New York's Robotaxi Reversal: Why the Waymo Dream Died in Albany

Last month, New York Governor Kathy Hochul had a plan that seemed logical on paper. Let autonomous vehicles loose in upstate cities—Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse—while letting New York City's mayor and City Council decide whether Manhattan needed driverless taxis. Simple compromise, right?

It never made it out of the legislature.

In February 2025, Hochul quietly dropped the robotaxi proposal, citing insufficient support among state lawmakers. No dramatic press conference, no detailed explanation. Just a statement from her spokesperson: the legislature didn't want it, so it's gone.

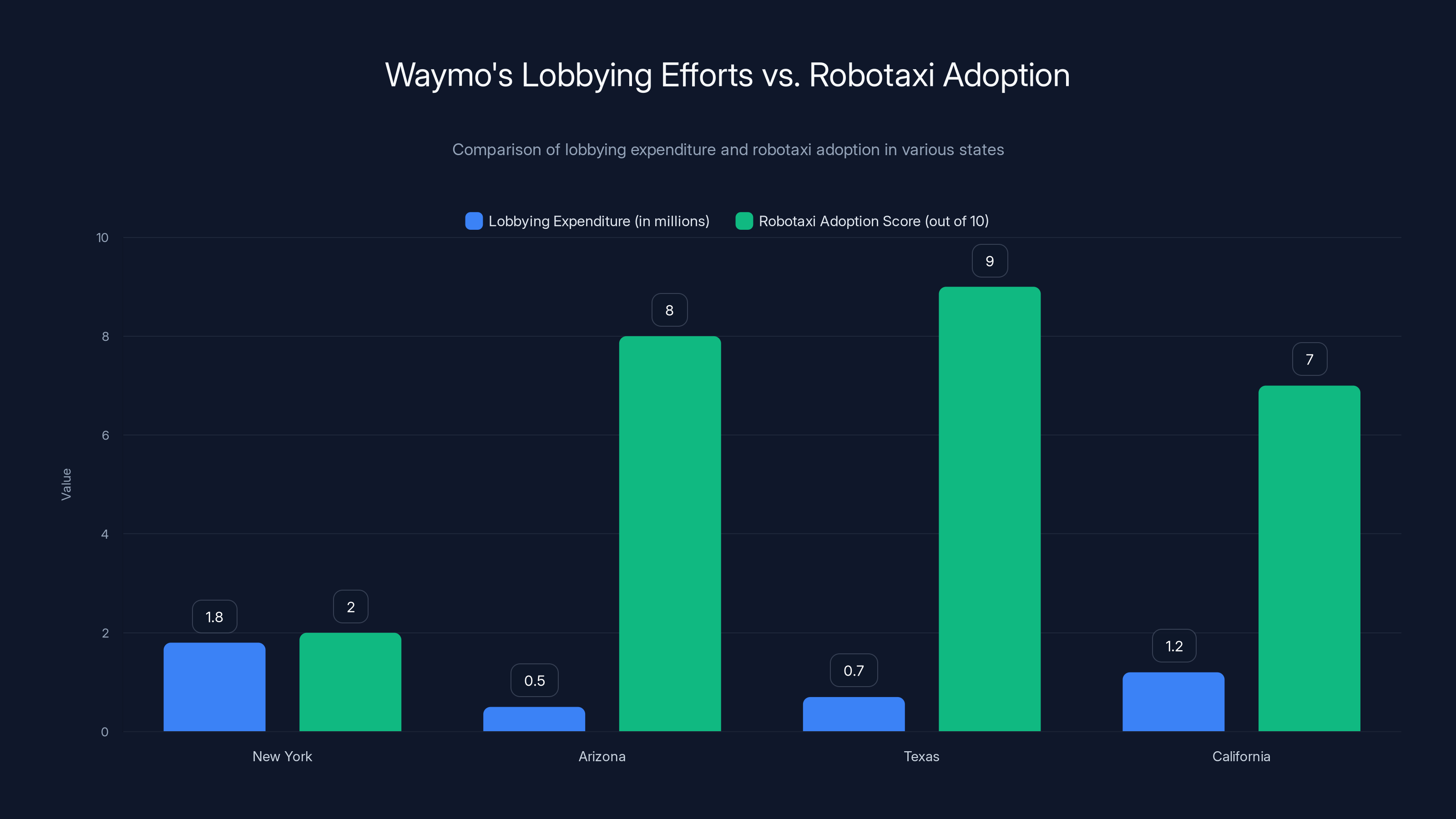

This wasn't some fringe idea either. Waymo had been lobbying for this moment for years, spending at least $1.8 million since 2019 to influence state and city officials. The company is currently testing vehicles in Manhattan under a permit expiring in March. It's operating driverless services in six U.S. cities already and was targeting 20 more in 2026.

But none of that lobbying money mattered when the votes weren't there.

What happened in Albany tells us something crucial about autonomous vehicles in America right now. Technology alone isn't enough. Public trust isn't there yet. And politicians are finally listening to their constituents instead of corporate playbooks.

This story goes deeper than one failed proposal. It reveals the massive gap between what tech companies think they can do and what communities actually want. It shows why Arizona and Texas became robotaxi hotbeds while New York, the nation's largest taxi market, remains closed off. And it raises a harder question: will American cities ever fully embrace driverless vehicles, or are we watching the slow collapse of an overhyped industry?

TL; DR

- Hochul's proposal died in the legislature with no support materializing despite extensive lobbying from Waymo and other robotaxi companies

- Waymo spent $1.8 million lobbying since 2019 but couldn't convince New York lawmakers to vote yes

- The plan would've allowed limited robotaxi testing in upstate cities while deferring NYC's decision to local officials

- Waymo's testing permit expires March 31, 2025, and the company now has no clear path to commercialize in New York

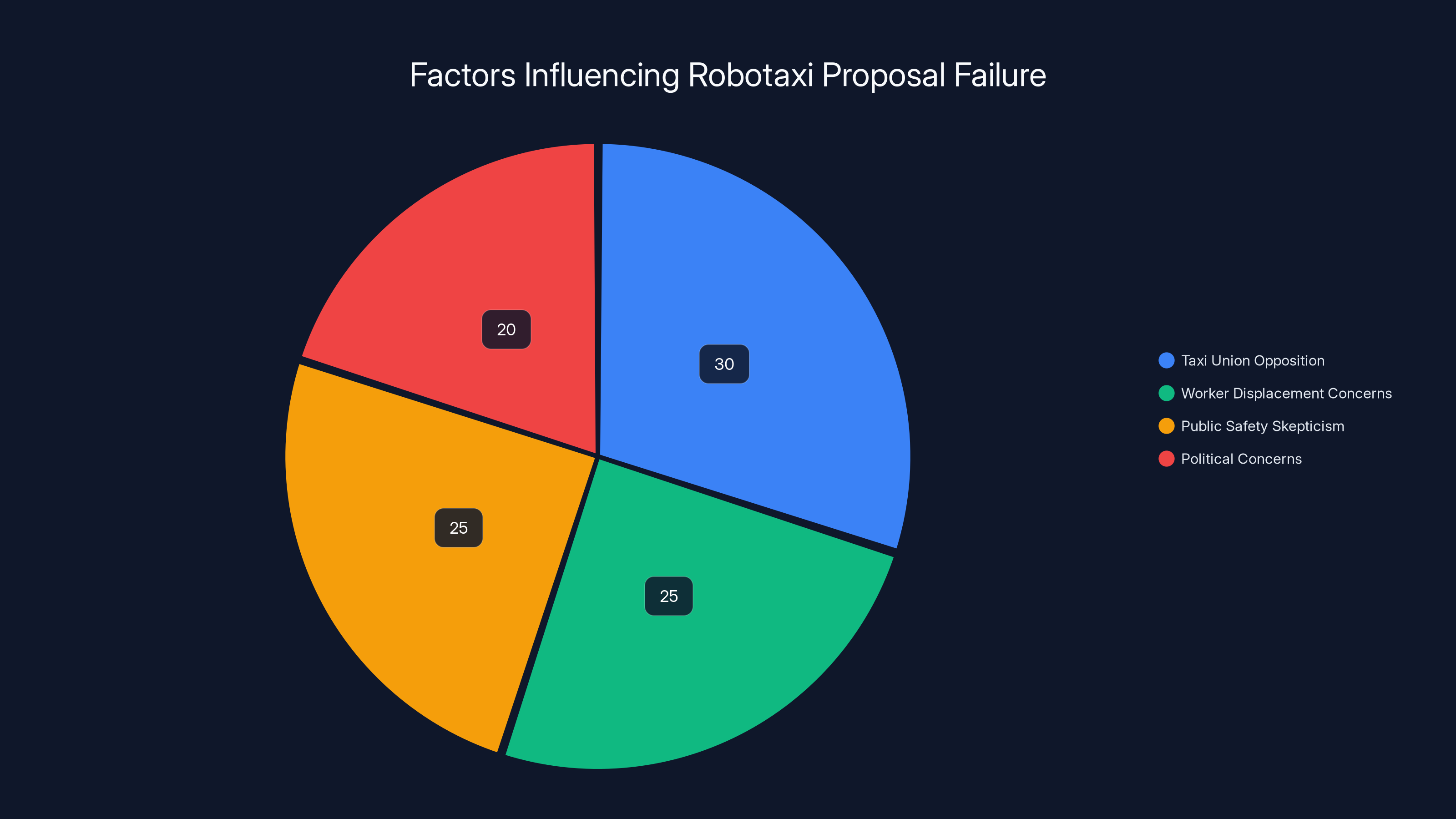

- Public safety concerns and taxi industry opposition likely contributed more to the defeat than any legislative technicality

- This signals a broader skepticism about autonomous vehicles that tech companies failed to anticipate or address

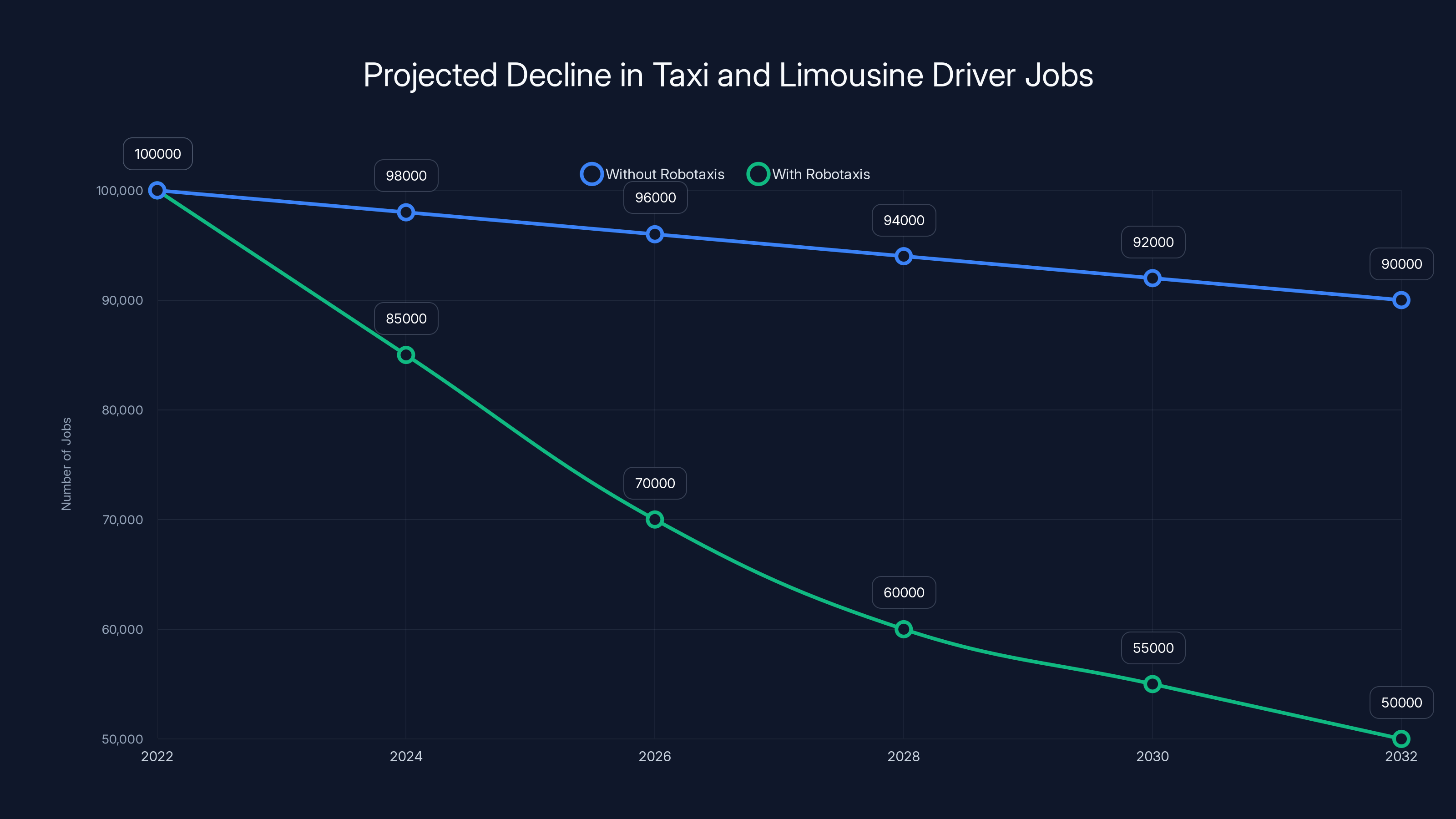

The taxi and limousine driver occupation is projected to decline by 4% from 2022 to 2032 without robotaxis. With autonomous vehicles, the decline could accelerate to 30-50%, potentially eliminating 80,000-100,000 jobs. Estimated data.

Why New York Mattered So Much to Waymo

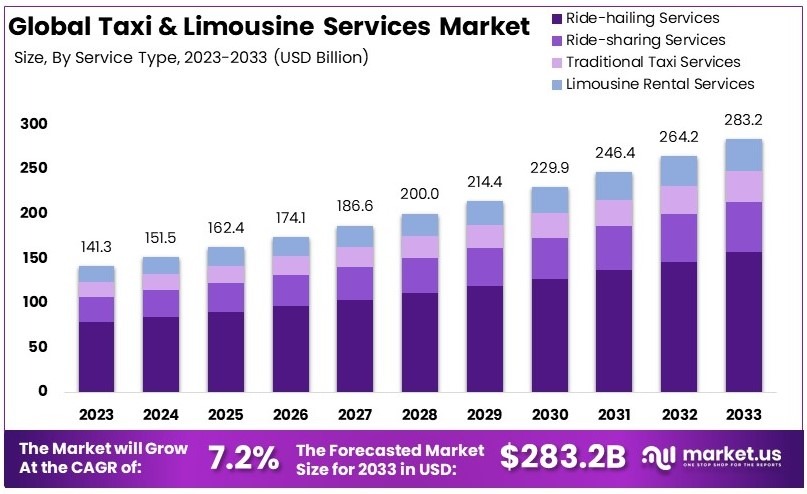

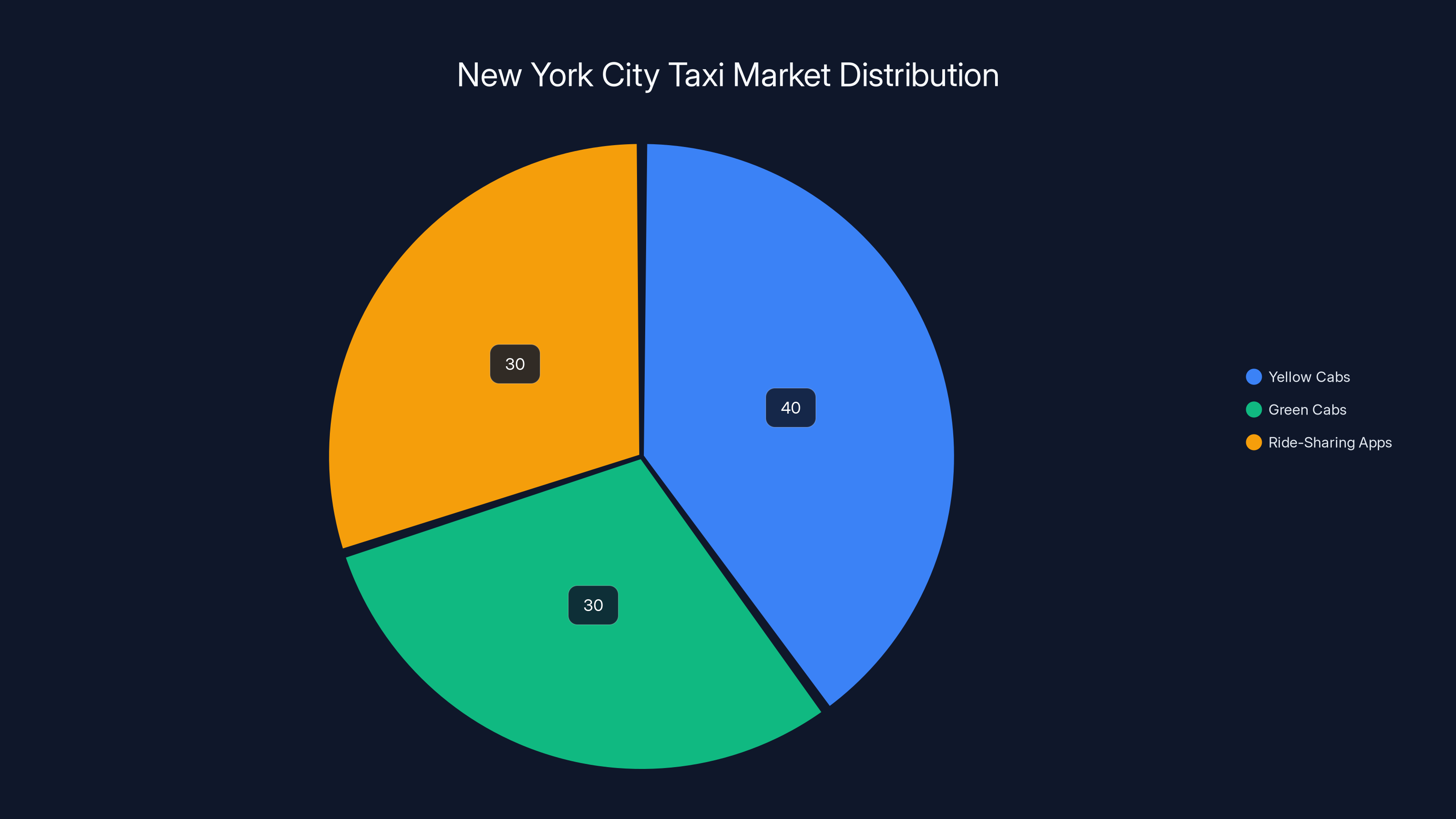

New York City has roughly 13,600 yellow cabs and another 13,600 green cabs serving outer boroughs. That's a $5 billion annual market, maybe more when you count ride-sharing apps that operate in parallel. For a robotaxi company, that's not just a city—that's a goldmine.

Waymo understood this better than anyone. The company didn't stumble into New York after finding success elsewhere. It went there deliberately, methodically, and expensively.

In December 2025, a Waymo Jaguar electric vehicle was spotted testing in Manhattan. The company had been conducting these tests intermittently for years, operating under a permit from Eric Adams' administration. That permit allowed manual testing—someone actually sitting in the driver's seat—but not autonomous commercial operations.

The window was closing. That permit expired March 31, 2025, giving Hochul and the legislature a decision deadline they couldn't ignore.

Waymo's lobbying strategy made sense strategically. Instead of asking New York City for approval—which would've meant negotiating with Mayor Adams, the City Council, and taxi unions simultaneously—they went to the state level. Hochul's budget proposal offered a path: legalize limited driverless operations in other cities first, prove the technology works, then convince NYC's leadership later.

This was actually smart politics. Get the technology operating somewhere within New York State, build a track record, then expand into Manhattan when the opposition weakens.

Except the legislature saw through it.

The Lobbying Effort That Wasn't Enough

Waymo's $1.8 million lobbying spend since 2019 puts money behind the company's seriousness. That's not casual lobbying. That's a sustained, multi-year influence campaign.

But here's what's instructive: that money was enough to secure a testing permit. It wasn't enough to legalize commercial operations.

The difference between those two things is massive. A testing permit lets you drive around Manhattan with a safety driver, collecting data, learning edge cases. It's about research and development. Legalizing robotaxis means removing the safety driver entirely and charging passengers. It means real economic disruption, not theoretical possibility.

When legislators vote on research permits, they're voting on "is this safe enough to study?" When they vote on commercialization, they're voting on "are we ready to displace thousands of workers in a massive service sector?"

These are different votes.

Waymo wasn't alone in this lobbying effort. Other autonomous vehicle companies have been working the same angles. But the collective lobbying push still failed because the underlying political calculation changed.

Hochul's team clearly miscalculated. They thought that a proposal to start outside of NYC, with deference to NYC's leadership on the city's own rules, would pass easily. They'd frame it as compromise. Let rural areas benefit from autonomous vehicles while cities got to decide their own future.

But compromise requires both sides to negotiate in good faith. The legislature apparently never saw it that way.

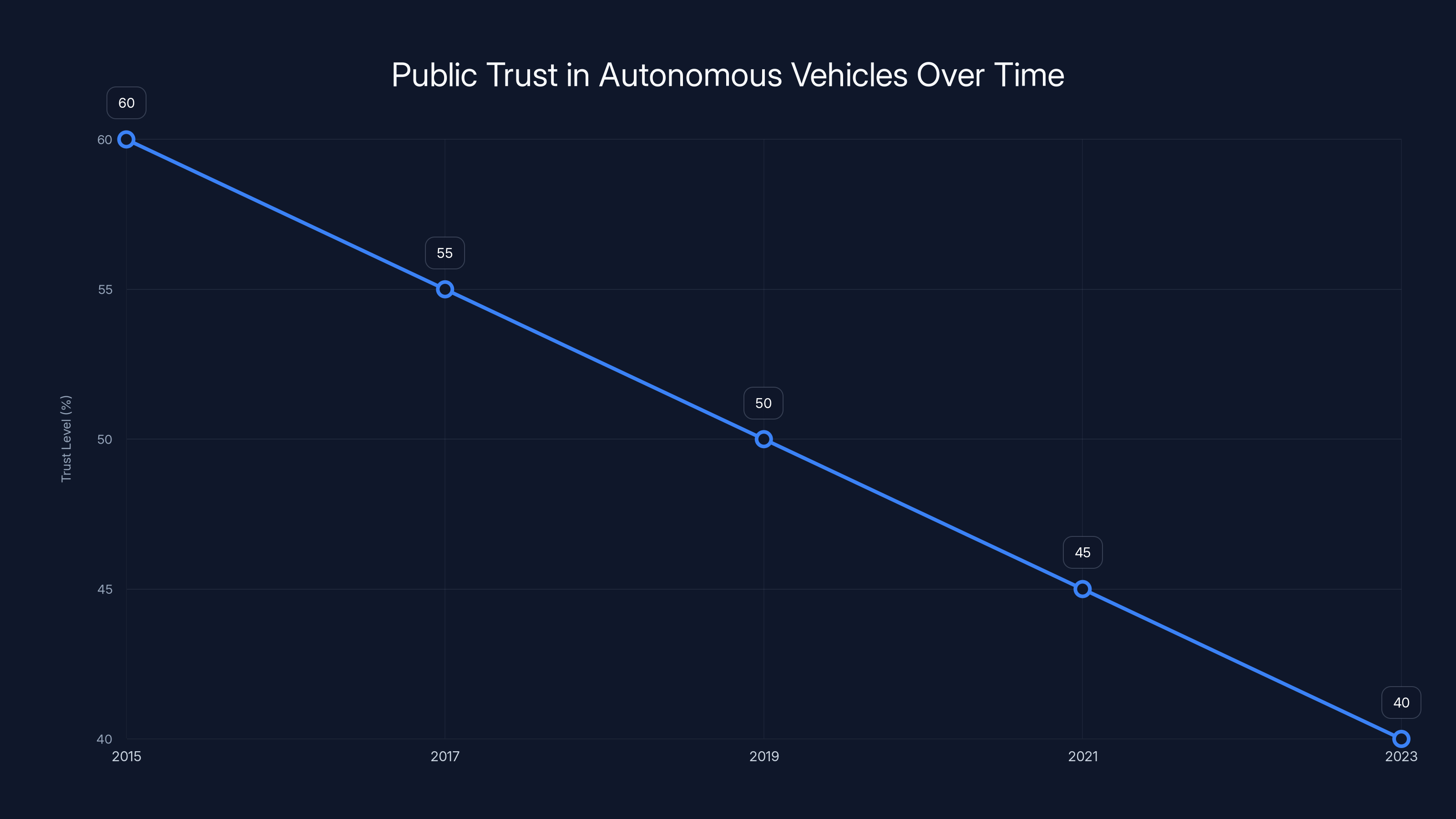

Estimated data shows a decline in public trust in autonomous vehicles from 2015 to 2023, despite technological advancements. Public perception is influenced more by high-profile incidents than statistical safety improvements.

The Taxi Industry's Quiet Opposition

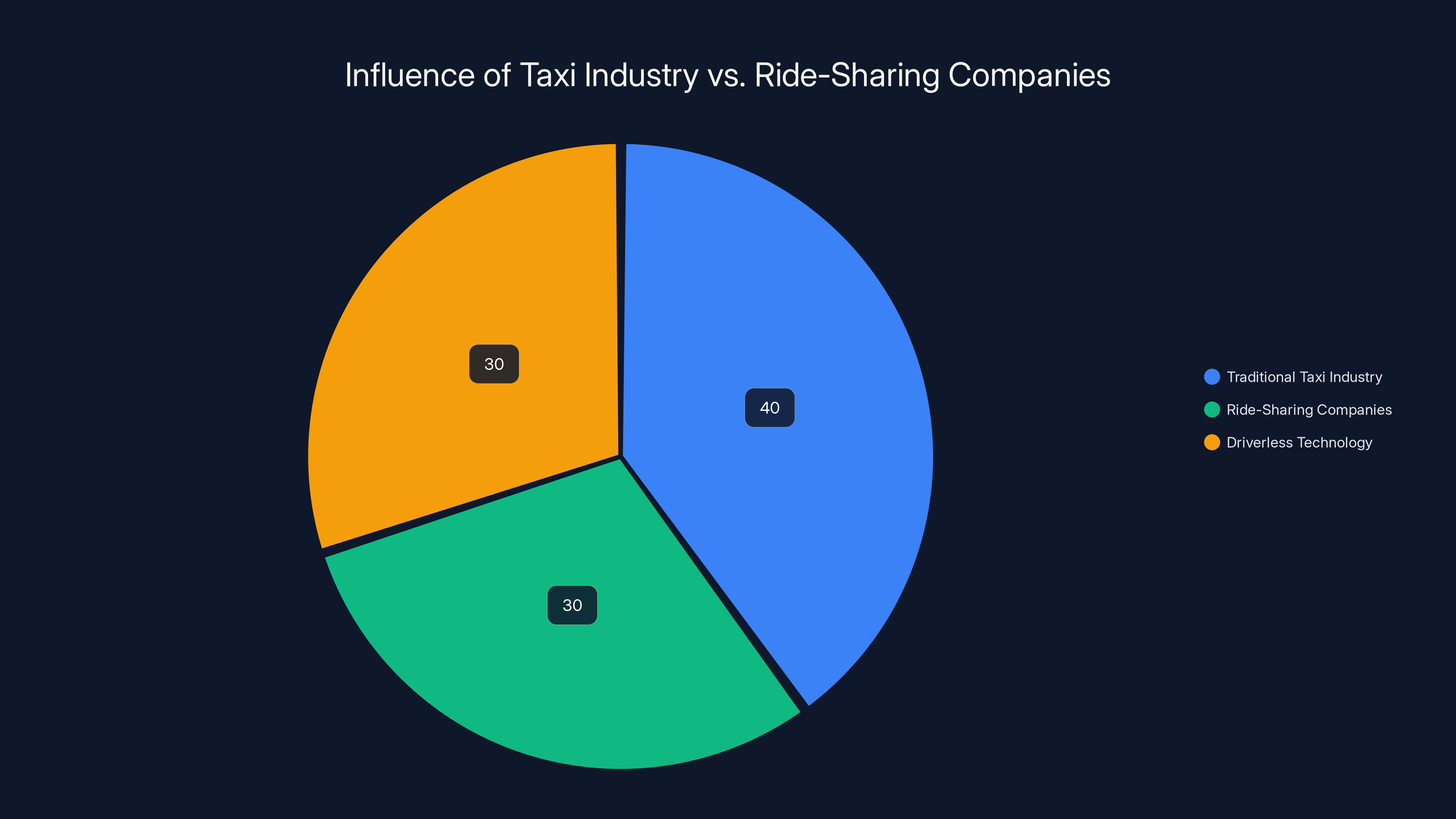

New York's taxi industry didn't need to spend $1.8 million to kill this proposal. They just needed to show up and remind legislators what their constituents do for a living.

Licensed taxi drivers represent a politically active bloc in New York. They vote. They organize. They talk to their council members and state representatives. When you're driving a cab twelve hours a day, you understand intimately how a new technology threatens your livelihood.

Unlike Uber and Lyft drivers—who tend to be more atomized and less organized—traditional taxi drivers have licensing requirements, associations, and collective history. The Taxi Workers Alliance, the largest taxi driver labor organization in the U.S., has significant institutional power in New York politics.

Waymo's plan to flood the market with driverless vehicles would've directly competed with those licensed cabs. It would've done to the remaining traditional taxi industry what Uber and Lyft already did: undercut prices, fragment the market, and push drivers toward gig work or unemployment.

Taxi unions could frame this straightforwardly to legislators: "You want to tell thousands of hardworking New Yorkers their jobs are obsolete?" That's a much more compelling pitch than "trust us, this technology is safe," especially when the public still isn't sure.

The irony? Hochul's proposal might've faced less opposition if the taxi industry wasn't already devastated. If medallions were still worth $1.3 million and drivers were earning good livings, the political cost would've been lower. But as it stands, robotaxis felt like the final nail in an already-failing coffin.

Public Safety Concerns That Never Really Got Addressed

This is where the story gets interesting. Waymo's vehicles are genuinely impressive when they work. I've seen the data. The company's driverless vehicles have millions of miles on California and Arizona roads. They handle rain, snow, construction zones, and pedestrian interactions.

But impressive isn't the same as safe enough.

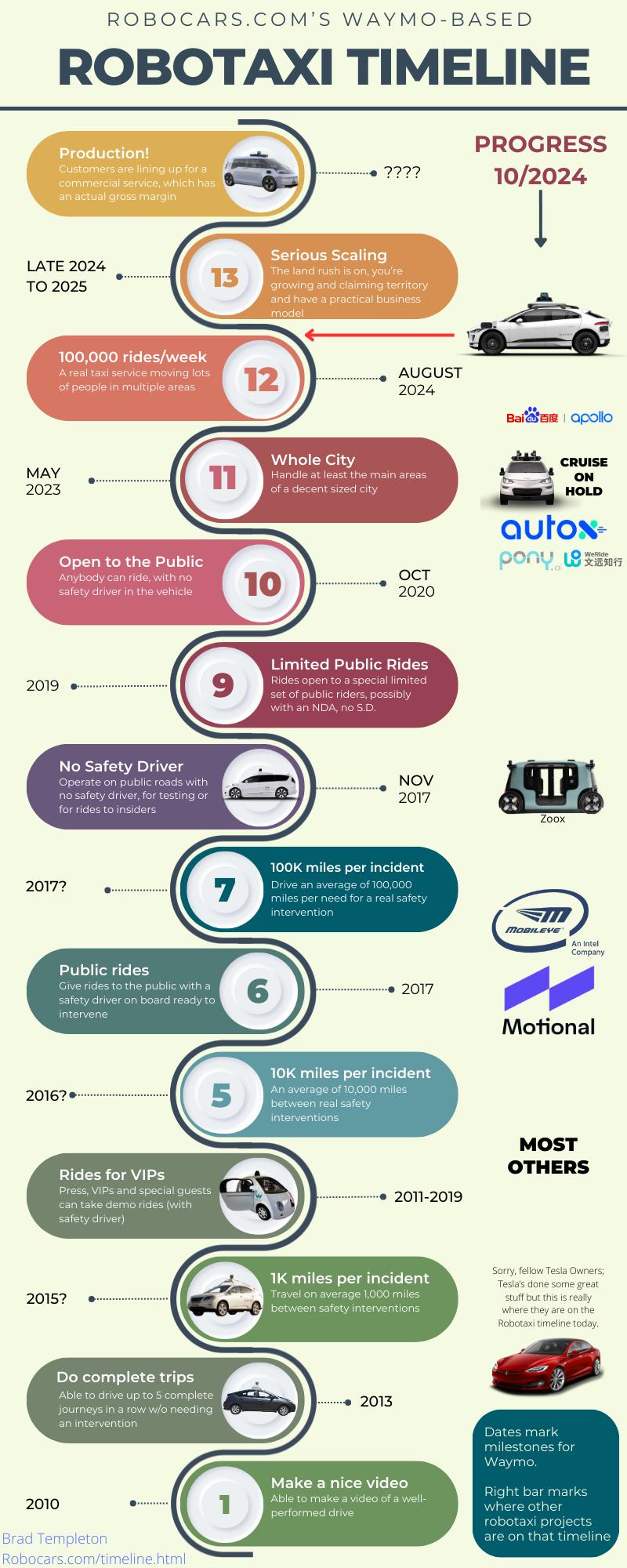

Public safety concerns about autonomous vehicles fall into a few categories. There's the technical question: do these cars crash less than human drivers? The answer appears to be yes, at least in controlled conditions. Arizona has been running Waymo's fully driverless service since 2020 without major incident.

Then there's the operational question: what happens when the system fails? Waymo had already experienced some embarrassing moments in California—one vehicle blocking another Waymo vehicle, creating a "robotaxi jam." Another got stuck in a neighborhood for hours because of a construction barrier the mapping system didn't recognize.

These failures aren't catastrophic, but they're failures nonetheless. And they're failures in a place where the company had years to optimize.

New York is infinitely more complex than Phoenix or San Francisco. The streets are narrower, denser, more chaotic. You've got delivery trucks double-parked on every block, pedestrians stepping between cars, cyclists weaving through traffic, street vendors, construction, and snow that melts into slush that might confuse camera systems.

Even if Waymo's vehicles work 99% of the time in Phoenix, does that translate to 99% in Manhattan? Or does complexity drop that to 95%? 90%?

Legislators weren't equipped to answer that question, and Waymo wasn't offering confidence-building guarantees. The company was essentially asking New York to be an experiment and trust that nothing too bad would happen.

Public opinion data supports the concern. Americans remain deeply skeptical about fully autonomous vehicles. Trust in self-driving technology has actually declined in recent years despite technological improvements, suggesting that concerns are more psychological than technical.

The Permit Expiration Ticking Clock

March 31, 2025 was the hard deadline.

Waymo's testing permit under the Adams administration was set to expire. Once that happened, the company couldn't legally test autonomous vehicles in New York without a new permit or approval.

Hochul's budget proposal was designed to solve this problem. By codifying robotaxi legalization at the state level, it would've overridden the need for municipal permits. Waymo (and potentially other companies) could operate commercially across New York State without needing to renegotiate with NYC leadership.

But that only works if the state legislature votes yes.

The timing created pressure, which might have been Hochul's intended strategy. Propose the rule change, let the deadline approach, watch the legislature realize they need to act before the permit expires.

Except the legislature just... didn't act. No vote. No floor debate. No attempt to negotiate toward a compromise. Instead, support simply failed to materialize.

This suggests the opposition to Hochul's plan wasn't just unenthusiastic—it was genuinely hostile. If there had been even moderate support, someone would've tried to advance it. The fact that nothing happened indicates enough legislators were opposed that they didn't even bother negotiating.

Waymo is now in limbo. Its permit expired. It can't test legally. It can appeal for an extension or work toward a new negotiation, but momentum has shifted dramatically against the company.

Despite Waymo's significant lobbying efforts in New York, the state has a low robotaxi adoption score compared to Arizona and Texas, where adoption is much higher. Estimated data.

Why Arizona and Texas Became the Robotaxi Havens

Waymo's driverless operations are thriving in Phoenix. The company runs a real commercial service, charging passengers, picking them up and dropping them off without a human in the car. Thousands of rides per day. It's working.

Texas has been even more welcoming, with the state actively courting autonomous vehicle companies and creating favorable regulatory conditions.

There's a clear difference in political culture. Arizona and Texas have Republican-leaning leadership that's skeptical of regulation in general. If you're hesitant to regulate ride-sharing, you're probably hesitant to regulate autonomous vehicles too. The instinct is to let the market work, assume innovation solves problems, and get out of the way.

New York, by contrast, has Democratic-leaning leadership that's more interventionist. But here's the twist: Hochul is a moderate Democrat who actually wanted to approve robotaxis, and she still couldn't convince her own party's legislature to go along.

This suggests the opposition transcends simple partisan politics. It's about labor power, constituent concerns, and a general skepticism about whether New York wants to be ground zero for a technology that nobody's fully convinced is ready.

Arizona is also smaller, less dense, and has a more car-dependent culture to begin with. Phoenix's sprawl is ideal for autonomous vehicles. They love highway driving, highway parking lots, and relatively simple residential streets. New York's gridded density, with constant pedestrian interaction and complex traffic patterns, is the harder problem.

Texas has similar advantages, plus a much stronger "let business do what it wants" political ethos.

New York sits at the intersection of being tremendously valuable (largest taxi market, huge population) and tremendously difficult (dense, complex, well-organized labor opposition). For Waymo, it's attractive precisely because it's hard. But that difficulty also makes politicians more cautious about approving it.

The Broader Industry Implications

Waymo's setback in New York is part of a larger pattern of autonomous vehicle hype crashing into regulatory reality.

Back in 2020, autonomous vehicle companies were talking about robotaxi fleets operating in dozens of cities by 2025. Waymo was going to revolutionize transportation. Tesla's Elon Musk promised a robotaxi service that would make ride-sharing look primitive.

Here we are in 2025.

Waymo operates commercial robotaxis in maybe six cities, and that's counting expansion that took longer than anyone expected. Tesla has still never launched a robotaxi service, despite years of promises. Cruise, which was backed by General Motors and showed tremendous promise, had a major setback after an accident involving a pedestrian.

The gap between technological possibility and regulatory approval has proven much larger than anyone anticipated. The technology improved faster than public trust, which created a gap that no amount of lobbying could bridge.

Waymo's experience in New York, if it becomes more common, might signal that the low-hanging fruit of autonomous vehicle deployment is already picked. Arizona and Texas offered favorable conditions because of regulatory culture and geography. Expanding into denser, more complex, more politically organized cities is going to be much harder.

That doesn't mean robotaxis will never happen in New York. It means it'll take longer, and probably require some actual accident-free track record demonstrated elsewhere first.

What Waymo Said in Response

Waymo's official statement tried to position the loss as temporary. A spokesperson said the company remains committed to bringing service to New York and will work with the legislature to advance the issue.

That's the standard corporate response when something doesn't work out. Express disappointment, reaffirm commitment, pivot to the future.

But the practical reality is different. Without a permit, Waymo can't test. Without state legalization or NYC approval, it can't operate commercially. The company is essentially back to square one, except the clock has moved forward and public skepticism might have increased.

Waymo does have leverage in theory. It could work with NYC officials independently, trying to secure city-level approval to continue testing. Or it could focus on other cities where expansion might be easier. Or it could try again in Albany once political winds shift.

But each of those options is more expensive and more time-consuming than the state-level solution Hochul had offered.

The statement also mentioned "a collaborative approach that prioritizes transparency and public safety." Translation: we acknowledge that public safety concerns killed this, and if we're going to try again, we need to address them head-on.

That's actually the most interesting part. If Waymo's next proposal includes major commitments about transparency, safety oversight, or worker transition assistance, it might have better luck. The company is learning that raw technical capability isn't enough.

The failure of Hochul's robotaxi proposal was influenced by multiple factors, with organized opposition from taxi unions and public safety concerns being significant contributors. (Estimated data)

The Political Reality: Why Hochul's Compromise Failed

Hochul's approach was structurally smart but tactically naive.

The governor proposed legalizing robotaxis outside of NYC while explicitly deferring the NYC decision to local officials. This was framed as a compromise: upstate gets autonomous vehicles, the city gets to decide its own future.

From a governance perspective, this makes sense. Why should New York City's mayor get to veto a technology that could benefit Buffalo and Rochester? If those communities want autonomous vehicles, shouldn't they be allowed to have them?

But compromise assumes both sides want to negotiate. The legislature apparently didn't.

This could mean a few things. Either enough legislators opposed the idea entirely (regardless of whether it was NYC-specific). Or they believed their constituents opposed it. Or they worried about the precedent of state-level approval for a technology that could later migrate to NYC without warning.

Once a technology is legal in New York, it's harder to keep it out of specific cities. Companies will argue they should operate everywhere. Regulators will struggle to justify restrictions in some places but not others.

So even if the formal proposal excluded NYC, the legislature might've read it as the thin edge of the wedge. Approve it upstate, and within five years, Waymo will be in Manhattan anyway.

That calculation might've been decisive.

How This Affects Ride-Sharing Companies Like Uber and Lyft

Uber and Lyft have been quietly investing in autonomous vehicle technology for years. They see the writing on the wall: if robotaxis become viable, they could dramatically cut labor costs by eliminating driver pay.

Neither company needed robotaxis to succeed as a business. Both are profitable (or close to it) now. But if competitors like Waymo can operate driverless services at lower cost, Uber and Lyft would need to match that or lose market share.

New York's decision to reject Hochul's proposal actually helps Uber and Lyft in the short term. It delays the arrival of a potentially superior competitor. It gives drivers more breathing room. It protects their model for several more years.

But long-term, both companies know robotaxis are coming eventually. They're hedging by investing in autonomous tech themselves. Uber acquired Otto (an autonomous trucking company) back in 2016 for $680 million, though the company eventually shut down that division.

So while Waymo stumbled in New York, the broader trend toward autonomous transportation remains intact. Regulatory setbacks just slow it down, they don't stop it.

For workers in the ride-sharing and taxi industries, this is mixed news. The reprieve is temporary. But organizing and political mobilization clearly work. The fact that taxi unions and driver advocates slowed down robotaxi deployment in the nation's largest city suggests that organized labor can actually influence these outcomes.

That's actually significant for the future of work conversations.

The Precedent This Sets for Other States

What happens in New York matters for the entire country's autonomous vehicle policy.

Waymo was hoping New York's legalization would trigger a cascade. If one major state approved robotaxis, others would follow, and suddenly the patchwork of rules becomes a national standard.

Instead, New York's rejection might do the opposite. Other states might point to New York's decision as evidence that they should be cautious too.

Washington State, Michigan, and Illinois have all been watching these developments. California obviously has autonomous vehicle activity. Now they're all going to see that New York—with its massive taxi market and political sophistication—looked at robotaxis and said no.

That's a powerful signal.

It doesn't mean other states won't eventually approve robotaxis. Arizona and Texas are already full speed ahead. But it suggests that expecting a wave of state-level approvals might be overconfident.

More likely scenario: robotaxis expand in states with favorable political conditions (Republican-leaning, car-dependent, less organized labor). They move slowly into states with more caution (Democratic-leaning, dense urban centers, strong unions). New York becomes a symbol of that resistance.

Estimated data shows that ride-sharing apps hold a significant portion of the NYC taxi market, comparable to traditional yellow and green cabs.

The Testing Permit Question: What Happens Next?

Waymo's permit expired March 31, 2025. That was now.

The company has a few options. First, it could apply for a new testing permit through the Adams administration's successor, whoever took office after Adams. Testing is different from commercial operation, so there's a potential case for extending the permit without waiting for full legalization.

Second, it could work with NYC officials directly. Mayor's office, City Council, Transportation Department. Negotiate a city-level solution that doesn't require state legislation.

Third, it could simply wait and try again in a year or two, letting political winds shift.

Fourth, it could focus on other cities where expansion might be easier and come back to New York once it has a stronger track record.

Each option has costs. Testing permits don't lead to revenue. City-level negotiations might face the same labor opposition. Waiting means years without New York market access. Expansion elsewhere is the core business, but it doesn't solve the New York problem.

What's almost certain: Waymo won't be operating driverless commercial robotaxis in New York in 2025. That window closed when the legislature didn't approve Hochul's proposal.

The Public Trust Problem Nobody's Solving

Here's the uncomfortable truth that Waymo's $1.8 million lobbying effort couldn't overcome: most people don't trust autonomous vehicles yet.

Survey after survey shows Americans are skeptical about self-driving cars. Trust has actually declined in recent years, even as the technology improved. This isn't rational—Waymo's vehicles are probably safer than human drivers statistically. But rationality isn't how people evaluate risk.

When you hear about a robotaxi accident, you remember it. When you hear about the 46,000 Americans killed in car accidents by human drivers every year, it's just a statistic. Psychologically, machine failure feels different from human failure, even when machines fail less often.

And there have been some high-profile failures. Cruise's robotaxi hit a pedestrian in San Francisco in 2023 (the person was injured but recovered). That incident shaped perception more than a thousand uneventful Waymo rides in Phoenix.

This is a problem that money can't solve. Waymo could spend $100 million lobbying and still face the same underlying trust issue.

What could solve it? Time and track record. Years of safe operation in multiple cities, with transparent reporting, would gradually shift public opinion. But that takes a decade minimum, not a lobbying campaign.

New York's legislature was probably reading the public mood when they declined to support Hochul. The constituents didn't want it, so the representatives didn't vote for it. That's democracy working as designed.

Where Autonomous Vehicles Are Actually Succeeding

It's important to contextualize Waymo's New York loss. The technology is working elsewhere. This isn't a story about autonomous vehicles failing broadly. It's a story about autonomous vehicles hitting a wall in a specific place with specific political and cultural factors.

Phoenix's Waymo service is genuinely impressive when you look at the data. The company is running thousands of rides weekly without major incident. Passengers are paying to ride in cars with no human driver. It's real.

Texas is rolling out rapid expansion. Multiple robotaxi startups are operating or planning to operate there. The regulatory environment is exceptionally friendly.

California still has the most autonomous vehicle activity overall, even if regulation is more complex than Arizona or Texas.

So the story isn't "robotaxis are failing." The story is "robotaxis can work in some places, but they're hitting unexpected obstacles in others, and New York is a symbol of those obstacles."

This actually matters for predicting the future. If robotaxis could only ever work in Phoenix and a few other favorable locations, they'd never become economically significant. But if they can work in Phoenix and eventually in most major cities (even with delays), they'll be transformative.

New York's rejection doesn't settle that question. It just means the timeline is longer and the path is less direct than early autonomous vehicle advocates expected.

Traditional taxi industry holds significant political influence due to organized labor and historical presence, while ride-sharing and driverless technologies are emerging competitors. Estimated data.

The Broader Transportation Innovation Problem

Waymo's story touches on something larger about how America adopts transportation innovations.

Everything disruptive faces opposition: railroads threatened horse transportation, cars threatened railroads, airlines threatened trains, Uber and Lyft threatened traditional taxis. Each wave of innovation triggered worker displacement, industry resistance, and regulatory friction.

Autonomous vehicles are hitting that pattern now. The taxi industry understands what robotaxis mean for their business. They're mobilizing politically to slow adoption. That's not unfair or irrational. That's how workers protect themselves when technology threatens their livelihoods.

The question is whether society wants to acknowledge those costs and address them, or whether we want to accept worker displacement as an inevitable cost of progress.

New York's legislature seems to be leaning toward "let's think about this." That doesn't mean no robotaxis ever. It means slow down, work out transition assistance for displaced workers, let the technology prove itself elsewhere first.

That's actually a reasonable position, even if it's slower than Waymo would like.

What Waymo Should Do Next

If I were advising Waymo, here's the strategy I'd recommend.

First, don't push New York hard right now. The politics are hostile, and pushing will only entrench opposition. Wait 18-24 months for political memory to fade.

Second, get a massive number of miles driven in Phoenix, Austin, San Francisco, and other cities. Build an overwhelming track record of safety. When you go back to New York, lead with data. "We've completed 5 million autonomous miles. Here's our safety record compared to human drivers."

Third, work with driver transition programs. Announce partnerships with job training initiatives for taxi and Uber/Lyft drivers. Commit to paying into transition assistance funds. Show that you take the worker displacement question seriously. This won't convince taxi unions, but it might convince politicians.

Fourth, expand aggressively everywhere except New York. Show that you can be patient about New York while building a massive national business. Let success breed acceptance.

Fifth, engage with City Council members independently of state politics. Some council members might be more favorable to robotaxis than state legislators. Build relationships.

Sixth, consider a hybrid model for NYC. What if Waymo committed to keeping a certain percentage of its operations as human-driven services in New York? Or committed to hiring laid-off taxi drivers as vehicle operators for a transition period?

These are all slower, more expensive, and less pure than Hochul's simple legalization. But they acknowledge the real politics of the situation instead of fighting them.

The Unlikely Future: What If Hochul Had Won?

Let's run a counterfactual. What if the New York legislature had approved Hochul's proposal?

Waymo would've started limited operations in upstate cities. Rochester, Buffalo, Syracuse. Probably slower than their Phoenix expansion since these are smaller markets. But real, revenue-generating operations.

Over time, as those operations proved safe and reliable, the pressure on NYC would've mounted. City Council members would've started saying, "Why can't we have this in Brooklyn and Queens? It worked fine in Buffalo."

Mayor's office would've faced pressure from business groups and residents who wanted the service.

Within 3-5 years, you probably would've seen NYC legalize robotaxis, not because the politics changed, but because the ground reality changed. A technology that was purely theoretical became normal in other parts of the state.

Instead, the opposite path is likely. Without state approval, Waymo has no foothold in New York State. NYC leadership has no reason to approve something the state rejected. And the company's window is closing.

Hochul's proposal might've been brilliant if it had passed. By forcing the legislature to vote, it might've accelerated adoption by 3-5 years. But by failing to pass, it might've delayed adoption by that same amount.

The Automation Angle: Workforce Displacement Reality

Here's what gets lost in the robotaxi discussion: these vehicles aren't just nice-to-have technology. They're designed to eliminate a job category entirely.

New York has roughly 27,000 licensed taxi medallion holders and 3,000-4,000 green cab operators. That's not counting Uber and Lyft drivers, who might number 50,000-100,000 in the state.

Robotaxis aren't designed to coexist with human drivers. They're designed to replace them. Waymo's plan was never "we'll operate alongside traditional taxis." It was always "we'll take market share, reduce need for human drivers, and improve margins by cutting labor costs."

From a business perspective, that's rational. From a worker perspective, that's terrifying.

And unlike previous technological disruptions, there's no obvious new job category being created on the other side. Automation isn't generating 27,000 new roles for displaced taxi drivers.

New York's legislature might've been thinking about this implicitly. If Hochul's proposal had included robust transition assistance, worker retraining, or job creation components, it might've passed despite labor opposition.

But it didn't. It was a clean technology approval with the worker displacement question bracketed for later.

That's exactly the kind of proposal legislatures reject when their constituents include large numbers of workers in the affected industry.

International Context: How Other Countries Are Handling Robotaxis

America isn't alone in grappling with autonomous vehicles. Other countries face the same tension between innovation and worker protection.

Canada has been more cautious than the United States, with provincial regulations being stricter. The UK has focused on extensive testing requirements. Germany and France require high safety standards before approving commercial operations.

China, by contrast, has embraced autonomous vehicles much faster. Baidu's robotaxis are operating in multiple Chinese cities with less opposition than Waymo faces in New York.

Why the difference? Partly cultural (China is more top-down decision-making, less worker advocacy). Partly economic (China's taxi market isn't unionized the way New York's is). Partly regulatory (Chinese authorities can mandate adoption in ways U.S. democracy can't).

But the global picture is similar: places with organized labor and democratic governance are moving slowly. Places with either less worker organization or less democratic constraints are moving faster.

This suggests that American opposition to robotaxis might be a feature, not a bug. Democracies that respect labor advocacy are naturally going to delay disruptive technologies more than autocracies. Whether that's a good thing depends on your values.

The Venture Capital Angle: Will Funding Dry Up?

Waymo's loss in New York might have ripple effects on autonomous vehicle funding.

Investors have been betting heavily that autonomous vehicles would be ubiquitous by now. Waymo's failed regulatory push in the largest taxi market in North America signals that timeline is slipping.

Funding for autonomous vehicle startups has already been declining compared to other AI sectors. If the New York precedent spreads, if other major cities also reject robotaxi legalization, investor confidence might crater.

That would slow technological development, which would further delay adoption, creating a downward spiral.

Alternatively, investors might just pick their battles better. They'll focus on cities with favorable politics (Phoenix, Austin, Miami) and accept that major cold-weather cities with organized labor (New York, Chicago, Boston) are 5-10 year problems.

Either way, the economics of autonomous vehicle development get harder.

Learning From Regulatory Failure: What Tech Companies Get Wrong

Waymo's loss in New York is instructive because the company did almost everything right from a pure lobbying perspective.

They spent money. They engaged with officials. They tried to work within the system. They offered a compromise proposal.

And it still didn't work.

This suggests that tech companies are structurally bad at the kind of politics necessary for regulatory approval in industries that displace workers.

They assume that if a technology is good and safe, people will want it. They don't account for the fact that people care more about immediate material interests (my job) than aggregate welfare (society gets cheaper rides).

They assume that money and influence will win legislative votes. They don't account for the fact that some legislators actually represent their constituents instead of the highest bidder.

They assume that regulatory approval is the main hurdle. They don't realize that public trust and worker protection are equally important.

If Waymo wanted to succeed in New York, they probably needed to:

- Fund major job transition programs proactively, before asking for approval

- Hire community organizations to do outreach to driver communities

- Create a revenue-sharing model where displaced workers got ongoing payments

- Commit to slow rollout over 10+ years instead of rapid deployment

- Accept regulation that reserved a percentage of taxi business for human drivers

These are all more expensive and slower than a clean regulatory approval. But they might've actually worked politically.

Instead, Waymo tried to lobby its way to a quick yes. That approach is increasingly ineffective in American politics when labor interests are mobilized.

The Climate Angle: Why Environmental Benefits Don't Win Political Approval

One argument Waymo probably made: autonomous vehicles are electric vehicles. They reduce emissions. They're better for the environment than gas-powered taxis.

In theory, that's a compelling argument in New York, a state that's deeply committed to climate goals.

In practice, it didn't move the needle.

This is because environmental benefits are diffuse and long-term, while job losses are immediate and concentrated. A taxi driver doesn't care that autonomous vehicles will reduce city-wide emissions in 2040. They care that they're unemployed in 2026.

Politicians respond to what voters care about now. Climate benefits 15 years out are abstractions compared to worker displacement next month.

This has broader implications for climate policy. It suggests that technologies with long-term environmental benefits will face political obstacles if they have concentrated negative effects on employment. Solutions require addressing the employment side explicitly, not assuming environmental benefits will overcome labor opposition.

For Waymo, this should've been a learning: lead with worker transition solutions, mention environmental benefits as a bonus.

FAQ

What was Hochul's robotaxi proposal exactly?

Governor Kathy Hochul proposed legalizing limited driverless robotaxi operations in New York cities outside of New York City (like Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse) as part of the state budget proposal in January 2025. The proposal explicitly deferred the decision about whether to allow robotaxis in Manhattan to the city's mayor and City Council. The goal was to let Waymo and other autonomous vehicle companies operate commercially without a safety driver present.

Why did the proposal fail in the legislature?

The legislature never voted on the proposal, and support never materialized. While Hochul's office cited lack of support among lawmakers, the underlying reasons likely included: organized opposition from taxi unions and the Taxi Workers Alliance, concerns about worker displacement from taxi and ride-share drivers, public safety skepticism about untested autonomous vehicles in New York's complex urban environment, and the political reality that concentrated job losses are harder to approve than diffuse long-term benefits. Some legislators may have also feared that state-level approval would inevitably lead to New York City legalization as well, despite the formal proposal excluding the city.

How much money did Waymo spend trying to get this approved?

Waymo spent at least $1.8 million lobbying state and city officials since 2019, according to lobbying disclosure records. This included efforts to influence Governor Hochul, state legislators, and New York City officials. The company also secured a testing permit from the Adams administration that allowed it to operate manually-driven vehicles in Manhattan with a safety driver, though that permit was set to expire on March 31, 2025.

What happens to Waymo's testing in New York now?

Waymo's permit to test vehicles in Manhattan expired on March 31, 2025, and without either state legalization or city-level approval, the company cannot continue testing autonomous vehicles in New York legally. The company may attempt to secure a new testing permit, negotiate directly with city officials, or refocus on expansion in other states where the regulatory environment is more favorable, such as Arizona and Texas. Waymo's commercial operations have been limited to six U.S. cities as of early 2025, and expansion into new markets has proven slower than company executives initially predicted.

Who opposed the robotaxi legalization?

Main opposition came from: the Taxi Workers Alliance and taxi medallion holders concerned about market disruption, Uber and Lyft drivers and their advocates (though these companies themselves are investing in autonomous vehicle technology), union groups worried about worker displacement, and the general public skepticism about autonomous vehicle safety. While not explicitly organized as a unified opposition, these groups collectively influenced enough state legislators to prevent the proposal from advancing.

Is this setback permanent for Waymo in New York?

The setback is significant but probably not permanent. Waymo will likely try again, but success requires either a change in political conditions (different legislature, changed public opinion) or a different approach that directly addresses worker transition and safety concerns. Some observers suggest Waymo should focus on building a stronger track record elsewhere first—once thousands of miles of safe autonomous operation are logged in other states, New York legislators may feel more comfortable approving robotaxis. That timeline probably extends legalization in New York by 3-5 years at minimum.

How does this compare to robotaxi progress in other states?

Arizona, particularly Phoenix, has been far more welcoming to autonomous vehicles. Waymo operates full commercial robotaxi service there with thousands of rides weekly, no safety driver required. Texas has also been very receptive, with multiple robotaxi companies operating or planning operations. California has the most autonomous vehicle activity overall but more complex regulation. New York's rejection stands out because it's the largest taxi market in North America, making it the most economically attractive target for robotaxi companies. Arizona and Texas succeeded partly due to regulatory culture favoring light-touch oversight, car-dependent sprawl that suits autonomous vehicles, and less organized labor opposition than New York has.

What is Waymo's long-term strategy now?

Waymo is likely following a multi-pronged strategy: continue expanding driverless commercial operations in favorable markets like Phoenix and Texas to build track record and revenue, eventually revisit New York with a stronger case based on years of safe operations, and potentially modify its approach to include worker transition assistance or hybrid models that satisfy labor concerns. The company may also shift to addressing the public trust problem more directly, releasing extensive safety data and working with independent researchers to validate that autonomous vehicles are genuinely safer than human-driven alternatives.

Could robotaxis eventually operate in New York without state-level approval?

Yes, possibly. Waymo could work directly with New York City officials to secure city-level approval for commercial robotaxi operations. However, this path has challenges: it requires convincing the mayor and City Council rather than the legislature, and those officials already turned down Waymo's testing permit expansion in recent years. City-level negotiations might also face the same labor opposition as state-level efforts. Some experts suggest a hybrid approach where the city approves limited robotaxi operations (perhaps in outer boroughs first, rather than Manhattan) as a test before full expansion.

What does this mean for autonomous vehicle adoption in America?

New York's rejection suggests that autonomous vehicle adoption in the United States will be slower and more geographically uneven than early predictions. Technology companies expected widespread legalization by 2024-2025; instead, adoption is concentrated in favorable regulatory jurisdictions and slow in states with organized labor and denser urban environments. This precedent may cause other major cities to move cautiously. However, it doesn't suggest autonomous vehicles will never become widespread—it suggests the timeline is 10-15 years rather than 5-7 years, with adoption clustering in specific regions before expanding nationally.

The Real Cost of Political Opposition

Waymo's $1.8 million lobbying spend might sound like a lot, but it's meaningless compared to the political will mobilized against it.

Taxi unions don't spend that kind of money. They organize. They show up at city council meetings. They talk to legislators. They turn workers into constituent voices.

That's harder to counter than money because democracy runs on votes, not dollars.

This is the lesson New York's legislature was apparently heeding. When your constituent base includes thousands of licensed taxi drivers whose livelihoods are threatened, you vote against the technology, regardless of how much the corporation lobbying for it spends.

It's not corruption. It's representation.

Waymo is now learning what every disruptive technology company eventually learns: technical superiority and financial resources aren't enough in a democracy. You also need your innovation to be politically palatable.

For autonomous vehicles, that means figuring out how to manage worker displacement in a way that doesn't generate concentrated opposition. Until that's solved, expect more New Yorks.

Conclusion: The Uncomfortable Truth About Innovation

Waymo got beaten in New York by the oldest force in politics: workers protecting their jobs.

The company had better technology, more money, and a clearer vision for the future. It still lost because it tried to innovate around a bottleneck (labor displacement) instead of through it.

That's the lesson for every tech company betting on autonomous vehicles, AI-powered disruption, or any technology that displaces workers. You can't outspend organized labor in a democracy. You can't lobby around fundamental concerns about worker welfare.

What you can do is acknowledge those concerns directly. Fund transition programs. Create new opportunities for displaced workers. Accept slower timelines. Build genuine public trust through transparency and safety records.

Waymo didn't do those things in New York. And the legislature responded by letting the permit expire instead of approving new operations.

The robotaxi revolution will happen eventually. But it's going to happen slower, and more unevenly, than the optimists predicted. And it's going to require technology companies to actually deal with the human cost of automation instead of just hoping the benefits outweigh the losses.

For now, Waymo will focus on Phoenix. The Tesla robotaxi remains theoretical. And New York taxis will keep operating with human drivers.

The future isn't here yet. And for the people whose livelihoods depend on that delay, that's exactly how they wanted it.

The real story of autonomous vehicles in America isn't about technology at all. It's about whether companies can navigate the political economy of worker displacement. Until they figure that out, expect more regulatory setbacks like New York's.

Waymo will eventually find its way back to New York. But it'll take longer than anyone expected, cost more than anyone planned, and require accepting compromises that seemed unnecessary six months ago.

That's the tax on disruption in a democracy.

Key Takeaways

- New York's legislature killed robotaxi legalization after Hochul failed to secure support, forcing Waymo's testing permit to expire March 31, 2025

- Waymo's $1.8 million lobbying effort since 2019 proved insufficient against organized labor opposition from taxi unions and driver advocates

- Public safety skepticism, worker displacement fears, and taxi industry opposition created political obstacles that corporate lobbying couldn't overcome

- Arizona and Texas became robotaxi havens due to friendlier regulatory culture, car-dependent geography, and less organized labor resistance

- The setback signals that American autonomous vehicle adoption will be slower and more geographically uneven than early predictions, clustering in favorable jurisdictions first

- Tech companies may need to fund worker transition programs and accept slower timelines to successfully navigate the political economy of labor-displacing innovations

Related Articles

- Robotaxis Meet Gig Economy: How Waymo Uses DoorDash to Close Doors [2025]

- Why Waymo Pays DoorDash Drivers to Close Car Doors [2025]

- Waymo's Remote Drivers Controversy: What Really Happens Behind the Wheel [2025]

- Tesla Stops Using 'Autopilot' in California: What Changed [2025]

- Texas Sues TP-Link Over China Links and Security Vulnerabilities [2025]

- FCC Equal Time Rule Debate: The Colbert Censorship Story [2025]

![New York's Robotaxi Reversal: Why the Waymo Dream Died [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/new-york-s-robotaxi-reversal-why-the-waymo-dream-died-2025/image-1-1771520850637.jpg)