Introduction: When Platforms Make Safety Promises They Can't Keep

Imagine a parent downloading Instagram for their teenager, trusting the safety disclaimers they read. Meta's public statements promise robust protections, age verification mechanisms, and dedicated teams monitoring for predatory behavior. Then imagine discovering that internally, executives knew something entirely different.

This disconnect between public assurances and internal reality sits at the heart of a consequential legal battle that began in early 2025. New Mexico's attorney general brought a case that transcends typical consumer protection lawsuits. It's not just about whether Meta's products are addictive, though that's part of it. It's fundamentally about corporate deception: whether one of the world's most influential technology companies deliberately misled the public about what it knew regarding child safety risks.

The trial represents a watershed moment for social media regulation in America. For years, tech platforms have operated with remarkable latitude, protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields them from liability for user-generated content. But this case takes a different angle. It alleges that Meta itself made false statements to consumers, engaged in deceptive marketing practices, and prioritized engagement metrics over safeguarding minors.

What makes this litigation particularly significant is the evidence being presented. The state's case rests partly on internal documents and testimony from former Meta employees who helped build the very systems now under scrutiny. These aren't abstract regulatory complaints. They're allegations backed by people who watched product decisions made in real time, who participated in strategy meetings, and who ultimately decided to come forward.

The implications extend far beyond New Mexico. Other states are watching closely. Parents are paying attention. Congress members monitoring tech regulation are taking notes. And Meta, despite its legal resources and experience defending against regulatory challenges, faces a scenario where internal communications become public testimony. In an age where technology companies control how billions of people communicate, the question of whether they can be held accountable for misleading claims about safety has become unavoidable.

This comprehensive guide walks you through what this trial reveals about platform accountability, child safety on social media, the gap between corporate statements and internal knowledge, and what might happen next in the battle between regulators and tech giants.

TL; DR

- The Core Allegation: Meta allegedly made false public safety claims while internal documents showed executives knew the reality was different

- The Evidence: Decoy accounts caught suspected child predators on Meta's platforms, resulting in three arrests, demonstrating real-world harm

- Internal Contradictions: Executives estimated 4 million underage accounts on Instagram despite public claims of age restrictions

- Broader Pattern: This trial parallels another major case in Los Angeles alleging Meta designed products for addictive engagement, harming youth mental health

- What's at Stake: The outcome could reshape how social media companies market their safety features and force changes to product design and monitoring practices

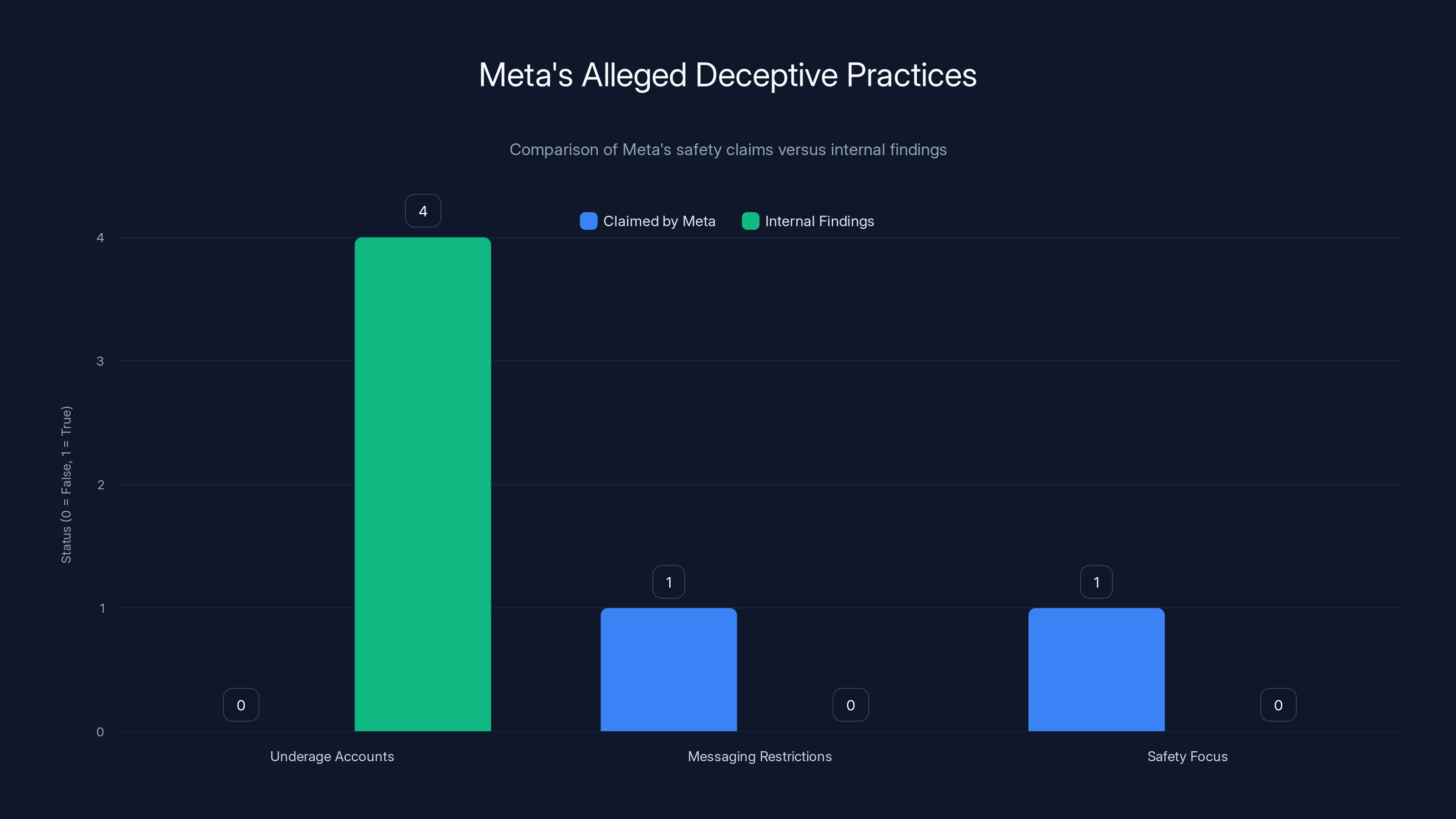

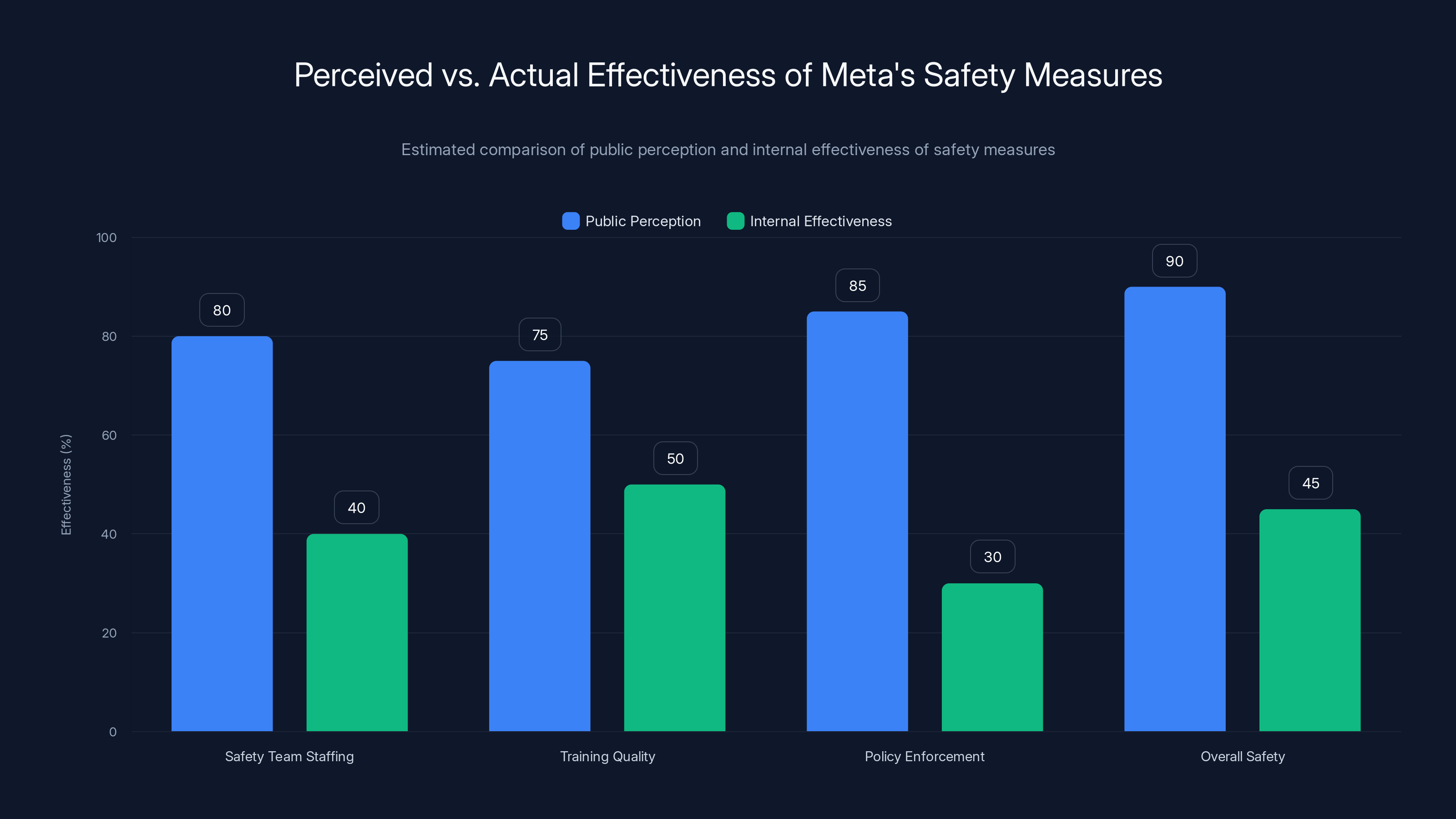

The chart highlights discrepancies between Meta's public safety claims and internal findings, such as the presence of 4 million underage accounts on Instagram, contradicting their policy of not allowing users under 13. (Estimated data)

The Lawsuit: State Attorney General Takes Aim at Meta's Deceptions

New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez didn't file this lawsuit on a whim. His office conducted an extensive investigation that included setting up undercover operations using decoy accounts. These weren't passive observations. They were deliberate attempts to see what would happen if suspected predators tried to exploit Meta's platforms.

The results were disturbing and, from the state's perspective, evidence of systematic failure. Three suspected child predators were arrested as a direct result of these sting operations. This isn't theoretical harm. These were actual individuals attempting to engage with minors on Facebook and Instagram. The fact that decoy accounts could attract such predators suggested that Meta's stated safety mechanisms either weren't functioning as advertised or weren't being enforced consistently.

The legal theory behind the case centers on consumer protection law. New Mexico's complaint alleges that Meta engaged in unfair or deceptive trade practices by making false representations about its products' safety features. The state argues that when Meta told the public about age restrictions, content moderation capabilities, and protective measures, it either knew these weren't working as described or deliberately misrepresented their effectiveness.

What makes this different from previous child safety lawsuits against tech companies is the direct focus on deceptive statements. Many prior cases centered on whether platforms should be liable for user-generated content or whether their algorithms promoted harmful material. This case argues something simpler but potentially more damaging: Meta lied about what it was doing to protect kids.

Torrez's team called this approach necessary because traditional product liability frameworks don't easily apply to social media platforms. You can't sue Facebook the way you'd sue a car manufacturer for brake failure. The legal immunity provided by Section 230 prevents that kind of claim. But you can sue for fraud, deceptive practices, and consumer protection violations. These are the tools the state deployed.

The decision to focus on deception rather than design flaws proved strategically important. It allowed the state to introduce extensive internal communications, executive emails, and corporate documents into evidence. It created a framework where what Meta said publicly could be directly compared to what Meta knew privately.

Meta claimed no underage accounts and effective messaging restrictions, but internal findings showed 4 million underage accounts and failed protections. Estimated data based on case details.

The Evidence: Internal Contradictions Between Claims and Reality

During opening statements, prosecutors used a powerful rhetorical device. They showed slides comparing two categories: "what Meta said" and "what Meta knew." This juxtaposition formed the visual framework for the entire case.

On the "what Meta said" side, prosecutors displayed statements from company executives, including CEO Mark Zuckerberg, making specific safety claims. Meta said kids under 13 weren't allowed on its platforms. Meta said users over 19 couldn't send direct messages to teenage accounts that didn't follow them. These weren't vague marketing claims. They were specific, testable assertions about how the platform functioned.

On the "what Meta knew" side, prosecutors presented internal emails and research findings. One particularly damaging piece of evidence was a 2018 communication from Zuckerberg to top executives. In this email, Zuckerberg wrote that he found it "untenable to subordinate free expression in the way that communicating the idea of 'Safety First' suggests." He added that "Keeping people safe is the counterbalance and not the main point."

That language is extraordinary. It suggests that the CEO himself viewed safety not as a primary objective but as a secondary consideration balanced against other business priorities. For the prosecution, this email becomes Exhibit A in proving that Meta's public safety-first messaging didn't reflect actual corporate priorities.

Then came the demographic data. Meta's own internal estimates showed that approximately 4 million accounts on Instagram belonged to children under 13 years old. This number directly contradicted the public statement that kids under 13 weren't allowed on the platform. The existence of these accounts wasn't surprising to anyone familiar with social media. Kids lie about their age when signing up. The platform's challenge is detecting and removing these accounts. But the internal estimate revealed something important: Meta knew how many underage accounts existed and the scale of the problem.

Prosecutors also introduced evidence about Meta's algorithmic recommendation systems. Internal research reportedly showed that Instagram's algorithm could be exploited to surface content related to self-harm, eating disorders, and sexual content to minors. This wasn't accidental. It was how the algorithm worked. It optimized for engagement, and certain categories of disturbing content generated measurable engagement from some user segments.

The state also presented testimony from former Meta employees who had direct knowledge of product decisions. Arturo Bejar, who worked as a Facebook engineering director and served as an Instagram consultant, had previously testified before Congress about the company's inadequate response to harmful content. His congressional testimony focused on Meta's awareness of harms and the company's reluctance to implement protective measures that would reduce engagement.

Another key witness was Jason Sattizahn, a former Meta researcher who also had testified before Congress. Sattizahn's work examined the correlation between social media use and mental health impacts, particularly for young users. His research reportedly contradicted public statements Meta had made about the safety of its platforms.

What made these witnesses particularly compelling was their insider status. They weren't external critics or activists. They were engineers and researchers who built the products and studied the harms. Their decision to testify aligned with their professional expertise and internal concerns they'd raised while employed at Meta.

The decoy account operations provided the evidence's most concrete element. The state set up accounts that mimicked minor users. These accounts were then used in controlled operations that attempted to see whether suspected predators could initiate contact or exploitation. When three suspected predators were arrested based on these operations, it demonstrated not merely that bad actors existed on the platform (which was undisputed) but that Meta's stated protective mechanisms either weren't detecting these predators or weren't preventing contact.

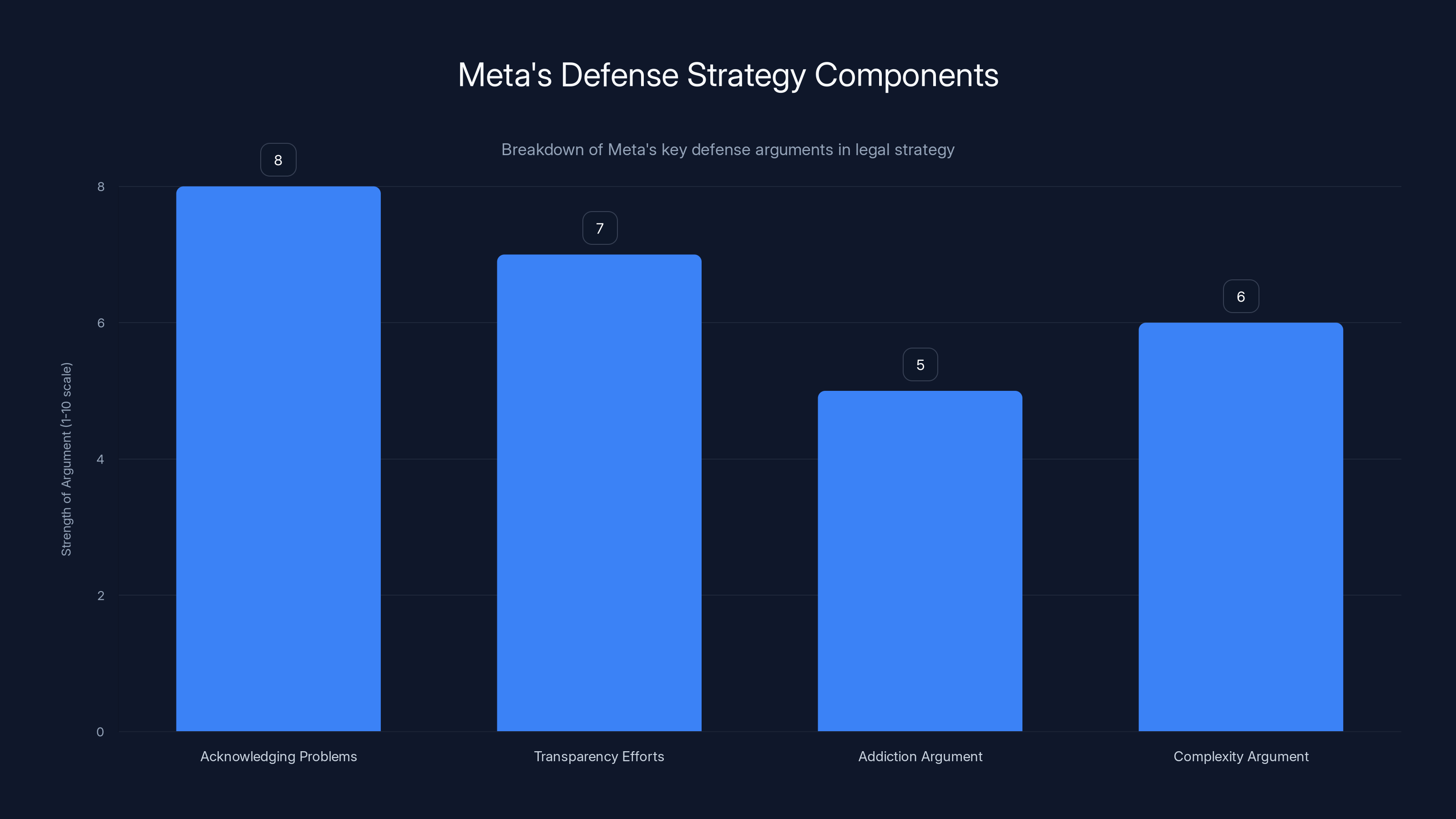

Meta's Defense Strategy: Acknowledging Problems While Denying Deception

Meta's legal team, led by attorney Huff, took a calculated defensive approach. Rather than denying that problems exist on Facebook and Instagram, they conceded that point. Yes, there's harmful content. Yes, there are predators. Yes, there are concerns about compulsive use patterns. These admissions removed Meta from the indefensible position of claiming the platforms are perfectly safe.

Instead, Meta's defense pivoted to two key arguments. First, the company argued that it's transparent about these challenges and actively works to mitigate them. Second, Meta challenged the notion that "social media addiction" is a legitimate concept, arguing it's scientifically unsupported and fundamentally different from substance abuse.

On the deception claim specifically, Meta's position was that the company didn't hide information about harms. Rather, Meta engaged in ongoing efforts to improve safety, and these efforts were public. Meta highlighted safety updates, feature introductions, and partnerships with safety organizations. The argument essentially claimed that acknowledging problems and working on them isn't deceptive, even if those problems remain partially unresolved.

Meta also invoked the complexity argument. Running a platform with billions of users involves constantly evolving challenges. Perfect enforcement of safety policies is mathematically impossible at scale. The company argued that reasonable people understand this, and therefore statements about safety policies shouldn't be interpreted as absolute guarantees.

Regarding the "addiction" framing, Meta's counsel made an explicit comparison. He stated that "Facebook is not like fentanyl" and that "no one is going to overdose on Facebook." This comparison attempted to distinguish between substance addiction (which creates measurable physical dependency and withdrawal symptoms) and problematic social media use patterns (which create psychological but not physiological symptoms).

Meta also emphasized the state's failure to partner with the company. The defense suggested that New Mexico's adversarial litigation approach undermined collaborative safety efforts. This argument appealed to the legal principle that companies working in good faith toward improvements shouldn't face punitive action simply because problems remain.

Crucially, Meta's defense prepared to challenge the credibility of former employees testifying for the state. The company had clearly briefed the jury in advance that former researcher Sattizahn would be a key witness and urged jurors to question his interpretations and conclusions before accepting them as fact.

Meta's strategy involved positioning itself not as a company hiding dangers but as a company managing genuinely difficult problems in real time. The difference between these framings is significant: one suggests deception and deliberate misconduct, while the other suggests honest struggle with challenging circumstances.

Meta's defense strategy focuses on acknowledging existing issues while emphasizing transparency and the complexity of managing a large platform. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Youth Mental Health and Platform Design

This New Mexico case didn't emerge in isolation. It's one of two major trials that began around the same time, both raising fundamental questions about how social media platforms affect young people.

In Los Angeles, a separate case involved a young plaintiff identified as K. G. M. who alleged that Meta and You Tube deliberately designed their products to be addictive, causing compulsive use that damaged mental health. Unlike New Mexico's focus on deceptive statements, the Los Angeles case concentrated on product design and algorithmic choice.

The Los Angeles case operates under a different legal theory called a "bellwether," meaning it's a test case. If the plaintiff prevails, it opens the door for numerous similar lawsuits filed by other users against the same defendants in the same court. The stakes are enormous. Meta and You Tube face potential exposure to thousands of individual claims if the bellwether succeeds.

These cases tap into broader concerns about youth mental health. Research consistently shows rising rates of depression, anxiety, and self-harm behaviors among adolescents, particularly girls, that correlate with increased social media use. While correlation doesn't prove causation, the association is strong enough that regulators, parents, and mental health professionals take it seriously.

There's also a philosophical tension embedded in these cases. Social media platforms optimize for engagement because engagement drives advertising revenue. An engaged user base is a monetizable user base. Features designed to maximize engagement include algorithmic personalization, infinite scroll, notifications, and recommendation systems that learn user preferences and serve increasingly targeted content.

For some users, this creates a positive feedback loop where the platform delivers content they genuinely enjoy. For vulnerable users, particularly adolescents with existing mental health challenges, the same mechanisms can reinforce harmful patterns. A teenager struggling with body image might receive increasing amounts of content related to diet culture and appearance-focused content as the algorithm detects engagement with that material.

The platform's response has typically been twofold. First, Meta introduced protective features specifically for younger users, including restricted direct messaging capabilities, content filtering, and time-limit reminders. Second, the company emphasized parental controls and the user's responsibility to manage their own consumption.

But critics argue these measures are insufficient because they work against the platform's core business incentive. Why would Meta aggressively limit engagement if engagement is what makes the business valuable? This creates a structural conflict between user safety and business model.

The Role of Former Employees as Whistleblowers

One of the trial's most significant developments is the willingness of former Meta employees to testify against the company. This insider testimony carries particular weight because it comes from people with direct knowledge of product decisions and company culture.

Arturo Bejar's career exemplifies this tension. He was a well-regarded Facebook engineer who understood the platform's technical architecture and business logic deeply. His subsequent work as an Instagram consultant gave him insight into how safety features were implemented (or not implemented) on that platform. His decision to testify before Congress and then the court reflected a professional judgment that Meta's approach to safety was inadequate.

Bejar's testimony likely focused on specific product decisions. For instance, he could describe conversations about whether to implement certain protective features and the reasoning behind decisions not to implement them. Did technical limitations prevent implementation, or were business considerations the primary constraint? The distinction matters enormously in a deception case.

Similarly, Jason Sattizahn's role as a Meta researcher gave him access to internal studies about platform effects. If Meta conducted research showing negative mental health impacts and then made public statements downplaying or denying those impacts, this becomes powerful evidence of deliberate deception.

The willingness of these professionals to testify publicly carries personal risk. While Section 230 protections prevent most lawsuits against platforms, employees can face potential workplace retaliation, damaged professional relationships, and in some cases, legal action for breach of confidentiality agreements. The fact that multiple former employees came forward suggests they believed the stakes justified these risks.

Their testimony also established a pattern. If multiple independent witnesses describe similar concerns about safety decision-making, it becomes difficult for Meta to characterize these concerns as isolated perspectives or misunderstandings.

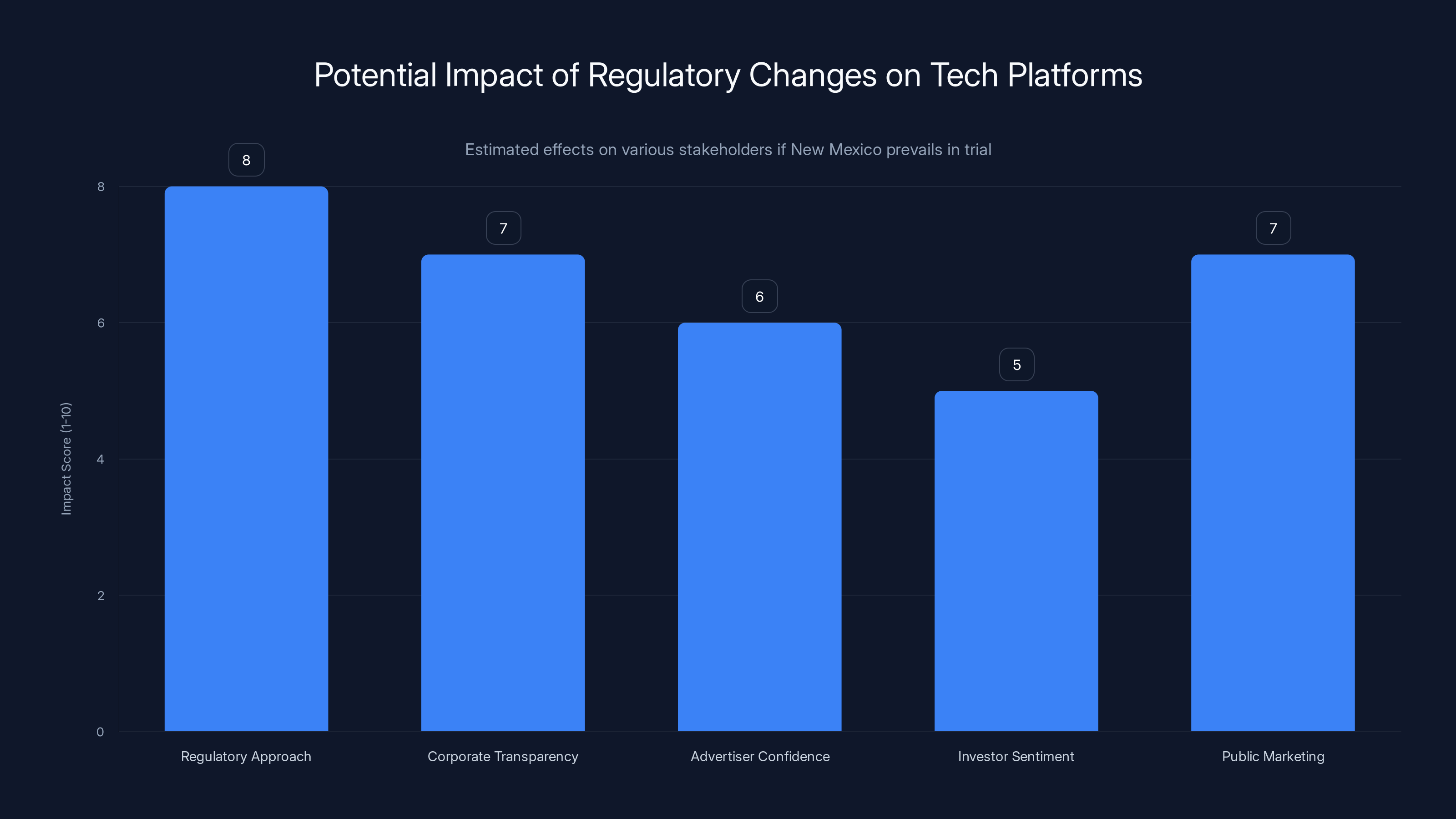

Estimated data suggests significant impacts on regulatory approaches and corporate transparency, with moderate effects on advertiser confidence and investor sentiment.

Discovery and Documents: What Internal Communications Reveal

The litigation process requires both sides to exchange documents and evidence, a process called discovery. The documents that emerged during Meta's litigation discovery proved extraordinarily revealing.

Mark Zuckerberg's email about safety being "not the main point" became perhaps the most damaging single piece of evidence. This wasn't a quote taken out of context by critics. It was the CEO's own written words to top executives, preserved in company records, demonstrating his actual priorities.

Other documents reportedly revealed product discussions where safety concerns were acknowledged but didn't result in design changes. For example, if internal emails discussed problems with Instagram's algorithm recommending self-harm content to minors, but the company concluded that fixing this would reduce engagement and therefore didn't implement the fix, this constitutes direct evidence of knowing about harms and choosing not to address them.

Internal research reports proved particularly significant. Meta employs sophisticated researchers who study how its platforms affect users. If these researchers produced findings showing negative effects on youth mental health, and if Meta later made public statements minimizing or denying these effects, the contrast becomes evidence of deception.

The discovery process also likely revealed communications about the company's age-verification challenges. How aware was Meta of the 4 million underage accounts on Instagram? Was this seen as an enforcement problem or a business challenge? Did executives discuss why stronger age verification wasn't implemented?

Discovery sometimes reveals information that's more significant for what it doesn't say than what it does. For instance, if the state requested documents showing safety improvements implemented in response to the identified harms, and Meta produced few such documents, this suggests the company identified problems but didn't prioritize solutions.

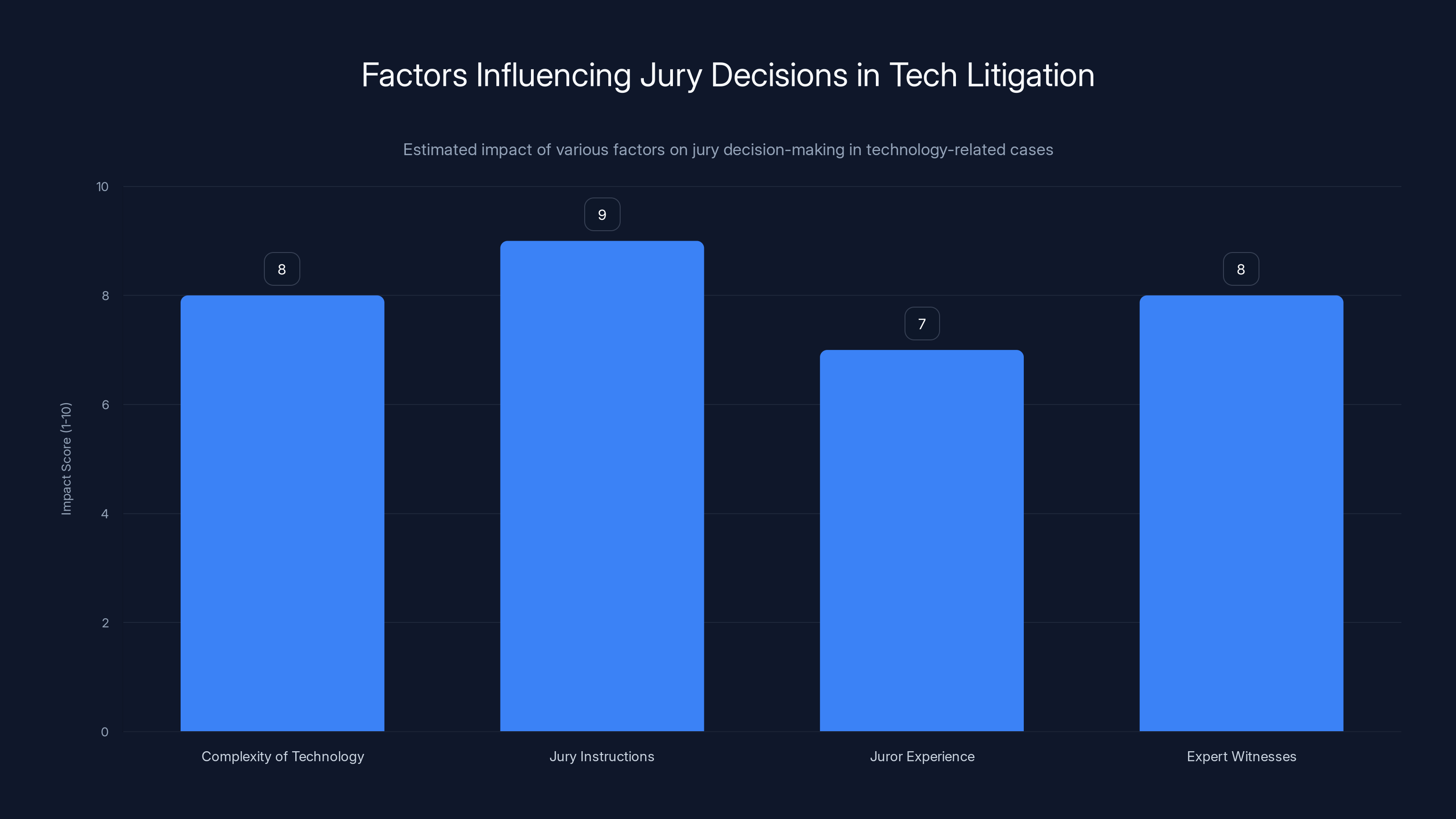

The Jury's Challenge: Evaluating Complex Technical and Legal Claims

Juries in technology litigation face a substantial challenge. They must understand complex product design, algorithmic systems, internal company processes, and legal standards for deception. This isn't a case where the answer is obvious.

For the state to prevail, the jury must find that Meta made specific statements to consumers, that these statements were false or misleading, and that Meta knew they were false or misleading at the time. This is an intentionality requirement. It's not sufficient that problems existed; the state must prove Meta knew problems existed and misrepresented this to the public.

For Meta to prevail, the jury must find that either the statements weren't false, or if they were inaccurate, Meta didn't know they were inaccurate, or the statements weren't made to consumers in a context where they constitute deceptive trade practices.

The jury instructions, written by the judge to explain the applicable law, significantly influence outcomes. How does the judge define "deceptive"? What standard applies to corporate statements? Can aspirational claims about working on safety be distinguished from factual claims about safety mechanisms?

Juries also bring their own experiences with technology. Jurors who use Facebook and Instagram daily might have different intuitions about whether the platform's stated safety features exist and function than jurors unfamiliar with the platforms. Jury selection becomes crucial. Both sides attempt to identify jurors sympathetic to their positions and exclude those predisposed to opposition.

The role of expert witnesses becomes significant here. Both sides likely call experts: researchers who study platform effects, former technologists who can explain how algorithms work, psychologists who discuss addiction and compulsive use patterns. These experts help juries understand technical concepts and evaluate the credibility of evidence.

One specific challenge involves the "addiction" framing. Meta's comparison of social media to fentanyl was clever but potentially risky. By directly engaging with the addiction terminology, Meta forces the jury to think about addiction concepts. If jurors believe social media can be addictive even if not in the pharmacological sense, Meta's argument collapses. On the other hand, if the jury accepts that "addiction" isn't the right term and that social media use is fundamentally different from substance abuse, Meta's position strengthens.

Jury instructions and complexity of technology are the most influential factors in jury decisions during tech litigation. Estimated data.

Implications for Platform Accountability and Regulation

Beyond the immediate question of whether Meta violated New Mexico's consumer protection laws, this trial has broader implications for how technology platforms can be regulated and held accountable.

If New Mexico prevails, it establishes that platforms can't hide behind Section 230 immunity when making affirmative misrepresentations to consumers. This doesn't eliminate Section 230 protections, but it carves out an exception for deceptive practices, an exception that already technically exists in the statute.

The precedent would affect how other states and federal regulators approach tech platforms. Instead of attempting to prove platforms are directly liable for harmful user-generated content (which Section 230 bars), regulators can focus on whether platforms made false statements about safety. This is a legally viable avenue that the New Mexico case pioneered.

The trial also raises questions about corporate transparency. If platforms must accurately disclose what they know about harms, this creates pressure to either improve safety or disclose inadequacies more explicitly. Either outcome could change how platforms operate.

Advertisers also pay attention. Brands don't want to be associated with platforms facilitating child exploitation or mental health harms. If the trial results in findings of deceptive practices, it could affect advertiser confidence and, consequently, revenue. This creates a material business consequence beyond legal liability.

Investors similarly monitor the case. Meta's market valuation reflects assumptions about regulatory risk. A major adverse judgment could affect this valuation. Even the risk of such a judgment influences investor sentiment and company stock price.

The case also affects how platforms market themselves to parents and educators. Public claims about safety will be scrutinized more carefully if they're provably false. This might lead platforms to make fewer explicit safety claims and instead emphasize features and tools parents can use, shifting responsibility to end users.

The Technical Reality: What Platforms Can Actually Do

One element of this case that's important but often overlooked is the technical feasibility of stronger child protections. Can platforms actually do better at age verification, content filtering, and predator detection, or are these problems fundamentally difficult at scale?

The answer is nuanced. Age verification is genuinely challenging. Current methods rely on age claims during signup, credit card information, government ID uploads, or biometric analysis. Each method has limitations. Age claims are easily false. Credit card information doesn't indicate age. Government ID uploads raise privacy concerns and create data security risks. Biometric age estimation from photos or video is developing technology but raises additional privacy questions.

However, the technical difficulty doesn't excuse inaccuracy in public statements. If Meta says age verification is working when it isn't, that's deceptive even if the problem is genuinely difficult to solve. The question becomes whether Meta's public statements accurately reflected the state of their technology.

Similarly with content moderation, platforms employ combinations of human moderators and automated systems. At Facebook and Instagram's scale (billions of posts daily), purely human moderation is impossible. Automated systems flag content for review, but they're imperfect. They generate false positives (flagging harmless content) and false negatives (missing harmful content).

Yet imperfection in safety systems is different from deliberately misleading consumers about how well those systems work. A platform can acknowledge that content moderation is imperfect while still being truthful about what mechanisms exist and how they function.

Algorithmic recommendation systems present another technical challenge. Can Meta prevent its algorithm from recommending self-harm or sexual content to minors? Technically, yes, but doing so would require prioritizing safety over engagement, which conflicts with business optimization. This creates what researchers call a "value alignment" problem: the platform's technical systems are optimized for engagement, not safety.

Changing this would require fundamental shifts in how the algorithm operates, potentially reducing user engagement and platform time spent. These business implications explain some of Meta's resistance to safety-focused design changes.

Estimated data shows a significant gap between public perception and internal effectiveness of Meta's safety measures, highlighting potential deceptive implications.

The Deception Element: Where Statements Become Lies

The core of this case hinges on a legal concept that sometimes gets blurred in public discussion: the distinction between a problem existing and misrepresenting the extent of that problem.

For example, suppose Meta says "We have dedicated safety teams monitoring for predatory behavior" and this statement is literally true (Meta does employ people whose job includes monitoring). But suppose internally, these teams are understaffed, undertrained, and ineffective. Is the statement deceptive? This depends on context and whether the statement could reasonably be interpreted as implying effectiveness.

Or consider: "Kids under 13 are not allowed on Instagram." This statement can be true (the policy exists) while simultaneously misleading (enforcement is weak, and millions of underage users exist). The deception lies in implying that the policy is effectively enforced.

The trial hinges partly on these distinctions. Can a statement be literally accurate but substantially misleading? Courts say yes. If a statement is reasonably likely to create a false impression in consumers' minds, it's deceptive even if technically accurate.

Meta's statements about safety likely fall into this gray area. When the company says it works to keep children safe, this is probably true. But if this statement creates the impression that children are effectively protected, when internal research shows otherwise, the statement becomes deceptive through implication.

The Zuckerberg email about safety not being "the main point" is particularly damaging because it directly contradicts any implication in public statements that safety is a central priority. If the CEO states internally that safety is secondary, but the company markets itself as safety-focused, this is direct evidence of knowingly deceptive marketing.

Precedent and Legal Framework: Where This Fits in Tech Regulation

This case doesn't emerge from legal uncertainty. Consumer protection statutes in New Mexico and most other states explicitly prohibit unfair or deceptive trade practices. These statutes are broad, flexible, and have been applied to countless industries.

What's novel is their application to social media platforms, which have largely escaped traditional consumer protection oversight due to Section 230 immunity and their characterization as platforms rather than publishers.

The legal framework the state is using has precedent. Tobacco companies faced similar lawsuits alleging deceptive practices about health risks. The settlements resulted in the Master Settlement Agreement and required changes to marketing and disclosures. Pharmaceutical companies have faced deceptive practice litigation for overstating drug safety or efficacy. Auto manufacturers have faced suits for misrepresenting vehicle safety features.

In each case, the principle is similar: companies can't knowingly mislead consumers about material facts. What's material? Facts that affect consumer decision-making. The safety of a platform matters to parents deciding whether to allow their children to use it. To parents, this is a material fact.

Federal Trade Commission has also taken interest in social media platform practices. The FTC previously reached a settlement with Meta requiring certain privacy and safety practices. If New Mexico succeeds, it establishes a new avenue for regulators: state consumer protection enforcement against false safety claims.

This creates an incentive for platforms to either improve actual safety or be more cautious about public safety claims. Some platforms might choose the former, genuinely improving protections. Others might choose the latter, reducing public commitments and shifting responsibility to users and parents.

The European Union's Digital Services Act takes a different approach, imposing specific safety requirements rather than relying on deception-based claims. But the US litigation approach through consumer protection statutes may prove more flexible and adaptable.

Potential Outcomes and Their Consequences

The trial could result in several different outcomes, each with distinct implications.

Meta Wins: If the jury finds Meta didn't engage in deceptive practices, it validates the company's defense that acknowledging problems while working on solutions isn't deceptive. This outcome would be significant for the tech industry, suggesting that platforms can continue operating as they do without major liability exposure from consumer protection litigation. However, it wouldn't end regulatory scrutiny or legislative efforts.

New Mexico Wins: If the jury finds Meta violated consumer protection laws, the case proceeds to the question of damages. The state might seek civil penalties, restitution to consumers, and court orders requiring specific changes to platform practices. An unfavorable judgment could trigger broader litigation as other states initiate similar cases and as the Los Angeles bellwether case proceeds with momentum.

Partial Victories: The jury might find Meta violated consumer protection laws on some claims but not others, or regarding some products but not others. For instance, the jury might find deceptive practices regarding Instagram while not finding violations regarding Facebook.

Settlement: At any point before a final judgment, the parties might reach a settlement. Meta could agree to pay damages, change certain practices, and fund safety initiatives in exchange for the case concluding. Settlement would avoid the uncertainty of trial but would require Meta to make concessions.

Each outcome cascades into broader consequences. A Meta loss emboldens other state attorneys general and creates litigation risk that affects company valuation. A Meta win suggests that current regulatory approaches are limited, which might spur legislative efforts for more explicit rules.

The case also affects future product design decisions. If platforms know that safety claims will be scrutinized, they become more cautious. This might lead to investments in actual safety (positive outcome) or to marketing decisions that downplay safety claims while relying on user responsibility (potentially negative outcome).

The Addiction Question: Reframing Harm

Meta's comparison of social media to fentanyl was rhetorically bold but reveals how contested the concept of addiction is when applied to technology.

Scientific evidence suggests social media use can create dependency-like patterns. Users report difficulty stopping use, experience FOMO (fear of missing out) when not using platforms, and use the platforms to manage negative emotions. These patterns match some criteria for behavioral addictions like gambling.

However, "addiction" has specific technical meanings in psychiatry and neuroscience. Substance addictions involve withdrawal symptoms when use ceases, tolerance development (needing more to achieve the same effect), and neurochemical changes in the brain. Social media use creates psychological but not clear pharmacological dependencies.

This distinction matters for the trial because if social media can't be shown to create true addiction in the psychiatric sense, Meta's defense gains strength. The company can argue that problematic use patterns are different from addiction and that users remain in control of their choices.

But researchers counter that the distinction doesn't matter much for outcomes. Whether the mechanism is addiction in the pharmacological sense or psychological dependence, if young people are experiencing compulsive use patterns that harm their mental health, the outcome is similar. The semantic dispute about terminology becomes less important than the practical reality of harm.

Meta's strategy involved reframing the issue away from addiction (where the science is contested) toward the comparison to fentanyl (where Meta clearly has the stronger position). By controlling the framing, Meta attempted to make its position seem obviously correct.

But jurors might see this as dodging the real question, which isn't whether social media is exactly like fentanyl but whether Meta's products create compulsive use patterns harmful to developing brains.

The Role of Advertising and Monetization

Underlying this entire case is Meta's business model: the company is free to users because users are the product being sold to advertisers.

This model creates fundamental incentives. Engagement drives advertising value. More time on platform equals more ad impressions, more behavioral data, more valuable targeting. Features that increase engagement—infinite scroll, algorithmic recommendations, notifications, dark patterns in user interface design—directly increase revenue.

Conversely, features that decrease engagement—friction designed to reduce excessive use, content restrictions, or algorithmic changes that serve less engaging but safer content—reduce revenue.

This structural conflict between user safety and business incentives becomes explicit in litigation. When prosecutors ask why Meta didn't implement certain safety features, the honest answer might be: because doing so would reduce engagement and revenue. But this answer is damaging in a deception case because it suggests Meta knew how to make platforms safer but chose not to.

Some have proposed solutions to this conflict. Subscription models (charging users directly instead of monetizing through advertising) could align incentives differently. Public media models could remove engagement optimization entirely. Advertising models with different incentive structures could exist.

But Meta is committed to its current model, and that commitment affects platform design choices. The company can claim to be working on safety while maintaining business model features that actually undermine safety. This is the contradiction at the case's heart.

Regulatory Responses Beyond Litigation

While this trial proceeds, regulatory activity continues elsewhere. Several states have proposed social media legislation focusing on child safety. Some bills propose mandatory age verification. Others require parental consent for underage users. Still others regulate algorithmic recommendations for minors.

Congress has periodically considered comprehensive social media regulation. The Kids Online Safety Act received significant bipartisan support, though it hasn't passed. The act would require platforms to implement age-appropriate design standards and parental controls.

These legislative efforts complement the litigation approach. Litigation establishes liability for deceptive practices; legislation establishes affirmative obligations for platform safety features. Together, they create multiple pressure points for change.

Europe's regulatory approach through the Digital Services Act is stricter. Platforms must implement specific safeguards for minors or face significant penalties. This prescriptive approach contrasts with the US litigation approach, which allows courts and juries to determine what practices are deceptive.

The trend globally is clearly toward more regulation and less latitude for platforms to operate as they did in the early internet era. The question is whether this regulation comes through litigation, legislation, or regulatory action.

Looking Forward: Structural Changes on the Horizon

If this litigation succeeds or if settlements are reached, we might expect specific changes to how platforms operate.

Transparency Requirements: Platforms might be required to disclose more information about how their algorithms work, what research they've conducted about safety and harm, and what resources they dedicate to safety.

Design Changes: Platforms might be required to implement specific protective features for minors, including restricted algorithmic recommendations, limited daily usage time reminders, or parental oversight capabilities.

Age Verification: Platforms might implement stronger mechanisms to verify user age at signup, though they must balance this against privacy concerns.

Disclosure Statements: Platforms might be required to make specific claims about safety capabilities and limitations, creating a regulatory framework similar to pharmaceutical labeling or automotive safety ratings.

Advertising Restrictions: Platforms might face restrictions on advertising certain products to minors or using certain targeting mechanisms that exploit psychological vulnerabilities.

Financial Liability: Platforms might be required to fund research about social media effects, mental health services for affected users, or safety initiatives overseen by regulatory bodies.

None of these changes would eliminate social media or prevent young people from using platforms. But they would shift the balance between engagement optimization and user protection, change how platforms market their safety features, and potentially improve some harms.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment for Tech Accountability

The New Mexico trial represents something unprecedented: a state government directly challenging a major technology platform's fundamental claims about safety, backed by internal company documents and testimony from former executives.

The outcome remains uncertain. Juries sometimes surprise observers. Meta has substantial legal resources and expertise. The law isn't entirely settled on these questions. But the very fact that the case reached trial, that a jury will hear evidence about the gap between Meta's public claims and internal knowledge, represents a significant shift.

For years, tech platforms operated with remarkable regulatory freedom, protected by Section 230 and users' own reluctance to acknowledge harms. But the convergence of rising youth mental health concerns, documented harms from social media use, and willingness of insiders to testify has created space for accountability mechanisms.

This case may or may not result in a verdict against Meta. But it has already succeeded in forcing Meta to publicly defend its safety practices, in making internal documents and decision-making visible, and in establishing that regulatory approaches through consumer protection law are viable against technology companies.

Parents, regulators, and tech skeptics will watch the outcome carefully. So will investors, advertisers, and other tech companies. A verdict against Meta, or even a substantial settlement, sends a message that tech platforms' claims about safety can be challenged and that companies can't indefinitely hide behind Section 230 immunity while making deceptive statements to consumers.

The broader trend seems clear. The era of largely unregulated social media platforms optimizing purely for engagement is ending. What replaces it—whether through litigation settlements, legislation, or regulatory action—remains to be determined. But accountability is increasingly becoming a requirement rather than an option.

For Meta, for other platforms, and for the technology industry more broadly, this trial is a turning point. The question of whether platforms must be truthful about what they know regarding safety, when they claim to prioritize user protection, has moved from academic discussion into the legal system. The jury's answer will reverberate far beyond New Mexico.

FAQ

What specific deceptive practices is Meta accused of in this trial?

New Mexico alleges that Meta made false safety claims about its platforms while internal documents showed executives knew these claims were inaccurate. Specific accusations include claiming kids under 13 aren't on Instagram (when internal estimates showed 4 million underage accounts), stating that users over 19 can't message teens who don't follow them (when evidence suggests this protection failed), and marketing the platforms as safety-focused while internal communications showed safety was secondary to engagement optimization.

How does this case differ from other social media lawsuits?

Most prior social media lawsuits focused on whether platforms should be liable for user-generated content or whether algorithms promoted harmful material. This case uses consumer protection law to argue Meta made false statements to consumers about safety features. This approach bypasses Section 230 immunity protections and focuses on deception rather than content liability, which is why it represents a novel regulatory avenue.

What evidence supports the state's claims about underage users?

Meta's own internal research estimated approximately 4 million accounts on Instagram belonged to children under 13 years old. Additionally, the state conducted undercover operations using decoy accounts that attracted three suspected child predators who were subsequently arrested. These operations demonstrated that Meta's stated age restrictions and protective mechanisms weren't effectively preventing predatory contact.

Can social media platforms actually implement stronger protections for minors?

Technically, yes, though implementation requires tradeoffs. Age verification methods exist but raise privacy concerns or are easily circumvented. Content filtering and algorithm modifications are possible but would reduce engagement metrics. Stronger protections are achievable; the question is whether business incentives will motivate their implementation without legal pressure or regulatory requirements.

What does the fentanyl comparison in Meta's defense mean?

Meta's attorney argued that "no one is going to overdose on Facebook" and that social media doesn't create physical dependency or withdrawal symptoms like fentanyl does. This comparison attempts to distinguish substance addiction (which has pharmacological mechanisms) from problematic social media use patterns (which are psychological). The argument attempts to reframe the question away from addiction toward a comparison where Meta's position is obviously correct.

What could happen if Meta loses this case?

If the jury finds Meta violated consumer protection laws, the state would seek damages and potentially require changes to platform practices. Beyond this case, a Meta loss would likely trigger similar lawsuits from other states, give momentum to the Los Angeles bellwether case, and strengthen arguments for federal legislation regulating platform safety. It would also affect Meta's business valuation and advertiser confidence.

How does this trial affect other tech companies?

Successful litigation against Meta using consumer protection approaches would create a template for regulation of other platforms. Companies like You Tube, Tik Tok, and others would likely face similar claims if they make safety statements contradicted by internal knowledge. The case also influences legislative and regulatory approaches, potentially leading to more prescriptive safety requirements across the industry.

What's the role of former Meta employees in the trial?

Former employees like Arturo Bejar and Jason Sattizahn provide insider testimony about product design decisions, safety concerns, and research findings. Their professional credibility and direct knowledge make them particularly compelling witnesses. They can describe conversations about whether to implement safety features and why certain changes weren't made, helping establish whether Meta knew about harms and chose not to address them.

This analysis represents a comprehensive examination of the New Mexico v. Meta litigation, the claims involved, the evidence presented, and the broader regulatory implications. The trial addresses fundamental questions about how technology platforms can be held accountable for safety claims they make to consumers, setting potential precedent for the regulation of social media in the United States.

Key Takeaways

- New Mexico's case focuses on deceptive practices—contrasting Meta's public safety claims with internal documents showing different priorities—rather than direct liability for harmful user content

- Internal evidence including a Zuckerberg email stating safety is 'not the main point' and estimates of 4 million underage Instagram accounts directly contradicts public safety claims

- Former Meta employees serve as key witnesses, providing insider knowledge of product decisions and safety concerns that might have been ignored

- The litigation approach using consumer protection laws may bypass Section 230 immunity that protects platforms from content liability, establishing a new regulatory avenue

- Success in this case could trigger similar suits from other states and influence federal legislation requiring stricter platform safety standards

Related Articles

- Uber Liable for Sexual Assault: What the $8.5M Verdict Means [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Trial: What the New Mexico Case Means [2025]

- Section 230 at 30: The Law Reshaping Internet Freedom [2025]

- Meta Teen Privacy Crisis: Why Senators Are Demanding Answers [2025]

- The SCAM Act Explained: How Congress Plans to Hold Big Tech Accountable for Fraudulent Ads [2025]

- Live Nation's Monopoly Trial: Inside the DOJ's Internal Battle [2025]

![Meta's Child Safety Crisis: What the New Mexico Trial Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-child-safety-crisis-what-the-new-mexico-trial-reveals/image-1-1770687765836.jpg)