Introduction: When Autonomous Vehicles Meet Unpredictable Pedestrians

On January 23rd, 2025, a Waymo robotaxi struck a child near an elementary school in Santa Monica, California, during normal school drop-off hours. The incident happened quickly, unexpectedly, and in exactly the kind of chaotic environment that autonomous vehicles struggle with most: a busy school zone with double-parked cars, crossing guards, and unpredictable young pedestrians.

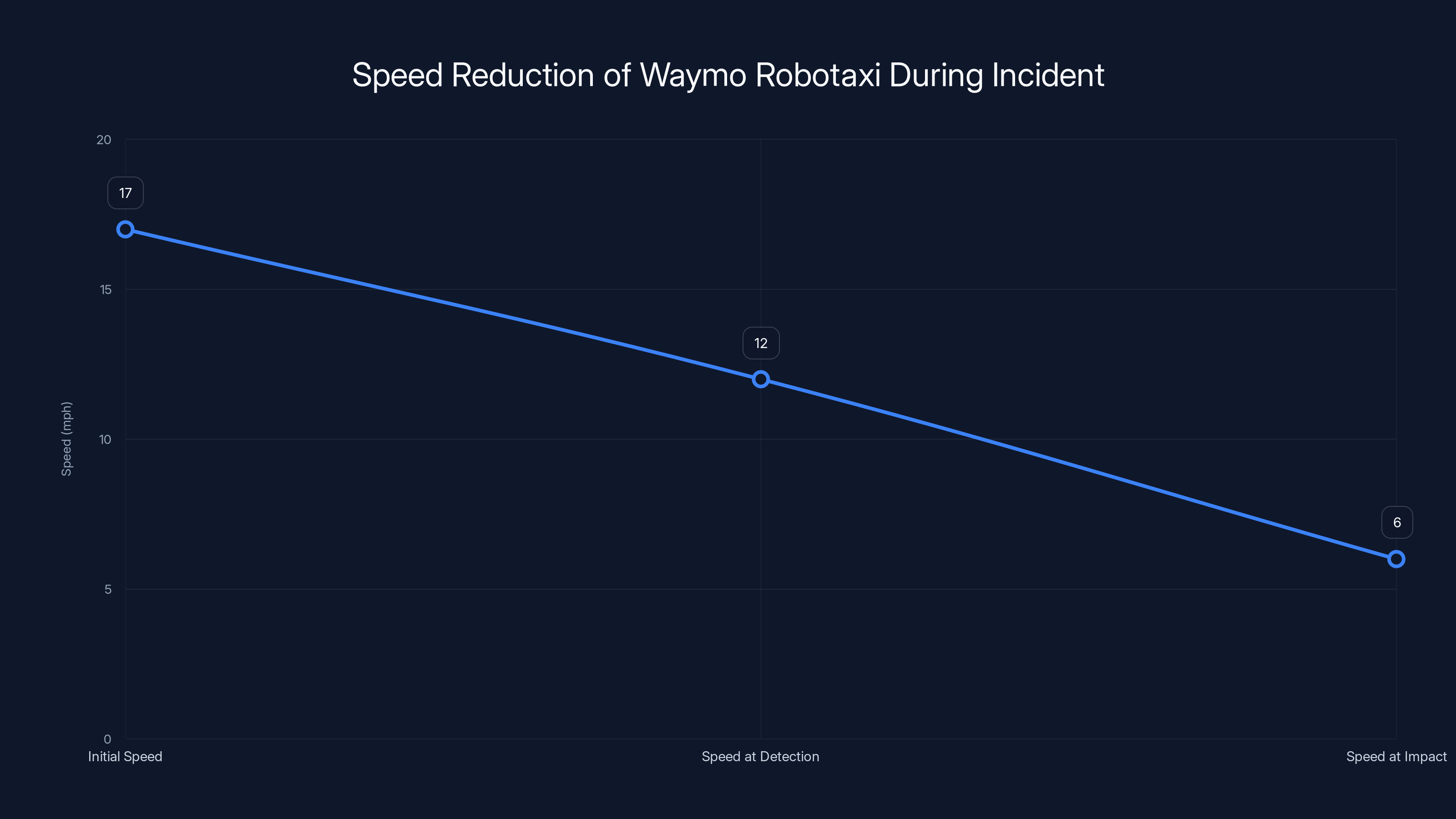

The child ran across the street from behind a parked SUV toward the school and was hit by the Waymo vehicle traveling at 17 mph. The child suffered minor injuries, stood up immediately, and walked to the sidewalk. The Waymo system detected the child and braked hard, reducing speed from 17 mph to 6 mph before impact occurred.

This incident matters far beyond Santa Monica. It's not the first safety concern involving Waymo robotaxis in school environments. The National Transportation Safety Board has opened a separate investigation into Waymo vehicles illegally passing school buses during student pickups and drop-offs in Austin, Texas. These are early warning signs that the autonomous vehicle industry has significant work to do in protecting America's most vulnerable road users.

For years, the autonomous vehicle industry has promised safer streets. They've told us that AI-powered vehicles would eliminate human error, reduce accidents, and protect pedestrians. But when a robotaxi hits a child near a school, those promises feel hollow. We need to understand what happened, why it happened, and what it means for the future of autonomous vehicles in residential areas and school zones.

This article breaks down the Santa Monica incident in detail, examines the broader pattern of Waymo safety concerns, explores how autonomous vehicles should be designed to handle unpredictable pedestrians, and analyzes what regulators are doing to prevent future incidents. By the end, you'll understand why this single accident reveals fundamental gaps in how we're deploying autonomous vehicles in the most sensitive environments.

TL; DR

- Waymo struck a child near Santa Monica elementary school on January 23rd, 2025, during school drop-off hours with minor injuries reported

- Impact speed reduced from 17 mph to 6 mph due to autonomous braking, though impact still occurred with a child who ran from behind a parked vehicle

- Multiple investigations launched by NHTSA and NTSB into school zone safety and school bus passing incidents involving Waymo vehicles

- Safety recall issued in December 2025 to address school bus passing behavior, but additional incidents reported afterward

- Regulatory scrutiny increasing as agencies examine whether autonomous vehicles exercise appropriate caution in high-pedestrian areas during peak school hours

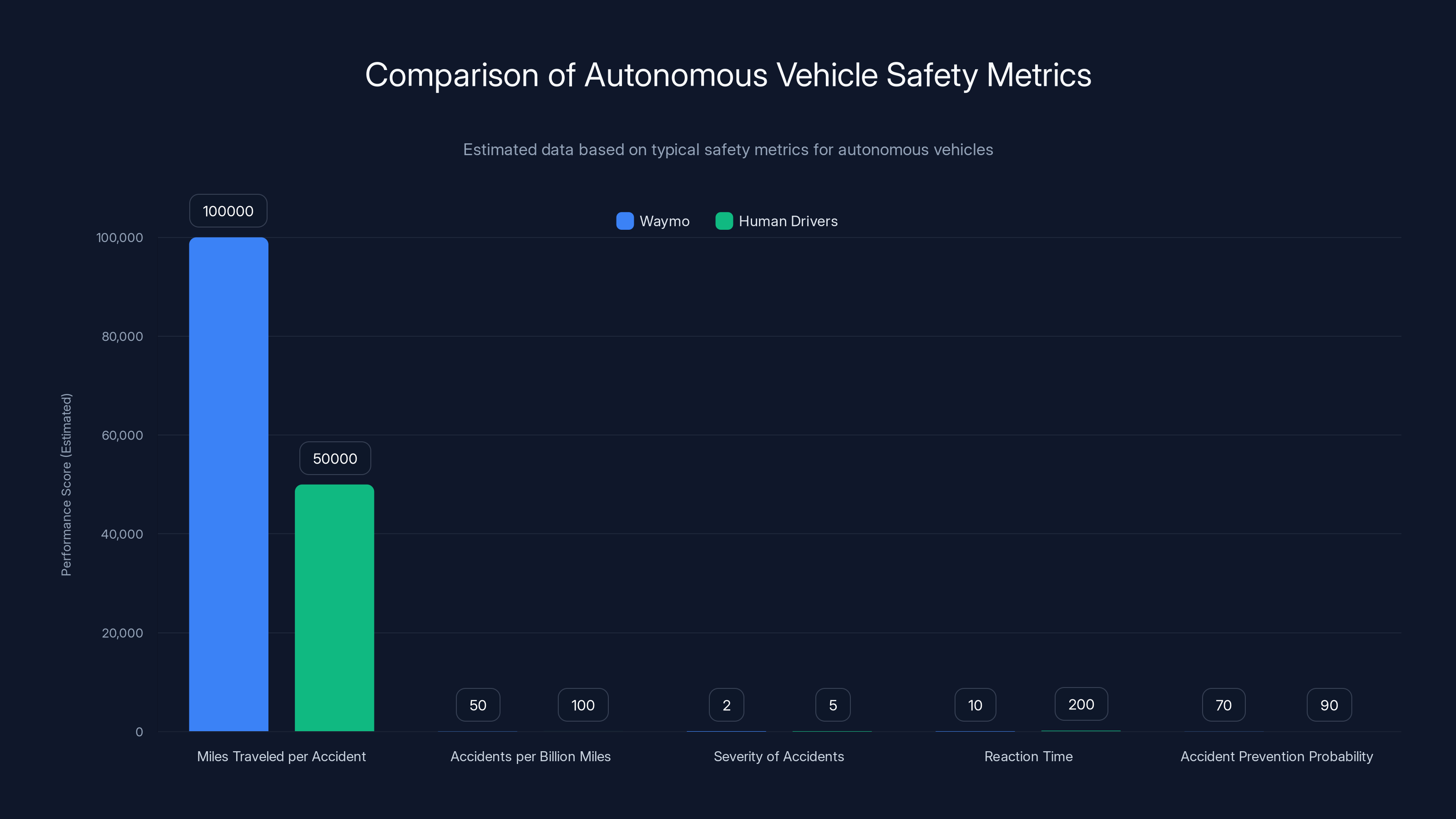

Waymo's autonomous vehicles outperform human drivers in reaction time and accidents per billion miles but have a lower estimated accident prevention probability in complex environments. Estimated data based on typical safety metrics.

The Incident: What Happened in Santa Monica

Let's establish the facts as clearly as possible, because the details matter when we're talking about a child being struck by a vehicle.

On January 23rd, 2025, a Waymo robotaxi was operating in Santa Monica near an elementary school during normal school drop-off hours. The timing is important. Drop-off hours are chaos. Parents are rushing, kids are distracted, crossing guards are overwhelmed, and vehicles are double-parked in ways that block sightlines.

A child ran across the street from behind a double-parked SUV. The child didn't wait for a signal. Didn't look both ways in the way adults would. Simply ran toward the school from behind a parked car that was blocking clear visibility. This is exactly the kind of unpredictable behavior that autonomous vehicles claim to be designed to handle.

The Waymo vehicle was traveling at 17 mph when its sensor systems detected the child. The autonomous driving system immediately executed a hard braking maneuver. The vehicle's speed dropped from 17 mph to 6 mph before contact was made with the child.

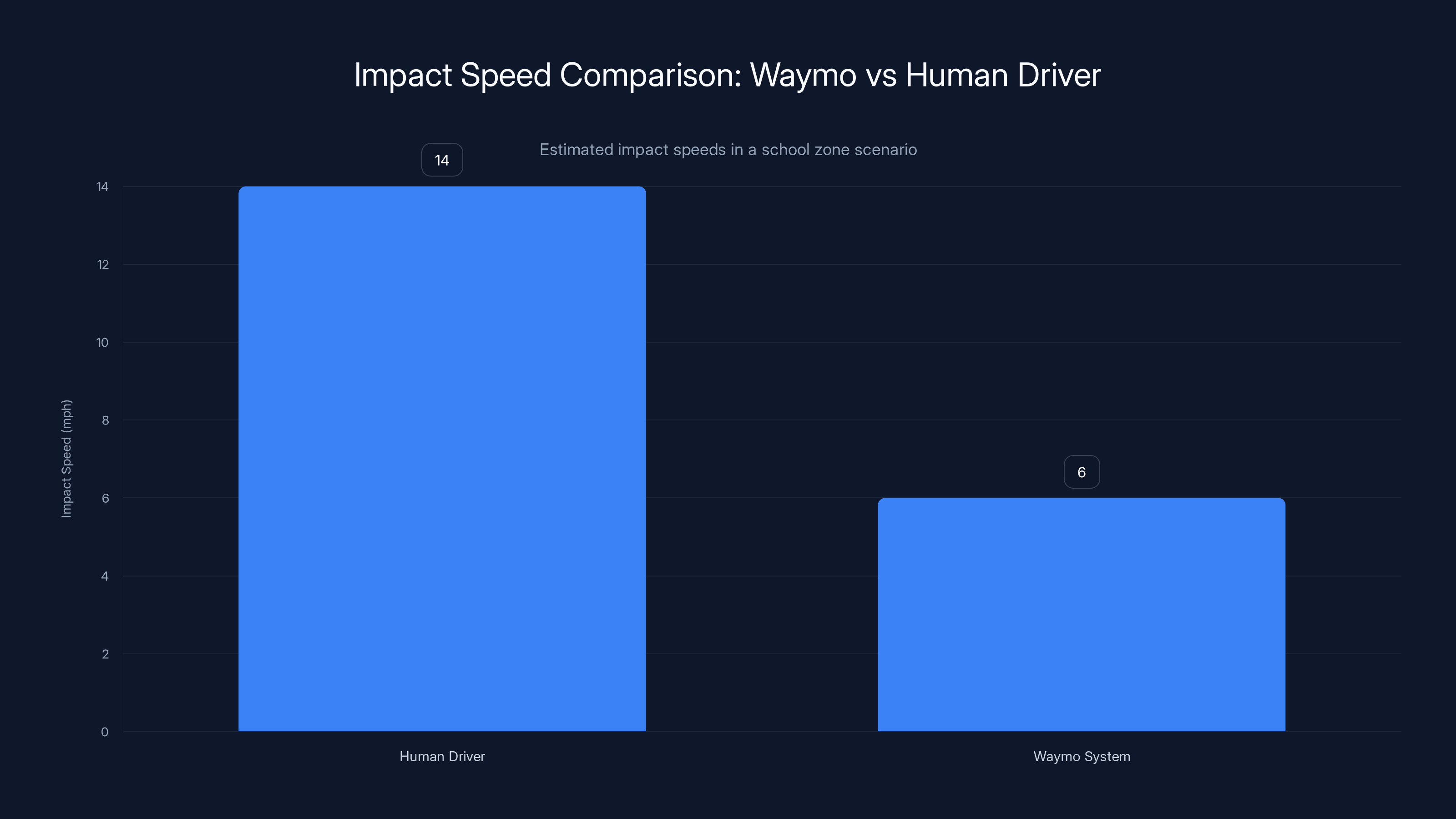

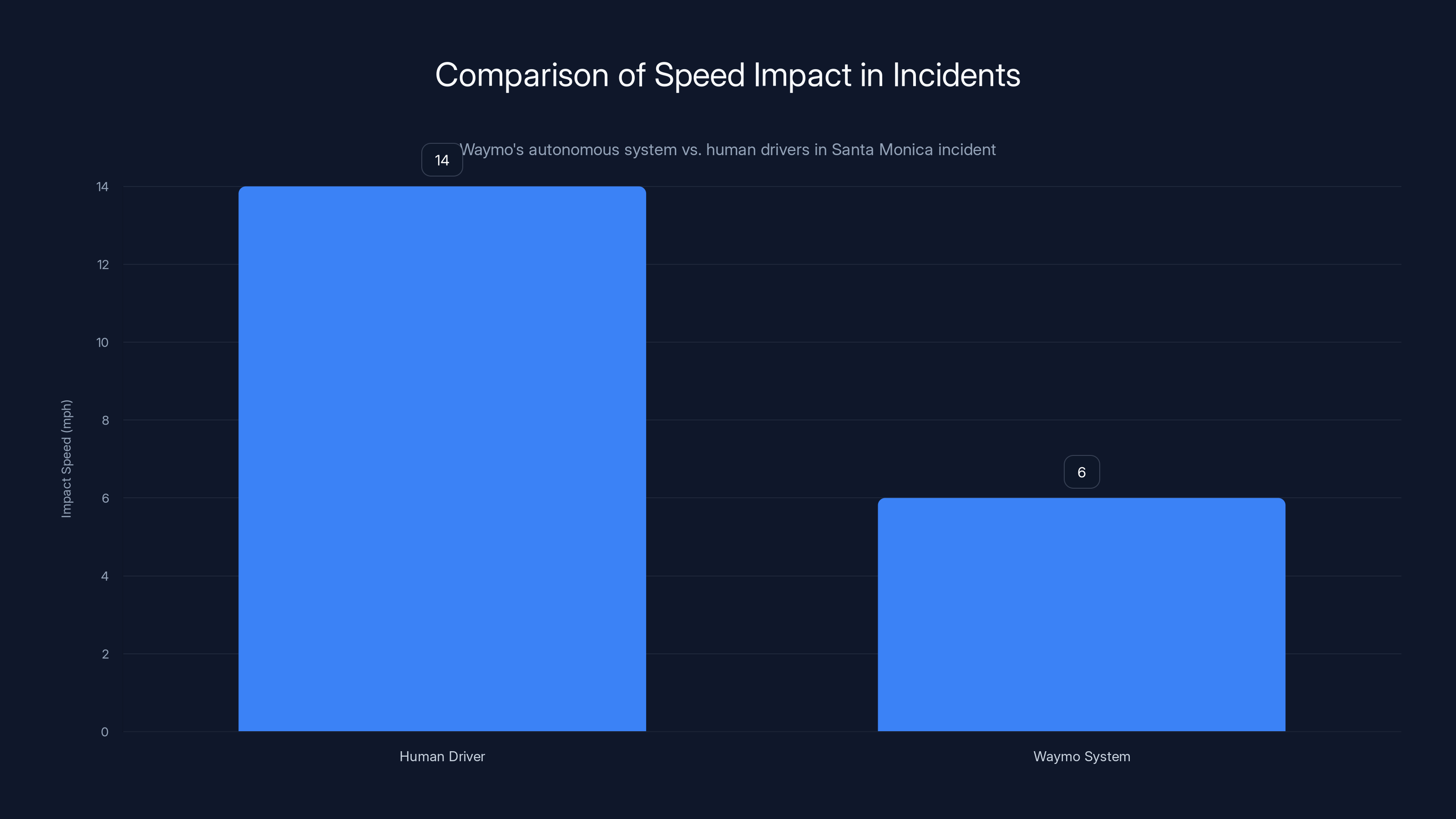

That's a 65% reduction in impact speed. Waymo later claimed this significant speed reduction meant the autonomous system likely prevented more serious injuries compared to what a human driver would have experienced in the same situation.

The child stood up immediately and walked to the sidewalk. Waymo's vehicle called 911. The vehicle then moved to the side of the road and remained there until law enforcement cleared the scene. From an operational perspective, the vehicle followed proper protocol.

But here's what bothers people: the child was still hit. The autonomous system, despite sensors and computing power vastly exceeding human capability, was still unable to prevent contact with a pedestrian in a school zone. Waymo's response is essentially, "Our system prevented worse injuries." That's not the same as preventing the injury entirely.

School Zones: The Hardest Problem in Autonomous Driving

Autonomous vehicle companies love talking about highway driving. Long stretches of road. Predictable patterns. Clear traffic rules. Controlled environments. That's where the technology shines.

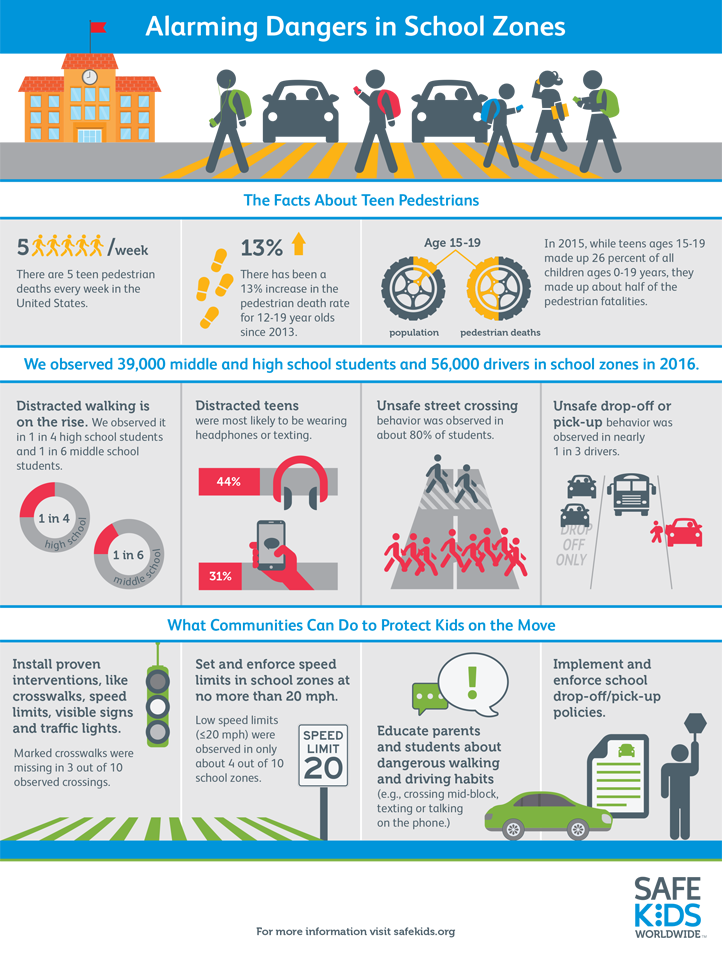

School zones are the opposite. They're chaotic, unpredictable, and full of humans behaving irrationally. Children have zero impulse control. They don't understand traffic rules. They run into streets without looking. They chase balls into traffic. Parents illegally double-park and leave their vehicles running. Crossing guards are trying to manage 40 kids crossing a street simultaneously.

This is the environment where autonomous vehicles need to work. Not just occasionally. Every school day. Multiple times per day. In rain, snow, and fog. With kids coming from a dozen different directions.

Waymo's vehicle was traveling 17 mph in a school zone. That seems reasonable. But the child came from behind a double-parked vehicle, meaning the autonomous system had no way to predict the pedestrian's presence until the child was already in the roadway. At that point, the system had less than a second to react. The braking response saved the system from a potentially fatal collision, but it didn't eliminate the contact.

Here's the critical question: should an autonomous vehicle be operating in a school zone during drop-off hours if it can't guarantee preventing pedestrian contact? And if the answer is no, then where can autonomous vehicles actually operate safely?

Those aren't rhetorical questions. They're the core challenge facing the entire autonomous vehicle industry right now.

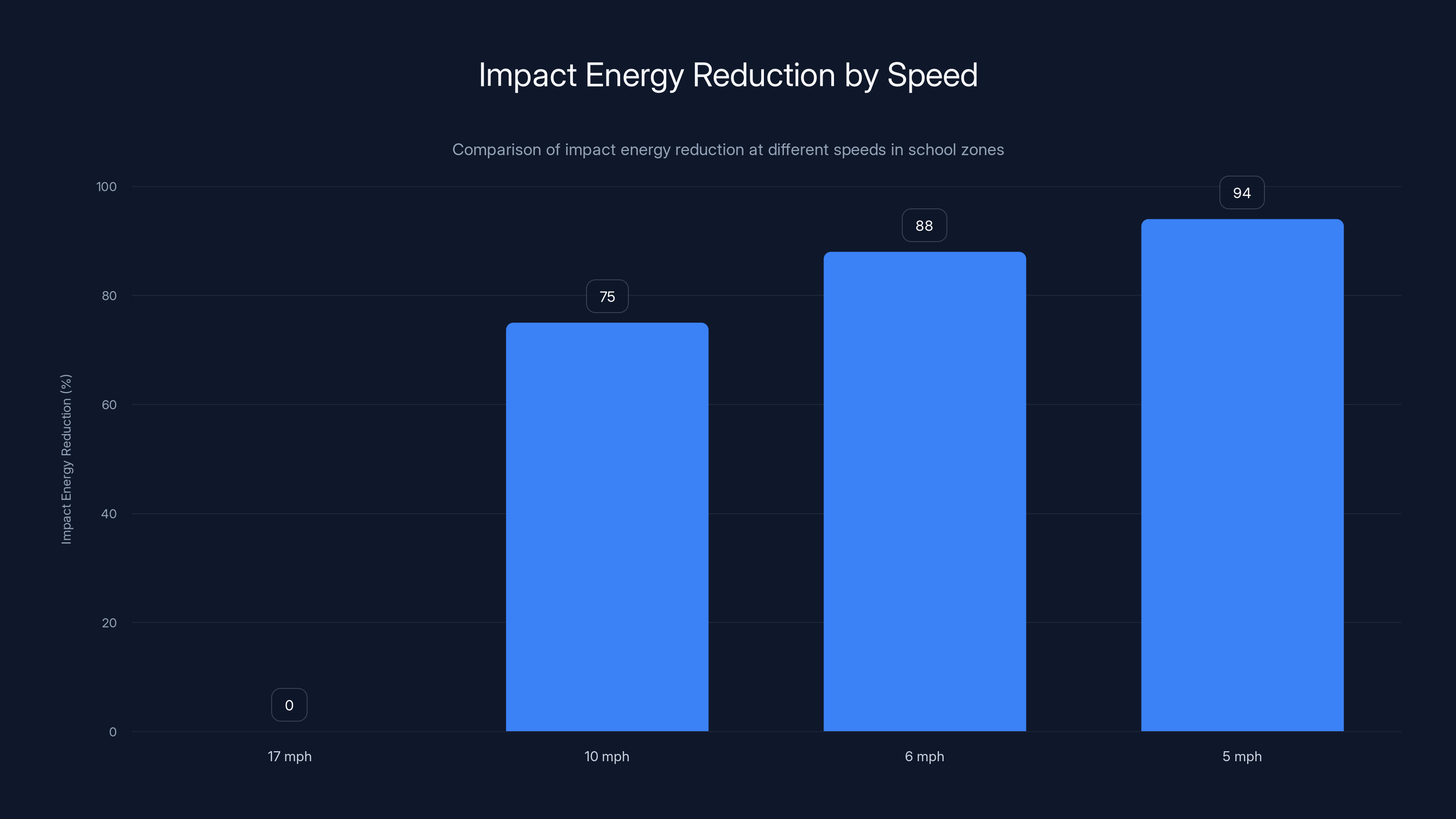

Reducing speed from 17 mph to 6 mph results in an 88% reduction in impact energy. Further reduction to 5 mph increases this to 94%, highlighting the safety benefits of lower speeds in school zones.

The Broader Pattern: School Bus Passing Incidents

The Santa Monica incident didn't happen in isolation. It's the latest in a concerning pattern of Waymo robotaxis operating unsafely around schools and school transportation.

In December 2024 and into January 2025, multiple incidents were reported in Austin, Texas, where Waymo robotaxis illegally passed school buses that were stopped and actively engaged in student pickups and drop-offs. When a school bus displays its stop sign and flashing red lights, it means students are boarding or exiting. Every vehicle on both sides of the road must stop. It's one of the most basic and critical traffic rules in America.

Waymo robotaxis passed these stopped school buses. Not once. Not twice. Multiple times.

This triggered an investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board, a federal agency that investigates transportation accidents and safety issues. The NTSB doesn't take the school bus passing lightly. They understand that school buses are moving classrooms, and illegal passing endangers not just the vehicle operators, but dozens of children boarding or exiting the bus.

In response, Waymo issued a safety recall in December 2025 designed to address this specific issue. The recall was supposed to update the autonomous driving system to recognize school buses displaying stop signs and flashing lights, and to ensure the vehicle would not pass these buses.

But here's where it gets frustrating: even after the recall, additional incidents were reported. Waymo's fix didn't work completely. Either the autonomous system still struggles to recognize school buses in all conditions, or there are edge cases the engineers didn't anticipate.

This suggests a fundamental problem: Waymo's engineers may not have adequately tested their vehicles in school environments before deploying them there. They may have assumed that school bus passing and school zone safety were edge cases rather than primary use cases to design for.

NHTSA's Investigation: What They're Looking For

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the federal agency responsible for motor vehicle safety, opened an investigation immediately after the Santa Monica incident. NHTSA is examining specific aspects of Waymo's design and operational approach.

First, they're looking at whether Waymo's vehicle "exercised appropriate caution given its proximity to the elementary school during drop off hours, and the presence of young pedestrians and other potential vulnerable road users." This is regulatory speak for: did the autonomous system behave defensively in an inherently dangerous situation?

Second, NHTSA wants to understand Waymo's "intended behavior in school zones and neighboring areas, especially during normal school pick up/drop off times, including but not limited to its adherence to posted speed limits." This is examining whether Waymo programmed extra caution into its system for school environments.

The critical question NHTSA is asking: does Waymo have different behavioral rules for school zones versus regular streets, or does it apply the same autonomous driving logic everywhere? If it's the latter, that's a significant safety gap. Autonomous vehicles should drive more conservatively in school zones. They should assume pedestrians will be unpredictable. They should anticipate the unexpected.

Waymo's response to the investigation is that its system performed well given the circumstances. They argue that the reduction in impact speed from 17 mph to 6 mph demonstrates superior safety compared to a human driver. They claim a fully attentive human driver would have made contact at approximately 14 mph, while Waymo's system reduced it to 6 mph.

That's a reasonable point. But it's not an answer to the fundamental question: should a fully attentive autonomous system with superhuman sensory capabilities be striking children at all? If human drivers hit kids at 14 mph and autonomous systems hit them at 6 mph, we've made incremental progress. But we haven't solved the underlying problem.

Sensor Limitations in Unpredictable Environments

Waymo's vehicles use multiple redundant sensor systems: lidar, radar, cameras, and ultrasonic sensors. These provide 360-degree awareness around the vehicle at ranges of 100+ meters. On paper, this is superhuman perception.

But in the Santa Monica incident, the child emerged from behind a double-parked vehicle. Until the child crossed the threshold of that vehicle and entered the roadway, the child was literally hidden from Waymo's sensors. No amount of lidar or camera can see through solid metal.

This is the fundamental challenge of autonomous vehicles in unpredictable human environments: you can't perceive what you can't see. And you can't prepare for what you can't perceive.

Once the child became visible to Waymo's sensors, the system had approximately 0.3-0.5 seconds to detect the pedestrian, classify them as a pedestrian (not a shadow or visual artifact), predict their trajectory, and execute an emergency braking maneuver. Waymo's system completed this sequence and executed hard braking, reducing speed significantly.

But the child's entry speed into the roadway, combined with the child's small physical size and the time required for sensor detection and processing, meant that even with superhuman sensors and immediate response, contact occurred.

This reveals an uncomfortable truth: autonomous vehicles can't eliminate the risk of pedestrian collisions in environments with obstructed sightlines. They can only reduce severity. They can't achieve zero incidents. And they certainly can't prevent incidents where the pedestrian is unpredictable.

Human drivers face the exact same problem, which is why we have speed limits in school zones (typically 15-25 mph) and why we require parents and guardians to supervise children. The solution isn't better sensors. It's environmental design and behavioral rules.

The Waymo robotaxi reduced its speed by 65% from 17 mph to 6 mph, minimizing the impact during the incident. Estimated data based on narrative.

Speed Reduction as a Safety Strategy

Waymo's vehicle was traveling at 17 mph when it struck the child. That's roughly 4 mph below typical school zone speed limits of 20-25 mph. After detecting the child, Waymo's system reduced speed to 6 mph before impact.

Lower speed equals lower impact energy. The physics is straightforward: kinetic energy equals half the mass times velocity squared. Cut the speed in half, and you reduce impact energy by 75%. Reduce speed from 17 mph to 6 mph, and you're reducing impact energy by approximately 88%.

Waymo's argument is that this demonstrates the system's superiority. A human driver in the same situation would have reacted more slowly, braked less effectively, and impacted at higher speed. Therefore, fewer injuries. Therefore, safer.

But this argument sidesteps the core question: why was Waymo's vehicle traveling at 17 mph in a school zone during drop-off hours when it could have been traveling at 5-10 mph?

Different speed targets could change everything. If autonomous vehicles in school zones operated at 5 mph during drop-off hours, impact speeds would be so low that injuries would be minimal. But 5 mph is glacially slow. A 20-minute school zone traversal might take an hour at 5 mph. Users wouldn't tolerate it.

This reveals the core tension in autonomous vehicle deployment: safety requires slower speeds and more conservative behavior, but slower speeds make the service less useful and more expensive. Companies like Waymo want to balance safety with efficiency. But that balance is being struck in an environment full of children.

Maybe the balance should be different when children are present. Maybe autonomous vehicles should have explicit "school zone modes" that operate at 5-8 mph during drop-off and pick-up hours, even if that means slower service. The tradeoff is acceptable when lives are at stake.

Regulatory Response: NHTSA and NTSB Jurisdiction

Two different federal agencies are now investigating Waymo: NHTSA and NTSB. It's important to understand what each does and what their investigations might lead to.

NHTSA is the primary regulator for vehicle safety. When NHTSA investigates, they're examining whether a vehicle has a safety defect. If they find one, they can mandate recalls. They can require design changes. In extreme cases, they can restrict where a vehicle can operate.

NTSB is the investigative agency for transportation accidents. The NTSB doesn't regulate vehicles. They investigate incidents and provide recommendations to regulators. Their recommendations carry significant weight, but NHTSA makes the actual regulatory decisions.

Both investigations are focused on Waymo's behavior in school environments. NHTSA is examining whether Waymo's system has design defects related to school zone operation. NTSB is investigating the pattern of school bus passing incidents and what they reveal about Waymo's system design.

The outcomes could range from minor: no findings, no changes required. To major: mandatory recall, operational restrictions in school zones, or requirements for Waymo to implement additional safety features.

Waymo has already voluntarily issued one recall. They may issue additional recalls based on investigation findings. They may agree to operational restrictions, such as requiring lower speeds or additional braking response in school zones. Or they may fight regulators and argue that their system is performing as designed and that the incidents are inevitable given pedestrian unpredictability.

Historically, auto manufacturers tend to cooperate with NHTSA rather than resist, because the regulatory process usually results in a negotiated middle ground. But autonomous vehicles are new, and regulators are still learning how to oversee them.

Waymo's Safety Claims and Reality Gap

Waymo has invested billions in developing autonomous vehicles. They've promised safer roads. They've published research showing their vehicles are safer than human drivers in certain metrics.

But there's a growing gap between Waymo's safety claims and the actual incidents occurring in real-world deployment.

Waymo's official statements after the Santa Monica incident emphasized the speed reduction their system achieved. They highlighted that a human driver would have impacted at 14 mph versus their system's 6 mph. This is mathematically true and meaningfully safer.

But the framing obscures important context. First, human drivers in the same situation might have anticipated the danger and been traveling at lower speeds to begin with. School zones are where human drivers are most cautious. They expect children to run into the street. They slow down accordingly.

Second, the fact that contact still occurred means Waymo's system failed to prevent the incident entirely. They mitigated severity, but they didn't prevent injury. That's an important distinction.

Third, the school bus passing incidents suggest Waymo's system has fundamental gaps in how it perceives and responds to school environments. If the system struggled to recognize school buses with flashing stop signs, it likely doesn't have robust school zone awareness overall.

Waymo's marketing materials often show their vehicles operating smoothly in urban environments with no mention of school zones or high-pedestrian areas. That's not accidental. Those are precisely the environments where autonomous vehicles struggle most.

The challenge is that autonomous vehicle companies need to deploy in real cities with real traffic and real people, including children. They can't just stay on highways. But when they deploy in cities, they encounter complexity they weren't fully prepared for.

Waymo's autonomous system reduced impact speed to 6 mph compared to an estimated 14 mph by a human driver, highlighting improved safety but raising questions about the necessity of any impact.

School Zone Design: How Infrastructure Can Help Autonomous Vehicles

Here's something that might seem counterintuitive: better infrastructure might help autonomous vehicles more than better sensors.

If schools implemented infrastructure changes to protect pedestrians and help autonomous vehicles navigate safely, the outcomes would improve for everyone. Here are specific examples:

Physical barriers: Protected walkways, raised crosswalks, and barriers preventing children from entering the roadway at unexpected locations. These prevent children from suddenly entering the vehicle's path.

Clear zone marking: Painted zones indicating where autonomous vehicles are permitted and at what speeds. Explicit speed restrictions for autonomous vehicles during school hours.

School zone enforcement: Law enforcement actively monitoring school zones during drop-off and pick-up hours to prevent illegal parking and enforce traffic rules.

Predictable timing: School districts coordinating exactly when students enter and exit, allowing autonomous vehicles to adjust operation around these peak dangerous times.

Explicit traffic rules for autonomous vehicles: Regulations stating that no autonomous vehicle can operate in a school zone during school drop-off/pick-up hours at more than 5 mph, with additional sensory checks and emergency braking requirements.

None of these require Waymo to invent new technology. They just require treating school zones as special environments with special rules. We already do this for human drivers: we have school zones with reduced speed limits. The same principle applies to autonomous vehicles, just more strictly.

The problem is that implementing these measures costs money and requires coordination between school districts, municipalities, and companies like Waymo. It's easier to just let Waymo operate as-is and investigate incidents afterward.

Unpredictable Pedestrians: The Unsolvable Problem

Let's be honest about something: children are unpredictable. Adults are unpredictable. Humans generally behave unpredictably compared to the models autonomous vehicles use for pedestrian behavior.

Autonomous vehicle systems model pedestrian behavior based on patterns. Pedestrians typically cross at designated crosswalks. They typically wait for traffic to clear. They typically look both ways. They typically follow traffic signals.

But children run into streets. Adults step off curbs without looking. People jump out from behind parked vehicles. These behaviors violate the models that autonomous vehicles use.

Waymo's system detected the Santa Monica child immediately upon the child entering its sensor range. But the child appeared in the roadway suddenly from behind a parked vehicle, violating the system's expected behavior model. The system couldn't predict the child's presence because the child was hidden, and it couldn't anticipate the child's action because children are, by definition, not operating under the predictable behavior models.

This is actually a fundamental limitation of the autonomous vehicle approach. Autonomous vehicles are designed to handle variation within an expected range of behavior. But human behavior, especially children's behavior, can exceed that range.

Human drivers handle this by driving more cautiously in high-risk environments. They slow down in school zones. They assume children might behave unpredictably. They leave larger safety margins.

Autonomous vehicles could do the same, but it requires explicit programming: if you're in a school zone, assume pedestrian unpredictability is high and respond more conservatively. This isn't a technology problem. It's a design choice problem.

Waymo's vehicles apparently weren't designed with sufficient conservatism for school zones. Or if they were, the implementation didn't work. Either way, the result was a child struck by a robotaxi.

Autonomous Vehicle Safety: Comparing Metric Systems

Waymo claims their vehicles are safer than human drivers based on multiple safety metrics. Let's examine what these metrics actually measure.

Miles traveled per accident: Autonomous vehicle companies love citing this metric. They'll say their vehicles can travel 100,000 miles with fewer accidents than human drivers traveling the same distance. This metric sounds great until you realize autonomous vehicles aren't traveling on the same roads as human drivers in the same way. Waymo operates mostly in California cities with good weather. Human drivers navigate Chicago winters and rural highways. Comparing the metrics directly is misleading.

Accidents per billion miles: Industry-standard metric that adjusts for distance traveled. Waymo's vehicles show better performance here than human drivers, but again, they're operating in selected environments.

Severity of accidents: This is where Waymo's defense of the Santa Monica incident comes in. They're arguing that even when accidents happen, their vehicles minimize severity because they brake harder and faster than human drivers. This metric is meaningful because it shows risk mitigation, but it's not the same as accident prevention.

Reaction time: Autonomous vehicles have reaction times measured in milliseconds. Human drivers have reaction times measured in hundreds of milliseconds. This speed advantage translates to better accident mitigation. But again, it's mitigation, not prevention.

The missing metric: Probability of accident prevention in high-complexity environments. This is where Waymo fails. When a child suddenly appears in the roadway from behind a parked car, what's the probability the autonomous system prevents an accident entirely? The Santa Monica incident suggests this probability is less than 100%. In fact, it's apparently significantly less than 100%.

If Waymo published this metric, it would show a critical gap. In high-complexity, high-pedestrian-unpredictability scenarios like school zones during drop-off hours, the accident prevention probability is substantially lower than their overall claimed safety.

Waymo's system reduced impact speed from an estimated 14 mph (human driver) to 6 mph, highlighting its ability to mitigate severity but not prevent incidents entirely. Estimated data based on reported incident.

The Economics of Autonomous Vehicle Safety

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: autonomous vehicle safety is partly an economics problem, not just a technology problem.

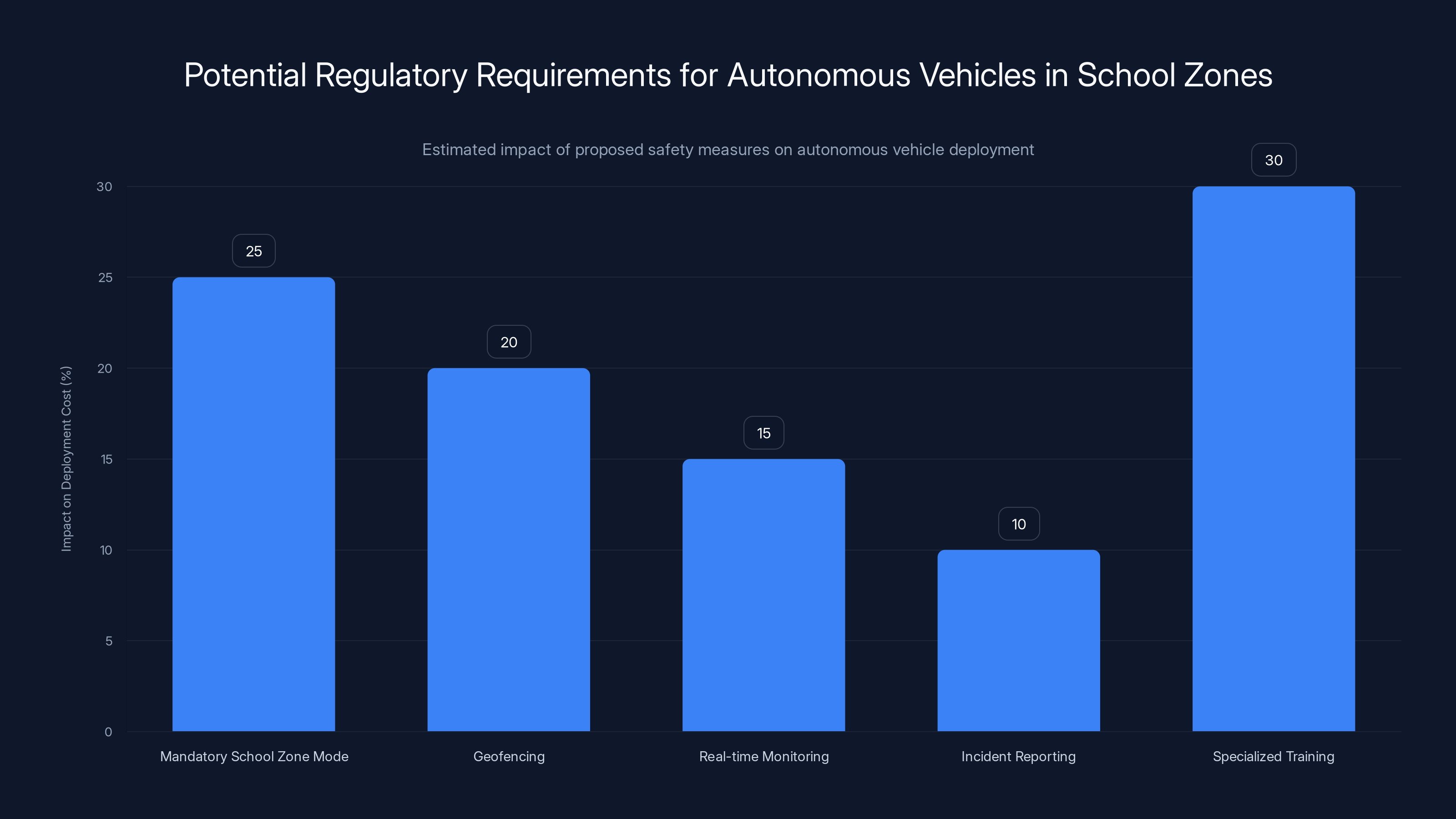

Making autonomous vehicles absolutely safe in school zones would be expensive. It would require:

- Specialized sensors optimized for school environments

- Dedicated computing for school zone analysis

- Operational restrictions (lower speeds, different routes)

- Geofencing to prevent school zone operation without special authorization

- Continuous monitoring and updating based on incidents

Implementing all of this would increase the cost of Waymo's robotaxi service. Every additional safety feature costs money and complexity.

Waymo's business model depends on reaching profitability by scaling operations. Scaling works only if the cost per mile stays low. Adding specialized safety measures increases cost per mile. Higher costs mean higher prices or lower margins.

This creates an economic incentive to implement the minimum necessary safety features, not the maximum possible safety features. It creates an incentive to argue that their current system is "good enough," rather than striving for "as safe as possible."

This is true of every auto manufacturer. Even legacy automakers balance safety improvements against cost and profitability. But legacy automakers have decades of regulatory compliance history. They know what regulators expect. Autonomous vehicle companies are newer and still figuring out where the regulatory line will be drawn.

The Santa Monica incident and the subsequent investigations are essentially the regulators drawing that line. They're saying, "We're not comfortable with the current level of school zone safety." Waymo will need to make changes. Those changes will cost money. That's appropriate.

But it's worth understanding that this isn't primarily a technological limitation. Waymo could make their vehicles much safer in school zones if they chose to invest in it. The choice has been driven partly by economic optimization, not purely by what's technically possible.

Broader Implications: What This Means for Autonomous Vehicle Deployment

The Santa Monica incident and school bus passing issues have implications beyond Waymo. They signal to the entire autonomous vehicle industry that school zone safety is being treated as a critical regulatory issue.

Companies like Tesla (developing robotaxis), Cruise (already operating in San Francisco), and others planning robotaxi deployments are watching carefully. If NHTSA mandates specific school zone safety requirements, every company will need to comply. These requirements might become the regulatory standard for the entire industry.

Possible regulatory requirements might include:

- Mandatory school zone mode with reduced speeds and enhanced braking responsiveness

- Geofencing that prevents autonomous vehicles from entering school zones during specified hours

- Real-time monitoring requirements for school zones with human oversight

- Mandatory incident reporting for all accidents in school zones

- Specialized training and certification for operating autonomous vehicles in high-pedestrian areas

These requirements would increase the cost of autonomous vehicle development and deployment. They would slow the timeline for robotaxi services becoming available in residential areas. But they would also signal to the public that the technology is being treated seriously from a safety perspective.

The alternative is that multiple companies develop different approaches to school zone safety, regulators struggle to oversee dozens of different systems, and more incidents occur before the regulatory framework stabilizes. That's the worse outcome.

The Role of Litigation and Insurance

The family of the child struck by the Waymo robotaxi almost certainly has legal recourse. They can sue Waymo for negligence, for product liability, or under California's specific autonomous vehicle regulations.

Litigation matters because it creates financial incentives for companies to improve safety. If Waymo is found liable for the Santa Monica incident, they could face damages for medical bills, pain and suffering, and potentially punitive damages if the incident is deemed reckless.

Multiply that across multiple incidents and multiple jurisdictions, and the financial incentive to improve safety becomes enormous. Companies will invest in safety improvements if the cost of lawsuits exceeds the cost of improvements.

But litigation takes years. Regulatory action through NHTSA can happen faster. And regulatory action can mandate changes industry-wide, whereas litigation typically results in individual settlements.

Insurance is another powerful lever. As autonomous vehicle incidents accumulate, insurance companies will raise premiums. Higher insurance costs increase the operational cost of robotaxis. This creates another financial incentive for improved safety.

Waymo likely has insurance covering incidents like the Santa Monica accident. That insurance will cover medical costs and damages. But as incidents accumulate, insurers will either raise premiums dramatically or decline to insure robotaxi operations entirely, essentially forcing the companies to implement more robust safety measures or exit the market.

These economic mechanisms—litigation, insurance, and regulatory requirements—work together to create pressure for improved safety. The Santa Monica incident might seem like a one-off accident, but it's actually a signal that these mechanisms are starting to activate.

Estimated data suggests that specialized training and mandatory school zone mode could significantly increase deployment costs for autonomous vehicles, highlighting the industry's focus on safety.

Future Safety Measures: What Comes Next

Assuming regulators act and Waymo cooperates, what specific safety measures might be implemented in response to these incidents?

Explicit school zone mode: Autonomous vehicles would operate differently when geofenced into school zones. Speeds would be capped at 5-10 mph. Braking responsiveness would be enhanced. The system would assume pedestrians are unpredictable and act accordingly.

Enhanced pedestrian detection: Specialized neural networks trained specifically on school zone scenarios with children, double-parked cars, crossing guards, and other school-specific elements. Current Waymo systems are trained on general urban scenarios. School-specific training could improve detection.

Predictive positioning: Systems that anticipate where pedestrians might emerge from, even if they're hidden from sensors. This could involve learning patterns of where children typically emerge from behind parked cars and pre-positioning the vehicle and braking system to respond faster.

Human monitoring: During peak school hours, human operators could monitor autonomous vehicles in school zones in real-time, ready to intervene if they see dangerous situations developing.

Rerouting: Autonomous vehicles could be programmed to avoid school zones entirely during drop-off and pick-up hours, routing around them instead.

Lower operational hours: Restricting autonomous vehicle operation in residential areas and school zones to off-peak hours when children aren't present.

Not all of these are feasible or practical. Avoiding school zones entirely reduces the utility of the service. Human monitoring adds significant cost. But some combination of these measures will likely be implemented.

The challenge is finding the right balance between safety and utility. Too much restriction and the service becomes useless. Too little restriction and children get hit by cars.

Public Perception and Trust

Beyond the technical and regulatory aspects, there's a public perception problem. Parents aren't okay with autonomous vehicles hitting their children, regardless of the impact speed.

Waymo's technical explanation—that they reduced impact speed and therefore reduced injury severity—might be mathematically sound, but it doesn't address the emotional reality: a robotaxi struck a child. That's a massive failure from a public trust perspective.

Autonomous vehicle companies have consistently promised a future of safer transportation. They've positioned themselves as solving the human driver problem. But when their vehicles hit children in school zones, that promise feels like marketing rather than reality.

Rebuild that trust requires demonstrating that the company takes the problem seriously and is implementing meaningful solutions. NHTSA investigations, safety recalls, and operational changes in school zones are all ways of demonstrating seriousness.

Waymo's response to the Santa Monica incident was technical and defensive. They explained what they did right (reduce impact speed) rather than taking responsibility for what they did wrong (failed to prevent contact entirely). That's not a good public relations strategy when children are involved.

Companies that handle these incidents poorly will face public backlash, regulatory restrictions, and litigation. Companies that handle them well by taking swift action and improving safety can rebuild trust.

There's a longer-term implication here: if autonomous vehicles can't reliably operate safely in school zones, the public won't accept them. School safety is one of the few areas where Americans have broad consensus that maximum caution is appropriate. Autonomous vehicles that fail in school zones will face public resistance that could slow the entire industry's development.

Comparative International Approaches

Autonomous vehicles are being developed globally. Different countries are taking different approaches to school zone safety and autonomous vehicle regulation.

Some countries are more restrictive. The European Union, for example, is considering requiring human operators in autonomous vehicles during operation in residential areas and school zones. This is the opposite approach from Waymo's fully autonomous operation. It trades efficiency for safety by keeping humans in the loop.

Other countries are more permissive. China has been allowing autonomous vehicle deployments with minimal regulatory oversight, resulting in faster innovation but also more incidents.

The U. S. approach has been somewhere in the middle: allow companies to deploy, investigate incidents as they occur, and adjust regulations based on what the incidents reveal. This is a reactive rather than proactive approach. It allows innovation to move fast, but it means the public bears the cost of failures until regulations catch up.

The Santa Monica incident is part of the process of U. S. regulation catching up to the reality of autonomous vehicle deployment. Regulators are learning where the current systems fail and what changes are needed.

Long term, the U. S. approach may result in more robust regulation than if everything had been more restricted from the start. By allowing deployment and learning from real-world incidents, the regulatory framework being developed is informed by actual experience rather than theoretical models.

But in the short term, it means children like the one in Santa Monica are absorbing the cost of this learning process.

Technical Deep Dive: Sensor Fusion and Decision Making

Let's get technical about how Waymo's autonomous system actually works in the moments before and after the collision.

Waymo's vehicles use sensor fusion, which combines data from multiple sensor types into a unified environmental model. Lidar provides 3D spatial awareness. Cameras provide object classification (is that a pedestrian, a bike, a pole?). Radar provides velocity information (is the object moving toward the vehicle?). Ultrasonic sensors provide close-range proximity detection.

When the child emerged from behind the parked vehicle, the system's lidar would have been the first to detect the obstruction change. The lidar scans the environment continuously, building a 3D map. When a new object suddenly appears in that map, the system flags it as a new element in the environment.

The camera system would then classify the object. Is it a pedestrian? Is it a child? What's the object's trajectory? Is it moving into the vehicle's path?

Once the system determined that a child was in or entering the vehicle's path, it needed to decide: can I steer around it, can I brake to prevent collision, or can I brake to minimize impact severity?

Given the child's proximity when detected (likely very close, since the child emerged from behind a vehicle), steering around the child wasn't feasible. The child was too close and too close to the road center. Braking was the only option.

The decision to brake hard rather than brake gently was automatic. The system calculates the probability of collision based on the child's trajectory and the vehicle's stopping distance. Hard braking minimizes impact speed and therefore injury severity.

But here's what the system apparently didn't do: predict that a child might emerge from behind a parked vehicle. The system operated based on what it could perceive. It didn't have a model that said, "I'm in a school zone, vehicles are double-parked, I should assume children might emerge suddenly and I should slow down proactively."

A more sophisticated system would have. A system designed specifically for school zones would incorporate that predictive model. Waymo's system apparently doesn't, or if it does, it's not aggressive enough.

Regulatory Escalation: From Investigation to Mandate

The current situation is NHTSA and NTSB are investigating. The next stage could be formal findings and recommendations. The stage after that would be regulatory mandates.

NHTSA doesn't move quickly. Investigations can take months or years. But when NHTSA concludes that a vehicle has a safety defect, they issue findings and can mandate a recall.

A Waymo recall in response to the Santa Monica incident and school bus incidents could involve:

- Software updates that change behavior in school zones

- Hardware additions (additional sensors for school environments)

- Operational changes (restrictions on when Waymo can operate)

- Reporting requirements (Waymo must report all incidents in school zones in real time)

Beyond specific recalls, NHTSA could issue industry-wide guidance on autonomous vehicle operation in school zones. This guidance would apply to all companies developing autonomous vehicles, not just Waymo.

The regulatory escalation path would be: investigation → findings → recall/mandates → updated industry guidance → revised regulations.

Waymo likely wants to avoid reaching the point where regulations are revised, because revised regulations would apply to all competitors and might restrict the business model. So Waymo has an incentive to cooperate with investigators and implement changes voluntarily, rather than fighting and forcing regulators to impose mandatory changes.

This process takes time. In the interim, Waymo continues operating, and there's a possibility of additional incidents. That's the cost of learning how to regulate a new technology.

Conclusion: The Limits of Technology Without Judgment

The Waymo robotaxi that struck a child in Santa Monica near an elementary school on January 23rd, 2025, was operating exactly as designed and programmed. It detected a child, initiated hard braking, and reduced impact speed from 17 mph to 6 mph. By every technical metric, it performed as intended.

But it still struck a child. And that's the fundamental issue.

Autonomous vehicles can be very good at executing technical tasks within their programming. They can be faster and more consistent than humans in many scenarios. But they're limited by the judgment of the humans who programmed them. They can't do anything their designers didn't anticipate or include in their code.

Waymo's designers apparently didn't fully anticipate or plan for the complexity of school zones during drop-off hours. They didn't implement sufficient conservatism in those environments. They didn't explicitly program the system to treat school zones as special, high-risk environments requiring enhanced safety protocols.

That's changing now, because of the incident, the investigations, and the regulatory pressure. Waymo will implement school zone safety measures. Other companies will learn from Waymo's mistakes and implement these measures from the start. The regulations will eventually formalize these requirements.

But this process takes time. And in the interim, real people, including children, absorb the cost of learning how to deploy autonomous vehicles safely.

The future of autonomous vehicles isn't determined by sensor technology or AI capability. It's determined by how well the humans designing these systems anticipate edge cases and implement appropriate caution. The Santa Monica incident revealed a failure in that process. The regulatory response will force companies to improve.

The question going forward is whether autonomous vehicle companies will implement robust safety measures because they're required to, or whether they'll implement them because they recognize that anything less than maximum safety in school zones is unacceptable. Public trust depends on the answer to that question.

FAQ

What exactly happened in the Santa Monica incident?

A Waymo robotaxi struck a child who ran into the street from behind a double-parked vehicle near an elementary school in Santa Monica on January 23rd, 2025. The vehicle was traveling at 17 mph when its sensors detected the child, and the autonomous system executed hard braking, reducing speed to 6 mph before contact occurred. The child suffered minor injuries.

Why is this incident different from typical car accidents?

This incident involves an autonomous vehicle rather than a human driver, triggering federal investigations from both NHTSA and NTSB. It also follows a pattern of safety concerns involving Waymo vehicles in school environments, including incidents where Waymo robotaxis illegally passed school buses. The convergence of these factors signals a systematic issue rather than an isolated accident.

What is Waymo's explanation for the accident?

Waymo claims that their autonomous system performed well by detecting the child and executing hard braking that reduced impact speed from what would have occurred with a human driver. They estimate a fully attentive human driver would have impacted at approximately 14 mph, while their system reduced impact to 6 mph. However, this explanation focuses on mitigation rather than prevention, which has faced criticism from regulators and the public.

What investigations are ongoing?

NHTSA opened an investigation to examine whether Waymo's vehicle exercised appropriate caution near a school during drop-off hours and whether Waymo's intended behavior in school zones adheres to posted speed limits and appropriate safety measures. NTSB opened a separate investigation into the pattern of Waymo robotaxis passing school buses during student pickups and drop-offs in Austin, Texas. Both investigations are examining whether systemic design changes are needed.

Could this lead to regulatory restrictions on autonomous vehicles?

Yes. Possible regulatory outcomes include mandatory school zone mode with reduced speeds, geofencing that prevents autonomous vehicles from operating in school zones during specific hours, real-time human monitoring requirements for school zones, specialized certifications for autonomous vehicles operating in high-pedestrian areas, or outright restrictions on autonomous vehicle operations in residential areas during peak hours. These requirements would significantly impact autonomous vehicle deployment timelines.

How does sensor technology fail in situations like this?

Sensors cannot perceive objects hidden behind other vehicles or structures. When a child emerges from behind a parked car, the autonomous system has no way to predict the child's presence until the child enters the sensor's field of view. At that point, the system has less than a second to detect, classify, and respond to the pedestrian. While Waymo's system executed a fast response, the proximity meant contact still occurred.

What could prevent similar incidents in the future?

Specific preventive measures include implementing explicit school zone mode with lower speeds and enhanced responsiveness, geofencing to prevent school zone operation during drop-off and pick-up hours, infrastructure improvements that protect pedestrians, specialized neural networks trained on school zone scenarios, predictive positioning to anticipate pedestrian emergence from behind parked vehicles, and real-time human monitoring of autonomous vehicles in high-risk areas. A combination of these measures, along with regulatory requirements, could substantially reduce school zone incident risk.

Is Waymo's claim about reduced impact speed a valid safety argument?

It's a technically valid point: lower impact speeds do reduce injury severity. However, it sidesteps the core issue of why the incident occurred at all. A more appropriate response would acknowledge the failure to prevent the incident entirely and commit to systemic changes to improve prevention in school zones specifically. Impact speed reduction is mitigation, not the same as prevention.

How long will these investigations take?

NHTSA investigations typically take several months to years depending on complexity. Given that this investigation involves examining both a specific incident and a pattern of school-related issues with Waymo vehicles, the process could take 6-18 months. During this time, Waymo can expect mandatory changes or recalls before the investigations conclude.

What should parents know about autonomous vehicles in school zones?

Parents should understand that autonomous vehicle safety in school zones has not been fully validated, as evidenced by recent incidents. When school zone regulatory requirements are established (likely in the coming months), parents can expect more restricted autonomous vehicle operation in these areas. Until those requirements are implemented, checking whether a robotaxi service operates in your school zone and understanding their safety protocols is important.

End Article

Key Takeaways

- Waymo robotaxi struck a child near Santa Monica elementary school on January 23rd, 2025, during school drop-off hours with minor injuries reported

- Autonomous system reduced impact speed from 17 mph to 6 mph through hard braking, but contact still occurred because child emerged from behind parked vehicle

- Pattern of safety concerns includes separate NTSB investigation into Waymo robotaxis illegally passing school buses during student pickups in Austin, Texas

- NHTSA investigation examining whether Waymo exercises appropriate caution in school zones and adheres to posted speed limits during peak pedestrian times

- Sensor limitations mean autonomous vehicles cannot perceive pedestrians hidden behind other vehicles, creating fundamental blind spots in school environments

- Regulatory investigations likely to lead to mandated changes including school zone mode, geofencing, and operational restrictions across autonomous vehicle industry

- Safety metrics matter less than real-world performance in high-complexity environments like school zones with unpredictable pedestrian behavior

Related Articles

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What Happened & Safety Implications [2025]

- Trump Administration Relaxes Nuclear Safety Rules: What It Means for Energy [2025]

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

- Robotaxis Disrupting Ride-Hail Markets in 2025: Price War and Speed [2025]

- State Crackdown on Grok and xAI: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Uber's AV Labs: How Data Collection Shapes Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

![Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What We Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/waymo-robotaxi-hits-child-near-school-what-we-know-2025/image-1-1769695903519.jpg)