Introduction: When a Hobby Project Uncovers a Global Security Nightmare

Imagine buying a shiny new robot vacuum, excited about the convenience of automated cleaning while you're at work. You set it up, pair it with your phone, and go about your day. What you don't know is that somewhere across the internet, a stranger could be watching your home through the vacuum's camera, mapping out your entire house room by room, or even sending it on a joyride through your living room. This isn't a dystopian nightmare—it happened to thousands of DJI Romo owners.

Sammy Azdoufal, an AI strategy lead at a vacation rental company, stumbled onto something terrifying while tinkering with his new robot vacuum. He wanted to control it with a PS5 gamepad, a fun project to experiment with some reverse engineering. But when his homegrown app started communicating with DJI's servers, something unexpected happened. Instead of just his robot responding, roughly 7,000 DJI Romo vacuum cleaners scattered across 24 different countries started treating him like their legitimate owner. He could access their live camera feeds, watch their navigation maps update in real-time, view their battery levels, and most alarmingly, remotely control them without any authentication checks.

What makes this discovery so alarming isn't just the scale of the vulnerability, but how trivially simple it was to exploit. Azdoufal didn't hack into DJI's servers through a complex cyber attack. He didn't brute force passwords or crack encryption. Instead, he simply extracted his own device's private authentication token—the digital key that normally proves you own your specific vacuum—and discovered that DJI's servers would happily hand over data for thousands of other devices using that same token. This was a fundamental failure in how the company designed its security architecture, and it raises serious questions about IoT device security across the entire industry.

In this article, we'll dissect how this vulnerability worked, what it exposed, why it happened, and what it means for the future of smart home device security. We'll explore the technical details that made this exploit possible, the real-world implications for affected users, and what manufacturers need to do differently.

TL; DR

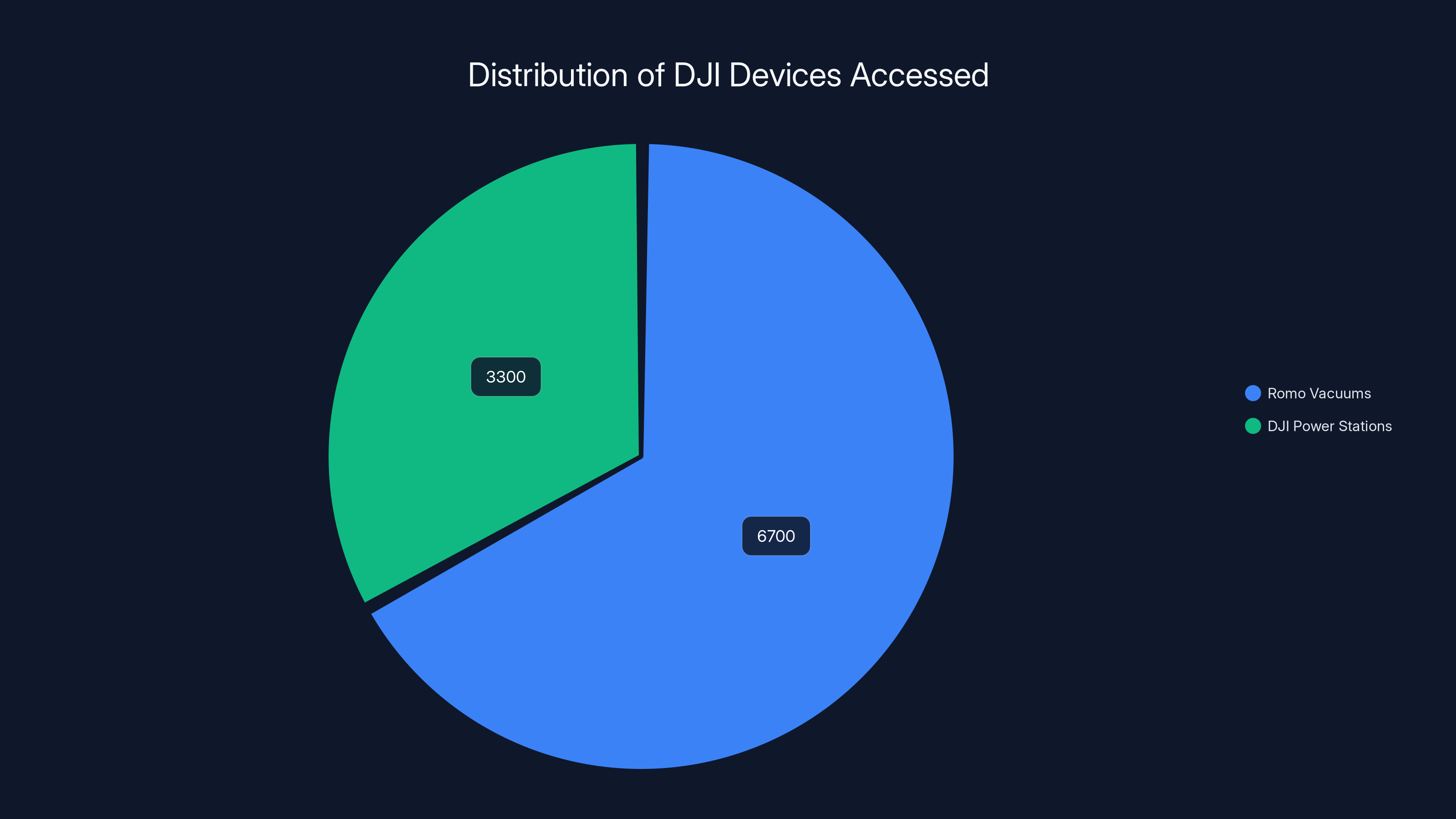

- Scale of the breach: A researcher gained unauthorized access to approximately 7,000 DJI Romo robot vacuums in 24 countries plus over 10,000 DJI Power stations

- What was exposed: Live camera feeds, complete 2D floor plans of homes, real-time location data, and remote control access without authentication

- How it happened: The vulnerability wasn't a complex hack but a fundamental flaw in server-side authorization that gave one device's authentication token access to all devices

- Authentication bypass: DJI's servers accepted the token without verifying the user actually owned the device being accessed

- Status: The immediate threat was patched shortly after disclosure, but the discovery exposes systemic security issues in IoT device design

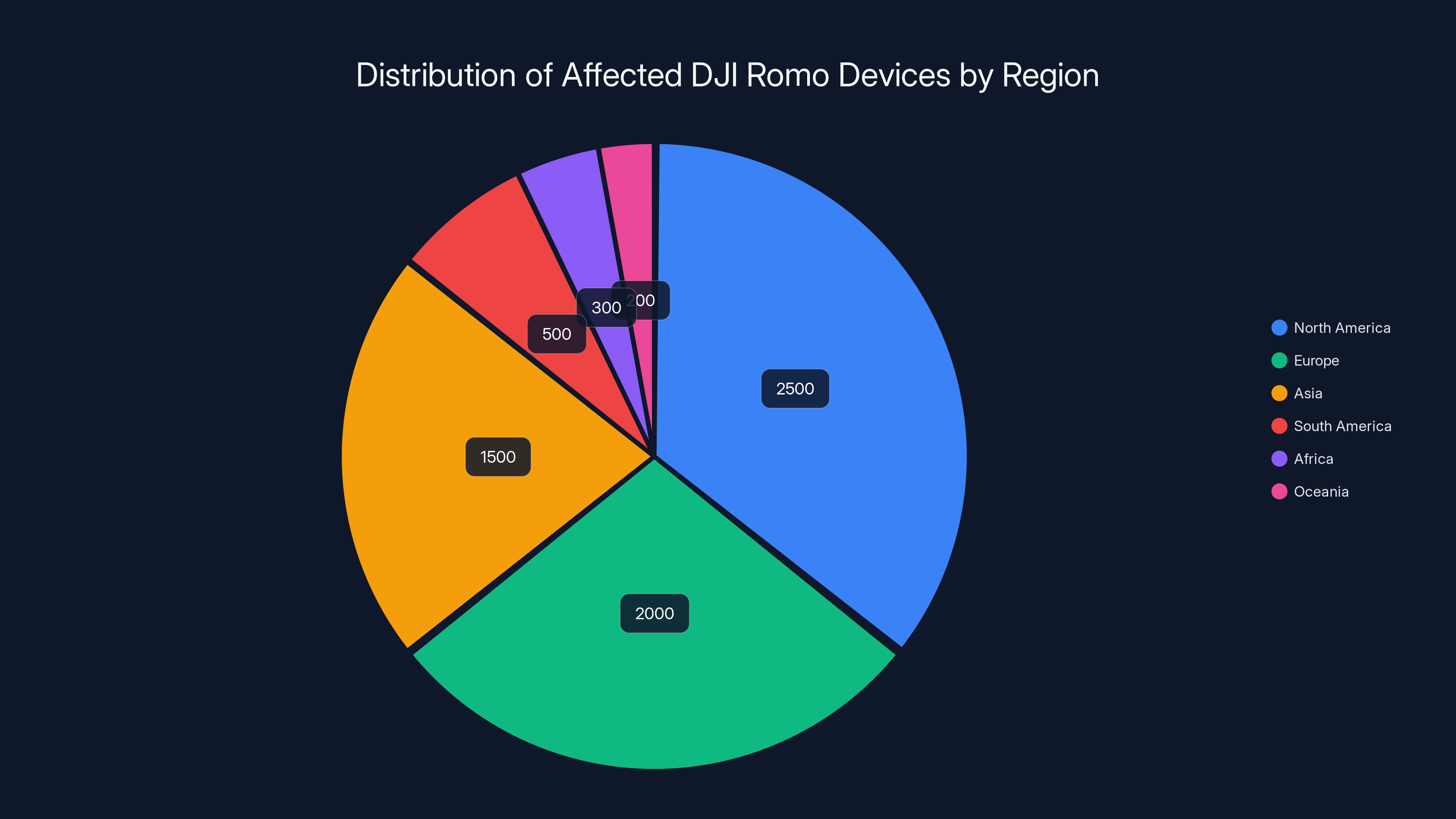

Estimated data shows North America and Europe had the highest number of affected DJI Romo devices, highlighting the global impact of the security vulnerability.

How a PS5 Gamepad Project Turned Into a Global Security Discovery

Sammy Azdoufal's journey into this vulnerability began innocently enough. He'd just purchased a DJI Romo robot vacuum and, like many tech-savvy users, wanted to tinker with it. The idea was simple: build a custom remote control application that would let him operate the vacuum using a PS5 gamepad. It's the kind of fun engineering project that developers tackle in their spare time.

Azdoufal used Claude Code, an AI coding assistant, to help reverse engineer the DJI Romo's communication protocols. He intercepted the network traffic between his vacuum and DJI's cloud servers, documented the message formats, and began understanding how the device communicated. This is a legitimate security research technique, commonly used by hobbyist developers and professional security researchers to understand how devices work.

But here's where things got interesting. When Azdoufal's homegrown application started communicating with DJI's servers using the extracted authentication token from his own device, the servers didn't just respond with his robot's data. They responded with data from thousands of other robots. His laptop began cataloging device after device, receiving MQTT data packets every three seconds from thousands of Romos and DJI Power stations around the world.

In just nine minutes, Azdoufal's system had collected information about 6,700 different DJI devices across 24 countries. He was receiving regular updates showing their serial numbers, which rooms they were cleaning, what obstacles they'd encountered, their battery levels, their cleaning history, and their rough geographic locations. If you combined the Romo vacuums with the DJI Power portable power stations that used the same vulnerable servers, his access extended to over 10,000 devices.

The most disturbing part? He never needed to crack any passwords. He never exploited any software vulnerability. He simply used his own legitimate device's authentication key to query the servers, and they handed over other people's data without asking any questions. It was, in security terms, a catastrophic failure in authorization logic.

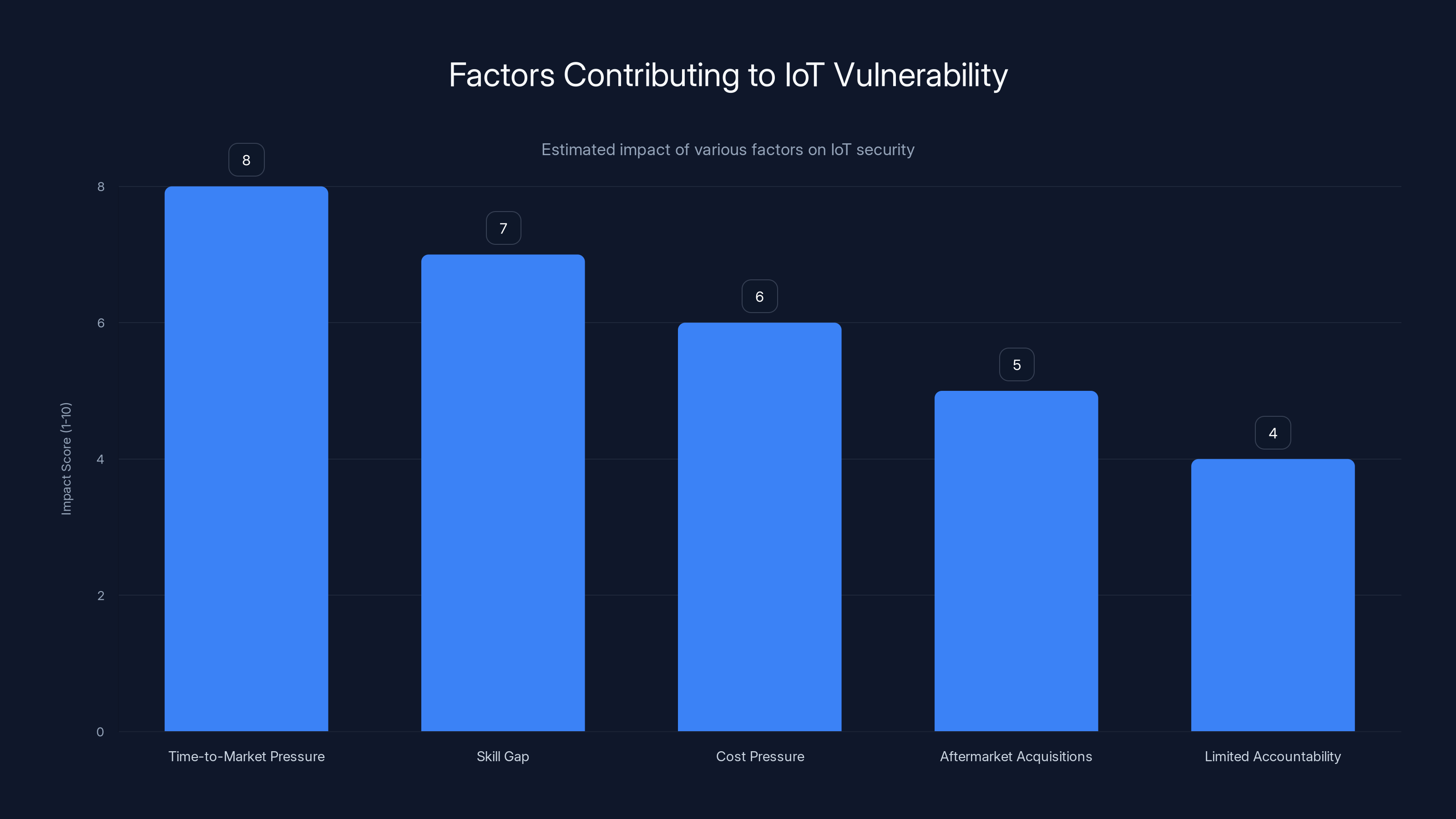

Time-to-market pressure is the most significant factor contributing to IoT device vulnerabilities, followed by skill gaps and cost pressures. (Estimated data)

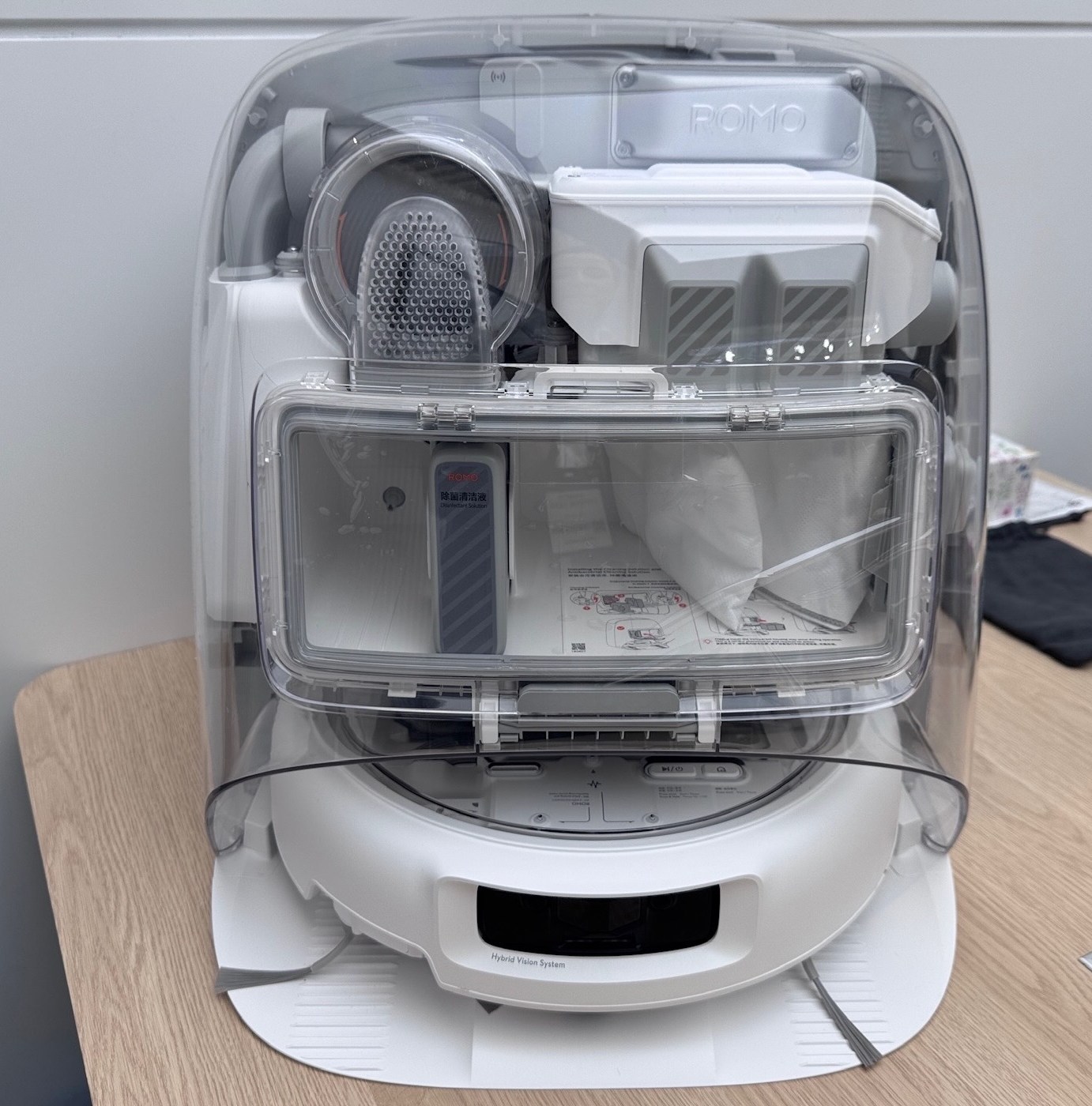

The Technical Architecture: Understanding MQTT and Why It Failed

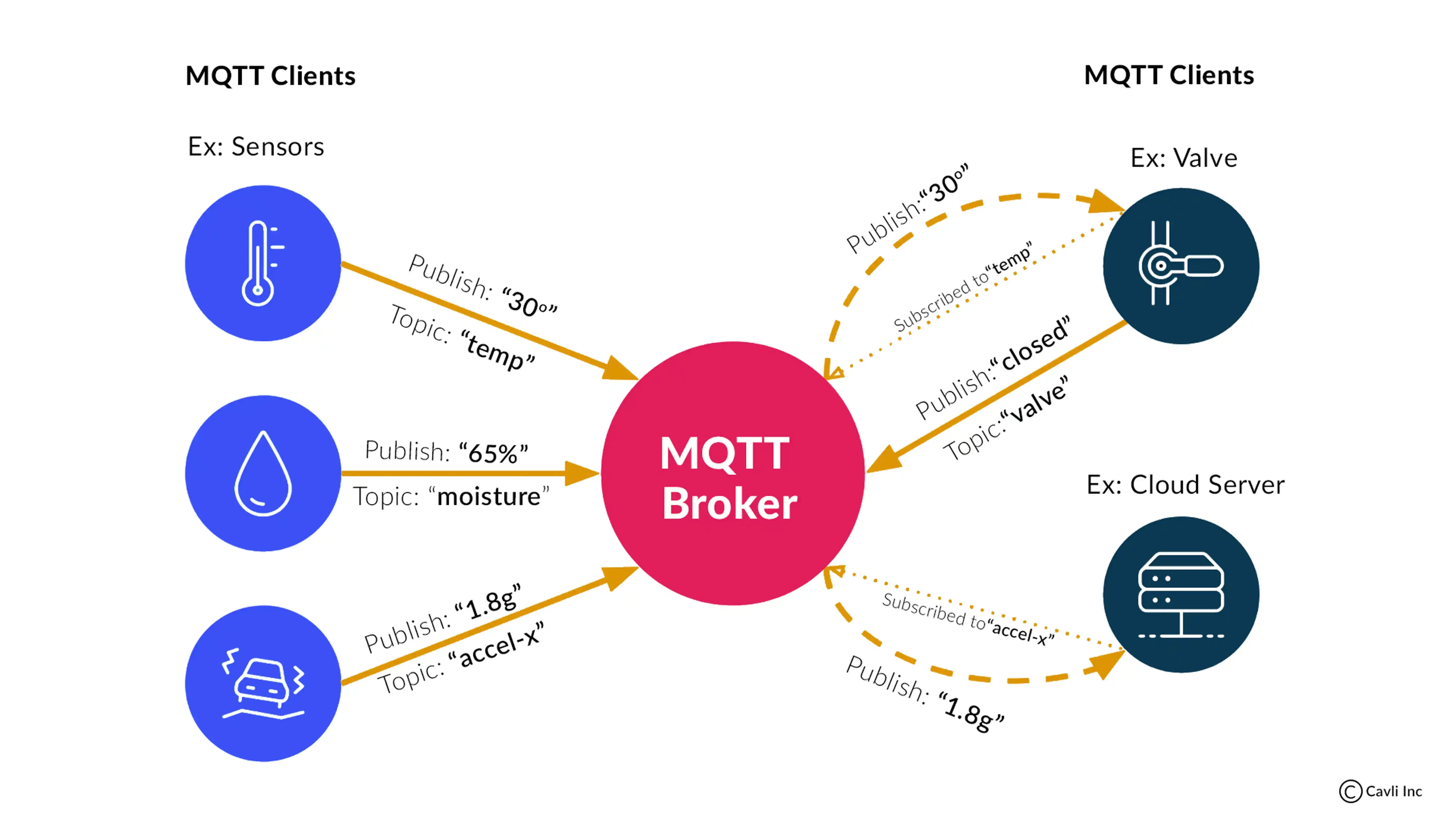

To understand why this vulnerability existed, we need to talk about the technology DJI chose to power their cloud communication: MQTT. MQTT stands for Message Queuing Telemetry Transport, and it's a popular lightweight messaging protocol designed for IoT devices. It's efficient, uses minimal bandwidth, and works well for sending small data packets from thousands of devices simultaneously. Many IoT manufacturers use it for these exact reasons.

Here's how MQTT typically works. A robot vacuum (the client) connects to an MQTT broker (DJI's servers) and identifies itself using credentials. The broker then allows the device to publish messages to specific topics and subscribe to messages on those topics. Think of it like a postal system where each device has a mailbox, and it can only access mail from its own box.

The problem with DJI's implementation wasn't really MQTT itself—it was how DJI chose to handle authorization on top of it. The vulnerability existed in the server-side logic, not in the protocol. Specifically, DJI's servers accepted a valid authentication token from any user and would return data for any robot, regardless of whether that token actually belonged to that robot.

In properly secured architecture, the flow would work like this: User submits a request with their auth token. The server verifies the token is valid. The server checks which devices that user owns. The server only returns data for those specific devices. But DJI's implementation skipped step three entirely. Once a token was validated as authentic, the servers would return whatever data the token holder requested, with no additional ownership verification.

This is a classic authorization bypass vulnerability, often categorized as an Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) in security terminology. It's one of the most common web application vulnerabilities because it's so easy to accidentally implement. Developers focus on making sure users are who they claim to be (authentication) but forget to check whether they're allowed to access what they're asking for (authorization).

What Azdoufal Could Actually See and Control

The scope of what this vulnerability exposed was genuinely alarming. Let's break down exactly what an attacker could access with just an authentication token and a serial number from any DJI Romo device.

Live Camera Feeds Without Authentication: Azdoufal could pull up a device's live video feed without knowing the device's security PIN. This is the feature DJI implemented specifically to prevent unauthorized viewing—the PIN requirement. But the PIN only protected local access. Remote access through the server completely bypassed it. He demonstrated this by pulling up his own Romo's video feed, walking into his living room, and waving at the camera while the researchers watched the video stream in real-time from thousands of miles away.

Complete 2D Floor Maps: The Romo maps each room of your home as it cleans, creating a detailed 2D floor plan. This data is incredibly valuable—not just for navigation but for understanding the layout of someone's home. With this vulnerability, Azdoufal could access floor plans of homes he'd never visited. He demonstrated this by pulling floor maps from test devices, and they showed accurate room shapes, sizes, and placements. For someone with criminal intent, having a detailed floor plan of a home is useful for planning a burglary—they'd know exactly how many rooms there are, the layout, potential security risks, and where valuables might be stored.

Real-Time Cleaning Data: The servers were receiving MQTT packets every three seconds from each device, containing information about what the robot was currently doing. Azdoufal could see which rooms were being cleaned, for how long, when the robot was returning to its dock, and what obstacles it encountered. This creates a pattern of when the home is occupied. If a robot is actively cleaning, someone's likely home. If it's docked and idle, the home might be empty. An attacker could monitor these patterns to understand when a home is vacant.

Remote Control Capabilities: Most concerning, Azdoufal could send commands to any robot. In theory, this meant he could direct a device to go to specific locations or trigger its sensors and features. The immediate threat was partially mitigated by DJI (he couldn't send the robot on a full joyride as claimed), but the fact that remote commands could be injected into devices belonging to other users is a serious threat.

Geographic Location Inference: From the MQTT data, Azdoufal could roughly determine where devices were located by their IP addresses. Combined with floor plan data, this created a picture of where homes were and their layouts.

Access to Pre-Production Servers: Most alarming, Azdoufal could access DJI's pre-production testing servers as well as the live servers for the US, EU, and China. This meant he wasn't just seeing currently sold devices—he might have had access to data from devices still in testing phases.

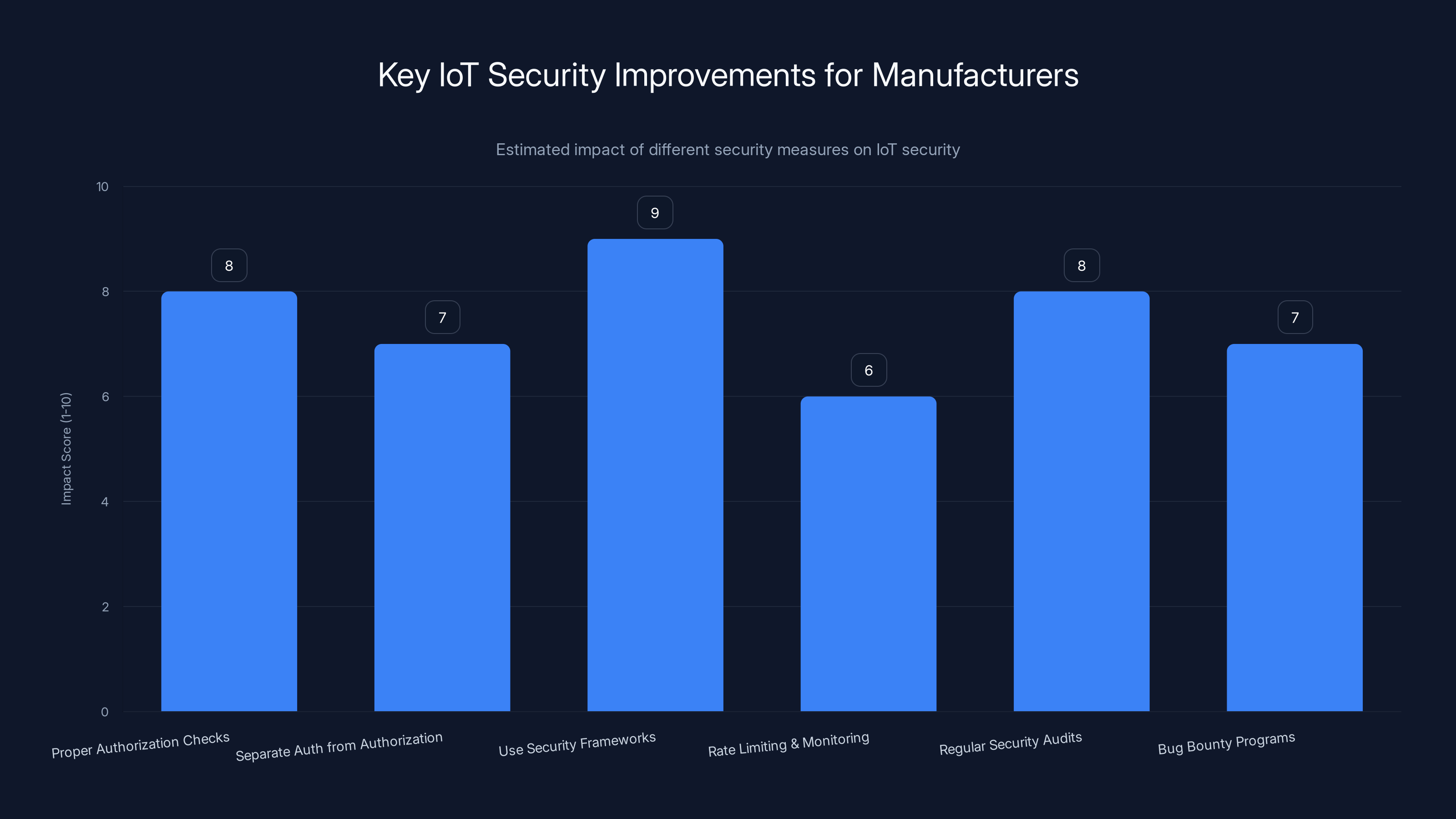

Implementing established security frameworks and conducting regular audits are estimated to have the highest impact on improving IoT security. (Estimated data)

How an Attacker Could Have Exploited This at Scale

Now let's think about how a malicious actor could have weaponized this vulnerability. Azdoufal was a responsible researcher who didn't cause harm and disclosed the vulnerability, but a bad actor would have had different intentions.

Home Invasion Planning: An organized crime ring could have harvested floor plans and location data from thousands of homes. They could identify homes with valuable layouts conducive to burglary, combine this with the occupancy patterns from cleaning schedules, and plan coordinated break-ins. The victims would never suspect that their robot vacuum had provided the reconnaissance.

Targeted Spying: Someone could have watched specific high-value targets' homes through the camera feeds. Celebrities, executives, or other prominent individuals use smart home devices. An attacker who knew the serial number of a target's Romo could watch their living room 24/7 without the victim's knowledge.

Ransomware Distribution: An attacker could have used the remote control capabilities to inject malicious firmware or commands into Romos, potentially using them to compromise home networks. A robot vacuum connected to a home's WiFi could be a vector for accessing other smart home devices on the same network.

Mass Surveillance Infrastructure: An attacker could have continuously harvested data from thousands of homes, building a database of floor plans, occupancy patterns, and locations. This data would have significant value to corporate intelligence operatives, insurance companies, or law enforcement (both legitimate and corrupt).

Botnet Creation: With remote control access, thousands of Romos could theoretically have been conscripted into a botnet, using their computing resources and network connectivity for distributed denial-of-service attacks or other malicious purposes.

The fact that this vulnerability existed for an unknown period before being discovered by Azdoufal means there's a possibility that other researchers—both well-intentioned and malicious—discovered it before him. We have no way of knowing whether anyone had exploited it at scale before the patch was deployed.

Why DJI's Security Architecture Failed So Catastrophically

Understanding why this happened requires looking at the development practices and architectural decisions that led to this vulnerability. Security failures rarely happen in isolation; they're usually the result of multiple compounding issues.

Confused Responsibility Between Authentication and Authorization: The most fundamental issue is that someone on the development team treated authentication (proving you are who you say you are) as sufficient for authorization (you have permission to access this resource). These are two separate concerns. Authentication is necessary but not sufficient—just because a request comes with valid credentials doesn't mean that person should have access to every resource in the system.

Lack of Security Code Review: This vulnerability would have been caught immediately in a peer code review focused on security. Any experienced security engineer reviewing the authorization logic would have asked, "Does the server check that the user making this request actually owns this device?" The fact that this wasn't caught suggests either no security review happened, or it wasn't thorough.

No Principle of Least Privilege: In secure system design, each user should have access to the minimum data and functionality they need to accomplish their task. DJI's implementation gave anyone with a valid token access to everything. A properly designed system would have tightly scoped permissions.

Inadequate Testing of Boundary Conditions: Security testing should include testing what happens when someone tries to access resources they shouldn't have access to. This would be part of standard penetration testing. The fact that this basic vulnerability existed suggests testing focused on happy paths, not security scenarios.

Potential Over-Reliance on Network Obscurity: Some developers think that if the API isn't publicly documented, it's secure by default. This is a fallacy called "security through obscurity." DJI might have assumed that since the API wasn't published, no one would discover it. But reverse engineering protocols is a common practice.

Missing Server-Side Validation: Whenever a client makes a request that includes an identifier (like a robot serial number), the server must validate that the client has permission to access that identifier. DJI failed to perform this validation.

Azdoufal's project inadvertently accessed data from approximately 6,700 Romo vacuums and 3,300 DJI Power Stations, highlighting a significant security oversight. Estimated data.

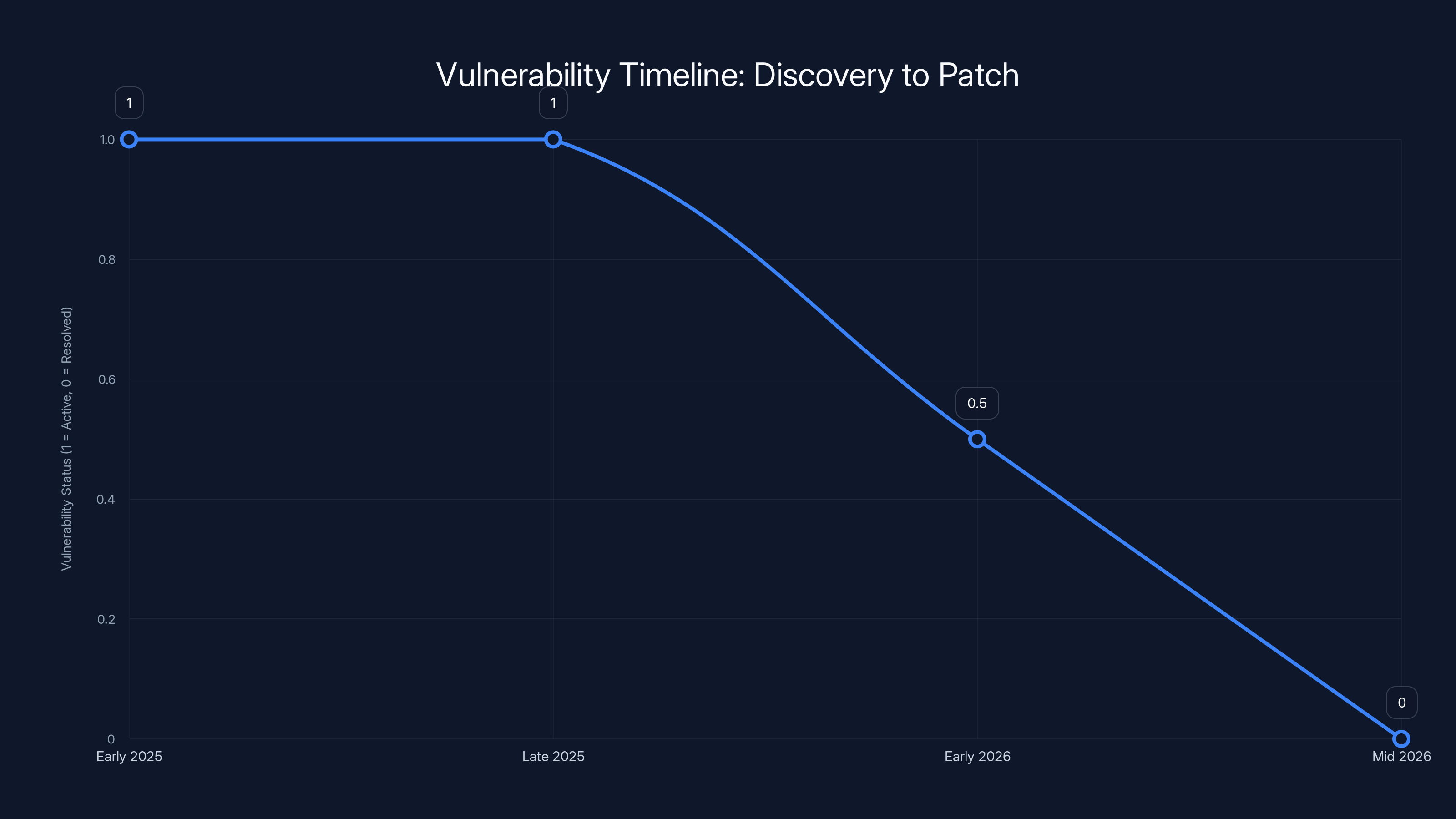

The Vulnerability Timeline: From Discovery to Patch

Understanding when this vulnerability existed and for how long is crucial for assessing the potential damage. The timeline shows how the security community and DJI responded.

Azdoufal discovered the vulnerability sometime in late 2025 (based on the reports). He documented his findings and reached out to DJI to responsibly disclose the issue. This is the correct procedure—security researchers notify the vendor privately before publicizing the vulnerability, giving the company time to develop and deploy a fix.

DJI's response was relatively quick. Upon being notified, they began investigating and developing patches. Within a reasonable timeframe (though the exact duration wasn't fully disclosed), DJI deployed fixes to their servers. The most critical attacks—remote control and some data access—were mitigated relatively quickly.

However, the fixes were partial rather than complete. Some functionality was disabled or limited, but the underlying architectural issue wasn't fully resolved. This is common in emergency patches when you're trying to stop bleeding before fixing the root cause. A proper, comprehensive fix would require redesigning how the authorization system works, which takes longer.

The vulnerability likely existed since the DJI Romo's launch (announced in 2024, released in early 2025). This means potentially thousands of homes had their security compromised for months before this was publicly acknowledged. We don't know exactly when the vulnerability was introduced in the product lifecycle, but it had to exist at least from launch until the patch was deployed.

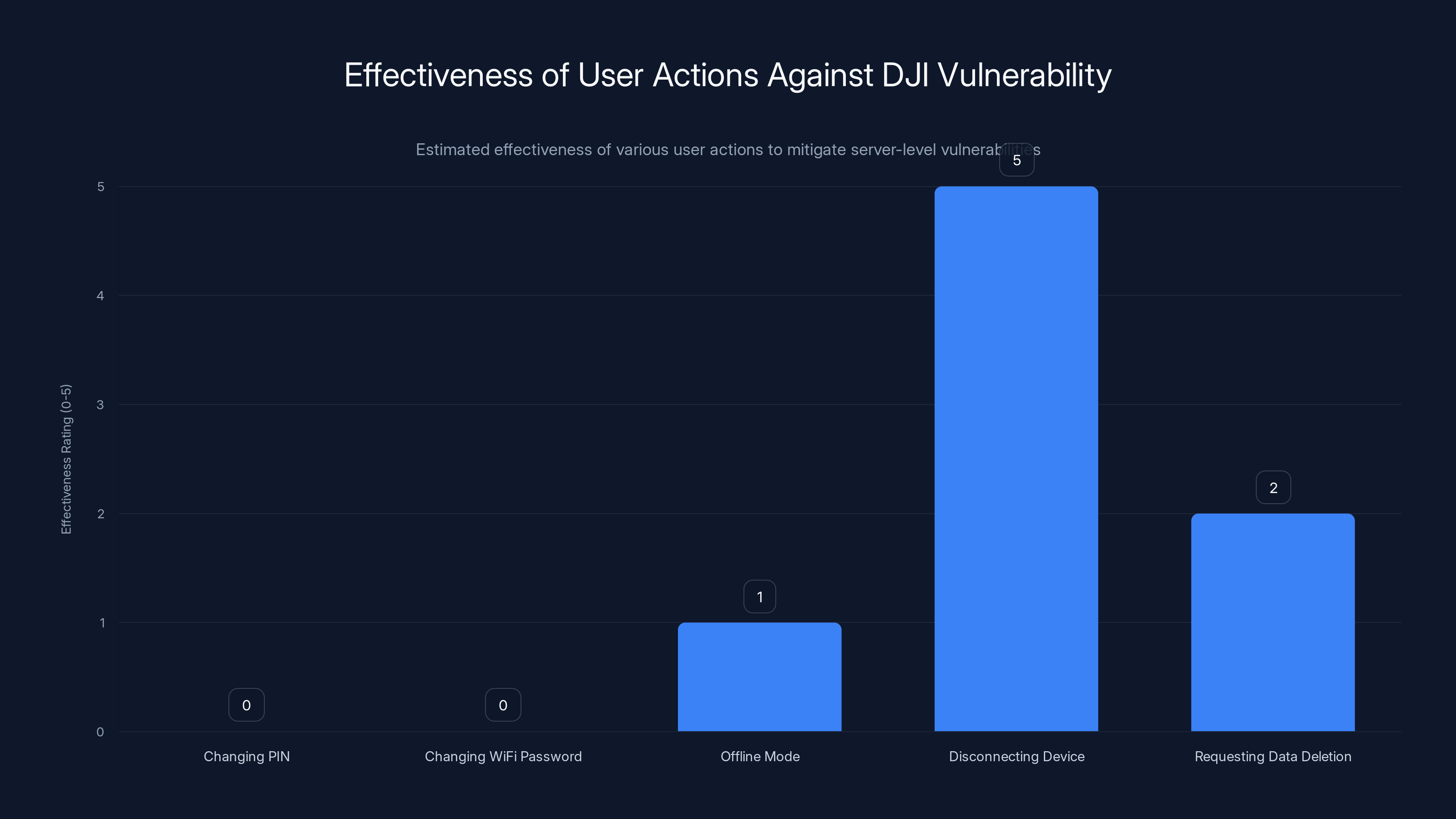

What Users Could Do to Protect Themselves Before the Patch

While DJI worked on deploying patches, affected users had limited options for protecting themselves. This highlights another problem with the vulnerability—there was no practical mitigation that users could implement.

Changing Your PIN: Wouldn't actually help. Since the vulnerability bypassed PIN authentication entirely at the server level, a stronger PIN would have made no difference.

Changing Your WiFi Password: Not helpful for cloud-based attacks. Since the vulnerability was in DJI's servers, not your home network, local network security was irrelevant.

Offline Mode: If your Romo could operate without cloud connectivity, you might think this would protect you. But the vulnerability exposed data already collected and stored on DJI's servers. Disabling cloud features would prevent new data from being sent, but it wouldn't delete historical data or prevent attackers who had already gained access from viewing it.

Disconnecting the Device: The only truly effective mitigation was to simply not use the device. For someone who paid $500-700 for a robot vacuum, this was an unacceptable solution.

Requesting Data Deletion: Users could have theoretically requested that DJI delete their floor plan and historical data, but without knowing the vulnerability existed or what specifically was exposed, most users wouldn't have thought to do this.

This illustrates a critical point about IoT security: when a vulnerability exists at the server level, users have almost no ability to protect themselves. They're entirely dependent on the manufacturer to secure their infrastructure. This creates an asymmetry of power—users can't verify that the system is secure, and they can't mitigate risks if it isn't.

Most user actions were ineffective against the server-level vulnerability, with disconnecting the device being the only somewhat effective measure. (Estimated data)

Industry Context: Why IoT Devices Are Particularly Vulnerable

The DJI Romo vulnerability isn't an anomaly; it's part of a larger pattern of poor security in IoT devices. Understanding the industry context helps explain why this happened and why it might happen again elsewhere.

Time-to-Market Pressure: The smart home device market is incredibly competitive. Companies are racing to get products out before competitors. Security is often treated as an afterthought because it doesn't directly generate revenue in the way features do. A company might skip security reviews to hit a launch deadline, telling themselves they'll "improve security in future versions." It rarely happens.

Skill Gap in IoT Development: Building IoT firmware is specialized work. Many developers working on smart home devices come from embedded systems or hardware backgrounds where security wasn't traditionally a major focus. They might not be trained in secure API design or cloud architecture. A developer who's great at optimizing power consumption might not understand authorization vulnerabilities.

Pressure to Keep Devices Cheap: Smart home devices operate on thin margins. Companies are trying to get the hardware cost down to maximize profit or compete on price. This means they're also trying to minimize software development complexity and costs. Proper security requires more development resources and more rigorous testing.

Aftermarket Acquisitions: Many IoT companies grow through acquisition. A startup with decent security practices might get bought by a larger company that consolidates services onto shared infrastructure. During that consolidation, corner-cutting happens. DJI's servers might have been designed to handle many different device types, and the authorization logic might have been written hastily to support multiple products.

Limited Accountability: Unlike industries with regulatory oversight (automotive, medical devices), consumer IoT has minimal regulation. A car manufacturer faces fines and lawsuits if a vulnerability in their vehicle control system is exploited. An IoT company might face no legal consequences beyond reputational damage if their security is poor and a vulnerability is exploited. This creates fewer incentives for security investment.

Dependency on Third-Party Libraries and Cloud Providers: Many IoT companies rely on third-party libraries and cloud services they don't fully understand or control. If a third-party library has a vulnerability, it might propagate into your product. But the accountability remains with you, the device manufacturer.

Broader Implications: What This Means for Smart Home Security

The DJI Romo vulnerability has implications far beyond DJI's product line. It raises serious questions about smart home security across the entire industry and what consumers should expect.

Trust Assumptions Are Broken: Most consumers assume that when they buy a smart home device from a major manufacturer, the device communicates securely with the company's servers. This DJI vulnerability shows that assumption is dangerous. You can't visually inspect a device's security; you have to trust the manufacturer. But this incident proves that even well-funded companies can have fundamental security failures.

Data Exposure Risk for All IoT Devices: Every smart home device—security cameras, smart locks, thermostats, doorbells, refrigerators—communicates with someone's servers. If the authorization logic on those servers is similar to DJI's, those devices could have similar vulnerabilities. The fact that Azdoufal discovered this suggests similar vulnerabilities might exist elsewhere.

Smart Home Security Is Cumulative: Your smart home security is only as strong as its weakest device. If you have a perfectly secure smart lock but a vulnerable robot vacuum, an attacker might use the vacuum to get into your network and access other devices. A home automation network is a system, and every component affects the security of the whole system.

Need for Transparency and Disclosure: When vulnerabilities are discovered, how companies respond matters. DJI's relatively quick response to Azdoufal's responsible disclosure was good. But what about vulnerabilities that nobody's discovered yet? The only way consumers can be informed about risks is if researchers can disclose vulnerabilities. Some companies threaten legal action against researchers who find security issues, which discourages disclosure. The industry needs stronger norms around responsible disclosure.

Regulatory Solutions May Be Necessary: The free market hasn't solved IoT security because there's no direct financial incentive for manufacturers. A company that spends more on security doesn't necessarily win more customers—consumers can't easily verify security. This suggests regulatory solutions might be needed. Some governments are exploring IoT security standards and disclosure requirements.

The vulnerability likely existed from early 2025 until mid-2026, with partial fixes applied in early 2026. Estimated data.

How to Choose Secure Smart Home Devices Going Forward

While no device is completely risk-free, there are ways to make smarter choices about which smart home devices to purchase and how to use them.

Research Security History: Before buying any IoT device, spend 10 minutes searching for the device name plus "security vulnerability" or "security issues." If the device has a history of security vulnerabilities and slow response to patches, that's a red flag. Companies that respond quickly and transparently to security issues tend to be more security-conscious overall.

Check Security Certification and Audits: Some devices undergo third-party security audits. Look for certifications like UL IoT Security or Common Criteria certification. While these aren't perfect, they indicate the company invested in security validation.

Prefer Companies With Larger Security Teams: Larger companies are more likely to have dedicated security researchers and secure development practices. This doesn't make them immune to vulnerabilities, but it makes vulnerabilities less likely. When evaluating a product, look at the company's job postings—if they're hiring security engineers, that's a positive sign.

Support Updates and Repairability: Choose devices from companies with a track record of releasing security updates. This means the manufacturer must support the device beyond the initial launch. Additionally, support for repairability means you might be able to fix issues if they arise. Companies that design products to be repairable tend to think more long-term about security.

Minimize Data Exposure: Not all smart home data is equally sensitive. A smart light that knows when you turn it on is less sensitive than a security camera or a device that maps your home. When possible, choose devices that collect and expose less data. Ask: "Does this device really need to send this data to the cloud?" Many features could work locally without sending data to a vendor's servers.

Network Segmentation: Connect smart home devices to a separate WiFi network from your primary computers and sensitive devices. If one smart home device is compromised, network segmentation limits what an attacker can reach. Many modern routers support creating a "guest network" for exactly this purpose.

Disable Unnecessary Features: If your robot vacuum has a feature you don't use, see if you can disable it. For example, if you don't need remote camera access, disable that feature. Fewer capabilities mean fewer attack surfaces.

What Manufacturers Must Do Differently

The responsibility for fixing IoT security doesn't lie with consumers—it lies with manufacturers. Here are the critical changes that companies like DJI must implement.

Implement Proper Authorization Checks: Every server request that references a specific device must verify that the authenticated user actually owns that device. This should be enforced consistently across the entire API, not just specific endpoints. Authorization must be checked server-side on every request.

Separate Authentication from Authorization: Stop treating a valid token as sufficient permission. Implement a proper permission system where you check both: Is this request authentic? Does this user have permission to access this resource? Make these completely separate checks.

Use Established Security Frameworks: Don't invent your own security logic. Use well-tested frameworks and libraries designed for authorization. OAuth 2.0 for authentication, attribute-based access control (ABAC) for authorization. These exist because they've been battle-tested.

Implement Rate Limiting and Monitoring: Even with proper authorization, monitoring can catch attacks. If one device suddenly makes thousands of requests, that's abnormal and should trigger alerts. Rate limiting prevents attackers from harvesting data at scale.

Regular Security Audits: Hire external security firms to audit your systems before launch, not after a vulnerability is discovered. This costs money, but it's much cheaper than dealing with a major security incident.

Bug Bounty Programs: Create financial incentives for researchers to find vulnerabilities responsibly. When researchers can make money reporting vulnerabilities, they're more likely to report them to you rather than selling them on dark markets.

Transparency in Security Practices: Publish information about your security practices. Which frameworks are you using? What's your incident response process? How long before you typically patch vulnerabilities? Transparency builds trust.

Assume-Breach Mentality: Design systems assuming they'll be breached. Implement strong logging, enable easy data deletion, limit what data is stored. If your system is breached, can you quickly identify what was accessed and delete it?

The Role of Responsible Disclosure

Azdoufal's decision to responsibly disclose this vulnerability rather than publicly weaponize it probably prevented significant real-world harm. His actions demonstrate why the security community values responsible disclosure, even when it feels slower than public shaming.

The Responsible Disclosure Process: Azdoufal discovered the vulnerability, privately contacted DJI, gave them time to patch, and only went public after patches were deployed. This is the standard practice in security research and it works. Companies get time to fix issues before attackers know about them.

Why Public Disclosure Can Cause Harm: If Azdoufal had immediately published detailed instructions on how to exploit this vulnerability, sophisticated attackers would have immediately started harvesting floor plans and camera feeds from thousands of homes before DJI could patch. The coordinated disclosure approach minimized that risk.

The Trust Problem: Responsible disclosure only works if companies can be trusted to actually patch vulnerabilities. Some companies ignore researchers or try to suppress disclosure. This is why some researchers choose public disclosure—to force companies to act. But when the process works, private disclosure is better for users because it gives manufacturers time to patch before attacks happen at scale.

Industry Trend: The cybersecurity industry is moving toward "coordinated disclosure" where researchers give companies a specific timeframe (like 90 days) to fix vulnerabilities before public disclosure. This balances the need for transparency with the need to prevent mass exploitation.

Lessons From Similar IoT Vulnerabilities

The DJI Romo vulnerability follows a pattern we've seen repeatedly in IoT security. Looking at similar vulnerabilities helps us understand what's likely to happen next.

Similar Vulnerabilities: Wyze Cameras: Security researchers discovered that Wyze camera cloud endpoints didn't properly verify ownership. Attackers could access any camera by guessing camera IDs. The vulnerability was similar to DJI's—poor authorization checking on the backend.

Mirai Botnet: The infamous Mirai botnet infected hundreds of thousands of IoT devices (security cameras, baby monitors, DVRs) by trying default credentials. This was a different vector (exploiting default passwords instead of authorization flaws), but it demonstrated how vulnerable IoT devices are and how easily they can be weaponized at scale.

Ring Doorbell Vulnerabilities: Multiple security research teams have discovered vulnerabilities in Ring doorbells' cloud infrastructure. The pattern is consistent: devices transmit data to cloud servers, and the authorization layer is weak.

Pattern Recognition: The recurring pattern is that IoT manufacturers focus on getting the device to work and connect to the cloud, but they shortcut the security of the cloud backend. The device itself might be technically sound, but the server-side logic is where corners get cut.

Long-Term Solutions and Industry Evolution

Fixing IoT security requires changes at multiple levels: technology, policy, and culture.

Government Regulation: Some governments are developing IoT security standards. The UK has the Secure by Design principle, and the US is developing IoT cybersecurity standards. As these mature, manufacturers who don't meet standards could face legal liability. This creates the economic incentive that the free market hasn't provided.

Industry Standards: Organizations like the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) are developing standards for IoT security. As these become established, they'll guide manufacturers on best practices.

Security-First Culture: Ultimately, the industry needs to shift from "security as an afterthought" to "security as foundational." This means hiring security experts early in product development, not after launch. It means accepting that security adds complexity and costs, and those are worthwhile investments.

Consumer Awareness: As consumers understand IoT security risks better, they'll demand more from manufacturers. Public incidents like the DJI Romo vulnerability help raise awareness. When a product gets negative press for security, that impacts sales and brand reputation. Companies respond to market pressure.

Timeline of Smart Home Security Evolution

2010-2014: Early smart home devices had minimal security. Many used default credentials or no authentication at all.

2014-2016: Major botnet attacks (Mirai) highlighted the risk of insecure IoT devices. Industry started paying attention.

2016-2020: Gradual improvement. Companies started implementing authentication, though authorization remained weak.

2020-2023: Increased regulatory pressure. Privacy regulations like GDPR started applying to IoT devices.

2024-2025: More security-conscious design. Companies like Apple pushed HomeKit security standards. But significant vulnerabilities like the DJI Romo issue still occur.

2025-2030 (Projected): More government regulation. Expectation is that IoT security standards will become mandatory in many jurisdictions. Only compliant devices will be sold.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for the IoT Industry

The DJI Romo robot vacuum security vulnerability represents a critical failure in how IoT manufacturers approach security. It's not a sophisticated exploit or an obscure attack—it's a fundamental misunderstanding of how to build secure systems. A token being valid doesn't mean a user can access everything. Authentication and authorization are separate concerns. These aren't new concepts; they've been foundational principles in computer security for decades.

What makes this vulnerability significant is its scale and impact. Thousands of homes had their security compromised. Complete floor plans were exposed. Camera feeds were accessible. This wasn't a theoretical vulnerability—it was real, exploitable, and could have enabled everything from targeted burglary to mass surveillance.

The positive note is that Sammy Azdoufal discovered this responsibly. He didn't weaponize it or sell it to criminals. He disclosed it privately, allowing DJI to patch it before attackers could exploit it at scale. This is how the security community should work. But we shouldn't depend on the good intentions of researchers—we need manufacturers to build security in from the start.

For consumers, the lesson is clear: smart home devices come with real security risks. Before purchasing any IoT device, research its security history. Look for evidence that the manufacturer takes security seriously. Use network segmentation to limit damage if a device is compromised. And support regulatory efforts to establish IoT security standards. The free market hasn't solved this problem; regulation might be necessary.

For manufacturers, the message is equally clear: security failures at scale destroy brand trust. DJI's reputation was damaged by this disclosure. Future products will face skepticism. The cost of investing in security upfront is far less than the cost of dealing with security incidents that damage your reputation and user trust.

The DJI Romo vulnerability is a watershed moment for IoT security. It shows that even well-funded, major manufacturers can have fundamental security failures. It shows that IoT devices in hundreds of thousands of homes can be simultaneously compromised. And it shows that we need systemic change in how the industry approaches security. The question now is whether the industry learns from this incident or whether it takes many more incidents before real change happens.

FAQ

What is the DJI Romo security vulnerability exactly?

The vulnerability was a critical authorization flaw in DJI's cloud servers. It allowed anyone with any DJI Romo's authentication token to access data from thousands of other DJI Romos and Power stations worldwide. An attacker could view live camera feeds, access 2D floor plans of homes, see real-time cleaning data, and potentially send remote commands to devices they didn't own. The vulnerability affected approximately 7,000 devices across 24 countries.

How was the vulnerability discovered and disclosed?

Sammy Azdoufal, a security researcher and AI strategy leader, discovered the vulnerability while reverse engineering DJI Romo's communication protocols to build a custom PS5 gamepad controller. He followed responsible disclosure practices by privately notifying DJI before publicly revealing the details. DJI deployed patches to partially mitigate the vulnerability, and Azdoufal eventually disclosed the technical details to raise awareness about the security issue.

What could attackers have done with this vulnerability?

With access to the vulnerability, attackers could have created a comprehensive database of home layouts and locations, monitored occupancy patterns through robot activity, conducted targeted surveillance through camera feeds, planned burglaries using floor plans, distributed malware through devices connected to home networks, or created a botnet using the devices' computing resources. The vulnerability had implications far beyond just privacy—it could have enabled physical crimes.

Why did DJI's security fail so completely?

DJI made a fundamental architectural mistake by treating authentication (verifying a user is legitimate) as sufficient for authorization (verifying a user can access specific resources). The servers would accept any valid authentication token and return data for any device, regardless of ownership. This is a classic insecure direct object reference (IDOR) vulnerability that should have been caught during code review or penetration testing. The failure likely resulted from time-to-market pressure, inadequate security review processes, and insufficient testing of authorization boundaries.

How could users protect themselves before patches were available?

Unfortunately, users had almost no practical mitigation options. Changing PINs wouldn't help since the vulnerability bypassed PIN authentication. Disabling WiFi wouldn't help since data was already exposed on DJI's servers. The only true protection was disconnecting the device entirely, which defeated the purpose of purchasing it. This illustrates why IoT security must be the manufacturer's responsibility—users can't protect themselves against server-level vulnerabilities.

What needs to change to prevent similar vulnerabilities?

Manufacturers must separate authentication from authorization, implement proper permission checks for every resource access, conduct security audits before launch, establish bug bounty programs to encourage responsible disclosure, embrace transparency about security practices, implement rate limiting and monitoring, and adopt a security-first culture. Additionally, government regulation establishing baseline IoT security standards could create economic incentives for manufacturers to prioritize security in product development.

How do I know if my smart home devices are secure?

Research the device manufacturer's security history by searching for known vulnerabilities. Check for third-party security certifications or audits. Evaluate the company's commitment to regular security updates and their track record of patching vulnerabilities quickly. Look at whether they have dedicated security teams (check job listings). Consider whether the device really needs cloud connectivity or if features could work locally. Use network segmentation by connecting IoT devices to a separate WiFi network from your main computers and devices.

Are all robot vacuums at risk of similar vulnerabilities?

While we can't specifically audit every robot vacuum manufacturer, the vulnerability reveals a pattern common across many IoT manufacturers: server-side authorization is frequently overlooked or inadequately implemented. Any IoT device that communicates with cloud servers has similar potential for authorization vulnerabilities. The industry as a whole has not prioritized secure API design, making authorization flaws a recurring problem in IoT devices, security cameras, smart locks, and other connected devices.

What is responsible disclosure and why does it matter?

Responsible disclosure is when a security researcher privately notifies a company about a vulnerability before publicly revealing details. This gives the company time to develop and deploy patches before attackers can exploit the flaw. The alternative, public disclosure, could enable mass exploitation before patches are available. Responsible disclosure is considered the ethical standard in security research because it minimizes harm to actual users while still ensuring vulnerabilities get fixed.

Key Takeaways

- A security researcher discovered that approximately 7,000 DJI Romo robot vacuums worldwide could be remotely accessed and controlled by anyone with an authentication token, exposing live camera feeds and home floor plans

- The vulnerability was a fundamental authorization flaw—DJI's servers verified that authentication tokens were valid but didn't check whether the user actually owned the device being accessed

- An attacker could have harvested floor plans, monitored occupancy patterns, conducted surveillance, planned burglaries, or distributed malware using thousands of devices simultaneously

- Users had almost no way to protect themselves before patches were deployed because the vulnerability existed at the server level, not at the device level

- This incident reveals systemic problems in IoT security: time-to-market pressure, skill gaps, inadequate security review, and lack of regulatory accountability create an environment where authorization flaws slip through development and into consumer devices

Related Articles

- iRobot's Chinese Acquisition: How Roomba Data Stays in the US [2025]

- Tenga Data Breach: What Happened and What Customers Need to Know [2026]

- Surfshark VPN Deal: Save 86% on Premium Plan Plus 3 Extra Months [2025]

- Best Ring Video Doorbell Alternatives With Local Storage [2025]

- Figure Technology Data Breach [2025]: What Happened and What You Need to Know

- Social Security Data Handover to ICE: A Dangerous Precedent [2025]

![DJI Romo Security Flaw: How 7,000 Robot Vacuums Were Exposed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/dji-romo-security-flaw-how-7-000-robot-vacuums-were-exposed-/image-1-1771058147265.png)