Larry Ellison's 1987 AI Warning: Why 'The Height of Nonsense' Still Matters

It's January 2025. AI is everywhere. Your email sorts itself. Your phone guesses what you'll say next. Companies are scrambling to slap "AI-powered" onto products that don't need it. And if you're even slightly skeptical about whether every problem needs an artificial intelligence solution, you're probably tired of being dismissed as a Luddite.

But here's something weird: the smartest skeptic in tech might have been a man named Larry Ellison, speaking in 1987.

That's right. Thirty-eight years ago, long before machine learning became a commodity and LLMs started writing marketing copy, Oracle's co-founder sat down at a Computerworld roundtable and said something that sounds almost radical today. He argued that applying AI to everything was "the height of nonsense." He wasn't anti-AI. He was anti-stupid-AI-application.

And he was exactly right.

We've forgotten this debate. We've forgotten Ellison's argument. And in forgetting it, we've made the exact mistakes he warned about. This isn't just tech history nostalgia. This is a playbook for why your company's AI initiative might be broken, and how to fix it.

Let's talk about what happened in that 1987 conference room, why Ellison's logic still holds, and what it means when every vendor in the world is trying to convince you that AI is the answer to problems you don't have.

TL; DR

- Ellison's core argument: AI should solve specific, hard problems, not replace human judgment everywhere

- His warning: Building entire systems on AI when simpler solutions work is wasteful and backward

- The mistake we're making now: Exactly what he warned about, treating AI as a universal architecture layer instead of a targeted tool

- The modern parallel: Every vendor adding chatbots to their software, even when users don't want them

- The real lesson: Smart companies embed AI surgically where it creates genuine value, not as a checkbox feature

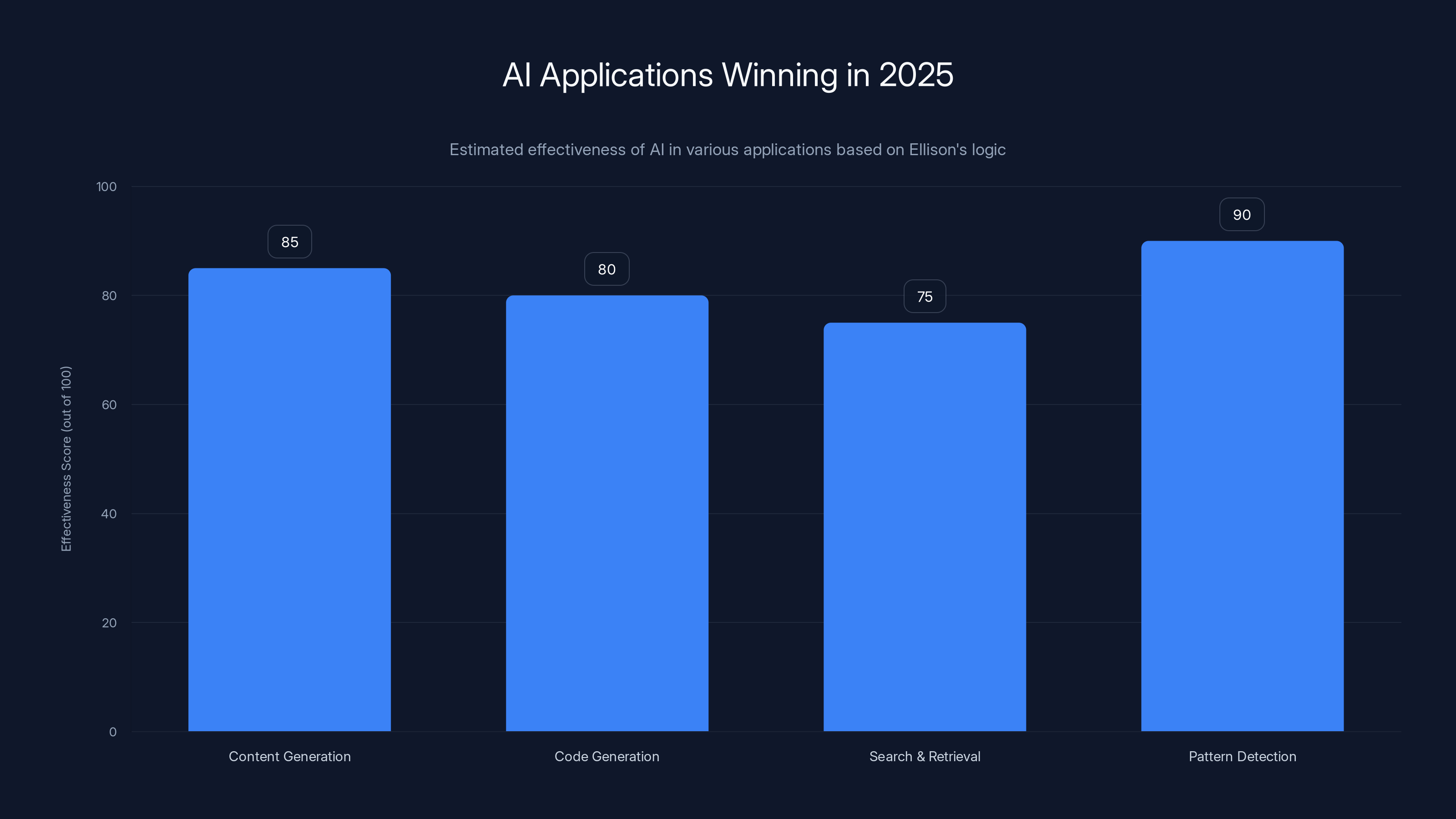

AI excels in pattern detection and content generation due to its ability to handle complex, large-scale tasks that are beyond human capacity. Estimated data.

The 1987 Conference Room: When AI Was Overhyped the First Time

To understand why Ellison's argument mattered, you need to understand the moment. The year was 1987. Personal computers were becoming mainstream. Databases were evolving. And expert systems were supposed to be the future.

Expert systems were the 1980s version of today's generative AI hype. They encoded human knowledge and decision-making rules into software. Accountants' judgment. Engineers' expertise. Insurance underwriters' logic. All of it could be captured in a system. The promise was seductive: automate the experts, cut costs, scale human knowledge infinitely.

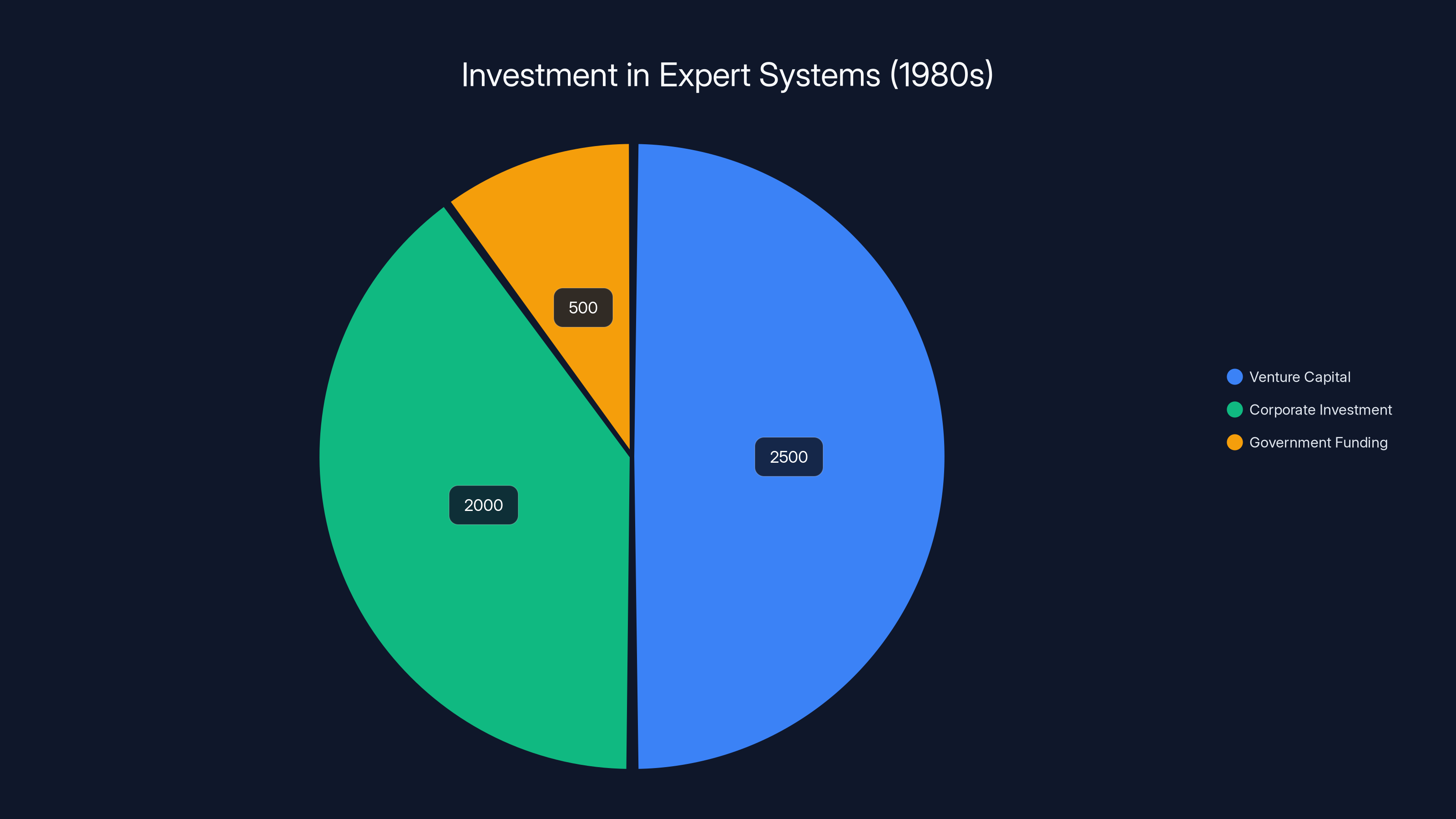

Companies were pouring money into it. Venture capital was flowing. Researchers were excited. Every major tech vendor saw expert systems as the next architectural revolution. Tom Kehler from Intellicorp was evangelizing them hard. John Landry from Cullinet was arguing they could form the foundation for entire application suites.

And Ellison... Ellison wasn't buying it.

Esther Dyson, moderating the discussion, noticed something odd. Ellison's vision of AI didn't match the others'. Where Kehler and Landry saw AI as a new layer, a fundamental shift in how you build systems, Ellison saw it as a tool. A specific tool. For specific jobs.

"Your vision of AI doesn't seem to be quite the same as Tom Kehler's," Dyson said, pressing him. "He differentiates between the AI application and the database application, whereas you see AI merely as a tool for building databases and applications."

Ellison nodded. That was exactly right.

He wasn't rejecting AI. He was rejecting the idea that AI should be your default architecture. That's a crucial distinction, and almost nobody in 2025 is making it.

The "Height of Nonsense" Moment: When Ellison Drew the Line

Here's where the conversation got sharp. Dyson suggested a hypothetical: an automated system that transfers funds if a checking account balance drops below a certain threshold. Sounds reasonable, right? Automated decisioning. Smart.

Ellison shut it down immediately.

"That can be performed algorithmically because it's unchanging," he said. "The application won't change, and to build it as an expert system, I think, is the height of nonsense."

There it is. The line in the sand.

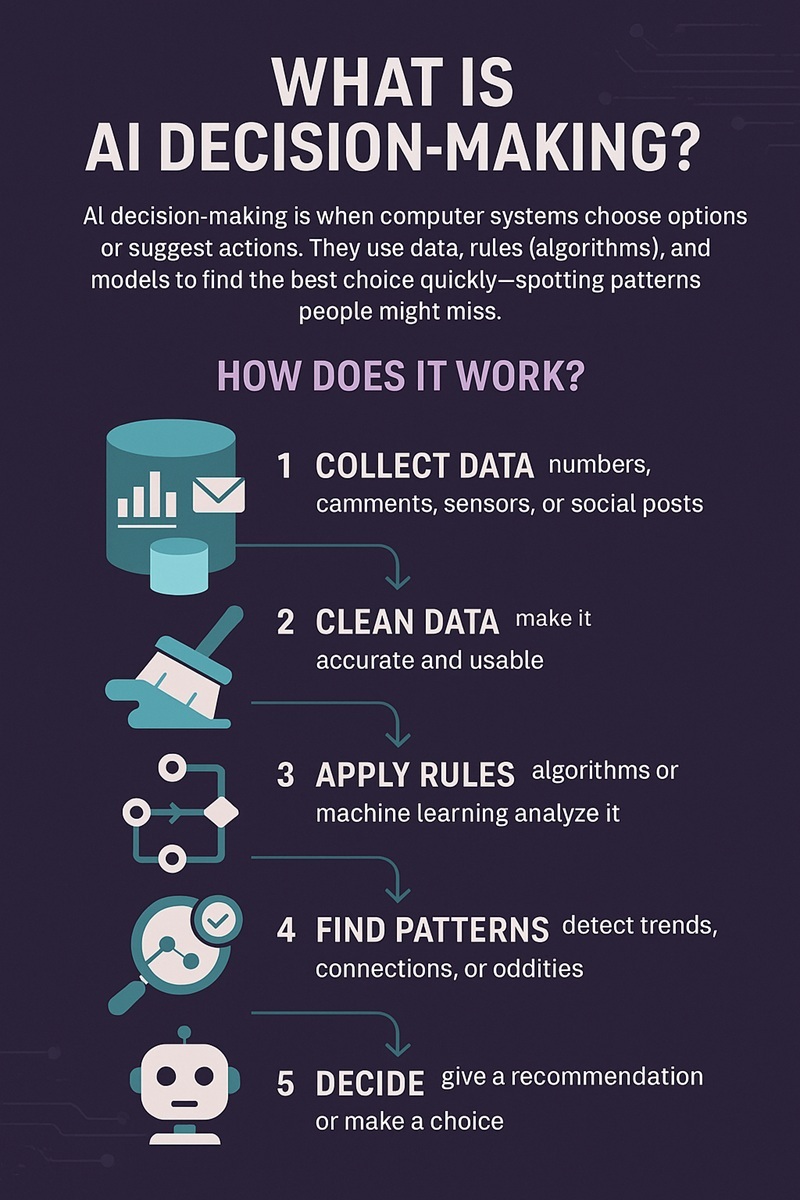

Ellison's logic was clean: if a problem is unchanging, if it doesn't require judgment, if it's just following a rule, then AI is overkill. You don't need expert systems to perform a fixed calculation. You don't need machine learning to execute a boolean condition. You need... a simple algorithm.

This is the move that separates thinking from hype. And in 2025, almost nobody's doing it.

Consider what's happening right now in real companies. Teams are implementing AI chatbots for FAQs when a search box would work better. They're training models to detect fraud when rule-based thresholds catch 95% of cases. They're using GPT to summarize internal documents when a five-sentence manual would suffice. They're checking a box labeled "AI-powered" and calling it strategy.

Ellison would call it nonsense. He'd be right.

During the 1980s, expert systems attracted over $5 billion in investments, with venture capital leading at 50%. Estimated data.

Why Ellison Distinguished Between Problems That Demand Judgment and Problems That Don't

Ellison's framework was actually quite sophisticated, even if he was explaining it in 1987 terms. He carved out a critical distinction:

Problems requiring judgment: Complex, contextual, variable. An underwriting decision. A customer complaint. A system architecture choice. These problems change because the world changes. Rules evolve. Context matters. You need human expertise, or AI trained on expertise.

Problems requiring execution: Fixed, repeatable, algorithmic. Processing a standard order. Transferring funds when a condition is met. Recording a transaction. These don't change. They follow rules. You need fast, reliable execution, not intelligence.

Ellison's point: don't use a hammer to drive a screw. Don't use AI when you need a database transaction. Don't use machine learning when you need a calculation.

He went further. He actually criticized the very idea that "everything we do requires expertise." Because it doesn't. Some things are just work. Repetitive, procedural, expertise-free work. Clerks processing orders. Tellers processing checks. These jobs don't require intelligence. They require speed and accuracy.

You could automate them with AI. That would be stupid. You could automate them with rules and transactions. That would be smart.

This distinction has completely vanished from how companies talk about AI in 2025. Everyone talks like all work is unique, contextual, and judgment-heavy. In reality, most work is repetitive. And for repetitive work, you don't need artificial intelligence. You need proper engineering.

The Fifth-Generation Tools Vision: What Ellison Actually Believed In

Here's what makes Ellison interesting. He wasn't just saying "no" to AI. He was saying "yes" to something different.

He believed in what he called "fifth-generation tools." Not programming languages. Not expert systems. Something else entirely. A way to build systems declaratively, by describing intent rather than writing instructions.

Picture this: a developer and a user sit down together. The user describes what they need. The developer doesn't go away and code it for three months. Instead, the developer sits there and builds the system while the user watches. The user says "no, that's not what I meant," and the developer changes it. Interactive. Responsive. Collaborative.

That's not really AI in the 1987 sense. But it's automation. It's leveraging tools to remove procedural complexity so that builders can focus on intent, not mechanics.

Does this sound like anything you know?

It sounds like modern IDE features. It sounds like no-code platforms. It sounds like prompt-based development. It sounds like the good parts of what AI can do: amplify human intent, remove boilerplate, let smart people build faster.

Ellison understood something fundamental: the real value isn't in automating every decision. It's in automating the grunt work so that humans can focus on the decisions that matter.

The 1987 Expert Systems Bubble and the 2025 AI Bubble: A Pattern Emerges

This is where history gets uncomfortable.

The expert systems movement had genuine promise. Smart people were excited about it. Real money was flowing. Real research was happening. And then... it mostly failed. Not completely. Some applications worked. But the vision of expert systems becoming the foundation of enterprise software? That didn't happen. The promises outpaced reality. The technology was fragile. Maintaining knowledge bases was nightmarish. Rules changed and the systems broke.

By the early 1990s, expert systems had mostly disappeared from the hype cycle. Companies had wasted billions on implementations that didn't deliver.

Now we're in 2025, and we're watching a similar pattern. AI is everywhere. The promises are enormous. The capital is flowing. Real breakthroughs are happening. And at the same time, a lot of companies are implementing AI solutions for problems that don't need them.

Not all AI is the 1980s expert systems movement. Modern LLMs are actually much more capable. They can genuinely do things that are hard to do with traditional programming. But the pattern is the same.

Vendors are overpromising. Companies are over-implementing. Solutions are being deployed without clear ROI. Features are being added because they're trendy, not because they solve problems.

Ellison saw it coming. He didn't have a time machine. He just understood incentives. When there's hype around a technology, there's a ton of pressure to use it everywhere. The vendors are pushing it. Your competitors might be trying it. Your board might be asking about it. So you do it.

And you often regret it.

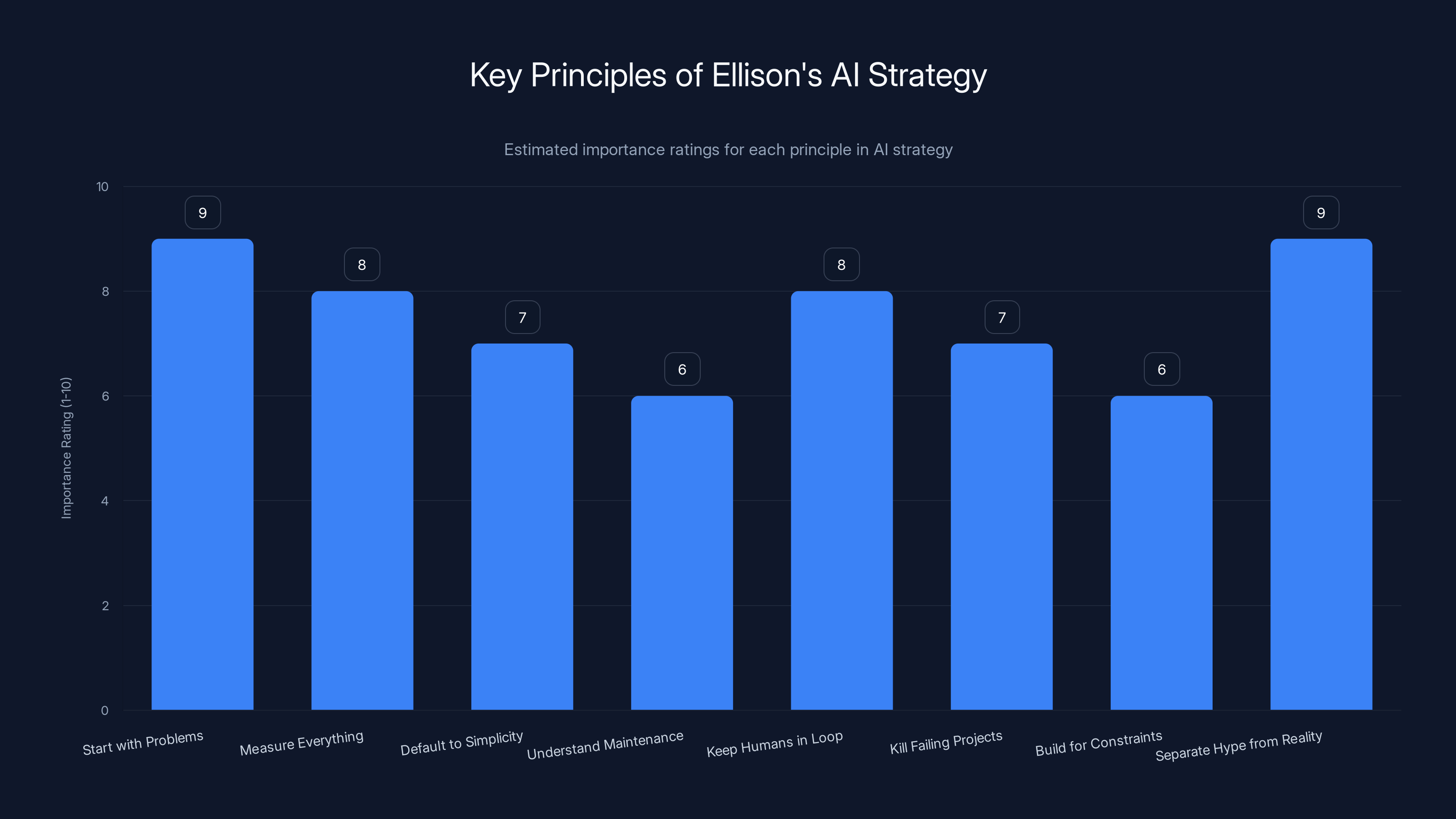

The chart estimates the importance of each principle in Ellison's AI strategy, highlighting 'Start with Problems' and 'Separate Hype from Reality' as crucial elements. Estimated data.

The Modern Applications of Ellison's Logic: Where Does AI Actually Win?

Okay, so if Ellison's logic holds, where should companies actually use AI?

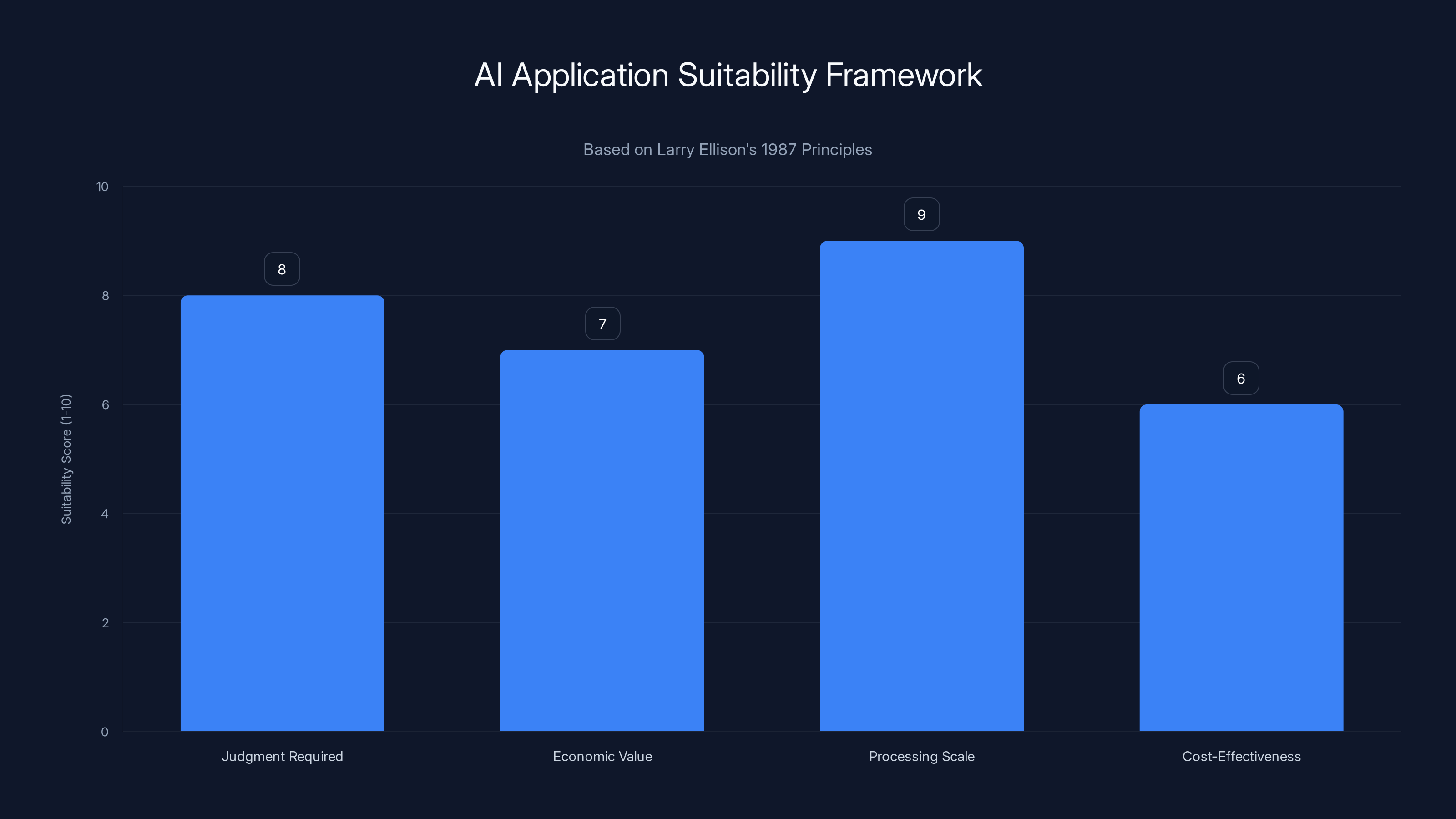

According to his framework, in places where:

-

The problem is genuinely complex and contextual. Not procedural. Not rule-based. Actually hard. Diagnoses. Strategic decisions. Content moderation at scale. Customer insight. Fraud detection in novel patterns. These are places where judgment is required and rules are insufficient.

-

The cost of getting it wrong is bounded. AI isn't perfect. If you're using AI to recommend a product, and the recommendation is wrong, the customer just doesn't buy. No harm. If you're using AI to decide whether to approve a loan, and it's wrong, you might discriminate. Different calculus.

-

The problem actually requires scale that humans can't provide. You need to analyze a million documents. You need to respond to thousands of customer issues. You need to detect subtle patterns across vast datasets. These are the places where AI can do something humans literally cannot.

-

It actually changes the economics of the business. Not marginally. Not 5% better. Does it fundamentally change what's possible? Does it unlock a new product? Does it reduce costs by an order of magnitude?

By that standard, here's where AI is actually winning in 2025:

Content generation: LLMs can draft, summarize, and create text at scale and speed that would be economically impossible otherwise. This is genuine value.

Code generation: Tools like GitHub Copilot don't replace programmers, but they eliminate boilerplate and speed up the drudgework. This changes the economics of development.

Search and retrieval: AI can understand semantic meaning in a way keyword matching can't. This unlocks genuinely new search experiences.

Pattern detection: Analyzing images for medical conditions, detecting anomalies in sensor data, finding patterns in logs. This is where AI excels because the patterns are too subtle or too numerous for humans to see.

Personalization at scale: Recommending products, suggesting next actions, tailoring experiences to individuals. This can be done with simple stats, but AI does it better.

Conversation and interaction: Chatbots, voice assistants, interfaces that feel natural. When done well, this is genuinely better than button-clicking.

Notice what's not on this list:

- Automating decisions that have clear rules

- Replacing human judgment where judgment is required and people know how to exercise it

- Adding complexity to simple systems

- Using AI because competitors use AI

- Implementing AI without measuring impact

This is where Ellison's logic is most useful. It's a filter. It helps you distinguish between AI that's genuinely valuable and AI that's just expensive complexity.

The Organizational Problem: Why Smart Companies Still Do Stupid AI Things

So if Ellison's logic is sound, why do smart companies keep making bad AI bets?

It's not stupidity. It's incentives.

Vendor pressure: You're talking to a sales team that sells AI solutions. They have a financial incentive to convince you that you need AI. You should assume they're biased.

FOMO: Your competitors might be using AI. You don't know if it's working for them. But the uncertainty creates pressure. You don't want to be left behind.

Executive pressure: Your board might be asking about AI. They've read the same headlines you have. They think it's important. So you need to show that you're doing it.

Resume incentives: Your product manager or engineering lead might benefit from building something called "AI-powered." It looks good on a resume. It signals cutting-edge thinking. Even if the AI part is unnecessary.

Measurement problems: It's hard to prove that AI didn't work. You can always say "we're still optimizing." It's easy to declare victory when you're not sure what you're measuring.

These incentives are real. And they push companies toward over-implementing AI, exactly the way they pushed companies toward over-implementing expert systems in the 1980s.

The fix isn't to stop using AI. The fix is to change incentives. Reward teams for solving problems efficiently, not for using trendy tech. Measure impact, not adoption. Ask hard questions. Challenge vendor assumptions.

Be like Ellison. Be contrarian. Ask: "Does this actually need AI?"

The Knowledge Problem: What Changed Between 1987 and 2025

Now, Ellison wasn't perfect. He made assumptions in 1987 that didn't quite hold up. He believed knowledge could be encoded into rules. He thought that once you captured an expert's decision tree, you were done.

Turns out, expertise is messier than that. It's contextual. It's intuitive. It changes. It's hard to encode.

This is actually why modern AI is more capable than 1980s expert systems. LLMs don't encode rules. They learn patterns from data. They can handle ambiguity. They can do things that would be impossible with a traditional rule-based system.

So Ellison's framework holds up, but the boundaries have shifted.

Problems that used to require real human expertise? Some of them can now be done with AI. Not all. Not perfectly. But well enough that the economics change.

Problems that are purely procedural? They still don't need AI. A transaction is still a transaction. A rule is still a rule.

The sweet spot has moved. It's now: problems that require judgment, but where the judgment is pattern-based rather than explicit. Where intuition matters. Where context changes. Where there's signal buried in data.

These are genuinely valuable places for AI. And Ellison would probably agree.

But he'd still push back hard on using AI for procedural work. That hasn't changed. And it's still the most common mistake.

AI should be applied to problems requiring judgment, economic value, and scale, as per Ellison's framework. Estimated data based on principles.

The Economics Question: When Does AI Actually Save Money?

Here's a question Ellison would ask: what's the ROI?

AI systems have costs:

- Development: Building, training, testing

- Operations: Running inference, storing models, updating as things change

- Maintenance: Fixing failures, retraining when accuracy drifts, managing edge cases

- Opportunity cost: Engineering time you could have spent elsewhere

For AI to make sense, the benefits have to exceed these costs. Not by 5%. By a lot.

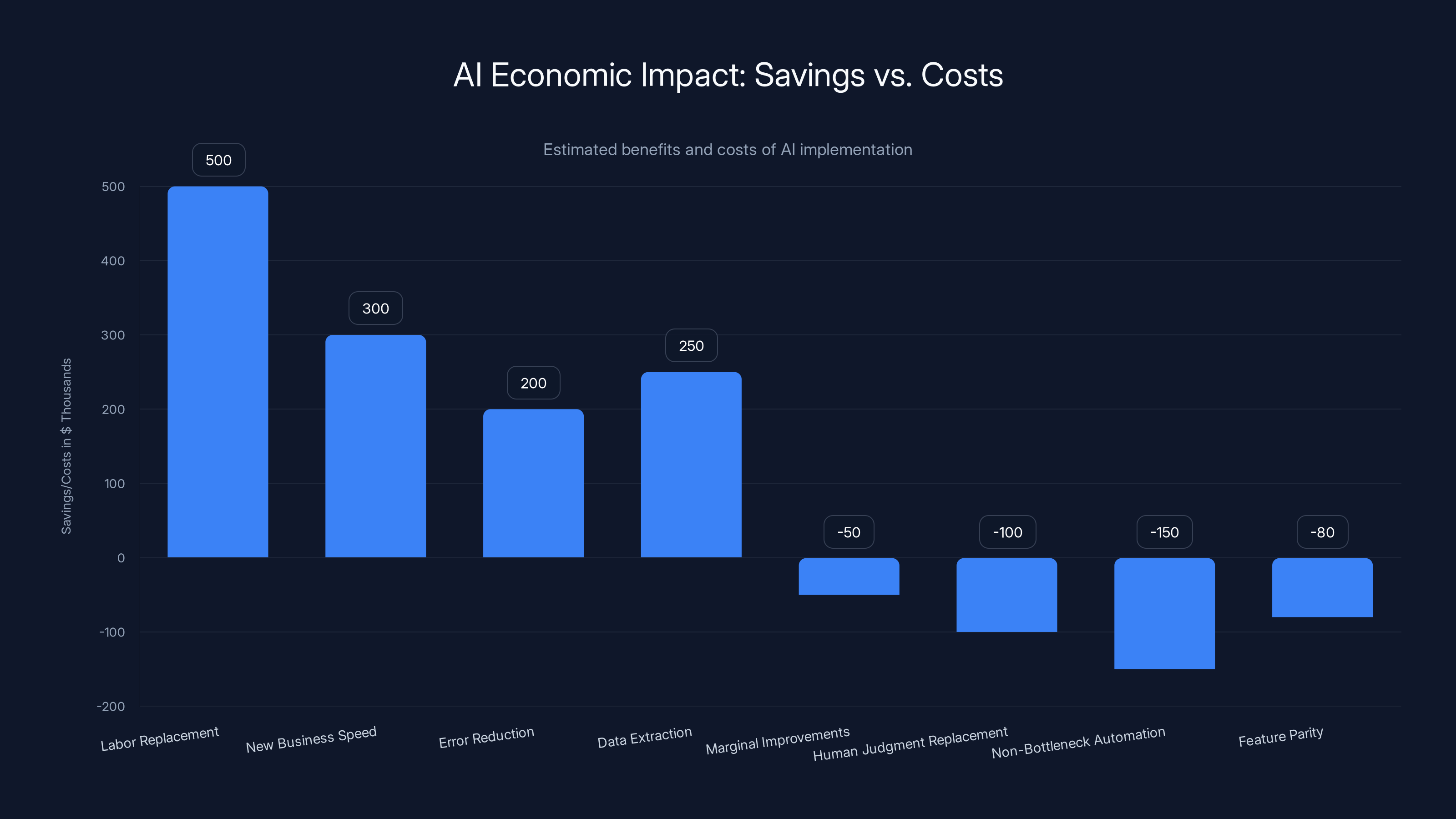

Where does AI actually win on economics?

Labor replacement at scale: You had a team of 100 people doing a task. Now you have a team of 10 people and an AI system. That's a real savings.

Speed that enables new business: You can now serve customers in real-time that you couldn't serve before. That's new revenue.

Accuracy gains that reduce costly errors: Fraud detection that prevents 10% more fraud. That's real money.

Data extraction from unstructured sources: You have a million documents and humans couldn't read them all. Now you can. That's value creation.

Where does AI lose on economics?

Marginal improvements to existing processes: Your search is 5% better with AI. But you didn't build a team for that 5%. You just added complexity.

Replacing human judgment that already works: Your analysts are making good decisions with 95% accuracy. AI matches them at 96%. You spent a million dollars to save nothing.

Automating work that's not actually a bottleneck: It would be nice to automate data entry, but it's not slowing you down. Now you have an AI system to maintain. That's a net cost.

Feature parity with no strategic difference: Your competitor's product has an AI chatbot. So you add one. But it doesn't change why customers buy from you. You spent money to match a feature that doesn't matter.

Ellison's instinct was right here too. You need to do the economics. You need to know what you're optimizing for. And you need to be honest about whether AI actually optimizes it.

Most companies skip this step. That's a mistake.

The Selective Employment Principle: Ellison's Framework for AI Strategy

Ellison summed up his view with a principle: "expert systems should be selectively employed."

Selectively. Not everywhere. Not as a default architecture. Selectively, where they actually solve problems.

How do you apply this principle in 2025?

Step 1: Identify real problems. Not imagined problems. Not "what if we could..." problems. Real problems. Customers complaining about X. Employees spending too much time on Y. Processes breaking at Z.

Step 2: Measure the current state. How long does it take? How much does it cost? How often does it fail? What's the impact? You need baseline numbers.

Step 3: Design a solution. Start with the simplest possible solution. Can you fix it with a better process? A better tool? A different organizational structure? Only if the answer is no, move to the next step.

Step 4: Consider AI as one option. Could AI help? What would it do? What would it cost? What would it require to maintain?

Step 5: Compare against the baseline. Not against magic. Against what you have now. Can you measure the improvement? Is it worth the cost?

Step 6: Set kill criteria. What would it take for you to say "this AI project isn't working"? If you don't define this upfront, you'll never actually kill it. You'll just say "we're still optimizing."

This framework is unsexy. It's not "let's revolutionize with AI." It's "let's solve this problem efficiently."

But it's how you avoid being the company that spent a fortune on AI and has nothing to show for it.

The Human-AI Boundary Problem: What Stays Human and What Gets Automated

Here's something Ellison touched on that's even more relevant in 2025: the question of what work should remain human.

He argued that a systems analyst is an expert too. Partially automating their function is a form of expert system. But you shouldn't automate it away entirely. You need the human judgment. You need the creativity. You need the person who understands the business deeply.

In 2025, we're having the same conversation about every profession. Can AI write better code than developers? Sometimes. Can it write marketing copy faster than copywriters? Yes. Can it analyze data better than analysts? Depends.

But the question isn't whether AI can. The question is whether you should.

There's a difference between:

Augmentation: AI helps humans do their job better. A developer uses AI to avoid boilerplate, so they can focus on architecture. A writer uses AI for drafts, so they can focus on voice and truth. An analyst uses AI for data extraction, so they can focus on insight.

Automation: AI replaces the human entirely. No developer. No writer. No analyst. Just AI.

Augmentation usually works. Automation usually doesn't. Because the work that matters most isn't the routine part. It's the judgment part. The part that requires understanding context and stakes and values.

Ellison would probably say: use AI to remove the procedural stuff. Keep the judgment with humans. That's where the value is.

The mistake is treating all work as routine and automating it away. That's how you end up with AI-generated content that says nothing. AI code that's syntactically perfect but architecturally wrong. AI analysis that finds correlations but no truth.

The sweet spot is: AI handles the grunt work. Humans handle the thinking.

AI can lead to significant savings in areas like labor replacement and new business speed, but may incur costs in non-critical automations and feature parity. Estimated data.

The Warning Signs That Your AI Implementation Is Becoming "The Height of Nonsense"

Let's get practical. What does a bad AI implementation actually look like?

Warning sign 1: You're measuring adoption, not impact. Your chatbot handles 10,000 conversations per month. Great. But customers still abandon in the middle. Impact is negative.

Warning sign 2: You can't explain why AI is better than the previous approach. "It's more scalable." Okay, but were you hitting a scale problem? "It's more accurate." By how much? Did it matter?

Warning sign 3: The AI system is more complicated than the problem it's solving. You have a machine learning pipeline with three models and a Kafka cluster to handle five use cases that used to work fine with a rule engine.

Warning sign 4: You're not measuring what actually matters. You're tracking model accuracy, but the actual metric you care about is customer satisfaction, and it hasn't moved.

Warning sign 5: The team that maintains it is growing, not shrinking. You built an AI system to reduce labor costs, but now you need five people to keep it running.

Warning sign 6: You have no kill criteria. You've been running this "experiment" for 18 months. It's still costing money. But nobody's willing to say it failed.

Warning sign 7: The problem was actually procedural, and you solved it with machine learning. You're automating a decision that has clear rules. This is peak nonsense.

Warning sign 8: It only works if you have the perfect data. Your model is 99% accurate in the lab and 60% accurate in production. You're now chasing data quality, and the returns are diminishing.

If you see these signs, you're probably experiencing the 2025 version of the 1980s expert systems failure.

It's not that AI is bad. It's that it's being applied badly.

The Vendor Ecosystem Problem: How Sales Incentives Drive Bad AI Decisions

This is the part of Ellison's logic that people often miss. He wasn't just saying "be skeptical of AI." He was implying: "be skeptical of people who sell AI."

Vendors make money by selling AI. They have a financial incentive to:

- Convince you that your problem is unsolvable without AI

- Oversell the capabilities of their AI system

- Downplay the implementation cost and complexity

- Hide the maintenance burden

- Make bold claims about ROI

These aren't evil people. They're just operating within a system that rewards them for selling more AI.

You should assume every vendor demo is optimized. The data is clean. The use case is perfect. The results are good. What you don't see is all the edge cases where it fails.

Ellison would tell you: talk to people who actually use it. Talk to them off the record. Ask them whether it solved the problem. Ask them what it cost to maintain. Ask them whether they'd do it again.

This is true of everything, but it's especially true of AI because:

- The technology is new enough that nobody's an expert. So claims are harder to verify.

- The complexity is high. You can't easily evaluate the approach without deep technical knowledge.

- The ROI is often vague. It's hard to prove whether the AI was responsible for improvements.

This creates space for overselling. And vendors fill that space.

The Organizational Learning Problem: Why Companies Keep Repeating Mistakes

Here's an uncomfortable truth: even if you understand Ellison's logic, your company might not follow it.

Why? Because organizations don't learn as fast as individuals do.

You read this article. You understand: don't use AI for procedural problems. Don't measure adoption instead of impact. Don't let vendors convince you something's a problem when it's not.

But six months from now, your company will still be pursuing an AI initiative that violates all these principles. Why?

Institutional momentum: Once a project is greenlit, it's hard to stop. People are hired. Budgets are allocated. It becomes political.

Measurement lag: You won't know whether something's working for 12-18 months. By then, everyone's psychologically invested.

Distributed decision-making: The person who green-lit the project isn't the person maintaining it. The person maintaining it isn't the person evaluating ROI. Nobody has full context.

Career incentives: People are rewarded for shipping features, not for truthful assessment of whether features matter.

Ellison understood this too. He wasn't just making a technical argument. He was making a cultural argument. He was saying: be willing to push back. Be willing to say no. Be willing to question assumptions.

That's rare. Most organizations optimize for consensus and momentum. They're risk-averse in the wrong way: they'll take big risky bets on trendy tech, but they won't take small social risks to say "I don't think this is the right approach."

Flipping this requires leadership. It requires saying: our competitive advantage is thoughtful technology decisions, not AI adoption.

Ellison did that at Oracle. It didn't always work out. But his instinct was right.

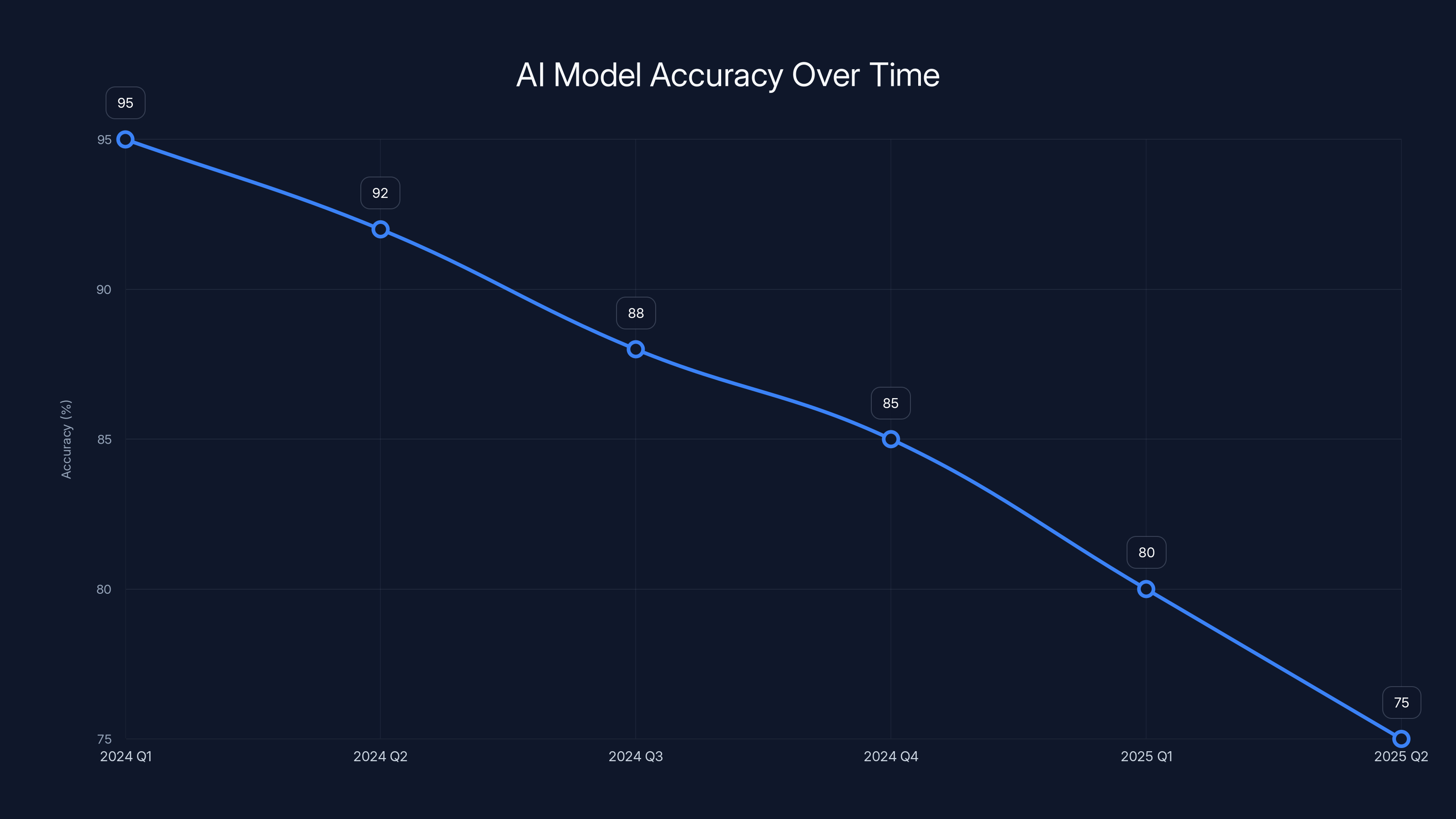

The chart shows a decline in AI model accuracy from 95% to 75% over six quarters, highlighting the issue of concept drift or model decay. Estimated data.

Where We Are in 2025: An Honest Assessment of AI's Role

Let's be clear about what's actually happened with AI in 2025.

The hype is real. The capability is real. But the implementation is mixed.

What's working:

- LLM-powered applications: Chat GPT and competitors have found genuine use cases. People use them. They're profitable.

- Code generation tools: Developers actually use AI to write code faster. It's genuinely valuable.

- Search and discovery: AI-powered search is better than keyword search. Users prefer it.

- Content generation: Writing, designing, creating: AI is making these faster.

- Recommendation systems: Products are better at suggesting what you want.

What's struggling:

- Autonomous decision-making: Most attempts to have AI make business decisions (without human review) have failed or required significant human involvement anyway.

- Perfect automation: Hoping that you can fully automate complex processes with AI. It doesn't work. You always need humans in the loop.

- Replacing judgment: Expecting AI to replace expertise. It doesn't. It helps experts work faster.

What's overblown:

- Artificial General Intelligence: The idea that AI will soon be able to do anything a human can do. We're nowhere close.

- Economic disruption: Will AI transform work? Yes. Will it happen as fast as people think? No. Organizational change is slow.

- Vendor promises: Whatever a vendor says your AI will do, expect it to do 70% of that, and require twice as much maintenance.

Ellison's core point still holds: apply AI where it solves real problems, not because it's trendy. Measure impact. Be willing to say no.

Most companies aren't doing this. Most are somewhere on the spectrum between "AI everywhere" and "waiting to see what happens."

The companies that will win are the ones that find the middle: using AI surgically, where it actually works, and being ruthless about everything else.

Building an AI Strategy That Actually Works: The Ellison Playbook

If you were going to build an AI strategy following Ellison's logic, what would it look like?

Principle 1: Start with problems, not solutions. Don't say "we should use AI." Say "here's a problem that costs us money, time, or customer satisfaction. Could AI help?"

Principle 2: Measure everything. Before you implement AI, measure the baseline. After you implement it, measure the impact. Be ruthless about attribution. Did AI help, or did something else?

Principle 3: Default to simplicity. The simplest solution that works is probably the best one. Prefer rules over machine learning. Prefer machine learning over deep learning. Prefer simpler models over complex ones.

Principle 4: Understand the cost of maintenance. Every AI system requires ongoing care. Budget for it. If you can't, don't build it.

Principle 5: Keep humans in the loop. AI should augment human judgment, not replace it. Especially for high-stakes decisions.

Principle 6: Be willing to kill projects. If something's not working after six months, stop. Sunken cost is still a cost.

Principle 7: Build for your constraints. Most companies don't have unlimited data or engineering talent. Build for what you actually have.

Principle 8: Separate the hype from the reality. Be skeptical of vendor claims. Be skeptical of industry benchmarks. Be skeptical of your own optimism. Test everything.

This isn't a fun strategy. It's not exciting. It won't get you headlines about "AI-powered transformation."

But it will actually work.

And 38 years ago, Ellison figured this out. Nobody listened then either. But the principles were right.

The Feedback Loop Problem: Why AI Gets Worse Over Time

Here's something that's become clearer in 2025: AI systems often degrade over time.

You launch a model. It works. Users interact with it. And then... something changes.

Maybe user behavior shifts. Maybe the world changes. Maybe feedback loops start influencing the training data. Your AI system, which was 95% accurate last year, is now 75% accurate.

This is called "concept drift" or "model decay." And it's not an edge case. It's the norm.

Most companies don't budget for this. They budget for building the system. They don't budget for maintaining it.

This is another reason to be Ellison-like: skeptical of system complexity. Complex systems have complex failure modes. Simple systems fail clearly and obviously. You notice and fix them.

If your AI model is degrading and you don't notice for six months, that's a problem. If your rule-based system is degrading, you'll notice the next day.

This favors keeping things simple. And favors monitoring and measurement. If you're not measuring your AI system's performance over time, you don't actually know if it's working.

The Real Lesson: What Ellison's 1987 Argument Teaches Us About 2025

Let's step back.

Ellison wasn't a Luddite. He wasn't anti-technology. He wasn't saying "AI is useless." In fact, he was betting on AI mattering. But he was betting on it mattering in specific, disciplined ways.

His real argument was: technology is a tool, not an end. Your goal is to solve problems. Some problems are best solved with AI. Most aren't. Be honest about which is which.

That's not a 1987 argument. That's a permanent argument. It applies to every technology. It applied to databases. It applied to the internet. It applies to cloud computing. And it applies to AI.

In every case, there's hype. In every case, there are problems that are actually best solved with the old approach. In every case, companies that move fast and break things lose to companies that think hard and move deliberately.

Ellison was saying: be the second kind of company.

In 2025, with AI everywhere, that's more relevant than ever.

FAQ

What did Larry Ellison actually say about AI in 1987?

Ellison participated in a Computerworld roundtable on expert systems and databases. His core argument was that AI should be applied selectively to solve genuinely difficult problems, not used as a default architecture for everything. He specifically called it "the height of nonsense" to build expert systems for simple, rule-based problems that could be solved algorithmically. He believed AI should enhance human capability and remove procedural complexity, not replace human judgment wholesale.

Why is Ellison's 1987 argument still relevant in 2025?

The patterns of hype, vendor overselling, and misapplication are identical to what's happening with modern AI. Companies are implementing chatbots for problems that need search functionality, using machine learning for what should be rule-based systems, and measuring adoption instead of impact. Ellison's core principle—that technology should solve real problems, not fill trendy niches—remains universally applicable and is being widely ignored.

How do you know if your company should use AI for a problem?

According to Ellison's framework, you should use AI if: the problem requires judgment or pattern recognition that goes beyond fixed rules, the problem is genuinely hard with clear economic value, the problem requires processing scale that humans can't manage, and the AI solution actually costs less or delivers significantly better results than alternatives. If the problem is procedural, rule-based, or already adequately solved, AI is probably unnecessary.

What's the difference between AI augmentation and AI automation?

Augmentation means AI helps humans do their jobs better by removing tedious work and surface-level decision-making, allowing them to focus on judgment and strategy. Automation means replacing humans entirely with AI. Augmentation usually works. Automation usually fails because the judgment part is where the actual value lives, and machines aren't good at that without human oversight.

Why do so many AI implementations fail to deliver ROI?

Most fail because companies measure adoption (how many people use it) instead of impact (whether it actually solves a problem people care about). Others fail because the problem being solved wasn't actually a bottleneck or cost-driver. Still others fail because the maintenance cost was severely underestimated. Finally, many fail because simpler, non-AI solutions would have worked better and cost less.

How should a company evaluate an AI vendor's claims?

Talk to actual customers who've implemented the vendor's solution. Ask them whether it solved the stated problem, what the implementation actually cost, how much ongoing maintenance it requires, and whether they'd do it again. Request a clear ROI model and ask what happens when the model degrades over time. Be skeptical of cherry-picked examples and assume vendor demos are optimized for success.

What's concept drift and why does it matter for AI systems?

Concept drift is when an AI model's accuracy degrades over time because user behavior, market conditions, or the problem itself changes. It matters because most companies don't budget for the continuous retraining and monitoring required to maintain AI system accuracy. A model that's 95% accurate on day one might be 75% accurate after a year if nobody's monitoring it and retraining it.

Should companies avoid AI entirely if Ellison was skeptical?

No. Ellison wasn't anti-AI. He was pro-thoughtfulness. He used AI selectively where it genuinely improved systems. The lesson is: ask hard questions before implementing AI. Measure impact. Compare against baselines. Be willing to say no. Don't implement AI because it's trendy. Implement it because it's the right solution for a real problem.

Conclusion: The Contrarian Position as Competitive Advantage

We've spent decades moving away from Ellison's position. The trend has been toward more AI, not less. More automation, not less. More complexity, not less.

And in many ways, that's been right. AI has genuinely improved products. Automation has genuinely improved productivity. More complexity has sometimes solved problems that simplicity couldn't.

But Ellison's core instinct—be skeptical, measure impact, use AI selectively—was right then and is right now.

The problem isn't AI. The problem is hype-driven implementation. And that's not a technological problem. It's an organizational one.

Fixing it means:

- Leadership that's willing to be contrarian: Saying no to trendy tech when it doesn't solve real problems.

- Clear measurement: Knowing what you're optimizing for and actually measuring it.

- Skepticism toward vendors: Recognizing that sales teams benefit from convincing you to buy, even if it's not right for you.

- Long-term thinking: Being willing to move slower to move better.

- Honest assessment: Actually asking whether the AI system is working or whether you're just committed to the idea of it.

Do all this, and you'll look weird compared to companies rushing into AI. You'll look conservative. Old-fashioned. Slow.

And in 18 months, you'll be the only one with an AI system that actually works and that you can afford to maintain.

That's what Ellison would bet on. And history suggests he'd be right.

Key Takeaways

- Ellison distinguished between problems requiring judgment (where AI can help) and procedural problems (where simple algorithms suffice)—a distinction most 2025 companies ignore.

- Building entire systems on expert systems/AI when simpler solutions work is 'the height of nonsense'—a principle violated by most modern AI implementations.

- Expert systems in the 1980s followed an identical hype-to-failure pattern now repeating with modern AI, suggesting organizational incentives drive bad technology decisions.

- AI augmentation (helping humans work faster) consistently outperforms AI automation (replacing humans), yet companies keep betting on the latter.

- Most AI implementations fail because they measure adoption instead of impact, underestimate maintenance costs, and solve problems that weren't actually bottlenecks.

- Ellison's framework for selective AI employment remains superior to vendor-driven AI maximalism: identify real problems, measure baselines, compare solutions, set kill criteria.

Related Articles

- Google Gemini Hits 750M Users: How It Competes with ChatGPT [2025]

- Network Modernization for AI & Quantum Success [2025]

- GPT-5.3-Codex: The AI Agent That Actually Codes [2025]

- AI Chatbot Dependency: The Mental Health Crisis Behind GPT-4o's Retirement [2025]

- ChatGPT Caricature Trend: How Well Does AI Really Know You? [2025]

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

![Larry Ellison's 1987 AI Warning: Why 'The Height of Nonsense' Still Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/larry-ellison-s-1987-ai-warning-why-the-height-of-nonsense-s/image-1-1770554294159.jpg)