Introduction: The Phone in Your Hand Is a Tool of Power

A phone raised during a moment of crisis. A camera capturing what authorities want hidden. A video uploaded, shared, retweeted, duplicated across a thousand platforms before any official narrative can take shape. This is the new frontier of resistance—not organized protest alone, but the distributed power of documentation.

In January 2025, federal agents shot and killed a man named Alex Pretti on a Minneapolis street. Within hours, the incident had spawned multiple video angles, frame-by-frame analysis from major news outlets, and competing narratives about what actually happened. One video showed Pretti holding his phone seconds before agents tackled him. Another showed agents firing multiple shots. A third captured moments before the initial confrontation, as detailed in CNN's coverage.

The Trump administration's response was immediate and revealing. Rather than dispute the facts directly, officials worked to shape how people perceived those facts. They shared selective angles. They amplified narratives that contradicted what wider footage showed. They recognized something crucial: whoever controls the story's distribution often controls belief, regardless of what the footage actually shows, as analyzed by PBS NewsHour.

But here's what makes this moment different from previous eras of government conflict. The phone Pretti held—and the phones wielded by hundreds of bystanders—represent something authorities have never fully learned to suppress. Unlike newspapers or broadcast stations, which can be pressured or controlled, phones are distributed weapons. They're in billions of hands. They're networked across borders. They create redundancy by default.

This isn't a story about technology as savior. It's a story about asymmetry. Governments have learned to manufacture narratives at scale, to use social media fluently, to ally with platforms and influencers. But they've never successfully eliminated the basic friction of documented reality. And that friction is becoming the terrain where power itself is contested.

The question isn't whether phones will change politics. They already have. The question is what happens when governments, having learned their lessons from 2020, develop more sophisticated strategies to control not just the narrative, but the very distribution and perception of visual evidence.

TL; DR

- Phone cameras have become primary documentation tools for recording government actions, creating real-time evidence that officials can't fully suppress

- Competing narratives emerge from multiple angles, making it harder for any single authority to control the story

- Social media distribution creates redundancy: once video spreads across platforms, deletion becomes nearly impossible

- Governments have adapted by shaping perception rather than suppressing evidence, selectively amplifying favorable angles and counter-narratives

- Digital resistance remains asymmetrical: distributed phones vs. centralized state power creates ongoing friction between documentation and control

The Evolution of Documented Resistance: From Rodney King to Real-Time Sharing

The power of video evidence has a longer history than the smartphone era. In 1991, a Los Angeles resident named George Holliday recorded LAPD officers beating Rodney King with a handheld camcorder. That tape, played repeatedly on news broadcasts, became the visual centerpiece of a national conversation about police violence. It led to the 1992 LA riots. It changed how Americans thought about accountability.

But the Rodney King tape had limits. It existed as a singular artifact. There was one tape. News organizations controlled its distribution. They decided when to air it, how many times, with what framing. If you didn't own a VCR or didn't watch the right channel at the right time, you might never see it.

Thirty years later, in 2020, George Floyd's death generated not one tape but dozens. A high school student filmed the killing from one angle. Traffic cameras captured it from another. Nearby residents streamed it live on Facebook. News helicopters provided overhead shots. Within minutes, the footage was everywhere—fragmented across platforms, impossible to suppress, impossible to control.

That distributed documentation changed the equation. When one organization controls the narrative, they can shape it. When a hundred thousand people hold cameras, narrative becomes something contested rather than controlled.

The Derek Chauvin trial followed. Prosecutors didn't need to argue that the footage showed what it showed—everyone had seen it already. The question became narrower: did the officer have legal justification? The video didn't settle everything, but it settled the baseline reality. You couldn't argue that Chauvin wasn't kneeling on Floyd's neck. The visual evidence removed that possibility.

That's the core power that frightens authorities. Not that video proves guilt or innocence—courts still wrestle with interpretation. But that video removes certain false claims from the realm of possibility. You can't claim the officer wasn't there. You can't claim the victim attacked first. You can't claim there was no contact. The camera collapses certain lies before arguments begin.

What's changed since 2020 is that governments have learned this too. They've learned that you can't suppress the footage. What you can do is flood the zone with alternative angles, selective framings, and counter-narratives that exploit the same fragmented media landscape that distributed the original footage.

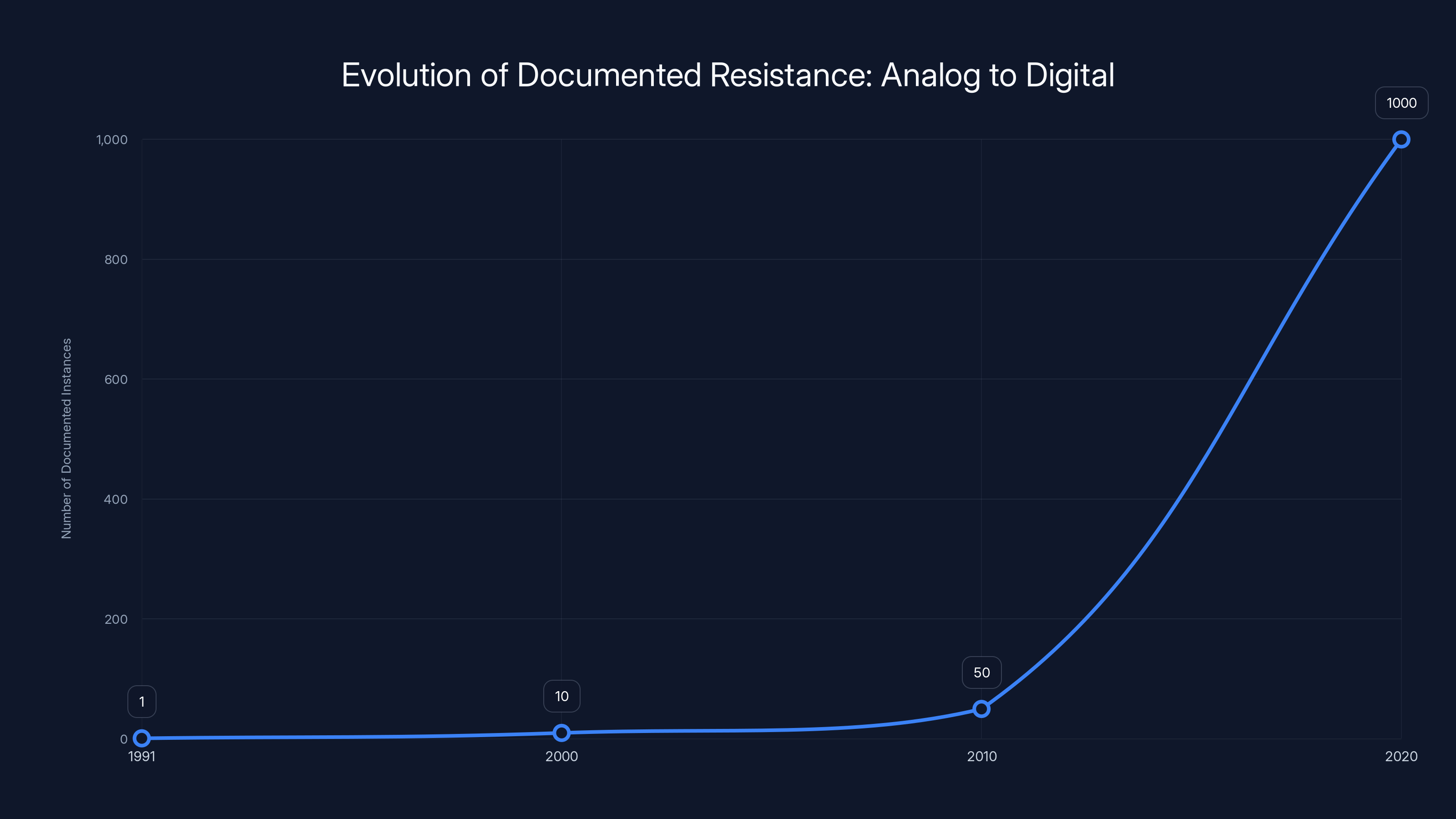

The shift from singular video evidence in 1991 to widespread, multi-angle documentation by 2020 highlights the exponential growth in video documentation due to digital technology. (Estimated data)

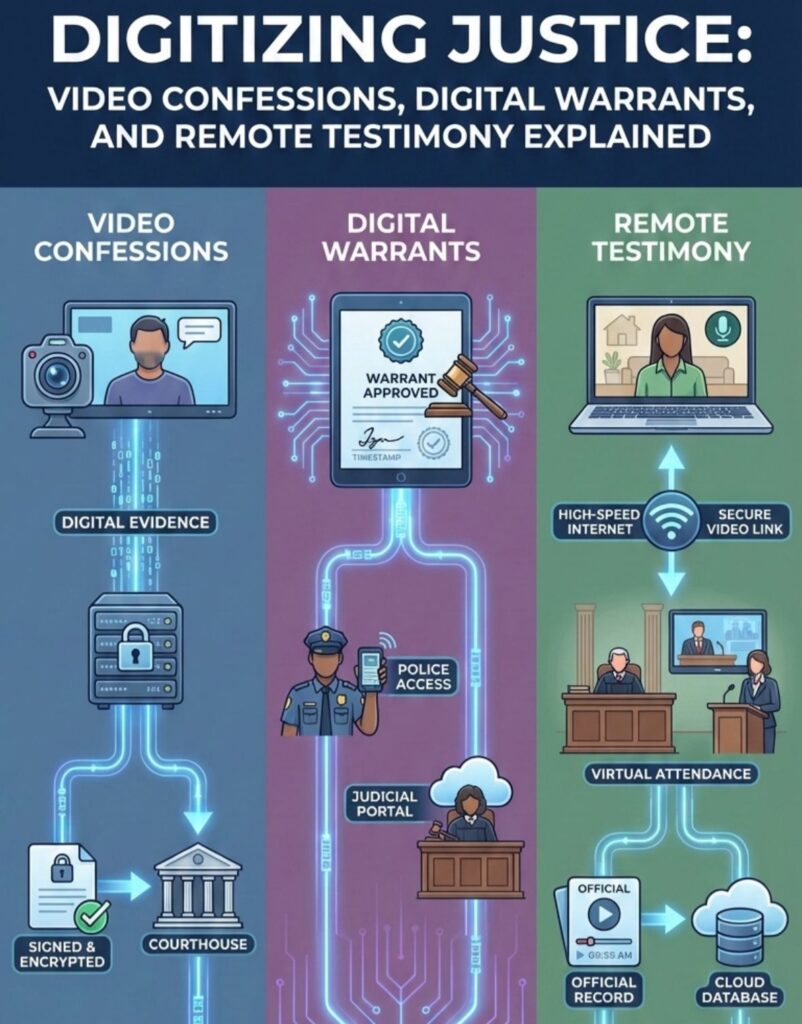

The Technical Architecture of Distributed Resistance

When a bystander holds up a phone, they're engaging in more than personal documentation. They're participating in a technical system designed—somewhat accidentally—to resist centralized control. Understanding that system matters for understanding why governments struggle to suppress video evidence while paradoxically becoming more sophisticated at shaping its interpretation.

First, there's redundancy by design. When someone records video on their phone, that video doesn't exist in one place. They might have it stored locally. If they upload to social media, it exists on that platform's servers. If they share it via messaging apps, it propagates through WhatsApp's or Signal's infrastructure. If someone downloads and re-uploads, it multiplies again. By the time viral video reaches true scale, there may be thousands of copies across incompatible platforms, jurisdictions, and technical architectures.

This redundancy is almost impossible to eliminate. A government could theoretically pressure one platform to remove video. But they can't pressure all platforms simultaneously, especially international ones. They could theoretically sue the original poster for defamation. But the video has already copied a thousand times. The suit might remove one version while hundreds persist.

Second, there's the speed problem. A video can spread to hundreds of thousands of people in minutes. Official responses take hours at minimum, often days. By the time a government statement lands, the base facts are already embedded in millions of minds, shared across networks, saved locally. The first story, even if later contradicted, has already won the race.

Third, there's the perception problem. When authorities rush to deny or reframe video, they paradoxically confirm that the video matters. Their defensive response amplifies it. If the footage showed nothing noteworthy, why would officials spend resources arguing against it? The very act of response signals that the footage is important—which makes people go watch it.

The technical architecture creates a situation where information wants to flow horizontally (peer-to-peer, platform-to-platform, person-to-person) rather than hierarchically (from state to citizen). Traditional government communication assumes hierarchy. You announce something. People receive it. That model works if you control all the communication channels. It fails when anyone with a phone can create their own channel.

What's particularly threatening to authorities is that this system doesn't require organization or leadership. There's no central authority directing people to record. No protest organizers coordinating angles. Thousands of people simply act independently, each with their own incentive to document what's happening. The result is a sort of distributed sensor network that no single entity can disrupt.

The Alex Pretti Case: Multiple Angles, Competing Narratives

The death of Alex Pretti in January 2025 illustrates both the power and the limitations of distributed video documentation.

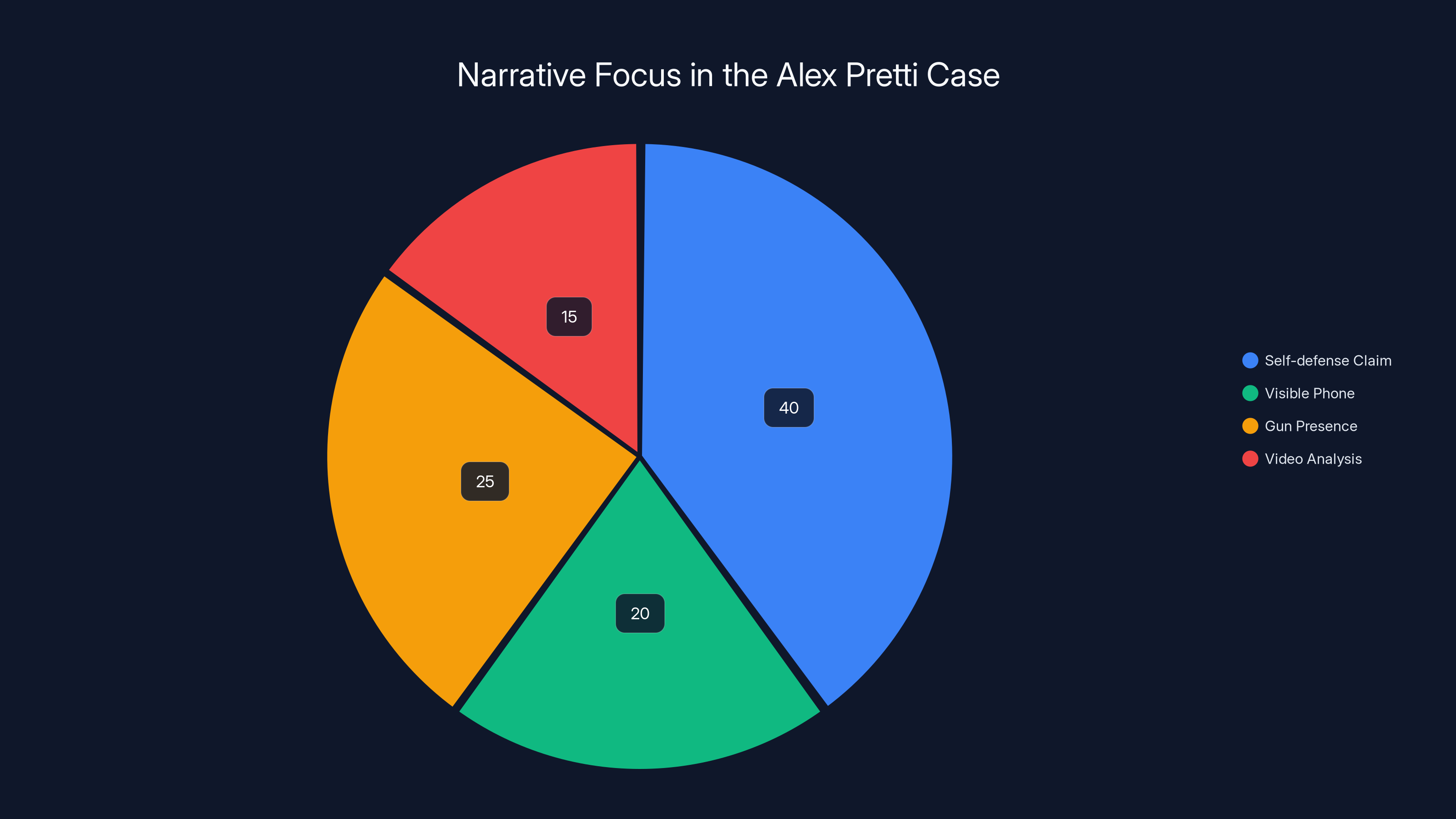

Federal Border Patrol and CBP agents encountered Pretti near Minneapolis. Multiple videos show him raising one hand and holding a phone in the other. He's then tackled by agents. One agent appears to remove a holstered gun from his hip. Shots follow—at least 9 to 11 rounds, with agents continuing to fire as Pretti lies on the ground, as reported by NBC News.

The Trump administration's official line: agents acted in self-defense. The legally carried gun justified the response. Case closed.

But the videos suggested something more complicated. Frame-by-frame analysis from major outlets showed Pretti wasn't in a shooting stance. His visible hand wasn't reaching for the weapon. The phone he held—his actual visible action in the seconds before he was shot—played no role in the administration's explanation. Instead, officials focused on the invisible gun while ignoring the visible phone, as detailed in NPR's report.

This was revealing. Why downplay the phone? Partly because it humanized Pretti. A man with a phone is someone documenting something. He's not an active threat. But also because the phone represented something more dangerous to the narrative: a tool that, in those final moments, Pretti was using to do exactly what the Trump administration now feared most—capture evidence.

The administration's response to Pretti's death wasn't to suppress the videos. By January 2025, suppression was impossible—the footage was already everywhere. Instead, officials did something more sophisticated: they offered their own angles, their own interpretations, their own facts to compete in the space where competing narratives exist.

This is the new game. Not suppression but distraction. Not denying the footage but drowning it in alternative narratives. If people are confused about what they saw, if they hear conflicting expert opinions, if they see selective angles that support the official story, then the baseline fact—what clearly happened—becomes negotiable again.

This is also where the administration's sophistication becomes apparent. Officials understood that you need to move fast. You need to speak the language of social media. You need to amplify through allied platforms. You need to reach people before they form strong conclusions. You need to make the story about competing interpretations rather than clear facts.

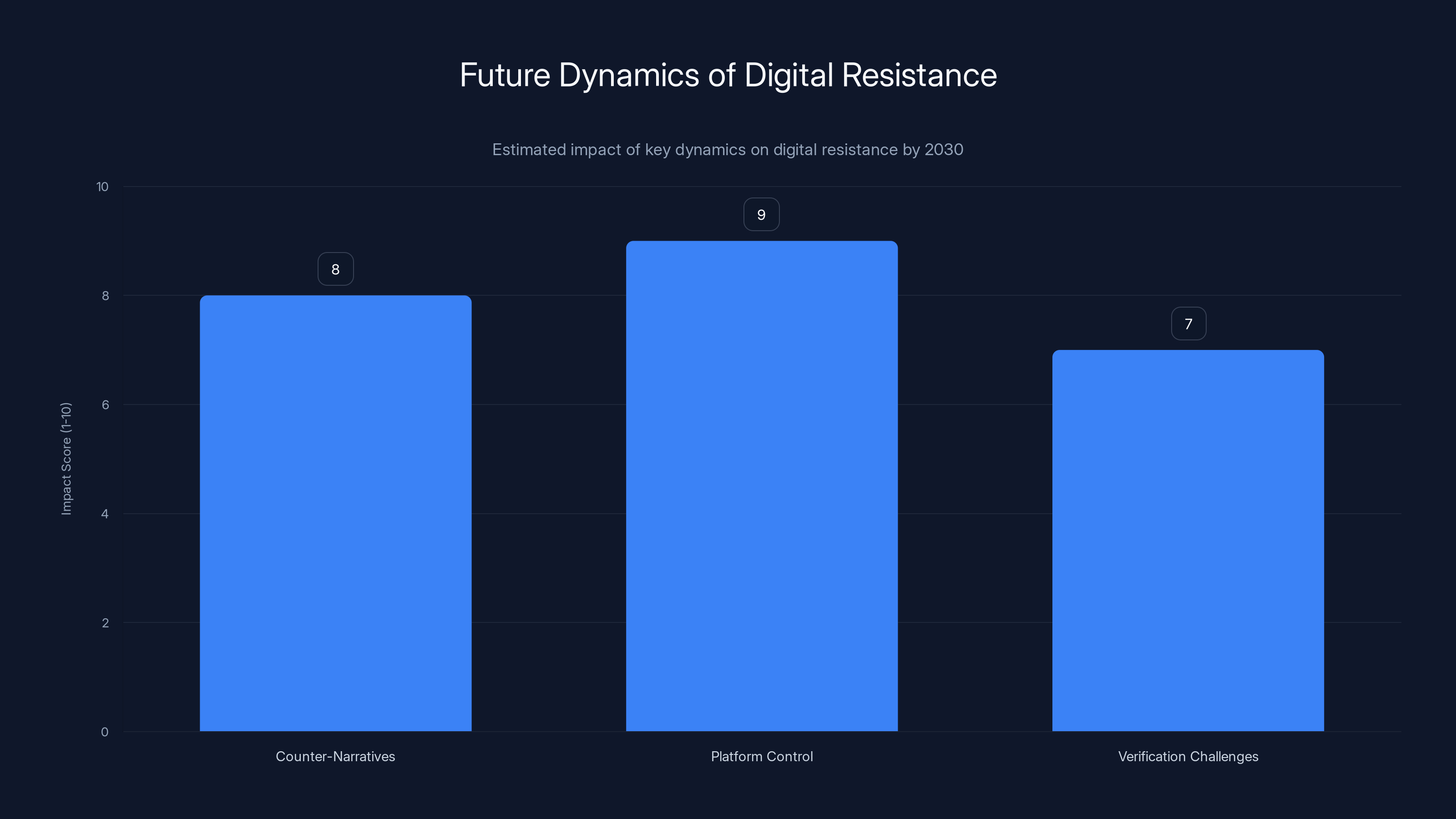

Estimated data suggests that platform control will have the highest impact on digital resistance by 2030, followed closely by counter-narratives and verification challenges.

The Renee Good Case: Selective Angles and Competing Reality

Before Pretti, another incident in Minneapolis became a test case for this new strategy. Federal agents shot and killed 37-year-old Renee Good. The official story: she drove her SUV at an agent, threatening his life.

One angle of the incident seemed to support this. A distant, grainy video showed a vehicle moving toward an agent. But more complete video evidence, filmed from closer angles, told a different story. Multiple analysis showed the agent wasn't in the path of the vehicle when he fired three shots at close range.

When this fuller evidence emerged, the Trump administration didn't wait for it to become the dominant narrative. They moved fast. A Truth Social post claimed Good had "viciously ran over the ICE Officer." The post included a single, distant, grainy angle that could be misinterpreted. The post's framing—emphasizing one detail while omitting others—shaped how people perceived the fuller evidence when they encountered it later.

This is the sophistication: not suppression but framing. You don't need to prevent people from seeing evidence. You just need to tell them what to see when they look at it. You need to reach them first with the interpretation. You need to turn "watch the video yourself" into "I already know what the video shows."

The strategy mirrors something that had proven effective in other contexts: the use of selective memes, simplified narratives, and rapid-fire social media posts to shape interpretation before people encounter the primary evidence.

The Asymmetry: Phones as Distributed Sensors vs. Centralized State Power

The fundamental asymmetry in digital resistance comes down to physics and distribution.

A government possesses concentrated power. It controls specific institutions, specific buildings, specific personnel. To suppress resistance, it can exert force at those nodes. It can arrest people. It can freeze assets. It can monopolize official channels.

But a population with phones possesses distributed power. Each person is a sensor, a broadcaster, a node in a network that has no center and no kill switch. To suppress distributed documentation, authorities would need to control billions of devices, which is technically impossible.

This is why authoritarian governments consistently move to control platforms and devices rather than suppress the act of documentation itself. China requires phones to run surveillance software. Russia pressures platforms to remove content. North Korea restricts phone use entirely. These are responses to the fundamental problem: you can't prevent people from documenting if they have the tools.

The Trump administration has shown itself savvy about this asymmetry in different ways. Rather than trying to suppress phones, they've allied with or created platforms they believe they can influence. They've cultivated relationships with influencers who can amplify preferred narratives. They've learned to communicate in the language of social media—memes, rapid-fire posts, simplified claims that fit the structure of how viral content spreads.

But they've also shown willingness to use state power against documentation in other ways. This includes pressuring platforms, threatening journalists who cover inconvenient facts, and creating legal liability for those who film in certain contexts. The target isn't the phones themselves but the people holding them.

How the Trump Administration Learned to Shape Narratives

The Trump administration's approach to digital resistance didn't emerge in 2025. It was refined through the first Trump term and developed further during the Biden years.

In 2020, the administration faced the George Floyd video. It couldn't suppress it. Instead, officials offered alternatives: "he resisted arrest," "he had drugs in his system," "the officer was defending himself." None of these claims changed what the video clearly showed, but they provided alternative interpretive frames that some audiences adopted.

Trump himself became fluent in social media communication in ways previous politicians weren't. Rather than waiting for official channels and press secretaries, he could post directly to millions. He could frame events in real-time. He could respond to criticism immediately. He could make claims that would seem false if spoken by anyone else but carried a different weight when posted with the authority of the presidency behind them.

This learned skill became crucial. When controversial events occurred, Trump or his administration could shape the initial perception. By the time fact-checkers or journalists worked through what actually happened, the narrative had already reached millions and taken root in people's minds.

What's particularly sophisticated about this approach is that it doesn't require falsehood, strictly speaking. It requires selective emphasis. It requires choosing certain true details while omitting others. The Renee Good post was technically true—an agent's life may have been in danger, even if not from where the selective video suggested. It wasn't a lie. It was a story told in a way designed to influence perception.

This distinction matters because it makes the strategy harder to counter. Fact-checkers can't simply declare it false. Journalists can point out missing context, but the initial framing has already worked. And in a fragmented media environment where people consume news through different sources, many people will never see the full context.

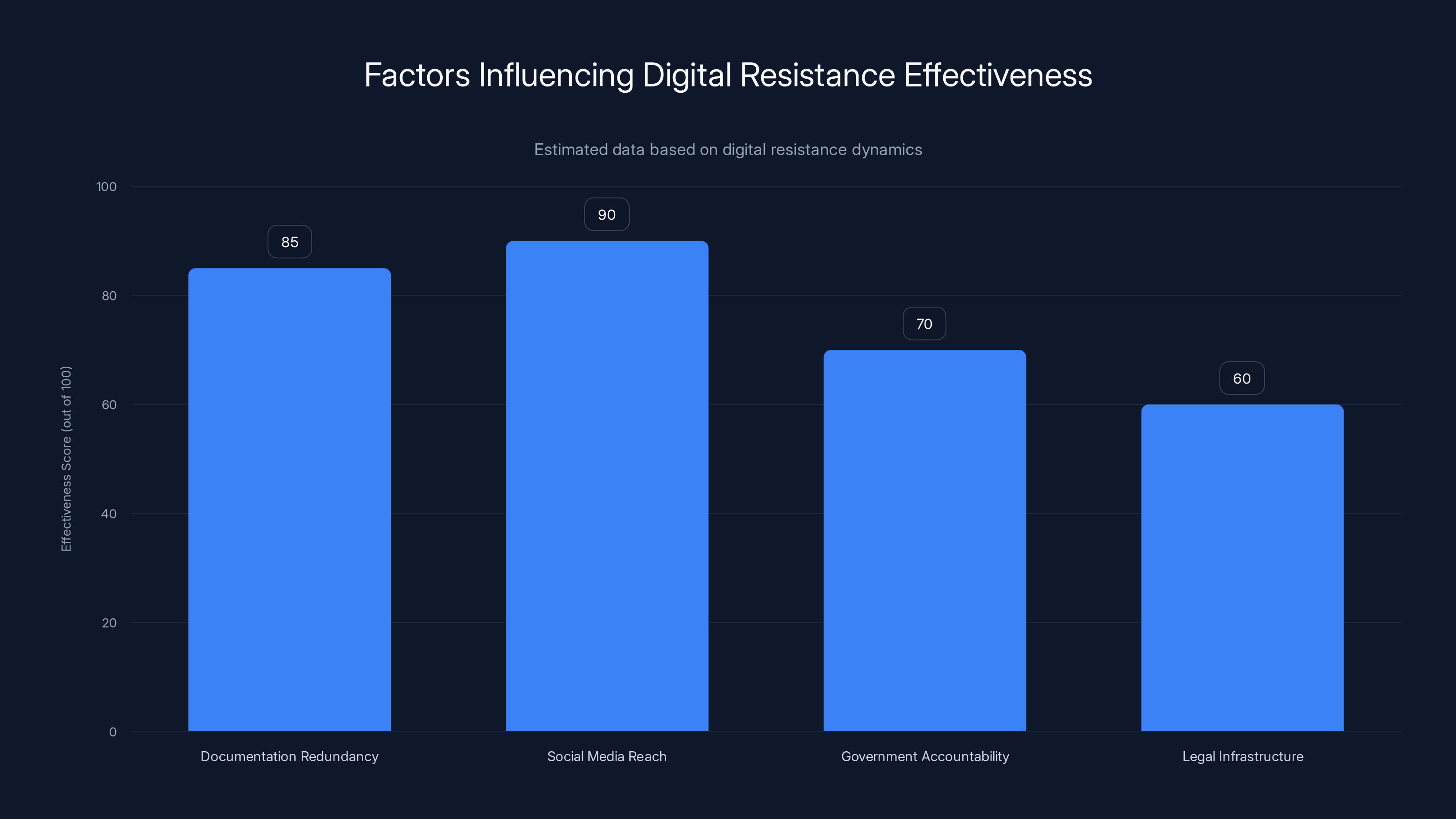

Digital resistance effectiveness is highest with strong social media reach and documentation redundancy. Estimated data.

The Role of Allied Platforms and Influencers

Another element of the administration's strategy involves platform control and influencer relationships.

Trump's social media presence exists largely on Truth Social, a platform he owns. This gives him advantages over traditional Twitter or Facebook: he can't be suspended or fact-checked by an external authority. His posts reach his followers directly. The platform's incentives align with his political goals.

More broadly, the administration has cultivated relationships with major figures on other platforms—streamers, podcast hosts, content creators—who amplify preferred narratives. These influencers reach younger audiences that traditional media doesn't reach. They operate in spaces where formal fact-checking is less common. Their authority comes from appearing trustworthy and peer-like, not institutional.

This matters for digital resistance because it demonstrates that the asymmetry isn't absolute. Governments have learned to build their own distributed networks of amplification. They can't suppress phones, but they can out-speak them if they're sophisticated about it.

The question becomes: who reaches people first? Whose framing does someone encounter before they encounter the primary evidence? In a world where cognitive resources are finite and people rely on trusted sources, the speed and credibility of competing narratives matters enormously.

The Technical Sophistication of Information Warfare

What's emerged by 2025 is something that wasn't fully developed in 2020: sophisticated information warfare that uses government resources, allied platforms, and influencer networks to shape perception of distributed documentation.

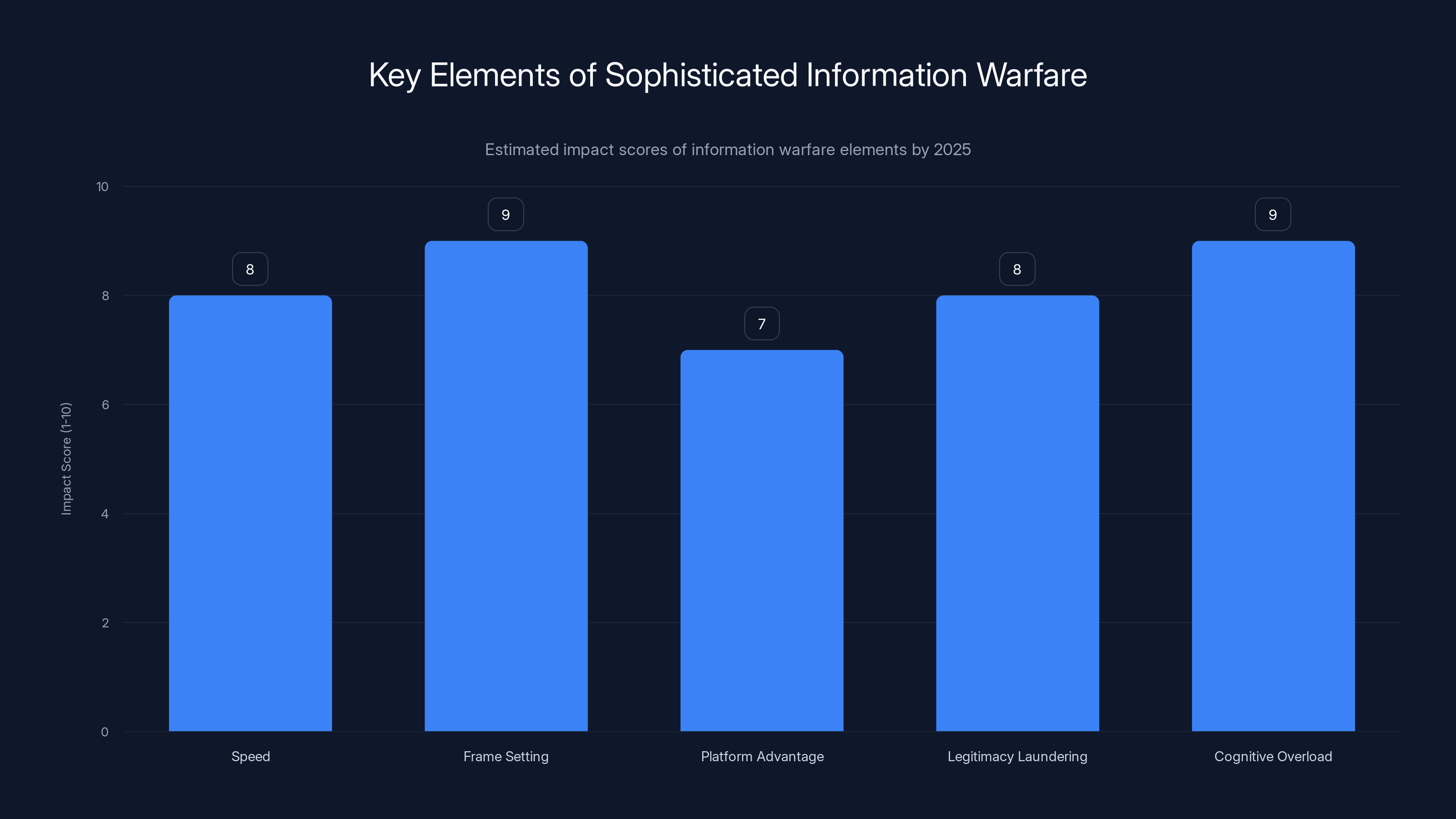

This isn't crude propaganda. It's elegant and distributed. It works by:

1. Speed: Reaching audiences before they've formed strong opinions on what they saw.

2. Frame Setting: Offering interpretive frames that people apply to the evidence ("look at this angle") rather than claiming the evidence shows something different.

3. Platform Advantage: Using owned platforms and allied influencers to amplify preferred narratives.

4. Legitimacy Laundering: Relying on trusted figures to repeat claims, making them seem less like government propaganda and more like peer communication.

5. Cognitive Overload: Creating so many competing narratives that people give up on determining truth and retreat to tribal belief.

What makes this sophisticated is that each element is deniable. The government isn't suppressing speech—it's exercising its own right to speak. Influencers aren't paid propagandists—they're sharing their genuine opinions. Platforms aren't censoring—they're making independent editorial choices. Yet the aggregate effect is a coordinated system that shapes perception.

This is particularly effective because it works with human psychology rather than against it. People don't generally watch video evidence frame-by-frame and draw independent conclusions. They encounter frames provided by trusted sources. They defer to expertise. They pattern-match to similar situations they've heard about. The system works by providing those frames, that expertise, those patterns.

The Parallel Case of Renee Good: Multiple Videos, Competing Frames

The shooting death of Renee Good in January 2025 provides a detailed case study of how this system works in practice.

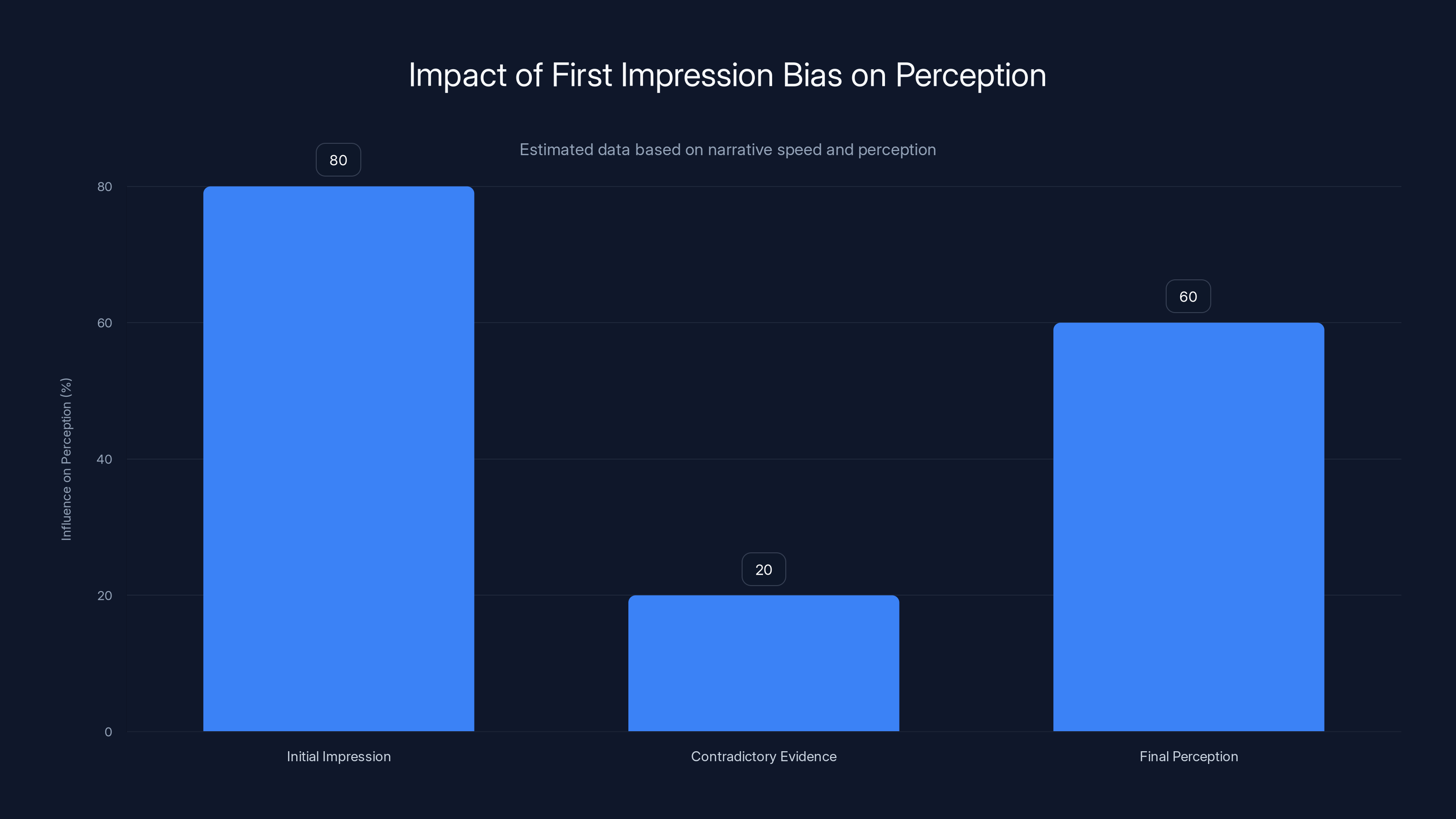

When Good's SUV incident occurred, federal agents involved in the shooting had an immediate advantage: they controlled the first official statement. Their account reached certain audiences before alternative narratives emerged. "Agent in danger." "Defensive shooting." These frames entered people's minds before video evidence became widely available.

When video evidence did emerge, it was fragmented. Some angles seemed to support the official narrative. Others contradicted it. People who wanted to believe the official story could point to the angles that supported it. People skeptical of federal agents could point to the contradicting footage.

The Trump administration didn't need to suppress all the video. They needed to ensure that when people encountered it, they'd already been primed with an interpretation. The Truth Social post with the selective angle served that purpose. It said: "here's what the video shows" before most people had seen any version of the video.

This matters because first impressions are sticky. If you believe based on a selective angle that the agent was in danger, you'll interpret more complete footage through that lens. You'll notice details that support your initial belief. You'll give the agent benefit of the doubt. You'll find ways to make the full evidence fit your frame.

And importantly, even if you later learn the agent wasn't actually in the vehicle's path, by then you've likely moved on emotionally. The story didn't satisfy you—the news cycle moved on. You didn't deeply revise your understanding; you just accepted that it was complicated and controversial.

Estimated data shows that the self-defense claim dominated the narrative focus, while the visible phone and video analysis were less emphasized.

The First Amendment Paradox: Free Speech as Tool and Threat

There's a paradox at the heart of digital resistance that becomes apparent when looking at how the Trump administration uses free speech.

Civil liberties advocates have historically defended rights to record and document based on First Amendment principles. The right to record is the right to speak, to share information, to hold power accountable through documentation.

But the Trump administration has shown that free speech can also be a tool of power when deployed strategically. Official government accounts can spread falsehoods or selective framings. Cabinet secretaries can use massive platforms to amplify preferred narratives. The president can post directly to millions, shaping perception in real-time.

The First Amendment protects all of this. It protects the person recording on their phone. It also protects the government official making counterclaims on social media. It protects the influencer sharing the official narrative. It protects the journalist fact-checking both. Everyone has the right to speak.

But these aren't equal voices in a vacuum. The government has institutional resources, platforms, and credibility that individuals don't possess. It can coordinate messaging in ways distributed phones can't. It can reach audiences at scale through official channels.

So digital resistance isn't about a right to speak—that's guaranteed. It's about an asymmetry in who gets heard, whose frame gets adopted, whose narrative reaches people first. The phone is a powerful tool, but it's most powerful in a vacuum. When aligned against a government that's learned to speak fluently in social media language, to move quickly, to use platforms and influencers, the asymmetry becomes less stark.

This doesn't mean phones are useless. The redundancy still matters. The speed of distribution still counts. But it's no longer obvious that documentation equals accountability.

Lessons from 2020: What Worked and What Didn't

The George Floyd moment in 2020 is instructive because it shows both the power and limitations of distributed documentation without sophisticated counter-narrative strategies.

Multiple videos of Floyd's death existed within hours. They reached millions within the first day. News organizations couldn't avoid covering it because everyone had already seen it. The footage was so clear, so widely distributed, that the baseline facts were established before official narratives could effectively contest them.

This led to tangible results. Derek Chauvin was convicted. Police reform became a mainstream discussion. Consequences occurred.

But five years later, the changes were mixed at best. Police reform proved harder than expected. Specific officers faced consequences but systemic change was limited. Public attention moved on quickly. The video, for all its power, didn't prevent subsequent police killings or systemic violence. It documented and amplified, but the documentary power had limits.

One lesson is that documentation, however powerful, doesn't automatically lead to systemic change. Changing institutions requires different tools: organizing, political pressure, legal liability, resource allocation. A video can start those processes, but it can't complete them alone.

Another lesson is that systems adapted. By 2022 and beyond, police agencies had learned that they couldn't suppress documentation. They learned that controlling narratives required engaging with the documentation directly, offering alternative frames, responding through social media, building their own narrative infrastructure.

The Trump administration came to office having watched these dynamics play out. They understood that the era of suppression was over but that the era of sophisticated counter-narrative was available. They could see that governments could out-speak distributed phones if they were smart about it.

The Role of News Organizations in Validating Distributed Evidence

News organizations play a crucial but complicated role in validating distributed documentation.

When the New York Times analyzes the Pretti footage frame-by-frame, it does something important: it brings institutional credibility and technical resources to bear on video that exists in fragments across the internet. The Times' analysis carries weight with audiences who trust the institution. Its frame-by-frame breakdown makes details visible that casual viewers might miss.

This is valuable. But it also creates a dependency. Ordinary people's observations become legitimate when validated by major institutions. The opposite is also true: when major institutions don't validate or don't engage with distributed documentation, it can remain marginal.

This creates a relationship where traditional media organizations become gatekeepers of sorts—not preventing information from spreading, but determining which information gets treated as significant, credible, important. News organizations can amplify distributed documentation or relegate it to fringe status.

The Trump administration understands this too. When they can get favorable coverage in outlets with credibility, they can shape how major institutions frame the evidence. When they can't get favorable coverage, they build alternative institutions and platforms that offer their frame to audiences that distrust traditional media.

This is where the asymmetry becomes most apparent. Distributed phones can capture evidence, but that evidence doesn't become widely believed or acted upon without institutional validation. Governments, having access to more institutional resources, have more power to get that validation or create alternative institutions that provide it.

Estimated data shows that initial impressions heavily influence perception, even when later evidence contradicts them. This highlights the power of narrative speed over narrative truth.

The Future of Digital Resistance: What's Possible and What's Limited

Looking forward from 2025, the future of digital resistance likely involves three simultaneous dynamics:

1. Increasing Sophistication of Counter-Narratives: Governments will continue to develop more sophisticated strategies for framing distributed documentation. This includes faster response times, better integration with influencer networks, more strategic use of platform algorithms, and more elegant selective framings.

2. Platform Concentration and Control: The ability to shape narratives depends on controlling or influencing platforms. Expect continued consolidation around platforms that align with government interests and continued attempts to marginalize platforms that don't.

3. Verification and Credibility Challenges: As deepfakes and synthetic media become more sophisticated, the ability to trust visual documentation diminishes. This paradoxically benefits those controlling institutions—"trust me" becomes harder for everyone, but governments can fall back on institutional authority while individuals can't.

What remains uncertain is whether distributed documentation will maintain its power through these changes or whether sophisticated counter-narratives will eventually win out. The answer probably depends on how people receive and process information, which changes generationally and culturally.

Some audiences will always trust distributed, user-generated documentation over official narratives. Others will increasingly defer to institutions and platforms they trust. The ecosystem will likely fragment further, with different information sources reaching different populations, making shared understanding of basic facts harder.

In that environment, phones remain powerful. But power shifts from the act of documentation to the infrastructure that validates, amplifies, and disseminates documentation. And infrastructure requires resources, relationships, and institutional capacity that distributed phones alone don't provide.

The Biden Administration's Approach: Media Management Without Suppression

It's worth noting that the challenges of digital resistance aren't unique to the Trump administration, though they may be more acute.

The Biden administration also faced pressure from distributed documentation. During withdrawal from Afghanistan, videos of chaos at Kabul airport spread globally. The administration's response involved public statements, controlled narratives from officials, and coordinated messaging through allied media. They didn't suppress the videos. They provided competing frames.

Similarly, when ICE operations occurred under Biden, videos spread. The administration didn't prevent documentation. They offered their own interpretations of immigration enforcement, refugee policy, and border security through official channels and friendly media.

The difference with the Trump administration is partly one of style and speed. Trump has shown greater willingness to engage directly on social media, to move fast, to speak in the language of internet culture. But the fundamental strategy—don't suppress documentation, shape how people understand it—isn't unique to one administration.

This suggests that digital resistance will remain asymmetrical regardless of which party controls power. Those with institutional resources will always have advantages in shaping narratives. The phone's power comes from redundancy and speed, but those advantages persist only if the frame being offered makes sense to the people receiving it.

What Phones Can and Can't Do: Realistic Assessment

After examining the role of phones in documenting government actions, it's important to be clear about what they can and can't accomplish.

What phones can do:

- Create redundant documentation that can't be fully suppressed

- Reach audiences faster than traditional media

- Provide evidence of baseline facts that makes certain claims impossible

- Empower ordinary people to participate in narrative creation

- Create pressure for official responses and explanations

- Make events visible to people far away who otherwise wouldn't know

What phones can't do:

- Determine interpretation of evidence without supporting infrastructure

- Change institutional behavior without political pressure

- Prevent governments from offering competing narratives

- Guarantee that evidence leads to accountability

- Function without trust in the people doing the documentation

- Overcome systematic power imbalances in who gets heard

This realistic assessment is important because phone documentation has become almost mythologized. The implicit belief that "cameras solve everything" has taken root in some activist circles. But the Pretti case shows the limits. Multiple clear videos didn't prevent the shooting. They didn't immediately lead to charges. They led to competing narratives about what happened, which is different from accountability.

Documentation is a necessary condition for accountability but not a sufficient one. It requires supporting institutions, political will, legal infrastructure, and public movement. Phones remove the excuse of "we didn't know." They can't force the next steps.

By 2025, elements like Frame Setting and Cognitive Overload are estimated to have the highest impact in information warfare due to their subtlety and psychological alignment. (Estimated data)

The Role of Citizen Journalism and Accountability Infrastructure

One factor that amplifies the power of distributed documentation is the emergence of citizen journalism and accountability infrastructure built specifically to process, validate, and amplify documentation.

Organizations like the Innocence Project use video documentation to exonerate the wrongly convicted. Civil rights groups build databases of police violence. Investigative outlets like Pro Publica match distributed video with official records to fact-check government claims. These infrastructure organizations take raw documentation and transform it into accountability.

Without this infrastructure, videos spread but often don't lead anywhere. With it, videos become evidence that feeds into legal cases, policy changes, and public understanding.

The sophistication of this infrastructure varies by issue area. Police violence documentation has robust infrastructure—established organizations, legal frameworks, and media outlets dedicated to processing it. Immigration enforcement documentation is less developed, though growing. Other areas of government action have almost no infrastructure to process and validate documentation.

This matters because it suggests that future digital resistance won't be just about capturing evidence but about building the infrastructure to make that evidence matter. The phone is one part of a larger system that requires organizations, lawyers, journalists, and public will.

Protecting Documentation: Legal Frameworks and Limitations

The right to record government agents in public spaces is established in US law, with important limitations.

Generally, you can record police and federal agents in public without consent. This right comes from First Amendment protections and has been upheld in multiple court cases. You don't need permission. You don't need a license.

But this right has edges. You can be asked to stand in certain locations (not obstructing). You can be ordered to cease recording if it's interfering with an emergency. You can theoretically be arrested if the arrest is pretextual but recorded for other reasons. The boundaries aren't always clear, and enforcement is inconsistent.

What's changed is that governments have learned to work within these boundaries. Rather than suppressing phones directly, they can pressure people not to record by treating recording itself as suspicious. They can arrest someone for other charges and note that they were recording at the time. They can create environments where recording feels risky.

Protecting documentation requires clarifying these legal boundaries, training people about their rights, and building legal defense infrastructure. It also requires platforms that are willing to host documentation without pressure to remove it, which isn't guaranteed.

The future of digital resistance will partly depend on how protective legal frameworks and platforms remain. If the boundaries narrow or if platforms become less protective, the power of documentation diminishes.

The Global Perspective: Different Frameworks in Different Countries

The role of phones in digital resistance varies significantly by country, based on legal frameworks, platform access, and government sophistication in managing distributed documentation.

In China, phone use is heavily surveilled and restricted. People can record but must be careful about where footage goes. Distributed documentation remains possible but risky. The government has sophisticated facial recognition and tracking capabilities, making documentation potentially dangerous for the documenter.

In Russia, documentation of government actions is increasingly restricted. Laws against "extremism" and "misinformation" create legal risk for people sharing video that contradicts official narratives. Platforms are pressured to remove content. Documentation remains possible but faces both technical and legal obstacles.

In democratic countries with stronger free speech protections, documentation is legal but still faces pressure. The US, despite First Amendment protections, has seen increasing attempts to criminalize or restrict documentation of police and government agents.

What's interesting is that even in countries without strong legal protections, the redundancy of distributed documentation creates challenges for governments. They can suppress some videos, but others persist. They can punish some documenters, but others record. The system has enough redundancy to remain functional, though at greater cost to those doing the documenting.

This suggests that digital resistance is fundamentally asymmetrical in ways that depend on legal and political context. In more restrictive environments, the asymmetry is steeper. In democratic environments, the asymmetry is smaller but still significant.

The Synthetic Media Challenge: Deepfakes and Credibility Crises

One emerging challenge to the power of documentation is the rise of deepfakes and synthetic media. If footage can be created rather than captured, the ability to trust video documentation diminishes.

This benefits governments and institutional authorities. When anyone can claim "that video is fake," the credibility of all video declines. But institutions can fall back on formal credibility and institutional endorsement. A New York Times investigation still carries weight even if synthetic media exists. Institutional processes still matter.

For distributed documentation, synthetic media is more destabilizing. If people don't trust that a phone video is real, the power of documentation collapses. This is where timestamp verification, blockchain-based authentication, and other technical solutions might matter. But they're not yet widely adopted or trusted.

The synthetic media challenge is likely to favor those with institutional resources and credibility. It creates incentive to trust institutions over distributed sources, which reverses the trend of the past decade where distributed documentation seemed to be gaining power.

This suggests that the future power of documentation depends on solving credibility problems. Technical solutions exist but aren't mainstream. Institutional solutions (trusting certain outlets) are mature but slow. Distributed solutions (peer verification, community credibility) are emerging but not fully developed.

Building Resilient Documentation Systems

For digital resistance to remain powerful, the documentation systems need to be resilient to suppression attempts, synthetic media challenges, and counter-narrative strategies.

Key elements of resilience include:

1. Redundancy: Multiple angles, multiple platforms, multiple copies. If documentation exists in hundreds of versions, suppression becomes nearly impossible.

2. Decentralization: Storing documentation on decentralized platforms or peer-to-peer networks reduces reliance on corporate platforms that can be pressured.

3. Verification Infrastructure: Building trusted systems for verifying that documentation is authentic and timestamp-accurate.

4. Legal Protection: Ensuring that rights to record are clear and that legal liability is minimized for documenters.

5. Institutional Integration: Connecting documentation to organizations that can process it, validate it, and use it for accountability.

6. Community Trust: Building community capacity to understand documentation without having to defer to institutional experts.

No single element is sufficient. Phones alone can't achieve this. But phones plus institutional support, legal protection, and verification infrastructure can create systems that are difficult to suppress or counter.

This is the work ahead for those committed to digital resistance: not just documenting but building the infrastructure that makes documentation matter.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Tension Between Documentation and Suppression

The phone in Alex Pretti's hand moments before his death symbolizes something larger than that specific incident. It represents the ongoing tension between the power to document and the power to suppress or control narratives about that documentation.

What we've seen over the past five years is that the era of simple suppression is over. Governments can't suppress distributed phones. But the era of straightforward documentary power isn't guaranteed either. Governments have learned to move fast, to shape frames, to amplify preferred narratives through platforms and influencers, to make competing interpretations seem credible.

The asymmetry hasn't disappeared. It's shifted. Instead of a battle over whether documentation happens, it's become a battle over how documentation is interpreted. Instead of preventing evidence from existing, it's about getting audiences to understand that evidence through particular frames.

This creates ongoing friction. Documentation remains powerful because baseline facts still constrain possible narratives. You can't claim a gun wasn't drawn if clear video shows it was. You can't claim an agent wasn't firing if multiple angles confirm it. The camera removes certain false claims from possibility.

But within the constraint of documented facts, interpretation remains contested. Was the agent in danger? Was the person an immediate threat? What would you have done in that situation? These questions have evidence-constrained answers, but the evidence doesn't answer them alone.

The future of digital resistance lies in understanding this nuance. Phones are powerful tools. Documentation matters. But power isn't determined by documentation alone. It's determined by documentation plus infrastructure, verification, interpretation, and political will.

For those seeking accountability, this means the work isn't just to document but to build the systems that make documentation matter. For governments seeking to maintain legitimacy, it means the work isn't suppression but interpretation management.

The phone remains in billions of hands. It's still a tool of resistance. But like all tools, its power depends on how it's used and what it's connected to. That balance will likely determine the nature of accountability and power in the years ahead.

FAQ

What is digital resistance?

Digital resistance is the use of phones, cameras, and social media to document government actions, hold authorities accountable, and distribute evidence across networks that can't be fully suppressed. It represents a shift from traditional protest or legal action to real-time documentation that makes events visible to distant audiences and creates a record that officials must address.

How does distributed documentation create accountability?

Distributed documentation removes certain false claims from possibility. When multiple videos show what happened, officials can't deny basic facts like "the shooting never occurred" or "the agent wasn't present." This constrains possible narratives and forces officials to engage with evidence rather than dismiss it. However, documentation doesn't automatically lead to punishment—it requires supporting legal, political, and institutional infrastructure.

Why can't governments simply suppress video documentation?

Suppression is nearly impossible because modern documentation is redundant by design. A single video spreads across multiple platforms, gets downloaded and re-shared, exists in different formats and backups. To suppress it completely would require controlling billions of phones and thousands of platforms simultaneously. Instead, governments have learned to offer competing narratives and interpretive frames around the documentation.

What's the difference between suppressing evidence and shaping interpretation of evidence?

Suppression means preventing people from seeing evidence (censoring, deleting, confiscating). Shaping interpretation means letting people see evidence but providing frames that influence how they understand it. The Trump administration has shown this distinction clearly—they don't try to remove videos; they offer selective angles, alternative explanations, and rapid counter-narratives that shape what people believe when they encounter the documentation.

How has the power of phones changed since 2020?

In 2020, distributed documentation seemed to have straightforward power. The George Floyd video reached millions, led to conviction, sparked reform discussions. But five years later, it's clear that documentation's power is more limited. Reforms were watered down. Subsequent incidents still occurred. What changed is that governments learned to engage more sophisticatedly with documentation, to move faster with counter-narratives, and to shape interpretation rather than suppress evidence.

What role do platforms play in digital resistance?

Platforms determine which documentation spreads widely and which remains marginal. They also determine what happens when officials request removal. Platforms like YouTube and Facebook amplify content based on engagement algorithms, which means sensational or emotionally charged documentation spreads faster. This benefits both distributed documenters and coordinated counter-narratives. Platforms are neither neutral nor fully controllable by any single actor.

How do deepfakes and synthetic media challenge digital resistance?

If footage can be created rather than captured, the credibility of all video declines. This paradoxically benefits governments and institutions because they have more credibility resources to fall back on ("trust our verification process") while distributed documenters lose the assumption that phone video equals truth. Solving this requires verification infrastructure that doesn't yet exist at scale.

What legal protections exist for people recording government agents?

In the US, you generally have the right to record police and federal agents in public spaces without consent under First Amendment protections. However, these rights have limitations and edges. You can be ordered to move, arrested on other charges while recording, or face pressure that makes recording risky. Protecting documentation requires clarifying legal boundaries, training people about their rights, and building legal defense infrastructure.

What's the relationship between documentation and actual accountability?

Documentation is necessary but not sufficient for accountability. It removes excuses ("we didn't know") and constrains possible narratives. But it doesn't automatically lead to consequences. Creating accountability requires supporting infrastructure: legal systems willing to prosecute, political will to demand change, media outlets willing to investigate, and public movements willing to apply pressure. Phones start the process; other systems must complete it.

Where is digital resistance heading in the next few years?

Likely developments include more sophisticated counter-narrative strategies from governments, increasing platform concentration around outlets that align with government interests, and deepening challenges around video credibility as synthetic media improves. The power of documentation will probably depend less on the act of capturing evidence and more on having infrastructure to validate, amplify, and use that evidence for accountability. The asymmetry will shift but likely not disappear.

Key Takeaways

- Phones create redundant documentation that authorities can't fully suppress, but distributed evidence isn't the same as accountability

- Governments have evolved from suppression strategies to sophisticated narrative control through platforms, influencers, and selective framing

- The asymmetry between distributed phones and centralized power hasn't disappeared but has shifted toward interpretation management rather than information suppression

- Documentation requires supporting infrastructure including legal protection, institutional validation, and media engagement to translate evidence into actual consequences

- The future of digital resistance depends on building verification systems and institutional integration that make documented evidence matter politically and legally

Related Articles

- State Department Deletes X Posts Before Trump's Term: What It Means [2025]

- ICE Expansion and Government Transparency: What Communities Need to Know [2025]

- FCC Accused of Withholding DOGE Documents in Bad Faith [2025]

- Social Security Data Handover to ICE: A Dangerous Precedent [2025]

- EPA Revokes Greenhouse Gas Endangerment Finding: What It Means for Climate Policy [2025]

- Trump's EPA Kills Greenhouse Gas Regulations: What It Means [2025]

![Digital Resistance: How Video Evidence Challenges Government Power [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/digital-resistance-how-video-evidence-challenges-government-/image-1-1771083512311.jpg)