Introduction: The Digital Erasure of Government History

In early 2025, the State Department made a decision that sent ripples through government transparency advocates, digital archivists, and citizens concerned about institutional memory. The agency announced it would systematically delete all posts from its X (formerly Twitter) accounts that were published before President Trump's second term began. This isn't a minor housekeeping task or routine account cleanup. This is the removal of potentially hundreds of thousands of posts spanning multiple administrations, covering everything from diplomatic announcements to cultural exchanges to crisis communications.

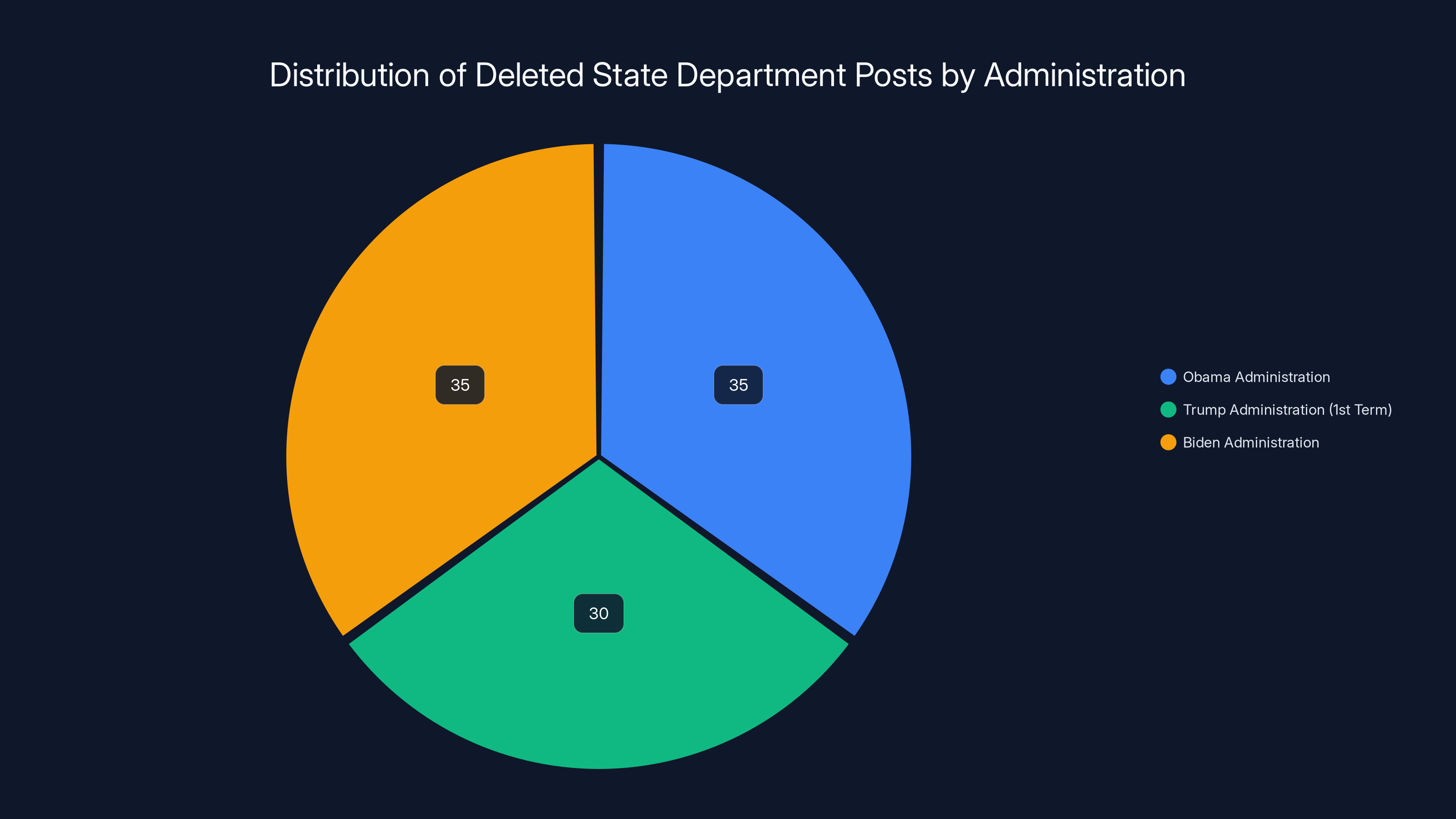

What makes this different from previous administration transitions is the deliberate choice to not maintain these posts in any public archive. In the past, when new administrations took over social media accounts, archived versions remained accessible through platforms like the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine or through official government records. But according to reporting from NPR, the State Department confirmed that accessing these deleted posts will now require filing a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request—a process that can take months or even years, and doesn't guarantee the information will be released at all.

The stated rationale from a State Department spokesperson was clear: the move is designed "to limit confusion on U.S. government policy and to speak with one voice to advance the President, Secretary, and Administration's goals and messaging." The same spokesperson characterized X accounts as "one of our most powerful tools for advancing the America First goals." On the surface, this sounds reasonable. New administrations do want to signal a fresh start. But dig deeper, and you'll find yourself in uncomfortable territory: questions about government transparency, institutional continuity, digital preservation, and what happens when the historical record gets rewritten in real time.

This article explores what's actually happening with the State Department's social media purge, why it matters beyond the obvious transparency concerns, how it fits into a broader pattern of digital information management by the current administration, and what the long-term implications might be for how Americans can access and understand their government's recent history. We'll also look at the legal and practical challenges FOIA requests create, examine parallels to previous administrations, and discuss what digital archivists and transparency experts are saying about this unprecedented move.

TL; DR

- The Purge: State Department is deleting all X posts from before Trump's second term without maintaining public archives

- Access Method: Only Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests can retrieve deleted posts; no timeline guarantees

- Scope: Affects multiple State Department accounts including embassy accounts spanning Obama, Biden, and Trump's first term

- Stated Reason: To "speak with one voice" on U.S. policy and advance "America First" messaging

- Historical Precedent: Previous administrations archived old posts; this breaks that pattern

- Bottom Line: This represents an unprecedented approach to managing government social media records and raises serious questions about transparency and institutional memory

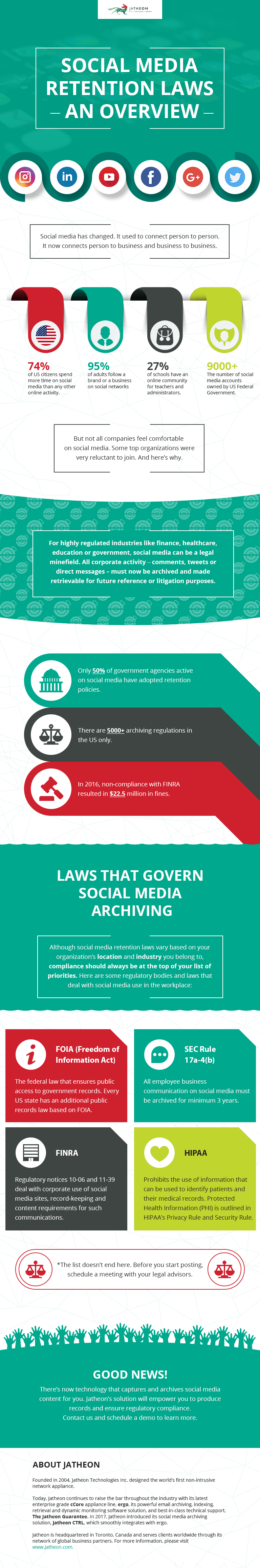

The @StateDept account alone has posted an estimated 23,000 tweets over 16 years. When combined with regional, initiative, and embassy accounts, the total volume could reach hundreds of thousands, highlighting the extensive communication efforts of the State Department. Estimated data.

Understanding the Scale: How Many Posts Are We Talking About?

Before we can really grasp what's happening here, we need to understand the sheer volume of content at stake. The State Department's X presence isn't just a single account run by one person in a basement office. It's an entire ecosystem of accounts across different departments, regional bureaus, and embassy operations worldwide.

The primary account, @StateDept, has been active since 2009 and has accumulated millions of tweets over that 16-year period. But that's just the flagship. There are dozens of other official State Department accounts: @PressSec_State for press releases, regional accounts covering Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, accounts for specific initiatives like the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, and then there are the individual embassy accounts. The United States has 195 foreign missions, and many of them maintain their own X accounts providing real-time updates on everything from visa processing to earthquake response.

Consider the math. If the main account has posted roughly 3-5 times per day on average over 16 years, that's somewhere between 17,000 and 29,000 posts from that single account alone. Multiply that across 50+ official State Department and embassy accounts, and you're looking at potentially hundreds of thousands of posts spanning multiple presidential administrations.

What makes this number significant isn't just the raw count. It's what those posts represent. They're primary source documents. They're records of how the U.S. government communicated with the world during major events: the Syrian refugee crisis, Russian interference in elections, the Abraham Accords, COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy, climate negotiations, the Afghanistan withdrawal. When historians want to understand how government officials were publicly framing issues in real-time, X posts provide that unfiltered window.

According to reports from digital preservation organizations, the State Department's X accounts represent one of the most consistently updated government information sources about U.S. foreign policy. Deleting that content without proper archiving is like burning chapters out of a book while claiming you're just reorganizing the library.

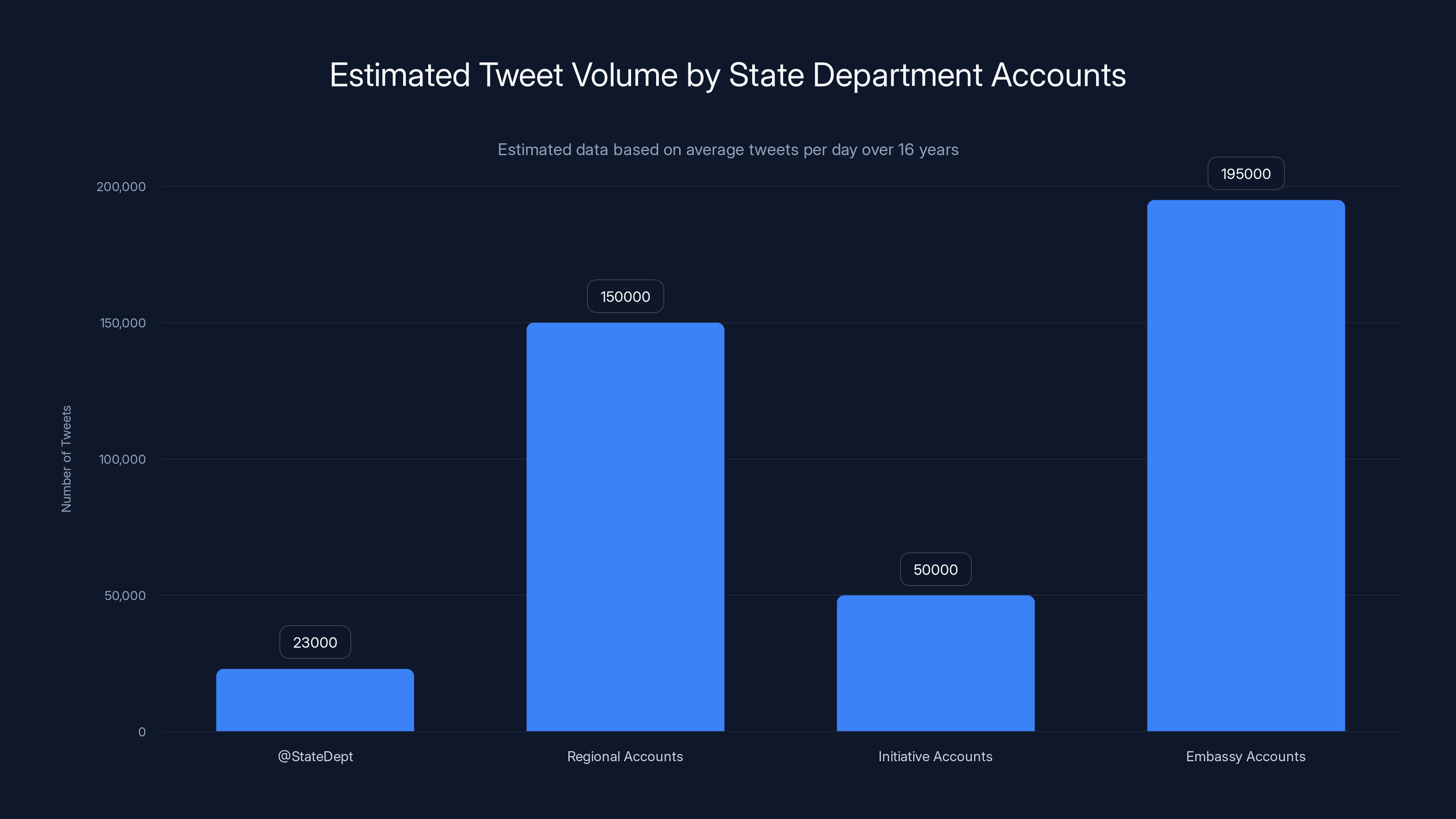

Estimated data suggests an even distribution of deleted posts across the Obama, Trump (1st term), and Biden administrations, reflecting a temporal rather than administrative focus.

The FOIA Workaround: Why It's Not a Real Solution

When the State Department spokesperson explained that deleted posts could still be accessed "through FOIA requests," it might sound like a reasonable compromise. After all, the Freedom of Information Act is literally designed to let citizens request government documents. So can't people just file a FOIA request for old tweets, get them back, and everyone goes home happy?

Not quite. Here's where the devil lives in the details.

A FOIA request is not a magic wand that instantly retrieves information. It's a formal legal process with specific timelines, classifications, and potential denials. When you submit a FOIA request to the State Department, a few things happen. First, it gets logged and assigned to the appropriate department or bureau. Then, that department has to identify all responsive documents—and yes, X posts would theoretically qualify as documents since they're government records. Next comes the fun part: review.

State Department officials will review each document to determine if anything in it qualifies for exemption under FOIA. There are nine broad exemptions to FOIA disclosure, including classified information, trade secrets, personal privacy, and attorney-client privileged communications. Even though most State Department X posts are public (because they were posted on a public platform), the FOIA process still requires line-by-line review to ensure nothing sensitive gets released.

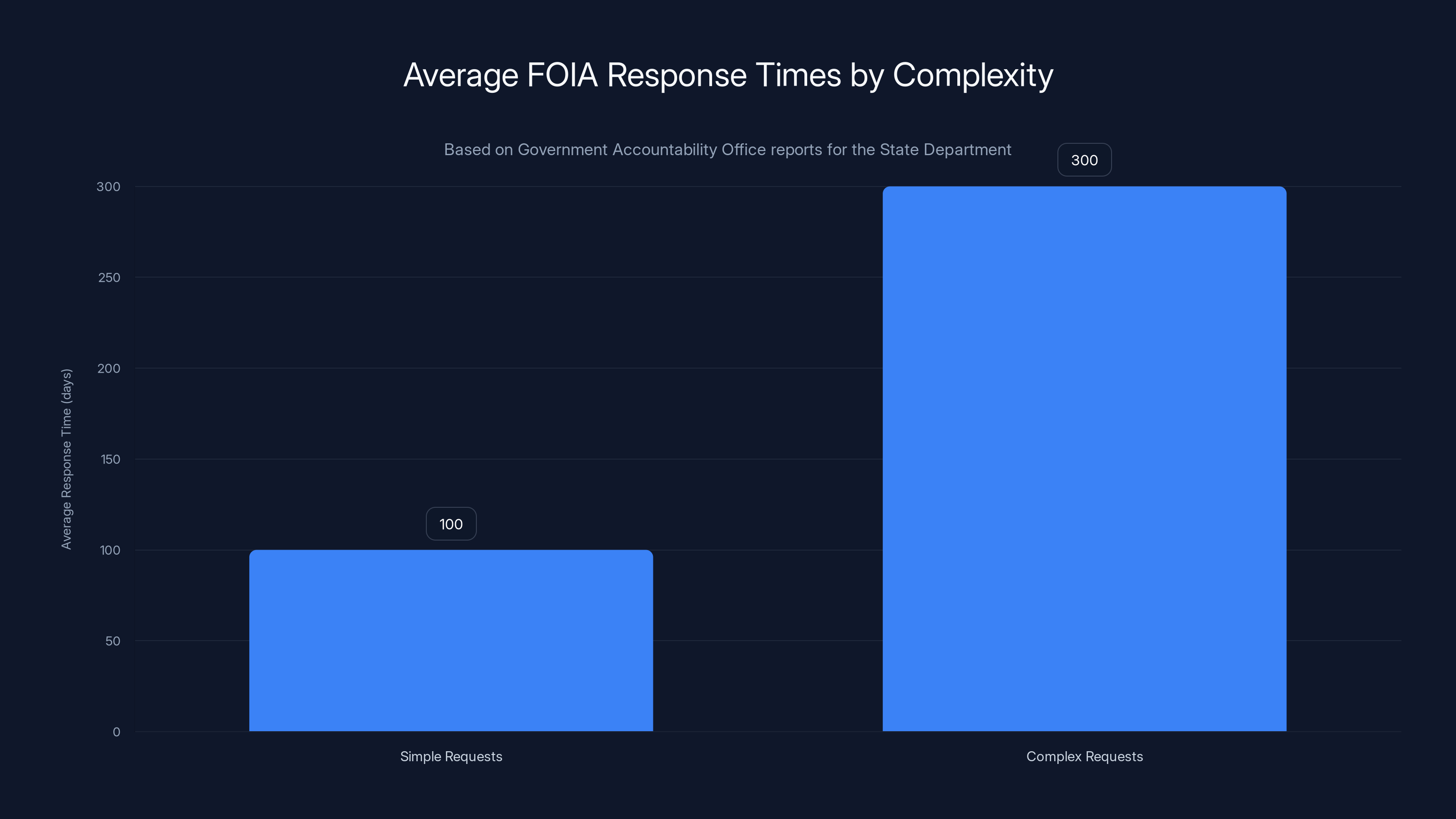

Then there's the timeline issue. The State Department, like most federal agencies, is perpetually understaffed in its FOIA office. The statutory deadline for responding to a FOIA request is 20 business days, but agencies routinely ask for extensions. In practice, requests for large batches of documents can take months or even years. The Government Accountability Office reports that the average FOIA response time for the State Department specifically is now over 100 days for simple requests and 300+ days for complex ones. If you request records about a specific embassy's activity during a particular year, you could be waiting until 2026 or beyond.

And here's the kicker: FOIA requests are reactive, not proactive. The burden is entirely on citizens to know what they're looking for and ask for it by name or description. Researchers and historians won't discover new information by browsing through old tweets the way they could if those tweets remained publicly visible online. The difference between "let me scroll through the archives" and "let me file a formal request and wait six months" is the difference between historical research and a bureaucratic scavenger hunt.

There's also the precedent this sets. If the State Department can delete social media without maintaining public archives because citizens can theoretically FOIA them later, what's to stop other agencies from doing the same? A leaked document or a controversial memo could be removed from public view and tucked away in FOIA land, accessible only to those persistent enough to navigate the process.

The Broader Pattern: How This Fits Into the Trump Administration's Information Management

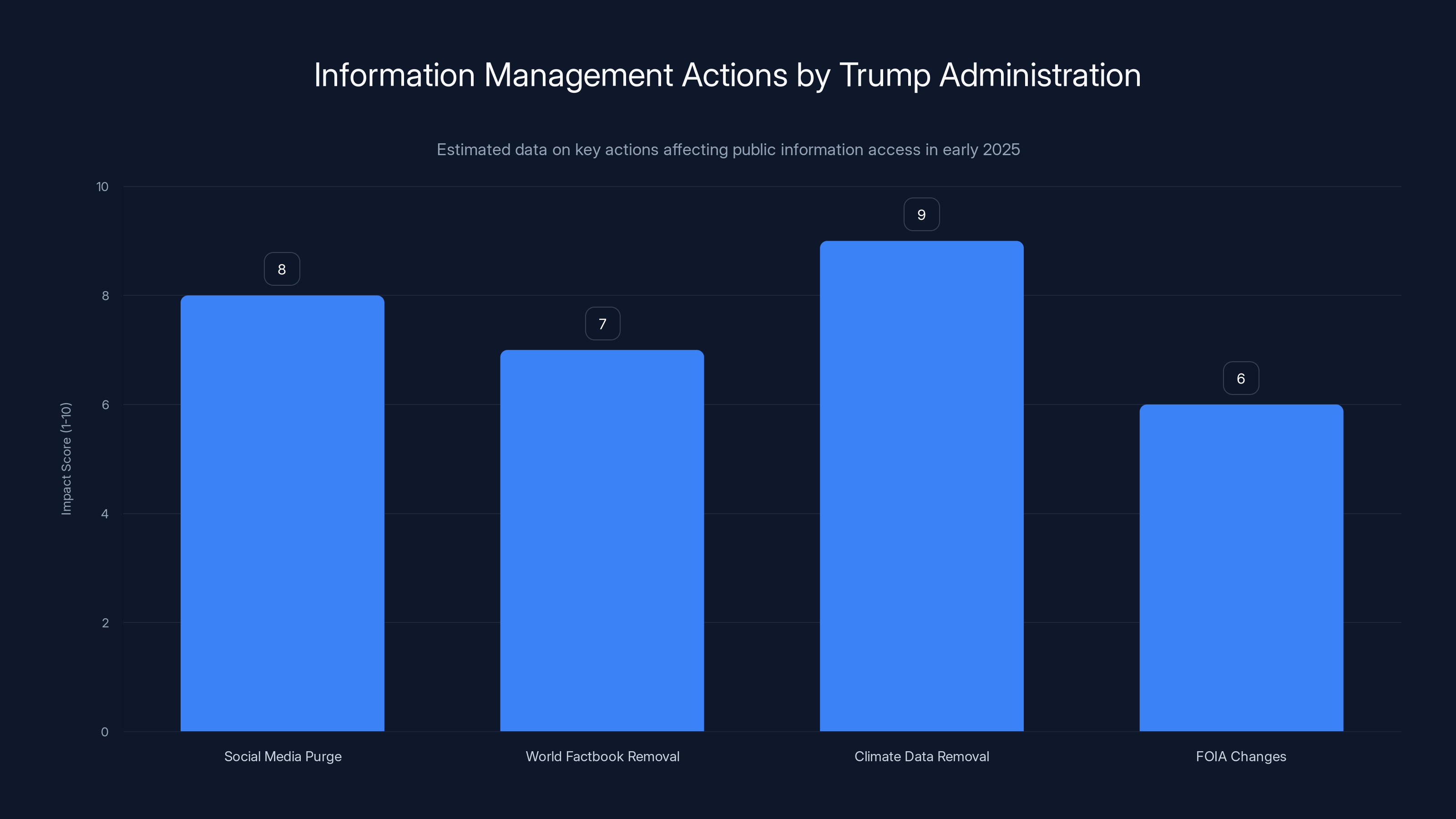

The State Department social media purge doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a documented pattern of information management decisions made by the Trump administration in its early weeks and months of 2025.

Just one week before the State Department confirmed its social media deletion plan, the CIA took down its World Factbook, a global reference guide that has been freely available online since 1997. The World Factbook is not classified material. It contains the kind of basic information you might find in an encyclopedia: demographics, geography, government structure, economy, and transportation networks for every country on Earth. Thousands of schools, researchers, and international organizations rely on it. Yet the CIA, without warning, removed it from public access.

Beyond those specific actions, there have been other moves signaling a broader approach to government information: pardons announced via social media before official channels, sudden changes to agency websites removing climate science content, NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) purging climate data and information pages, and changes to how federal agencies handle Freedom of Information Act requests.

What connects these actions is a philosophy about information control. The rationale offered by administration officials is consistent: reducing confusion, preventing outdated information from contradicting current policy, and ensuring "one voice" in government messaging. From a communications standpoint, there's a logic to this. You don't want different agencies saying different things or offering contradictory information.

But from a transparency and accountability standpoint, this approach treats public records like marketing materials that can be updated or removed when the brand needs a refresh. The assumption seems to be that government information exists primarily to explain current policy, not to provide a historical record of how government officials actually communicated or what previous administrations said and did.

What's particularly striking about the State Department move is the timing. We're not talking about minor housekeeping that happens during every transition. We're talking about a deliberate, comprehensive purge that affects decades of diplomatic communications. And the mechanism—requiring FOIA requests to access what was previously public—essentially converts government records from push (publicly available) to pull (citizens must request them). It's a subtle but significant shift in how government information is treated.

The average FOIA response time for the State Department is over 100 days for simple requests and exceeds 300 days for complex requests, highlighting significant delays.

Historical Precedent: How Previous Administrations Handled Social Media Transitions

To understand how unusual this move is, we need to look at what happened during previous presidential transitions, specifically the Obama-to-Trump and Trump-to-Biden transitions.

When the Obama administration ended in January 2017 and Trump took over, social media accounts transitioned to new management. The White House Twitter account (@WhiteHouse), the presidential account (@POTUS), and various agency accounts all transferred to the new administration. But here's what happened to the old content: it was preserved.

Obama-era tweets remained accessible through the Wayback Machine and other digital archives. The National Archives took steps to preserve official social media records as historical documents. The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) established guidelines for how federal agencies should archive their social media accounts, recognizing that tweets and posts were official government records that should be preserved for posterity.

When Trump's first term ended in January 2021 and Biden took over, the same general pattern held. Trump-era tweets remained publicly visible in the archives. There was no systematic purge of previous content. The expectation was that these records would remain part of the historical record.

The Biden administration continued this approach, neither deleting Trump-era posts from accounts it inherited nor aggressively archiving everything. The general understanding across administrations was that social media posts, once made public, became part of the government record and should remain accessible, especially through digital preservation efforts.

So what changed? Several possibilities: First, the State Department might be taking a more aggressive interpretation of "account ownership" and "messaging control" than previous administrations did. Second, there's been a deliberate decision to treat social media not as historical records but as propaganda channels that should only reflect current messaging. Third, there might be legal or compliance reasons we're not aware of, though the public rationale doesn't suggest this.

What's notable is that the National Archives hasn't publicly objected to this move, which is itself interesting. NARA is technically the government office responsible for preserving official records. Their silence might indicate they're still formulating a response, or it might suggest that the legal authority of agencies to delete their own social media content is murkier than it should be.

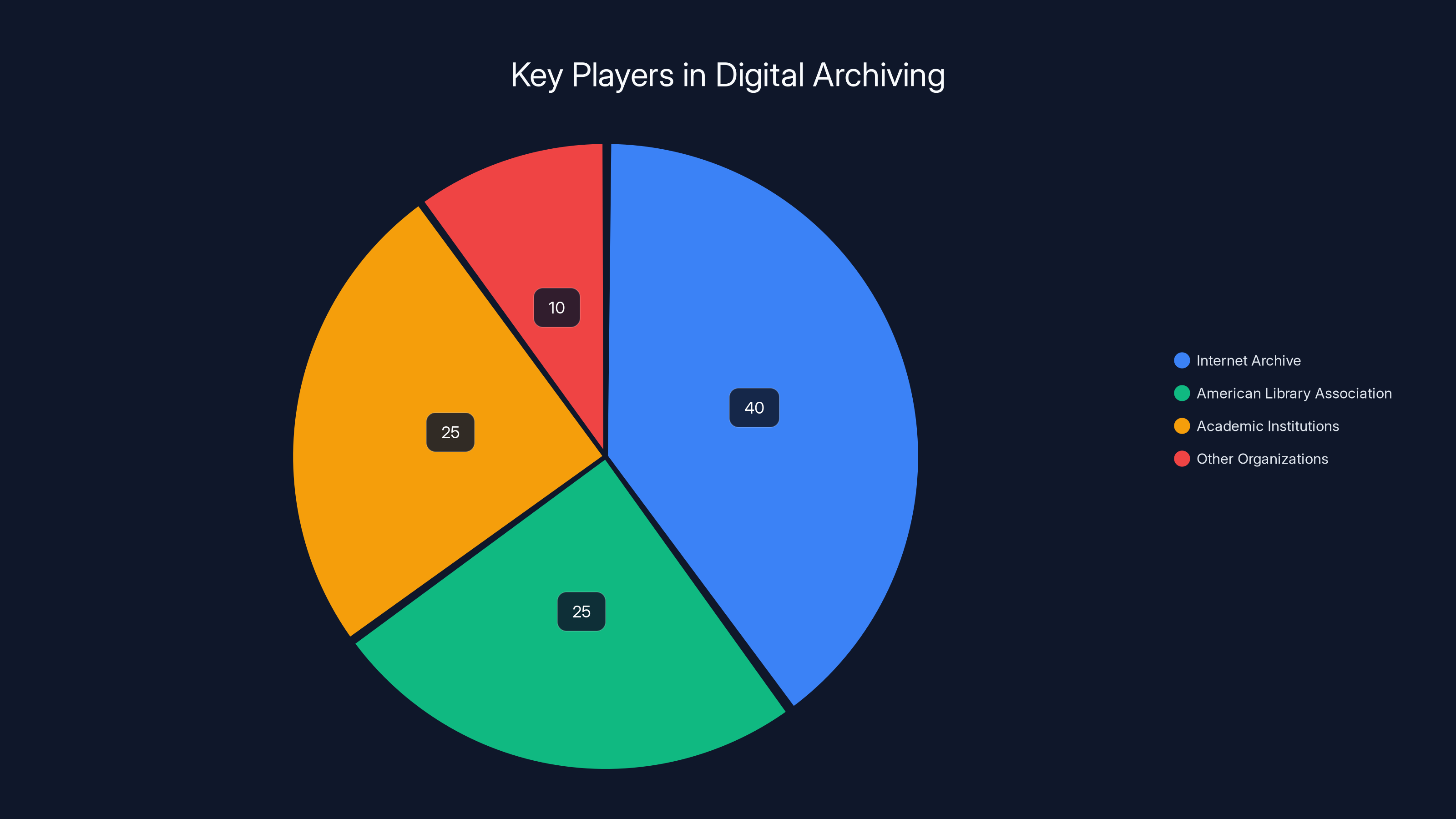

The Role of Digital Archivists: Who's Trying to Preserve This Content?

While government officials debate whether old tweets should be deleted, digital archivists are working frantically to preserve them. These are researchers, librarians, and preservation specialists who understand that once content is deleted and not properly archived, it's gone for good. Digital deletion isn't like losing a paper file that might be recovered in a basement. It's permanent.

Organizations like the Internet Archive, the American Library Association, and academic institutions' special collections are racing to capture government social media content before it disappears. The Internet Archive's Wayback Machine contains snapshots of millions of government web pages and social media accounts, but these snapshots are only as current as the most recent crawl. If a page is deleted before the next crawl is scheduled, that content might not be preserved.

Some universities have established dedicated projects to archive government digital records. The University of Pennsylvania's special collections, for example, have been involved in preserving government records. These efforts are important because they recognize that historical research depends on access to primary source documents, and if the government deletes its own digital records, researchers lose crucial context.

One of the challenges archivists face is that X (Twitter) doesn't make it easy to download bulk archives of accounts. Unlike platforms that provide data export tools, X requires separate requests or technical workarounds. The company changed its policies around data access several times under different ownership, making comprehensive archiving increasingly difficult.

What's particularly concerning from an archival perspective is that the State Department's move suggests a philosophical shift: the idea that agencies can control historical narratives by controlling what records remain accessible. It essentially treats digital records like a PR department treats old press releases—something to be cleaned up and refreshed rather than preserved as evidence of what actually happened.

Digital preservation experts are raising alarms about this, noting that if government agencies begin routinely deleting social media without proper archiving, we could lose vast amounts of the historical record. Consider that social media is increasingly where official announcements happen first. If those posts disappear, historians and researchers lose the actual words used by government officials at crucial moments.

Estimated data suggests significant impact on public information access due to these actions, with climate data removal having the highest impact.

The Legal Framework: What Laws Actually Govern Government Social Media?

One of the most interesting questions underlying this whole situation is surprisingly basic: what laws actually govern what the State Department can and cannot do with its social media accounts? The answer is... complicated and somewhat unclear.

Government records are theoretically protected by federal law, particularly the Presidential Records Act (PRA) and the Federal Records Act (FRA). The Presidential Records Act applies to records created by the president and presidential staff. The Federal Records Act applies to records of other federal agencies. Social media posts created by government officials using government accounts should, theoretically, fall under these acts.

The FRA specifically requires federal agencies to "make and preserve records containing adequate and proper documentation of the organization, functions, policies, decisions, procedures, and essential transactions of the agency." That language seems to clearly include official social media posts. Yet there's ambiguity in how different agencies interpret these requirements.

The White House issued guidance in 2016 suggesting that agency social media accounts should be treated as official records and preserved accordingly. But "guidance" is not the same as law with teeth. There's no criminal penalty for violating these guidelines. There's no agency inspector general empowered to shut down an agency that decides to delete its records.

What happens when an agency violates the FRA? Theoretically, someone could challenge it through litigation, but that's expensive and time-consuming. The FOIA process itself doesn't prevent agencies from deleting records; it just requires them to release them if citizens request them. But if they're already deleted, there's nothing to release.

This is a gap in federal law. We have requirements that records be preserved, but very limited enforcement mechanisms. And we have FOIA as a tool to access records, but it doesn't prevent their deletion. The combination creates a scenario where an agency can essentially delete whatever it wants, knowing that: (1) few people will challenge it, (2) the legal mechanisms to enforce records preservation are weak, and (3) while FOIA technically provides access to deleted records, in practice that's nearly impossible if the records were never properly archived before deletion.

Some legal scholars have argued that the National Archives should have more authority to prevent agencies from deleting records, but current law doesn't grant NARA that power. NARA can set guidelines and standards, but it can't compel an agency to maintain particular records.

Impact on Diplomacy and International Relations

Beyond the abstract principles of transparency and historical record-keeping, there are actual real-world implications for how the U.S. conducts diplomacy when it deletes its public communications.

Embassies use X to communicate with foreign publics, media, other governments, and diaspora communities. These posts are often coordinated with official policy statements and help shape international understanding of U.S. positions. When an embassy in a particular country posts about a trade agreement, sanctions policy, or diplomatic initiative, foreign governments and local media pay attention. These posts become part of the official record of what the U.S. government said it was doing and why.

Now imagine a researcher, journalist, or foreign government official trying to understand U.S. policy during a particular period. They want to know exactly how the State Department was publicly framing an issue, what language they used, what they emphasized or downplayed. If they can't access the actual posts, only a summarized government summary of what was posted, they get a filtered version of history. They get what the current administration wants them to know was said, not what was actually said.

This matters for accountability. Diplomacy depends on trust and consistency. When governments make public commitments on social media, those become part of the diplomatic record. If those commitments can be erased, it creates a precedent that communications can be revised retroactively. Foreign governments noting this might become more cautious about relying on U.S. public statements, knowing they might be deleted later.

There's also an issue of coordination. The State Department doesn't operate in isolation. Its communications are coordinated with the Defense Department, intelligence agencies, and the White House. When one part of government deletes its communications, it complicates the ability of other parts to understand what the unified message was supposed to be. It also makes it harder for researchers studying government decision-making to piece together what informed particular choices.

For American citizens abroad, for diaspora communities following events in their countries of origin, for journalists in authoritarian countries trying to understand U.S. policy toward their region, these Twitter accounts are sometimes the most direct source of information about what the U.S. government is actually saying. When those posts disappear, that communication channel gets shadowed.

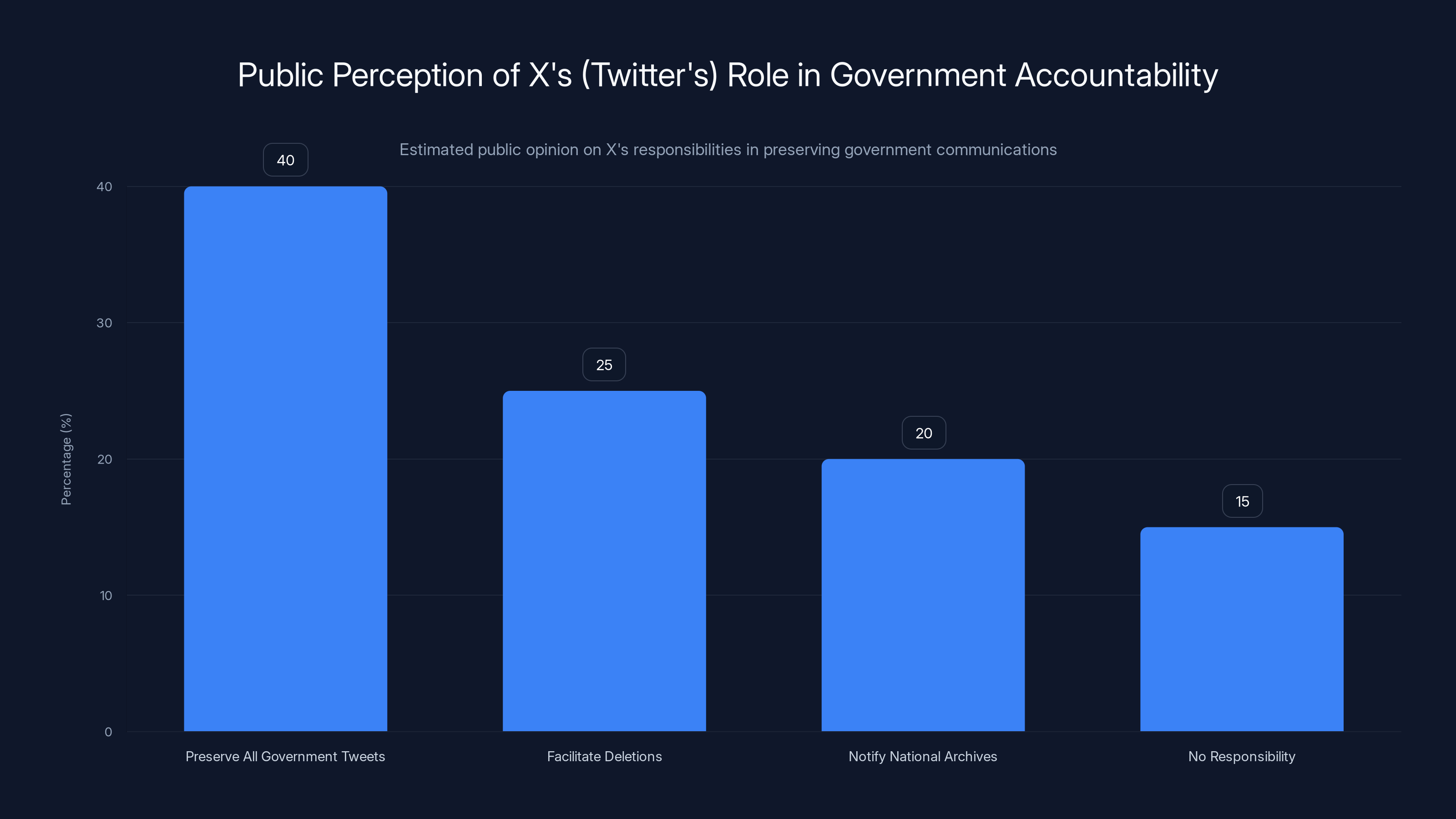

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of the public believes X should preserve all government tweets, while others see no responsibility for the platform. Estimated data.

The Role of X (Twitter) Itself: Platform Policies and Government Accountability

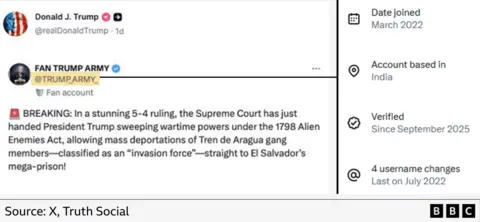

One aspect of this story that doesn't get enough attention is the role of X itself. The platform hasn't publicly objected to or acknowledged the State Department's deletion plan. But there's an interesting question here about what X's responsibilities are, if any, to preserve government communications.

X's official policy is that it preserves tweets unless and until account holders delete them. The company has long positioned itself as a platform for public discourse and has, at various points, claimed that it's in the business of preserving the public record. During the Trump-era debates about whether to ban political figures from the platform, one of the arguments made by free speech advocates was that Twitter (as it was then called) had a responsibility to preserve communications because they had become part of public discourse and historical record.

But in practice, X is a private company, and it has no legal obligation to prevent users from deleting their own content. If the State Department wants to delete its tweets, X will facilitate that deletion. The platform isn't going to step in and say, "Wait, these are government records; you need to file with the National Archives first."

There's an argument to be made that X should provide additional safeguards or notifications when government accounts delete large batches of content. The company could, for example, automatically archive government account deletions or notify the National Archives when official government accounts experience bulk deletions. Some platforms have considered similar features for content moderation and data preservation purposes.

But absent regulation requiring it, X has no incentive to add these safeguards. The company is dealing with its own transition under new ownership and management, and getting involved in government records preservation disputes probably isn't on the priority list.

This highlights a broader challenge: platforms like X are where government now conducts significant public communication, but neither the platforms nor the government has fully figured out how to treat these communications as historical records that need preservation. We have guidelines written for traditional government websites, but not clear protocols for social media archives maintained on private platforms.

There's been some discussion in policy circles about whether the government should maintain its own archives of official social media content, separate from the platforms themselves. This would mean the State Department backing up its own tweets to a government server daily. It's not technically difficult, but it requires institutional commitment and funding. The Trump administration's apparent move in the opposite direction—away from preservation—suggests this isn't a priority right now.

Public Access and Democratic Accountability

At its core, this issue is about democratic accountability. Democracy depends on citizens having access to what their government is doing and saying. That includes the communications government officials make publicly.

When the government deletes public communications and makes them inaccessible without filing formal requests, it changes the balance of power between government and citizens. Governments have always had an informational advantage over their constituents. They know their own internal reasoning, their deliberations, their policy options. But democracy partially compensates for this imbalance by ensuring that what governments say publicly remains accessible and part of the public record.

Once a government official makes a statement on Twitter, that statement becomes part of the permanent record. It's evidence of what was said, when it was said, and how the government was framing particular issues. A citizen, journalist, or researcher should be able to point to that statement and say, "Look, in January 2024, the State Department publicly said X. Now, in February 2025, they're saying Y. Why the change?" That kind of accountability is only possible if the original statement remains accessible.

When statements are deleted and only accessible through FOIA requests, that accountability mechanism gets weakened. Most citizens don't know how to file FOIA requests, don't have the time or resources to pursue them, or don't even know what to ask for. The government effectively screens its own public discourse, deciding what to preserve and what to delete.

There's also a chilling effect to consider. When government agencies know that their statements might be deleted and made inaccessible, does that change how they communicate? Might agencies become more cautious about making commitments publicly, knowing they can be "cleaned up" later? This could actually reduce transparency and public communication as agencies retreat toward carefully lawyered official statements that are less direct and clear.

Public service broadcasting, government transparency laws, sunshine laws, and freedom of information acts all rest on a basic principle: that government accountability requires public access to government communications. The social media deletion contradicts that principle.

Estimated data shows that the Internet Archive leads in digital archiving efforts, followed closely by academic institutions and the American Library Association. Estimated data.

How Citizens Can Respond: Practical Steps and Long-Term Solutions

If you're concerned about government information access and digital preservation, there are actually several things individuals and organizations can do.

First, the individual level. Document and preserve government social media content you find important. Use screenshots, the Wayback Machine's "Save Page Now" feature, or download tools to create personal archives of important posts. This isn't a complete solution, but it creates redundant preservation outside government channels.

Second, consider filing FOIA requests for important records before they're deleted. If you know about government statements you want to preserve access to, request them from the relevant agency now. Get them in writing through official channels. This creates a documented request and potentially preserves records.

Third, support digital preservation organizations. The Internet Archive, university special collections, and digital preservation nonprofits rely on funding and volunteer support. Contributing to these organizations helps ensure that they have resources to archive government content.

Fourth, engage with this as a policy matter. Contact your congressional representatives and express concern about government records deletion. Point out that FOIA requests aren't a substitute for public preservation of records. Advocate for updated records management laws that specifically address digital government communications.

Longer-term, there are structural solutions that could address this: laws requiring government agencies to maintain public archives of official social media accounts; rules mandating that agencies notify the National Archives before deleting official records; requirements that platforms like X preserve government account content; or establishment of mandatory digital archiving standards that apply across agencies.

Some of these solutions would require congressional action. Some could be implemented through executive order or agency policy. The point is that the current situation—where agencies can delete their communications and citizens can theoretically FOIA them later—is a gap that should be closed.

International Precedent: How Other Democracies Handle Government Records

The United States isn't the only democracy grappling with how to preserve government digital communications. It's worth looking at how other countries have approached this problem.

The United Kingdom's National Archives, for example, has been more proactive about establishing standards for government digital records. When UK government agencies go digital with official communications, the National Archives sets requirements for how those records must be preserved and archived. The approach treats digital records with the same legal obligations as paper records.

Canada's Library and Archives Canada has also been ahead of the curve, establishing explicit policies for archiving government social media and digital communications. Canadian agencies are required to transfer records to the national archives according to established timelines, and digital materials aren't exempt from these requirements.

Australia's National Archives has taken a slightly different approach, focusing on helping agencies develop sustainable digital record-keeping systems rather than just capturing outputs. The reasoning is that the best way to preserve digital records is to have proper systems in place from the start, rather than trying to salvage them after the fact.

The European Union's approach emphasizes that social media records created by official EU accounts are considered official documents and must be preserved according to document management regulations. There's less flexibility for agencies to determine what gets kept versus deleted.

None of these approaches are perfect, and all democracies are still figuring out the best way to handle digital preservation at scale. But what they share is a recognition that digital records require intentional preservation efforts and that the default shouldn't be deletion just because deleting something is technically easy.

The U.S. approach, by contrast, seems to be: we'll delete stuff, and if anyone really needs it, they can file a FOIA request. It's less sophisticated than international best practices and reflects a weaker commitment to records preservation.

What This Means for Historical Research

Fast-forward to 2035 or 2045. Historians will be writing books about the 2020s—a period of significant political change, technological disruption, and global challenges. When they want to understand what the U.S. government was saying during this period, where will they look?

Ideally, they'd have access to official archives of government communications, including social media. They'd be able to review what State Department accounts said about particular policies, how messaging evolved, what emphasis the government placed on different issues. This kind of primary source material is gold for historians trying to understand the actual history of a period, not just the official narrative written afterward.

But if those communications have been deleted and aren't properly archived, historians will have to rely on secondary sources: news articles about what the government said, or government summaries written later about what was communicated. That's like trying to understand Shakespeare by reading Wikipedia summaries rather than the actual plays.

The deletion of social media content matters for understanding recent history. These tweets and posts are primary sources, evidence of what actually happened and what government officials actually said, not reconstructed versions written years later. Losing them impoverishes the historical record.

There's also an irony here: the Trump administration is famous for criticizing "fake news" and mainstream media bias. Yet by deleting government communications that journalists and researchers relied on to fact-check claims, they're actually removing some of the primary sources that would allow others to verify what was said. It's a strange approach if the goal is to ensure accurate historical record.

Academic institutions, journalists, and researchers are all noting the implications of this. If government agencies can unilaterally delete their communications, it weakens the foundation that accountability journalism and historical scholarship depend on.

Connecting the Dots: Information Control and Authoritarian Patterns

Looking at the State Department deletion, the CIA World Factbook removal, the climate science purges, and other information management decisions, it's worth asking: what does this pattern suggest about the administration's approach to government information?

There's a consistent theme: controlling the narrative. Deleting information that contradicts current policy messaging, making it harder for citizens to access government records, removing reference materials, shifting from push (public) to pull (FOIA request) information systems.

Now, let's be clear: this doesn't make the U.S. an authoritarian state. The U.S. still has FOIA, courts that sometimes compel disclosure, a free press, and mechanisms for accountability. But these actions move in a direction that mirrors techniques used in authoritarian regimes: controlling official narratives, limiting access to information, deleting inconvenient records.

Historians studying authoritarian governments note that one of the first things they typically do is try to control information access. Not necessarily by declaring censorship, but by controlling what information is available, in what format, and through what channels. Making something technically accessible (via FOIA) but practically inaccessible (requiring months of bureaucratic process) achieves similar effects.

There's a spectrum here. The U.S. is not remotely at the authoritarian end. But the direction of movement matters. If each administration gradually shifts government information systems further away from public transparency and toward more restricted access, that's a concerning trajectory, even if no single move is catastrophic.

Some government efficiency advocates argue that social media archives are frivolous, that government shouldn't spend resources maintaining old tweets, that moving to a FOIA-based access system is fine. But this misses the point. The question isn't whether archiving is expensive (it's actually cheap; cloud storage is pennies). The question is whether government information should default to being public and archived or public and deletable at will.

The Role of Congress: Potential Legislative Responses

One of the most interesting questions is whether Congress will respond to this or let it slide. Theoretically, Congress has authority over records management policies and could pass legislation requiring different treatment of government digital records.

Some members of Congress have been vocal about transparency issues in other contexts. The push for government data transparency in tech regulation, the bipartisan concern about government surveillance, the debates about access to government AI systems—these show that Congress does, at least sometimes, care about government information access.

But the social media deletion issue might not be high enough on the priority list to generate legislative action. It's abstract compared to issues like inflation or the border. It affects researchers and archivists more than average voters. The optics of "Congress wants to force the State Department to keep old tweets" might sound silly to people not following the underlying issue.

Still, there are paths for congressional action: amendment to the Federal Records Act clarifying that social media posts are official records that must be preserved; requirement that agencies notify the National Archives before deleting official communications; mandate that digital archiving standards be established across government; funding for the National Archives to enforce records preservation requirements more aggressively.

None of these are particularly controversial from a governmental efficiency standpoint. They're not partisan issues; both parties benefit from having government records preserved for historical research. But they do require congressional attention and effort, which is in short supply.

The wildcard is whether this becomes a higher-profile issue. If major news organizations start running stories about lost government historical records, if academic institutions raise concerns about research access, if there's grassroots pressure on this issue, Congress might respond. But absent that kind of pressure, it might be treated as a routine government administrative matter.

Practical Implications for Researchers and Journalists

If you're someone who relies on government information for your work—a researcher studying recent history, a journalist covering government policy, a student writing about recent events—the social media deletion has real implications for how you do your job.

First, it changes what primary sources are available to you. You can't quote a State Department tweet that's been deleted unless you archived it previously. You have to rely on secondary sources that quote or reference the original post, which introduces another layer of interpretation between you and the primary source.

Second, it makes your research more time-consuming. Before, you could go back and check what a government official said about an issue by reviewing their public statements. Now, you might have to file FOIA requests to access that information, turning a 10-minute task into a multi-month project.

Third, it changes what stories are possible. Historical accountability journalism depends on being able to point to what government said and compare it to what they're saying now. If the old statements are deleted, that form of accountability becomes harder.

Practically, journalists and researchers are developing workarounds. Some news organizations are setting up dedicated teams to archive government social media in real-time. Academic libraries are investing in digital preservation. But these are improvised solutions to what should be a government responsibility.

For students and researchers just starting out, this creates a particular challenge. They're trying to study recent history without access to primary sources that should be publicly available. They're learning that government information access is more complicated than "it's all on the internet."

Looking Ahead: The Future of Government Digital Records

Where does this go from here? Several possible futures suggest themselves.

One possibility is that this becomes a normal practice. If the State Department deletion passes without significant pushback, other agencies might follow suit. The CIA already deleted the World Factbook. Other agencies could start systematically purging old social media and digital content. Within a few years, the idea that government social media posts remain permanently accessible to the public might become quaint.

Another possibility is that institutional resistance grows. Digital archivists, academic researchers, transparency advocates, and eventually news organizations start pushing back harder. Congressional pressure builds. The National Archives takes a stronger stance on records preservation. New standards get established.

A third possibility is a compromise: government agencies maintain their own archives of deleted content, but don't make them publicly available. Citizens can request archived posts through FOIA, but the posts aren't openly accessible. This technically preserves the information without truly preserving public access.

My guess is a combination: some regulatory pushback will emerge, but it will be partial. There might be new standards requiring archiving, but FOIA will remain the mechanism for access rather than public archiving. The result will be somewhere between full public preservation and complete deletion, probably leaning more toward restricted access.

What's worth noting is that this is still being determined. The decisions being made now about how to handle government digital records will set precedents for years to come. If you care about transparency and public access to government information, this matters.

Conclusion: Democracy Requires Memory

At the deepest level, this story is about what it means to be a democratic society. Democracies depend on transparency, accountability, and institutional memory. Citizens need to be able to know what their government is doing and saying. Researchers need access to the historical record. Future generations need to be able to understand what actually happened during this period.

The State Department's decision to delete its social media without maintaining public archives contradicts these principles, even if that's not the intention. It shifts government information systems from presumptively public to presumptively private, with FOIA as the mechanism to grant access. It removes the ability for citizens to easily check what government officials said at particular moments. It complicates the work of journalists, researchers, and historians trying to understand recent events.

The official rationale—to "speak with one voice" and limit confusion—sounds reasonable on the surface. But it assumes that government messaging is more important than government transparency, that clarity of current messaging matters more than accessibility of historical record.

Democracy has always required that citizens have memory. That they can look back and check what was said, hold government accountable for changes in position, understand the actual history of what happened rather than official narratives written afterward. When that memory becomes difficult to access, when the government effectively controls what can be remembered, something fundamental shifts.

This isn't a catastrophic moment. The FOIA system still exists, courts still enforce transparency rights, and private archivists are working to preserve content. But it's a warning sign about where information systems are heading. Each incremental step away from public transparency, each shift toward pulling records through bureaucratic processes rather than pushing them to the public, each deletion without proper archiving—these moves in aggregate change the relationship between government and citizens.

The stakes might not be immediately obvious because we're talking about old tweets, not secret police or propaganda ministries. But that's exactly how these things work. First, government deletes social media without archiving. Then, government makes accessing deleted records harder. Then, government starts classifying more information. Then, government controls what information is available. And somewhere along that path, you've moved from a system where government transparency is the default to one where government secrecy is.

The State Department's social media purge is a small moment in that larger story. What matters now is whether it becomes a precedent or an anomaly. That depends on whether institutions—Congress, the Archives, the courts, and most importantly, citizens—pushback and insist that democracy requires memory.

FAQ

What specifically is the State Department deleting from its X accounts?

The State Department is removing all posts published before President Trump's second term began in 2025. This includes posts from the Obama administration (2009-2017), the Trump administration's first term (2017-2021), and the Biden administration (2021-2025). The deletion affects the main State Department account as well as dozens of embassy and regional bureau accounts worldwide. According to NPR's reporting, posts from Trump's first term are also being deleted despite being from the same president, which suggests the deletion is about creating a clean break temporally rather than administratively.

How can citizens access deleted State Department posts after the purge?

According to the State Department spokesperson's comments to NPR, the only official mechanism for accessing deleted posts will be through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Citizens would need to file formal requests with the State Department specifying what records they want. This process typically takes weeks to months, requires familiarity with FOIA procedures, and can result in partial or complete denials if information is deemed sensitive. This contrasts sharply with the previous system where posts remained publicly visible indefinitely.

Why is the State Department making this decision?

The State Department provided an official rationale to NPR: to "limit confusion on U.S. government policy and to speak with one voice to advance the President, Secretary, and Administration's goals and messaging." The spokesperson also stated the move would "preserve history while promoting the present." Essentially, the administration is framing this as a necessary cleanup to ensure current messaging isn't contradicted by old posts and to present a unified policy voice.

Is this legal under federal records management law?

The legality is murky. The Federal Records Act theoretically requires federal agencies to preserve official records, including social media posts. However, enforcement mechanisms are weak, and the National Archives lacks clear authority to prevent agencies from deleting their own social media. While FOIA requires agencies to release records if requested, it doesn't prevent them from deleting records first. As a result, there's a significant gap between what records preservation law suggests should happen and what enforcement actually compels.

How does this compare to previous administrations' handling of social media transitions?

When the Obama administration ended in 2017 and Trump took over, government social media posts were preserved and remain accessible through digital archives like the Internet Archive. The same occurred when Trump's first term ended in 2021. The expectation across previous administrations was that social media posts, once made public, became part of the historical record. The current State Department's decision to delete without maintaining public archives represents a significant departure from this practice.

What can researchers and journalists do if they need access to deleted posts?

Immediate action involves using digital preservation tools like the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine to capture important posts before deletion. For posts that have already been deleted, researchers can file FOIA requests, though this is time-consuming and not guaranteed to succeed. Organizations can contribute to or support digital preservation nonprofits that are archiving government content. Longer-term solutions involve advocating for legislative changes that would mandate government preservation of official digital communications.

Could other government agencies follow the State Department's lead and delete their social media?

Yes, this is a significant concern. The CIA already deleted its World Factbook shortly before the State Department announced its social media purge. If these actions are seen as acceptable, other agencies could follow suit with their own social media and digital content deletions. This could create a broader pattern of government information being deleted without public archival, weakening overall government transparency and accessibility of historical records.

What's the difference between deleting posts and making them FOIA-accessible?

The practical difference is substantial. Public posts can be accessed immediately by anyone, used in research, quoted by journalists, and preserved by digital archivists. FOIA-accessible posts require formal requests, bureaucratic processing, potentially months of wait time, and may be partially redacted or denied. This shifts information from a "push" system (government provides it proactively) to a "pull" system (citizens must request it), dramatically reducing how many people actually access the information.

Key Takeaways

- State Department is permanently deleting X posts from before Trump's second term without maintaining public archives, breaking precedent from previous administrations

- Deleted posts can only be accessed through FOIA requests, which take months and may result in redactions or denials, shifting from push to pull access systems

- This deletion represents part of a broader pattern including CIA's World Factbook removal and climate science purges from government websites

- Federal records preservation laws (Federal Records Act) theoretically require preservation of government social media, but enforcement mechanisms are weak

- Digital archivists, researchers, and journalists are racing to preserve content before deletion using Internet Archive and other preservation tools

- Other democracies (UK, Canada, Australia, EU) have more robust digital preservation standards than the current U.S. approach

- Deletion without public archiving weakens historical research, journalistic accountability, and prevents citizens from fact-checking government policy changes

Related Articles

- DOJ Epstein Files Redaction Failure: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- Public Health Workers Resigning Over ICE & Guantánamo Assignments [2025]

- Elon Musk's $150M SEC Lawsuit: Why Trump Won't Back Him [2025]

- How DHS Uses Administrative Subpoenas to Target Critics [2025]

- US Offshore Wind Court Orders: Construction Restart [2025]

- How Government AI Tools Are Screening Grants for DEI and Gender Ideology [2025]

![State Department Deletes X Posts Before Trump's Term: What It Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/state-department-deletes-x-posts-before-trump-s-term-what-it/image-1-1770500175386.jpg)