Apple's iCloud CSAM Lawsuit: What West Virginia's Case Means [2025]

There's a lawsuit brewing that cuts straight to the heart of a debate that's been simmering in tech for years: how do you protect children without turning every smartphone into a surveillance device?

West Virginia Attorney General JB McCuskey just sued Apple, claiming the company deliberately made iCloud a haven for child sexual abuse material (CSAM). The lawsuit alleges Apple abandoned its plans to detect CSAM in favor of end-to-end encryption, essentially creating what McCuskey calls a "secure frictionless avenue" for distributing illegal content, as reported by CNBC.

This isn't some niche tech complaint. The implications ripple across privacy advocates, child safety organizations, device manufacturers, and regulators worldwide. Apple's in the uncomfortable middle: the company built its brand on privacy promises, but that same privacy architecture might be enabling real harm to real children.

Let's unpack what happened, why it matters, and where this case could lead.

TL; DR

- Apple abandoned CSAM detection in 2021 after massive backlash from privacy advocates, leaving iCloud without detection tools other platforms use, according to Bloomberg.

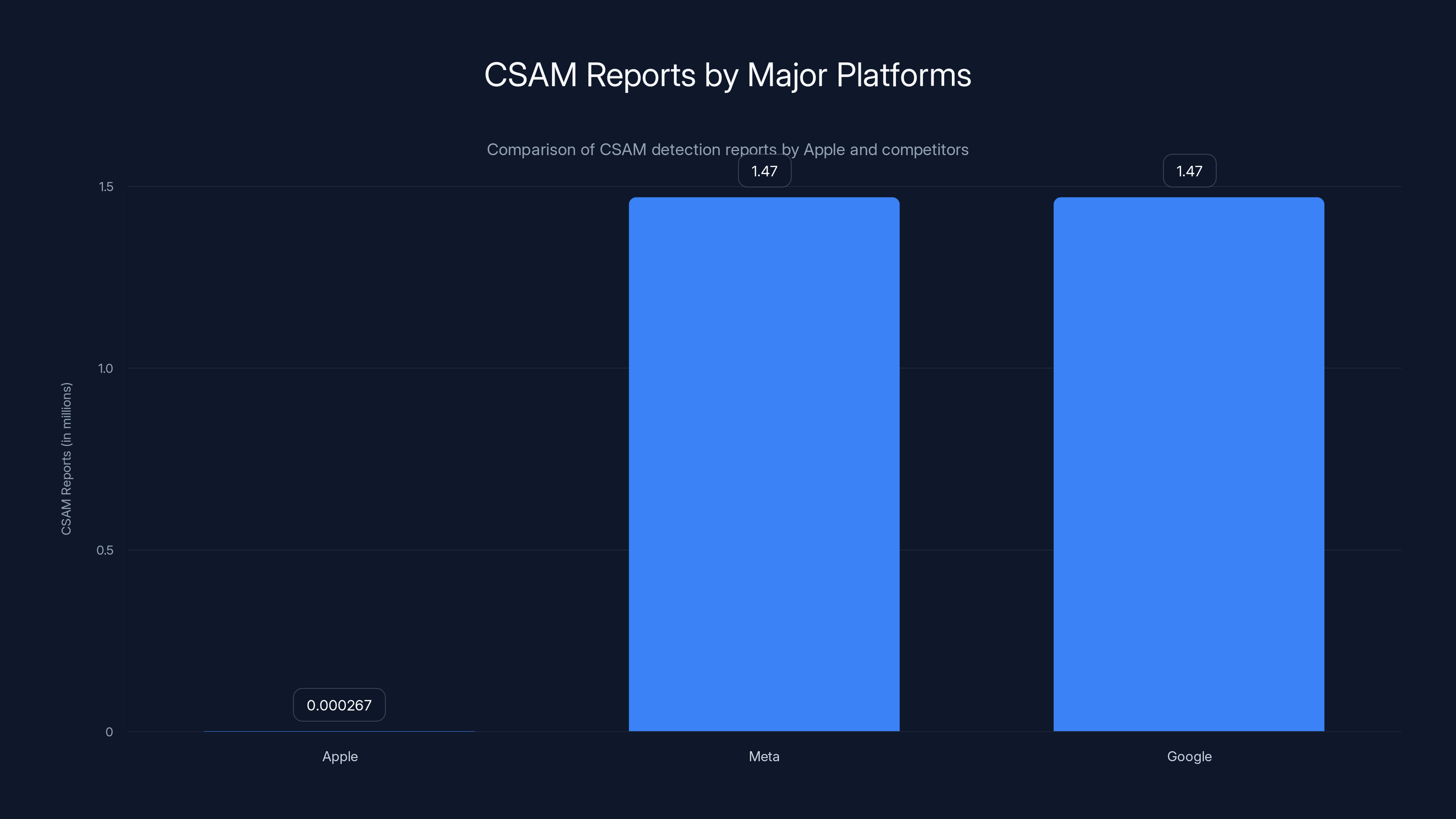

- West Virginia claims Apple made only 267 CSAM reports to authorities compared to Google's 1.47 million and Meta's 30.6 million reports, as highlighted by News.az.

- Internal Apple email alleged that iCloud is "the greatest platform for distributing child porn," according to the lawsuit, as noted by The Bull.

- No detection, massive scale: Apple's 2 billion+ devices create a vulnerable ecosystem vulnerable to abuse if encryption prevents detection.

- This case could force Apple to choose: add detection tools (breaking privacy promises) or face regulatory pressure and lawsuits across multiple states.

Apple reported significantly fewer CSAM cases compared to Google and Meta in 2023, highlighting a stark contrast in detection efforts.

The Original Plan: Apple's Abandoned CSAM Detection System

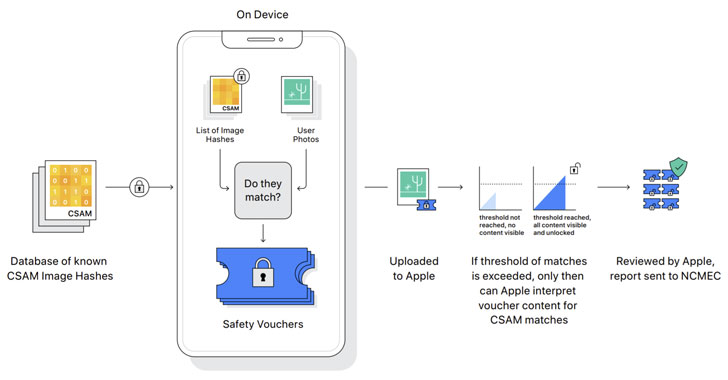

Back in August 2021, Apple announced something ambitious: a system to detect known child sexual abuse material in iCloud photos before they were even stored. The approach used neural matching technology to compare photos against a database of known CSAM images maintained by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC).

The technical framework was elegant in theory. Apple would scan photos on-device, match them against a hashed database of known CSAM, and flag matches before uploading to iCloud. The system included multiple layers of protection: hashing algorithms that made false positives nearly impossible, human review before any report went to authorities, and strict threshold requirements (over 30 matches) before escalation.

Apple's security head Craig Federighi explained the rationale to media: "Child sexual abuse can be headed off before it occurs. That's where we're putting our energy going forward."

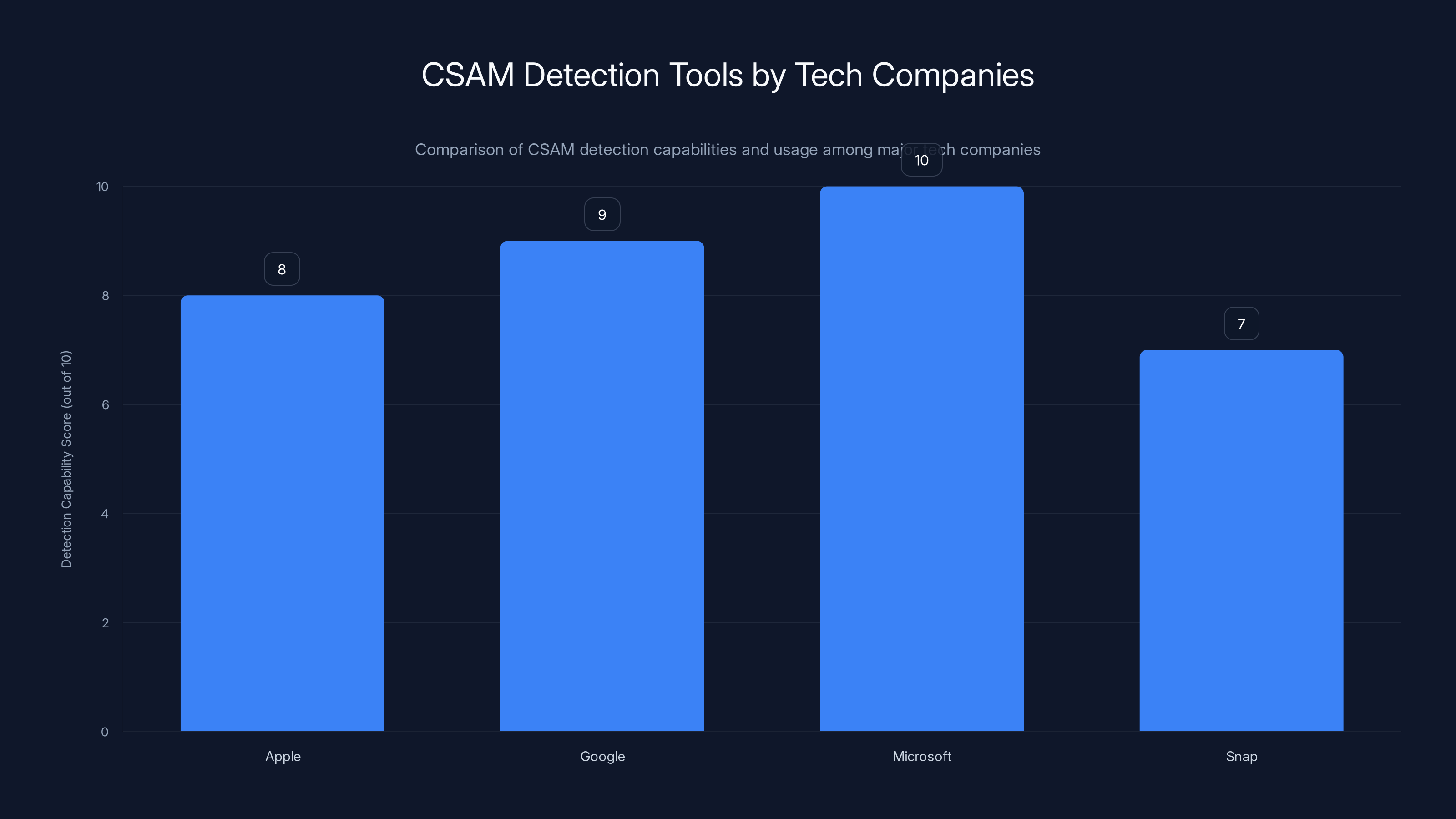

The company wasn't alone in this thinking. Google, Microsoft, Snap, and others already used CSAM detection tools like Microsoft's Photo DNA to catch and report abuse material.

But here's where the story takes a turn. Privacy advocates—including organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)—went nuclear. They argued that on-device scanning technology, even theoretically secure, created a backdoor precedent. If Apple could scan for CSAM, governments could demand scanning for political dissent, copyright infringement, or other content they deemed problematic.

A coalition of 90 civil rights organizations signed a letter opposing the plan. Researchers published papers questioning the security assumptions. Major tech figures warned that this would set a dangerous standard.

And it worked. Within a year, Apple shelved the project.

The Lawsuit: What West Virginia Actually Claims

Now, years later, West Virginia's Attorney General is arguing that Apple's retreat from CSAM detection was a mistake—not just a privacy decision, but an intentional abandonment of child protection.

The lawsuit makes several specific allegations. First, the numbers game: West Virginia points out that Apple made only 267 CSAM reports to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in 2023, while Google made 1.47 million reports, and Meta reported 30.6 million cases, as detailed by CNBC.

To put that in perspective: Apple has roughly 2 billion active devices worldwide, with hundreds of millions of users storing photos and files in iCloud. Yet it's flagging abuse material at a rate thousands of times lower than competitors who use detection technology.

Second, the lawsuit cites an internal Apple email. According to the filing, Apple's fraud head Eric Friedman allegedly wrote that iCloud is the "greatest platform for distributing child porn." This quote (if accurate) paints a picture of Apple being aware of the vulnerability while simultaneously taking no action.

Third, West Virginia argues that Apple "knowingly and intentionally designed its products with deliberate indifference to the highly preventable harms." This is a consumer protection claim, alleging that Apple's marketing as a privacy-first company while hosting massive amounts of abuse material constitutes deceptive practice.

The lawsuit also highlights Apple's selective child safety features. Apple does have parental controls, including tools that require kids to get permission before texting new numbers. It also introduced on-device scanning for nudity in iMessage for minors. But these are detection-free approaches—they don't flag abuse material, they just restrict usage or blur content.

McCuskey's argument: these measures don't address the core problem. They're like installing locks on windows while leaving the front door wide open.

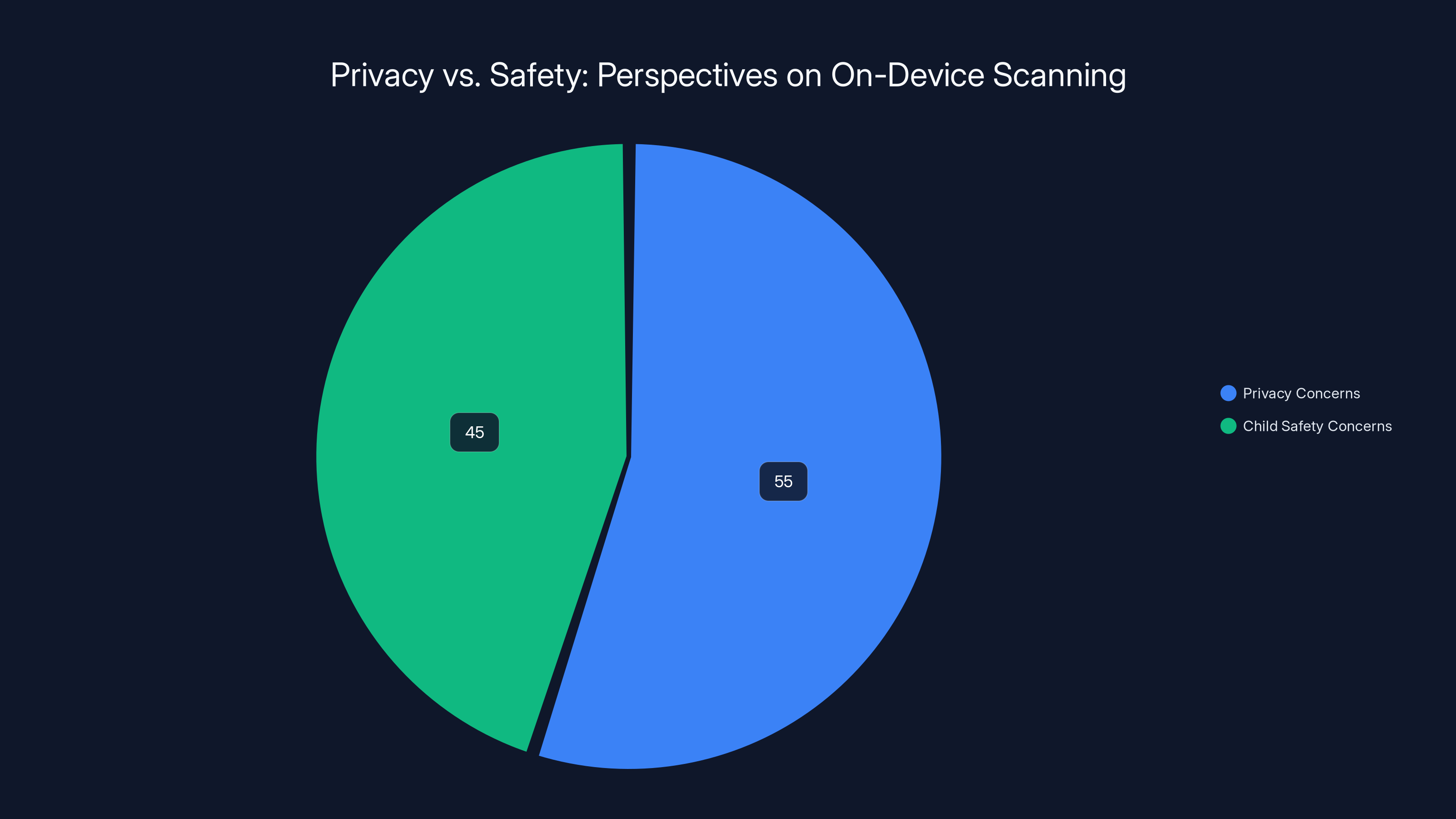

Estimated data shows a close split between privacy concerns (55%) and child safety concerns (45%) in the debate over on-device scanning. This highlights the complexity and balance needed in addressing both privacy and safety.

The Privacy vs. Safety Paradox

Here's what makes this lawsuit genuinely complicated: both sides have a point.

The privacy advocate perspective: Once you allow on-device scanning for CSAM, you've created infrastructure that could be repurposed. China could demand scanning for political dissent. The US government could demand scanning for copyright infringement. An authoritarian regime could demand scanning for LGBTQ content. The technical capability is the dangerous part, not the initial intent.

This isn't paranoid speculation—it's historical precedent. Every surveillance capability ever created has been expanded beyond its original purpose. Phone taps meant for organized crime got used for civil rights leaders. Antiterrorism databases got used for immigration enforcement. The pattern is consistent.

The child safety advocate perspective: Yes, that's a risk. But children are being harmed right now, in real time, with documented evidence. An estimated 4.3% of all child sexual abuse material involves children under 12. Every day the detection doesn't happen, more images are collected, more abuse continues, more children suffer permanent trauma.

They argue that the risk of technology misuse is abstract and preventable (through legislation and oversight), while the harm to children is concrete and happening today.

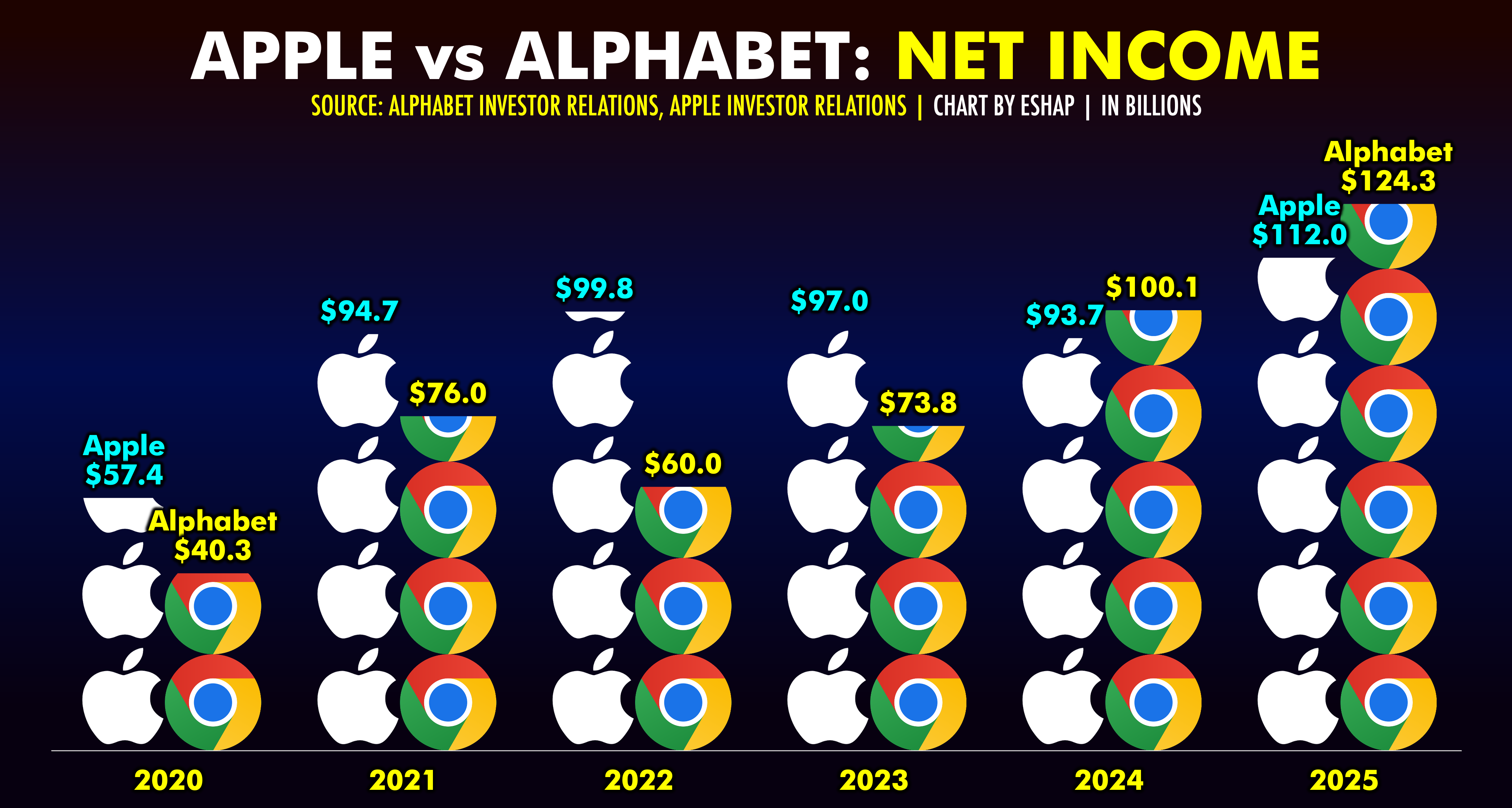

Apple's choice to embrace end-to-end encryption for iCloud is philosophically consistent with its brand positioning. The company spent years marketing itself as the privacy-forward alternative to Google (which scans email) and Microsoft (which scans OneDrive).

But there's a cost to that choice. And that cost, according to West Virginia, is being borne by children.

Why Apple's Numbers Matter

Let's dig into those reporting numbers because they're the actual evidence here.

When NCMEC receives a report of suspected CSAM, it comes from platform reports. A platform can only report what it detects. If you're not detecting, you're not reporting.

The platforms with the highest report volumes all use some form of detection:

- Meta (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp): 30.6 million reports using Photo DNA and custom AI systems

- Google: 1.47 million reports using Google's Content Safety API

- Snap: Hundreds of thousands using custom detection

- Reddit: Detection systems across uploaded content

- Apple: 267 reports, mostly from user flagging and manual reports

Now, you could argue: "Maybe iCloud just has fewer abusers." That seems unlikely given iCloud's scale. Statistically, if 2 billion devices store photos, and abuse material follows a normal distribution, you'd expect detection rates similar to other major platforms.

Apple's response to this has been limited. The company briefly said it was "investigating" CSAM concerns, but hasn't provided alternative detection methods or explained why 267 reports is adequate.

The Internal Email Problem

That quote about iCloud being "the greatest platform for distributing child porn" is potentially devastating to Apple's defense, if it's admissible in court and if the context supports how it's being used.

Lawyers will argue about context. Was Friedman expressing concern? Was he making a dark joke? Was he stating a fact that drives urgency?

But in the court of public opinion, it's already damaging. It suggests Apple's executives recognized the problem and did nothing.

This is where discovery (the lawsuit phase where both sides exchange documents and evidence) becomes critical. We'll likely see more internal emails, meeting notes, and communications between Apple leadership discussing CSAM, child safety, and encryption decisions.

Apple will argue it was responding to legitimate privacy concerns. McCuskey will argue Apple made a calculated choice to prioritize privacy marketing over child protection.

Apple's CSAM report numbers are significantly lower than Meta and Google, highlighting the impact of its end-to-end encryption policy on detection capabilities.

How Other Platforms Handle This

It's instructive to look at how the major platforms balance encryption and CSAM detection.

Meta/Facebook: Doesn't use end-to-end encryption for most services. Scans for CSAM using Photo DNA and custom AI. Made 30.6 million reports in 2023. The tradeoff: user data is visible to Meta for content moderation.

Google: Similar approach. Scans Gmail, Drive, and photos. Made 1.47 million reports. Also scans for other harmful content (abuse, harassment, etc.).

Snap: Uses detection tools. Also implements age verification and parental controls.

WhatsApp: Uses end-to-end encryption by default. Makes very few CSAM reports relative to scale. Prioritizes privacy over detection.

Signal: Pure end-to-end encryption. No content moderation. No reports.

Apple/iCloud: Hybrid approach. End-to-end encryption, but limited detection tools. Very low report numbers.

Apple's position is interesting because it's trying to have both: encryption (marketing as privacy-forward) without the tools that other encrypted platforms use.

WhatsApp, for comparison, is also encrypted but is owned by Meta, which has sophisticated offline detection capabilities and can subpoena decrypted data in law enforcement situations. Signal embraces encryption fully and accepts the tradeoff of not detecting anything.

Apple has tried to occupy middle ground and is being challenged on whether that middle ground is sufficient.

The Precedent Problem

If West Virginia wins this lawsuit, the implications cascade quickly.

First, other states will follow. McCuskey basically said this during the press conference: he expects other attorneys general to join. Once one state establishes a precedent that Apple's CSAM approach violates consumer protection laws, others will file similar suits.

Second, Apple will face regulatory pressure. The European Union's Digital Services Act already requires platforms to take action against illegal content. A lawsuit establishing that iCloud is inadequate could trigger EU enforcement action.

Third, Congress will pay attention. Child safety is one of the few tech issues with bipartisan support. If Apple loses this lawsuit, it becomes ammunition for bills requiring CSAM detection or making companies liable for abuse material hosted on their servers.

Apple could face a scenario where it's either:

- Add detection tools (which privacy advocates hate) to comply with lawsuits and regulations

- Implement end-to-end encryption more thoroughly (which child safety advocates hate) and accept not detecting anything

- Accept liability for CSAM hosted on iCloud and face significant legal consequences

None of these are good options. Which is why this lawsuit matters so much.

Apple's Actual Child Safety Features

To be fair to Apple, the company hasn't completely ignored child safety. It's just taken a different approach.

iMessage protections for minors: Apple added on-device scanning for nudity in photos sent through iMessage when the recipient is a minor. This doesn't detect CSAM specifically, but it tries to prevent grooming scenarios where adults send explicit images to children.

Parental controls: Apple's Screen Time and Family Sharing features let parents restrict what apps their kids can use, set downtime, and require approval for new contacts. This is proactive prevention rather than reactive detection.

Siri and App Store review: Apple reviews apps for child safety and removes known problem apps. It also built safety features into Siri to respond to abuse-related queries.

NCMEC partnership: While iCloud detection is minimal, Apple does maintain some reporting relationship with NCMEC.

The question West Virginia raises: are these enough? If 267 CSAM reports suggest they're not.

Meta/Facebook leads in CSAM reports with 30.6 million in 2023, while Signal reports none due to its strict encryption policy. Estimated data for Snap and Apple/iCloud.

The Technical Reality

Here's something important: implementing CSAM detection doesn't necessarily mean breaking encryption.

There are approaches that preserve encryption while enabling detection:

- On-device scanning (Apple's original plan): Scan locally before encryption, no server-side visibility

- Client-side hashing: Compare file hashes client-side, only send matches to servers

- End-to-end detection: Decrypt for the recipient only, scan on their device

- Metadata analysis: Detect patterns without analyzing actual content

The technical challenge is doing this without creating security vulnerabilities or false positives. It's hard, but it's not impossible.

Apple abandoned its project partly for technical reasons, but mostly for political ones. The privacy community made it clear that any on-device scanning technology would be rejected as a surveillance backdoor.

So Apple chose privacy as its differentiator. Now it's being sued for the consequences of that choice.

Where This Could Lead

Let's game out scenarios.

Best case for Apple: The court rules that privacy is paramount and that Apple has no legal obligation to detect CSAM. Apple continues current practices. No regulatory action. Other cases are dismissed.

Likely case: The court finds Apple's approach inadequate under consumer protection laws. Apple is ordered to implement detection tools or faces significant fines. Other states follow with similar suits. Apple settles and adds detection technology.

Worst case for Apple: Multiple states win. Federal legislation passes requiring detection. Apple is forced to add tools it actively opposes. Privacy advocates feel betrayed. Apple's brand as "privacy-first" is damaged.

Worst case for privacy: One win leads to aggressive expansion. Courts rule that any encrypted platform must have detection. Signal, WhatsApp, and other encrypted services face similar suits. Encryption becomes legally risky. Security for vulnerable populations decreases.

The real question: is there a middle ground that protects both?

Some experts suggest Apple could adopt a hybrid model:

- Keep iCloud encrypted by default

- Offer users the choice to enable abuse detection (opt-in)

- Use detection tools on opted-in accounts

- Maintain clear separation from other Apple products

But Apple hasn't proposed this. And privacy advocates would likely oppose it as window dressing.

The Global Dimension

This lawsuit isn't just US-focused. It has international implications.

The European Union is particularly aggressive on child safety. The EU's Digital Services Act already requires platforms to take action against illegal content. The proposed "Digital Services Act" would explicitly require CSAM detection and reporting.

Apple has more iPhone users in Europe proportionally than in the US. EU enforcement could be even more consequential than a US lawsuit.

Meanwhile, countries like China, India, and Russia are watching to see if democracies will demand backdoor access to encrypted services. They're hoping this lawsuit accelerates that trend.

For Apple, the global picture is complicated:

- US: Conservative on privacy, but increasingly focused on child safety

- EU: Aggressive on both privacy and child protection

- China: Doesn't care about privacy, wants access for political control

- India: Growing focus on content moderation

- Brazil: Recently passed strong content moderation laws

Apple has to thread a needle that might not have a center.

Estimated data shows Microsoft leading in CSAM detection capabilities, followed closely by Google. Apple's planned system was ambitious but faced privacy concerns.

The Business Implications

Beyond the legal case, there's real business risk here.

Apple's brand is built on privacy. The company uses privacy as a marketing differentiator against Google and Microsoft. "Your data is your data" is core to Apple's identity.

If Apple loses this lawsuit and has to implement detection systems, that brand positioning weakens. Competitors will point out that Apple isn't different—it's just like everyone else.

Conversely, if Apple wins and can claim that privacy is more important than CSAM detection, child safety advocates will use that against Apple in marketing and perception wars.

The reputational risk is real either way.

There's also potential antitrust risk. If Apple is forced to implement detection systems while other platforms (like WhatsApp) remain encrypted without detection, it could be seen as unfair competitive advantage. Regulators might demand equivalent requirements across the board.

What Experts Are Saying

The tech and child safety communities are divided on this.

Privacy advocates argue:

- This lawsuit is corporate pressure to create surveillance infrastructure

- Apple made the right call shelving CSAM detection

- The solution is supporting children through education and parental involvement, not technology

- If Apple loses, it sets precedent for mandating backdoors everywhere

Child safety advocates argue:

- 30 CSAM reports from a 2-billion-device platform is indefensible

- Privacy is important, but children's safety is more important

- Other companies found ways to detect abuse while preserving privacy for non-abusive users

- Apple's excuse is pretextual—it really just wants to avoid the cost and complexity

Technical experts are mostly cautious:

- CSAM detection is technically possible without breaking encryption

- But any detection system creates precedent and legal risk

- The real issue is that this is fundamentally a values decision, not a technical one

Law enforcement supports the lawsuit:

- Agencies want tools to detect and prosecute CSAM distribution

- They view Apple's stance as enabling criminals

- They see this as parallel to encryption backdoor requests

The Broader Conversation

This lawsuit is really about a deeper question: what do we owe children, and what rights do we sacrifice to protect them?

It's not unique to Apple. It's the same question behind:

- School surveillance and monitoring

- Age verification online

- Parental control apps

- Content filtering at ISP level

- Even mandatory reporting laws

Every society has to answer this. The US has historically leaned privacy-conscious. Europe leans toward protection. China leans toward control.

Apple's case will influence where democracies land on this spectrum.

This isn't just legal theater. Actual children's safety and actual privacy rights are in tension here, and no solution is perfect.

Timeline and Next Steps

Here's what we should expect in the coming months and years:

2025 (near-term):

- Other states file similar lawsuits against Apple (likely within 6 months)

- Apple files motions to dismiss, arguing lack of legal standing or First Amendment protection for product design

- Discovery begins, where more internal Apple documents become public

- Media attention continues, putting pressure on Apple

2025-2026 (medium-term):

- Early cases go to trial or settlement discussions begin

- Congress potentially holds hearings on CSAM and tech platform responsibility

- EU regulators evaluate whether Apple violates the Digital Services Act

- Apple potentially announces limited CSAM detection as compromise

2026+ (long-term):

- Appellate decisions establish precedent for other cases

- Regulatory action in multiple countries

- Potential legislation mandating CSAM detection across platforms

- New technical standards emerge for balancing encryption and detection

FAQ

What exactly is CSAM and why does it matter for this lawsuit?

CSAM stands for Child Sexual Abuse Material. It's any recorded depiction of sexual abuse involving minors. The lawsuit argues Apple's platform is being used to distribute and store this material because iCloud lacks detection systems that other major platforms use. The volume matters because it indicates whether Apple's architecture is actually facilitating abuse or merely passively hosting it.

Why did Apple originally plan CSAM detection and then abandon it?

Apple announced CSAM detection in 2021 as a way to identify known abuse material in iCloud. The company shelved the project within a year after fierce opposition from privacy advocates, civil rights organizations, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who argued it would create a backdoor precedent allowing governments to demand scanning for political dissent or other content. Apple ultimately decided privacy positioning was more important than CSAM detection capabilities.

How does end-to-end encryption relate to CSAM detection?

End-to-end encryption means data is encrypted on the sender's device and can only be decrypted by the recipient. Apple's server can't see the content. This is great for privacy but prevents the company from scanning for abuse material. Other platforms like Meta and Google don't use end-to-end encryption for all services, which allows them to scan content and report abuse. Apple chose encryption as its differentiator, which means no detection.

Why are the reporting numbers (267 vs. 1.47 million) so significant?

The disparity in CSAM reports suggests Apple is detecting much less abuse than competitors at similar scale. Apple has roughly 2 billion devices but made only 267 reports in 2023, while Google made 1.47 million reports. Statistically, if abuse material is distributed randomly, you'd expect detection to scale with user numbers. The huge gap suggests Apple's platform is either unusually free of abuse (unlikely) or missing abuse that detection would catch (more likely).

What could Apple do to address this lawsuit without breaking encryption?

Apple has several technical options: implement on-device scanning before content is encrypted, allow users to opt-in to detection on their account, use client-side hashing to compare files without decrypting them, or partner with law enforcement on specific investigations. The company could also implement the parental controls and safety features it already uses, but more aggressively. The lawsuit isn't saying these options are impossible—it's saying Apple chose not to use them.

If Apple loses, what happens next?

If the lawsuit succeeds, Apple could be ordered to implement CSAM detection, pay damages to West Virginia, or both. Other states would almost certainly file similar suits. Apple might then be forced to add detection tools to iCloud to comply, which would break the company's privacy-first marketing position. Alternatively, Apple could appeal and fight this in higher courts, accepting years of legal and reputational costs. Settlement is also possible, where Apple agrees to limited detection in exchange for dismissal.

Could this ruling apply to other encrypted services like WhatsApp or Signal?

Potentially, yes. If courts establish that platforms hosting massive amounts of user data have a legal obligation to detect abuse, that principle could extend to any encrypted service. WhatsApp, owned by Meta, might face less pressure since Meta can subpoena data for law enforcement. But Signal and other pure encryption services could face similar suits, forcing them to add detection or shut down certain services.

Why doesn't Apple just use the same detection tools that Google and Meta use?

Microsoft's Photo DNA and Google's Content Safety API work on encrypted services too, to some degree. They scan content before encryption or use hashing techniques that don't require decryption. Apple could theoretically license these tools. The reason Apple hasn't is partly philosophical (the company wants to avoid even appearing to scan user content) and partly strategic (detection creates liability and legal risk that Apple wanted to avoid).

What's the timeline for this lawsuit to be resolved?

These cases typically take 3-5 years to work through trial, unless there's a settlement earlier. Discovery (where both sides exchange evidence) usually takes 1-2 years. During that time, we'll learn more about what Apple's executives knew and when they knew it. Other states will likely file suits during this period, creating parallel cases. The first decision could be appealed, pushing resolution even further out. Apple might settle earlier to avoid negative publicity during discovery.

The Bigger Picture

This lawsuit represents something larger than just Apple. It's the collision of two increasingly incompatible values: privacy and child protection.

For decades, tech companies could kind of ignore this tension. But now, with billions of devices, billions of users, and documented abuse happening at massive scale, the tension has become impossible to avoid.

Apple chose to optimize for privacy. That's a legitimate choice. But it comes with tradeoffs, and this lawsuit is the bill coming due.

The question the courts will answer is simple: does Apple's privacy positioning exempt it from responsibility to prevent the distribution of child abuse material on its servers?

Based on the facts—267 reports from a 2-billion-device platform, competing platforms at similar scale making millions of reports, Apple's own abandoned plans to detect CSAM, and that internal email about iCloud being a platform for abuse—the answer seems unlikely to be yes.

Apple will probably lose this lawsuit. Not because courts hate privacy, but because the gap between Apple's approach and the scale of potential harm is too large to ignore.

And then the real question becomes: what does Apple do about it?

That decision will shape not just Apple, but the entire future of encryption, privacy, and platform responsibility in the digital world.

Key Takeaways

- West Virginia sued Apple over iCloud's alleged role in enabling child sexual abuse material distribution after the company abandoned CSAM detection plans

- Apple made only 267 CSAM reports to authorities compared to Google's 1.47 million and Meta's 30.6 million, revealing massive detection capability gap

- Internal Apple emails allegedly described iCloud as 'the greatest platform for distributing child porn,' suggesting company awareness of vulnerability

- Apple faces tension between privacy-first positioning (its brand differentiator) and child safety obligations (required by emerging regulations)

- Lawsuit precedent could force Apple to implement detection tools, trigger similar suits in other states, and reshape tech regulation globally around child protection

Related Articles

- New York's Robotaxi Reversal: Why the Waymo Dream Died [2025]

- Texas Sues TP-Link Over China Links and Security Vulnerabilities [2025]

- FCC Equal Time Rule Debate: The Colbert Censorship Story [2025]

- Freedom.gov: Trump's Plan to Help Europeans Bypass Content Bans [2025]

- Prediction Markets Battle: MAGA vs Broligarch Politics Explained

- Zuckerberg's Testimony in Social Media Addiction Trial: What It Reveals [2025]

![Apple's iCloud CSAM Lawsuit: What West Virginia's Case Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/apple-s-icloud-csam-lawsuit-what-west-virginia-s-case-means-/image-1-1771522656039.jpg)