Elon Musk's Moon Satellite Catapult: The Lunar Factory Plan Explained

When Elon Musk casually mentions building a satellite factory on the Moon with a giant catapult, most people dismiss it as another billionaire fever dream. But here's the thing—this isn't just idle speculation. In a recent meeting with x AI employees, Musk outlined a concrete vision: construct a "mass driver" launcher on the lunar surface to manufacture and launch AI satellites into orbit. The proposal sits at the intersection of audacious thinking and genuine engineering possibility, though the gap between idea and reality remains vast.

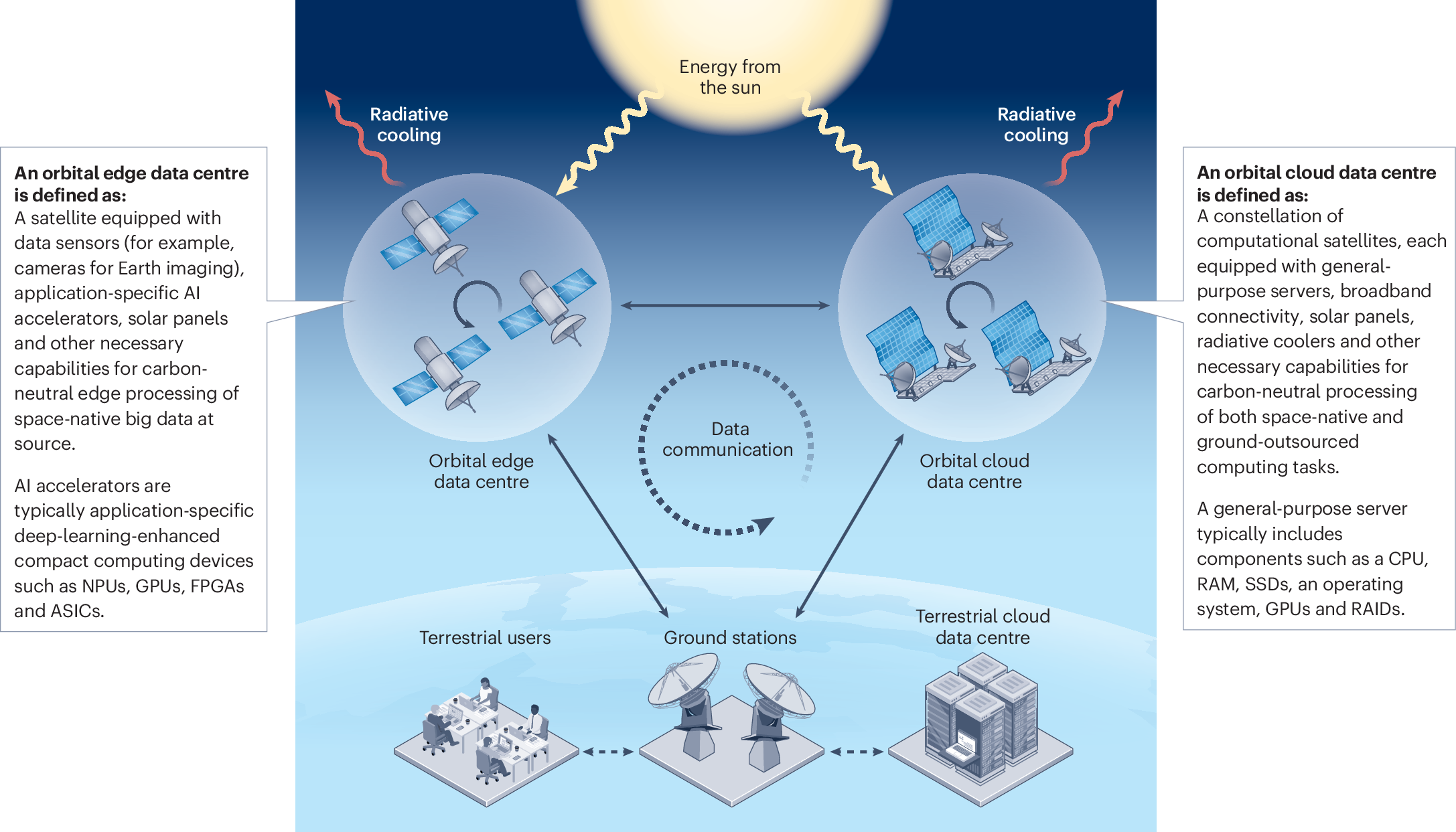

The concept isn't entirely new. Mass drivers and electromagnetic catapults have existed in theoretical physics for decades. What makes Musk's plan noteworthy is the context—it's not just about launching things. It's about building an orbiting AI data center powered by the sun and cooled by the vacuum of space. The satellites would theoretically provide distributed computing capacity for what Musk envisions as superintelligent AI systems. Whether this actually makes technical sense is another question entirely.

Let's dig into what this plan actually involves, why Musk thinks it's necessary, what the engineering challenges really look like, and why some experts are already shaking their heads.

TL; DR

- Moon Satellite Factory: Musk proposes building an AI satellite manufacturing facility on the lunar surface with a mass driver catapult for launch

- Mass Driver Technology: The launcher would need to achieve 3,800 mph escape velocity, requiring electromagnetic forces of 10,000+ g-force acceleration

- AI Data Center Vision: Satellites powered by solar energy and cooled by space vacuum would create a distributed computing network for advanced AI

- Timeline Reality Check: While Musk claims sub-10-year completion, the last human Moon landing was 1972—over 50 years ago

- Technical Feasibility: The concept is physically possible but requires solving multiple engineering problems, significant capital investment, and solving landing/construction challenges first

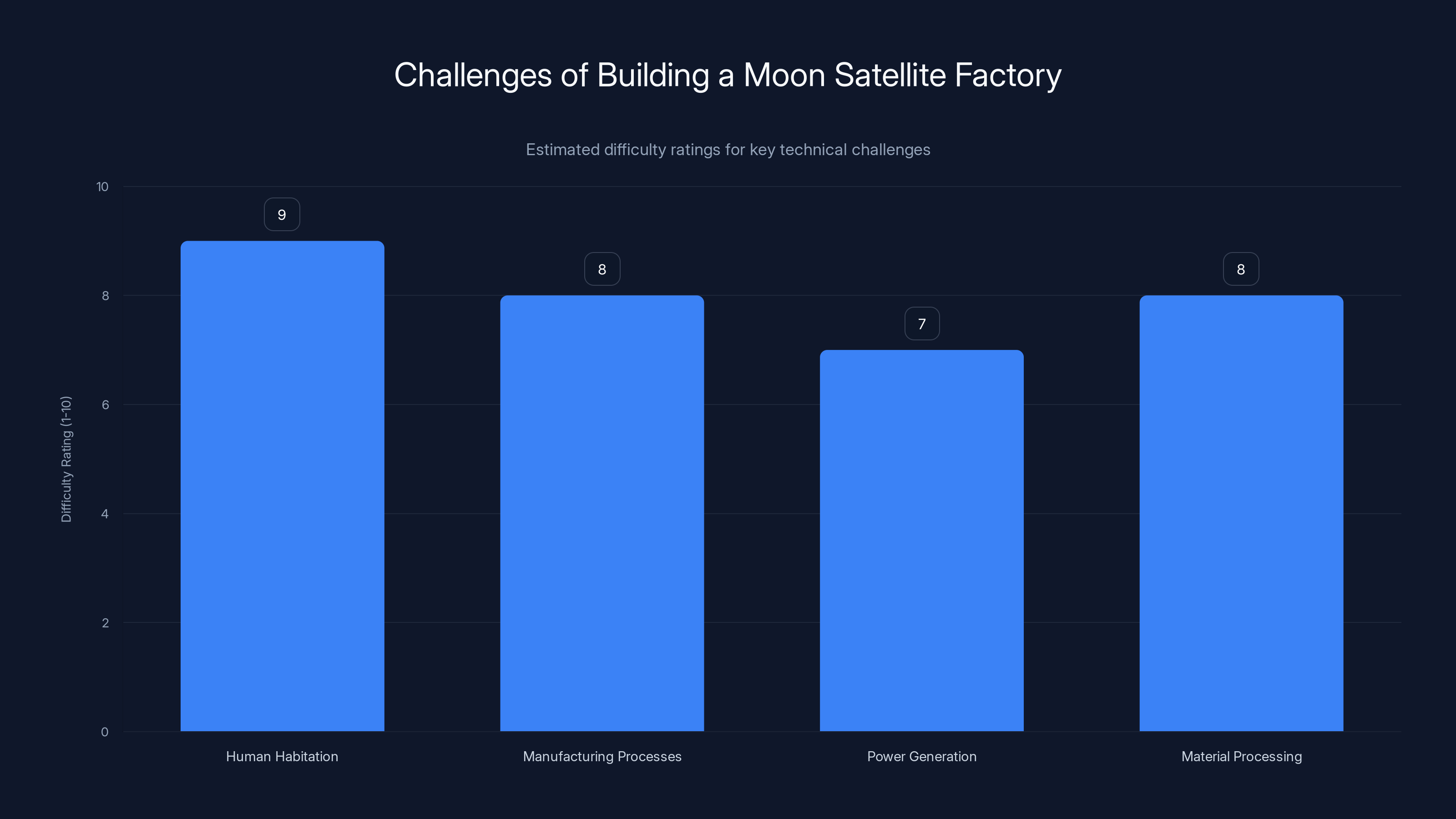

Human habitation poses the greatest challenge due to the need for life support and radiation protection. Estimated data.

The Core Vision: Why Musk Thinks the Moon is Necessary for AI

Understanding Musk's moon factory proposal requires stepping back and understanding his broader AI vision. According to remarks made during the x AI meeting, Musk believes creating truly advanced artificial intelligence requires unprecedented computing capacity. Not just more GPUs in a data center on Earth—but a fundamentally different approach to power generation, heat dissipation, and computational infrastructure.

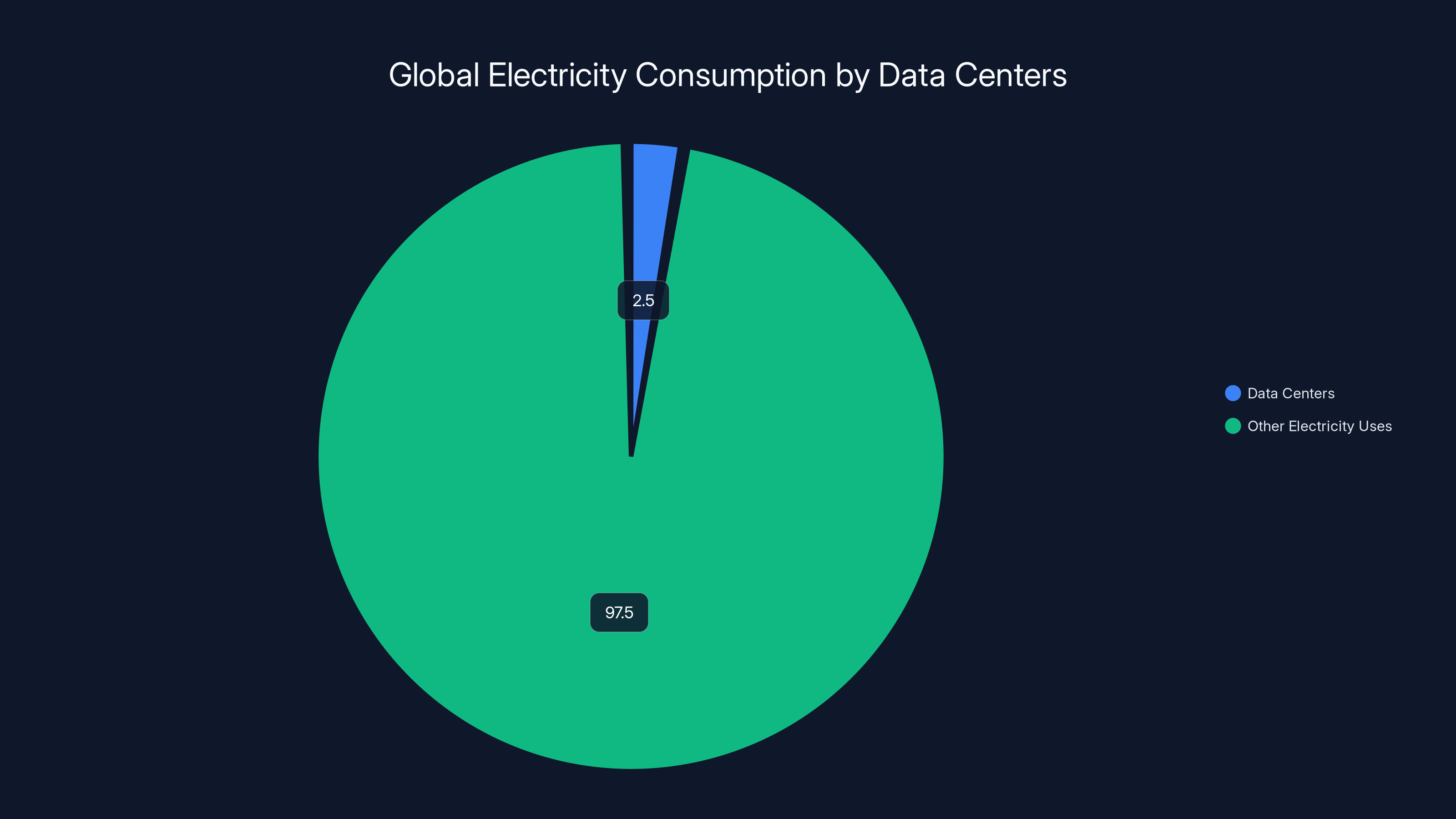

Earth-based data centers face inherent constraints. They require massive electrical infrastructure, cooling systems that consume enormous amounts of water, and they're limited by the physics of heat transfer in atmospheric conditions. Even the most efficient modern data centers waste significant energy as heat. The International Energy Agency estimates data centers consume between 2-3% of global electricity, and that number is climbing.

Musk's insight—and it's not entirely unreasonable—is that space offers advantages Earth can't provide. Satellites in orbit have access to continuous solar power without atmospheric interference. More importantly, they sit in the vacuum of space, where heat dissipation becomes trivial. A satellite can radiate waste heat directly into the cold vacuum, achieving cooling efficiency impossible on Earth.

The jump from "space-based computing is thermally efficient" to "we need a factory on the Moon making satellites" is where Musk's vision gets interesting. Why build on the Moon rather than just launching satellites from Earth? The answer relates to launch costs and manufacturing at scale.

Earth-to-orbit launch costs remain stubbornly expensive. Even with Space X's reusable Falcon 9 rockets, putting payload into orbit costs roughly

Musk told employees that "you have to go to the moon" to build the required AI capabilities, and described it as difficult to imagine what such intelligence would think about. This framing suggests he views lunar infrastructure not as a vanity project, but as foundational to achieving his AI ambitions.

What is a Mass Driver? The Physics Behind Lunar Catapults

A mass driver—sometimes called an electromagnetic catapult or rail gun—isn't science fiction anymore. It's physics that actually works, though building one on the Moon would be extraordinarily complex.

The fundamental principle is straightforward. An electrical current creates a magnetic field. That field interacts with a conducting object (the payload) and accelerates it. Increase the current, increase the magnetic field, and you increase the acceleration. Scale this up with a long track and you can achieve remarkable velocities.

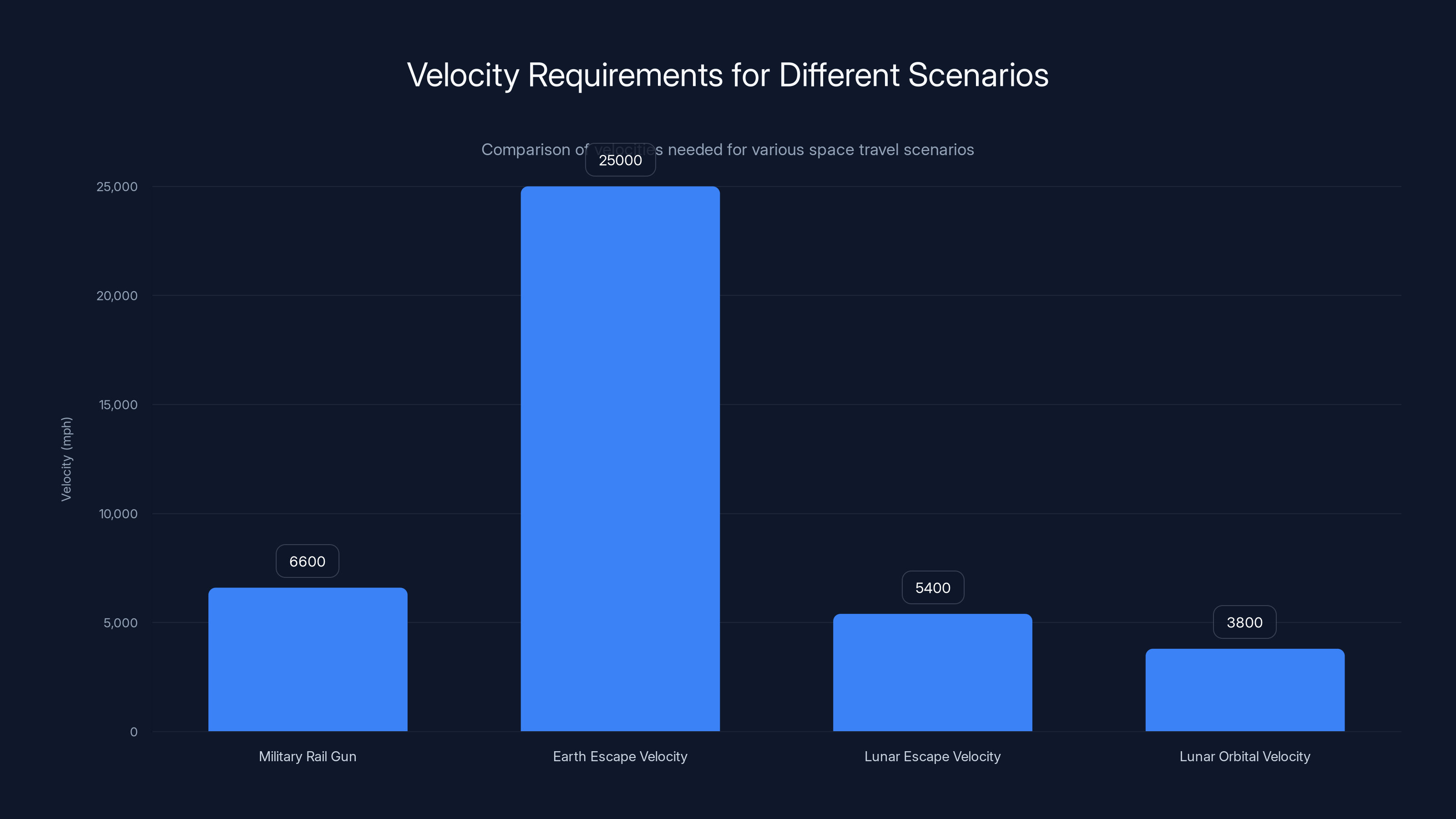

How remarkable? Military rail gun tests have achieved speeds around Mach 8.8 (roughly 6,600 mph at sea level). NASA and various defense agencies have experimented with electromagnetic rail gun technology for decades. The underlying physics works.

But here's where lunar dynamics matter. Earth has 9.8 meters per second squared of gravity. The Moon has 1.62 m/s² (one-sixth of Earth's). That's a massive advantage for launch systems.

To escape Earth's gravity from the surface, you need to achieve escape velocity: approximately 11.2 km/s or 25,000 mph. From the Moon's surface, escape velocity is only 2.4 km/s or roughly 5,400 mph. But Musk's plan isn't about escaping the Moon entirely—it's about achieving orbital velocity around the Moon.

Orbital velocity depends on the object's distance from the body's center of mass. For low lunar orbit (say, 100 km altitude), the required velocity is approximately 1.68 km/s or 3,750 to 3,800 mph. That's roughly five times the speed of sound.

Accelerating something from zero to 3,800 mph over a reasonable distance requires stunning acceleration forces. If we assume a 10 km (10,000 meter) launch track, the acceleration would be:

That's roughly 14.7 g-forces. That's survivable for equipment, though it would damage many sensitive electronics. Over a shorter track—say, 1 km—you'd experience 1,470 m/s², or 150 g-forces. That enters territory where even robust satellites would suffer structural damage.

Musk mentioned that satellites launched via mass driver would need to withstand acceleration forces around 10,000 g or more. That's not a typo—ten thousand times Earth's gravity. At that acceleration level, the satellite would need to be an incredibly strong structure, likely making it much heavier and reducing payload capacity.

Think about what this means practically. Your satellite isn't just any piece of equipment. It needs to survive extreme acceleration, radiation in space, thermal cycling, and years of operation. Every component—circuits, sensors, solar panels—must either be hardened against those forces or somehow isolated from them. That adds weight, complexity, and cost.

Furthermore, the power requirements for a mass driver are enormous. Generating the magnetic fields and electrical currents needed to accelerate multiple satellites daily would require substantial electrical infrastructure on the Moon. That means either nuclear reactors or enormous solar arrays. Both introduce their own engineering challenges in a lunar environment.

Data centers consume approximately 2-3% of global electricity, highlighting the significant energy demand of current computational infrastructure.

Lunar Manufacturing: Building a Factory on Another World

Before you can launch satellites via a mass driver on the Moon, you need to actually build the factory that manufactures those satellites. This is where the project moves from "theoretically possible" to "staggeringly difficult."

Lunar manufacturing isn't something we've ever done at scale. Humans set up temporary bases during Apollo missions in 1969-1972, but they were small camps designed for short-term stays. The longest stay was three days. You can't build a complex manufacturing facility that produces multiple satellites in three days.

For context, consider what a satellite factory needs. First, there's the infrastructure. Climate-controlled cleanroom environment? On the Moon, you need to create pressurized habitats and maintain life support. Precision tooling and manufacturing equipment? Everything runs differently in lunar gravity. Materials sourcing? You could theoretically use lunar regolith (Moon dust and soil), but processing it into usable materials requires technology we haven't developed yet.

Second, there's the human factor. You need skilled workers—engineers, technicians, quality control specialists. You need to transport them to the Moon, provide life support for years, manage their psychological and physical health at one-sixth Earth gravity. The radiation exposure is higher on the Moon than in orbit. The psychological stress of isolation in a hostile environment is severe. It's not like opening a factory in a remote location on Earth.

Third, there's the supply chain complexity. A satellite factory requires raw materials, components, power, tools, and replacement parts. Earth is about three days away by spacecraft. If something breaks, you can't just order a replacement from Amazon. You need redundancy, spares, and the ability to manufacture or repair items locally.

Currently, all spacecraft components must be manufactured on Earth and launched to space. This includes not just the satellites themselves, but equipment for maintaining the factory. The logistics alone would be staggering.

There's also the question of who builds this factory. It's not something a single company can do alone. You'd need cooperation from multiple organizations, likely international. Space treaties get complex when you start talking about establishing permanent facilities on other celestial bodies. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prohibits national claims to celestial bodies, but it's unclear how it applies to commercial activities and permanent settlements.

Musk and Space X have expertise in rockets and spacecraft, but the organizational infrastructure to establish and operate a complex manufacturing facility on another world doesn't exist yet. It would need to be built from scratch, which means hiring experts, developing new procedures, and managing incomprehensibly complex logistics.

The Escape Velocity Problem: Can Lunar Satellites Actually Work?

Here's an assumption Musk's proposal might not have fully addressed: what happens to satellites launched from the Moon?

Musk said in the x AI meeting that "any satellites launched from the Moon would presumably orbit the Moon as well." Note that word: "presumably." It suggests even he wasn't entirely certain about the mechanics.

Launching from the Moon at 3,800 mph achieves lunar orbital velocity—satellites circle the Moon. But Space X's ultimate goal seems to be creating a network for Earth-based AI applications. Earth-orbit satellites are far more useful for most applications, being much closer to Earth and able to provide continuous coverage of Earth's surface.

To get a satellite from the Moon to Earth orbit, you'd need to achieve Earth escape velocity or at least put it into a trans-Earth trajectory. The physics gets complicated. You could launch from the Moon, transfer the satellite via space, and have it brake into Earth orbit. But that requires additional fuel and engines on the satellite itself—adding weight and complexity.

Alternatively, satellites launched from the Moon could theoretically be transferred to Earth orbit using lunar-based fuel depots. But that requires developing fuel production on the Moon, another unsolved problem.

Or—and this might be the actual intention—maybe Musk plans to build the entire AI data center network in lunar orbit rather than Earth orbit. That would avoid the transfer problem entirely. But lunar orbit is less useful for communications and sensing applications compared to Earth orbit. It's a trade-off with significant engineering implications.

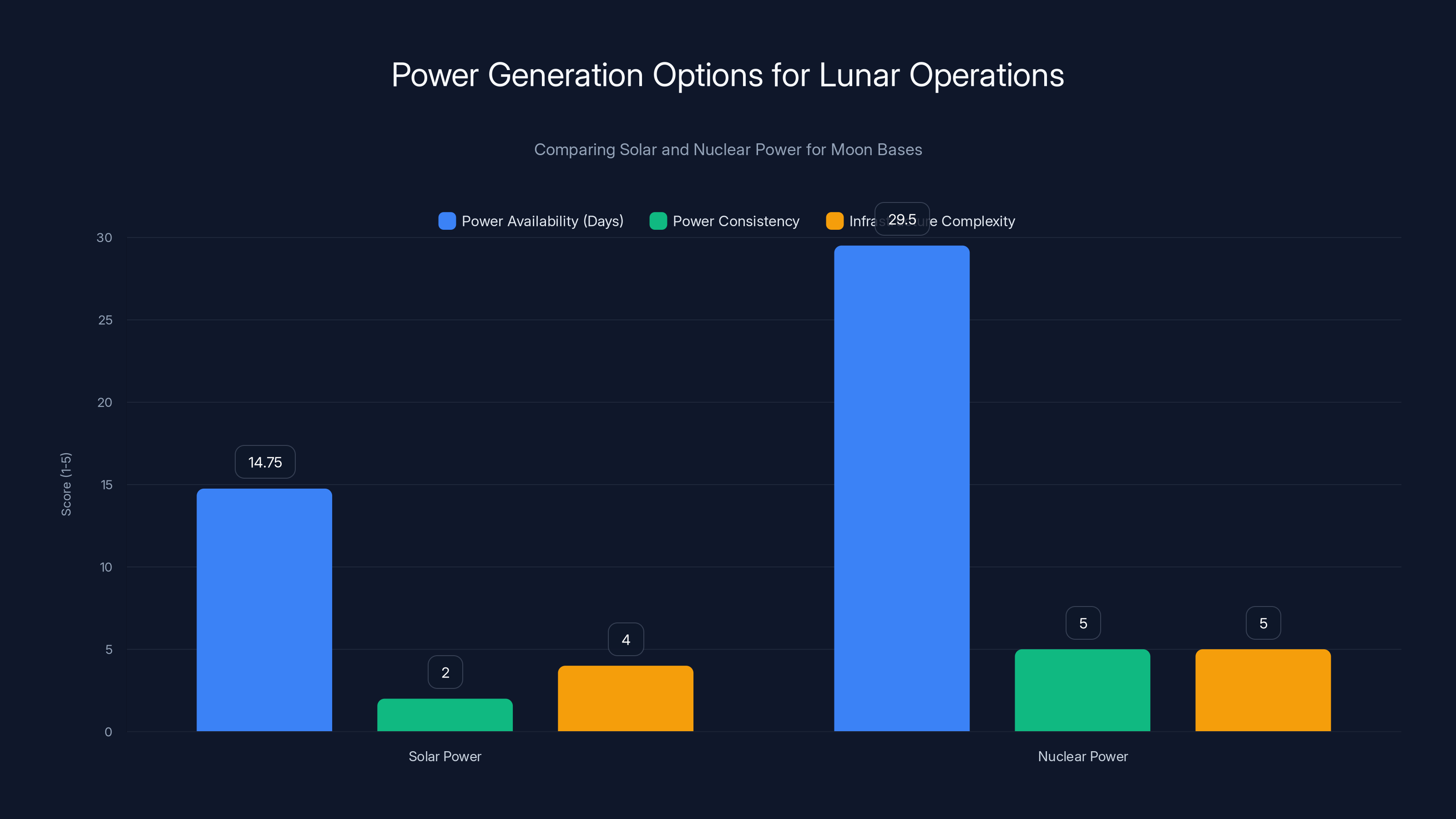

Power Generation on the Moon: The Solar and Nuclear Question

Musk's vision includes AI satellites powered by the sun. Solar power works in space because there's no atmospheric interference. A satellite in high orbit receives solar energy essentially unobstructed. But on the Moon, the situation is more complex.

First, there's the lunar day/night cycle. A lunar day lasts about 29.5 Earth days. That means 14.75 days of sunlight followed by 14.75 days of darkness. During the lunar night, solar panels produce zero power. So you'd either need enormous battery systems to store power through the lunar night, or you'd need to position your factory and mass driver in areas that receive nearly continuous sunlight.

Luckily, such areas exist. The lunar poles have terrain that receives nearly perpetual sunlight. The rim of craters near the poles stays illuminated for months at a time, perfect for solar installations. But building in these locations presents additional challenges—they're remote, difficult to access, and terrain is rough.

Alternatively, the factory could use nuclear power. A nuclear reactor on the Moon would provide continuous power regardless of the day/night cycle. Several space agencies have explored nuclear power for Moon bases. But transporting a nuclear reactor to the Moon involves complex political and safety considerations. One launch failure would scatter radioactive material across the lunar surface.

Second, there's the power infrastructure. The mass driver needs enormous electrical power to operate. Accelerating a satellite to 3,800 mph requires depositing huge amounts of energy into the payload. If the satellite weighs 1,000 kg, achieving that velocity requires:

That's 402 kilowatt-hours per satellite. If the mass driver operates with 80% efficiency (generous estimate), you're consuming about 500 k Wh per launch. Launch ten satellites per day and you're drawing 5,000 k Wh per lunar day. That requires megawatt-scale power infrastructure on the Moon.

Solar panels have limited power density—roughly 150-200 watts per square meter in space. To generate 5 megawatts, you'd need about 25,000 to 33,000 square meters of solar panels. That's a solar farm covering several acres on the lunar surface. Dust and radiation degrade solar panels, requiring regular maintenance and replacement.

Approaches 1-4 offer high feasibility and lower costs compared to the Moon Factory, which is costly and has uncertain feasibility. Estimated data.

The Cooling Problem: Why Space-Based Computing Needs Better Thermal Management

Musk's proposal emphasizes that satellites cooled by space's vacuum would solve data center heat dissipation problems. There's genuine insight here, but the reality is messier than it sounds.

In the vacuum of space, there's no air to conduct heat away. Traditional cooling—blowing air over a heat sink—doesn't work. Instead, heat transfer happens through radiation. All objects emit electromagnetic radiation as a function of their temperature. The Stefan-Boltzmann law describes this:

Where P is radiated power, σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, A is surface area, and T is absolute temperature. The key insight is the T^4 dependency—temperature has a huge effect on radiation. Double the absolute temperature and you radiate 16 times more power.

So a satellite at a high temperature radiates more waste heat into space. Sounds great, until you consider practical constraints.

First, electronics generate a lot of heat. A typical data center consumes 1-2 watts per gigabyte of storage. More computationally intensive systems consume far more. A megawatt data center produces megawatts of waste heat. For a satellite to radiate that much power, it either needs to be massive (huge surface area) or incredibly hot. Semiconductors function poorly at extreme temperatures—they fail when they get too hot.

Second, radiation cooling is omnidirectional. You radiate heat in all directions equally. On Earth, you can point heat toward the ground or sky selectively. In space, you lose heat in all directions. Some of that heat goes toward heating the satellite structure itself, creating temperature gradients that damage components.

Third, the satellite is simultaneously absorbing solar radiation. During the sunlit portion of its orbit, the satellite absorbs hundreds of watts per square meter of solar energy. It must radiate away both its internal heat and the absorbed solar energy. That requires careful thermal design—insulation in some areas, radiators in others.

The Timeline Problem: What Musk Said vs. What's Realistic

Musk claims Space X could complete a self-growing lunar city and satellite factory in less than a decade. Given his track record with timelines, this deserves skepticism.

Consider the evidence. In 2017, Musk stated that Space X would send cargo missions to Mars by 2022 aboard the fully reusable Starship. As of early 2025, Space X has performed multiple uncrewed test flights, but hasn't yet landed cargo on Mars. That's a miss of at least 2-3 years for a project that's within Space X's core competency.

For the Moon factory, the timeline would need to include several phases:

- Lunar Orbit Development: Landing, refueling, cargo transfer in lunar orbit. This is perhaps 2-3 years away, assuming aggressive Starship development.

- Lunar Surface Infrastructure: Establishing power systems, habitats, basic manufacturing equipment. Realistically 3-4 years, maybe more.

- Factory Construction and Testing: Building the actual satellite manufacturing facility and testing its processes. 2-3 years minimum.

- Mass Driver Development: Designing, building, and testing the electromagnetic catapult system. Unknown timeline—this technology hasn't been deployed at scale anywhere.

- Integrated Operations: Getting the entire system operating as designed, with reliable satellite production and launching. 1-2 years.

Adding these up, you're looking at 11-17 years under optimistic assumptions. More realistically, given the unprecedented nature of the work, 15-20 years is plausible. That assumes no major technical setbacks, which is almost never the case with new technology.

Compare Musk's timeline to historical precedent. The original Apollo program took about a decade from Kennedy's 1961 commitment to the 1969 Moon landing, but with vast resources and national urgency. Even so, it came close to missing the deadline. A return to the Moon with permanent infrastructure would be similarly or more complex, and driven by one company rather than a national program.

Competing Approaches: Why Earth-Based Alternatives Might Win

While Musk is planning a Moon factory, other organizations are pursuing different approaches to the same problems—distributed computing, efficient cooling, and reducing energy consumption.

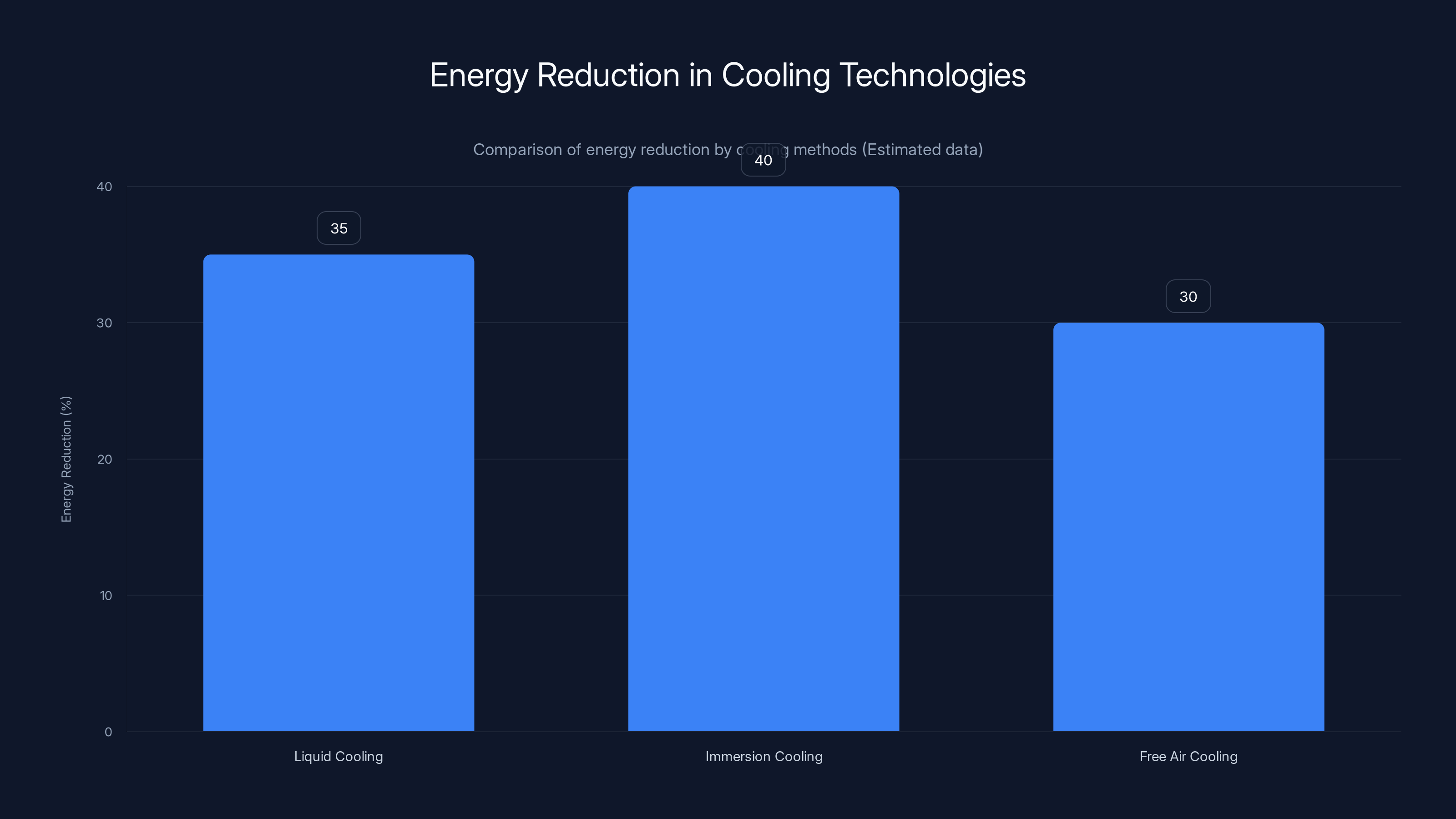

On the cooling front, data center operators are experimenting with liquid cooling, immersion cooling, and free air cooling in cooler climates. Google, Microsoft, and others have invested billions in these technologies. They're showing impressive results—30-40% energy reduction in some cases—and they don't require leaving Earth.

On the distributed computing front, edge computing is already happening. Rather than centralizing all computation in one place, companies distribute it across multiple locations closer to users. This reduces latency and distributes heat generation. It's less elegant than Musk's space-based vision, but it works and doesn't require lunar infrastructure.

On cost and feasibility, alternative AI approaches—better algorithms, more efficient training methods—might achieve similar computational capability improvements without new hardware. Anthropic and others are showing that clever software can sometimes replace brute-force hardware.

That doesn't mean Musk's Moon factory is impossible—it might eventually be viable and valuable. But there's a decent chance that by the time it's operational (2030s or 2040s), Earth-based alternatives will have already solved the problems it's designed to address.

Solar power offers intermittent availability due to the lunar day/night cycle, while nuclear power provides continuous energy. However, both options face significant infrastructure challenges.

Expert Skepticism: What Space Specialists Say About the Plan

Astronauts, engineers, and space policy experts have varied reactions to Musk's Moon factory concept. Most acknowledge the audacity while questioning the practicality.

The skepticism centers on several points. First, the technology required to establish permanent manufacturing on another world doesn't exist yet. This isn't a timeline problem—it's a fundamental engineering problem. We don't have reliable life support systems for long-duration lunar habitation. We don't have technology for extracting and processing lunar resources at scale. We don't have a proven method for maintaining precision manufacturing equipment on the Moon.

Second, the economics are questionable. Even if you could manufacture satellites on the Moon, would it cost less than manufacturing on Earth and launching them via rocket? The initial infrastructure cost would be enormous. You'd need to amortize that across thousands of satellites to make the economics work. And that's before accounting for the increased complexity of manufacturing in a harsh environment.

Third, the problem of getting from the Moon to where the satellites need to be—presumably Earth orbit or Earth itself—remains unsolved. The Moon-to-Earth transfer requires either additional fuel carried on the satellite or some kind of depot system. Both add cost and complexity.

Some experts note that a more pragmatic first step would be establishing a refueling depot in Earth orbit, allowing rockets to make multiple trips without returning to Earth for refueling. That's expensive but vastly simpler than a Moon factory. Space X is actually pursuing this approach for human Mars missions.

Others suggest that space-based manufacturing makes more sense beginning in Earth orbit rather than on the Moon. Orbital platforms can be continuously resupplied from Earth. They don't require solving planetary surface exploration problems. And they're much closer to where the satellites would actually be used.

The Materials Science Challenge: Can We Build This?

Even if you solve the engineering problems—power systems, thermal management, manufacturing processes—you face an enormous materials science challenge.

The Moon is an extreme environment. Surface temperatures swing from 250°F in sunlight to -250°F in shadow. Solar radiation is intense without atmospheric filtering, including dangerous ultraviolet and cosmic rays. The electrical charge on lunar dust creates its own problems. Vacuum causes outgassing of materials—compounds evaporate from metals and polymers at rates they wouldn't on Earth.

For a manufacturing facility, you need materials that remain stable under these conditions. A solar panel needs materials that won't degrade under intense UV and radiation. A mechanical bearing needs lubricants that won't evaporate. Seals need to remain flexible at temperature extremes.

Much of this can be solved through careful material selection and design, but it adds cost and development time. You can't just ship Earth-normal equipment to the Moon. Every component needs validation in lunar conditions.

For the mass driver itself, you face an additional challenge. The electromagnetic field strength needed to accelerate satellites creates immense stress. The conducting track experiences compression and tension forces. The magnetic coils need to withstand enormous currents. Materials science meets extreme engineering. Failures would be catastrophic—a mass driver malfunction could destroy the satellite and damage the facility.

One approach is to build with materials found on the Moon. Lunar regolith contains useful elements. But processing regolith into usable materials—metals, ceramics, semiconductors—requires technology we haven't developed. It's theoretically possible but represents another massive engineering challenge.

Comparison to Alternative Approaches: Moon Factory vs. Other Strategies

To put the Moon factory in perspective, consider how it compares to other approaches for achieving Musk's goals.

Approach 1: Earth-Based Data Centers with Better Cooling Advancements in liquid cooling, immersion cooling, and free air cooling could reduce data center energy consumption by 30-50%. Cost to develop: billions. Timeline: 3-5 years. Feasibility: High (already in progress).

Approach 2: Orbiting Data Centers in Earth Orbit Launch data centers into Earth orbit for radiation cooling. Resupply from Earth. Cost: Very high but lower than Moon factory. Timeline: 5-10 years. Feasibility: Higher than Moon factory, but still challenging.

Approach 3: Algorithm Optimization Invest heavily in more efficient AI algorithms and training methods. Potentially 2-10x efficiency improvements. Cost: Lower than infrastructure approaches. Timeline: Ongoing, results in 2-5 years. Feasibility: High (AI research already happening).

Approach 4: Specialized Hardware Build custom silicon designed for AI workloads rather than general-purpose processors. 2-5x efficiency improvements. Cost: Billions but lower than Moon factory. Timeline: 3-5 years. Feasibility: Very high (companies already doing this).

Approach 5: Moon Factory Establish manufacturing on the Moon's surface. Cost: Hundreds of billions, possibly trillions. Timeline: 15-25 years. Feasibility: Uncertain (unprecedented technology and engineering).

From a strategic perspective, Approaches 1-4 provide significant improvements with much lower risk and cost. The Moon factory (Approach 5) might eventually be valuable, but later, not sooner.

Cooling technologies like immersion cooling and liquid cooling can reduce energy consumption by 30-40%, offering Earth-based solutions to data center challenges. Estimated data.

The Vision Behind the Plan: What Musk Actually Wants to Accomplish

Steppin back from the technical details, what's Musk's underlying motivation?

Musk has publicly stated concerns about artificial intelligence safety and capabilities. He co-founded Open AI partly because he believed AI research shouldn't be dominated by any single company or profit motive. His creation of x AI suggests he wants to pursue AI development independently.

The Moon factory proposal can be understood as part of this broader strategy. If you're going to build superintelligent AI, you want computational infrastructure that's under your control, independent from traditional power grids and supply chains. A space-based network would be genuinely independent in a way Earth-based infrastructure can't be.

There's also an element of thinking long-term and grand-scale. Musk has consistently positioned himself as someone willing to pursue goals others consider impossible. Mars colonization, electric vehicles at scale, reusable rockets—these were all dismissed as impractical before he made them his focus. The Moon factory fits this pattern.

Moreover, the idea of manufacturing in space taps into a genuine long-term opportunity. Resources are limited on Earth. Building infrastructure in space could eventually be hugely valuable. Even if the Moon factory specifically doesn't work out, developing the technology to manufacture and construct in space is strategically important for long-term human expansion.

Regulatory and Legal Challenges: Who Gets to Build on the Moon?

Beyond engineering, the Moon factory faces a legal and regulatory maze.

The Outer Space Treaty, signed by over 100 countries, explicitly prohibits any nation or national space agency from claiming territory on the Moon or other celestial bodies. The treaty states that "the moon and other celestial bodies... are the province of all mankind."

But what about private companies? The treaty doesn't explicitly address commercial activities. It requires that nations authorize and supervise national space activities, whether governmental or private. So Space X couldn't build a Moon factory without authorization from the United States government.

That authorization wouldn't be unreasonable to obtain—the US has been moving toward supporting commercial space activity for years. But it does require government approval and potentially international coordination.

There's also the question of permanent settlements and extraction of resources. If Space X extracts lunar materials for use in manufacturing, does that constitute exploitation of a common resource? International debates are ongoing about whether the Outer Space Treaty allows commercial resource extraction on the Moon.

China and Russia have different interpretations of these treaties. There's genuine uncertainty about whether a US company could build a large facility on the Moon without diplomatic complications. If the technology worked out but diplomacy failed, the whole project would be blocked.

The Broader AI Arms Race Context

Understanding Musk's Moon factory proposal requires appreciating the broader context of competition in AI development.

Open AI, led by Sam Altman, is pursuing increasingly larger AI models. Anthropic is advancing constitutional AI approaches. Google, Microsoft, and others are all investing heavily. There's a genuine arms race dynamic—whoever develops advanced general intelligence first might gain enormous strategic advantage.

In this context, Musk's Moon factory becomes comprehensible as a bid to ensure x AI has unique computational advantages. If other AI companies are limited by Earth-based power and cooling, and x AI has access to space-based computing infrastructure, that's a significant edge.

Of course, this assumes the Moon factory actually works and becomes practical before alternatives solve the same problems. It's a risky bet—invest enormous resources in extremely speculative technology in hopes of gaining advantage in an uncertain future timeline.

This chart compares the velocities required for military rail gun tests, escaping Earth's gravity, escaping the Moon's gravity, and achieving lunar orbit. Notably, achieving lunar orbit requires significantly less velocity than escaping Earth's gravity.

Timeline Reality Check: Historical Precedent for Mega-Projects

Let's ground Musk's timeline claims in historical reality.

Approaching this objectively, how long have other mega-projects taken?

Interstate Highway System: Planned 1956, substantially completed 1991 (35 years), still has ongoing projects.

International Space Station: Development began 1984, first modules launched 1998, substantially complete 2011 (27 years), still operating.

Large Hadron Collider: Proposed 1984, construction began 1998, operational 2008 (24 years).

Three Gorges Dam: Proposed 1919, construction began 1994, operational 2008 (89 years total, 14 years construction).

Large projects consistently take longer than initial estimates. The best predictor of actual timeline is usually 1.5-2x the original estimate.

For the Moon factory, Musk estimated under 10 years. Historical precedent suggests 15-20 years is more realistic, and that's without major technical setbacks.

Lessons from Past Failed Predictions

Musk's track record on timelines deserves direct examination.

2017 Prediction: Space X would send cargo to Mars aboard Starship by 2022. Actual status (2025): Starship is in active development, hasn't reached orbit around Mars yet. Miss: 3+ years.

2013 Prediction: Space X would send humans to Mars by 2026. Actual status (2025): Space X is developing the technology, likely 5-10+ years away. Miss: 5+ years.

2016 Prediction: Tesla would produce 500,000 vehicles per year by 2018. Actual status (2025): Tesla produces around 1.8 million annually now, but took until 2024 to approach that volume. Miss: 6+ years.

2014 Prediction: Hyperloop would be built and operational by 2020. Actual status (2025): Hyperloop remains in testing phase with no operational routes. Miss: 5+ years.

The pattern is consistent: Musk's initial timelines are typically optimistic by 50-200%. When he estimates under 10 years for something unprecedented, expect 15-25 years or longer.

How This Could Actually Happen: A More Realistic Scenario

Despite the skepticism, a Moon factory isn't impossible. What would a more realistic path look like?

First, establish proven lunar landing and return capability. Space X needs to demonstrate multiple successful cargo deliveries to the Moon surface and recovery. This might take 3-4 years with aggressive development.

Second, establish small-scale habitation. Use the factories and habitats from previous deliveries to build a permanent presence. This phase might take 2-3 years, with small teams doing 6-month rotations.

Third, test manufacturing processes on a small scale. Don't try to build satellites immediately. Start with simpler products—spare parts, tools, test materials. See what works, what fails, and what needs to be redesigned. This phase might take 2-3 years.

Fourth, develop and test the mass driver system. Build it incrementally, test with increasing payloads, validate the concept. This alone might take 3-4 years—it's completely novel technology.

Fifth, scale up satellite manufacturing and launch operations. Once you've proven the concept on small scale, begin producing actual satellites. This is another 2-3 year phase to reach reliable operations.

Total realistic timeline: 12-18 years, possibly longer if any phase hits major obstacles.

During this timeline, Earth-based alternatives would continue improving. The advantage the Moon factory provides might shrink even as it's being built.

Why This Matters: The Bigger Picture

Whether or not the Moon factory is built, the proposal matters because it reveals Musk's thinking about long-term infrastructure and AI's computational needs.

It suggests that even with current and near-future Earth-based improvements, he believes superintelligent AI will eventually require computational infrastructure of an entirely different scale and location. That's a provocative claim that deserves serious consideration.

It also demonstrates how far outside normal engineering bounds some proposed solutions to technological challenges can be. For many problems, the best solution is a straightforward improvement to existing approaches. But for truly big challenges—creating artificial superintelligence, ensuring humanity is multiplanetary, solving energy scarcity—sometimes existing approaches have hard limits. That's when truly novel infrastructure becomes necessary.

Finally, the Moon factory proposal showcases the peculiar power of visionary thinking in technology. Most innovations are incremental improvements to existing systems. But occasionally, someone proposes something so ambitious and different that it reframes the entire conversation. Space X's reusable rockets seemed impossible until they worked. Electric vehicles seemed impractical until Tesla made them desirable. Lunar manufacturing seemed ridiculous until someone thoughtfully explained why it might matter.

FAQ

What exactly is a mass driver and how would it launch satellites from the Moon?

A mass driver is an electromagnetic catapult system that uses magnetic fields to accelerate payloads along a track to extremely high velocities. On the Moon, a mass driver would use electrical currents to create magnetic fields that interact with a conducting satellite, accelerating it to approximately 3,800 mph—the orbital velocity needed to orbit the Moon. The technology has been tested in military applications (rail guns reaching Mach 8.8 speeds), but deploying it on the Moon presents unprecedented engineering challenges including extreme power requirements, thermal management, and payload hardening to withstand 10,000+ g-force accelerations.

Why would Elon Musk want to build a satellite factory on the Moon instead of on Earth?

Musk's reasoning focuses on three advantages: First, the Moon's lower gravity (one-sixth of Earth's) reduces launch costs compared to Earth-to-orbit delivery. Second, space-based satellites offer superior thermal cooling through radiation into the vacuum rather than relying on atmospheric or liquid cooling. Third, a self-contained orbital AI data center would be independent from Earth's power grids and supply chains, providing strategic autonomy for AI development. However, these advantages must be weighed against enormous infrastructure costs and the uncertainty that Earth-based alternatives won't solve the same problems more cheaply and quickly.

What are the biggest technical challenges in building a Moon satellite factory?

The primary challenges include establishing stable, long-term human habitation on the Moon (life support, radiation protection, psychological factors), developing manufacturing processes that work in one-sixth gravity and lunar vacuum conditions, creating reliable power generation (either massive solar arrays or nuclear reactors), extracting and processing lunar materials into usable manufacturing materials, building and testing the mass driver catapult system itself (entirely novel technology), transporting all equipment and supplies from Earth at enormous cost, and solving the logistics of maintaining manufacturing equipment in an extremely harsh environment far from resupply sources. Each challenge represents years of development; combined, they represent arguably the most complex engineering project ever conceived.

Is Musk's 10-year timeline realistic for completing a lunar satellite factory?

No—historical precedent suggests Musk's timelines are typically optimistic by 50-200%. The Apollo program took a decade from presidential commitment to Moon landing, and that was with vast government resources and national urgency. A return to the Moon with permanent manufacturing infrastructure would be similarly or more complex. Realistic timeline estimates range from 15-25 years or longer, assuming no major technical setbacks. Musk's own track record supports this skepticism: his 2017 prediction of Mars cargo missions by 2022 missed by at least 3 years, and his 2013 prediction of humans on Mars by 2026 appears likely to miss by 5-10+ years.

Could satellites launched from the Moon actually reach Earth orbit, or would they be stuck orbiting the Moon?

This is an underexplored aspect of the proposal. Satellites launched from the Moon at orbital velocity would circle the Moon. To reach Earth orbit, they'd need additional fuel, velocity, or a transfer trajectory. Possible solutions include launching from the Moon to higher velocity for Earth transfer (adding fuel and weight), using lunar orbital refueling depots (requiring fuel production on the Moon), or building the entire AI data center in lunar orbit rather than Earth orbit. Musk's vague statement that satellites would "presumably" orbit the Moon suggests even he hadn't fully resolved this mechanical problem.

What makes space better for cooling data centers than Earth-based systems?

Space offers genuine thermal advantages because heat radiates directly into the vacuum without atmospheric interference. Data center waste heat radiates away much more efficiently than it can in Earth's atmosphere. However, the advantage is more modest than "infinite cooling"—well-designed space systems might achieve 2-3x better efficiency rather than orders of magnitude improvement. Space-based systems also absorb intense solar radiation, requiring careful thermal design. Additionally, the infrastructure costs and complexity of space-based data centers remain enormous, so the modest cooling efficiency gain must be weighed against vastly higher operational costs compared to Earth-based alternatives using improved liquid cooling or immersion cooling technologies.

Why hasn't this been done before if it's such a good idea?

The technology to build a Moon factory hasn't existed until very recently, and even now it's partially theoretical. Permanent human habitation on the Moon, resource extraction and processing, and manufacturing in vacuum at lunar scales have never been attempted. Additionally, Earth-based alternatives (better algorithms, specialized hardware, improved cooling techniques) have continually improved, reducing the competitive advantage of space-based infrastructure. The infrastructure costs remain staggering—likely hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars—making it impractical without either government backing (as with Apollo) or a private company with both capability and sufficient capital (like Space X). The convergence of Musk's vision, Space X's capabilities, and x AI's funding makes this more feasible now than at any previous time.

Could China or other space programs build a competing lunar factory?

China has expressed interest in Moon exploration and has successfully landed robotic missions. However, building a satellite manufacturing factory requires capabilities beyond landing rovers—sustainable habitation, large-scale construction, manufacturing in vacuum, power generation, and resource processing. No nation has demonstrated all these capabilities yet. The Outer Space Treaty complicates exclusive claims, requiring any factory to be authorized by national governments. Realistically, a lunar manufacturing facility would be a multi-decade, multi-billion-dollar project within reach of only a handful of nations or well-capitalized companies like Space X. Competition is likely but building competing facilities would take similar timelines, suggesting the first mover advantage might not be as large as Musk envisions.

How does this fit into Musk's broader Mars colonization vision?

The Moon factory appears to be part of a longer-term strategy to establish human presence beyond Earth. Mars colonization requires similar infrastructure—life support, manufacturing, in-situ resource utilization, and self-sufficiency. Building these capabilities on the Moon (which is much closer to Earth) provides a testing ground for technologies needed on Mars. The mass driver catapult and manufacturing processes developed for the Moon could potentially be adapted for Mars. Additionally, a lunar industrial base could eventually provide fuel or materials for Mars missions. From this perspective, the Moon factory is step one of a multi-decade program to establish humanity as a spacefaring civilization.

What if the technology works but the economics don't—could the Moon factory still be built?

Absolutely. Musk has demonstrated willingness to pursue technologically impressive goals even when economics are unclear. The early Tesla Roadster and Starship development both involved uncertain financial returns. If Musk views a Moon factory as strategically important for AI development or long-term human expansion, he might pursue it regardless of direct financial ROI. The $200+ billion wealth gives him resources for such bets. However, without compelling economics, broader investment and scaling become difficult. A factory that's technically possible but financially impractical serves as a technology demonstration more than a practical manufacturing solution.

The Bottom Line

Elon Musk's plan to build a satellite catapult factory on the Moon is simultaneously audacious, technically insightful, and realistically fraught with enormous challenges.

The core ideas aren't crazy. Electromagnetic catapults work. Space-based cooling is more efficient than Earth-based. The Moon has lower gravity than Earth, reducing some launch constraints. Building manufacturing infrastructure in space could eventually be valuable.

But the implementation remains wildly speculative. We haven't established permanent human presence on the Moon. We haven't built factories in space. We haven't tested mass drivers at the scale required. The infrastructure costs would be staggering, the timeline would likely stretch well beyond a decade, and Earth-based alternatives might solve the same problems more cheaply before the Moon facility becomes operational.

Musk's proposal matters not because it's likely to happen soon, but because it reveals serious thinking about long-term infrastructure needs. If superintelligent AI really does require computational capacity beyond what Earth can provide, then space-based solutions become necessary eventually. The Moon might not be the first location (Earth orbit is simpler), and the timeline might stretch to the 2030s or 2040s, but the underlying vision of space-based computing infrastructure might prove prescient.

For now, it remains an ambitious proposal that would require solving multiple unprecedented engineering challenges, securing government approval in a complex regulatory environment, and betting that space-based computing provides enough advantage to justify the enormous investment. Those are big ifs.

But they're not impossible ifs. And that's what makes Musk's Moon factory proposal genuinely interesting, even if it takes thirty years instead of ten.

Key Takeaways

- Musk's Moon satellite factory uses a mass driver (electromagnetic catapult) to launch AI satellites at 3,800 mph orbital velocity, exploiting the Moon's lower gravity and space's superior cooling

- The engineering challenges are immense: permanent habitation (never sustained), manufacturing in vacuum (untested), 5+ megawatt power generation, and entirely novel mass driver technology at scale

- Realistic timeline is 15-25 years minimum, not Musk's claimed sub-10 years; his track record shows timelines typically miss by 50-200%

- Earth-based alternatives (better algorithms, specialized AI hardware, liquid cooling, orbital data centers) might solve the same computational scaling problems for vastly lower cost before the Moon factory becomes operational

- The proposal reflects genuine long-term thinking about AI infrastructure limits and space-based manufacturing, even if this specific implementation faces formidable obstacles

Related Articles

- Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- xAI Founding Team Exodus: Why Half Are Leaving [2025]

- xAI Co-Founder Exodus: What Tony Wu's Departure Reveals About AI Leadership [2025]

- NLRB Drops SpaceX Case: What It Means for Worker Rights [2025]

- FCC Accused of Withholding DOGE Documents in Bad Faith [2025]

- Why Elon Musk Pivoted from Mars to the Moon: The Strategic Shift [2025]

![Elon Musk's Moon Satellite Catapult: The Lunar Factory Plan [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/elon-musk-s-moon-satellite-catapult-the-lunar-factory-plan-2/image-1-1770811757982.jpg)