Intel Core Ultra Series 3 Launch Delayed by Supply Crunch: What You Need to Know

Intel just dropped some uncomfortable truth on the tech industry. The company's latest earnings report reveals a production crisis that's about to hit consumer processor availability hard. While Intel's data center business is thriving, consumer chips like the upcoming Core Ultra Series 3 are being squeezed out of production pipelines. This isn't just a minor hiccup. It's a strategic triage decision that could reshape how you buy your next laptop or desktop PC.

Here's what's happening: Intel can't manufacture enough chips to meet overall demand. So the company is doing what any sensible business would do. It's allocating its limited production capacity to the divisions that print the most money. Data center chips generate more revenue per unit and face stronger demand from AI-focused enterprises. Consumer processors, despite being incredibly popular, are getting deprioritized. Intel CFO David Zinsner was remarkably transparent about this on the company's earnings call. "We're prioritizing internal wafer supply to data center," he explained, adding that Intel is "shifting as much as we can over to data center to meet the high demand."

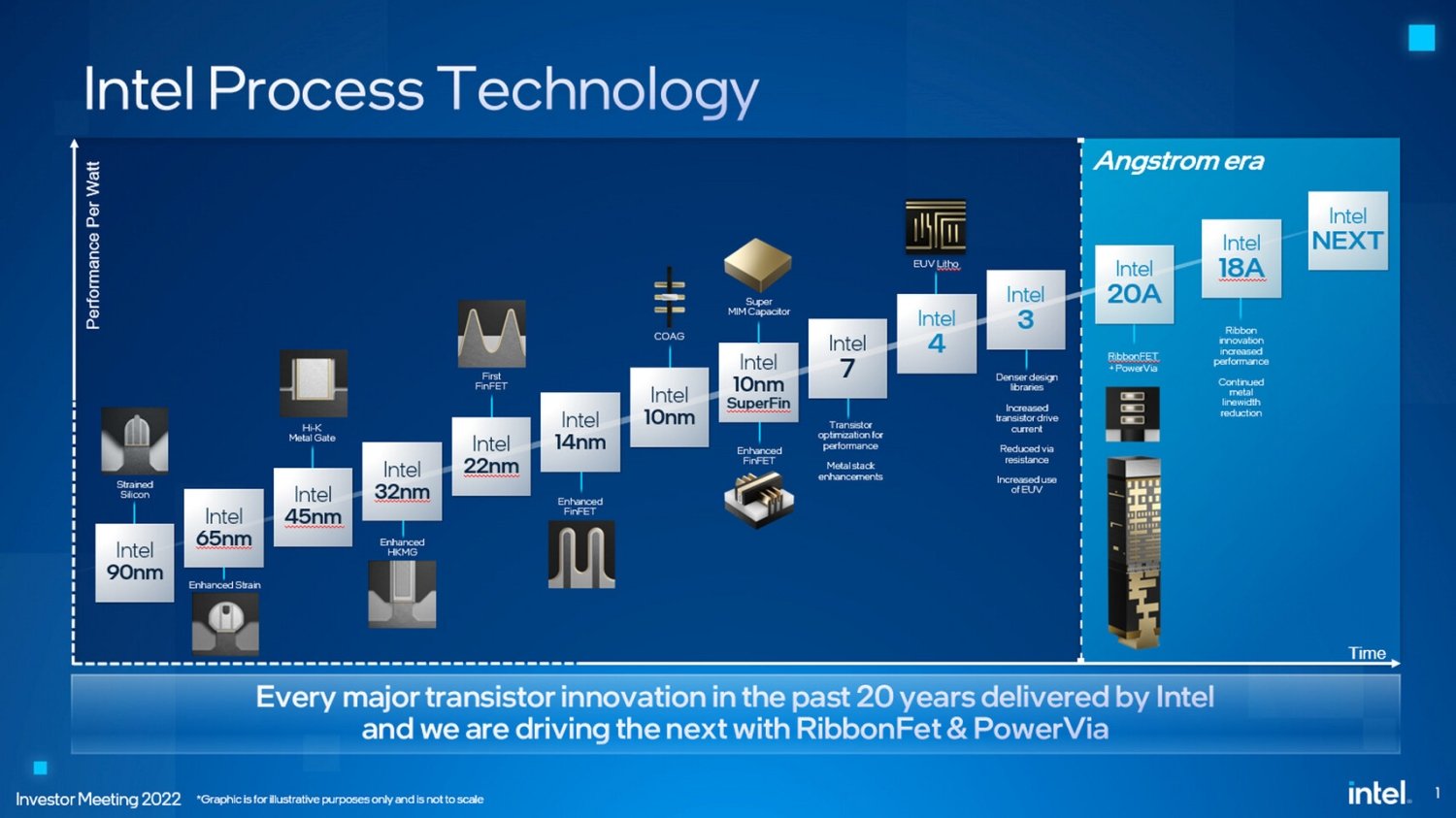

The timing couldn't be worse. Intel is preparing to launch the Panther Lake processors, codenamed Core Ultra Series 3, which industry analysts have been calling the most promising consumer chip generation in years. But instead of ramping production to capitalize on this momentum, Intel is facing a perfect storm. Manufacturing yields for its cutting-edge 18A process are still below acceptable levels. Supply contracts are already spoken for. And the company's earnings show exactly where the pressure points are.

What does this mean for you? Potential shortages of premium consumer processors. Higher prices when stock does arrive. And longer wait times for the exact CPU configuration you want. For a company trying to claw back market share from AMD, this is an extraordinarily frustrating situation. But understanding the numbers behind this decision reveals why Intel really had no other realistic choice.

TL; DR

- Intel's data center business grew 9% last quarter while consumer chips dropped 7%, forcing Intel to prioritize server chip production

- Core Ultra Series 3 consumer processors face potential shortages as Intel shifts manufacturing capacity to more profitable data center divisions

- 18A process yields remain below target at roughly 10% initially, though improving 7-8% monthly, limiting overall production capacity

- Q1 2025 expected to be the supply trough, with improvement expected in Q2 as yields ramp and new capacity comes online

- Intel shifting from internal to external manufacturing for consumer chips, outsourcing more Core Ultra Series 3 production to third parties

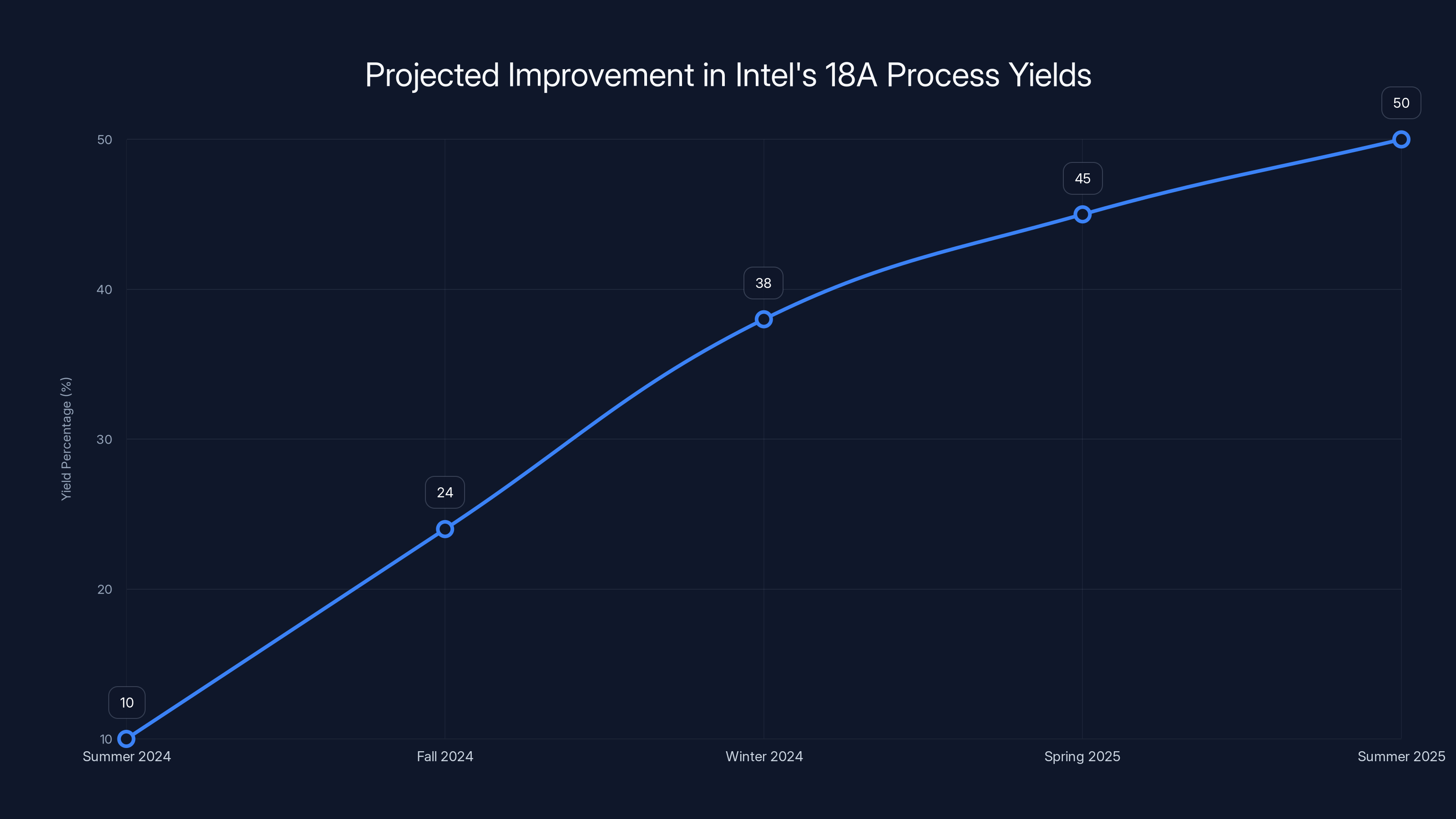

Intel's 18A process yields are projected to improve from 10% in Summer 2024 to around 50% by Summer 2025, facilitating better chip availability. Estimated data.

The Earnings Numbers That Tell the Real Story

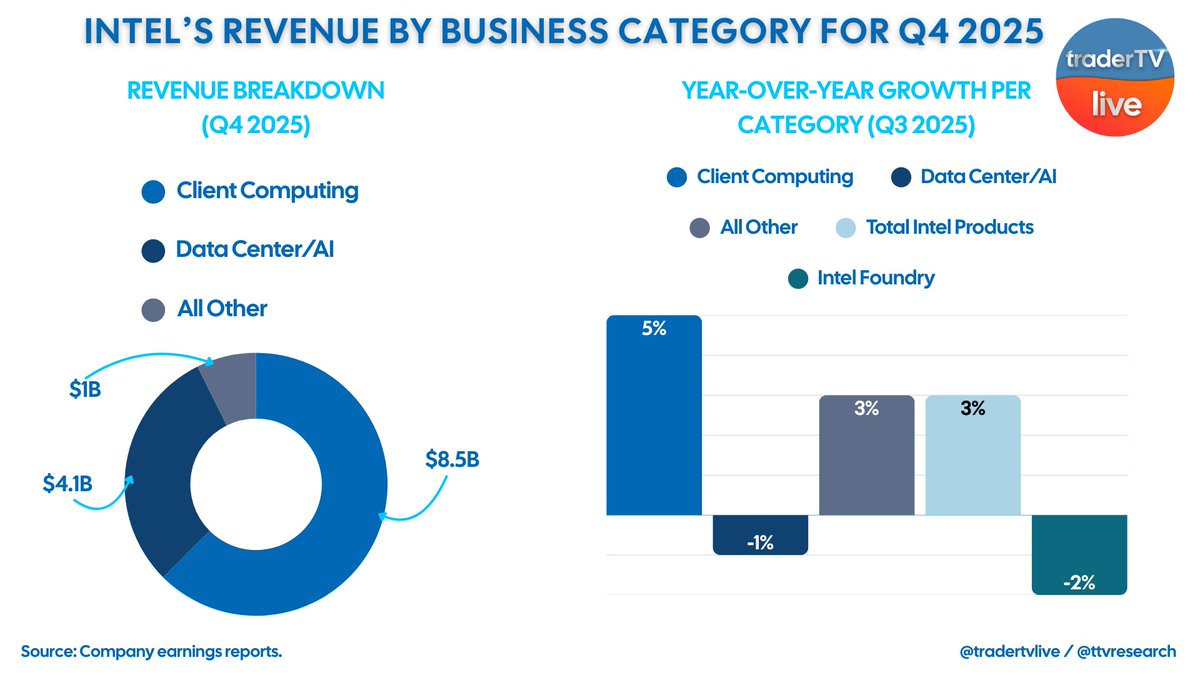

Intel reported Q4 2025 financial results that looked deceptively okay on the surface. Year-over-year revenue was essentially flat, sliding from

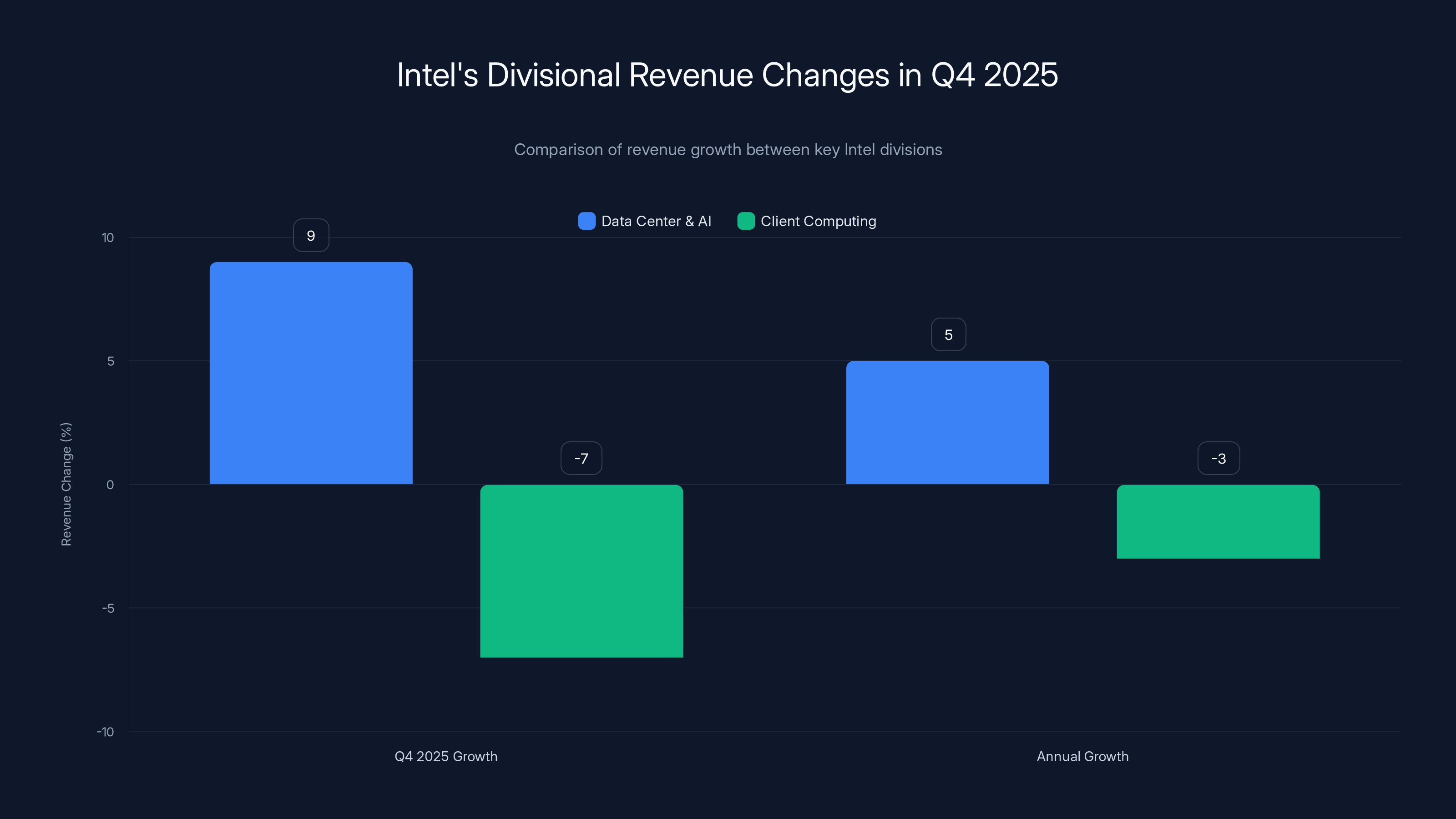

Look at the divisional breakdown, and the story becomes crystal clear. Intel's data center and AI products surged 9% for the quarter and 5% for the entire year. That's the growth story investors want to hear. Meanwhile, the client computing group—the division that sells processors to everyday consumers and small businesses—contracted 7% for the quarter and 3% for the year.

This isn't a marginal difference. It's a 16-percentage-point divergence between the two most important divisions. For a company with $52.9 billion in annual revenue, that gap represents billions of dollars. When you're allocating scarce manufacturing resources, that's the signal that matters most.

Intel reported that Q4 2025 revenue came in at

Investor relations VP John Pitzer had said the previous month that Intel would happily sell significantly more Lunar Lake and Arrow Lake Core Ultra Series 2 consumer chips if production allowed. The same went for Granite Rapids server processors. "Demand is there," he essentially said. "We just can't make enough." That's a rare position for Intel in recent years, and it explains the desperation reflected in management's earnings call commentary.

Manufacturing Constraints: The 18A Process Bottleneck

Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan was unusually candid about the company's manufacturing challenges. "Yields are in line with our internal plans," he said, "but they are still below what I want them to be." That's corporate speak for "we've got a problem."

The 18A process, Intel's newest manufacturing node, is cutting-edge technology. Smaller transistors mean more powerful chips that use less power. But smaller also means more complex. Initial yields on the 18A process were abysmal. Summer 2024 reporting suggested that just 10% of chips coming off the production line met Intel's quality requirements. Think about that for a second. Ninety out of every hundred chips were either defective or failed to meet specifications. That's an absolutely brutal starting position.

The good news is that Intel is improving yields. The company reports monthly improvements of 7% to 8%. That might sound modest, but it's compound growth. If yields started at 10% and improve 8% monthly, here's how it breaks down:

Applying this formula: Starting at 10% with 8% monthly improvement, yields should reach approximately 15% after three months, and 20% after five months. The math is encouraging, but there's a catch. You need months of manufacturing to build up inventory. Until those yields stabilize significantly higher, every wafer processed is precious. And precious resources get allocated to the highest-value products.

So here's the production bottleneck in plain language. Intel is running advanced chip fabrication plants (fabs) at high utilization. These fabs are incredibly expensive—construction costs run into the billions. You can't just shut them down. But you have limited output. Every wafer matters. Every defect-free chip that comes off the line has a place to go.

Server chips for data centers fetch higher per-unit prices than consumer processors. They have long-term, high-volume contracts with enterprise customers. A single major cloud provider or enterprise IT department can commit to hundreds of thousands of units annually. By contrast, consumer chips are sold through retail channels with more variable demand. From a manufacturing perspective, which do you prioritize when you can't make enough for everyone?

Intel's data center and AI divisions showed strong growth in Q4 2025, contrasting with declines in client computing. This 16-point divergence highlights shifting priorities and resource allocation challenges.

Strategic Pivot: Why Consumer Chips Are Taking the Hit

Intel's manufacturing capacity decisions reveal uncomfortable truths about the business. Data center chips are where the profit margins live today. Consumer CPUs are important for brand presence and long-term competitiveness, but they're not where the money flows.

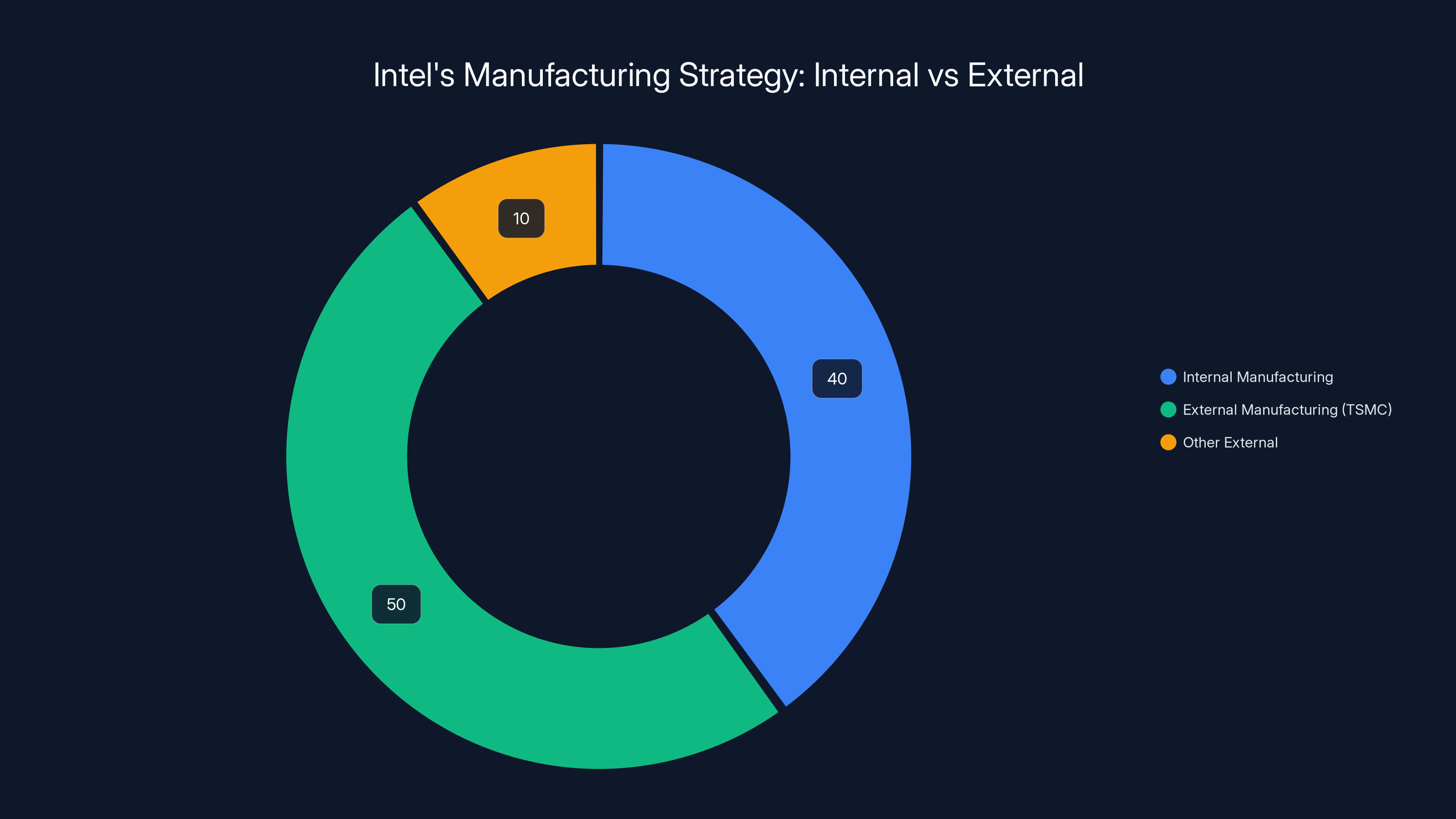

This realization has forced Intel into a strategic pivot. The company is explicitly shifting consumer chip manufacturing away from its own fabs. More Core Ultra Series 3 processors will be manufactured by external foundries, primarily TSMC. This is a significant shift from the Core Ultra Series 2, which relied more heavily on Intel's internal manufacturing.

TSMC, located in Taiwan, operates the world's most advanced semiconductor manufacturing facilities outside of Intel. The company has proven yields on advanced processes and the capacity to handle volume production. For Intel, outsourcing represents a pragmatic short-term solution. But it also represents a strategic retreat. Intel has spent years and billions of dollars building a foundry business to become less dependent on TSMC. This move suggests that ambition is being subordinated to immediate business realities.

CFO David Zinsner acknowledged the awkward position directly. "We can't completely vacate the client market," he said. Intel can't afford to cede consumer processors entirely to competitors. That would destroy brand equity and long-term competitive position. But the statement reveals the temptation. If data center was the only business, Intel wouldn't hesitate to consolidate manufacturing there.

The irony is that this manufacturing crunch arrives exactly when Intel needs consumer momentum. The Core Ultra Series 3 represents a genuine technological leap. The Panther Lake architecture promises improved performance per watt, better AI acceleration, and genuine competitive advantages over AMD's latest consumer offerings. But instead of riding that wave, Intel is managing supply constraints.

The Panther Lake Dilemma: Great Chip, Wrong Timing

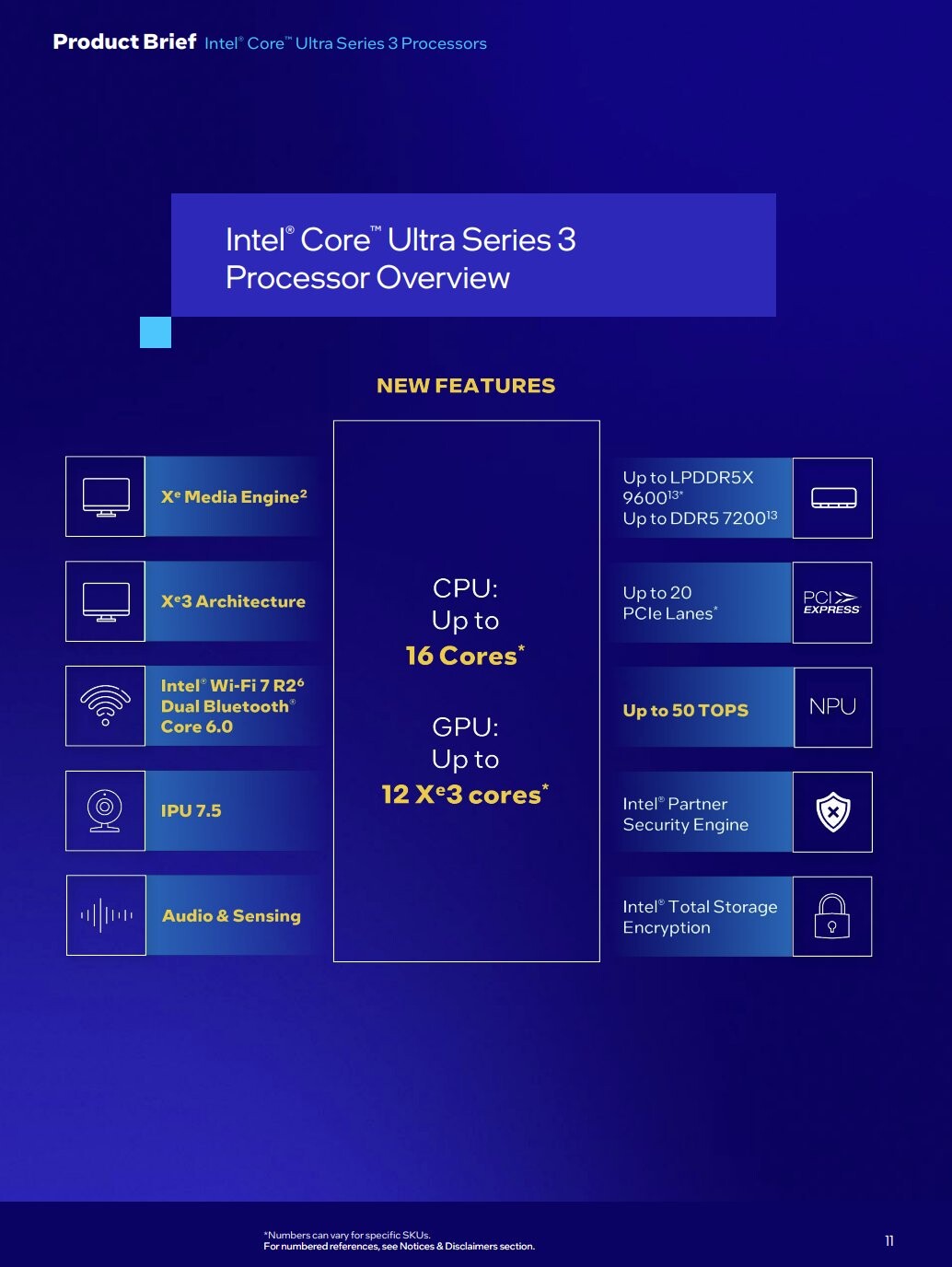

The Core Ultra Series 3, codenamed Panther Lake, represents Intel's most significant investment in consumer processor design in over a year. These processors are designed primarily for laptops, with capabilities specifically optimized for AI acceleration, content creation, and productivity workloads.

On paper, Panther Lake addresses every major complaint about Intel's consumer offerings. Performance-per-watt improvements should exceed AMD's latest Ryzen offerings. Power efficiency will enable thinner, lighter laptops with longer battery life. Integrated graphics improvements mean better gaming and content creation performance without discrete GPUs.

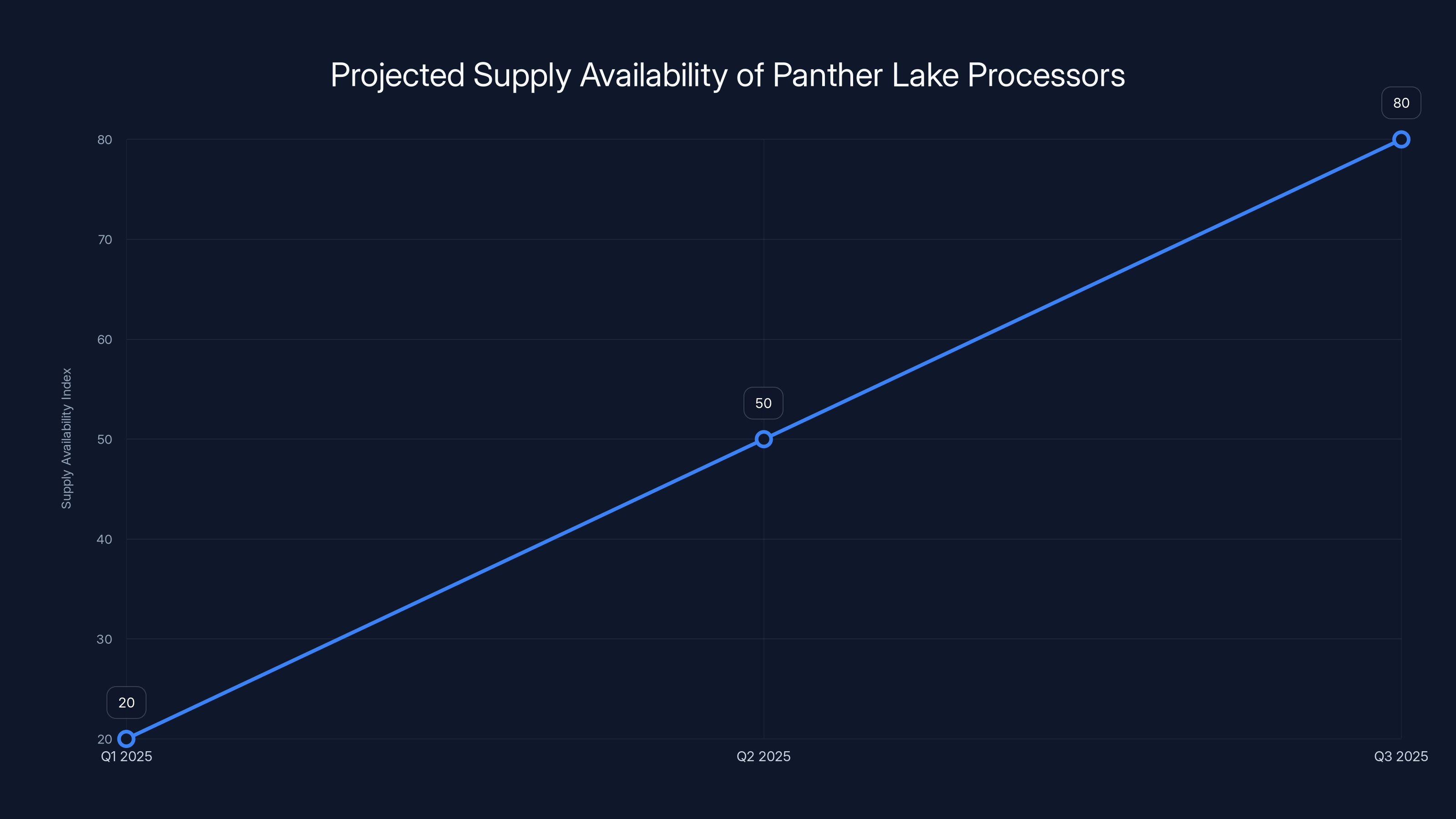

But none of that matters if the chips aren't available. And Intel has just signaled, through its manufacturing decisions, that significant supply constraints are coming. Zinsner said Q1 2025 would be "the trough"—the lowest point of supply availability. The company expects Q2 to see meaningful improvements. That's a three-month window where customers will struggle to find Panther Lake processors.

For OEM partners like Dell, Lenovo, and HP, this creates a nightmare scenario. They want to launch Panther Lake laptops. Customers are waiting for these systems. But Intel might not be able to supply the processors in the quantities needed for aggressive market launches. This could translate into delayed product announcements, limited initial availability, and premium pricing for the configurations that do become available.

Intel is well aware of this problem. CEO Lip-Bu Tan explicitly said the company is "working aggressively to address this and better support our customers' needs going forward." That language suggests Intel is pulling every lever available—accelerating 18A yield improvements, routing more production to external partners, and probably making some supply chain and allocation decisions that keep customers happy enough not to defect to AMD.

Supply Chain Strategies: Internal Versus External Manufacturing

Intel's response to supply constraints reveals a fundamental shift in manufacturing philosophy. The company is explicitly increasing reliance on external foundries, particularly TSMC, for consumer processor production.

This decision has short-term and long-term implications. Short-term, it solves an immediate problem. TSMC has advanced manufacturing capacity available. They can absorb some Panther Lake production and deliver consistent yields. This ensures at least some processors are available, even if total volume falls short of demand.

Long-term, this decision undermines Intel's foundry business strategy. For years, Intel has been positioning itself as a capable foundry alternative to TSMC. The company has invested tens of billions in manufacturing infrastructure. CEO Lip-Bu Tan talks about becoming a "foundry of choice" for external customers. That vision requires proving Intel can compete with TSMC on yield, cost, and capacity.

But when Intel can't even supply its own consumer divisions reliably, the message sent to potential external foundry customers is clear: "Maybe buy from someone else." It's a credibility problem. Intel can't afford to have it become conventional wisdom that the company's fabs are unreliable.

However, Zinsner's framing suggests Intel sees this as temporary. The company expects to fix the yield problem within quarters, not years. Once 18A yields reach acceptable levels—say, 50%+ of processed wafers producing usable chips—Intel should have enough internal capacity to supply both data center and consumer divisions without outsourcing. But that's still months away.

Intel is also exploring a middle path. The company is engaging "potential external customers" who want to use Intel's manufacturing facilities for their own chip designs. If third parties adopt Intel's 18A process, the company builds long-term revenue streams and proves the process works at scale. Intel expects to know which external customers will commit "starting in the second half of 2025 and extending into the first half of 2026."

This timeline suggests Intel sees significant opportunity here. The company is betting that once yields stabilize and external demand becomes apparent, it can justify building new manufacturing capacity. That's a risky bet. Building new fabs costs $15-20 billion minimum. You only commit that kind of capital if you're confident demand will materialize and sustain.

Intel's 18A process yields are projected to improve from an initial 10% to approximately 14.7% over five months with an 8% monthly increase. Estimated data.

The AI Factor: Why Data Center Demand Is Relentless

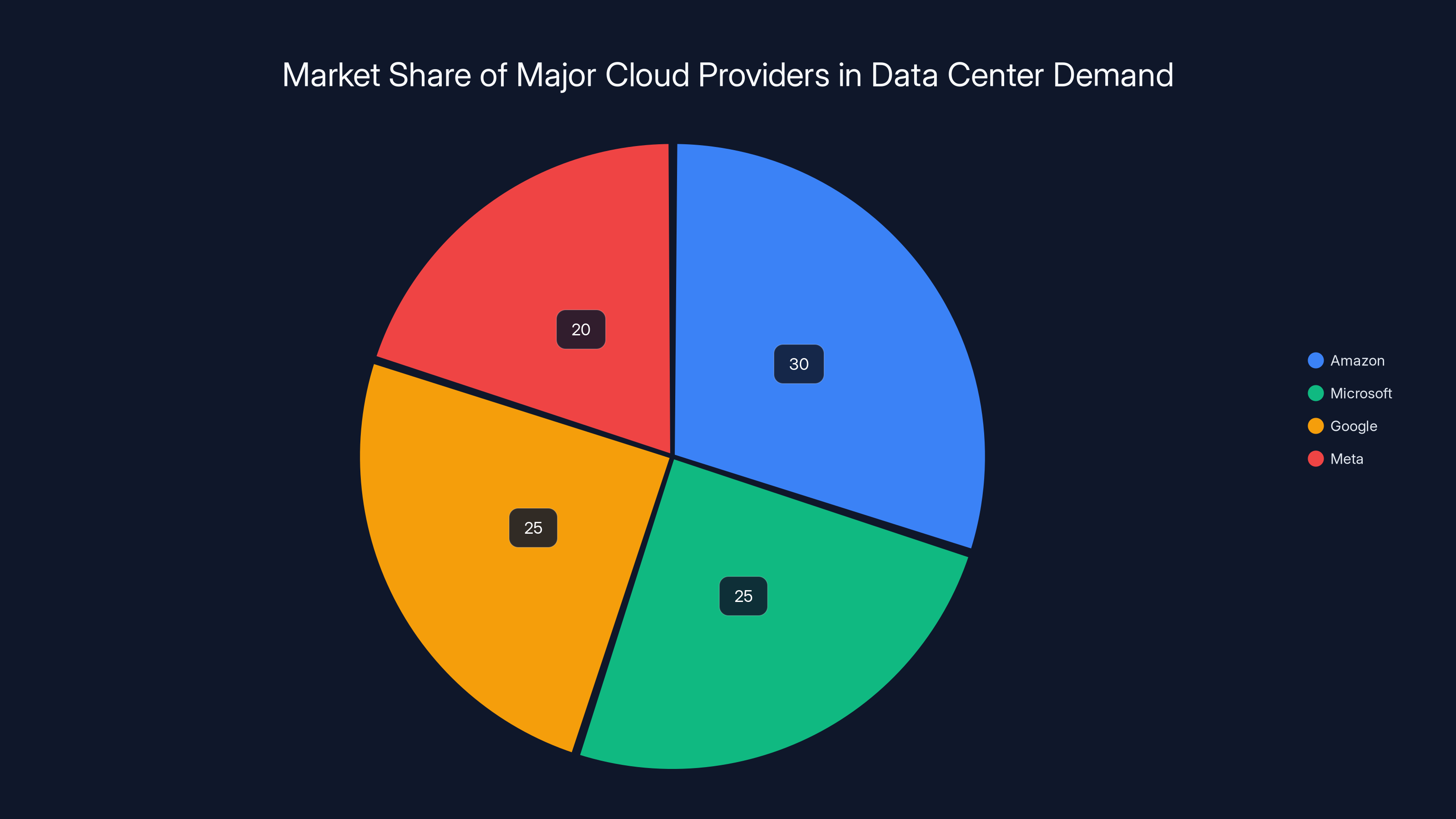

Underlying Intel's supply allocation decisions is a brutal fact: data center demand is extraordinary and showing no signs of easing. Enterprise AI workloads are accelerating faster than almost everyone predicted. Cloud providers are building massive data center infrastructure to serve the AI boom. And they're not patient about waiting for chips.

Granite Rapids, Intel's latest data center processor, is specifically designed for AI acceleration. Features like new AI instruction sets and improved memory bandwidth directly address AI training and inference workloads. When major cloud providers—Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta—are building data centers around these chips, they're not going to accept supply constraints gracefully.

These are customers with enormous purchasing power and long-term commitments. One major cloud provider might represent $100+ million in annual processor purchases. That kind of customer gets executive attention. That's the customer who gets allocated scarce manufacturing capacity.

Consumer markets work differently. PC demand is cyclical. Laptop cycles are 3-4 years. Consumers are price-sensitive and will accept substitutes—in this case, AMD processors. A startup might not be able to sell a laptop with a Core Ultra Series 3 if supply is constrained, so they'll use a Ryzen instead. The end user gets a good product. The OEM sells through their inventory. But Intel loses that opportunity.

From a pure financial perspective, the decision to prioritize data center is defensible. But it comes with competitive risk. AMD is watching this situation carefully. If AMD can position Ryzen as the reliable choice while Panther Lake is scarce, AMD gains market share in a segment where Intel has been desperately trying to rebuild relevance.

Yield Improvements and Timeline: The Path to Normalization

Intel's manufacturing roadmap hinges on yield improvements over the coming months. The company has been transparent about the current trajectory: 7-8% monthly improvement rates starting from a low base.

Let's model this out in detail. If initial yields were 10% in summer 2024, and the company has improved yields at 7.5% monthly rates for six months, yields should now be around 15-16%. That's still nowhere near the 50%+ mature yields the company needs for comfortable profitability.

However, Moore's Law—or rather, the semiconductor equivalent of yield improvement curves—shows that yields typically accelerate over time. Initial improvements are difficult and slow. Once you understand the primary failure modes and address them, subsequent improvements come faster. Intel reports steady 7-8% improvements, but the company probably expects that to accelerate as it addresses known issues.

If yields can reach 30% by mid-2025, and 50%+ by end of Q3 2025, then Intel's capacity situation fundamentally changes. At 50% yields, the company can produce twice as many usable chips from the same wafer volume. That's enough to satisfy both data center and consumer demand without the brutal allocation decisions currently necessary.

CFO Zinsner pinpointed Q1 2025 as "the trough." That language suggests Intel's internal models show the supply situation bottoming out around now, with material improvements following in Q2 and continuing through Q3. If accurate, consumer chip availability should improve significantly by summer 2025.

If a single wafer yields 500 total chips, and yields improve from 10% to 50%, usable chips increase from 50 to 250 per wafer—a fivefold improvement. That's the manufacturing leverage Intel is counting on.

But here's the risk: these are management projections made under pressure to calm investors and customers. History shows semiconductor yield improvements often face unexpected obstacles. Contamination issues, equipment problems, or fundamental process design flaws can slow progress. If Intel hits unexpected problems, the timeline for normalization extends further, and consumer chip shortages persist longer.

Next-Generation Architecture: Nova Lake and Beyond

While Intel struggles with current-generation supply, the company is simultaneously engineering next-generation processors. Nova Lake represents Intel's next major consumer processor architecture, expected to debut at the end of 2026.

Nova Lake will be particularly significant because it will be Intel's first new architecture to unify desktop and laptop processor lines in years. Panther Lake chips are primarily laptop-focused, with designs optimized for low power and thin systems. Nova Lake aims for broader applicability across form factors while maintaining performance and efficiency advantages.

At least portions of Nova Lake will manufacture on Intel's 18A process. This means the company is betting that by 2026, 18A yields will be mature enough to support next-generation architecture at volume. That's an ambitious timeline. It requires current yield problems to be fully resolved, perhaps a year before Nova Lake launch.

This creates an interesting pressure. Intel needs current 18A issues fixed quickly, not just for Panther Lake consumer availability, but to establish a manufacturing track record good enough to support Nova Lake by late 2026. Failed yield targets now would catastrophically damage confidence in Intel's ability to deliver Nova Lake on schedule and at competitive pricing.

The company is also exploring external foundry work on the 14A process—the generation after 18A. Intel is actively recruiting external customers who would use Intel's fabs for their own chip designs. This represents a diversification strategy. Rather than relying entirely on Intel's own processor designs to drive fab utilization, Intel can host third-party designs.

Managing this transition requires extraordinary execution. Intel needs to prove 18A works, start delivering Nova Lake, and simultaneously convince external customers that 14A will be worth adopting. That's a tall order for a company currently unable to satisfy its own consumer division.

Estimated data shows Intel's current reliance on external manufacturing, with TSMC handling 50% of consumer processor production. This shift highlights Intel's strategic pivot to address supply constraints.

Competitive Implications: AMD's Opportunity

Intel's supply constraints represent a gift to AMD. The company has been steadily improving its consumer processor offerings and gaining market share. Now, with Panther Lake facing availability challenges, AMD's latest Ryzen processors become the obvious alternative for customers who can't wait for Intel.

AMD understands this dynamic and is probably accelerating production of competitive consumer processors. The company has strong relationships with TSMC and long-standing foundry capacity. AMD probably isn't facing the same supply constraints as Intel because AMD's primary business—consumer graphics and processors—already runs through foundries.

For OEMs, this situation is incredibly frustrating. They want Panther Lake's capabilities. But if Panther Lake is scarce, they'll design laptops and desktops around Ryzen 9000-series processors instead. Once that design work is done and systems are launched, the inertia favors sticking with that platform even after Panther Lake becomes available. Customers stick with what they know.

Intel also faces mind-share challenges. If Panther Lake is difficult to find in Q1 and Q2 2025, review sites will start declaring Ryzen as the default consumer choice. That narrative, once established, sticks even after supply normalizes. It takes significant marketing spend and availability to shift perceptions.

This is exactly the scenario Intel's leadership has been trying to avoid. The company finally has a genuinely competitive consumer processor, and supply constraints prevent capitalizing on it. It's infuriating for management and a victory for Intel's competitors.

Enterprise Implications: Data Center's Growing Dominance

What's clear from Intel's earnings and supply decisions is that the company's future increasingly depends on data center success. The company's growth, profitability, and strategic focus are all migrating toward enterprise and cloud computing.

Consumer processors have become almost a brand maintenance investment rather than a profit center. Intel needs consumer credibility so large enterprises trust Intel's data center offerings. But the actual business leverage has shifted decisively to enterprise.

This represents a massive strategic pivot for a company that built its identity on consumer processors. For decades, Intel's primary narrative focused on consumer PC performance. Moore's Law advances were demonstrated on consumer CPUs. Desktop performance improvements drove consumer enthusiasm and purchase decisions.

Today, data center matters more. A successful data center strategy generates more revenue, higher margins, and faster growth than consumer processors ever will. Intel's financial results confirm this ruthlessly. The company's willingness to constrain consumer supply in favor of data center production proves where true priorities lie.

For enterprise customers, this should be encouraging. It means Intel will prioritize their needs, ensure supply reliability, and continue investing heavily in the data center processor roadmap. For consumer customers, it's less favorable. You're now second priority in Intel's resource allocation.

Foundry Strategy: The Risky Pivot

Intel's attempt to build a foundry business—manufacturing chips designed by other companies—has been central to CEO Lip-Bu Tan's strategic vision. The idea is that Intel's fabs should never be idle. If Intel's own processor volumes fluctuate, foundry customers would provide steady revenue and fab utilization.

Current supply constraints undermine this narrative. Intel can't even satisfy its own divisions. How can it credibly commit to delivering external foundry customers' chips? This creates a credibility problem that will persist until Intel demonstrably fixes its yield issues.

Zinsner mentioned that Intel expects to identify new foundry customers in H2 2025 and H1 2026. These are artificial timelines designed to communicate confidence. In reality, potential external customers are probably already approaching Intel with skepticism. They're asking questions like: "You can't supply your own consumer division. Why should I trust you with my chips?"

Intel will need to overcome this skepticism through demonstrated results. That means successfully ramping Panther Lake production, showing consumer chip availability improving significantly in Q2-Q3 2025, and making the 18A process work reliably. Only then will external customers seriously consider Intel as a foundry partner.

This isn't an impossible task, but it's substantially harder because Intel must do this while managing existing supply pressures. The company is trying to fix the ship while sailing it.

Amazon leads with an estimated 30% market share in data center demand, followed by Microsoft and Google at 25% each, and Meta at 20%. Estimated data based on purchasing power.

Financial Impact: What's Priced Into Valuations

Intel's supply constraints are known to investors. The stock market has already partially priced in some expectation of consumer chip shortages and revenue impact. However, markets hate uncertainty. If actual Q1 2025 results show worse supply situations than management guided, stock will likely decline further.

Conversely, if Intel exceeds expectations on yield improvements or announces earlier-than-expected capacity increases, the stock could rally significantly. Supply normalization would be a major positive catalyst for Intel's consumer division and broader business credibility.

The company's current capital allocation—prioritizing data center manufacturing—makes financial sense. It maximizes near-term profitability. But it comes with a competitive risk if AMD uses the opportunity to establish stronger market position in consumer segments.

Intel's investors need to watch Q2 2025 earnings carefully. That's when the company will report whether Q1 actually was the supply trough, or whether constraints persisted longer than expected. This will either confirm management's timeline or expose it as overly optimistic.

Supply Chain Lessons: What the Industry Learns

Intel's situation offers broader lessons for the semiconductor industry and companies dependent on chip supply. Concentrated manufacturing creates concentration risk. When advanced fabs are expensive and complex, companies naturally want to maximize their utilization and drive continuous improvement. But this means limited flexibility when unexpected challenges arise.

The fact that a single new process node's yield problems can constrain multiple business divisions reveals how brittle semiconductor supply actually is. One manufacturing line, one process node, one yield problem, and entire product categories face allocation pressure.

Companies like Apple and Meta that invested in custom silicon partly to reduce dependence on external suppliers are probably watching this situation and feeling validated. When you control your manufacturing through a foundry partner like TSMC, you have options and flexibility. When you're dependent on a single company's internal fabs, you accept whatever allocation decisions that company makes.

For Intel's customers, the lesson is clear: build supply chain redundancy. Don't commit entirely to a single processor supplier. Maintain relationships with alternatives. When supply gets tight—and it will, eventually—you'll be grateful for the options.

Timeline to Recovery: When Supply Normalizes

Based on Intel's guidance and manufacturing reality, here's a realistic timeline for supply normalization:

Q1 2025 (January-March): Supply trough. Panther Lake availability extremely limited. Price premiums likely for available configurations. Customers waiting weeks for delivery.

Q2 2025 (April-June): Meaningful improvement. Intel expects yield ramps to materialize. Consumer chip availability improving week-over-week. First systems with Panther Lake launching in late Q2.

Q3 2025 (July-September): Supply approaching normal. Yields should have reached 30-40% range. Inventory levels building. Consumer choice and configuration options expanding.

Q4 2025 and beyond: Full supply normalization. Yields reaching 50%+ mature levels. Consumer and data center divisions both getting adequate allocation. Supply constraints becoming historical artifact.

This timeline assumes Intel executes flawlessly on yield improvements and avoids significant manufacturing disruptions. Any setbacks—contamination, equipment problems, process redesigns—extend this timeline proportionally.

Real historical precedent suggests timeline extensions are common in semiconductor manufacturing. Intel's 7nm process faced similar yield challenges and experienced multiple delays. This timeline represents best-case execution, not median case.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in Panther Lake processor availability from Q1 to Q3 2025, with Q1 being the lowest point.

Strategic Implications: What This Means for Intel's Future

Intel's supply constraints force uncomfortable strategic conversations. The company is choosing to be a data center player first, consumer player second. That's not necessarily wrong—data center is more profitable. But it has long-term consequences.

Consumer processors are the foundation of PC market presence. They drive brand awareness and customer relationships that eventually translate to server processor sales. Enterprise IT decision-makers buy Intel data center chips partly because they trust Intel in consumer markets. Ceding consumer market share undermines this relationship.

AMD understands this dynamic intimately. AMD has used strong consumer processor offerings to build brand credibility, which then supports data center sales. AMD's strategy emphasizes competing directly with Intel across consumer and enterprise segments simultaneously.

Intel's current approach—sacrificing consumer share for data center margin—might maximize near-term profit. But it could erode long-term competitive position if AMD successfully establishes itself as the default processor choice across both segments.

The company's leadership seems aware of this risk. CEO Tan repeatedly emphasized Intel's commitment to the consumer market. "We can't completely vacate the client market," he said directly. But actions speak louder than words. When manufacturing constraints force choices, Intel is choosing data center. That sends a clear signal about true priorities.

Intel needs to exit this supply crisis quickly, restore consumer chip availability, and prove that current constraints are temporary. Otherwise, the perception will calcify that Intel doesn't prioritize consumer customers. That perception, once established, is extraordinarily difficult to reverse.

The Bigger Picture: Manufacturing Concentration and Tech Supply Chains

Intel's supply crisis reflects broader challenges in semiconductor manufacturing. Advanced chip fabrication is incredibly complex and expensive. This creates natural concentration. Only a handful of companies—Intel, TSMC, Samsung, a few others—can manufacture cutting-edge semiconductors.

This concentration creates systemic risk. When one major manufacturer hits supply constraints, the entire industry feels the impact. Customers have limited alternatives. They can either accept allocation decisions or wait for competitor fabs to ramp.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated this risk acutely. Supply chain disruptions for a single component type cascaded into global shortages. Millions of devices couldn't be manufactured because of chip constraints. This situation wasn't fundamentally different from Intel's current problem—just broader in scope.

Governments worldwide are now investing in semiconductor manufacturing capacity to reduce this concentration risk. The U. S. CHIPS Act provides incentives for domestic manufacturing. Europe is funding fabs. Japan and South Korea are investing in capacity. The goal is to reduce dependence on concentrated sources of advanced manufacturing.

Intel's challenges are both a symptom of and contributor to this concentration. The company's manufacturing problems demonstrate why concentration is risky. Intel's own supply constraints are pushing customers toward alternatives, which pushes demand toward TSMC and other competitors.

This creates an interesting feedback loop. Intel's manufacturing problems could actually accelerate the shift toward distributed, diversified chip manufacturing. Customers burned by Panther Lake availability might explicitly specify TSMC process nodes for future designs. That means less business for Intel's fabs and potentially lower utilization once the current crisis passes.

Consumer Perspective: What You Should Know

If you're shopping for a new laptop or desktop, here's the practical reality. Q1 2025 is a bad time to buy Panther Lake processors. Availability is limited, pricing is elevated due to scarcity, and configuration options are restricted.

Better strategy: Wait until April or May if possible. By then, supply should be improving materially. You'll have better selection, more competitive pricing, and higher confidence that your system will ship quickly.

Alternatively, consider AMD processors now. Ryzen 9000-series offers excellent performance and is available in volume. You're not sacrificing performance for availability. You're just choosing a different brand.

Intel's supply situation shouldn't drive you to a processor that doesn't meet your needs. But if you're choosing between Panther Lake and Ryzen, and Panther Lake isn't available, Ryzen is a perfectly reasonable alternative. Intel's supply problems are not your problem to solve.

One caveat: if you need specific Panther Lake features—particular AI acceleration capabilities or specific power profiles—waiting is justified. But if you just need a good processor now, alternatives exist.

Q&A: Getting Clarity on the Situation

The supply situation raises numerous customer questions. Here are answers to the most common ones.

When will Panther Lake processors be widely available?

Management guidance suggests late Q2 2025 or early Q3. That means June through August timeframe for real supply normalization. April and May should see meaningful improvement but not full availability.

Are Panther Lake processors worth waiting for, or should I buy Ryzen now?

Worth waiting if you need specific capabilities. Performance-per-watt improvements are real. AI acceleration is genuinely useful. But Ryzen is a solid alternative if waiting isn't practical. Don't delay essential purchases for a chip that might not arrive for months.

Will Panther Lake prices be higher due to shortages?

Likely, yes. Limited supply plus strong demand equals higher prices. This should normalize once supply increases. If you can wait until Q3 2025, prices will probably be 10-15% lower than Q1-Q2 premiums.

Is this Intel's fault? Should I avoid Intel processors?

Manufacturing challenges are a normal part of semiconductor industry. Intel is communicating transparently about the problem and timeline for resolution. This isn't a quality issue with the chips themselves. It's a supply chain problem that should resolve within months.

Will this affect data center or server processor availability?

Unlikely. Data center processors are being manufactured at higher priority. Enterprise customers should see normal supply. This mainly affects consumer segments.

Industry Analysis: What Competitors Are Thinking

AMD is clearly paying close attention. The company has strong Ryzen momentum and Panther Lake shortages are accelerating that trend. AMD's messaging is probably shifting to emphasize reliability and availability—"Choose AMD, get your systems shipped on time."

ARMs designs for consumer processors (through partners like Qualcomm) are watching to see if Intel's supply problems extend to longer-term market share losses. If customers switch to AMD or ARM-based systems due to Panther Lake unavailability, re-establishing Intel presence later becomes harder.

TSMC is in an interesting position. The company benefits from Intel's internal manufacturing problems because more Intel consumer chips will be manufactured at TSMC. This increases TSMC's utilization and revenue. However, TSMC is also capacity constrained due to strong demand from multiple customers. Intel's outsourcing needs might actually compete for limited TSMC capacity.

Samsung, as the third major advanced logic manufacturer, sees opportunity. If TSMC is constrained and Intel can't supply, Samsung could potentially pick up incremental business. However, Samsung's yields on advanced processes have been historically less reliable than TSMC, limiting its appeal.

For the entire ecosystem, Intel's situation reinforces the value of TSMC's leadership position. TSMC doesn't face self-imposed supply constraints because the company manages foundry capacity differently than Intel manages internal fabs. This is exactly the kind of situation that justifies why so many companies trust TSMC as their primary foundry partner.

FAQ

What is the Intel Panther Lake supply situation?

Intel Core Ultra Series 3 (Panther Lake) consumer processors are facing supply constraints because the company is prioritizing higher-margin data center chip production. Intel's 18A manufacturing process has yield issues that limit total output. When forced to allocate limited production between consumer and data center divisions, Intel is choosing data center—where demand is strongest and margins are highest.

Why did Intel decide to prioritize data center over consumer chips?

Intel's data center and AI products grew 9% last quarter while consumer processors declined 7%. The financial incentive is clear: data center chips generate more revenue per unit and face stronger long-term demand from cloud providers building AI infrastructure. Enterprise customers also command more negotiating power and can enforce supply commitments more effectively than consumer customers.

When will Panther Lake availability normalize?

Intel management indicated Q1 2025 is the "trough" of supply constraints, with meaningful improvement expected in Q2 2025. Full normalization probably won't occur until Q3 2025, once 18A process yields reach sustainable 40-50% levels. This timeline assumes Intel executes on yield improvements without significant manufacturing disruptions.

What is the 18A process and why is it causing problems?

The 18A process is Intel's latest manufacturing technology node—essentially, the smallest transistor size Intel can currently manufacture. Smaller transistors enable more powerful, efficient chips. However, 18A is cutting-edge, and yields (the percentage of chips that work properly) started very low—around 10% in summer 2024. Manufacturing yields are improving 7-8% monthly, but improvement takes time, limiting total chip output.

Should I buy Panther Lake or wait for better availability?

If you need a processor now, consider AMD's Ryzen 9000-series alternatives. If you can wait until late spring 2025, Panther Lake supply and pricing should improve. If you specifically need Panther Lake's capabilities (particular AI acceleration features or power efficiency for ultra-thin laptops), waiting is justified. Otherwise, don't let supply constraints drive you to a processor that doesn't meet your needs.

Will this affect my data center processor orders?

Unlikely. Data center processors are being manufactured at higher priority than consumer chips. Enterprise customers with committed orders or long-term contracts should not experience supply issues. However, spot market availability might be constrained as Intel's internal supply is directed toward priority customers.

Is Intel's foundry business affected by these supply constraints?

Yes, negatively. Intel is trying to recruit external customers for its foundry services, but current supply constraints undermine the pitch. Why would an external customer trust Intel to manufacture their chips when Intel can't even supply its own consumer division? The company needs to demonstrate that current problems are temporary and 18A yields will stabilize reliably before external customers will seriously consider Intel as a foundry partner.

What about Nova Lake, Intel's next-generation architecture?

Nova Lake is expected to launch at end of 2026 and will likely use 18A manufacturing, at least partially. Intel is essentially betting that 18A yield problems will be completely resolved well before Nova Lake launches. This creates pressure to fix current issues quickly. If yields remain problematic in late 2025, Nova Lake's launch could face similar supply constraints.

Is this situation bad for Intel's competitive position?

Potentially, yes. AMD is positioned to gain consumer market share while Panther Lake is scarce. Once customers buy Ryzen systems, inertia favors sticking with that platform. Intel can recover market share later, but it requires aggressive marketing and pricing. Long-term, Intel's willingness to constrain consumer supply signals that consumer processors are lower priority, which could influence customer decisions to diversify away from Intel.

What does this teach the semiconductor industry?

Intel's situation demonstrates the risks of concentrated manufacturing. When advanced chip production is expensive and complex, only a few companies can participate. This concentration creates systemic risk. When one manufacturer hits problems, customers have limited alternatives. Governments worldwide are responding with subsidies for distributed manufacturing capacity to reduce this concentration risk.

Conclusion: Navigating Uncertainty and Supply Constraints

Intel's supply constraints represent an uncomfortable but temporary reality in the semiconductor industry. The company is making clear-eyed business decisions about how to allocate limited manufacturing capacity. Data center demand is stronger and more profitable than consumer demand. Allocating scarce resources to serve data center is strategically defensible, even if it frustrates consumer customers.

But this situation carries long-term competitive risks. AMD is positioned to capture market share while Panther Lake is scarce. Once customers switch to Ryzen, they're not necessarily eager to switch back. Brand preferences and system familiarity become sticky. Intel's leadership is aware of this risk—CEO Tan repeatedly emphasized the importance of the consumer market. But awareness and prioritization are different things. Intel's actions prove where true priorities lie.

For consumers, the practical advice is straightforward. Don't let Intel's supply crisis dictate your purchasing decisions. If you need a processor now, AMD Ryzen offers excellent value and immediate availability. If you can wait until spring 2025, Panther Lake supply and pricing should improve materially. If you specifically need Panther Lake's unique capabilities, waiting is justified. But waiting for a processor you don't actually need makes no sense.

For enterprises and OEM partners, Intel's transparent communication about the problem and timeline is actually valuable. The company is not hiding the situation. Management is setting clear expectations about Q1 being the trough and Q2-Q3 showing improvement. Plan accordingly. Lock in supply commitments if you depend on Intel chips. Establish relationships with AMD as a backup. Build redundancy into your supply chain.

The semiconductor industry will eventually build more distributed manufacturing capacity, reducing concentration risk. But that's years away. For now, companies with customer commitments need to navigate the existing constrained landscape strategically.

Intel's situation will resolve. Yields will improve. Production capacity will increase. Panther Lake will eventually be available in quantities that satisfy demand. The question is whether Intel's handling of this period—prioritizing data center over consumer—permanently shifts customer relationships in ways that disadvantage Intel when supply normalizes.

For Intel to recover from this situation with minimal competitive damage, the company needs to deliver on its yield improvement timeline, demonstrate that supply constraints are genuinely temporary, and quickly return to messaging that consumer processors matter as much as data center chips. That's a tall order, but it's achievable with focused execution.

Key Takeaways

- Intel's data center business (up 9% quarter) is thriving while consumer processors (down 7%) are struggling, forcing supply prioritization toward higher-margin server chips

- Core Ultra Series 3 Panther Lake consumer processors face significant availability constraints through Q1 2025, with improvement expected starting in Q2 2025

- 18A manufacturing process yields remain below acceptable levels at roughly 10-15%, though improving 7-8% monthly, fundamentally limiting overall chip production capacity

- Intel is shifting more consumer processor manufacturing to external foundries like TSMC, acknowledging it cannot satisfy both data center and consumer demand from internal fabs alone

- AMD Ryzen processors represent a practical alternative for consumers who cannot wait for Panther Lake availability, with supply normalizing expected by Q3-Q4 2025

Related Articles

- TSMC's AI Chip Demand 'Endless': What Record Earnings Mean for Tech [2025]

- Taiwan's $250B US Semiconductor Deal Reshapes Global Supply Chains [2025]

- AI Bubble or Wave? The Real Economics Behind the Hype [2025]

- Nvidia's $1.8T AI Revolution: Why 2025 is the Once-in-a-Lifetime Infrastructure Boom [2025]

- Kioxia Memory Shortage 2026: Why SSD Prices Stay High [2025]

- How Trump's Tariffs Are Creeping Into Amazon Prices [2025]

![Intel Core Ultra Series 3 Launch Delayed by Supply Crunch [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/intel-core-ultra-series-3-launch-delayed-by-supply-crunch-20/image-1-1769202414719.jpg)