Introduction: When Federal Checks Fail, States Step Up

The sun was already setting over Portland when the crowd started lining up outside Revolution Hall on a gray Wednesday evening in early 2025. People in weatherproof jackets and fleeces gathered well before 5 PM, anticipating something they could feel in the air. Just 24 hours earlier, federal prosecutors had issued a subpoena targeting Minnesota's attorney general. Now he was in Oregon, standing alongside three other Democratic state officials, ready to deliver a message that would echo across the country: the federal government might be in free fall, but the states weren't going down without a fight.

This wasn't a radical political rally. This was a town hall organized by state law enforcement officers, the people constitutionally charged with defending their citizens and their states' sovereignty. And their message was visceral: we are not backing down.

What's happening right now represents something fundamentally different from previous political cycles. When the federal government becomes what Democratic attorneys general openly describe as "lawless," and when Congress refuses to act as a check on executive power, the entire architecture of American government shifts. The separation of powers no longer works vertically across branches in Washington. It works horizontally, across states and the federal government. And the attorneys general have become the primary defenders of that separation.

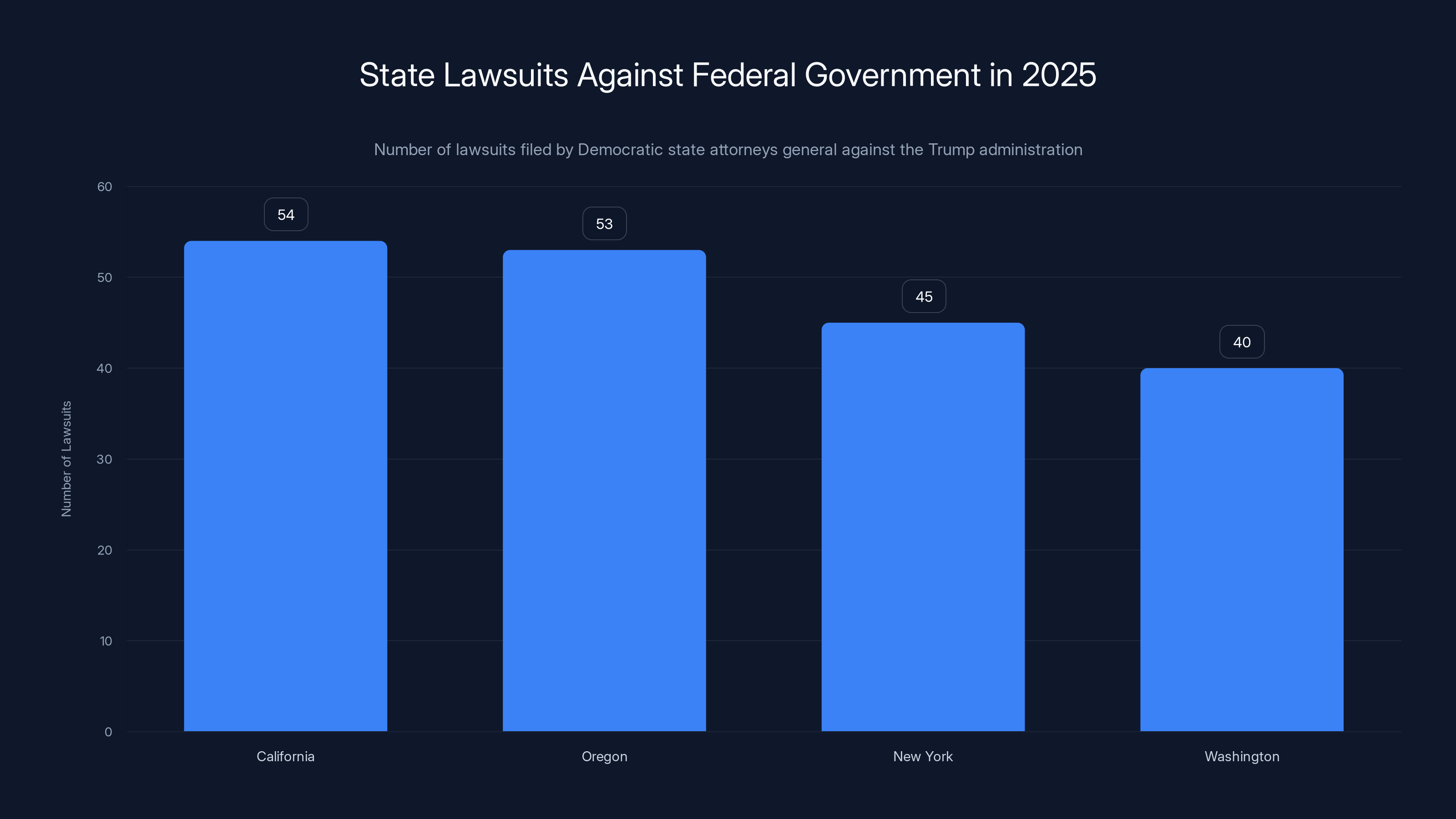

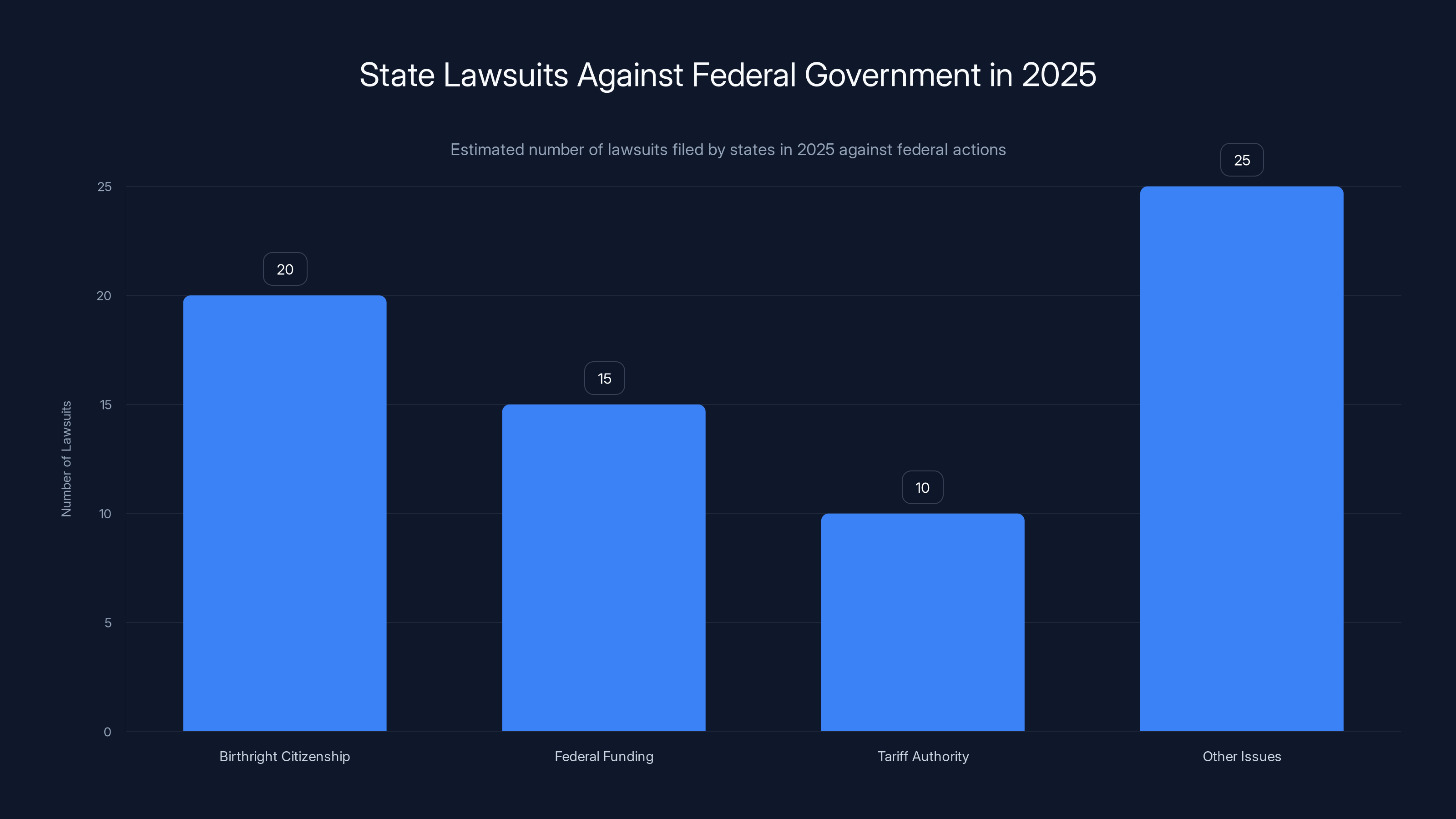

Over the course of just one year, these 24 Democratic state attorneys general filed more than 70 lawsuits against the Trump administration. They've blocked attempts to end birthright citizenship, fought efforts to withhold congressionally appropriated funds, challenged tariff authority, and litigated against federal overreach in immigration enforcement. Some states appeared in dozens of cases. California participated in 54 of them. Oregon in 53. What started as a coordinated legal strategy has become something resembling a constitutional resistance movement, conducted entirely through the courts.

The irony is thick: in a moment when the federal government's checks and balances have supposedly failed, when Republicans control Congress and the presidency, when the judiciary is conservative-leaning, the only meaningful institutional opposition left standing is the collective power of state governments. And they're coming for the Trump administration with everything they have.

TL; DR

- 70+ lawsuits filed: Democratic state AGs launched unprecedented legal offensive against Trump administration in first year of second term

- Birthright citizenship blocked: AGs successfully challenged executive order violating constitutional provision through courts

- Funding frozen: States recovered billions in congressionally appropriated funds Trump administration attempted to withhold

- Tariff challenges mounted: Multiple legal battles tested presidential authority over trade policy

- Coordinated strategy: 24 states in constant communication, with staffers in near-constant collaboration

- Bottom line: State attorneys general have become the primary institutional check on federal executive power when other branches fail

In 2025, Democratic state attorneys general filed numerous lawsuits against the Trump administration, with California and Oregon leading with 54 and 53 cases respectively. Estimated data.

How We Got Here: The Collapse of Federal Checks and Balances

Understanding why state attorneys general have become so aggressive requires stepping back and looking at how the federal system broke down. The Constitution was designed with three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. Each was supposed to check the others. Congress controlled the purse strings. The courts could strike down unconstitutional laws. The presidency executed the laws Congress wrote.

In theory, this created a self-correcting system. In practice, it required all three branches to function normally. It required Congress to take its oversight responsibilities seriously. It required the courts to act quickly enough to matter. And it required presidents to respect constitutional limits.

By January 2025, none of these assumptions held true anymore.

Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress. When a Republican president asked for Republican legislators' cooperation, they complied. As California Attorney General Rob Bonta put it at the town hall, the Republican Congress wasn't merely allowing Trump to act. They were actively supine. They weren't checking anything. They had surrendered their role entirely. A body that's supposed to be a coequal branch of government had abdicated its responsibility.

That left two institutions: the courts and the states.

The courts were slower. Filing a lawsuit, waiting for preliminary injunction hearings, appealing decisions up the chain—all of this takes time. Months, often. And when the Trump administration kept acting first and asking permission later, the timeline mattered. People would be deported before a judge could rule. Rights would be stripped before an appeal could be heard. The courts were necessary, but they couldn't stop everything by themselves.

Which meant the states had to move first. And move they did.

The constitutional foundation for this state action was always there. The Tenth Amendment reserves powers not granted to the federal government to the states. States have their own attorneys general, their own court systems, and their own sovereignty. For decades, though, state AGs had rarely coordinated at this scale or litigated against federal actions with such intensity. The precedent existed. The authority existed. What was new was the willingness to exercise it.

By the time the Portland town hall happened, it was clear this wasn't a temporary reaction to one or two controversial policies. This was a sustained institutional response to what Democratic AGs genuinely believed was a lawless administration. And the evidence they would cite for that claim came from the very first week of Trump's second term.

The Birthright Citizenship Gambit: When the Executive Tried to Rewrite the Constitution

One of the earliest and most revealing flashpoints involved birthright citizenship. This is a case study in both the illegality of Trump's initial moves and the speed at which state AGs had to respond.

Birthright citizenship is enshrined in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. It states: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." This has been law for 160 years. The Supreme Court affirmed it in United States v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898. It's not ambiguous. It's not a gray area. It's bedrock constitutional law.

Yet the Trump administration issued an executive order attempting to end birthright citizenship anyway. The logic was that illegal immigrants aren't fully "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States, so their children born here wouldn't automatically become citizens. This interpretation directly contradicted 160 years of constitutional understanding. It wasn't a policy disagreement. It was an attempt to overrule the Constitution through executive fiat.

A year before the Portland town hall, when this order was being anticipated, the Democratic state AGs had already begun preparing. They'd been on calls discussing strategy, identifying which states would be lead plaintiffs, researching the legal arguments. When the order dropped, they sued within 24 hours. Not weeks. Not months. Twenty-four hours.

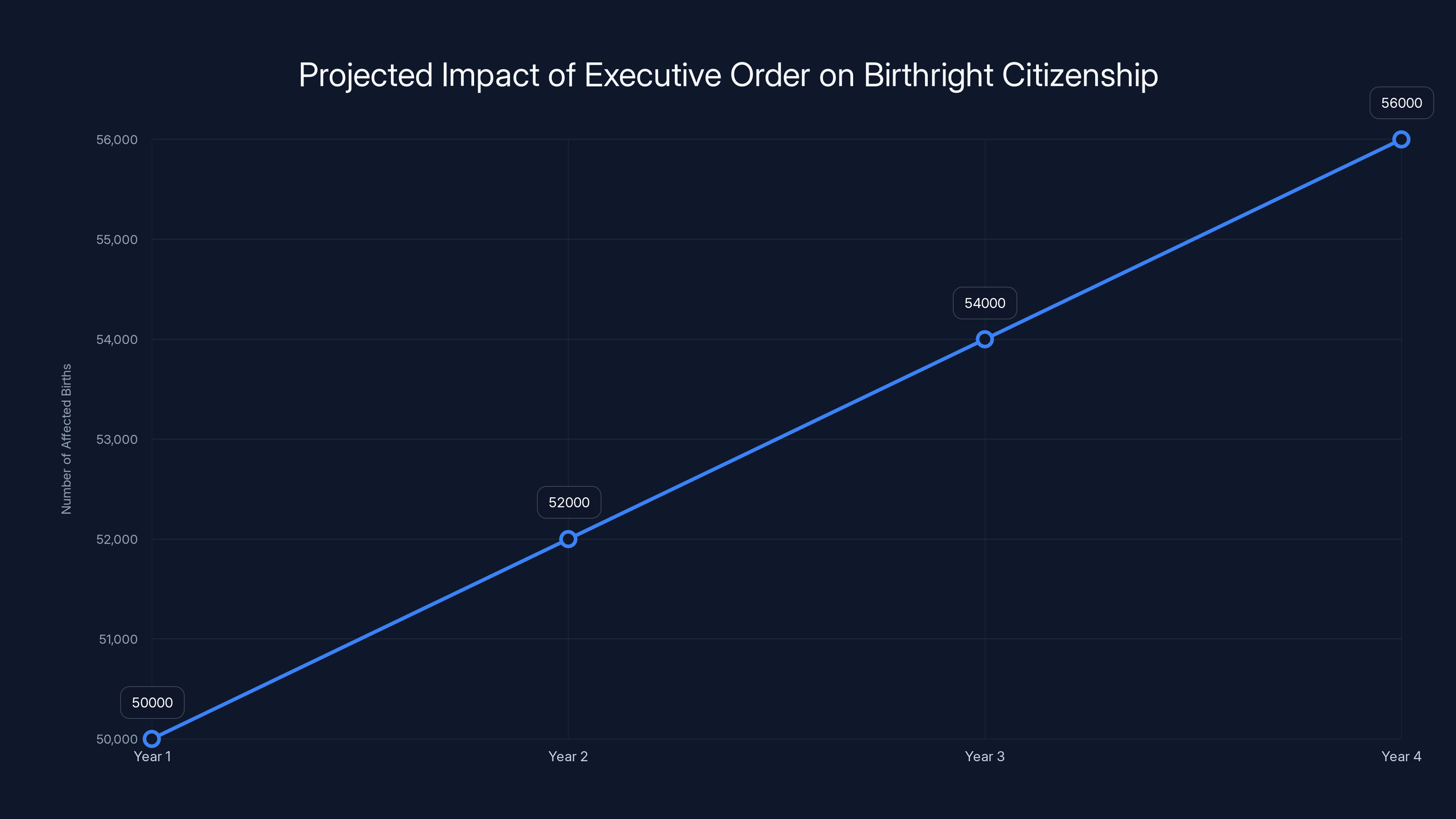

This speed mattered because it showed the AGs understood something fundamental about how the Trump administration operated. It acted first, defended the action later, and by the time courts intervened, facts on the ground had changed. Children wouldn't be reclassified as non-citizens retroactively—that would be too chaotic. But going forward, tens of thousands of births per year would be affected. The only way to prevent that was to move immediately.

The case would wind through the courts. But the existence of a coordinated, rapid response from 23 state governments sent a message: this administration couldn't simply rewrite the Constitution and expect no institutional resistance.

What made the birthright citizenship case particularly instructive was that it illustrated the administration's method. The order itself was almost certainly unconstitutional. The legal argument supporting it was thin. But the administration knew that by the time courts fully litigated the question, months would have passed. Confusion would reign. State governments might struggle with implementation. And the delay itself was a kind of victory.

State AGs understood this and acted accordingly. They weren't going to wait. They were going to tie the administration up in court from day one.

Estimated data shows that if the executive order had been implemented, tens of thousands of births per year could have been affected, highlighting the urgency of the legal response.

The Funding Wars: When Trump Tried to Starve the States

But birthright citizenship was just the opening move. The real existential threat came when the Trump administration began attempting to withhold congressionally appropriated funding from the states.

This is where the conflict became truly serious. Budget authority is Congress's power, not the president's. Congress decides how much money gets allocated to federal programs that flow to the states. Once Congress appropriates that money, the president doesn't have discretion to withhold it because they disagree with state policies or their own political priorities. This principle goes back to the Appropriations Clause of the Constitution itself.

Yet the Trump administration, backed by a newly emboldened Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), began withholding funds. Grants that had been approved. Medicaid reimbursements. Environmental funding. The justification was various, but the pattern was clear: if your state didn't align with Trump administration priorities, your federal funding was in jeopardy.

From a state perspective, this was an extraordinary overreach. States depend on federal funding to operate everything from healthcare programs to infrastructure projects. Doctors and hospitals depend on that funding. Highway construction depends on that funding. The ability of the federal government to simply seize that leverage and weaponize it against states meant that the entire system of federalism was being inverted.

State AGs sued. And they sued repeatedly. Over the course of just a few months, they filed lawsuit after lawsuit challenging different aspects of the funding withholding. Hawaii Attorney General Anne Lopez emphasized that despite political differences, the 24 Democratic AGs had to maintain absolute discipline about not letting their own egos get in the way of collective defense. The message was clear: this wasn't about partisan politics. This was about institutional survival.

And here's where the courts actually mattered. Preliminary injunctions started flowing. Federal judges, many of them appointed under prior administrations, began blocking the withholding. States got their money. Billions of dollars flowed back. The constitutional principle—that presidents cannot simply refuse to spend money Congress appropriated—held.

But it only held because state AGs forced the courts to rule quickly and forcefully. Without that coordinated legal pressure, the administration would have dared to continue pushing boundaries.

The funding battles also revealed something about the strange coalition that had emerged. Maine Attorney General Aaron Frey explicitly invited Republican state AGs to join the lawsuits. He noted that Republican AGs had stayed completely out of the federal-state conflicts. They hadn't joined Trump administration litigation against other states. They'd simply... stayed home. It was the most civically ambiguous choice imaginable: pretend the constitutional crisis isn't happening.

But Democratic AGs couldn't make that choice. They served constituents depending on federal funding. They had to act.

The Tariff Litigation: Testing the Limits of Executive Authority

Just when it seemed the conflicts might stabilize, the Trump administration opened a new front: unilateral tariffs. Presidents have broad authority over trade policy under existing statutes. But the question of how far that authority extends became a major legal battleground.

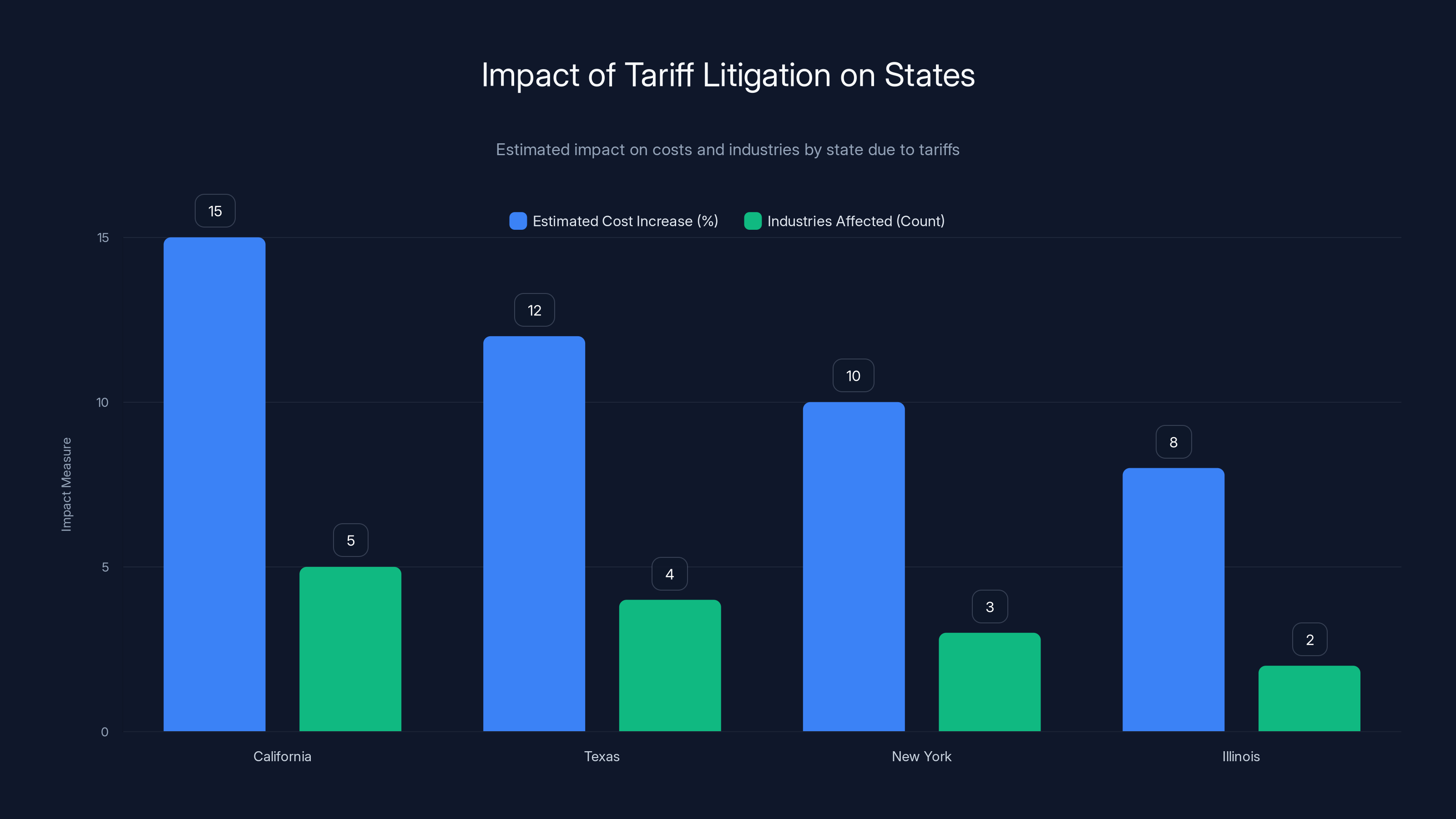

The tariff executive orders imposed duties on imports from various countries. Some states sued because the tariffs would increase costs for their residents. Others sued because they affected specific industries important to their economies. And all of them sued because the scale and scope of what the administration was attempting suggested a president operating without meaningful constitutional restraint.

This litigation was more complicated than the birthright citizenship case because the legal ground was genuinely unsettled. Presidents do have broad trade authority. But does it extend infinitely? Can they impose tariffs on allies? Can they do it without waiting for congressional action? Can they use tariffs as general economic policy rather than specific trade remedy?

State AGs were essentially forcing courts to answer these questions. And by forcing them, they were preventing the administration from operating in a legal vacuum. The administration couldn't simply assume that because Congress wasn't actively checking it, courts wouldn't either.

The Constitutional Framing: States as the Final Check

California Attorney General Rob Bonta articulated the constitutional theory behind what the state AGs were doing. The federal government, he said, had three checks built into it: the executive checks the legislative branch, the legislative checks the executive, and the judicial branch checks both. By 2025, at least in Bonta's assessment, all three of those internal checks had failed. The judiciary was conservative and often deferential. Congress was controlled by the same party as the president. The system had broken.

But the Constitution had a fourth check that most people don't think about as actively as they should: the states themselves.

The separation between the federal government and state governments is written into the Tenth Amendment. It's in the Supremacy Clause. It's in the structure of the entire document. States aren't supposed to be subordinate administrative units of the federal government. They're supposed to be independent sovereigns that delegate specific powers upward to a federal government of limited, enumerated powers.

When that federal government exceeds its bounds, states have both the authority and the responsibility to defend their sovereignty. That's not a radical interpretation. That's the basic constitutional structure. And for most of American history, that check had been relatively dormant because the federal system was in better equilibrium. But when equilibrium breaks, the mechanism activates.

What Bonta and his fellow AGs were saying was simple: if you want to know what happens when the federal government becomes lawless, watch the states. We are the Constitution's backup generator.

This wasn't theoretical anymore. By the Portland town hall, it was operational. State AGs had built an infrastructure of coordination. They had staff working in constant communication. They had identified key issues where state interests aligned. They had begun thinking of themselves as a united front against federal overreach.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison's language was particularly direct. When you're confronted by a bully, he said, staying quiet won't work. The only solution is to stand up and fight back. But importantly, he was talking about institutional bullying, not just political disagreement. The question was whether the executive branch would respect constitutional limits. And if Congress wasn't going to enforce those limits, states had to.

California and Oregon led the charge with 54 and 53 cases, respectively, showing strong leadership in the legal battle against federal policies.

The Coordination Machine: How 24 States Became a Legal Army

The scale and speed of litigation that Democratic state AGs achieved in the first year of Trump's second term was unprecedented. Seventy lawsuits. Multiple legal fronts. Coordinated strategy across different cases. This didn't happen by accident.

Early on, the AGs had been on daily phone calls. That was unsustainable long-term, but it allowed them to align on strategy at a critical moment. They identified which state would be the lead plaintiff on which issue. California, the largest and wealthiest state with vast resources, took on 54 cases. Oregon, led by the energetic Dan Rayfield, participated in 53. Smaller states picked their battles based on where they had the most at stake.

But the real coordination happened at the staff level. Assistant attorneys general, policy experts, constitutional scholars—these people were in nearly constant communication. When one state prepared a legal motion, others could adapt it for their own cases. When one court ruled favorably, the reasoning could be cited in other jurisdictions. The effect was multiplicative. One strong legal argument became 20 variations across 20 different cases.

Hawaii Attorney General Anne Lopez emphasized that the key to making this work was suppressing ego. The Democratic AGs were from different states, different regions, different political cultures. They had different priorities. But they had to act as one. "What we're doing is too serious, too important to let our own egos get in the way," she said.

This kind of institutional coordination didn't come naturally. It required deliberate choice. It required the AGs to agree that federal overreach was a bigger threat than any individual state's competitive advantage. It required them to see themselves as a collective defending a system, not competitors trying to optimize their own position.

By the time of the Portland town hall, that coordination was well-established. The question was whether it could be sustained. Litigation is slow. Court dockets are crowded. Some of the cases might drag on for years. The AGs would need to maintain momentum and unity across multiple election cycles, changing administrations, and shifting political winds.

What also became clear was that the Republican state AGs had made a choice to sit out the conflicts. Maine's Aaron Frey explicitly invited them. They didn't join. Whether that was because they genuinely didn't see federal overreach as a threat to their states, or because they didn't want to break with their Republican governor counterparts, or for some other reason, the effect was the same. The constitutional check from state governments came entirely from Democratic AGs.

This was both a strength and a weakness. A strength because it meant unified action without Republicans forcing compromises. A weakness because it meant the resistance was entirely partisan, which undermined claims that this was about defending the Constitution rather than opposing Trump.

Birthright Citizenship: The Constitutional Baseline

Let's look more closely at the birthright citizenship litigation because it reveals how the entire system works.

The Trump administration's executive order claimed that children born in the United States to illegal immigrants wouldn't automatically become citizens. The theoretical basis was that illegal immigrants aren't fully "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States. If a person isn't subject to U. S. jurisdiction, the argument went, neither is their child.

This interpretation required reading the 14th Amendment in a way that 160 years of law had rejected. The Supreme Court's 1898 decision in Wong Kim Ark involved a child born to Chinese immigrants who were legally present but not citizens. The Court ruled that the child was a citizen because he was born in the United States. The "subject to the jurisdiction" language was read to exclude only children of foreign diplomats and occupying armies, not immigrants.

State AGs argued, not particularly controversially, that this precedent controlled. The executive order was simply unconstitutional. It attempted to overturn the 14th Amendment through an executive order. That's not within presidential authority.

But here's where the timing and strategy mattered. If state AGs had waited for normal litigation timelines, the order would have been in effect for months. Hospitals would have been unsure whether to issue birth certificates. Immigration officials would have been applying a new interpretation. The chaos would have created facts on the ground. By the time courts ruled, reversing the damage would be messy.

So state AGs moved immediately. They filed injunctions asking courts to freeze the order pending the full case. Several courts granted those injunctions. The order was blocked before it really took effect. And once it was blocked, the case became less urgent. Courts could take their time analyzing the merits. The immediate crisis was over.

This is the state AG playbook: move fast, force preliminary action, and prevent irreversible damage from happening while litigation proceeds.

Federal Funding: The Leverage Game

The funding withholding litigation was different because it was also an economic battle. When the Trump administration tried to freeze federal funds flowing to states, they were directly threatening state budgets. Every dollar withheld was money that couldn't fund Medicaid, education, transportation, or any of the dozens of programs that depend on federal appropriations.

The constitutional principle was clear: the Appropriations Clause gives Congress—not the president—the power of the purse. Once Congress appropriates money, the president doesn't have discretion to withhold it based on policy disagreements.

But from a practical standpoint, the impact was severe. States were operating on the assumption that appropriated funds would flow. They'd budgeted around it. When funds were frozen, they had to scramble.

State AGs filed lawsuits seeking preliminary injunctions that would restore funding while litigation proceeded. Courts generally granted these injunctions, reasoning that the states would likely prevail on the merits and that the harm from not having appropriated funds was severe and irreparable.

The result was that states recovered billions in federal funding. The check on presidential power held. But it only held because state AGs moved fast enough to prevent irreversible damage.

In 2025, states filed a significant number of lawsuits against federal actions, with over 70 cases in total. This highlights the scale of state-level legal actions as checks on federal power. (Estimated data)

The Tariff Wars: Uncharted Constitutional Territory

Tariff litigation was less certain because presidential authority over trade is genuinely broad. Several statutes give presidents power to impose tariffs in various circumstances. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the Trade Act of 1974, and other legislation provide legal hooks for trade action.

But the question of how broad that authority can be stretched is genuinely unsettled. Can a president impose tariffs on allies? On all countries without distinction? As general economic policy rather than specific trade remedies?

State AGs were forcing courts to answer these questions. They sued arguing that the scale of the tariff orders exceeded whatever authority Congress had granted. They argued that the effects on the states and their residents were unconstitutional. They forced judges to grapple with the limits of executive power in an area where those limits weren't clearly defined.

This was a riskier litigation strategy than the birthright citizenship or funding cases because the legal ground was less settled. State AGs might lose. But by forcing litigation, they prevented the administration from operating in a legal vacuum. Courts would set boundaries, even if those boundaries were different than what AGs hoped.

The Pattern: Executive Lawlessness and Institutional Response

Looked at individually, any one of these cases might have been manageable. Birthright citizenship case, fund withholding case, tariff case—each was serious but might have been dealt with in isolation.

But what the Democratic state AGs were highlighting was the pattern. Again and again, the administration was attempting actions that violated the Constitution or exceeded executive authority. Again and again, they were betting that speed and chaos would prevent effective institutional response. Again and again, Congress was doing nothing.

Under those conditions, state AGs argued, they had no choice. Someone had to defend the Constitution. Someone had to enforce limits on executive power. Someone had to be the institutional check when other branches failed. That someone had to be the states.

Keith Ellison's language about confronting bullies directly articulated this logic. If you assume the bully won't attack because you're quiet, you're wrong. The only solution is to stand up and fight. In institutional terms, that meant being aggressive in court, moving fast, coordinating across state lines, and not yielding ground.

Rob Bonta's point about separation of powers was that the Constitution had multiple redundant checks. The system was designed assuming that internal federal checks might fail. The answer was the states. When California or New York or Massachusetts sued the federal government, they were exercising a check that was designed into the constitutional structure.

But exercising that check required institutional capacity and political will. It required 24 states agreeing to act together. It required their attorneys general to treat federal overreach as a higher priority than partisan gain. It required them to suppress ego and maintain coordination across months and years of litigation.

Whether they could sustain this was an open question.

The Republican Silence: A Choice with Consequences

One notable aspect of the state AG battles was the complete absence of Republican state attorneys general from the litigation.

Aaron Frey, Maine's attorney general, explicitly invited Republican AGs to join. The legal arguments about constitutional limits on executive power, appropriations authority, and federal overreach weren't inherently partisan. A Republican could theoretically have sued over birthright citizenship if they believed it was unconstitutional, or over funding withholding if their state was affected.

But Republican AGs didn't join. Some states had Republican governors and Democratic AGs, or Republican legislatures and a partisan AG. The federal AG battles remained entirely Democratic.

This might have reflected genuine disagreement about whether the Trump administration was acting unconstitutionally. Or it might have reflected unwillingness to break with Republican political leadership. Or it might have been simple calculation that it was easier to let Democratic AGs do the heavy constitutional lifting and sit out the fights.

The effect was to make the state AG litigation appear partisan rather than principled. Democratic AGs fighting Republican administration. Democratic states against Republican federal government. This narrative was less powerful than it would have been if some Republican AGs had joined to defend federalism as an abstract principle.

But from a practical perspective, it might not have mattered much. The Democratic AGs had enough resources and enough coordination to file the lawsuits and win the preliminary injunctions that mattered. Whether Republicans joined or not, the litigation was happening.

The tariff litigation affected different states by increasing costs and impacting key industries. California faced the highest estimated cost increase and industry impact. (Estimated data)

The Courts' Role: Faster than Usual, Still Slow

One theme running through the state AG litigation was the strange relationship between speed and litigation. The AGs moved fast—filing within 24 hours of the birthright citizenship order, immediately seeking injunctions, coordinating across states rapidly.

But "fast" litigation is still slow by the standards of immediate political action. Preliminary injunctions might come within weeks. Full rulings take months. Appeals take years. By the time a case is fully litigated, administrations might have changed or policies might have shifted.

This created an interesting dynamic. The courts were helping states freeze harmful action through preliminary injunctions, but they weren't creating comprehensive legal resolutions. Judges were ruling in narrow ways that prevented immediate harm while leaving broader questions for later.

For example, in the funding cases, courts ruled that the specific withholding violated the Appropriations Clause. But they didn't create a comprehensive framework for thinking about all possible scenarios where a president might try to condition federal funding. That would come later, if litigation continued.

The effect was that state AGs and the administration were engaged in a continuous dance: the administration tried something, state AGs sued, courts issued a preliminary injunction, and the process repeated with the next controversial policy.

This was more effective than nothing. The preliminary injunctions meant that states got funding and that policies like the birthright citizenship order were frozen. But it also meant that the constitutional questions remained partially unsettled, which would matter if the administration appealed or if circumstances changed.

The Precedent Question: How Much Can Presidents Exceed Their Authority?

One broader question hanging over all of this litigation was how it would shape future presidential power. If Trump administration attempts at overreach were struck down repeatedly, would that establish boundaries that future presidents would respect? Or would each new president test those boundaries again?

Constitutional law doesn't work like statutory law. A court ruling that the president violated the Constitution in one case doesn't prevent future presidents from trying the same thing in a different context. Future litigation would then be necessary to enforce the same principle again.

But there was path-dependent reasoning at work too. If courts consistently ruled that certain types of executive action violated the Constitution, that created precedent. Future presidents would be less likely to attempt the same thing because they'd know they'd lose in court.

The state AG litigation was creating a record of what the Trump administration was attempting and what courts would tolerate. That record would matter for how future administrations operated.

But it also revealed something about the fragility of constitutional constraints. Constraints depend on institutions respecting them. If the executive branch believed it could act with impunity, or if Congress wouldn't enforce constitutional limits, then courts alone might not be enough. The fact that state AGs were willing to litigate was itself part of what made the system work.

The Sustainability Question: Can This Last?

The Portland town hall and the broader state AG litigation raised an implicit question: can this be sustained?

Litigation is expensive and slow. Maintaining coordination across 24 different states, each with different political cultures and different priorities, is hard. Momentum can be lost. Political will can fade. Leadership changes. Priorities shift.

The Democratic AGs seemed aware of this. Ellison's point about confronting bullies was partly about psychological resolve. You have to decide that this is important enough to keep fighting, even when the fight is long and the outcome is uncertain.

But sustaining that resolve across multiple years and multiple elections would be genuinely difficult. What happens if a Democratic AG is replaced by a Republican? What happens if states' economic interests shift and some states decide they benefit from federal policy? What happens if the Trump administration changes tactics and becomes less obviously illegal, making litigation cases harder to win?

These were open questions as of the Portland town hall. What was clear was that Democratic state AGs had chosen to make federal overreach a major focus. Whether they could sustain that focus was an open question.

The timeline illustrates the swift actions taken by state AGs to block the executive order on birthright citizenship, preventing potential chaos and allowing courts to deliberate without immediate pressure. (Estimated data)

The Broader Constitutional Crisis: When Federal Checks Fail

The state AG litigation was ultimately about a broader constitutional crisis: what happens when federal checks and balances fail?

The Constitution assumes that Congress will check the executive, that courts will check both, and that elections will check all three. But when one party controls Congress and the presidency, when the judiciary is ideologically aligned with the executive, when there are incentives to push constitutional boundaries, the internal federal checks become less reliable.

Under those conditions, the Constitution has a backup: the states. The separation between state and federal governments is designed to create a check when internal federal mechanisms fail. Democratic state AGs were essentially activating that backup mechanism.

But this raised uncomfortable questions about federalism. If states can sue to block federal action whenever they believe the federal government is acting unconstitutionally, doesn't that create a system where 24 states can veto federal policy? Don't we need some federal capacity to act without being immediately tied up in litigation?

Democratic AGs would respond that they were only opposing unconstitutional action. If the Trump administration stayed within constitutional bounds, there would be no litigation. The fact that they were suing repeatedly suggested the administration was genuinely exceeding its authority.

Republicans might counter that what Democrats viewed as unconstitutional overreach, they viewed as legitimate exercise of authority that Congress had delegated to the president. The disagreement was real and fundamental.

But what both sides had to acknowledge was that the normal federal system of checks and balances wasn't working. Something had to give. Either Congress would start asserting its power, or courts would start setting clearer boundaries, or states would continue to litigate, or some combination of all three would create a new equilibrium.

The Portland town hall was essentially a moment of state AGs saying: we're choosing option three. We're going to litigate our way to a sustainable constitutional equilibrium.

The Future of State Power: What Happens Next?

Assuming state AG litigation continued and they continued to win many of their cases, what would that mean for federalism and state power going forward?

One possibility was that it would rebalance the federal-state relationship. Over the past 80 years, federal power had grown substantially. States had become more like administrative units of the federal government than independent sovereigns. State AG litigation could reverse some of that trend by establishing that states could sue to block federal action they viewed as exceeding federal authority.

Another possibility was that it would ultimately lead to constitutional clarification. Maybe the result of years of litigation would be clearer rules about when states could sue, what the scope of federal power actually is, and how conflicts between state and federal authority should be resolved.

A third possibility was that it would create a new form of partisan federalism, where states aligned with one party constantly sued the federal government controlled by the other party. The constant litigation could gridlock the system and make it harder for any administration to govern.

All three possibilities were plausible depending on how things unfolded. But what seemed clear was that the old equilibrium—where state power was dormant and federal power was presumed broad—wasn't sustainable anymore. The Democratic state AGs were ensuring that.

Lessons from the Legal Battles: What We've Learned

Looking back at the specific cases—birthright citizenship, funding withholding, tariffs—several patterns emerged.

First, moving fast matters. The AGs that sued immediately had better odds of getting preliminary injunctions that prevented immediate harm. Waiting allowed bad facts to accumulate on the ground.

Second, constitutional clarity helps. The birthright citizenship case was the easiest to win because the law was clearest. Tariffs were harder because presidential authority was genuinely broad. When the Constitution is clearer, courts are more likely to stop executive action.

Third, coordination multiplies power. 24 states suing together had more impact than any single state could have achieved. They could divide the work, share resources, and present unified arguments across multiple jurisdictions.

Fourth, state resources matter. California's size and wealth meant they could participate in 54 cases. Smaller states couldn't match that. The distribution of resources affected which cases got the most attention.

Fifth, judicial temperament matters. Even conservative judges were often willing to enforce constitutional boundaries on executive authority, especially through preliminary injunctions. The judiciary was a more reliable check than Congress.

Sixth, speed creates uncertainty. By moving fast and filing cases immediately, state AGs created uncertainty for the administration about what would be allowed. That uncertainty itself is a form of constraint on executive action.

Conclusion: Democracy When Democracy Is Broken

The Portland town hall in January 2025 was a moment when institutions chose to fight rather than concede. The Democratic state attorneys general looked at an administration they believed was operating lawlessly, looked at a Congress that was refusing to check executive power, and decided that they would be the institutional check.

This wasn't a radical act. It wasn't even unusual in constitutional terms. States have always had the authority to sue the federal government. The Tenth Amendment reserves powers to the states. The Constitution is a federal document that creates a system of governments, not a unitary system with one sovereign authority.

What was unusual was the scale and coordination. 24 states acting together filed more than 70 lawsuits in a single year. They coordinated strategy, shared resources, and maintained discipline about priorities. They moved fast, seeking preliminary injunctions to prevent immediate harm. They used the courts to set boundaries on executive action.

And it worked. Birthright citizenship orders were blocked. Federal funding was restored. Tariff authority was questioned. The administration couldn't simply do whatever it wanted. There were institutional checks.

But the broader point was darker. The state AG litigation revealed that the normal federal checks on presidential power had largely failed. Congress wasn't checking anything. The presidency was testing boundaries repeatedly. The courts were helping, but they were slow. The only thing standing between an overreaching presidency and unchecked power was the willingness of state governments to litigate.

That's not a healthy constitutional system. A healthy system has multiple redundant checks all functioning normally. When you're down to relying on state litigation as your primary check on federal executive power, something has gone badly wrong with the federal structure.

But given that those federal checks had failed, Democratic state AGs made the rational institutional choice: activate the only remaining check. Go to court. Sue repeatedly. Move fast. Coordinate with other states. Use the courts to enforce constitutional boundaries.

The Portland town hall was a moment when that choice was made explicit. The AGs stood on stage and said: we are the check. We are the people defending the Constitution. We are not backing down. And they meant it.

What happens next depends on whether they can sustain that commitment across multiple years of litigation, changing politics, and shifting priorities. It depends on whether courts continue to rule in their favor. It depends on whether the Trump administration eventually backs down or continues to test boundaries.

But the moment itself was significant. In a system where federal checks have failed, state governments stepped forward to defend the Constitution. That's exactly what federalism is supposed to enable. Whether it proves sufficient is the question that will define American constitutional law for the next several years.

FAQ

What are state attorneys general and what powers do they have?

State attorneys general are the chief legal officers for their states, typically elected officials responsible for representing the state in legal matters. They have authority to sue on behalf of their states, defend state laws in court, and represent state citizens in legal matters. They can initiate lawsuits against federal actions they believe exceed federal authority or violate state interests.

How did Democratic state AGs coordinate their litigation strategy?

Democratic state AGs maintained daily phone calls in the early stages of Trump's second term to align on strategy. They identified which states would serve as lead plaintiffs in specific cases, shared legal research and arguments, and coordinated staffing to ensure consistent messaging across jurisdictions. This coordination infrastructure allowed them to multiply their legal firepower.

Why couldn't the courts stop executive overreach on their own?

Courts are constrained by litigation timelines. Even when judges rule quickly through preliminary injunctions, the process takes weeks or months. By that time, policies may have been partially implemented or uncertainty may have created harmful effects. State AG litigation accelerated the process by seeking immediate injunctions, but courts still couldn't prevent all damage from occurring.

What is birthright citizenship and why did Trump try to end it?

Birthright citizenship means that anyone born in the United States is automatically a U. S. citizen, regardless of their parents' immigration status. It's protected by the 14th Amendment. Trump sought to end it through executive order, arguing that children of illegal immigrants aren't "subject to the jurisdiction" of the U. S. This interpretation contradicted 160 years of constitutional law and was constitutionally questionable at best.

How did state AGs successfully block funding withholding?

State AGs sued arguing that the Appropriations Clause gives Congress, not the president, power over federal spending. Presidents cannot withhold congressionally appropriated funds based on policy disagreements. Courts generally granted preliminary injunctions, reasoning that states would likely prevail and that the harm from withheld appropriations was severe and irreparable.

Why didn't Republican state attorneys general join these lawsuits?

Republican state AGs chose not to participate in litigation challenging Trump administration actions. Whether this reflected genuine disagreement about constitutional questions or unwillingness to break with Republican political leadership remains unclear. Their absence meant the state AG litigation remained entirely Democratic, which made it appear more partisan than federalism-based.

Can state AG litigation create permanent constraints on executive power?

Court rulings establish precedent that guides future presidential behavior, but they don't prevent future presidents from testing boundaries again. Constitutional constraints depend on institutions respecting them. If future presidents ignore established law, new litigation would be necessary to enforce the same principles. The real constraint is the combination of legal precedent and institutional willingness to enforce it.

What happens if state AG litigation continues for years without resolution?

Prolonged litigation could drain state resources, create uncertainty for both state and federal governments, and potentially establish a pattern where states constantly sue the federal government. This could gridlock the system and make governing more difficult. Alternatively, it could lead to clearer constitutional rules about federal-state authority, creating more stability long-term.

What does the Constitution say about state power to sue the federal government?

The Tenth Amendment reserves powers not delegated to the federal government to the states. States have standing to sue in federal court to defend their sovereignty and their citizens' interests against federal action. The Supremacy Clause establishes that federal law is supreme when it's constitutional, but states can argue that federal action exceeds federal authority or violates constitutional boundaries.

Is state AG litigation an effective check on federal power?

State AG litigation has proven effective at preventing immediate implementation of controversial policies through preliminary injunctions and forcing courts to rule on constitutional questions. However, it's slower than congressional checks and more uncertain than having federal branches properly checking each other. It works best when combined with functional federal checks, which were not present in this case.

Related Articles (Auto-Generated)

[Related articles will be automatically populated based on shared tags]

Key Takeaways

- Democratic state AGs filed 70+ lawsuits against Trump administration in one year, with California participating in 54 cases and Oregon in 53

- States successfully blocked birthright citizenship order, restored federal funding, and challenged tariff authority through coordinated litigation strategy

- When federal checks and balances fail (Congress controlled by same party as executive, courts slow), state governments activate constitutional backup mechanism

- 24 states maintained near-constant staff coordination while leadership participated in daily phone calls, suppressing individual egos for collective defense

- Preliminary injunctions allowed states to prevent immediate harm while full litigation proceeded, recovering billions in federal funds within weeks rather than months

Related Articles

- FBI Device Seizure From Washington Post Reporter: Journalist Rights and First Amendment [2025]

- Minnesota Sues to Stop ICE 'Invasion': Legal Battle Over Operation Metro Surge [2025]

- Supreme Court Case Could Strip FCC of Fine Authority [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Case: Evidence Battle & Legal Strategy [2025]

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

- Offshore Wind Legal Victories: Why Trump's Setbacks Matter [2025]

![State Attorneys General Fight Trump: The Last Constitutional Check [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/state-attorneys-general-fight-trump-the-last-constitutional-/image-1-1769112469737.jpg)