Understanding the FCC's Equal Time Rule and the Colbert Controversy

There's a rule sitting in the FCC's playbook that almost nobody talks about. Most people have never heard of it. Even fewer understand how it actually works. And yet, in early 2025, that obscure regulation became the center of a political firestorm that shut down a late-night interview and sparked a massive conversation about free speech, broadcast regulation, and government overreach.

The rule in question is called the equal time rule, and while it sounds boring and bureaucratic, its implications are anything but. When FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr started wielding this rule against broadcast networks, he didn't just target Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert. He sent a message to every broadcaster in America: be careful what you air, or face regulatory consequences.

What makes this story particularly significant isn't just the immediate fallout. It's what the equal time rule really does, how it's being enforced, and what it means for the future of broadcast journalism and political speech on television. The Colbert situation is a window into a much larger debate about regulatory power, free speech, and whether government agencies should be deciding what Americans see on TV.

Let's walk through exactly what happened, why the FCC is involved, and what this means for the broadcast industry moving forward.

The Timeline: How CBS Killed Colbert's Interview

In early 2025, Stephen Colbert's team arranged an interview with James Talarico, a Texas state representative who was running for Congress. Talarico's campaign was in its early stages, and the interview was meant to help introduce him to a national audience. The "Late Show" team produced the segment, and it was ready to air.

Then things got weird. CBS told Colbert that the interview couldn't air. Not because of content quality, not because it was offensive, and not because it was boring. The network made the decision based on fears about FCC enforcement of the equal time rule.

Why? Because FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr had recently sent a letter to CBS questioning their coverage and hinting at potential regulatory consequences. Carr's letter wasn't a formal complaint or a legal action. It was a warning shot. And it worked.

CBS, facing the prospect of expensive legal battles or regulatory headaches, decided it wasn't worth the risk. Better to kill the interview than deal with potential FCC enforcement actions. Colbert responded by doing what any late-night host would do: he made it public and turned it into content. He aired a segment explaining why the interview didn't air, which became bigger news than the original interview would have been.

This is where the story gets really interesting. Because now we're not just talking about what the equal time rule says. We're talking about what it does when regulatory threats are deployed strategically.

What the Equal Time Rule Actually Is

Let's get the basics straight, because the equal time rule is genuinely confusing, and most explanations online make it worse.

The equal time rule dates back to 1927 and was codified into the Communications Act of 1934. The basic idea was simple: if a broadcaster gives airtime to one candidate, they have to offer "equal" time to opposing candidates. It's a fairness mechanism, in theory, designed to prevent broadcasters from monopolizing political speech.

But here's where it gets complicated. The rule doesn't apply to news coverage. It doesn't apply to interviews conducted by journalists. It specifically applies to non-news programming. So if a station runs a news report about a candidate, equal time doesn't kick in. If a station hosts a debate, equal time doesn't apply. But if a station gives airtime to a candidate in a way that isn't explicitly "news," the rule can potentially trigger.

The FCC is supposed to enforce this rule, but historically, they barely do. It's on the books, technically enforceable, but largely ignored. Which is why most broadcasters don't think about it regularly. It's a sleepy regulation that everyone acknowledges exists but nobody expects to be enforced.

That changed when Brendan Carr became active on the FCC.

The Core Question: Is Colbert a News Interview?

Here's the key argument in the Colbert situation. CBS claimed that the interview with Talarico wasn't being aired as part of the "Late Show with Stephen Colbert" because that's entertainment, not news. If it had aired on "60 Minutes" or as part of a legitimate news segment, the equal time rule wouldn't apply.

But Carr's threat suggested that Talarico's appearance on a late-night show, regardless of whether it was meant to be "news," could still trigger equal time obligations. Under this interpretation, the network would need to offer equivalent time to Talarico's opponents.

The problem with this argument is that it's never been clearly tested or defined in FCC enforcement. Carr wasn't issuing a formal complaint. He was hinting at potential enforcement. And that hint was enough to spook CBS.

What makes this more troubling is that equal time obligations, if taken to their logical extreme, could require networks to give free airtime to every candidate in a race. If a network gives a major candidate five minutes on a talk show, do they have to give opposing candidates five minutes each? What if there are fifteen candidates? Do they all get five minutes?

These aren't academic questions. The practical implications are enormous. If networks face potential regulatory action for interviewing candidates, they'll just stop interviewing candidates. That's not good governance. That's suppression through ambiguity.

Why Brendan Carr Is Weaponizing the Rule

Brendan Carr's aggressive deployment of the equal time rule has been described by media scholars and policy experts as a "chilling effect" on broadcast speech. A chilling effect doesn't require actual enforcement. It just requires enough uncertainty that people censor themselves.

Carr had previously sent letters to other networks questioning their coverage. He was signaling that the FCC, under his influence, was going to start paying attention to who got airtime and whether equal time obligations were being met.

The pattern is troubling because it creates a situation where regulatory threats can suppress speech without formal legal action. CBS didn't need to be sued. CBS didn't need a formal complaint. A letter from an FCC commissioner was enough.

This raises a fundamental question about regulatory power. The FCC is supposed to enforce rules in a neutral, content-agnostic way. But when an agency starts selectively enforcing against certain speakers or certain candidates, or when its threats are clearly motivated by political preference, that's regulatory overreach.

There's also a historical element worth noting. The equal time rule has been controversial for decades because it arguably conflicts with free speech principles. If the government can force broadcasters to give equal time to all candidates, is that compatible with editorial freedom? Most contemporary legal scholars argue it's not, which is why the rule has been narrowed significantly since the 1970s.

But Carr seems intent on reviving its aggressive enforcement.

The Chilling Effect: How Regulatory Threats Suppress Speech

A chilling effect is what happens when people stop doing something legal because they're afraid of government consequences. They don't need to be prosecuted. They just need to be scared enough that self-censorship seems like the safer option.

Carr's letters to broadcasters accomplished exactly this. Networks that might have otherwise interviewed political candidates now face the prospect of expensive regulatory battles. The calculation becomes simple: is an interview worth the potential legal liability?

For CBS, the answer was no. Better to kill the Colbert interview than risk an FCC enforcement action, even if that action was unlikely to succeed.

But this has broader consequences. If networks start avoiding political interviews because they're worried about equal time obligations, then candidates have fewer platforms to reach voters. The public gets less political information. Journalism becomes riskier. These are the downstream effects of regulatory uncertainty.

The historical precedent here is worth understanding. In the 1960s and 1970s, the equal time rule was enforced more aggressively. That enforcement actually drove networks away from political coverage. Stations would skip news about elections because they were worried about triggering equal time obligations. This wasn't good public policy. It actually reduced democratic discourse, which was the opposite of what the rule was supposed to accomplish.

Carr's current approach seems headed toward the same outcome.

CBS's Calculation: Risk vs. Reward

From CBS's perspective, the Colbert decision makes sense even if the underlying policy is questionable. Here's why.

The network faces several risks if they air the Talarico interview:

First, there's potential FCC enforcement. Even if Carr's threat wouldn't ultimately succeed in court, the process itself is expensive. FCC enforcement actions require lawyers, regulatory expertise, and years of potential litigation.

Second, there's reputational risk. If CBS airs the interview and then the FCC investigates, that becomes a news story. "Network fined for violating equal time rule" is bad press.

Third, there's the precedent. Once the Colbert interview airs, Carr can point to it as evidence of the network's willingness to violate equal time obligations. That makes future FCC actions more likely.

On the other hand, killing the interview has relatively few costs from CBS's perspective. It's one interview on one show. Colbert can make a funny bit out of it (which he did). The network avoids all regulatory entanglement.

But this calculation assumes that networks will continue to make these decisions, and they will. If the equal time rule is actively enforced, broadcast networks will simply become less willing to feature political candidates. That's not speculation. That's what happened before.

It's also worth noting that CBS's decision is particularly notable because the interview was scheduled to air on a late-night comedy show, not a news program. The Colbert Late Show isn't primarily a news outlet. It's an entertainment program with a host known for sharp political commentary. But under Carr's interpretation, even entertainment programming featuring political candidates could trigger equal time obligations.

This expands the rule's reach far beyond what was historically understood.

The Broader Regulatory Pattern

The Colbert situation isn't Carr's first brush with broadcast regulation and political speech. He had previously sent letters to Jimmy Kimmel's network after Kimmel made on-air comments about a political candidate. That letter also implied potential equal time rule violations.

Kimmel's situation is slightly different from Colbert's because Kimmel is primarily an entertainment host who makes political jokes and commentary. But Carr's logic suggests that even comedic commentary about political candidates could trigger regulatory scrutiny.

This is where the pattern becomes concerning. If FCC commissioners can send letters threatening enforcement over every mention of a political candidate in entertainment programming, the chilling effect becomes massive. Basically every late-night show, every comedy program, every entertainment segment featuring any discussion of politics could face potential regulatory consequences.

But that's not how the equal time rule is supposed to work. The rule was designed for specific situations where candidates were given airtime for campaign purposes. It wasn't designed to regulate comedy or entertainment commentary.

Carr's approach essentially expands the rule far beyond its original scope by threatening enforcement in situations where it has never been applied before.

How Other Broadcast Networks Are Responding

The Colbert incident has set off alarm bells across the broadcast industry. Networks are now more cautious about political content, particularly content featuring political candidates.

Some broadcasters are reportedly consulting with regulatory lawyers more frequently. Others are developing more rigorous policies for when and how they can feature political candidates. These aren't policies mandated by law. They're precautionary measures designed to avoid regulatory entanglement.

The risk here is that broadcast networks become overly cautious. If networks decide that any interview with any political candidate is too risky, then candidates lose a major platform for reaching voters. This particularly affects lesser-known candidates who rely on broadcast media to build name recognition.

When regulatory threats suppress this kind of coverage, it potentially undermines democratic participation. Voters have less information about candidates. Political discourse becomes narrower. Less established candidates have fewer platforms.

This is the irony of the equal time rule. It was supposed to protect democratic discourse by ensuring equal access. But aggressive enforcement actually reduces discourse by making broadcasters avoid the topic entirely.

The First Amendment Question

There's a fundamental constitutional question lurking beneath all of this. The First Amendment protects freedom of speech, and that protection extends to broadcasters. But the FCC has regulatory authority over broadcasters because they use public airwaves.

This creates a tension between editorial freedom and regulatory authority. Should the government be able to tell broadcasters who they can and cannot feature in their programming? Most contemporary First Amendment scholars say no, with some exceptions for specific, narrow situations.

The equal time rule exists in this gray zone. It's a content regulation imposed on broadcasters, but it was originally justified as a fairness doctrine designed to serve the public interest. However, the Supreme Court has been skeptical of fairness doctrines in recent years, and many scholars argue that the equal time rule is constitutionally questionable.

If the rule is enforced aggressively, it will almost certainly face legal challenges. The question is whether those challenges will succeed. That depends on how courts interpret the FCC's authority and how they balance broadcaster free speech against regulatory authority over the airwaves.

What's clear is that Carr's current approach will eventually trigger legal tests. When it does, the outcome will determine whether aggressive equal time enforcement is constitutionally permissible.

The Political Context: Why This Matters Now

The timing of Carr's aggressive equal time enforcement isn't random. The rule is being revived precisely because political campaigns are gearing up. By threatening enforcement, Carr is sending a signal to broadcasters about what kind of political coverage is acceptable.

Some observers argue that Carr is essentially using regulatory authority to suppress coverage of certain candidates or viewpoints. Whether that's true depends on whether his enforcement is even-handed. If Carr only threatens action against coverage of one political party or one set of candidates, that would suggest weaponization. If he's enforcing the rule regardless of the candidate's party affiliation, that would suggest neutral enforcement.

The problem is that we don't have enough data yet to determine which is the case. But the selective nature of his letters (targeting late-night hosts known for left-leaning commentary) does raise questions.

What's undeniable is that regulatory threats have enormous power. CBS killed an interview because of the threat, not because of any actual violation or formal enforcement action. That's the chilling effect in action.

Meta's Facial Recognition Play: Privacy Meets Technology

While the broadcast world was dealing with the FCC's chilling effect on speech, another major story was developing in the social media and privacy space. Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, was reportedly preparing to launch facial recognition features on its smart glasses.

This technology would allow the glasses to identify people in the wearer's field of view and overlay information about them. The feature could theoretically identify friends, celebrities, or other notable people and display information about them in real time.

The privacy implications are enormous. Facial recognition technology has become increasingly controversial because of its potential for surveillance and misuse. Civil liberties organizations have documented numerous cases where facial recognition has been used to harass, stalk, or discriminate against individuals.

Meta's deployment of facial recognition in wearable devices raises the stakes significantly. A smartphone camera can take pictures of people without their knowledge, but it requires deliberate action. Smart glasses worn on someone's face operate passively. They're constantly recording and potentially identifying people.

The question of consent becomes critical. If you're walking down the street wearing smart glasses with facial recognition, are you entitled to recognize and catalog every person you encounter? What about their right to privacy? What about their right not to be identified and cataloged without consent?

Meta's apparent strategy is to deploy the technology quietly while privacy advocates are distracted by other issues. The Colbert situation, the broader FCC regulatory debates, and other high-profile tech news stories create an opportunity for Meta to move forward with facial recognition without as much scrutiny.

But the technology itself is arguably more significant than any of those other stories. If facial recognition becomes standard in wearable devices, the implications for privacy and surveillance are profound. Every interaction could be recorded and identified. Every encounter could be tracked.

Privacy organizations are pushing back, but they face a massive challenge. Unlike broadcast regulation, where the FCC has clear authority, there's no obvious regulatory mechanism for controlling facial recognition in wearable devices. The technology exists in a regulatory gray zone.

Apple's reported development of AI-powered glasses suggests that this space will become increasingly competitive. If multiple companies are developing smart glasses with advanced AI capabilities, the market pressure to include facial recognition features will be significant. First-mover advantage might go to whichever company captures the most useful data.

Meta's approach reflects a broader pattern in tech: deploy first, ask permission later. By the time regulators or privacy advocates catch up, the technology is already embedded in millions of devices.

Apple's March Gadget Plans: AI Glasses, Pendants, and More

Apple has a major event scheduled for early March, and the rumor mill suggests it could be one of the most significant Apple announcements in years. The focus appears to be on AI-powered hardware rather than software.

Reports suggest Apple is planning to launch AI-powered glasses, potentially a new wearable pendant device, and new versions of Air Pods with advanced AI capabilities. The glasses would likely use AI for real-time translation, information overlays, and other smart features.

What's interesting about Apple's approach is that it seems designed to differentiate from Meta. Where Meta is emphasizing facial recognition and passive surveillance capabilities, Apple appears to be focusing on individual utility features. The glasses might help you translate foreign language conversations in real time, or provide information about your surroundings without requiring facial recognition of other people.

The pendant device is particularly intriguing. Rumors suggest it could be a small AI assistant that users can carry with them, separate from their phone. This would represent a significant shift in how Apple thinks about AI. Instead of AI being primarily a feature of your phone, it would be a standalone device.

Apple's Air Pods already have some AI capabilities, but next-generation versions might include more advanced features. The earbuds could offer real-time translation, personal assistant capabilities, or health monitoring.

What Apple notably won't be showing off at the March event, at least based on current rumors, is the AI gadgets they're actually working on for the longer term. Apple reportedly has AI glasses in development that could come in future generations, but those aren't expected for several years.

The distinction between what Apple shows now (incremental AI features in existing products) and what they're actually developing (more ambitious AI hardware) reveals something important about the state of AI technology. The flashy, sci-fi applications of AI are still years away. What we're getting now is AI features bolted onto existing products.

But that's still significant. If Apple can successfully integrate AI into glasses, pendants, and earbuds in ways that users actually find valuable, it could reshape how people interact with technology. The shift from "pull" computing (you have to actively reach for your phone) to "push" computing (information comes to you) represents a fundamental change in interface design.

Tesla's Robotaxi Troubles: The Safety Question

While Apple is preparing glossy hardware announcements, Tesla is dealing with a more serious problem. The company's robotaxi vehicles have crashed 14 times in 9 months, according to reports from vehicle safety databases.

That's a significant number. It suggests that Tesla's autonomous driving technology, despite all the hype and promises, still has serious reliability issues. These aren't theoretical safety concerns. These are actual crashes happening in real traffic with real consequences.

What makes this particularly notable is the timing. Tesla has been pushing hard on its robotaxi initiative, suggesting that fully autonomous vehicles are around the corner. But the crash data suggests the technology is still nowhere near ready for widespread deployment.

The crashes also raise questions about regulatory oversight. If robotaxis are crashing this frequently, what kind of regulatory approval process is allowing them on the road? Tesla has been operating in a somewhat regulatory gray zone, testing vehicles in ways that might not be permitted for other companies.

There's also the branding issue. Tesla CEO Elon Musk has been pushing the robotaxi narrative aggressively. He's suggested that Tesla will eventually transition away from consumer vehicles entirely and focus on robotaxis as a service. But if the vehicles can't drive safely now, that future is a long way off.

The robotaxi situation reflects a broader pattern in tech and automotive: companies pushing timelines and capabilities beyond what the technology currently supports. It's the classic "promise big, deliver later" strategy. But when the technology involves public safety, that strategy becomes ethically questionable.

Investors and consumers need accurate information about the state of autonomous driving technology. If companies are overselling their capabilities, they're not just being misleading. They could be encouraging people to use unsafe technology.

Tesla's recent move to stop using the term "Autopilot" in California is a subtle acknowledgment of these concerns. The term "Autopilot" implies a higher level of autonomy than the system actually provides. By dropping the term, Tesla is attempting to avoid misleading consumers and potentially managing liability.

But that's a branding change, not a technology change. The actual vehicles are the same. They still crash occasionally. The issue isn't the name. It's the capability gap.

Samsung's Privacy Display: A Useful S26 Feature

Samsung has been working on a feature called a "privacy display" for its Galaxy S series phones. New reports suggest the Galaxy S26 will finally include this technology in a meaningful way.

A privacy display uses technology to prevent side-viewing. When you're looking at your phone screen, you can see everything. But if someone next to you tries to glance at your screen, they see a blank or filtered image. The technology essentially makes the screen visible only from the front.

This is actually a useful feature that addresses a real problem. If you're in public using mobile banking, entering passwords, or looking at sensitive information, you don't want people around you seeing your screen. A privacy display solves that problem.

What's interesting is that Samsung is advertising this feature through a clever ad campaign that confirms earlier rumors. Instead of a traditional product launch, the company is using advertising to hint at upcoming features. This generates buzz and gets people talking about the product before it's officially announced.

The privacy display feature is relatively simple technically, but it addresses a real user need. It's the kind of practical feature that might not get headlines but will genuinely make the product better for many users.

It also reflects a broader trend in smartphone design: features that address privacy and security concerns. As consumers become more aware of privacy issues, phone makers are incorporating features that give users more control over their data and their digital interactions.

DJI's Robovac Security Disaster

One of the most shocking stories from the tech world in early 2025 is the massive security flaw discovered in DJI's Romo robovac. The vulnerability was so severe that one security researcher was able to remotely access thousands of them.

The flaw appears to have been a simple authentication failure. The robovac's connectivity didn't properly verify user identity or device ownership. This meant that anyone with basic technical knowledge could essentially hijack any Romo device and control it remotely.

A security researcher demonstrated this by remotely accessing thousands of devices. He could control their movement, access their sensors, and potentially disable them. The security implications are significant. Imagine thousands of robots in homes and businesses that can be controlled by anyone who knows about the vulnerability.

DJI has since patched the vulnerability, but the incident raises serious questions about Io T security more broadly. Smart devices are being deployed at scale without adequate security testing. Companies are prioritizing features and speed to market over security fundamentals.

This is a recurring pattern in the Io T space. Companies rush devices to market, skip security testing or use inadequate security implementations, and then fix problems when researchers discover them. The devices are already deployed by that point, and millions of users are exposed to the vulnerability.

For consumers, this is troubling. You buy a smart device because it offers useful features. But you have no real way to verify that it's secure. You have to trust the manufacturer's security practices, even though many manufacturers clearly don't prioritize security adequately.

The DJI incident is a good reminder of this risk. A security flaw that should have been obvious turned out to be deployed in thousands of devices. That's a massive failure of security engineering.

The Bigger Picture: Tech Regulation and Corporate Power

These various stories from the tech world in early 2025 point to a common theme: the balance between corporate innovation, regulatory oversight, and consumer protection is fundamentally broken.

On one hand, you have FCC Commissioner Carr using regulatory threats to suppress speech and limit broadcast journalism. That's government overreach suppressing corporate and individual speech rights.

On the other hand, you have Meta planning to deploy facial recognition technology with barely any regulatory oversight. That's corporate power operating in regulatory gray zones without adequate safeguards.

You have Tesla deploying robotaxis that crash regularly, operating in legal gray zones while making claims that aren't fully supported by the technology.

You have DJI shipping robovacs with inadequate security, exposing thousands of users to hijacking risks.

Each story involves different actors and different problems. But collectively, they point to a system where:

- Regulatory agencies can use threats to suppress speech and control corporate behavior in ways that may violate free speech principles.

- Companies can deploy new technologies with minimal oversight, creating risks for consumers and society.

- Tech companies can oversell capabilities and underestimate risks.

- Security and privacy considerations are often afterthoughts rather than fundamental engineering principles.

Solving these problems requires better regulation, yes. But it also requires regulatory agencies that are focused on genuine public benefit rather than political goals. It requires companies that prioritize security and ethics over speed and features. And it requires consumers who are more aware of the risks and more willing to hold both companies and regulators accountable.

The Colbert situation is particularly important because it directly impacts public discourse. When regulatory threats suppress journalism and political coverage, that's a threat to democracy itself. The other stories involve important issues around privacy, safety, and consumer protection. But the FCC's actions against broadcasters strike at the heart of democratic communication.

The Role of Responsible Journalism in Tech Oversight

One of the key elements missing from this story is robust journalistic investigation and reporting. The Colbert situation was actually reported by The Verge and other outlets, which is how the public learned about it. Without that reporting, CBS would have simply killed the interview and nobody would have known why.

Journalism that investigates tech companies and regulatory agencies serves a vital function. It forces transparency and accountability. When the Colbert story broke, it generated public backlash against the FCC's approach. The chilling effect was partially undone by visibility.

But not all tech stories get this kind of attention. DJI's security flaw was discovered by a researcher and reported by tech outlets. If security researchers hadn't found it, it might still be exploited. The public would have no way to know their robovacs were compromised.

Meta's facial recognition plans are being developed with minimal public awareness or debate. Privacy organizations are pushing back, but without major media attention, the technology could ship widely before public concern forces action.

Journalism and public scrutiny are among the few mechanisms available to address these imbalances. That's why the Colbert situation is so significant. When the FCC threatens to suppress journalism, that's not just about one interview. It's about weakening the systems of accountability that society depends on.

Building Better Guardrails: What Should Change

If regulatory agencies like the FCC are going to have power over broadcast content, there need to be clear, objective standards for how that power is exercised. The equal time rule should be clarified so that broadcasters understand exactly what triggers obligations and what doesn't.

Instead of vague threats from individual commissioners, the FCC should issue clear guidance. If the equal time rule applies to late-night comedy interviews, say so explicitly. If it doesn't, say that too. Regulatory ambiguity is incompatible with a free press.

For tech companies, there need to be better security and privacy requirements. Devices shouldn't ship with critical security flaws. Companies shouldn't be able to deploy new technologies in regulatory gray zones without any oversight.

That doesn't necessarily mean heavy-handed regulation that stifles innovation. But it means basic standards. Security audits. Privacy impact assessments. Clear disclosure of capabilities and limitations.

For consumers, there needs to be better education about what's actually possible with current technology versus what companies are promising. Robotaxis that crash fourteen times in nine months aren't ready for widespread deployment, no matter what executives claim. Facial recognition technology with minimal privacy safeguards shouldn't be deployed in wearables until we've had serious policy discussions about its implications.

The fundamental challenge is that technology is moving faster than governance and regulatory structures can adapt. Companies exploit that gap, deploying technology without adequate safeguards. Regulators either lag behind or use power in ways that suppress speech and innovation rather than protect consumers.

Breaking that cycle requires better communication between tech companies, regulators, and the public. It requires transparency about what's being developed and why. It requires clear standards and consistent enforcement rather than selective threats.

Most of all, it requires recognizing that some technologies (like facial recognition in wearables) or some regulatory actions (like threatening broadcasters over vague rules) deserve serious democratic debate before they're deployed.

FAQ

What is the FCC's equal time rule?

The equal time rule is a Federal Communications Commission regulation that requires broadcasters to offer equal airtime to all political candidates if they give airtime to one candidate. Dating back to 1927 and codified in the Communications Act of 1934, the rule is designed to prevent broadcasters from monopolizing political speech. However, the rule has narrow exemptions for news coverage and certain other situations, making it subject to interpretation and dispute.

How did the equal time rule affect Stephen Colbert's interview?

FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr sent a letter to CBS hinting at potential equal time violations if the network aired an interview with James Talarico, a Texas politician running for Congress. Facing the threat of regulatory action, CBS decided to kill the interview rather than risk legal consequences. Colbert then made the suppressed interview public, turning the regulatory threat into a news story about censorship and free speech concerns.

Why is Carr's enforcement of the equal time rule controversial?

Carr's approach is controversial because he's enforcing the rule against entertainment programming like late-night comedy shows, which historically weren't subject to equal time obligations. His vague threats have created a chilling effect where networks self-censor political content out of fear rather than actual legal violations. This expands regulatory reach far beyond what the rule was originally designed to cover and suppresses journalism and political speech.

What is a chilling effect in First Amendment law?

A chilling effect occurs when people stop engaging in legal activity because they fear government consequences. The FCC's threats about equal time violations didn't require actual enforcement or legal action. The mere threat was enough to make CBS suppress the Colbert interview. This demonstrates how regulatory ambiguity can suppress speech without formal censorship or legal action.

What are the First Amendment implications of aggressive equal time enforcement?

Aggressive enforcement raises serious First Amendment questions about whether the government should be able to control broadcasters' editorial decisions through regulatory threats. While the FCC has authority over broadcast spectrum use, that authority must be balanced against free speech rights. Many constitutional scholars argue that aggressive equal time enforcement violates editorial freedom and may ultimately be constitutionally impermissible if challenged in court.

Why is facial recognition in smart glasses a privacy concern?

Facial recognition in wearable devices like smart glasses could enable passive surveillance and identification of people without their knowledge or consent. Unlike smartphone cameras that require deliberate action, smart glasses are worn constantly and could silently catalog and identify everyone the wearer encounters. This raises profound questions about privacy rights, surveillance scope, and whether such technology should be deployed without explicit policy frameworks and consumer consent mechanisms.

What does Tesla's robotaxi crash record tell us about autonomous vehicle readiness?

Tesla's 14 crashes in 9 months suggests that autonomous driving technology is still unreliable and nowhere near ready for widespread deployment, despite aggressive marketing claims. This highlights a pattern where tech companies oversell capabilities and timelines, deploying technology that isn't fully mature while operating in regulatory gray zones that lack adequate oversight and safety standards for autonomous vehicles.

How should regulators approach emerging technologies like facial recognition and autonomous vehicles?

Effective regulation should require clear security standards, privacy impact assessments, and transparent disclosure of capabilities and limitations before deployment. Rather than deploying first and addressing problems later, technology companies should be required to demonstrate safety and security adequacy beforehand. This requires better communication between tech companies, regulators, and the public, with clear democratic debate about significant technologies before they're widely deployed.

This estimated timeline illustrates the progression of events related to the FCC's equal time rule controversy involving Stephen Colbert in early 2025. The timeline highlights the growing impact of regulatory decisions on broadcast content.

Bringing Automation to Your Tech Coverage: Consider Runable

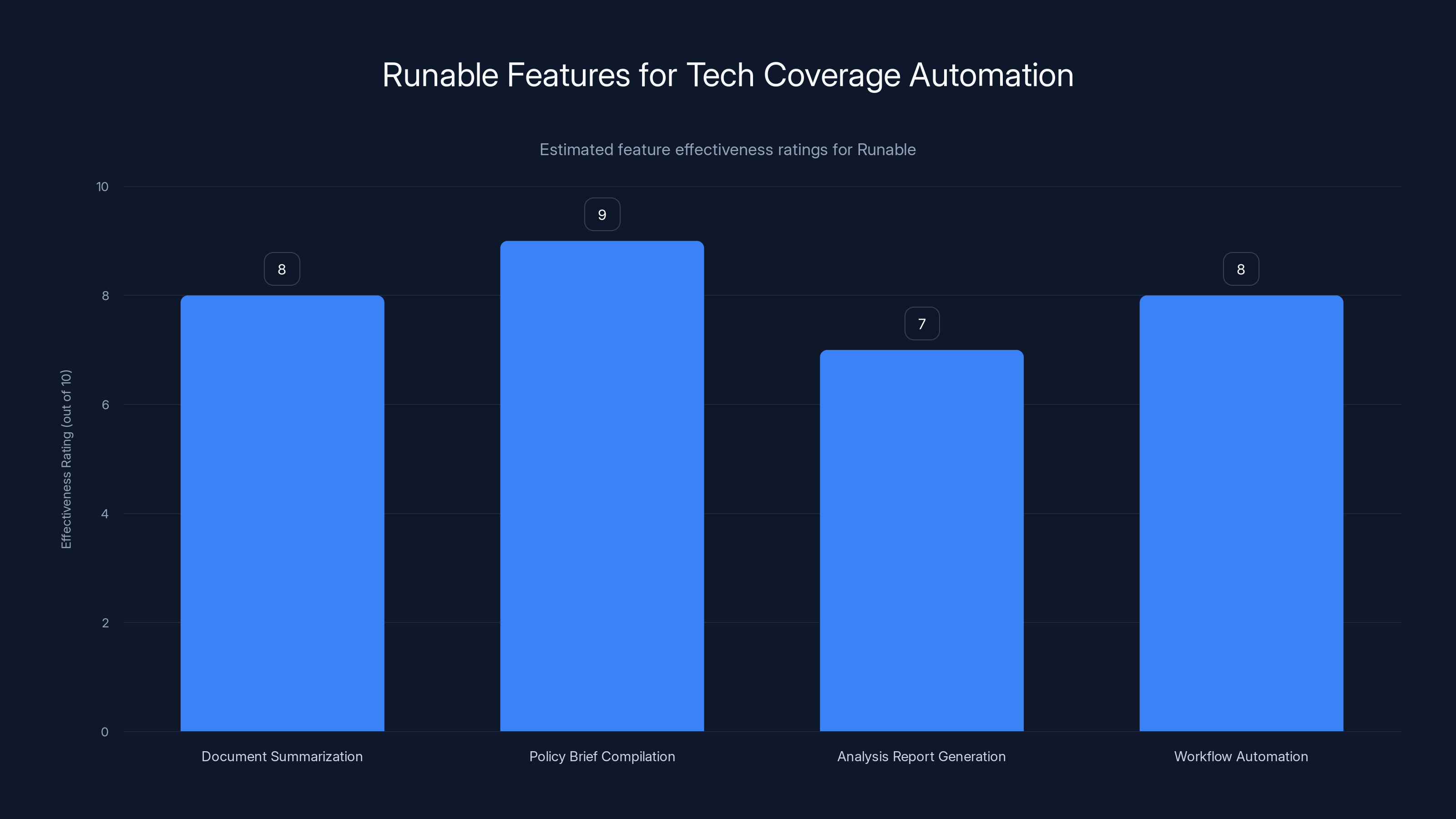

If you're following these complex tech policy stories and trying to synthesize information across multiple sources, Runable can help automate your research and reporting workflows. Create AI-powered documents that summarize regulatory actions, compile tech news into policy briefs, and generate analysis reports with Runable's document automation features. Starting at just $9/month, you can build intelligent workflows that pull together FCC actions, company announcements, and regulatory developments into coherent narratives—saving hours on manual research and synthesis.

Use Case: Automatically generate daily tech policy briefing documents from FCC statements, corporate announcements, and industry news feeds

Try Runable For Free

Runable's document automation features are highly effective, especially in compiling policy briefs and automating workflows. Estimated data.

Key Takeaways

- FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr's enforcement threats of the equal time rule created a chilling effect that convinced CBS to suppress Stephen Colbert's interview with political candidate James Talarico, without any formal legal action required.

- The equal time rule, originally designed in 1927 and codified in 1934, is being aggressively expanded by Carr to apply to entertainment programming in ways that historically weren't contemplated, raising serious First Amendment concerns.

- CBS's decision to kill the interview demonstrates how regulatory threats (even without enforcement) suppress speech more effectively than formal legal action, with downstream impacts on democratic discourse and voter information access.

- Meta's plans to deploy facial recognition in smart glasses, Tesla's robotaxi crash record, and DJI's critical security vulnerabilities reveal a broader pattern of tech companies deploying technology in regulatory gray zones without adequate safeguards.

- The fundamental imbalance requires better regulatory clarity, stronger security standards before deployment, and more transparent democratic debate about significant technologies rather than regulatory overreach or regulatory neglect.

Related Articles

- DOJ Antitrust Chief's Surprise Exit Weeks Before Live Nation Trial [2025]

- Prediction Markets Battle: MAGA vs Broligarch Politics Explained

- Zuckerberg's Testimony in Social Media Addiction Trial: What It Reveals [2025]

- Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Social Media Addiction: What Changed [2025]

- Zuckerberg Takes Stand in Social Media Trial: What's at Stake [2025]

- EU Investigation into Shein's Addictive Design & Illegal Products [2025]

![FCC Equal Time Rule Debate: The Colbert Censorship Story [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fcc-equal-time-rule-debate-the-colbert-censorship-story-2025/image-1-1771515467300.jpg)