The Space-Based AI Revolution That's Actually Happening

Last month, something that sounded like pure science fiction crossed a critical threshold into reality: orbital data centers. Not as a concept in a startup pitch deck, but as a formal filing with the Federal Communications Commission. Elon Musk, through SpaceX, officially proposed plans for a million-satellite data center network orbiting Earth. And unlike most audacious tech declarations that fade into obscurity, this one is gathering momentum at an alarming speed.

Here's the thing that makes this different from typical Musk hyperbole. The logic chain is actually coherent. His company SpaceX dominates commercial spaceflight. His AI company, x AI, desperately needs compute infrastructure. So last week, he merged them. Suddenly, the idea of launching data centers into orbit stopped sounding like a billionaire's fever dream and started looking like a potentially viable business strategy.

The timing matters too. Global data center spending is spiraling out of control. Tech giants are pouring hundreds of billions annually into ground-based infrastructure to feed their AI models. Power consumption alone is becoming a constraint. Data center electricity usage is doubling every few years. The real estate footprint is massive. Cooling requirements are astronomical—literally and figuratively. So when someone with the resources of SpaceX starts arguing that the economic math favors moving computation into space, suddenly people actually listen.

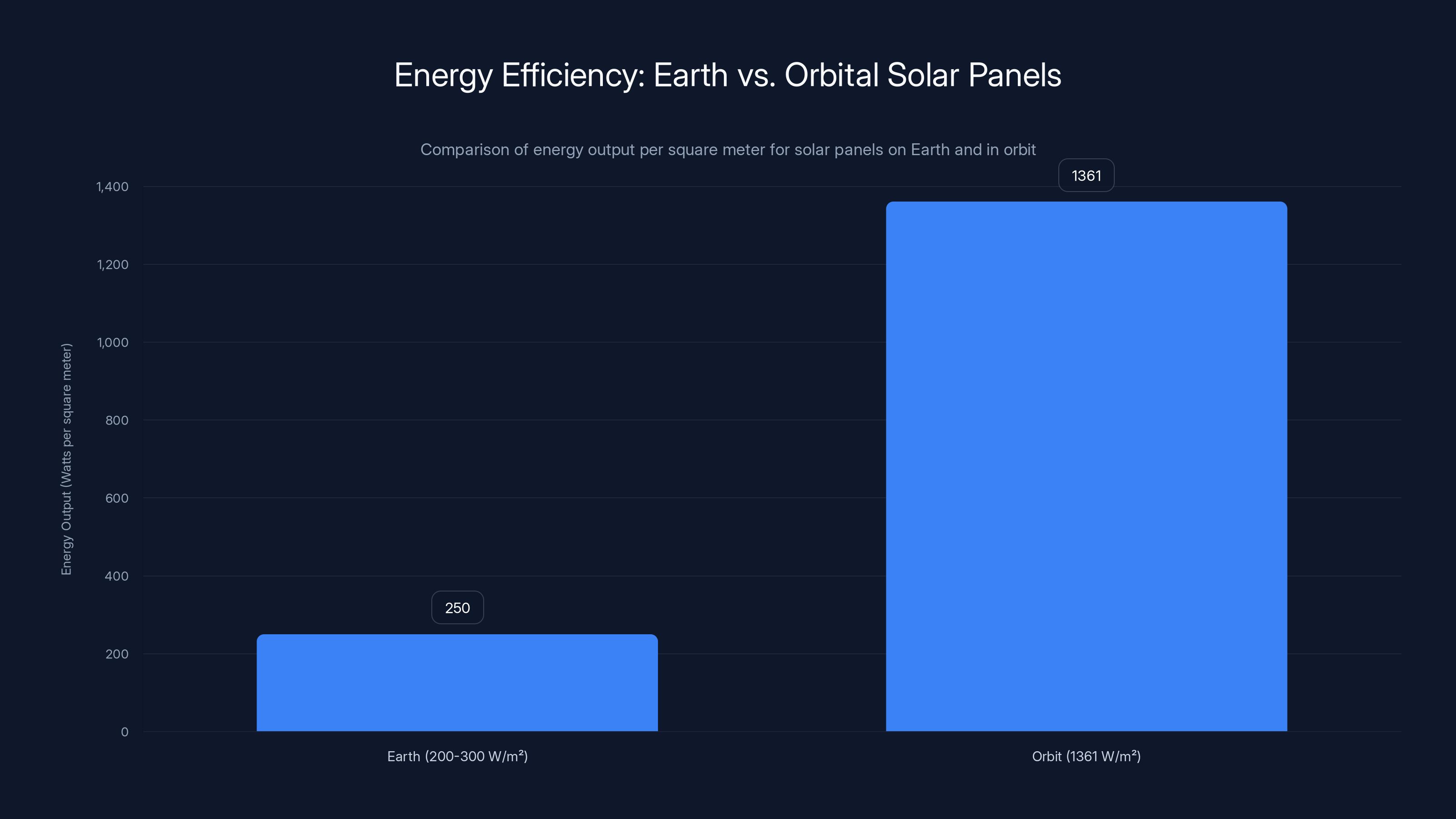

What's wild is that the argument isn't even that outlandish anymore. Solar panels in orbit receive unfiltered sunlight without atmospheric interference. That's genuinely five times more efficient than ground-based solar. That's not Musk speculation—that's physics. When you combine that with the plummeting cost of launching payload to orbit thanks to Falcon 9 reusability, the economics start shifting. Not completely yet. But shifting.

This isn't happening in a vacuum either. The FCC already accepted the filing. The regulatory path, normally glacial, is accelerating. Brendan Carr, the FCC chairman, publicly shared the proposal—an unusual gesture that signals political tailwind. The SpaceX-x AI IPO is coming soon, which means capital will flow. And Musk, in recent podcast appearances, has started laying out the full argument for anyone willing to listen.

Over the next few minutes, we're going to walk through what orbital data centers actually are, why the physics works, where the genuine obstacles remain, and what this could mean for the entire AI industry. Because if even a fraction of what Musk is claiming proves true, we're looking at the most fundamental reshaping of computing infrastructure since the cloud emerged twenty years ago. And unlike most industry shifts, this one could happen remarkably fast.

TL; DR

- SpaceX just filed FCC plans for a million-satellite orbital data center network, merging space launch capability with x AI's AI computing needs

- Solar panels produce 5x more power in space than on Earth, dramatically reducing the largest operating expense of traditional data centers

- Musk predicts orbital compute will be the "most economically compelling place" for AI by 2028-2030, with annual space-based AI capacity exceeding all Earth-based capacity by 2030

- The regulatory pathway is accelerating, with FCC chairman publicly backing the proposal and an IPO planned within months

- The real obstacles aren't physics—they're engineering challenges around GPU cooling, maintenance, and latency that require genuine innovation, not just wishful thinking

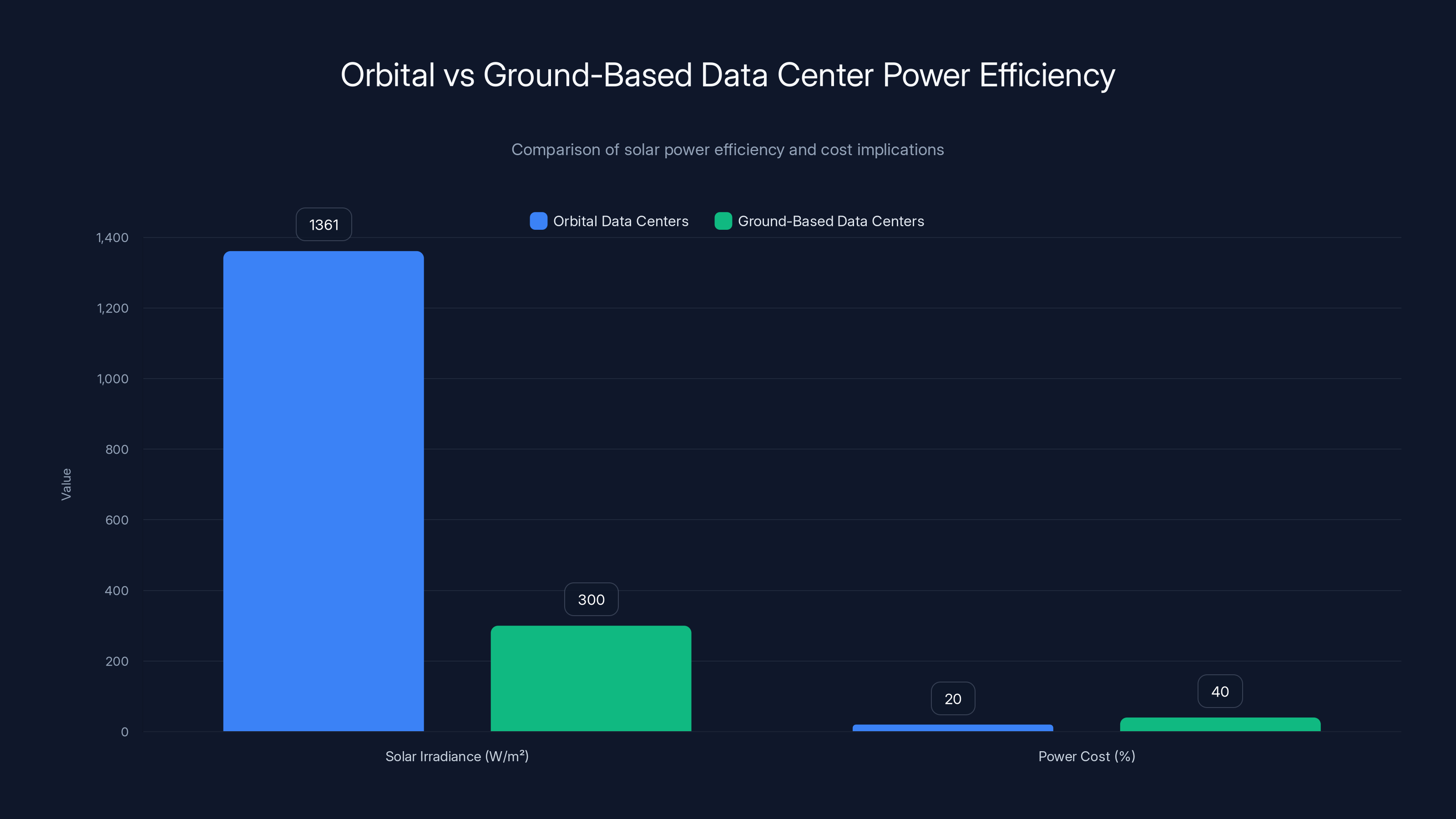

Orbital data centers receive 5x more solar power per square meter than ground-based centers, potentially reducing power costs significantly. Estimated data.

What Exactly Are Orbital Data Centers?

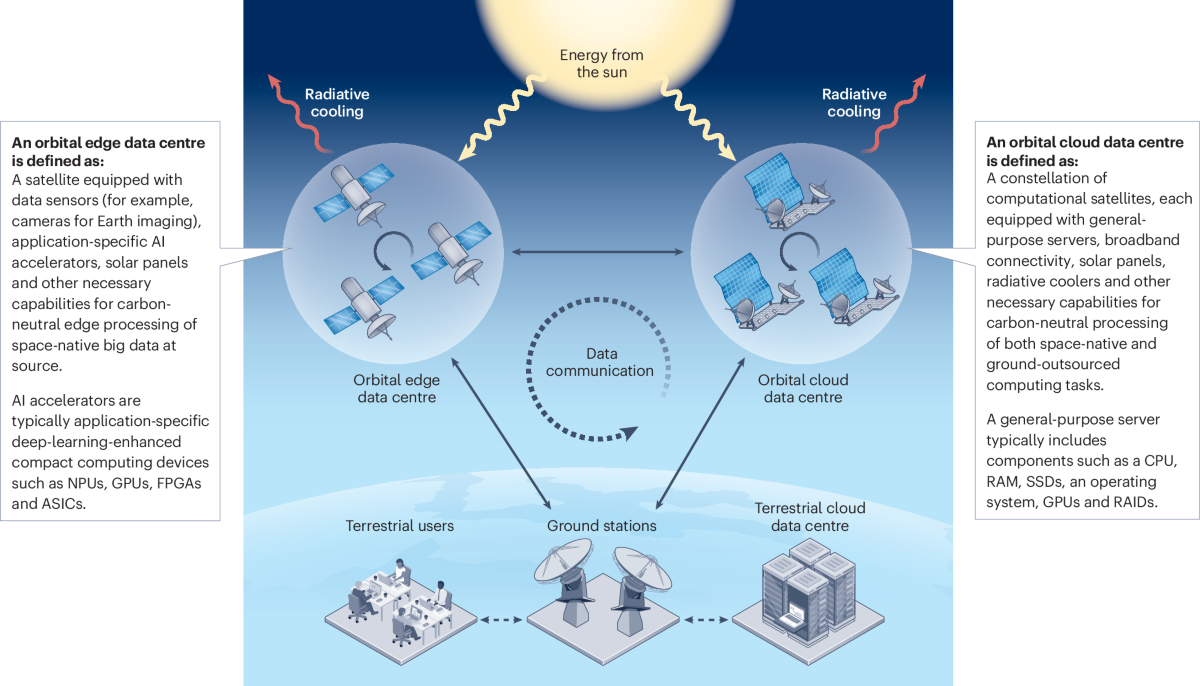

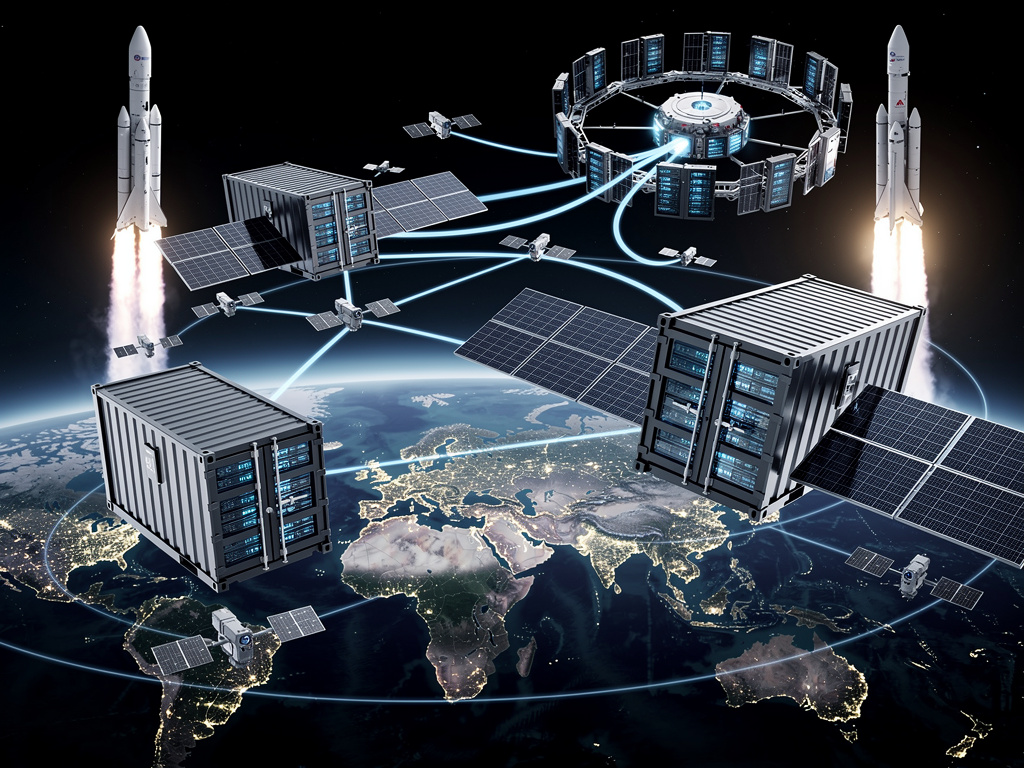

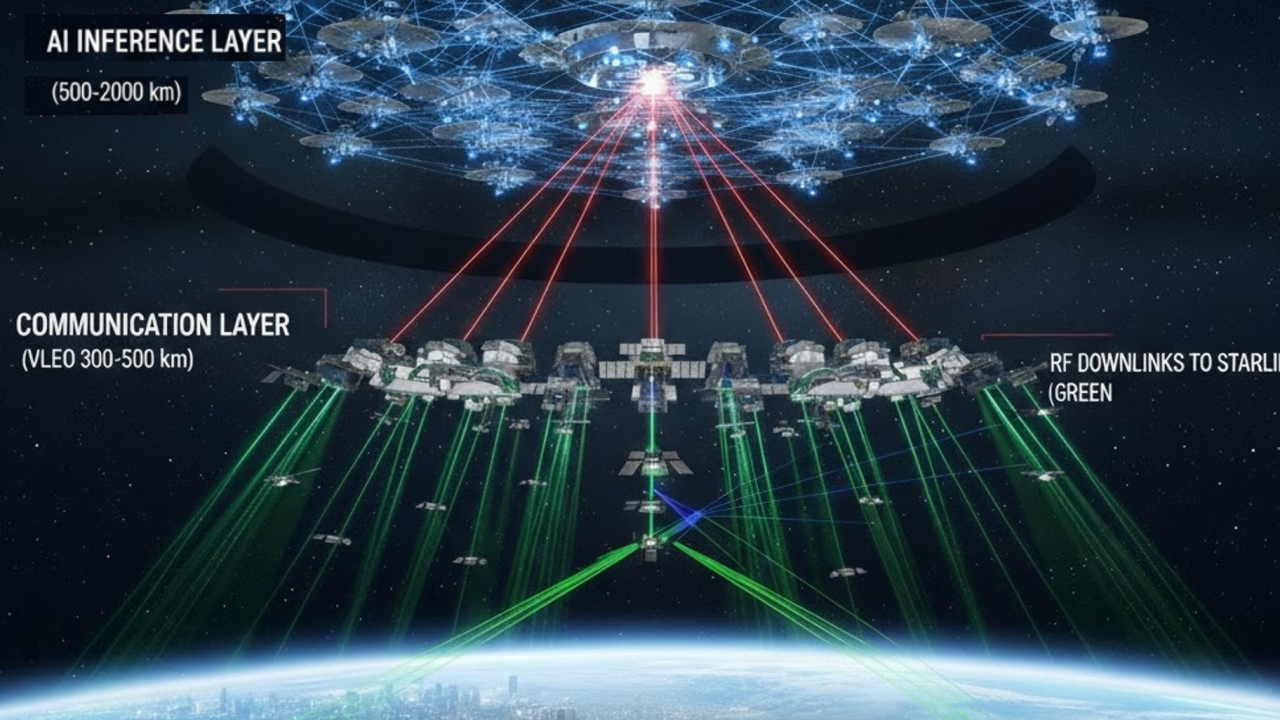

Before we get into the why, let's establish what we're actually talking about. An orbital data center isn't a single massive structure floating in space like some kind of Star Trek engineering section. Instead, imagine thousands of individual satellite units, each containing computing hardware, networked together through high-bandwidth laser links and radio frequencies. They form a distributed mesh network orbiting at a specific altitude, arranged so that coverage is continuous and latency is manageable.

The basic architecture would look something like this. You'd have individual satellite units, maybe the size of a shipping container, each packed with GPUs or custom AI chips. These satellites would be grouped in orbital clusters at specific inclinations to maintain coverage over target regions. They'd communicate with each other and with ground stations through laser inter-satellite links and millimeter-wave ground connections. The data flowing to and from these systems would be managed through a sophisticated network orchestration system, ensuring that computational load balances across the constellation.

Compare this to traditional terrestrial data centers. A ground-based facility occupies a fixed location. It has enormous physical footprint, requires cooling infrastructure, needs dedicated power generation and grid connections, demands real estate acquisition, and faces real estate taxes. It's stationary, which means geographical latency constraints—data traveling from Los Angeles to Virginia still travels at the speed of light with measurable delays.

Orbital compute changes these fundamental constraints. The satellite units can be manufactured in parallel and launched in batches. They operate in vacuum, eliminating cooling needs. They receive unobstructed solar energy. They're globally distributed by nature, reducing latency for users anywhere on Earth. They're not subject to terrestrial real estate constraints or power grid limitations. The only limiting factor becomes launch capacity and orbital real estate—both of which SpaceX controls or can control.

Now, this isn't entirely novel thinking. Researchers have theorized about space-based computing for decades. But the key difference in 2026 is that the enabling technologies have finally become practical. Falcon 9's reusability brought launch costs from

The satellite computing units themselves have also matured. Modern chips designed for edge computing are far more power-efficient than they were five years ago. Thermal management in vacuum has been solved by aerospace engineers. Inter-satellite laser links, once exotic, are becoming commodity components. The individual technologies that make orbital data centers possible have been proven. What Musk is proposing is combining them at unprecedented scale.

Orbital solar panels produce significantly more energy per square meter compared to Earth-based panels, offering a five to seven-fold increase in efficiency. Estimated data based on typical conditions.

The Economics: Why the Math Actually Works

Musk's core argument comes down to a deceptively simple equation. If solar panels produce five times more energy in space than on Earth, and power represents the largest operating expense in a data center, then orbital deployment should cost less per unit of compute. Let's actually work through whether this holds up.

Start with terrestrial data center economics. A modern AI training facility consumes between 100 to 500 megawatts depending on scale. The largest recent deployments run closer to 1 gigawatt. Power represents roughly 30 to 50 percent of total operating expenses. For a 500-megawatt facility, that's millions of dollars daily just in electricity costs.

Where does that power come from? Data centers typically locate near cheap power sources: hydroelectric regions, areas with natural gas, nuclear plants, or wherever electrical costs are lowest. Even with location optimization, they're paying for grid power. That power comes from aging infrastructure, transmission losses, regional variations, and market volatility. The average US data center electricity cost is around

Now consider orbital solar. A solar panel in orbit receives approximately 1,361 watts per square meter of sunlight intensity. On Earth's surface, that same panel receives maybe 200 to 300 watts per square meter after atmospheric losses and angle variations. That's a five to seven-fold efficiency difference, and it's not theoretical—it's just physics. The sunlight path through atmosphere reduces intensity. Clouds block it. Angle of incidence reduces it depending on latitude and time of year. In orbit, there are no clouds, no atmosphere, and the orbital inclination can be optimized for consistent sun exposure.

But—and this is crucial—power isn't the only cost in a data center. Let's actually break down the full cost structure:

Power and cooling: 30-50% of total operating expenses

Labor and operations: 15-25% of total operating expenses

Real estate and facilities: 10-20% of total operating expenses

Capital equipment depreciation: 10-20% of total operating expenses

Networking and security infrastructure: 5-15% of total operating expenses

So even if orbital deployment cuts power costs by 70 percent, you're only reducing total costs by 20 to 35 percent. That's meaningful, but it's not a slam dunk. You're also adding new costs that don't exist terrestrially:

Launch costs: Every piece of hardware requires expensive spaceflight

Orbital operations: You can't send a technician to fix hardware that fails in space

Data transmission latency: Downloading massive model outputs back to Earth has bandwidth constraints

Thermal management complexity: You need sophisticated systems to handle heat dissipation in vacuum

Maintenance and replacement: GPU failures require entire satellite replacement, not individual component swaps

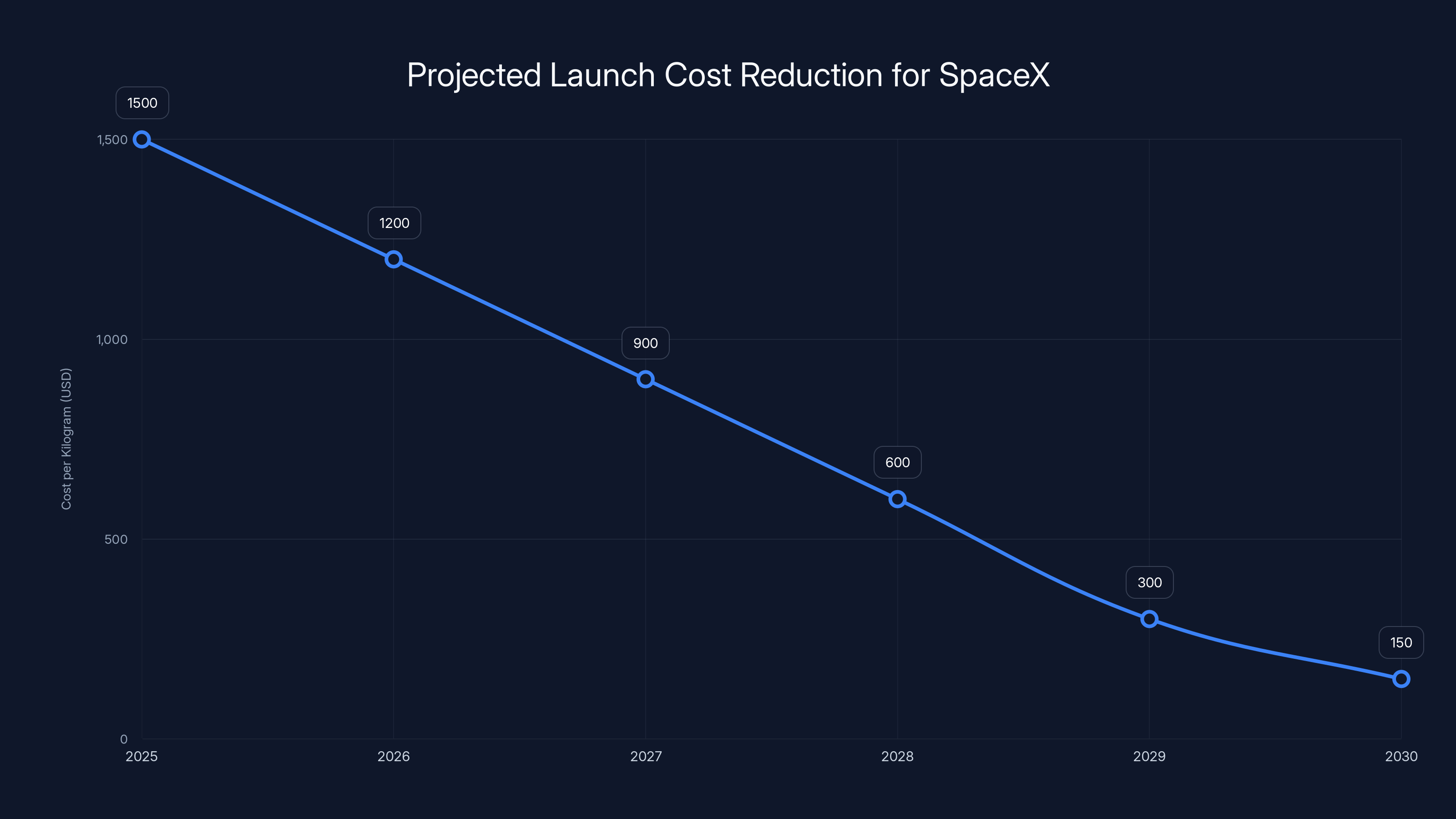

Musk's counter-argument is that as launch costs continue falling—SpaceX has ambitions to get to

Let's model this. Assume a ground data center costs

The critical insight is that Musk isn't wrong about the direction. He's betting on a time horizon where orbital deployment becomes genuinely cheaper. The question isn't whether the physics works—it does. The question is whether the engineering challenges can be solved fast enough, and whether launch costs fall fast enough, to make it economically viable at massive scale before alternative technologies disrupt the need for it.

The Physics Problem: Cooling in Vacuum

Here's where Musk's argument gets genuinely tested, and where the science becomes adversarial. Most people assume cooling in space would be trivial since it's cold. In reality, space is both incredibly cold and incredibly hostile to heat dissipation. That's a paradox worth understanding.

In space, there's no atmosphere. That means no convection cooling—the primary mechanism by which air-cooled computers on Earth dissipate heat. A GPU running full-power generates roughly 300 to 400 watts of heat. On Earth, that heat is carried away by fans pushing cool air over heatsinks. In vacuum, there's nothing to push.

Instead, orbital systems rely entirely on radiation cooling. Objects in space emit thermal energy as electromagnetic radiation. The rate of this radiation follows the Stefan-Boltzmann law:

The implications are brutal. A GPU generating 400 watts of heat needs a radiator with enormous surface area to dissipate it purely through radiation. The colder the radiator can stay, the more efficiently it radiates. In Earth orbit, facing away from the sun and toward deep space, temperatures can reach -50°C or colder. But that radiator still needs to be physically large.

Let's run the numbers. Assume a 400-watt GPU needs a radiator operating at around 70°C (343 K) to maintain safe GPU temperatures. Assuming emissivity of roughly 0.9 (a good radiative coating), we get:

Solving for A, we need roughly 0.8 to 1.2 square meters of radiator surface per GPU. For a satellite packed with, say, 100 GPUs, that's 80 to 120 square meters of radiator surface. Now imagine trying to pack a satellite with enough radiator surface while also fitting power systems, structural components, and all the networking hardware. The physical constraints become real fast.

But the aerospace industry has solved this before. Deep space probes like Cassini and New Horizons operate at extreme distances where solar power is useless and radiative cooling is the only option. The technology exists. It's just not been deployed at the scale of thousands of satellites simultaneously.

The added complexity is that orbital debris, micrometeorites, and solar radiation damage radiator coatings over time. Regular re-coating would require bringing satellites back to Earth or sending up maintenance units. That's where the engineering becomes expensive. You're not just dealing with the physics of cooling. You're dealing with maintenance, longevity, reliability, and degradation over years of operation.

Another wrinkle: redundancy and reliability. When a GPU fails in a terrestrial data center, you replace it. When a GPU fails on an orbital satellite, you either send another satellite to replace it or you accept reduced capacity. The reliability requirements become much higher. Components need to be qualified for multi-year operation in harsh radiation environments. That increases component cost and limits your access to off-the-shelf hardware.

SpaceX aims to reduce launch costs from

The Latency Challenge: Speed of Light Isn't Infinitely Fast

One of the subtler arguments against orbital data centers gets dismissed too quickly: latency. People hear "speed of light" and assume it solves all geography problems. But when you're dealing with AI models training on massive datasets, latency matters profoundly.

Consider the physics. Low Earth orbit sits at about 400 to 2,000 kilometers altitude depending on inclination. The speed of light is 299,792 kilometers per second. So a one-way trip from Earth to LEO and back takes roughly 3 to 13 milliseconds depending on altitude and geometry. That sounds trivial. But in the context of AI training, where you're shuffling terabytes of data constantly, those milliseconds accumulate.

Here's the real problem: most AI training doesn't work like a simple request-response where a user asks a question and gets an answer back. Instead, you have a distributed training setup where gradients and model parameters flow constantly between compute nodes. If you're running orbital satellites as part of a training cluster, every gradient update has that 3 to 13 millisecond round-trip delay. With synchronous training—where all nodes must complete their step before moving to the next—that latency multiplies across iterations.

For a training run with 1,000 iterations where you have 10 percent of your compute in orbit and 90 percent on Earth, you're adding roughly 3 to 13 milliseconds per iteration just for the round-trip communication. Over 1,000 iterations, that's 3 to 13 seconds of cumulative delay. In a training run that takes weeks, that's negligible. But if you're pushing for faster convergence, trying to train models 10 percent faster, now orbital latency becomes a bottleneck.

There's also the bandwidth problem. Downloading trained models from orbit requires data transmission at the speed of light through atmospheric layers and back down to ground stations. Current satellite internet providers like Starlink manage roughly 100 to 200 megabits per second for consumer users. A ground station with dedicated infrastructure might achieve gigabits per second, but you're still bottlenecked by the number of ground stations and their coverage. For a truly massive orbital data center constellation, you'd need hundreds of ground stations globally. That's significant infrastructure investment.

Musk's counter here is that as neural networks become more compute-intensive relative to data-intensive, latency becomes less critical. If you're training on local datasets and only occasionally syncing models, then terrestrial latency doesn't matter. You're making the case that future AI doesn't require constant data shuffling. Instead, you train more locally, sync less frequently. That's technically possible, but it shifts training paradigms in ways that the industry hasn't fully committed to.

The latency problem also depends on what kind of workload you're running. Inference—where a trained model makes predictions—is embarrassingly parallel. Each inference is independent. Latency across a few milliseconds doesn't kill throughput. Training, especially large-scale distributed training, is tightly coupled. That's where latency matters most.

Power Generation and Energy Efficiency in Orbit

The solar power story is the foundation of everything Musk is proposing. But the engineering of actually harvesting, storing, and distributing that power in orbit is remarkably complex. Let's dig into what we're actually dealing with.

Orbital solar panels generate direct current directly from sunlight. Modern space-grade photovoltaic cells achieve about 30 to 32 percent efficiency—converting 30 percent of incoming solar radiation to electricity. That's significantly better than terrestrial panels (15 to 22 percent) partly because there's no atmospheric loss, and partly because space-grade cells are optimized for radiation resistance and longevity rather than cost.

With solar irradiance of 1,361 W/m² in space and 30 percent cell efficiency, you get about 408 watts per square meter of panel. That's genuinely impressive. A 10 square-meter solar array in orbit generates roughly 4 kilowatts continuously (minus eclipse periods).

But here's the catch: satellites aren't in sunlight 24/7. Depending on orbital inclination and altitude, they spend 30 to 70 percent of their orbit in Earth's shadow. That's called the eclipse period. During eclipse, you're running entirely on stored energy. That means you need massive battery capacity relative to your power draw. For a satellite that generates 100 kilowatts during sunlight, you might need 30 to 50 kilowatt-hours of battery capacity to maintain operations through a 30-minute eclipse. Modern lithium-ion batteries achieve about 250 watt-hours per kilogram. That means you need 120 to 200 kilograms of batteries per 100 kilowatts of power capacity. That's significant mass that reduces the power available for computational hardware.

The solution is eclipse-aware scheduling. During eclipse periods, you reduce computational load. Maybe certain training tasks pause. Inference continues at reduced rate. Maintenance and housekeeping tasks run. This is manageable but adds operational complexity. You're not getting 24/7 continuous computation. You're getting maybe 60 to 70 percent utilization if you're optimizing for eclipse periods.

Another subtlety: power regulation and conversion. Orbital solar panels generate unregulated direct current that fluctuates with panel orientation and eclipse transitions. That needs to be conditioned, stabilized, and converted to the appropriate voltage and current for different systems. Power distribution systems add loss—typically 5 to 10 percent depending on design. Storage adds efficiency loss. Conversion adds loss. By the time your raw solar energy becomes usable computational power, you might be looking at 70 to 80 percent overall efficiency from raw photons to actual GPU cycles.

When Musk claims 5x more power in space, he's referring to raw solar irradiance difference. The actual usable computational power advantage is probably more like 3x to 4x after accounting for all these losses. Still a tremendous advantage over terrestrial deployment, but not as clean as the raw number suggests.

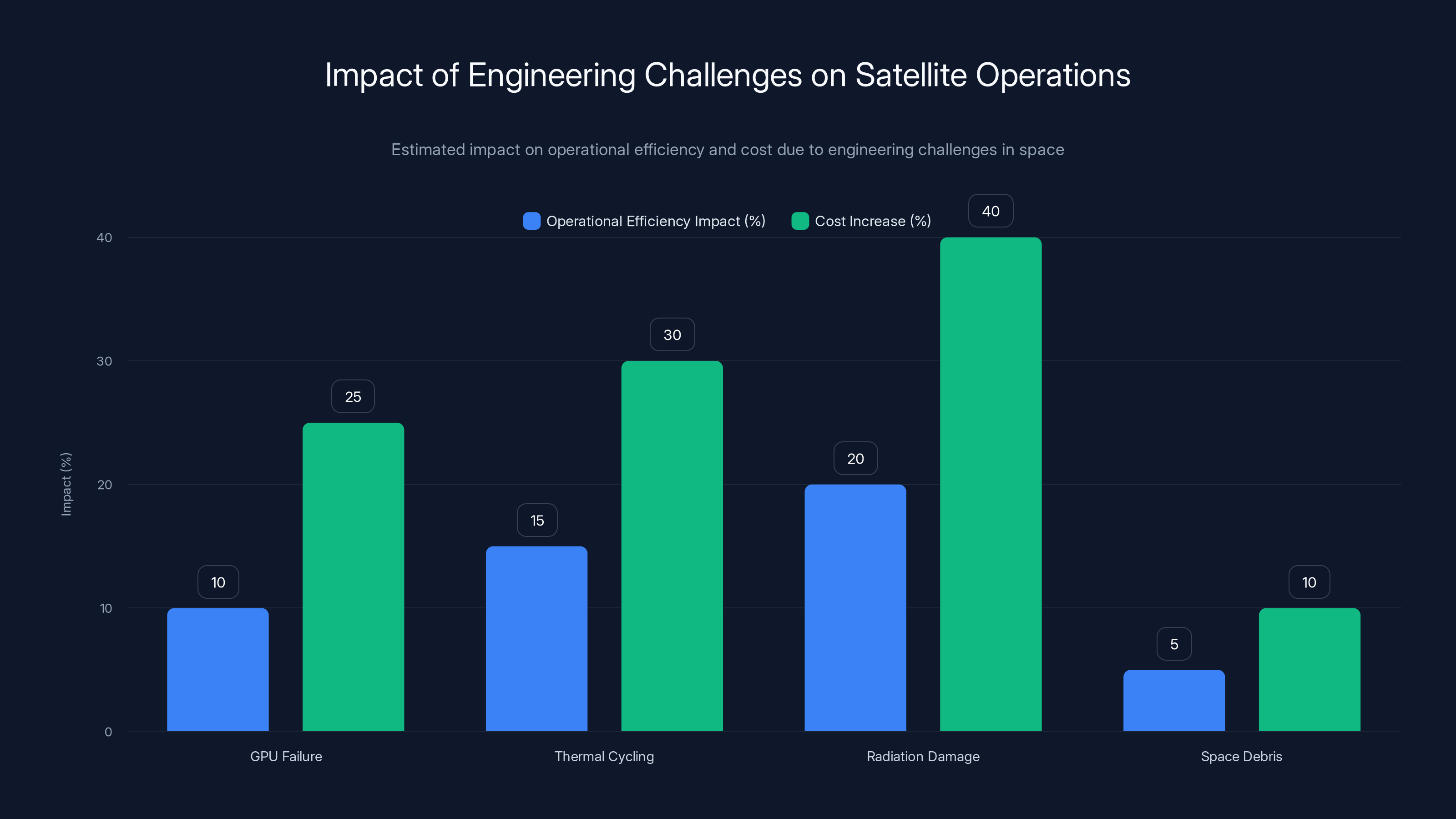

Engineering challenges such as radiation damage and thermal cycling can significantly reduce operational efficiency and increase costs for satellite operations. Estimated data.

The SpaceX-x AI Merger: Vertical Integration Play

Last week's SpaceX-x AI merger isn't accidental timing. It's the essential piece that makes orbital data centers viable as a business strategy. Let's understand why this matters and how it changes the competitive dynamics.

x AI was founded by Musk to compete with OpenAI and Anthropic. It's building large language models and needs massive computational infrastructure. That's expensive. Very expensive. A single training run for state-of-the-art models costs tens of millions of dollars. The infrastructure to support that costs billions. Scaling means spending more billions on data centers, power infrastructure, and cooling systems.

SpaceX has launch capability. It dominates commercial spaceflight. Falcon 9 reusability is revolutionary. But space is SpaceX's offering—they launch things for other companies. That's profitable but limited. The company grows with the launch market, which is growing but not explosively.

Now combine them. SpaceX launches orbital data center satellites for x AI. x AI builds AI models on those satellites. SpaceX's launch rate increases because they're launching their own satellites at scale. x AI's computational costs decrease because it owns the launch company and builds infrastructure at cost rather than paying premium rates. The vertical integration creates synergies that neither company has independently.

More importantly, it changes market dynamics for competitors. OpenAI doesn't own a space company. Anthropic doesn't either. If orbital data centers become viable and cost-competitive, every AI company would need to either build orbital infrastructure or negotiate with whoever controls it. SpaceX-x AI could become a computational commodity provider at scale. That's a completely different business model than either company has operated under.

The IPO timing is also strategic. SpaceX is planning to go public within months. The orbital data center story becomes a growth narrative. Investors see launch business growing. They see computational infrastructure being built. They see a pathway to becoming the AWS of space-based compute. The valuation implications are massive.

This also explains why the regulatory pathway is accelerating. The FCC chairman, Brendan Carr, is known for favorable treatment of Musk and Trump administration priorities. The SpaceX-x AI conglomerate has tremendous political support. The regulatory approval likely moves faster than it would for a competing proposal. That first-mover advantage could lock SpaceX into dominant market position before competitors catch up.

From a competitive standpoint, what makes this genuinely threatening to established players? Cloud providers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure have built their empires on terrestrial data center dominance. If orbital deployment becomes cheaper and faster to scale, their competitive moat erodes. They can't match SpaceX's launch capability without massive capital expenditure and years of development. By the time they could build orbital infrastructure, SpaceX-x AI might already control favorable orbital positions, have cost advantages from rapid launch iteration, and have established relationships with major customers.

The Timeline: 2028 to 2030 and What It Requires

Musk has made specific claims about timelines. He predicts orbital compute becomes the "most economically compelling place" for AI by 2028 to 2030. Let's parse what that actually means and what it would require to happen.

First, the baseline: as of 2025, Earth-based data center capacity is roughly 200 gigawatts. That's equivalent to the power generation of maybe 200 large coal plants, dedicated entirely to computing infrastructure. Converting that to monetary terms, assuming roughly

For orbital deployment to become "economically compelling," SpaceX needs to demonstrate that it can launch, deploy, and operate orbital compute cheaper than terrestrial deployment. Not just at the margins, but compellingly cheaper. Cheap enough that every new data center dollar flows toward orbital rather than terrestrial. That's a high bar.

What does this require? First, SpaceX needs to achieve even lower launch costs. Current prices are

Second, SpaceX needs to manufacture and test thousands of satellite units. Building one prototype satellite is easy. Building thousands capable of reliable operation is another matter entirely. The manufacturing ramp requires dedicated facilities, supply chain development, and production scaling. That takes years and massive capital investment.

Third, they need to solve the operational problems. Launching thousands of satellites with GPUs means managing thousands of failure modes. Something will fail. You need monitoring, diagnostics, and replacement strategies. You need ground station networks. You need data transmission infrastructure. You need customer APIs and software frameworks. That's engineering work for hundreds of people over years.

Fourth, the regulatory pathway needs to clear. FCC approval for spectrum allocation, orbital slots, and debris mitigation. International coordination for satellites that cross borders. Export controls on advanced chip technology in space. These aren't trivial. They can move faster with political support, but they can't move infinitely fast.

Given all this, Musk's 2028 to 2030 timeline for "most economically compelling" is optimistic. It's not impossible. It's the kind of timeline SpaceX has hit before with Starship and Falcon 9. But it requires everything to work. No major setbacks. Rapid manufacturing scaling. Successful test flights. Regulatory alignment. That's a lot to require simultaneously.

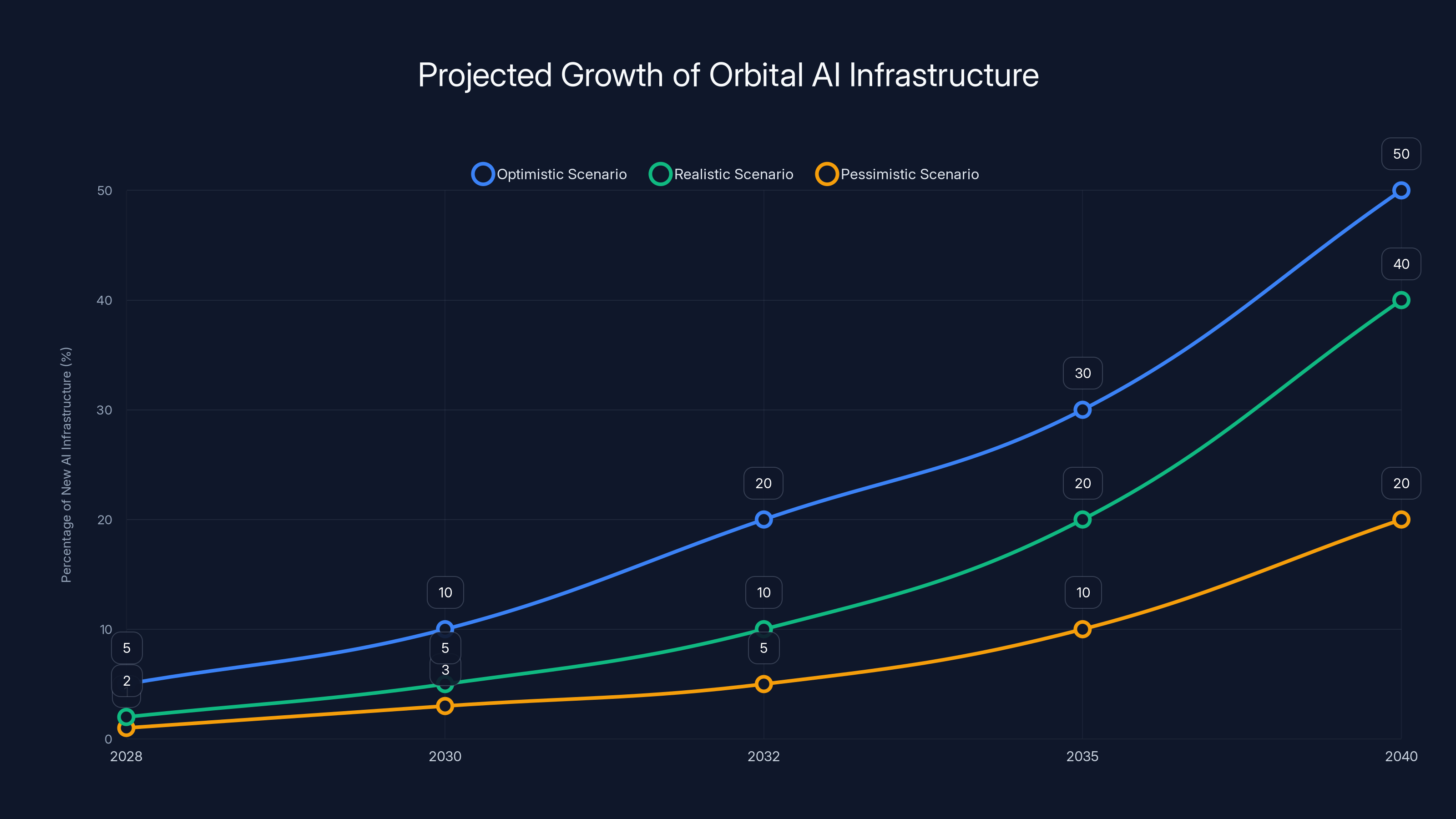

What's more realistic? Probably that by 2028, SpaceX has a functional orbital data center constellation with maybe 500 to 2,000 satellite units operational. It's running training workloads. It's demonstrating viability. But it's not yet cheaper than terrestrial for general-purpose compute. By 2030 to 2032, as manufacturing scales and launch costs drop further, orbital becomes genuinely cost-competitive for certain workloads. By 2035, it might be the default for new capacity.

Musk's claim that "within five years, more AI will be launched annually into space than exists on Earth cumulatively" is even more aggressive. That means growing orbital capacity from zero to exceeding 200 gigawatts of current terrestrial capacity. In five years. That would require launching roughly 40 to 50 gigawatts of new capacity every year. At current manufacturing and launch rates, that's implausible. You'd need to be building and launching multiple times current production capacity. That's possible if you throw enough resources at it, but it's a massive undertaking.

So here's the reality check: Musk is right that the direction is inevitable. Orbital compute will eventually be cheaper. But the timeline is probably compressed by his optimism. The actual deployment curve is likely more like a hockey stick—flat for a few years while the company builds infrastructure and solves engineering problems, then steep growth once viability is proven. We're still in the flat part.

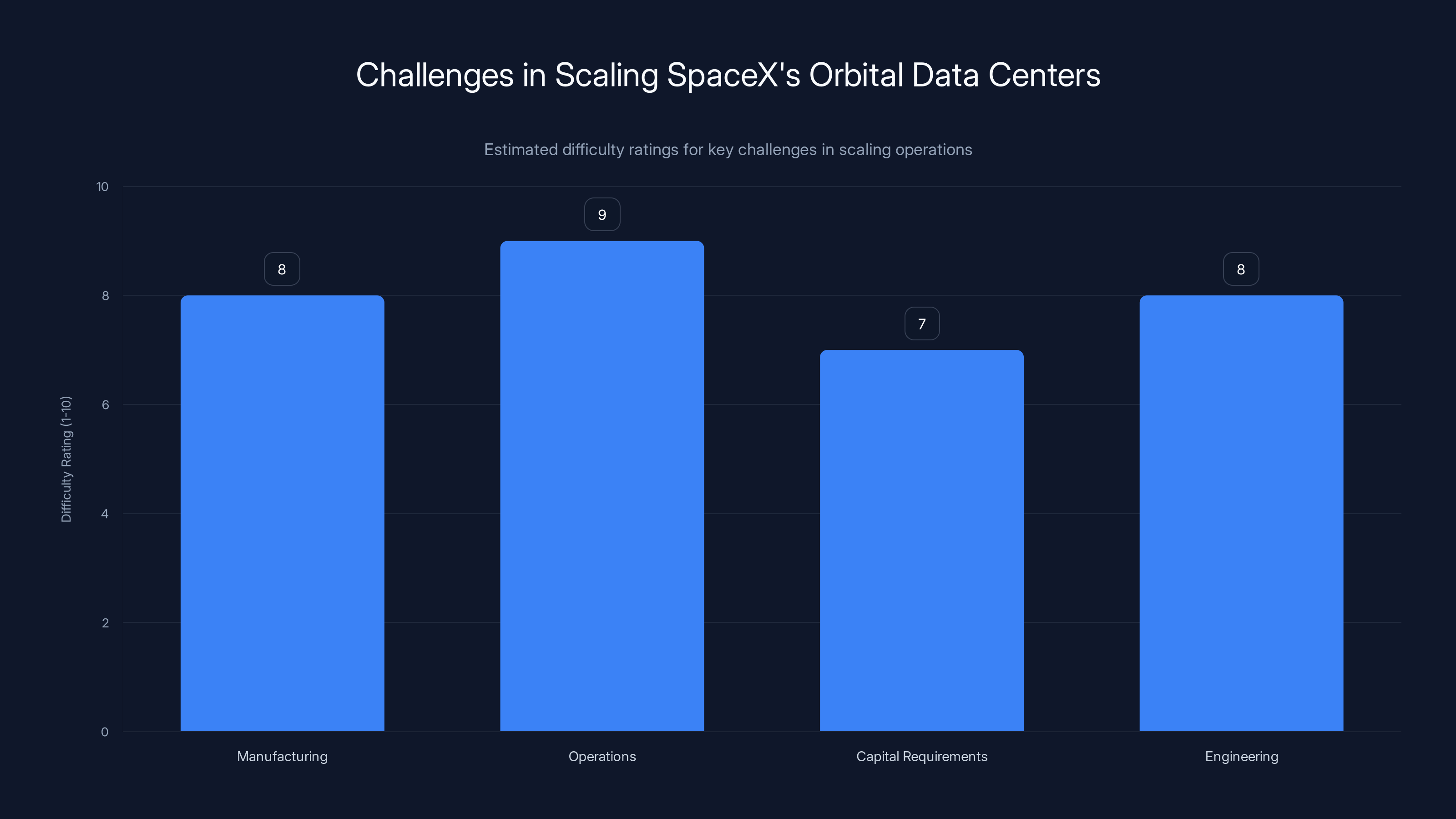

Estimated data suggests that operational complexity and manufacturing are the most challenging aspects for SpaceX in scaling orbital data centers.

Obstacles That Actually Matter: The Real Engineering Challenges

Beyond the marketing narratives and the optimistic timelines, there are genuine engineering obstacles that can't be handwaved away. These aren't physics problems. Physics works. These are engineering problems, which are usually much harder.

GPU Failure and Replacement: Modern GPUs fail. They overheat. They encounter manufacturing defects. They degrade under radiation. In a terrestrial data center, you swap out a bad GPU in minutes. In orbit, you can't. Either you accept reduced capacity, or you launch a replacement satellite. Accepting reduced capacity means your actual available compute is maybe 90 to 95 percent of theoretical maximum. That's a real cost. Launching replacements is expensive and operationally complex.

Thermal Cycling Damage: Satellites in orbit experience extreme thermal cycling. During sunlight, the lit side heats up. In eclipse, it cools to negative 50 degrees. Every 90 minutes, this cycle repeats. That's 16 thermal cycles per day. Over months and years, this causes material fatigue, solder joint failures, and component degradation. Managing this requires either heavy redundancy or accepting higher failure rates.

Radiation Damage: Space radiation—solar wind, cosmic rays, trapped radiation in Earth's magnetosphere—damages semiconductor materials over time. Silicon becomes brittle. Transistor gates accumulate charge. Performance degrades. The military and aerospace industries have solutions, but they add cost and weight. Commercial GPUs aren't designed for this. You'd need to either use radiation-hardened versions (fewer, older designs, much more expensive) or accept shorter operational life and more frequent replacement.

Space Debris and Micrometeorites: Orbital space is increasingly crowded with dead satellites and collision debris. A 10-centimeter piece of debris traveling at orbital velocity (8 kilometers per second) has the kinetic energy of a hand grenade. Hitting a satellite with something like that could destroy it. You need shielding, which adds weight. You need to monitor debris and perform evasive maneuvers, which requires propellant and adds operational complexity. Over a 5-year satellite life, the probability of a debris strike increases significantly.

Data Transmission Bottlenecks: Moving terabytes of data from orbit to Earth faces fundamental bandwidth constraints. Ground stations have limited coverage. Atmospheric interference limits data rates. You can't saturate a 1 gigabit connection to ground constantly without overwhelming the ground infrastructure. That means most computation happens on the satellite, with only results transmitted down. But that limits flexibility. You can't easily retrain models or adjust hyperparameters without launching updates to space.

Software Complexity: Operating thousands of distributed compute nodes in space requires software infrastructure that doesn't yet exist at scale. You need distributed scheduling across potentially unreliable nodes. You need fault tolerance for nodes that disappear (orbital decay, collision, failure). You need ways to checkpoint and restart training if a large fraction of your nodes fail. That's research-level challenges in distributed systems.

Power Management Under Load: When you're running AI training, the computational load varies. Your power draw fluctuates. Your thermal output varies. Your battery status changes. Managing all this while optimizing for eclipse periods requires sophisticated power management software. You need to predict demand, schedule workloads, manage priorities. That's another layer of engineering complexity.

International Politics: Launching thousands of satellites with computational capability requires navigating international agreements, export controls, and national security concerns. China and Russia will likely object to US military-adjacent computational infrastructure in orbit. The UN has conventions about space militarization. These aren't laws, but they create political friction. Regulatory approval in one country might create diplomatic tension in others.

None of these obstacles are insurmountable. But they're also not trivial. They require serious engineering effort, significant capital investment, and years of iteration. They're the reason ambitious space projects usually take longer than expected.

Competitive Response: How Will Cloud Providers Respond?

If SpaceX-x AI actually pulls off orbital data centers at scale, what do AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure do? This is where the competitive dynamics become interesting.

The obvious move is to invest in orbital infrastructure themselves. But that runs into a problem: SpaceX has the launch monopoly. No other company can launch at comparable scale or cost. AWS could try to build its own launch company, but that's a 5 to 10-year project minimum. By then, SpaceX might have orbital dominance locked.

The alternative is to partner or compete on terrestrial optimization. Google already invests heavily in chip design, building custom TPUs for AI workloads. They could continue down that path, making terrestrial infrastructure more efficient. Microsoft has partnerships with OpenAI and Anthropic. They could offer traditional data center capacity at competitive prices based on scale. Amazon has regional presence everywhere. They could argue that local data center presence beats orbital latency for inference workloads.

The reality is probably fragmentation. Certain workloads migrate to orbit if it's cheaper. Inference workloads might stay terrestrial for latency reasons. Different AI companies make different bets. Some use SpaceX-x AI orbital infrastructure if it's competitive. Others stay terrestrial. The market probably accommodates both for a decade. Eventually, orbital becomes dominant, but not universally.

The wildcard is new entrants. If SpaceX proves the model works, other launch companies might emerge or scale. Blue Origin has New Shepard and New Glenn in development. Axiom Space is building commercial space stations. If multiple launch providers compete on cost, the orbital infrastructure market becomes less concentrated. That actually speeds adoption across the industry.

Another competitive vector is technology improvement. Quantum computing, neuromorphic chips, optical processors—if any of these mature faster than orbital deployment, they could reduce the value of scaling to space. But that's years away. Near-term, orbital compute is the most plausible way to break free from power and cooling constraints.

The chart illustrates the projected growth of orbital AI infrastructure under different scenarios, with the optimistic scenario reaching up to 50% by 2040. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Real Bottleneck: Can SpaceX Execute at Scale?

Everything hinges on one question: can SpaceX actually execute this at scale? They have a track record of succeeding at impossible-seeming projects. Falcon 9 reusability. Starship development. But orbital data centers are different. It's not just about building rockets. It's about building and operating thousands of complex satellites, managing them over years, keeping them reliable, scaling manufacturing, and delivering value to customers. That's harder than building rockets in some ways.

Manufacturing is the critical constraint. Building one satellite is engineering. Building a hundred satellites is production. Building a thousand satellites requires factory discipline, supply chain management, quality control at scale, and the ability to catch and fix systemic issues before they propagate across your fleet. SpaceX has some manufacturing expertise from Falcon 9 production. But space-grade satellite manufacturing is different. Tighter tolerances. More critical reliability. Harder to iterate once deployed.

Operations at scale is another challenge. SpaceX runs Starlink, which has thousands of satellites in orbit. But Starlink satellites don't run customer computational workloads. They're more like communication infrastructure. Operating thousands of data center satellites where customers depend on uptime, where failures cause lost training runs, where debugging requires reaching out to orbit—that's operationally more complex.

Capital requirements are also massive. The first few hundred satellites and the ground infrastructure probably costs

The wildcard is whether the engineering actually works in practice. Will GPUs stay within thermal limits? Will radiation damage be as predicted? Will the software systems actually manage thousands of unreliable nodes? Will latency be tolerable for customers? Until they've operated this at scale for a year, there's inherent risk. Markets don't reward successful predictions. They reward successful execution.

What This Means for AI Development and Compute Economics

Assuming some version of this actually works—not perfectly, but viably—what does it mean for how AI gets built and deployed? The implications are broader than just infrastructure cost.

First, it changes the compute power available. Currently, the largest AI training runs are bottlenecked by available compute. The largest clusters are maybe 10,000 to 100,000 GPUs. That's enough for very large models, but it's still a constraint. If orbital deployment adds another order of magnitude of compute capacity, suddenly training runs that were infeasible become possible. Models get larger. Training times get shorter. Experimentation becomes cheaper.

Second, it democratizes compute access. Right now, only companies with massive capital can afford to train large models. OpenAI, Google, Meta, Microsoft. That's it. Everyone else either uses APIs or smaller models. If orbital infrastructure is cheaper, it might lower barriers to entry. Smaller companies could potentially afford to train competitive models. That democratization is profound for industry structure.

Third, it potentially changes where computation happens. If latency becomes less critical, more computation could migrate to where power is cheap and abundant (space). If inference stays on Earth and only training migrates, workload patterns change completely. That affects networking infrastructure, data movement, and software architecture.

Fourth, it accelerates the timeline toward AI singularity if you believe such a thing is approaching. More compute available faster means faster iteration, faster scaling. The technological trajectory accelerates. That has implications for safety, policy, and how quickly AI capabilities outpace society's ability to regulate them.

Fifth, it raises questions about power consumption sustainability. Even if orbital compute is cheaper, it's still consuming vast amounts of electricity. That comes from solar panels that have finite manufacturing capacity. Supply chains for rare earth elements. Manufacturing footprints. Moving computation to space doesn't solve sustainability concerns. It just relocates them.

Regulatory Landscape: How Fast Can Approvals Actually Move?

The FCC accepted SpaceX's filing. FCC Chairman Brendan Carr publicly supported it. That suggests regulatory approval might move quickly. But orbital spectrum allocation, debris mitigation, and safety considerations don't resolve overnight, even with political support.

The key regulatory challenges are spectrum allocation (which radio frequencies can the satellites use), orbital slot assignments (where in orbit they can operate without collision risk), and debris mitigation plans (what happens when satellites fail or reach end of life). The FCC has authority over US operators, but international coordination is also necessary.

Historically, FCC approvals for satellite projects take 6 to 18 months depending on complexity. SpaceX has political tailwind, which probably accelerates this. Optimistically, they might have operational approval by 2027. Realistically, probably 2028. That's not blocking the timeline so much as confirming it.

The wildcard is international opposition. China and Russia might formally object to military-adjacent computational infrastructure in orbit. The UN might raise concerns. These don't necessarily stop approval, but they create political friction and might impose conditions (debris monitoring, deconfliction agreements, etc.) that add complexity.

The Climate Angle: Energy Sourcing and Sustainability Questions

Musk frames orbital compute as solving power limitations. But powering a thousand satellites with enough solar panels to generate hundreds of megawatts is still a massive undertaking. Where does the manufacturing capacity come from? Who makes these solar cells? What's the supply chain?

Orbital solar panels require specialized materials and manufacturing processes. They're not mass-produced. Scaling solar manufacturing for space could take years. It's a separate bottleneck from satellite manufacturing and launch capacity. If solar panel production becomes the constraint, orbital deployment slows significantly.

There's also the carbon question. Launching hardware to orbit requires rockets that burn fuel. A Falcon 9 launch burns about 340 tons of rocket propellant. Reducing carbon footprint of orbital compute means either using green rocket fuel (not yet mature at scale) or accepting that the carbon cost is front-loaded. If you amortize it over years of operation, orbital compute powered by solar is probably cleaner than terrestrial compute powered by the grid. But the absolute carbon cost of deployment is higher initially.

For companies genuinely concerned about carbon footprint, orbital compute might not be the solution they're looking for. But for pure cost optimization, it probably is.

Future Scenarios: When and How Does This Actually Happen?

Let's sketch a few plausible scenarios for how this unfolds:

Scenario One: Optimistic Timeline

SpaceX successfully tests Starship launches multiple times in 2026 and 2027. Launch costs drop to

Scenario Two: Realistic Timeline

SpaceX faces manufacturing challenges ramping satellite production. Gets maybe 200 to 300 satellites to orbit by 2029. Operational issues (thermal management, radiation effects, software bugs) require more iteration than expected. First-generation satellites underperform cost expectations. x AI runs some training on orbital infrastructure, but supplements with traditional data centers because orbital is less reliable initially. By 2030, SpaceX has 1,000 to 2,000 operational satellites. Orbital compute is maybe 5 to 10 percent cost-competitive with terrestrial for specific workloads, but not broadly. By 2033 to 2035, manufacturing and operations mature. Orbital becomes genuinely cost-competitive for new capacity. By 2040, orbital represent 30 to 50 percent of new AI infrastructure.

Scenario Three: Pessimistic Timeline

SpaceX encounters unexpected engineering challenges (radiation damage worse than predicted, cooling insufficient for dense packing, software complexity exceeds expectations). Manufacturing ramp is slower than anticipated. Gets maybe 500 to 1,000 operational satellites by 2030, but they're only achieving 60 to 70 percent of design specs. Cost per unit of compute ends up higher than traditional data centers once you account for all failures and maintenance. The project is viable but not revolutionary. By 2032, SpaceX has modest orbital capacity running for x AI. Other companies see limited advantage and continue terrestrial deployment. Orbital compute becomes a niche offering for specific workloads (maybe inference where latency doesn't matter, or training for companies willing to accept higher failure rates). By 2040, orbital represent maybe 10 to 20 percent of infrastructure.

Scenario Four: Disruption

A competing technology matures faster than expected. Quantum computing reaches practical utility for specific AI workloads. Optical processors become viable at scale. Neuromorphic chips mature faster than predicted. Suddenly, terrestrial compute doesn't look as constraining. The need for orbital infrastructure diminishes. SpaceX built something viable, but it's not the solution everyone thought it would be. Orbital compute has a role, but not the revolutionary impact predicted.

Which scenario actually happens? Probably some combination of Scenario Two and Three. SpaceX succeeds, but not as comprehensively or quickly as Musk predicts. Orbital compute becomes viable, but more as a complement to terrestrial infrastructure than a wholesale replacement. Growth accelerates from there as engineering matures and costs drop further.

Investment and Market Implications

If orbital compute becomes real, what's the investment thesis? Who benefits? Who gets disrupted?

Winners:

- SpaceX and x AI: Obviously. They're building the infrastructure. They control margins. They have first-mover advantage. The valuation is potentially enormous.

- Semiconductor manufacturers: If demand for space-grade chips increases dramatically, chip designers benefit. AMD, NVIDIA, Intel—they sell chips. Orbital deployment is just more chips sold.

- Launch providers: Any company with spaceflight capability benefits. Blue Origin, Axiom Space, Chinese launch companies. More satellites means more launch business.

- Satellite manufacturers: The companies that build the satellite bus (the physical structure) benefit from volume.

Losers:

- Traditional data center companies: If orbital compute becomes cheaper, traditional data center growth slows. Switch, Digital Realty, Equinix—these REIT companies benefit from steady data center demand. Disruption threatens their growth. Probably not existential, but concerning.

- Real estate near cheap power sources: Historically, data centers locate near hydroelectric power, cheap natural gas, or nuclear plants. If compute migrates to orbit, land values in these regions might soften.

- Cooling companies and power infrastructure providers: There's entire industries selling cooling systems and power distribution to data centers. Orbital compute doesn't need these. That's not huge money, but it's real.

Wildcards:

- Cloud providers: AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft might lose AI infrastructure market share to SpaceX-x AI. Or they might adapt by building their own orbital infrastructure or competing on other dimensions. Outcome is unclear.

- AI companies: Reduced compute costs could democratize AI development. More competition. Or SpaceX could become a compute bottleneck (if they're the only orbital provider). That would be a different kind of concentration risk.

Conclusion: The Space-Based Compute Era Is Probably Coming

Let's step back and assess what we actually know. Musk isn't making this up. The physics works. Orbital solar is genuinely more efficient than terrestrial. Launch costs are genuinely dropping. SpaceX has the capability to execute. The merger with x AI makes strategic sense. The regulatory pathway is accelerating. These aren't conspiracy theories or marketing hype. They're real.

The question is whether it happens in 3 years or 7 years, at what cost per compute unit, and whether it actually becomes dominant or remains a niche deployment. Here's my honest assessment: by 2030, SpaceX will have functional orbital compute infrastructure with at least 1,000 to 2,000 operational satellites. It will be running real AI training workloads. It will demonstrate the viability of the concept. But it probably won't be cheaper than terrestrial deployment for most workloads yet.

By 2035 to 2040, as manufacturing scales and launch costs continue dropping, orbital becomes cost-competitive and starts replacing new terrestrial deployment. By 2050, orbital probably represents a significant portion (30 to 50 percent) of global AI infrastructure. But it's not replacing everything. Some compute stays on Earth for latency-sensitive applications, regulatory reasons, and sheer inertia.

What makes this genuinely important is the implication for AI development itself. More compute available means faster iteration. Faster iteration means more aggressive scaling experiments. That has implications for safety, capability, and how quickly AI becomes central to global infrastructure. Musk is betting on a future where compute abundance is the bottleneck constraint, so he's removing that constraint. Whether that's wise is a different question.

The smart move for companies and investors is probably hedging. Assume this works to some degree. Assume compute costs drop further. Assume terrestrial data centers remain relevant but less dominant. Build strategies that work in both scenarios. Don't bet everything on orbital. Don't ignore orbital either.

And watch carefully. If SpaceX actually delivers operational orbital data centers by 2028 to 2029, it's one of the most significant shifts in computing infrastructure in decades. If they get delayed to 2032 to 2035, it's still important but less revolutionary. If the engineering challenges prove harder than expected and the first generation underperforms, it's a viable niche product but not world-changing. The next three to five years will tell us which scenario we're actually in.

FAQ

What are orbital data centers and how do they work?

Orbital data centers are networks of computing satellites operating in Earth orbit, networked together through laser and radio links. Each satellite contains GPUs or AI chips and generates its own power through solar panels. They communicate with ground stations and with each other, creating a distributed computing infrastructure in space. Unlike traditional data centers on Earth, they operate in vacuum (eliminating cooling needs), receive unobstructed solar power (5x more efficient than ground-based solar), and provide globally distributed compute capacity.

Why would orbital data centers be cheaper than ground-based data centers?

The primary cost advantage comes from power generation. Solar panels in orbit receive approximately 1,361 watts per square meter of solar irradiance with no atmospheric loss, compared to 200-300 watts per square meter on Earth—roughly 5x more efficient. Power represents 30-50% of traditional data center operating costs. However, this advantage is partially offset by launch costs, maintenance complexity, thermal management in space, and the inability to physically repair hardware. The true cost advantage emerges when launch costs drop significantly (SpaceX targets $100-200 per kilogram eventually) and manufacturing scales to thousands of satellites.

What are the main challenges with putting AI compute in space?

The technical challenges are substantial. Thermal management relies entirely on radiation (no atmosphere for convection cooling), requiring large radiator surfaces. GPUs fail, but replacement requires launching new satellites. Radiation damage degrades semiconductors over time. Space debris poses collision risks. Data transmission from orbit has bandwidth constraints and latency. Satellites experience extreme thermal cycling (16 times per day), causing material fatigue. Software systems must manage thousands of potentially unreliable distributed nodes. And politically, launching military-adjacent computational infrastructure raises international concerns. None are unsolvable, but together they explain why this hasn't been done at scale before.

When will orbital data centers actually become competitive with terrestrial data centers?

Musk predicts 2028-2030, but realistic timelines are probably 2032-2035 for actual cost competitiveness. Even optimistically, SpaceX needs to achieve lower launch costs (currently

How much will it cost to launch and operate orbital data centers?

Initial deployment costs are enormous. Building, launching, and operating a 100-megawatt orbital data center constellation could cost

How does latency affect orbital data center performance for AI?

Latency is a significant consideration for certain workloads. Orbital altitude of 400-2,000 kilometers creates 3-13 millisecond round-trip delays to Earth. For inference workloads (where each query is independent), this is acceptable. For distributed training (where all nodes synchronize frequently), this adds cumulative delay. A 1,000-iteration training run with 10% of compute in orbit might add 3-13 seconds of latency—negligible in week-long training, but problematic for rapid iteration. This suggests orbital compute is best for inference or training paradigms that synchronize less frequently, not for tightly-coupled distributed training.

Will orbital data centers disrupt cloud providers like AWS and Google Cloud?

Probably not completely, but they'll reshape the market. AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure have enormous advantages in software, services, global presence, and customer relationships. Orbital compute solves cost and power constraints but creates new latency and operational challenges. Most likely outcome: cloud providers either build their own orbital infrastructure, partner with SpaceX, or compete by optimizing terrestrial deployment further. The market accommodates both, with orbital taking increasing share over time for cost-sensitive workloads while cloud providers retain advantages for latency-sensitive applications and integrated services.

How many satellites would SpaceX actually need to deploy?

To meaningfully compete with terrestrial data centers, SpaceX would likely need 2,000-10,000 operational satellites depending on power density and redundancy. Each satellite might provide 10-50 megawatts of compute capacity depending on design. Deploying and maintaining that many satellites requires sustained launch operations (SpaceX would need to launch 100-200 satellites monthly at scale), manufacturing facilities producing satellites at rates currently unmatched by any company, and operational infrastructure to manage a fleet that's distributed globally. This is ambitious but not impossible given SpaceX's track record.

What is the environmental impact of orbital data centers?

Launching rockets to deploy infrastructure has upfront carbon costs (roughly 340 tons of fuel per Falcon 9 launch). However, operating thousands of satellites on solar power for years is likely cleaner than terrestrial compute powered by fossil fuels. The net environmental impact depends on rocket fuel type (methane/oxygen is cleaner than older kerosene), manufacturing emissions, and terrestrial grid electricity sources. For companies relying on renewable energy, terrestrial data centers might be cleaner. For most others, orbital solar is probably greener long-term, though the carbon payback period (time to offset launch emissions) could be several years.

Could other companies build competing orbital data center networks?

Yes, but with significant barriers. SpaceX currently has the only operational heavy-lift reusable rocket with demonstrated low costs. Blue Origin has New Glenn in development, but it's years behind. Chinese launch providers could theoretically compete, but export controls on advanced chip technology would limit their options. The first-mover advantage is substantial—SpaceX builds experience, establishes customers, and scales manufacturing before competitors arrive. But by the 2030s, multiple providers with orbital infrastructure is plausible. Market dynamics then shift from monopoly to oligopoly, likely driving further innovation and cost reduction.

Final Thoughts: Watch the Details

Orbital data centers are coming. Not tomorrow, but within this decade in some form. The physics supports it. The business model makes sense. The regulatory path is clearing. Musk's timeline is probably optimistic, but the direction is right.

What matters most over the next two to three years is watching execution details. Can SpaceX actually manufacture satellites at scale? Do thermal management systems work as designed? How severe are radiation effects in practice? Can the software infrastructure actually manage distributed compute reliably? These details determine whether orbital compute becomes world-changing or remains a specialized capability.

For most people, this is abstract infrastructure news. But for AI development, compute infrastructure, and the future of how AI scales, this is foundational. It's worth paying attention to how this unfolds.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX filed FCC plans for million-satellite orbital data center network merged with xAI, combining space launch and AI computing capabilities

- Solar panels produce 5x more power in space than Earth, reducing largest data center operating cost by potentially 30-50% though other costs partially offset gains

- Realistic timeline: functional orbital infrastructure by 2028-2030, cost-competitiveness by 2033-2035, widespread adoption by 2038-2040

- Real engineering challenges (thermal cooling in vacuum, GPU failure management, radiation damage, space debris) are more complex than physics constraints

- Market implications: First-mover advantage for SpaceX-xAI, potential disruption to traditional data center companies, democratization of compute access if successful

Related Articles

- Space-Based AI Compute: Why Musk's 3-Year Timeline is Unrealistic [2025]

- SpaceX's Starbase Gets Its Own Police Department: What It Means [2025]

- Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

- Valve's Steam Machine & Frame Delayed by RAM Shortage [2026]

- Google Hits $400B Revenue Milestone in 2025 [Full Analysis]

- Resolve AI's $125M Series A: The SRE Automation Race Heats Up [2025]

![Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/elon-musk-s-orbital-data-centers-the-future-of-ai-computing-/image-1-1770318594437.jpg)