Epic vs Google Settlement: What Android's Future Holds [2025]

Last month, something extraordinary happened in a federal courthouse. The biggest antitrust fight in tech—one that started over a video game and spiraled into a battle for the soul of Android—suddenly shifted. Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney and Google's Android boss Sameer Samat walked into court not as enemies, but as unexpected allies. They'd negotiated a settlement that could reshape how billions of people download apps on Android devices worldwide.

But here's the thing: Judge James Donato wasn't buying their sudden friendship.

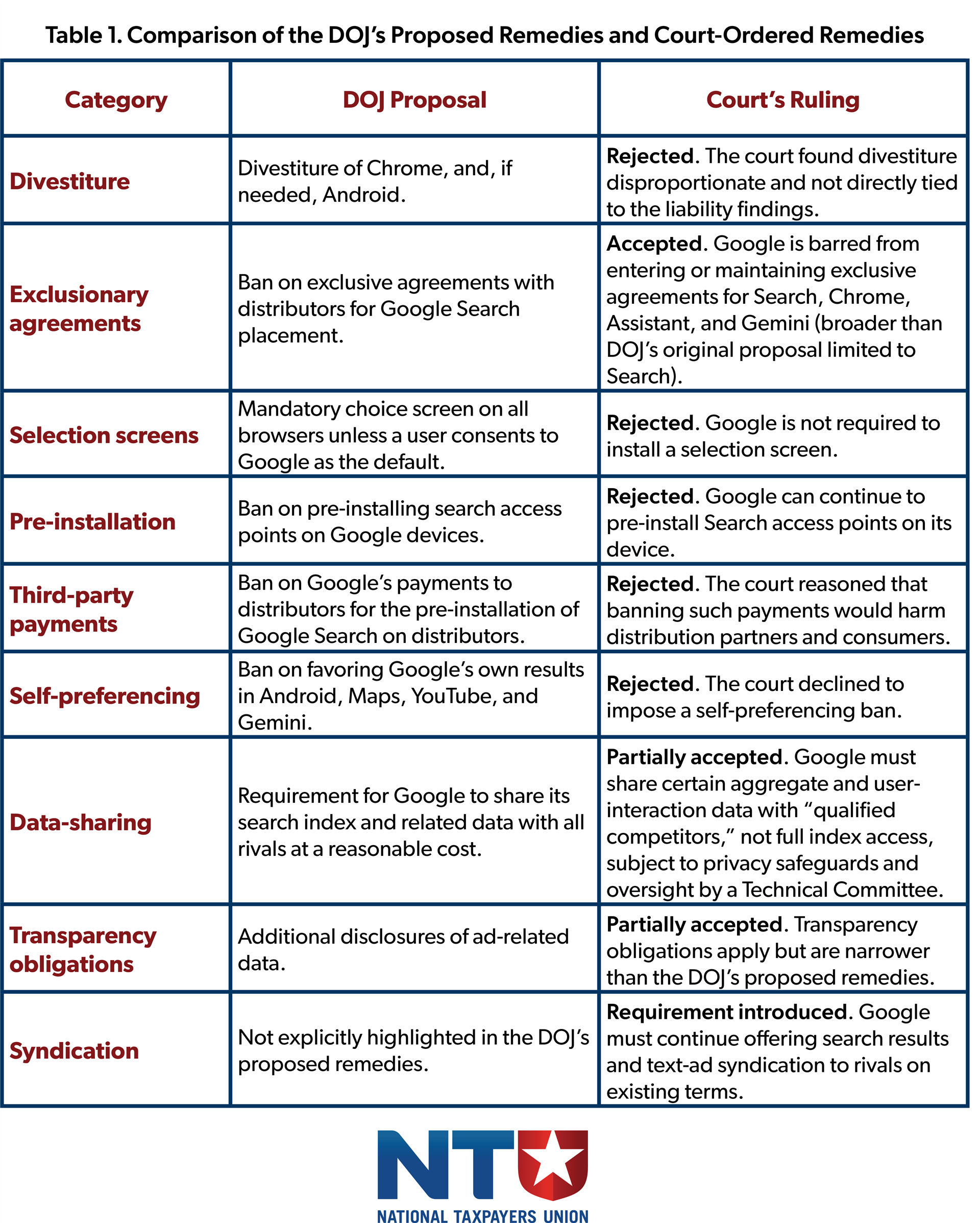

After years of litigation, mountains of evidence, and a jury verdict that sided unanimously with Epic, the two companies showed up claiming they'd reached a deal. The problem? The judge had already ruled Google's Android app store practices were illegal monopoly behavior. Now these two were asking him to let them write their own rules instead of enforcing the punishments he'd ordered.

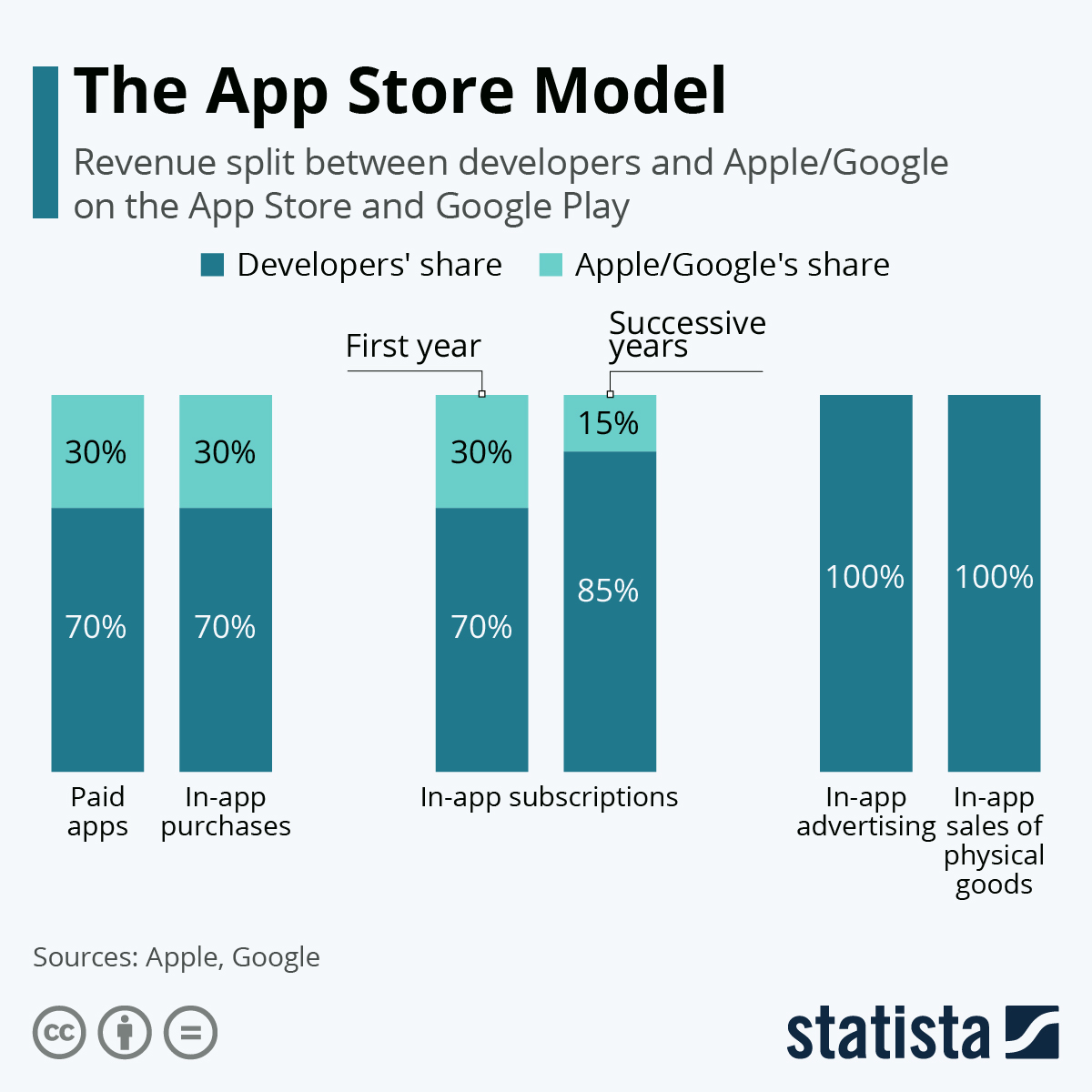

This moment matters more than you might think. It's not just about Fortnite or whether developers pay 30% commission or 15%. It's about whether Google gets to control what billions of people can install on the Android devices they own. It's about whether startup developers can actually compete against Google's app store, or whether they'll always be playing on Google's turf with Google's rules.

Let me walk you through what's actually happening, why it matters, and what comes next.

The Five-Year Battle That Led Here

The Epic vs Google case didn't start with some grand vision of reforming Android. It started the way a lot of tech wars do: with money and frustration.

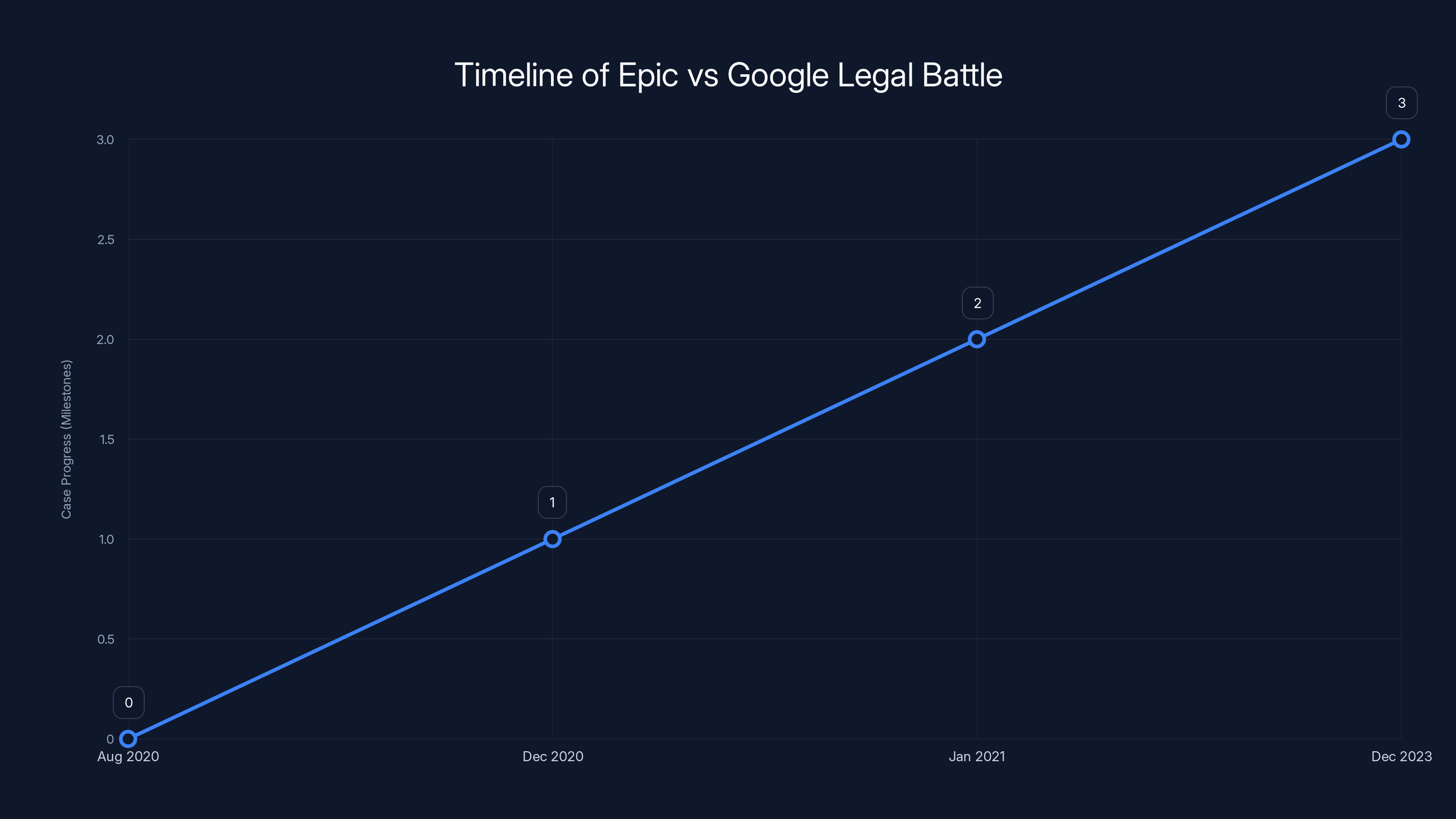

In August 2020, Epic Games decided to stop paying Google's 30% commission on Fortnite purchases made through the Play Store. Instead, they built their own payment system inside the app and passed the savings to players. Google responded exactly how you'd expect: they removed Fortnite from the Play Store within hours. Epic then sued, claiming Google ran an illegal monopoly on Android app distribution.

The case sprawled across years of depositions, expert testimony, and courtroom battles. Lawyers argued about market definition, competitor harm, and what "reasonable" app store fees should look like. Judge Donato heard it all. Then, in December 2023, a jury delivered a stunning verdict: Google's practices violated antitrust law. Unanimously.

That jury didn't just slap Google's wrist. They said the company had illegally maintained its monopoly over Android app distribution. They said competitors had no real ability to challenge Google's dominance. They said consumers were harmed by the lack of choice.

An appeals court upheld that verdict. The Supreme Court didn't intervene to save Google. So Donato did something pretty unprecedented: he ordered Google to actually fix Android, not just pay a fine.

Developers could face

What the Original Judgment Actually Ordered

When judges order structural remedies instead of damages, they're essentially saying: "Your business model is the problem. Change it."

Judge Donato's orders were sweeping. He required Google to:

- Allow rival app stores to exist on Android without being buried or hidden

- Stop discriminating against competitors in search results within its Play Store

- Stop blocking developers from using payment systems Google doesn't control

- Unbundle Google Play Services, which gives Google apps unfair advantages

- Allow sideloading and make it actually easy for users to install apps from other sources

- Impose real restrictions on how Google can retaliate against developers or app stores

These weren't suggestions. They were mandated changes that would fundamentally alter how Android worked. They were supposed to take effect before the end of 2024.

Then, just weeks before that deadline, Epic and Google announced they'd reached a settlement. The case that seemed headed toward complete restructuring of Android suddenly had an off-ramp.

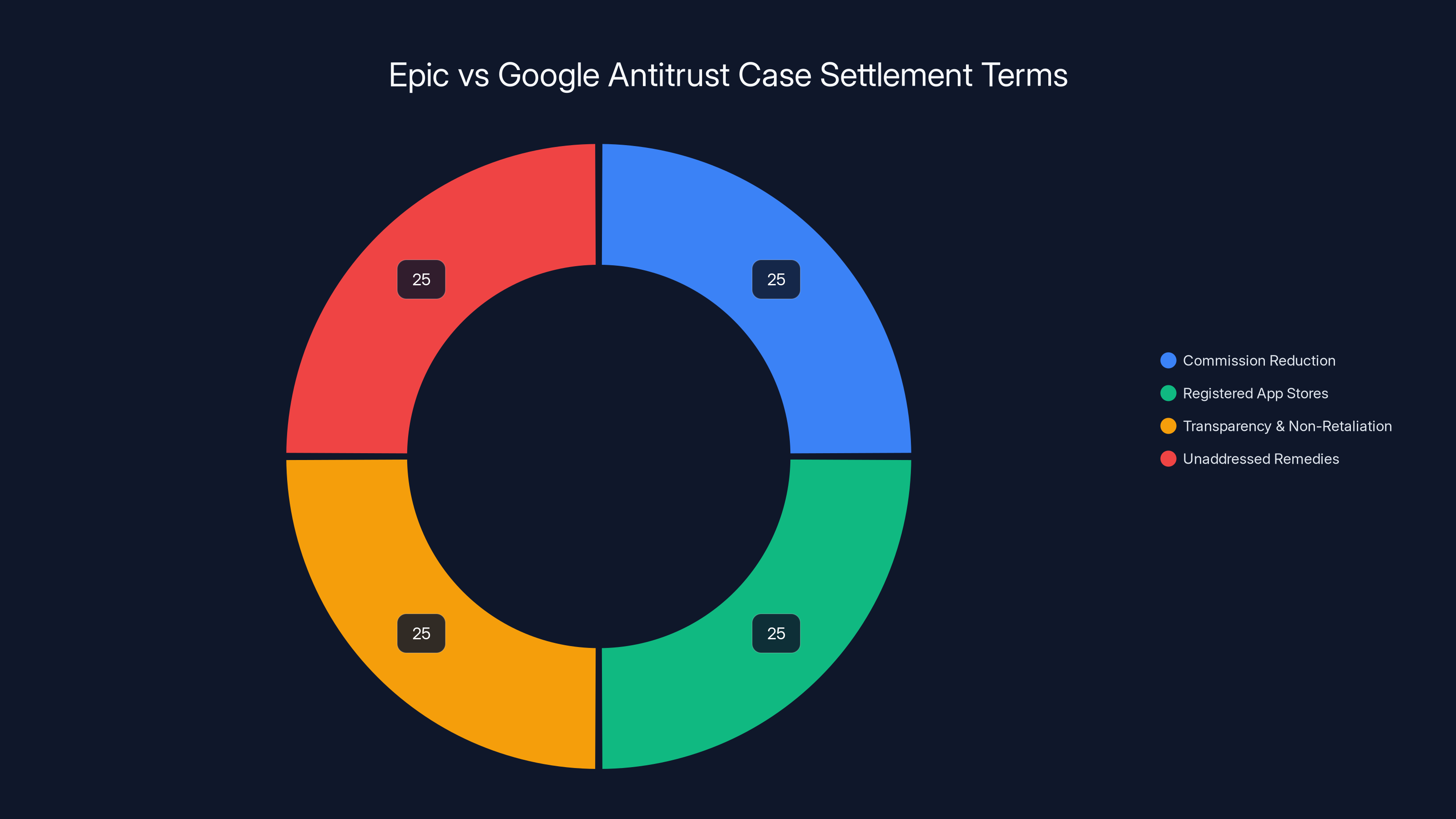

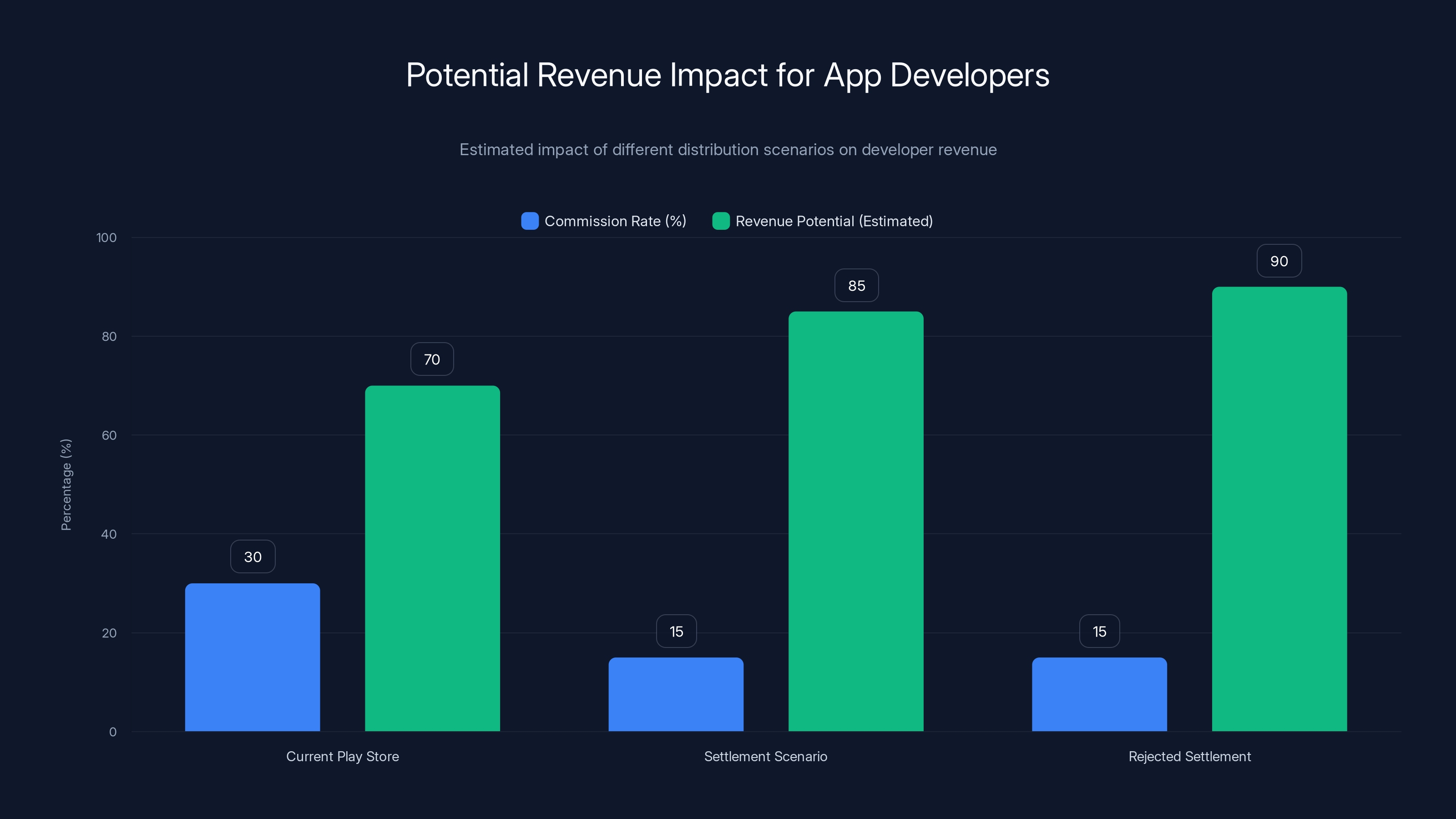

The settlement agreement in the Epic vs Google case includes commission reduction, a Registered App Stores program, and transparency commitments, but leaves many original remedies unaddressed, each component roughly equally weighted. Estimated data.

The Settlement's Global App Store Reduction

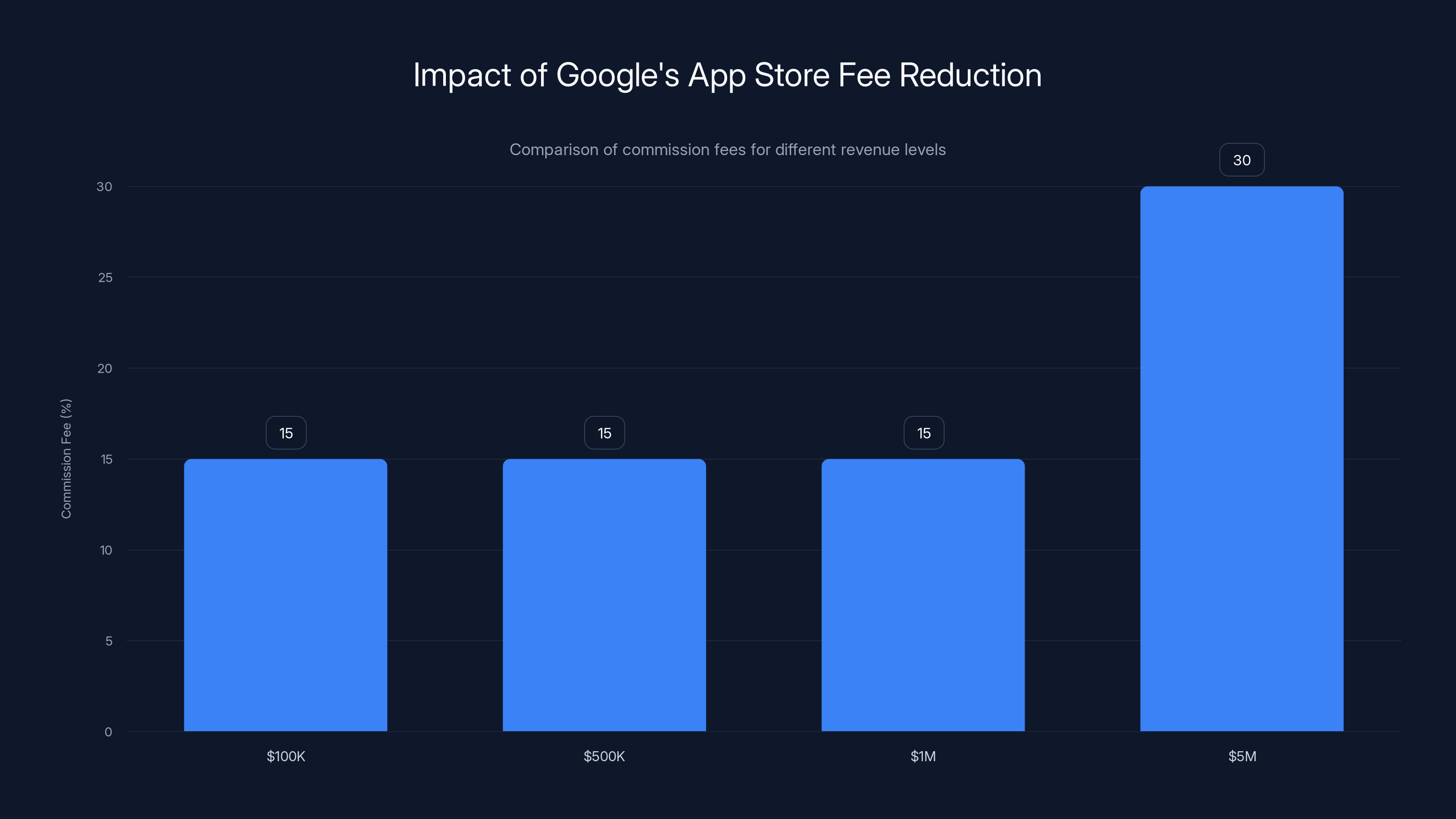

Here's what Epic and Google agreed to: Google would reduce its app store commission fees globally, moving from the standard 30% to 15% for the first $1 million an app earns per year.

That sounds like a win, right? It is, partially. A 50% fee reduction on initial earnings is meaningful. For successful developers, it could mean thousands or millions in savings annually.

But look closer at the math. Google kept the arrangement hidden in technical details for weeks, and when developers finally saw the full picture, the story got complicated.

The reduced 15% rate only applies to the first

Moreover, Google could still extract value through other channels. They could prioritize their own apps in search results (the remedy didn't fully address that). They could make sideloading technically complicated or risky-feeling for users. They could place their payment system's terms so that alternative payment methods seemed sketchy by comparison.

The fee reduction addresses the symptom—high commission rates—without necessarily treating the disease, which is that Google controls the distribution channel itself.

The Registered App Stores Program: Freedom or Facade?

The second major component of the settlement is the creation of "Registered App Stores." This is where Epic and Google's agreement gets intentionally vague, and Judge Donato could smell it.

The idea is that other companies can now apply to be registered as official app stores within Android. Theoretically, developers could distribute their apps through Samsung's store, through a competing third-party store, or directly through a sideload if they prefer.

But here's the catch buried in the details: Google still controls the approval process. To be a Registered App Store, you have to meet Google's standards. You have to implement Google's security requirements. And critically, you might still have to pay Google fees for the privilege of existing on Android.

This is where Sweeney and Samat's testimony mattered. The judge wanted to know: Are these actually alternative stores with real autonomy, or are they approved subsidiaries where Google still pulls the strings?

There's a precedent here that should worry you. When Apple created its App Store, they claimed small developers and creators had an alternative: sideloading was always technically possible. But Apple made sideloading so cumbersome, risky, and user-unfriendly that the vast majority of people don't even know it's an option. There's a real risk that Registered App Stores become the digital equivalent—technically available, but practically discouraged.

The settlement also doesn't clearly define what fees Registered App Stores would pay. Would they pay the standard 30%? The new 15%? Something custom negotiated with Google? The ambiguity is intentional—it gives Google room to negotiate different rates with different stores, potentially favoring ones that don't compete directly with the Play Store.

Google's app store commission fee reduction from 30% to 15% significantly benefits developers earning up to $1 million annually. Beyond that, the standard 30% rate applies, making the reduction less impactful for high-earning apps. Estimated data.

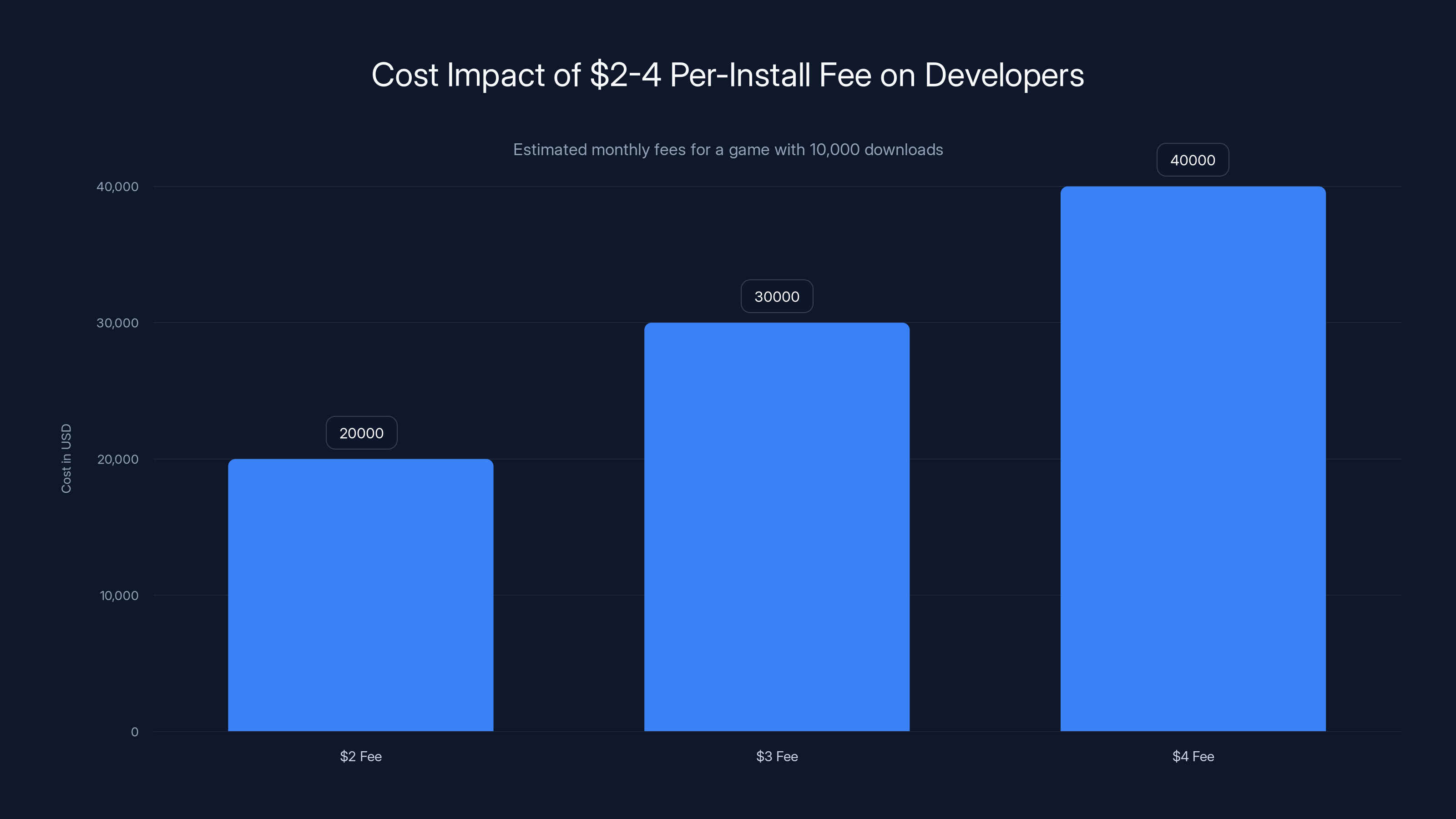

The Nuclear Option: The $2-4 Per-Install Fee

Here's where Epic and Google's settlement shows its teeth. If Judge Donato rejects the deal and forces Google to implement the original court-ordered remedies, Epic and Google have a backup plan that's... let's call it draconian.

Developers who want to avoid Google's payment systems entirely—who want to use their own payment processors without paying the 30% commission—would have to pay Google a different way:

Let's think through what this means in practice. A moderately popular game gets 10,000 downloads in a month. That's

This is the settlement's implicit threat. Accept our deal with the reduced commission and Registered App Stores, or we'll make the alternative so expensive that nobody uses it.

Some have argued this is actually genius contract design: it makes the settlement look good by comparison, while the alternative looks punitive. Others argue it proves that Google still doesn't understand they lost this case. A jury said they acted illegally. You don't get to propose a remedy that's more punitive than the original judgment while claiming it's a mutual settlement.

Judge Donato clearly wasn't impressed by this logic. During the hearing, his skepticism was visible. This was basically Google saying, "Let us write the rules, or we'll make the default option terrible."

Why Judge Donato Was Skeptical

The judge's reaction wasn't random skepticism. He had specific concerns about what Epic and Google were actually trying to accomplish with this settlement.

First, there was the optics problem. Epic and Google showed up to court suddenly claiming to be partners after years of hostile litigation. They brought Fortnite back to the Play Store right before announcing the settlement—a move that looked less like reconciliation and more like a coordinated PR campaign.

Second, Judge Donato had read the expert testimony. Stanford economist Doug Bernheim had testified about how markets work. The judge had heard evidence about how app store dominance works in practice. He understood that simply reducing fees or creating theoretical alternatives doesn't automatically fix a monopoly. The monopoly itself—the control over distribution—was the problem.

Third, the settlement was silent on key remedies. The original judgment required Google to unbundle Google Play Services. That's a massive technical change that would give third-party apps a fair chance against Google's own apps (Google Maps, Gmail, Chrome, etc.). But the settlement barely mentions this. It doesn't mandate the unbundling. It's vague about how Google's pre-installed dominance would be addressed.

Fourth, the deal lacked teeth for enforcement. How would someone prove Google was unfairly prioritizing its own payment system over alternatives? What happens if a Registered App Store complains that Google is discriminating against them? The settlement didn't include clear enforcement mechanisms or penalties for violations.

Fifth, and maybe most damning, the settlement only applies to "the United States," while also claiming it would improve the situation "globally." This contradiction matters. Google's monopoly is truly global. App developers worldwide face the same 30% commission. If the settlement only binds Google in the US, they can easily maintain their current practices everywhere else, rendering the deal pointless for anyone outside America.

Donato essentially asked: How is this actually a remedy, versus just a fee reduction with some marketing language around "choice"?

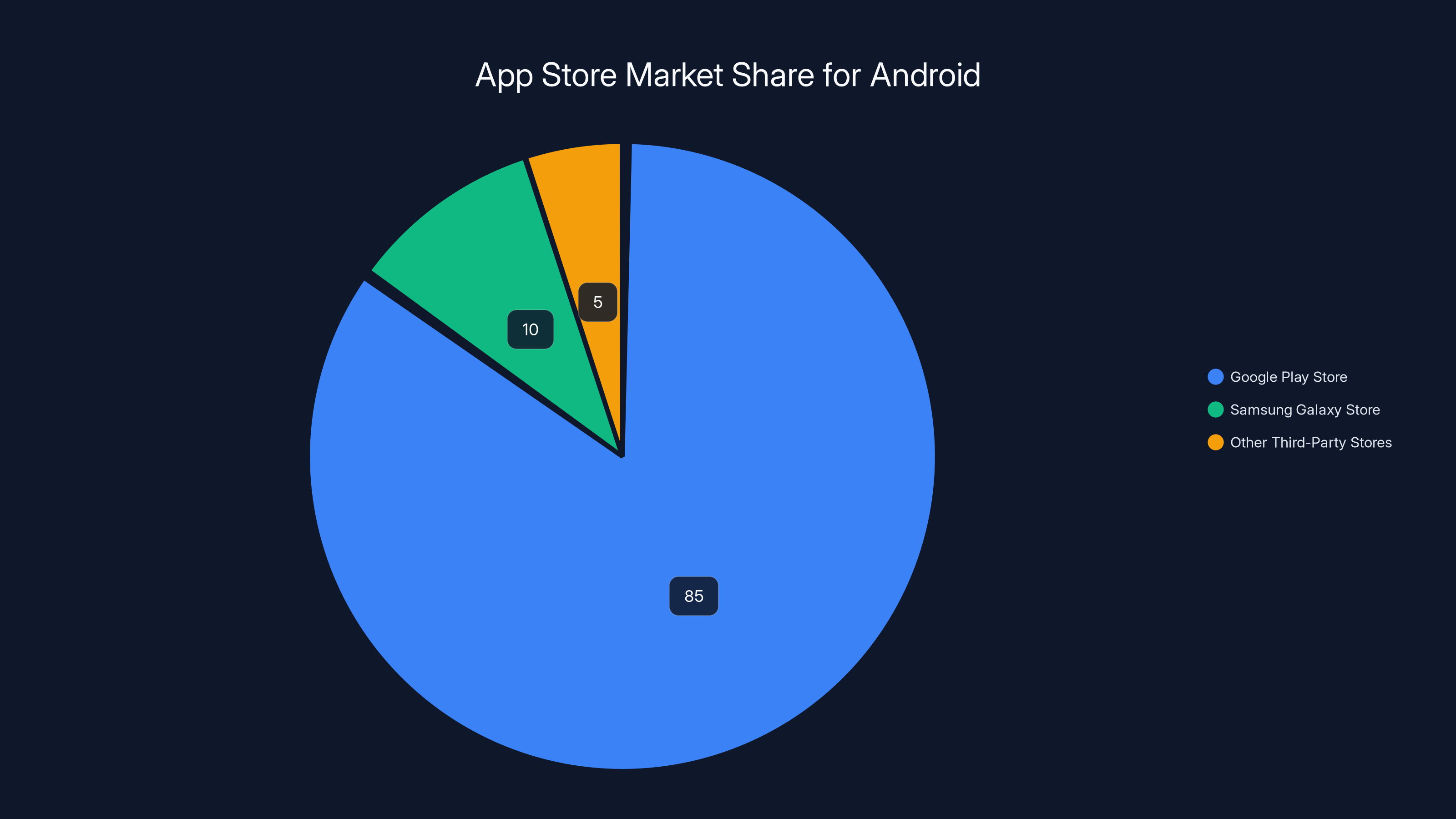

Google Play Store dominates the Android app market with an estimated 85% share, leaving Samsung Galaxy Store and other third-party stores with significantly smaller portions. (Estimated data)

The Global Impact Question

One of the most overlooked aspects of this settlement is the geographic scope problem.

Epic sued Google in US court under US antitrust law. Judge Donato has authority to enforce remedies in US markets. But Android's monopoly is a global phenomenon. Developers in India, Brazil, South Korea, and Europe all face the same 30% fee structure. They all lack real distribution alternatives.

The settlement promises global fee reductions and global Registered App Stores. But how can a US court enforce remedies in countries with their own antitrust laws and regulators?

Here's what actually happens: In parallel to the Epic case, the EU is investigating Google's app store practices under its Digital Markets Act. South Korea has imposed its own restrictions on Google's commission rates. Japan has called out Google's practices. Multiple countries are moving independently toward the same conclusion: Google's Android app store needs regulation.

Google's smart move is to get ahead of all these jurisdictions by offering a settlement in the US case that's roughly comparable to what regulators elsewhere are demanding. That way, Google can claim they're being reasonable and proactive, while also not being forced to do much more than they already would have anyway under pressure from multiple governments.

Epic gets to claim victory. Google gets to reduce fees slightly and claim they fixed the problem. Developers in developed countries get modest relief. Regulators get to point to the settlement as progress.

The only people who don't win? Developers in countries without antitrust enforcement. They're still locked into the same system with no real alternatives.

What Developers Actually Care About

Take a step back and think about this from the perspective of an actual app developer who's built something people want to use.

You have two immediate concerns: Can you reach customers, and how much money do you keep from each transaction?

Under the settlement, the answer to both questions is still "complicated."

For reaching customers, the Registered App Stores program is theoretically helpful. But in reality, most Android users will still go to the Google Play Store because it's pre-installed and familiar. Samsung's Galaxy Store exists, but it has a fraction of the users and discovery mechanisms of Play Store. Other third-party stores have even smaller audiences. You'd need to be huge to prioritize distribution outside Google's system.

For keeping money, the 15% rate on the first

The bigger issue is that fees aren't the only problem. Google also controls search rankings within its store. They prioritize certain categories over others. They can recommend their own apps instead of yours. They can change the algorithm at any time. They can bundle features into Google apps that would be better as separate services. Having your app distributed through their store means competing against their rules, their priorities, and their own competing products—all without real recourse.

What developers wanted was actual structural change: unbundled Google Play Services, truly independent alternative app stores, clear rules about fair treatment, and enforcement mechanisms with real penalties.

What they're getting is a fee reduction and theoretical alternatives that Google still controls.

Estimated data suggests that while the commission rate drops in alternative scenarios, the potential revenue could increase due to lower fees and fairer treatment. Estimated data.

The Supreme Court Possibility

Here's something most coverage missed: this settlement could end up at the Supreme Court anyway.

If Judge Donato approves the settlement, Epic could appeal. They could argue the deal doesn't adequately remedy the illegal conduct. Google could appeal. They could argue the remedies are too restrictive. Either party could argue the judge exceeded his authority or misinterpreted antitrust law.

Given that the Supreme Court hasn't touched antitrust law in meaningful ways in decades, and given that the highest court has been skeptical of aggressive antitrust enforcement in recent years, there's a real possibility that whatever Donato decides gets reviewed at the Supreme Court level.

This is actually what might be happening strategically. Maybe Epic and Google would both benefit from Supreme Court involvement. Epic could push for stronger remedies. Google could push for a more permissive interpretation of their practices. Either way, the highest court would be forced to clarify what antitrust law means in the context of platform monopolies.

The downside: that process takes years. Developers are still stuck in the current system while everything gets litigated and appealed.

How This Compares to Apple's Situation

Apple faces similar antitrust scrutiny. Epic sued Apple too. But Apple's case is different in crucial ways.

Apple controls i OS, which is their own operating system on their own hardware. Google controls Android, which is technically open-source—manufacturers can modify it, users can theoretically use different versions. That distinction matters in antitrust law. It's harder to argue that Apple has an illegal monopoly when they're exercising control over their own property.

Google's situation is trickier because they distribute Android for free to manufacturers. Samsung, One Plus, Motorola—they all use Android. Google doesn't own these devices. So when Google imposes their app store requirements as a condition of using Android, it's arguably more anti-competitive because it affects devices they don't own.

The irony is that Apple's control is actually tighter than Google's. Apple won't let you sideload apps at all (until very recently in the EU). They control the entire ecosystem. But because they control their own hardware, regulators are more hesitant to break up Apple than they are to regulate Google.

Google's position is: "We give away Android for free. We provide Play Services. We maintain the ecosystem. Developers benefit. How is that monopolistic?" Apple's position is: "We control our entire system end-to-end. We maintain consistency and security." The first is more sympathetic until you realize that giving away Android for free doesn't cost Google much when they make billions from data and advertising that Android generates.

The Epic vs Google case spanned over three years, culminating in a December 2023 verdict against Google for antitrust violations. Estimated data based on key events.

What Regulators Worldwide Are Saying

One reason the settlement exists is that Google knew it couldn't win everywhere. While this US case played out, regulators globally were moving independently toward the same conclusion.

In Europe, the Digital Markets Act explicitly requires alternative app stores and restricts how platform owners can favor their own services. South Korea's Telecommunications Business Act mandates that Google must allow alternative payment systems. Japan's Fair Trade Commission has issued recommendations. India has opened investigations.

Google's strategy became: negotiate a US settlement that's roughly aligned with where global regulators are heading anyway. That way, they can present it as a coherent global policy rather than being forced into piecemeal compliance with different regulators.

It's the difference between writing your own story versus being forced to read from someone else's script. Google prefers the former.

This is why the settlement claims global impact even though the court order is technically US-only. Google is essentially saying, "We're implementing this globally because it's the right thing to do," while actually they're implementing it because they'll be forced to by other regulators otherwise.

The Timeline and What Comes Next

Judge Donato needs to make a decision relatively soon. The original remedies were supposed to take effect before the end of 2024. We're now well into 2025, and the case is still unresolved.

If the judge approves the settlement: Implementation begins on Google's timeline. The fee reductions rollout. The Registered App Store program launches. Enforcement happens through the settlement agreement itself, with Epic maintaining the ability to monitor compliance and return to court if Google violates the terms.

If the judge rejects the settlement: Google must immediately begin implementing the original court-ordered remedies. This means unbundling Google Play Services, opening up Android to true sideloading, creating clear rules for how alternative app stores operate, and restructuring their entire business model within a specific timeframe. This path is painful for Google but creates stronger structural change.

If the judge approves the settlement but with modifications: This is probably the most likely scenario. Donato might say, "I'll approve the fee reduction and Registered App Stores program, but you're also implementing the Google Play Services unbundling, and here's how enforcement works." That would be the compromise position.

Then, appeals happen. The case likely goes to a higher court. We could be litigating the details of this for another 2-3 years.

Meanwhile, developers are working in the current system. They're launching apps on the Play Store because that's where the users are. They're paying the 30% commission because that's the rule. They're hoping that whatever gets decided will actually improve their situation.

What This Means for Consumers

You might be wondering: as someone who uses Android, does any of this affect me?

Yes, but indirectly. Lower app store fees could theoretically lead to lower app prices. More app stores could lead to more choice and less arbitrary app removals. More payment options could mean safer transactions.

But here's the reality: most consumers don't care about app store fees. They don't know that developers pay 30% commissions. They just want apps to exist, be affordable, and work well. From that perspective, whether apps are distributed through Google's store, Samsung's store, or a third-party store doesn't matter as long as they can find what they want.

Where this matters more is for app quality and privacy. When app stores have real competition, stores compete on curation quality, security standards, and privacy protections. If Google's store is just one of many options, they have incentive to maintain high standards or lose developers and users to competitors. If Google's store is effectively the only option (because it has 90%+ of users), they can be lazy about curation and security.

The settlement's biggest consumer impact might be more subtle: it signals that antitrust regulators take platform monopolies seriously. That has downstream effects on how companies design platforms, what rules they enforce, and how much developers can be exploited. Those effects eventually reach consumers as more competitive services.

The Bigger Picture: What This Case Means

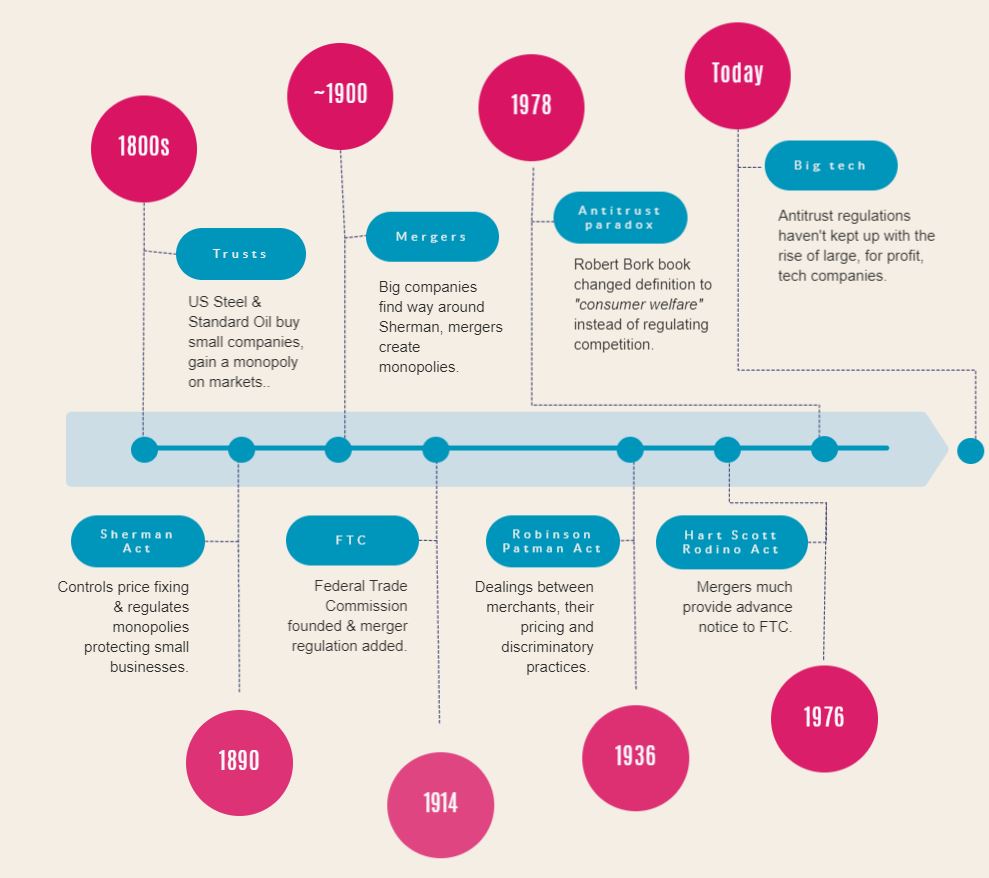

Epic vs Google is part of a larger reckoning with tech monopolies that started in the late 2010s.

Break it down: Amazon was investigated for using seller data to compete with merchants on its platform. Google was sued over search and ad tech. Facebook faced antitrust challenges. Apple faced pressure over app store policies. Microsoft faced investigation into bundling IE with Windows (a historical precedent).

Each case is different, but they all ask the same core question: When a company controls the infrastructure everyone else depends on, at what point does controlling that infrastructure become illegal?

For app stores, the answer is becoming clear: if you control how apps reach consumers, and you also compete in the app market (Google Maps, Gmail, You Tube), you have an unfair advantage. You can't be both the game and the referee.

Epic vs Google established that principle in US law. The settlement may weaken the enforcement of that principle. But the principle itself is now established. Future antitrust cases will build on this precedent.

That's why the settlement matters beyond just the 30% fee. It's about whether antitrust law can actually reach into how companies design their platforms, or whether platforms are untouchable as long as they claim to provide a "service" to the ecosystem.

Key Takeaways for App Developers

If you're developing apps right now, here's what you need to know:

Today's reality: The Play Store is still your only viable distribution channel for reaching mainstream Android users. The 30% commission still applies to in-app purchases and paid apps. Your revenue depends on Google's algorithms and rules.

Settlement scenario: Fees drop to 15% on the first $1M revenue. Alternative app stores become available but with limited user bases. You now have to evaluate whether the effort of distributing elsewhere is worth the reduced commission.

Rejected settlement scenario: Unbundling happens. Your app gets fair treatment alongside Google's apps. Alternative distribution becomes more viable. But implementation is messy and takes years.

Takeaway: Diversify your business model now. Don't rely on a single payment system. Don't count on Play Store featuring to drive growth. Build your own audience directly. That way, whatever ruling comes, you're not entirely dependent on Google's decisions.

Questions Remaining Unanswered

Even if Judge Donato approves the settlement, massive questions linger.

How does Google define what counts as a "Registered App Store"? Could they exclude stores that directly compete with them? Could they approve stores that pay a kickback? Without clear rules, this becomes another way for Google to control which alternatives exist.

What happens to data sharing? Google knows everything about what apps people download and use. Competitors don't have that data. Does the settlement address this asymmetry? Not clearly.

What about pre-installation advantages? Android devices come with Google apps pre-installed. Users have to actively choose alternatives. The settlement doesn't mandate removing pre-installation advantages. It's a massive structural advantage that persists.

How is enforcement handled? If a developer claims Google violated the settlement terms, what court handles it? What's the process? What penalties exist? The settlement is vague on all of this.

What about international markets where Google's dominance is even stronger than the US? The settlement claims global applicability but doesn't explain how that works jurisdictionally.

These unanswered questions are why Judge Donato was skeptical. A good settlement answers the hard questions clearly. This settlement leaves room for interpretation, which favors the more powerful party—Google.

FAQ

What is the Epic vs Google antitrust case about?

The case centers on whether Google illegally maintains a monopoly over Android app distribution and charging practices. Epic Games sued Google for removing Fortnite from the Play Store after Epic bypassed Google's 30% payment commission, arguing that Google's app store practices violated antitrust law by preventing fair competition and harming both developers and consumers.

How did the jury rule in the Epic vs Google case?

In December 2023, the jury unanimously found that Google illegally maintained its monopoly over Android app distribution and that Google's practices unreasonably restricted competitors' ability to distribute apps. The appeals court upheld this verdict, confirming Google's conduct was illegal and establishing the foundation for court-ordered remedies.

What remedies did Judge Donato originally order?

The judge ordered Google to allow rival app stores on Android, stop discriminating against competitors in search results, unbundle Google Play Services to prevent Google apps from having unfair advantages, allow sideloading, and prevent retaliation against developers or competing app stores. These structural remedies were designed to fundamentally alter how Android operates rather than just impose financial penalties.

What are the main terms of the settlement agreement?

The settlement reduces Google's app store commission from 30% to 15% on the first $1 million in annual revenue per app globally, creates a "Registered App Stores" program allowing other companies to distribute apps on Android, and includes various transparency and non-retaliation commitments. However, it leaves many original remedies unaddressed, particularly the unbundling of Google Play Services.

Why is Judge Donato skeptical of the settlement?

The judge expressed concerns that the settlement doesn't address core structural issues like Google's control over app discovery and prioritization, the bundling of Google Play Services giving Google apps unfair advantages, and the lack of clear enforcement mechanisms. He also questioned whether Registered App Stores would have genuine independence or remain under Google's control, and whether the deal was more of a marketing exercise than meaningful reform.

What happens if the judge rejects the settlement?

If rejected, Google must immediately implement the original court-ordered remedies, including unbundling Google Play Services, enabling true sideloading, and establishing clear rules for alternative app store operation. This path involves more disruptive change to Google's business model but creates stronger structural protections for developers and competitors.

How does the $2-4 per-install alternative fee work?

If developers want to avoid using Google's payment system (and thus avoid the commission), the settlement threatens an alternative: developers would pay Google

What is a Registered App Store, and how would it work?

A Registered App Store is an app distribution service other than the Google Play Store (like Samsung's Galaxy Store) that would be officially recognized on Android. Developers could potentially distribute through these stores as alternatives to Play Store, though Google still controls approval criteria, security standards, and potentially fees these stores must pay.

Does the settlement apply globally or only in the US?

The court order technically applies to the United States, but the settlement claims global applicability. However, enforcement outside the US is unclear since a US court has limited authority over international markets. Other regulators (EU, South Korea, Japan) are pursuing parallel investigations that may result in different requirements.

What would this settlement mean for app developers and consumers?

For developers, the 15% reduced commission on initial revenue is meaningful but limited in scope. For consumers, lower fees might eventually translate to cheaper apps, and more app store options could improve choice and security. However, the settlement leaves Google's core monopoly control intact, so structural competition improvements are modest without additional regulation or court-ordered changes.

What Happens Now

We're at a pivot point. Judge Donato will make a decision that reverberates across the entire app ecosystem. Will he approve a settlement that achieves incremental change, or reject it and force structural transformation?

Whichever path he chooses, this case has already changed the game. It established that platform monopolies can be held legally accountable. It showed that antitrust law can reach into how companies design their core services. It proved that even the biggest tech companies can lose in court.

For developers, the lesson is clear: don't count on any single platform to remain unchanged. Build your business to be resilient regardless of which way this case resolves. For regulators, this case is a blueprint for how to challenge platform monopolies effectively. For Google, it's a reminder that dominance, once challenged successfully, is hard to defend.

The settlement might get approved. Fees might drop slightly. Alternative app stores might become technically available. Life might go on largely as before.

Or the original remedies might stand. Android might actually change fundamentally. Google might be forced to unbundle its apps and services, creating real competitive parity. The app ecosystem might actually become more open.

Judge Donato will decide. But one thing is certain: the days of absolute platform control without accountability are over. What happens next is the details of how that accountability actually works in practice.

Related Articles

- UK VPN Ban Explained: Government's Online Safety Plan [2025]

- FTC Meta Monopoly Appeal: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- X's Algorithm Open Source Move: What Really Changed [2025]

- UK Social Media Ban for Under-16s: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Meta's Illegal Gambling Ad Problem: What the UK Watchdog Found [2025]

- Setapp Mobile iOS Store Shutdown: What It Means for App Distribution [2026]

![Epic vs Google Settlement: What Android's Future Holds [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/epic-vs-google-settlement-what-android-s-future-holds-2025/image-1-1769109258352.jpg)