Introduction: The Fall of American Automotive Leadership

Thirty years ago, the American auto industry wasn't just dominant—it was untouchable. Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler produced vehicles that defined entire generations. The assembly line was an American invention. Mass manufacturing was an American perfection. Detroit's Big Three exported confidence alongside their cars, with plants humming across the Midwest and profits flowing into executive suites with the inevitability of gravity.

Then something broke.

Not all at once, but in a series of cascading failures that reads like a corporate tragedy. First came the fuel crisis of the 1970s, when Japanese manufacturers waltzed in with smaller, more efficient vehicles that actually got you to work without bankrupting you. American consumers noticed. Then the 1990s and 2000s delivered financial crises, quality scandals, and a stubborn insistence on building bigger vehicles while the world demanded better ones.

But the real death knell came with something the Big Three saw coming from miles away and still managed to miss completely: electric vehicles.

For decades, EVs were the future. Then they became the present. Then they became the profitable present. And when that moment arrived, American automakers were caught flat-footed, having spent years dismissing Tesla as a niche experiment run by a billionaire with unrealistic expectations.

The financial reckoning has been brutal. Ford announced a

This isn't a story about market cycles or consumer preference. It's a story about how the world's most powerful automotive industry made almost every wrong decision simultaneously, then found themselves further handicapped when political winds shifted against their last chance to recover.

The question isn't whether America lost the EV race. It's whether America lost the automotive future entirely.

TL; DR

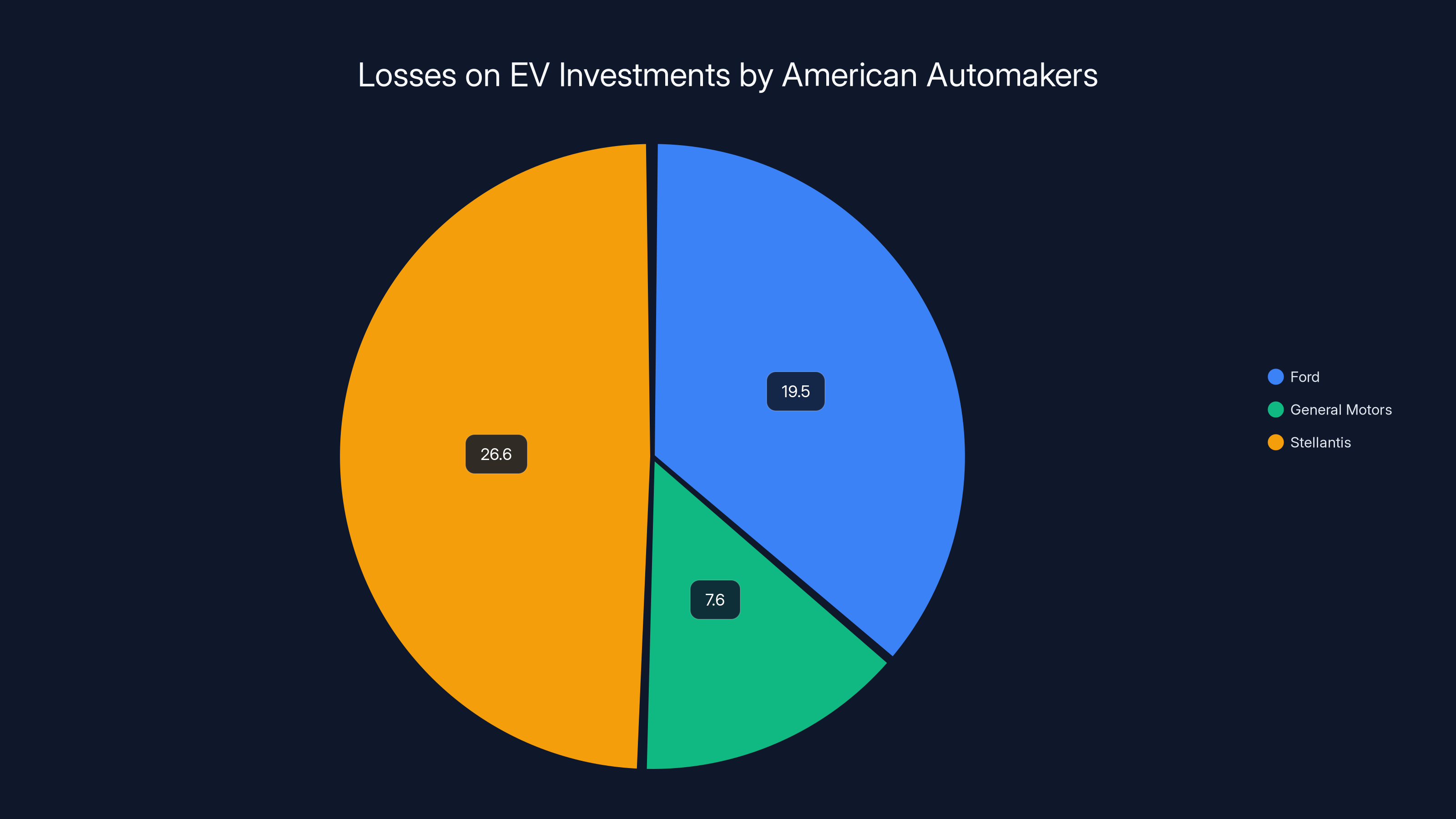

- **19.5B), GM (26.6B) wrote down failed EV investments

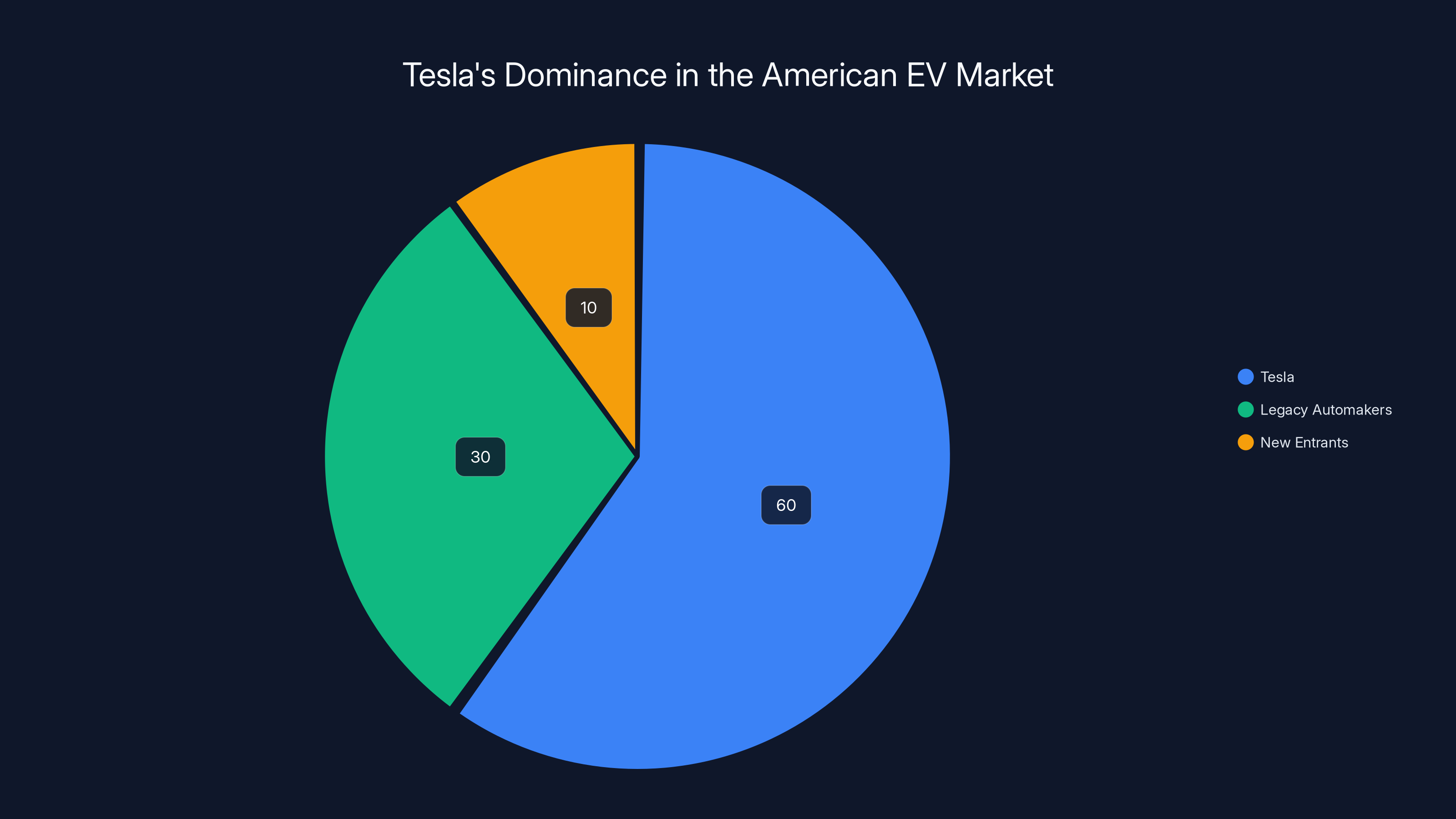

- Tesla now dominates: American EV market share belongs to a company the Big Three dismissed as unprofitable

- Legacy carmakers focused on profit, not innovation: Gas-powered trucks and SUVs funded EV development, but the EV products themselves lacked competitiveness

- Political headwinds eliminated support: Removal of the $7,500 EV tax credit and rollback of emissions standards gave automakers permission to abandon EVs

- International competition tightens: Chinese manufacturers are moving into US markets while Detroit retreats to gas vehicles

- The risk is real: America could become a customer of foreign automotive technology rather than a leader

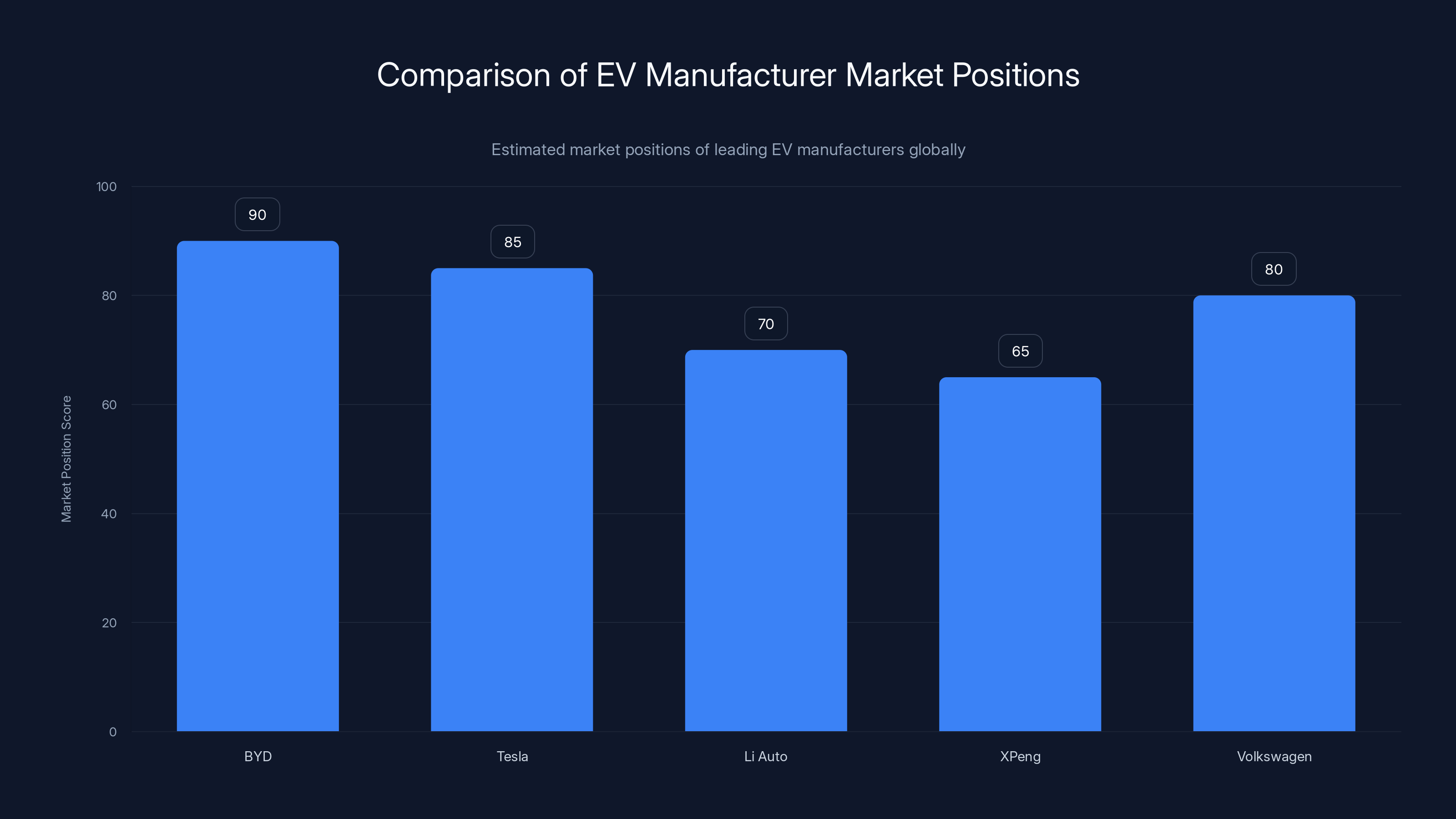

Estimated data shows BYD leading the global EV market, followed closely by Tesla, with Chinese automakers Li Auto and XPeng rapidly gaining ground. European manufacturers like Volkswagen are also competitive.

What Actually Went Wrong: The Real Timeline

The story of Detroit's EV failure isn't a single moment. It's dozens of decisions, each one rational at the time, that added up to strategic disaster.

Start in the 2010s. Tesla had delivered the Roadster, then the Model S, and suddenly had a cult following. But here's how legacy automakers saw it: Tesla was unprofitable, building maybe 50,000 vehicles a year, and had never paid a dividend. The traditional auto business—Ford, GM, Chrysler—was about volume. Profitable volume. Tesla was volume-averse, deliberately keeping production constrained to maintain margins. To Detroit, that wasn't ambition. That was failure.

Meanwhile, the Big Three had real manufacturing capacity, dealer networks spanning the country, and supply chains that could actually build millions of vehicles. They had the real advantages. Tesla had hype.

So they waited. They watched. They commissioned studies showing that Americans didn't actually want EVs because charging infrastructure was underdeveloped. (Circular logic, but compelling to a board room.) They concluded that hybrids were the "realistic" bridge technology. They built electric versions of existing gas cars—slapping battery packs under conventional platforms and calling it innovation.

The Chevy Bolt was the one exception. A purpose-built EV that actually worked. Affordable. Practical. Good range. For a moment, it looked like maybe Detroit had it figured out. Then GM discontinued it. The company's own internal analysis showed the Bolt had better profit margins per unit than the gas-powered vehicles competing in its segment. Yet GM killed it anyway, redirecting resources to develop trucks and SUVs with optional electric powertrains. Why? Because a Bolt might cannibalize sales of more expensive vehicles with bigger profit margins. Short-term thinking dressed up as strategy.

By 2020, Tesla was hitting profitability. By 2021, they were printing money. Meanwhile, Ford was still rolling out the Mustang Mach-E—a competent EV that was somehow both expensive and underwhelming, lacking the software sophistication or charging infrastructure momentum that Tesla was building.

The product gap wasn't just about the cars. It was about the entire ecosystem. Tesla owned its charging network. Automakers shared infrastructure that was fragmented and unreliable. Tesla had software that improved over time. Automakers had infotainment systems that felt like they were designed in 2008. Tesla's vehicles got faster and better through software updates. Most Detroit EVs felt like they peaked on day one.

Then came the most self-inflicted wound: executives believed their own narrative that EVs were niche, that Americans preferred gas vehicles, that the transition would take decades. This belief persisted even as actual market data showed EV adoption accelerating. It's what happens when you're profitable selling one thing and terrified of cannibalizing that profit with something new.

By the time the Big Three finally committed to EVs—really committed, with hundreds of billions in planned investments—they were building vehicles for a market that had already moved on. They were playing checkers while Tesla played chess.

Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis collectively lost over $50 billion on EV investments, highlighting one of the largest strategic failures in automotive history.

The Dealer Problem: Why Incentives Were Misaligned

There's a detail that rarely gets emphasized enough: American car dealerships actively opposed the EV transition. Not subtly. Not through quiet lobbying. Directly.

Here's why. A dealership's profit structure is built on two things: selling vehicles and servicing them. The vehicle sale itself is actually relatively low-margin—the real money comes from warranty work, routine maintenance, and repairs spread across the lifetime of ownership.

Electric vehicles require dramatically less maintenance. No oil changes. No transmission fluid. No spark plugs. Brake pads last longer because of regenerative braking. The service department—often the most profitable part of a dealership—essentially becomes obsolete.

A BMW dealer in suburban America realizes that if customers start buying electric BMWs, the service revenue that funds his operation evaporates. So he doesn't push the electric vehicles. He steers customers toward gas-powered alternatives. "You're not ready for electric yet," he tells them. "Charging infrastructure isn't there." "You'll regret the range limitations."

Manufacturers noticed this. They saw their dealers actively working against their electric vehicle rollouts. So what did they do? They accommodated the dealers. They didn't crack down on the misalignment. They didn't realign incentives. They listened to the dealers and concluded, "I guess Americans don't want EVs."

This wasn't unique to one brand. It was endemic. The entire dealer network was economically incentivized to kill the EV transition, and the manufacturers allowed that to happen because changing the system would have meant confronting the dealers, and dealerships are powerful players in every state's economy.

Tesla, notably, bypassed this entirely. Tesla owns its stores. Tesla handles its own service. There's no dealer misalignment because there's no dealer. When you're not dependent on a middleman with conflicting incentives, you can actually execute on a strategy.

The Big Three are now trying to fix this through company-owned EV dealerships, but the damage is done. Dealers still have veto power in most states. Tesla already owns the market.

The Tax Credit Withdrawal: A Self-Inflicted Coup

Let's talk about what happened when the $7,500 EV tax credit disappeared.

In theory, removing the credit should have been inconsequential to the long-term transition. EVs were supposed to have achieved price parity with gas vehicles anyway, right? That was the story—EVs would eventually be cheaper on a total-cost-of-ownership basis even without subsidies.

Except they hadn't. Not quite. The credit was closing a gap. It was the difference between "this is expensive" and "this is reasonable." For price-conscious consumers, $7,500 was the deciding factor.

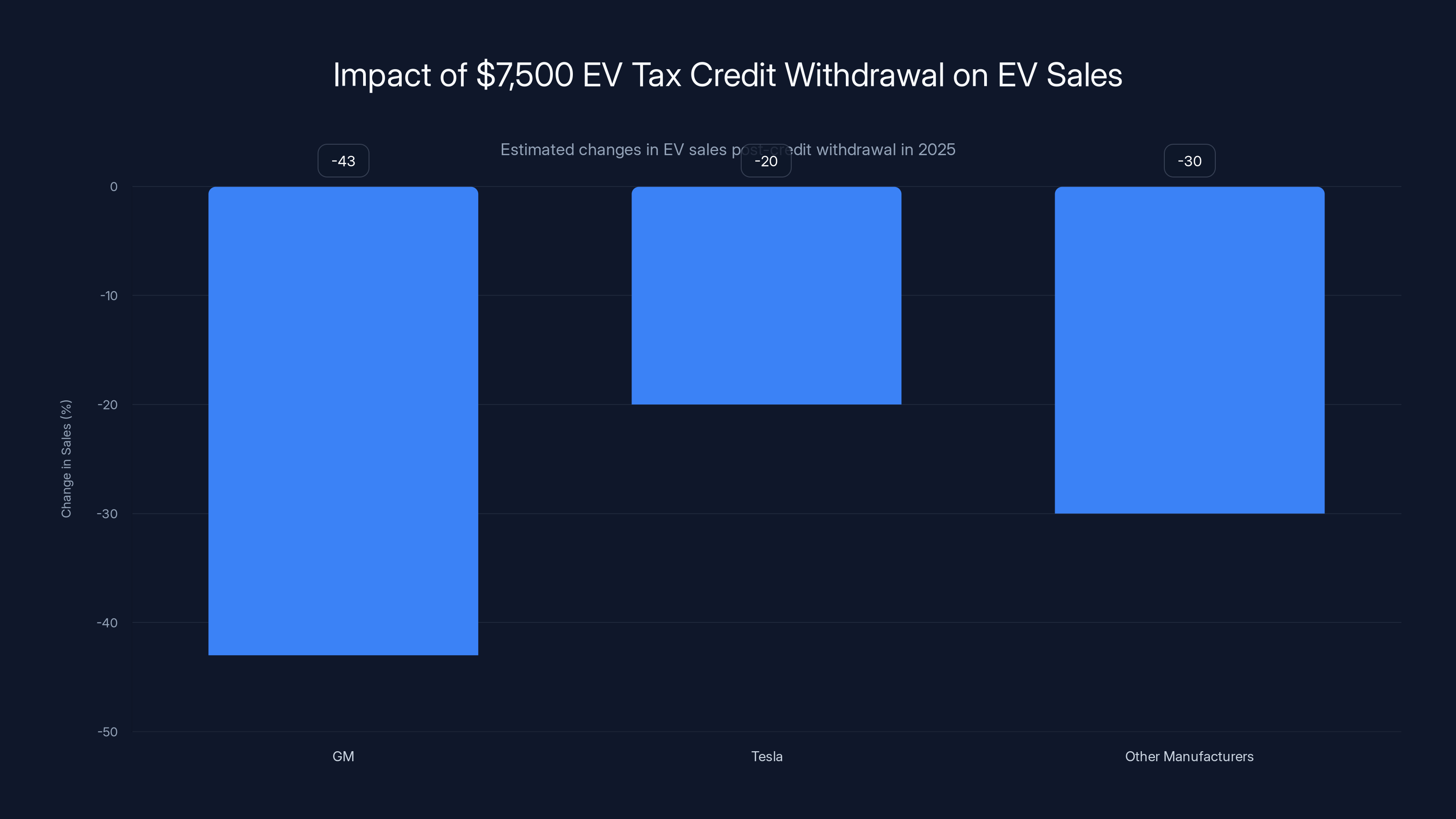

When the Trump administration eliminated the credit in early 2025, the market froze instantly. GM reported a 43 percent decline in EV sales in the quarter immediately following. Tesla dropped prices to compete. Other manufacturers watched as volume evaporated.

But here's the crucial part: the tax credit wasn't eliminated because the economics suddenly changed. It was eliminated because EVs became politically toxic. The Trump administration campaigned on "American energy independence," which somehow translated into "don't build electric vehicles." (The logical contradiction of this position—where American-manufactured EVs with American-mined minerals somehow equals foreign dependence—was never satisfactorily explained.)

Regardless, the political calculation was straightforward: EVs were unpopular with the voter base. Removing support for EVs was good politics. The fact that it devastated the emerging EV industry and handed market dominance to Tesla (a company Trump often criticized) seemed beside the point.

The irony is that the credit was already winding down by design. It was supposed to expire as the EV market matured. Instead, it was killed prematurely, right when the market was finding its footing, and the manufacturers who'd bet on the EV transition suddenly faced a market collapse they couldn't withstand.

Ford had already cut the F-150 Lightning's production targets. The vehicle, which Ford had promoted as the return of the Model T—the vehicle that democratized automobiles—was revealed to be commercially unviable at scale. The numbers showed it couldn't compete with gas-powered trucks at the price points American consumers expected.

This is the critical point: the vehicles themselves were the problem. The tax credit was helpful, but it wasn't the fundamental issue. Detroit made expensive EVs that weren't good enough to compete with Tesla on quality, weren't good enough to compete with gas vehicles on practicality, and landed in an uncomfortable middle where they were the worst of both worlds.

Estimated data shows a significant decline in EV sales across manufacturers following the removal of the $7,500 tax credit, with GM experiencing a 43% drop.

Emissions Standards Rollback: Permission to Abandon the Future

In February 2025, the EPA—now under an administration hostile to climate policy—completed a rollback that had seemed unthinkable just months earlier.

The agency rescinded the "endangerment finding" that greenhouse gas emissions pose a danger to human health. This finding, first adopted in 2010, was the legal foundation for the vehicle emissions standards that effectively required automakers to build more electric vehicles.

Without the endangerment finding, there are no emissions standards. No mandates. No fines for exceeding fuel consumption limits. No requirement to buy credits from EV makers like Tesla (which Tesla had made a profitable business of selling to gas-powered automakers). Automakers now have what the industry calls "breathing room."

In plain English: they have permission to abandon electric vehicles entirely and make gas-powered vehicles for as long as they're profitable.

Margo Oge, who served as the EPA's top vehicle emissions regulator under three administrations spanning two decades, told the New York Times: "The US no longer has emissions standards of any meaning. Nothing. Zero. Not many countries have zero."

Let that sink in. The world's largest economy, home to the world's most advanced automotive industry, now has no meaningful environmental standards for vehicle emissions. This isn't a return to previous levels. It's regulatory collapse.

What's remarkable is how quickly automakers interpreted this. Within days of the announcement, manufacturers began curtailing EV development programs, shifting resources back to truck and SUV production. Ford doubled down on the F-150, the most profitable vehicle in its portfolio. GM reconsidered its planned EV expansion. Stellantis, the struggling conglomerate formed from the merger of Fiat Chrysler and PSA, saw a lifeline—they could survive longer by making what's profitable now rather than what's necessary tomorrow.

The manufacturers publicly claimed this was breathing room for R&D. Better to let us build profitable gas vehicles now, they said, and we'll continue investing in future EV technology. The unspoken truth: they have no intention of building EVs in volume if they don't have to.

This is where the story becomes genuinely ominous. American automakers can now make a rational, profit-maximizing decision to return to gas vehicles. Their competitors—particularly in Europe and China—cannot. The European Union maintains strict emissions standards. China has committed to EV adoption targets. Japan and South Korea are building advanced EV platforms.

Meanwhile, American automakers can now legally optimize for the American market, which currently prefers trucks and SUVs (gas-powered ones, given the tax credit elimination). They have no pressure to build forward-looking technology for export markets.

The result: a two-tier automotive world. America builds profitable trucks for Americans. Everyone else builds electric vehicles for global markets.

Global Competition: Chinese Automakers Are Coming

While American automakers scramble backward toward gas vehicles, the rest of the world is accelerating forward.

Chinese manufacturers—companies most Americans have never heard of—have launched EV programs with features and price points that make Detroit's offerings look primitive. BYD has become the world's largest EV manufacturer. Li Auto, XPeng, and others are producing sophisticated vehicles with advanced software, AI capabilities, and price tags that undercut Tesla.

These companies were never hampered by the dealer problem. They never built 30 years of gas-car-dependent supply chains. They entered the automotive market without legacy baggage, specifically targeting the EV transition.

Most remarkably, they're now looking at American markets. Federal regulations currently prohibit Chinese automakers from selling in the US, but as American regulations collapse, the argument for those prohibitions weakens. If the US has no environmental standards, no emissions requirements, and no competitive advantage in EV technology, what exactly justifies keeping out manufacturers who produce superior electric vehicles at lower prices?

The answer, of course, is national security and trade policy. But those are fragile justifications if American consumers can buy a better EV from a Chinese manufacturer for $15,000 less than an American Tesla or GM vehicle.

European manufacturers are in a slightly different position. They still face EU emissions standards that require EV production. They're investing in battery technology and EV platforms seriously. The Volkswagen Group, BMW, Mercedes—these manufacturers are building competitive EVs for global markets. Some of these vehicles are coming to America, where they compete directly with Detroit and Tesla.

Meanwhile, American manufacturers are retreating to gas vehicles because they can. This creates a vicious cycle: less investment in EV technology means falling further behind in a market that's still growing globally. Less global presence in EVs means less leverage in international negotiations and less ability to attract talent in the fastest-growing automotive segment.

The longer game is genuinely concerning. In 10 years, the global automotive market will be dominated by companies that made the right bets on electrification now. American companies that retreated to gas vehicles because of short-term political pressure will be competing in a niche market while everyone else owns the future.

That's not speculation. That's math. If you don't have volume manufacturing experience in EVs, if you don't have battery supply chains, if you don't have the software talent to build competitive autonomous systems, you can't suddenly scale up in a decade. These advantages are built year by year, investment by investment.

Detroit's remaining choice is unpalatable: either commit fully to EVs despite the regulatory rollback and political headwinds, or retreat to gas vehicles and accept that in 15 years they'll be manufacturers of specialty vehicles for a shrinking American market.

Tesla holds an estimated 60% of the American EV market, showcasing its dominance over legacy automakers and new entrants. Estimated data.

The Tesla Dominance: Understanding the Unbridgeable Gap

Tesla owns the American EV market. Not competitively. Dominantly. It's not even close.

There are a few reasons why this happened, and understanding them explains why the gap probably can't be closed by legacy automakers.

First: Tesla built a company around EVs from the beginning. Every decision—manufacturing, supply chain, software development, retail, service—was optimized for electric vehicles. No legacy systems to drag along. No gas-car platforms awkwardly adapted to batteries. Everything was purpose-built.

Second: Tesla committed to manufacturing scale earlier and more aggressively. When Elon Musk said Tesla would make a million cars a year, the industry laughed. Then Tesla did it. This required solving manufacturing challenges at speed that traditional automakers solve over years. Tesla moved faster because it had to. It built muscle memory in scaling production.

Third: Tesla owned its entire supply chain vertically. It builds its own batteries (in partnership with Panasonic, LG, and CATL, but with massive in-house capability). It makes its own motors. It produces its own semiconductors. When chip shortages devastated the industry in 2021-2023, Tesla had its own supply. Everyone else was waiting for parts.

Fourth: the software. Tesla's vehicles improve through over-the-air updates. New features arrive without a dealer visit. Performance improves. Range increases. Competing vehicles get the features that existed on day one for the vehicle's entire lifespan. This creates a psychological sense that Tesla vehicles are constantly improving while others stagnate.

Fifth: charging infrastructure. Tesla bet on its own network. The Supercharger network is now opening to other EVs, but for years it was a Tesla exclusive. A Tesla owner could take a road trip with confidence. Owners of other EVs faced uncertainty about charging availability. This mattered in the purchase decision, even though it's becoming less relevant as networks improve.

Sixth: brand confidence. This might sound intangible, but it's not. When you buy a Tesla, you're buying from a company that's proven it can scale EV manufacturing, that has profitable operations, that doesn't need subsidies to survive. Legacy automakers were selling vehicles from companies that were losing billions on EVs. Why would you bet your money on their vision when Tesla's was already proven?

Seventh: the actual performance. A Tesla Model 3 and a Chevy Bolt EV might both be good cars. But the Model 3 has better acceleration, a better driving feel, and better software. It's not just better on paper—it's better to drive. When you test-drive them, you feel the difference. That feeling matters.

Can legacy automakers catch up? In theory, yes. They have more capital, more manufacturing capacity, more dealer networks. They could theoretically outspend and out-manufacture Tesla. But not if they keep one foot in gas vehicles. You can't build a competing EV company from within a company optimized for gas vehicles. The culture, the engineering talent, the manufacturing expertise, the supply chains—they're all oriented the wrong way.

Ford, to its credit, tried this with Ford Blue—a division focused exclusively on electric vehicles. But Ford Blue still shares engineering resources with the rest of Ford. It still competes for capital with gas vehicle programs. It still operates within organizational structures built for different vehicles.

GM is attempting the same with its EV initiative. Same structural problems.

Until a legacy automaker completely separates its EV business, gives it total autonomy, and commits to it fully regardless of gas vehicle profitability, it can't truly compete with Tesla. And the regulatory and political environment now makes that commitment impossible.

Market Shift: The Psychology of Consumer Preference

It's tempting to say American consumers prefer gas vehicles and that's why the EV transition is failing. But that's backwards causality.

Consumers prefer what's available, what's well-made, and what they can afford. When Detroit offered expensive, underwhelming EVs, consumers preferred Tesla. When the government removed the tax credit, expensive vehicles became prohibitively expensive. When politicians made EVs politically toxic, voters who identified with those politicians became skeptical.

This is the sequence that matters: first came the supply (bad EVs from Detroit). Then the access (tax credit removal). Then the politics (anti-EV messaging). Then the preference (consumers say they prefer gas vehicles).

It's not that Americans fundamentally dislike EVs. Early EV adopters—tech-forward consumers, environmentally motivated consumers, people who could afford them—loved EVs. They were thrilled with the technology, the performance, the experience.

But you can't build a mass market on enthusiasts. You need vehicles that work for average people at affordable prices. For a moment, it looked like that was happening. Then the credit disappeared, prices rose, and the market froze.

There's also a regional component. EV adoption has been highest in states with charging infrastructure (California, New England, the Pacific Northwest). It's been slowest in areas without infrastructure (rural America, the South). This isn't about preference—it's about practicality. If you live in Wyoming and there's one charging station in your town, an EV isn't a practical choice regardless of how well it's engineered.

But instead of Detroit investing in this infrastructure gap, they used it as an excuse not to build competitive EVs. "People don't have charging," they said. "So they don't want EVs." The logical response would have been: "If we build better EVs and charging infrastructure matures, demand will follow." Instead, the auto industry's position was: "Until infrastructure is perfect, we're not building competitive vehicles."

This is the circular logic that killed the American EV transition. Demand won't come until infrastructure is ready. Infrastructure won't be ready until demand is there to justify investment. So everyone waits, and nothing happens until someone (Tesla) breaks the circle by investing in both.

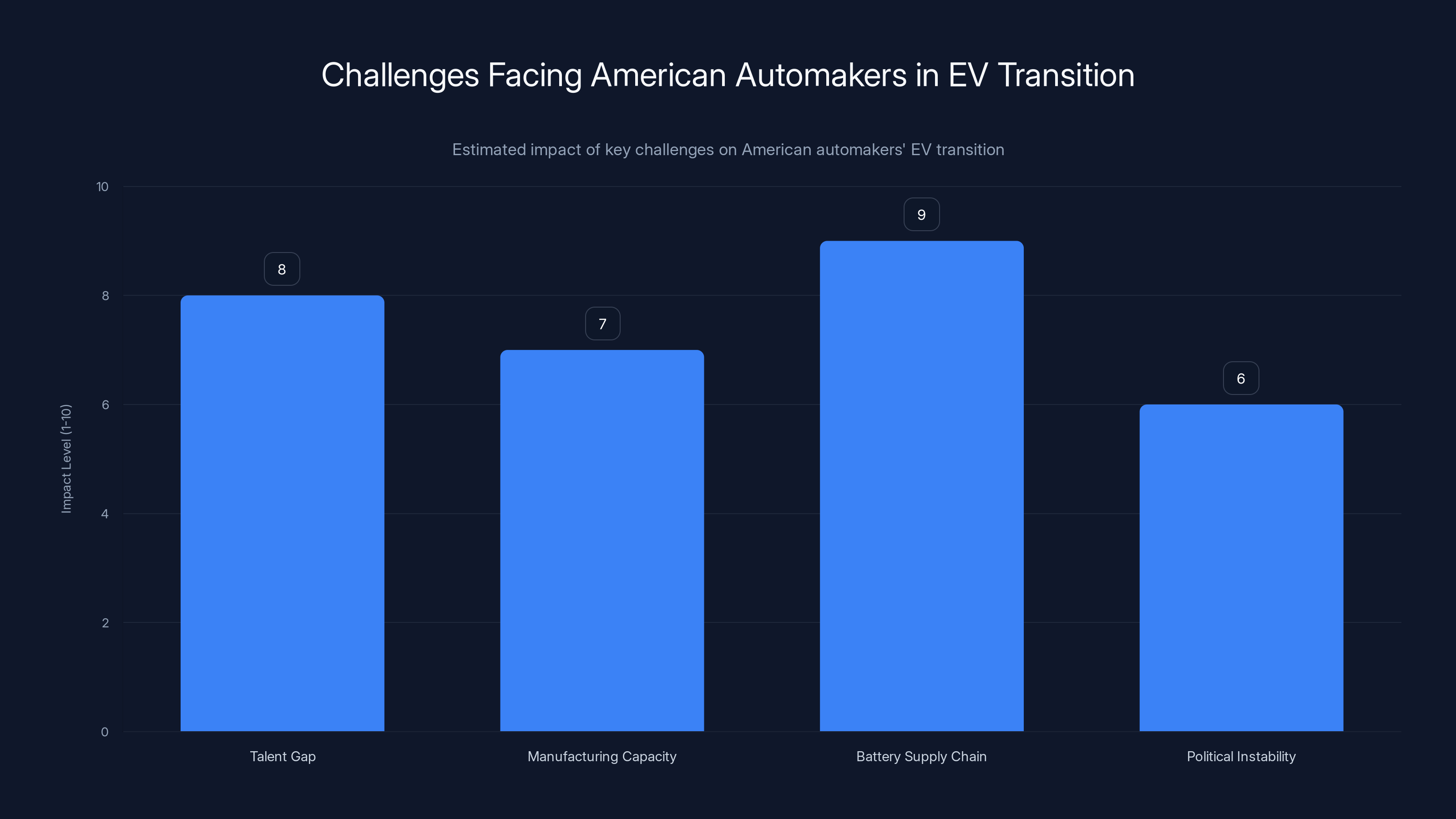

Estimated data shows the battery supply chain as the most significant challenge, followed by talent gap and manufacturing capacity. Political instability also poses a considerable risk.

The Path Forward: Can America Recover?

The optimistic framing says this is just a pause. A temporary retreat. That eventually consumer preferences will shift, regulations will change again, and American automakers will make their move back toward EVs with renewed commitment.

But that's probably fantasy. Here's why.

First, the talent has moved. The best engineers in automotive now work for Tesla, for Chinese EV manufacturers, for European brands pivoting to EVs. If Detroit starts hiring, they're hiring people trained in gas vehicle engineering or, at best, people leaving companies that are ahead of them. Building institutional knowledge in EV engineering takes years. Detroit has a gap it might not be able to close.

Second, the manufacturing advantage erodes. Tesla is now a manufacturing beast. Its Gigafactories are coming online globally. Chinese manufacturers are building plants at a pace Detroit can't match. By the time American automakers decide to take EVs seriously again, the capacity advantage they once had will be gone.

Third, the battery supply chain. Battery manufacturing is becoming competitive advantage itself. Tesla is integrating battery production. Chinese companies are controlling battery supply. America doesn't have a dominant battery manufacturer. Detroit would have to partner with international suppliers or build new capacity, which takes years and capital they might not commit.

Fourth, the political environment is unstable. If the current administration is anti-EV, the next might be pro-EV again. Manufacturers can't plan around this. "Maybe we'll invest heavily in EVs when regulations change" is not a business strategy. It's indecision.

There's one path where America stays relevant: Detroit completely spins off its EV division, funds it independently, removes it from the gas vehicle profit center, and let it compete on its merits without needing to protect gas vehicle sales. Make it a separate company with separate leadership, separate incentives, and separate capital allocation. Basically, create a Tesla competitor from scratch.

Would that work? Maybe. But it requires admitting that the current organizational structure can't produce competitive EVs, and that level of internal disruption is hard to justify to a board of directors focused on short-term profitability.

Most likely outcome: American automakers continue the slow retreat. They make money on gas vehicles for as long as possible. They develop EVs at reduced pace. The market share, the technology leadership, and the manufacturing expertise all shift to competitors. In 20 years, "Made in America" automotive becomes a nostalgic phrase about a previous era.

That's not inevitable. But it's the base case if things continue as they are.

What International Markets Are Doing Right

While America faltered, other countries accelerated.

The European Union maintained emissions standards, which created regulatory pressure for manufacturers to produce EVs. Companies that wanted to sell in EU markets had to build electric vehicles, had to develop battery technology, had to hire EV expertise. The result: European manufacturers like Volkswagen, BMW, and Mercedes developed serious EV programs and have vehicles that compete with Tesla on features and price.

Scandinavia went further. Norway, Sweden, and Denmark offered purchasing incentives, invested in charging infrastructure, and prioritized sustainability in transportation policy. The result: over 80% of new vehicle sales in these countries are now electric. Not hybrid. Electric. Complete transition.

China recognized early that EV manufacturing would be a core strategic industry and invested accordingly. Government support for battery manufacturing, EV startups, and charging infrastructure. The result: China produces more EVs than any other country and has companies (BYD, NIO, XPeng) that are globally competitive or about to be.

Japan, initially skeptical of BEVs (battery electric vehicles), has invested in hydrogen and hybrid technology but is also developing serious EV programs. Toyota's slow start on EVs is now being corrected, though they're probably permanently behind in the race.

The lesson is consistent: countries that committed to EV transitions, stayed committed, and provided infrastructure support built competitive industries. Countries that vacillated, didn't invest in infrastructure, and allowed political winds to shift ended up behind.

America had the chance to be a leader. It had the technology, the companies, the resources, and the head start. Instead, it had a false choice: either you produce EVs or you stay profitable. That wasn't actually the choice. The choice was whether to invest for the future or milk the present.

Every manufacturer faced the same choice. Tesla chose the future. Everyone else chose the present. The results are now baked in.

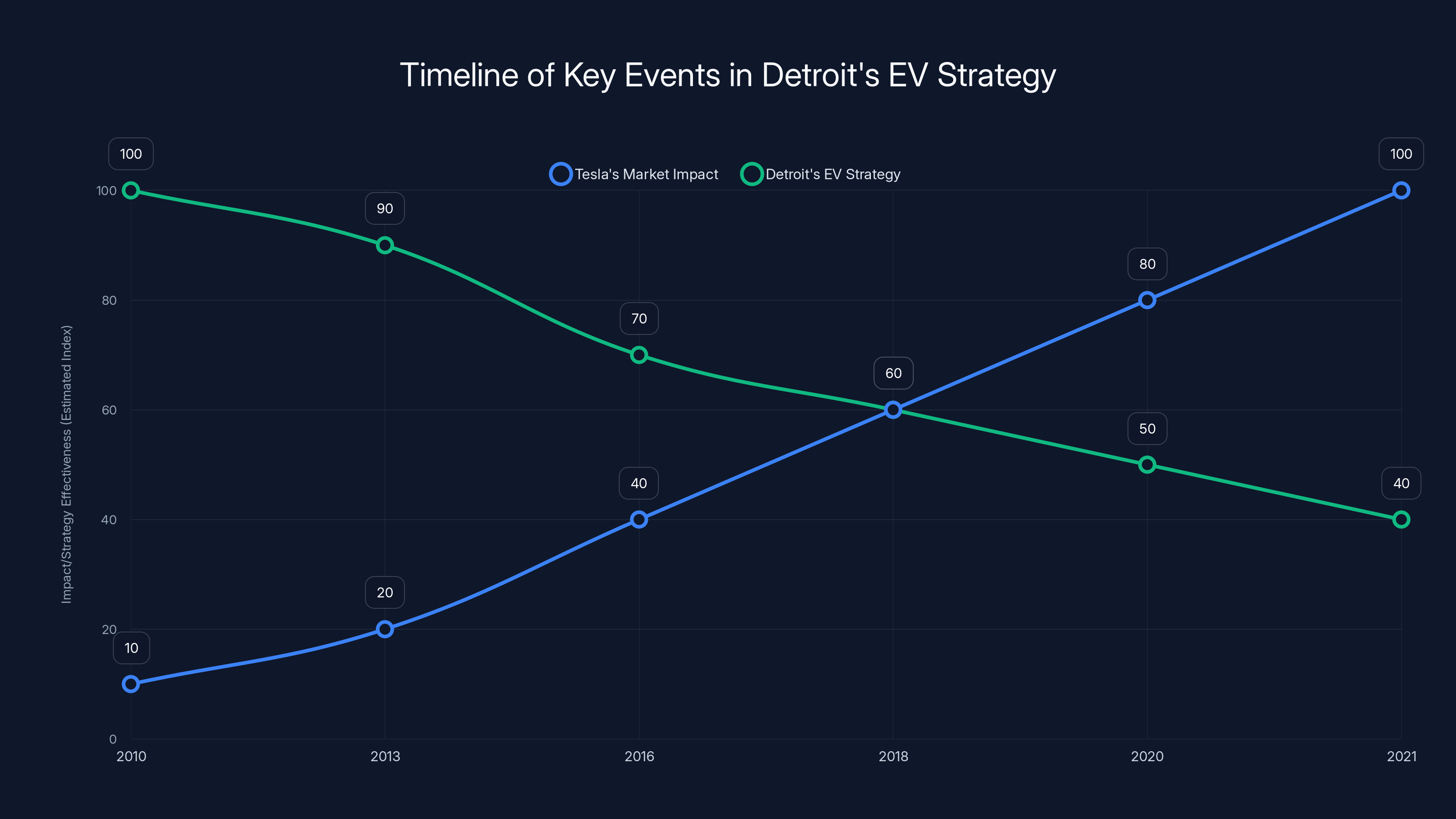

The timeline shows Tesla's increasing market impact from 2010 to 2021, while Detroit's EV strategy effectiveness declined due to strategic missteps. Estimated data.

The Autonomous Vehicle Angle: Another Advantage Lost

Here's a detail that rarely connects: autonomous vehicle development is deeply linked to EV manufacturing and software expertise.

Building autonomous vehicles requires multiple skill sets: hardware engineering, software development, data science, real-world testing, regulatory navigation. These skills are clustered in companies building EVs because EVs have more complex software requirements than gas vehicles.

Tesla's autonomous driving capability, whatever its limitations, is built on years of EV development. The same batteries, motors, and electrical systems that power EVs provide the infrastructure for autonomous systems. The software engineers who optimize EV performance are the same engineers who build autonomous capabilities.

Waymo, Alphabet's autonomous vehicle division, spent years testing with Jaguar vehicles but is now transitioning to purpose-built EVs. Cruise (General Motors' autonomous division) was building autonomous Chevy Bolts before GM killed the Bolt. You can't test autonomous driving with gas vehicles at scale—the infrastructure and software expertise don't align.

As American manufacturers retreat from EV development, they're simultaneously undercutting their autonomous vehicle programs. The companies that master EV manufacturing, battery technology, and EV software will have a built-in advantage in autonomous vehicles. The companies that retreat to gas vehicles will find themselves trying to bolt autonomous capabilities onto platforms never designed for them.

This is a compounding disadvantage. Missing the EV transition doesn't just cost you today's market. It costs you the infrastructure for tomorrow's technology.

Tesla's Robotaxi program, Waymo's expansion into robotaxi services, Chinese EV manufacturers' autonomous driving features—these are all emerging from companies that built serious EV programs. Detroit's autonomous vehicle programs will find themselves competing on technology developed by their EV competitors, with less depth of expertise and more integration complexity.

The Cost Structure Problem: Why Detroit Can't Price Competitively

Here's an uncomfortable truth for Detroit: they can't build EVs as cheaply as their competitors.

Not because of manufacturing incompetence. Not because of bad engineering. Because of legacy cost structures.

An American automotive worker earns an average of $60,000+ annually with benefits adding another 40-50%. That's not a complaint—it's the result of generations of union negotiations and is mostly justified. It's what competitive wages look like in America.

But those labor costs apply whether you're building a profitable gas truck (

Tesla has lower labor costs (less unionized), but more importantly, Tesla built its manufacturing around EVs from the beginning. Every process, every tool, every step was optimized for that specific vehicle type. Detroit optimized its factories for gas vehicles, then tried to adapt them for EVs. The adaptation is inefficient.

Chinese EV manufacturers don't have America's labor costs or infrastructure costs. They can build a competitive EV at lower price. As they scale, they'll achieve price advantages American companies can't match.

This creates a structural profitability problem. To compete on price with Chinese manufacturers, Detroit would need to either reduce labor costs (politically and practically impossible) or achieve dramatic manufacturing efficiency gains (harder than it sounds). Or they accept lower margins on EVs and fund them with gas vehicle profits. But they can't fund EVs indefinitely if they're losing money on every unit sold.

At some point, the math breaks. Either EVs become profitable or manufacturing capacity gets pulled back to gas vehicles.

Given the regulatory environment now permits gas vehicles, the pull is all toward what's profitable. Detroit faces a question it doesn't want to answer: "Can we build competitive EVs at a profit?" The preliminary answer seems to be no.

Political Economy: How Market Forces Got Overridden

This story is ultimately about politics overriding markets.

If you leave it to market forces, manufacturers respond to consumer demand and regulatory pressure. Tesla proved demand existed. Regulations pushed manufacturers toward EVs. The market response should have been accelerating EV production.

Instead, the Trump administration reversed course. The endangerment finding was rescinded. The tax credit was eliminated. Emissions standards were gutted. Political calculation trumped market signals.

Why? Several factors converge. One, environmental regulation became a partisan issue. Republicans branded climate and emissions concerns as anti-energy, anti-American. Deregulating emissions became a political win, even though the actual consequences—declining American automotive competitiveness—were clearly not in America's interest.

Two, nostalgia for an idealized past. Gas vehicles are seen as an American symbol—pickup trucks, powerful engines, freedom of the road. Regulations that push toward EVs feel like an encroachment on American identity and liberty. This is psychologically powerful even when it's economically self-defeating.

Three, short-term thinking. For politicians, a five-year horizon is a lifetime. Long-term competitiveness in global automotive markets doesn't register on that scale. Immediate regulatory relief for manufacturing feels like a win.

Four, lobbying. Automakers, dealers, oil companies, and other interested parties spent considerable effort opposing emissions regulations. When the regulatory landscape shifted in their favor, they didn't object.

What's remarkable is how quickly the industry pivoted from "we're committing to EV transition" (positioning for a regulated future) to "actually, we need breathing room" (exploiting a deregulated present). The cynicism is obvious, but the outcome is clear: you can't build a long-term strategy when the regulatory environment shifts on a five-year cycle.

The Talent and Innovation Exodus

One of the less visible but most consequential impacts: the best people are leaving.

Over the last five years, some of the sharpest engineering talent in America left legacy automakers for Tesla, electric startups, and tech companies. Why? Opportunity, mission, the chance to work on cutting-edge technology, and the belief that their work mattered for the future.

Then the regulatory environment reversed. Suddenly, those who'd left Detroit for Tesla were vindicated, and those still at Ford or GM began asking why they were optimizing gas vehicles when the future was somewhere else.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle. Detroit loses engineers → engineering becomes less advanced → products are less competitive → more engineers leave. At some point, the institutional knowledge gap becomes unbridgeable. You can hire people, but you can't instantly transfer 20 years of EV engineering expertise.

China has been aggressively recruiting automotive talent from around the world, offering high salaries, stock options, and the chance to build new companies from the ground up. American engineers are moving to Chinese startups because the opportunities feel more significant.

Meanwhile, America's best automotive talent is increasingly concentrated at Tesla, a company that's not part of Detroit and doesn't depend on traditional automotive expertise.

When historians look back at this period, they'll probably identify this talent exodus as the moment it became structurally impossible for Detroit to recover. You can rebuild manufacturing capacity. You can refocus product strategy. You can't rebuild human capital once the best people have left and won't come back.

Why Predictions of a Comeback Are Probably Wrong

You'll hear optimistic forecasts: "The Big Three have deep pockets. They'll invest heavily in EVs and catch up." Or: "In five years, new platforms will be ready and Detroit will be competitive." Or: "They learned their lesson and will make better decisions going forward."

All possible. All unlikely.

Here's why. When Ford announced the $19.5 billion write-down, it wasn't taking money out of reserves and investing in new EV programs. It was acknowledging losses and reallocating capital away from EV investments back toward profitable gas vehicles. That's the opposite of a comeback strategy.

When GM took its $7.6 billion charge, it paired it with statements about "taking a more flexible approach" to the EV transition. That's a euphemism for "we're slowing down."

When Stellantis took its $26.6 billion charge, it simultaneously announced partnerships to develop gas engines. That's not a company betting on the EV future.

These write-downs free up capital that could be used for new EV investments. But the tone and the structural decisions suggest it won't be. The companies are reorienting toward what's profitable, which is gas vehicles. The technology race is over. Tesla won.

The path to a comeback would require:

- A CEO willing to make long-term bets against short-term profits

- A board willing to accept lower returns for years while EV programs scale

- Regulatory environment that rewards EVs (currently the opposite)

- A product that's as good or better than Tesla in the eyes of consumers

- Commitment to separate the EV business so it's not cannibalized by gas vehicle profits

- Years to build it

That list is so improbable that it's almost harder to imagine happening than it is to imagine Detroit continuing to retreat.

The most likely outcome is managed decline. Detroit remains huge in absolute terms—it still sells millions of vehicles. But the future of the industry, the growth segments, and the technological frontier move elsewhere. America stays a significant automotive player but stops being the leader.

What Could Still Change Things

There are scenarios where this timeline gets disrupted. They're mostly political or regulatory.

Scenario one: A future administration reverses the current course. Reimplements emissions standards. Reinstates the tax credit. Creates regulatory pressure for EVs again. This would force manufacturers back into the EV race. Possible, but by then the technology and manufacturing advantage will have shifted so far that catching up becomes even harder.

Scenario two: Battery technology improves so dramatically that EVs become cheaper than gas vehicles without subsidies. This happens in, maybe, five to seven years. At that point, cost advantage alone drives adoption. But by then, the manufacturers making the best batteries won't be American.

Scenario three: Autonomous vehicles become viable and valuable enough to drive transportation transformation. Companies leading in autonomous driving (Tesla, Waymo, Chinese startups) become the dominant players in the next-generation vehicle market. Detroit's autonomous programs, underfunded and struggling, get marginalized. This seems most likely.

Scenario four: Global market pressure forces action. If European, Chinese, and Japanese EVs dominate global markets, American consumers see that American companies are falling behind. Pressure mounts for a national manufacturing strategy. This has happened before (the space race, for instance) but requires political consensus that doesn't currently exist.

Most likely: none of these scenarios fully materialize. The American automotive industry continues building gas vehicles, gradually shrinking as a percentage of global automotive output, until in 20 or 30 years it's a niche player making vehicles for a shrinking domestic market.

The irony would be exquisite. America invented the assembly line and made cars a mass-market product. A century later, we're a customer of technology rather than a leader.

The Bigger Picture: Industrial Competitiveness and National Interests

Strip away the technical details and the auto industry story becomes a story about American industrial decline.

The automotive industry is massive—directly employs 1.7 million Americans, supports millions more in supply chains and services. The technology that flows from automotive innovation (batteries, electric motors, autonomous systems, AI) has applications across entire economies. A decline in American automotive competitiveness isn't just about cars.

It's about whether America remains a leader in advanced manufacturing, whether American companies can compete in emerging technologies, whether American workers have access to high-paying jobs in growing industries.

When China builds better EVs at lower cost, they're not just winning market share. They're building expertise that translates to batteries for phones, grid storage, aerospace applications. They're developing software and AI capabilities that have broader applications. They're training engineers and manufacturing workers who understand the technologies of the future.

America, meanwhile, is retreating to profitable but mature technology. That's a losing strategy over decades.

The political response has been to blame the market, to blame environmental regulation, to blame consumers. The actual problem is that American companies made bad decisions and regulators shifted those decisions from long-term strategy to short-term politics.

Fix it? The window is probably already closed. What could have been fixed in 2015 or 2016 with serious EV investment is much harder to fix in 2025 after five years of losses and talent exodus. What could have been fixed with sustained regulatory pressure will be harder after deregulation removed the incentive.

We'll see if the Biden administration's successor is smarter about this. For now, we're watching the American auto industry become a regional player in a global market.

Why This Matters Beyond Detroit

If you don't care about cars, you should still care about this story because it's a template for how America can lose technological leadership.

Legacy companies underestimate disruption (check). Political interests override market signals (check). Short-term profits are prioritized over long-term positioning (check). Regulatory reversals destroy strategic certainty (check). Talent moves to competitors (check). American companies find themselves dependent on foreign technology and suppliers (check).

This isn't unique to automotive. The same pattern is playing out in batteries, in solar manufacturing, in semiconductor manufacturing, in biotechnology. Wherever there's a transition from mature technology to emerging technology and political pressure to defend the mature tech, America tends to slow down while competitors accelerate.

The EV transition was supposed to be America's moment. Tesla proved the market existed. Regulatory frameworks pushed manufacturers toward EVs. American consumers had rising incomes and education that made them likely early adopters. Every structural advantage pointed toward American leadership.

Instead, we're becoming followers. That matters because it's not just about this cycle. It's about whether America has the organizational and political capacity to lead in the next technological transition. If we can't manage the EV transition, what about the next one?

FAQ

What caused Detroit's EV failure?

Detroit made multiple compounding mistakes: they underestimated Tesla's potential, delayed EV development for years while betting on gas vehicles, built expensive and underwhelming electric vehicles, allowed dealer networks to actively work against EV sales, and failed to build the software and user experience that consumers expected. When they finally committed to EVs, Tesla already dominated the market and had structural advantages Detroit couldn't overcome.

How much have American automakers lost on EVs?

Ford took a

Why did the EV tax credit removal matter so much?

The $7,500 tax credit was closing a price gap between EVs and gas vehicles. When it was eliminated in early 2025, the market froze. General Motors reported a 43% decline in EV sales in the quarter immediately following. Without the credit, expensive vehicles became even more expensive, and consumers defaulted to cheaper gas alternatives.

What's the endangerment finding and why did its rescission matter?

The endangerment finding is the legal determination that greenhouse gas emissions pose a threat to human health, which gave the EPA authority to set emissions standards for vehicles. When the Trump administration rescinded it in February 2025, emissions standards effectively disappeared, removing regulatory pressure for automakers to build electric vehicles. Manufacturers now have permission to focus on profitable gas vehicles indefinitely.

Can Tesla be caught?

Unlikely. Tesla has structural advantages that legacy automakers can't replicate while maintaining their gas vehicle businesses: manufacturing optimized for EVs, vertical integration in battery production, software talent, brand confidence, and a charging network. Legacy automakers trying to compete while protecting gas vehicle profits face organizational conflicts that Tesla doesn't. By the time a legacy automaker could build a truly competitive EV program, they'd have fallen so far behind that catching up would be nearly impossible.

What happens to American automotive manufacturing now?

Most likely, American manufacturers continue making gas vehicles for domestic and international markets while gradually losing market share in EVs and emerging automotive technology (autonomous vehicles, software, advanced batteries). Over decades, the US becomes a regional player in global automotive rather than a leader. Foreign manufacturers (primarily Chinese and European) dominate growth segments. American workers lose access to high-paying jobs in emerging automotive technology.

Why does this matter beyond cars?

Automotive manufacturing is a template for technological transitions. How America manages the EV transition signals whether American companies can lead in other emerging technologies. If legacy manufacturers can't adapt, if political interests override market signals, and if regulatory certainty is lost every five years, then America will likely lag in other technological transitions too. This is about industrial competitiveness and American leadership in emerging technologies, not just about vehicles.

What could fix this?

Structural solutions would require a legacy automaker to completely separate its EV business from gas vehicle operations, give it autonomy, fund it independently, and commit to it regardless of gas vehicle profitability for a decade. Regulatory solutions would require reimposing emissions standards that create pressure for EV production. Market solutions would require EV technology to become so superior and affordable that gas vehicles become obsolete. Of these three, only the market solution doesn't require unrealistic institutional change, and it probably takes 5-10 more years to arrive. By then, most of the damage is done.

How are other countries handling EVs?

Europe maintains strict emissions standards that require manufacturers to produce EVs, so European companies developed serious EV programs and competitive vehicles. China invested heavily in battery manufacturing and EV startups early, and now dominates EV production and has globally competitive companies. Scandinavian countries offered purchasing incentives and invested in charging infrastructure, achieving 80%+ EV adoption rates. Japan was slow to embrace EVs but is now investing seriously, though behind the curve. America, lacking sustained regulatory pressure and now with regulatory support for gas vehicles, is retreating to the past.

Conclusion: When Market Leadership Becomes Market Irrelevance

It's hard to overstate how quickly dominance can evaporate.

Thirty years ago, the American auto industry was the gold standard globally. Fifty years ago, American cars represented more than half of global automobile production. We invented the assembly line. We perfected mass manufacturing. Detroit was synonymous with automotive innovation.

Then we fell asleep during the most significant technological transition in automotive history. Not because we lacked the resources or capability. Because we made the wrong strategic decisions, tolerated misaligned incentives, let politics override markets, and waited too long to act.

Tesla is now an American company. If this were the 1950s, we'd celebrate this as an American triumph. Instead, it's evidence of how thoroughly Detroit missed the moment. One American company figured it out. The rest retreated.

The tragedy is that none of this was inevitable. There was no law of physics preventing Ford or GM from building great electric vehicles. There was no market force demanding that American companies lose EV leadership. There were choices. And at each decision point, the wrong choice was made.

Now the question isn't whether American automakers can catch up. That's probably impossible. The question is whether America can maintain industrial competitiveness in the automotive sector at all, and what that loss means for other industries where similar patterns might play out.

The American automotive industry's story is a cautionary tale. When incumbents face disruption, when short-term profit is prioritized over long-term positioning, when politics override markets, and when institutions move slowly while competitors move fast, dominance becomes irrelevance.

Detroit is learning that lesson now. The question is whether America as a whole learns it before the pattern repeats in other industries.

The future of American manufacturing wasn't determined by physics or economics. It was determined by decisions made in boardrooms and government offices in the years just passed. Those decisions are baked in now. The comeback isn't impossible, but the window to prevent the decline has closed.

That's the real cost of the EV transition we bungled. Not just the $50 billion in losses. The loss of a technological frontier that's already moving beyond the reach of companies that made the wrong choices when they mattered most.

Key Takeaways

- Detroit's 19.5B, Stellantis7.6B

- Tesla achieved dominance not through superior resources but through focus: building EVs from the ground up while Detroit adapted gas platforms inefficiently

- The elimination of the $7,500 EV tax credit and rollback of emissions standards destroyed regulatory incentives, causing GM EV sales to drop 43% in one quarter

- Dealer networks actively opposed EV sales because maintenance revenue—their profit driver—disappears with electric vehicles, creating internal opposition to manufacturer strategies

- American companies now face structural disadvantages against Chinese manufacturers building EVs without legacy gas-car supply chains and at lower labor costs

- Talent exodus from Detroit to Tesla and competitors created a capability gap that institutional knowledge alone cannot close in the remaining competitive window

- Global EV adoption continues accelerating outside America, with China commanding 60% of global EV sales while North America's share drops below 10%

Related Articles

- Rivian's Software Partnership Saves the EV Maker: 2025 Analysis [2025]

- Tesla Cybertruck Price Cuts: Why EV's Most Hyped Launch Became Its Biggest Flop [2025]

- New York Pulls Back on Robotaxi Expansion: What Happened and Why [2025]

- Apple iPhone Air MagSafe Battery Pack: Complete Guide [2025]

- Prediction Markets Battle: MAGA vs Broligarch Politics Explained

- Polestar's Station Wagon Strategy: How the EV Maker Is Challenging Tesla [2025]

![America's EV Crisis: How Detroit Lost the Electric Vehicle Race [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/america-s-ev-crisis-how-detroit-lost-the-electric-vehicle-ra/image-1-1771618078466.jpg)