The Battle Over Flow: How a Simple Name Sparked a Major Tech Lawsuit

There's something almost poetic about the irony here. Two tech giants are fighting over the word "Flow"—a term that literally means "to move smoothly." Except nothing about this legal dispute is smooth.

In early 2025, Autodesk, the company behind industry-standard 3D design software like AutoCAD and Maya, filed a trademark infringement lawsuit against Google in California federal court. The accusation? That Google's newly launched AI-powered video generator, also called "Flow," directly infringes on Autodesk's "Flow" branding and will confuse consumers.

On the surface, this seems like a straightforward trademark dispute. But dig deeper, and you'll find a case study in how the AI revolution is creating new collision points in tech. It's also a window into how companies brand their AI products, how trademark law adapts to emerging technologies, and what happens when two behemoths with overlapping product categories claim the same name.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what this lawsuit reveals about the competitive landscape of AI tools and creative technology.

TL; DR

- Autodesk's Complaint: Autodesk claims Google's "Flow" AI video generator infringes on its own "Flow" brand, which includes Flow Studio and other creative tools launched in 2022.

- Timeline of Events: Autodesk allegedly asked Google to stop using the name in 2024 after Google's May 2025 launch; Google offered to rebrand as "Google Flow" instead.

- Autodesk's Allegations: Autodesk claims confusion has already occurred on social media and in user communities, with people mistaking Google's product for Autodesk's Flow Studio.

- The Trademark Twist: Google reportedly filed for trademark protection in Tonga before applying for US trademark rights, raising questions about strategic sequencing.

- What's at Stake: A court injunction blocking Google from using "Flow," potential damages, and broader implications for how AI tools are branded and protected.

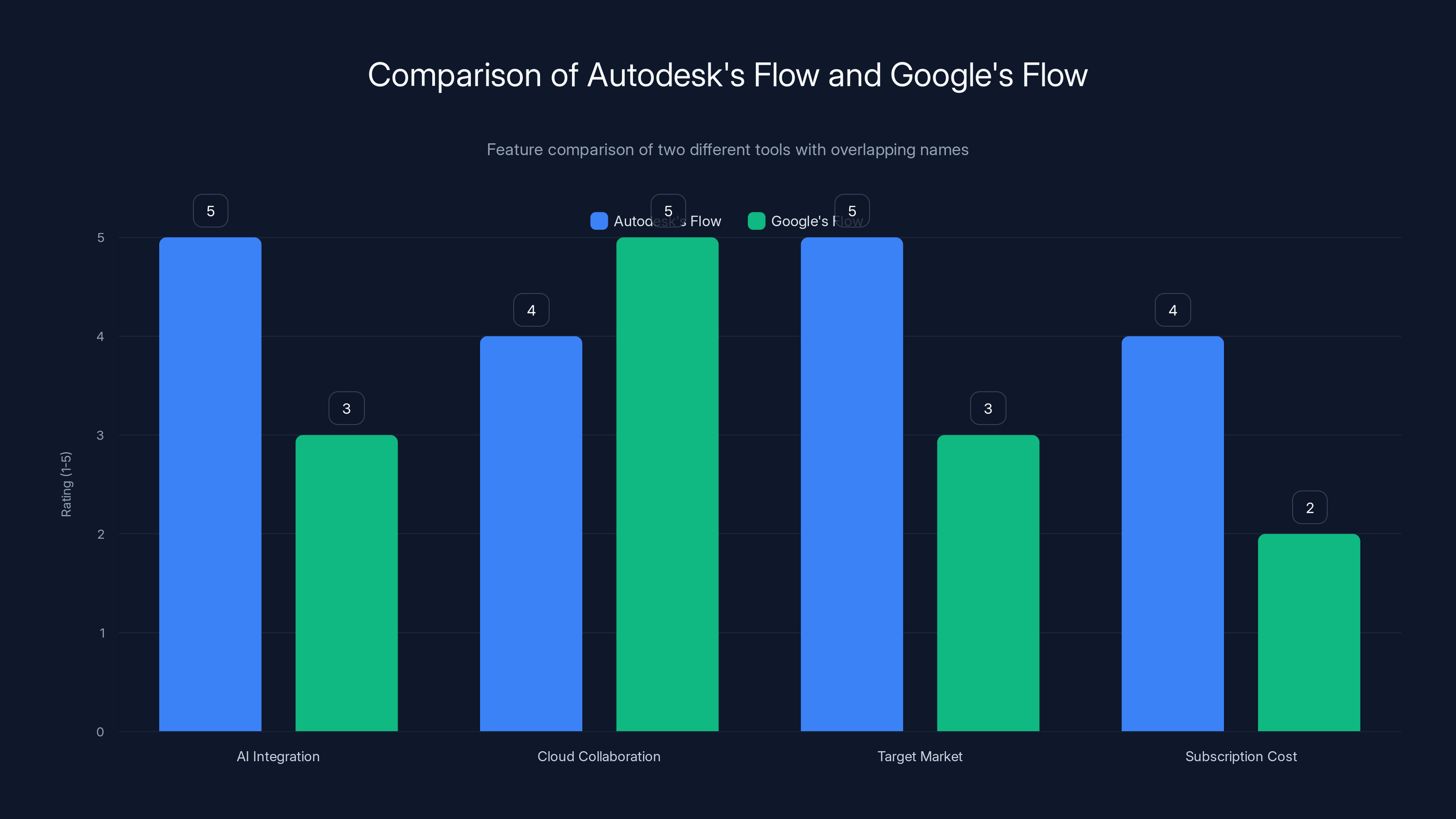

Autodesk's Flow is highly rated for AI integration and its professional target market, while Google's Flow excels in cloud collaboration. Estimated data based on typical feature strengths.

Understanding the Flow Products: Two Different Tools, One Overlapping Name

Before we dissect the legal arguments, it's crucial to understand what these products actually do. Autodesk's Flow and Google's Flow are not the same tools, but they operate in adjacent spaces that create genuine confusion potential.

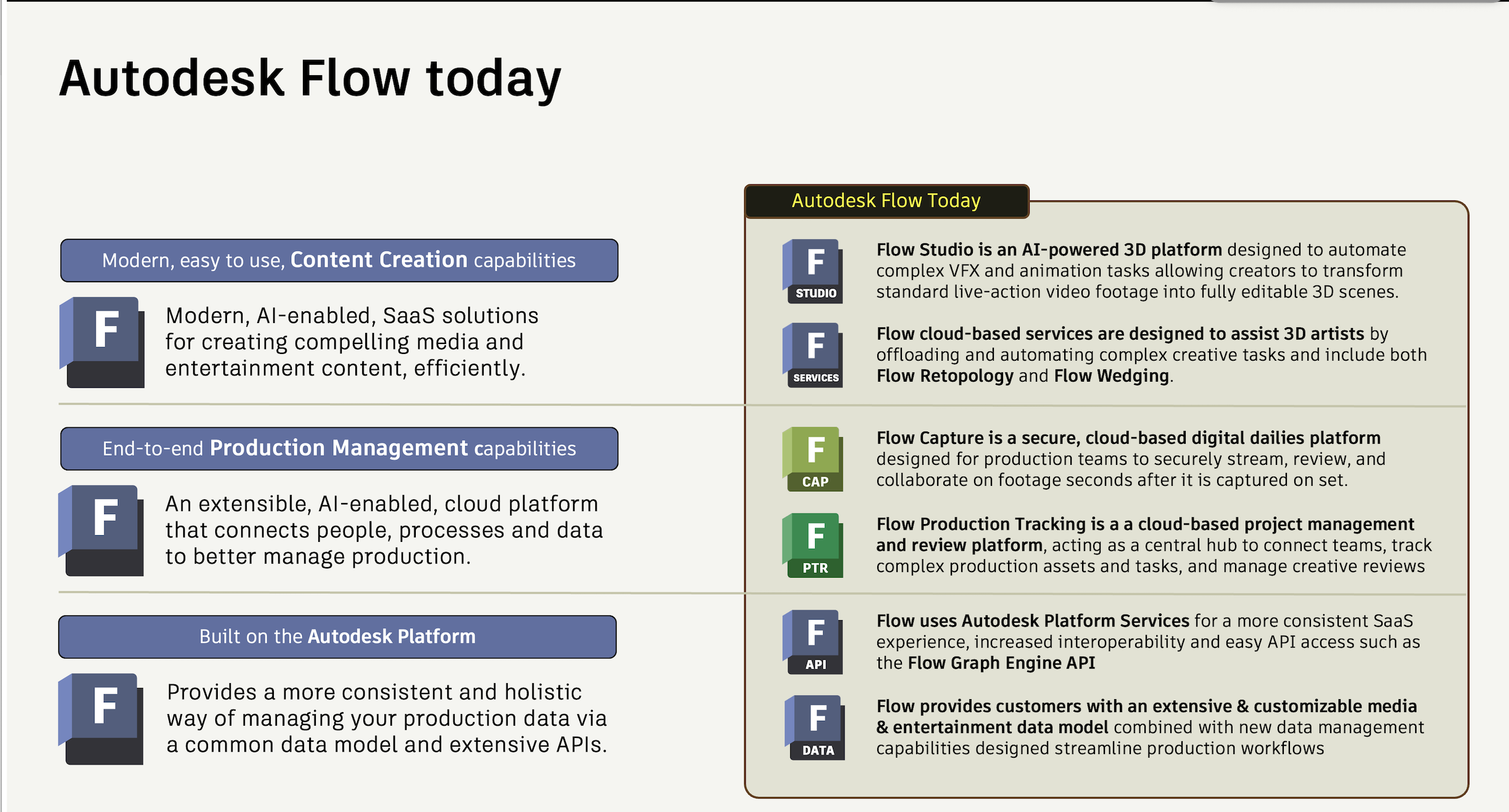

What Is Autodesk's Flow?

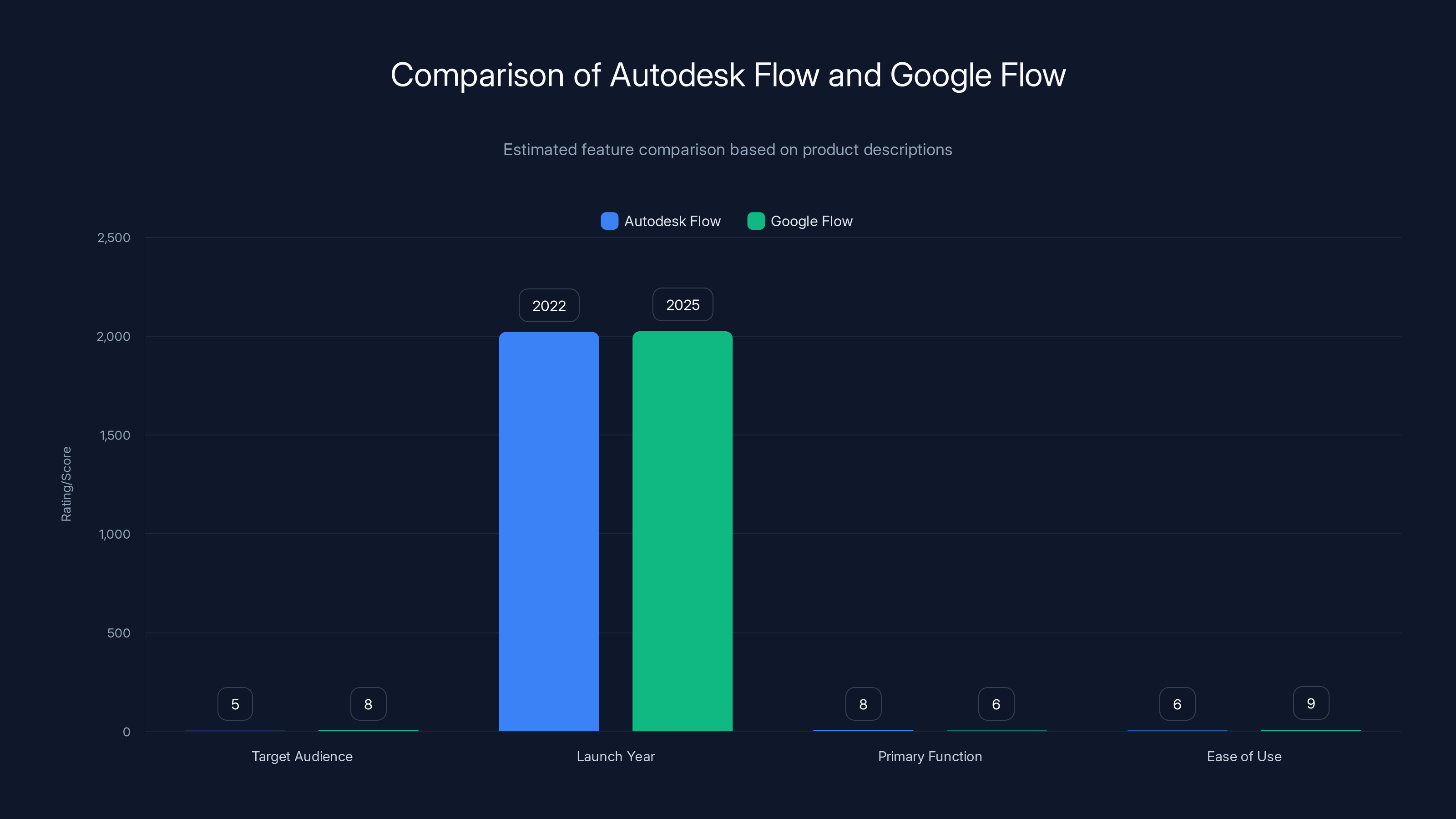

Autodesk introduced Flow in 2022 as a comprehensive cloud-based platform designed specifically for filmmakers, video editors, and visual content creators. Think of it as a suite of interconnected tools built for the modern creative workflow.

Flow Studio, the flagship product under the Flow umbrella, uses artificial intelligence to transform live-action footage into 3D scenes and environments. This is genuinely cutting-edge technology. Instead of hiring 3D artists to manually rebuild environments from video, creators can use AI to generate 3D models and scenes based on their footage. The time savings are substantial.

Beyond Flow Studio, Autodesk positioned Flow as a broader ecosystem for creators. The platform integrates with other Autodesk tools and offers cloud-based collaboration, real-time rendering capabilities, and AI-assisted creative workflows. Autodesk's target market here is professionals: the VFX studios, the production companies, the high-end creators who can justify subscription costs starting at several hundred dollars per month.

Autodesk's brand value lies in its reputation for professional-grade creative and engineering tools. When creative professionals hear "Autodesk," they think of AutoCAD, Maya, 3ds Max, Revit, and other software used in billion-dollar productions. The Flow brand was meant to extend that prestige into the AI-assisted creative realm.

What Is Google's Flow?

Google's Flow is something different, though superficially similar. Launched in May 2025, Google Flow is an AI video generator that creates short, AI-generated videos from text prompts. It's positioned as an accessible tool for creators of all skill levels, not just professionals.

The product sits within Google's broader generative AI ecosystem. It competes with tools like OpenAI's Sora, Runway ML, and Pika. These are consumer and prosumer-friendly AI video generators that lower the barrier to entry for video creation.

Google Flow generates videos from text descriptions. You describe a scene, and the AI creates the video. It's aimed at social media creators, content creators on platforms like YouTube and TikTok, and anyone who wants to experiment with AI-generated video without expensive software or professional training.

The core difference is access level. Autodesk's Flow is professional, premium, and priced accordingly. Google's Flow is mass-market, AI-first, and positioned as an accessible creative tool.

So here's the critical question: Would someone actually confuse them? Would a filmmaker looking for Autodesk's Flow Studio accidentally end up with Google's AI video generator? The answer determines the strength of Autodesk's case.

The Timeline: How We Got Here

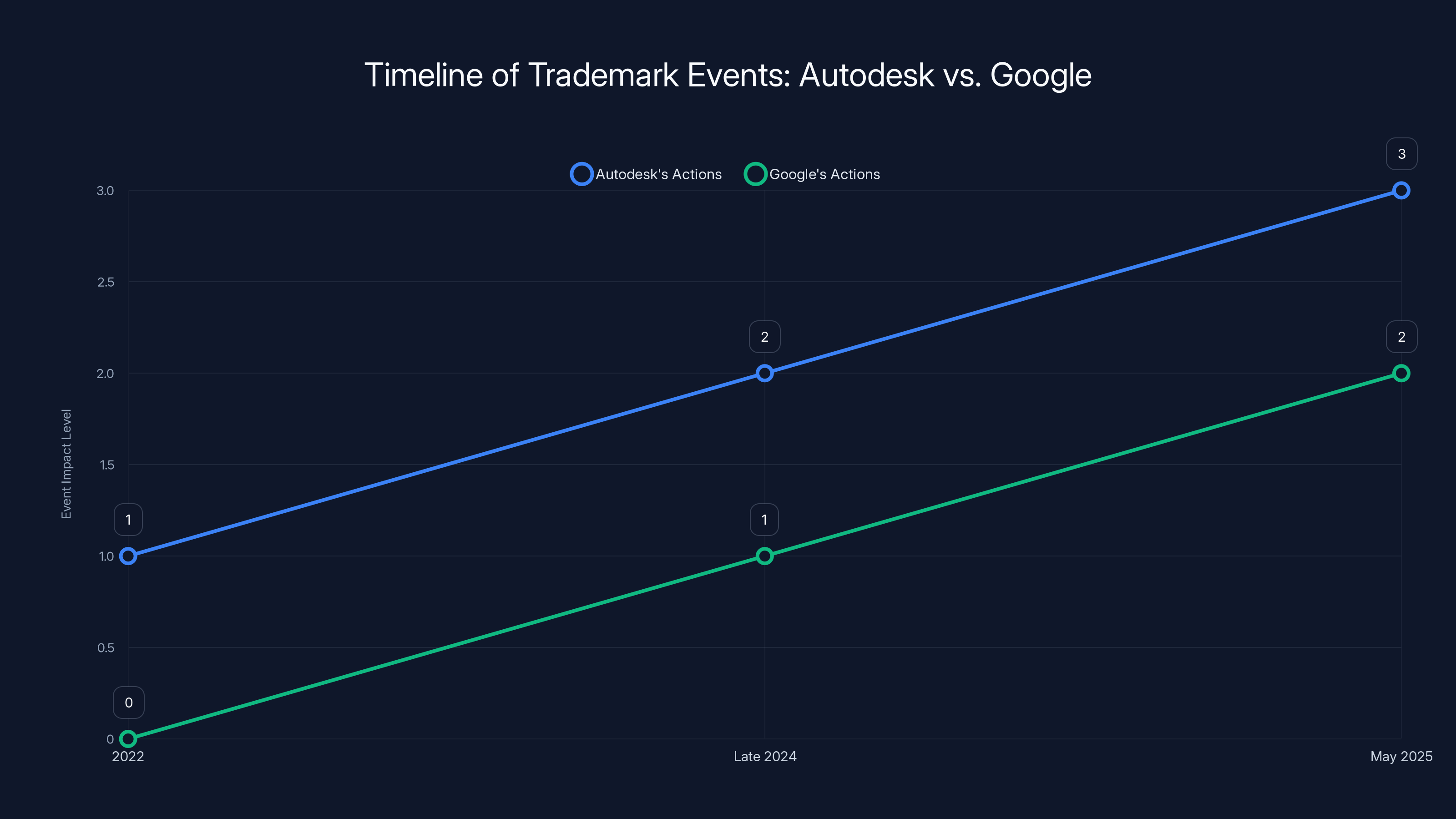

Understanding the sequence of events is crucial to understanding Autodesk's legal strategy. Timeline matters in trademark disputes because it establishes prior use and demonstrates whether the newer party had notice of existing trademarks.

2022: Autodesk Establishes the Flow Brand

Autodesk introduced Flow in 2022 as part of its broader pivot toward AI-assisted creative tools. This timing is important. Autodesk had already been investing in machine learning and AI capabilities across its product line, but Flow represented a dedicated, branded effort.

In 2022, Autodesk began using the "Flow" name consistently across marketing, product documentation, social media, and its corporate communications. They filed trademark applications in various jurisdictions to protect the name. The company's strategy was clear: establish Flow as a recognizable brand in the creative technology space.

Autodesk's prior use of the Flow brand is central to its legal argument. The company established consumer recognition, built marketing equity, and created consumer associations between "Flow" and Autodesk's creative tools.

May 2025: Google Launches Google Flow

Fast forward to May 2025. Google launched Google Flow, its AI-powered video generator. According to the lawsuit, Google did not consult with Autodesk about the name. Google simply released the product with the "Flow" branding.

The timeline here is important for understanding what Autodesk will argue: Google launched a product in an adjacent creative technology space, using a name that Autodesk had already established, without apparently checking whether that name was protected intellectual property.

Late 2024/Early 2025: The Cease-and-Desist Exchange

After Google's launch, Autodesk apparently reached out to Google to discuss the branding conflict. According to Autodesk's complaint, Autodesk requested that Google stop using the "Flow" name or at least modify it to clearly distinguish it from Autodesk's products.

Google's response was to offer a compromise: the company would market the product as "Google Flow" rather than just "Flow." This would add the Google brand name to provide distinction.

But Autodesk rejected this compromise. Why? Because according to the lawsuit, Autodesk alleged that Google "misrepresented" its true intentions. The complaint suggests that Google wasn't genuinely committed to using "Google Flow" exclusively and might eventually revert to just calling it "Flow."

This is a critical element of Autodesk's strategy. They're not just arguing that Google used the same name. They're arguing that Google's offer to add "Google" as a prefix was insincere and that Google would continue using "Flow" as the primary brand identifier.

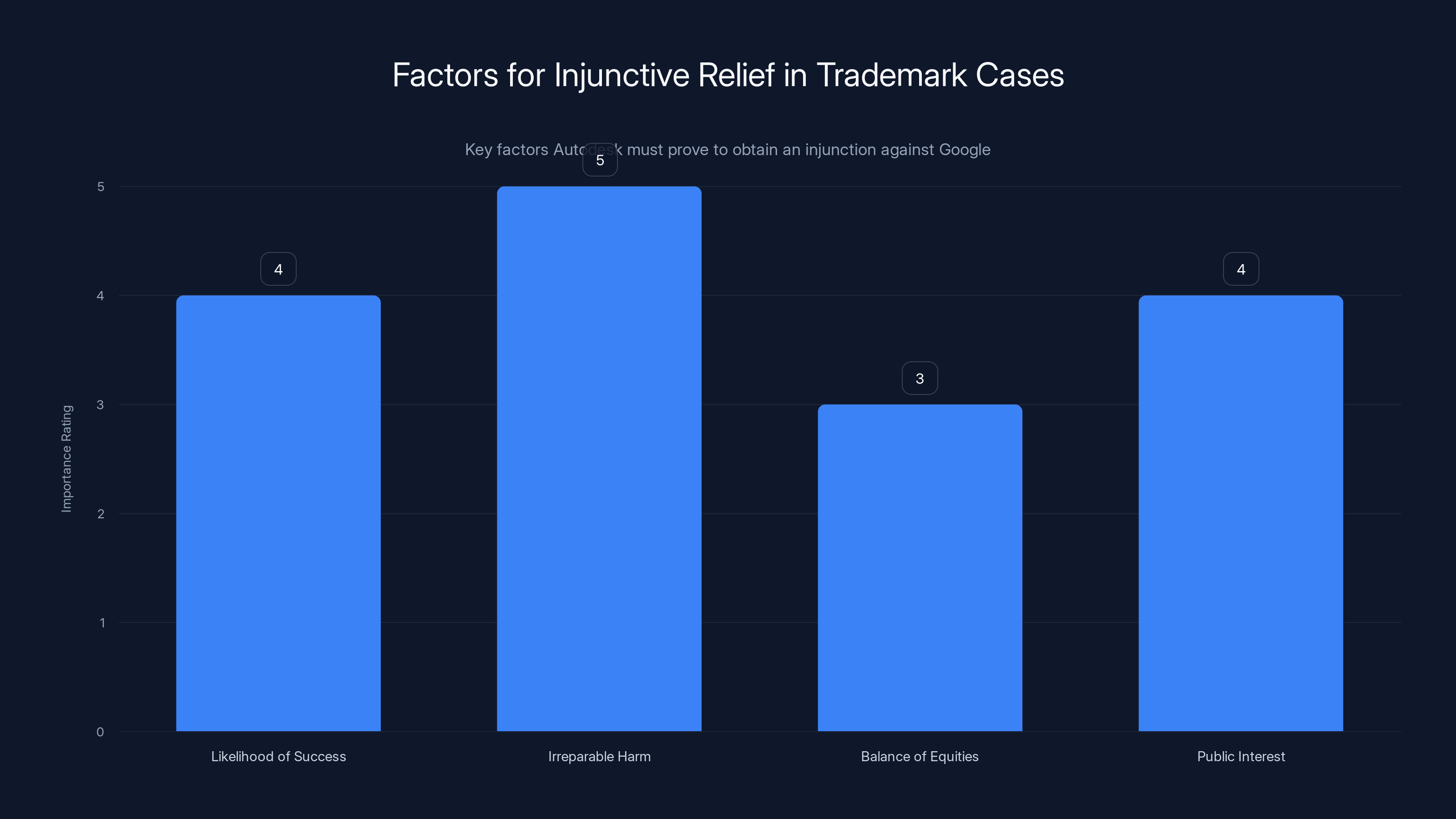

In trademark cases, proving 'Irreparable Harm' is crucial for obtaining injunctive relief, followed by 'Likelihood of Success'. Estimated data based on typical legal considerations.

The Tonga Trademark Filing: A Strategic Wrinkle

Here's where things get interesting from a legal strategy perspective. According to Autodesk's complaint, Google filed for trademark protection in the Kingdom of Tonga before filing in the United States.

Why Tonga? The complaint alleges that Tonga is a jurisdiction "where applications are not generally available to the public." By filing there first, Google may have created a priority date in a jurisdiction with less public transparency, then used that application to support its US trademark filing.

This is worth examining more carefully because it goes to intent and strategy.

How Trademark Priority Works

When you file a trademark application in one country, you can often use that filing date to establish priority in other countries through international treaties. The key treaty here is the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, which creates a six-month window during which you can file in other countries and maintain your original filing date.

Google's filing in Tonga, if it preceded the US filing, would establish an earlier priority date globally.

Why This Matters Legally

Autodesk's complaint treats the Tonga filing with a degree of suspicion. The allegation is essentially: Google knew about Autodesk's Flow trademark, filed in a jurisdiction with limited public records (Tonga), and then used that filing to support a US trademark application while claiming ignorance of Autodesk's prior brand.

This speaks to Google's intent. In trademark law, intent matters. If a company deliberately files in obscure jurisdictions to avoid detection of trademark conflicts, that can be presented as evidence of bad faith. Courts view bad faith filings negatively and may award enhanced damages.

Autodesk's lawyers are essentially making this argument: Google had options for how to file internationally. The choice to file in Tonga first—a jurisdiction with limited public transparency—suggests Google was being strategic about avoiding detection of the Autodesk conflict.

Google, for its part, hasn't publicly commented on its trademark filing strategy. But the company could argue that Tonga is part of standard trademark filing protocols and that the filing strategy was routine, not strategic.

The Consumer Confusion Argument: Does It Hold Up?

The legal foundation of Autodesk's lawsuit rests primarily on one concept: likelihood of consumer confusion. This is the standard test in trademark infringement cases. It's not enough to show that two companies use the same name. You must show that consumers are likely to be confused about which company makes which product.

The Evidence Autodesk Presents

Autodesk's complaint includes specific allegations of actual confusion. The company claims that people on social media, in magazines, and among Google Flow users have "mistakenly referred to Google's product as 'Flow Studio.'" This is evidence of actual confusion, which is powerful in court.

Consider what this means. Someone is using Google's AI video generator and calling it "Flow Studio," which is Autodesk's actual product name. That's confusion. That suggests the two brands are becoming conflated in consumers' minds.

Autodesk also points to the similarity of market context. Both Autodesk Flow and Google Flow operate in the creative technology space. Both involve AI and video. Both are marketed to creators. Both involve cloud-based tools. The overlap in market categories increases the likelihood of confusion.

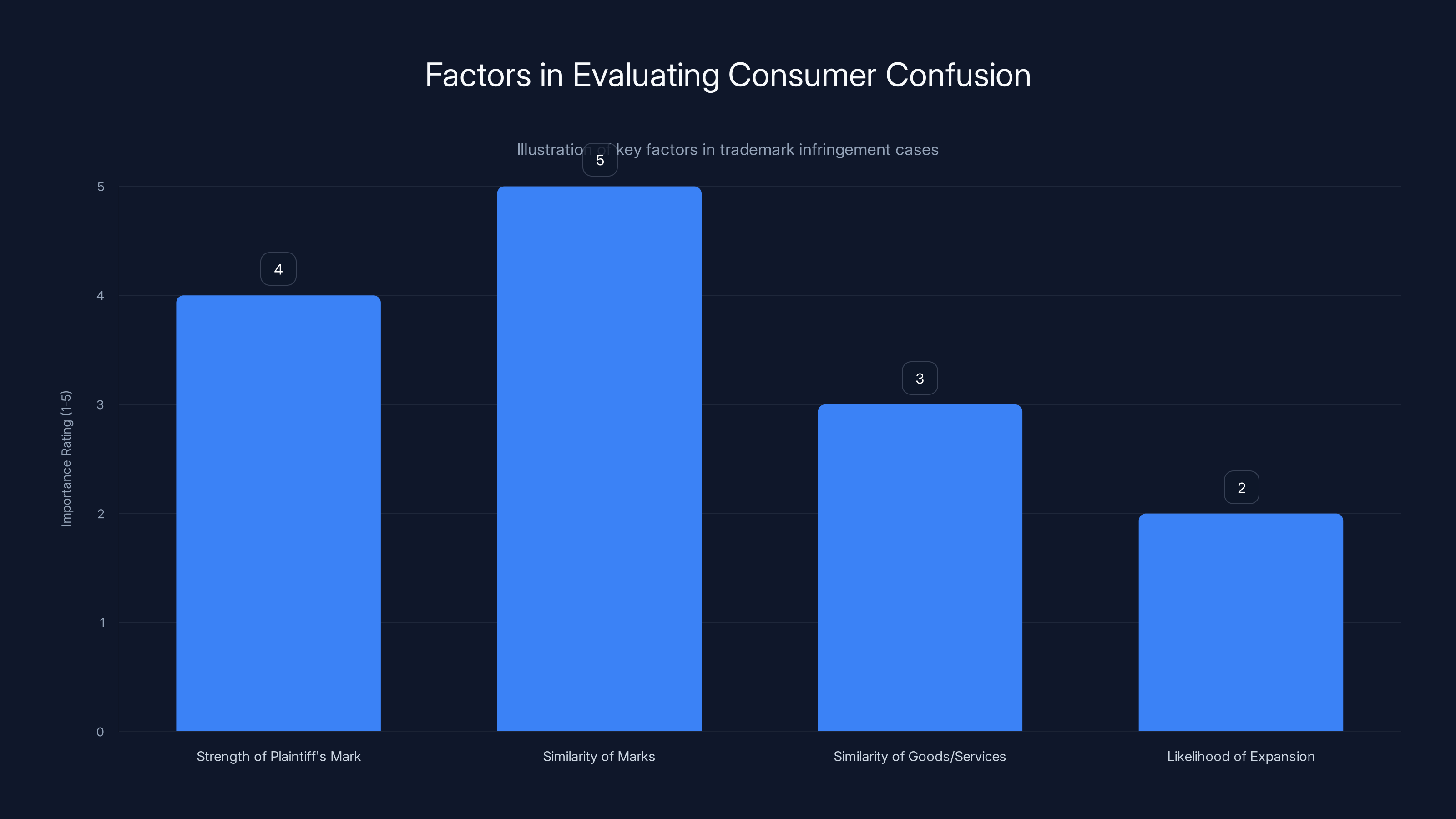

How Courts Evaluate Consumer Confusion

Courts typically use a multifactor test to evaluate likelihood of confusion. The exact factors vary slightly by jurisdiction, but the general framework includes:

-

Strength of the plaintiff's mark: How well-established is Autodesk's Flow brand? Is it distinctive? Has it acquired secondary meaning in consumers' minds?

-

Similarity of the marks: How similar are "Flow" and "Google Flow"? This might seem obvious (they're very similar), but adding "Google" as a prefix does provide some distinction.

-

Similarity of goods/services: How similar are the products? Professional 3D conversion vs. consumer AI video generation is different, but they overlap.

-

Likelihood of expansion: Would either company likely expand into the other's market? Possibly. Google enters new markets constantly. Autodesk could develop consumer-facing AI video tools.

-

Actual confusion: Has actual confusion occurred? Autodesk alleges yes, with specific examples.

-

Marketing channels and audiences: Do they reach similar customers? Partially. Both target creators, though at different levels.

-

Intent of the defendant: Did Google deliberately copy Autodesk's brand? The Tonga filing could suggest yes.

The Counterargument: Why Confusion Is Unlikely

Google's defense will likely argue that confusion is minimal because:

- The products serve different market segments (professional vs. consumer)

- The price points are vastly different

- The functionalities are distinct (3D conversion vs. text-to-video generation)

- Google's brand is so strong that "Google Flow" clearly signals Google's product

- Professional customers doing enterprise creative work are unlikely to confuse professional 3D conversion software with a consumer AI video tool

Google might also argue that the small amount of alleged actual confusion is trivial in a massive user base. If millions use Google Flow and only a handful called it "Flow Studio," that's not evidence of widespread confusion.

The Broader Context: AI Tools and Brand Protection

This lawsuit doesn't exist in a vacuum. It reflects a broader trend in tech: as companies rush to launch AI products, trademark disputes are becoming more common.

Why AI Product Naming Is Tricky

When you're building traditional software, naming is important but relatively straightforward. A database tool is obviously different from an email client. Categories are clear.

But AI products blur categories. An AI tool can be simultaneously a writing assistant, an image generator, a coding helper, and a research tool. Products evolve rapidly. What starts as a text-to-image generator might add video generation next month.

Given this fluidity, trademark protection for AI products is legitimately complicated. If Google Flow eventually adds 3D scene generation, the market overlap with Autodesk's Flow becomes much more direct. Trademark law needs to account for this possibility.

Recent AI Trademark Disputes

Autodesk vs. Google is not the first trademark clash in the AI space:

OpenAI and generative AI naming: OpenAI has had to navigate trademark issues around product names like ChatGPT, GPT-4, and others. The "GPT" acronym (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) is generic enough that it can't be trademarked, but specific product names can be.

Adobe and Firefly: Adobe's Firefly generative AI tool launched into a landscape where other companies had used "Firefly" for various purposes. Adobe chose the name deliberately, with trademark clearance, but the broader lesson is that naming requires careful research.

Anthropic's Claude: Anthropic chose "Claude" as a personal name, which inherently has some trademark clarity challenges since personal names are harder to protect.

The Pattern Emerging

The pattern is clear: as AI products proliferate, companies are increasingly discovering that desired names are already claimed. Some resolve it through negotiation. Some accept portfolio names like "Google Flow" with the company prefix. Some litigate, like Autodesk is doing.

Autodesk's lawsuit might establish important precedent for how trademark law treats AI products in overlapping categories. The decision could influence how future AI product names are chosen and protected.

Autodesk Flow targets professional users with a focus on 3D conversion, while Google Flow is designed for general users with an emphasis on ease of use. (Estimated data)

Trademark Law Principles at Play

To understand where this case could go, we need to examine the trademark law doctrines that will likely determine the outcome.

Prior Use and Distinctiveness

Autodesk's strongest argument is prior use. The company used "Flow" for its creative tools before Google launched Google Flow. Autodesk also has trademark registrations protecting the name in various jurisdictions.

Autodesk will argue that its use is distinctive—the brand is recognizably associated with Autodesk's creative tools, not a generic descriptor for any product with flowing elements or properties.

Google might counter that "Flow" is somewhat generic when describing software tools. Many apps have "Flow" in their name: Flow State (productivity), Salesforce Flow (automation), MindMeister Flow (collaboration). If "Flow" is understood as a descriptive term for smooth functionality, it's harder to protect.

But here's where Autodesk's defense strengthens: even if "Flow" has some descriptive element, Autodesk has acquired "secondary meaning," the legal term for when consumers associate a descriptive term with a specific brand.

Acquired Secondary Meaning

Secondary meaning means that the public has come to associate the term primarily with a specific source, not the descriptive meaning. When you hear "Flow" in the context of creative AI tools, does the average person think "Autodesk" or think of any product with smooth functionality?

Autodesk will argue secondary meaning. The company has marketed Flow consistently since 2022, invested in brand development, and created consumer associations between the name and Autodesk's products.

Google will argue that secondary meaning hasn't been established because Flow is one product among many, and consumers are more likely to remember "Autodesk" as the company than "Flow" as a distinctive brand.

This is genuinely uncertain legal territory. Brand recognition is fact-specific, and there's no simple threshold for secondary meaning.

Dilution Theory

Beyond infringement, Autodesk might also raise dilution arguments. Trademark dilution doctrine protects famous marks from having their distinctiveness eroded, even if there's no consumer confusion.

The argument would be: "Flow" has become associated with Autodesk's creative tools. Google's use of "Flow" for a different product dilutes that association and weakens Autodesk's brand.

Dilution claims are harder to win than infringement claims, but they provide an additional legal avenue for Autodesk.

Google would contest dilution by arguing that Flow is not famous enough to qualify for dilution protection and that using the name with the Google prefix minimizes any dilution effect.

Google's Likely Defense Strategy

Google hasn't officially responded to the lawsuit, but we can anticipate the company's likely legal strategy based on standard trademark defense arguments.

Non-Infringement: Different Goods

Google's primary defense will likely be that the products are not sufficiently similar to cause trademark confusion. Professional 3D conversion software and consumer AI video generation are different enough that consumers wouldn't confuse them.

Google will cite the different price points, different user expertise levels, and different functionalities. Professional VFX studios buying Autodesk's Flow Studio are not the same consumers as people using Google's free or low-cost AI video tool.

Descriptive Use Defense

Google might argue that "Flow" is descriptive of how their AI video generator functions. It creates smooth, flowing videos. The term is descriptive, not distinctive, and therefore not worthy of strong trademark protection.

But this argument is tricky. Courts generally require that descriptive terms be unavoidably necessary to describe the product. In this case, Google could use dozens of other names for its tool, so "Flow" isn't unavoidably descriptive.

Good Faith Use

Google might argue that it independently developed the Flow name without knowledge of Autodesk's trademark, and that upon learning of the conflict, it offered a reasonable compromise ("Google Flow").

This argument could undermine Autodesk's claims of willful infringement. If Google's use was good faith and unintentional, damages would be lower even if infringement is found.

However, the Tonga trademark filing might complicate this argument. If evidence emerges that Google was aware of Autodesk's trademark before filing the Tonga application, the good faith defense becomes much weaker.

The "Google" Prefix Defense

Google's strongest defense might simply be that adding "Google" as a prefix creates sufficient distinction. The products are marketed as "Google Flow," not just "Flow." This provides clarity about the source and reduces confusion likelihood.

Google will argue that the USPTO and trademark law generally allow similar marks to coexist in the same field if they're sufficiently distinguished by context, source, and customer sophistication.

What the Lawsuit Requests: Potential Outcomes

Autodesk is asking the California court for specific remedies. Understanding what Autodesk wants reveals what outcome it considers acceptable.

Injunctive Relief: The Primary Ask

Autodesk's primary request is injunctive relief—a court order preventing Google from using "Flow" as a trademark. This would force Google to rebrand its product or use a legally distinct name.

Obtaining an injunction requires showing:

- Likelihood of success on the merits: The plaintiff's legal case is strong

- Irreparable harm: Without the injunction, harm will occur that money damages can't fix

- Balance of equities: The hardship to the defendant is outweighed by hardship to the plaintiff

- Public interest: The injunction serves the public interest

For Autodesk to get an injunction, the company must convince the court that Google's continued use of "Flow" will cause ongoing brand confusion and damage that can't be remedied by money. That's a plausible argument when you're talking about brand reputation and trademark distinctiveness.

Google would argue that the balance of equities favors allowing Google to use the name. Google has invested substantial resources in the "Google Flow" product. Rebranding millions of users' apps, documentation, and marketing would be expensive and disruptive. Money damages would be sufficient remedy.

Monetary Damages: The Secondary Ask

Autodesk is also requesting "unspecified damages" related to the alleged trademark infringement. Damages in trademark cases typically fall into several categories:

Lost profits: Money Autodesk lost because consumers confused Google Flow with Autodesk Flow. This would be hard to calculate because Autodesk's Flow and Google's Flow serve different markets.

Unjust enrichment: Money Google earned by trading on Autodesk's brand reputation. This is complex to calculate but potentially significant if Autodesk can show that brand confusion drove user adoption of Google Flow.

Profits from infringement: If found deliberately infringing, courts can award Google's profits from the infringing product. Given Google's size and the small portion of revenue attributable to Flow, this could be substantial.

Statutory damages: Trademark law allows statutory damages up to $2 million per infringement for willful violations. If Autodesk can show Google knowingly infringed (the Tonga filing helps here), this could apply.

Attorney fees: If infringement is found to be willful, the court can award Autodesk's attorney fees, which in a complex case could be hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Counterclaim Risk: What Google Might Ask For

Google hasn't filed a counterclaim yet, but the company might argue that Autodesk's lawsuit is frivolous and seek attorney fees. If a defendant wins a trademark case, they can sometimes recover attorney fees from the plaintiff.

Google could also try to invalidate Autodesk's trademark registrations by challenging whether the marks are valid, distinctive, or properly maintained. This would be a longer-term strategy that could affect Autodesk's ability to protect Flow in the future.

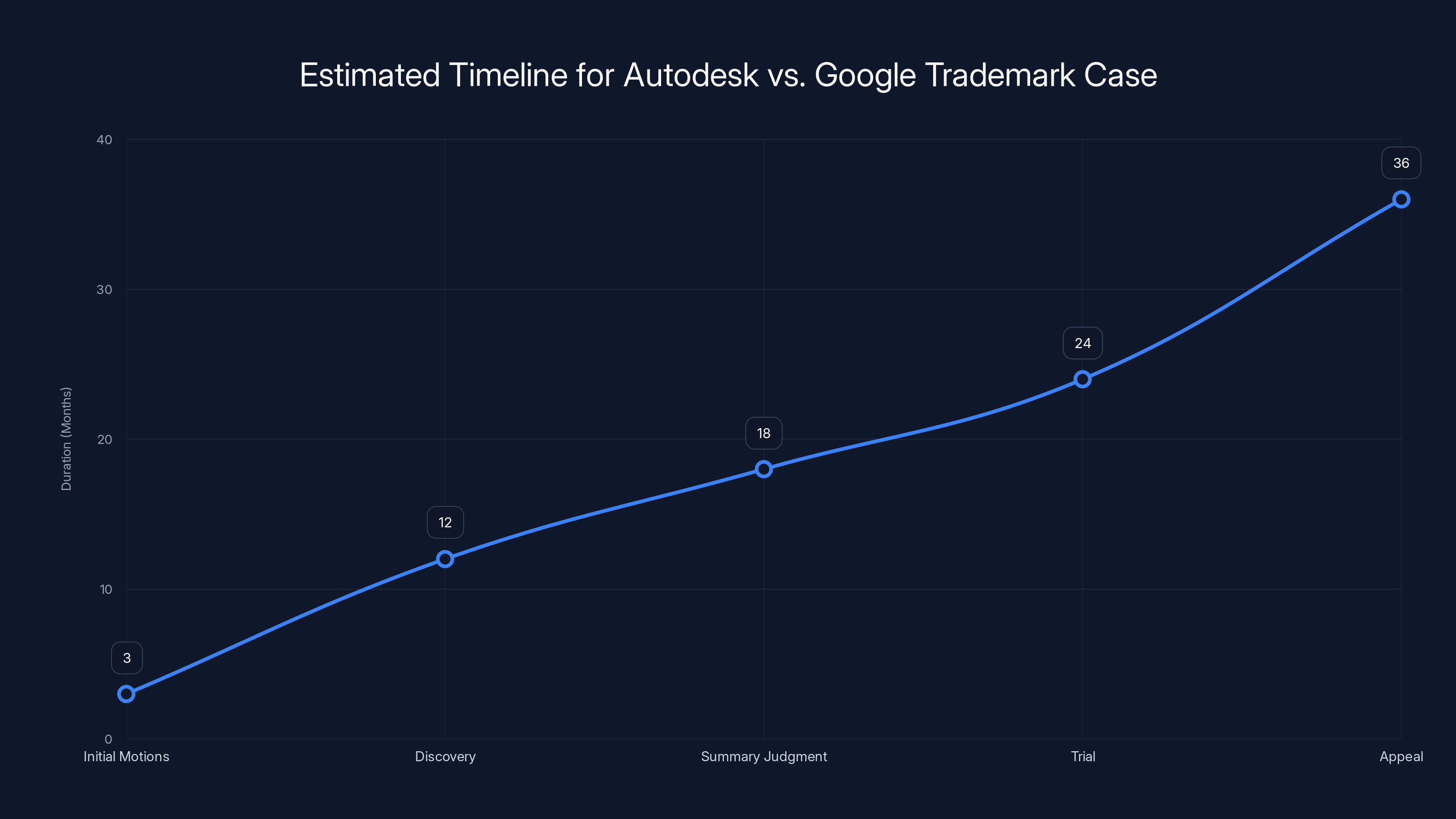

The Autodesk vs. Google trademark case is projected to follow a typical litigation timeline, potentially lasting 2-3 years if it proceeds through all phases without settlement. Estimated data based on typical case durations.

Market Impact and Competitive Implications

Beyond the legal question, this lawsuit has real business implications for both companies and the broader AI product market.

For Autodesk

Autodesk is fighting to protect the Flow brand it invested in establishing. Loss here would mean that Autodesk's trademark in "Flow" is potentially weakened or unenforceable. Other companies could then use Flow for their products.

Win or lose, the lawsuit sends a message to the market: Autodesk takes its intellectual property seriously and will defend its brands.

Autodesk also benefits from having a clear narrative in the marketplace. This lawsuit positions Autodesk as the original, innovative creator of Flow as a branded product category, with Google as the copycat.

But there are costs. Litigation is expensive, time-consuming, and creates negative publicity. Autodesk would prefer to be known for innovation, not lawsuit-filing.

For Google

Google has powerful advantages in any trademark dispute. The company's brand is vastly larger than Autodesk's in the consumer space. Adding "Google" as a prefix provides distinction.

But being sued by a major software company over a product name creates reputational friction, especially given ongoing antitrust scrutiny of Google. The lawsuit reinforces narratives about Google not respecting other companies' intellectual property rights.

Google also has to consider the cost of rebranding Google Flow if they lose. The product launched in May 2025, so there's still relatively limited brand investment, but changing the name would require updating apps, documentation, marketing, user-facing content, etc.

For the Broader AI Product Landscape

This lawsuit will influence how other companies name AI products. If Autodesk wins, companies will need to invest more in trademark clearance before launching AI products. If Google wins, companies might become more aggressive about reusing generic-sounding names.

Either way, the case creates uncertainty that could slow AI product launches as companies verify trademark availability.

Historical Precedents in Trademark Law

How might courts decide this? Looking at similar cases provides guidance.

Apple vs. Other Apples

Apple Inc. spent years fighting smaller companies using "Apple" in product names. Some cases Apple won, others it lost. The courts generally held that consumers were sophisticated enough to distinguish between Apple (the computer company) and apple (the fruit or generic uses).

Key lesson: Strength of the plaintiff's brand matters, but so does distinctiveness and whether consumers are likely to be confused.

Polaroid vs. Polaroid

A famous case involved multiple companies using variations of "Polaroid." The courts held that trademark protection depends on how distinctive the term is and how likely confusion is, not just on similarity of names.

Key lesson: Similar names can coexist if they're sufficiently distinguished by context and source.

Oracle vs. Open Source Java Forks

More recently, Oracle fought companies using "Java" for products that weren't affiliated with Java. Courts held that Oracle had trademark rights in Java, but that open source use was partially protected as descriptive.

Key lesson: Trademark rights are not absolute and context matters.

Microsoft vs. Lindows

Microsoft sued Lindows (a Linux distribution) for trademark infringement, arguing Windows vs. Lindows was confusing. The court held that Lindows was not confusingly similar and was a descriptive term for a Linux window system.

Key lesson: Courts examine whether confusion is actually likely, not just whether names are similar.

The Role of Trademark Registration Status

One crucial factor in this case is whether Autodesk actually has registered trademarks for Flow and whether those registrations are in good standing.

Benefits of Trademark Registration

If Autodesk has federal trademark registrations (through the US Patent and Trademark Office), this provides powerful legal advantages:

- Presumption of validity: A registered mark is presumed valid, shifting burden to Google to challenge it

- Nationwide protection: Registration protects the mark throughout the US, not just where it's used

- Basis for injunction: Courts are more likely to grant injunctions for registered marks

- Statutory damages: Registered marks can justify statutory damages of up to $2 million for willful infringement

- Federal court jurisdiction: Disputes over registered marks fall under federal trademark law

Autodesk would want to emphasize that it has registered trademarks, because registration strengthens the company's position significantly.

Potential Registration Challenges

Google might challenge the validity of Autodesk's registrations. Google could argue that Flow is descriptive, not distinctive, and therefore shouldn't be protected as a trademark.

If Autodesk has been using Flow for several years without enforcement, Google might argue that Autodesk abandoned the mark (failure to maintain it). But this would be hard to prove given that Autodesk is actively using Flow in commerce.

The timeline highlights Autodesk's early establishment of the 'Flow' brand in 2022 and Google's subsequent launch of a similar product in 2025, which is central to the trademark dispute.

International Trademark Implications

Autodesk and Google are global companies operating in international markets. The trademark dispute may extend beyond the US.

EU and UK Trademark Law

Europe has its own trademark system through the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO). If Autodesk has registered Flow as an EU trademark, Google's use of Flow in EU markets could also be challenged there.

EU trademark law is generally similar to US law but with some differences. EU courts might reach different conclusions than US courts on the same facts.

Asia-Pacific Considerations

Autodesk and Google both operate heavily in Asia-Pacific markets. If Autodesk has filed for trademarks in China, Japan, South Korea, and Australia, the company could pursue enforcement across those jurisdictions separately.

This multi-jurisdictional approach could either force Google to settle or create a complex global dispute with multiple overlapping cases.

Madrid Protocol and Filing Strategy

Both companies likely use the Madrid Protocol, an international treaty that allows companies to file one trademark application with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and seek protection in multiple countries simultaneously.

The filing strategy and timing of international applications could be relevant to the case. If Autodesk filed internationally for Flow protection before Google's launch, that strengthens Autodesk's position globally.

The Settlement Possibility: What a Deal Might Look Like

While we don't know if settlement is likely, trademark disputes often resolve through negotiation. What might a settlement between Autodesk and Google look like?

Scenario 1: Rebranding

Google could agree to rebrand "Google Flow" to something else—perhaps "Google Synthesia" or "Google AIVideo" or something entirely different. This would be expensive for Google but would fully resolve Autodesk's concerns.

In exchange, Autodesk might agree to not pursue damages, only requesting attorney fees and rebranding costs.

Scenario 2: Coexistence Agreement

Autodesk and Google could sign a coexistence agreement allowing both companies to use "Flow" in their respective product names, but in clearly distinguished markets:

- Google uses "Google Flow" exclusively (not just "Flow")

- Autodesk retains sole use of "Flow" for professional 3D and creative tools

- Both companies agree not to expand into the other's market space

- Both agree not to license "Flow" to competitors

Coexistence agreements are common in trademark disputes. They allow both parties to retain their brands while avoiding litigation.

Scenario 3: Licensing Deal

Autodesk could license the Flow trademark to Google, with Google paying Autodesk royalties or a fixed fee for the right to use the name. This would be less common for trademark licensing but theoretically possible.

Scenario 4: Autodesk Wins Injunction

If the case goes to trial and Autodesk wins, Google would be forced to rebrand, likely with a 12-month transition period to change apps, documentation, and marketing.

Google might also owe Autodesk damages. The exact amount would depend on how much profit Google made from Google Flow and how much harm Autodesk suffered.

Scenario 5: Google Wins Dismissal

If the case is dismissed or Google wins at trial, Autodesk loses and Google retains the Flow name.

Autodesk would be ordered to pay Google's attorney fees if the court determined Autodesk's suit was frivolous. This would be a significant financial loss on top of losing the trademark dispute.

What This Means for Creators and End Users

Beyond the corporate and legal implications, this lawsuit affects creators and users of both products.

For Autodesk Users

Autodesk's aggressive protection of the Flow brand sends a signal that Autodesk takes brand value seriously. For users of Autodesk products, this might increase confidence that the brand is protected and distinctive.

But the lawsuit also creates some uncertainty. If Google wins, Autodesk's brand value in "Flow" is diminished. If Autodesk wins, prices for Google Flow users might increase due to rebranding costs being passed along.

For Google Users

If Google loses and has to rebrand, all existing users of Google Flow would need to learn the new product name. Apps would change. Bookmarks and saved workflows might break. Documentation would be updated.

This would be disruptive but survivable for users. Google products have been rebranded before, and users adapt.

For new potential users, a rebrand creates momentary confusion but doesn't fundamentally change the product's functionality or value.

For Creators Evaluating AI Video Tools

The lawsuit creates awareness that trademark disputes exist in the AI tools space. Creators might become more cautious about choosing tools from smaller or newer companies that could face trademark challenges.

Marketplace confidence in product names and brand stability is important for adoption. The lawsuit creates doubt about the stability of "Flow" as a brand name going forward.

The similarity of marks and the strength of the plaintiff's mark are critical in evaluating consumer confusion, with similarity of goods/services also playing a significant role.

Lessons for Product Naming in the AI Era

This dispute offers valuable lessons for companies launching AI products.

Lesson 1: Trademark Clearance Is Essential

Before launching any product with a specific name, conduct thorough trademark clearance. Search the USPTO database, international trademark databases, and common law usage.

Google apparently did not conduct this clearance, or failed to identify Autodesk's Flow trademark during clearance.

Autodesk, by contrast, presumably conducted trademark clearance before launching Flow, which is why it had available trademarks to protect.

Lesson 2: Generic vs. Distinctive Names

Choosing distinctive, non-descriptive names reduces litigation risk. "Flow" is somewhat descriptive of how software functions (smooth, flowing execution). More distinctive names might have been less subject to dispute.

Compare to names like "ChatGPT" (distinctive) vs. "AI Chat" (descriptive and generic).

Lesson 3: Company Prefixes Provide Protection

Adding the company name as a prefix ("Google Flow" vs. "Flow") provides legal and practical distinction. This is why Google offered this compromise and why legal counsel likely advised it.

Companies launching AI products should strongly consider using company-prefixed names if the base name is not fully distinctive.

Lesson 4: International Considerations

File trademark applications internationally if your product will be global. Don't rely on filing in one jurisdiction.

The strategic question of where to file first (Tonga vs. the US) can have legal implications and should be discussed with trademark counsel.

Lesson 5: Expect More Disputes

As the AI product space matures and companies launch numerous products simultaneously, trademark disputes will become more common. The industry should expect more lawsuits like Autodesk vs. Google.

This will likely lead to:

- More expensive trademark clearance processes

- More coexistence agreements

- More distinctly branded AI products (fewer generic names)

- Possible industry standards around AI product naming

Timeline and Expected Case Duration

Trademark litigation typically follows a predictable timeline. Here's what we might expect in the Autodesk vs. Google case.

Phase 1: Initial Motions (Months 1-3)

Google will likely file a motion to dismiss, arguing that the case lacks merit or that the court lacks jurisdiction. Autodesk will file a response. The court will decide whether the case proceeds.

Assuming the case survives this phase, expect to continue forward.

Phase 2: Discovery (Months 4-12)

Both parties will exchange evidence. Google will demand documents from Autodesk about the Flow brand and its development. Autodesk will demand documents from Google about its trademark filing strategy and the decision to use Flow.

Depositions will occur where key executives and employees are questioned under oath.

This is the most expensive and time-consuming phase. Discovery in complex trademark cases can cost $1-2 million per party.

Phase 3: Summary Judgment Motions (Months 12-18)

Either party can file a motion for summary judgment, asking the court to decide the case based on the law and undisputed facts, without going to trial.

If the court finds that reasonable people couldn't disagree about the facts, it might grant summary judgment to one party.

Phase 4: Trial (If Case Reaches This Stage) (Months 18-24+)

If summary judgment fails, the case goes to trial. A judge (not a jury, in most trademark cases) will hear arguments and evidence from both sides.

Trial could last anywhere from a few days to a week or more for a complex case.

Phase 5: Appeal (Months 24-36+)

The losing party will likely appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (which covers California).

Appeal can extend the total timeline by another 1-2 years.

Overall Timeline: Realistically, expect this case to take 2-3 years to reach resolution, assuming no settlement.

Strategic Advantages for Each Side

Let's assess the relative strengths each party brings to this dispute.

Autodesk's Advantages

Prior use: Autodesk used Flow before Google. This is powerful evidence of trademark rights.

Trademark registration: Assuming Autodesk has registered trademarks, this provides legal presumptions of validity.

Actual confusion evidence: Autodesk alleges actual confusion (people calling Google Flow "Flow Studio"). This is evidence of likelihood of confusion.

Brand investment: Autodesk invested substantially in establishing Flow as a brand. This shows secondary meaning.

Industry credibility: Autodesk is a well-established company with strong reputation. Courts tend to be sympathetic to established companies protecting their brands from new players.

Google's Advantages

Brand strength: Google's brand is so powerful and so different from Autodesk that confusion seems unlikely to many observers.

Product distinction: Google Flow (AI text-to-video) is functionally different from Autodesk Flow (3D conversion). This difference supports an argument against likelihood of confusion.

Market segment separation: Google targets consumers and small businesses; Autodesk targets professionals and enterprises. Different buyers reduce confusion likelihood.

Financial resources: Google can afford the best legal representation and can sustain litigation longer than most companies.

Potential counterclaims: Google could challenge Autodesk's trademarks or argue other legal theories in its defense.

The Role of Publicity and Reputation

Beyond the legal merits, this case will be fought in the court of public opinion.

Autodesk's Public Relations Strategy

Autodesk wants to be seen as the innovator protecting its brand from a larger competitor copying its name. The narrative is: "We invested in Flow, built it into a recognized brand, and now Google is using the same name to confuse consumers."

This narrative works if it's consistent with facts and if Google's conduct seems opportunistic.

Google's Public Relations Challenge

Google faces a trickier narrative challenge. The company is vastly larger and better-known than Autodesk. Suing a major corporation can make Google look like a bully, especially given ongoing antitrust scrutiny.

Google's narrative would likely emphasize:

- Independent development of Flow

- Offer to use "Google Flow" as a compromise

- Fundamental differences between the products

- Unfairness of preventing a company from using a common term

Media Coverage Impact

Media coverage of this lawsuit will influence both public perception and potentially judicial decisions. Tech journalists will scrutinize:

- Whether Google acted in bad faith

- Whether the Tonga filing was strategic

- Whether confusion is actually likely

- Whether Google's compromise offer was reasonable

Positive media coverage for either party could influence settlements and even judicial thinking.

Predictions and Likely Outcomes

Based on trademark law principles and precedent, what's the most likely outcome?

Most Likely: Settlement or Coexistence Agreement

Litigation is expensive and uncertain. Both parties likely want certainty.

Most probable settlement: Google agrees to always use "Google Flow" (never just "Flow") in marketing, products, and documentation. Autodesk agrees to not pursue damages beyond attorney fees and settlement costs.

This protects both parties and costs far less than litigation.

Second Most Likely: Google Wins Dismissal

If the case reaches trial, Google's defense that the products are functionally and market-wise distinct could prevail.

Courts often side with defendants in trademark cases where the products serve different markets and the defendant uses the company name as a prefix for distinction.

Third Most Likely: Partial Autodesk Victory

The court could order Google to always use "Google Flow" (not just "Flow") but reject Autodesk's request for substantial damages.

This compromise satisfies Autodesk's core concern (brand protection) without devastating Google.

Least Likely: Full Autodesk Victory with Injunction and Damages

Autodesk winning a full injunction forcing rebranding and substantial damages would be surprising given Google's brand strength and product distinctiveness.

But it's possible if evidence of intentional infringement (the Tonga filing) is very compelling and actual confusion is proven extensive.

What This Tells Us About Brand Protection in Tech

This lawsuit illuminates broader truths about how brands are protected in the tech industry.

Brand Protection Is Aggressive

Major tech companies aggressively protect their intellectual property. Autodesk's lawsuit demonstrates that even mid-sized companies (Autodesk is large but smaller than Google) will fight for their brands.

Expect more such lawsuits as the AI space matures.

Names Matter More Than Ever

With thousands of AI tools launching, clear, distinctive naming is crucial for market differentiation.

Companies are learning to invest in trademark clearance earlier in product development and to use company-prefixed names when available base names are contested.

The Power of Company-Prefixed Brands

Google's strategy of offering to use "Google Flow" reflects understanding that company-prefixed brands provide strong legal and practical distinction.

Expect more AI products to launch with company-prefixed names (Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot, OpenAI ChatGPT) rather than standalone names.

International Trademark Filing Is Essential

Both Autodesk and Google clearly understand international trademark strategy. Filing in multiple jurisdictions provides global protection and leverage in disputes.

Smaller companies that don't file internationally put themselves at disadvantage.

FAQ

What exactly is Autodesk claiming in its lawsuit against Google?

Autodesk claims that Google's use of the "Flow" name for its AI video generator infringes on Autodesk's trademark rights in "Flow." Autodesk argues that the name creates likelihood of consumer confusion between Google's product and Autodesk's Flow creative tools, which the company introduced in 2022. The company alleges that actual confusion has already occurred, with people on social media and elsewhere mistaking Google's product for Autodesk's Flow Studio.

When did Autodesk introduce Flow and what does it do?

Autodesk introduced Flow in 2022 as a cloud-based platform for filmmakers and creative professionals. Flow Studio, the flagship product under the Flow brand, uses artificial intelligence to transform live-action footage into 3D scenes and environments. This is targeted at professional users in VFX studios, production companies, and other high-end creative businesses.

What is Google Flow and how is it different from Autodesk's Flow?

Google Flow is an AI-powered video generator launched in May 2025 that creates videos from text prompts. It's designed for general users, small creators, and content makers on platforms like YouTube and TikTok. Unlike Autodesk's professional 3D conversion tool, Google Flow is a consumer-facing AI video generation product targeting accessibility and ease of use rather than professional-grade output.

What does "likelihood of consumer confusion" mean in trademark law?

Likelihood of consumer confusion is the legal standard for trademark infringement. It means there's a reasonable probability that consumers could be confused about which company makes a product or provides a service, based on similar trademarks. Courts evaluate this using multiple factors including mark similarity, product similarity, brand strength, and evidence of actual confusion that has occurred.

Why did Google file for the Flow trademark in Tonga before the United States?

According to Autodesk's complaint, Google filed for trademark protection in the Kingdom of Tonga before filing in the US. Autodesk alleges this was strategic, as Tonga is "a jurisdiction where applications are not generally available to the public." By filing there first, Google could establish a priority date in a less-transparent jurisdiction and then use that application to support a US filing. Autodesk suggests this indicates Google was aware of Autodesk's Flow trademark and trying to avoid detection.

What remedies is Autodesk seeking in the lawsuit?

Autodesk is requesting two main remedies: an injunction (court order) that would prevent Google from using the Flow trademark, and unspecified monetary damages related to alleged trademark infringement. The injunction would likely force Google to rebrand its product, while damages could include lost profits, unjust enrichment, statutory damages (up to $2 million for willful infringement), and attorney fees.

How long do trademark lawsuits typically take to resolve?

Trademark lawsuits usually take 2-3 years from filing to resolution, assuming they reach trial. The timeline includes initial motions (1-3 months), discovery (4-12 months), summary judgment phase (12-18 months), potential trial (18-24 months), and possible appeal (24-36 months). However, many cases settle earlier during discovery or before trial, shortening the timeline significantly.

Is trademark infringement likely in this case based on past legal precedents?

Based on trademark law precedents, the outcome is genuinely uncertain. Courts have ruled both ways on similar cases depending on whether they emphasize product similarity or market differentiation. Google's significant brand strength, the functional differences between the products, and the separation of target markets (professional vs. consumer) could support Google's position. However, Autodesk's prior use, trademark registrations, and evidence of actual confusion support Autodesk's position. Courts would likely examine all factors and reach a fact-specific decision.

What is trademark "secondary meaning" and why is it important in this case?

Secondary meaning is when consumers have come to associate a descriptive term or mark with a specific company's products, rather than with the generic meaning of the term. For example, "Flow" originally means smooth or continuous movement, but if consumers associate "Flow" primarily with Autodesk's products, it has acquired secondary meaning. If Autodesk can prove secondary meaning, the company's trademark receives stronger legal protection. This is important because generic terms receive less protection than distinctive marks.

Could both companies settle and agree to coexist using the Flow name?

Yes, coexistence agreements are common in trademark disputes. Autodesk and Google could agree that Google uses "Google Flow" exclusively while Autodesk uses "Flow" for its creative tools, with both parties agreeing not to expand into each other's core markets. This approach allows both companies to retain their brand names while avoiding ongoing litigation costs and uncertainty.

What does this lawsuit suggest about trademark disputes in the AI industry going forward?

This case suggests that trademark disputes will become more common as companies rapidly launch AI products with similar names. The case will likely influence how companies name AI products, conduct trademark clearance, and file international trademark applications. Expect more emphasis on company-prefixed names (like "Google Flow" rather than just "Flow"), more aggressive trademark clearance processes, and potentially more litigation or settlement agreements as companies compete for clear brand identity in the crowded AI tools market.

The Broader Implications for AI Product Strategy

The Autodesk vs. Google dispute is just one case, but it reflects a systematic challenge facing the AI industry: how to name products in a crowded marketplace while respecting intellectual property rights.

As the AI tools market matures, we'll likely see three trends emerge. First, companies will invest more heavily in trademark clearance before launch, adding weeks to product release timelines but avoiding litigation. Second, company-prefixed branding will become standard (Google Flow, Microsoft Copilot, Anthropic Claude) rather than single-word names (ChatGPT being a notable exception). Third, companies will increasingly use coexistence agreements or licensing arrangements when trademark conflicts arise, rather than pursuing costly litigation.

For Autodesk, winning this case would validate the company's brand investment and establish Flow as a protected trademark. For Google, the lawsuit is a distraction from what should be a focused effort on product development. For the broader industry, the case is a cautionary tale about the importance of thorough trademark research before launch.

We'll likely have clarity on the outcome within 18-24 months as the litigation progresses through discovery and potentially to summary judgment. Until then, both companies operate in legal uncertainty, and the creative tools market watches to understand what brand protection means in the era of rapid AI product launches.

Key Takeaways

- Autodesk established the Flow brand in 2022 for professional AI-powered creative tools; Google launched Google Flow as a consumer AI video generator in May 2025, sparking trademark infringement lawsuit.

- Trademark infringement requires proving likelihood of consumer confusion; Autodesk claims actual confusion has occurred with users mistaking Google's product for Autodesk's Flow Studio.

- Google's alleged strategic filing in Tonga before the US raises questions about bad faith and awareness of Autodesk's trademark rights, which could influence damages if infringement is proven.

- The case reflects broader trends in AI industry where rapid product launches create trademark collisions; more companies will invest in trademark clearance and use company-prefixed branding to avoid disputes.

- Settlement or coexistence agreement is most likely outcome; Google using "Google Flow" exclusively rather than just "Flow" could resolve core confusion concerns without full rebrand.

Related Articles

- Anthropic's India Expansion Trademark Battle: What It Means for Global AI [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Crisis: What the New Mexico Trial Reveals [2025]

- Why AI-Generated Super Bowl Ads Failed Spectacularly [2026]

- Digital Squatting: How Hackers Target Brand Domains [2025]

- Crypto.com's $70M AI.com Gambit: Why Domain Names Matter [2025]

- Top Domain Extensions in 2025: Market Data, Trends & Predictions [2025]

![Autodesk Sues Google Over Flow AI Trademark [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/autodesk-sues-google-over-flow-ai-trademark-2025/image-1-1770736063760.png)