The Copper Crisis Nobody's Talking About Yet

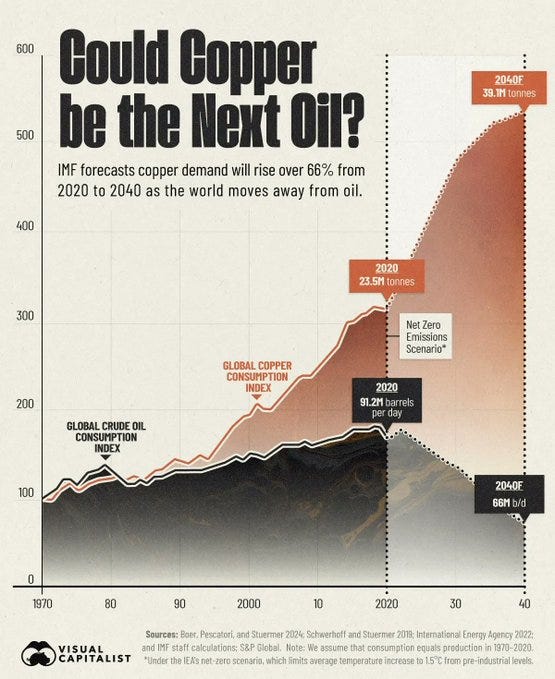

You've probably heard about chip shortages. You've definitely heard about RAM. But there's a supply chain problem brewing that's arguably more serious than either of those, and it's barely making headlines outside industry circles.

Copper is about to become the commodity equivalent of that one person at a party who everyone wants to talk to but nobody can find. And the shortage could reshape everything from how we build electric vehicles to whether we can actually power all these data centers everyone's betting the farm on.

Here's the thing: copper isn't sexy. It's not flashy. It doesn't get Silicon Valley venture funding announcements. But it's the circulatory system of modern technology. Without it, your EV won't charge efficiently. Your power grid becomes fragile. Data centers overheat. Solar panels can't transmit power. And that shiny new AI server your company's desperately trying to buy? It's filled with copper.

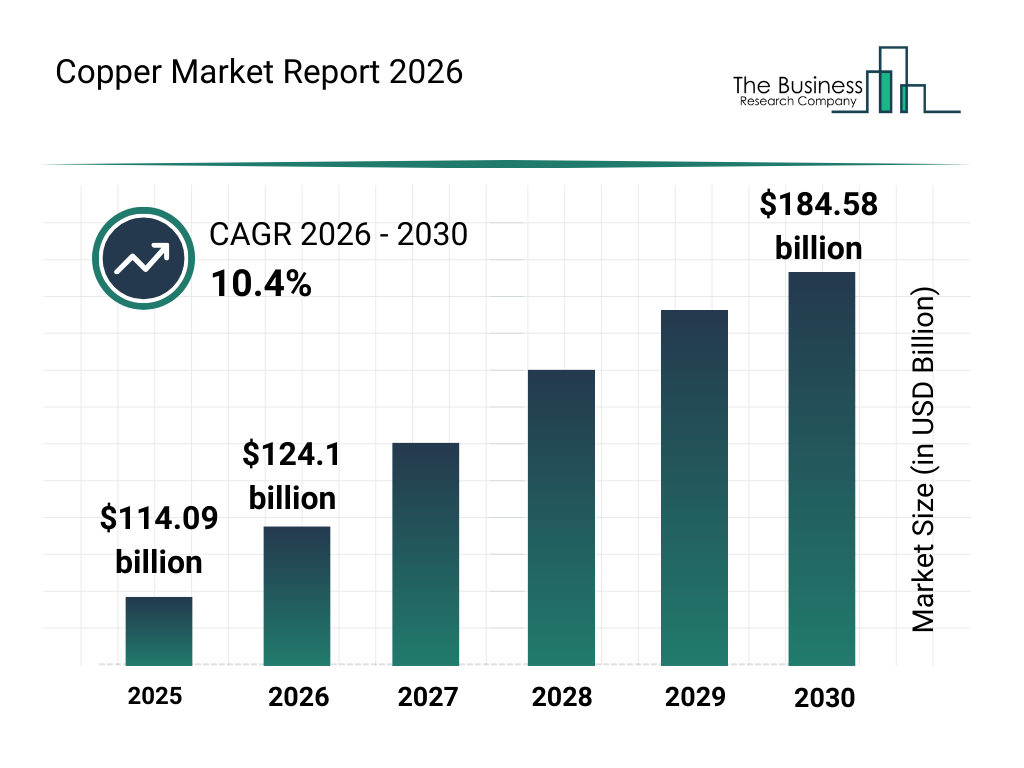

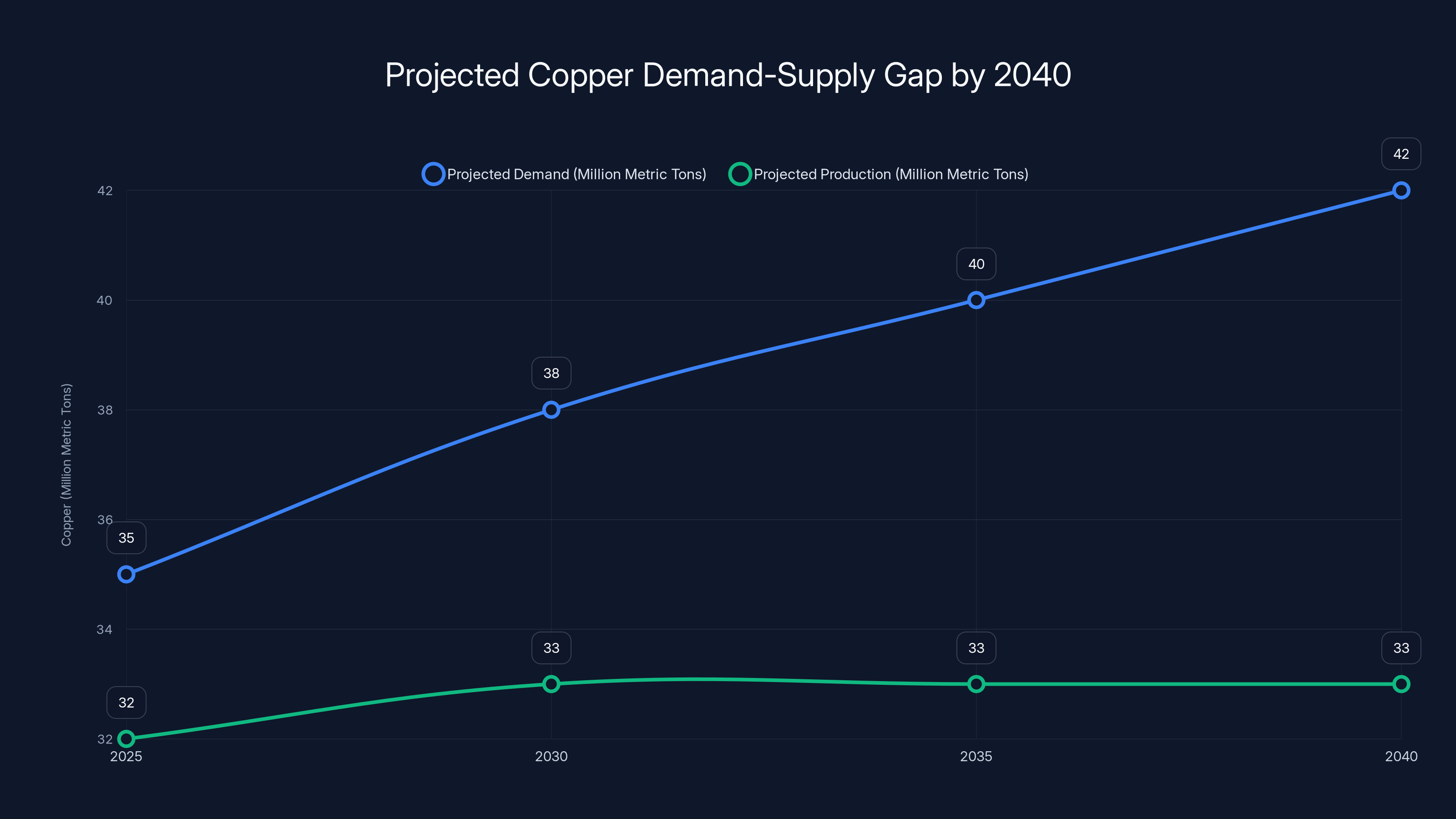

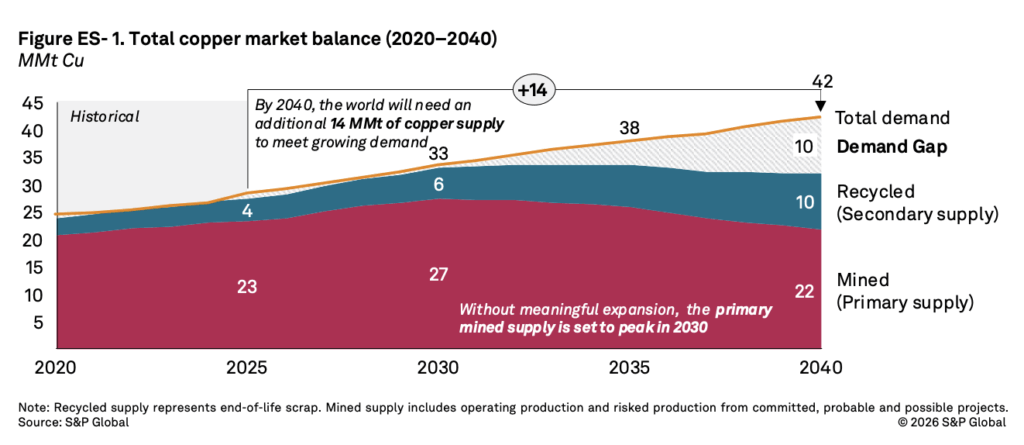

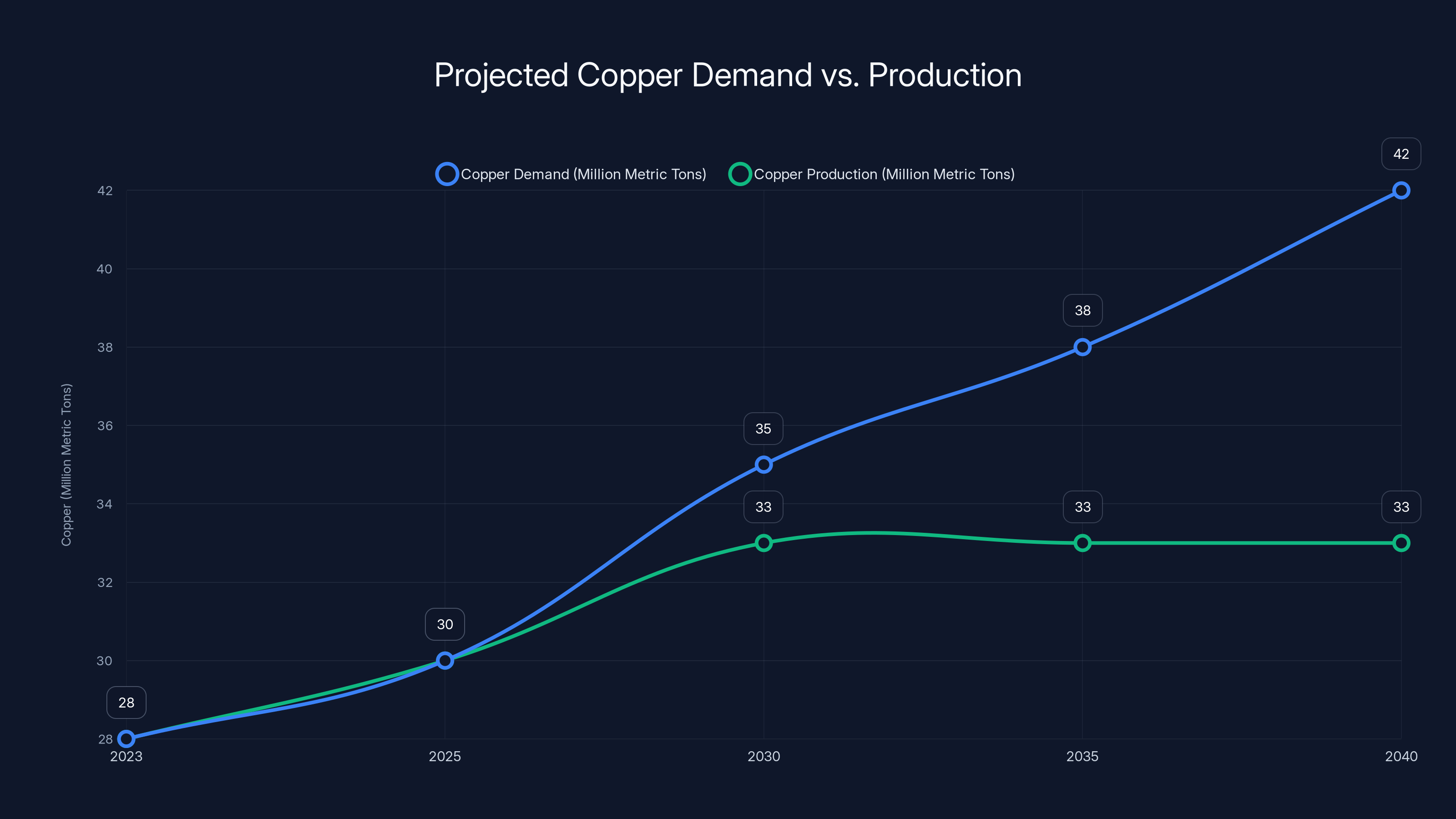

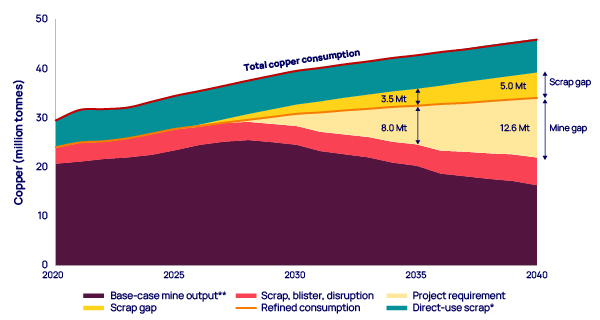

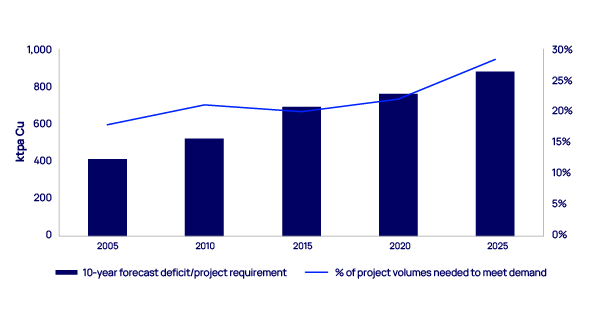

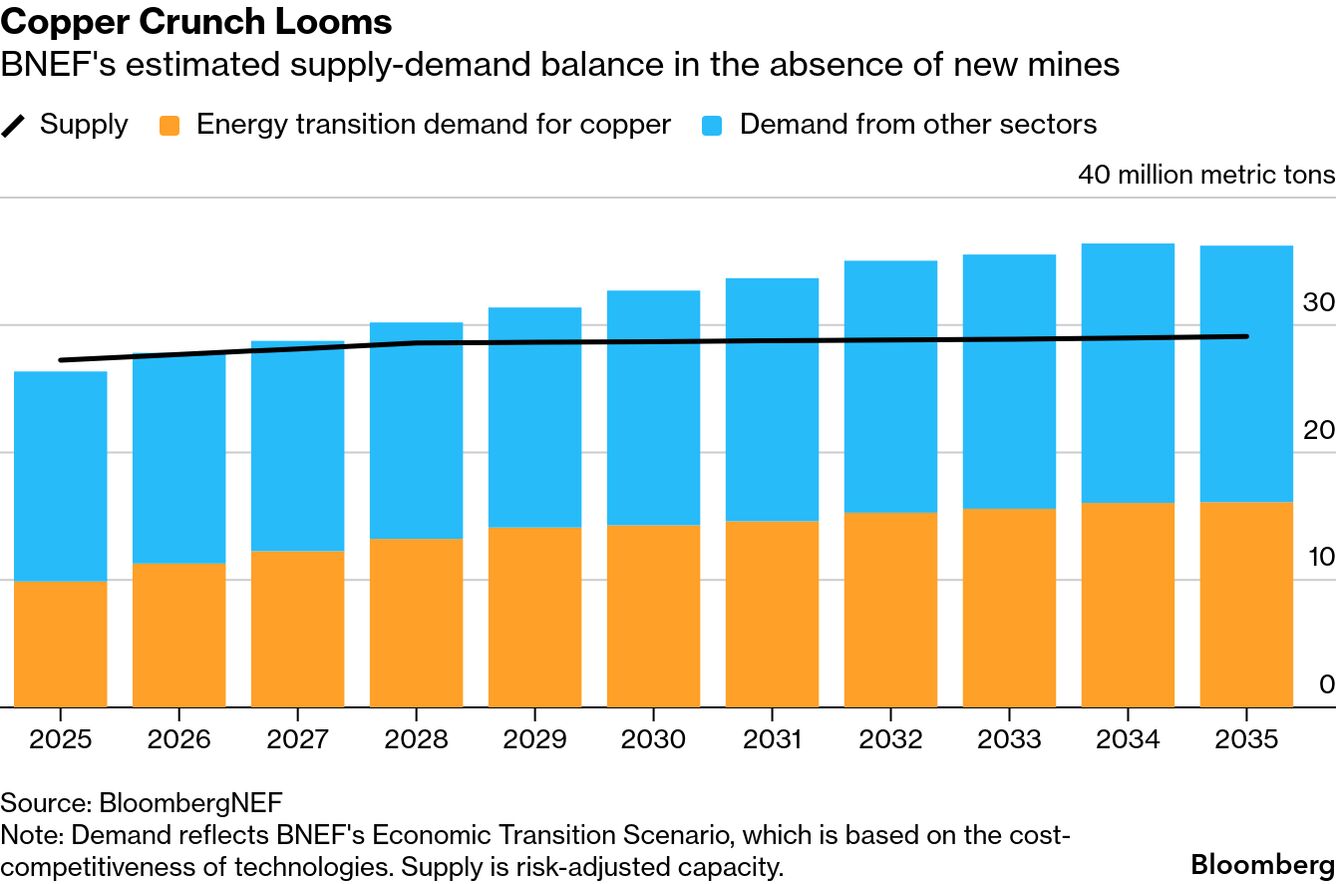

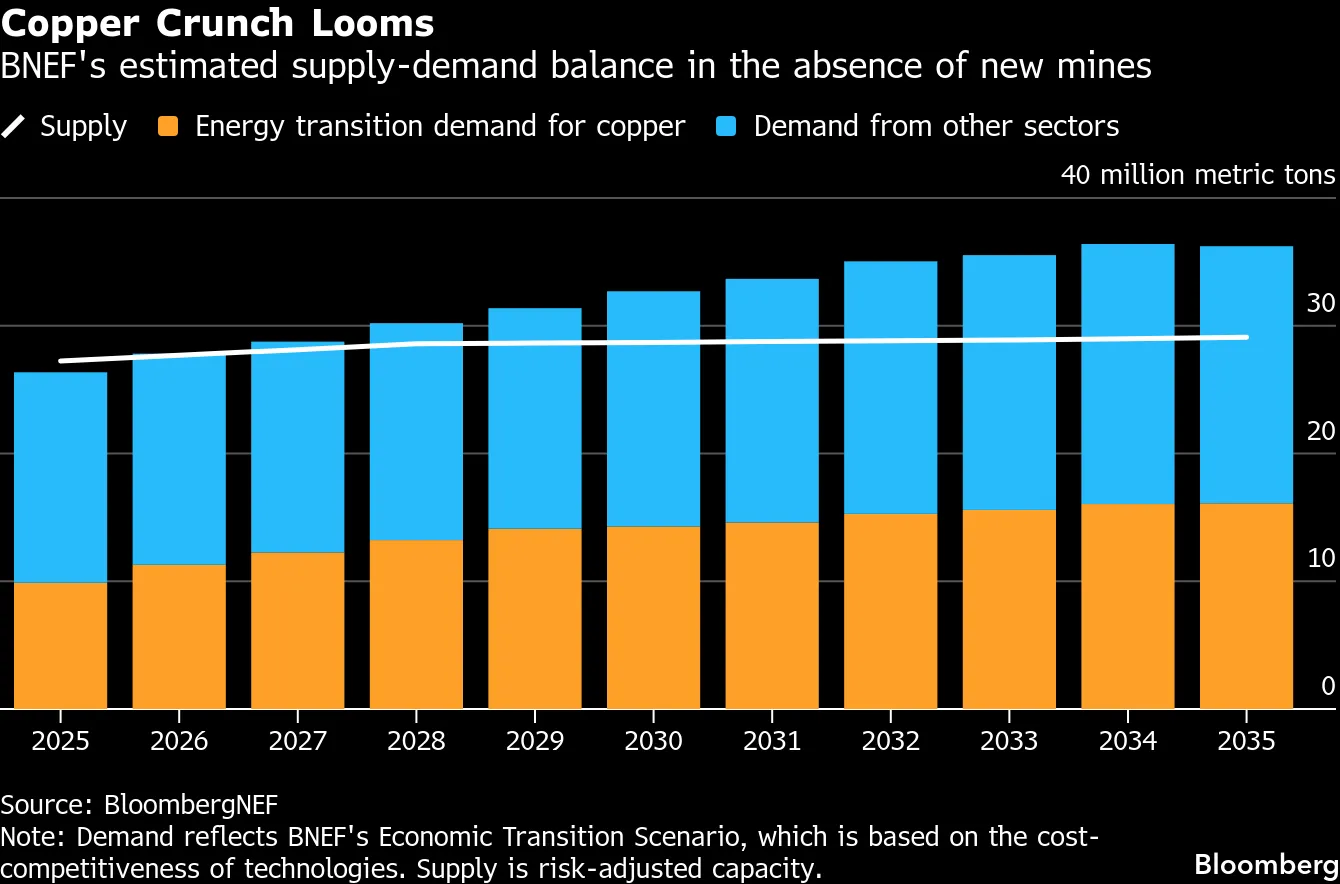

The numbers are genuinely alarming. Global copper demand could hit 42 million metric tons by 2040, representing roughly a 50% increase from today's consumption levels. But here's where it gets uncomfortable: production is expected to peak much earlier, around 2030, at approximately 33 million metric tons. That creates a potential shortfall of nearly 10 million metric tons if nothing changes.

For context, the world currently produces around 28 million metric tons of copper annually. Missing 10 million metric tons means roughly a 35% deficit compared to what the world will actually need. That's not a supply constraint. That's a crisis.

The problem isn't that copper is running out underground. Geologically, there's plenty more copper in the Earth's crust. The problem is that it takes 17 years on average to bring a new copper mine into production, and that's if everything goes perfectly. Environmental permits, community approval, infrastructure development, exploratory drilling that comes up dry. Many projects take 20, 25, even 30 years.

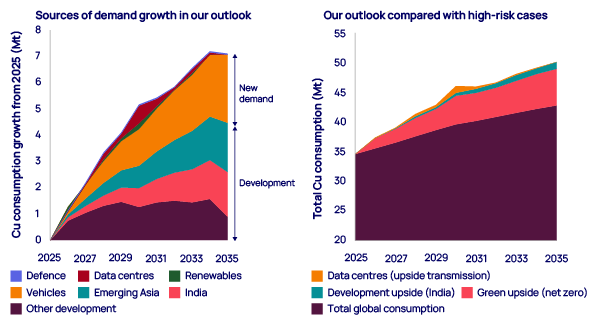

Meanwhile, the demand side isn't waiting. Electrification is accelerating globally. Governments are mandating EV adoption. Companies are racing to build data centers. Renewable energy installations are multiplying. Every single one of those trends is a copper pump, steadily draining the reservoir.

This isn't a hypothetical problem ten years out. The gap is already tightening. And if you're betting on business decisions, supply chains, or investment strategies over the next decade, understanding copper's trajectory matters more than you probably think.

Why Copper Demand Is Exploding Right Now

Copper's not a new material. Humans have been using it for thousands of years. But demand cycles follow technology adoption, and we're in the middle of the most copper-intensive technological transition since electrification happened the first time around.

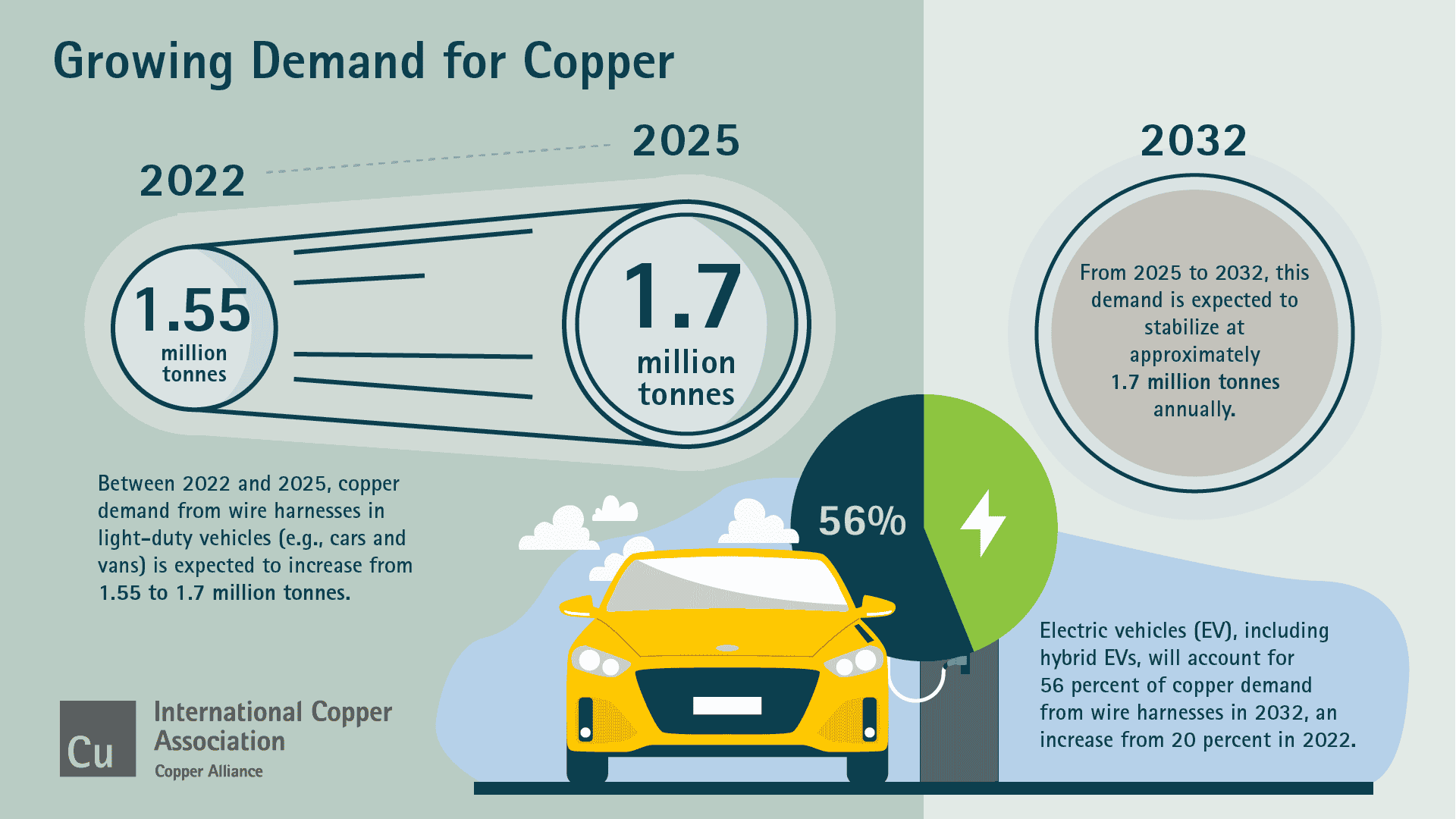

The electric vehicle boom is the most obvious driver. A traditional internal combustion engine car uses roughly 20 kilograms of copper. An electric vehicle? Try 40 to 60 kilograms. You need copper for wiring in the battery management system, for the motor windings, for charging infrastructure, for thermal management systems that keep batteries from overheating. An EV basically doubles the copper requirement compared to a gas car.

Global EV sales are accelerating. In 2023, 14% of global new car sales were electric vehicles. That number's climbing to 15-16% in 2024 and expected to reach 25-30% by 2030. If that trajectory holds, you're looking at perhaps 60 to 80 million electric vehicles on the road globally by 2030. Each one of those cars contains two to three times more copper than the vehicle it's replacing.

But it's not just cars. Grid modernization requires enormous copper investment. Every country is upgrading electrical infrastructure to handle distributed energy from solar and wind installations. Those transmission lines? Copper. The substations? Copper. Smart grid hardware that manages variable renewable energy sources? Copper wiring, copper cooling systems, copper connectors.

Renewable energy installations themselves are copper-intensive. A solar photovoltaic system uses roughly 5.5 metric tons of copper per megawatt of capacity. Wind turbines use about 3.6 metric tons per megawatt. As countries rapidly expand renewable capacity to hit climate targets, the copper demand from energy generation alone is staggering.

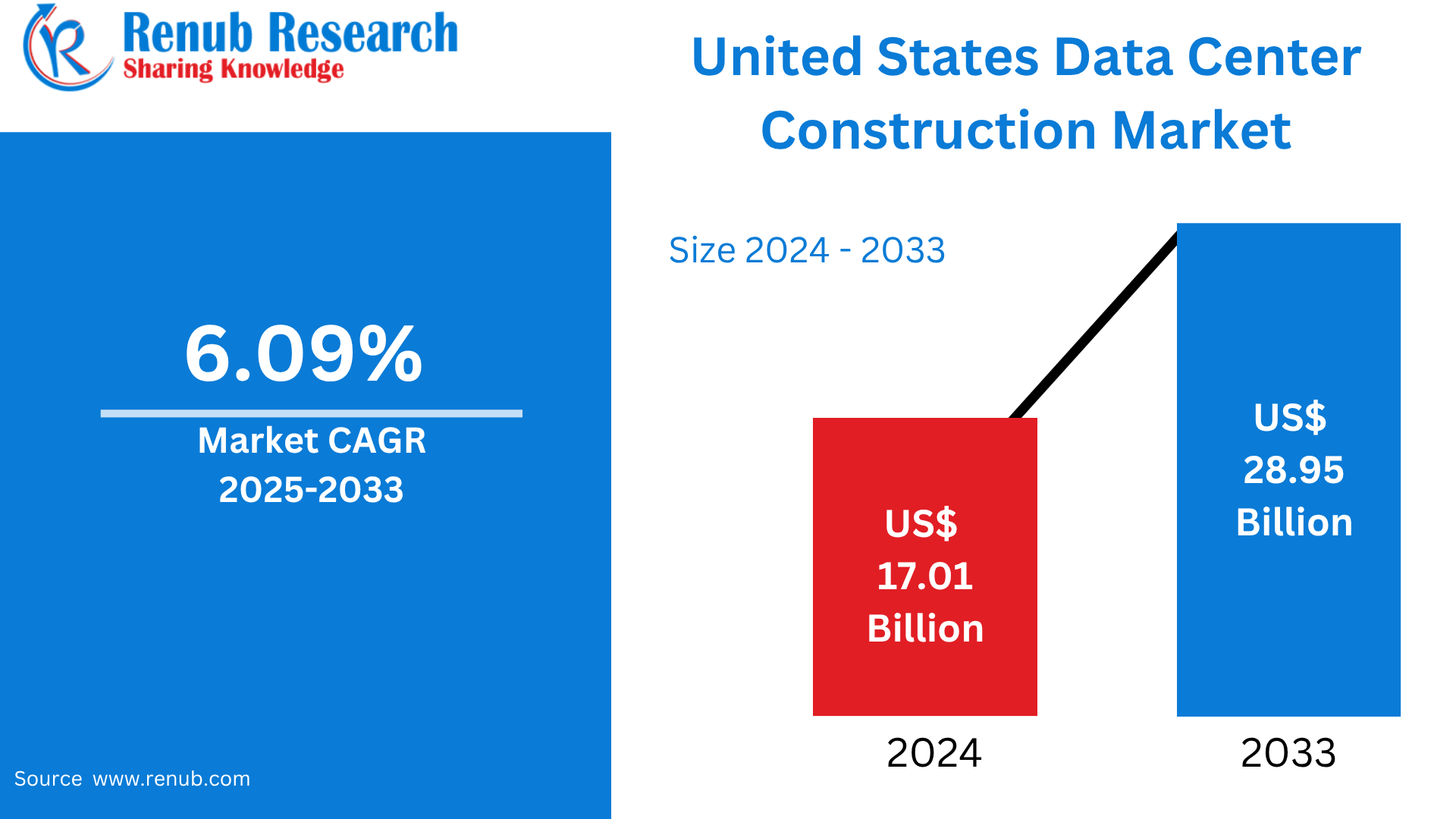

Then there's the data center explosion. AI has triggered a data center building spree unprecedented in modern history. Every GPU-accelerated server needs dense copper wiring for power distribution, cooling systems that rely on copper tubes and fittings, and interconnects between servers that increasingly use copper pathways instead of older materials. Hyperscale data centers under construction right now use more copper than entire towns used fifty years ago.

Even semiconductors themselves are becoming more copper-intensive. Modern chip design uses copper interconnects at multiple metal layers, replacing aluminum in many cases because copper has better electrical properties. Every advanced node from 5nm downward relies on copper metallization. If you're building cutting-edge silicon, you're building with copper.

The compound effect is what makes this genuinely worrying. You're not just looking at one of these trends. You're looking at all of them accelerating simultaneously. EVs, grid upgrades, renewable installations, data centers, semiconductor advances. They're not competing for copper; they're all pulling in the same direction, and they're pulling hard.

The demand isn't theoretical. It's already being baked into engineering specifications and supply chain planning at major corporations right now. The fact that supply can't keep pace is hitting planners at companies like Tesla, Nvidia, Microsoft, and every utility commission in the developed world.

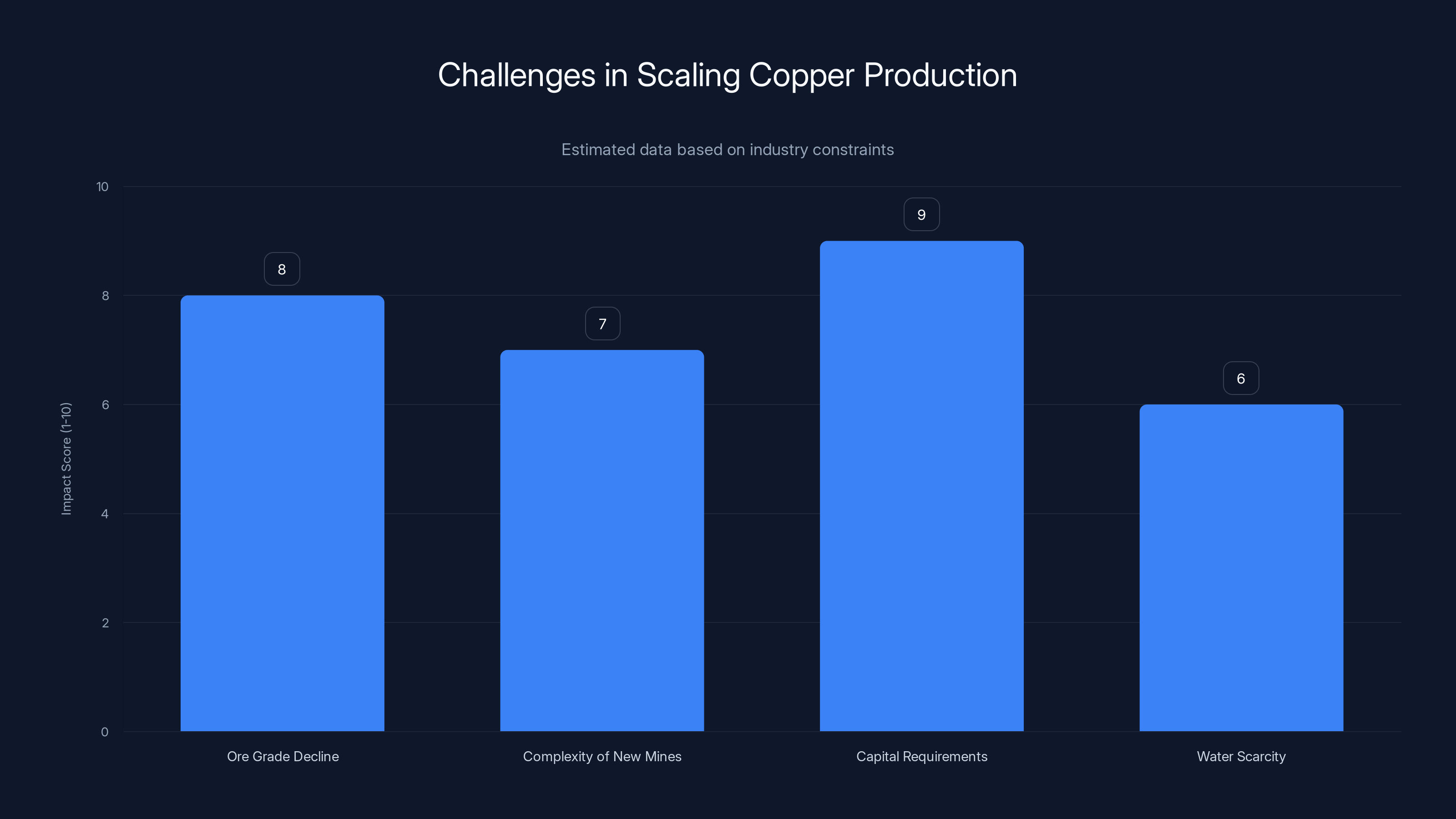

Copper production faces significant challenges, with capital requirements and declining ore grades being the most impactful. Estimated data.

Production Constraints: Why Copper Supply Can't Just Scale Up

So if demand is exploding, why doesn't the industry just build more mines? It's not like copper mining is new technology. We've been doing it for centuries. Why can't we just scale up production to meet demand?

Because copper mining is an absolute beast of a project, and it gets harder every year, not easier.

First, ore grades are declining. When mining companies find a new copper deposit, the richest ore tends to get extracted first. As they go deeper, the copper concentration in raw ore drops. You're now mining lower-grade material, which means you need to process more rock to extract the same amount of copper. More processing means higher costs, more energy consumption, more water requirements, and more environmental impact. Mining 100 million tons of low-grade ore instead of 50 million tons of high-grade ore creates completely different operational constraints.

Second, new mines face escalating complexity. Easy-to-access deposits near the surface in stable, permitting-friendly countries have already been mined. The remaining opportunities are in remote locations, often in politically unstable regions, in complicated geological formations, or in environmentally sensitive areas. This complexity adds time and cost. Permits alone can take 5 to 10 years before a single shovelful of earth moves.

Third, and this is critical, the capital requirements are enormous and rising. A modern large-scale copper mine costs

Water scarcity is becoming a genuine production limiter. Copper mining requires extraordinary amounts of water for ore processing, cooling, dust suppression, and other operations. Many of the world's major copper deposits are in Chile, Peru, Congo, and other regions facing increasingly severe drought conditions driven by climate change. Water is becoming more valuable than copper in those regions, and regulations are tightening.

Chile produces roughly 28% of global copper, and the country's been experiencing a decade-long megadrought. Water tables are dropping. Governments are increasingly reluctant to grant mining permits that consume scarce water resources. Peru, which produces about 9% of global copper, faces similar pressures and has added political instability into the mix.

Then there's the permitting and social license problem. Modern mining faces genuine opposition from environmental groups, indigenous communities, and local populations concerned about water contamination, air quality, and land use. These concerns aren't frivolous. Mining creates real environmental impacts. But the result is that mining companies now need not just government permits but also social acceptance. Getting both takes years and substantial community investment.

The timeline is the killer metric here. Taking a copper deposit from discovery to first commercial production averages 17 years. But averages are misleading. Some projects take 8 to 10 years. Others take 20, 25, or 30 years. And that's the timeline if everything goes right. If you hit permitting delays, geological surprises, political instability, or market downturns that make the project uneconomic, timelines stretch further.

Consider this: if a mining company starts developing a new copper mine in 2025, they're realistically looking at first production in 2042. By then, the copper shortage will already be in full effect. Supply decisions made today won't address the shortage until it's largely already happened.

The copper demand-supply gap is projected to widen significantly by 2040, with a potential deficit of 9 million metric tons, or about 25-30% of demand. Estimated data.

The Geographic Concentration Problem

Here's something that should genuinely worry anybody paying attention to supply chain resilience: copper processing is dangerously concentrated.

Chile, Peru, and Congo are the world's top three copper producing countries, accounting for roughly 50% of global output. But raw ore isn't directly usable. Copper must be smelted and refined, and that's where concentration gets even more problematic. China dominates copper smelting and refining, controlling between 40 and 50% of global processing capacity.

That's not a minor detail. That's a structural vulnerability in the global supply chain.

Understand what this means: even if Chile or Peru increase mining production significantly, the refined copper still needs to flow through Chinese processing facilities, because they're the cheapest and have the capacity. Any disruption in China, whether geopolitical, environmental, or operational, affects global copper supply.

This concentration echoes problems the tech industry already learned from rare earth elements and semiconductor manufacturing. When too much of a critical supply chain funnels through one country, you create systemic risk. Geopolitical tensions, trade restrictions, or even operational problems can disrupt the entire global economy.

Some efforts are underway to diversify processing capacity. Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam and Indonesia, are developing smelting operations. The United States and Europe are interested in building or re-opening processing capacity domestically to reduce dependence on China. But building a smelter is a massive undertaking. A new processing facility costs hundreds of millions to billions of dollars, takes years to develop, and requires skilled labor and substantial infrastructure investment.

The timeline problem returns: even if governments and private companies decided tomorrow to build new processing capacity in diversified locations, you're realistically looking at 5 to 10 years before meaningful additional capacity comes online. And we potentially have a supply crisis in 3 to 5 years.

Recycling Isn't the Silver Bullet

When people hear about copper shortage, the response is often: "But wait, can't we just recycle more copper?"

Recycling is part of the solution. But it's only part, and a smaller part than many people assume.

Recycling currently supplies roughly 30% of global copper demand. That's meaningful but not transformative. To close a 10 million metric ton gap would require recycling to nearly triple, and that's not realistic for several reasons.

First, recycling copper requires you to first have used copper to recycle. A copper wire installed in a building or transmission line in 2010 isn't being recycled in 2025. It's still in service, potentially for another 20 to 40 years. The copper in a smartphone you bought in 2015 might get recycled, but the copper in an EV battery pack won't be recycled until that vehicle reaches end-of-life in 2040 or 2050. There's a massive time lag between when copper is deployed and when it becomes available for recycling.

Second, recycling rates vary wildly by application and geography. In developed countries, roughly 50% of copper scrap gets recycled. In developing countries, informal recycling recovers some copper, but a lot is lost. And here's the problem: early-adopter regions for electric vehicles and renewable energy are exactly where recycling infrastructure is often weakest. You build thousands of solar farms in developing countries, but you don't get those modules back for recycling for 20 to 25 years.

Third, recycling isn't a 100% recovery process. Some copper is lost in scrap, some is contaminated by other materials, some is deliberately left in place during decommissioning because extraction costs exceed the copper's value. Recycling recovers most copper but not all.

Even under optimistic assumptions, S&P Global projects that recycled copper will account for only about one-third of total supply by 2040. That means recycling can't close the supply gap. You need primary production to increase dramatically, and the constraints we've discussed make that nearly impossible on the required timeline.

There's also a circular dependency issue: the recycling infrastructure itself depends on adequate global copper supply to build recycling facilities, transportation systems, and processing equipment.

Estimated data shows a growing gap between copper demand and production, with a potential shortfall of nearly 10 million metric tons by 2040.

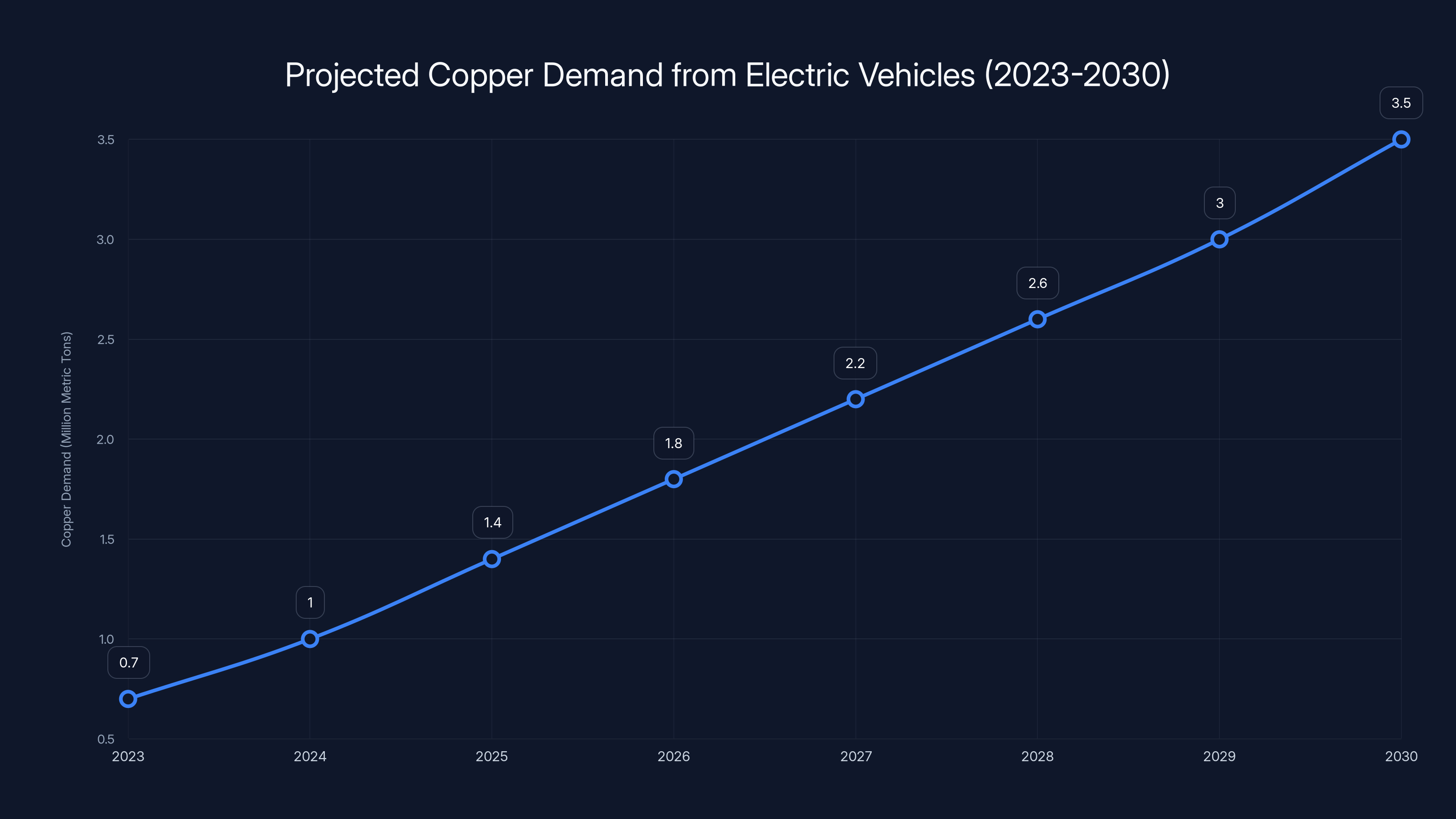

The Electric Vehicle Impact: Quantifying the Copper Demand

Let's zoom into one specific driver of copper demand because it illustrates the scale problem clearly: electric vehicles.

The global automotive industry is in the middle of the fastest transition away from one propulsion technology and toward another in its history. Internal combustion engines used roughly 12-20 kilograms of copper per vehicle. Electric vehicles use 40 to 60 kilograms, and some high-performance models exceed 80 kilograms.

That's not because engineers are being wasteful. It's because electric motors, battery management systems, and charging infrastructure are fundamentally more copper-intensive than mechanical engines.

Here's the math: In 2023, roughly 14 million electric vehicles were sold globally. That number's accelerating. By 2030, annual EV sales could reach 60 to 80 million units. Even using conservative numbers, let's assume 50 million EVs sold in 2030 and ongoing.

If each EV contains 50 kilograms of copper, that's 2.5 million metric tons of copper just for that year's EV production. That's roughly 8-9% of current global copper production devoted to one application in one year.

But it's not just the vehicle itself. Every EV needs charging infrastructure. Public charging networks require thousands of miles of copper wiring. Chargers themselves contain copper. Home charging installations contain copper. At scale, the charging infrastructure copper requirement becomes a separate, significant demand driver.

The copper requirement for EV manufacturing and charging alone could consume 15-20% of global copper production by 2030, depending on adoption rates and technology choices. That's a massive allocation to one application, leaving less copper available for everything else the world needs: grid infrastructure, data centers, renewable energy installations, industrial equipment.

What makes this particularly tight is the timing mismatch. The copper shortage threat emerges around 2028-2030, but that's exactly when EV adoption is accelerating most dramatically. The supply crunch hits precisely when demand is most intense.

Data Centers: The Unexpected Copper Glutton

There's been a lot of focus on how AI and large language models will drive chip demand. There's been less focus on an equally critical input: copper.

Modern hyperscale data centers use enormous amounts of copper, and the newest generation of AI-optimized facilities use even more than traditional data centers.

Consider the infrastructure: thousands of servers in a single facility, each generating substantial heat that must be dissipated through cooling systems. Copper is the material of choice for those cooling systems because of its thermal properties. More servers mean more cooling demand means more copper tubing, fittings, and heat exchangers.

Power distribution within a data center is copper-intensive. You've got transformers, distribution panels, and countless connection points, all using copper. A single rack of equipment might contain hundreds of individual power connections.

Server-to-server interconnects increasingly use copper pathways. Modern data centers use active optical interconnects that still rely on copper electrical connections within and between servers. The copper wiring density in a modern rack is extraordinary.

Here's the scale: A hyperscale data center providing 50 to 100 megawatts of computing capacity might require 1,000 to 2,000 metric tons of copper. That includes power infrastructure, cooling, networking, grounding, and structural elements.

Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta are collectively planning data center expansions in the tens of billions of dollars through 2025-2030. Even with shared infrastructure and efficiency improvements, that translates to tens of thousands of additional metric tons of copper required just for these companies' expansion plans.

What's particularly concerning is the speed. Data centers can be built and operational in 18 to 24 months. The copper required for these facilities must be sourced during that construction window. If copper is constrained, data center projects either face delays or bid up copper prices significantly, which cascades into costs throughout the tech industry.

Microsoft's Chief Environmental Officer stated publicly that data center power requirements are becoming a significant constraint on data center expansion. Copper scarcity could become a secondary constraint if supply tightens.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in copper demand from electric vehicles, potentially reaching 3.5 million metric tons by 2030.

Silicon Photonics: The Copper Replacement That Isn't Coming Soon

Some people in the tech industry point to silicon photonics as a potential solution to copper constraints in data centers. Instead of copper wiring for connections, you use light traveling through optical fibers. It's a genuinely clever technology and could, in theory, reduce copper demand.

Here's the problem: silicon photonics still isn't ready for mainstream deployment, and won't be for years.

Broadcom's CEO has been public about this, noting that widespread silicon photonics adoption remains "many years away." The technology works in controlled lab environments and limited commercial deployments. But getting it to the reliability, cost, and manufacturability levels required for massive-scale data center deployment is a different challenge entirely.

Beyond the technical challenges, photonics still depends on significant copper infrastructure. The photonic modules themselves need to connect to copper-based power systems, have copper thermal management, and require copper grounding. You don't eliminate copper; you reduce the quantity in specific pathways while still needing substantial amounts elsewhere.

Even if photonics achieves rapid deployment starting in 2027 or 2028, you're looking at a 5 to 10-year transition period where both old copper-based and new photonic systems coexist. That doesn't help with the shortage in the critical 2028-2035 window.

So photonics is a medium-term technology solution that might help reduce copper growth trajectories in the 2030s. It's not a solution for the immediate shortage problem.

Climate Change as an Amplifying Factor

Here's a feedback loop that doesn't get enough attention: climate change is making copper mining harder, and harder copper mining means more energy consumption, which drives more climate change.

Many major copper mining regions are experiencing water scarcity driven by changing precipitation patterns. Chile's megadrought has been ongoing for over a decade. Peru faces irregular rainfall. DRC faces increasing weather variability. All of these regions require abundant water for copper extraction and processing.

As water becomes scarcer, governments impose stricter regulations on mining water consumption. Some permits limit mining water use as water tables drop. In Chile, several mines have been required to reduce water consumption or faced permit non-renewal.

Reduced water availability forces mining companies to either extract less copper or invest in more expensive water sources. Desalination is an option for coastal mines but requires significant energy investment. Water recycling within mining operations increases operational complexity and capital requirements.

The energy requirements for copper production are also growing. Lower-grade ores require more processing energy. Alternative water sourcing (desalination, recycling) requires energy. Deeper mining operations require more pumping energy. Climate change is driving energy costs up in many regions where copper is mined.

There's also a more direct climate impact: extreme weather events are increasingly disrupting mining operations. Major flooding can shut mines for weeks. Unprecedented heat waves can force operational slowdowns. These aren't theoretical risks; they've already occurred multiple times in the last five years at major copper producing facilities.

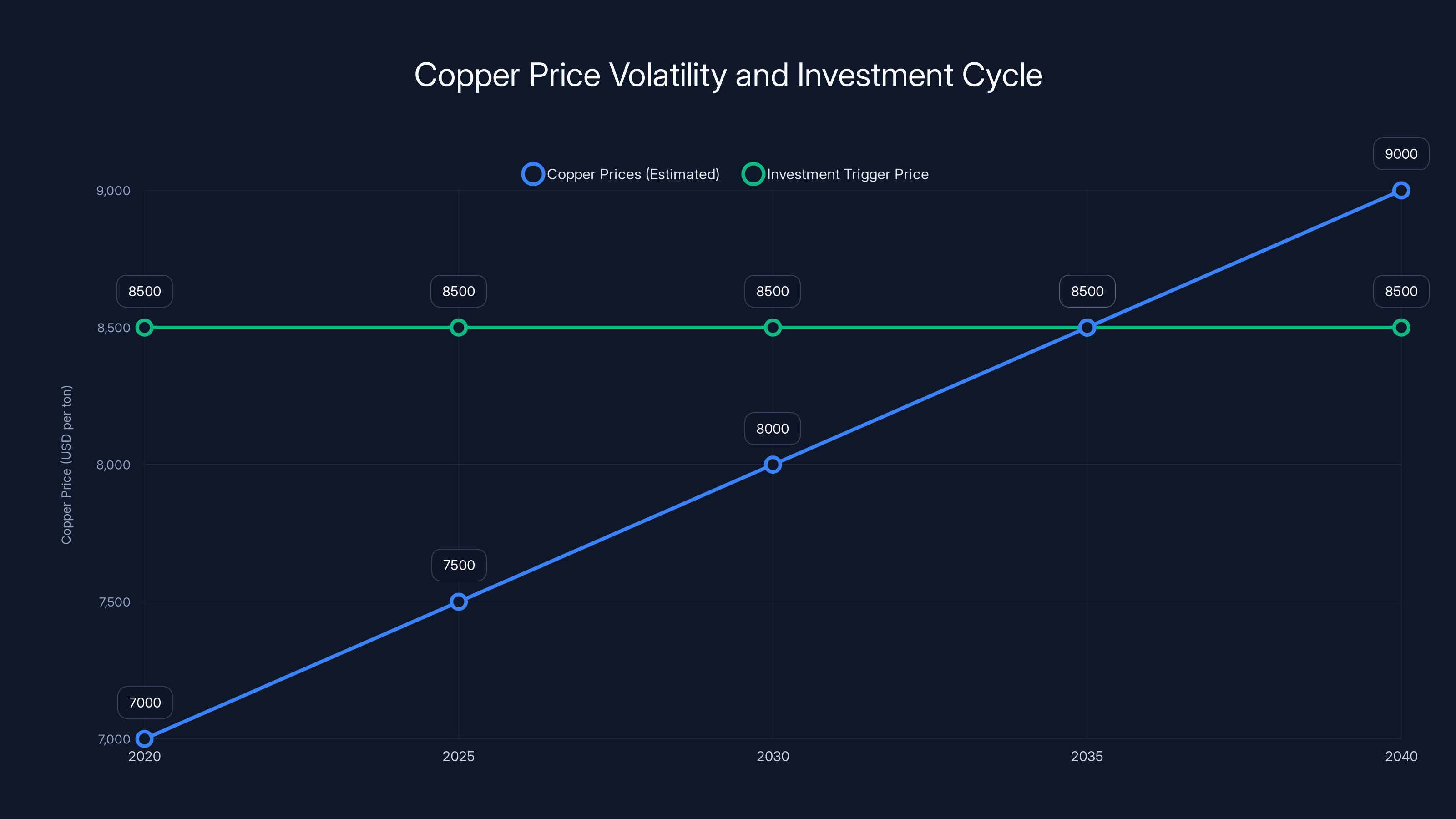

Copper prices are projected to rise gradually, but may not reach the levels needed to trigger new mining investments until after 2030. Estimated data.

Policy Responses and Their Limitations

Governments and industry organizations have started recognizing the copper shortage threat. Responses are being discussed and, in some cases, implemented. But they face real limitations.

Some governments are prioritizing domestic copper processing. The US is exploring investments in copper smelting capacity. Europe is considering similar moves. These efforts make sense strategically, reducing dependence on Chinese processing. But they take years to implement and still don't address the primary production gap.

Export restrictions by major copper producing countries could exacerbate the problem. Chile has discussed potential export controls to ensure domestic supply. Any such moves would tighten global supply, increase prices, and create trade tensions.

Strategic reserve programs are being discussed. Some countries are considering building copper stockpiles, similar to national petroleum reserves. This could help stabilize markets during disruptions, but it's not a solution to chronic shortage. A stockpile just defers demand; it doesn't create new supply.

Accelerated permitting for new mines is happening in some countries. Canada has streamlined environmental assessments for mining projects. Australia has supportive policies for mining expansion. But this is fighting against a broader regulatory trend toward stronger environmental standards, which extend permitting timelines.

Investment in mining technology to improve efficiency is ongoing. Autonomous trucks reduce labor costs. Advanced processing techniques improve recovery rates. Better ore detection technology reduces exploration time. But these improvements tend to be incremental, not transformative. They extend timelines by months, not years. They don't solve a shortage that emerges in 3-5 years.

The fundamental challenge is that the timeframes don't align. The supply problem emerges in the late 2020s. Solutions implemented today won't meaningfully impact supply until the 2030s.

Market Price Signals and Investment Cycles

One might expect that copper price signals would encourage rapid investment in new mines and processing capacity. High prices should attract capital and innovation.

But copper markets don't quite work that way, and understanding why illustrates the problem.

Copper prices have been relatively volatile but haven't hit crisis levels yet. Prices are elevated compared to historical averages, but not so high that they trigger emergency responses from major consumers. Tech companies absorb copper price increases into product costs. Utilities pass them on to ratepayers.

Price signals that would trigger major behavioral changes (like abandoning copper for alternatives in certain applications) are probably higher than current levels. And by the time prices rise that high, the shortage would already be acute.

Moreover, mining investment decisions are made on 10-20 year timescales. A mining company deciding in 2025 whether to invest in a new copper mine is committing hundreds of millions to billions of dollars on the expectation that copper prices will remain sufficiently high for 15-20 years to justify the investment. That's a risky bet. Prices could fall if demand weakens or new technology reduces copper requirements.

So you get a mismatch: current prices might be too low to justify new mining investments that take 15-20 years, but if you wait for prices to rise higher, the supply shortage is already happening, and it's too late to build new mines in time.

This is a classic market failure in commodities with long development timelines. The market mechanism that's supposed to balance supply and demand through price signals doesn't work well when supply expansion takes longer than demand growth cycles.

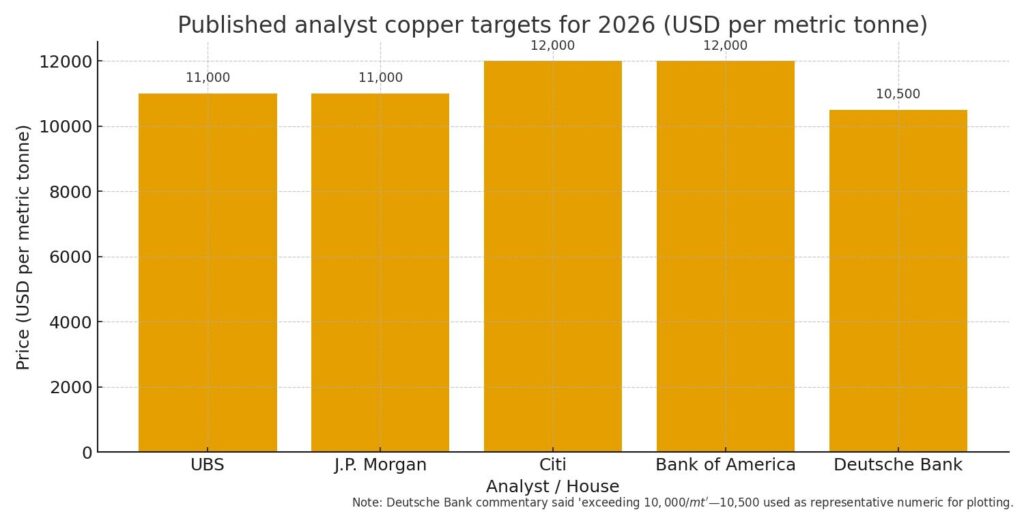

Copper prices are projected to rise significantly, peaking around 2029 due to supply constraints before stabilizing in 2030 as new capacities come online. (Estimated data)

Industry Adaptation and Substitution Efforts

With copper scarcity likely on the horizon, companies in copper-dependent industries are exploring alternatives and efficiency improvements.

Aluminum is sometimes used as a copper substitute, particularly in wiring applications. Aluminum is more abundant and typically cheaper. But it has lower electrical conductivity, so more material is needed. Aluminum wiring also faces safety and reliability concerns in certain applications. Full substitution isn't feasible in many cases.

High-temperature superconductors could theoretically replace some copper applications by offering zero-resistance power transmission. But superconductors require cryogenic cooling, adding complexity and cost. Widespread deployment is decades away, if it happens at all.

Some companies are optimizing designs to use less copper. Engineers are redesigning circuits to reduce copper interconnect density. Cable management systems are being optimized to reduce total wire length. These efforts help but are fundamentally constrained: you can't eliminate copper from most electrical and electronic systems; you can only reduce quantities marginally.

Supply chain consolidation is occurring. Larger companies are securing copper supplies through long-term contracts or strategic partnerships with miners. This protects big players but potentially worsens scarcity for smaller companies without market power.

Vertical integration strategies are emerging. Some tech companies and renewable energy installers are investing in mining operations or strategic partnerships to secure supply. This reduces market efficiency by taking material out of open markets but makes sense for companies facing existential supply risk.

None of these adaptation strategies solve the fundamental problem: global demand is outpacing supply growth, and that gap is widening. Efficiency improvements and substitution can reduce the severity of the shortage but can't eliminate it.

Global Economic Implications

A copper shortage doesn't just affect tech companies and utilities. It ripples through the entire global economy.

Energy transition timelines would stretch. Countries have committed to renewable energy targets. Meeting those targets requires substantial copper for generation infrastructure, transmission, and distribution. Copper scarcity forces choices: delay renewable rollouts, accept higher costs, or sacrifice other projects. None of these options are appealing.

Electric vehicle adoption could slow. Automakers might reduce EV production to manage costs. This delays transportation decarbonization and extends dependence on fossil fuels longer than climate targets require. In developing countries, EVs might become even less affordable, perpetuating inequality in access to new transportation technology.

Technology infrastructure could face capacity constraints. Data centers might be slower to scale. Telecommunications networks might upgrade more slowly. Internet penetration in developing regions could stall. Computing power, which has been rapidly democratizing and becoming more accessible, might become more expensive and limited.

Developing economies face particular risk. Countries investing in power grid improvements, renewable energy, and new industrial infrastructure would face increased costs and delayed timelines. The countries that most need to modernize infrastructure face the biggest barriers to doing so in a copper-constrained world.

Inflation could spike. If copper prices rise sharply to ration constrained supply, products containing significant copper costs more. Electrical equipment, vehicles, and industrial machinery all become more expensive. This affects everything from housing construction to industrial manufacturing.

Geopolitical tensions could intensify. Countries depending on imported copper might restrict other exports or take other protectionist measures. Large consuming nations might engage in resource competition. This could strain international trade relationships and economic cooperation.

The copper shortage isn't purely a technical or supply chain problem. It's an economic and geopolitical challenge with ramifications across every major system society depends on.

The Next Five Years: What's Likely to Happen

Looking at the 2025-2030 period specifically, here's what the available data suggests is likely:

2025-2026: Tightening without crisis. Copper supply remains adequate but starts feeling constrained. Prices gradually rise. Mining companies announce new projects, but no major new capacity comes online. Demand continues growing, outpacing supply growth rate.

2027-2028: Mounting pressure. Copper prices reach the highest levels in recent history. Some industries face minor supply disruptions or are forced to shift to alternative materials. Long-term supply contracts become standard. Spot market availability decreases as most copper is pre-contracted.

2029-2030: Peak shortage risk. If no major new production capacity comes online by this period (which is likely given 17-year timelines), the supply-demand gap becomes acute. Price spikes occur. Some projects face delays or cancellation due to copper availability and cost. This is the period where shortage risk is highest.

2030+: Adaptation and adjustment. By the early 2030s, some new mining capacity and processing facilities come online, beginning to ease pressure. Technologies developed in response to shortage (improved efficiency, substitution, recycling improvements) start mattering. Demand growth may slow as higher prices reduce consumption in price-elastic applications. Supply and demand rebalance, though at a higher price level than today.

This timeline assumes current trends continue and no extraordinary interventions occur. Breakthrough technologies, major policy shifts, or unexpected demand destruction could alter this trajectory.

What Companies and Investors Should Do Now

If you're in industries that depend on copper, waiting for the shortage to resolve isn't a viable strategy. There are actionable steps:

Secure long-term supply contracts now. Lock in copper availability at predictable prices for the next 5-10 years. This provides certainty for planning and insulates against price volatility. Smaller companies might need to band together to have enough purchasing power to attract supply contracts.

Invest in efficiency and design optimization. Engineer products and systems to use less copper. This isn't trivial, but it's more feasible than finding new supply sources. Every kilogram of copper reduced from your product portfolio reduces your exposure to shortage risk.

Diversify supply sources. Don't depend on copper from one region or mined by one company. Work with suppliers in different geographies. This increases resilience if one region faces disruption.

Explore strategic partnerships. Some companies might benefit from investing in mining operations or processing capacity alongside mining companies. This secures supply and captures upside if copper prices rise.

Monitor technological alternatives actively. Stay informed about photonics, alternative materials, and efficiency technologies that might reduce copper requirements. Position your company to adopt these technologies quickly if they mature.

Participate in industry and policy advocacy. Work with industry groups to advocate for faster permitting of new mines and processing capacity. Support policies that diversify processing geography. Even though individual companies can't solve the shortage, collective industry action might accelerate solutions.

The Reality Check

Let's be honest about what can realistically happen to address this:

Major new copper mines won't be developed fast enough. It's not because the technology is difficult; it's because the permitting, financing, and development timelines are inherently long. Even if every company and government committed today to accelerating mining development, you're still looking at the earliest new major capacity in 2030-2032.

Recycling won't close the gap. It will help, but not enough to solve the problem.

Price signals will rise, but maybe not as dramatically as supply-demand math would suggest, because alternatives (however imperfect) exist and behaviors will adapt. But prices will still be higher than today, which affects everything built with copper.

Some projects will be delayed. Some companies will struggle. Some countries' development timelines will stretch. Some technologies that were economical at lower copper prices will become uneconomical.

But the world won't stop. Copper shortage won't paralyze civilization. It will create challenges, require adaptation, force trade-offs, and shift economic value. Some winners and losers will emerge. But this is manageable if anticipated, not catastrophic.

The real risk is complacency. If companies and governments treat this as a problem for someone else to solve, the adaptation will be more chaotic and costly than necessary. If they start planning now, the copper shortage becomes a constraint that's handled, not a crisis that hits.

FAQ

What is the copper demand-supply gap?

The copper demand-supply gap refers to the projected shortage between how much copper the world will need and how much the mining and recycling industries will be able to produce. Analysts project global demand could reach 42 million metric tons by 2040, but production is expected to peak around 33 million metric tons. This creates a potential deficit of approximately 9 to 10 million metric tons, or about 25-30% of projected demand. This gap emerges primarily in the late 2020s and 2030s.

How does electrification drive copper demand?

Electrification—the transition to electric vehicles, renewable energy, and electric-powered systems—drives copper demand because electrical systems require significantly more copper than the mechanical or fossil fuel systems they replace. Electric vehicles use 40 to 60 kilograms of copper per vehicle compared to 12 to 20 kilograms for traditional cars. Renewable energy installations require copper for generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure. Electric grid modernization requires extensive copper wiring and equipment upgrades. Together, these electrification trends create exponential growth in copper consumption.

Why does mining new copper take so long?

Developing a new copper mine typically takes 17 years on average from initial exploration to commercial production. This timeline includes mineral discovery, feasibility studies, environmental impact assessments, obtaining government permits, securing financing, building infrastructure, constructing the mining facility, and beginning operations. Permits alone can take 5 to 10 years, and environmental assessments are increasingly rigorous. Geological surprises, community opposition, or political delays can extend timelines to 20 or 30 years. This extended timeline is the fundamental mismatch between supply creation and demand growth.

Can recycled copper solve the shortage?

Recycled copper will help but cannot fully solve the shortage. Recycling currently supplies about 30% of global copper demand, and optimistic projections suggest this could reach approximately 33-35% by 2040. However, there's a significant time lag between when copper is first deployed (in an infrastructure project built in 2015) and when it becomes available for recycling (when that project reaches end-of-life in 2040 or 2050). Additionally, recycling rates vary globally, with developing countries having less sophisticated recycling infrastructure. Therefore, recycling can reduce shortage severity but cannot replace the need for significant primary copper production growth.

How does China's dominance in copper processing create vulnerability?

China controls between 40 and 50% of global copper smelting and refining capacity, creating a geographic concentration risk. This means that even if copper mining countries like Chile, Peru, and Congo increase raw ore production, the refined copper must still be processed through Chinese facilities, which are the most cost-effective and have the capacity. Any disruption in China—whether geopolitical, environmental, or operational—cascades throughout the global copper supply chain. This concentration mirrors historical supply chain vulnerabilities with rare earth elements and semiconductor manufacturing, creating systemic economic risk.

Will silicon photonics replace copper in data centers soon?

Silicon photonics represents a promising long-term technology that could reduce copper usage in data center interconnects by using light instead of electrical signals. However, widespread adoption is likely 5 to 10 years away, making it too late to address the immediate copper shortage expected in the late 2020s. Additionally, photonic systems still require substantial copper infrastructure for power systems, cooling, and grounding. Even when photonics achieves mainstream deployment, a transition period will exist where both technologies coexist, maintaining copper demand at elevated levels.

What should companies do to prepare for copper shortage?

Companies dependent on copper should secure long-term supply contracts now to lock in availability and prices, invest in design optimization to reduce copper usage per product, diversify copper suppliers across geographic regions and companies, and explore strategic partnerships with mining operations. Additionally, companies should monitor alternative materials and efficiency technologies, participate in industry advocacy for faster permitting of new mines, and build flexibility into supply chains. These actions reduce vulnerability to price spikes and supply constraints.

How will copper shortage affect developing countries?

Developing countries face particular vulnerability to copper shortage because many depend on imports for infrastructure modernization and industrial development. Rising copper prices and supply constraints could delay renewable energy installations, power grid upgrades, and manufacturing facility development. Countries pursuing electrification and transportation decarbonization could find these transitions more expensive and slower than projected. Copper shortage could widen economic inequality between developed nations that can afford constrained supply and developing nations competing for limited resources.

What impact could copper shortage have on renewable energy deployment?

Renewable energy installations—solar, wind, and others—are copper-intensive, requiring approximately 5.5 metric tons of copper per megawatt for solar and 3.6 metric tons per megawatt for wind. Copper shortage could slow renewable energy rollout, delaying countries' progress toward climate targets and renewable energy commitments. Projects might face delays due to copper unavailability or become uneconomical if copper prices rise significantly. This creates a paradoxical situation where the energy transition that drives copper demand itself becomes constrained by copper supply.

Summary

The copper shortage isn't hype or speculation. It's a mathematical reality emerging from the collision between accelerating demand driven by electrification and supply constraints rooted in geological limitations and permitting timelines.

Global demand for copper could reach 42 million metric tons by 2040, but production capacity likely peaks around 33 million metric tons. That gap is real, significant, and will create economic and logistical challenges throughout the 2030s.

The problem isn't that copper is running out geologically. It's that the supply industry can't expand production fast enough to match demand growth. New mines take 17 years to develop. Recycling can't close the gap. Geographic concentration in processing creates vulnerability. Climate pressures are tightening water availability in mining regions.

This matters for every technology company, energy company, automaker, infrastructure investor, and government planning for the next decade. The shortage won't destroy civilization, but it will reshape economics, force adaptation, and create winners and losers.

The companies and countries that start planning today—securing supply contracts, optimizing designs, developing alternatives—will navigate the shortage far more successfully than those that wait for the crisis to force action. The time to respond isn't when copper is already scarce and expensive. It's now, when there's still opportunity to build resilience.

Copper didn't get the headlines that RAM or chips did. But it's arguably more critical to everything you depend on. And that shortage is coming whether anyone's paying attention or not.

Key Takeaways

- Global copper demand could reach 42 million metric tons by 2040, but production peaks at 33 million—creating a 9-10 million metric ton shortage

- New copper mines take an average of 17 years to develop from exploration to production, creating a supply timeline mismatch with demand growth

- Electric vehicles use 40-60 kg of copper each versus 12-20 kg for traditional cars, doubling copper intensity as EV adoption accelerates

- China dominates copper smelting and refining with 40-50% of global capacity, concentrating supply chain vulnerability in a single country

- Climate change-driven water scarcity in major copper producing regions (Chile, Peru) threatens mining operations and increases production costs

- Recycling can supply only about one-third of global copper demand by 2040, unable to close the supply gap created by electrification

- Data center expansion for AI creates additional copper demand pressure at the exact moment supply becomes most constrained

- Silicon photonics technology won't address the shortage because it's 5-10 years away from mainstream deployment and still requires substantial copper infrastructure

Related Articles

- Framework Desktop PC Price Hike: Why RAM Costs Are Crushing PC Builders [2025]

- DDR5 Memory Prices Could Hit $500 by 2026: What You Need to Know [2025]

- SPHBM4 HBM Memory: How Serialized Substrates Are Reshaping AI Accelerator Economics [2025]

- MayimFlow: Preventing Data Center Water Leaks Before They Happen [2025]

![Copper Shortage Crisis: How Electrification Is Straining Global Supply [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/copper-shortage-crisis-how-electrification-is-straining-glob/image-1-1768428446284.png)