Introduction: The Reality of AI in Medicine

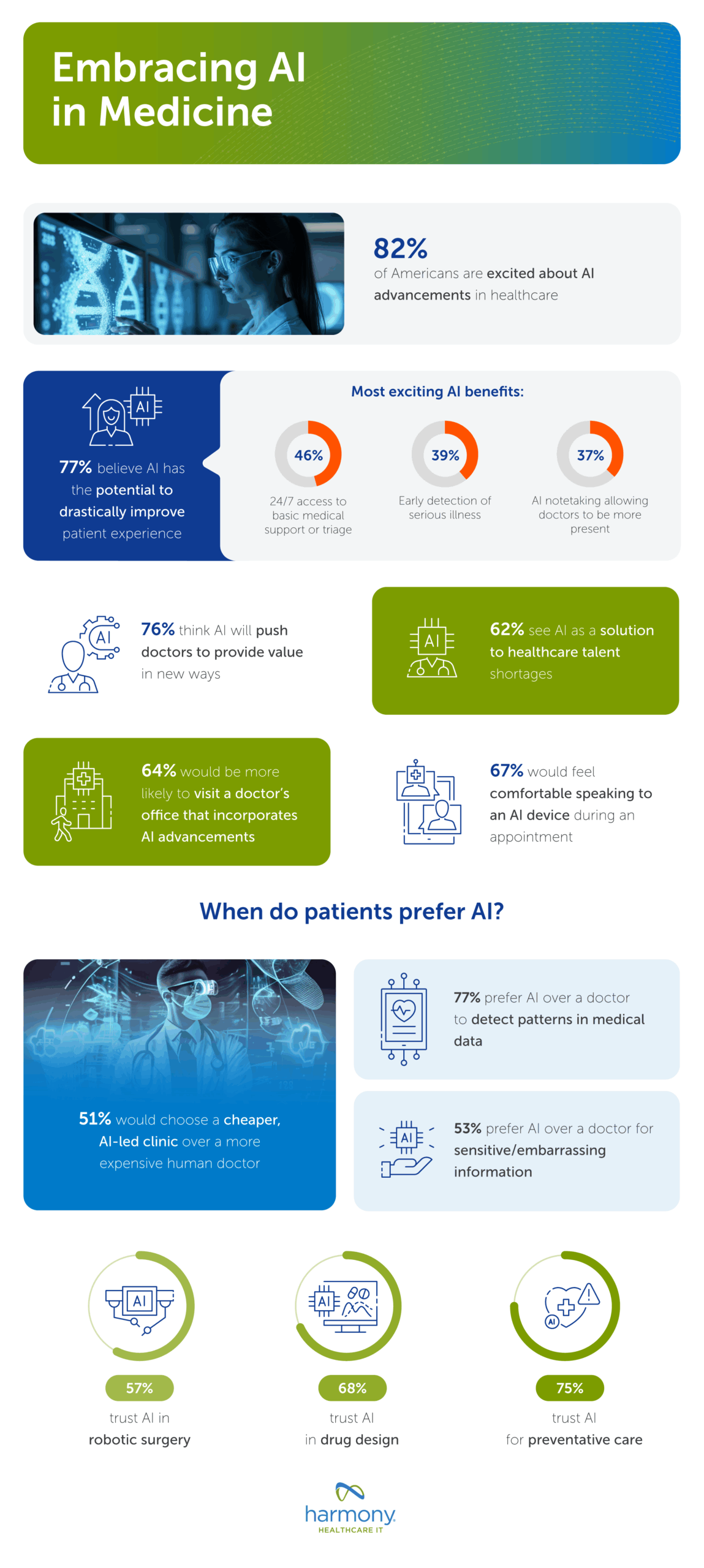

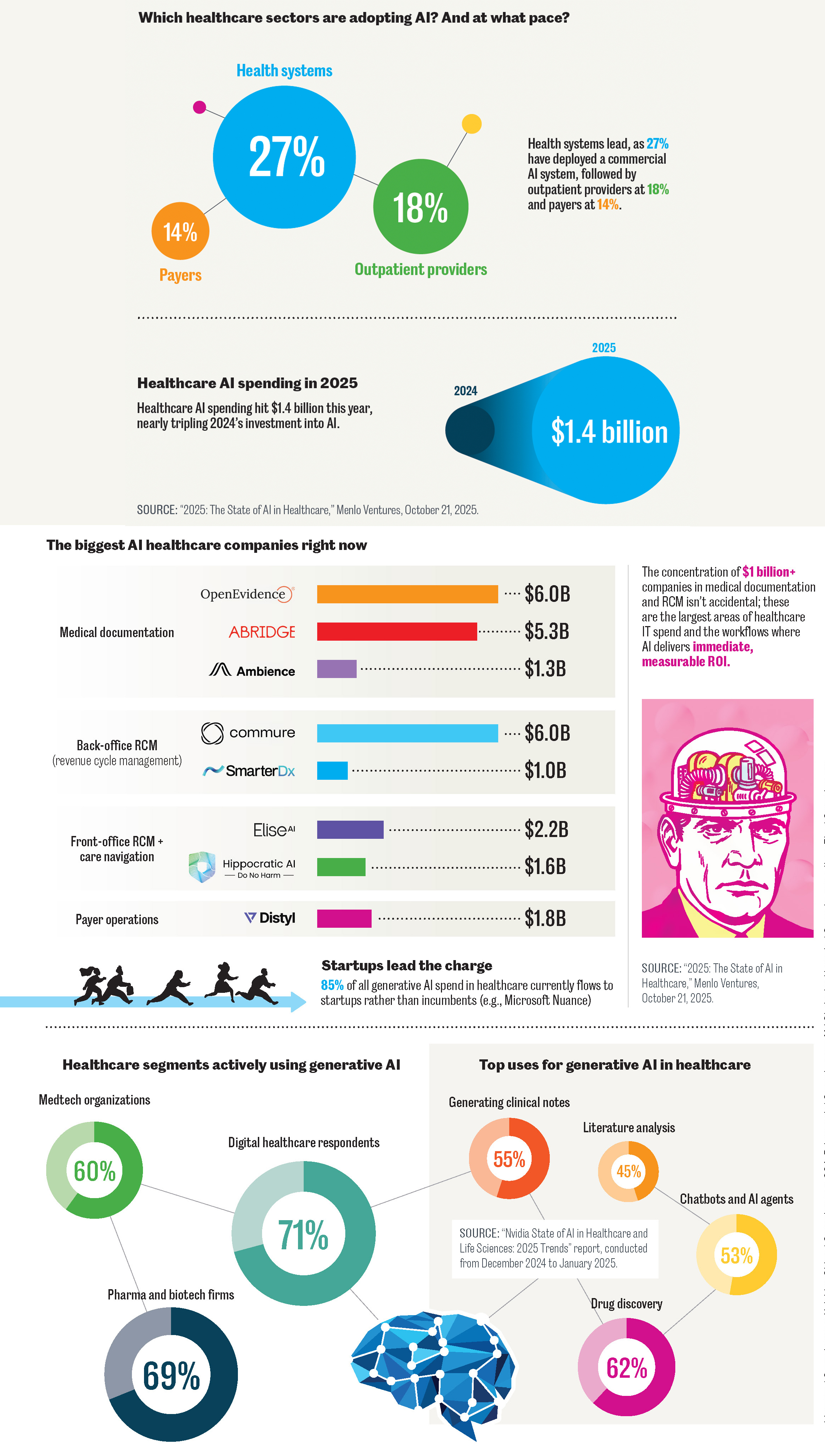

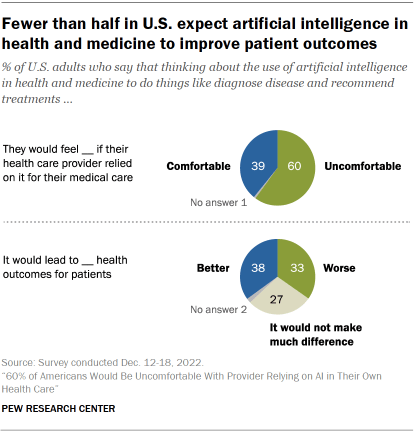

There's a paradox sitting at the intersection of artificial intelligence and healthcare that nobody's talking about openly enough. Over 230 million people globally chat with AI about their health every single week. That number is staggering when you think about it. People are uploading lab results, describing symptoms, asking about medication interactions, and trusting AI with some of the most personal medical information imaginable.

But here's where it gets complicated. When OpenAI and Anthropic recently launched healthcare-focused products, the reaction from actual doctors wasn't uniformly celebratory. It was more nuanced, more cautious, and honestly, more revealing about where AI really belongs in medicine.

Dr. Sina Bari, a surgeon who leads AI healthcare initiatives, told me something that stuck with me. He had a patient arrive with a printout from Chat GPT claiming a medication carried a 45% risk of pulmonary embolism. The statistic was real. But it came from a study about that drug's impact on a tiny subgroup of tuberculosis patients. For his general patient? Completely irrelevant and deeply misleading. That's not a feature of the AI breaking. That's how it actually works. It pulls real information and serves it without context, confidence, or clinical judgment.

Yet Dr. Bari wasn't anti-AI. He was excited about what OpenAI announced. The shift he welcomed, though, was subtle but critical: formal privacy protections, message encryption, and data safeguards. Not because AI was new, but because patients were already using it, and regulation was coming either way.

This article cuts through the hype and examines where doctors actually see value in healthcare AI, where they see danger, and most importantly, where the real transformation is actually happening in clinical practice. It's not where you'd think.

TL; DR

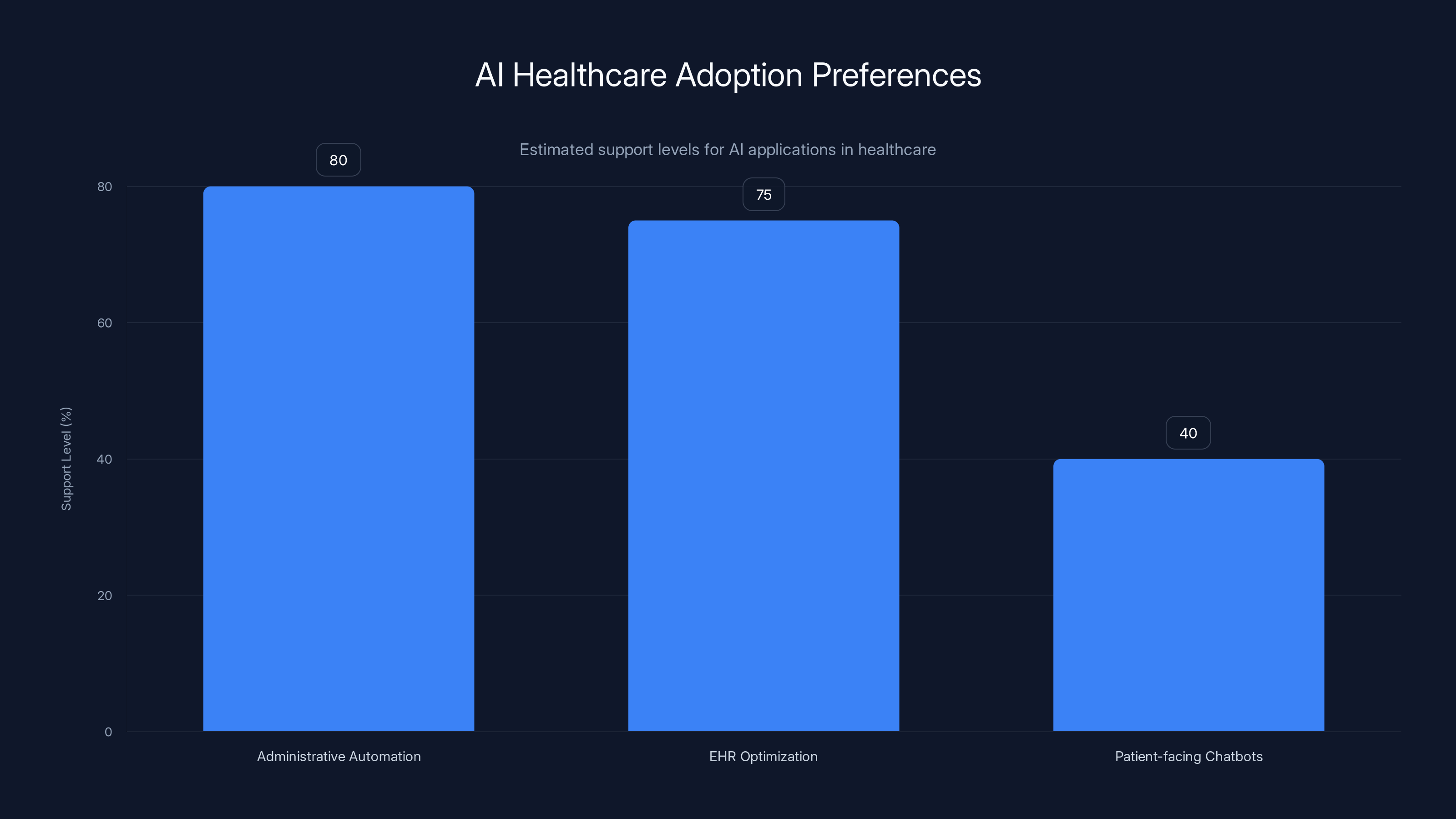

- AI healthcare adoption is fragmented: Doctors support administrative automation and EHR optimization far more than patient-facing chatbots.

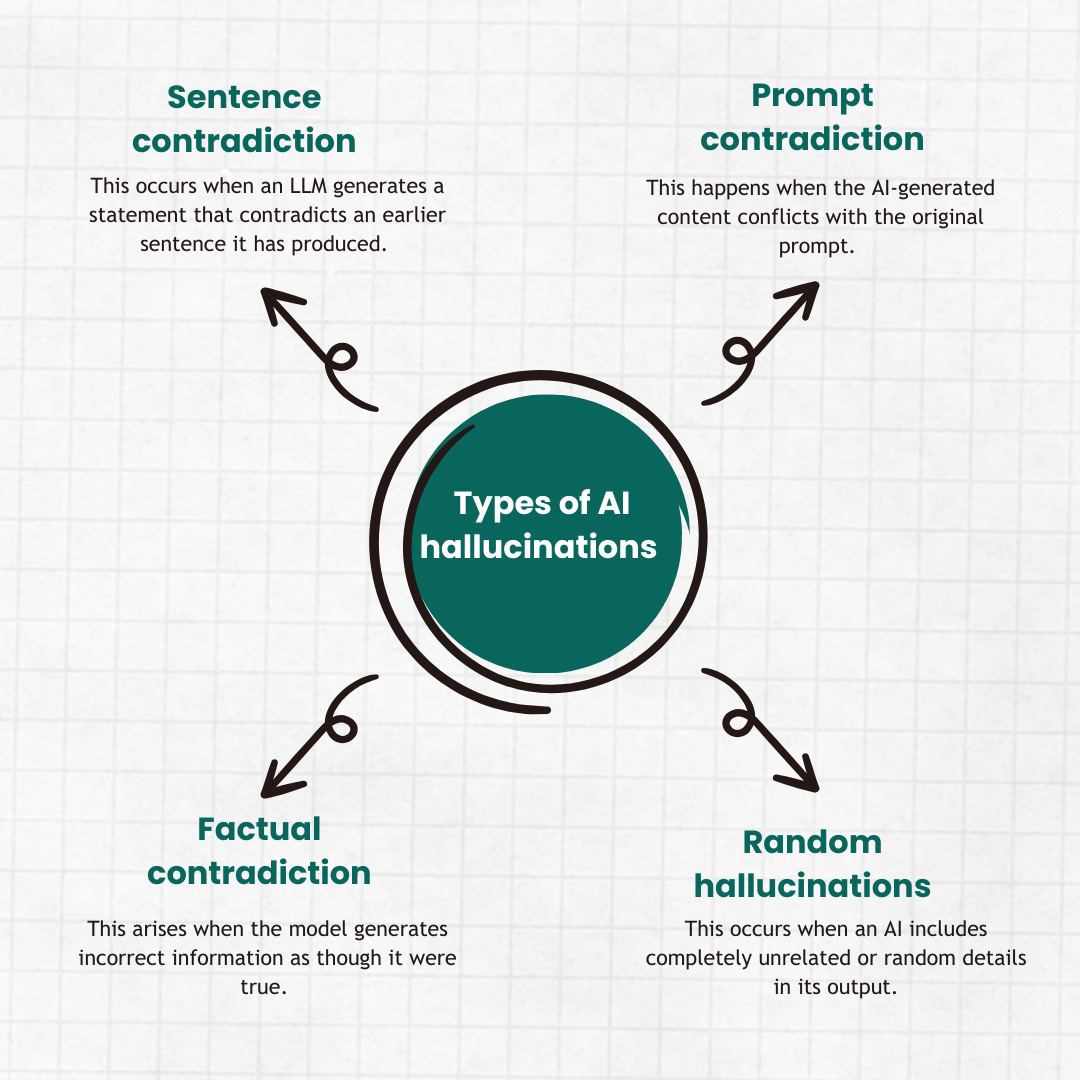

- Hallucinations remain the critical problem: Even advanced models like GPT-5 show higher factual inconsistency rates than some competitors, creating liability and safety concerns.

- The access crisis drives urgency: Primary care wait times spanning 6+ months make even imperfect AI tools look attractive to patients with nowhere else to turn.

- Provider-side tools show real promise: Backend automation reducing prior authorization and documentation work could increase physician capacity by 20-30%.

- Privacy and liability are the actual bottlenecks: HIPAA compliance, data transfer protocols, and regulatory frameworks matter more than model capability right now.

- Bottom line: Healthcare AI's future lives in clinical workflows, not consumer chatbots.

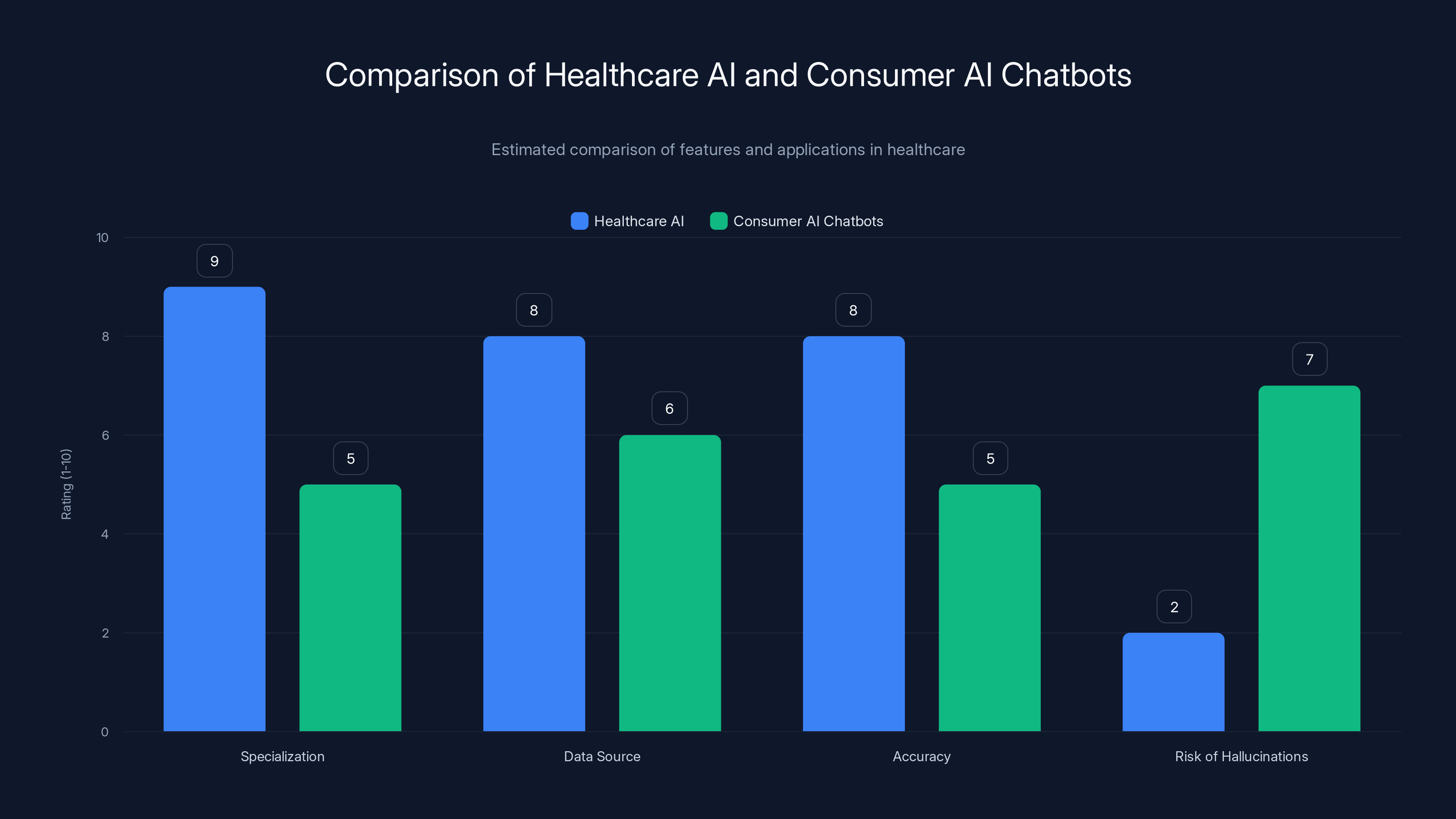

Healthcare AI systems are more specialized and accurate with lower risk of hallucinations compared to consumer AI chatbots. Estimated data.

The Hallucination Problem That Nobody's Fixing

Let's be direct about this. AI hallucinations in healthcare aren't inconveniences. They're potential death sentences. When an AI system confidently presents false medical information as fact, the consequences exist on a completely different scale than hallucinating the plot of a movie or getting someone's birthday wrong.

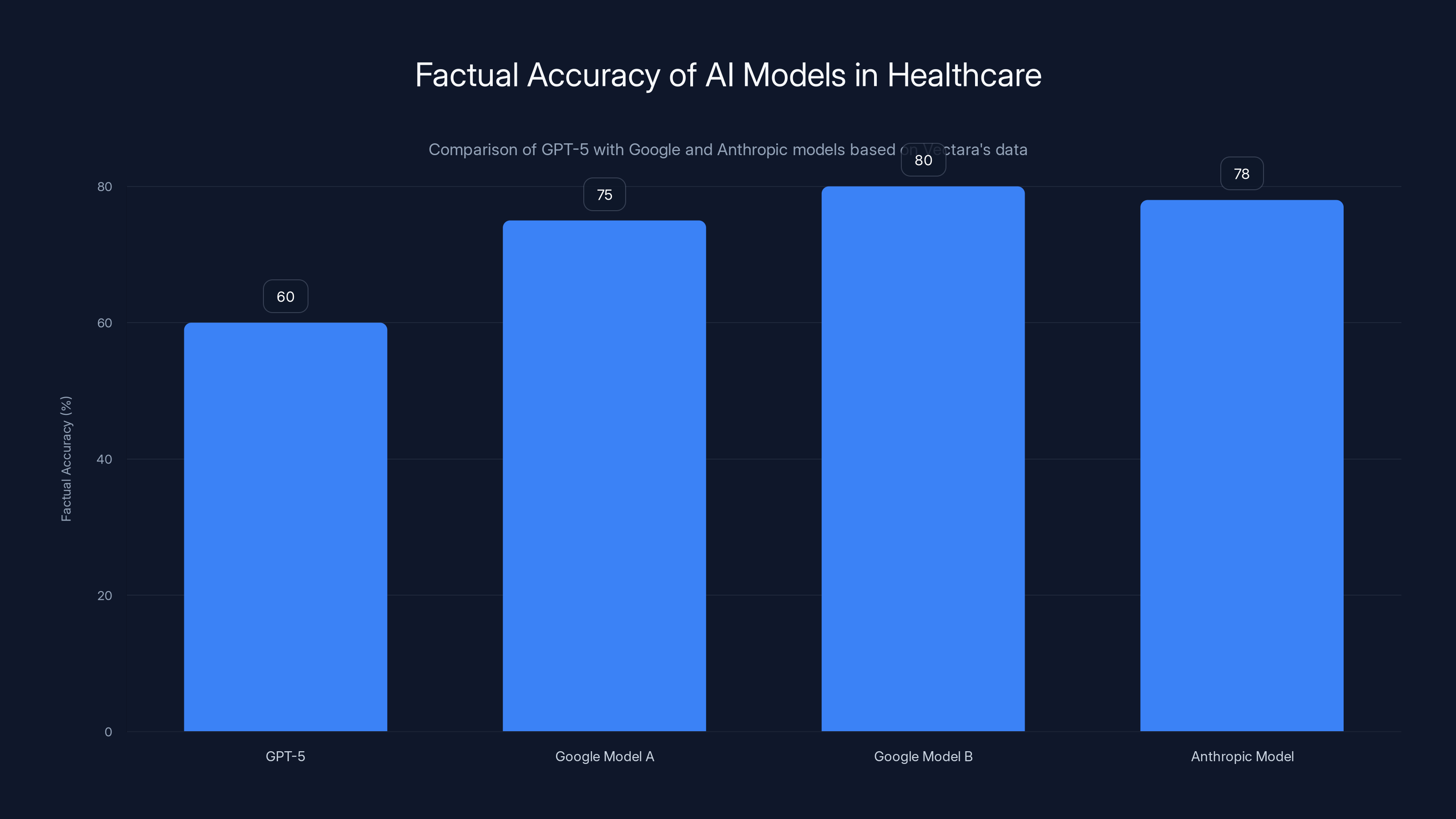

Vectara's Factual Consistency Evaluation Model released data showing that GPT-5 actually performs worse on factual accuracy than several Google and Anthropic models. Let that sink in. The newest, most hyped model from OpenAI has a documented problem with factual hallucinations that researchers can measure. This isn't speculation. This is benchmarked, testable reality.

What makes this worse is the confidence with which models present false information. An AI won't hedge. It won't say, "I'm not entirely sure, and you should verify this with a medical professional." It presents information in the same authoritative tone regardless of whether it's grounded in reality or entirely fabricated based on pattern-matching training data.

A cardiologist I spoke with tested this personally. She asked Chat GPT about drug interactions for a patient on a specific combination of medications. The response looked clinical, cited studies, and presented potential complications. When she verified it against her pharmacy database and medical literature, about 60% of the information was accurate. The other 40%? Either outdated, context-dependent in ways the model didn't capture, or completely made up. But it had looked legitimate. That's the real danger.

The medical community has started quantifying this risk. Healthcare systems are explicitly warning employees not to rely on general-purpose AI chatbots for clinical decisions. Some health systems are blocking access to Chat GPT on hospital networks entirely. Not because the technology is inherently evil, but because the liability is real and the accuracy guarantees don't exist.

Anthropically's Claude models show somewhat better factual consistency according to the same benchmarks, partly because the training process emphasizes constitutional AI principles. But "somewhat better" when we're talking about medical decisions still feels like cold comfort. The margin isn't wide enough to flip from "risky" to "safe."

GPT-5 shows lower factual accuracy compared to Google and Anthropic models, highlighting concerns in medical AI applications. Estimated data based on context.

Why 230 Million People Use AI for Health Advice (And Why That Matters)

The adoption number is almost incomprehensible. 230 million people weekly. That's not some niche use case. That's mainstream. That's your neighbor, your family member, your coworker asking Chat GPT about their symptoms before calling a doctor.

Why? Because the alternative is worse. In the American healthcare system, primary care access has basically collapsed. Dr. Nigam Shah, a medicine professor at Stanford and chief data scientist for Stanford Healthcare, put it bluntly: "Right now, you go to any health system and you want to meet the primary care doctor—the wait time will be three to six months."

Think about that. Six months to see a doctor for a non-emergency issue. In that reality, AI doesn't look like a supplement. It looks like the only option available.

Andrew Brackin, a partner at Gradient who invests in health tech, frames it correctly: Chat GPT health use became "one of the biggest use cases of Chat GPT." This wasn't accidental. It emerged because patients had no other choice. When you can't get an appointment, you ask the internet. When the internet can have a conversation, that becomes your doctor.

The implication is uncomfortable. We can't regulate AI out of healthcare because the void it's filling is actually deeper than the risks the AI creates. A patient waiting six months or talking to Chat GPT isn't choosing between perfect safety and risk. They're choosing between risk and nothing.

This is why OpenAI's announcement of Chat GPT Health with privacy protections actually made sense to physicians. It wasn't endorsement of AI replacing doctors. It was acknowledgment that patients are already doing this, regulation is inevitable, and the question isn't whether to allow it but how to make it less dangerous.

Dr. Bari's perspective captures this: "It is something that's already happening, so formalizing it so as to protect patient information and put some safeguards around it is going to make it all the more powerful for patients to use."

The cat is out of the bag. Now it's about harm reduction, not prevention.

The HIPAA Problem That's Bigger Than Technology

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention in the AI healthcare conversation. The technical problem of model accuracy is real, but it's not actually the primary problem that's stopping healthcare institutions from deploying AI at scale.

The primary problem is data. Specifically, patient data covered by HIPAA, sitting in hospital systems, potentially getting transferred to third parties who may or may not be compliant with those regulations.

Itai Schwartz, co-founder of MIND, a data loss prevention firm, flagged the exact issue: "All of a sudden there's medical data transferring from HIPAA-compliant organizations to non-HIPAA-compliant vendors. So I'm curious to see how the regulators would approach this."

When a patient uploads their medical records to Chat GPT Health or any similar service, even with privacy promises, the data is moving. It's leaving the secure confines of a HIPAA-covered healthcare provider and entering the infrastructure of a tech company that may or may not have the same compliance obligations.

The regulatory landscape here is murky. HIPAA technically covers healthcare providers and business associates. It doesn't necessarily cover end consumers uploading their own data to a service. But there's real ambiguity about who's responsible if that data gets breached, how it can be used, and what "de-identification" really means when you're dealing with AI systems that can potentially re-identify individuals through pattern analysis.

Healthcare institutions are moving slowly precisely because the legal risk is undefined. A hospital can't afford to get this wrong. A breach of patient data could result in fines, regulatory action, loss of certification, and catastrophic reputation damage. So even when the technology works, when the AI is accurate, when the solution genuinely improves workflows, adoption stalls because the legal framework hasn't caught up.

This is why some of the smartest healthcare AI deployment is happening within clinical systems rather than as consumer products. When the AI runs inside the hospital network, on hospital infrastructure, with hospital data, the HIPAA accountability is clear. It's the hospital's responsibility, and the hospital can control access, encryption, and retention policies.

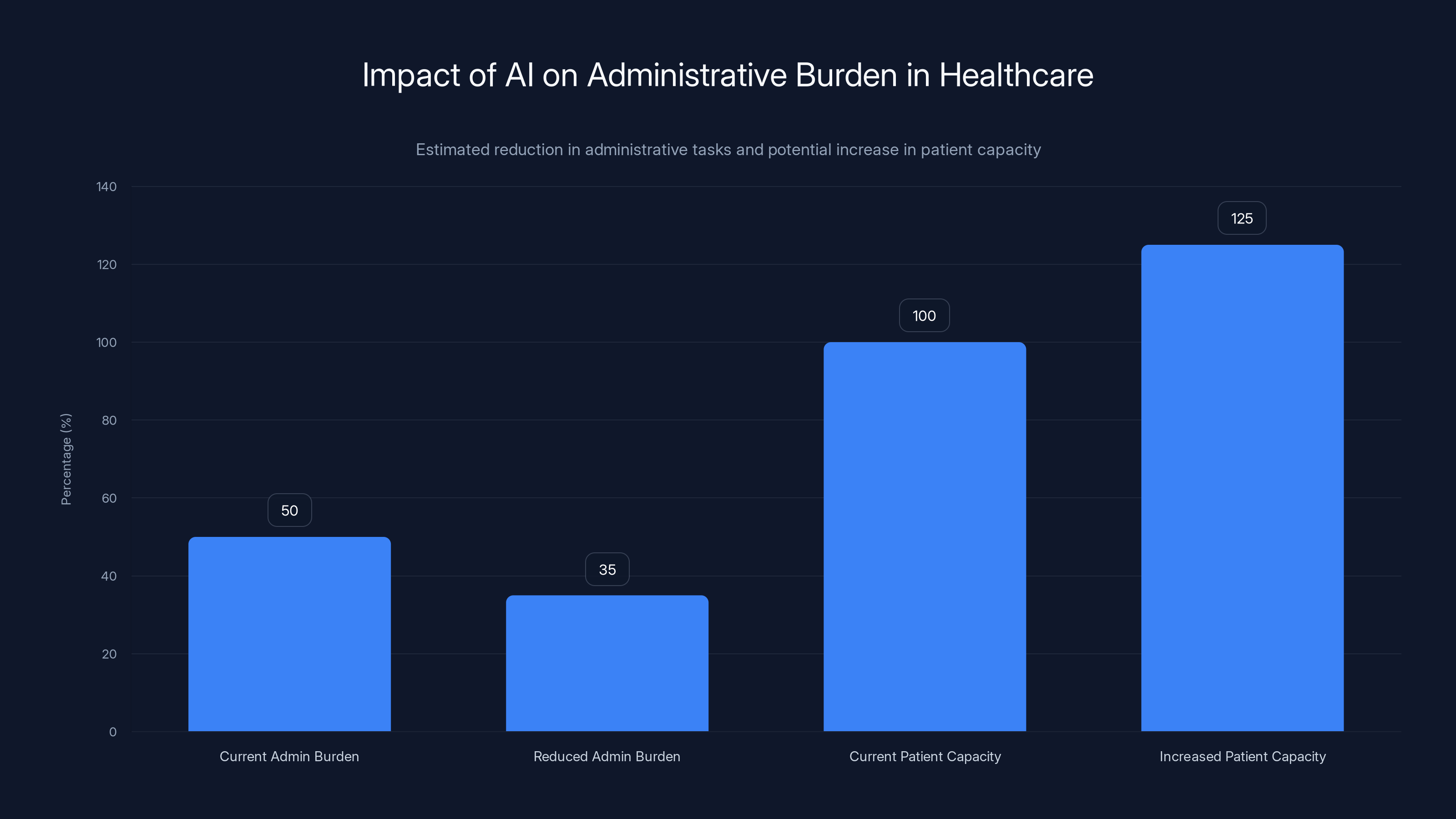

Estimated data shows that reducing administrative tasks by 30% could increase patient capacity by 25%, significantly improving healthcare efficiency.

Where AI Actually Works: Provider-Side Automation

Here's where the conversation shifts from problems to solutions. If patient-facing chatbots are legally messy and technically risky, where do doctors actually want AI?

The answer is almost boringly unglamorous: administration.

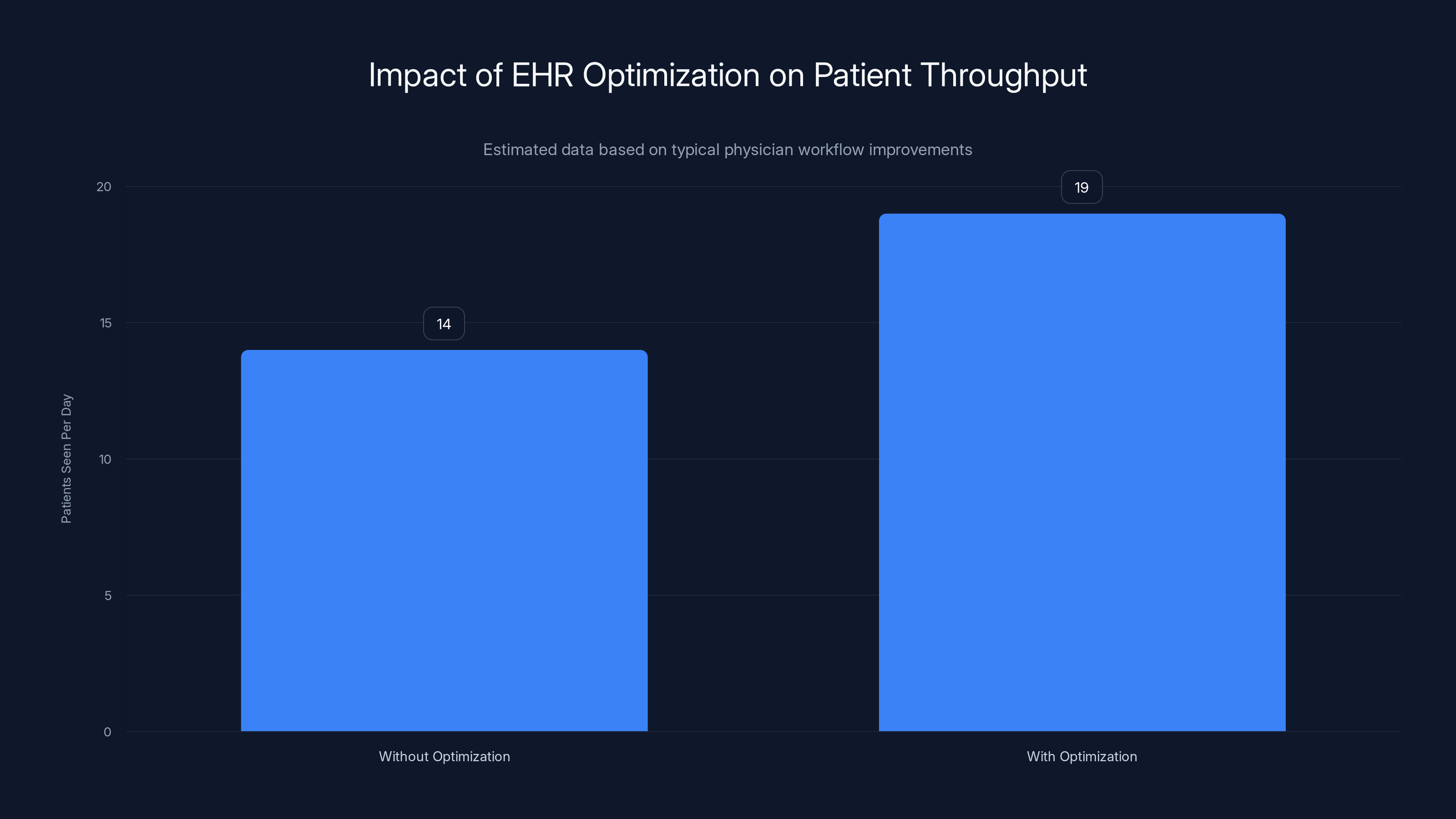

Medical journals have documented that administrative work consumes approximately 50% of a primary care physician's time. That's not an exaggeration. Physicians spend roughly half their workday on charting, documentation, prior authorizations, insurance coordination, and paperwork that has nothing to do with actually treating patients.

The calculation is simple: if you reduce administrative burden by 30%, you increase the number of patients a physician can see. If that happens across a healthcare system, you fundamentally change capacity without hiring more doctors (whose training takes 10+ years anyway).

Dr. Nigam Shah at Stanford is leading development of Chat EHR, software embedded directly into electronic health record systems. The approach is radically different from a consumer chatbot. Instead of replacing clinical judgment, it augments the specific task of information retrieval from massive, labyrinthine EHR databases.

Dr. Sneha Jain, an early tester, described the impact: "Making the electronic medical record more user friendly means physicians can spend less time scouring every nook and cranny of it for the information they need. Chat EHR can help them get that information up front so they can spend time on what matters—talking to patients and figuring out what's going on."

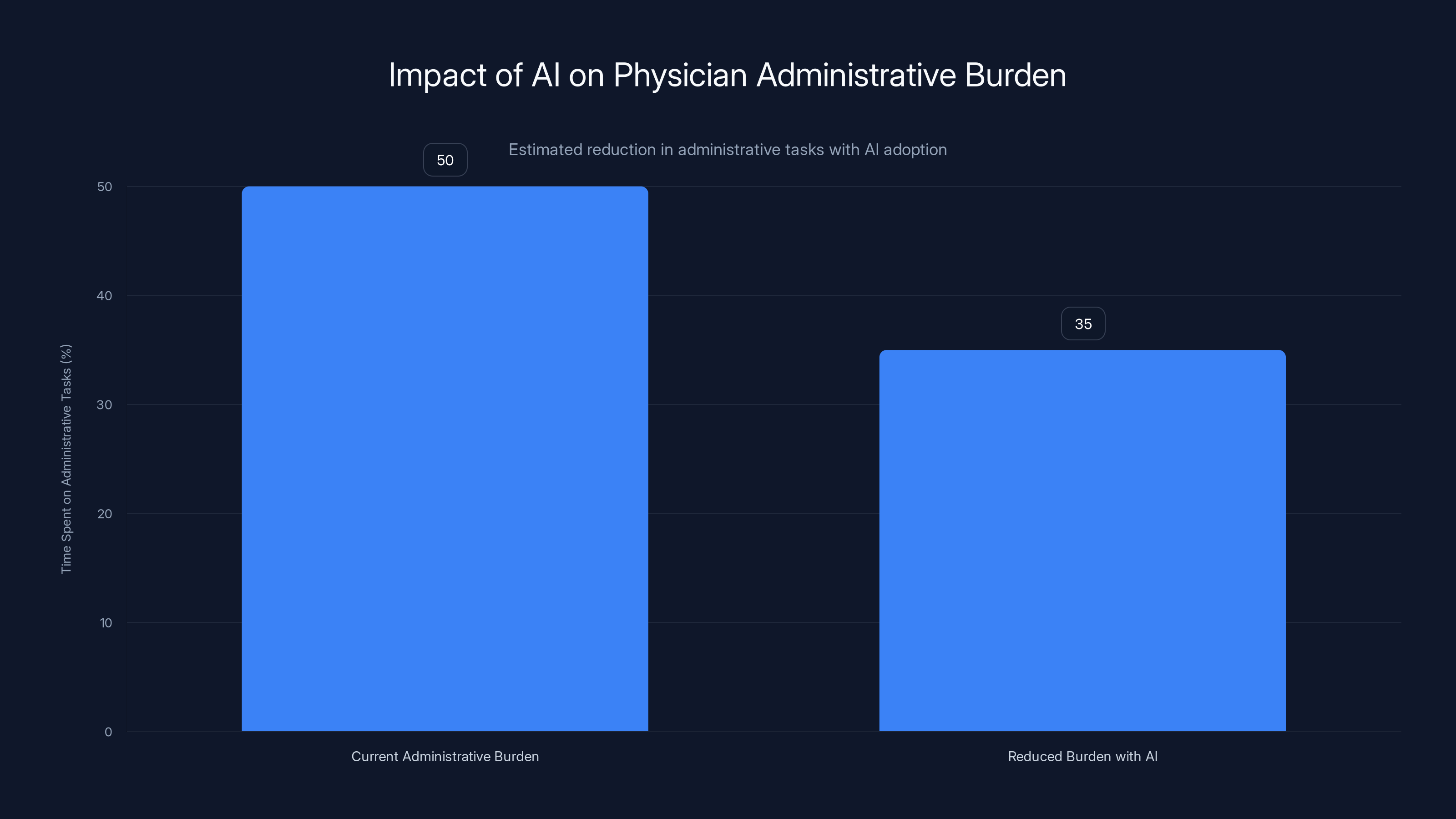

That's not sexy. There's no consumer app here. No viral moment. But it directly addresses the access problem. If a physician can see 25% more patients because they're not drowning in administrative work, that moves the needle on wait times.

Anthropically's Claude for Healthcare takes a similar approach. Rather than launching Claude as a consumer health chatbot competing with Chat GPT, Anthropic focused on clinician and insurer-side applications. Specifically, automating prior authorization requests.

Mike Krieger, Anthropic's chief product officer, put it in concrete terms at JP Morgan's Healthcare Conference: "Some of you see hundreds, thousands of these prior authorization cases a week. So imagine cutting twenty, thirty minutes out of each of them—it's a dramatic time savings."

Twenty to thirty minutes per authorization. If a large insurance company processes thousands weekly, that's thousands of physician and staff hours recovered. That's capacity, that's cost reduction, and crucially, that's automation of a task that genuinely benefits from AI's ability to parse complex rules and documentation.

The Prior Authorization Nightmare That AI Can Actually Solve

Let's zoom in on this because it's concrete enough to see how AI works when implemented well.

Prior authorization is the process where a healthcare provider requests insurance approval before delivering a treatment. It exists theoretically to ensure treatments are clinically appropriate and cost-effective. In practice, it's bureaucratic nightmare fuel.

A physician wants to prescribe a medication or order a scan. They submit paperwork to the insurance company. The insurance company's medical review team (often staffed by physicians, sometimes by non-clinicians reviewing algorithms) evaluates whether the treatment meets their coverage criteria. This can take days, sometimes weeks. The patient waits. The condition potentially worsens. The treatment is delayed or denied.

A healthcare system might have dozens of different insurance companies they work with. Each has different prior authorization requirements, different documentation standards, different approval timelines. A physician needs to know which insurer needs what documentation for which procedures. That knowledge is massive, constantly changing, and nearly impossible for individual clinicians to maintain.

Here's where AI becomes genuinely useful. You can train a model on the specific requirements of each insurance company's prior authorization process. You can give it templates, documentation standards, historical approval patterns. You can have it suggest which documentation to gather, fill in standard sections, and identify gaps.

The physician still makes the clinical decision. The model just handles the busy work of compliance with insurance requirements. When it works, it means authorization requests are submitted faster, more completely, and with fewer rejections due to missing information.

Claude's training actually helps here. Constitutional AI training emphasizes reasoning about rules and guidelines. Insurance prior authorization is essentially a rule-based system where accuracy genuinely matters. If the AI misinterprets coverage criteria, it could cause delays or denials. If it consistently gets it right, it saves massive amounts of time.

This is the model for healthcare AI that actually makes sense. Narrow task, clear evaluation criteria, human oversight retained, automation focused on paperwork rather than clinical judgment.

Doctors show higher support for administrative automation and EHR optimization compared to patient-facing chatbots. Estimated data.

Electronic Health Record Optimization: The Unsexy Revolution

If prior authorization automation is boring, EHR optimization is positively soporific. And yet it might be the most important application of AI in healthcare.

An electronic health record is supposed to be a comprehensive digital representation of a patient's medical history. In theory, a physician should be able to open an EHR and instantly understand a patient's medications, allergies, previous diagnoses, lab results, and imaging. In practice, EHR systems are bloated, poorly designed, and full of redundant information, missing data, and conflicting records.

A patient might have medications listed in three different places. Their allergy information might be incomplete or outdated. Previous test results might be filed in a way that's technically correct but practically unsearchable. A physician needs to spend 20-30 minutes just assembling accurate information before they can start thinking about diagnosis or treatment.

Chat EHR doesn't replace the EHR. It exists within it. A physician can ask in natural language: "Show me all cardiac medications this patient is on," or "When did they last have a lipid panel?" or "What's their current hypertension treatment?" The system pulls the correct information from across the entire record, resolving redundancies and conflicts.

This sounds like a small thing. In practice, it's transformative. A physician who spends 30 minutes assembling information can see maybe 12-15 patients per day. A physician who spends 10 minutes on information retrieval can see 18-20. That's not a small difference. That's the difference between a three-month wait and a one-month wait.

Moreover, EHR optimization has built-in accuracy checks. The information comes from the institution's own systems. It's documented. If the AI generates something wrong, it's immediately obvious because it contradicts the source data. That's not true for diagnosis chatbots, which have no built-in ground truth.

The Stanford team is designing Chat EHR not just to retrieve information, but to highlight what's relevant for the current interaction. If a patient comes in with chest pain, the system can surface cardiac risk factors, previous cardiac events, current cardiac medications, and recent cardiac imaging without the physician having to manually search for each data point.

Clinically, that's important because it reduces cognitive burden. A physician's brain has finite working memory. Every piece of information they have to manually search for and assemble is cognitive load. Reducing that load means the physician has more mental capacity for actual clinical reasoning.

This is where healthcare AI works well because it amplifies human capacity rather than trying to replace it. The AI isn't making decisions. It's making information available. The physician still thinks. They just think faster and with better information.

Documentation and Coding: The Hidden Time Sink

Here's another administrative area where AI makes genuine sense: medical documentation and coding.

After every patient visit, a physician needs to document what happened. What was the chief complaint? What were the vital signs? What were the findings from the physical examination? What's the assessment? What's the plan?

This documentation serves multiple purposes. It creates a legal record. It supports billing and coding (which determines insurance reimbursement). It communicates with other providers. It supports research and quality improvement. It's not optional. It's essential.

It's also time-consuming. A physician might spend 5-10 minutes seeing a patient and 10-15 minutes documenting the visit. That's a 2:1 documentation-to-clinical ratio that's actually typical in modern healthcare.

AI can help here by listening to or observing the visit and generating documentation drafts. The physician reviews and corrects, but the structure is already there. All the standard sections are populated. The AI has transcribed what was said. The physician just needs to review and verify.

This is different from having the AI fully generate documentation because the physician is actively involved in verification. The AI isn't making clinical judgments. It's transcribing and organizing information the physician provides.

Medical coding, the assignment of standardized codes to procedures and diagnoses for billing purposes, is even more amenable to AI. The coding rules are explicit. They're published. They're rule-based. An AI system trained on medical coding can learn these rules well and assist with coding assignment.

Again, the physician or professional coder is responsible for final accuracy. But the AI can suggest codes, flag missing documentation, and catch coding errors before claims are submitted. That saves time and reduces claim denials due to coding issues.

EHR optimization can increase the number of patients a physician sees from 14 to 19 per day, significantly reducing patient wait times. Estimated data.

The Tension Between Shareholder Value and Patient Care

Let's address the elephant in the room that the original article hinted at but didn't fully explore.

Healthcare has a fundamentally different structure than other industries. A doctor's primary obligation is to their patient. Their professional ethics, their licensing, their liability, all flow from that relationship. The Hippocratic Oath and its modern equivalents are about putting the patient first.

Tech companies, by contrast, are accountable to shareholders. They have a fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value. That's not a moral failing. It's legally required. But it creates a structural conflict in healthcare applications.

When OpenAI launches Chat GPT Health, it wants users. More users means more engagement, more data, more potential for monetization (whether through direct subscription or other channels). The incentive is to be useful, to be trusted, to be positioned as a reliable source of medical advice.

But the best thing for a patient might be "talk to a real doctor," which doesn't increase user engagement or retention. If Chat GPT Health is optimized for engagement, and talking to a real doctor is the best medical outcome, those objectives can diverge.

This isn't hypothetical. Meta's research on social media showed that content engagement and user wellbeing don't always align. Content that makes people angry generates more engagement. Content that's medically accurate might be less engaging than content that's emotionally resonant but medically questionable.

Healthcare AI faces the same structural issue. A patient using Chat GPT Health instead of seeking care is good for engagement. It's not good for the patient.

Dr. Shah's point about provider-side automation actually sidesteps this conflict. If AI increases physician capacity and enables physicians to see more patients, it aligns AI company success with healthcare outcomes. More patients seen is good for providers and patients. It doesn't generate as much direct consumer engagement, but it addresses the actual problem.

Anthropic's approach of focusing on insurer and provider applications rather than consumer products also mitigates this. The incentives are clearer. Reduce administrative work, reduce costs, improve efficiency. These are measurable and aligned with healthcare system goals.

Consumer-facing AI in healthcare will always carry this tension. The company wants engagement. The patient wants actual health improvement. Sometimes those align. Sometimes they don't.

Data Privacy in a Cloud Computing World

Let's talk about something that doesn't get enough attention: what happens to healthcare data when it touches cloud infrastructure.

OpenAI announced that Chat GPT Health messages won't be used for model training. That's good. But it doesn't address the reality of modern cloud computing. When data moves to the cloud, even with encryption, the cloud provider has some level of access.

A hospital uploads patient data to an AI vendor's cloud infrastructure. The data is encrypted. But encryption keys have to exist somewhere. The cloud provider's infrastructure can observe data patterns, access logs, computational usage. If there's a security breach, the data is exposed.

More insidiously, using cloud infrastructure for healthcare data creates a paper trail and dependencies. If a vendor changes their privacy policy, gets acquired, or experiences a breach, the hospital might have thousands or millions of patient records held by someone else's infrastructure.

For institutions that are risk-averse (and healthcare institutions should be, given the sensitivity of patient data), this is a major barrier. They'd prefer solutions that run on-premises, where data never leaves their network. But on-premises AI requires technical sophistication that many healthcare systems lack.

This creates a technological divide. Large, well-resourced health systems can afford to build or deploy AI locally and maintain strict data control. Smaller hospitals and clinics lack the resources and expertise. They'd need to trust cloud vendors or not use AI at all.

The regulatory environment is still sorting this out. HIPAA compliance is necessary but not sufficient. HIPAA is about reasonable safeguards. Healthcare institutions are increasingly asking for more than reasonable. They want guarantees.

AI can potentially reduce physicians' administrative workload by 30%, increasing their capacity to focus on patient care. Estimated data based on typical administrative burden.

State Medical Licensing and AI Accountability

Here's a question that should keep healthcare administrators awake at night: if an AI system gives bad medical advice, who's liable?

If a physician gives bad advice, they can lose their license. If a company's AI gives bad advice, the company faces potential liability, but there's no personal accountability for the engineers or company leadership in the way there is for physicians.

Moreover, physician licensing is designed to ensure a baseline of competence. A physician has completed medical school, residency, board certification. They've demonstrated knowledge and passed exams. An AI system has no such credential. There's no process to certify that an AI meets minimum medical standards.

State medical boards are only beginning to grapple with this. Some states have proposed requiring that AI used in patient care be approved or registered with the state medical board. Others are considering making it illegal to use unapproved AI for diagnosis.

But here's the gap: approval by whom? Using what standards? How do you evaluate an AI system when it's constantly being updated and fine-tuned? A physician's competence is evaluated once and remains documented. An AI model can be updated, retrained, or changed without public notice.

This regulatory question is genuinely unsolved. It's not a matter of technology catching up. It's a matter of governance structures that are designed for individual professionals needing to figure out how to apply to software systems.

The Future is Narrowly Scoped, Clinician-Controlled AI

If I had to predict where healthcare AI actually succeeds in the next 5-10 years, it wouldn't be in consumer chatbots. It would be in boring, specific, clinician-controlled applications.

Prior authorization automation. Done. The ROI is clear. The risks are manageable. The benefits are measurable.

EHR optimization and information retrieval. Definitely. The worst that happens is the AI gets information wrong, and the physician immediately sees the contradiction in the source data.

Documentation assistance, where the AI generates drafts that physicians review. Probably. The key is the review step—it keeps accountability with the human.

Medical coding assistance. Yes, for the same reasons.

Diagnosis support tools that highlight relevant information from patient records, flag potential drug interactions, or raise red flags based on lab results. Maybe, but only if they're presented as decision support, not decision replacement, and only with strong explainability about why the system flagged something.

Fulltime AI diagnosticians or therapists replacing human providers. Unlikely in the near term, and requiring fundamentally different liability and accountability structures if it ever happens.

Consumer health chatbots as primary medical advice sources. Only if there's a major regulatory framework shift and the accuracy guarantees improve dramatically.

The pattern is clear: AI works in healthcare when it's narrowly scoped, when it augments rather than replaces human judgment, and when the human professional retains full accountability.

That's less exciting than a general-purpose medical chatbot. It's also much more likely to actually improve healthcare.

The Economic Model Problem

Here's a question that's often overlooked: how does healthcare AI get funded and deployed?

AI companies want to sell to healthcare. But healthcare is fragmented, risk-averse, and price-sensitive. Large health systems are bureaucratic and slow to adopt. Small clinics lack budgets for new technology.

Some AI vendors are focusing on healthcare because the willingness to pay is high. Healthcare systems will spend significant money on solutions that save physician time or reduce administrative work. But selling into healthcare is slow and expensive.

Other vendors see healthcare as a secondhand use case. Anthropic develops Claude for general purposes, then applies it to healthcare. OpenAI does the same with Chat GPT. These are companies with massive capital backing large enough to absorb slow healthcare adoption cycles.

Smaller AI startups focused specifically on healthcare need more capital and patience than companies building for other verticals. They need venture funding, and VCs want returns faster than healthcare typically enables.

This means the most sophisticated healthcare AI tools are likely to come from large AI companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google, with their massive capital reserves. Or from specialized healthcare IT companies with existing relationships to health systems and the revenue base to support long sales cycles.

The economic structure shapes what gets built. Consumer-facing tools are cheaper to distribute. Enterprise tools to health systems require sales teams and customization. That affects which solutions get funded and how aggressively they're marketed.

Privacy-Preserving AI in Healthcare: The Frontier

One genuinely promising area is privacy-preserving machine learning. The basic idea is that you can train or run AI models on healthcare data without the company running the AI ever seeing the raw data.

Federated learning, for example, keeps data at hospitals while training happens on hospital infrastructure. The central server only gets model updates, not actual data. Differential privacy techniques add statistical noise to datasets so individual records can't be re-identified. Homomorphic encryption allows computation on encrypted data without decryption.

These techniques address the core privacy problem. Data never leaves the hospital. The AI company doesn't see patient information. The hospital retains control.

But these approaches come with trade-offs. Federated learning is computationally expensive. Differential privacy reduces model accuracy. Homomorphic encryption is slow. They work, but they're not as efficient as traditional approaches.

As these techniques mature and hardware improves, they could enable healthcare AI deployment that satisfies both privacy concerns and regulatory requirements. But they're not there yet for large-scale deployment.

Research institutions like Stanford are investing in this area. Companies are starting to offer privacy-preserving AI tools. But it's still early. Most deployed healthcare AI still relies on traditional cloud infrastructure with privacy promises rather than cryptographic guarantees.

Regulatory Expectations: What's Coming

Governments are starting to move on healthcare AI regulation. The European Union's AI Act, for example, classifies medical AI as high-risk, requiring significant documentation, testing, and monitoring.

The FDA has started issuing guidance on clinical decision support software. The FTC has been investigating healthcare AI companies for deceptive claims.

What's coming, probably, is:

-

Mandatory AI registries: Healthcare systems will need to document which AI tools they're using, for what purposes, and their performance metrics.

-

Validation requirements: AI tools will need to demonstrate that they work before deployment, not just that they have good intentions.

-

Transparency and explainability standards: AI systems will need to explain why they made recommendations in ways that clinicians can understand and evaluate.

-

Liability clarification: Rules about who's responsible when AI systems fail or provide bad information.

-

Data governance standards: Explicit rules about healthcare data moving to cloud infrastructure and how it's protected.

These regulations will slow adoption. Companies will need to invest in compliance and validation. But they'll also create trust. Clinicians need to know that the AI they're using has been evaluated and meets standards.

Regulation is often portrayed as the enemy of innovation. In healthcare, regulation might be necessary for innovation to actually be adopted at scale. Clinicians and healthcare administrators need confidence before they deploy mission-critical AI. Regulatory frameworks can provide that confidence.

The Path Forward: Unburdening Physicians

If there's a clear opportunity for healthcare AI, it's addressing the administrative burden that's suffocating the profession.

A physician trained for 10+ years and paid six figures spends roughly 50% of their time on administrative work that requires no medical knowledge. From an economic perspective, that's absurd. From a patient care perspective, that's devastating. When physicians spend half their time on paperwork instead of patients, the system has fewer appointments available, wait times extend, and patients can't get care.

AI can genuinely help here. Not by replacing clinical judgment, but by automating the parts of medicine that are essentially data processing and rule application. Documentation, coding, prior authorization, information retrieval from EHRs—these are tasks where AI can add value without replacing expertise.

The business case is clear. If AI reduces administrative burden by 30%, healthcare systems get the equivalent of 30% more physician capacity without hiring additional physicians. That addresses access. That improves wait times. That reduces the desperation that drives patients to ask Chat GPT about their symptoms.

That's the real opportunity. Not replacing doctors with AI, but freeing doctors from administrative work so they can actually practice medicine.

The Missing Piece: Physician Education on AI

Something that's barely discussed in healthcare AI circles is that physicians largely don't know how to use or evaluate AI tools.

Most physicians didn't study AI in medical school. They didn't study statistics deeply. They may not understand how machine learning models work, what hallucinations are, or how to evaluate whether an AI system is actually reliable.

When a physician sees a new AI tool, they're relying on marketing claims and their own intuition. If the tool looks polished and feels helpful, they might adopt it without really understanding what could go wrong.

Healthcare institutions need to invest in educating physicians about AI. What are AI's capabilities and limitations? How do you evaluate an AI tool? What questions should you ask vendors? How do you spot hallucinations? When is AI appropriate for a task and when isn't it?

This isn't happening at scale. Medical schools aren't teaching it widely. Health systems aren't providing training. Physicians are expected to figure it out.

Meanwhile, AI vendors are happy to fill the knowledge gap with marketing. Physicians end up with incomplete understanding, leading to both over-confidence in some tools and under-confidence in others that actually work.

Healthcare systems that invest in physician AI literacy will make better adoption decisions. Physicians who understand AI limitations will deploy tools more appropriately. That benefits patient care.

The Long View: Integration Over Replacement

The fundamental question facing healthcare AI isn't whether AI belongs in medicine. It clearly does. The question is how to integrate AI in ways that improve care, respect patient autonomy, maintain professional accountability, and don't break under regulatory scrutiny.

The answer isn't universal. Patient-facing diagnosis chatbots are probably not the right model, at least not now. Provider-side administrative automation is clearly right. Decision support tools have potential if designed and implemented properly. Consumer tools for health information (not diagnosis, but general education) might make sense with appropriate disclaimers.

What's needed is thoughtful, incremental deployment with constant evaluation. Implement tools in narrow, well-defined use cases. Measure their impact rigorously. Share failures and successes transparently. Adjust as you learn.

That's slower than the "move fast and break things" approach that made tech companies successful. But healthcare can't afford to break things. The cost of failure is people's health.

The future of healthcare AI is probably not a single revolutionary change. It's thousands of incremental improvements, each carefully evaluated, each adding small amounts of efficiency and capacity. That compounds over time into genuinely better healthcare.

It's not as sexy as a Chat GPT Health launch. But it's more likely to actually improve medicine.

FAQ

What is healthcare AI and how does it differ from consumer AI chatbots?

Healthcare AI refers to artificial intelligence systems designed specifically for medical applications, while consumer AI chatbots are general-purpose models adapted for health questions. Healthcare AI can be specialized for narrow clinical tasks—like analyzing medical images, generating documentation summaries, or automating prior authorization. Consumer chatbots like Chat GPT are trained on broad internet data and apply general knowledge to health questions, which can lead to hallucinations and context-stripping that makes accurate medical information dangerously irrelevant.

Why do hallucinations matter more in healthcare than other AI applications?

Hallucinations in healthcare carry life-or-death consequences. When an AI confidently presents false medical information—like fabricating drug interaction risks or overstating side effect probabilities—patients might make dangerous decisions. Unlike hallucinations about movie plots or historical facts, medical hallucinations can directly cause harm through missed diagnoses, inappropriate treatments, or avoidable complications.

What is prior authorization and why is AI particularly suited for automating it?

Prior authorization is the process where healthcare providers request insurance company approval before delivering treatments. It's time-consuming, rule-based work that requires parsing complex insurance policies and documentation requirements. AI is well-suited for this because the rules are explicit and published, the task is purely administrative (not involving clinical judgment), and automation directly saves physician and staff time on a process that slows patient care.

How does Chat EHR work differently from Chat GPT Health?

Chat EHR is designed to operate within hospital electronic health record systems and pulls information from institutional data, with built-in verification against source records. Chat GPT Health is a consumer product that synthesizes general medical knowledge and user-provided health information. Chat EHR's information is verifiable and linked to specific patient records, while Chat GPT Health has no ground truth to reference and no institutional context.

What are the main privacy concerns with uploading medical data to AI platforms?

When patients upload medical records to third-party AI platforms, data leaves HIPAA-covered healthcare institutions and enters cloud infrastructure where privacy guarantees are contractual rather than structural. Data encryption and no-training promises don't address risks like infrastructure breaches, regulatory changes by vendors, or acquisition by companies with different privacy policies. The patient loses institutional control over their data.

Why do healthcare institutions move slowly on AI adoption despite potential benefits?

Healthcare systems face massive liability exposure from AI failures, operate under strict regulatory requirements (HIPAA, state licensing laws), and lack clear legal frameworks for accountability when AI systems fail. The risk of patient harm, regulatory penalties, and loss of institutional certification outweighs the efficiency gains for most implementations, creating justified caution even when the technology works well.

What does evidence show about AI accuracy in medical decisions?

Research like Vectara's evaluation shows that even advanced models like GPT-5 have measurable factual consistency problems. Some Anthropic and Google models perform better on medical factuality benchmarks, but "better" still means error rates that would be unacceptable in clinical practice. No current general-purpose AI achieves the accuracy standards physicians require for patient care.

Is there a way to use healthcare data with AI while preserving privacy?

Yes, privacy-preserving techniques like federated learning (training on local hospital infrastructure without centralizing data), differential privacy (adding statistical noise to prevent individual re-identification), and homomorphic encryption (computing on encrypted data) all exist. But these come with trade-offs: they're computationally expensive, reduce model accuracy, or slow inference. They're promising but not yet mature enough for widespread healthcare deployment.

What should healthcare organizations prioritize when implementing healthcare AI?

Focus on narrow, well-defined administrative tasks where the risk is low and ROI is clear: documentation assistance, medical coding support, prior authorization automation, and EHR information retrieval. These improve physician capacity directly, don't require clinical judgment replacement, and have measurable impact. Avoid broad diagnostic or treatment tools until regulatory frameworks and AI accuracy improve significantly.

How will healthcare AI regulation affect current products and implementations?

Expect increasingly strict requirements for validation, documentation, explainability, and liability clarity. The FDA, FTC, and state medical boards are all moving toward requiring AI systems to be registered, validated before use, and transparent about their reasoning. This will slow deployment but increase trustworthiness. Companies unwilling to invest in compliance will exit the healthcare market.

Conclusion: AI in Healthcare Is Real, But Maybe Not How You Think

The healthcare AI story that's getting headlines is about patient-facing chatbots and consumer tools. OpenAI and Anthropic launching health products makes for good press coverage and drives engagement metrics. But that's not actually where the meaningful healthcare transformation is happening.

The real transformation is happening in clinical back offices. It's unglamorous. It's prior authorization getting processed faster because AI handles the rule-based complexity. It's physicians spending five minutes instead of fifteen minutes finding patient information in their EHR. It's documentation getting drafted and reviewed instead of written from scratch.

These changes don't make headlines. They don't go viral. But they compound. If every physician in a large health system saves 30 minutes daily on administrative work, that adds up to thousands of additional patient appointments annually. That moves wait times from six months to three months. That's actual access improvement.

The constraint on healthcare isn't technology anymore. It's not that we don't have AI. We do. It's that we haven't figured out how to deploy it responsibly in a highly regulated, risk-sensitive domain where failures have human consequences.

That's not a technology problem. It's a governance problem. It requires regulatory frameworks that haven't been written. It requires liability standards that haven't been settled. It requires physician education that hasn't happened. It requires trust that hasn't been earned.

We will get healthcare AI. It will improve outcomes. But probably not through the path that venture capital funding and tech company ambition are currently pursuing. Probably through steady, incremental deployment in clinical workflows, focused on freeing physicians from administrative burden rather than replacing their judgment.

The opportunity is real. The timeline is probably longer than the AI community wants to admit. And the winner might not be the company with the fanciest consumer app, but the one that actually solves physicians' daily problems in ways that regulators can approve and patients can trust.

That's the unsexy truth. And it's likely exactly what healthcare actually needs.

Key Takeaways

- 230 million people weekly use AI chatbots for health advice, driven by 3-6 month primary care wait times, not choice preference for AI over doctors.

- Provider-side administrative AI (prior authorization, EHR optimization, documentation) shows clear ROI and doctor support, while consumer health chatbots face hallucination and liability issues.

- GPT-5 shows higher factual consistency problems than some Google and Anthropic models; even improved accuracy remains insufficient for clinical decision-making without human oversight.

- HIPAA compliance and data privacy concerns create institutional barriers to cloud-based healthcare AI adoption that outweigh technical capabilities for many health systems.

- Physician administrative burden consuming 50% of workday is the real opportunity for AI: automating bureaucracy could increase clinical capacity by 25-30% without hiring more doctors.

Related Articles

- Claude for Healthcare vs ChatGPT Health: The AI Medical Assistant Battle [2025]

- 33 Top Health & Wellness Startups from Disrupt Battlefield [2025]

- Google Removes AI Overviews for Medical Queries: What It Means [2025]

- CES 2026 Bodily Fluids Health Tech: The Metabolism Tracking Revolution [2025]

- ChatGPT Health & Medical Data Privacy: Why I'm Still Skeptical [2025]

- ChatGPT Health: How AI is Reshaping Medical Conversations [2025]

![AI in Healthcare: Why Doctors Trust Some Tools More Than Chatbots [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-in-healthcare-why-doctors-trust-some-tools-more-than-chat/image-1-1768331358170.jpg)