Mark Zuckerberg Takes the Stand: Inside Meta's Most Consequential Legal Battle

On a Wednesday morning in Los Angeles, something remarkable happened in courtroom law. Meta's founder and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, walked into a Los Angeles Superior Court with visible tension in his movements. He wasn't there for a casual chat. He was there to defend his company against allegations that fundamentally challenge how we should think about social media's design and impact on teenagers.

This wasn't a Congressional hearing where he could talk around questions with practiced ease. This was a trial. A real one, with a jury watching every answer, every hedge, every moment of hesitation. The case itself was brought by a young woman identified as K. G. M. (Kaley) and her mother, alleging that Meta's products—Facebook and Instagram—were deliberately engineered to be addictive, causing severe psychological damage to minors.

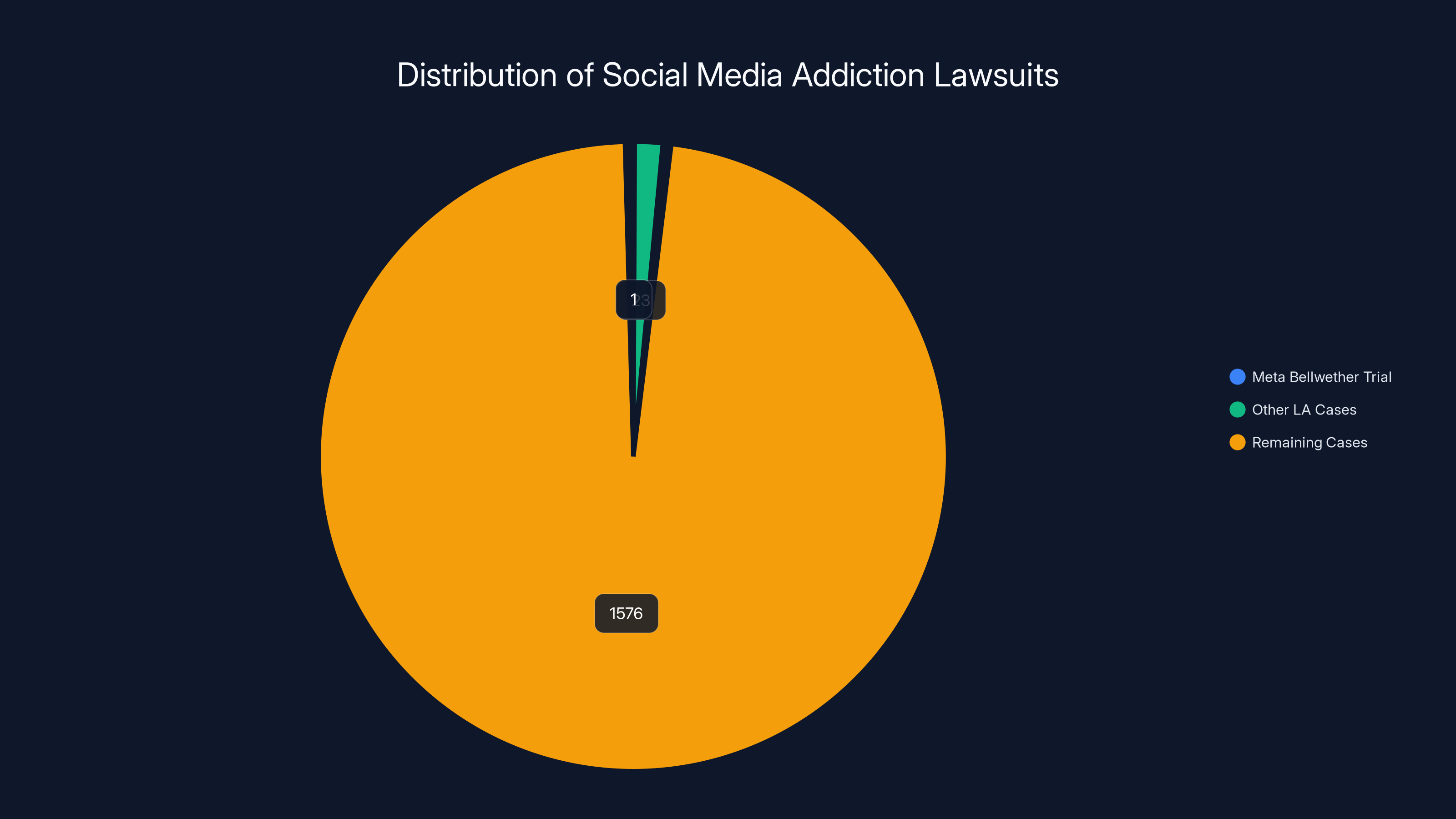

What made this trial historic isn't just the allegations. It's that this is the first "bellwether" case in what could become a tsunami of litigation. We're talking about roughly 1,600 similar lawsuits pending against Meta, YouTube, Snap, and TikTok, all following a similar legal strategy. The families claim their children fell victim to depression, body dysmorphia, eating disorders, and in some cases, suicide, after becoming hooked on apps designed to maximize engagement.

But here's where it gets interesting. These lawsuits deliberately sidestep Section 230, the legal shield that's protected tech companies from user-generated content liability for decades. Instead, they focus on the apps themselves, the algorithms, and the intentional design choices Meta made. That's a fundamentally different legal argument. And unlike previous tech trials, this one puts the burden on Meta to explain its own decision-making.

Zuckerberg's testimony—particularly his defensive answers and repeated evasions—provides a window into how Meta approaches these questions when they can't be deflected with marketing language or Congressional deflection tactics.

The Setup: A Landmark Trial That Signals Deeper Reckoning

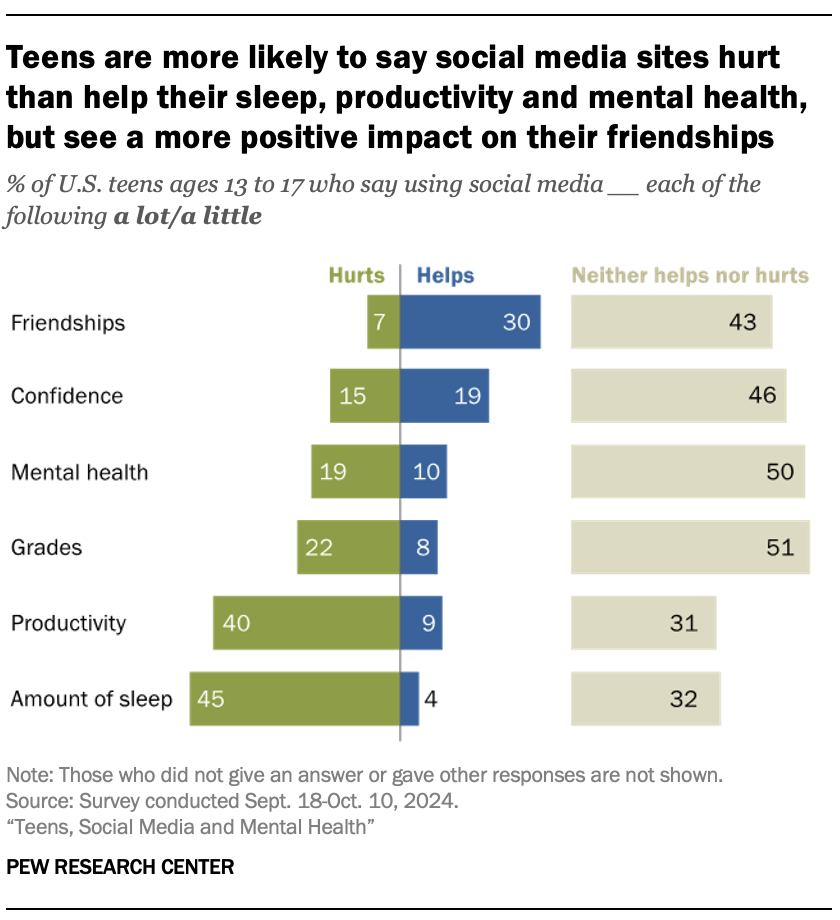

The timing of this trial reflects years of building pressure on big tech. Since the early 2020s, researchers, parents, and advocacy groups have raised increasingly serious questions about how social media affects teenage mental health. Studies have linked heavy social media use to anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. The allegations in Kaley's case aren't frivolous accusations—they're based on patterns documented in peer-reviewed research and internal Meta documents that have been leaked or discovered during discovery.

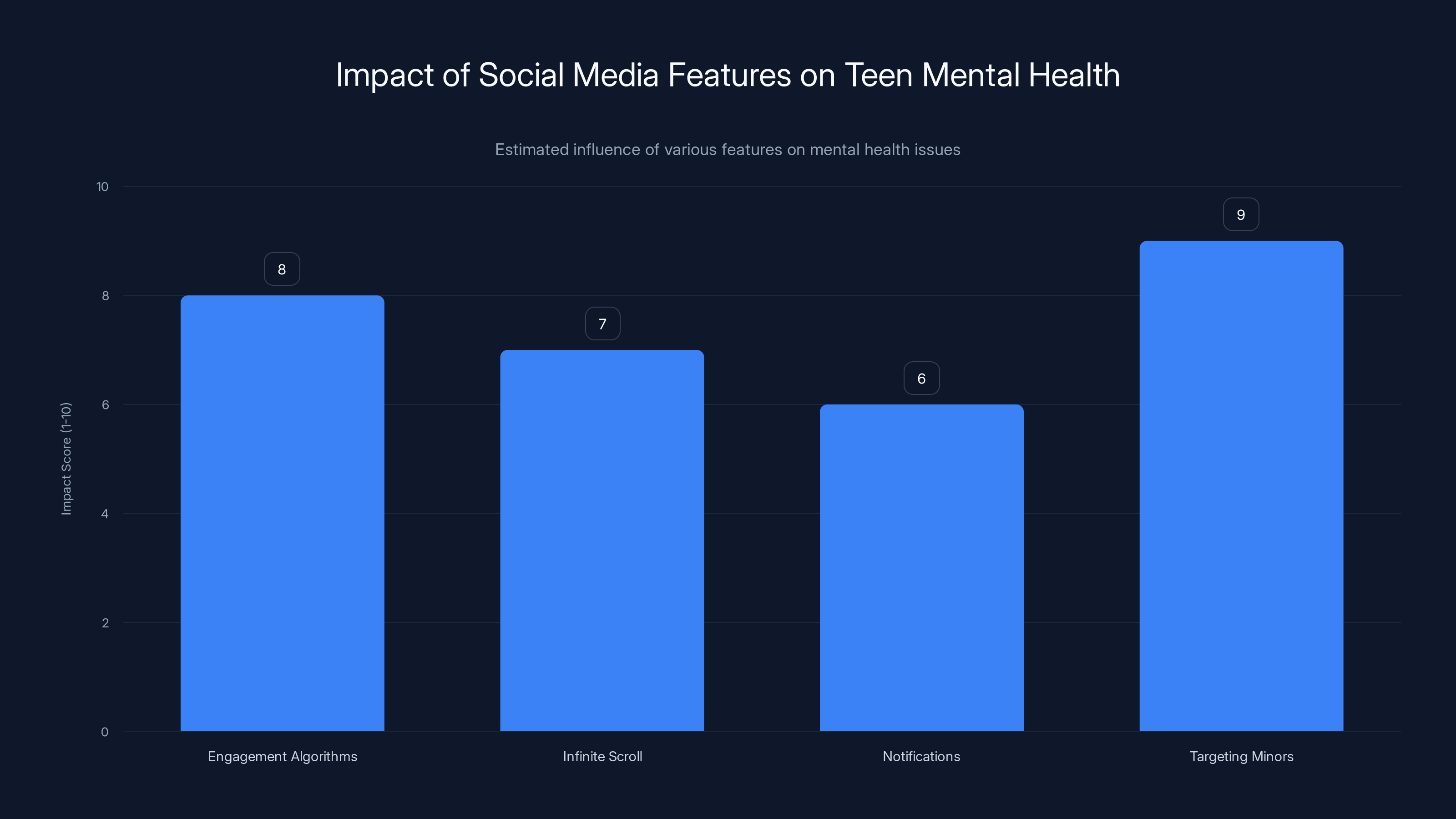

What makes this different from previous tech litigation is the legal strategy. Instead of arguing that Meta is liable for user-generated content (which Section 230 protects), Kaley's attorneys argue that the products themselves are the problem. The engagement-maximizing algorithms. The infinite scroll. The notification systems designed to pull users back. The targeting of minors with features proven to drive compulsive use. These are Meta's own design choices, not user-generated content.

The trial was overseen by Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Carolyn Kuhl, and it drew the kind of attention usually reserved for major criminal trials. The courtroom was packed. Media representatives lined the benches. Families whose children had been affected by social media addiction sat in the gallery, waiting to hear what Zuckerberg would say.

For Meta, the stakes couldn't be higher. A loss here doesn't just mean damages in this single case—it opens the door for thousands of others. It also sets a precedent that tech companies can be held accountable for the psychological and developmental harm their products cause to minors. From a business perspective, it challenges the fundamental model that drives Meta's $120+ billion in annual revenue: maximizing user engagement and time spent on platform.

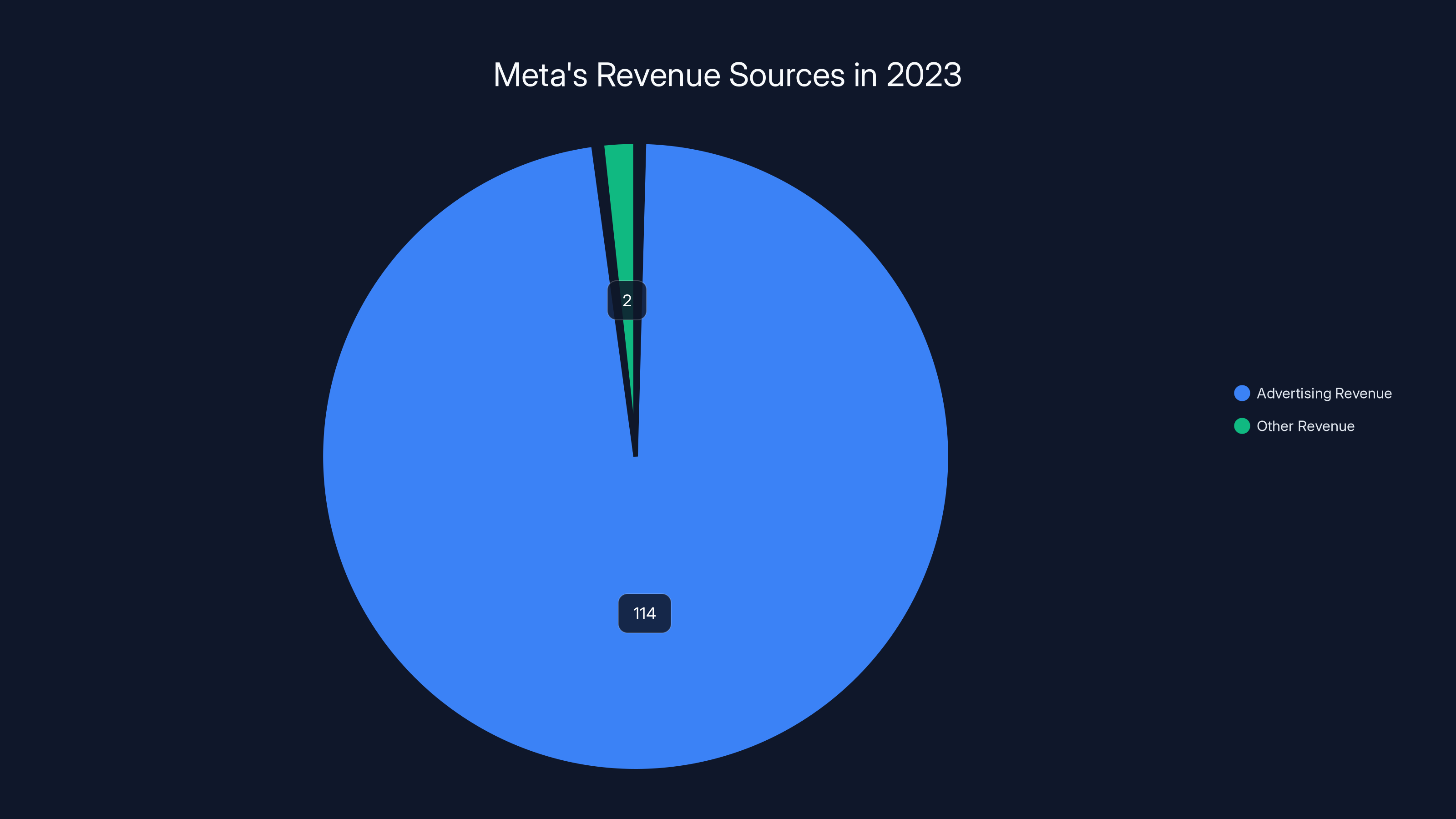

In 2023, Meta's revenue was overwhelmingly from advertising, comprising

Zuckerberg's Evasive Opening: When a Billionaire Walks Into Court

Zuckerberg arrived escorted by Department of Homeland Security officers—a detail that spoke volumes about the perceived threat level and the scale of the event. He walked into the courtroom at 9 a.m. sharp, his movements somewhat stiff, his demeanor controlled. This wasn't casual testimony. This was a carefully orchestrated appearance.

But within minutes, Kaley's lead attorney, Mark Lanier, began systematically dismantling Zuckerberg's credibility. Lanier's strategy was brilliant: take previous statements Zuckerberg had made under oath or in public, show documents that contradict them, and force him to explain the discrepancies.

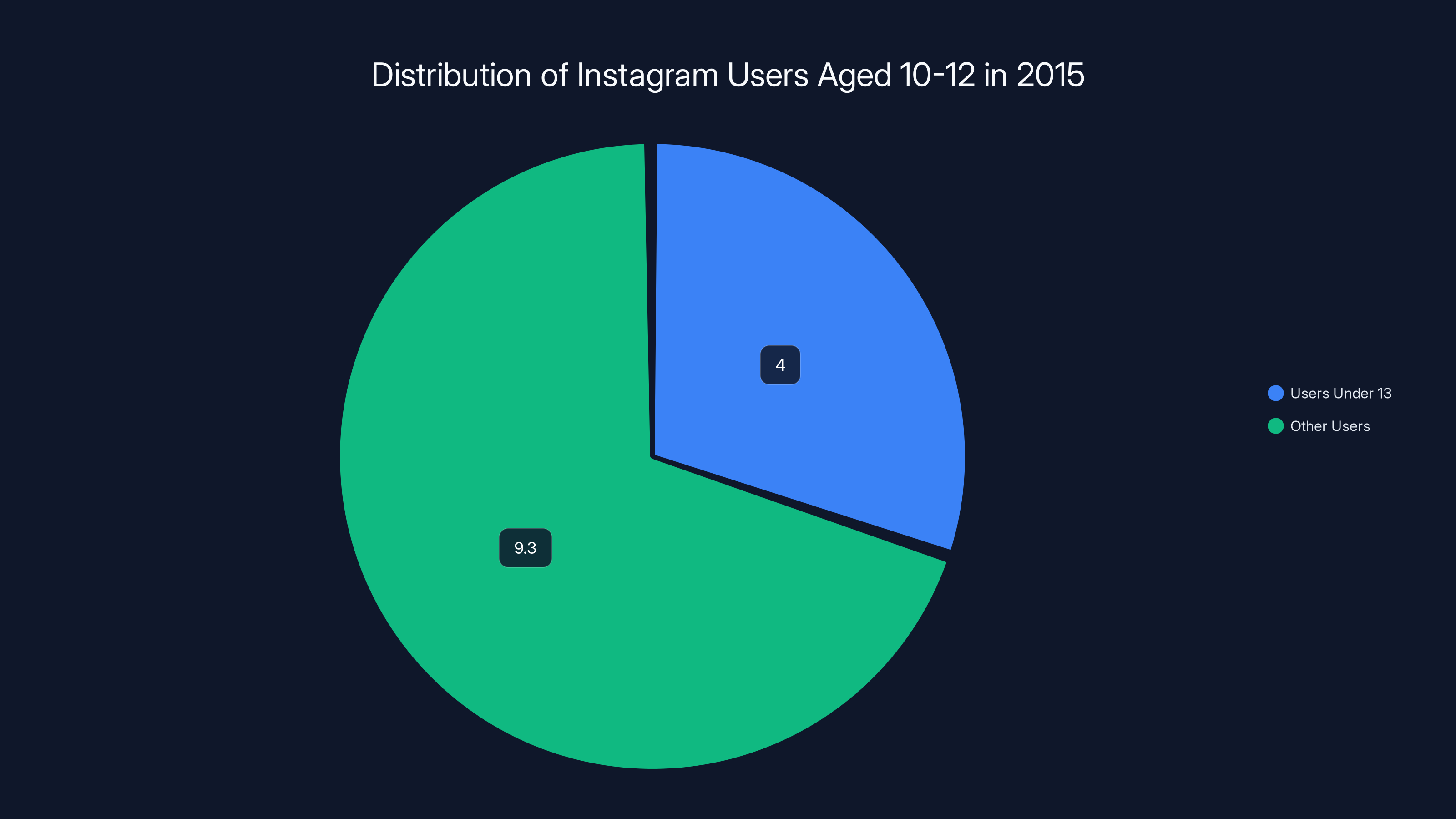

The first major attack came when Lanier referenced Zuckerberg's January 2024 Congressional testimony. Zuckerberg had testified that children under 13 are not allowed on Instagram. Lanier then produced internal Meta documents from 2015 showing that the platform had 4 million users under age 13—about 30 percent of all 10-to-12-year-olds in the United States at that time.

So either Zuckerberg didn't know this fact (damaging for a CEO), or he was misleading Congress (much worse). Zuckerberg's response was vague. He acknowledged the documents but tried to contextualize them as old. This pattern would repeat throughout his testimony: acknowledge when trapped, hedge when possible, claim to not remember when convenient.

The second major contradiction involved Meta's engagement goals. Zuckerberg had claimed in Congressional testimony that his team doesn't receive directives to increase the time users spend on the platform. Lanier countered by showing a 2015 goal-setting email from Zuckerberg himself that listed "increasing time spent" as the first item on Meta's priorities.

Again, the implications are significant. Either Zuckerberg was misleading Congress, or he doesn't fully understand his own company's strategic objectives. Neither looks good for someone claiming to lead a company with 3 billion monthly users and technology that influences global information flows.

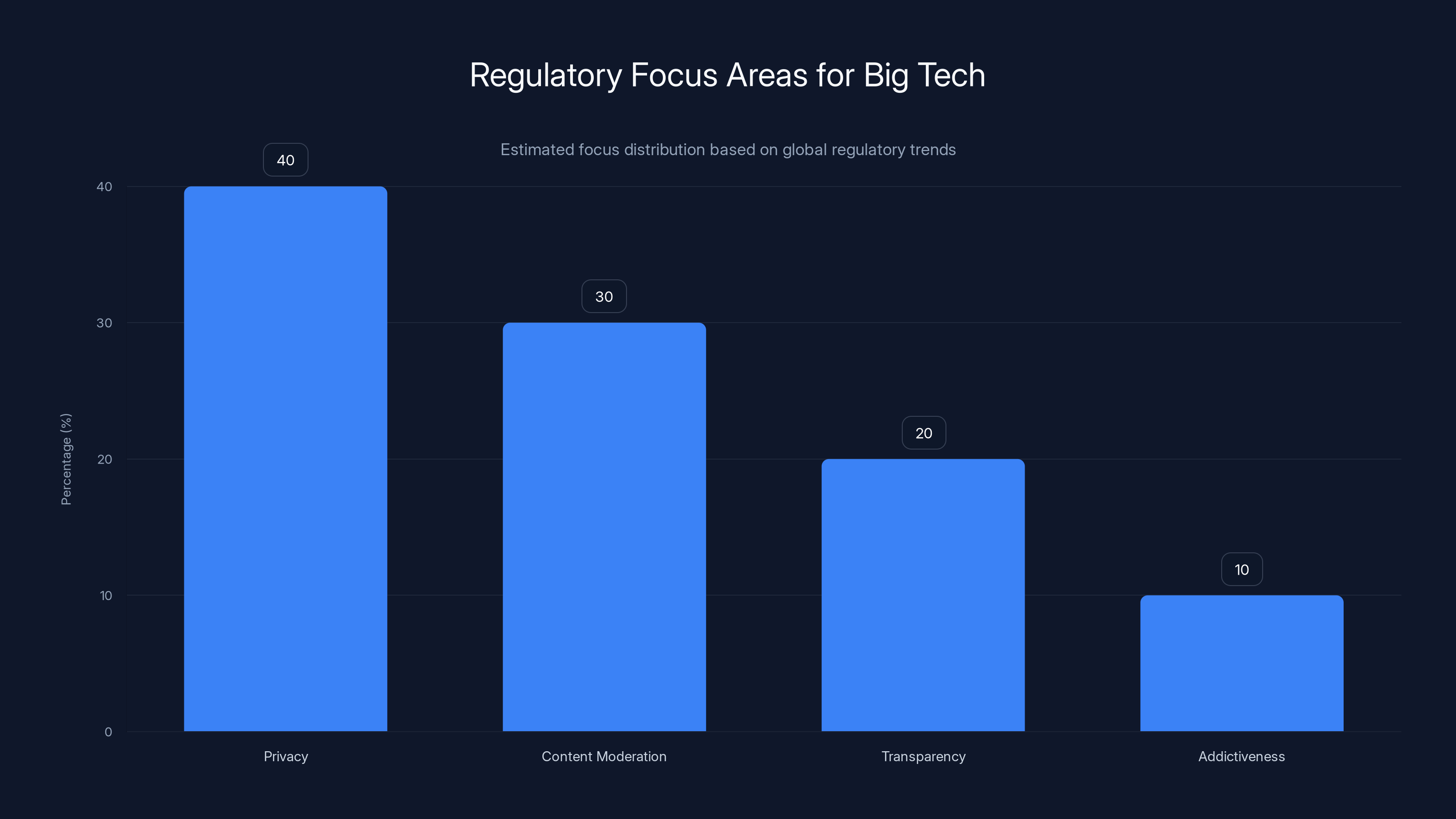

Estimated data shows privacy and content moderation as primary focus areas in global tech regulation, with addictiveness gaining attention.

The Credibility Crisis: Congressional Testimony vs. Court Reality

One of the most damaging moments in Zuckerberg's testimony came when Lanier quoted a comment Zuckerberg had made in an interview with Joe Rogan. Zuckerberg had said: "Because I control our company, I have the benefit of not having to convince the board not to fire me."

This seemingly off-hand comment actually carries significant legal weight. It establishes Zuckerberg as the ultimate decision-maker at Meta. He doesn't answer to shareholders or boards in the same way other CEOs do. He can make decisions unilaterally. When asked about this in court, Zuckerberg tried to backtrack, claiming his Rogan comment was merely a "simplified" version of the truth.

But that's exactly the kind of careful language that tells jurors something important: he's lawyered up. He's being coached. He's not speaking naturally. And if he's being coached on how to answer questions in court, jurors naturally wonder what he's being coached to conceal.

Lanier actually made this point explicitly during cross-examination. "You have extensive media training," Lanier said. "I think I'm sort of well-known to be pretty bad at this," Zuckerberg replied, getting a laugh from the courtroom. But the damage was done. The record now shows that Zuckerberg has communication strategists and media trainers who literally coach him on what answers to give, including in the context of testifying under oath.

This is significant because it sets a precedent. In previous trials, tech executives have been able to claim they simply didn't remember details or weren't involved in specific decisions. But Meta's documented efforts to prepare Zuckerberg for testimony undermines any claim that he's simply speaking candidly from memory. He's working from a script.

Throughout the afternoon session, Zuckerberg's evasiveness only increased. When asked if he knew Karina Newton, Instagram's head of public policy in 2021, he replied simply: "I don't think so, no." When presented with internal documents, he'd often say: "That's what the document says"—technically accurate but deliberately distancing himself from the content.

The Addiction Question: When Semantics Become Strategy

One of the most telling moments came when Lanier asked Zuckerberg a deceptively simple question: when something is addictive, people tend to do it more, right?

Zuckerberg hesitated. This should be a straightforward question. Addiction by definition involves compulsive behavior. But instead of agreeing, Zuckerberg said: "Maybe in the near term."

That single word—"maybe"—reveals everything about the stakes. Zuckerberg knows that if he acknowledges that Meta's products are addictive, he's admitting to harm. So he won't say it. He'll hedge. He'll parse. He'll use probabilistic language that technically leaves room for disagreement.

This pattern repeated throughout the testimony. Lanier would ask direct questions. Zuckerberg would respond with vague language: "It sounds like something I would have said," or "I'm not sure what you're trying to imply," or "That's what the document says." Never a clear admission. Never a direct statement that could be quoted in headlines the next day.

The addiction question is crucial because it goes to the heart of the case. If Meta intentionally designed products to be addictive—and addictiveness means people spend more time on them—then Meta is responsible for the psychological consequences of that addiction, especially for minors whose brains are still developing.

Research has shown that the adolescent brain continues developing until the early to mid-20s, with particular development in areas related to impulse control, reward processing, and long-term decision-making. This is why substance addiction is treated differently in minors than adults. And it's why social media addiction in teenagers is more damaging than the same behavior in adults.

Meta's entire engagement strategy depends on making apps that feel irresistible. The infinite scroll, the notification system, the algorithmic feed that shows you the content most likely to keep you scrolling—these aren't accidents. They're engineered features. Internal documents refer to maximizing "total teen time spent," which is explicitly about keeping teenagers on the platform longer.

When asked directly if Meta documents show an interest in maximizing teen engagement time, Zuckerberg replied: "That's what the document says." Translation: yes, but I'm not going to say it myself.

Estimated data suggests targeting minors and engagement algorithms have the highest negative impact on teen mental health.

The Engagement Argument: "Value" vs. "Addiction"

Throughout his testimony, Zuckerberg repeatedly fell back on the same argument: increased engagement reflects the genuine "value" that Meta's products provide. People spend more time on Facebook and Instagram because they find them valuable, not because they're addicted.

This is a crucial distinction for Meta's legal defense. If engagement equals value, then maximizing engagement is simply giving users what they want. If engagement equals addiction, then Meta is deliberately harming users for profit.

Zuckerberg knows this distinction matters, which is why he emphasized it constantly. But here's the problem: the distinction doesn't hold up under scrutiny. Research shows that people can find something both valuable and addictive. You can genuinely enjoy and value something that's also psychologically harmful, especially if your brain hasn't fully developed its impulse control systems.

Consider gambling. Casinos provide genuine entertainment and excitement. Some people value that experience. But nobody would argue that gambling addiction is just evidence of someone finding casinos valuable. It's an example of a genuinely desirable activity that can be structured in ways that exploit psychological vulnerabilities.

Meta's apps work similarly. They do provide genuine value—connection to friends, entertainment, information sharing. But they're also engineered to be maximally engaging, using techniques from game design, behavioral psychology, and neuroscience. The features that make them "valuable" are often the same ones that make them addictive.

Internal documents entered into evidence during the trial showed that Meta explicitly tested features for their ability to drive "time spent." The company literally A/B tests different versions of the app, measuring which variations keep users scrolling longer. This isn't passive observation of user behavior. It's active optimization toward a specific goal: maximum engagement.

When Lanier confronted Zuckerberg with this evidence, the response was telling. Rather than defending the practice or explaining why it's not problematic, Zuckerberg simply acknowledged that yes, Meta does measure and optimize for engagement. But optimizing for what users find valuable isn't the same as addicting them, he implied.

Except that's exactly what makes it addictive for adolescents. When you're 15 years old with an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain responsible for impulse control, long-term thinking, and risk assessment—an app engineered to maximize engagement is essentially a predatory product. It's engineered specifically to exploit the vulnerabilities of the teenage brain.

The Age Deception Problem: Kids Under 13 on Instagram

One of the most damaging revelations came through internal Meta documents showing the company knew millions of children under 13 were using Instagram, despite the app's terms of service prohibiting users under 13.

Lanier showed a 2015 internal estimate that Instagram had 4 million users under age 13, comprising roughly 30 percent of all 10-to-12-year-olds in the United States. This wasn't speculative. It was an internal estimate from Meta's own analytics.

Yet when Zuckerberg testified before Congress in January 2024, he stated clearly that children under 13 are not allowed on Instagram. Technically, that's true—the terms of service don't allow it. But the terms of service are meaningless if Meta knows millions of underage users are on the platform and does nothing to stop them.

In fact, internal documents suggest Meta does more than nothing. The company has features specifically designed to appeal to younger users. The stories feature—now ubiquitous across Meta's apps—was designed partly based on research into what teenage users find engaging. Reels, the short-form video feature that Instagram borrowed from competitors, is particularly attractive to younger users.

When asked about this directly, Zuckerberg suggested that Meta isn't responsible for user age misrepresentation. If younger kids lie about their age when signing up, that's not Meta's fault. The platform provides the tools to enforce the age restriction (email verification, etc.), so the company can claim it's doing what it can.

But this argument falls apart when you consider that Meta has every incentive to look the other way. A younger user is potentially a younger user for decades. Someone who becomes a heavy Facebook or Instagram user at age 11 is somebody Meta has locked in for potentially 70+ years of advertising exposure, data collection, and engagement metrics. From a business perspective, younger users are incredibly valuable.

Moreover, Meta has sophisticated tools for identifying user age and behavior patterns. The company knows which users are likely underage based on their activity, stated interests, and social connections. The fact that the company doesn't aggressively enforce age restrictions suggests it's not a priority.

Lanier made this point effectively: Meta could make age enforcement a priority if it wanted to. The company could require government ID verification, parental consent, or other barriers. But it doesn't, because younger users drive engagement metrics.

The Meta bellwether trial is one of 24 cases in LA, representing 1,600 total suits. Estimated data.

Mental Health at Scale: The Human Cost of Engagement Maximization

Beyond the legal arguments and testimony tactics, the trial raises a fundamental question about scale and responsibility. Meta has 3 billion monthly active users. Instagram alone has 2 billion. Even if the psychological effects of social media addiction are relatively modest for individual users, at that scale, the aggregate harm becomes enormous.

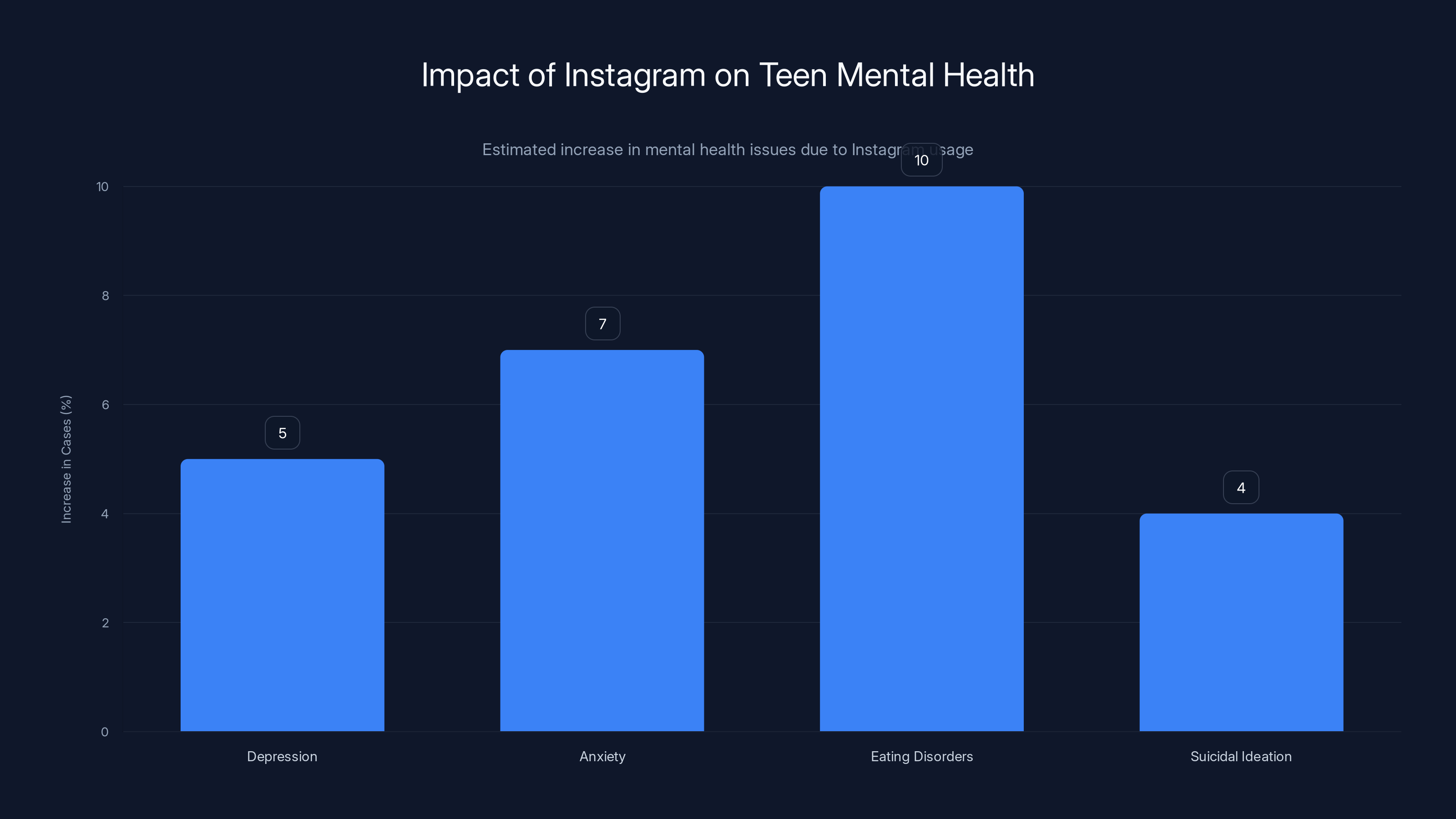

Consider the math: if Instagram causes even a 5 percent increase in depression rates among teenagers, that's millions of teenagers with increased depression directly traceable to Instagram's design. If the app increases eating disorder rates among girls by even 10 percent (and some studies suggest the effect is much larger), we're talking about hundreds of thousands of additional cases.

During the trial, the case of Kaley specifically illustrated these harms. According to her family, heavy use of social media platforms beginning in early adolescence contributed to severe depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. By her late teens, she was struggling with suicidal ideation. Whether social media directly caused these issues or significantly worsened them is an open question, but the correlation is clear in her case and in many others.

What makes this trial significant is that it's asking: is Meta responsible when it designs products specifically to maximize engagement with minors, knowing that some of those minors will experience severe psychological harm as a result?

From a legal perspective, this is a novel question. Tech companies have operated under Section 230 protection for decades, which has allowed them to disclaim responsibility for user-generated content. But this trial sidesteps that entirely. It focuses instead on Meta's own design choices and algorithmic decisions.

The company's engagement optimization strategies—the infinite scroll, the algorithmic feed that prioritizes content likely to generate strong reactions (whether positive or negative), the notification system designed to pull users back to the app—these are all Meta's decisions. Meta chose to implement these features. Meta chose to optimize for engagement. Meta chose to target these features toward teenagers specifically.

When the psychological costs of those choices become severe enough—depression, eating disorders, suicide—at what point does the company become liable? That's the question this trial is asking.

The Coaching Question: Authenticity vs. Legal Strategy

Lanier's observation that Zuckerberg has "extensive media training" and is being "coached" on what answers to give might seem like a minor point, but it actually goes to the heart of how we should interpret his testimony.

When an executive testifies in court, jurors expect to hear that person's genuine knowledge and understanding. They're entitled to assess whether the executive is being truthful, evasive, or misleading. But when that executive is reading from a script prepared by lawyers and communications strategists, the testimony becomes something else entirely: a carefully crafted legal document, not a factual statement from someone with direct knowledge.

Meta's communication strategy documents, which were entered into evidence, are remarkable in their specificity. The company literally coaches Zuckerberg on the exact language to use when answering difficult questions. The goal isn't to provide honest answers—it's to provide legally defensible answers that don't create additional liability.

For example, instead of saying "Yes, we optimize for engagement," Zuckerberg is coached to say "Our goal is to create valuable experiences for our users." These mean the same thing in practice, but the second phrasing is more defensible in court.

Instead of saying "Yes, we target teenagers specifically," he says "Instagram is designed for people 13 and older." Again, defensible but potentially misleading.

This coaching is perfectly legal, of course. Every executive who testifies in a major trial will have legal counsel advising them on how to answer questions. But the degree to which Meta's coaching is formalized and documented is notable. It suggests the company is treating this testimony as a legal maneuver rather than a genuine exchange of information.

Zuckerberg himself seemed aware of this tension. When Lanier pointed out the coaching, Zuckerberg tried to deflect with humor, claiming he's "well-known to be pretty bad at" media training. The courtroom laughed, which was exactly the intended effect—humanize the defendant, make him seem relatable, undercut the suggestion that he's being duplicitous.

But a courtroom laugh doesn't change the fact that Meta has a documented strategy for controlling Zuckerberg's testimony. It doesn't change the fact that his answers are carefully scripted. And it doesn't change the fact that when you're seeing carefully scripted testimony, you should be skeptical of its claims to represent genuine knowledge or belief.

In 2015, an estimated 4 million Instagram users were under 13, making up about 30% of all 10-to-12-year-olds in the U.S. (Estimated data)

Section 230 and the Novel Legal Strategy

To understand why this trial is genuinely groundbreaking, you need to understand Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Passed in 1996, Section 230 essentially says that online platforms aren't liable for content created by their users.

This provision has been fundamental to how the internet developed. Without Section 230 protection, every platform would be liable for every piece of user-generated content. That would make the internet as we know it essentially impossible to operate. Facebook couldn't moderate 3 billion users without being sued thousands of times daily for content it missed.

But Section 230 has also become a shield that tech companies hide behind. When Facebook makes changes to its news feed algorithm that suppress mental health resources and promote divisive content, they claim they're not liable because the algorithm is just a feature that users interact with, not content liability.

Kaley's lawsuit deliberately sidesteps this protection. Instead of suing Meta for content posted by other users, the lawsuit focuses on Meta's own products and design choices. The infinite scroll. The algorithmic feed. The notification system. These are all Meta's creation, not user-generated content. Section 230 doesn't protect them because Section 230 is about content, not product design.

This is brilliant legal strategy, and it's why the trial matters so much. If the courts agree that Meta can be held liable for harms caused by its product design (specifically the addictive design features targeting minors), it opens the door to entirely new categories of liability that Section 230 doesn't protect against.

Zuckerberg and Meta's attorneys clearly understood this, which is why the defense strategy focused so heavily on the "value" argument. If they can convince the jury that users choose to spend time on Meta's apps because they're valuable, not because they're addictive, then there's no basis for liability. The company would be providing a service that people want, not exploiting them.

But that argument only works if you ignore the wealth of evidence showing that Meta specifically engineers its products to be maximally engaging, and that this engineering exploits the developmental vulnerabilities of teenage brains. Zuckerberg's evasive testimony actually works against this argument. If the company is so confident that it's doing nothing wrong, why is the CEO being coached to avoid admitting basic facts about how his company works?

The Business Model Problem: How Meta Profits from Engagement

Underlying all of this is a fundamental business model question. Meta makes nearly all of its revenue from advertising. In 2023, the company earned approximately

Advertising revenue is directly tied to engagement. The more time users spend on Meta's platforms, the more ads they see, and the more data Meta has to target ads precisely. Every feature that increases engagement directly increases Meta's revenue.

This creates an inherent conflict of interest. If Meta could make its apps less addictive without decreasing engagement, it would. But it can't. For teenagers especially, the features that make the apps addictive are the same ones that drive engagement and therefore advertising revenue.

Consider the infinite scroll feature, which has become standard across social media. Infinite scroll is literally designed to exploit how the human brain handles novelty and rewards. It removes the friction of having to click "load more" or flip to the next page. This keeps users scrolling almost indefinitely, even when they're bored or wanting to stop.

Meta didn't invent infinite scroll, but it did choose to implement it on Facebook and Instagram. The company knows from internal testing that infinite scroll increases time spent. It also knows from user research that many users find the infinite scroll to be somewhat compulsive—they get stuck scrolling for hours when they intended to spend a few minutes.

But Meta can't remove the infinite scroll because it would decrease engagement and therefore advertising revenue. The feature is so fundamental to how the app works that users have simply accepted it as normal.

Similarly, algorithmic feeds work the way they do—prioritizing content likely to generate reactions—because reactions increase engagement. Likes, comments, and shares signal that a piece of content is interesting, so the algorithm shows it to more people. This is a virtuous cycle for engagement, but it has significant downsides.

Research shows that engagement-optimized algorithmic feeds tend to promote emotionally charged content, divisive political content, and misinformation. They also tend to promote content that triggers social comparison and FOMO (fear of missing out) in teenage users, exacerbating anxiety and depression.

Meta's internal research shows the company understands these harms. But because the advertising business model depends on engagement, the company can't fundamentally change how its algorithms work without accepting lower revenue. This is why change happens so slowly, and only when forced by regulatory pressure or litigation.

Zuckerberg's evasive testimony reflects this fundamental contradiction. He can't admit that Meta's products are addictive because that would require acknowledging that his company deliberately harms teenagers for profit. But he also can't deny it convincingly because the evidence is too overwhelming.

Estimated data suggests Instagram usage may increase depression by 5%, anxiety by 7%, eating disorders by 10%, and suicidal ideation by 4% among teenagers.

Expert Testimony and the Science of Social Media Harm

While Zuckerberg's testimony was evasive, the trial also included testimony from other witnesses and experts. These voices provided important context for evaluating Meta's claims.

Researchers who study social media have documented clear patterns of harm, especially for teenagers. A study from the American Psychological Association found associations between social media use and increased rates of anxiety, depression, and sleep problems in adolescents. A separate analysis of emergency room visits found increases in self-harm incidents correlated with peaks in social media usage.

What's particularly damaging for Meta is that the company's own internal research reaches similar conclusions. Leaked documents from Instagram showed that the company's research teams discovered the app was significantly harming teenage girls' mental health, particularly around body image issues. The research specifically identified that Instagram was "making body image issues worse" for roughly one in three teenage girls.

Despite this knowledge, Meta didn't make fundamental changes to how Instagram works. Instead, the company made cosmetic changes (like adding features to suppress likes in some countries) that don't meaningfully address the underlying problem. The core product remains essentially unchanged.

This knowledge-but-inaction is particularly damaging in litigation. It suggests not just negligence but willful disregard for documented harms. A company that knows its product is harming teenagers and chooses not to fix it is in a much worse legal position than a company that's simply unaware of the harms.

Zuckerberg's testimony didn't really address these expert findings head-on. Instead, he questioned their methodology, suggested correlation doesn't equal causation, or claimed that Meta's internal research was being misunderstood. These are technically valid points—causation is hard to prove in social science research—but they ring somewhat hollow when the company has specific knowledge of harms and hasn't addressed them.

The Regulatory Context: Where Do We Go From Here?

This trial doesn't happen in a vacuum. It's happening against a backdrop of increasing regulatory scrutiny of Big Tech companies globally.

The EU is implementing the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act, both of which impose strict requirements on how large platforms operate. The UK is developing Online Safety regulations. And in the United States, multiple states and the federal government are considering new legislation around tech platform regulation.

Most of this regulation focuses on privacy, content moderation, and transparency rather than explicitly on addictiveness. But the regulatory trend is clear: governments are losing patience with tech companies' self-regulation claims.

This trial adds significant momentum to that regulatory push. If a jury decides that Meta is liable for harms caused by its deliberately addictive design, it changes the regulatory conversation. It shifts from "tech companies should probably do more" to "tech companies can be held legally accountable for not doing more."

For Meta, that's a critical shift. The company has successfully lobbied against regulation for years by arguing that self-regulation is sufficient and that government intervention would stifle innovation. But if the courts impose liability for addictive product design, the company can't claim credible self-regulation is working.

Zuckerberg knows this, which is why his testimony was so carefully controlled. Every hedging response, every evasion, every reluctant acknowledgment of basic facts—these were all strategic choices designed to minimize liability while avoiding obvious perjury. But the strategy itself reveals the stakes.

Looking forward, expect several outcomes if this trial results in liability for Meta:

-

Settlement Negotiations: Meta will likely want to settle the thousands of pending cases rather than face trial after trial with similar results. These settlements could cost the company billions.

-

Regulatory Response: Governments worldwide will cite this trial as evidence that voluntary compliance is inadequate, accelerating regulatory action.

-

Product Changes: Meta might finally make meaningful changes to reduce addictiveness—removing infinite scroll, changing algorithmic prioritization, implementing genuine time limits.

-

Business Model Pressure: If engagement decreases, advertising revenue decreases. This could finally force Meta to develop alternative revenue models.

-

Industry Precedent: Other social media companies will face similar lawsuits with much stronger legal precedent.

For now, we're in the middle of this trial. Zuckerberg's testimony is complete, but the jury hasn't reached a verdict. Yet his evasive answers have already revealed something important: a company that knows what it's doing might cause harm but can't admit it because the business model depends on that harm.

Youth Mental Health Crisis: What the Data Actually Shows

Separate from the legal questions is the underlying public health crisis. Teen mental health in the United States has deteriorated significantly over the past decade, particularly among girls.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the percentage of high school students experiencing persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased from about 26 percent in 2010 to 42 percent in 2021. Among teenage girls specifically, the numbers are even more alarming—57 percent reported feeling sad or hopeless in 2021, up from 38 percent in 2010.

Similarly, emergency room visits for self-harm among teenage girls increased by roughly 50 percent between 2010 and 2018, according to hospital discharge data. Eating disorders have also increased significantly, with higher prevalence among girls exposed to social media.

The timing of these increases correlates strongly with smartphone and social media adoption. Smartphones became ubiquitous among teenagers around 2012-2014. Facebook and Instagram experienced explosive growth in teen adoption during the same period. And mental health deterioration accelerated right along with social media adoption.

This doesn't prove causation, of course. Multiple factors contribute to mental health trends, including economic uncertainty, political polarization, and the COVID-19 pandemic. But the correlation is hard to ignore.

What makes this important for the trial is that it establishes Meta's products didn't exist in a vacuum. They were introduced during a period of rapid change in teenage mental health and behavior. If Meta's products even partially contributed to these negative trends, that's a significant harm.

Zuckerberg's testimony touched on this only glancingly. When asked about mental health effects, he acknowledged that some research suggests correlations but disputed that causation has been proven. Technically, he's right—definitive proof of causation is difficult in social science research.

But that's a misleading standard. No one expects cigarette manufacturers to wait for perfect proof of causation before being held liable for lung cancer. Once the evidence of harm reaches a certain threshold, the burden shifts. The company has to prove its product isn't harmful, not the other way around.

For social media, we're arguably already at that threshold. The evidence is strong enough that reasonable people can conclude Meta's products contribute to teenage mental health deterioration. Whether a jury will reach that conclusion remains to be seen.

The International Angle: How This Trial Affects Global Regulation

While this trial is happening in Los Angeles, it has implications that extend worldwide. Tech companies operate globally, and legal decisions in the United States tend to influence regulation everywhere.

The EU, in particular, is watching closely. The Digital Services Act, which went into effect in 2024, has explicit provisions about protecting minors from addictive design. If this Los Angeles trial establishes that Meta is liable for addictive design, it strengthens the EU's legal position in pursuing enforcement actions.

Similarly, UK regulators have signaled they're interested in holding platforms accountable for harms to minors. An unfavorable verdict for Meta in Los Angeles would provide precedent and political cover for stricter UK regulation.

Meta itself has made clear that it's concerned about global regulatory implications. The company's public statements about this trial have been vague, but Meta's internal communications (some revealed during discovery) show significant concern about setting precedent that could trigger stricter global regulation.

This is why the company is fighting so hard, and why Zuckerberg's testimony, despite its evasiveness, was crucial. A loss here doesn't just mean liability for this one case. It means confirming that tech companies can be held accountable for product design choices that harm minors. Once that principle is established, it applies globally.

For developing countries especially, this has significance. Companies like Meta have disproportionate influence in countries with less robust regulatory frameworks. If established legal systems like the US courts hold Meta accountable, it creates pressure for similar accountability globally.

Conversely, if Meta wins this trial, it signals that despite decades of research on social media harms and despite internal Meta documents acknowledging those harms, the company can still avoid liability by hiding behind vague claims about "value" and "user choice."

What Comes After Verdict: Immediate and Long-term Consequences

Regardless of the trial's outcome, significant consequences will follow.

If Meta loses, expect:

Immediate Effects: Meta will likely file appeals, seeking to overturn or significantly reduce any judgment. But the company will also face mounting pressure to settle the thousands of pending similar cases. A settlement could involve both monetary damages and product changes.

Regulatory Response: The judgment will be cited in congressional hearings, state regulatory proceedings, and international regulatory discussions. Expect accelerated movement toward stricter regulation of social media platforms.

Advertiser Response: Some advertisers concerned about brand reputation might reduce spending on platforms perceived as harmful to minors. This could impact Meta's revenue.

Product Pressure: Meta will face intense pressure from parents, advocates, and potentially regulators to make meaningful changes to reduce addictiveness. The company might face requirements to implement stronger age-gating, remove infinite scroll, or change algorithmic prioritization.

If Meta wins, expect:

Regulatory Acceleration: A Meta victory would likely accelerate regulatory action, as governments recognize that litigation alone won't solve the problem. Lawmakers might become more aggressive in pushing for legislation.

Industry Precedent: Other social media companies would cite the verdict as evidence they're not liable for addictive design, emboldening them to resist pressure for changes.

Continued Mental Health Concerns: Without legal accountability or regulatory pressure forcing change, the underlying issues driving this lawsuit would persist.

Settlement Trends: Snap and TikTok already settled this case, suggesting that even companies confident in their legal position might find settlement preferable to continued litigation and reputational damage.

In either scenario, the trial has already achieved one important outcome: it's forced public examination of Meta's design choices and their effects on teenagers. Zuckerberg's evasive testimony has been widely covered, and the internal documents showing Meta's knowledge of harms have been entered into the public record.

In some sense, the trial's greatest impact might not be the verdict but the visibility it brings to questions that should have been addressed years ago. What responsibility do tech companies have for the psychological effects of their deliberately addictive products? How should we regulate tech companies to prevent harm to minors? Can companies that profit from engagement be trusted to self-regulate?

These questions will persist regardless of this trial's outcome.

FAQ

What is the meta social media addiction trial about?

The trial involves allegations that Meta's platforms (Facebook and Instagram) were deliberately engineered to be addictive, causing severe psychological harm to teenagers. The plaintiff, a young woman identified as K. G. M., alleges that her compulsive use of these platforms beginning at a young age led to depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and suicidal ideation.

How does Meta's engagement strategy relate to these allegations?

Meta's business model depends almost entirely on advertising revenue, which is directly tied to user engagement and time spent on platforms. Internal documents show the company optimizes virtually every feature—infinite scroll, algorithmic feeds, notifications—to maximize engagement. Critics argue these features are specifically engineered to be addictive, particularly for teenagers whose brains are still developing impulse control and reward processing centers.

What is a bellwether trial and why does this one matter?

A bellwether trial is the first case selected from a large pool of similar lawsuits to establish a precedent. This Meta trial is the first of approximately 24 similar cases in the Los Angeles court system and represents roughly 1,600 total social media addiction suits. The outcome here will significantly influence how other cases are resolved and could lead to settlements affecting billions of dollars in damages.

Why is Section 230 protection important to this case?

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has historically protected tech platforms from liability for user-generated content. However, this lawsuit deliberately sidesteps Section 230 by focusing on Meta's own product design choices (algorithms, infinite scroll, notifications) rather than user-created content. This novel legal strategy could establish liability in ways Section 230 doesn't protect against.

What did Zuckerberg's testimony reveal about Meta's practices?

Zuckerberg's testimony was notably evasive, with the CEO repeatedly using vague language and acknowledging facts reluctantly when confronted with documents. Key revelations included: Meta knew millions of children under 13 used Instagram despite age restrictions, Meta explicitly optimizes for "time spent" to drive engagement, and the company has communication strategists coaching him on testimony. His evasiveness suggested the company understands the problematic nature of its practices but can't openly acknowledge them.

What are the potential consequences if Meta loses this trial?

If the jury finds Meta liable, expect several outcomes: Meta would likely settle the thousands of pending similar cases for potentially billions of dollars, regulatory agencies worldwide would cite the verdict to justify stricter regulation, the company would face pressure to make meaningful product changes to reduce addictiveness (possibly removing infinite scroll or changing algorithmic prioritization), and the precedent would embolden similar lawsuits against other tech companies.

What role does teenage brain development play in these allegations?

The adolescent brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex responsible for impulse control and long-term decision-making, continues developing into the mid-20s. This developmental vulnerability makes teenagers significantly more susceptible to addictive product design than adults. Meta's apps are specifically engineered to exploit this vulnerability through features like infinite scroll, algorithmic feeds that prioritize engaging content, and notification systems designed to pull users back to the platform.

How has Meta's internal research documented social media harms?

Leaked internal documents from Meta show the company discovered that Instagram was "making body image issues worse" for about one in three teenage girls. Despite this knowledge, Meta made only cosmetic changes and didn't fundamentally alter how Instagram operates. This knowledge-but-inaction is particularly damaging in litigation.

What does this trial mean for global regulation of social media?

The trial has immediate implications for regulation worldwide. The EU's Digital Services Act explicitly addresses addictive design, and a U. S. court verdict establishing Meta's liability would strengthen regulators' positions in pursuing similar enforcement actions globally. UK regulators watching closely are already considering stricter rules. A precedent here could accelerate international regulatory action significantly.

Is there scientific evidence linking social media to teen mental health problems?

Yes, substantial research correlates heavy social media use with increased anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and self-harm in teenagers. Emergency room visits for self-harm among teenage girls increased roughly 50 percent between 2010 and 2018, correlating with smartphone and social media adoption. While proving causation is challenging in social science research, the evidence of correlation and harm is well-established in academic literature.

What makes this lawsuit different from previous tech litigation?

This case sidesteps Section 230's content liability protections by focusing on product design rather than user-generated content. Additionally, it leverages Meta's own internal research showing knowledge of harms to teenagers. This combination—a novel legal strategy plus documented knowledge of harm—positions it differently from previous tech lawsuits that often relied on harder-to-prove theories about content moderation or platform responsibility for user speech.

Key Takeaways

- Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg's trial testimony was notably evasive, using vague language and admitting facts reluctantly when confronted with internal documents.

- Internal Meta documents show the company explicitly optimizes for 'time spent' and knew millions of children under 13 used Instagram despite age restrictions.

- This is the first of approximately 24 bellwether cases in Los Angeles affecting 1,600 total pending social media addiction lawsuits—a potential precedent with massive implications.

- The trial sidesteps Section 230 legal protections by focusing on Meta's own product design (algorithms, infinite scroll, notifications) rather than user-generated content.

- Research shows teenage mental health deteriorated significantly coinciding with smartphone and social media adoption, with self-harm emergency visits increasing 50% between 2010-2018.

- Meta's business model creates inherent conflict of interest: the company profits directly from maximizing engagement, making it unlikely to voluntarily reduce addictiveness without legal or regulatory pressure.

Related Articles

- Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Social Media Addiction: What Changed [2025]

- Zuckerberg Takes Stand in Social Media Trial: What's at Stake [2025]

- Social Media Giants Face Historic Trials Over Teen Addiction & Mental Health [2025]

- Meta's Parental Supervision Study: What Research Shows About Teen Social Media Addiction [2025]

- Nvidia and Meta's AI Chip Deal: What It Means for the Future [2025]

- Cybersecurity & Surveillance Threats in 2025 [Complete Guide]

![Zuckerberg's Testimony in Social Media Addiction Trial: What It Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/zuckerberg-s-testimony-in-social-media-addiction-trial-what-/image-1-1771468570091.jpg)