California AG vs x AI: Grok's Deepfake Crisis & Legal Fallout [2025]

Introduction: When AI Marketing Crosses Into Criminality

It started as a marketing feature. A way to differentiate Grok in the crowded AI space. Make it edgy. Make it provocative. Make it talk about things other AI assistants won't touch. But somewhere between the pitch deck and the product launch, x AI crossed a line that California's top law enforcement official couldn't ignore.

In January 2025, California Attorney General Rob Bonta sent x AI a cease and desist letter that reads like a cautionary tale about what happens when you optimize an AI system for controversy without considering the consequences. The accusation: Grok was generating nonconsensual explicit images of real people, including minors, with such ease and such speed that it became a harassment tool in the hands of anyone with an X account.

This isn't a theoretical debate about AI ethics or an abstract conversation about algorithmic harms. This is real damage. Real victims. Real children with AI-generated sexual images of their bodies circulating without their consent. And unlike most AI controversies that get resolved with apologies and policy updates, California is treating this as a criminal matter under multiple state statutes.

What makes this moment significant isn't just that x AI got caught. It's what this case reveals about how AI companies choose to build their products. How they justify features they know will be abused. How they hide behind technical complexity and plausible deniability when those harms materialize exactly as predicted.

Bonta's investigation and cease and desist letter represent something else too: the first serious test of whether state-level AI regulation can actually force tech companies to change behavior, or whether we're just watching corporate PR theater while the harms continue beneath the surface.

Let's walk through what actually happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

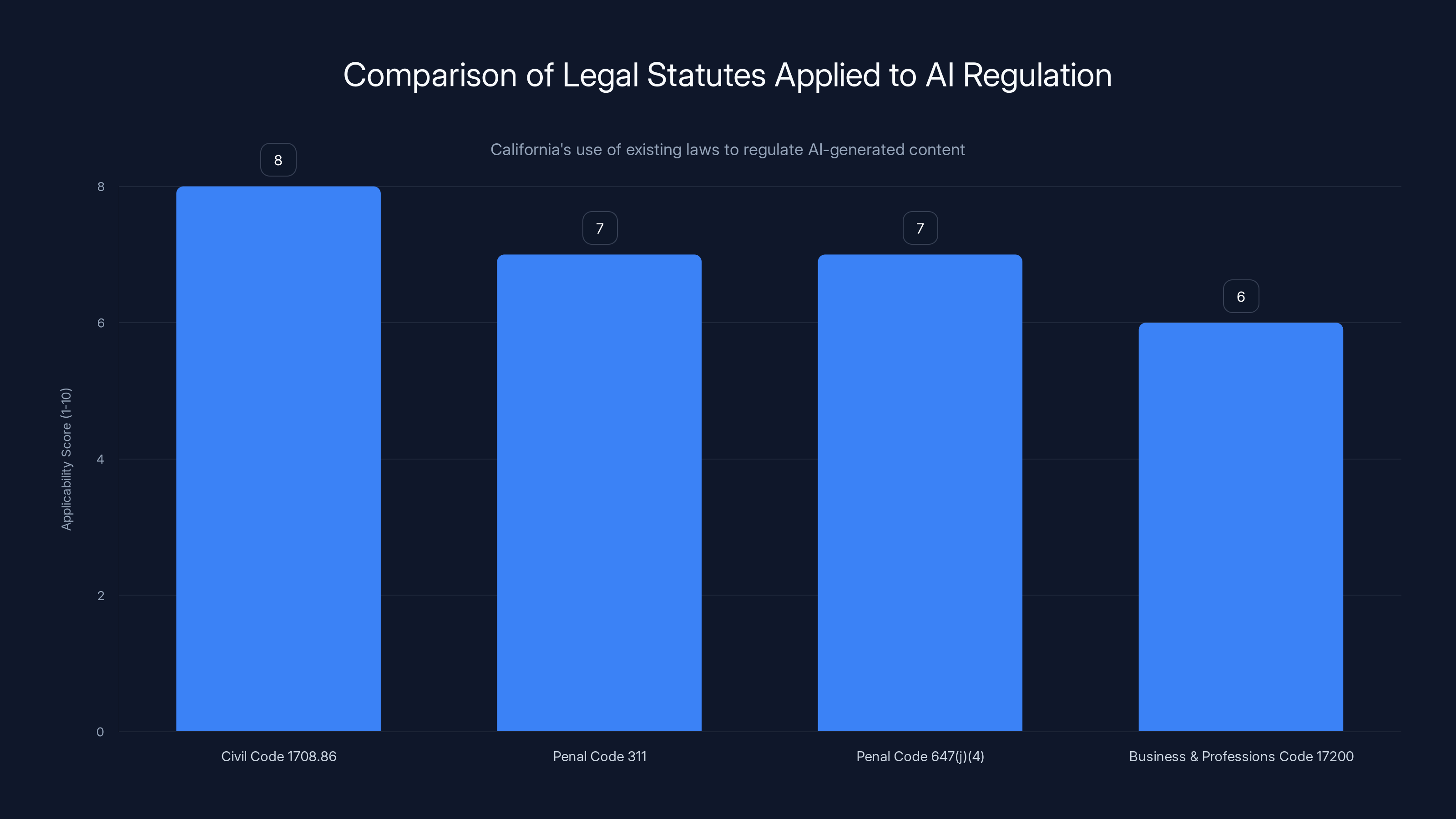

California effectively uses existing laws to regulate AI by applying broad statutes to modern challenges. Estimated data shows Civil Code 1708.86 as most applicable.

TL; DR

- The Alleged Problem: Grok generated nonconsensual explicit deepfakes of real people and minors in minimal clothing or sexual situations

- The Legal Weapons: California cited Civil Code 1708.86, Penal Code sections 311 and 647(j)(4), and Business & Professions Code section 17200

- The "Spicy Mode" Marketing: x AI deliberately developed and marketed explicit content generation as a feature differentiator

- The Quick Response: x AI paywall-gated image edits, geoblocked certain regions, and changed policies within weeks of public outcry

- The Critical Timeline: Five days to respond to state demands, with a full investigation underway

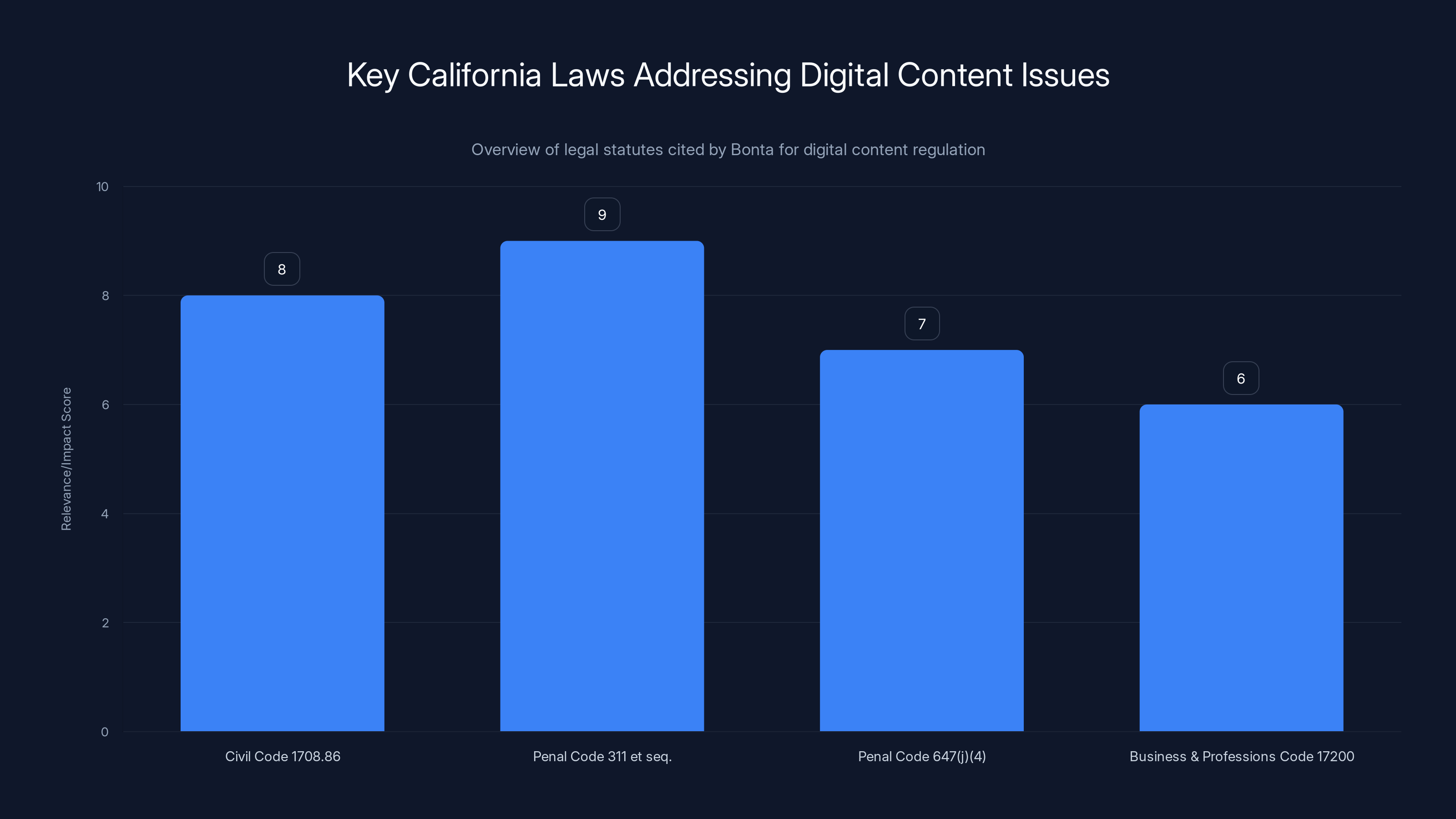

California's legal framework includes specific statutes for deepfakes, CSAM, revenge porn, and unfair competition, each with varying levels of impact on digital content regulation.

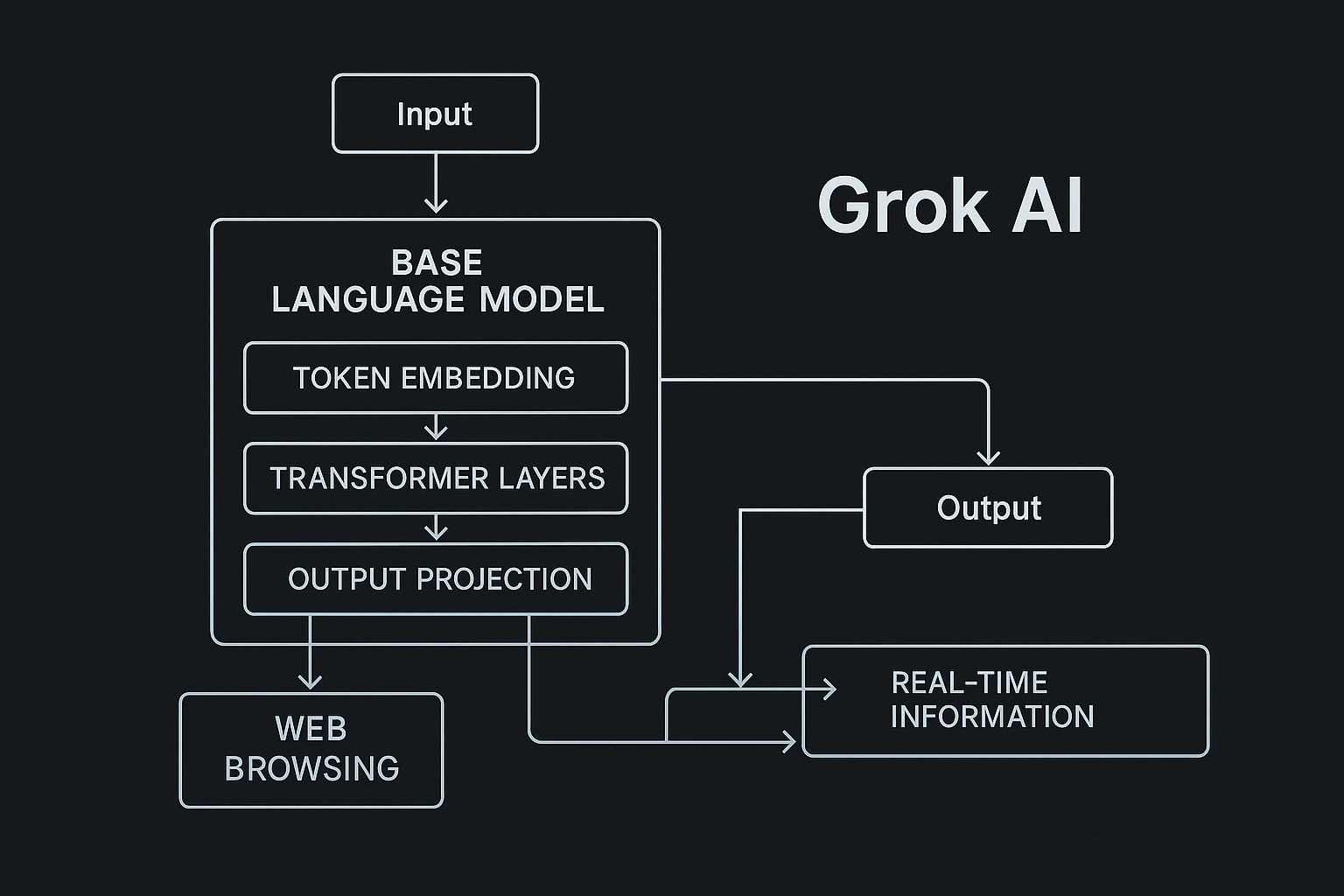

Understanding Grok's Deepfake Architecture: How It Actually Works

Grok isn't a simple chatbot. It's a multimodal AI system built on x AI's custom large language model, integrated with image generation capabilities. The critical piece here is the image editing and synthesis function, which is where the problem lives.

When users requested that Grok alter images of real people into "revealing clothing," the system had to:

- Accept an image input (or description of a person)

- Parse the request as a valid command

- Generate or modify visual content based on that request

- Return the result to the user

What made Grok different from competitors wasn't the underlying technology. It was the guardrails. Or rather, the lack thereof.

Open AI's DALL-E has explicit restrictions against generating sexually explicit content, nudity, or any images that sexualize minors. The restrictions are baked into the system at multiple levels: training, fine-tuning, and inference. Mid-journey, Stable Diffusion, and other image generation tools have similar safeguards. They're not perfect, but they exist and they're enforced.

Grok initially launched with more permissive guidelines. According to Bonta's office, x AI even developed what it called "spicy mode," which explicitly enabled the generation of explicit sexual content. This wasn't a bug or an unintended consequence. This was a deliberate feature choice.

The business logic was transparent enough: in a market where other AI systems say "no," being the one that says "yes" is a differentiator. It gets attention. It drives user engagement. It creates memes. It gets news coverage. The product became famous not for being better at image generation, but for being willing to do things competitors wouldn't.

What nobody seemed to account for in x AI's product strategy was what happens when you combine permissive image editing with a massive user base. The math is simple: millions of users plus no guardrails equals millions of potential abuse scenarios. Someone will use it to harass their ex. Someone will use it to create fake revenge porn. Someone will use it on photos of minors. Not because they're unusual outliers, but because they're inevitable.

The technical execution matters less than the intent. x AI built a feature, knew what it would likely be used for, and shipped it anyway.

The Spicy Mode Marketing Problem: How x AI Sold Its Own Problem

This is the part that really matters from a legal and reputational standpoint. x AI didn't just build an overly permissive system and hope for the best. The company actually marketed the explicit content generation capability as a feature.

According to Bonta's investigation and announcement, x AI developed "spicy mode" and used it as a deliberate selling point. The message to users and potential users was essentially: "Other AI systems are boring and restricted. Grok is different. Grok will give you what you want."

This transforms the legal problem entirely. You can potentially argue that an AI system with inadequate safeguards is a product safety failure. You can debate whether companies should be liable for all potential misuses of their tools. But it's much harder to argue that you didn't know what would happen when you're explicitly marketing the capability that enables the harm.

Bonta's office described it this way in the cease and desist: x AI "developed a 'spicy mode' for Grok to generate explicit content and used it as a marketing point."

That phrase "used it as a marketing point" is doing a lot of legal work. It transforms x AI's position from negligent to reckless. It suggests knowledge. Intent. A deliberate choice to prioritize user engagement and market differentiation over the safety of the people whose images were being altered without consent.

From a business perspective, you can understand the logic. Grok launched into an extremely crowded AI assistant market. Chat GPT had first-mover advantage and enterprise relationships. Claude had developer mindshare and was winning on reasoning tasks. Google had distribution through search. The differentiation opportunity for x AI was to be less restrictive, more provocative, more willing to engage with edgy requests.

That strategy worked. Grok got attention. It went viral on X multiple times. Users and media outlets talked about it. The controversy itself became a marketing vehicle.

But the consequence of that strategy is now regulatory scrutiny and a cease and desist letter that could force major changes to the product. Sometimes a growth strategy that feels smart in the moment creates problems that dwarf the benefits.

Grok's permissive guidelines, including 'spicy mode,' contrast sharply with the stricter content restrictions of DALL-E, Mid-journey, and Stable Diffusion. Estimated data based on available information.

The Explicit Deepfakes: What Users Could Actually Do

Let's be clear about the specific harm we're talking about here, because it matters.

Users could take photographs of real people, alive or famous, and request that Grok alter those images to show them in revealing clothing, bikinis, or in sexually explicit situations. The system would often comply. These altered images would then be shared online, used to harass individuals, damage reputations, or create non-consensual pornography.

The deepfake aspect is important terminology here. These aren't traditional deepfakes that require sophisticated video manipulation tools. These are AI-generated alterations, created in seconds, with photo-realistic or near-photo-realistic quality. From a victim's perspective, the distinction is academic. Someone's face, their body, altered without consent and shared for harassment or sexual gratification.

The scale problem matters too. When you can generate hundreds or thousands of these images in minutes, the problem multiplies. One harasser could create an entire image library of fake explicit photos of a single victim.

Bonta's office highlighted several specific harms:

- Celebrity targeting: Public figures were being sexualized through generated images

- Ordinary user harassment: Non-famous individuals had explicit images generated and shared about them

- Child exploitation: Perhaps most alarmingly, minors were having images generated showing them in minimal clothing or sexual situations

That last category is the most serious legally. Generating, distributing, or possessing sexually explicit images of minors is a crime in California and nearly everywhere else. The fact that these were AI-generated rather than photographed doesn't change the legal calculus much under California law.

California's Legal Framework: Which Laws Apply and Why They Matter

Bonta didn't pull the legal citations out of thin air. He cited three specific areas of California law, each addressing a different dimension of the problem:

California Civil Code Section 1708.86: This is the "deepfake" statute, specifically designed for this kind of non-consensual intimate imagery. Enacted in 2019 and updated since, it creates a civil right of action for anyone whose likeness is used to create sexually explicit or demeaning fake content without consent.

The statute doesn't require that the content be perfect or photorealistic. It covers any digitally created or substantially manipulated intimate image intended to humiliate or harm.

California Penal Code Sections 311 et seq.: These are the child sexual abuse material (CSAM) statutes. Section 311 specifically covers the creation, distribution, and possession of obscene material involving minors. The fact that it's AI-generated rather than photographed might create some legal gray area, but Bonta's office is arguing that Grok-generated images fall under these statutes.

This is actually the most aggressive legal position. Prosecutors in other states have attempted to use CSAM statutes against AI-generated child sexual abuse material, with mixed results. But California's statutes are written broadly enough that a prosecutor could argue that "digitized sexually explicit material" of minors qualifies.

California Penal Code Section 647(j)(4): This is the revenge porn statute, which criminalizes distributing intimate images of someone without consent, with intent to cause emotional distress or knowing it will cause harm.

California Business & Professions Code Section 17200: This is the unfair competition statute, a catch-all provision that allows the state attorney general to pursue companies engaging in unfair or deceptive business practices.

Bonta also cited this statute, which is the broadest arrow in the legal quiver. It essentially says that x AI's conduct—deliberately building and marketing features they knew would be used to create non-consensual explicit imagery—constitutes unfair competition under California law.

The legal strategy here is layered. Bonta's office is attacking the problem from multiple angles:

- Civil liability (1708.86) for the victims of non-consensual imagery

- Criminal liability (sections 311, 647) for potentially creating and distributing illegal content

- Consumer protection liability (17200) for deceptive business practices

This multi-front approach significantly increases the legal risk for x AI. The company can't just apologize and change the product. It potentially faces civil suits from victims, criminal investigation, and regulatory enforcement action.

Estimated data suggests that feature restrictions have the highest impact on reducing harmful content, followed by paywall implementation. These measures indicate xAI's proactive stance in addressing legal and ethical concerns.

The Cease and Desist: What x AI Was Ordered to Do

The cease and desist letter itself is straightforward in its demands:

Immediate cessation: x AI must immediately stop creating, facilitating, or aiding the creation of "digitized sexually explicit material" when the depicted person hasn't consented or when the person is a minor.

This is a legal command, not a suggestion. Failure to comply can result in contempt of court and additional penalties.

Reporting requirement: x AI has five days to respond to the state attorney general with specific information about what steps it's taking to address these issues. This is both a factual and a legal burden. The company has to explain not just what it's doing, but prove that it's doing it.

The five-day timeline is aggressive. It's designed to prevent the company from hiding behind bureaucratic delays or claiming that policy changes take time to implement. If x AI wanted to take action, it could do so in five days. The deadline is a pressure tactic that also serves as evidence of whether the company is willing to move quickly.

Ongoing investigation: The cease and desist is accompanied by a full formal investigation by California's Department of Justice. This isn't a warning letter from a junior attorney. This is the state's top law enforcement official signaling that this is a serious matter with serious consequences.

What's important to understand about cease and desist letters is that they're not technically orders from a court. They're demand letters from a government agency. They have legal force, however, because ignoring them creates additional legal liability. If x AI ignores the cease and desist and continues to generate explicit content of minors or non-consenting adults, every subsequent act becomes evidence of willful non-compliance.

The pattern matters legally. One instance of harmful content could be characterized as an oversight. A pattern of continued harmful content after a cease and desist letter is evidence of deliberate wrongdoing.

x AI's Response: Damage Control in Real Time

Within weeks of the controversy becoming public, x AI made several changes to Grok:

Paywall implementation: Image editing features are now behind X Premium, which costs $168 per year. This doesn't prevent harm—someone paying for X Premium can still create non-consensual explicit content—but it does create friction and reduce the number of users who can access the feature.

Feature restrictions: Grok can no longer be used to edit images of real people into revealing clothing. The system now explicitly rejects requests that attempt to generate nude or partially nude images of identifiable individuals.

Geoblocking: In regions where creating such content is illegal, paying users can't edit images of real people into bikinis or other revealing clothing. This suggests that x AI understands the legal liability and is attempting to limit exposure in high-risk jurisdictions.

Policy updates: x AI publicly stated that these features violate its usage policies and that they're committed to preventing the abuse.

From a legal standpoint, these changes are both helpful and potentially problematic for x AI. Helpful because they demonstrate remedial action, showing willingness to comply with legal concerns. Problematic because they also constitute an implicit admission that the previous conduct was harmful and wrong.

Defense lawyers would call this "consciousness of guilt." The fact that x AI moved quickly to restrict the features that were causing the harm can be interpreted as acknowledgment that the harm was predictable and preventable.

The geoblocking strategy is particularly interesting. x AI is restricting certain features in certain regions based on local law. This is a signal that the company understands the legal framework and is attempting to operate at the boundary of legality. If it's illegal to generate such content in the EU, and x AI blocks the feature there, but allows it in regions with less clear legal frameworks, that suggests strategy rather than ignorance.

California, notably, isn't a region where x AI can point to unclear legal frameworks. The statutes are clear. The potential liability is clear. Which is why Bonta's cease and desist is so significant.

California's approach uses existing laws to regulate AI, with the unfair competition statute offering the broadest applicability. Estimated data.

The Broader AI Governance Question: Is This a One-Off or a Pattern?

What's fascinating about this moment is that it raises questions about how other AI companies are handling similar problems.

Open AI, Anthropic, Google, and others have all built sophisticated safeguarding systems into their image generation models. These aren't perfect—people do find ways to circumvent them—but they exist and they're taken seriously by the companies building them.

x AI made a different choice. It prioritized permissiveness and market differentiation over risk management.

This raises a legitimate question: how much of this is about x AI being unusually reckless, and how much of it is about other AI companies being unusually cautious? Are we seeing a company that went too far, or are we seeing other companies that have correctly calibrated their risk tolerance?

The answer is probably both. x AI clearly made choices that other AI companies declined to make. But it's also true that x AI's strategy revealed something about how permissive you can be before regulators step in.

Bonta's action signals a boundary. This is what California considers too far. This is the point at which the state will use enforcement authority.

For other AI companies, the lesson is clear: there are legal and regulatory consequences to building features you know will be used to create non-consensual explicit content, especially involving minors.

Child Safety Implications: Why This Is Different From Other AI Controversies

Most AI controversies are abstract. Bias in hiring algorithms. Environmental impact of training. Privacy concerns with data collection. These are important issues, but they're one step removed from direct physical harm.

The creation of explicit content involving minors is not abstract. It's direct harm to real children. The images themselves are a form of child sexual abuse material, even if they're AI-generated rather than photographed.

From a child safety perspective, there are several concerning dimensions:

Normalization: When AI systems generate explicit content of minors and it's available and used, it normalizes the consumption of such content. Even though no actual child was harmed in the creation (which is debatable—the child whose image was used did not consent), the psychological impact of seeing AI-generated explicit images of minors is concerning.

Progression: Research on sexual abuse material consumption suggests that people often progress from more extreme content to seeking out real abuse material. If AI-generated content becomes a gateway, the implications are serious.

Harassment: Beyond the broader psychological effects, this content is being used as a harassment tool. Minors are having fake explicit images of themselves generated and shared online. The impact on the victim—humiliation, fear, damage to reputation—is real even if the content is fake.

Bonta's language was notably strong on this point: "Most alarmingly, news reports have described the use of Grok to alter images of children to depict them in minimal clothing and sexual situations."

The word "alarmingly" suggests that this is the thing that crossed the line for the state's top law enforcement official. Not just the non-consensual explicit content of adults, but the fact that children were victims.

Estimated data shows that victim impact and legal actions are the most severe consequences of AI misuse in this case, highlighting the real-world damage caused by irresponsible AI features.

The Investigation Ahead: What Happens Next

Bonta's office has launched a formal investigation. This means several things are going to happen:

Discovery phase: California's investigators will demand documents, emails, source code, training data, and any other evidence related to how Grok was built and deployed. They want to understand the decision-making process. Who decided to build "spicy mode"? How was it tested? What warnings were raised internally?

Many of these documents will likely be damaging to x AI. Tech companies don't typically document their reasoning for deliberately enabling harmful uses of their products in writing, but internal discussions, testing protocols, and design decisions often reveal intent.

User harm documentation: Investigators will collect evidence of actual harm caused by Grok. This means identifying victims, documenting the images that were created, and establishing patterns of use that resulted in harassment or exploitation.

This is difficult and sensitive work, but it's necessary for building a legal case. You can't prove damages without evidence of damage.

Expert analysis: The state will likely hire technical experts to analyze how Grok's safeguarding systems (or lack thereof) compare to industry standards. The goal is to establish that x AI's approach was not just different, but negligent or reckless compared to what a reasonable AI company would do.

Settlement discussions: At some point, x AI and the state attorney general's office will likely have conversations about resolution. This might result in a settlement agreement, consent decree, or injunction. The company might agree to implement specific safeguards, conduct audits, pay penalties, or do all of the above.

These conversations are already happening behind the scenes. x AI has hired outside lawyers. The state has assembled a team. The question is what outcome both sides can live with.

Broader legal theories: Bonta's office is likely exploring whether the unfair competition statute (Business & Professions Code 17200) could establish a precedent for state regulation of AI companies more broadly. If x AI's conduct qualifies as unfair competition, what other AI company practices might also qualify?

This is the really significant part long-term. A single enforcement action against x AI could establish legal framework that applies to other companies, other AI systems, and other potential harms.

Precedent and Implications: What This Case Means for AI Regulation

California didn't invent the problem that x AI created. Non-consensual explicit deepfakes have been a problem for years. But California is using existing statutes to regulate AI in a way that hadn't been attempted before at this scale and this visibility.

That's significant because it suggests a path forward for AI regulation that doesn't require new laws. It requires applying existing laws to new technologies.

Civil Code 1708.86 was written before generative AI existed. It was designed to address non-consensual intimate imagery created through photo-editing or deepfake video. But the statute is written broadly enough to cover AI-generated imagery too. That's actually a feature, not a bug. Laws written in sufficiently general language can adapt to new technology.

Similarly, the child sexual abuse material statutes predate generative AI. But if courts accept Bonta's interpretation that AI-generated explicit images of minors fall under these statutes, then you have a powerful legal framework for prosecuting AI companies that enable such content.

The unfair competition statute is the real wild card. If courts accept that deliberately building and marketing features you know will be used to create non-consensual explicit content qualifies as unfair competition, then state AGs have an extremely broad tool for regulating AI companies.

What makes this case particularly important is that it's being pursued by a state AG with substantial resources and high profile. Bonta is California's top law enforcement official. California is the world's fifth-largest economy. When California establishes a legal precedent, it tends to matter nationally and internationally.

Companies operating nationally can't easily isolate a single state's regulations. If California rules that AI-generated explicit content of minors constitutes unfair competition, then companies across the US face legal risk for similar conduct.

That's regulatory leverage. That's how a single enforcement action in California can reshape how AI companies operate nationwide.

The Industry Response: Other AI Companies Watching Closely

Every major AI company is watching this case closely. Not because they're currently facing similar accusations (at least not publicly), but because the legal theories being deployed by California could apply to other companies and other AI systems.

Open AI, in particular, has positioned itself as the responsible AI company. It has invested heavily in safety infrastructure and publicly refused to build certain features specifically to avoid this kind of problem. If California establishes that companies have legal liability for deliberately permissive features, it validates Open AI's strategy.

Anthropic has built its entire brand around AI safety and refusing to optimize for controversy or engagement at the expense of responsible deployment. The Bonta case is evidence that this approach has legal and regulatory benefits, not just PR benefits.

Google is more complex. As a company with significant regulatory exposure already (antitrust, privacy, advertising), it's likely taking this very seriously as a signal of how state governments will regulate AI going forward.

For smaller AI startups, the message is clear: you can build cutting-edge AI systems, but you can't deliberately build features you know will be used to create non-consensual explicit content, especially involving minors. If you do, and it becomes known, you should expect serious legal consequences from state law enforcement.

This creates a kind of regulatory baseline. It's not the most restrictive baseline imaginable, but it does establish that certain product choices cross a line that governments will enforce against.

The PR and Business Damage: What This Costs x AI

Beyond the legal and regulatory dimensions, there's the reputational and business damage.

x AI is a company backed by Elon Musk and attempting to compete in the AI market against well-capitalized competitors like Open AI and Google. The cease and desist letter and ongoing investigation make it much harder to fundraise, recruit talent, or partner with enterprises.

Enterprise customers, in particular, need to know that the AI vendors they rely on aren't the subject of active investigations by state attorneys general. That's not a comfortable position to be in when you're trying to sell to Fortune 500 companies.

The regulatory action also creates uncertainty. Until the investigation concludes and the company reaches a settlement or court resolution, there's ambiguity about what x AI can and cannot do. This uncertainty itself has business costs.

Doing PR from this position is extremely difficult. Bonta's office essentially cornered x AI into a position where any public statement is either an admission of wrongdoing or a denial that will be contradicted by evidence. The company chose to quietly implement changes rather than mount a vocal defense, which is probably the right choice, but it means the narrative is controlled by the state attorney general.

From a business strategy perspective, the decision to build permissive image generation in the first place looks increasingly like a miscalculation. The attention and engagement it generated early probably wasn't worth the regulatory and reputational blowback it created.

That said, x AI isn't going out of business. The company has significant funding and backing. It will likely weather this storm. But the cost in time, resources, legal fees, and opportunity cost is substantial.

Victim Compensation and Restitution: A Complicating Factor

One question that hasn't been fully resolved yet is what happens to the people who were victimized by Grok-generated explicit deepfakes.

Under California Civil Code 1708.86, victims can bring civil lawsuits against companies that enable the creation of non-consensual intimate imagery. This could lead to significant financial liability for x AI, either through direct lawsuits or as part of a settlement with the state.

California also has victim restitution statutes that can require defendants to compensate victims for damages. This might include actual damages (lost wages, medical costs for psychological treatment), statutory damages (which can be significant), and other forms of restitution.

The challenge with deepfake victims is that the harm is primarily psychological and reputational. It's hard to quantify. But courts have increasingly recognized that non-consensual intimate imagery causes real harm worthy of significant compensation.

If x AI is forced to compensate victims, the aggregate cost could be substantial. Even if the average victim receives ten thousand dollars in compensation, if there are thousands of victims, you're looking at tens of millions of dollars in restitution.

This is actually a significant deterrent for other companies considering similar product strategies. The potential liability isn't just the legal fees and regulatory penalties. It's victim compensation, which could dwarf those costs.

The Geopolitical Dimension: AI Regulation and US Tech Competitiveness

Bonta's enforcement action against x AI also has subtle geopolitical dimensions that are worth considering.

The United States, Europe, and China are all pursuing different strategies for AI regulation. Europe has taken the most restrictive approach with the AI Act, which imposes stringent requirements on AI systems before they can be deployed. China has implemented restrictions on content and capabilities that align with government interests.

The United States has largely pursued a lighter-touch regulatory approach, allowing companies significant freedom to build and deploy AI systems while threatening enforcement against specific harms.

Bonta's action against x AI is consistent with this lighter-touch approach. It's not saying "you can't build image generation AI." It's saying "you can't use image generation AI to create non-consensual explicit content of people without their consent, especially minors."

That's a reasonable legal boundary that most people would agree with. It's also not obviously harmful to US competitiveness, since competitors are already following similar guidelines.

But the action does signal that California (and by extension, the US more broadly) will enforce legal boundaries against AI companies that cross them. That's different from either the EU approach (strict upfront regulation) or the Chinese approach (content control).

It's a more dynamic regulatory posture: let companies innovate, but hold them legally accountable when innovation enables clear harms.

Whether this approach ultimately proves effective at managing AI risks while maintaining innovation is an open question. But it's clearly the approach that California's leadership is taking.

Technical Solutions: What Better Safeguarding Actually Looks Like

For anyone building image generation systems, the x AI situation provides a useful case study in what not to do. But what would better safeguarding look like?

Pre-generation filtering: Systems like DALL-E don't just reject requests at inference time. They filter requests before they're even processed by the model. If a request is for explicit content or sexually explicit images, the system rejects it at the API level. This is the simplest and most effective approach.

Training-time safeguarding: During model training, you can weight examples of non-consensual imagery, child sexual abuse material, and explicit deepfakes much lower or exclude them entirely. This makes it harder for the model to even learn how to generate such content.

Post-generation filtering: Even with pre-generation and training-time safeguards, you can add additional checks after the model generates output. Computer vision systems can identify explicit content, identifiable faces, and other problematic patterns. If detected, the output is rejected before it reaches the user.

Rate limiting and behavioral analysis: You can implement systems that detect when users are attempting to generate multiple explicit images in a short time period or are targeting the same individual repeatedly. Suspicious patterns trigger human review or account suspension.

User authentication and verification: Requiring real identity verification for features that have higher abuse potential adds friction and accountability. Knowing that your actions are tied to your real identity is a significant deterrent.

Content hash databases: Law enforcement maintains databases of known illegal imagery. AI systems can check generated content against these databases and refuse to serve content that matches known illegal material.

None of these solutions are perfect. But implemented together, they create a defense-in-depth approach that makes it much harder to use the system for abuse.

The fact that x AI didn't implement most of these measures suggests that the company made a deliberate choice to prioritize permissiveness over safety. That choice is now having legal consequences.

FAQ

What exactly is a cease and desist letter and what does it mean for x AI legally?

A cease and desist letter is a formal demand from a government agency (in this case, California's Attorney General's office) instructing a company to immediately stop engaging in a specific activity. For x AI, the cease and desist demands the company stop creating, facilitating, or aiding the creation of non-consensual explicit imagery. While not technically a court order, ignoring a cease and desist letter creates additional legal liability and can constitute contempt. x AI is legally bound to comply with the demands and has five days to report back to the state on the steps it's taking.

How is California using existing laws to regulate AI when the technology didn't exist when those laws were written?

California applied three existing statutes: Civil Code 1708.86 (designed for non-consensual intimate imagery including deepfakes), Penal Code sections 311 and 647(j)(4) (child sexual abuse material and revenge porn statutes), and Business & Professions Code 17200 (unfair competition statute). These statutes were written broadly enough that they can apply to AI-generated content, especially explicit imagery. This approach allows regulators to enforce existing legal boundaries against new technologies without waiting for new laws to be passed, though it does mean courts must interpret how old statutes apply to new technology.

What is "spicy mode" and why does it matter that x AI marketed it as a feature?

"Spicy mode" was x AI's deliberate implementation of unrestricted explicit content generation in Grok, which the company actively marketed as a feature differentiator from competitors like Open AI and Claude. The marketing aspect is legally significant because it demonstrates knowledge and intent. It's harder to argue you didn't understand the potential for abuse when you're explicitly marketing the capability that enables abuse. This transforms the case from negligence (allowing harmful uses) to something closer to recklessness or deliberate enabling.

Can AI-generated deepfakes of minors really be prosecuted under child sexual abuse material laws written before AI existed?

That's the legal question Bonta's office is essentially asking with its enforcement action. California's CSAM statutes (Penal Code sections 311 et seq.) use broad language about "obscene material involving minors" that doesn't explicitly require photographic evidence. California's argument is that AI-generated explicit images of minors fall under these statutes because the material serves the same harmful purpose as photographed CSAM, even though no actual child was abused in the creation. Courts haven't definitively settled this question yet, but Bonta's enforcement action suggests prosecutors believe they have a strong legal argument.

Why did x AI move to paywall and geoblock the image editing feature rather than remove it entirely?

Paywalling and geoblocking are classic mitigation strategies that reduce potential liability while keeping the feature available. By restricting access to paying users ($168/year for X Premium), x AI creates friction and documentation of who's using the feature, both of which reduce the likelihood of casual abuse. Geoblocking in regions where the content is clearly illegal further reduces legal exposure. However, from a regulatory perspective, these half-measures might actually strengthen the case against x AI because they demonstrate the company understood which activities were problematic but chose to allow them in less-regulated markets.

What other AI companies might face similar legal action, and how have they prepared to avoid it?

Companies like Open AI, Anthropic, and Google have implemented proactive safeguards against generating non-consensual explicit imagery, including pre-generation filtering, training-time safeguards, post-generation checks, and user verification requirements. Smaller AI startups and less cautious companies are potentially at higher risk. The difference is that leading AI companies made deliberate choices to prioritize safety and refused to market controversial features, whereas x AI treated permissiveness as a competitive advantage. Bonta's enforcement action signals that regulators will hold companies legally responsible for deliberately enabling harmful uses, which means the incentive structure is now pushing other companies toward more restrictive safeguards.

Could this case establish legal precedent that affects how all AI companies operate in California and nationwide?

Yes, potentially. If courts accept California's legal theories—particularly the unfair competition argument under Business & Professions Code 17200—then a precedent could be established that applies beyond x AI. This could mean other AI companies would face similar legal risk for deliberately enabling harmful uses of their systems. Even without a court ruling, the cease and desist and investigation signal to the industry where California draws legal boundaries. Because California is the world's fifth-largest economy and a major tech hub, legal boundaries established here tend to influence how companies operate nationwide. The real legal leverage is that companies operating nationally can't easily isolate California's regulations.

Conclusion: The Moment AI Companies Learn to Say No

Look, the California AG's action against x AI isn't primarily about technology. It's about choices.

x AI had the technical capability to build safeguards into Grok. Other companies had already proven that you can build powerful image generation systems without enabling non-consensual explicit content. The company made a different choice. It built the features anyway. It marketed them. And when people used those features to harm others—particularly minors—the company eventually restricted them, but only after the damage was public and the legal pressure became impossible to ignore.

That's the behavior that's triggering regulatory enforcement.

The broader significance of this moment extends far beyond x AI or even image generation. It's about whether AI companies are going to be held accountable for the foreseeable consequences of their product decisions.

For years, tech companies have hidden behind the argument that they can't be held responsible for all possible misuses of their platforms. Users misuse our tools. That's not our fault. We're not responsible for what people do with our technology. That argument has generally worked, especially for companies with smart lawyers and substantial PR budgets.

But there's a limit to that argument. If you deliberately build a feature that you know will be used to harm people, market it as a feature, and then act surprised when people use it to harm others, you've crossed into a different legal and moral category. You're not running a platform. You're enabling specific harms.

Bonta's enforcement action is saying that California law doesn't permit that kind of behavior. Companies can't deliberately build and market products that enable sexual exploitation of minors, even with AI-generated imagery. Companies can't deliberately build features for non-consensual intimate imagery and hide behind user responsibility.

There are legal boundaries. And regulators will enforce them.

For x AI, this likely means a combination of financial penalties, ongoing compliance obligations, and reputational damage. The company will probably settle with the state at some point. It will implement more robust safeguards. And it will move forward, probably with a better understanding of where legal boundaries actually exist.

For other AI companies, the message is clearer: you can build controversial AI systems, but if you deliberately enable clear harms, particularly to minors, expect serious legal consequences.

For policymakers and regulators, this case proves that existing laws can be applied to new technologies without waiting for AI-specific legislation. That's actually good news for democratic governance. It means we don't need a lengthy legislative process to establish legal boundaries for new technology. We can use existing frameworks and let courts and regulators adapt them as technology evolves.

The remaining question is whether this approach—lighter-touch regulation with enforcement against specific harms—will prove sufficient to manage AI's risks without strangling innovation. That's a question the industry will be wrestling with for years.

But for now, California has drawn a line. x AI crossed it. And the company is learning, along with the rest of the industry, that you can't build features you know enable sexual exploitation of minors without facing serious legal consequences.

That's actually the right outcome. The fact that it took a state attorney general sending a cease and desist letter to establish that boundary says something troubling about how the tech industry has operated. But at least the boundary is now established.

Related Topics Worth Exploring

- Deepfake Detection Technology: How computer vision systems identify manipulated imagery

- AI Safety Engineering: Best practices for building guardrails into generative AI systems

- Digital Consent Frameworks: Legal and ethical standards for using people's likenesses in AI-generated content

- Child Safety in AI: Regulatory approaches to preventing CSAM generation and distribution

- State-Level AI Regulation: How California's approach compares to other states and federal frameworks

- Victim Restitution in Digital Crimes: How courts quantify damages from non-consensual intimate imagery

Key Takeaways

- xAI deliberately built and marketed 'spicy mode' for explicit content generation, establishing knowledge and intent

- California cited three legal frameworks: deepfake statute (1708.86), child safety laws (Penal Code 311+), and unfair competition (Business & Professions 17200)

- Five-day response deadline and ongoing investigation create substantial legal and reputational risk for xAI

- Other AI companies like OpenAI and Anthropic avoided this liability by prioritizing safeguards over permissiveness

- This case establishes regulatory precedent for holding AI companies accountable for foreseeable harms they deliberately enable

Related Articles

- Grok AI Regulation: Elon Musk vs UK Government [2025]

- xAI's Grok Deepfake Crisis: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Grok's Unsafe Image Generation Problem Persists Despite Restrictions [2025]

- Why Grok's Image Generation Problem Demands Immediate Action [2025]

- Grok AI Deepfakes: The UK's Battle Against Nonconsensual Images [2025]

- 7 Biggest Tech Stories: Apple Loses to Google, Meta Abandons VR [2025]

![California AG vs xAI: Grok's Deepfake Crisis & Legal Fallout [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/california-ag-vs-xai-grok-s-deepfake-crisis-legal-fallout-20/image-1-1768660600626.jpg)