AI Music Generation: History's Biggest Tech Panic or Real Threat? [2025]

There's this thing that happens every time a major technology disrupts an industry: panic. Real, visceral panic.

In 1877, when Edison's phonograph could suddenly capture and replay human voices, orchestras thought the jig was up. Concert halls would empty. Why pay for live musicians when you could crank a mechanical device and hear Enrico Caruso from your living room?

Then came the synthesizer in the 1960s. Robert Moog and Don Buchla weren't trying to destroy music. They were just building tools that let people make sounds that didn't exist before. But the musical establishment treated them like weapons. "Synthesizers are soulless," musicians complained. "Real music comes from real instruments played by real people."

Yet here's what actually happened: synthesizers didn't kill live music. They transformed it. Kraftwerk, Vangelis, and Herbie Hancock didn't end music careers—they expanded what music could be. Concert tickets still sold. Artists still got paid. The industry evolved.

Now we're doing it all over again with AI music generation. And just like last time, the panic is real. But is it justified?

The answer is more nuanced than either the "AI will replace all musicians" crowd or the "this is just another tool" optimists want to admit. AI music generation is genuinely different from what came before—not because it's revolutionary in a good way, but because it's disruptive in ways synthesizers never were. And understanding where the real threat lies requires looking at what actually changed, not just comparing it to synthesizers.

TL; DR

- The panic is real but also familiar: Musicians have feared new technology for 150+ years, yet live music thrives

- AI music is different: Unlike synthesizers that required skill to master, AI can generate passable music instantly with no expertise

- The real threat isn't replacement: It's devaluation, copyright confusion, and platform monopolies capturing artist work

- Synthesizers expanded the industry: AI is compressing it by flooding markets with cheap, low-quality content

- The question isn't "is AI okay?": It's "whose interests does this serve, and how do we structure it fairly?"

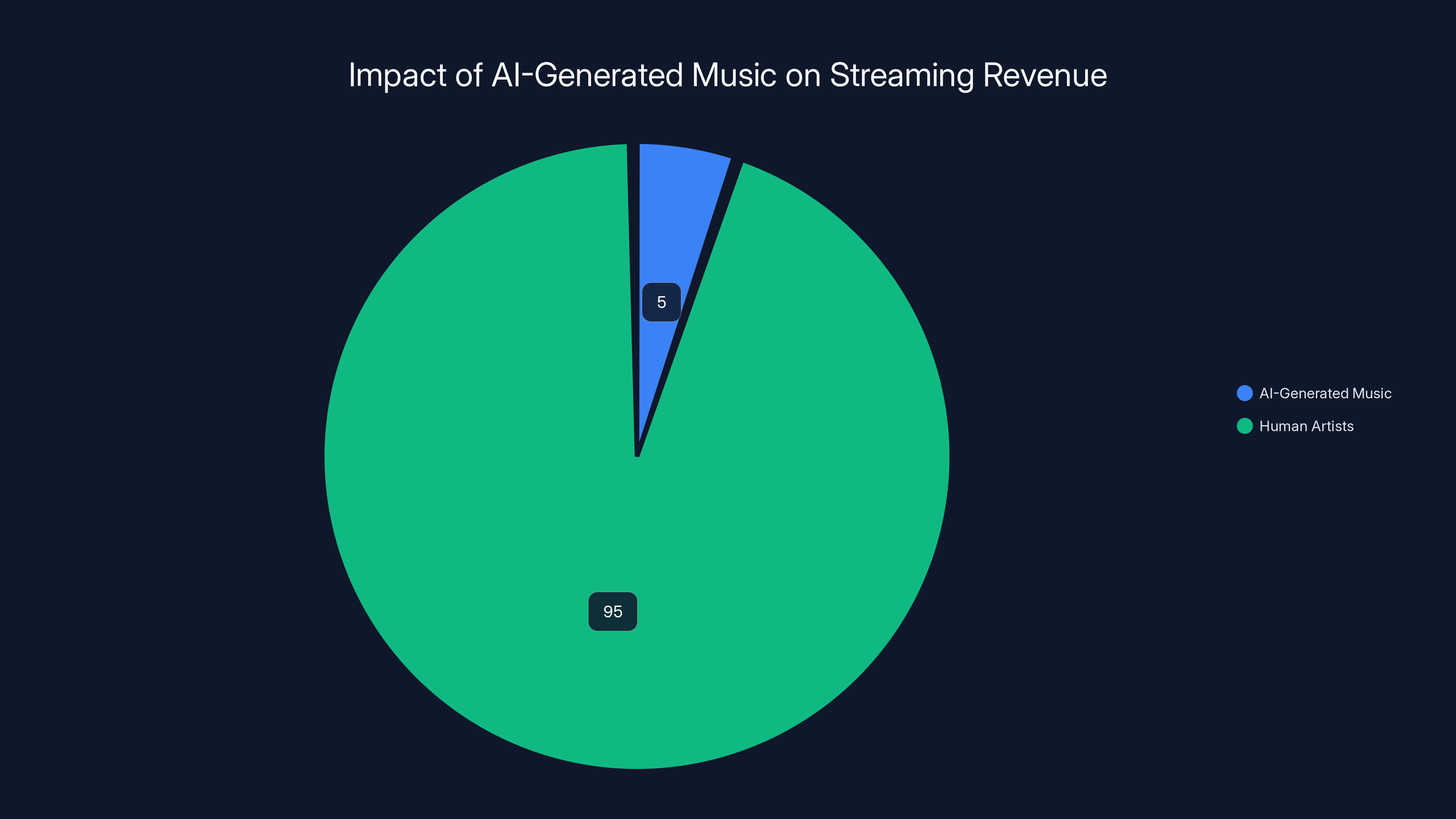

Estimated data shows AI-generated music capturing 5% of streaming revenue, reducing the share available to human artists.

Why Musicians Keep Panicking About Technology (And Why They Were Sometimes Right)

Let's start with the actual history, not the invented version.

When recorded music became mainstream in the early 1900s, live orchestras really did start losing gigs. Sheet music sales plummeted. Radio stations—which could broadcast recordings for free—killed many small live venues. The Musicians Union fought back hard. James Petrillo, the union's president in the 1940s, negotiated deals to protect session musicians. He even negotiated a "ban" on recordings for a year to pressure the industry to hire more musicians to make new records.

Were they panicking? Absolutely. Were they being irrational? Not entirely. Recorded music genuinely did displace live musicians from certain work. But here's the part that matters: the industry adapted. Movies needed orchestral scores (someone had to write and record them). Radio needed content. New jobs emerged. The pie didn't stay the same size, but musicians found new ways to make a living.

The synthesizer panic followed the same pattern. In the 1970s, orchestra members legitimately worried about job losses. A synthesizer could mimic string sections, brass, woodwinds. Why hire an entire orchestra when Walter Carlos could recreate the sound of Tchaikovsky with a Moog?

But synthesizers didn't work that way in practice. They required serious skill, knowledge, and artistic intention. Playing a synthesizer was like learning an entirely new instrument. Most musicians still wanted the texture and nuance of acoustic instruments. The synthesizer became an addition to the toolkit, not a replacement.

The pattern was: new technology, panic, adaptation, expansion. But that pattern assumed something crucial—that the new technology still required skill, intentionality, and human creativity to use effectively.

AI music generation changes that equation fundamentally.

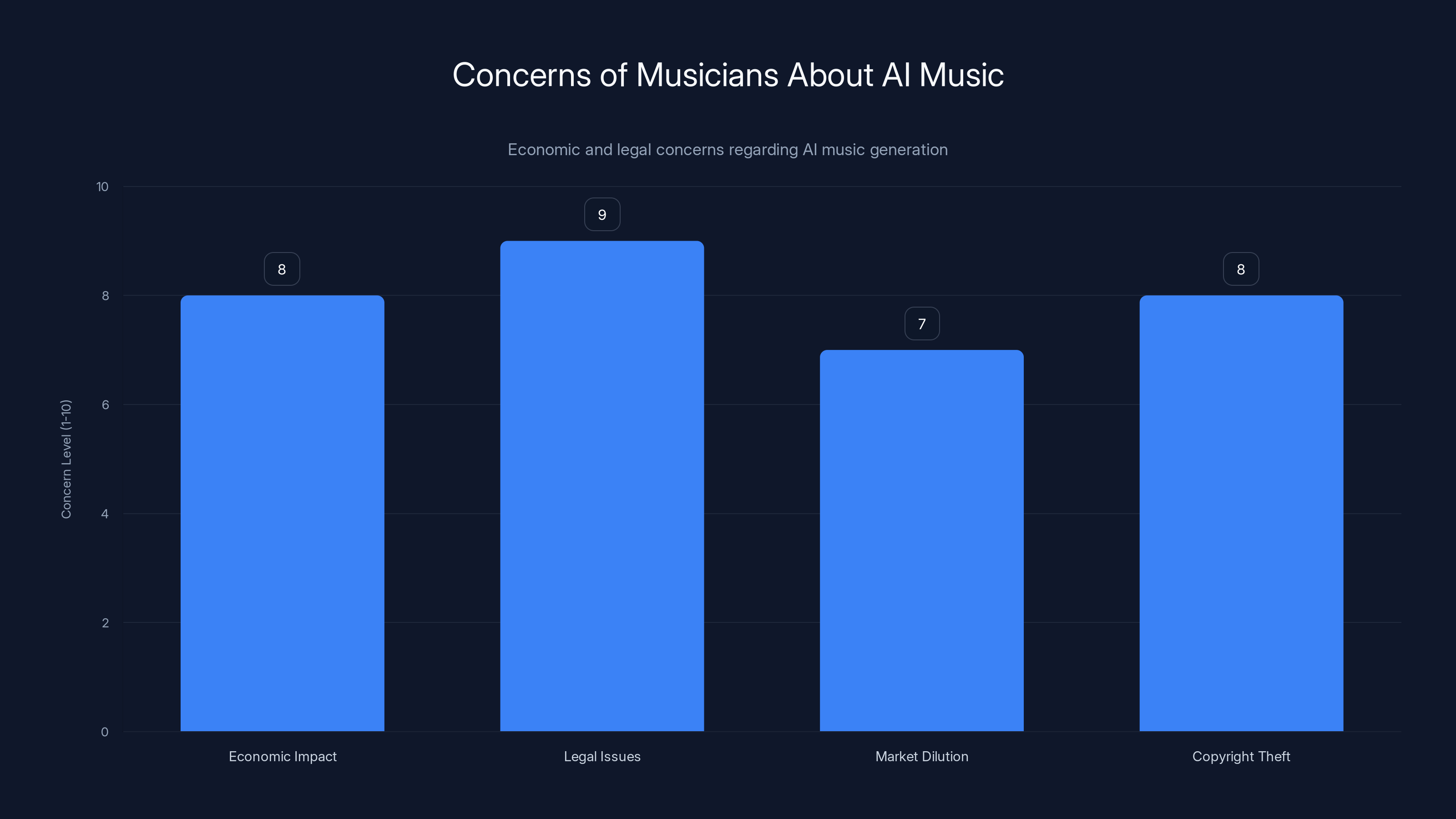

Musicians express high concern over AI music's economic impact, legal issues, and potential for market dilution and copyright theft. Estimated data based on common industry discussions.

What Makes AI Music Actually Different From Synthesizers

Here's where the comparison breaks down.

When you wanted to use a synthesizer, you had to:

- Learn the instrument (months to years)

- Understand music theory

- Develop a personal style

- Use it creatively to make something new

A synthesizer was a tool that amplified human skill. It didn't replace skill—it required it.

When you use Udio, Suno, or Open AI's Jukebox, you:

- Type a text prompt

- Click generate

- Get music

The skill barrier just vanished. That's not inherently bad—it's democratizing in some ways. But it's also fundamentally different from how previous "disruptive" instruments worked.

The synthesizer required the human to bring intention, taste, and skill. AI music generation lets the machine handle all three. You don't need to know music theory. You don't need to understand production. You don't need any particular artistic vision beyond "I want upbeat electronic pop about cats."

That's the real shift. Synthesizers made music-making harder but more possible. AI makes music-making frictionless but also valueless.

The Real Economic Threat (It's Not What You Think)

Here's where the panic gets justified—but for the wrong reasons.

Musicians aren't actually afraid that AI will make better music than them. That's a straw man. Almost every working musician who's heard AI-generated music recognizes it as obviously inferior. The concern isn't replacement. It's something more subtle and economically devastating: devaluation.

Consider You Tube. In the early days, musicians used You Tube to build audiences. A good music video could go viral, get a record deal, launch a career. You Tube was a platform for musicians to reach people.

But over time, You Tube became flooded with mediocre content. The algorithm optimizes for watch time, not quality. So creators learned to game the algorithm with thumbnails, titles, and clickbait rather than good music. The barrier to uploading means more competition for every musician trying to build an audience.

Now imagine that on steroids. Imagine a music streaming platform filled with millions of AI-generated songs, each one generic enough that nobody hates it, but interesting enough that some people listen to it. What happens to the song from an emerging artist competing against that?

Here's the economic mechanics:

Streaming pays per listen. Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music—they all have finite payout budgets. If 1 billion AI-generated songs collectively capture 5% of streams, that's money taken directly out of the pockets of human artists. Not because the AI music is better. Just because it exists and some people will listen to it.

That's the real threat. Not replacement. Dilution.

Second, there's the copyright problem. Most AI music models trained on massive datasets of existing music. Open AI trained on unlicensed music. Midjourney did the same with images. These companies extracted value from millions of artists without permission or compensation.

Some artists are filing lawsuits. Sarah Silverman sued Open AI, along with authors like Michael Chabon and John Grisham, claiming the company trained on their copyrighted work without permission. Similar lawsuits are coming for music.

But here's the real problem: the legal framework doesn't exist yet. Is it copyright infringement if an AI learns from patterns in music? Is it fair use? Nobody actually knows. While the courts figure it out, companies are already deploying these tools. The artists pay the cost. The companies capture the value. By the time courts settle it, the technology will be so entrenched that damages won't matter.

That's not panic. That's a legitimate concern about how power and money flow through the system.

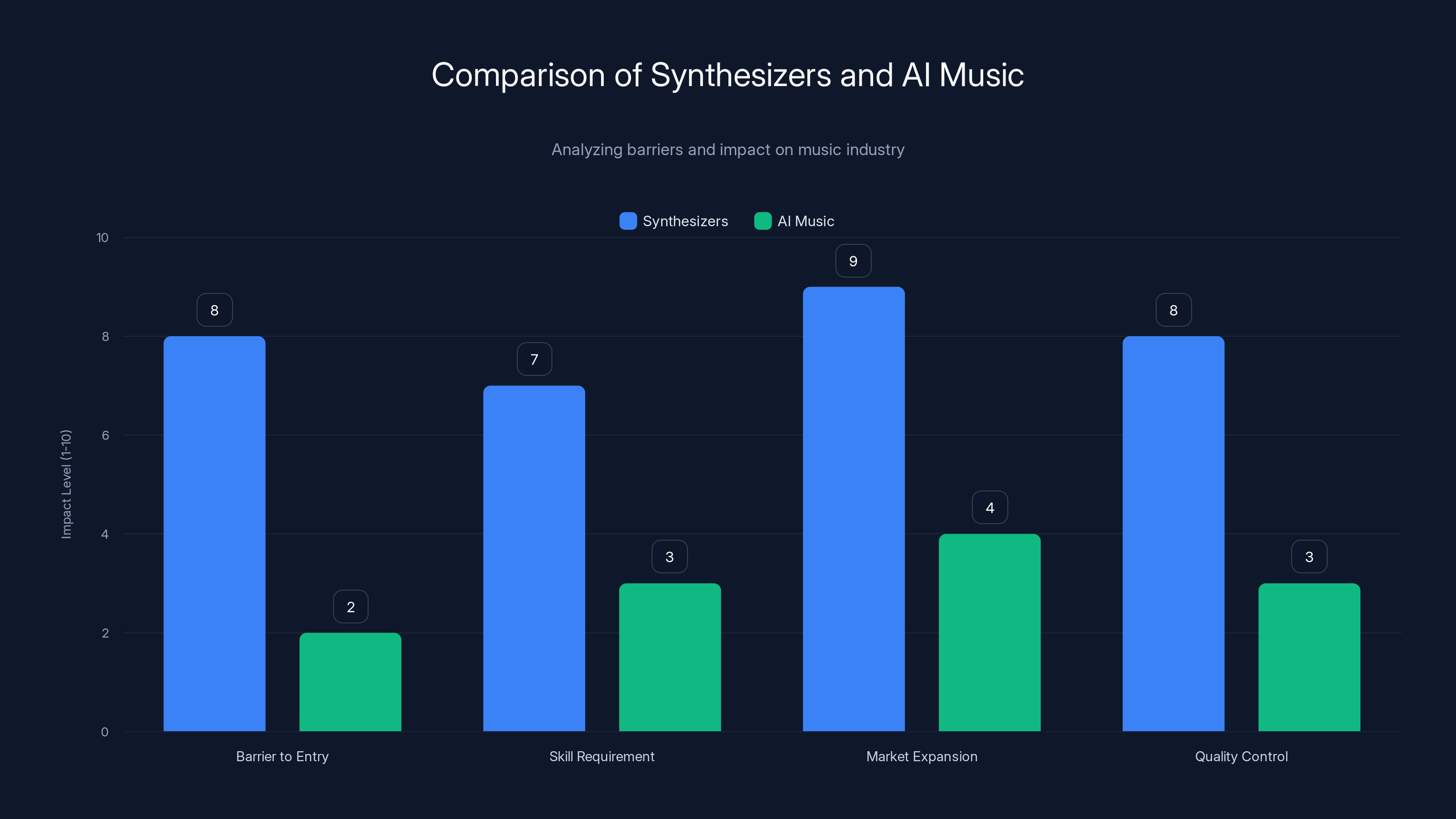

Synthesizers had higher barriers and skill requirements, leading to market expansion and quality control, unlike AI music which lowers entry barriers and dilutes existing genres. Estimated data.

Where AI Music Actually Helps (And It Does)

Let's be fair: AI music generation has real uses that don't destroy musicians.

Background music for content creators: You Tubers, podcasters, and small businesses need background music but can't afford licenses. AI-generated music is cheap and functional. Is it great? No. Is it better than silence or royalty strikes? Yes.

Rapid prototyping for composers: A film composer can generate variations on a theme to show a director, rather than spending hours at a piano trying different approaches. That's a tool that makes the composer more efficient, similar to how notation software helps.

Learning tool for students: Someone learning music production can see how AI structures a song, analyze the harmonic progressions, and understand production choices. That's genuinely educational.

Accessible creativity for people without training: Someone who can't afford piano lessons can hear what their song idea sounds like with AI. Not everything needs to be monetized or broadcast—sometimes making music is just fun.

Filling genuinely worthless slots: There's a category of "music" that has negative value—elevator background, hold music, royalty-free You Tube content nobody actually cares about. AI-generated music could handle this without displacing anyone.

The problem is distinguishing between these legitimate uses and the extractive ones. And right now, there's no guardrail. Distro Kid lets you upload AI-generated music to Spotify. No verification. No disclosure. Just dumping generic slop into the music ecosystem and splitting the payout with whatever user uploaded it.

So the question isn't whether AI music tools can be useful. They can. The question is whether the current implementation prioritizes utility or extraction.

Right now? It's extraction.

The Synthesizer Comparison Falls Apart Here

People defending AI music keep saying, "Synthesizers were feared too, and they turned out fine."

But there's a critical difference in how synthesizers and AI music were deployed.

Synthesizers required gatekeeping: You had to buy an expensive machine (early Moogs cost thousands of dollars). You had to learn it. You had to develop enough skill to use it. This limited supply and maintained quality standards. Bad synthesizer music existed, sure, but the barrier to entry kept the ecosystem from being completely flooded with it.

AI music requires no gatekeeping: The barrier to generating music is $0-20/month for a subscription. No skill required. No artistic intention required. Upload, get paid, next.

Second, synthesizers created new categories of music. Synthesizers enabled electronic music, synthwave, and synth-pop. These were genuinely new genres that expanded the total market. New genres meant new listeners, new venues, new opportunities.

AI music doesn't create new genres—it dilutes existing ones. It's not expanding the pie. It's cutting more slices out of the same pie and distributing them to anyone with a text prompt.

Third, synthesizers democratized expertise, not effort. People still had to learn. They just learned a new skill rather than mastering an acoustic instrument. The barrier shifted, but it didn't vanish.

AI music democratizes output without democratizing skill. Anyone can generate music. Not everyone can generate good music. But the ecosystem rewards volume now, not quality.

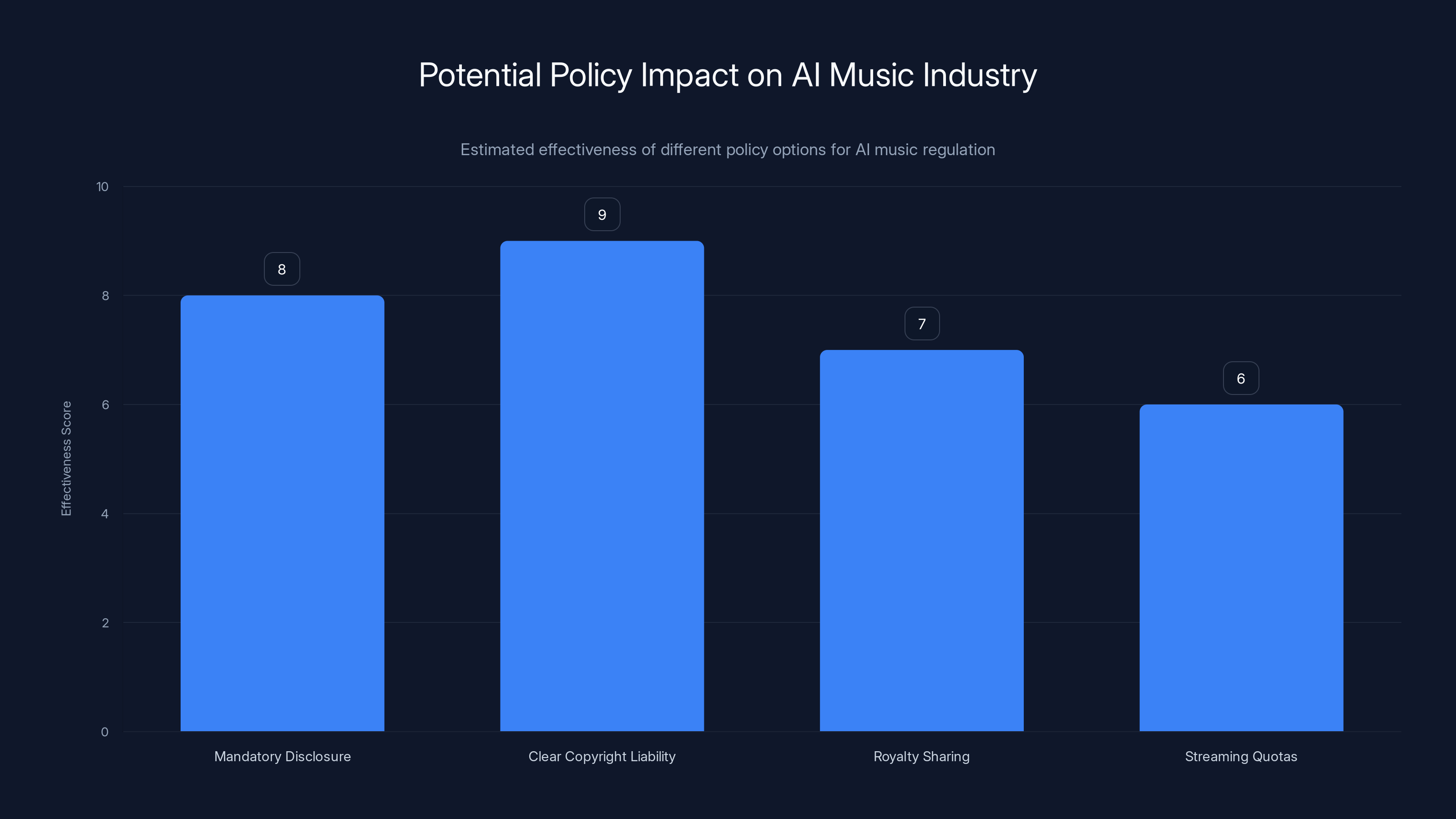

Clear copyright liability is estimated to be the most effective policy, potentially leading to better compliance and fairer compensation in AI music generation. (Estimated data)

What Actually Happened in the Music Industry When New Tech Arrived

We can test the "adaptation always happens" theory by looking at what music industry actually looked like at different technology inflection points.

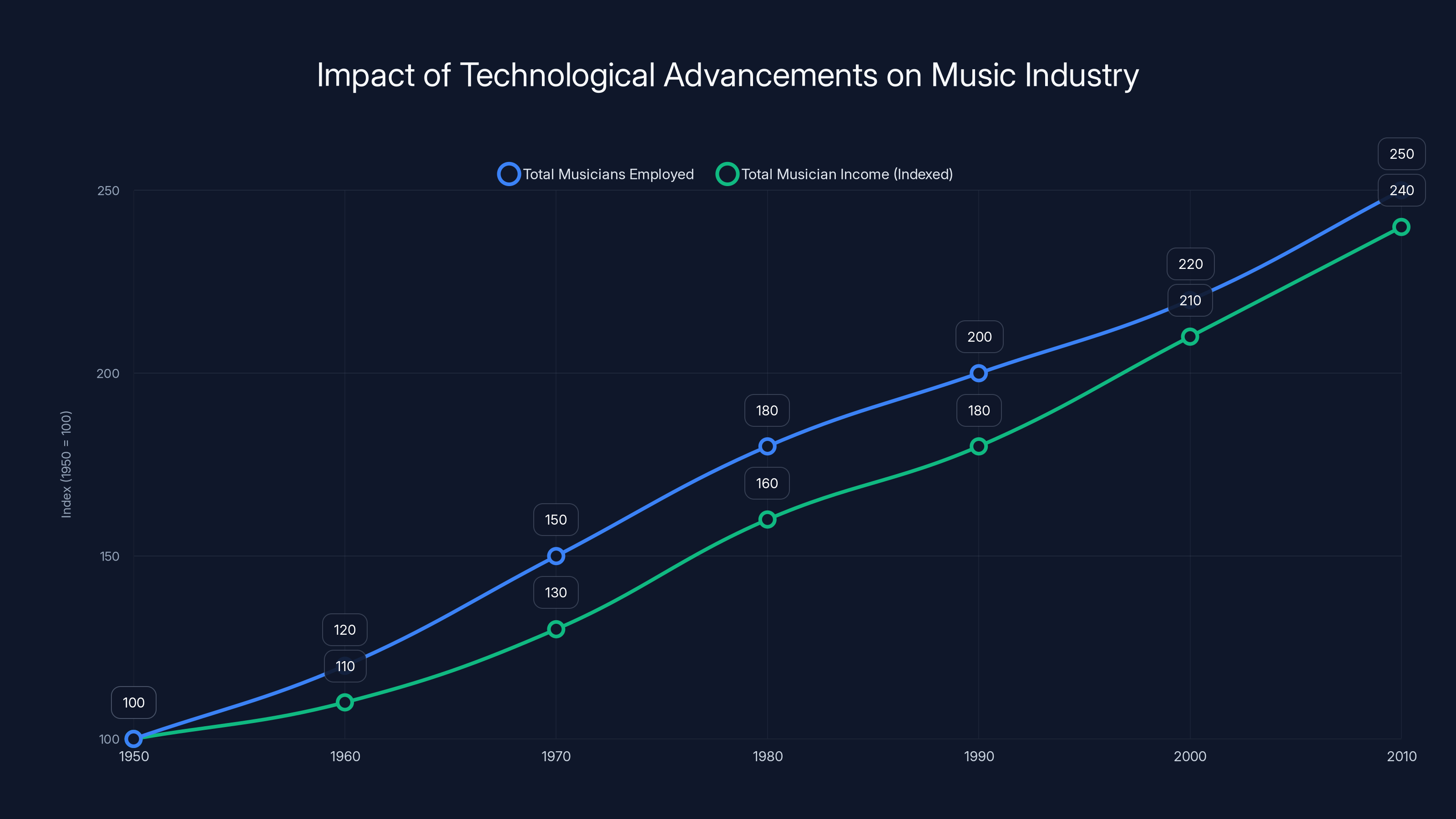

1950-1960: Rock and Roll Disrupts Classical Music

Orchestral and classical music dominated pre-1950. Then rock and roll, pop, and R&B emerged. The old guard panicked. Parents thought rock was corrupting youth. Radio stations wouldn't play it. Record labels were skeptical.

What happened? Both coexisted. Classical music didn't die—it just became a smaller slice of a much larger pie. More people listened to music total. More musicians made more money. Live orchestral concerts still filled concert halls. New touring circuits emerged for rock bands.

Total musicians employed probably increased, even as the classical music percentage of the total decreased.

1970-1980: Home Recording Changes Everything

Multi-track recorders, synthesizers, drum machines, and home recording studios meant musicians didn't need a record label to make professional-sounding music. A band could record in a garage and distribute demos.

Record labels panicked. A&R scouts had less control. Independent labels popped up everywhere. Major labels had to adapt. MTV launched and changed how music got distributed.

What happened? More music got made. More genres emerged. Total listeners increased. But also, the record industry as structured in the 1970s got disrupted hard. Some executives lost power. But total musician income increased because the market expanded.

2000-2010: Spotify and Streaming Disrupts Downloads

Napster, then i Tunes, then Spotify. Musicians who built careers on album sales (where a fan paid

Major artists actually panicked and pulled music from Spotify. Taylor Swift famously pulled her music, arguing the payouts were too low. She was right—streaming pays roughly 1/100th what album sales did per unit.

But what actually happened? Musicians adapted by playing more live shows. Touring became the primary income, not album sales. Concert tickets became more expensive. Artists developed closer fan relationships through social media. New income streams emerged (Patreon, sponsorships, merchandise).

Some musicians lost income. Superstars adapted and thrived. The middle class of musicians—people making steady income from album sales—got squeezed hard.

Notice the pattern? Each technology disruption:

- Creates genuine economic pain for some musicians

- But also expands the total market

- Requires musicians to adapt their business model

- Usually results in different ways of making money, not no ways

But also notice: each time, the people who lost the most were the middle class. The superstars adapted. The struggling amateurs got opportunity. But the musicians making a comfortable living from their music—that group kept shrinking.

AI music could follow the same pattern. But it could also be different, because streaming already compressed the middle class of musicians. There might not be much more margin to compress.

The Specific Ways AI Music Generation Could Actually Harm Working Musicians

Let's be concrete about the harm mechanisms, not hypothetical panic.

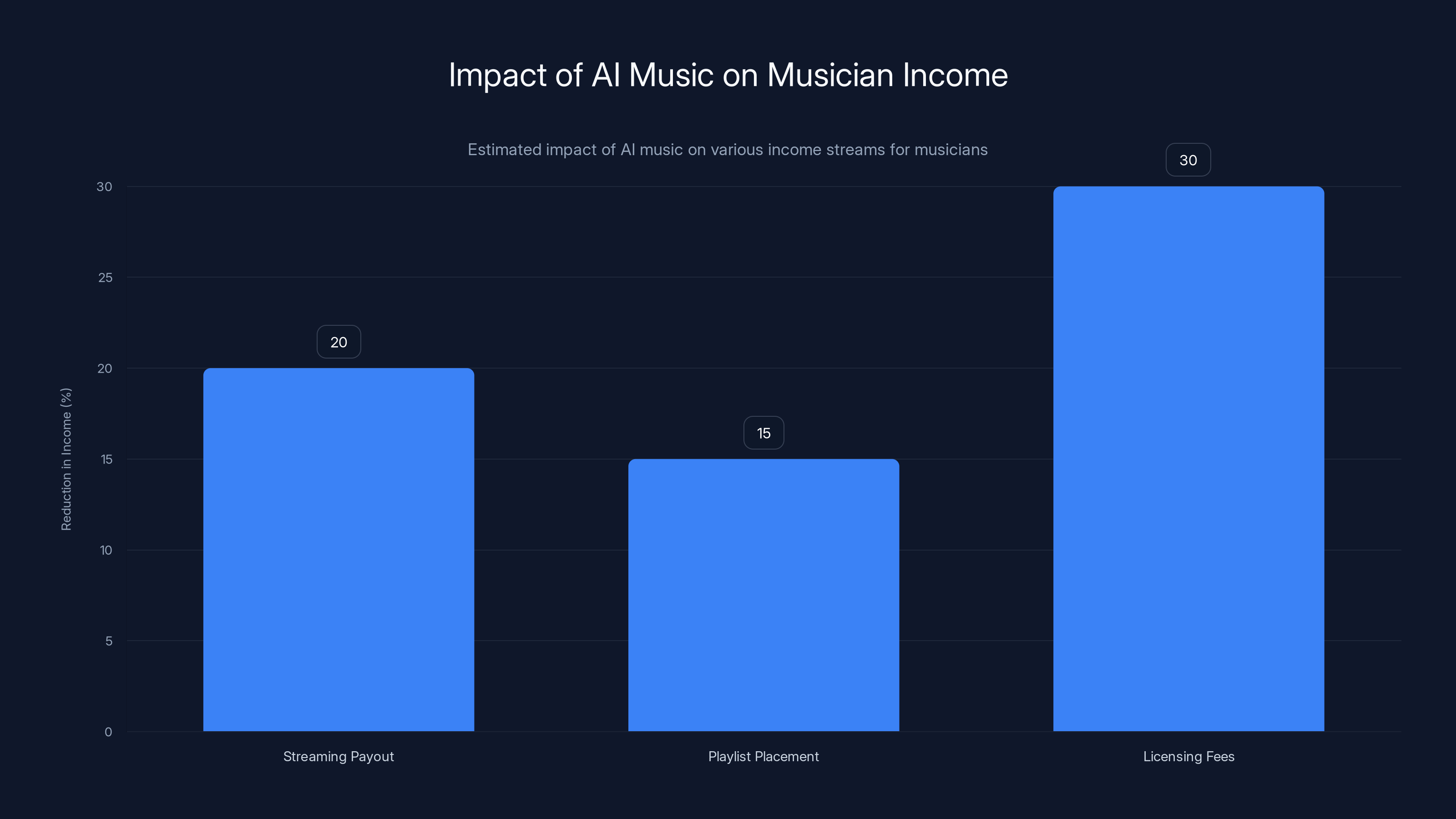

1. Streaming Payout Dilution

Streaming platforms have a fixed budget. If Spotify pays out $500 million monthly to artists, that amount doesn't change based on how much music gets uploaded. More songs = more competition for the same money.

A musician releasing an original album today competes against:

- Other original albums

- Compilation albums

- Soundtrack albums

- Covers of famous songs

- And now: 10,000 AI-generated songs in the same genre

Each of those AI songs might only get 1,000 streams. But there are so many of them that collectively, they're pulling streams away from human musicians. The payout per stream keeps dropping.

2. Playlist Saturation

Spotify and Apple Music control how most people discover music. A good playlist placement could mean millions of streams. Getting on "New Music Daily" or "Today's Top Hits" could make a song.

But if AI-generated songs saturate the middle-tier playlists (good enough to listen to, but not amazing), curators might decide to deprioritize human artists and just use AI songs. Why pay for rights when you can use AI-generated music with zero licensing hassle?

Some services are already experimenting with this. You can see You Tube creators using AI-generated background music instead of licensed music, specifically because it's cheaper and has fewer legal complications.

3. Race to the Bottom on Licensing

Imagine you're a podcast producer, a You Tuber, or a small business needing background music. A professional musician might quote you

But AI-generated music costs

Over time, more people choose cheap AI music. Musicians have to lower prices to compete. Prices compress across the industry. Total musician income drops because they're not getting any of the AI-generated music work, plus their regular licensing rates fall.

4. Copyright Ambiguity

If you use an AI tool that trained on copyrighted music without permission, who's liable? You? The tool creator? Both?

Right now, the answer is unclear. But the ambiguity means musicians can't easily enforce their rights. Deploying the tool is cheaper than licensing existing music, so companies do it. By the time courts rule, the damage is done.

5. Replacement of Commodity Work

Not all music work is artistically fulfilling. Some musicians make money scoring corporate videos, writing background music for podcasts, or creating royalty-free music libraries.

This is often where emerging musicians build skills and earn early income. If AI-generated music takes over this commodity work, emerging musicians lose their entry point. They never develop skills. They never build experience. The pipeline breaks.

Music could follow the same trajectory. The commodity work goes to AI. Only premium work (actually good songs, nuanced scoring, genuine artistry) stays with humans. The problem is that commodity work is where most musicians start.

So the harm is real, specific, and measurable. It's not synthesizer panic. It's legitimate economic concern about a specific disruption mechanism.

Estimated data shows that both musician employment and income have increased over time, despite disruptions from new technologies.

The Current State of AI Music Tools (And Why They Actually Matter)

Let's look at what's actually being deployed right now, because the tools matter more than the hype.

Suno and Udio are the most visible tools. They let you type a prompt like "upbeat indie pop song about cats" and generate a complete song with lyrics, instrumental, and vocals in under a minute.

They're actually not terrible. If you need background music for a video and don't care about quality, they work. The lyrics are usually generic ("loving you is all I need, you're my melody") and the production is plasticky, but functional.

But here's the important part: they're getting better rapidly. Suno's v 4 model was noticeably better than v 3. Udio's outputs improved month-to-month.

There are also more specialized tools:

- AIVA: Focused on film and game scoring

- Amper: Focused on royalty-free background music

- Musicfy: Voice cloning for singers

The scary part isn't what these tools do now. It's the trajectory. If the improvement rate continues, we're probably 18-24 months away from AI-generated music that's genuinely hard to distinguish from human-made music.

Open AI doesn't even have a public AI music tool, but they're clearly working on one. When they release it, it'll probably be better than Suno just because they have more compute and data.

The window to establish ethical guidelines, copyright protections, and fair compensation mechanisms is closing fast. By the time regulation catches up, the tools will be everywhere.

The Copyright Problem No One Is Solving

Here's where the situation gets genuinely murky.

Suno's terms of service say they trained on "a diverse range of music" but they don't specify whether they have licenses for all of it. Almost certainly, they don't. They scraped music from the internet. That music was copyrighted. They used it without permission.

Now, there's an argument that this is "fair use"—transformative learning is sometimes protected. But fair use doesn't apply equally to everyone. Open AI has the legal resources to fight copyright cases. An independent musician doesn't.

So what happens in practice? Musicians whose work was used in training can sue. But the litigation costs are high and the damages are uncertain. Most musicians never find out their work was used. The companies bet that most won't sue.

Meanwhile, the tools are generating income. Suno raised millions in venture funding. That value came, partly, from using copyrighted music without permission. The musicians got nothing.

There are lawsuits coming. But lawsuits are slow. By the time they resolve, the technology will have moved on.

This is different from synthesizers. Synthesizer makers didn't steal anything. They built new instruments. Musicians could choose to use them or not.

AI music generators stole the training data from existing musicians, then built a tool to replace the work those musicians would otherwise do. That's multiple layers of harm, not just "new technology."

Estimated data suggests AI music could reduce musician income by 20% from streaming payouts, 15% from playlist placements, and 30% from licensing fees.

What We Should Actually Worry About (And What We Shouldn't)

Don't Worry About:

AI replacing Taylor Swift or The Weeknd. Fans don't want AI music from those artists. They want the artist—the personality, the story, the vision. A good AI Taylor Swift impersonation is actually less appealing than the real thing because it's missing the authenticity that makes her music valuable.

AI killing live music. People will still want to see musicians perform live. The human connection is part of the value. AI can't do that (yet).

AI killing all studio work. Some music requires genuine artistic vision and taste. AI can't do that well. Film composers, album artists, and genre innovators will continue to exist because there's real demand for their specific creative choices.

Do Worry About:

Streaming payout compression. As AI music floods the ecosystem, payouts per stream will keep declining. This is predictable, measurable, and happening.

Entry point erosion. If all the commodity music work (background music, royalty-free libraries, podcast music) goes to AI, emerging musicians lose their career ladder. They can't build experience and income in the low-stakes, low-pay work that leads to better opportunities.

Copyright theft laundering. If AI training on copyrighted music is legal (or just not enforced), companies can steal artists' work, profit from it, and pay nothing. This directly extracts value from creators.

Platform control. Spotify, Apple Music, You Tube—they control distribution. If they decide to use AI-generated music for certain categories to save licensing costs, musicians lose leverage. They can't negotiate better rates because the platform has an alternative.

Right now, Runable and other AI platforms can generate music instantly, but the legal and ethical framework for how they should operate doesn't exist yet. The tools are outpacing regulation.

How We Could Handle This Better Than "Ban It" Or "Let It Run Wild"

The interesting question isn't whether AI music generation is good or bad. It's how we structure it so the benefits are captured fairly and the harms are minimized.

Here are some actual policy options, not fantasy:

1. Mandatory Disclosure and Consent

If an AI model trained on your music, you should know about it. The company should tell you. You should be able to opt out of future training. And if they've already trained on your work, you should be compensated.

This is similar to GDPR in Europe—you have the right to know what data about you was collected, and you can request deletion.

Implementing this would be complex but doable. Most AI music companies could probably implement it in months if they wanted to.

2. Clear Copyright Liability

If an AI-generated song is indistinguishable from a human-generated song, and it infringes copyright, who's liable? The user? The company? Both?

Right now, the terms of service say the user is liable. That's convenient for the companies—they build the tool, users take the risk. That's backwards.

Legal clarity would change incentives. If companies were liable for copyright infringement, they'd be much more careful about training data and output quality.

3. Royalty Sharing

If Suno's model trained on 100,000 songs, those artists should share in Suno's revenue. Not equally—a song with 10 million training samples probably influenced the model more than a song with 100 samples. But some formula that ties revenue back to the artists whose work powered the model.

This would require blockchain or some verification system, which is complex. But Spotify already tracks millions of streams. The infrastructure could exist.

4. Streaming Platform Quotas

Spotify could implement a rule: maximum 10% of total streams can come from AI-generated music. This would limit dilution while allowing AI music to exist.

This might seem protectionist, but it's not really different from how radio stations already work. They limit how many ads, how much of the same artist, etc. Platforms already curate.

5. Transparency About Training

If an AI model trained on a specific artist's work, that should be disclosed when the model is used. "This song was generated using a model trained on the works of X, Y, and Z."

This wouldn't prevent AI music, but it would prevent the pretense that it's original. Users would know what they're getting.

6. Separate Licensing Category

Right now, AI-generated music and human-generated music share the same licensing categories. They shouldn't.

A company licensing music for a commercial should pay more for human-made music and less for AI-generated music. This would preserve the market value of human music while allowing AI to fill the low-value slots.

None of these are "ban AI music" solutions. They're "integrate AI music into the ecosystem fairly" solutions.

But they all require companies to accept less profit in exchange for fairness. And right now, there's no incentive for that. So nothing will happen until regulation forces it.

What Musicians Are Actually Doing Right Now

Instead of just panicking, some musicians are being strategic.

Some are using AI to enhance their work. A composer might use AI to generate rough sketches of ideas, then refine them. They're not replacing themselves. They're using the tool to move faster.

Some are opting out of training data. Universal Music Group and Sony Music are pushing back against AI companies using their artists' music without permission. This is probably not enough to stop the technology, but it's signaling that the industry isn't accepting this passively.

Some are using it as a business opportunity. Musicians are creating "artist-approved" AI models of their own voice. You can use their voice to create new music, they get a cut. This could actually create new revenue streams rather than destroying existing ones.

Some are just waiting to see what happens. Most working musicians are busy actually playing music and making records. They're not obsessing over AI. They'll adapt when they need to, just like they adapted to synthesizers and streaming.

The smart musicians are the ones treating this as "new tool, figure out how to use it or neutralize it" rather than "existential threat, panic."

Why This Moment Matters More Than The Synthesizer Moment

So here's the honest take: is this just another moral panic about technology, or is this actually different?

It's actually different, but not for the reasons most people think.

The synthesizer disruption happened in a growing industry. Record companies were expanding. Concert tickets were selling more. The total economic pie was growing. When a new technology arrived, musicians could adapt because there was overall growth to absorb the disruption.

But the music industry in 2024 isn't growing. Streaming has compressed it. The total payout to artists hasn't grown in a decade even as consumption has increased. There's no growth to absorb the disruption. It's purely redistributive.

So when AI music arrives, it's not arriving into a growing ecosystem where everyone can adapt. It's arriving into a zero-sum ecosystem where one person's gain is another person's loss.

That's the meaningful difference. Not "synthesizers vs. AI" but "growing industry vs. plateauing industry."

Second, synthesizers required gatekeeping. That gatekeeping maintained quality and limited supply. AI music has no gatekeeping. The supply constraint is gone. That changes everything.

Third, the companies deploying this have already shown they'll take shortcuts on copyright and ethics. Open AI, Anthropic, Suno—they all trained on copyrighted work without explicit permission. They did this because the legal framework is unclear and they calculated that paying later (if sued) is cheaper than asking permission now.

Synthesizer companies were just making instruments. They weren't stealing intellectual property.

So the panic is partially justified. Not because AI music is inherently evil, but because the current implementation extracts value from musicians without compensation, and the companies deploying it aren't motivated to change that on their own.

The Future Scenario Nobody Talks About

Here's a future that's plausible: AI music becomes good enough that most people use it for background music, commercial music, and royalty-free libraries.

Human musicians still make music, but only in premium categories—high-profile artists, film scores, conceptual albums, live performance. The mass market for commodity music goes entirely to AI.

This could actually work reasonably well. Premium musicians get paid for premium work. AI handles everything else. Listeners get cheap background music.

But the transition is brutal. All the musicians currently making a living in the commodity category—the upcoming artists, the sessionists, the coffee shop performers—suddenly have no income.

That's not "adaptation." That's displacement.

It's possible the industry absorbs them and they move upmarket. But it's also possible there's just less money available, and many of them exit music entirely.

The synthesizer analogy breaks down because synthesizers didn't displace existing musicians from their existing gigs. They just added a new tool for new gigs. AI music is different. It's directly replacing existing gigs with AI-generated versions.

What Actually Needs To Happen

If we want AI music to exist in a healthy ecosystem rather than a extractive one, three things need to happen:

1. Legal Clarity (Months to Years)

Courts and legislatures need to decide: does training AI on copyrighted music without permission violate copyright? Is there a fair use exception? What's the liability chain?

The current ambiguity is being exploited. Companies are moving fast and breaking things because the rules aren't clear yet.

2. Industry Standards (Years)

Once legal questions are answered, industry standards need to emerge. How are musicians credited? How are they compensated? What disclosure is required?

This probably won't happen voluntarily. It'll take industry pressure, regulation, or antitrust action to force companies to adopt standards that hurt their bottom line.

3. Musician Collective Action (Months)

Musicians have leverage if they use it. Universal Music Group pulled music from Tik Tok in 2023 over payment disputes and won. If musicians collectively refuse to license their music to companies using AI training data, that changes incentives.

But this requires coordination. Individual musicians can't do it. Industry groups can.

Is This Just Panic?

No, it's not just panic. But it's not inevitable doom either.

The panic has a real basis. The economic disruption is real. The copyright theft is real. The platform consolidation is real.

But panic without strategy just leads to either ineffective bans (which won't work) or capitulation (which enriches only the companies deploying AI).

The question isn't "should we ban AI music?" It's "how do we structure AI music so everyone shares the value?"

Synthesizers succeeded because they expanded the market and musicians adapted. But that only worked because the total market was growing. AI music is arriving in a shrinking market, which means adaptation is much harder.

Musicians aren't wrong to be concerned. The companies deploying this are moving fast and not asking permission. The legal framework is unclear. The economics are extractive.

But the path forward isn't nostalgia for a pre-AI world. It's pushing hard for regulations that make AI companies compensate the artists whose work they used, disclose when music is AI-generated, and accept that some work should stay human-made.

That's not panic. That's negotiation.

And honestly? The musicians have more leverage than they think. Spotify without music is useless. Apple Music without music is useless. You can't build a music-generation AI without accessing music.

The power isn't as asymmetrical as it feels right now. It just requires musicians to act collectively instead of individually.

Whether that happens is the actual question—not whether AI music is good or bad, but whether musicians can organize well enough to extract fair terms from the companies deploying it.

History says they can. The union negotiations with record labels in the 1940s, the synthesizer adaptation in the 1970s, the streaming negotiations of the 2010s—musicians have successfully pushed back against tech disruption before.

They can do it again. But only if they're strategic instead of just panicked.

FAQ

What exactly is AI music generation?

AI music generation uses machine learning models trained on thousands of existing songs to create new music based on text prompts. You describe what you want ("upbeat pop song about coffee") and the AI generates a complete song with lyrics, instruments, and vocals. The model learned patterns from existing music and recombines them in novel ways. Think of it like a very sophisticated remix engine that can create original combinations of patterns it learned during training.

How is AI music different from how synthesizers worked?

Synthesizers required musicians to learn an instrument, understand music theory, and develop creative choices. They amplified skill but didn't replace it. AI music requires no skill—you type a prompt and get output. That's fundamentally different because it removes the barrier to entry entirely, allowing anyone to generate competent-but-generic music regardless of their musical knowledge. Synthesizers created new categories of music; AI music dilutes existing categories by flooding them with quantity.

Why are musicians actually concerned about AI music generation?

The concerns are economic and legal. Economically, streaming payouts are fixed-pool, so AI-generated music increases competition for the same payout pool, reducing what human musicians earn per stream. Legally, most AI music models trained on copyrighted music without permission, so companies extracted value from musicians without compensation. Additionally, AI music threatens the "commodity work" (background music, royalty-free libraries) where emerging musicians traditionally build experience and income. The concern isn't replacement—it's dilution, devaluation, and copyright theft.

Is this just another example of musicians panicking about new technology?

Partially, yes. Musicians have feared every major technology shift. But this is actually different in meaningful ways. Synthesizers arrived during industry growth; AI music arrives during industry contraction. Synthesizers required skill and gatekeeping; AI requires neither. Synthesizers didn't violate copyright; AI training did. So while the panic pattern is familiar, the actual threat structure is different. The real question isn't whether change is happening, but whether it's structured fairly or extractively.

Could AI music actually benefit musicians?

Yes, in specific contexts. Composers can use AI to prototype ideas quickly. Musicians can create artist-approved AI models of their voice and earn royalties when others use them. Students can learn music production by studying how AI structures songs. Content creators can access cheap background music legally. The key is distinguishing between AI as a tool that enhances human creativity versus AI as a replacement for existing musician income. The benefits exist; the question is whether current deployment prioritizes them or profits.

What happens to concert music if AI can generate studio recordings?

Live music is fundamentally different from recorded music. People pay for concerts because of the human presence, the energy, the uniqueness of each performance. An AI can't replicate that. Concert attendance probably won't decrease from AI-generated studio music. However, studio work (session musicians, background music, scoring) could be affected more than live performance. The threat is more to studio musicians' income than to concert musicians.

How would musicians actually be compensated fairly for AI training data?

Several mechanisms could work: mandatory disclosure and consent (tell musicians when their work is used, let them opt out), royalty sharing (artists whose work was used for training receive a percentage of AI revenue), separate licensing (AI-generated music and human music have different license categories and pricing), and verified consent (prove you have permission before training on protected work). These aren't fantasies—versions of them exist in other industries. They'd require regulation or industry standards to implement, which doesn't happen voluntarily.

Will copyright courts eventually rule in favor of musicians?

Probably some version of "yes," but with delays and limitations. Courts are already seeing copyright cases involving AI training (Sarah Silverman vs. Open AI, ongoing music cases). The outcomes will likely establish that companies need licenses or explicit consent, but by the time courts rule definitively, the technology will be entrenched. Even if musicians win legally, the financial damages might be less than the economic value already extracted. Speed matters—courts are slow, tech is fast.

What should musicians do right now to protect themselves?

Three practical things: First, stay informed about which AI companies trained on your work and what their terms say. You might need to pursue legal action eventually. Second, don't ignore the opportunity—some musicians are creating artist-approved AI models of their voice, which could generate additional income. Third, support industry groups pushing for regulation. Individual musicians have limited power, but collective action (like UMG pulling from Tik Tok) actually changes company behavior.

Is there a scenario where AI music and human music coexist healthily?

Yes. If AI music fills the low-value slots (background music, royalty-free libraries, placeholder content) while human musicians maintain premium categories (high-profile releases, film scoring, concert performances), both can exist. Synthesizers and acoustic instruments coexist this way. But that only works if the rules are structured so AI music is clearly labeled, fairly compensated in terms of rights-holder royalties, and companies can't just use it to eliminate human musicians from categories that were previously their domain.

The Bottom Line

Synthesizers didn't kill music. But they were introduced during industry growth, required skill to use, and had clear gatekeeping. AI music is different—it's arriving in an industry that's contracting, requires no skill, and has zero gatekeeping.

But that doesn't mean it will kill music either. What it means is that this disruption requires more active management than "let the market adapt."

Musicians have legitimate reasons to be concerned—not paranoid, but rational. The current implementation is extractive. Companies trained on copyrighted work without permission. They're flooding markets to dilute competition and compress payouts.

But the solution isn't to ban AI music. It's to structure it fairly: compensate artists whose work was used for training, disclose when music is AI-generated, and maintain human musicians in categories where that matters.

That requires legal action, industry standards, and musician leverage. All of which are possible.

The question isn't whether this is just another moral panic about technology. It's whether musicians will be strategic enough to extract fair terms from the companies deploying it.

History says they can. The outcome depends on whether they actually do.

Key Takeaways

- There's this thing that happens every time a major technology disrupts an industry: panic

- When recorded music became mainstream in the early 1900s, live orchestras really did start losing gigs

- You don't need to know music theory

- You don't need to understand production

- Streaming Economics 101: When a major platform like Spotify pays out money to artists, it divides a fixed pool among all songs played

Related Articles

- Western Digital's 2026 HDD Storage Crisis: What AI Demand Means for Enterprise [2025]

- Netflix, Warner Bros., and Paramount Merger War [2025]

- Indian Pharmacy Chain Data Breach: How Millions Were Exposed [2025]

- Best Fitness Earbuds to Keep You Motivated Through Workouts [2025]

- Solar Thermal Energy Storage: How Molecules Store Heat for Months [2025]

- NYT Strands Answers & Hints Game #716 Feb 17 [2025]

![AI Music Generation: History's Biggest Tech Panic or Real Threat? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-music-generation-history-s-biggest-tech-panic-or-real-thr/image-1-1771378994717.png)