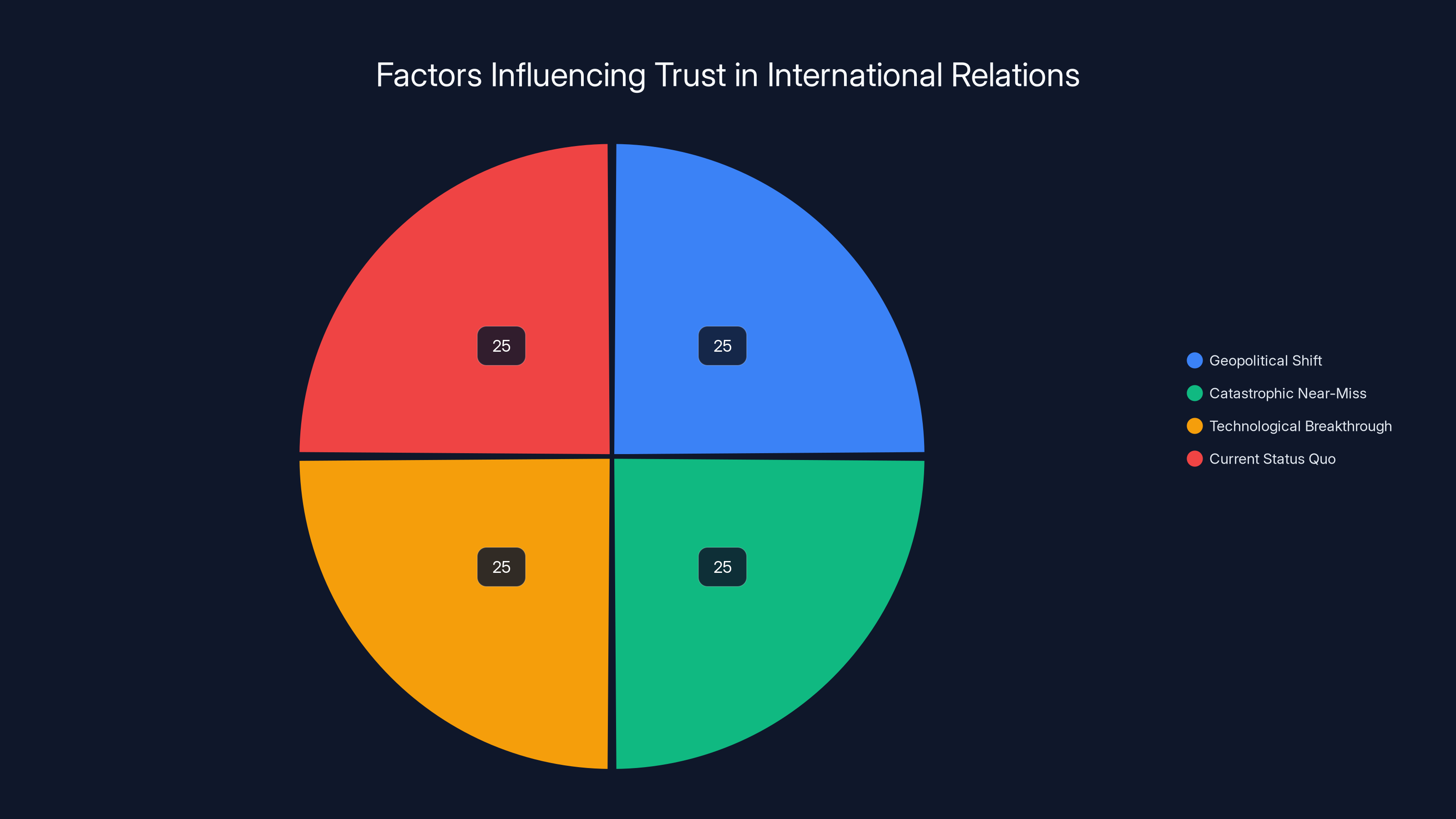

Estimated data suggests that geopolitical shifts, catastrophic events, and technological breakthroughs equally impact trust-building, but the current status quo maintains a significant influence.

Could Smaller Agreements Work?: A Middle-Ground Approach

Maybe the answer isn't replacing New START entirely. Maybe it's building incremental agreements on specific issues.

For instance, a US-Russia agreement on maintaining strategic stability communication channels. Basically, keeping the phone line open and agreeing to share information about weapons tests or potential misunderstandings.

Or an agreement to limit specific categories of weapons. Not a comprehensive arms control regime, but targeted restrictions on the most destabilizing systems.

These wouldn't be as comprehensive as New START. But they'd restore some structure to the US-Russia nuclear relationship without requiring the massive political transformation needed for AI-based verification.

The problem is that Russia currently has incentives to avoid such agreements. Russia benefits from uncertainty and from signaling that it's willing to pursue military escalation. Agreeing to limits or communication protocols would undermine that signal.

Unless something changes in Russia's strategic calculus—a change in leadership, a shift in the war in Ukraine, a reevaluation of whether military escalation is sustainable—Russia's unlikely to negotiate.

Which means we're probably stuck in the current equilibrium for at least the next few years: no treaties, continued modernization, and hope that nobody does anything catastrophically stupid.

That's not a stable long-term solution.

The Lessons from Previous Arms Control Successes

Why did New START and its predecessors work at all?

Partly because both sides believed mutual vulnerability was preferable to mutual uncertainty. An American president and a Russian president could both accept that "if you attack us, we will destroy you." That created a stable deterrent.

Partly because there were institutions and protocols. The Standing Consultation Commission met regularly to discuss treaty interpretation. Verification procedures were clearly defined. Both sides had been building these relationships for decades.

Partly because the alternative was visibly worse. The Cuban Missile Crisis demonstrated what happens without shared understanding. Nuclear strategists spent decades building frameworks to prevent another crisis.

And partly because even competing powers can recognize that some things are mutually bad. Neither the US nor Russia wanted global nuclear war. That shared interest enabled cooperation.

That shared interest still exists. Neither side wants nuclear war. But the institutional mechanisms that translated that shared interest into arms control agreements have been dismantled.

Rebuild those mechanisms, and you might have a foundation for new agreements—whether AI-based verification or something more traditional.

Without those mechanisms, technology proposals are window dressing. You're not really addressing the problem.

The Future of Nuclear Security: Where We Actually Are

Here's the reality: we're probably not getting a comprehensive new nuclear arms control treaty anytime soon.

The US and Russia are hostile. Their interests are opposed in multiple regions. There's no political leadership in either country strongly pushing for negotiated agreements. The institutions that supported arms control have atrophied.

In this environment, countries will do what countries do: they'll pursue their own security interests. That means modernizing weapons. It means developing new delivery systems. It means trying to maintain strategic advantage.

AI-based verification is a creative proposal for a world that doesn't currently exist—a world where countries want transparency. In our actual world, where countries want opacity, the proposal is mostly irrelevant.

It could become relevant if political conditions change. If a new administration in the US decides arms control is a priority, if Russia's war in Ukraine ends and opens space for negotiation, if international institutions rebuild, then AI-based verification becomes a practical option.

But that requires political change first. Technology follows politics, not the reverse.

What People Are Getting Wrong About This Proposal

There are a few common misconceptions worth addressing.

Misconception 1: AI can verify weapons alone. No. AI is a tool for processing data. Verification requires judgment calls that AI can't make. Humans are essential.

Misconception 2: Satellite imagery alone is sufficient. No. Satellites see surface-level activity. They don't see underground facilities directly. They don't see deception operations. Verification requires multiple intelligence streams.

Misconception 3: Countries prefer transparency. They don't. Countries prefer security and strategic advantage. Transparency is accepted only when it's believed to be mutually stabilizing.

Misconception 4: This solves the trust problem. It doesn't. It potentially reduces the trust required by providing independent verification. But countries still need to trust that the system is fair and not biased against them.

Misconception 5: Technology is the main barrier. It's not. Technology exists. Politics is the barrier.

Pathways Forward: What Would Actually Need to Happen

If you wanted to implement AI-based verification, here's what would actually need to happen:

First: Political leadership from the US and Russia (and potentially China) would need to publicly commit to arms control negotiations. This is a political choice, not a technical one.

Second: Negotiators would need to hammer out the basic framework. What weapons are covered? What counts as compliance? What happens if violations are suspected?

Third: Both countries would need to provide the underlying data needed to train AI systems. This is the scary part for countries, because it requires sharing detailed information about weapon systems.

Fourth: International teams of weapons experts would need to develop and test AI systems. These teams would need to include scientists from multiple countries, with transparent methodologies.

Fifth: Both countries would need to agree to the verification process and accept results, even when results are inconvenient.

None of these steps is technically infeasible. All of them are politically difficult. Most of them require a level of international cooperation that's currently absent.

Estimate on timeline: if political conditions changed tomorrow and countries decided this was a priority, you're looking at 5-10 years to develop the frameworks, train the systems, and build the institutional capacity to operate them. That's not fast.

The Real Question: What Happens If We Don't Do This?

That's the critical question. If AI-based verification doesn't happen, or if it's proposed but never implemented, what's the alternative?

Basically, we're back to the 1950s model. Mutual deterrence based on assured destruction. Both sides building weapons because they can't verify compliance. Strategic instability rooted in uncertainty.

That system worked, sort of, during the Cold War. The Cuban Missile Crisis showed how close we came to catastrophic miscalculation. And we had regular communication channels, de-escalation protocols, and shared understanding that war was bad for both sides.

We have less of that now.

Without arms control frameworks, without verification, without transparent communication, the probability of accident increases. Maybe not dramatically in any given year. But over decades, small probability events accumulate.

That's the case for AI-based verification, or for any arms control at all. It's not that verification prevents weapons development. It's that verification reduces the risk of catastrophic miscalculation.

We're currently accepting higher risk in exchange for avoiding the political costs of arms control. That's a choice. Whether it's a wise choice is debatable.

Building Back Trust: Is It Even Possible?

Here's the deepest question: can you build trust through technology when the political relationship is broken?

The proposal assumes technology can replace trust. AI systems don't care about geopolitical tensions. Satellites don't care about ideology. Data analysis is objective.

But verification only works if both sides trust the system itself. If Russia believes the AI is biased against them, they won't accept results. If the US believes Russia is gaming the system, verification becomes irrelevant.

Trust in the system requires that the system be perceived as fair. That's hard to achieve when the underlying political relationship is adversarial.

Historically, arms control worked because there was explicit recognition that both sides had common interest in stability. That recognition doesn't currently exist. Russia views arms control as a constraint on its power. The US views unverified Russian weapons as a threat. Neither side sees verification as mutually beneficial.

To change that, you'd need either:

- A dramatic shift in geopolitical relationships (peaceful resolution of Ukraine, diplomatic normalization, etc.)

- A mutually catastrophic near-miss that convinces leadership that cooperation is necessary

- A technological breakthrough that makes secrecy impossible (like universal AI surveillance), forcing transparency

None of these seem likely in the next few years.

What Should Policymakers Actually Do?

If I were advising a government, here's what I'd recommend:

Invest in AI verification research anyway. Not because it will solve the current problem, but because it might be useful in a better future. Build the technical capacity now. When political conditions change, you're ready.

Maintain communication channels with adversaries. Even without formal treaties, keep dialogue open. Cold War-era deconfliction mechanisms prevented accidents. We need similar systems now.

Pursue smaller, targeted agreements on specific stability measures. Not comprehensive arms control, but things that directly reduce miscalculation risk. Like agreements on weapons testing notifications or crisis communication protocols.

Build alternative verification mechanisms. If on-site inspections aren't politically viable and AI systems aren't ready, use combinations of satellite imagery, signals intelligence, open-source information, and human networks.

Accept higher costs in military spending and strategic uncertainty. If you can't have verification, you have to build larger arsenals to account for worst-case scenarios. It's expensive. That's the price of failing to negotiate.

Keep advocating for arms control even if it seems hopeless. Political conditions change. When they do, you want to have people ready to negotiate. The infrastructure of arms control knowledge is fragile. We're losing it as Cold War-era experts retire.

That last point matters more than it seems. The people who know how to negotiate nuclear treaties, who understand the technical details of verification, who have relationships built over decades—they're aging out. If we don't preserve that institutional knowledge, rebuilding it becomes even harder.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Nuclear Security Today

Let me be blunt. The world is probably less safe today than it was a year ago.

We lost the last major arms control framework. Both superpowers are building weapons. China is expanding. Smaller nuclear powers are modernizing. There's less transparency, less communication, less institutional structure to manage conflict.

AI-based verification, if implemented perfectly, could help restore some of that structure. But perfect implementation requires political will that doesn't currently exist.

So we're not getting AI-based verification. We're not getting new comprehensive arms control treaties. We're probably not even getting targeted agreements in the near term.

We're getting strategic uncertainty, accelerating modernization programs, and hope that nobody makes a catastrophic mistake.

That's not reassuring. But it's accurate.

The proposal about AI and satellites is creative. It's technically plausible. It might even work if political conditions were different. But conditions aren't different. And wishes about how things could be don't change how things are.

A Brief on What Optimists Get Right

Despite the skepticism above, there's one thing the optimists get right: technology does matter eventually.

If you can develop AI systems that reliably verify weapons compliance, that's valuable technology that might become politically viable in a future era. Building that technology now, establishing proof of concept, demonstrating that verification is feasible—that creates options for future leaders.

Technology doesn't cause political change, but it enables it. If verification becomes trivially easy through AI, if transparency becomes cheap to verify, then countries face different incentives. Maybe they decide transparency is acceptable.

That's speculative. But it's plausible.

So there's value in the research, even if it doesn't solve the current crisis. The real weapons control treaty of 2035 might use AI systems developed in 2025. The frameworks being built now for a world that doesn't exist might be essential infrastructure for a world that eventually does.

That's not optimism about the near term. It's pessimism about the near term combined with pragmatism about the future.

Final Thoughts: Where We Go from Here

The proposal to use AI and satellites to replace nuclear inspectors is a response to a genuine crisis. The last major treaty expired. Arms control infrastructure is crumbling. Nuclear powers are building weapons again.

The proposal itself is technically reasonable. It's just not politically viable right now.

Changing that viability is primarily a political problem. Build the technology. Keep advocating for cooperation. Maintain the expertise. Wait for political conditions to shift.

It's not exciting. It's not a technological solution to a fundamentally political problem. But it's probably the best available approach.

In the meantime, we're living in a world with more nuclear weapons, less verification, and more strategic uncertainty than we had a year ago. We should probably think seriously about that.

FAQ

What was New START and why did it expire?

New START was a 2010 arms control treaty between the US and Russia that limited deployed nuclear warheads to 1,550 per side and included on-site verification measures. It expired in February 2025 when Russia and the US failed to negotiate an extension, primarily because political relations had deteriorated and neither side trusted the other enough to continue the agreement, as noted by NTI.

How many nuclear weapons currently exist in the world?

Approximately 12,000 deployed and reserve nuclear warheads exist globally, primarily held by the US and Russia (5,800 and 6,100 respectively). China has around 400-500, France and the UK have roughly 290 and 215, and other nations have smaller arsenals. This represents roughly an 80% reduction from the 1985 peak of over 60,000 weapons, as reported by Statista.

Can AI actually verify nuclear weapons compliance?

AI can help identify patterns in satellite imagery and flag potential compliance issues, but it requires extensive training data, human review, and agreement on what constitutes a violation. AI alone cannot verify compliance—it's a tool that assists human experts in analyzing satellite imagery and identifying anomalies for further investigation.

Why don't countries just allow on-site inspectors anymore?

On-site inspections require countries to allow foreign military personnel access to sensitive weapons facilities, which modern governments view as politically unacceptable. International tensions have also increased, making countries less willing to accept that level of transparency. The proposal for AI-based verification exists partly because it avoids the political cost of hosting foreign inspectors.

What would need to change for AI verification to actually work?

Countries would need to agree to participate in a verification regime, share detailed data about their weapons systems, establish independent review processes, and accept the results even when they're inconvenient. Most critically, there would need to be political will to negotiate and implement such a system, which currently doesn't exist.

How does satellite imagery resolution affect nuclear verification?

Commercial satellites can achieve 10-30 centimeters per pixel resolution, which is adequate for identifying large weapons systems like ICBM silos and mobile launchers. However, submarines remain undetectable from space, creating gaps in any optical verification system. More detailed verification would require additional intelligence sources.

Can China be included in a nuclear verification system?

China has not participated in major arms control treaties and views nuclear opacity as strategically important. China is unlikely to agree to any verification regime, which creates a major gap in any proposal for global nuclear verification.

What happens if nuclear verification systems detect anomalies or violations?

The proposal assumes human reviewers would assess findings and escalate concerns through diplomatic channels. However, without established protocols for dispute resolution and verification procedures, countries could easily dispute findings and accuse verification systems of bias, potentially making the system ineffective.

How would AI systems be trained for nuclear weapons recognition?

AI would need extensive labeled datasets showing how each country deploys, maintains, and stores weapons systems. These "bespoke datasets" would need to be built by nations that currently distrust each other, and would require sharing sensitive military information. The data requirements are enormous and remain a major barrier to implementation.

What's the risk of inaccuracy in AI-based nuclear verification?

AI systems can misidentify objects in satellite imagery due to weather, lighting, seasonal changes, or deception operations. A false positive flagging non-existent violations could trigger diplomatic crises, while false negatives could miss real violations. Error rates would need to be extraordinarily low for the system to be trusted.

Key Takeaways

- New START, the last major US-Russia nuclear arms control treaty, expired in February 2025 after 14 years of verifying weapon limits.

- Researchers propose using AI and satellite imagery to monitor nuclear weapons remotely, replacing on-site inspectors with automated systems.

- AI verification faces critical barriers: lack of training data, political distrust, technical limitations identifying submarines, and absence of dispute resolution mechanisms.

- The proposal requires unprecedented cooperation between adversarial nations and agreement on verification standards that simply doesn't exist.

- Without new treaties, the world faces an accelerating nuclear arms race with less transparency, more strategic uncertainty, and higher risk of miscalculation.

Related Articles

- GPT-5.3-Codex: The AI Agent That Actually Codes [2025]

- ChatGPT Caricature Trend: How Well Does AI Really Know You? [2025]

- OpenAI GPT-5.3 Codex vs Anthropic: Agentic Coding Models [2025]

- Larry Ellison's 1987 AI Warning: Why 'The Height of Nonsense' Still Matters [2025]

- Modern Log Management: Unlocking Real Business Value [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

![AI and Satellites Replace Nuclear Treaties: What's at Stake [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-and-satellites-replace-nuclear-treaties-what-s-at-stake-2/image-1-1770638890756.jpg)