Data Center Backlash Meets Factory Support: The Supply Chain Paradox [2025]

Last month, Pamela Griffin stood at a microphone in a Taylor, Texas city council meeting and spoke against a data center project. The facility would consume massive amounts of electricity, strain water resources, and fundamentally change the character of her hometown. She wasn't alone in her concerns. Across the country, residents are waking up to the real costs of the artificial intelligence boom, and data centers have become the visible target of that frustration.

But here's what happened next at that same council meeting: when discussions turned to a factory for Taiwanese manufacturer Compal, Griffin didn't object. Neither did anyone else.

This pattern is repeating in communities from Virginia to Arizona. While data centers face unprecedented public resistance, the factories that supply them—churning out servers, cooling systems, electrical components, and semiconductors—are sailing through local approval processes with minimal opposition. This creates a fascinating and troubling paradox: communities are actively rejecting the end product while enthusiastically embracing the components that make it possible.

The dynamic reveals something critical about how we're building the infrastructure for the AI era. It also exposes a vulnerability that supply chain experts say activists could exploit, and a potential trap that communities are walking into without fully understanding the implications.

TL; DR

- Data center protests are escalating while server and component factories face virtually no organized resistance, creating a critical supply chain gap

- Communities are offering massive incentives to manufacturers, with tax breaks often exceeding $4 million for facilities creating 900+ jobs

- The supply chain is a potential chokepoint that activists could target, but organizers lack resources to fight on multiple fronts

- Most residents and officials don't realize that the factories they're welcoming directly support data center construction and expansion

- This opacity could become a strategy for the data center industry to bypass local opposition by fragmenting approval processes across multiple facilities

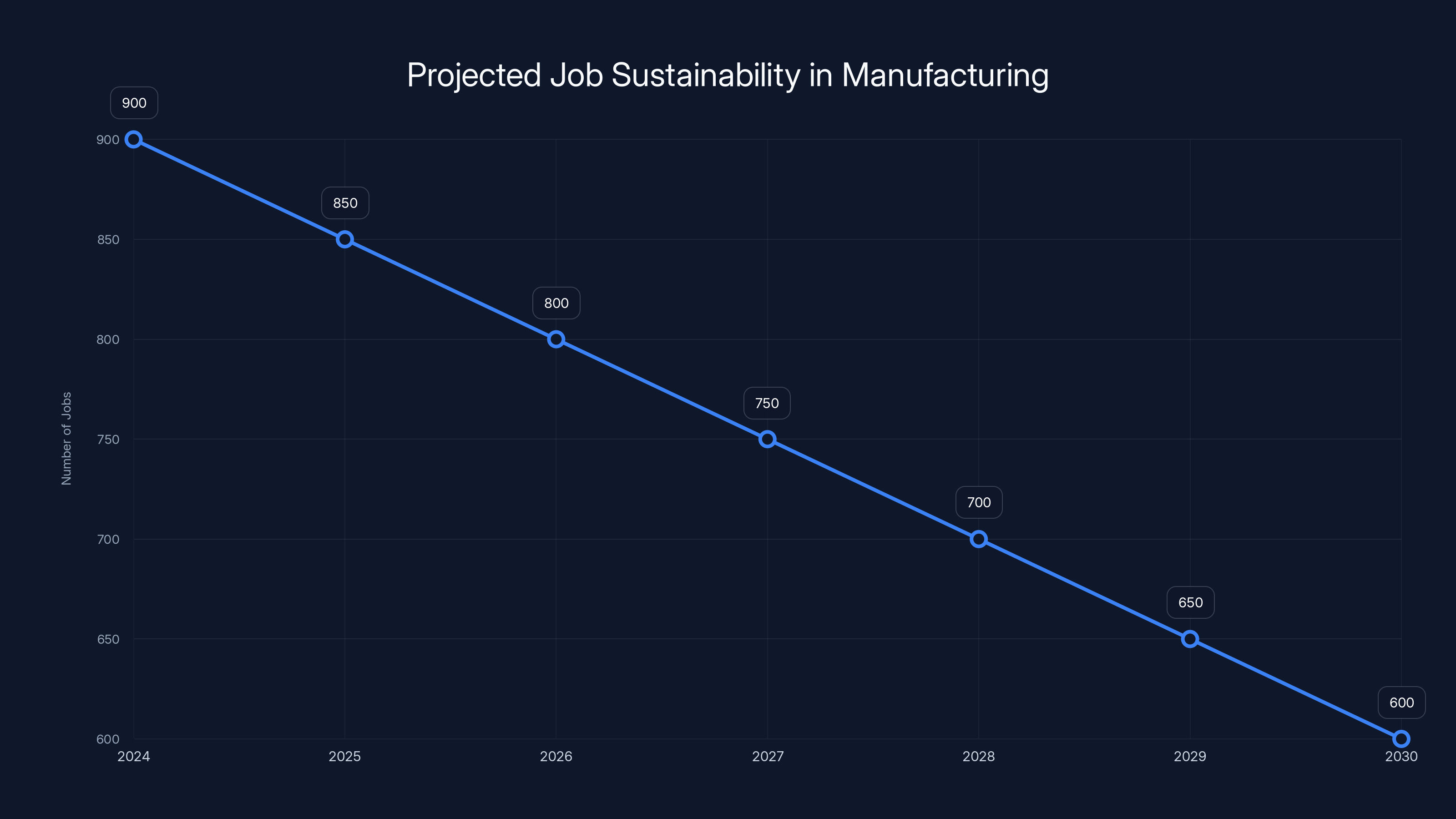

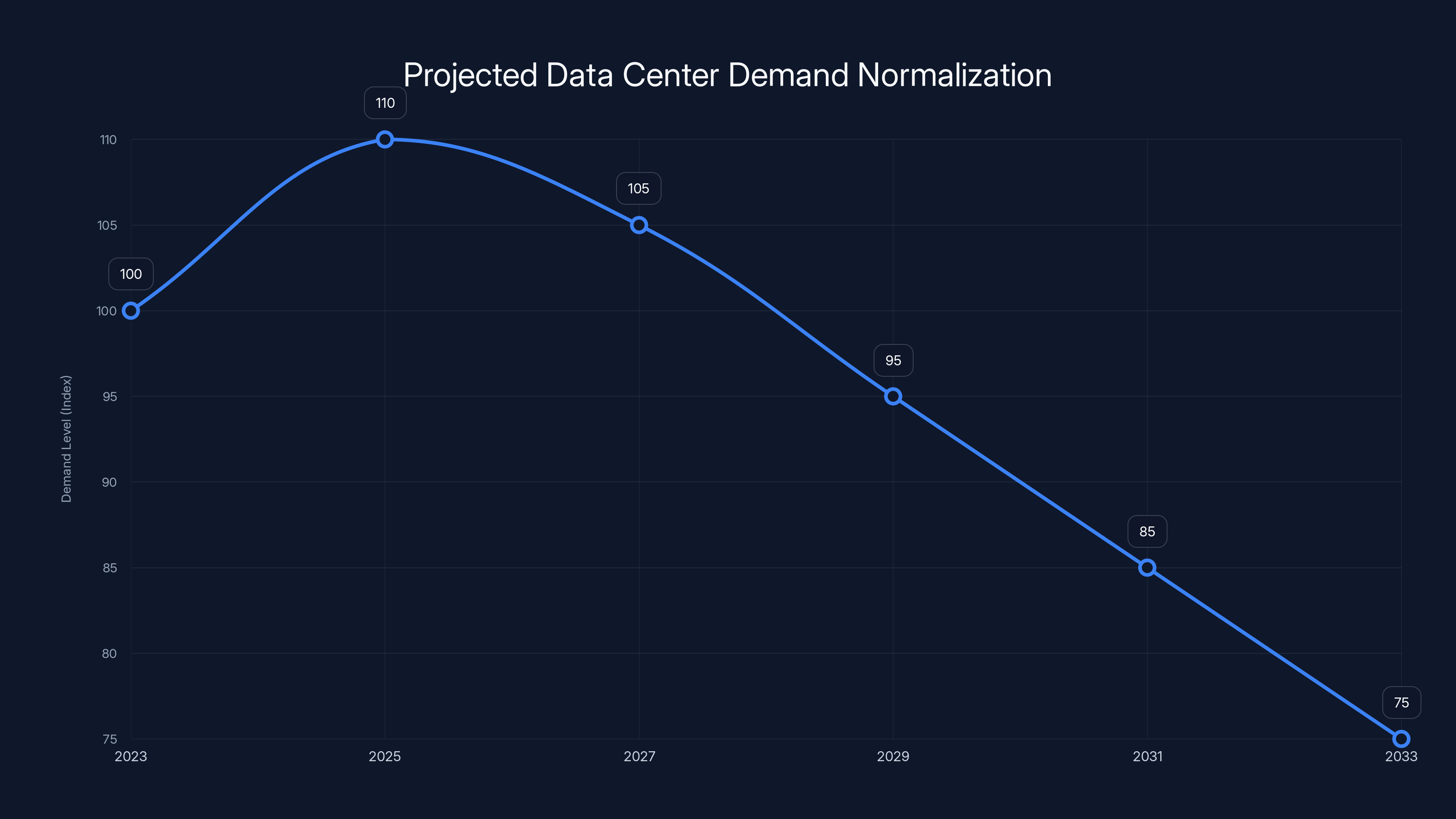

Projected job numbers at Compal's facility show a decline due to automation and potential market saturation. Estimated data.

The Great Data Center Resistance: Understanding the Backlash

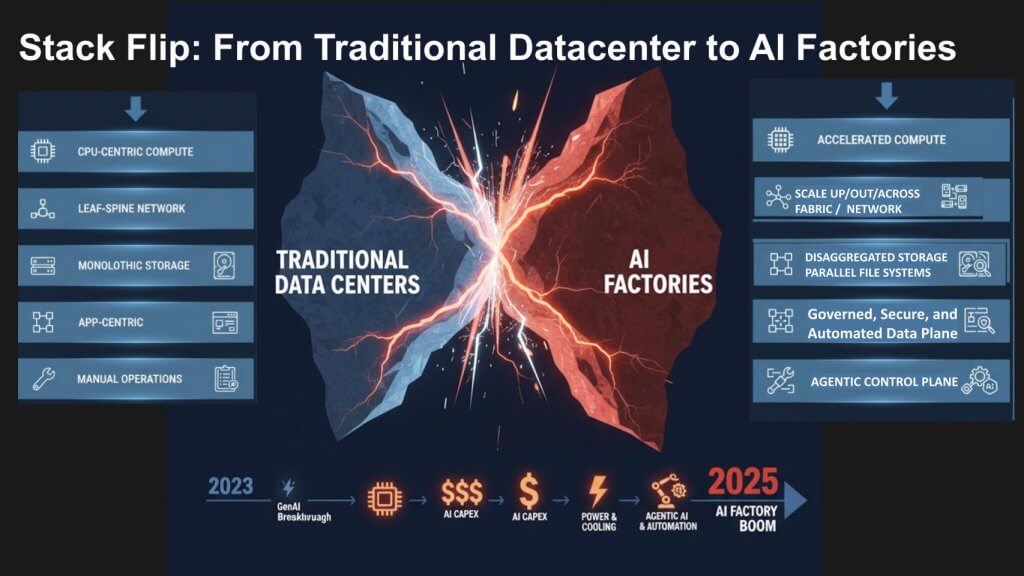

Data centers have become the flashpoint for anxieties about artificial intelligence and technological change. Unlike smartphones or software, data centers are massive physical infrastructure—often visible from highways, consuming as much electricity as small cities, and drawing water from communities already facing drought concerns.

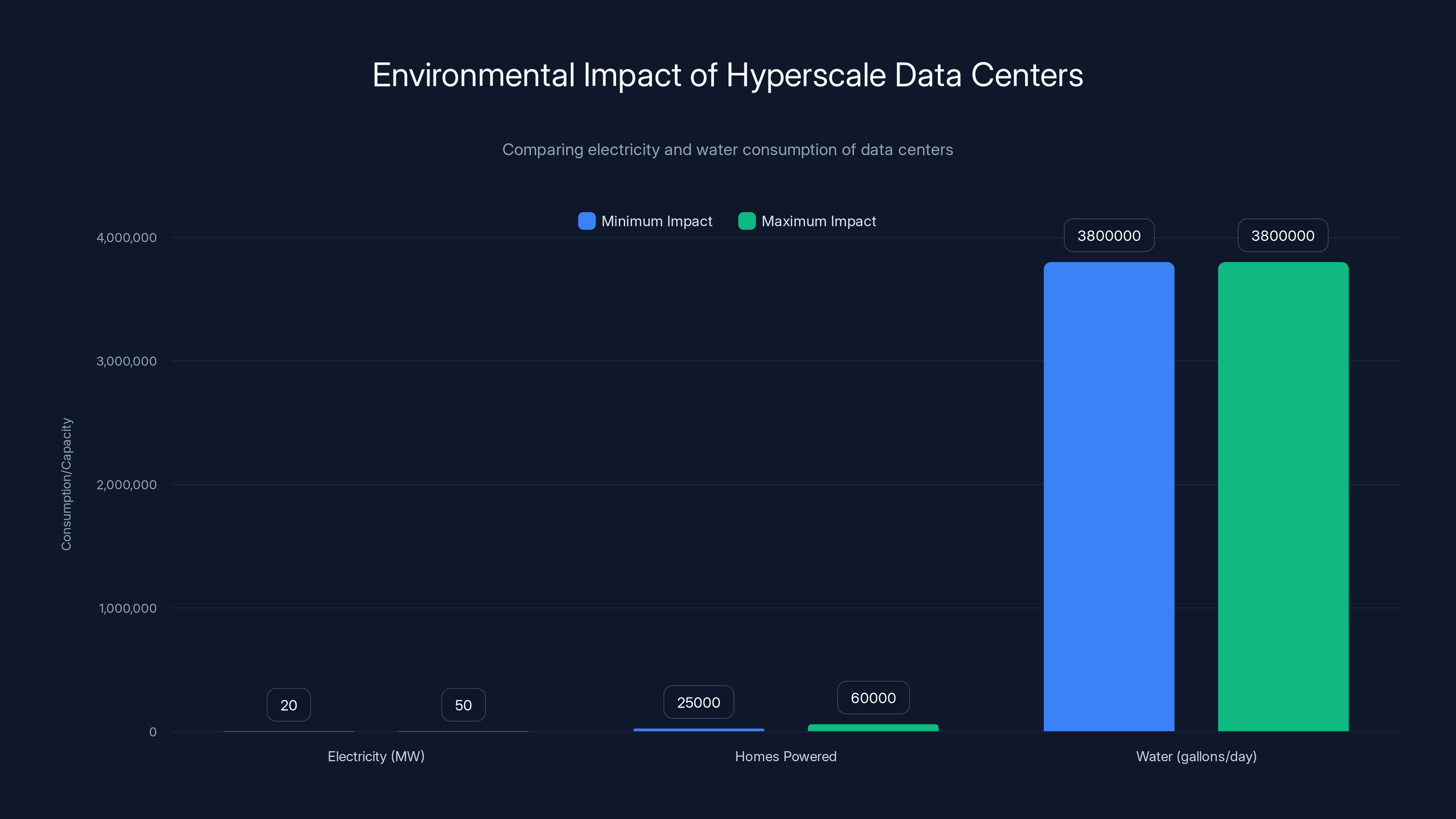

The environmental impact is substantial and measurable. A single hyperscale data center can consume between 20 and 50 megawatts of continuous power, equivalent to the electricity needs of 25,000 to 60,000 homes. Water consumption is equally staggering. Meta's proposed data center in Wisconsin was projected to use 3.8 million gallons of water daily. Microsoft's underwater data center experiments exist precisely because traditional cooling methods consume so much water that coastal locations become impractical.

These facilities also represent a tangible symbol of AI's economic impact. They're where Chat GPT requests are processed, where training data is stored, where the computational infrastructure that's disrupting industries literally lives. Communities see them not as abstract technology but as massive industrial facilities with real local consequences.

The political resistance started in Virginia, where communities near Loudoun County—which hosts more data center capacity than any state in the nation—began organizing against further expansion. Environmental groups, local governments, and resident coalitions have successfully blocked or delayed dozens of projects. In Iowa, environmental concerns delayed a Google data center project. In Wisconsin, Meta faced fierce opposition over water consumption.

What's driving this resistance isn't just environmental concerns, though those matter enormously. It's also economic anxiety. Communities see data centers as capital-intensive infrastructure that creates relatively few permanent jobs. A hyperscale data center might employ only 200-300 people for ongoing operations, despite consuming resources at the scale of a city. The construction jobs are temporary. The economic benefits flow largely to distant corporations and shareholders, not to local communities.

The AI angle adds another layer. Residents understand that these data centers will power systems designed to automate jobs, displace workers, and fundamentally alter labor markets. The same facility powering Chat GPT might soon be used to train a model that replaces customer service workers, radiologists, or software engineers. This creates a psychological resistance that's harder to overcome with economic arguments.

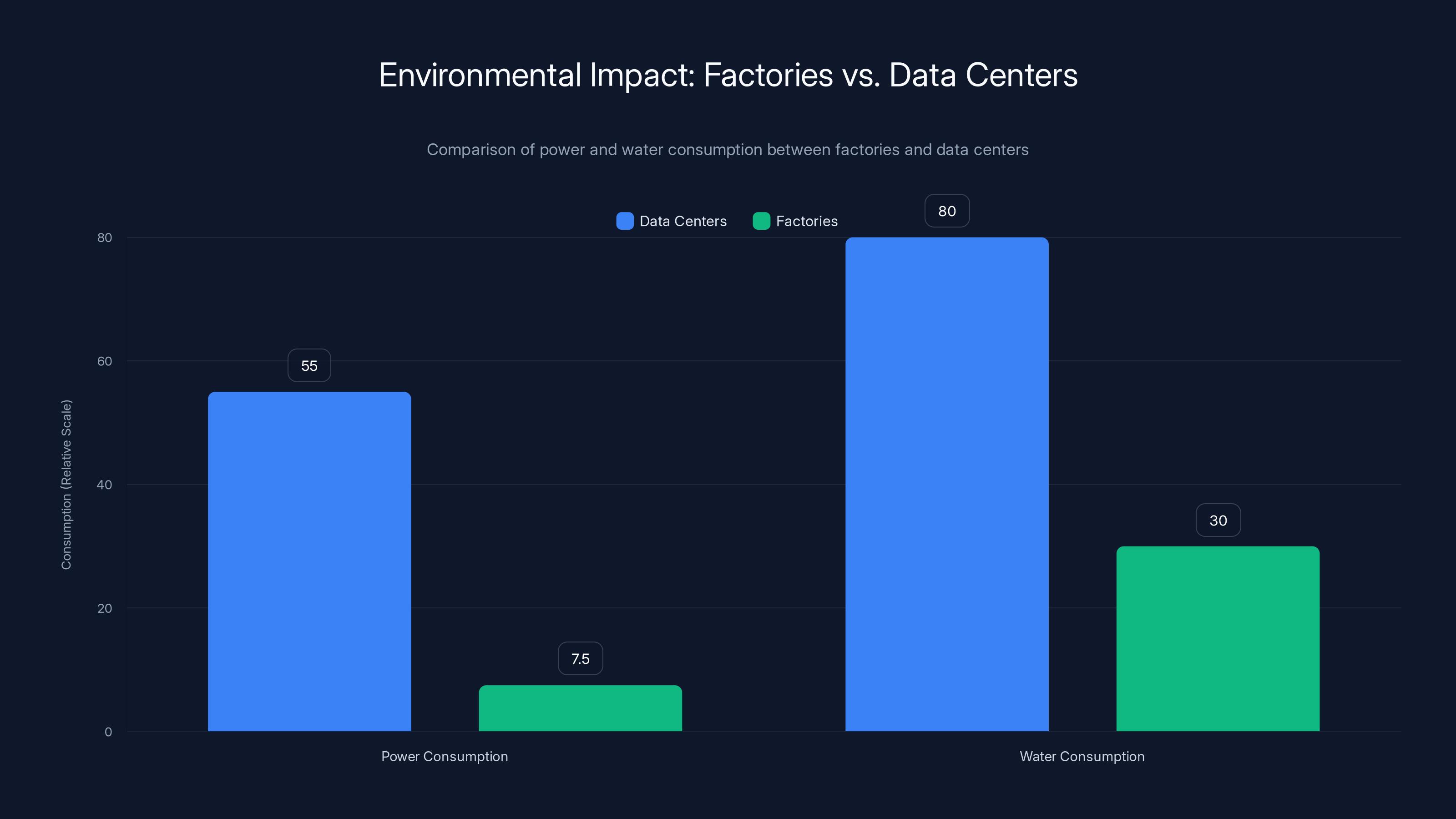

Data centers consume significantly more power and water compared to factories, highlighting their larger environmental footprint. Estimated data.

The Server Factory Phenomenon: Why Manufacturing Gets a Pass

While data center projects face organized opposition, server factories and component manufacturing facilities are getting approved with stunning ease. Compal's Taylor facility is just one example among dozens.

The contrast is striking because factories should arguably face more scrutiny, not less. Industrial manufacturing has genuine environmental impacts: emissions, waste streams, chemical use, transportation. But factory proposals are moving through local approval processes with minimal public attention, substantial tax incentives, and virtually no organized resistance.

Several factors explain this dynamic. First, factories create jobs in a way that data centers don't. When Compal announced plans for 900 jobs in Taylor, that number resonated with city council members and residents. Contrast this with a data center's typical employment: 200-300 operational positions, mostly highly technical roles. The Taylor factory would be the second-largest employer in the city. That's not theoretical economic benefit; that's concrete, visible impact on a community with 16,000 people.

Second, the manufacturing sector carries cultural weight. Americans understand factories. There's a narrative around manufacturing renaissance, bringing jobs back from overseas, rebuilding local economies. The decline of American manufacturing is a political issue that resonates across the political spectrum. When a Taiwanese company says it wants to build servers in the United States, that fits a popular narrative about reshoring and economic revitalization.

Third, and this is crucial, most communities don't understand that these factories are part of the data center ecosystem. City records describing Compal's Taylor facility simply noted "servers" among various products. The connection to hyperscale data centers wasn't explicit. Residents and officials didn't have the mental framework to connect a server factory to the AI infrastructure boom they were increasingly skeptical about.

Fourth, factory developers have significant advantages in the political process. They can credibly claim that their facility creates stable, lasting employment. They can offer community benefits packages. They can argue that without U.S. manufacturing capacity, the entire supply chain becomes dependent on overseas production, exposing America to geopolitical risk and supply disruptions. These arguments carry weight with elected officials.

The Economics of Incentives: Why Cities Are Rolling Out the Welcome Mat

Taylor offered Compal nearly

The logic is straightforward from a municipal finance perspective. A 900-job facility means increased property tax revenue, sales tax revenue, and payroll tax revenue (in states that have it). Over a 10-year period, that could easily total

Beyond the direct fiscal impact, there's a broader economic theory at play. Manufacturing facilities attract supply chain investments. If Compal's factory is in Taylor, then businesses that supply components, provide logistics, handle staffing, and provide specialized services will locate nearby. One company becomes a cluster. A cluster becomes an economic ecosystem.

Taylor specifically is trying to develop this strategy. Located between Austin and Houston, with transportation infrastructure connecting it to Dallas, the city is positioned to become part of a data center and data center supply chain hub. If the strategy works, Taylor transitions from a small town to a regional manufacturing and technology center.

This economic logic is compelling. It's why mayors and economic development directors are enthusiastically supporting factory projects. Mayor Dwayne Ariola's comment about another "home run" reflects genuine excitement about economic development, not indifference to environmental or social concerns.

But there's an undersized elephant in the room: what happens when the data center boom moderates? Manufacturing facilities are built to last decades, but demand cycles are often measured in years.

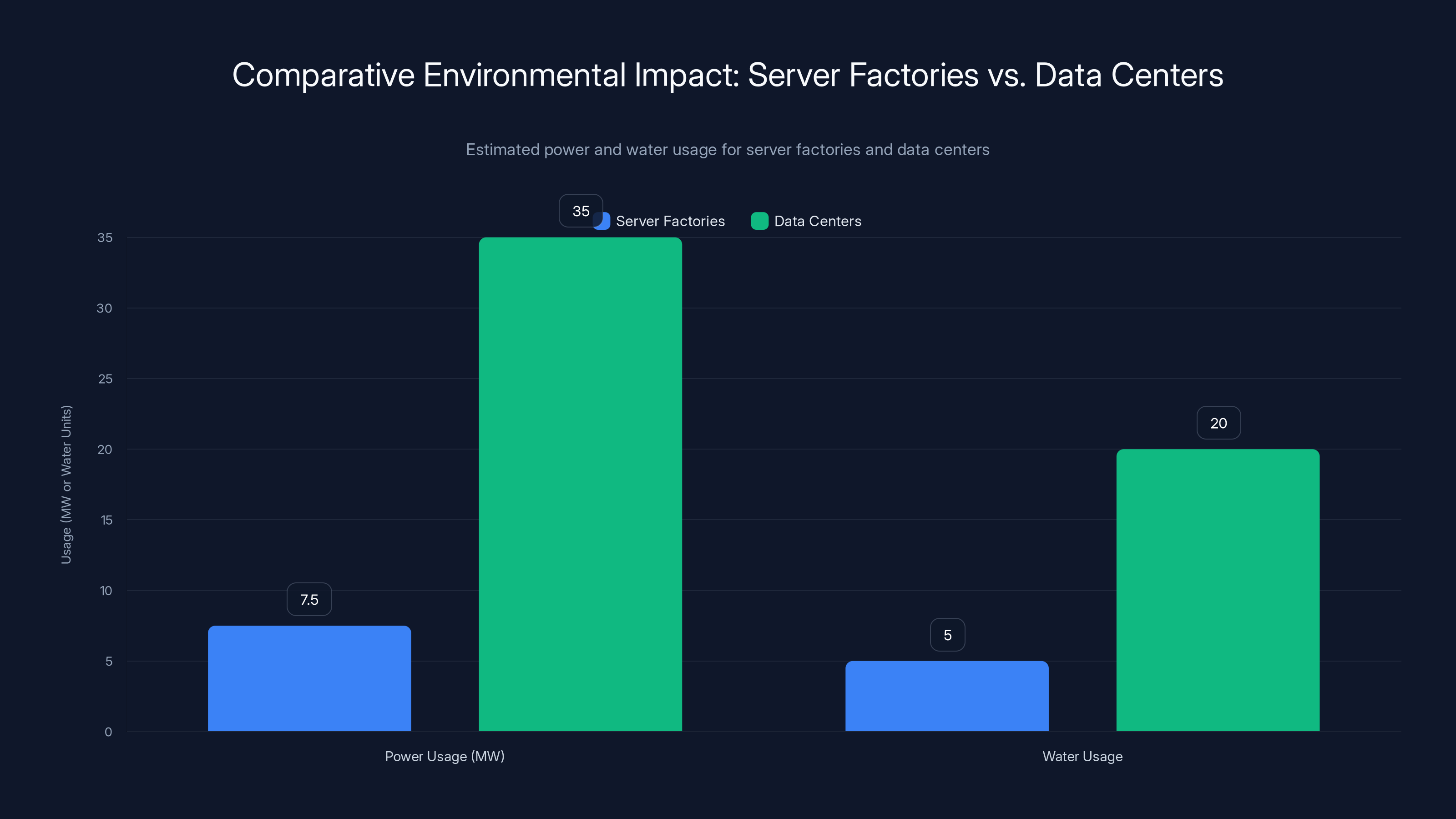

Data centers typically consume more power (20-50 MW) and water compared to server factories (5-10 MW), highlighting their larger environmental footprint. Estimated data.

The Supply Chain Vulnerability: A Critical Chokepoint

Andy Tsay, who studies global trade at Santa Clara University, made an observation that should make strategists in both the data center and manufacturing industries uncomfortable. "At some point," Tsay says, "people are going to figure out what the critical factory is that can bring all the data centers to their knees, and they will go after that."

This observation points to a fundamental supply chain reality: the infrastructure for hyperscale data centers isn't infinitely distributed. It passes through specific bottlenecks.

Think about the supply chain for a moment. You need servers. Those servers need power distribution units, cooling systems, cabling, and software. You need transformers, capacitors, and specialized semiconductors. Many of these components come from a relatively small number of manufacturers.

There's no single factory that supplies everything, but there are critical nodes. If a major server manufacturing facility goes offline—due to protests, regulatory action, or supply chain disruption—data center construction across the entire country could slow. If a facility that manufactures power distribution systems or cooling components shuts down, the impact ripples across every hyperscale deployment.

This is why Tsay's observation resonates. The data center industry has successfully centralized and optimized its supply chains for cost and efficiency. That's economically rational. But it creates vulnerability.

A coordinated campaign targeting supply chain facilities could have asymmetrical impact. Data center protests require fighting battles in dozens of different jurisdictions, with different regulatory frameworks, different political dynamics, and different community concerns. Supply chain protests could theoretically target just a handful of critical facilities.

The data center industry understands this risk implicitly. It's one reason why there's been a push to diversify manufacturing locations. Building facilities in Texas, Arizona, Ohio, and elsewhere reduces the risk that opposition in any single location could cripple the entire supply chain.

But this strategy has limits. You need critical mass in manufacturing capacity. And you need it in specific locations with access to skilled labor, transportation infrastructure, and supply chain proximity.

The Opacity Problem: How the Supply Chain Stays Invisible

When Pamela Griffin reviewed city council materials for the Compal facility, the documents described the company's intentions broadly as making "servers, smart home devices, automotive electronics, and more." That list obscures more than it reveals.

Compal is a Taiwanese multinational with operations spanning consumer electronics, automotive systems, and cloud infrastructure. The company makes components for everybody from Apple to Dell. A server factory in Taylor could theoretically serve multiple markets.

But the subsidiary established for the Taylor facility, "Compal USA Technology," was created specifically to expand server operations in the United States. The company's announcements emphasized "enterprise and cloud infrastructure needs." The facility is unambiguously intended for data center supply.

Yet nowhere in the city council materials was this connection explicit. A resident reviewing the public record wouldn't immediately understand that voting to approve this factory meant voting to enable data center expansion.

This opacity is partly intentional. It's not in anyone's interest to highlight the data center connection. The company benefits from appearing to be a generic technology manufacturer rather than explicitly part of the data center supply chain. Local economic development officials benefit from appearing to recruit diverse manufacturing, not specifically data center infrastructure. City council members benefit from framing a vote as supporting American manufacturing and job creation, not facilitating AI infrastructure expansion.

But the opacity also reflects genuine complexity. Supply chains are complicated. Companies do have diversified operations. A factory can simultaneously serve data center customers and other markets. The complexity is real, not invented.

This creates a challenge for communities trying to make informed decisions. The information they need to understand a project's true scope and implications often isn't readily available in the public record. It requires investigative work, research, and expertise that most community organizations don't have.

Griffin understood this problem directly. She knew Compal made servers. She suspected the Taylor facility was for data center supply. But she didn't have definitive proof without access to corporate strategic plans and customer contracts. Operating from incomplete information, she and other activists had to make a strategic choice: allocate limited resources to the factory opposition or focus on the data center fights where the connection was explicit and documented.

Hyperscale data centers consume between 20-50 MW of power, equivalent to powering 25,000-60,000 homes, and can use up to 3.8 million gallons of water daily. Estimated data based on typical usage.

The Resource Constraint: Why Activists Can't Fight on All Fronts

Masheika Allgood, founder of All AI Consulting, has been advising community groups opposing data centers. She articulates the core challenge plainly: "These are difficult, exhausting fights."

Fighting a data center proposal requires sustained effort. You need to understand environmental impact, power consumption, water use, and land use implications. You need to file public records requests, analyze environmental review documents, and potentially hire expert consultants. You need to organize community members, build political pressure, and prepare testimony for hearings. You need legal representation if the fight goes to court.

All of this requires resources: time, money, expertise, and political capital. Community opposition groups are typically funded by small donations from residents and perhaps local environmental organizations. They're competing against companies with sophisticated government relations teams, lawyers, public relations firms, and unlimited budgets.

Given these resource constraints, strategically focusing on the most winnable fights makes sense. A data center opposition campaign might attract media attention, inspire other communities to organize, and potentially shift political opinion. A factory opposition campaign would require similar resources but might appear to be opposing job creation—politically toxic in most communities.

Griffin's calculus is rational from a strategic perspective: focus on the data centers, let the factories pass, and hope that stopping data centers eventually reduces demand for factory capacity. But from a supply chain perspective, it's a vulnerability. Factories are easier targets than data centers, and disrupting factory capacity would be more effective at slowing data center expansion than blocking individual facilities.

The industry understands this asymmetry. It's built into the strategy of decentralizing supply chain opposition through dozens of small approvals rather than centralizing it in a handful of massive data center battles.

Geographic Concentration: Why Texas and a Few Other States Dominate

Data center and data center supply chain investment isn't evenly distributed across America. It's concentrated in specific regions with particular advantages: Texas, Virginia, Arizona, Ohio, and a handful of others.

Texas has multiple advantages. The state has deregulated electricity markets, meaning power prices can be lower and more flexible than in regulated states. Texas has abundant wind power, which appeals to companies making sustainability commitments. The state has substantial water resources in some regions, though not others. Texas also has no state income tax, reducing overall business costs. And politically, Texas welcomes industrial development with fewer regulatory barriers than many states.

Virginia dominates existing data center capacity because of historical accidents of geography and policy. Loudoun County became a data center hub in the 1990s and 2000s, creating a self-reinforcing network effect. Once critical mass of facilities existed, suppliers located nearby, expertise concentrated in the region, and customers expected to deploy there. That historical advantage is hard to overcome.

Arizona and Ohio are becoming secondary hubs. Arizona offers abundant solar power and lower land costs. Ohio is pursuing an explicit strategy to develop semiconductor and manufacturing capacity as part of its industrial revitalization.

Within these states, facilities concentrate near power generation capacity, water sources, and transportation infrastructure. In Texas, much of the development clusters near Austin and Houston. In Virginia, the Northern Virginia corridor dominates. These aren't random distributions; they reflect real infrastructure requirements.

This geographic concentration creates a vulnerability for communities. If you're located in Austin, Houston, Northern Virginia, or Phoenix, the impact is direct and unavoidable. Data center and supply chain development will reshape your region's growth trajectory. If you're elsewhere, these conflicts feel distant and abstract.

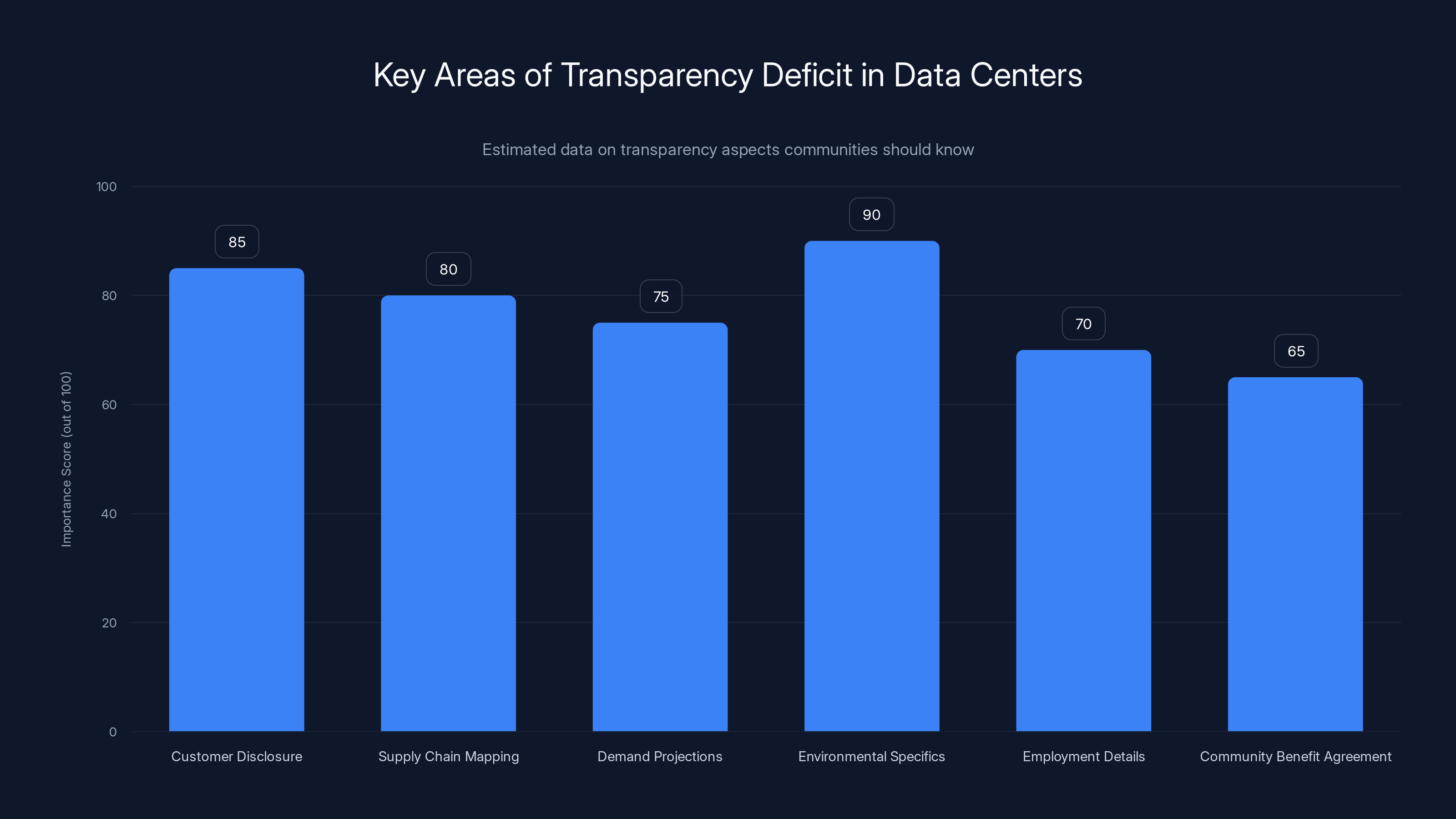

Environmental specifics and customer disclosure are the most critical transparency aspects for communities, highlighting a significant transparency deficit. (Estimated data)

The Job Creation Narrative: Promise vs. Reality

Compal's promise of 900 jobs is substantial and genuine. The company appears committed to building a real manufacturing facility that will employ significant numbers of people. This is different from the data center narrative, where companies promise economic benefits that often don't materialize at promised scales.

For a city like Taylor, 900 permanent jobs represents significant economic impact. The facility would create construction jobs during the build-out phase, operational jobs once open, and ancillary jobs through supply chains and services. The economic multiplier effect could generate additional employment throughout the region.

But there are important caveats. First, manufacturing employment doesn't necessarily mean high wages or benefits for all positions. Server manufacturing includes skilled technical work, but it also includes assembly, quality control, and logistical roles that might pay closer to median manufacturing wages than to the premium tech salaries that communities might expect.

Second, manufacturing is increasingly automated. A 900-job facility today might become a 600-job facility in five years as automation improves. The long-term employment impact could be significantly lower than initial projections.

Third, the jobs require training and workforce development. Compal will presumably work with local and state agencies to develop training programs, but this requires investment and time. Not every resident of Taylor can instantly transition into a manufacturing role, even with training.

Fourth, and this gets less attention, what happens when the data center boom moderates? Server manufacturing demand is directly tied to data center growth. If data center construction slows due to saturation, regulatory barriers, or economic recession, server manufacturing demand could collapse. A facility built to serve the 2024-2026 boom could face significant excess capacity by 2028 or 2030.

Communities pursuing manufacturing facilities need to think carefully about what happens after the initial boom. Economic development that's entirely dependent on a single customer segment or technology trend is inherently fragile.

The Regulatory Gap: Why Factories Escape Scrutiny

Factory projects go through environmental review processes just like data centers do. They require permits, they need to comply with zoning regulations, and they're subject to environmental impact assessment laws.

But the threshold for requiring serious environmental review often differs. A hyperscale data center, with its massive power consumption and water use, typically triggers comprehensive environmental impact review. A factory facility, even a large one, might satisfy environmental requirements more easily, particularly if it's located in an industrial zone that's already been environmentally cleared for manufacturing.

Moreover, the environmental impacts of manufacturing are often considered different in kind from data centers. A factory produces tangible goods. Manufacturing is understood as economic activity with environmental externalities that are somehow more "normal" or "acceptable" than data center environmental impacts.

This double standard doesn't make logical sense. A 500,000-square-foot manufacturing facility uses significant energy and water. It generates truck traffic. But the regulatory framework and public perception treat it more leniently than a data center of similar scale.

Part of this reflects the perceived purpose. Factories make things. Data centers are infrastructure for information. There's an intuitive sense that making physical products is more legitimate than powering AI systems—even though the energy and resource consumption might be comparable.

Part of this also reflects timing. Environmental review frameworks were built around manufacturing industries that predate the data center boom. The regulatory structures understand how to evaluate factories in ways that they're still figuring out for hyperscale data centers.

The result is a regulatory gap. Factories that are part of the data center supply chain can move forward without the scrutiny that explicit data center projects face.

Estimated data shows a gradual normalization of data center demand over the next decade, potentially reaching 75% of peak levels by 2033.

The Transparency Deficit: What Communities Should Know

One of Pamela Griffin's key complaints was the lack of transparency about Compal's actual operations and customer base. Even after the facility was approved, detailed information about how the factory would operate, what environmental protections would be in place, and what the relationship to data center customers actually entailed wasn't readily available.

This transparency deficit isn't unique to Taylor. It's systematic across the data center supply chain. Companies have legitimate competitive reasons not to disclose detailed customer information or production volumes. But this means communities can't make fully informed decisions about what they're approving.

A meaningful transparency regime would require:

- Explicit customer disclosure: What percentage of the facility's output will go to data center operators vs. other customers?

- Supply chain mapping: Which specific hyperscale data center operators will the facility serve?

- Demand projections: Based on what growth assumptions is the facility being sized? What happens if those assumptions don't materialize?

- Environmental specifics: What's the facility's annual power consumption? Water consumption? Waste streams?

- Employment details: What percentage of jobs will be skilled technical roles vs. assembly and logistics?

- Community benefit agreement: Beyond tax incentives, what specific commitments is the company making for local employment, training, and economic development?

Many communities don't require this information because they don't know to ask for it. The companies certainly aren't volunteering details that might complicate approvals. And economic development officials benefit from moving projects quickly without excessive due diligence.

Building transparency into the approval process would slow projects down, add costs, and likely reduce the total number of approvals. That's why it's unlikely to happen voluntarily. It requires either regulatory action or organized community pressure.

The Political Economy: Why Industry Wins on Multiple Fronts

The data center and supply chain industries have several structural advantages in political struggles with communities.

First, they control information. Companies understand their own supply chains, environmental impacts, and financial projections. Communities have to piece together information from public records, environmental documents, and investigative research. The information asymmetry is enormous.

Second, they have resources. Industry associations, corporate government relations teams, and professional lobbyists can generate studies, hire consultants, and run political campaigns. Community groups operate on shoestring budgets.

Third, they have allies. Elected officials benefit from economic development. Regional and state governments benefit from job creation and tax revenue. Chambers of commerce and business groups support industrial development. The political coalition supporting factories and data centers is broad and well-resourced.

Fourth, they control the narrative frame. The industry frames data centers as necessary infrastructure for the digital economy and artificial intelligence. It frames opposition as NIMBYism—"not in my backyard" selfishness that ignores broader economic benefits. Factory development is framed as manufacturing renaissance and job creation. These frames resonate with political elites and much of the public.

Communities opposing development are fighting uphill against superior resources, political allies, and narrative control. The surprise isn't that communities are sometimes winning against data centers; it's that they're winning at all.

The supply chain opacity gives industry another advantage. By fragmenting opposition across dozens of small facility approvals rather than organizing around central data center hubs, industry reduces the likelihood of coordinated opposition. Communities can't see the forest for the trees—they're fighting individual facility battles without understanding how the pieces fit together.

The Boom-Bust Risk: What Happens When Demand Normalizes

Every boom cycle is followed by a bust. The data center boom that's driving server factory development will eventually moderate. Probably not in 2025 or 2026, but sometime in the next five to ten years, demand will normalize to levels that don't justify continued massive capacity expansion.

When that happens, communities that have invested heavily in data center and supply chain infrastructure could face significant challenges. A factory built to serve peak-demand scenarios might operate at 60% capacity during normal times. That means fewer jobs, lower tax revenue, and stranded infrastructure assets.

We've seen this pattern before. Manufacturing hubs that boomed during industrial peaks have experienced devastating busts when demand shifted. Textile towns that thrived in the early industrial era became economically devastated when production moved overseas. Steel towns faced similar dynamics. Rust Belt communities across the Midwest experienced generational economic trauma when industrial demand normalized.

Data center supply chain facilities could face similar dynamics. If demand normalizes faster than expected—due to efficiency improvements, market saturation, or regulatory restrictions—communities could be left with massive physical infrastructure designed for a peak that never materializes.

This isn't an argument against economic development. It's an argument for being thoughtful about which development projects to pursue. Communities should ask hard questions about long-term demand sustainability, what alternative uses facilities might have if data center demand drops, and what economic development strategy makes sense if the boom doesn't continue indefinitely.

The Environmental Cost Calculation: Factories vs. Data Centers

Factories do have environmental costs. They use energy, they generate emissions, they might generate waste streams, and they create truck traffic. But the environmental footprint of a server factory is typically smaller than a hyperscale data center at similar scale.

A hyperscale data center with 50 megawatts of power consumption generates a continuous energy footprint equivalent to powering 50,000-60,000 homes. A manufacturing facility of similar size might use 5-10 megawatts, an order of magnitude lower.

Water consumption follows a similar pattern. Data centers need water for cooling. Manufacturing uses water in production, but typically much less than cooling systems.

These differences explain why communities view factories as more acceptable than data centers. From a pure environmental perspective, they're right. A server factory has lower environmental impact per unit of economic output than a data center.

But this creates a perverse incentive structure. Communities are approving the lower-impact facilities while opposing the higher-impact ones. But supply chains are integrated. Without factories producing servers, data center expansion would slow. By approving factories while opposing data centers, communities are actually slowing data center growth—which is the goal. But they're doing it indirectly, through supply chain restriction rather than direct opposition.

From a climate and environmental perspective, this is actually economically sound. If environmental costs are a legitimate concern, making it harder to build the infrastructure that data centers depend on is a legitimate strategy.

But from a community development perspective, it creates a risk. Communities are betting that restricting data center growth through supply chain constraints will ultimately slow development in their region. But they're not directly controlling that outcome. If one region slows data center development, another region might accelerate it. And if supply chain facilities relocate to other communities or countries, the environmental costs might increase (due to longer shipping distances and less efficient facilities) rather than decrease.

Strategic Implications: What's Next for Data Center Development

The dynamic between data center opposition and supply chain acceptance is creating pressure for industry adaptation.

One direction is geographic dispersion. Rather than concentrating data center and supply chain development in obvious clusters like Northern Virginia or Austin, the industry is experimenting with dispersed deployments. This reduces the likelihood that opposition in any single region will substantially impact overall capacity.

Another direction is technical innovation. More efficient data centers, liquid cooling systems, and renewable energy integration can reduce environmental footprints, potentially reducing opposition. But these technologies cost more and require longer development cycles than opposition builds. The industry is pursuing them, but not fast enough to immediately address community concerns.

A third direction is narrative and political sophistication. The industry is investing heavily in public relations, lobbying, and political relationships. Rather than hoping opposition will disappear, it's actively managing it.

A fourth direction is supply chain resilience. Companies are pursuing manufacturing diversification, reducing dependence on any single geographic location or supplier. This is partly driven by geopolitical concerns (China's importance to global supply chains creates risk), but it also addresses opposition risk. Multiple suppliers in multiple locations are harder to disrupt through political opposition than concentrated supply chains.

Communities pursuing data center restrictions are creating economic pressure for supply chain diversification, which ironically might ultimately spread data center and manufacturing infrastructure to more locations rather than concentrating it. This could increase overall environmental impact even as it reduces impact in specific communities.

The Path Forward: Building Informed Communities

The fundamental challenge is that communities making decisions about data centers and supply chain infrastructure often lack the information, expertise, and resources to make fully informed choices.

Improving this situation requires several changes. First, transparency requirements need to become standard. Public documents describing manufacturing projects should explicitly disclose customer relationships, including data center supply connections. Companies should be required to provide detailed environmental and labor information as a condition of approvals and tax incentives.

Second, communities need resources. Environmental organizations, universities, and public interest groups could provide expert analysis of proposed facilities without charging communities for it. This could level the information asymmetry between well-resourced corporations and underfunded community groups.

Third, community organizing needs to become more sophisticated about supply chains. Rather than seeing individual facility battles as separate campaigns, organizers should understand supply chains holistically. Targeting critical chokepoints could be more effective than opposing individual data centers.

Fourth, communities should think longer-term about economic development. Instead of evaluating individual projects in isolation, communities should develop integrated economic development strategies that consider long-term sustainability, environmental impact, and whether boom-bust risk is acceptable.

Fifth, regional coordination could increase effectiveness. Rather than individual cities competing to attract manufacturing facilities by offering the largest tax incentives, regions could coordinate to increase their bargaining power. A region saying "we'll collectively approve 5 server factories" has more leverage than individual cities competing to approve factories.

None of these changes will happen without pressure. The current system works well for companies and for communities hoping for short-term economic gains. Meaningful change requires organized community demand.

The Bigger Picture: Rethinking AI Infrastructure

The data center and supply chain opposition reveals something broader about how we're thinking about AI infrastructure.

We're building massive physical infrastructure to power AI systems without having addressed fundamental questions about whether we want those systems, what they're for, and whether their benefits justify their costs. We're making infrastructure decisions that lock in technological trajectories for decades.

Data centers are powerful symbols, but they're just one part of AI infrastructure. Semiconductor manufacturing, training data collection, labor systems for content moderation and data labeling, and environmental systems affected by energy demand are all part of the infrastructure required for modern AI.

Community opposition to data centers is partly NIMBYism. People don't want massive facilities in their backyards, particularly if local benefits are limited and local costs are high. But opposition also reflects deeper skepticism about the whole AI project. Communities are asking: do we want our electricity, water, and industrial capacity dedicated to training and running AI systems?

That's a legitimate question, even if communities can't always articulate it in those terms. And it's being asked with increasing frequency and sophistication.

The industry's response—fragmenting opposition through supply chain opacity and geographic dispersion—is effective but ultimately unsustainable. Eventually, communities will connect the dots and understand that approving supply chain infrastructure means approving the data centers and AI systems that infrastructure serves.

When that happens, the dynamic could shift. Communities might start blocking factories as a way to slow data center development. Activists could coordinate on supply chain opposition as well as facility opposition. The political economy could change.

The current window, where supply chain facilities move forward with minimal opposition, won't last forever. Smart communities are preparing for that shift now.

Conclusion: The Supply Chain as Forgotten Battlefield

Pamela Griffin's situation in Taylor, Texas encapsulates a broader paradox in how we're approaching the infrastructure required for artificial intelligence and cloud computing. Communities are increasingly organized and vocal about opposing data centers, the visible infrastructure that powers AI systems. But they're simultaneously approving and incentivizing the factories that manufacture the components those data centers depend on.

This creates a strategic vulnerability for data center opposition movements. Without server factories, data center expansion would slow significantly. But supply chain facilities are moving forward with minimal scrutiny, minimal opposition, and substantial public support.

It also creates strategic opportunity. Supply chains, by their nature, concentrate through critical chokepoints. Targeting those chokepoints could be more efficient than fighting individual data center battles. A coordinated campaign focused on a handful of critical server manufacturing facilities could have broader impact on data center expansion than dispersed opposition across dozens of individual data centers.

But taking advantage of that opportunity requires resources, coordination, and sophistication that community opposition movements currently lack. Activists are spread thin fighting the most visible facilities. They don't have capacity to simultaneously develop supply chain expertise and conduct detailed research on which facilities are actually critical to data center expansion.

The industry, meanwhile, is using this window strategically. It's building supply chain capacity across multiple regions, creating redundancy that will make future disruption harder. It's maintaining opacity about supply chain relationships, making it difficult for communities to understand connections between facilities and data center development. It's offering attractive incentives to communities hungry for economic development, building local political support for manufacturing.

When the current boom eventually moderates, when demand for data center capacity normalizes, communities will face different circumstances. The infrastructure decisions made today will have locked in development patterns for decades. Facilities will exist regardless of whether demand justifies them.

The question facing communities now is whether to make those decisions deliberately, with full understanding of their implications, or to let them happen through fragmented approvals, opacity, and the path of least resistance.

Griffin chose to focus on the most visible battle: the data center projects threatening her community directly. That's a rational choice given limited resources. But it illustrates the broader challenge: supply chain infrastructure is being built to serve data centers that communities don't want, and few people are paying attention to it.

That attention deficit won't last forever. Eventually, communities will realize that opposing data centers while approving supply chain infrastructure is backwards. When that shift happens, the political and economic dynamics of data center and AI infrastructure development could change substantially.

The factories that are being approved today with minimal opposition might face serious scrutiny tomorrow. The communities that are offering massive tax incentives might regret those decisions. And the supply chains that the data center industry is counting on might become the battlefield where data center expansion is actually contested.

Until then, the paradox continues: factories sail through approvals while data centers face resistance, even as factories exist primarily to serve data center growth. It's a strategic advantage for the industry, a resource constraint for opposition movements, and a risk for communities hoping that fragmenting infrastructure approval processes will somehow spare them from the broader transformation that data centers and AI represent.

FAQ

What is a data center supply chain, and why does it matter?

A data center supply chain encompasses all the manufacturers and suppliers that produce the components, equipment, and infrastructure required to build and operate hyperscale data centers. This includes server manufacturers like Compal, power distribution equipment suppliers, cooling system providers, and specialized component manufacturers. The supply chain matters because data center expansion is impossible without supply chain capacity. Restricting supply chain development is potentially more effective at limiting data center growth than opposing individual facilities.

How are server factories different from data centers in terms of environmental impact?

Server factories typically have lower environmental footprints than data centers at similar scale. While data centers consume 20-50 megawatts of continuous power and require substantial cooling water, manufacturing facilities usually consume 5-10 megawatts and less water. However, factories still have environmental costs including energy use, emissions, waste streams, and truck traffic. Communities often perceive factories as more acceptable than data centers, even though both have measurable environmental impacts.

Why are communities approving factories while opposing data centers?

Communities approve factories for several reasons: they create more visible job opportunities (900+ positions vs. 200-300 for data centers), manufacturing has cultural resonance around economic development and American revitalization, and the connection between factories and data center supply chains often isn't transparent to residents and officials. Additionally, factory opposition could be framed politically as opposing job creation, which is unpopular. Communities are essentially approving infrastructure that enables data center development without fully understanding that connection.

What is a supply chain chokepoint, and could activists exploit it?

A supply chain chokepoint is a critical facility or supplier where disruption would significantly impact downstream production. For data centers, this might include major server manufacturing facilities or suppliers of specialized power conversion equipment. Activists could theoretically target these chokepoints more efficiently than fighting individual data center battles. However, this strategy requires resources, coordination, and expertise that community opposition groups typically lack, and it could be complicated by industry efforts to diversify supply chains.

How does the lack of transparency about supply chain relationships affect communities?

Opacity about supply chain relationships prevents communities from making fully informed decisions about manufacturing facilities. City documents describing a facility might list multiple product types without explicitly stating the percentage allocated to data center supply. This prevents residents and officials from connecting individual factory approvals to broader data center expansion. Requiring explicit disclosure of customer relationships, supply chain roles, and data center supply percentages would help communities understand what they're approving.

What should communities consider when evaluating manufacturing facility projects?

Communities should request detailed information about: customer relationships and percentage allocation to data center supply, long-term demand sustainability and sensitivity to market cycles, environmental specifics including power and water consumption, detailed employment projections and job quality, workforce training requirements, and community benefit agreements beyond tax incentives. Communities should also think about what happens if demand normalizes faster than expected and whether the facility could serve alternative uses. Long-term economic sustainability should take precedence over short-term job creation promises.

Key Takeaways

- Data center opposition is well-organized and visible, while supply chain facility opposition is minimal and fragmented, creating asymmetric pressure on the industry

- Communities are approving manufacturing facilities without understanding their role in enabling data center expansion, due to opacity and information gaps

- Supply chain facilities offer genuine job creation benefits that data centers don't, making them politically harder to oppose despite serving data center growth

- The supply chain has potential chokepoints that activists could target more efficiently than individual facility battles, but only with coordination and resources

- Communities face boom-bust risk if manufacturing capacity built for peak data center demand becomes economically stranded when demand moderates

- Transparency requirements and regional coordination could improve community decision-making, but change requires organized pressure

- The supply chain vulnerability is a window that won't stay open indefinitely; communities will eventually recognize that approving factories enables data center development

- Long-term economic development strategy matters more than short-term incentives, particularly in boom-bust industries

Related Articles

- The AI Adoption Gap: Why Some Countries Are Leaving Others Behind [2025]

- Harvey Acquires Hexus: Legal AI Race Escalates [2025]

- Intel Core Ultra Series 3 Launch Delayed by Supply Crunch [2025]

- How Davos Became Silicon Valley's Mountain Summit [2025]

- Meta Pauses Teen AI Characters: What's Changing in 2025

- Apple's AI Wearable Pin: What We Know and Why It Matters [2025]

![Data Center Backlash Meets Factory Support: The Supply Chain Paradox [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/data-center-backlash-meets-factory-support-the-supply-chain-/image-1-1769427422513.jpg)