AI Recreation of Lost Cinema: The Magnificent Ambersons Debate and the Future of Digital Restoration [2025]

Introduction: When Technology Meets Artistic Legacy

Imagine discovering that one of cinema's greatest masterpieces was deliberately mutilated, its best scenes permanently destroyed, and the artist's original vision lost forever to time and studio politics. This isn't a hypothetical—it's the actual fate of Orson Welles' "The Magnificent Ambersons," a film Welles himself considered superior to "Citizen Kane." In 2025, a startup called Fable announced an audacious plan to resurrect the 43 minutes of footage that were excised from the film's original cut and destroyed by the studio to make storage space in their vaults. The method? Generative artificial intelligence.

When the announcement first surfaced, the reaction was swift and predictable. Cinephiles recoiled. Film purists condemned it as sacrilege. Critics questioned whether this was technological progress or just another example of Silicon Valley overreach, attempting to solve problems that shouldn't be solved with the tools we have available. The emotional response made sense—Welles is a towering figure in cinema history, and "The Magnificent Ambersons" represents one of art's great tragedies: a visionary work crippled by institutional shortsightedness.

But here's the thing that shifted my perspective slightly: after learning more about the project through in-depth reporting and understanding the genuine passion driving it, I realized the situation is far more nuanced than "AI bad" or "restoration good." This isn't a straightforward ethical question with a clear right answer. Instead, it's a complex intersection of technology, artistic legacy, legal rights, and fundamental questions about what we owe to lost art.

The Fable project forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about AI in creative domains. Can artificial intelligence authentically recreate a human artist's vision, or is it inherently creating something entirely new and replacing the original with a simulacrum? If lost footage is gone forever, is an AI approximation better than nothing, or worse than accepting that some art is irretrievably lost? Who owns the right to attempt these recreations—the studios that hold legal rights, the descendants of the original artists, or does anyone with sufficient technical capability have the moral authority?

These questions extend far beyond one Welles film. As generative AI becomes increasingly sophisticated, we'll face similar dilemmas with countless lost works of art, literature, music, and film. The Magnificent Ambersons project serves as a case study—imperfect but illuminating—for how we might approach these challenges.

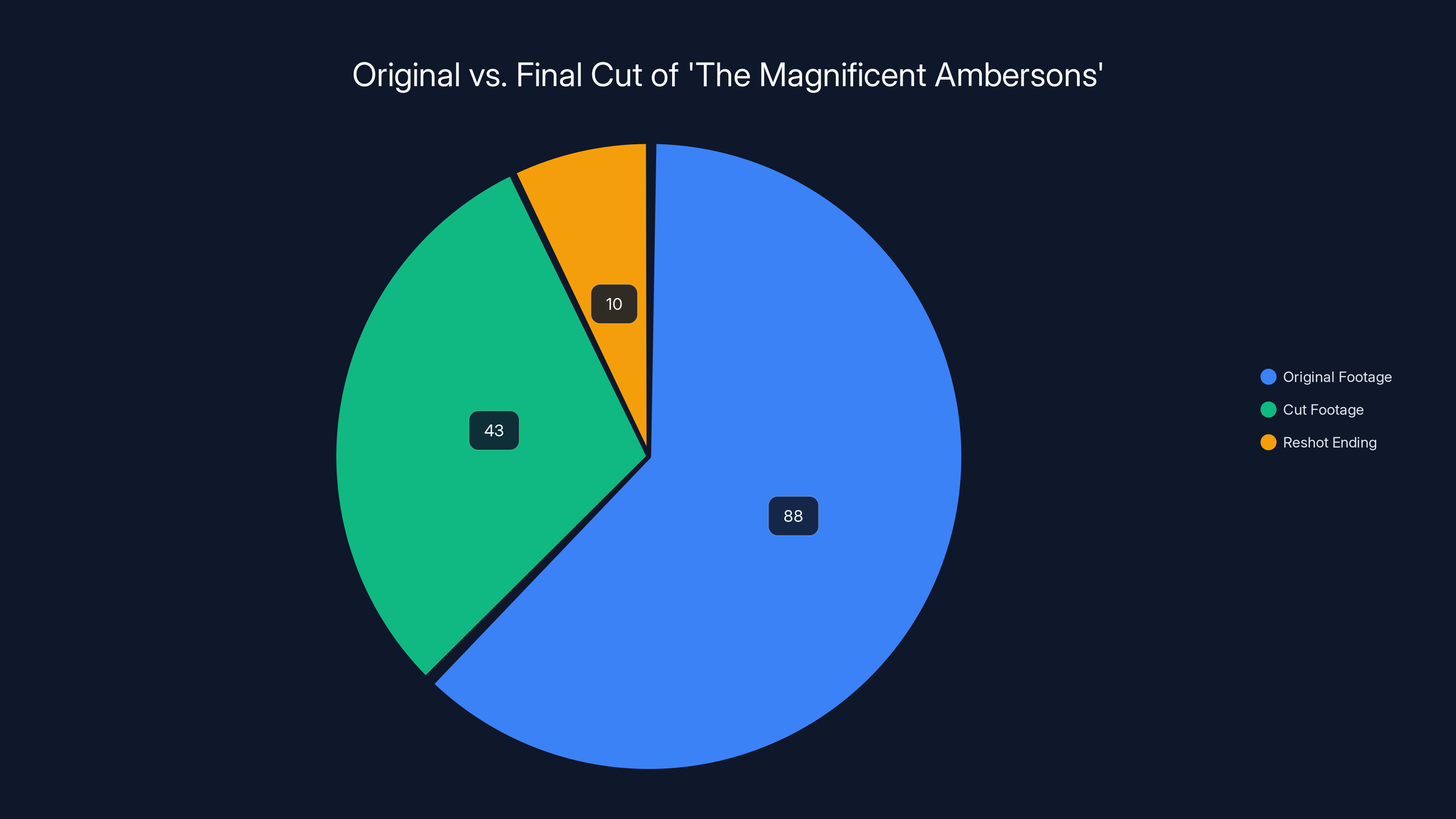

The original cut of 'The Magnificent Ambersons' was 131 minutes long, but 43 minutes were cut and replaced with a reshot ending, altering Welles' vision. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- The Core Issue: Orson Welles' "The Magnificent Ambersons" had 43 minutes of footage destroyed by the studio in 1942, and Fable is using AI to recreate the lost scenes using live-action filming and digital actor recreation.

- Why It's Complicated: While driven by genuine love for cinema history, the project raises profound questions about artistic authenticity, who owns the right to recreate lost work, and whether AI approximations constitute meaningful restoration.

- Current Status: Welles' daughter has moved from skeptical to cautiously optimistic, key film historians have endorsed advising the project, but significant technical and legal obstacles remain unresolved.

- The Deeper Problem: AI excels at statistical patterns but struggles with the irreplaceable human choices that define great art—cinematography, performance nuance, and directorial intent that can't be fully captured in algorithms.

- Bottom Line: The project isn't evil, but it's not a solution either. It's an ambitious fan work that highlights why some losses are permanent and why accepting impermanence might be more authentic than manufacturing replacement art.

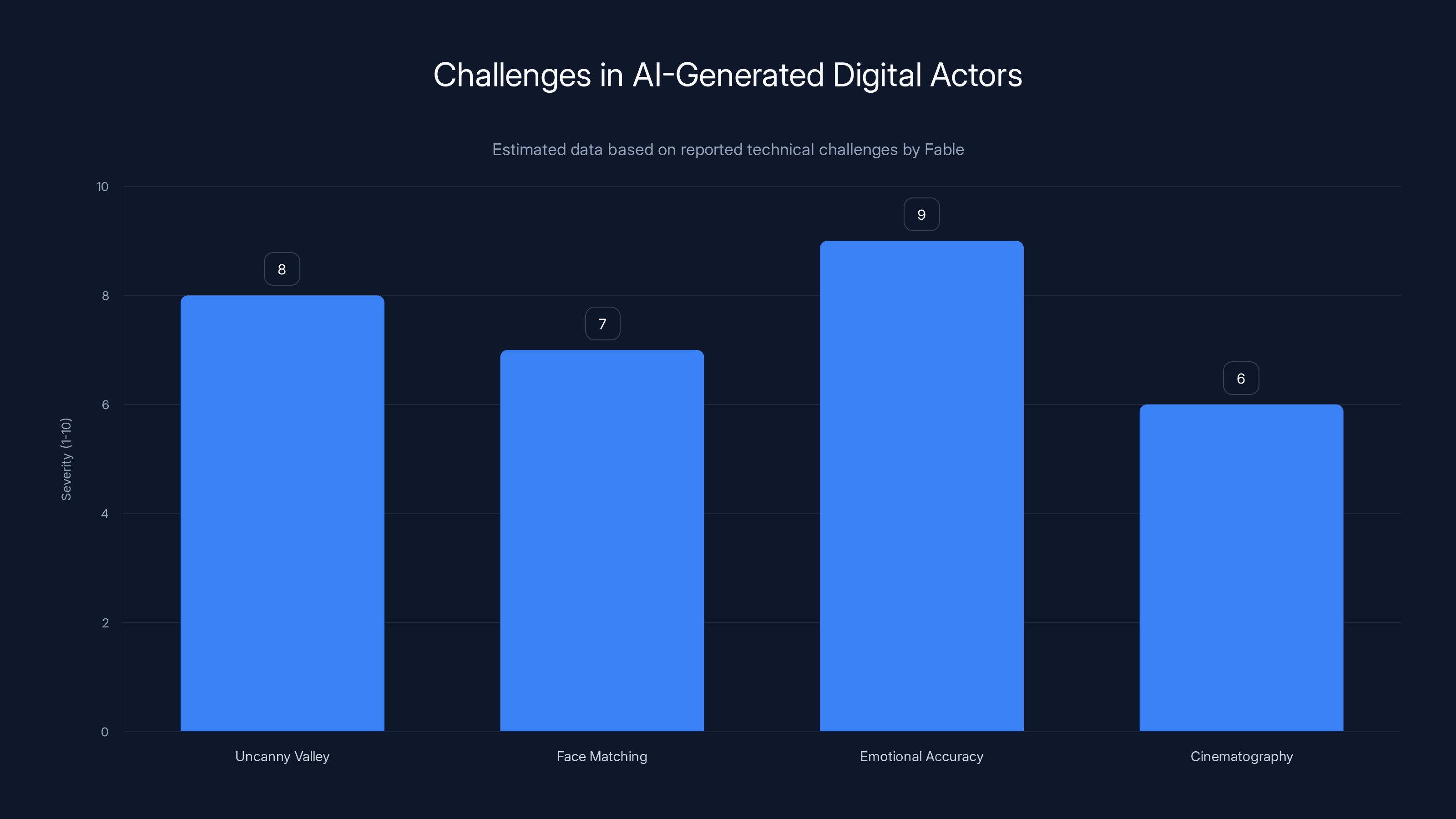

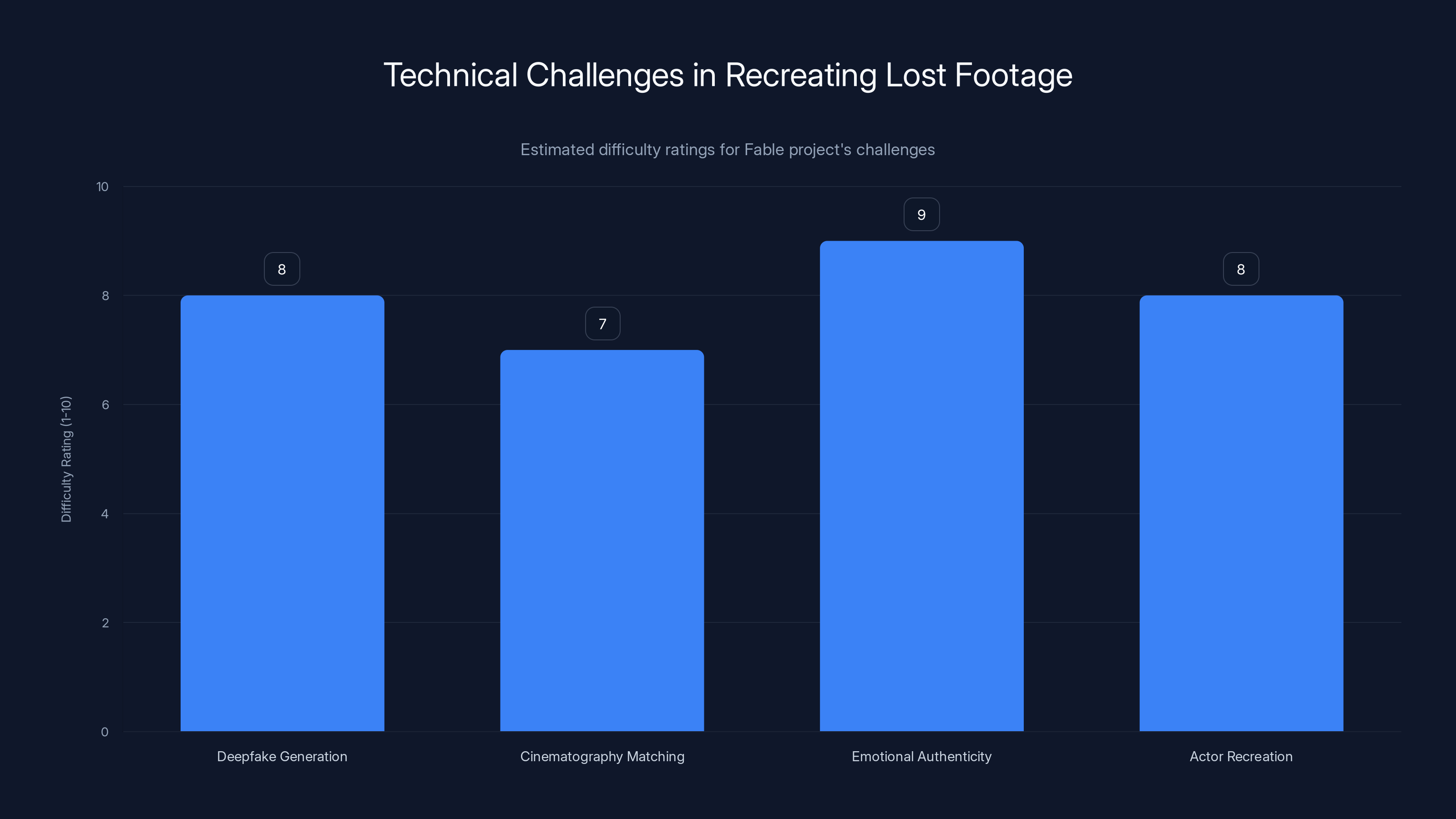

Estimated data suggests that emotional accuracy and uncanny valley effects are the most severe challenges in AI-generated digital actors, followed by face matching and cinematography issues.

Part One: The Tragedy of Lost Cinema

The History of "The Magnificent Ambersons"

To understand why this project matters at all, you need to know what was actually lost. "The Magnificent Ambersons" was Orson Welles' second feature film, released in 1942, less than four years after the stunning success of "Citizen Kane." Welles adapted it from Booth Tarkington's 1918 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and by all accounts—including Welles' own assessment—he created something extraordinary.

The film tells the story of the Amberson family, American industrial-age wealth embodied in one Midwestern dynasty watching its fortune and influence crumble as the 20th century industrializes past them. It's a critique of American capitalism, a family tragedy, and a meditation on time and loss. Welles shot it in a style as innovative as anything he'd done before, using deep focus cinematography, complex sound design, and narrative structure that influenced filmmakers for decades.

But here's where the tragedy begins. After previewing the film, RKO Pictures panicked. Test audiences didn't respond with the enthusiasm the studio expected. The original cut was roughly 131 minutes—substantial but not absurd by the standards of prestige drama. The studio decided the problem was the film's ending, which was downbeat and ambiguous, emphasizing loss and regret without redemptive catharsis. They pulled Welles out of the project (he was in South America filming another picture), and production executives began cutting.

Forty-three minutes hit the floor. About one-third of Welles' original vision vanished. The studio also reshot the ending, adding a contrivance of romance and reconciliation that Welles never intended. They destroyed the original footage rather than storing it, permanently erasing any possibility of restoration through conventional means.

The truncated version released in 1942 was still good—critics recognized its quality—but something essential was missing. Welles spent decades frustrated by this amputation of his work, and film scholars have been discussing the lost footage ever since. It became the holy grail of cinema restoration, a tantalizing phantom that exists in scripts, Welles' notes, still photographs, and the memories of people who saw the original cut.

This wasn't an accident or simple degradation. It was deliberate artistic sabotage by a studio executive more interested in immediate box office returns than artistic preservation. That context matters enormously when evaluating whether Fable's project makes sense.

Other Lost Films and Restoration Efforts

The Ambersons isn't alone. Early cinema is riddled with lost works. Of all silent films produced in the United States before 1926, only about 14% survive in complete form. For European silent films, the percentage is similarly grim. There are works by Sergei Eisenstein, F. W. Murnau, and countless other foundational figures that exist only in fragments or descriptions.

Film archivists have spent generations attempting restoration of the works that do survive. This usually involves painstaking physical work: finding deteriorated film stock, carefully cleaning and repairing it, color-correcting faded prints, and in some cases, reconstructing missing sequences by comparing multiple versions or using still photographs.

Some of these restorations have been extraordinary achievements. The 1952 restoration of "Vertigo" involved comparing dozens of international prints to reconstruct the correct colors. The restoration of "Metropolis" in 2008 added 25 minutes of previously missing footage discovered in Argentina, creating a much more complete version of Fritz Lang's masterpiece.

But all traditional restoration work operates within strict constraints: it can only restore what physically survives. You cannot recreate footage that's been destroyed unless you're willing to fundamentally reinvent the work, which brings us to the Fable project.

Part Two: How Fable's AI Approach Works

The Technical Foundation

Fable's approach differs fundamentally from traditional restoration because it's not restoring anything physical—it's generating entirely new footage based on Welles' artistic direction, the film's script, surviving photographs, and contemporary accounts of what was shot.

The process works like this: First, Fable's team scripts out the lost scenes using Welles' original script and notes about what was filmed. They then shoot these scenes with live actors in a controlled environment, recreating the cinematography and blocking as closely as possible to what descriptions and photographs suggest. This is where filmmaker Brian Rose comes in—he'd already spent years researching the exact blocking, lighting, and composition of the missing scenes, providing Fable with a detailed blueprint.

Once they have live-action footage, the AI component kicks in. Generative AI models trained on thousands of hours of period-appropriate cinematography, lighting techniques, and film stock characteristics are used to digitally grade and modify the footage, attempting to match the visual aesthetic of 1942 cinematography. Additionally, digital recreation of the original actors' appearances—using deepfake technology and voice recreation AI—allows the scenes to integrate seamlessly with the surviving footage.

This is radically different from traditional restoration. Traditional restoration reveals and enhances what's already there. This process manufactures entire sequences that never existed in digital form, using AI to fill the gap between historical documentation and speculative recreation.

The Challenge of Authenticity in Recreation

Here's where the technical complexity runs headlong into artistic philosophy. A photograph or script can tell you approximately what a scene should contain, but cinema isn't about content—it's about the infinite micro-choices that constitute directorial vision. How does the camera move? What's the exact duration of a pause? How does an actor's face shift during a moment of emotional recognition? These aren't technical specifications that live in documentation. They're the accumulated intuition of a filmmaker making thousands of micro-decisions during production.

Welles was obsessive about these details. His camera movements were precisely choreographed. His use of deep focus required specific lighting setups that themselves communicated meaning. His direction of actors was about extracting particular shades of emotion that mere dialogue doesn't convey. An AI model trained on historical cinematography can learn statistical patterns about how films look, but can it capture the specific genius of Welles' particular choices?

Conceptually, the answer is probably no. But practically, the question is whether an imperfect approximation is closer to Welles' vision than the destroyed footage is to any of our visions—which is simply inaccessible. You can't see the destroyed footage. It exists only as absence.

Fable has acknowledged the technical challenges transparently. The company has demonstrated AI errors including a two-headed actor (a failure in deepfake alignment), difficulty capturing the "natural" expression of female actors (the AI tends to generate inappropriate smiling), and the broader challenge of matching the subtle gradations of cinematography that made Welles' work distinctive.

These aren't minor technical glitches. They're indications that the AI is struggling with exactly the dimensions of filmmaking that matter most—human emotion, subtle performance, and nuanced visual communication.

The Hybrid Approach and Its Limitations

Fable's decision to use live-action filming as the foundation, then overlay digital recreation of the actors, is pragmatic but reveals the fundamental compromise at the project's core. By shooting live action, Fable bypasses the problem of generating movement and spatial relationships from nothing—actors and cameras moving through real space provide the skeleton the AI enhances.

But this creates a strange hybrid creature: partially real, partially synthesized, entirely neither. The live-action footage captures the spatial and physical elements, but the digital actor recreation imposes a layer of artificiality that undercuts the visceral authenticity of the photographed image.

Consider what this means for performance. Welles was famous for extracting remarkable work from actors—sometimes through encouragement, sometimes through intimidation, sometimes through technical tricks (like shooting through objects to create psychological distance). When you replace an actor's face digitally, you're divorcing the performance—the body language, the positioning in space—from the actor's actual facial expressions. The digital recreation has to approximate what that specific actor's face would show in that moment, but it's always working from a template, never from the actual human response to direction, to co-actors, to the emotional truth of the scene as it's being performed.

This hybrid approach technically resolves some problems while creating entirely new ones. It's neither pure recreation from script nor pure archival restoration. It's something else entirely: a speculative interpretation of how a lost work might have looked, using the surviving work as a reference.

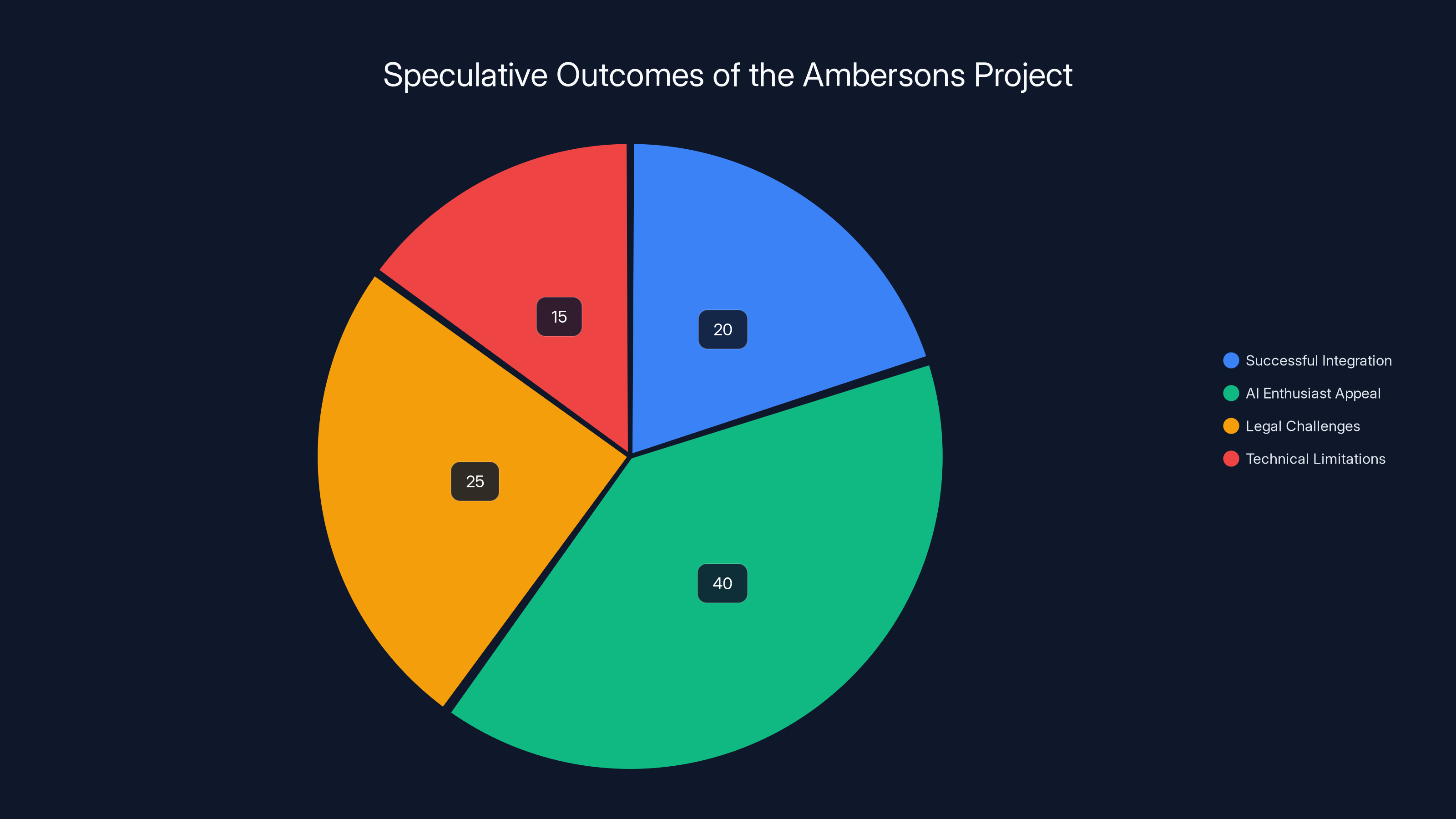

Estimated data suggests the most likely outcome is that the project appeals to AI enthusiasts and scholars, but faces challenges in becoming the definitive version of the film.

Part Three: The Philosophical Problem With AI Reconstruction

Why Loss Might Be Essential to Art

There's a philosophical argument that cuts deeper than technical feasibility, articulated compellingly by writer Aaron Bady in a recent essay comparing AI to the vampires in the film "Sinners." Bady's contention is that what makes art possible is precisely its confrontation with mortality and limitation.

Art emerges from the gap between what exists and what cannot exist. Welles' vision was constrained by the medium of 1942 cinema—what was technologically possible, what the human eye could perceive, what could be economically produced. Those constraints shaped his choices. An actor is constrained by being one person at one moment in time, unable to be multiple things simultaneously. A film frame is limited to what fits within its boundaries. Death and loss are fundamental to the human condition, and art that acknowledges and contends with these limits gains power from that confrontation.

When AI removes these constraints, something essential changes. An AI can generate infinite variations on a scene. It can create performances that are statistically optimal rather than authentically felt. It can erase the scars that time and accident inflict on art, but in doing so, it erases something about the artwork itself—the evidence of its creation by a human being working within real constraints.

Bady's argument has real force. There's something fundamentally different about a film that was shot by Orson Welles in 1942, with actual actors, using actual film stock, compared to a film that was shot by someone in 2025, with AI-enhanced digital recreation of long-dead actors overlaid on live footage. The latter is an interpretation. The former was the thing itself.

This doesn't mean the recreation is morally wrong or should be forbidden. But it does suggest that calling it "restoration" is conceptually misleading. You're not restoring the lost film. You're creating new art inspired by and approximating the lost film. That's substantially different.

The Trap of the Perfect Simulation

Here's a darker possibility: What if Fable creates something that's technically impressive enough that it convinces people they've seen the real thing? What if the AI-generated sequences integrate so seamlessly with the surviving film that viewers forget they're looking at speculation?

That's a form of deception, even if unintended. The moment you present AI-created footage without clear labeling and explanation, you've crossed into misrepresentation. You're showing people something and letting them believe it's something else.

Marketplaces of culture and film archives are built on trust and clarity about provenance. When you buy a print of a painting, you're trusting that the attribution is accurate, that you know who made it and when. When you watch a restored film, you trust that what you're seeing is the closest possible approximation to what the original artist intended, given the constraints of what survives.

Adding AI-generated footage violates that trust fundamentally. Even if the AI work is done with the best intentions and the highest aesthetic standards, the product is no longer the artist's work. It's the artists' plus the Fable team plus AI algorithms. That's a collective creation, and presenting it as "restored Welles" is misleading.

Some film archives and preservation organizations have begun developing guidelines for AI-assisted restoration, precisely because this issue looms so large. The challenge is distinguishing between AI tools that enhance and clarify existing footage (useful and appropriate) versus AI tools that fabricate entire sequences (problematic and misleading).

Competing Claims on Artistic Legacy

The ethical complications deepen when you consider whose vision matters. Orson Welles is dead. He never got to defend this project, articulate his concerns, or approve the methodology. The studio executives who destroyed the footage are also dead. So who speaks for the work now?

Fable's Edward Saatchi argues that his genuine love for the film and deep research into Welles' artistic approach qualifies him to make these decisions. Welles' daughter Beatrice, initially skeptical, now believes Fable is approaching the project with appropriate respect and love. Film historian Simon Callow, who is writing an authorized multi-volume Welles biography, has agreed to advise the project.

But actress Anne Baxter's daughter, Melissa Galt, represents another perspective: "It's not the truth. It's a creation of someone else's truth. But it's not the original, and she was a purist." Baxter performed in the missing sequences. Her body, her voice, her performance talent created something real in 1942. Creating a digital simulation of her face and voice without her consent or her family's enthusiasm feels like a violation of her creative contribution.

There's a genuine conflict here between the impulse to honor Welles' vision and the reality that this project involves dozens of people whose work is being digitally reconstructed, whose likenesses are being recreated, and whose families may or may not approve.

Part Four: The Rights and Permissions Maze

Who Actually Owns Lost Films?

Saatchi made one critical strategic error: he announced the project without first securing permissions from the entities that actually control the film legally. Warner Bros. owns the rights to "The Magnificent Ambersons" (acquired through their ownership of RKO's library). Orson Welles' daughter controls aspects of Welles' legacy. The actors' families, the estate of the cinematographer, various other stakeholders all have potential claims or interests.

Film rights are notoriously complicated. A rights holder has the legal ability to control how a film is distributed, modified, and presented. But rights holders don't necessarily have aesthetic claim to the work. They own the commercial and legal apparatus around it, but that doesn't make them custodians of the art in any deep sense.

Warner Bros.' interest in the Ambersons is primarily financial. They earn money when the film is licensed or distributed. They may or may not care about preserving Welles' artistic vision—they care about asset value. Trying to get corporate approval for an experimental recreation project is frustrating precisely because corporate entities think in terms of legal liability and revenue, not artistic integrity.

Permissions From the Living

Welles' daughter has apparently moved from skepticism to conditional support, believing that Fable is approaching the material with genuine respect. But her approval, while meaningful, doesn't eliminate all ethical concerns. There are other family members, other stakeholders, other people with claims on Welles' legacy.

The actors' families present another layer of complexity. If the project proceeds, Fable will be creating digital reconstructions of deceased actors—Joseph Cotten, Tim Holt, Anne Baxter, and others—without their consent (since they're deceased) and in some cases over the objections of their families. There's an argument that synthesizing someone's face and voice, even posthumously, is a form of using their identity without permission.

Elaborately, you could argue that posthumous digital creation of someone's likeness is different from using archival footage of them. The archival footage is the actual person captured at that moment. The digital recreation is a simulation, something the person never actually did and never consented to. That's a meaningful distinction, and it's ethically complicated.

The Studio's Responsibility

There's also a question about whether Warner Bros. has an obligation to support restoration efforts or a responsibility to the artwork itself. The studio that destroyed the footage is long gone, but the current rights holder inherited both the asset and the ethical consequences of that destruction.

One argument: Warner Bros. should enthusiastically support any reasonable effort to reconstruct what their predecessor studios destroyed. The current corporation shouldn't be liable for 1930s decisions, but it also shouldn't benefit from them while refusing to help remedy them.

Another argument: Warner Bros.' job is to maintain and distribute the work as it exists. Collaborating with experimental AI projects introduces liability and risk. If the Fable project is sued by someone claiming improper use of a deceased actor's likeness, does Warner Bros. get dragged into that lawsuit? If the AI-generated footage is ultimately not approved for release, has the company invested time and credibility in a failed project?

From a purely corporate perspective, Warner Bros. has incentives to be cautious. From an artistic or historical perspective, they have incentives to be more generous. Those incentives conflict, and the company has to navigate between them.

The Fable project faces significant technical challenges, with emotional authenticity and actor recreation rated as the most difficult tasks. (Estimated data)

Part Five: Technical Challenges and Failures

The Uncanny Valley of Digital Actors

One of the most persistent problems Fable has reported is what you might call the "uncanny valley" of AI-generated human faces and bodies. The uncanny valley is that eerie, unsettling feeling you get when something almost looks human but not quite—close enough that your brain notices the failures. Deep learning models trained on millions of human faces can generate faces that are statistically realistic, but they often miss subtle cues that human perception evolved to detect: the specific way eyes focus, the micro-movements of facial muscles, the individual character of someone's particular nose or ears.

This is compounded by the fact that Fable isn't just generating faces—it's generating faces that need to match specific actors in specific emotional contexts while integrating with live-action footage shot in 2025. The uncanny valley becomes a canyon. The digital face has to occupy the same space and respond to the same co-actors as the live actors around it, and any discontinuity becomes immediately apparent.

Fable acknowledged specific failures: a two-headed version of actor Joseph Cotten (presumably a blending error where the deepfake algorithm doubled some portion of the face), actresses generated with inappropriately cheerful expressions (the AI interpreting ambiguous emotional situations as inherently positive). These aren't minor technical glitches. They're evidence that the AI is failing at exactly the dimensions that matter most in performance—authenticity of emotion and the subtle authenticity of how humans actually look and move.

Cinematography and Visual Continuity

Another substantial challenge is matching cinematography. 1942 Technicolor has specific characteristics: a particular color palette, specific limitations on shadows and contrast ranges, film grain patterns, and the particular look of studio lighting from that era. Contemporary digital cinematography looks fundamentally different. Matching that aesthetic isn't just about applying a filter. It requires understanding the technical choices that produced 1942 cinematography and recreating them with modern equipment.

This is where Fable's live-action approach theoretically helps—they can attempt to light and shoot contemporary scenes in ways that approximate 1942 techniques. But the integration point is the moment where AI color grading and effects are applied to match the surviving footage. Small discontinuities in lighting, color temperature, or grain will become immediately visible and break immersion.

Film scholars who've seen preliminary clips describe the results as interesting but noticeably artificial. The live-action elements have a contemporary quality despite efforts to match 1942 cinematography. The AI enhancement adds a layer of digital processing that reads as obviously computer-generated to trained eyes. Whether general audiences would notice these issues is unclear, but cinephiles certainly would.

The Impossible Problem of Performance Direction

Perhaps the deepest technical challenge is one that can't fully be solved: directing a performance through an AI model. Orson Welles was renowned for his ability to extract specific emotional performances from actors. He had methods: sometimes encouraging actors to dig into emotional truth, sometimes using technical tricks (blocking them in specific ways, framing them with particular objects) to achieve the psychological effect he wanted.

When you're directing a live actor, even one walking through a scene shot in 2025, you can see their actual performance and adjust it. When you're adjusting a digital recreation of an actor's face, you're not adjusting a performance—you're adjusting a digital model. The divergence from authentic performance increases.

There's a philosophical point here: a performance is not just a face and voice. It's a human being making choices in real time, responding to direction, to co-actors, to the moment. You cannot fully capture that in algorithms, because the thing itself involves human consciousness and choice-making.

Part Six: The Honest Assessment of What This Actually Is

A Novelty, Not a Solution

After considering all the technical and philosophical arguments, here's what I keep returning to: at its absolute best, this project will create an interesting novelty. It will be a skilled fan work that approximates Welles' vision based on historical documentation and educated speculation. It might be beautiful. It might illuminate aspects of Welles' artistic approach. It might be something worth seeing.

But it won't be the lost film. It will be a 21st-century interpretation of what the lost film might have looked like, created with 21st-century tools by people who never worked with Welles and never had to make the real artistic choices that would have confronted him during production.

That's not a condemnation. Interpretations and reimaginings have value. They're how artists build on one another's work. But presenting them as restoration or as access to the original artist's vision is misleading. It's important to be honest about what it is.

Fable seems increasingly honest about this distinction. They're not claiming they've recovered Welles' lost footage. They're claiming they've attempted to visualize what it might have contained, informed by extensive research and deep affection for the source material. That's a more defensible position.

Why Some Losses Might Be Worth Preserving

Here's the heretical thought: maybe "The Magnificent Ambersons" is supposed to be incomplete. Maybe the destruction of those 43 minutes is part of the film's actual history and meaning, not a tragedy to be remedied.

The film we have is compromised, cut down, ending with a happy ending that Welles never intended. That's a real wound, a visible amputation. But that wound is also the film's actual history. It's evidence of studio interference, of artistic compromise, of the material pressures that shape art. The surviving film documents all of that.

Adding AI-generated scenes that approximate the lost material would actually erase some of that historical reality. You'd no longer see the scars where the studio cut. You'd have a version that feels more complete but is actually more false, because it pretends the damage never happened.

There's an argument that some art is supposed to bear the marks of its creation and destruction. The Parthenon is more powerful because it's a ruin. Weathering and loss are part of what it communicates. A perfect digital reconstruction of the Parthenon in its original form would be interesting, but it would lose something essential about what the actual ruin conveys.

The Dangerous Precedent

If Fable successfully recreates Welles' lost film, what's the next project? There are thousands of lost films, lost paintings, lost literary works. Do we start commissioning AI to recreate them all? Do studios start funding projects to complete works that artists never finished, using AI to fill the gaps in authorial intent based on available scripts and notes?

That road leads somewhere uncomfortable. It leads to a world where we're increasingly replacing human-made art with statistically plausible approximations, where loss is erased but authenticity is eroded, where the originary act of artistic creation becomes less important than the ability to simulate it.

AI companies have strong financial incentives to push this direction. Each successful reconstruction is a proof-of-concept that generates demand for more. Each project that integrates seamlessly with existing work makes the next project easier technically and culturally. Before long, you've established a norm where AI recreation of lost art is expected, and the absence of such projects seems like a failure of technological ambition.

But cultural precedents matter. If we establish that AI should attempt to complete unfinished work and recreate destroyed work, we're making a fundamental decision about what we value: the ability to have more art, or the authenticity and originality of the art we actually have.

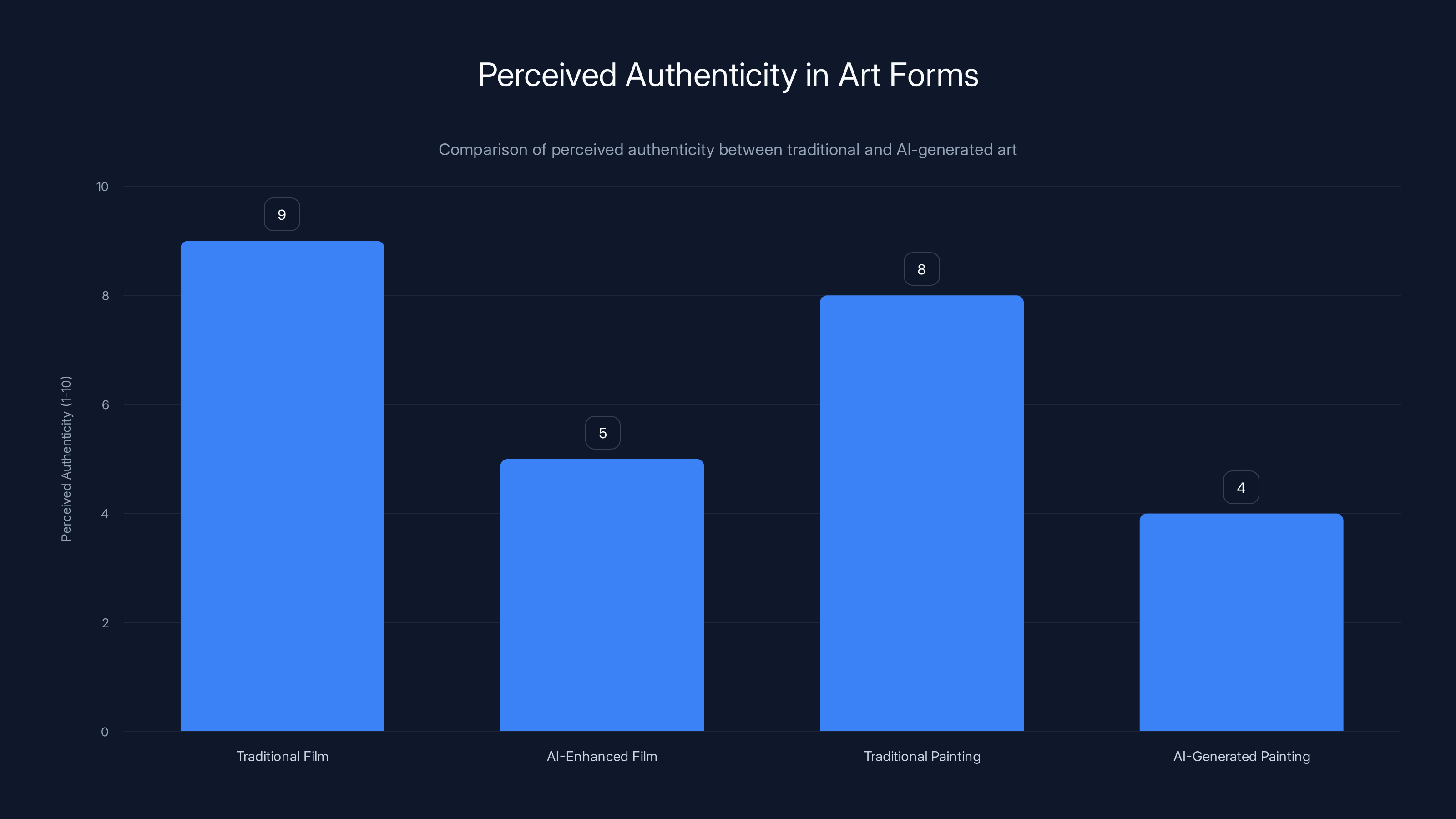

Traditional art forms are perceived as more authentic compared to AI-generated counterparts, highlighting the philosophical debate on authenticity and constraints in art. Estimated data.

Part Seven: What Other Filmmakers and Historians Actually Think

Support From the Film Community

Simon Callow, who is writing an authorized multi-volume biography of Orson Welles and is personally close to the Saatchi family, has agreed to advise the Fable project and described it as a "great idea." That's significant endorsement from someone with genuine expertise in Welles' work and access to the filmmaker's papers and legacy.

Callow's support suggests that the project isn't viewed as purely hubristic or ignorant by serious Welles scholars. Someone who has spent years studying Welles' work in granular detail believes this is worth doing, which carries weight.

But Callow is also friends with Saatchi's family, which introduces bias. He has personal relationship investment in the project's success. That doesn't mean his opinion is wrong, but it's important context for evaluating it.

Skepticism From the Creative Community

Not everyone is convinced. Melissa Galt, whose mother actress Anne Baxter performed in some of the missing sequences, expressed clear opposition: "It's not the truth. It's a creation of someone else's truth. But it's not the original, and she was a purist." That's a perspective from someone whose family member's creative contribution would be digitally reconstructed without the original artist's consent.

There's a distinction between scholarly support (Callow) and creative community support that's worth noting. Callow's interest is in the historical and artistic significance of potentially accessing Welles' vision. Galt's interest is in honoring the actual actors whose work would be simulated. Those are both legitimate concerns, and they don't necessarily align.

The Archive Perspective

Film archivists and preservation specialists have been notably cautious about this project. They understand restoration in the traditional sense—stabilizing deteriorating material, removing scratches and damage, color-correcting faded footage. Creating entirely new scenes is outside the established practice of archival preservation.

Many archivists worry that AI-assisted recreation sets a precedent that muddles the distinction between restoration and interpretation. If archives begin working with AI to fill gaps in damaged materials, where does that end? Every restoration decision involves judgment calls and interpretation, but there's a meaningful difference between revealing the original material more clearly and fabricating new material.

The archival community is developing guidelines, but there's not yet consensus on where the line should be drawn or how to label AI-assisted work appropriately for future generations.

Part Eight: The Legal Minefield

Intellectual Property Rights and Likenesses

Fable's plan to digitally recreate deceased actors raises unresolved legal questions. In most jurisdictions, once an actor is deceased, their right of publicity passes to their estate or heirs. Using someone's likeness without permission from that estate may constitute violation of their publicity rights, even if they're dead.

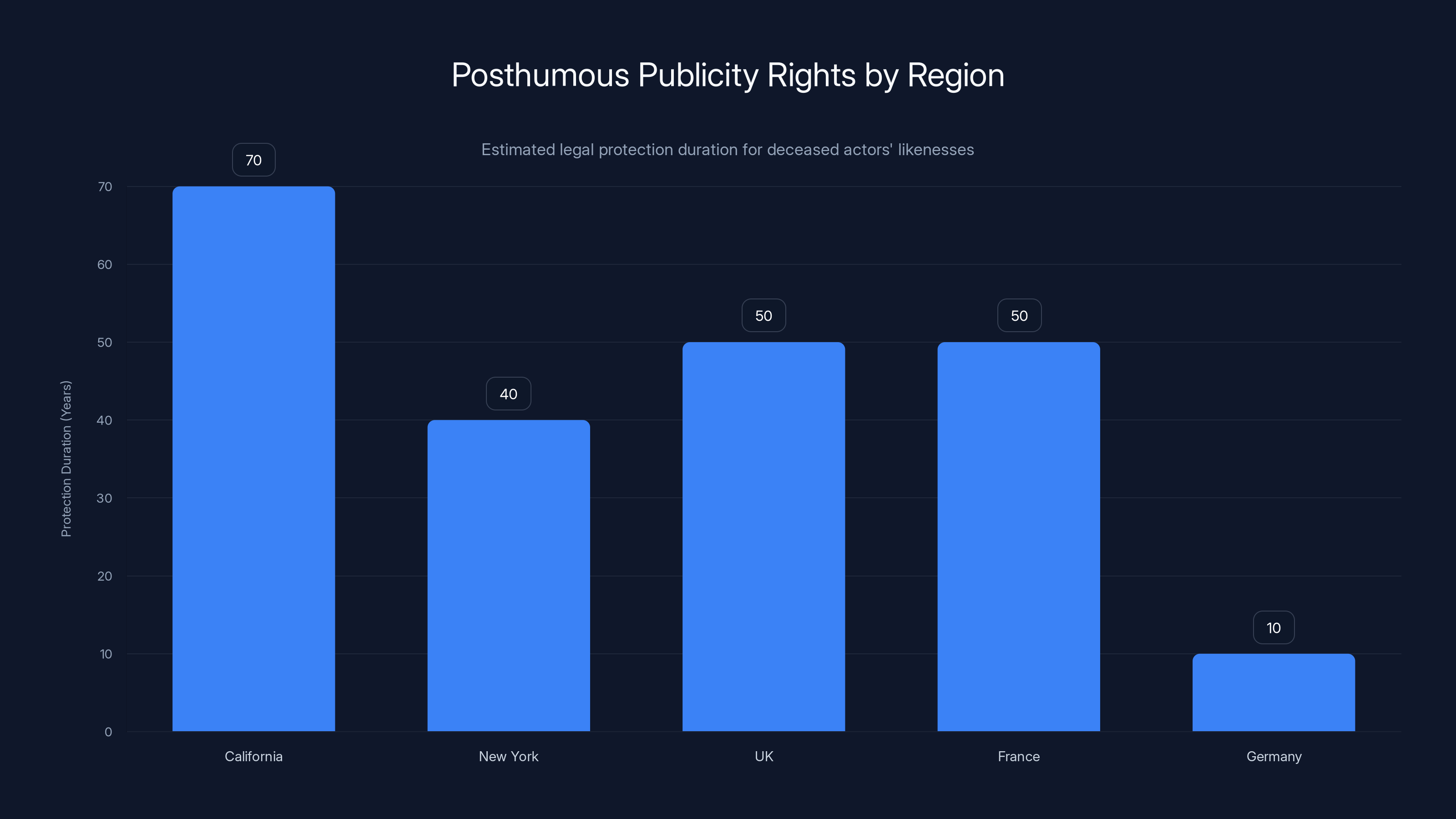

Some states and countries have extended publicity rights to cover posthumous uses. Others haven't. The law is inconsistent and evolving. California, for instance, has strong protections for the right of publicity, both during life and for 70 years after death. But those protections don't necessarily apply to digital recreations—they historically covered things like photographs and film footage, not algorithmic recreations.

Fable is likely going to need to negotiate with the families of the deceased actors or get legal opinions on whether they can proceed without explicit permission. This is costly and time-consuming, and there's no guarantee the families will agree.

Warner Bros.' Liability Exposure

Warner Bros. has to consider whether supporting this project exposes them to legal liability. If someone claims that Fable's recreation of a deceased actor's likeness violates that person's publicity rights, does Warner Bros. get sued as the rights holder to the underlying film? If the project is legally challenged, does the company's association with it create problems?

From a risk management perspective, Warner Bros. has incentives to stay at arm's length from the project until the legal landscape is clearer. From a film preservation perspective, they should probably support it. Those incentives conflict, and corporate entities tend to prioritize legal risk over cultural contributions when forced to choose.

Contractual and Licensing Issues

Fable is using Brian Rose's years of research into how the lost scenes were originally composed. That research might be protected intellectual property. Fable is collaborating with Simon Callow, a prominent scholar and Welles biographer. The arrangement between those parties has to be legally structured in ways that protect everyone's interests.

There are also questions about music rights, if the restored film will include new recordings of period-appropriate scores. There may be rights issues with any techniques or software that Fable uses in the recreation. The more successful and sophisticated the project becomes, the more complex the legal surface area becomes.

Estimated data showing varying posthumous publicity rights protection across regions, with California offering the longest duration of 70 years.

Part Nine: The Broader Pattern of AI and Artistic Recreation

Why Studios Love This Direction

There are strong financial incentives for studios to pursue AI-based recreation and completion of lost or incomplete works. A studio can rerelease a "completed" version of an unfinished film, generate new content from a beloved franchise, or add missing pieces to fragmented works. All of that has commercial value.

The economics are compelling: hire a team, pay for computing resources, and generate new "content" that can be marketed as restoration or completion. The costs are modest compared to traditional production. The potential returns are significant if the project succeeds and captures audience interest.

Studios are businesses. They're naturally going to explore avenues that expand their asset base and create revenue opportunities. If Fable succeeds, expect similar projects to be greenlit by every major studio.

The Risk of Homogenization

Here's a darker possibility: what if AI recreation becomes good enough that it's economically efficient to "complete" old films? What if instead of keeping films as they actually exist—damaged, incomplete, bearing the marks of history—we start systematically replacing them with polished, complete versions that never actually existed?

You'd end up with a cultural archive that's technically complete but aesthetically false. Every work would be optimized, finished, without the rough edges that give art its texture and authenticity. We'd have exchanged historical fidelity for commercial polish.

That's the scenario that film archivists and preservation specialists worry about. It's not an immediate risk, but it's a plausible endpoint if the trend continues.

Part Ten: A Speculative Future for AI and Lost Cinema

Possible Outcomes of the Ambersons Project

Several scenarios are plausible. In the best case, Fable produces something genuinely impressive—footage that integrates seamlessly with the surviving film, that many viewers find artistically compelling, and that deepens our understanding of Welles' artistic approach. The project gets released, is well-received, and establishes a model for how to approach similar projects in the future. Welles' vision, compromised as it has been for 80 years, finally gets closer to expression.

In a more likely scenario, Fable produces work that's impressive to AI enthusiasts and interesting to Welles scholars, but that film historians and cinephiles recognize as artificial. It gets released with extensive documentation explaining its origins and methods. It's useful as a historical artifact and a proof-of-concept, but it doesn't become the definitive version of the film. The original, incomplete Welles version remains the canonical version.

In a worse scenario, the project faces insurmountable legal obstacles. The actors' families object to digital recreation of their relatives. Warner Bros. decides the liability exposure isn't worth the potential benefit. The project stalls or is abandoned. Fable burns through funding trying to navigate legal and cultural resistance.

There's also a version where the technical challenges prove insurmountable despite the team's best efforts. The AI simply can't generate convincing performances or cinematography, no matter how much they iterate. The team realizes they're approaching a hard limit of what the technology can do, and the project becomes abandoned as technically unfeasible.

How This Changes If It Succeeds

If Fable's project succeeds and is well-received, it will almost certainly generate demand for similar projects. There are dozens of other lost films that directors, studios, or archives might want to recreate. There are unfinished literary works that AI could theoretically complete based on authors' notes. There are paintings with missing sections, sculptures with missing limbs, music with lost movements.

Each successful project makes the next one easier and more likely. The technology improves. The cultural acceptance grows. The distinction between restoration and creation gets harder to maintain.

Within a decade, we might live in a world where major studio releases include AI-completed sequences as a matter of course. Where fans expect missing footage to be filled in. Where the idea of accepting incompleteness or loss seems quaint and technologically lazy.

That doesn't mean it's bad—it just means the cultural practice around art and archival would have shifted fundamentally. We would have decided, as a society, that technological completeness matters more than historical authenticity.

The Unlikely Scenario: Restraint

There's a possibility that the film community collectively decides that AI recreation of lost art crosses a line that shouldn't be crossed. That despite the technical feasibility and the cultural appeal of seeing lost works restored, the authenticity costs are too high. That archives and studios commit to displaying art as it actually survives, with documentation about what's missing, rather than filling gaps with simulations.

This scenario seems unlikely given economic incentives and the difficulty of establishing and enforcing cultural consensus. But it's possible. It would require film scholars, archivists, ethics committees, and studios all agreeing that certain losses should be preserved rather than remedied.

Cultural practices can shift. There was a time when altering historical photographs was considered acceptable, even normal. Most of that practice has been abandoned in favor of showing historical images as they actually are. A similar consensus could theoretically emerge around AI and lost art.

Part Eleven: The Deeper Question About Art and Loss

What Incompleteness Teaches Us

Incomplete art carries a unique kind of power. A sculpture missing an arm speaks about fragility and the passage of time. An unfinished novel left by a deceased author documents the author's artistic consciousness at a specific moment, frozen before the work could be resolved. A film cut down by a studio preserves the history of artistic compromise and institutional power.

When you fill in the gaps, you remove that evidence. You create something more complete aesthetically but less complete historically. You gain beauty and lose truth.

There's something important about accepting that some art will be damaged or destroyed. It's part of how we understand the world. Things break. Time erodes. Human institutions make terrible decisions. Art that survives with those wounds intact is more honest about the world than art where all the damage has been digitally repaired.

The Temptation of Total Knowledge

The AI recreation impulse comes partly from a utopian fantasy: that we can know everything, recover everything, make nothing permanently inaccessible. If we can simulate Welles' lost footage accurately enough, we can know what he intended. We can access his complete vision.

But that's an illusion. The simulation is not Welles' vision. It's the Fable team's interpretation of what Welles might have intended, filtered through algorithms and constrained by the capabilities of contemporary technology. It's plausible speculation, not knowledge.

There's a kind of intellectual humility in accepting that some things are genuinely lost. That we can't fully recover Welles' artistic choices because he's dead and we didn't work with him. That our access to his work is necessarily incomplete and mediated by circumstance.

Cultural confidence—the belief that we can and should recover everything—is seductive. But it might be less philosophically honest than accepting limitation.

Why Welles Himself Might Object

Here's a speculation: would Orson Welles actually want his lost footage recreated by AI teams in 2025? Welles was intensely particular about his work. He believed in maintaining directorial control and was willing to fight institutions to preserve his artistic vision.

Recreating his work without him seems like exactly the kind of thing he would object to—not because he was opposed to technology, but because it represents a loss of control over his creation. He didn't get to direct the actors. He didn't get to make the creative decisions that would have shaped the footage. Someone else is making those decisions on his behalf.

That's speculation, of course. We can't ask him. But it's worth considering whether honoring an artist means respecting their absence and accepting that some of their work is forever beyond our reach, or whether honoring them means trying to access and complete their vision even posthumously.

Part Twelve: How Audiences Will Actually Engage With This

General Viewers vs. Sophisticated Viewers

If Fable's project is released, how will different audiences respond? A general viewer watching the restored film might not notice or care that some sequences were AI-generated. To them, it's just the complete version of "The Magnificent Ambersons," integrated and enjoyable.

A cinephile or film historian watching the same footage would likely notice the artificial quality immediately. The grain pattern wouldn't quite match. The acting performances would feel slightly off. The cinematography would have that subtle digital quality that reads as obviously not 1942 film stock.

This creates an awkward asymmetry: casual audiences might actually prefer the polished, completed version, while the people who care most about film and cinema history would recognize it as inauthentic. The general public gets happy, and the experts get frustrated.

That tension might actually be unresolvable. You can't make something that's both technically impressive enough to fool casual viewers and aesthetically authentic enough to satisfy experts, because those are somewhat contradictory goals.

The Permanent Question Mark

Assuming the project goes forward and releases footage, there will always be uncertainty about what we're actually seeing. Was this scene shot by Welles? Was it recreated by Fable? How much does it actually approximate Welles' intention versus the team's interpretation?

That uncertainty isn't a bug—it's actually crucial information. But it creates interpretive burden on viewers. Every scene carries implicit footnotes and asterisks. Your experience of the film is mediated by this knowledge of inauthenticity.

Fable could resolve this through transparent labeling: clearly marking which sequences are AI-generated and documenting the methodology. That's the ethically correct approach. But it also means the viewing experience is interrupted by metadata and explanation, which undermines the seamless integration they're trying to achieve.

Part Thirteen: Practical Implications for Film Preservation

What This Means for Archives

If AI recreation becomes viable and accepted, film archives will have to develop new policies about how to handle incomplete materials. Do they start commissioning AI recreations of visibly damaged sequences? Do they create parallel versions—the authentic incomplete version and an AI-completed version?

These decisions will shape how future generations experience cinema history. Archives have responsibility to be stewards of how art is presented and preserved. If they start accepting AI recreation as a standard preservation technique, they're making a fundamental choice about authenticity and historical accuracy.

Most serious archivists are cautious about this direction. They worry about precedent and the erosion of standards. But there will be pressure from studios, from audiences, and from technology companies to embrace AI as a preservation tool.

Training the Next Generation of Preservationists

Film students learning archival work today are growing up with AI as an available tool. The next generation of archivists will have different intuitions and assumptions than current archivists do about what's acceptable in preservation practice.

If AI-assisted recreation becomes normalized during their training, they'll approach damaged materials differently than archivists who trained in a pre-AI era. They'll see incomplete works as problems to solve with available technology, not as artifacts to preserve as-is.

That's a generational shift with long-term implications. The standards established in the next five years will probably govern archival practice for the next 50 years.

Part Fourteen: The Ethical Framework We Need

What Should Guide These Decisions?

If institutions are going to engage with AI recreation of lost art, they need ethical frameworks to guide the decisions. Here are some principles worth considering.

First, transparency: any AI-created footage must be clearly labeled as such, with documentation of the methodology, the sources used, and the assumptions made. People engaging with the work should know what they're seeing.

Second, consent from stakeholders: the families of artists involved, the estates of deceased individuals whose likenesses are being recreated, and the institutional rights holders should have meaningful input into whether projects proceed.

Third, historical preservation: the original incomplete/damaged version should be preserved and presented alongside any AI recreation. Future generations should be able to see both the authentic original and the speculative reconstruction, to make their own judgments about value and authenticity.

Fourth, humility about limits: clearly acknowledging that AI recreation is interpretation, not recovery. It's the best guess based on available evidence, not the actual artist's work.

Fifth, respecting incompleteness: recognizing that not all lost work should be recreated, that accepting permanent loss is sometimes more appropriate than speculating completion, that some wounds are part of art's history.

These principles don't require rejecting AI recreation entirely. They just require doing it with care, honesty, and respect for the complexity of what's at stake.

Part Fifteen: Moving Forward With Nuance

Why This Project Isn't Straightforward Evil

I started by being skeptical and somewhat angry about the Fable project. After learning more about it, my anger hasn't entirely dissipated, but it's been complicated by understanding the genuine love and respect driving it. Edward Saatchi isn't approaching this cynically. He's not trying to make money off exploiting Welles' legacy. He seems genuinely motivated by a desire to see a great artist's vision more fully realized.

That doesn't resolve all the ethical problems. But it matters. Good intentions don't make a problematic project unproblematic, but they do change how we should engage with it. This isn't venture capital exploitation of culture. It's fan work with resources, which comes with its own set of complications but isn't inherently wrong.

Some of the people advising the project—Simon Callow, Brian Rose, Welles' own daughter—are people who care deeply about cinema and about preserving Welles' legacy appropriately. That doesn't guarantee the project will succeed or that it's the right call, but it suggests it's not being approached recklessly.

Why the Concerns Still Matter

But the concerns about authenticity, about precedent, about the potential homogenization of cultural archives, those concerns remain valid. Even well-intentioned projects can establish patterns with long-term consequences. Even admirable goals can create problems if not pursued carefully.

The question isn't whether the Fable team cares about the work. It's whether the existence of this project, if successful, makes it more likely that other projects will treat AI recreation as a standard tool. Whether it establishes expectations that lost art should be recovered, rather than accepted as permanently lost. Whether it begins the slow erosion of the distinction between restoration and interpretation.

Those are legitimate concerns even if you respect the specific intentions behind this particular project.

A Path Forward

Ideally, what happens next is: Fable continues developing the project with full transparency about methodology and challenges. They engage seriously with all stakeholders—the studio, the families, film historians, and archivists. If they eventually release something, it's presented with clear documentation of what's AI-generated, what's speculative, and what's based on historical evidence.

Simultaneously, the broader film and cultural preservation communities develop thoughtful guidelines about AI and lost art. Not prohibition—these tools can be genuinely useful—but standards that prioritize honesty and historical authenticity over polish and completion.

When this project is inevitably discussed in film schools and preservation programs, it's discussed with full complexity: here are the interesting things the team accomplished, here are the authentic problems with AI-generating creative work, here are the questions we should still be asking.

And perhaps most importantly, the surviving incomplete version of "The Magnificent Ambersons"—the version actually directed by Orson Welles, damaged and compromised as it is—continues to be treated as the primary canonical text, with the AI-reconstructed version existing as supplementary material for those interested in historical speculation.

Conclusion: Living With Imperfection

The Magnificent Ambersons project sits at an intersection of genuine technical achievement, legitimate artistic passion, and difficult philosophical questions about what we should do when we have the power to fill in lost art. There's no clean answer that resolves all the tensions.

What I've become convinced of, through researching this topic deeply, is that our impulse to complete and restore lost work comes from good instincts but needs to be balanced against equally important instincts: to respect historical authenticity, to accept that some losses are permanent, to preserve the evidence of how art is shaped by circumstance and limitation.

Orson Welles' actual voice has been lost. His actual directorial choices for the missing scenes can't be recovered. What we can recover is the incomplete film he left behind—scarred and compromised, but genuinely his. That's worth preserving in its authentic form, even alongside speculation about what he might have done with those missing 43 minutes.

The Fable team seems genuinely motivated by love of cinema and respect for Welles. I hope they continue. I hope they're transparent about what they're creating. I hope they don't oversell it as restoration. And I hope the broader cultural conversation about AI and lost art takes seriously the questions of authenticity, precedent, and what we're willing to sacrifice in pursuit of completeness.

Some art is supposed to be incomplete. Some artists are supposed to have work that exists only as fragments. That's not a tragedy we need to fix—it's part of how we understand that art is made by humans working within limitations, and those limitations are part of what gives art its power.

Wells might not have cared about any of this. He might have loved the idea of his vision being completed, or he might have objected vehemently. We'll never know. That uncertainty—that permanent gap between what was lost and what remains—might be the most important thing to preserve.

FAQ

What is the Fable project attempting to do with AI and "The Magnificent Ambersons"?

The Fable project aims to use generative AI combined with live-action filming to recreate approximately 43 minutes of footage that was destroyed from Orson Welles' "The Magnificent Ambersons" in 1942. The studio originally cut this footage and destroyed it to make vault space. Fable's approach involves shooting live-action scenes based on the original script and historical documentation, then using AI to digitally recreate the original actors' appearances and match the cinematography of the era. The project operates under the creative direction of filmmaker Brian Rose, who had already spent years researching how the lost scenes were originally composed, and is advised by Welles' biographer Simon Callow.

Why was "The Magnificent Ambersons" originally cut down?

After a test screening didn't perform as expected, RKO Pictures panicked about the film's box office potential. The studio removed 43 minutes (roughly one-third of Welles' original cut) and added a different, more upbeat ending that Welles never intended. The cut footage was permanently destroyed rather than preserved in the studio's vaults. Orson Welles, who was filming in South America at the time, was unable to prevent this editing and considered it the greatest tragedy of his filmmaking career. Many film historians now agree with Welles' own assessment that the original cut was superior to "Citizen Kane," making this destruction one of cinema's most significant losses.

What are the main technical challenges the Fable team faces in recreating the lost footage?

The primary technical challenges include generating convincing deepfakes of deceased actors that match their actual performances (Fable has reported issues like two-headed recreations of Joseph Cotten), matching 1942 cinematography aesthetics with modern digital tools, capturing the subtle emotional authenticity of period performances, and ensuring digital elements integrate seamlessly with surviving live-action footage. Additionally, there are challenges in recreating the specific visual and performance choices that would have come from Welles' actual direction during production—choices that aren't documented in scripts or photographs but emerged from his real-time creative decisions on set.

What are the ethical concerns about this project?

Key ethical concerns include questions about authenticity and whether AI-generated footage should be presented as a restoration of the original work or acknowledged as speculative interpretation; issues around recreating deceased actors' likenesses without explicit consent from their families; questions about who has the authority to remake an artist's work posthumously; concerns that successful completion might establish a problematic precedent where incompleteness is treated as something that should always be remedied with technology; and broader worries that normalizing AI recreation of lost art could lead to erosion of archival standards and historical authenticity in cultural preservation.

Has Orson Welles' family approved the project?

Welles' daughter Beatrice initially expressed skepticism but has reportedly moved toward cautious support, stating that she now believes "they are going into this project with enormous respect toward my father and this beautiful movie." However, not all stakeholders are supportive. Melissa Galt, daughter of actress Anne Baxter who performed in some of the missing sequences, expressed opposition, saying her mother "would not have agreed with that at all," viewing the recreation as "not the truth" and "not the original." The project has also gained support from Simon Callow, a prominent Welles biographer who is currently working on an authorized multi-volume biography.

What does "right of publicity" mean in the context of deceased actors?

Right of publicity is the legal right to control and profit from the use of one's name, image, likeness, and identity. For deceased individuals, this right typically passes to their estate or heirs and varies significantly by jurisdiction. California, for example, extends publicity rights for 70 years after death, which could potentially prevent AI recreation of actors without family consent. However, the law is inconsistent across jurisdictions, and there's significant legal uncertainty about whether posthumous deepfakes and digital recreations of deceased people fall under traditional publicity rights protections. This legal ambiguity is one reason Fable has had to navigate complex permissions and potentially faces future legal challenges.

How does this project differ from traditional film restoration?

Traditional film restoration works with material that physically survives—it stabilizes deteriorating film stock, removes scratches and damage, color-corrects faded imagery, and attempts to reveal the original work as clearly as possible. The "Magnificent Ambersons" restoration would be fundamentally different because it would be creating entirely new sequences that don't exist in any physical form. Instead of revealing what's already there, it would be fabricating footage based on historical documentation, scripts, and educated speculation about what Welles might have filmed. This represents a shift from revealing authenticity to creating plausible approximation, which is conceptually distinct from preservation and raises different questions about authenticity and historical accuracy.

What happens to the incomplete original version of the film if Fable's project succeeds?

Ideally, the incomplete original version that was actually directed by Orson Welles would be preserved and continue to be presented as the primary canonical text. The AI-reconstructed sequences would exist as supplementary material, clearly labeled as speculative recreation and available for those interested in understanding the project's historical and technical dimensions. However, there's concern among film archivists that successful AI completion might gradually shift cultural expectations and institutional practice toward preferring polished complete versions over authentic incomplete originals, which could eventually marginalize the authentic version in favor of the simulation.

What broader implications does this project have for how we preserve lost art?

The project's success or failure could establish precedent for how institutions approach thousands of other lost works in cinema, literature, music, and visual art. If AI recreation becomes accepted and normalized, archives and studios might begin systematically filling gaps in damaged or incomplete works, potentially leading to a cultural landscape where loss is routinely remedied rather than accepted. This could shift fundamental practices around artistic authenticity and historical preservation. Conversely, if the project faces significant legal, ethical, or cultural resistance, it might establish boundaries around what AI should be used for in cultural preservation, keeping these tools focused on enhancement and restoration of existing materials rather than generation of entirely new creative content.

Final Reflection

After spending time thinking through all the dimensions of this project—technical, ethical, legal, and philosophical—I'm left with a position that's more complex than my initial skepticism but still troubled by some of the implications.

The Fable team seems genuinely dedicated to cinema and to honoring Welles' legacy. The technical work they're doing is impressive. The research underlying the project is rigorous. These aren't people cynically exploiting a dead filmmaker for profit.

But that goodness of intention doesn't resolve the fundamental questions. It's still the case that what they'll produce, at best, will be a sophisticated fan interpretation rather than Welles' actual work. It's still the case that successful completion might establish precedents with long-term consequences for how culture treats lost art. It's still the case that some losses might be worth preserving rather than remedying.

I'm less angry about the project now than I was initially. But I'm not convinced it's the right call either. I think it's a genuinely difficult situation where reasonable people can disagree, which is both more honest and less satisfying than simply declaring the project good or bad.

What matters most now is that as this project develops, it stays honest about what it is, engages seriously with all stakeholders, and doesn't oversell the authenticity of what it creates. If it can do those things, it might contribute something valuable to our understanding of cinema history while remaining appropriately modest about its own limitations.

And perhaps, if we're lucky, it will prompt a broader conversation about what we lose when we insist on technological completeness, and what we might gain by accepting that some art, once damaged by time or human error, is meant to exist as a beautiful ruin.

Key Takeaways

- Fable's project to recreate 43 minutes of destroyed Orson Welles footage represents a fundamental shift from film restoration to AI-generated creative speculation

- The ethical concerns—authenticity, authenticity, precedent, and whose creative vision matters—are legitimate even if the team's intentions are genuinely respectful

- AI struggles with exactly what matters most in cinema: subtle performance choices, directorial decision-making, and the ineffable aspects of human creative vision

- Successful projects establish cultural precedents; if Fable succeeds, expect studios to systematically use AI to 'complete' other damaged or lost works

- Some art may be better preserved as incomplete and damaged than replaced with seamless simulations; loss itself carries historical and philosophical meaning

Related Articles

- Microsoft's AI Content Licensing Marketplace: The Future of Publisher Payments [2025]

- Larry Ellison's 1987 AI Warning: Why 'The Height of Nonsense' Still Matters [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

- AI Chatbot Dependency: The Mental Health Crisis Behind GPT-4o's Retirement [2025]

- How Darren Aronofsky's AI Docudrama Actually Gets Made [2025]

- ElevenLabs 11B Valuation [2025]

![AI Recreation of Lost Cinema: The Magnificent Ambersons Debate [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-recreation-of-lost-cinema-the-magnificent-ambersons-debat/image-1-1770581274970.jpg)